- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Self-Awareness Really Is (and How to Cultivate It)

- Tasha Eurich

Although most people believe that they are self-aware, true self-awareness is a rare quality. In this piece, the author describes a recent large-scale investigation that shed light on some of the biggest roadblocks, myths, and truths about what self-awareness really is — and what it takes to cultivate it. Specifically, the study found that there are actually two distinct types of self-awareness, that experience and power can hinder self-awareness, and that introspection doesn’t always make you more self-aware. Understanding these key points can help leaders learn to see themselves more clearly.

It’s not just about introspection.

Self-awareness seems to have become the latest management buzzword — and for good reason. Research suggests that when we see ourselves clearly, we are more confident and more creative . We make sounder decisions , build stronger relationships , and communicate more effectively . We’re less likely to lie, cheat, and steal . We are better workers who get more promotions . And we’re more-effective leaders with more-satisfied employees and more-profitable companies .

- TE Tasha Eurich , PhD, is an organizational psychologist, researcher, and New York Times bestselling author. She is the principal of The Eurich Group, a boutique executive development firm that helps companies — from startups to the Fortune 100 — succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders and teams. Her newest book, Insight , delves into the connection between self-awareness and success in the workplace.

Partner Center

Measuring the Effects of Self-Awareness: Construction of the Self-Awareness Outcomes Questionnaire

Affiliation.

- 1 Business School, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom.

- PMID: 27872672

- PMCID: PMC5114878

- DOI: 10.5964/ejop.v12i4.1178

Dispositional self-awareness is conceptualized in several different ways, including insight, reflection, rumination and mindfulness, with the latter in particular attracting extensive attention in recent research. While self-awareness is generally associated with positive psychological well-being, these different conceptualizations are also each associated with a range of unique outcomes. This two part, mixed methods study aimed to advance understanding of dispositional self-awareness by developing a questionnaire to measure its outcomes. In Study 1, expert focus groups categorized and extended an initial pool of potential items from previous research. In Study 2, these items were reduced to a 38 item self-report questionnaire with four factors representing three beneficial outcomes (reflective self-development, acceptance and proactivity) and one negative outcome (costs). Regression of these outcomes against self-awareness measures revealed that self-reflection and insight predicted beneficial outcomes, rumination predicted reduced benefits and increased costs, and mindfulness predicted both increased proactivity and costs. These studies help to refine the self-awareness concept by identifying the unique outcomes associated with the concepts of self-reflection, insight, reflection, rumination and mindfulness. It can be used in future studies to evaluate and develop awareness-raising techniques to maximize self-awareness benefits while minimizing related costs.

Keywords: insight; mindfulness; reflection; rumination; self-awareness; work.

Introduction: The Relational Self: Basic Forms of Self-Awareness

- Published: 20 January 2020

- Volume 39 , pages 501–507, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Anna Ciaunica 1

2 Citations

34 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Self-awareness, the feeling that our experiences are bound to the self—as a unitary entity distinct from others and the rest of the world—is a key aspect of the human mind. But how do we become aware of ourselves in a constantly changing and complex physical and social environment? How do we relate to others while keeping in touch with one’s self, with the fundamental feeling that there is an ‘I’ at the core of all our experiences and exchanges with the world and others? How is it possible to navigate such a dynamic environment without losing track of one’s self? What are the mechanisms underlying typical and atypical self-awareness and how can we spell them out within a coherent conceptual and empirical framework? What are the most basic or minimal forms of self-awareness? Is the minimal self relational or is it preferable to conceptualise it in an individualistic manner, as a fundamentally subjective sense of mineness? Is there is a ‘sense of we’, and if yes, what is its relationship with the minimal ‘individualistic’ self?

This special issue tackles these key questions by bringing together papers from philosophy, developmental and clinical psychology and theoretical neuroscience. The aim is to provide a multifaceted, interdisciplinary and rich perspective on the perennial and fundamental questions i) “what is a (minimal) self?” and ii) “how the self relates to the world and others?”

The papers in this special issue can be divided into three main groups. The first consists of four papers discussing the question whether (i) the minimal self is best understood and defined relationally, that is in terms of social interactions; or rather (ii) the minimal self is a tacit, non-socially grounded, experiential self-awareness. The second group contains three papers and combines resources from theoretical neuroscience (the Predictive Processing framework), experimental work (developmental studies), and philosophy in order to emphasise the fundamentally dynamic aspect of self-awareness. Finally, the last group consists in three papers bringing insights into these questions by focusing on atypical forms of self-awareness and social interactions, in particular schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Condition. In what follows I provide a brief synopsis each of these contributions.

1 Minimal and Relational Self: Conceptual Issues

Hutto and Ilundáin‐Agurruza ’s “Selfless activity and experience: radicalizing minimal self-awareness” begins the special issue by offering a rich discussion of the key question “how best to characterize the most fundamental ways social creatures have of engaging and sharing experiences with others?”. They contrast relational and non-relational or individualistic views of the self. For example, relationalists hold that whatever awareness of the self exactly involves it is acquired through interactions with others. By contrast, the rival non-relationalist view of selfhood, individualists for short, assume that we possess a tacit sense or awareness of the self—a kind of non-socially grounded self- awareness—that is either already implicated in the way we act successfully in the world and in the ways that we experience the world and our actions in phenomenally charged ways. Pivotally, however, if such deflationary individualist theories of the self are accepted, then pre-reflexive self-awareness is at least one primitive, defining feature of who we are that would need to be in place before we are in a position to relate to and intersubjectively engage with others. They attempt to “give the individualists their due”, explicating how we might positively understand the distinctive, nonconceptual experience of our own actions and experiences, by drawing on insights from a radically enactive take on phenomenal experience. They also defend a late-developing relationalism about the emergence of explicit, conceptually based self-awareness, proposing that the latter develops in tandem with the mastery of self-reflective narrative practices. In doing so, they challenge Ciaunica’s ( 2017 ) developmental relationism which defends the possibility that there are quite basic forms of skin-to-skin sharing with others that precede rather than presuppose the exercise of empathetic abilities. They argue that our first conceptual, explicit sense of self is something that only arrives on the scene once we become able to hold our own—through the support of others—in discursive, narrative practices that give us a conceptual grip on what it is to be a temporally extended self that persists.

Bolis and Schilbach ’s “ ‘I interact therefore I am’: the self as a historical product of dialectical attunement” proposes a shift in perspective, i.e. moving from addressing the question of self-awareness from ‘being’ to ‘becoming’. They hold the radical claim that we construe the ‘self’ as a dynamic process rather than as a static entity. To this end they draw on dialectics and Bayesian accounts of cognition which allows us to holistically consider the ‘self’ as the interplay between internalization and externalization and the latter to operationalize our suggestion formally. Internalization is considered here as the co-construction of bodily hierarchical models of the (social) world and the organism, while externalization is taken as the collective transformation of the world. They suggest that the self is an historical product of dialectical attunement across multiple time scales, from species evolution and culture to individual development and everyday learning. Specifically, they describe concrete means for empirically testing their proposal in the form of two-person psychophysiology and multi-level analyses of intersubjectivity. In short, they argue that a fine-grained analysis of social interaction might allow us to reconsider the ‘self’ beyond the static individual, i.e. how it emerges and manifests itself in social relations. They make the case that such an approach could be relevant in multiple fields, from ethics and psychiatry to pedagogy and artificial intelligence.

