Table of Contents

Introduction, techniques and metalanguage, essay 1: how does persepolis: the story of a childhood explore what it means to live in fear and oppression.

- Essay 2:Marji’s grandmother says: “Always keep your dignity and be true to yourself.” To what extent does Marji follow her grandmother’s advice?

- Essay 3: Discuss how history is depicted in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood.

- Essay 4: “There were two kinds of women.” ‘Persepolis argues that were one of the primary targets of the fundamentalist regime.’ To what extent do you agree?

- Essay 5: How does Marjane Satrapi use her illustrations to effect in Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood?

- Essay 6: ’Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood shows us that in authoritarian regimes there is no hope of resistance.’ To what extent do you agree?

- Essay 7: What role do Marji’s parents play in her development as a person?

- Essay 8: Discuss the role of the minor characters in Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood

Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood is the first of Marjane Satrapi’s two-part graphic novel memoirs of her youth and young womanhood. It is set during and in the immediate aftermath of one of the 20 th Century’s most important incidents – the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The graphic novel explores this tumultuous period through the eyes of the young Marjane (frequently referred to as Marji), who must grapple with adolescence whilst also trying to make sense of the rapidly changing world around her.

Satrapi contextualises her story within the vast history of Iran, from the ancient cultures of Elam and Persia through to the modern day. The memoir takes its title from the Greek name of the ancient capital of Persia ( Perses = Persia, Polis = city). The young Marjane has a powerful pride of her country’s ancient past, and as a child she is inspired by ancient Zoroastrian festivals and the words of the ancient prophet of Zoroastrianism, Zarathustra. Zoroastrianism was replaced by Islam as the dominant religion of the region following the Arab conquests from the 7 th Century CE onwards, although there are still Kurdish minorities spread throughout Syria, Turkey and Iraq who follow a modern incarnation of the ancient faith. Satrapi repeatedly references the distant past in order to contextualise the events of the memoir and demonstrate that the version of Iran which emerged after the revolution did not reflect a return to a traditional or “pure” cultural tradition.

The background to the Iranian Revolution is complex and contested. Its immediate causes were probably economic, but there were further-reaching factors. The Shah who governed at the time relied on force and brutality to keep his subjects in line. Further, he pursued a secularist and pro-Western policy agenda which many felt was contrary to Iranian culture. The Shah owed his position to a coup d’état in 1953 orchestrated by Western powers who desired safe access to Iranian markets. This was a crucial reason for general anti-regime sentiment. The Shah pursued dramatic land reforms which may have helped create an industrial urban class, who could be swayed by socialist ideas, and an educated intelligentsia (such as the Satrapis) who also opposed his dictatorship. For many other Iranians, his (often extremely draconian) attempts to secularise the country were seen as an attack on their culture. Widespread discontent found a voice in the radical Ayatollah Khomeini (Ayatollah is a religious title) who returned from an exile imposed by the regime. Eventually, after widespread protests and street violence, the Shah fled the country. A popular vote installed the hard-core Shiite Islamist Ayatollah Khomeini into power, and he quickly began exterminating democratic or Marxist opposition groups, abolishing the rights gained by women under the Shah’s modernising reforms, and shutting down the free press.

In Persepolis , these events are experienced from the perspectives of the Satrapis, a progressive and secular family who believe in equality between the sexes and the classes. They are friendly with their Jewish neighbours, uncommon in a time of extremely hostile Jewish/Islamic relations, attempt (unsuccessfully) to teach their maid to read, drink alcohol on occasion, and are generally opposed to the new regime. They view the establishment of the Islamic Republic as a betrayal of the “leftist” ideals of the Revolution, in which they were active. The Satrapis, in common with many opposition groups and Western powers, drastically underestimate the competence and brutal efficiency of the Islamic regime, initially and repeatedly asserting that the fundamentalists are powerful but incapable of governing. They live in a fraught and complex ideological position. They are passionate defenders of Western notions of reason, freedom of the individual, freedom of religion or irreligion, democratic rule and equality between the sexes. However, they are under no illusions about the hypocritical foreign policy of countries such as America and Britain, and disdain “modern imperialism.”

For the young Marjane, this relationship finds its manifestation in Western popular culture. She listens to Iron Maiden, Michael Jackson and Kim Wilde. The memoir makes numerous references to the phenomenon of punk, a musical genre and lifestyle which erupted in the late 1970s in Britain (in bands such as the Sex Pistols, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Clash and the Slits), America (the Ramones, Black Flag, X) and Australia (the Saints, Radio Birdman, the Birthday Party, the Go-Betweens). Punk music is characterised by rebellious and ironic lyrics (see “Anarchy in the UK” by the Pistols) and extremely loud, aggressive, guitar-driven music. Ideologically it emphasised rebellion, anti-authoritarianism, equality and personal freedom. Naturally, therefore, it is especially attractive to a free-thinking young woman in a theocratic regime such as Marjane Satrapi. It is also especially reviled by members of the Guardians of the Revolution, the religious and moral police established under the Islamic Republic.

Persepolis explores the fractures and contradictions in Iranian society with nuance and compassion, and with a degree of innocence thanks to the youth of its protagonist. It was critically acclaimed upon release, with commentators pointing to the stylish illustrations as an especially effective way of communicating the story, and adapted by Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud into an award-winning film in 2007. In 2019 it was listed as one of the hundred best novels of the 21 st Century by the Guardian newspaper.

Persepolis is a graphic novel, and much of the meaning of the text is thus generated through images. Satrapi varies her panel angles from long, mid-range and short in order to convey dramatic or emotional meaning. On page 42, for example, Satrapi conveys the jubilation following the resignation of the Shah in a long crowd scene, stacking revellers vertically to create a sense of liveliness and crowdedness. By contrast, the very first panel is of Marjane alone, staring at the reader and occupying the majority of the panel. There are often close-ups of this sort when Marjane directly addresses the reader, perhaps relaying a dictate of the regime, or providing context.

Satrapi makes use of various sorts of transitions , of theme or setting or style, to create connections or highlight juxtapositions. For example, page 102 transitions from a scene of carnage and devastation, as Satrapi relates the fate of thousands of boys lured onto the battlefields, to an image of her at a party, dressed as a punk, and “looking sharp.” The contrast highlights the disparate worlds of Iran; the poor kids who die in droves in battle, and the rich kids, who dance and party. Connected to the process of transitioning is the use of borders . The borders of panels in a graphic novel define the scene. There are moments in the text where Satrapi eliminates the borders of her slides – such as on page 51, as Siamak recounts the tortures meted out against political prisoners. The graphic images of torture are borderless, suggesting the impact that these descriptions have on Marjane; they transcend their physical and temporal setting and become a part of her life.

The images of torture described above, along with much of the text, are in a fairly graphic and literal style. Many sections of the books are treated in a much more stylised manner. The depiction of the burning Rex Cinema, for example, reimagines the burning victims in a ghostly, spiritual form. Similarly, the full-page panel depicting the Satrapis’ holiday to Spain and Italy is a swirling mix of images of those countries, through which the Satrapis fly serenely on a magic carpet. The pictorial style thus reflects the imagination of Marjane as much as it does physical reality; her depiction of Anoosh with a halo is perhaps the clearest example, along with her imagined conversations with God. These more fanciful depictions often serve as metaphors. The death of Anoosh leaves Marjane feeling “lost” and with no “bearings.” Satrapi conveys the sense of loss by drawing herself floating through space. Another occasion in which the content of the memoir is so extreme that it cannot be done justice by literal depiction is the moment when Marjane spots the dismembered arm of her dead friend in the wreckage of her home. The panel is black, as Satrapi explains that no scream could do justice to what she felt – and neither, the image implies, could any depiction.

