- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Strategies to Find Sources

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Strategies to Find Sources

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- How to Pick a Topic

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

The Research Process

![local literature in research brainly Interative Litearture Review Research Process image (Planning, Searching, Organizing, Analyzing and Writing [repeat at necessary]](https://libapps.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/64450/images/ResearchProcess.jpg)

Planning : Before searching for articles or books, brainstorm to develop keywords that better describe your research question.

Searching : While searching, take note of what other keywords are used to describe your topic, and use them to conduct additional searches

♠ Most articles include a keyword section

♠ Key concepts may change names throughout time so make sure to check for variations

Organizing : Start organizing your results by categories/key concepts or any organizing principle that make sense for you . This will help you later when you are ready to analyze your findings

Analyzing : While reading, start making notes of key concepts and commonalities and disagreement among the research articles you find.

♠ Create a spreadsheet to record what articles you are finding useful and why.

♠ Create fields to write summaries of articles or quotes for future citing and paraphrasing .

Writing : Synthesize your findings. Use your own voice to explain to your readers what you learned about the literature on your topic. What are its weaknesses and strengths? What is missing or ignored?

Repeat : At any given time of the process, you can go back to a previous step as necessary.

Advanced Searching

All databases have Help pages that explain the best way to search their product. When doing literature reviews, you will want to take advantage of these features since they can facilitate not only finding the articles that you really need but also controlling the number of results and how relevant they are for your search. The most common features available in the advanced search option of databases and library online catalogs are:

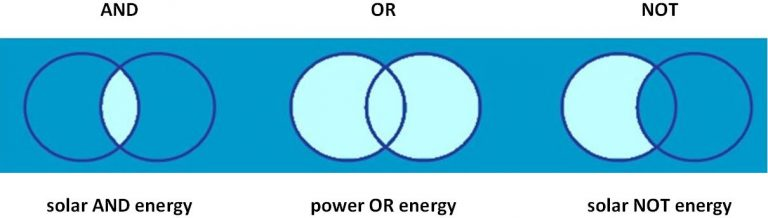

- Boolean Searching (AND, OR, NOT): Allows you to connect search terms in a way that can either limit or expand your search results

- Proximity Searching (N/# or W/#): Allows you to search for two or more words that occur within a specified number of words (or fewer) of each other in the database

- Limiters/Filters : These are options that let you control what type of document you want to search: article type, date, language, publication, etc.

- Question mark (?) or a pound sign (#) for wildcard: Used for retrieving alternate spellings of a word: colo?r will retrieve both the American spelling "color" as well as the British spelling "colour."

- Asterisk (*) for truncation: Used for retrieving multiple forms of a word: comput* retrieves computer, computers, computing, etc.

Want to keep track of updates to your searches? Create an account in the database to receive an alert when a new article is published that meets your search parameters!

- EBSCOhost Advanced Search Tutorial Tips for searching a platform that hosts many library databases

- Library's General Search Tips Check the Search tips to better used our library catalog and articles search system

- ProQuest Database Search Tips Tips for searching another platform that hosts library databases

There is no magic number regarding how many sources you are going to need for your literature review; it all depends on the topic and what type of the literature review you are doing:

► Are you working on an emerging topic? You are not likely to find many sources, which is good because you are trying to prove that this is a topic that needs more research. But, it is not enough to say that you found few or no articles on your topic in your field. You need to look broadly to other disciplines (also known as triangulation ) to see if your research topic has been studied from other perspectives as a way to validate the uniqueness of your research question.

► Are you working on something that has been studied extensively? Then you are going to find many sources and you will want to limit how far back you want to look. Use limiters to eliminate research that may be dated and opt to search for resources published within the last 5-10 years.

- << Previous: How to Pick a Topic

- Next: Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Module 5: Writing About Literature

Finding and evaluating research sources, introduction.

In order to create rhetorically effective and engaging pieces, research writers must be able to find appropriate and diverse sources and to evaluate those sources for usefulness and credibility. This chapter discusses how to locate such sources and how to evaluate them. On the one hand, this is a chapter about the nuts and bolts of research. If you have written research papers before, searching for sources and citing them in your paper may, at times, have appeared to you as purely mechanical processes, chores necessary to produce a paper. On the other hand, when writers work with research sources, first finding and then evaluating them, they do rhetorical work. Finding good sources and using them effectively helps you to create a message and a persona that your readers are more likely to accept, believe, and be interested in than if unsuitable and unreliable sources are used. This chapter covers the various kinds of research sources available to writers. It discusses how to find, evaluate, and use primary and secondary sources, printed and online ones.

Types of Research Sources

It is a well-known cliché: we live in an information age. Information has become a tangible commodity capable of creating and destroying wealth, influencing public opinion and government policies, and effecting social change. As writers and citizens, we have unprecedented access to different kinds of information from different sources. Writers who hope to influence their audiences need to know what research sources are available, where to find them, and how to use them.

Primary and Secondary Sources

Definition of primary sources.

Let us begin with the definition of primary and secondary sources. A primary research sources is one that allows you to learn about your subject “firsthand.” Primary sources provide direct evidence about the topic under investigation. They offer us “direct access” to the events or phenomena we are studying. For example, if you are researching the history of World War II and decide to study soldiers’ letters home or maps of battlefields, you are working with primary sources. Similarly, if you are studying the history of your hometown in a local archive that contains documents pertaining to that history, you are engaging in primary research. Among other primary sources and methods are interviews, surveys, polls, observations, and other similar “firsthand” investigative techniques. The fact that primary sources allow us “direct access” to the topic does not mean that they offer an objective and unbiased view of it. It is therefore important to consider primary sources critically and, if possible, gather multiple perspectives on the same event, time period, or questions from multiple primary sources.

Definition of Secondary Sources

Secondary sources describe, discuss, and analyze research obtained from primary sources or from other secondary sources. Using the previous example about World War II, if you read other historians’ accounts of it, government documents, maps, and other written documents, you are engaging in secondary research. Some types of secondary sources with which you are likely to work include books, academic journals, popular magazines and newspapers, websites, and other electronic sources. The same source can be both primary and secondary, depending on the nature and purpose of the project. For example, if you study a culture or group of people by examining texts they produce, you are engaging in primary research. On the other hand, if that same group published a text analyzing some external event, person, or issue and if your focus is not on the text’s authors but on their analysis, you would be doing secondary research. Secondary sources often contain descriptions and analyses of primary sources. Therefore, accounts, descriptions, and interpretations of research subjects found in secondary sources are at least one step further removed from what can be found in primary sources about the same subject. And while primary sources do not give us a completely objective view of reality, secondary sources inevitably add an extra layer of opinion and interpretation to the views and ideas found in primary sources. All texts are rhetorical creations, and writers make choices about what to include and what to omit. As researchers, we need to understand that and not rely on either primary or secondary sources blindly.