Higgings ’s “The ‘we’ in ‘me’: an account of minimal relational selfhood” critically discusses the idea that selfhood involves a uniquely first-personal experiential dimension, which precedes any form of socially dependent selfhood (Gallagher 2005 ; Legrand 2007 ; Strawson 2009 ; Kriegel 2009 ; Nida-Rümelin 2017 ; Zahavi 1999 , 2011 , 2014 , 2016 , 2017a , b ). In his paper he draws attention against the temptation to view minimal experiential selfhood as “ontogenetically more primitive” (Zahavi 2014 , p. 14) than socially constituted selfhood. In other words, he argues that the ‘thinnest’ construal of minimal experiential selfhood fails to properly account for characteristics that are essential to human selfhood; namely, the intimate, embodied interactions that unfold at the incipient moments of human life. He argues that taking the ontogenesis of embodied human existence seriously involves accepting the de facto equiprimordiality of minimal experientialism with a ‘minimal’ form of relational selfhood, i.e. the co-constitution of experience through engagements with others. Specifically, he focuses on the dynamical and relational structure of consciousness, as a property of human beings considered holistically (i.e. as embodied beings) who are embedded in subject- dependent contexts and are therefore irreducible to descriptions that accord with some independent ‘objective’. In doing so he draws on work by Krueger ( 2013 , 2015 ) to show that early stages of human life, inclusive of the perspective of phenomenal consciousness, involve shared experiential states, in which one’s experiences are constitutively dependent on the modulatory role of others. One’s corporeality is thereby partly given over to another’s agency. Lastly, these kinds of experiential states are shown to be present at the most incipient moments of human life, thereby affirming that any naturalistically grounded notion of pre- reflective human minimal selfhood should be construed as ontogenetically equiprimordial with socially constituted experience. Such socially constituted experience amounts to a form of minimal relational selfhood, which is not preceded by any other dimension of selfhood within the manifestation of human life.

Leon ’s “For-me-ness, for-us-ness, and the we-relationship” investigates the relationship between for-me-ness and sociality. He draws very careful conceptual distinctions in order to point out some ambiguities in claims pursued by some of the critics that have recently pressed on the relationship between the two notions. He starts with the observation that the idea of for-me-ness or mineness raises a host of far-reaching questions, some of which concern its proper characterization, pervasiveness, phenomenal reality, and its relation to the prospects of providing a naturalistic account of consciousness. Leon notices that the proposal according to which there is a very tight link between subjectivity and sociality is certainly not new in the philosophical and psychological literature. However, a novel feature of some of the recent criticisms to the received understanding of for-me-ness is that they don’t appeal to language, narratives, social roles or cultural context to support this view, but rather to bottom-up approaches from developmental psychology (Ciaunica and Fotopoulou 2017 ; Ciaunica 2016 ). The main aim of his contribution is to discuss the relationship between for-me-ness and sociality, mainly in the context of recent criticisms to the received understanding of for-me-ness that have appealed to research in developmental psychology. He articulates a question concerning this relationship that builds on the idea that, occasionally at least, there is something it is like ‘for us’ to have an experience. This idea, he argues, has been explored in recent literature on shared experiences and collective intentionality (Schmid 2014a , b ), and it gestures towards the question of the extent to which some social interactions make a difference in the phenomenal character of their participants’ experiences. In the main part of his article, Leon proposes a construal of for-us-ness that complements the received understanding of for-me-ness, by drawing on Alfred Schutz’ concept of the “we-relationship” (Schutz 1962 , 1967 ; Schutz and Luckmann 1973 ), and on the idea of second-personal awareness, i.e. awareness of a ‘you’, as distinguished from awareness of a ‘she’ or he’. He concludes that this proposal provides a suitable account of basic forms of phenomenally manifest social connectedness, in a way that is cognitively undemanding and without incurring the theoretical costs of positing a sui generis plural pre-reflective self-awareness (Schmid 2014a ).

2 The Dynamic, Situated and Scaffolded Self

Kiverstein ’s “Free energy and the self: an ecological-enactive interpretation” addresses the interesting question: how did the feeling of being alive get started? One key observation is that not all living things feel alive. Plants almost certainly don’t. Bacteria are capable of a minimal form of purposive agency (Fulda 2017 ; Di Paolo et al 2017 ). However, since they lack a brain for regulating the changing internal state of their bodies, they probably also lack feeling (Thompson 2015 ). But what about insects that continue behaving in the same way when they have suffered severe injuries? They too most likely lack feeling insofar as their behaviour seems to be unaffected by damage to their bodies. Kiverstein give us an account about how subjectivity might have emerged early in evolutionary history out of processes of action control. In other words, subjectivity might be thought of as tied to processes of purposive agency on the one hand, and sensorimotor integration on the other. He defends the “phenomenological theory of selfhood” according to which any naturalistic explanation of phenomenal consciousness in the terms of psychology and the neurosciences will need to explain how mineness can be intrinsic to phenomenal consciousness. He gives a detailed account of a such naturalistic explanation that takes selfhood to emerge out of self-organising biological processes.

Kiverstein builds upon the free energy principle, according to which any living system will aim to minimise free energy in its sensory exchanges with the environment (Friston 2007 ). He shows how such a process of free energy minimisation is accomplished through a process referred to as “active inference”. He claims that active inference is best understood in ecological and enactive terms, with focus on the coupled dynamics of the animal in its eco-niche that lead towards dynamic equilibrium (Bruineberg and Rietveld 2014 ; Bruineberg et al. 2017 ). Importantly, active inference doesn’t suffice to explain mineness, since every living system will keep its own free energy to a minimum through a process of active inference. In order to address this key question, Kiverstein asks: what would need to be added to active inference to yield mineness? He suggests that recent theoretical work by Karl Friston may give us an answer to this question (Friston 2018 ). The basic idea is that once an organism reaches the level of complexity so that it can act to minimise its own expected free energy, mineness will emerge as intrinsic to the process of life itself. The author closes his paper by showing how the resulting account of mineness supports a relational theory of the self. This is because on this ecological and enactive reading of active inference the organism and its environment are co-specifying, and co-determining. The argument of Kiverstein’s paper is that any organism capable of action control of the right complexity will also be a self. Since organisms are best understood in relation to their environment, so also are selves.

Crucianelli and Filippetti ’s “Developmental perspectives on interpersonal affective touch” draws attention to a relatively overlooked aspect of interpersonal affective touch in shaping self-awareness and body ownership from the outset, in early life. They start with the basic observation that our first sensorial experiences, which provide us with information about our own body and the surrounding environment arise in the womb (Ciaunica 2016 , 2017 ; Ciaunica & Crucianelli 2019 ). In these early sensory interactions, touch is possibly the first route by which the developing body receives inputs from the external world and gradually shapes one’s body boundaries and its capabilities for action (e.g. Atkinson and Braddick 1982 ; Bernhardt 1987 ; Bremner and Lewkowicz 2012 ). The skin is the largest of our sensory organs and wraps our entire body surface (Serino and Haggard 2010 ; Gallace and Spence 2014 ); hence, evidence suggests that touch might play a pivotal role in developing a sense of self as separate from the other (see Field 2010 for a review). Somewhat paradoxically, touch is also our most social sense since it is fundamentally involved in how we explore the environment and engage in successful interactions (Gallace 2012 ; Ebisch et al. 2014 ; Rochat 2011 ; Gallace and Spence 2014 ), as well as how we bond with other people and form interpersonal attachments. In their paper they review and discuss recent developmental and adult findings, pointing to the central role of interpersonal affective touch in body awareness and social cognition in health and disorders. They propose that interpersonal affective touch, as an interoceptive modality invested of a social nature, can uniquely contribute to the ongoing debate in philosophy about the primacy of the relational nature of the minimal self. In the wake of these recent conceptualisations, Crucianelli and Filippetti review experimental and clinical evidence supporting the importance of interpersonal affective touch to the way we recognise and make sense of our body as our own. In line with previous work by Ciaunica ( 2017 ) and Ciaunica & Fotopoulou ( 2017 ) they defend the claim that affective touch constitutes a fundamental aspect of bodily self-consciousness (Blanke 2012 ; Dijkerman 2015 ) from the very first stages of human life.