Time is not treated in a linear fashion in Persepolis . When Satrapi recalls an earlier event, she may draw a panel depicting that earlier event alongside the contemporary ones. She starts her story in 1980, but then leaps back to her early childhood. This helps place the veil as a central image of the text. It also acts to foreshadow the direction of the Revolution, creating the impression of a cyclical process – as befits the word “revolution,” which in its literal meaning implies a fully circular motion.

Finally, Satrapi blends a variety of styles in her work in order to reflect the variety of influences on Iranian culture, and its subsequent influence on her life. Depictions of the Shah often feature ancient Persian reliefs of kings and warriors, depicting his attempt to revive an ancient form of Iranian culture. At other points Satrapi employs stylised, ornamental swirls to suggest calligraphy. These stylistic variations help build a sense of history behind the text, placing Satrapi’s life in a rich and ancient context.

Repression and Rebellion

Persepolis charts a transition in Iranian society between two equally repressive regimes. The first is the Shah’s, who rose to power in a Western-backed coup decades earlier. The Shah’s regime relied on violent repression to maintain order. When the Revolution of 1979 erupted – unexpectedly – Iranians took to the streets and demanded change. At first the Shah attempts to contain these demands for democracy through violence. For example, he burns down the Rex Cinema (it has never been proven who exactly burnt the cinema down, but there is a reasonable chance that the attack occurred as depicted in Persepolis ), killing around 400 people. Violence only strengthens the resolve of his opposition, however; the night after the conflagration at the cinema Marjane’s parents agree that demonstrations must escalate: “We can’t let things like that happen.” The revolutionary fervour rubs off on young Marji, who attempts to join a demonstration with her maid, Mehri – to her parents’ outrage. They had joined the demonstration in secret, and accidently picked a day characterised by even more violent repression – “Black Friday.”

Characters express optimism about the Revolution as it unfolds. Ebi Satrapi excitedly pronounces that “After a long sleep of 2500 years, the Revolution has finally awakened the people.” The Shah eventually flees and Marjane describes scenes of jubilation as the country had the biggest celebration of its entire history” and her mother proclaims that “the Devil has left” the country. At first, their hope appears to be vindicated: 3000 political prisoners, including old friends and relatives of the Satrapis, are released. However, the reader is already aware that the Revolution will take a darker turn, because the memoir makes use of a non-linear timeline and opens in 1980, in a religious theocracy in which girls and women must wear the veil. One of the themes of repression which begins to emerge in Persepolis is the fundamental similarities between repressive regimes, even if they appear to be ideologically disparate. The chapter entitled ‘The Sheep’ marks the beginning of the Revolution’s transition from anti-authoritarian freedom fight to repressive Islamic theocracy. The liberal, educated observers like Anoosh and Ebi are taken by surprise; Ebi is alarmed at “how ignorant our people are” and Anoosh falls back on Marxist-Leninism to explain what he hopes is a temporary advantage to the religious right: “But the religious leaders don’t know how to govern […] That’s just what Lenin explained in ‘The State and the Revolution.’” Soon afterwards, Mohsen is found dead and Siamak flees with his surviving family (his sister is murdered by the regime) disguised as sheep. Satrapi hints that the real sheep of the chapter may in fact have been the educated and complacent intellectuals, who failed to grasp how successfully the theocrats could gain power.

From here on the book is largely an account of surviving under a new repressive regime. The transition between regimes is seamless. As Marjane recounts: “And that is how all the former revolutionaries became the sworn enemies of the Republic.” Anoosh is executed, universities are closed down, wearing the veil becomes mandatory, dissidence is met with violence and a fully-fledged cultural revolution is instigated. Violence becomes the regime’s deterrent of choice, and speaking out is made too dangerous to contemplate. Thus, it is through smaller, private gestures of rebellion that personal freedom and identity is expressed. Alcohol is outlawed, along with parties, but the Satrapis and their friends risk awful punishment. Celebrating with other people is innate to humanity, and without these opportunities to relax and express themselves, people argue that “we might as well just bury ourselves now.” The Satrapis, being a liberal and partially Westernised family, enjoy illicit wine – although they are almost found out and punished horrifically.

For Marjane, it is Western popular culture that allows her a rebellious outlet. She buys covert tapes of western groups and begins collecting an incredibly eclectic array of musical passions and influences: she listens to Iron Maiden, Camel, Kim Wilde and Michael Jackson, and dresses as a punk rocker. She becomes more rebellious, skipping school at one point (to her mother’s rage), stealing (and failing to enjoy) a cigarette, and arguing with her teachers. Her parents even devise ingenious techniques for smuggling rock posters from Turkey into Iran. Satrapi writes of the Iran she knows, the one behind the headlines which depict a fearful theocratic menace, and depicts the many little rebellions which occur behind closed doors.

Knowledge and Learning

The Islamic Republic is depicted in Persepolis as a regime which relies in part on disinformation and ignorance in order to control its population. Control of universities and schools is thus essential, and the memoir features many instances in which Marjane’s school curriculum is suddenly changed to suit political needs, or when she feels compelled to challenge a blatant lie from her teachers. The universities are temporarily closed throughout Iran; the relevant minister claims that all syllabuses are somehow “decadent” and that it is thus “better to have no students at all than to educate future imperialists.”

The Satrapi family, accordingly, are passionate believers in the importance of knowledge and education, which they see as crucial tools against authoritarianism. “To enlighten me,” Marjane recounts, “they bought books.” She reads up on radical history and European political philosophy. Her father does his best to ensure she has a working knowledge of recent Iranian history so that she can contextualise and better understand the era in which she lives. Ebi is a role model for Satrapi in this regard. His most active role in the streets during the Revolution is to record it for posterity, to collect evidence and to spread knowledge. He does this through photographing the turmoil on the streets. Satrapi makes it clear that this is not an easy or safe option – it is “strictly forbidden” and “he had even been arrested once but escaped at the last minute” (29). Ebi sees the widespread acceptance of the Islamic Regime’s suspiciously high percentage of the vote in the elections following the Shah’s abdication as indicative of “ignorance,” and so he and Taji work to ensure that Marjane is better prepared than many to face the deceptions of power. Marjane is somewhat confused by her mother’s fury at her bludging from school, labelling her a “dictator.” Taji, however, understands that “now is the time for learning,” reminding Marjane that education is not a chore, and nor does it merely give her an advantage over others. Rather, it is a matter of life and death; if Marjane intends to “survive” under the regime, she must smarten up.

Education can bring its own threats to liberty, however. Marjane finds it increasingly difficult to listen to or obey her teachers as it becomes more and more obvious that they merely preach propaganda. She is expelled from one school, and at the next gets into a passionate argument with her teacher. The teacher blithely assures her students that “Since the Islamic Republic was founded, we no longer have political prisoners” (144). Marjane is outraged at this bare-faced lie and challenges her: “We’ve gone from 3000 prisoners under the Shah to 300,000 under your regime… How dare you lie to us like that?” This lands her in trouble with the school, and her father proudly comments that “she gets that from her uncle.” Taji, however, has a slightly more realist outlook: “Maybe you’d like her to end up like him too? Executed?” Marjane finds herself in a dangerous situation for a precocious teenager; her parents have educated her so that she can tell a lie from the truth. However, that knowledge is inherently dangerous in a society which punishes, with extreme violence, the acquisition of knowledge that does not suit their political interests. The Satrapis recognise the danger in which Marjane could so easily find herself and so they decide to privilege her education over other considerations. She needs to learn somewhere where ideas are free to flourish, and where it is safe to flex her audacious and sharply intelligent mind. Marjane’s parents thus decide to send her to study in Austria. She is only fourteen; but as her mother asserts, “above all, I trust your education.”