Writing Activity: Examining the Same Topic through Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary and secondary sources can offer writers different views of the same topic. This activity invites you to explore the different perspectives that you may get after investigating the same subject through primary and secondary sources. It should help us see how our views of different topics depend on the kinds of sources we use. Find several primary sources on a topic that interests you. Include archival documents, first- hand accounts, lab experiment results, interviews, surveys, and so on. Depending on how much time you have for this project, you may or may not be able to consult all of the above source types. In either case, try to consult sources of three or four different kinds. Next, write a summary of what you learned about your subject as a result of your primary-source investigation. Mention facts, dates, important people, opinions, theories, and anything that seems important or interesting. Now, conduct a brief secondary-source search on the same subject. Use books, journals, popular magazines and newspapers, Internet sites, and so on. Write a summary of your findings. Finally, compare the two summaries. What differences do you see? What new ideas, perspectives, ideas, or opinions did your secondary-source search yield? As a result of these two searches, have you obtained different accounts of the same research subject? Pay special attention to the differences in descriptions, accounts, or interpretations of the same subject. Notice what secondary sources add to the treatment of the subject and what they take away, compared to the primary sources.

Print and Electronic Sources

Researcher have at their disposal both printed and electronic sources. Before the advent of the Internet, most research papers were written with the use of printed sources only. Until fairly recently, one of the main stated goals of research writing instruction was to give students practice in the use of the library. Libraries are venerable institutions, and therefore printed sources have traditionally been seen (with good reason, usually,) as more solid and reliable than those found on the Internet. With the growing popularity of the Internet and other computerized means of storing and communicating information, traditional libraries faced serious competition for clients. It has become impractical if not impossible for researchers to ignore the massive amount of information available to them on the Internet or from other online sources. As a result, it is not uncommon for many writers beginning a research project to begin searching online rather than at a library or a local archive. For example, several times in the process of writing this essay, when I found myself in need of information fast, I opened my Web browser and researched online. With the popularity of the Internet ever increasing, it has become common practice for many student writers to limit themselves to online research and to ignore the library. While there are some cases when a modified version of such an approach to searching may be justifiable (more about that later), it is clear that by using only online research sources, a writer severely limits his or her options. This section covers three areas. First, we will discuss the various types of printed and online sources as well the main similarities and differences between them. Next, I’d like to offer some suggestions on using your library effectively and creatively. Finally, we will examine the topic of conducting online searches, including methods of evaluating information found on the Internet.

Know Your Library

It is likely that your college or university library consists of two parts. One is the brick and mortar building, often at a central location on campus, where you can go to look for books, magazines, newspapers, and other publications. The other part is online. Most good libraries keep a collection of online research databases that are supported, at least in part, by your tuition and fees, and to which only people who are affiliated with the college or the university that subscribes to these databases have access. Let us begin with the brick and mortar library. If you have not yet been to your campus library, visit it soon. Larger colleges and universities usually have several libraries that may specialize in different academic disciplines. As you enter the library, you are likely to find a circulation desk (place where you can check out materials) and a reference desk. Behind the reference desk you will find reference librarians. Instead of wandering around the library alone, hoping to hit the research sources that you need for your project, it is a good idea to talk to a reference librarian at the beginning of every research project, especially if you are at a loss for a topic or research materials. Your brick and mortar campus library is likely to house the following types of materials:

- Books (these include encyclopedias, dictionaries, indexes, and so on)

- Academic Journals

- Popular magazines

- Government documents

- A music and film collection (on CDs, VHS tapes, and DVDs)

- A CD-Rom collection

- A microfilm and microfiche collection

- Special collections, such as ancient manuscripts or documents related to local history and culture.

According to librarian Linda M. Miller, researchers need to “gather relevant information about a topic or research question thoroughly and efficiently. To be thorough, it helps to be familiar with the kinds of resources that the library holds, and the services it provides to enable access to the holdings of other libraries” (2001, 61). Miller’s idea is a simple one, yet it is amazing how many inexperienced writers prefer to use the first book or journal they come across in the library as the basis for their writing and do not take the time to learn what the library has to offer. Here are some practical steps that will help you learn about your library:

Take a tour of the library with your class or other groups if such tours are available. While such group tours are generally less effective than conducting your own searches of a topic that interests you, they will give you a good introduction to the library and, perhaps, give you a chance to talk to a librarian.

Check your library’s website to see if online “virtual” tours are available. At James Madison University where I work, the librarians have developed a series of interactive online activities and quizzes which anyone wishing to learn about the JMU libraries can take in their spare time.

Talk to reference librarians! They are truly your best source of information. They will not get mad at you if you ask them too many questions. Not only are they paid to answer your questions, but most librarians love what they do and are eager to share their expertise with others.

Go from floor to floor and browse the shelves. Learn where different kinds of materials are located and what they look like.

Pay attention to the particulars of your campus library’s architecture. I am an experienced library user, but it look me some time, after I arrived at my university for the first time, to figure out that our library building has an annex that can only be accessed by taking a different elevator from the one leading to the main floors.

Use the library not only as a source of knowledge but as a source of entertainment and diversion. I like going to the library to browse through new fiction acquisitions. Many campus libraries also have excellent film and music collections.

The items on the list above will help you to acquire a general understanding of your campus library. However, the only way to gain an in-depth and meaningful knowledge of your library is to use it for specific research and writing projects. No matter how attentive you are during a library tour or while going from floor to floor and learning about all the different resources your library has to offer, it is during searchers that you conduct for your research projects that you will become most interested and involved in what you are doing. Here, therefore, is an activity that combines the immediate goal of finding research sources for a research project with the more long-term goal of knowing what your campus library has to offer.

Activity: Conducting a Library Search for a Writing Project

If you have a research and writing topic in mind for your next project, head for your brick-and-mortar campus library. As soon as you enter the building, go straight to the reference desk and talk to a reference librarian. Be aware that some of the people behind the reference desk may be student assistants working there. As a former librarian assistant myself and as a current library user, I know that most student assistants know their job rather well, but sometimes they need help from the professionals. So, don’t be surprised if the first person you approach refers you to someone else. Describe your research interests to the librarian. Be proactive. The worst disservice you can do yourself at this point is to look, sound, and act disinterested. Remember that the librarian can be most helpful if you are passionate about the subject of your research and if—this is very important—the paper you are writing is not due the next day. So, before you go to the library, try to narrow your topic or formulate some specific research questions. For example, instead of saying that you are interested in dolphins, you might explain that you are looking for information about people who train dolphins to be rescue animals. If the librarian senses that you have a rather vague idea about what to research and write about, he or she may point you to general reference sources such as indexes, encyclopedias, and research guides. While those may prove to be excellent thought-triggering publications, use them judiciously and don’t choose the first research topic you find just because your library has a lot of resources on it. After all, your research and writing will be successful only when you are deeply interested in and committed to your investigation. If you have a more definite idea about what you would like to research and write about, the reference librarian will likely point you to the library’s online catalog. I have often seen librarians working alongside students to help them identify or refine a writing topic. Find several different types of materials pertaining to your topic. Include books and academic articles. Don’t forget popular magazines and newspapers—the popular press covers just about any subject, event, or phenomena, and such articles may bring a unique perspective not found in academic sources. Also, don’t neglect to look in the government documents section to see if there has been any legislation or government regulation relevant to your research subject. Remember that at this stage your goal is to learn as much as you can about your topic by casting your research net as far and wide as you can. So, do not limit yourself to the first few sources you will find. Keep looking, and remember that your goal is to find the best information available. You will probably have to look in a variety of sources. If you are pressed for time you may not be able to study the books dedicated to your topic in detail. In this case, you may decide to focus your research entirely on shorter texts, such as journal and magazine articles, websites, government documents, and so on. However it is always a good idea to at least browse through the books on your topic to see whether they contain any information or leads worth investigating further.