Gallotti ’s “Shared and social discourse” discusses the scope and importance of claims about shared intentionality in social discourse. What is it for the capacity of sharing mental attitudes and contents to play an explanatory role in the study of the social mind? The motivation for addressing this question is originally tied to theoretical preoccupations about the tendency to make claims about shared and, especially, ‘we- intentionality’ in support of arguments about socially extended forms of mentality. The fact that evidence is interpreted as showing that shared intentionality works as a scaffolding for the development of full- blown, representational and normative, thinking, is often associated with claims about the conditions for the existence and identity of mental attitudes and contents being social all the way down. This argumentative line is present in several strands of social-cognitive research at the intersection of studies of shared intentionality and radically (i.e. en-active) externalist views of the mind, but it has not yet been articulated in a satisfactory manner. The key question is what human cognition could be like on the premise that humans are capable of creating cultures and institutions of unique complexity in the animal kingdom. Tomasello’s response is an account of the evolution of the human mind, which identifies the origin of species-specific forms of modern thinking in the emergence of a genetically evolved psychological adaptation for engaging in cognitively shared activities with co-specifics (Tomasello and Carpenter 2007 ; Call 2009 ). In a similar vein, Jane Heal has offered an authoritative formulation of the significance of shared cognitive activities in philosophical work on co-cognition (Heal 2013 ). Building upon earlier reflections on co-cognition in simulation theory (Heal 1998 ), Heal draws on insights about shared intentionality to advocate ‘Co-cognitivism’, the view that the logical structure and criteria of adequacy of psychological concepts are determined with a view to the sort of activities that individuals pursue together in everyday life. Co-cognitivism and the ‘Shared Intentionality Hypothesis' gesture to something like a general view of the function of shared intentionality, which has only begun to emerge in the philosophy of mind and society. The idea is that human psychology has evolved in accordance with the fact that novel routes to knowledge of things become available to interacting agents when they align their mental and bodily resources and act as a ‘we’ (Tollefsen and Dale 2012 ; Gallotti et al. 2017 ). Gallotti's goal is to develop a more balanced, if not cautious, assessment of the explanatory role of claims about shared intentionality in social discourse.

3 Minimal and Relational Self and its Disruptions

Krueger ’s “Schizophrenia and the scaffolded self” takes as a starting point a family of recent externalist approaches in philosophy of mind which argue that our psychological capacities are synchronically and diachronically “scaffolded” by external (i.e., beyond-the-brain) resources. Surprisingly, he writes, despite much recent interest in this topic, it has not yet found its way to philosophy of psychiatry in a substantive way. Since disturbances of affectivity figure so prominently in a wide variety of mental disorders, the topic seems like a fruitful place to bridge externalist paradigms and psychiatry. The main aim of his paper is an attempt to build such a bridge. Krueger considers how these “scaffolded” approaches might inform debates in phenomenological psychopathology. In doing so, he first introduces the idea of “affective scaffolding” and makes some taxonomic distinctions. More specifically, he uses schizophrenia as a case study to argue—along with others in phenomenological psychopathology—that schizophrenia is fundamentally a self- disturbance. Building upon previous existing work, he offers a subtle reconfiguration of these approaches. He claims that schizophrenia is not simply a disruption of ipseity or minimal self-consciousness but rather a disruption of the scaffolded self, established and regulated via its ongoing engagement with the world and others. He concludes that this way of thinking about the scaffolded self is potentially transformative both for our theoretical as well as practical understanding of the causes and character of schizophrenic experience, insofar as it suggests the need to consider new forms of intervention and treatment.

Constant , Bervoets , Hens and Van de Cruys ’s “Precise worlds for certain minds: An ecological perspective on the relational self in autism” addresses the question of how the various aspects of the relational self are experienced by people presented with clear challenges in social interaction, such as people with Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC). Indeed, relational and social accounts of the self posit that the sense of self depends on the entanglement of the individual with a significant, or generalized other, understood respectively as the representation of an individual profound significance in one’s life (Andersen and Chen 2002 ), and as the individually internalized ‘attitude of a whole community’ (Mead 1934 ). On that view, the self would heavily rest on the individual’s ability to coordinate a diversified repertoire of selves (cf. Zahavi 2010 ) accumulated over time through interpersonal relationships (Andersen and Chen 2002 ). However, ASC offers an interesting challenge for the relational views of the self precisely because it is broadly recognized as a disorder primarily impacting social relationships. Indeed, while they do not claim that autistic people completely lack a sense of self, many influential theories tend to suggest that the requirements for a sense of relational self are reduced or otherwise impaired. Yet, the abundance of autobiographical reports (Van Goidsenhoven and Masschelein 2016 ) by autistic people across the spectrum suggests that a desire for self-identification and recognition is particularly pronounced in people with ASC. Building upon the influential predictive processing (PP) paradigm, in explaining core behavioral traits of ASC (e.g., Lawson et al. 2014 ; Palmer et al. 2015 ; Pellicano and Burr 2012 ; Van de Cruys et al. 2014 ) PP approaches challenge the claims about the presence of specific neurocognitive dysfunctions in autistic cognition, as it traces back the symptoms of ASC to normal, though differently ‘tuned’, domain general neurocognitive mechanisms (cf. Bolis and Schilbach 2017 ).

The main aim of their paper is to use the PP paradigm to attempt an ecological explanation of atypicalities of the relational self in ASC, specifically, those relating to its minimal, extended, and intersubjective aspects, though without positing major incapacities in social functioning. The main focus is in how these aspects become organized in patterns of sensory and social interactions with the body (e.g., interoception), the world (e.g., exteroception and material (environment), and other agents (e.g., social interactions). Specifically, they focus on a recent PP account of ASC called “HIPPEA”, the High, Inflexible Precision of Prediction Errors in Autism account (Van de Cruys et al. 2014 ). PP accounts of ASC emphasize different aspects of PP, even though they generally include a treatment of all basic mechanisms. The focus on HIPPEA is motivated by its interpretation of the mechanism of meta-learning. According to PP, meta-learning enables to detect learnable sensory cues, relevant for predicting future events with a certain level of reliability. It is a mechanism crucial to distinguish random sensory variability from the variability reporting causal regularities (e.g., recurrent causes of inputs). This new account enables a leverage the ecological and embodied implications of PP to discuss aspects of the relational self in ASC. The ecological implications of PP for understanding ASC are far-reaching (e.g., Bolis and Schilbach 2017 ; von der Lühe et al. 2016 ), but have so far not been exhaustively treated in the literature. This paper intends to fill this gap.