Gender and Patriarchy

The fundamentalist interpretation of Islam which characterises the Islamic Republic is an extraordinarily repressive and violent kind – especially towards women. The struggle to control women is introduced immediately, in the very first panel of the graphic novel. Marjane is depicted, staring at the reader, in a veil. Satrapi explains that there was a “cultural revolution” which swept through Iran and resulted in the veil being made mandatory. We learn that Taji had to dye her hair and change her appearance after being photographed protesting against the imposition of the veil. The panel depicting her walking, face down, with sunglasses and a scarf, through the interrogating gazes of bearded fundamentalists, is a frighteningly literal depiction of the scrutiny women in the regime are subjected to. Back at school, Marji and her friends also resent the veil, and Taji is shocked at how unrecognisable the veil makes her on her passport photo. It is an imposition which becomes symbolic of the attack against freedom throughout the novel.

It was imposed, in part, by a male, patriarchal order – but the religious zealots determined to control the bodies of women were not exclusively male. Indeed, when Satrapi recounts the streets being full of protests for and against the veil, the pro-veil crowd are depicted entirely as being women. Similarly, it is the women’s branch of the Revolutionary Guard who accost Marjane as she walks through the streets dressed as a punk. They police her clothing and threaten to whisk her away to their dreaded Headquarters. “Lower your scarf, you little whore!” one of the Guardians snarls.

The sexualised language employed by the Guardians is borrowed from their male counterparts, and is typical of the manner in which women are regulated under the regime. This can make parts of Persepolis very difficult to read. The fate of Niloufar, an eighteen-year-old Communist who falls foul of the regime, marks the extent to which women have become chattel: she is “married” – that is, raped under the guise of a ceremony – and executed, and a pathetic dowry equivalent to five dollars sent to her relatives. Marjane’s own mother is accosted by thugs for not wearing the veil, and again the language is that of sexual control and violence: “they said that women like me should be pushed up against a wall and fucked, and then thrown in the garbage.” Such scenes of course also highlight the hypocrisy, which would be absurdly amusing if it wasn’t so horrific, of the mentality of the regime: this sort of bestial violence is justified because without veils women are allegedly not “civilised” enough.

It is not just physical violence which restricts women under the new regime, however. More insidious but just as destructive is the limiting of opportunities. When Marjane learns of the university closures, she is distraught. She will not be able to follow in the footsteps of her hero, Marie Curie: “Misery! At the age that Marie Curie first went to France to study, I’ll probably have ten children.” It is this imagined fate which makes Marjane’s move to Austria so vitally necessary.

The Iran-Iraq War of the early 1980s forms the backdrop to much of the first part of Persepolis . The war is ignited when Iraq invades; it is prolonged, however, by Iran, for the purposes of control. When the fighting begins, Marjane is all fire and brimstone: “We have to bomb Baghdad!” she cries. Her belligerence is soon tempered by the growing realisation that Iran is depending on the war to rally its people around the new regime. Belligerent slogans are painted on walls; the (theoretically) banned Iranian national anthem is broadcast, and the girls in Marjane’s school are compelled to engage in bizarre ritualistic mourning. The newspapers devote pages to the swelling ranks of martyrs. Iran suffers heavy casualties, but has a vast population to draw upon. Their techniques disturb Marjane. Young boys are sent a key – representing the key to Paradise available to martyrs slain in battle – and then enlisted. Shahab explains exactly how the military whips these inexperienced boys into a frenzy:

They come from the poor areas, you can tell… first they convince them that the afterlife is even better than Disneyland, then they put them in a trance with all their songs.

The result is “absolute carnage.” A peace is actually offered, with generous terms, by Iraq, and Saudi Arabia offers to pay for reparations. However, “the survival of the regime depended on the war,” and so Iran refused the “imposed peace” and commit to more unnecessary bloodshed. The regime becomes more repressive, and mass executions become common. Persepolis lays bare the reality of sabre-rattling regimes; their real enemy is usually their own people. As Ebi chastises his warmongering daughter, “The real Islamic invasion has come from our own government.”

Family and Childhood

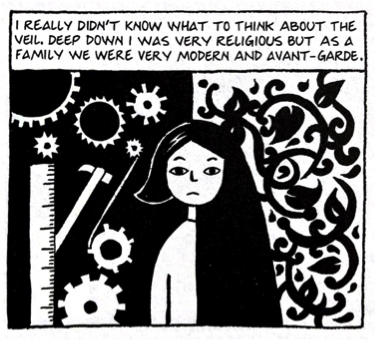

The first part of Persepolis is entitled The Story of a Childhood and that, primarily, is what it is. Marjane’s family has an immense impact on her life, providing her with the freedom and self-awareness to develop a strong individual personality. Her childhood is a mixture of competing impulses: “Deep down I was very religious but as a family we were very modern and avant-garde.” When as a young girl she decides she is destined to be a Prophet of Islam, her parents angrily defend her against the worries of her teachers. They buy her books and encourage her always to think freely and critically. Ultimately they make an extremely painful decision: to send Marjane away from them to Austria. As hard as it is, they do this out of love: they hope Austria will be safer and freer for her.

Marjane must grow up quickly in a world which does not leave much room for the innocence of childhood. Before she is fourteen, she has her parents threatened, must flee a violent demonstration, has an uncle executed and a friend’s house bombed. This last, an incident which kills the entire household of her neighbours, is described in a single, black panel: “No scream in the world could have relieved my suffering and my anger.” Marjane grows up experiencing traumas that children should not have to experience. Although she clashes with her parents frequently, she does find solace in the stability of her family and their connection to the past, pledging to Anoosh that she will never forget the suffering of the Satrapis. The final advice Marjane is given from various family members is to stay true to herself and to remember where she came from – and whom she came from. Persepolis is as much a testament to the bravery, character and love of her family as it is a story of an individual girl.

- “At one of the demonstrations, a German journalist took a photo of my mother. I was really proud of her.” (5) Satrapi demonstrates depicts her younger self being inspired by her dissident and free-thinking other early in the graphic novel.

- “After a long sleep of 2500 years, the Revolution has finally awakened the people.” (11) Marjane’s father, Ebi, teachers her to view contemporary politics in the context of thousands of years of history, better allowing her to critique the justifications for power employed by regimes.

- “Now that the devil has left!” (43) Like millions of Iranians, the Satrapis are delighted at the Shah’s abdication. However, Satrapi foreshadows the emergence of a new repressive regime by depicting the metaphorical devil derided by her mother curling around the frame of the panel, as if closing in to further tighten its grip.

- “I never imagined that you could use that appliance for torture.” (51) The discussion between the Satrapis and their old friends Siamak and Mohsen has a profound influence on Marjane, who was taught at school that the Shah governed by divine right. She now understands that the Shah’s power actually depended on extraordinary brutality.

- “All torturers should be massacred!” (52) The personal politics of oppression are deeply confusing for Marjane, as her own mother, who spoke regularly of the value of mercy and forgiveness, cries out for the slaughter of torturers. Gradually Satrapi comes to understand that there are no easy or correct ways of processing anger and the desire for revenge.

- “And that is how all the former revolutionaries became the sworn enemies of the republic.” (67) Satrapi illuminates the fundamental similarities between all repressive regimes by demonstrating how the new Islamic regime quickly hunted down and eliminated the men and women who had challenged the rule of the Shah.

- “Without parties, we might as well bury ourselves now.” (106) The Islamic Republic uses horrific violence to prevent public forms of disobedience, so the people of Iran must find private ways to escape and rebel. In this quote, Satrapi presents the idea that perhaps some things, like celebrations, are so fundamental to humanity that they are worth risking death – because without them one would be as good as dead.

- “Those who opposed the regime were systematically arrested… and executed together.” (117) Using war as an excuse for brutality, the new Iranian regime focuses on solidifying its power and slaughtering anyone who could possibly oppose it. This quote highlights the fact that repressive regimes are fundamentally built on violence.