Cyber Library

Besides the brick and mortar buildings, nearly all college and university libraries have a Web space that is a gateway to more documents, resources, and information than any library building can house. From your library’s website, you can not only search the library’s holdings but also access millions of articles, electronic books, and other resources available on the Internet. It is a good idea to conduct a search from your campus library page rather than from your favorite search engine. There are three reasons for that. First, most of the materials you will find through your library site are accessible to paying subscribers only and cannot be found via any search engine. Second, online library searches return organized and categorized results, complete with the date of publication and source—something that cannot be said about popular search engines. Finally, by searching online library databases you can be reasonably sure that the information you retrieve is reliable.

So, what might you expect to find on your library’s website? The site of the library at James Madison University where I work offers several links. In addition to the link to the library catalog, there is a Quick Reference link, a link called Research Databases, a Periodical Locator, Research Guides, and Internet Search. There are also links to special collections and to the featured or new electronic databases to which the library has recently subscribed. While your school library may use other names for these links, the kinds of resources they offer will be similar to what JMU’s library has to offer. Most of these links are self-explanatory. Obviously, the link to the library catalog allows you to search your brick and mortar library’s collection. A periodical locator search will tell you what academic journals, popular magazines, and newspapers are available at your library. The Internet search option will allow you to search the World Wide Web, except that your library’s Internet searching function will probably allow you to conduct meta-searches—i.e., searches using many search engines simultaneously. Where a link like Research Databases or Research Guides will take you is a little less obvious. Therefore I will cover these two types of library resources in some detail. Let us start with the research databases. An average-size college or university subscribes to hundreds, if not thousands, of online databases on just about every subject. These databases contain, at a minimum, information about titles, authors, and sources of relevant newspaper and journal articles, government documents, online archive materials, and other research sources. Most databases provide readers with abstracts (short summaries) of those materials, and a growing number of online databases offer full texts of articles. From the research-database home page, it is possible to search for a specific database or by subject. Research-guide websites are similar to the database home pages, except that, in addition to database links, they often offer direct connections to academic journals and other relevant online resources on the research subject. Searching online is a skill that can only be learned through frequent practice and critical reflection. Therefore, in order to become a proficient user of your library’s electronic resources, you will need to visit the library’s website often and conduct many searches. Although most library websites are organized according to similar principles and offer similar types of resources, it will be up to you as a researcher and learner to find out what your school library has to offer and to learn to use those resources. I hope that the following activities will help you in that process.

Activity: Exploring your Cyber Library

Go to your school library’s website and explore the kinds of resources it has to offer.

Conduct searches on a subject you are currently investigating or interested in investigating in the future, using the a periodical locator resource (if your library has one). Then, conduct similar searches of electronic databases and research guides.

Summarize, whether in an oral presentation or in writing, your search process and the kinds of sources you have found. Pay attention to particular successes and failures that occurred as you searched.

Print Sources or Electronic?

In the early years of the Internet, there was widespread mistrust of the World Wide Web and the information it had to offer. While some of this mistrust is still present (and justifiable), the undeniable fact is that the authority of the Internet as a legitimate and reliable source of information has increased considerably in recent years. For example, academic journals in almost every discipline complement their printed volumes with Web versions, and some are now only available online. These online journals employ the same rigorous submission review processes as their printed counterparts. Complete texts of academic and other books are sometimes available on the Internet. Respected specialized databases and government document collections are published entirely and exclusively online. Print and electronic sources are not created equal, and although online and other electronic texts are gaining ground as legitimate research resources, there is still a widespread and often justified opinion among academics and other writers that printed materials make better research sources. Some materials available in some libraries simply cannot be found online and vice versa. For example, if you are a Shakespeare scholar wishing to examine manuscripts from the Elizabethan times, you will not find them online. To get to them, you will have to visit the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, or a similar repository of Elizabethan manuscripts. On the other hand, if you are researching the Creative Commons movement, which is a community dedicated to reforming copyright laws in this country, then your best bet is to begin your search on the Internet at http://www.creativecommons.org/. Surely, after reading the website, you will need to augment your research by reading other related materials, both online and in print, but in this case, starting online rather than in the library is a reasonable idea. As a researching writer, you should realize that printed and electronic sources are not inherently bad or good. Either type can be reliable or unreliable; either can be appropriate or inappropriate for a specific research project. It is up to researchers and writers to learn how to select both print and electronic sources judiciously and how to evaluate them for their reliability and appropriateness for particular purposes.

Determining the Suitability and Reliability of Research Sources

Much of the discussion about the relative value of printed and electronic—especially Internet—sources revolves around the issue of reliability. When it comes to libraries, the issue is more or less clear. Libraries keep books, journals, ands other publications that usually undergo a rigorous pre- and post-publication review process. It is reasonable to assume that your campus library contains very few or no materials that are blatantly unreliable or false, unless those materials are kept there precisely to demonstrate their unreliability and falsehood. As a faculty member, I am sometimes asked by my university librarians to recommend titles in my academic field that our university library should own. Of course my opinion (or that of another faculty member) does not completely safeguard against the library acquiring materials that contain errors and or misleading information; we use our experience and knowledge in the field to recommend certain titles and omit certain others. Faculty recommendations are the last stage of long process before a publication gets to a campus library. Before that, every book, journal article, or other material undergoes a stringent review from the publisher’s editors and other readers. And while researchers still need to use sound judgment in deciding which library sources to use in their project, the issue is usually one of relevance and suitability for a specific research project and specific research questions rather than one of whether the information presented in the source is truthful or not. The same is true of some electronic sources. Databases and other research sources published on CD-ROMs, as well as various online research websites that accompany many contemporary writing textbooks, for example, are subject to the same strict review process as their printed counterparts. Information contained in specialized academic and professional databases is also screened for reliability and accuracy. If, as we have established, most of the materials you are likely to encounter in your campus library are generally trustworthy, then your task as a researcher is to determine the relevance of the information contained in books, journals, and other materials for your particular research project. It is a simple question, really: will my research sources help me answer the research questions that I am posing in my project? Will they help me learn as much as I can about my topic and create a rhetorically effective and interesting text for my readers? Consider the following example. Recently, the topic of the connection between certain antidepressant drugs and suicidal tendencies among teenagers who take those drugs has received a lot of media coverage. Suppose you are interested in researching this topic further. Suppose, too, that you want not only to give statistical information about the problem in your paper but also to study firsthand accounts of the people who have been negatively affected by the antidepressants. When you come to your campus library, you have no trouble locating the latest reports and studies that give you a general overview of your topic, including rates of suicidal behavior in teenagers who took the drugs, tabulated data on the exact relationships between the dosage of the drugs and the changes in the patients’ moods, and so on. All this may be useful information, and there is a good chance that, as a writer, you will still find a way to use it in your paper. You could, for example, provide the summary of the statistics in order to introduce the topic to your readers. However, this information does not fulfill your research purpose completely. You want to understand what it is like to be a teenager whose body and mind have been affected by the antidepressants, yet the printed materials you have found so far offer no such insight. They fulfill your goal only partially. To find such firsthand accounts, then, you will either have to keep looking in the library or conduct interviews with people who have been affected by these drugs.