Kartner and Clowes ’s “The pre-reflective situational self” critically addresses the idea that pre-reflective self-awareness constitutes a minimal self. They argue that there are reasons to doubt this constituting role of mineness. Specifically, they claim that there are alternative possibilities and that the necessity for an adequate theory of the self within psychopathology gives us good reasons to believe that we need a thicker notion of the pre-reflective self. The authors propose instead the idea of a Pre-Reflective Situational Self. In a first step, they show how alternative conceptions of pre-reflective self-awareness point to philosophical problems with the standard phenomenological view. They claim that this is mainly due to fact that within the phenomenological account the mineness aspect is implicitly playing several roles. Consequently, they argue that a thin interpretation of pre-reflective self-awareness—based on a thin notion of mineness—cannot do its needed job within psychopathology. Rather a thicker conception of pre-reflective self is needed. In their proposal they carefully develop the notion of a pre-reflective situational self by analyzing the dynamical nature of the relation between self-awareness and the world, specifically through our interactive inhabitation of the social world. Specifically they discuss three alternative views which give reasons to question the standard phenomenological interpretation of pre-reflective self- awareness. They start by reviewing several of the most important of these, namely the cognitive view, the structure-awareness view and the relational view and show that each cast rather different light upon the interrelations between first-person givenness, mineness and the minimal self. They argue that the problematic nature of pre-reflective self-awareness this is especially revealed in the context of the Ipseity Hypothesis of Schizophrenia. Here, the thin notion of pre-reflective self does not appear to do what is required of it, namely to fulfil the necessary conceptual role in explaining what appears disrupted in this type of mental illness. This is problematic in their view, as the deployment of the notion of minimal self in “ipseity theories” of schizophrenia might be thought to be one place where the notion of pre-reflective self-awareness earns its status as a concept that has some empirical standing (Nordgaard and Parnas 2014 ; Parnas et al. 2005 ; Sass et al. 2013 ) In their paper they use this discussion to link it to related work on self-diminishment in schizophrenia, namely the self-diminishment view (Lysaker and Lysaker 2008 ) in order to argue that our sense of pre-reflective self is better understood as labile and situational through a thicker conception of self than is entertained in the more standard phenomenological views. On these grounds, they conclude that our sense of pre-reflective self in part must be dynamical in order to reflect our fluid embedding in shifting social contexts.

Andersen SM, Chen S (2002) The relational self: an interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychol Rev 109(4):619–645

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson J, Braddick O (1982) Sensory and perceptual capacities of the neonate. In: Stratton P (ed) Psychobiology of the human newborn. Wiley, London, pp 191–220

Google Scholar

Bernhardt J (1987) Sensory capabilities of the fetus. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 12(1):44–47

Blanke O (2012) Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily selfconsciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci 13(8):556

Bolis D, Schilbach L (2017) Observing and participating in social interactions: action perception and action control across the autistic spectrum. Dev Cogn Neurosci 29:168–175

Bremner AJ, Lewkowicz DJ, Spence C (2012) The multisensory approach to development. In: Bremner AJ, Lewkowicz DJ, Spence C (eds) Multisensory development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–26

Chapter Google Scholar

Bruineberg J, Rietveld E (2014) Self-organisation, free energy minimisation, and optimal grip on a field of affordances. Front Human Neurosci 8:599

Bruineberg J, Kiverstein J, Rietveld E (2017) The anticipating brain is not a scientist: the free energy principle from an ecological-enactive perspective. Synthese 195:2417–2444

Call J (2009) Contrasting the social cognition of humans and nonhuman apes: the shared intentionality hypothesis. Topics Cogn Sci 1:368–379

Ciaunica A (2016) Basic forms of pre-reflective self-consciousness: a developmental perspective. In: Miguens S, Preyer G, Bravo Morando C (eds) Pre-reflective consciousness: sartre and contemporary philosophy of mind. Routledge, London

Ciaunica A (2017) The meeting of bodies: basic forms of shared experiences. Topoi, Int J Philos. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-017-9500-x

Ciaunica A, Crucianelli L (2019) Minimal self-consciousness from within – a developmental perspective. J Conscious Stud 26(3–4):207–226

Ciaunica A, Fotopoulou A (2017) The touched self: psychological and philosophical perspectives on proximal intersubjectivity and the self. In: Durt C, Fuchs T, Tewes C (eds) Embodiment, enaction, and culture: investigating the constitution of the shared world. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Craig AD (2002) Opinion: how do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci 3(8):655

Craig AD, Craig AD (2009) How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci 10(1):59–70

Di Paolo E, Buhrmann T, Barandiaran XE (2017) Sensorimotor life: an enactive proposal. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Dijkerman HC (2015) How do different aspects of self-consciousness interact? Trends Cogn Sci 19(8):427–428

Ebisch SJ, Ferri F, Gallese V (2014) Touching moments: desire modulates the neural anticipation of active romantic caress. Front Behav Neurosci 8:60

Field T (2010) Touch for socioemotional and physical well-being: a review. Dev Rev 30(4):367–383

Friston K (2007) Free energy and the brain. Synthese 159(3):417–458

Friston K (2018) (ms) Am I self-conscious. Manuscript under review, frontiers in theoretical and philosophical psychology philosophical and ethical aspects of a science of consciousness and the self

Fulda FC (2017) Natural agency: the case of bacterial cognition. J Am Philos Assoc 3:1–22

Gallace A (2012) Living with touch. Psychologist 25(12):896–899

Gallace A, Spence C (2014) In touch with the future: the sense of touch from cognitive neuroscience to virtual reality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gallagher S (2005) How the body shapes the mind. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gallotti M, Fairhurst MT, Frith CD (2017) ‘Alignment in social interactions’. Conscious Cogn 48:253–261

Heal J (1998) Co-cognition and off-line simulation: two ways of understanding the simulation approach. Mind Lang 13:477–498

Heal J (2013) Social anti-individualism, co-cognitivism and second-person authority. Mind 122:340–371

Kriegel U (2009) Subjective consciousness: a self-representational theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Krueger J (2013) Merleau-ponty on shared emotions and the joint ownership thesis. Cont Philos Rev 46(4):509–531

Krueger J (2015) The affective 'we': self-regulation and shared emotions. In: Szanto T, Moran D (eds) The phenomenology of sociality: discovering the 'We'. Routledge, New York, pp 263–280

Lawson RP, Rees G, Friston KJ (2014) An aberrant precision account of autism. Front Hum Neurosci 8:302

Legrand D (2007) Pre-reflective self-as-subject from experiential and empirical perspectives. Conscious Cogn 16(3):583–599

Lysaker PH, Lysaker JT (2008) Schizophrenia and the fate of the self. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mead HG (1934) Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nida-Rümelin M (2017) Self-awareness. Rev Philos Psychol 8(1):55–82

Nordgaard J, Parnas J (2014) Self-disorders and the schizophrenia spectrum: a study of 100 first hospital admissions. Schizophr Bull 40(6):1300–1307

Palmer CJ, Paton B, Enticott PG, Hohwy J (2015) “Subtypes” in the presentation of autistic traits in the general adult population. J Autism Dev Disord 45(5):1291–1301