- “All bilingual schools must be closed down.” (4) Within the opening pages of Persepolis Satrapi makes it clear that regimes depend in part on brainwashing children whilst they are young. Primary schools are targeted as the perfect sites for teaching propaganda and instilling strict gender norms; boys and girls are thus separated from one another.

- “To enlighten me, they bought books.” (12) Satrapi’s parents believe in the value of education and the written word, and thus decide that arming Marjane with books is the best way to prepare her for the tumultuous political future facing the country. From her books she learns about revolutionaries and develops a strong sense of social justice.

- “Children, tear out all the photos of the Shah from your books.” (44) Symbolic attempts to erase history occur in Marjane’s school. Marjane’s father is usually careful to ensure that his daughter understands current events in their historical context, and Marjane challenges the teacher’s hypocrisy – and is punished. Marjane begins to realise that she cannot trust her country’s education system.

- “The Ministry of Education that universities will close at the end of the month.” (73) The new Islamic regime depends on unquestioning – and even better, unthinking – obedience. For this reason, universities, which at their best teach their students to challenge accepted ideas and power structures, are targeted and closed. Thus, physical violence is coupled with softer forms of control, such as control over what information and knowledge can be accessed.

- “Now is the time for learning… In this country you have to know everything better than anyone else if you’re going to survive!!” (113) As the situation becomes darker in Iran, Marjane’s mother emphasises the importance of education even more firmly, arguing that it is the single most important tool for survival.

- “Above all, I trust your education.” (147) Finally, the Satrapis decide that Marjane’s fiery temperament and love of knowledge have rendered Iran a dangerous place for her to stay. In order to make sure she can learn more freely they send her to Austria – trusting the knowledge they have given her will keep her safe.

- “We didn’t really like to wear the veil, especially since we didn’t understand why we had to.” (3) Satrapi opens her memoir as a ten-year-old girl, confused by a strange new requirement. The introduction of the veil becomes symbolic of the repression of women throughout Persepolis , is included this early in the context of a schoolyard in order to demonstrate the strangeness of religious law in its intersection with childhood.

- “Everywhere in the streets there were demonstrations for and against the veil.” (5) Whilst clearly used by men as a way of regulating the behaviour of women, the imposition of veil-wearing in Iran was supported by some women, suggesting that Iranian society is complex and divided.

- “I wanted to be an educated, liberated woman, and if the pursuit of knowledge meant getting cancer, so be it.” (73) Marjane takes as one of her many idols the great scientist Marie Curie, demonstrating her fundamentally progressive and egalitarian nature – and the threat posed to her dreams by the at times brutally misogynistic regime which rises to power in Iran following the Revolution.

- “They said that women like me should be pushed up against a wall and fucked. And then thrown in the garbage. And that if I didn’t want that to happen, I should wear the veil.” (74) Marjane’s mother is subjected to the brutally misogynistic threats that the regime and its sympathisers employ in order to intimidate and silence women.

- “Compared to Iraq, Iran had a huge reservoir of potential soldiers. The number of war martyrs emphasised that difference.” (94) In a darkly ironic moment, Satrapi reveals the horrible truth at the heart of the Iran/Iraq War – the only advantage held by Iran is the sheer number of its men it can have killed. Satrapi uses that fact to highlight the senseless and self-destructive nature of war.

- “They put on funeral marches, and we had to beat our breasts.” (95) Satrapi depicts the role of ritual in brainwashing a population into uncritically accepting warfare. She achieves this by drawing rows of barely distinguishable girls in veils staring, wide-eyed and clearly somewhat bewildered, straight at the reader, with splash effects around their hands emphasising the physical nature of the ritual. The image highlights the intention behind the ritual: to enforce social conformity.

- “It’s nuts! They hypnotise them and just toss them into battle. Absolute carnage.” (101) Shahab recounts the manner in which young men are brainwashed and hypnotised. They are tempted with the prospect of a glorious afterlife and them put into a “trance” with patriotic songs. Above all, Satrapi emphases that the regime picks the young and ill-educated, people most likely to be impressionable, and thus creates the illusion of patriotism. This is part of the reason why Marjane’s parents value education so highly.

- “They eventually admitted that the survival of the regime depended on the war.” (116) The Iranian regime depends on distracting the population from its own atrocities with the war, and by justifying its oppressive tactics by claiming that they are necessary in wartime. Marjane feels “sick” when she realises that up to a million people have died simply so that the authoritarian regime of Iran can cling onto power.

Childhood and Family

- “Deep down I was very religious but as a family we were very modern and avant-garde.” (6) Marjane Satrapi was born into an essentially secular family, and, as this quote shows, she spent many years grappling with religion and secularism before eventually abandoning her faith.

- “The emperor that was overthrown was Grandpa’s father.” (22) The revelation that the Satrapis are descended from what was at one point royalty is important for two reasons. Firstly, it helps the young Marjane understand her place in history, relate current events to the past, and understand some of what her family has suffered. Secondly, it demonstrates the fact that the Satrapi family believed in the importance of knowledge. Ebi gives this knowledge to his daughter so that she might better understand the world around her.

- “During the time Anoosh staid with us I heard political discussions of the highest order.” (62) Marjane learns much of the history and political situation of Iran from her family. She is particularly inspired by her uncle Anoosh, whom she terms a “hero,” and his execution by the Islamic regime is a deeply distressing moment of disillusionment for her.

- “Dictator! You are the Guardian of the Revolution of this house!” (113) The education and passion for freedom instilled in Marjane by her parents at times puts her at odds with them. For example, she cannot fully understand why her mother, who seems so rebellious in other areas of her life, should be furious that Marjane has skipped school. The answer is of course that she understands how crucial knowledge is to survival in regimes like the Islamic Republic, even if Marjane is too young to see that yet.

- “No scream in the world could have relieved my suffering and my anger.” (142) The death of the Baba-Levys, the Jewish neighbours of the Satrapis, is one of several turning points in Marjane’s life. Still a young girl, she has heard tales of torture from family friends, had an uncle murdered by the Islamic Republic, been threatened by religious police, and now lost a friend to the war. Satrapi depicts the emotional devastation suffered by children in war zones by simply drawing a black square – emphasising the impossibility of a child truly reconciling themselves with this sort of tragedy.“We feel it’s better for you to be far away and happy than close by and miserable.” (148)Marjane’s parents ultimately demonstrate the depths of their love for their daughter by sending her to Austria in order to be safer, freer, and better educated. This is painful for them, and the final image of the first part of Persepolis is of Marjane staring, horrified, at her fainting mother.

Marjane Satrapi

Marjane Satrapi is nine years old at the outbreak of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Persepolis is told from her perspective as she navigates childhood and adolescence in a world which continuously shifts under her feet. The memoir opens with an image of her staring directly at the reader, wearing a veil. One of the main themes of the graphic novel, Marjane’s attempt to understand her changing world as she grows up in it, is captured in her early statement of confusion about the way her society has suddenly changed: “We didn’t really like to wear the veil, especially since we didn’t understand why we had to.”

As a young child, Marjane exhibits the symptoms of Iran’s rich and occasionally contradictory culture. She has a strong spiritual side to her nature, but describes her family as “very modern and avant-garde.” She convinces herself, as a six-year-old, that she is destined to become the next great prophet of Islam – although she takes as much if not more inspiration from the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism. Between her secular parents, ancient Zoroastrian past, and predominantly Muslim contemporary society, Marjane finds herself fusing a number of philosophies together. When the Revolution begins, she turns to politics and political philosophy, drawing inspiration from the revolutionaries of her own country as well as further afield, and from Marxist notions of dialectical materialism. She develops a strong sense of social justice, especially regarding her maid, Mehri, whose romance with a neighbour is broken off after her true social status is revealed.