Suitability of Sources

Determine how suitable a particular source is for your current research project. To do this, consider the following factors:

- Scope: What topics and subtopics does the source cover? Is it a general overview of your subject or it is a specialized resource?

- Audience: Who is the intended audience for the text? If the text itself is too basic or too specialized, it may not match the expectations and needs of your own target audience.

- Timeliness: When was the source published? Does it represent the latest information, theories, and views? Bear in mind, though, that if you are conducting a historical investigation, you will probably need to consult older materials, too.

What are credentials of the author(s)? This may be particularly important when you use Internet sources, since there are so few barriers to publishing online. One needn’t have an academic degree or credentials to make one’s writing publicly available. As part of your evaluation of the source’s authority, you should also pay attention to the kinds of external sources that were used during its creation. Look through the bibliography or list of works cited attached to the text. Not only will it help you determine how reliable and suitable the source is, but it may also provide you with further leads for your own research. Try asking the above questions of any source you are using for a research project you are currently conducting.

Reliability of Internet Sources

Charles Lowe, the author of the essay “The Internet Can Be a Wonderful Place, but . . .” offers the following opinion of the importance of the Internet as a research source for contemporary researchers:

To a generation raised in the electronic media culture, the Internet is an environment where you feel more comfortable, more at home than the antiquated libraries and research arenas of the pre-electronic, print culture. To you, instructors just don’t get it when they advise against using the Internet for research or require the bulk of the sources for a research paper to come from the library (129-130).

Indeed, the Internet has become the main source of information not only for college students, but also for many people outside academia. And while I do not advise you to stay away from the Internet when researching and I generally do not require my own students to use only printed sources, I do know that working with Internet sources places additional demands on the researcher and the writer. Because much of the Internet is a democratic, open space, and because anyone with a computer can post materials online, evaluating online sources is not always easy. A surprisingly large number of people believe much of the information on the Internet, even if this information is blatantly misleading or its authors have a self-serving agenda. I think many students uncritically accept information they find on the Internet because some of the sites on which this information appears look and sound very authoritative. Used to believing the published word, inexperienced writers often fall for such information as legitimate research data. So, what are some of strategies you can use to determine that reliability? The key to successful evaluation of Internet research sources, as any other research sources, is application of your critical reading and thinking skills. In order to determine the reliability of any source, including online sources, it is advisable to conduct a basic rhetorical analysis of that source. When deciding whether to use a particular website as a research source, every writer should ask and answer the following questions:

- Who is the author (or, authors) of the website and the materials presented on it? What is known about the site’s author(s) and its publishers and their agendas and goals?

- What is the purpose of the website?

- Who is the target audience of the website

- How do the writing style and the design of the website contribute to (or detract from) its meaning?

Website Authors and Publishers

As with a printed source, first we need to consider the author and the publisher of a website. Lowe suggests that we start by looking at the tag in the website’s URL. Whether it is a “.com,” an “.org,” a “.net, “or an “.edu” site can offer useful clues about the types and credibility of materials located on the site. In addition to the three most common URL tags listed above, websites of military organizations use the extension “.mil” while websites hosted in other countries have other tags that are usually abbreviations of those countries’ names. Sites of government agencies end in “.gov.” For example, most sites hosted in Great Britain have the tag “.uk,” which stands for “United Kingdom.” Websites based in Italy usually have the tag “.it,” and so on. Typically, a “.com” site is set up to sell or promote a product or service. Therefore, if you are researching Nike shoes, you will probably not want to rely on http://www.nike.com/ if you want to get a more objective review of the product. While Nike’s website may provide some useful information about the products it sells, the site’s main purpose is to sell Nike’s goods, playing up the advantages of their products. Keep in mind that not all “.com” websites try to sell something. Sometimes academics and other professionals obtain “.com” addresses because they are easy to obtain. For example, the professional website of Charles Lowe (cited above) is located at http://www.cyberdash.com/ . Political candidates running for office often also choose “.com” addresses for their campaign websites. In every case, you need to apply your critical reading skills and your judgment when evaluating a website. The “.org” sites usually belong to organizations, including political groups. These sites can present some specific challenges to researchers trying to evaluate their credibility and usefulness. To understand these challenges, let us consider the “.org” sites of two political research organizations, also known as “think tanks.” One is the conservative Heritage Foundation (http://www.heritage.org), and the other is the traditionally liberal Center for National Policy (http://www.cnponline.org). Both sites have “About” pages intended to explain to their readers the goals and purposes of the organizations they represent. The Heritage Foundation’s site contains the following information:

. . . The Heritage Foundation is a research and educational institute—a think tank—whose mission is to formulate and promote conservative public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong national defense. (http://www.heritage.org/about)

This statement can tell a researcher a lot about the research articles and other materials contained in the site. It tells us that the authors of the site are not neutral, nor do they pretend to be. Instead, they are advancing a particular political agenda, so, when used as research sources, the writings on the site should not be seen as unbiased “truths” but as arguments. The same is true of the Center for National Policy’s website, although its authors use a different rhetorical strategy to explain their political commitments. They write:

The Center for National Policy (CNP) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy organization located in Washington, DC. Founded in 1981, the center’s mission is to engage national leaders with new policy options and innovative programs designed to advance progressive ideas in the interest of all Americans (http://www.cnponline.org/people_and_programs.html)

It takes further study of the center’s website, as well as sure knowledge of the American political scene, to realize that the organization leans toward the left of the political spectrum. The websites of both organizations contain an impressive amount of research, commentary, and other materials designed to advance the groups’ causes. When evaluating “.org” sites, it is important to realize that they belong to organizations, and each organization has a purpose or a cause. Therefore, each organizational website will try to advance that cause and fulfill that purpose by publishing appropriate materials. Even if the research and arguments presented on those sites are solid (and they often are), there is no such thing as an unbiased and disinterested source. This is especially true of political and social organizations whose sole purpose is to promote agendas. The Internet addresses ending in “.edu” are rather self-evident—they belong to universities and other educational institutions. On these sites we can expect academic articles and other writings, as well as papers and other works created by students. These websites are also useful resources if you are looking for information on a specific college or university. Be aware, though, that typically any college faculty member or student can obtain Web space from their institution and publish materials of their own choosing there. Thus some of the texts that appear on “.edu” sites may be personal rather than academic. In recent years, some political research organizations have begun to use Web addresses with the “.edu” tag. One of these organizations is The Brookings Institution, whose address is http://www.brookings.edu. Government websites that end in “.gov” can be useful sources of information on the latest legislation and other regulatory documents. The website with a “.net” extension can belong to commercial organizations or online forums.