Parnas J, Møller P, Kircher T, Thalbitzer J, Jansson L, Handest P, Zahavi D (2005) EASE: examination of anomalous self-experience. Psychopathology 38(5):236–258

Pellicano E, Burr D (2012) When the world becomes “too real”: a Bayesian explanation of autistic perception. Trends Cogn Sci 16(10):504–510

Rochat P (2011) Possession and morality in early development. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2011(132):23–38

Sass LA, Pienkos E, Nelson B, Medford N (2013) Anomalous self-experience in depersonalization and schizophrenia: a comparative investigation. Conscious Cogn 22(2):430–441

Schmid HB (2014a) Plural self-awareness. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 13(1):7–24

Schmid HB (2014b) The feeling of being a group. Corporate emotions and collective consciousness. In: von Scheve C, Salmela M (eds) Collective emotions: perspectives from psychology, philosophy, and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Schutz A (1962) Collected papers I the problem of social reality. M. Nijhoff, Hague

Schutz A (1967) Phenomenology of the social world. Northwestern University Press, Evanston

Schutz A, Luckmann T (1973) The structures of the life-world (Vol. I). Northwestern University Press, Evanston

Serino A, Haggard P (2010) Touch and the body. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34(2):224–236

Strawson G (2009) Selves: an essay in revisionary metaphysics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Thompson E (2015) Waking, dreaming, being: self and consciousness in neuroscience, meditation and philosophy. Columbia University Press, New York

Tollefsen D, Dale R (2012) Naturalizing joint action: a process-based approach. Philos Psychol 25:385–407

Tomasello M, Carpenter M (2007) Shared intentionality. Dev Sci 10:121–125

Van de Cruys S, Evers K, Van der Hallen R, Van Eylen L, Boets B, de-Wit L, Wagemans J (2014) Precise minds in uncertain worlds: predictive coding in autism. Psychol Rev 121(4):649–675

Van Goidsenhoven L, Masschelein A (2016) Donna Williams’s “triumph”: looking for “the place in the middle”at jessica kingsley publishers. Life Writ 2016:1–23

von der Lühe T, Manera V, Barisic I, Becchio C, Vogeley K, Schilbach L (2016) Interpersonal predictive coding, not action perception, is impaired in autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 371:20150373

Zahavi D (1999) Self-awareness and alterity: a phenomenological investigation. Northwestern University Press, Chicago

Zahavi D (2005) Subjectivity and selfhood: investigating the first-person perspective. MIT Press, Cambridge

Zahavi D (2010) Complexities of self. Autism 14(5):547–551

Zahavi D (2011) The experiential self: objections and clarifications. In: Sidertis M, Thompson E, Zahavi D (eds) Self, no self? Perspectives from analytical, phenomenological, and indian traditions. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 5678

Zahavi D (2014) Self & other: exploring subjectivity, empathy, and shame. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Zahavi D (2016) Openness versus interdependence: a reply to Kyselo. Philos Psychol 29(7):1066–1067

Zahavi D (2017a) Thin, thinner, thinnest: defining the minimal self. In: Durt C, Fuchs T, Tewes C (eds) Embodiment, enaction, and culture: investigating the constitution of the shared world. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 193–200

Zahavi D (2017b) ‘Consciousness and (minimal) selfhood: getting clearer on for-me-ness and mineness’. In: Kriegel U (ed.) The Oxford handbook of the philosophy of consciousness. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Senior Researcher Institute of Philosophy Porto, Portugal & Research Associate Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, UCL, London, UK

Anna Ciaunica

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Ciaunica .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ciaunica, A. Introduction: The Relational Self: Basic Forms of Self-Awareness. Topoi 39 , 501–507 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-020-09689-z

Download citation

Published : 20 January 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-020-09689-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Effect of Trait Self-Awareness, Self-Reflection, and Perceptions of Choice Meaningfulness on Indicators of Social Identity within a Decision-Making Context

Noam dishon.

1 Department of Psychological Sciences, Faculty of Health, Arts and Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Julian A. Oldmeadow

Christine critchley.

2 Department of Statistics, Data Science and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Arts and Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Jordy Kaufman

Theorists operating from within a narrative identity framework have suggested that self-reflective reasoning plays a central role in the development of the self. Typically, however, narrative identity researchers have investigated this relationship using correlational rather than experimental methods. In the present study, leveraging on a classic research paradigm from within the social identity literature we developed an experiment to test the extent to which self-reflection might have a causal impact on the self-concept within a decision-making context. In a minimal group paradigm participants were prompted to reflect on their painting choices either before or after allocating points to in-group∖ out-group members. As anticipated, self-reflection augmented social identification, but only when participants felt their choices were personally meaningful. Participants who reasoned about their choices and felt they were subjectively meaningful showed stronger similarity and liking for in-group members compared to those who did not reflect on their choices or found them to be subjectively meaningless. Hence, reflecting on and finding meaning in one’s choices may be an important step in linking behavior with in-group identification and thus the self-concept in turn. The absence of any effects on in-group favoritism (a third indicator of social identification measured) as well as implications of the study’s findings for self-perception, cognitive dissonance and social identity processes are also discussed.

Introduction

Psychological scientists have approached the issue of self and identity from a range of different positions. For example, some social and cultural psychologists have investigated self and identity using a social identity theory framework whereas other personality and developmental psychologists have pursued an approach informed by narrative identity theory (see, Tajfel and Turner, 1986 ; McAdams, 2001 ; Pasupathi et al., 2007 ; Miramontez et al., 2008 ). In the present paper, we synthesize aspects of both identity projects by utilizing an experimental paradigm associated with social identity theory (i.e., the minimal group paradigm), to investigate whether self-reflective reasoning, a cognitive process theorized to be central to narrative identity development, can have a causal effect on the self and identity. We also explore if such an effect could be impacted by the level of meaningfulness one associates with their self-reflective reasoning and modulated by individual differences in trait self-awareness.

Identity from a Narrative Identity Framework

McAdams (1985 , 2001 ) model of narrative identity postulates that our sense of identity is inextricably linked with the creation of a life story. According to this model, self-narratives have two primary functions. They facilitate our sense of self-continuity across time and they help us give context and meaning to the events of our lives so that we can make sense of who we are ( McAdams and McLean, 2013 ). Self-narratives, as McAdams and McLean (2013) , state facilitate meaning making because they allow the narrator to draw “…a semantic conclusion about the self from the episodic information that the story conveys” (pp. 236). Within the narrative identity literature the process of self-reflection coupled with the extraction of self-relevant meaning is referred to as autobiographical reasoning and it is theorized to be an essential cognitive process in narrative identity development and construction ( Singer et al., 2013 ). However, as Adler et al. (2016) note, within the narrative identity literature investigators have typically employed correlational research designs thereby rendering it difficult to draw causal conclusions. Adler et al. (2016) develop this idea further stating that given this paucity of experimental work “increasing methodological sophistication and variety in the study of narrative identity with an eye toward drawing causal inferences is vital” (pp. 29).

Self-Reflection, Meaning and the Self

Although research from within the narrative identity literature demonstrating a causal link between self-reflection and identity development remains scarce, several other lines of converging research also suggest that self-reflection should play an important role in self-concept development. For example within the clinical psychology literature, reflective functioning has been used to describe a persons ability to reflect on experiences, draw inferences about behavior from these reflections, and then use those inferences to construct and develop representations of the self ( Katznelson, 2014 ). Research which has investigated reflective functioning has demonstrated that changes in reflective functioning are linked to self-concept change. For example, in research with persons affected by borderline personality disorder, (a condition which is characterized by an unstable sense of self) Levy et al. (2006) found that improvements in reflective functioning were associated with improvements in self-representations and a more integrated sense of self.