Marjane grows increasingly forthright and passionate over the course of the memoir. Her growing political awareness is, however, frequently tempered by moments of profound disillusionment. The execution of her beloved uncle Anoosh is one such moment. Her attitude towards war is also forced to develop in complexity. At the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War she is very belligerent, calling for retaliatory strikes against Iraq and initially angry that her father has no interest in signing up to fight. As the war drags on and she learns about Iran’s techniques, however, she becomes increasingly disillusioned. She learns of the brainwashing and trickery employed by the military to encourage young boys to fight, and then comes to realise that Iran has rejected generous peace terms because the regime has become dependent on using the war as justification for its draconian measures. The thought makes her feel “sick,” and she reflects that “A million people would still be alive” had the regime accepted the peace offered by Iraq and supported by Saudi Arabia.

As her views develop, Marjane becomes increasingly rebellious. She dons Western fashions until caught by the Guardians of the Revolution, and covertly buys illicit tapes of American pop groups. She is frequently disobedient and contrarian at school, challenging teachers and speaking her mind. Admirable as it is, this disobedience eventually sees her expelled. Her parents decide that her rebellious nature and thirst for knowledge should be nurtured somewhere safer, and so they send her to study in Austria.

Taji Satrapi

Marjane’s mother is surely a crucial influence on the young girl. A thoroughly modern woman with no time for religious dictates, we first encounter Taji Satrapi at a rally against the imposition of the veil (and in the second part to Persepolis it is revealed that Taji’s favourite writer is the French feminist Simone de Beavoir). This introduction to her character highlights the two sides to Taji which have a decisive impact on her relationship with her daughter over the course of the book. She is clearly idealistic, passionate, and happy to stand up for her rights. After she is photographed at a rally, however, and that photograph is picked up and printed by papers all over the world, she dies her hair and makes other efforts to disguise herself. She is thus also deeply pragmatic. She instils in Marjane a strong sense of equality and personal freedom, but confuses the young girl when she cracks down on her for skipping school. Taji stresses that survival under regimes such as the Islamic Republic require education and pragmatism. When Ebi, her husband, is initially proud of Marjane for getting herself expelled, Taji angrily reminds them both that Anoosh, Ebi’s brother, paid the ultimate price for his rebellious nature.

For all that their relationship is occasionally fraught, Taji is a loving and devoted mother to Marjane. Despite occasional (and given the context, justified) outbursts of vengeful rage, she always stresses the importance of compassion and forgiveness to her daughter: “It is not for you and me to do justice,” she tells her daughter after Marjane discovers that the father of a classmate worked in the secret police under the Shah. “I’d even say we have to learn to forgive” (46). It is an important lesson that Marjane tries to take to heart.

Ebi Satrapi

Ebi Satrapi, Marjane’s father, is in some ways the epitome of the westernised Iranian. He drives a Cadillac, listens to Pink Floyd, drinks alcohol and deplores Islamic theocracy. However, he is not naïve or in any way ignorant to the evils of the Western world, either; he takes what he sees as the best elements of both worlds and reconciles them. This act of synthesis is characteristic of Ebi, and at times contradictory; he is a devoted Marxist but enjoys a privileged life, including the employment of a maid whose romance he scuppers by revealing her social status.

Ebi, like Taji, is a strong believer in the power and value of education. He buys books for his household in their scores and he carefully relates the historical background of the Revolution to Marjane. He is a radical, friendly with political prisoners such as Mohsen and Siamak (and of course his own brother, Anoosh). He participates in the demonstrations against the Shah, and, characteristic of a man to whom knowledge and education is so important, contributes by recording events for posterity, taking photos of the turmoil in the streets even though such an act is “strictly forbidden.” He is cautious, and teaches Marjane not to trust the word of the regime, insisting instead on double-checking every item of news with the BBC. He is earnest and politically passionate but also has a wry sense of humour; when a belligerent Marjane complains that the Iraqis are historic enemies of Iran eager to invade, her father replies, “And worse, they drive like maniacs.” He even admits, to Taji’s disgust, to being fond of Iron Maiden.

Ebi Satrapi does his best to prepare his daughter for life, and to make sure she is equipped to fight ignorance and prejudice where she finds it. His portrayal in Persepolis , like Taji’s, is sympathetic and very warm.

Marjane’s Grandmother

Marjane takes inspiration from her maternal grandmother, whose husband was connected to the aristocracy prior to the Shah’s regime. When he was arrested, she was left to raise her children alone and in poverty. She is warm and unfailingly kind, with a keen sense of humour, positing herself as “Grandma Martyr” as she laughs along to an anecdote from Ebi about an old woman who is mistakenly identified as the widow of a revolutionary martyr. She is also quick-witted and resourceful; when Revolutionary Guards come to investigate the Satrapi family home, suspecting there to be alcohol inside, she convinces one of the guards that she must enter immediately because she has diabetes and requires sugar syrup. She then quickly disposes of the illicit beverages.

Marjane’s grandmother has many of the same characteristics as Ebi and Taji, in terms of kindness and political convictions. In one of her longer pieces of dialogue, the night before Marjane flies away, she gives her granddaughter powerful words of advice:

In life you’ll meet a lot of jerks. If they hurt you, tell yourself that it’s because they’re stupid. That will help keep you from reacting to their cruelty. Because there is nothing worse than bitterness and vengeance… always keep your dignity and be true to yourself. (150)

Although not always kept by Marjane over the two graphic novels, these words form something like the moral of Persepolis , and they ring throughout the introduction Satrapi writes.

Uncle Anoosh

Anoosh is a paternal uncle of Marjane’s. He is a long-time political radical whose persecution led to him fleeing to the U.S.S.R, where he started a family, eventually separated from his wife and tried to return to Iran. In Iran he was arrested and imprisoned for nine years. He and Marjane develop a close bond in the short time they have together. As the situation in Iran darkens, Satrapi depicts Anoosh’s slow loss of optimism, as his refrain of “Everything will be alright” grows more and more despondent. He tells Marjane that it is important that she never forgets the past, and never forgets the suffering of their family. She pledges that she will not.

When Anoosh is eventually arrested and executed as a “Russian spy,” his death leaves Marjane “lost.” It is one of the first traumatic encounters she has with the regime, having been insulated from much of the turmoil thus far. Her pledge to never forget the lives taken by various regimes is one of the cornerstones of Persepolis .

Siamak Jari and Mohsen Shakiba

Simak and Mohsen are two of the 3000 political prisoners released after the fall of the Shah. They recount the horrors they endured as political prisoners and thus introduce Marjane for the first time to some of the realities of repression. She is horrified at their descriptions of the tortures meted out to them.

Once the Islamic Republic is established, enemies of the old regime are quickly marked out as enemies of the new regime. Mohsen is found drowned in his bathtub – with only his head submerged, clearly demonstrating that it was an act of murder. The Revolutionary Guard arrive at Siamak’s house, but he had already fled with his immediate family, across the border, disguised as sheep. His sister was murdered in his place.

The encounters with Siamak and Mohsen are brief, but they are important. Their murders (or attempted murders) mark a turning point in the regime, as it becomes explicitly violent and repressive. Their presence in Marjane’s life mark the increasing presence of the regime in her life also.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Persepolis -1

Introduction to persepolis-1.

Persepolis is a masterpiece of Marjane Satrapi, an Iranian rebel who fought for her rights and freedom. The book is a graphic novel , originally written in bande dessinees in French. The author went into exile after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran. The comic book, the first of its kind written and illustrated by the author from 2000 to 2003. It was released in four volumes as published by L’ Association. Later, it was translated and published in English in Europe. The book has also been used at a play successfully in theatres. This is the first in the series of four, presenting the childhood of Marjane up to her migration to Austria.