Website Content

Now that we have established principles for evaluating the authors and publishers of Web materials, let us look at the content of the writing. As I have stated above, like all writing, Web writing is argumentative; therefore it is important to recognize that authors of Web texts work to promote their agendas or highlight the events, organizations, and opinions that they consider right, important, and worthy of public attention. Different writers work from different assumptions and try to reach different audiences. Websites of political organizations are prime examples of that.

Activity: Evaluating Website Content

Go to one of the following websites: The Heritage Foundation (http://www.heritage.org), The Center for National Policy (http://www.cnponline.org), The Brookings Institution (http://www.brookings.edu), or The American Enterprise Institute (http://www.aei.org). Or choose another website suggested by your instructor. Browse through the site’s content and consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the site?

- What is its intended audience? How do we know?

- What are the main subjects discussed on the sites?

- What assumptions and biases do the authors of the publications on the site seem to have? How do we know?

- What research methods and sources do the authors of these materials use? How does research help the writers of the site state their case?

Apply the same analysis to any online sources you are using for one of your research projects.

Website Design and Style

The style and layout of any text is a part of that text’s message, and online research sources are no exception. Well-designed and written websites add to the ethos (credibility) of their authors while badly designed and poorly written ones detract from it. Sometimes, however, a website with a good-looking design can turn out to be an unreliable or unsuitable research source.

In Place of a Conclusion: Do Not Accept A Source Just Because It Sounds or Looks Authoritative

Good writers try to create authoritative texts. Having authority in their writing helps them advance their arguments and influence their audiences. To establish such authority, writers use a variety of methods. As has been discussed throughout this essay, it is important for any researcher to recognize authoritative and credible research sources. On the other hand, it is also important not to accept authoritative sources without questioning them. After all, the purpose of every researched piece of writing is to create new views and new theories on the subject, not to repeat the old ones, however good and well presented those old theories may be. Therefore, when working with reliable and suitable research sources, consider them solid foundations that will help you to achieve a new understanding of your subject, which will be your own. Applying the critical source-evaluation techniques discussed in this essay will help you to accomplish this goal.

- Finding and Evaluating Research Sources. Authored by : Pavel Zemliansky. Located at : http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/ENGL002-Chapter-4-Research-Writing.pdf . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Subject guides

- Researching for your literature review

- Literature sources

Researching for your literature review: Literature sources

- Literature reviews

- Before you start

- Develop a search strategy

- Keyword search activity

- Subject search activity

- Combined keyword and subject searching

- Online tutorials

- Apply search limits

- Run a search in different databases

- Supplementary searching

- Save your searches

- Manage results

Scholarly databases

It's important to make a considered decision as to where to search for your review of the literature. It's uncommon for a disciplinary area to be covered by a single publisher, so searching a single publisher platform or database is unlikely to give you sufficient coverage of studies for a review. A good quality literature review involves searching a number of databases individually.

The most common method is to search a combination of large inter-disciplinary databases such as Scopus & Web of Science Core Collection, and some subject-specific databases (such as PsycInfo or EconLit etc.). The Library databases are an excellent place to start for sources of peer-reviewed journal articles.

Depending on disciplinary expectations, or the topic of our review, you may also need to consider sources or search methods other than database searching. There is general information below on searching grey literature. However, due to the wide varieties of grey literature available, you may need to spend some time investigating sources relevant for your specific need.

Grey literature

Grey literature is information which has been published informally or non-commercially (where the main purpose of the producing body is not commercial publishing) or remains unpublished. One example may be Government publications.

Grey literature may be included in a literature review to minimise publication bias . The quality of grey literature can vary greatly - some may be peer reviewed whereas some may not have been through a traditional editorial process.

See the Grey Literature guide for further information on finding and evaluating grey sources.

See the Moodle book MNHS: Systematically searching the grey literature for a comprehensive module on grey literature for systematic reviews.

In certain disciplines (such as physics) there can be a culture of preprints being made available prior to submissions to journals. There has also been a noticeable rise in preprints in medical and health areas in the wake of Covid-19.

If preprints are relevant for you, you can search preprint servers directly. A workaround might be to utilise a search engine such as Google Scholar to search specifically for preprints, as Google Scholar has timely coverage of most preprint servers including ArXiv, RePec, SSRN, BioRxiv, and MedRxiv.

Articles in Press are not preprints, but are accepted manuscripts that are not yet formally published. Articles in Press have been made available as an early access online version of a paper that may not yet have received its final formatting or an allocation of a volume/issue number. As well as being available on a journal's website, Articles in Press are available in databases such as Scopus and Web of Science, and so (unlike preprints) don't necessarily require a separate search.

Conference papers

Conference papers are typically published in conference proceedings (the collection of papers presented at a conference), and may be found on an organisation or Society's website, as a journal, or as a special issue of journal.

In certain disciplines (such as computer science), conference papers may be highly regarded as a form of scholarly communication; the conferences are highly selective, the papers are generally peer reviewed, and papers are published in proceedings affiliated with high-quality publishing houses.

Conference papers may be indexed in a range of scholarly databases. If you only want to see conference papers, database limits can be used to filter results, or try a specific index such as the examples below:

- Conference proceedings citation index. Social science & humanities (CPCI-SSH)

- Conference proceedings citation index. Science (CPCI-S)

- ASME digital library conference proceedings

Honours students and postgraduates may request conference papers through Interlibrary Loans . However, conference paper requests may take longer than traditional article requests as they can be difficult to locate; they may have been only supplied to attendees or not formally published. Sometimes only the abstract is available.

If you are specifically looking for statistical data, try searching for the keyword statistics in a Google Advanced Search and limiting by a relevant site or domain. Below are some examples of sites, or you can try a domain such as .gov for government websites.

Statistical data can be found in the following selected sources:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics

- World Health Organization: Health Data and statistics

- Higher Education Statistics

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics

- Tourism Australia Statistics

For a list of databases that include statistics see: Databases by Subject: Statistics .

If you are specifically looking for information found in newspapers, the library has a large collection of Australian and overseas newspapers, both current and historical.

To search the full-text of newspapers in electronic format use a database such as Newsbank.

Alternatively, see the Newspapers subject guide for comprehensive information on newspaper sources available via Monash University library and open source databases, as well as searching tips, online videos and more.

Dissertations and theses

The Monash University Library Theses subject guide provides resources and guidelines for locating and accessing theses (dissertations) produced by Monash University as well as other universities in Australia and internationally.

International theses:

There are a number of theses databases and repositories.

A popular source is:

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global which predominantly, covers North American masters and doctoral theses. Full text is available for theses added since 1997.

Australia and New Zealand theses:

Theses that are available in the library can be found using the Search catalogue.

These include:

- Monash doctoral, masters and a small number of honours theses

- other Australian and overseas theses that have been purchased for the collection.

Formats include print (not available for loan), microfiche and online (some may have access restrictions).

Trove includes doctoral, masters and some honours theses from all Australian and New Zealand universities, as well as theses awarded elsewhere but held by Australian institutions.

Tips:

- Type in the title, author surname and/or keywords. Then on the results page refine your search to 'thesis'.

- Alternatively, use the Advanced search and include 'thesis' as a keyword or limi t your result to format = thesis

- << Previous: Literature reviews

- Next: Before you start >>

Your browser does not support javascript. Some site functionality may not work as expected.