Another reason for thinking that self-reflection should represent an important mechanism in self-concept construction and development comes from research which has utilized the self-referential memory paradigm. In a typical self-referential memory paradigm study, different word categories (i.e., traits and adjectives verse semantically and orthographically related words) are presented to participants who are instructed to remember them at exposure and then asked to recall them at a later time ( Rogers et al., 1977 ). The self-reference effect describes the tendency for participants to retrieve traits and adjectives that are self-related more successfully than words that are semantically or orthographically related ( Symons and Johnson, 1997 ). Schizophrenia is another condition of which an unstable sense of self represents a core feature (see Sass and Parnas, 2003 ), and research has demonstrated that persons affected by schizophrenia tend to display weaker self-reference effects compared to healthy controls which researchers have interpreted as an indication of reduced self-reflective capacity ( Harvey et al., 2011 ).

There are also several reasons for thinking that meaning-making tendencies should play an important role in self-concept construction and development in addition to the emphasis placed upon this process by narrative identity theorists as noted previously. Firstly, in a theoretical sense, influential thinkers such as Erikson (1963) , Frankl (1969) , and Bruner (1990) , have all argued strongly for the idea that meaning is likely to play an important role in self and identity development. At the same time, research from within the organizational psychology literature has demonstrated empirically that perceptions of meaningfulness are associated with a range of self-related outcomes. Psychological empowerment captures an employees cognitive-motivational stance toward their work and is comprised of four dimensions, impact , competence , autonomy , and of particular pertinence given the current investigation, meaning which reflects the degree to which one perceives their work as being personally meaningful ( Spreitzer, 1995 ; Holdsworth and Cartwright, 2003 ). The importance of perceptions of meaningfulness within the context of psychological empowerment is further highlighted by Spreitzer et al. ( 1997 , pp. 681) who argue that the dimension of meaning “serves as the ‘engine’ of empowerment.” Research exploring psychological empowerment at an individual factor level has noted that differences in meaning are positively associated with several self-related outcomes such as self-esteem and self-efficacy ( McAllister, 2016 ).

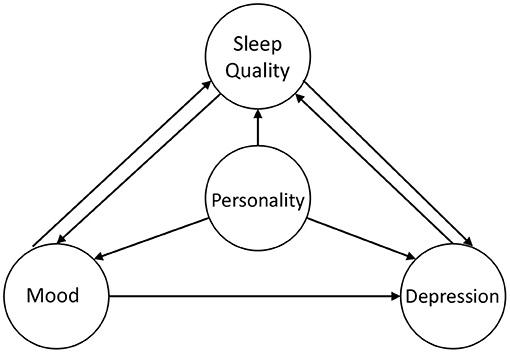

In our own research we have found that individual differences in trait self-awareness are associated with perceptions of choice meaningfulness within a decision-making context (Dishon et al., under review). Based on pre-existing literature which has explored self-awareness more generally (e.g., Morin, 2011 ) we defined trait self-awareness as individual differences in the capacity to access knowledge, insight and understanding of internal self-related experiences. We found that participants with higher levels of trait self-awareness perceived significantly more meaning in a series of minor experimentally induced choices compared to those with lower levels of trait self-awareness. Moreover, this difference remained irrespective of whether or not participants were told that their choices were diagnostic of important personal characteristics. We concluded from this research that individuals high in trait self-awareness are more likely to reflect on their choices and more likely to find them meaningful than individuals low in trait self-awareness. Extending on this work and drawing upon the literature previously presented, in the present paper we propose and explore a theoretical model (see Figure Figure1 1 ) that articulates how self-reflection and perceptions of meaningfulness might affect the self within a choice context.

Self-reflection model.

Overview of the Self-Reflection Model

The assumptions underpinning this model are that when one is presented with a potential trigger event such as (but not limited to) a choice or behavior, the self will be affected (i.e., the choice/behavior will inform the self) as a consequence of (a) whether or not self-reflection takes place, and (b) the degree to which the choice is perceived to be personally meaningful. Moreover, (c) whether or not reflection takes place may be determined by individual or situational factors. For example, individuals with higher levels of trait self-awareness may be more predisposed to engage in self-reflective reasoning, whereas for others, situational cues such as an unexpected occurrence or a prompt from a third party might act as the catalyst for self-reflective reasoning. Several predictions arise from the model.

Prediction 1: If self-reflective reasoning does occur and the choice or behavior is perceived to be highly meaningful, then self-perception will occur (by which we mean the self-concept will be modified or changed as result of the behavior or action).

Prediction 2: If self-reflective reasoning does occur and the level of personal meaning associated with the choice or behavior is perceived to be low, its affect on the self will be weak or absent.

Prediction 3: If no self-reflective reasoning occurs there will be a weak effect on the self through an automatic self-perception process. Rather than predict no effect on the self in the absence of self-reflection, we allow for the possibility of an automatic or implicit self-perception process to occur because research has demonstrated that the self-concept can be impacted even in the absence of explicit reasoning. For example, in one demonstration of this type of effect, Klimmt et al. (2010) observed that exposing participants to different types of characters in video games led to automatic shifts in self-perception as measured in a follow up Implicit Association Test.

Prediction 4: Individuals high in trait self-awareness will be more likely to engage in self-reflective reasoning than individuals low in trait self-awareness 1 .

Prediction 5: Individuals low in trait self-awareness will engage in self-reflective reasoning only if prompted, or if some other situational cue triggers self-reflection.

Although narrative identity researchers have primarily looked at self-reflective reasoning in the context of autobiographical memories (see, Pasupathi, 2015 ), in the present study we sought to initially test the veracity of our self-reflection model on a smaller scale in a relatively minimal decision-making context. We did so for several reasons. First, decision-making lends itself well to experimental testing ( Carroll and Johnson, 1990 ). This is important because as noted earlier, to date, research investigating the relationship between self-reflective reasoning and the self has largely been correlational by design and attempts to test this possibility experimentally have been insufficient ( Adler et al., 2016 ). Second, consumer decision-making research has suggested that self-narratives often arise in every day decision-making contexts ( Phillips et al., 1995 ) and some narrative identity scholars have argued that day-to-day narratives which might not be overtly autobiographical nevertheless remain tightly linked to self and identity ( Bamberg, 2011 ; Pasupathi, 2015 ). Third, behaviorist and cognitive theories (i.e., self-perception theory and cognitive dissonance theory) suggest that the self is often informed by after-the-fact explanations for behaviors or post hoc reasoning for choices ( Brehm, 1956 ; Festinger, 1957 ; Bem, 1972 ). Another reason for thinking that self-reflection could impact self-perception stems from research by Wilson et al. (1993) which demonstrated that self-reflection can impact attitudes and post-choice satisfaction within a decision-making context.