Summary of Persepolis-1

Persepolis 1: The Story of a Childhood

The storyline of the first book introduces a ten-year-old girl, Marjane, who happens to be the protagonist of the novel. The novel is set in the 80s, detailing the experience of the young girl during the turbulent periods of the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran when she first learns about the veil and status of women. It happens that the author goes through the turbulent period of religious extremism and the ensuing war between Iran and Iraq. Tehran was ruled by Shah, the dictator who imprisoned many Princes one among them was Marjane’s grandfather who happened to be a Persian Prince.

As a member of an elite social class, Marji is mostly involved in reading books and educational material which make her come to know western political thoughts. She immediately reverts to the political orientation of her family, which leads her to take part in the existing political mobilization against the regime of Shah. The movement is about ousting Shah and sending him into exile. When this takes place, she gleefully sees the unfolding of the Islamic Revolution and the rise of religious extremism that takes its toll on the young girls.

She studies in a French co-educational school with non-religious teaching and her parents being very liberal and open to western ideas. Her mother protested against the veil in the streets which was captured by the newspapers and magazines. Marji was so proud of her parents and westernized ideology. In spite of their modern ideas, the family was religious. Marji always fantasized of being the last Prophet even though there are no female prophets. She shared this idea at school and people mocked her. Once, when she was fantasizing about the prophethood in front of other students, her teacher overheard and called for her parents. Although they defended before the teacher, they asked her about it at home and she simply lied that she meant to become a doctor. At this point, she was a very religious person and wanted to be the instrument of God.

She finds that Anoosh, her uncle, often visits the family to orient her about the political situation and relates the stories of the arrest of the communists in the country. These stories create a sense of resistance in her that leads her to view the new Iranian clerical regime with some suspicion despite some governmental reforms, and she happens to be correct that the social restrictions slapped on the people make them flee to Europe. During this time itself, she learns from her mother that her grandfather was Persian Prince and died in the water cell. However, her uncle Anoosh soon faces the music and is thrown behind the bars. He is soon sent to gallows which frustrates the dreams of Marji when she does not see God coming to help the poor prisoners and the people. Therefore, abandoning her faith, she moves out of the country for vacation.

When she returns after the vacation, she comes to know about the Iran-Iraq war and its impacts on the public. The main source of the new items and commentary is her grandmother. Living in Tehran makes her constantly fear the air raids of the Iraqi air force, and they move to the bunker in the basement of their house. Later, she learns about the national anthem on television and about the pilots protesting in the prisons to be released to take part in the war. She and her family soon find themselves on the other side of the fence, when they start partying and consuming alcohol, considered illegal on religious grounds. She also starts skipping classes and meeting boys, a thing not considered appropriate in the new regime.

With Iran-Iraq raging in the background, Marjane soon finds herself caught in the crosshair when a missile hits their street with her family having a close shave. The missile, however, causes causalities in the Jewish neighborhood. Marji, seeing the debris, lashes out at the regime for initiating a war, and soon fearing reprisals, the entire family moves to Austria for safety.

Major Themes in Persepolis

- Childhood: Persepolis presents the story of a childhood and the impressions that Marjane holds about politics and religion. However, they have less impact on her until she enters adulthood and smokes for the first time. Her argument is that children are extremely vulnerable to ideological and violent events whether they are liberalizing or restricting the social fabric. When she comes to know about the overthrowing of the regime, she feels jubilation little knowing that the Islamic clerical regime would make life difficult for liberal families like theirs. However, when they feel the restrictions increasing in their country, she finds herself in Austria, ruminating over her gone childhood.

- Politics: Although the novel is promoted as an autobiography of Marjane Satrapi with some character sketches of her family, yet deep down it has a political theme that is when revolutions and changes occur in the political administration, it does not mean that they would be beneficial for all. For example, Marjane does not understand the meanings of a veil and yet when it is imposed, the atmosphere becomes stifling on the political front. Her view that the ordinary people, too, change with the government proves a smokescreen to her when her family faces oppression on account of their liberal lifestyle. Therefore, it is where politics enter the personal lifestyle of an individual.

- Past and Present: This graphic novel, Persepolis , is about Marjane’s past and also about her present life, including the past of the empire and the tension of modernity in present-day Iran. When the novel starts, Marjane takes the reader to the past of the empire and its traits of tolerance and love. However, when the revolution takes place and the violence of war reaches the doors of the citizens, she comes to know how religion becomes a tool for spreading intolerance. As the novel moves forward, her pride in her historical background merges with her love for her homeland, and yet she is to leave it on account of the suppression that the new regime has brought.

- Bildungsroman : The self-actualization, formative years of a person or bildungsroman of Marjane occurs when she learns that she had to grow up too soon and that her childhood was lost in hope and expectations of a better future in Iran. However, her journey from childhood to adulthood and then back and forth journey in memory highlights that she has become fully aware of the political consequences of the changes that her country and countrymen have witnessed during the change from one regime to another regime. When war is imposed on the people, she comes to know how one is forced to leave her home. This awareness and self-actualization go with her in her graphics images and conversation.

- Class Conflict : The novel also demonstrates the theme of conflict. Although Marjane did not highlight it explicitly, her lifestyle and family orientation show that despite speaking about the western democratic ideals, she still enjoys the elite lifestyle of having a Cadillac and a maidservant at home. On the one hand, she enjoys a luxurious lifestyle and on the other hand, she expects revolution to bring changes in the lives of the poor people. This conflictual undertone moves with the novel and her story until the end when Mr. Satrapi spurns his daughter that their maid, Mehri, cannot marry outside of the class despite harboring Marxist views, a hypocritical act.

- Fundamentalism: Religious fundamentalism is another theme of this graphic novel. Iranian society faced the issue of religious intolerance and extreme religious beliefs in the wake of the Islamic Revolution of 1979. When the Shah regime was ousted, the western cultural demonstration became a thing of the past, and families having western orientation became the butt of the religious strictures. Marjane and her parents faced severe issues when western outfits, food, and values were constantly on the receiving end. That is why she has targeted the extreme ideals of the religious beliefs in the shape of God and other religious values propagated by the religious clergy.

- Freedom of Imagination: Freedom of imagination and freedom of expression is another major theme in that Marjane, as a child, thinks that she could be a prophet and stand up for justice , and yet she fears that in case it becomes clear to the religious clergy, she would face persecution. The same happens to their political and social views as they were entirely against the power structure established by the religious regime.

- Familial Relationship: Family and relationships are other major themes on account of the presentation of childhood and parental life during a political transition in Iran. The Satrapi family faces severe backlash on account of their political orientation. Amid this backlash, they shower love on their children who in turn tell them that they are a privileged class despite showing their leanings toward Marxism, a classless social structure.

- Contradictions of Life: Marjane also learns contradictions in social life in Iran. She comes to know about Marxism as the way of social equality but then Mehri cannot marry out of her social class as her father opposes it when he comes to know about it. She also comes to know strange things that if God has brought Shah to power, why He has helped revolutionaries, and if God comes to her why their schools have been closed.

Major Characters in Persepolis-1

- Marjane: As the author of this graphic novel, Marjane Satrapi is a major character as well as the protagonist of the first part in which she opens up about her childhood, her memories of her parents, her family, her political orientation, her school, her relations and overall situation in her country. She comes to know about religion and thinks of herself as a prophet and yet loves her country despite having a religious revolution in Iran. During the protests and war, she demonstrates her love for her country, but she also dislikes to abandon her social orientation of the western values, though, Mehri’s love affair, too, saddens her that equality has not taken firm roots even in their own family. Finally, she leaves her French school for Austria for education after oppression from the clerical regime.

- Satrapi: Mr. Satrapi is the head of the family and also the head of his father’s family due to his position and status in society. A well-educated Marxist, he is a silent revolutionary unlike his brothers Anoosh and uncle. His upbringing of his children as having western education shows his personality orientation of western values. His political education of his children makes him stand out in the family and yet he shows class discrimination when it comes to the marriage of their maid, Mehri.