- Literary Events & Conferences

- Literary Venues

- Local Authors

- Anthologies & Journals

- Local Publishers

- Local Services

- Associations & Organizations

- Academics & Research

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- Community (Local) Literature

Community (Local) Literature: Local Authors

A sampling of local author websites & blogs.

- Kelli Russell Agodon

- Peter Bagge

- Matt Briggs

- Karen Fisher

- Jeannine Hall Gailey

- Jeanne Heuving

- Ursula K. LeGuin

- Neil Low A UW Bothell alum!

- Maureen McQuerry

- Richelle Mead

- Paul Nelson

- Jennie Shortridge

- Garth Stein

Directories & Lists

- Directory of American Poets & Writers

- PoetsWest Member Directory

- << Previous: Literary Venues

- Next: Anthologies & Journals >>

- Last Updated: Sep 19, 2023 10:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/bothell/community_literature

Quick Links:

- Licensing Information

- Contributing Authors

- 1. Let's Get Writing

- 1.1. The 5 C Guidelines

- 1.2. How to Write Articles Quickly and Expertly

- 2. Critical Thinking

- 2.1. Critical Thinking in the Classroom

- 2.2. Necessary and Sufficient Conditions

- 2.3. Good Logic

- 3. APA for Novices

- 3.1. Hoops and Barriers

- 3.2. Crafts and Puzzles

- 3.3. The Papers Trail

- 3.4. The Fine Art of Sentencing

- 3.5. Hurdles

- 3.6. Small Stressors

- 4. Literature Reviews

- 4.1. Introduction to Literature Reviews

- 4.2. What is a Literature Review?

- 4.3. How to Get Started

- 4.4. Where to Find the Literature

- 4.5. Evaluating Sources

- 4.6. Documenting Sources

- 4.7. Synthesizing Sources

- 4.8. Writing the Literature Review

- 4.9. Concluding Thoughts on Literature Reviews

- Technical Tutorials

- Constructing an Annotated Bibliography with Zotero

- Extracting Resource Metadata from a Citation List with AnyStyle.io

- Exporting Zotero to a Spreadsheet

- APA 7 Job Aid

- Index of Topics

- Translations

Where to Find the Literature

Choose a sign-in option.

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Search a library catalog to locate electronic and print books.

- Search databases to find scholarly articles, dissertations, and conference proceedings.

- Retrieve a copy or the full text of information sources

- Identify and locate core resources in your discipline or topic area

Overview of discovery

Discovery, or background research, is something that happens at the beginning of the research process when you are just learning about a topic. It is a search for general information to get the big picture of a topic for exploration, ideas about subtopics and context for the actual focused research you will do later. It is also a time to build a list of distinctive, broad, narrow, and related search terms.

Discovery happens again when you are ready to focus in on your research question and begin your own literature review. There are two crucial elements to discovering the literature for your review with the least amount of stress as possible: the places you look and the words you use in your search .

The places you look depend on:

- The stage you are in your research

- The disciplines represented in your research question

- The importance of currency in your research topic

Review the information and publication cycles discussed in Chapter 2 to put those sources of this information in context.

The words you use will help you locate existing literature on your topic, as well as topics that may be closely related to yours. There are two categories for these words:

- Keywords – the natural language terms we think of when we discuss and read about a topic

- Subject terms – the assigned vocabulary for a catalog or database

The words you use during both the initial and next stage of discovery should be recorded in some way throughout the literature search process. Additional terms will come to light as you read and as your question becomes more specific. You will want to keep track of those words and terms, as they will be useful in repeating your searches in additional databases, catalogs, and other repositories. Later in this chapter, we will discuss how putting the two elements (the places we look and the words we use) together can be enhanced by the use of Boolean operators and discipline-specific thesauri.

Discovery is an iterative process. There is not a straight, bright line from beginning to end. You will go back into the literature throughout the writing of your literature review as you uncover gaps in the evidence and as additional questions arise.

Finding sources: Places to look

Let’s take some time to look at where the information sources you need for your literature review are located, indexed, and stored. At this stage, you have a general idea of your research area and have done some background searching to learn the scope and the context of your topic. You have begun collecting keywords to use in your later searching. Now, as you focus in on your literature review topic, you will take your searches to the databases and other repositories to see what the other researchers and scholars are saying about the topic.

The following resources are ordered from the more general and established information to the more recent and specific. Although it is possible to find some of these resources by searching the open web, using a search engine like Google or Google Scholar, this is not the most efficient or effective way to search for and discover research material. As a result, most of the resources described in this section are found from within academic library catalogs and databases, rather than internet search engines.

Finding books and ebooks

Look to books for broad and general information that is useful for background research. Books are “essential guides to understanding theory and for helping you to validate the need for your study, confirm your choice of literature, and certify (or contradict) its findings.” ( Fink, 4th ed., 2014, p. 77 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] ). In this section, we will consider print and electronic books as well as print and electronic encyclopedias.

Most academic libraries use the Library of Congress classification system to organize their books and other resources. The Library of Congress classification system divides a library’s collection into 21 classes or categories. A specific letter of the alphabet is assigned to each class. More detailed divisions are accomplished with two and three letter combinations. Book shelves in most academic libraries are marked with a Library of Congress letter-number combination to correspond to the Library of Congress letter-number combination on the spines of library materials. This is often referred to as a call number and it is noted in the catalog record of every physical item on the library shelves. ( Bennard et al, 2014a [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] )

The Library of Congress (LC) classification for Education (General) is L7-991, with LA, LB, LC, LD, LE, LG, LH, LJ, and LT subclasses. For example,

LB3012.2.L36 1995 Beyond the Schoolhouse Gate: Free Speech and the Inculcation of Values

In Nursing, the LC subject range is RT1-120. A book with this LC call number might look like: R121.S8 1990 Stedman’s Medical Dictionary . Areas related to nursing that are outside that range include:

R121 Medical dictionaries

R726.8 Hospice care

R858-859.7 Medical informatics

RB37 Diagnostic and laboratory tests

RB115 Nomenclature (procedural coding – CPT, ICD9)

RC69-71 Diagnosis

RC86.7 Emergency medicine

RC266 Oncology nursing

RC952-954.6 Geriatrics

RD93-98 Wound care

RD753 Orthopedic nursing

RG951 Maternal child nursing / Obstetrical nursing

RJ245 Pediatric nursing

RM216 Nutrition and diet therapy

RM301.12 Drug guides

In most libraries, there is a collection of reference material kept in a specific section. These books, consisting of encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauri, handbooks, atlases, and other material contain useful background or overview information about topics. Ask the librarian for help in finding an appropriate reference book. Although reference material can only be used in the library, other print books will likely be in what’s called the “circulating collection,” meaning they are available to check out.

The library also provides access to electronic reference material. Some are subject specific and others are general reference sources. Although each resource will have a different “look” just as different print encyclopedias and dictionaries look different, each should have a search box. Most will have a table of contents for navigation within the work. Content includes pages of text in books and encyclopedias and occasionally, videos. In all cases you will be able to collect background information and search terms to use later.