Identity from a Social Identity Framework

From the view of social identity theory, our sense of identity is heavily influenced by the social groups that we belong to ( Tajfel and Turner, 1986 ). Social identity as originally conceptualized by Tajfel (1981) refers to “…that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group” (p. 255). According to the theory, we come to identify with certain social groups based upon the extent to which we think we share similarities with other group members. Then, in order to maintain a positive sense of our social identity we try to ensure that our group (the in-group) is favored over other out-groups. One way of doing this is by favoring one’s in-group and discriminating against the out-group. Within the social identity literature, the extent to which we feel similar to, like, or favor other in-group members is indicative of the extent to which our identification with that group has been incorporated into our self-concept ( Hogg, 1992 , 1993 ; Ellemers et al., 1999 ; Leach et al., 2008 ). The minimal group paradigm which facilitates the measurement of in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination is one way of measuring the extent to which group membership has been incorporated into the self-concept and therefore had an effect on social identity ( Otten, 2016 ).

In a typical minimal group paradigm experiment, participants are randomly allocated to a group and then asked to concurrently distribute resources to in-group and out-group members on allocation matrices specifically designed to measure allocation strategies that favor the in-group and∖or discriminate against an out-group ( Tajfel et al., 1971 ). Research in the field has consistently demonstrated that even when people are led to believe that their assignment to a group is for a trivial reason, such as their preferences for abstract artwork, they still tend to allocate resources more favorably to in-group members ( Otten, 2016 ). Whilst researchers have often been interested in using this methodology to investigate topics such as prejudice and discrimination, the allocation of resources within a minimal group paradigm environment need not be used exclusively for this end ( Bourhis et al., 1994 ). The allocation of resources within a minimal group paradigm context can also serve as a subtle and discreet measure of the degree to which group membership has been incorporated into the self-concept and one’s sense of social identity more generally ( Otten, 2016 ). Another way that social identity researchers have measured the extent to which commitment to a group can impact one’s self-concept and sense of identity is by measuring self-reported liking of, and similarity with, other anonymous in-group members (e.g., Hogg, 1992 , 1993 ; Ellemers et al., 1999 ; Leach et al., 2008 ). Ellemers et al. (1999) research is also important in the context of the current study because it demonstrates that social identification is more strongly affected when people are able to self-select into a group (as opposed to being assigned a group) and it would seem reasonable to think that self-reflective reasoning is a process that could be quite important for self-selection decisions.

The Current Study

In recent research in our lab we investigated the connection between self-reflective reasoning within a decision-making context and the self. We found that the degree of personal meaning that was given to a trivial choice was associated with individual differences in trait self-awareness (Dishon et al., under review). In the present study we sought to extend this research by investigating further if the cognitive process of engaging in self-reflective reasoning could affect one’s sense of identity. We also sought to explore whether an effect of this kind might be impacted by the extent to which one felt as though their reasoning had been personally meaningful and also moderated by individual differences in trait self-awareness. To test this model we developed an experiment that utilized and extended upon traditional minimal group paradigm work. Participants were randomly assigned to either an experimental or control condition. In the experimental condition participants were prompted to engage in self-reflective reasoning immediately after making painting choices whereas in the control condition participants went on to allocate resources immediately after selecting paintings. We used in-group∖out-group allocation strategies as one dependent measure of identity and we also used similarity and liking ratings with in-group∖out-group members as additional dependent measures of identity.

Based on the proposed model we hypothesized that participants who are relatively high in trait self-awareness would be more likely to spontaneously self-reflect on their choices and therefore be relatively unaffected by the self-reflection prompt manipulation. As such it was expected that for these participants, self-perception would be related to the perceived meaningfulness of their painting choices more so than condition. We also expected that participants who are relatively low in trait self-awareness would be less likely to spontaneously self-reflect on their choices and therefore more greatly affected by the self-reflection prompt manipulation. As such it was expected that for these participants, self-perception would be related to the perceived meaningfulness of their painting choices only in the experimental condition (i.e., when they have been prompted to self-reflect.)

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Two hundred and six undergraduate psychology students voluntarily participated in the study in exchange for course credit. During the procedure, a manipulation check was administered to ensure that participants had attended to feedback regarding group allocation (the details of which are explained further in the Procedure section below). The responses of 32 participants who failed the manipulation check were discarded leaving a remaining pool of 174 participants (139 female, 35 male) with a mean age of 33.06 years ( SD = 11.78). The difference in failure rates between conditions was not significant ( p = 0.518). Ethical approval for the study was provided by Swinburne University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (SUHREC).

Effects of the experimental manipulation on identity were inferred by, (a) the extent to which participants incorporated their in-group identification into their self-concept and measured by participant’s in-group favoritism when distributing resources to in-group∖out-group members on Tajfel matrices and, (b) participant’s self-identification with in-group∖out-group members which was assessed by measuring their liking of, and perceived similarity with, in-group∖out-group members.

Tajfel matrices

Tajfel matrices consist of six matrices in which participants are asked to allocate resources concurrently to an in-group member and out-group member along a spectrum of pre-determined in-group to out-group ratios. The six matrices comprise three pairs (one of each pair is a reversed version of the original).

There are four main allocation strategies that can be measured with Tajfel matrices. Parity is an allocation strategy whereby the participant distributes an equal amount of resources to both in-group and out-group recipients. Maximum In-Group Profit is an allocation strategy that sees the greatest possible amount of resources awarded to the in-group recipient irrespective of what is awarded to the out-group recipient. Maximum Difference reflects a strategy that optimizes the differential allocation of resources between recipients in favor of the in-group recipient at the expense, however, of absolute in-group profit. Maximum Joint Profit reflects a strategy in which overall allocation of resources is maximized across both in-group and out-group.

The matrices facilitated the calculation of pull scores which reflected participants’ gravitation toward particular allocation strategies. Matrix pair A compared the pull of Maximum In-Group Profit and Maximum Difference (i.e., in-group favoritism) against Maximum Joint Profit. Matrix pair B compared the pull of Maximum Difference against Maximum In-Group Profit and Maximum Joint Profit. Matrix C compared the pull of Parity against Maximum In-Group Profit and Maximum Difference [See Bourhis et al. ( 1994 ) for a comprehensive and in-depth account of the procedure involved in Tajfel matrix preparation, administration, and calculation].

Following a similar procedure to Grieve and Hogg (1999) we then conducted a factor analysis of the pull scores using principal axis factoring with promax rotation to examine the possibility of computing an overall in-group favoritism score. This revealed a single in-group favoritism factor which explained 48.9% of the variance (all loadings ≥ 0.63). The items were then summed and averaged to produced an overall measure of in-group favoritism with higher scores representing greater in-group favoritism (Cronbach’s α = 0.74).

In-group self-identification

As other researchers have done previously (e.g., Hains et al., 1997 ; Grieve and Hogg, 1999 ), participants’ liking of, and perceived similarity with, in-group∖out-group members were recorded to measure their level of self-identification with their in-group. To do so, after being presented with pairs of de-identified paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky and receiving feedback that their choices indicated a preference for the work of Klee irrespective of their actual choices, (see the Procedure section below for a more detailed account of the process involved,) participants were asked to imagine themselves meeting two people, one who had a preference for Klee and the other who had a preference for Kandinsky. Participants then rated on a seven-point scale which of these two people they thought they were most similar to in general (Q1), in artistic preferences (Q2), in painting preferences (Q3), in academic ability (Q4), and in political opinions (Q5). Using the same scenario, participants were also asked to rate who they thought they would like more (Q6), who they thought they would get along with more (Q7), and who they would like to meet more (Q8). Responses on questions 1–5 were summed and averaged to calculate an overall similarity score with higher scores representing a greater level of similarity with an in-group member (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). Response for questions 6–8 were summed and averaged to calculate an overall liking score with higher scores representing a greater level of liking for an in-group member (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Meaningfulness

Meaningfulness associated with self-reflective reasoning was measured by providing participants with a five-item Subjective Meaningfulness Scale which included items such as “I feel as though my choices were genuine” and, “My choices were meaningless.” Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Responses were coded so that higher scores indicated greater level of meaningfulness. A factor analysis using principal axis factoring and promax rotation revealed that all five items loaded on a single factor which explained 32.6% of the variance (all loadings ≥ 0.43). Scores were then summed and averaged and an overall meaningfulness score was calculated (Cronbach’s α = 0.69; Guttman’s Lambda 2 = 0.70).