- Satrapi: Although Mrs. Satrapi is leading a privileged life, her poor background peeps through her insistence on the education of her children, which she sees as a solution to the social ills. Even during the oppression of Shah and transition to revolution, she insists that her children stay connected to their studies and do not waste their time. That is why when it comes to more repression, she prefers to leave the country, move to the west for her children’s education.

- Grandmother: The role of grandmother is significant in the story as she connects Marjane to a royal family, for her grandfather was the former emperor. Yet, her husband harbored communist ideas and jailed for supporting revolutions that have had impacts on her in that she has become suspicious of the incumbent government. Like her Taji and Ebi, she expects her granddaughter to excel in her studies and take part in politics to excel in life.

- Annosh: The character of Anoosh is significant as he faces frequent arrests on account of his political views. However, his role becomes prominent on account of his communist ideals. He is later arrested and executed for being a Russian agent.

- Mehridia: Mehridia or Mehri as she is known in the family circle, is a maidservant working with the Satrapi’s. She develops a love relationship with the boy of the neighbor and stays in contact with him through love letters written by Marjane. However, when Mr. Satrapi comes to know about it, he strongly discourages Marjane as well as Mehri, reminding her of her social status that confuses Marjane, too.

- Siamak: A heroic figure in her eyes during the revolution, the Savak police arrest him and torture him until the revolution succeeds. However, strangely, he also becomes a fugitive during the Islamic revolution. He leaves Iran, hiding among sheep when being transported out of the country.

- Mohsen: A friend of the Satrapi family, he also faces torture at the hands of the Shah’s police. However, later the Islamists kill him and propagate his death as a suicide.

- Mali: A friend of the Satrapi family, she often comes to live with the family during the war years on account of the bombing of her town located on the border. Despite them being from a wealthy family, they are nearly homeless, living on the streets due to the war and bombing.

- Taher: The character of Taher is a significant but minor character from the Satrapi family. He has chronic heart disease and dies of cardiac arrest.

Writing Style of Persepolis -1

Despite being a graphic novel, the author’s writing style has a unique quality, especially with witty dialogues . As far as the language is concerned, it suits the graphic novel of this type having black and white drawings. Appropriate titles, dialogues, and simple vocabulary become the hallmark of its effectiveness in communicating the political upheavals of a third-world country like Iran. To stress her feelings, Marjane often turns to metaphors and similes more than any other literary device.

Analysis of the Literary Devices in Persepolis -1

- Action: The main action of the novel comprises the childhood of Marjane Satrapi in her journey toward adulthood. The falling action occurs when she comes to know that the revolution is going to confine them behind veils and that the bilingual schools are going to face closure. The rising action occurs when she sees that Shah is going into exile.

- Allusion : The novel shows good use of different allusions as given in the examples below, i. In 1979, a revolution took place. It was later called “The Islamic Revolution.” (3) ii. The first three rules came from Zarathustra. (7) iii. Followed by the Mongolian invasion from the east. (11) iv. I knew everything about the children of Palestine. (42) v. About Fidel Castro (42). vi. The BBC said there were 400 victims. (42) The above examples show perfect allusions. The first example refers to the Iranian revolution of 1979, the second to the ancient Iranian philosopher, the third to Mongols, the fourth to Palestine, the fifth to the Cuban leader, and the last to the British Broadcasting Corporation.

- Antagonist : One of the antagonists in the novel is Marjane’s teacher who separates the girls from the boys. The second is the Savak, the secret police of Shah and the last is the Islamist regime.

- Apostrophe : The novel shows the use of the apostrophe as given in the below example, In the name of the dead million, we’’ teach Ramin a good lesson. (45) This example shows the use of apostrophe that is to call somebody who is absent or dead. Here Ramin is not present.

- Conflict : The novel shows both external and internal conflicts. The external conflict is going on between Marjane’s family and the regime, whether it is Shah or the Islamic one. The other conflict is the mental conflict that is going on in the mind of Marjane about her faith and her understanding of the world around her.

- Characters: The novel, Persepolis, shows both static as well as dynamic characters. The young girl, Marjane, is a dynamic character as she shows a considerable transformation in her behavior and conduct by the end of the novel. However, all other characters are static as they do not show or witness any transformation such as Mr. Satrapi, Mrs. Satrapi, Uncle Anoosh, Mehri, and her grandmother.

- Climax : The climax in the novel occurs when her father advises her not to help Mehri to marry the neighboring boy as she is not of their class.

- Foreshadowing : The novel shows many instances of foreshadows as given in the examples below, i. In 1979, a revolution took place. It was later called “The Islamic Revolution.” (3) ii. At one of the demonstrations, a German journalist took a photo of my mother . (5) The mention of revolution and then of demonstration show that the coming events are not going to be about peace. Therefore, it shows the future that seems bleak for Marjane in Iran.

- Hyperbole : The novel shows various examples of hyperboles are given below, i. At the age of six I was already sure that I was the last prophet. (6) ii. I wanted to be a prophet (6). iii. Yes you are my celestial light, you are my choice, my last and my best choice. (8) iv. “2500 years of tyranny and submission” as my father said. (10) All of these examples exaggerate things as she cannot be a prophet and that there could never come celestial light to choose her and also tyranny could no be prolonged to 2,500 years.

- Imagery : Imagery is used to make readers perceive things involving their five senses. For example, i. The material world does not exist. It’s only in our imagination. (12) ii. You mean that even though you see this stone in my hand, it does not exist since it’s only in your imagination? (13) iii. That night I stayed a very long time in the bath. I wanted to know what it felt like to be in a cell filled with water. The above examples show images of feelings, touch, and taste.

- Metaphor : Persepolis shows the use of various metaphors as given in the examples below, i. Today my name is Che Guevara. (10) ii. I am Fidel. And I want to be Trotsky. (10) The above examples show that each time the author compares herself to persons like the revolutionaries.

- Mood : The novel shows various moods; it starts with an innocent and jubilant mood but turns out very ironic as well as stifling when the revolution appears on the horizon and tragic and loving when Mehri starts her love story and letter writing.

- Motif : Most important motifs of the novel, Persepolis, are politics, killing, history as well as weather.

- Narrator : The novel, Perspolis , is narrated from the first-person point of view , the author Marjane Satrapi. The novel is described from her point of view as a child, hence, starts with her and ends with her life experience.

- Protagonist : Marjane is the protagonist of the novel. The novel starts with her entry into the world and moves forward as she grows young after going through various trials and tribulations.

- Setting : The setting of the novel, Persepolis , is Tehran, the capital city of Iran.

- Simile : The novel shows good use of various similes as given in the below examples, i. The revolution is like a bicycle. (12) ii. You think I look like Marx. (13) iii. Don’t you think I look like Che Guevara. (16) These are similes as the use of the words “like” or “as” show the comparison between different things like the revolution to a bicycle, the persons to different figures.

Post navigation

66 pages • 2 hours read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Before You Read

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Introduction-Chapter 4

Chapters 5-9

Chapters 10-14

Chapters 15-19

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Coming-of-Age During Revolution, Civil Unrest, and War

Satrapi draws a definitive parallel between the trajectory of her childhood and the trajectory of the Islamic Revolution, as well as the Iran-Iraq war. Her life—and her family’s history—is entwined with Iranian politics and culture. This is not solely a memoir of Satrapi’s childhood; in order to understand how she grew up, the reader must understand how the revolution, civil unrest, and war changed the world around her and affected her family. Satrapi’s story is inseparable from the story of her homeland, and the events that marked her childhood years.