North American academic libraries buy or subscribe to individual ebook titles as well as collections of ebooks. Ebooks appear on various publisher and platforms, such as Springer, Cambridge, ebrary (ProQuest), EBSCO, and Safari to name a few. Although access to these ebooks varies by platform, you can find the ebook titles your library has access to through the library catalog. You can generally read the entire book online, and you can often download single chapters or a limited number of pages. You may be able to download an entire ebook without restrictions, or you may have to ‘check it out’ for a limited period of time. Some downloads will be in PDF format, others use another type of free ebook viewing software, like ePUB. Unlike public library ebook collections, most academic library ebooks are not be downloadable to ereader devices, such as Amazon’s Kindle

The Library Catalog

In general, everything owned or licensed by a library is indexed in “the library catalog”. Although most library catalogs are now sophisticated electronic products called ‘integrated library systems’, they began as wooden card filing cabinets where researchers could look for books by author, title, or subject.

While the look and feel of current integrated library systems vary between libraries, they operate in similar ways. Most library catalogs are quickly found from a library’s home page or website. The library catalog is the quickest way to find books and ebooks on your topic.

Here are some general tips for locating books in a library catalog:

- Use the search box generally found on a library’s home page to start a search.

- Type a book title, author name, or subject keywords into the search box.

- You will be directed to a results page.

- If you click on a book title or see an option to see more details about the book, you can look at its full bibliographic record, which provides more information about the book, as well as where to find the book. Pay particular attention to subjects associated with the item, adding relevant and appropriate terms to your list of search terms for future use.

- Look for an “Advanced Search” option near the basic or single search box

- Publication Year

- Call number

- And more…

- There is generally a “Format” list on the advanced search page screen. This list will give you options for limiting format to Print Books or Ebooks.

- You can limit searches to a specific library or libraries to narrow by location or ‘search everything’ to broaden your search.

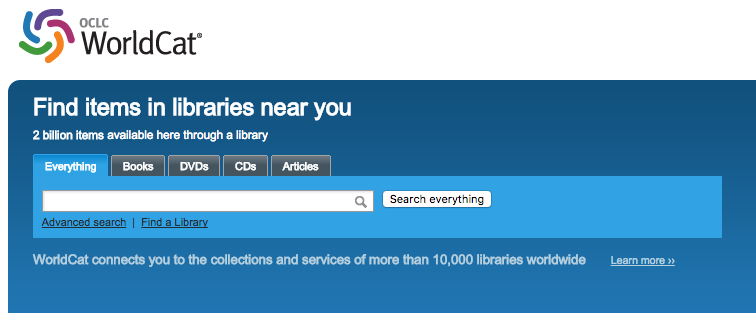

OCLC WorldCat ( https://www.worldcat.org/ ) is the world’s largest network of library content and it provides another way to search for books and ebooks. For students who do not have immediate access to an academic library catalog, WorldCat is a way to search many library catalogs at once for an item and then locate a library near you that may own or subscribe to it. Whether you will be able check the item out, request it, place an interlibrary loan request for it, or have it shipped will depend on local library policy. Note that like your own library catalog, WorldCat has a single search box, an Advanced search feature, and a way to limit by format and location.

Finding scholarly articles

While books and ebooks provide good background information on your topic, the main body of the literature in your research area will be found in academic journals. Scholarly journals are the main forum for research publication. Unlike books and professional magazines that may comment or summarize research findings, articles in scholarly journals are written by a researcher or research team. These authors will report in detail original study findings, and will include the data used. Articles in academic journals also go through a screening or peer-review process before publication,implying a higher level of quality and reliability. For the most current, authoritative information on a topic, scholars and researchers look to the published, scholarly literature. That said,

Journals, and the articles they contain, are often quite expensive. Libraries spend a large part of their collection budget subscribing to journals in both print and online formats. You may have noticed that a Google Scholar search will provide the citation to a journal article but will not link to the full text. This happens because Google does not subscribe to journals. It only searches and retrieves freely available web content. However, libraries do subscribe to journals and have entered into agreements to share their journal and book collections with other libraries. If you are affiliated with a library as a student, staff, or faculty member, you have access to many other libraries’ resources, through a service called interlibrary loan. Do not pay the large sums required to purchase access to articles unless you do not have another way to obtain the material, and you are unable to find a substitute resource that provides the information you need. ( Bennard et al, 2014 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] a)

A database is an electronic system for organizing information. Journal databases are where the scholarly articles are organized and indexed for searching. Anyone with an internet connection has free access to public databases such as PubMed and ERIC. Students can also search in library-subscribed general information databases (such as EBSCO’s Academic Search Premier) or a specialized or subject specific database (for example, a ProQuest version of CINAHL for Nursing or ERIC for Education).

Library databases store and display different types of information sets than a library catalog or Google Scholar. There are different types of databases that include:

- Indexes– with citations only

- Abstract databases – with citations and abstracts only

- Full text databases – with citations and the full text of articles, reports, and other materials

Library databases are often connected to each other by means of a “link resolver”, allowing different databases to “talk to each other.” For example, if you are searching an index database and discover an article you want to read in its entirety, you can click on a link resolver that takes you to another database where the full-text of the article is held. If the full-text is not available, an automated form to request the item from another library may be an option.

Why search a database instead of Google Scholar or your library catalog? Both can lead you to good articles BUT:

- The content is wide-ranging but not comprehensive or as current as a database that may be updated daily.

- Google Scholar doesn’t disclose its criteria for what makes the results “scholarly’ and search results often vary in quality and availability.

- Neither gives you as much control over your search as you get in a database.

Citation searches

Another way to find additional books and articles on your topic is to mine the reference lists of books and articles you already found. By tracing literature cited in published titles, you not only add to your understanding of the scholarly conversation about your research topic but also enrich your own literature search.

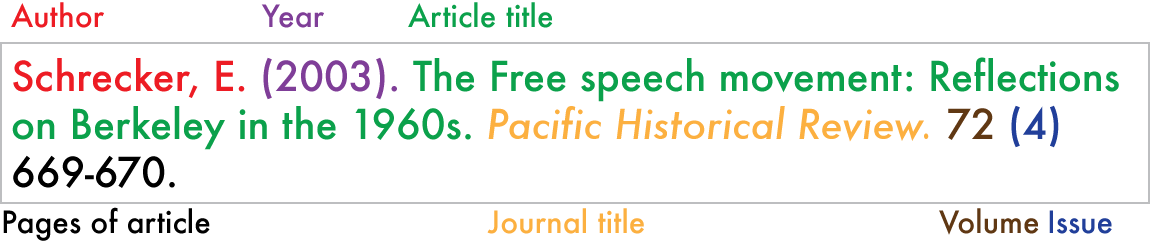

A citation is a reference to an item that gives enough information for you to identify it and find it again if necessary. You can use the citations in the material you found to lead you to other resources. Generally, citations include four elements:

For example,

For a good summary of how to read a citation for a book, book chapter, and journal article in both APA and MLA format, see this explanation at: https://edtechbooks.org/-jFG

Finding conference papers

Conference papers are often overlooked because they can be difficult to locate in full-text. Sometimes the papers from an annual proceeding are treated like an individual book, or a single special issue of a journal. Sometimes the papers from a conference are not published and must be requested from the original author. Despite publication inconsistency, conference papers may be the first place a scholar presents important findings and, as such, are relevant to your own research. Places to look for conference papers:

WorldCat [https://www.worldcat.org/]

- use keywords from the conference name (NOT the article title)

- it often helps to leave out terms like: conference, proceedings, transactions, congresses, symposia/symposium, exposition, workshop or meeting

- include the year of the conference

- include the city in which the conference took place

Google Scholar [https://scholar.google.com/]

- Search by keyword and add the word ‘conference’ and the year to your search, for example: ‘conference education 2008′

- For Education: ERIC, limit to ‘Collected Works–Proceedings’ or ‘Speeches/Meeting papers’

- For Nursing: CINAHL, limit to proceedings in the “Publication Type” box

- For Education: Education Full Text, limit to ‘proceeding’ in the “Document Type” box

- PsychInfo: limit to ‘Conference Proceedings’ in the “Record Type” Box

- Web of Science: limit to ‘conference’

Professional Societies & Other Sponsoring Organizations

Check the web sites of the organizations that sponsor conferences. Listings of conference proceedings are often under a “Publications” or “Meetings” tab/link. The National Library of Medicine maintains a conference proceedings subject guide [https://edtechbooks.org/-btz] for health-related national and international conferences. Though many papers/proceedings are not available for free, the organization web site will often contain citations of proceedings that you can request through interlibrary loan.

Finding dissertations

In addition to journal articles, original research is also published in books, reports, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations. Both theses and dissertations are very detailed and comprehensive accounts of research work. Dissertations and theses are a primary source of original research and include “referencing, both in text and in the reference list, so that, in principle, any reference to the literature may be easily traced and followed up.” ( Wallace & Wray, p. 187 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] ). Citation searching of the reference list or bibliography in a dissertation is another method for discovering the relevant literature for your own research area. Like conference papers, they are more difficult to locate and retrieve than books and articles. Some may be available electronically in full-text at no cost. Others may only be available to the affiliates of the university or college where a degree was granted. Others are behind paywalls and can only be accessed after purchasing. Both CINAHL and ERIC index dissertations. Individual universities and institutional repositories often list dissertations held locally. Other places to look for theses and dissertations include:

Dissertations Express [https://edtechbooks.org/-GkG] – search for dissertations from around the world. Search by subject or keyword, results include author, title, date, and where the degree was granted. Some are available in full-text at no cost, however most requirement payment.

EThOS [http://ethos.bl.uk/Home.do] – the national thesis service for the United Kingdom, managed by the British Library. It is a national aggregated record of all doctoral theses awarded by UK Higher Education institutions, providing free access to the full text of many theses for use by all researchers to further their own study.

Theses Canada [https://edtechbooks.org/-NRE] – a collaborative program between Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and nearly 70 accredited Canadian universities. The collection contains both microfiche and electronic theses and dissertations that are for personal or academic research purposes.

Advanced searching

Now that you have an idea of some of the places to look for information on your research topic and the form that information takes (books, ebooks, journals, conference papers, and dissertations), it’s time to consider not only how to use the specialized resources for your discipline but how to get the most out of those resources. To do a graduate-level literature review and find everything published on your topic, advanced search and retrieval skills are needed.

Search Operators

Literature review research often necessitates the use of Boolean operators to combine keywords. The operators – AND, OR, and NOT — are powerful tools for searching in a database or search engine. By using a combination of terms and one or more Boolean operator, you can focus your search and narrow your search results to a more specific area than a basic keyword search allows.

Boolean operators – allow you to combine your search terms using the keywords AND , OR and NOT . Look at the diagrams in Figure 4.6 to see how these terms will affect your results.

Truncation – If you use truncation (or wildcards), your search results will contain documents including variations of that term.

For example: light* will retrieve, of course, light , but also terms like: lighting , lightning , lighters and lights . Note that the truncation symbol varies depending on where you search. The most common truncation symbols are the asterisk (*) and question mark (?).

Phrase searching – Phrase searching is used to make sure your search retrieves a specific concept. For example “ durable wood products ” will retrieve more relevant documents than the same terms without quotation marks.

For a description of these more advanced search features, watch this short video tutorial [https://edtechbooks.org/-Rwb] on effective search strategies. ( Clark, 2016 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] ).

Finding sources in your discipline or topic area

It’s time to put these tips and your search skills to use. This is the point, if you have not done so already, to talk to a librarian. The librarian will direct you to the resources you need, including research databases to which the library subscribes, for your discipline or subject area. Literature reviews rely heavily on data from online databases, such as CINAHL for Nursing and ERIC for Education. Unfortunately, the costs to subscribe to vendor-provided products is high. Students affiliated with large university libraries that can afford to subscribe to these products will have access to many databases, while those who do not have fewer options.

Students who do not have access to subscription databases such as CINAHL or ERIC through Ebsco and ProQuest should use PubMed for Nursing at https://edtechbooks.org/-ws and the public version of ERIC at https://eric.ed.gov/ for literature review research.

Although a librarian is the best resource for learning how to use a specific tool, an online tutorial on how to search PubMed [https://edtechbooks.org/-kLR] may be useful and informative for those who do not have access to a librarian or a subscription database: Likewise, this document, titled “ How does the ERIC search work [https://eric.ed.gov/?advanced] ,” provided by the Institute of Education Sciences provides some helpful tips for searching the public version ERIC.

Specialized vocabulary

One major source of search terms in a database is a specialized dictionary, or thesaurus, used to index journal articles. Thesauri provide a consistent and standardized way to retrieve information, especially when different terms are used for the same concept. According to Fink ( 2014 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] ), “evidence exists that using thesaurus terms produces more of the available citations than does reliance on key words…Using the appropriate subject heading will enable the reviewer to find all citations regardless of how the author uses the term.” (p. 24).

In Education and Nursing, thesauri are available. In subscription databases, as well as in PubMed and the public version of ERIC, look for the thesaurus to guide you to appropriate and relevant subject terms.

Citation Searching

Citation searching works best when you already have a relevant work that is on topic. From the document you identified as useful for your own literature review, you can either search citations forward or backward to gather additional resources. Cited reference searching and reference or bibliography mining are advanced search techniques that may also help generate new ideas as well as additional keywords and subject areas.

For cited reference searching, use Google Scholar or library databases such as Web of Science or Scopus. These tools trace citations forward to link to newly published books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written after the document you found. Through cited reference searching, you may also locate works that have been cited numerous times, indicating what may be a seminal work in your field.

With citation mining, you will look at the references or works cited list in the resource you located to identify other relevant works. In this type of search, you will be tracing citations backward to find significant books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written before the document you found. For a brief discussion about citation searching [https://edtechbooks.org/-KT] , check out this article by Hammond & Brown ( 2008 [https://edtechbooks.org/-YiX] ).

The two most important finding tools you will use are a library catalog and databases. Looking for information in catalogs and databases takes practice.

Get started by setting aside some dedicated time to become familiar with the process:

- Practice by locating one reference book and one ebook in your library catalog or WorldCat