For this reason, the book’s plot is not entirely linear: Satrapi’s experience of the revolution was not a perfectly linear experience. Flashing back and forth between Tehran pre- and post-revolution, as well as before she is even born to imagine her family’s experiences, Satrapi employs a semi-chronological structure. This allows for greater flexibility in storytelling, and a richer, more vibrant understanding of the forces influential to Satrapi’s upbringing.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,700+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,800+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Marjane Satrapi

Chicken with Plums

Marjane Satrapi

Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return

Marjane Satrapi, Transl. Anjali Singh

Featured Collections

Books Made into Movies

View Collection

BookTok Books

Diverse Voices (High School)

Graphic Novels & Books

Middle Eastern Literature

“Persepolis”: The Process of Self-Approval

Read the instructor’s introduction Read the writer’s comments and bio Download this essay

The Complete Persepolis is a graphic memoir by Marjane Satrapi that describes the author’s childhood experience in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and her early adulthood after she graduates high school in Austria and returns to Iran. As a result of the restrictions placed on Iranian women by the supreme spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini, many Iranians demonstrated in the streets and rebelled against the Islamic Republic (“History of Iran”). Marji, the protagonist, has a distinct childhood experience in the time of revolution, experiencing extreme psychological struggle under the influence of the political and social upheavals in Iran. Marji’s internal struggle follows her from a very young age through her adult life, which corresponds to memoirist Mary Karr ’s “inner enemy” theory explained in her book The Art of Memoir . Karr theorizes the inner enemy as “a psychic struggle against the author’s own self that works like a thread or plot engine” as well as one of the key components of a great memoir (Karr 91). Based on Karr’s theory, what is the role of Marji’s inner enemy in The Complete Persepolis ? Why does she confront such an internal struggle, and does she resolve her inner conflict by the end of book? By exploring these questions, we can better understand the central idea of Satrapi’s memoir as well as Karr’s theory and the mechanism behind a graphic memoir. It also provides readers with a distinct and profound perspective to trace the history of Iran and the impact of the revolution on the Iranian people, especially on Iranian women. Marji’s desire for freedom and her courage against authority, which are cultivated under the Westernized education she receives from her parents, make her incompatible with the society constrained by Islamic traditions and consequently lead to her inner conflict. Even though the inner conflict acts as a significant obstacle in Marji’s childhood, she successfully overcomes it and achieves self-approval before she leaves Iran for France as an independent adult, which indicates the final resolution of her inner conflict.

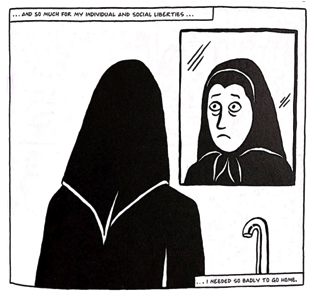

Marji’s inner enemy debuts in the first chapter and serves as a subtle but crucial thread through the whole memoir. It leads readers to Marji’s inner world, to understand her internal struggle and its reflection of Iranian society and religious repression at that time. In line with what Karr theorizes in her book, “the split self or inner conflict must manifest on the first pages and form the book’s thrust or through line” (Karr 92), Satrapi shows her own “split” in the first chapter by depicting herself in the middle of two contradictory backgrounds (see Figure 1). The panel’s emphasis on using the background rather than the caption to visualize Marji’s ambivalence reflects comic theorist Scott McCloud’s theory of communicating the invisible from his book Understanding Comics : “the background is a valuable tool for indicating invisible ideas…Particularly the world of emotions” (McCloud 132:1). In his text, McCloud highlights the potential of backgrounds to convey the character’s inner feelings, building a connection between the invisible and the visible world in comics. This panel exemplifies McCloud’s theory, as the opposition between the left side (representing the modern world) and the right side (representing the religious world) embodies the separation of Marji’s real self (the girl with the veil), and her ideal self (without the veil).

Figure 1 (Satrapi 6:1)

Furthermore, Marji is deeply influenced by her parents’ Westernized education, which prompts her to develop inner conflict. Her parents represent a segment of Iranian people at that time who accepted Western culture and held modern educational ideas. Marji’s mother had been one of the active protesters against the veil during the Islamic Revolution. Affected by her mother, young Marji is also eager to be part of the protests and fight for justice for her maid, Mehri, who is treated unfairly in her choice of marriage because of her “inferior” social class (Satrapi 37–38). Marji’s courage against authority also manifests in her direct opposition to her religion teacher in school. Marji smartly uses the experience of her Uncle Anoosh, who was a revolutionary, as an example to refute her teacher’s claim that “Iran no longer has political prisoners” because her uncle was unfortunately executed by Islamic regime at that time (Satrapi 144:1). Although Marji’s opposition to her teacher in the class was viewed as a reckless offense by the principal, Marji’s father was happy with her of telling the truth instead of blaming her under the pressure of school authority. Her father’s appropriate permissiveness preserves Marji’s passion for justice and her courage of telling the truth.

Marji’s early exposure to and obsession with Western culture further deepens her inner conflict. Marji gets in touch with Western music culture and fashion culture from a young age. She had asked her parents to bring her two posters of Western pop singers and a denim jacket from Istanbul, which were strictly forbidden in Iran during the revolution. Figure 2 shows how delighted and confident Marji is with the denim jacket. She even went outside with this jacket and got arrested by the Guardians of the Revolution (Satrapi 133). On one hand, Marji’s behavior violates the implemented dress code. On the other hand, it highlight s her desire for the freedom of dressing and her courage against authority. Scholar Rocío Davis also addresses this panel in her article “A Graphic Self: Comics as Autobiography in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis ,” which discusses in detail the juxtaposition of sequential images in Persepolis . Davis argues that “the portrait Satrapi draws of herself at the age of 14 continues to privilege her liminality, but this time in a more eclectic formulation…she literally wears the symbols of the position she has chosen for herself. At this point, Marji is no longer a child caught between two world-views: she has carved a place for herself” (273–274). I agree with Davis’s claim that Marji has “carved a place for herself” because this panel shows Marji’s attempt to adapt herself to the cultural conflict and cope with her inner struggle. Marji is satisfied with her current status instead of being perplexed by the cultural dilemma when she was ten years old, as Figure 1 shows. Nevertheless, Davis’ article only addresses the first volume of Persepoli s and, therefore, lacks a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of Marji’s inner conflict in the second volume of the graphic memoir.

Figure 2 (Satrapi 131:4)

Volume two of Persepolis describes Marji’s experience in high school in Austria, along with her later return to Iran. It is a period of time when Marji is involved in more intense inner struggle. Marji’s parents send her to study in Austria for her safety and for the Western education which they think is more suitable for their daughter. It gives Marji an opportunity to get closer to Western culture. Marji is eager to assimilate herself into the new cultural environment when she first arrives in Austria. After making friends with people from completely different cultural backgrounds and entering into several frustrating relationships, Marji dives into an unexpected path and gradually loses herself. She views her Iranian identity as “a heavy burden to bear” and even tries to disguise it by pretending to be French in front of her peers (Satrapi 195:4). Sometimes she feels guilty about intentionally alienating herself from Iranian culture and her family, but she is constantly haunted by her inner enemy. She is physically free in Austria but not spiritually free. However, Marji’s grandmother’s previously-uttered words telling Marji to “always keep your dignity and be true to yourself” somewhat release her from the stress of her internal struggle. Marji doesn’t truly accept her Iranian identity until she expresses her grievances to those who judge her for denying her own identity by exclaiming that “I am Iranian and proud of it!” (Satrapi 150:6, 197:1). As Karr suggests in her book, the motivation for a memoirist to tell a first-person narrative is usually to “go back and recover some lost aspect of the past so it can be integrated into current identity” (Karr 92). Marji’s evolving inner struggle shows her effort to reconstruct her lost Iranian memories and identity. It is the first but significant step in her process of achieving self-approval.