Trait Self-Awareness

Trait Self-Awareness was operationalized as function of participants’ scores on the Sense of Self Scale (SOSS; Flury and Ickes, 2007 ) which is a single factor 12-item measure designed to assess sense of self and self-understanding (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) and the Self-Reflection and Insight Scale (SRIS; Grant et al., 2002 ) which is a two factor 20-item measure of self-reflection and insight (Cronbach’s α = 0.88). In the present sample, using principal axis factoring and promax rotation, both measures retained their original factor structures with the SOSS exhibiting a single factor which accounted for 36.3% of the variance and the SRIS exhibiting two factors which accounted for a combined 53.6% of the variance (Factor 1 = 34.3%, Factor 2 = 19.3%). Both measures were scored so that higher scores indicated stronger sense of self and greater levels of self-reflection and insight and both measures were significantly correlated ( r = 0.35, p < 0.001). Scores on these scales were then summed to create an overall trait self-awareness score with higher scores representing greater levels of trait self-awareness (Cronbach’s α across the total 32-items = 0.77; principal axis factoring with promax rotation revealed three factors accounting for 50.6% of the variance [Factor 1 = 24.6%, Factor 2 = 21.8%, Factor 3 = 3.9%]).

Six pairs of images of paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky were utilized as the painting stimuli.

The experiment was administered online. Once consent to participate was provided, participants were informed they would be required to choose their preferred painting from six pairs of paintings which were then presented sequentially. All paintings were presented without the artists’ names attached to any of the works. After making their painting selections participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (a reasoning pre resource allocation, similarity and liking ratings condition or, a reasoning post resource allocation, similarity and liking ratings condition). Participants in both conditions were presented with all the same stimuli and experiences except the order of exposure was manipulated slightly between conditions as outlined below.

In the reasoning pre condition, after the initial painting selection phase, participants took part in the self-reflective reasoning phase. In the self-reflective reasoning phase participants were presented with and asked to reflect on a 15-item list of potential reasons for their painting selections and then presented with an open text box and asked to reflect further in their own words about their reasons for their painting choices. Following this participants were presented with and completed the subjective meaningfulness measure. Then although they remained unware to it at the time, irrespective of their actual choices participants were informed that their choices indicated that they preferred the works of Paul Klee 2 . Participants were then presented with instructions pertaining to the completion of the Tajfel matrices before moving on to complete them. Following this, participants were presented with the in-group∖out-group similarity and liking measure. Participants then completed the trait self-awareness measures before recording their gender (female, male, or other) and age. A manipulation check was then conducted whereby participants were asked to indicate who they had previously been informed that their painting choices indicated they preferred the works of (possible response were, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, or Don’t remember). Participants were then presented with a debriefing statement, informed the experiment was over and thanked for their participation.

In the reasoning post condition, the order of exposure was manipulated so that after making painting selections, participants were told their choices indicated a preference for Paul Klee 3 and were administered with the matrices and in-group∖out-group similarity and liking measures before the self-reflective reasoning phase. After completing the choice reasoning phase and the subjective meaningfulness measure, participants in this condition were also then presented with the same trait self-awareness 4 measures, demographic questions, manipulation check and debriefing as their counterparts in the alternate condition.

Outlier Analysis

Three multivariate outliers (1 in the control and 2 in the self-reflection condition) were detected and removed from the analysis thereby leaving a total sample of 171 (86 in the control condition and 85 in the self-reflection condition).

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for trait self-awareness, choice meaningfulness, in-group similarity, in-group liking, and in-group favoritism as a function of self-reflection condition are presented in Table Table1 1 .

Means and standard deviations for trait self-awareness, choice meaningfulness, similarity, liking, and in-group favoritism by self-reflection condition.

Effect of Experimental Manipulation on IV’s

We conducted between groups analyses to investigate if the self-reflection and control groups differed on the IV’s of choice meaningfulness and trait self-awareness as a function of the self-reflection manipulation. Independent samples t -test’s revealed that there was no significant difference in choice meaningfulness ( p = 0.365) or trait self-awareness ( p = 0.218) between conditions thereby demonstrating the IV’s were robust to the self-reflection manipulation.

Multiple-Sample Path Analysis

We ran a multiple-sample path analysis using the structural equation modeling program MPLUS (v 7.4) to investigate if the main effects of meaningfulness and trait self-awareness as well as the interaction effects (i.e., choice meaningfulness × trait self-awareness) on the DV’s differed between the experimental self-reflection and control non-self-reflection conditions. The model tested three exogenous/independent variables all predicting the three endogenous/dependent variables, in-group favoritism, similarity and liking. The exogenous variables were the main effects of trait self-awareness and choice meaningfulness, and a trait self-awareness × choice meaningfulness interaction.

Because the parameter to case ratio was under the required minimum of 1 parameter to 5 cases (1:4.75 or 36:171) as suggested by Kline (2011) , we discreetly tested each section of the model. In other words, three independent models with each of the three endogenous dependant variables were examined separately thereby ensuring that the parameter to case ratio was sufficient (i.e., 1:17.1 or 10:171). In all models the Satorra–Bentler robust estimator was used to account for multivariate non-normality, and all parameters were free across the self-reflection and control conditions. Chi-square Wald tests were utilized on a fully unconstrained model to test significant differences in the effects across conditions given the expectation that there would be differences in regression weights across groups ( Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017 ). There were no significant differences in the results of these separate models and the full model 5 . Given this, the parameters for the full model are presented in Table Table2 2 . Because the model was saturated with zero degrees of freedom fit indices are not reported.

Unstandardized regression weights and Wald Tests for the multi-sample path analysis.

Main Effects of Choice Meaningfulness and Trait Self-Awareness

The results in Table Table2 2 reveal that there was a significant main effect for choice meaningfulness in both the control and self-reflection conditions for similarity, however, Wald tests reveal that the difference in effects between conditions was not significant. This suggests that higher choice meaningfulness scores were associated with higher similarity scores in both the self-reflection and control conditions. The results in Table Table2 2 also demonstrate that there was a significant main effect of choice meaningfulness for liking in the self-reflection condition whereas the main effect of choice meaningfulness for liking in the control condition was not significant. The Wald test demonstrates that this difference in effects between conditions was significant, suggesting that higher choice meaningfulness scores were associated with higher liking scores in the self-reflection condition only. Whilst there was also a significant main effect of trait self-awareness on liking in the self-reflection condition, the Wald test demonstrates that this was not significantly different from the non-significant main effect of trait self-awareness in the control condition.

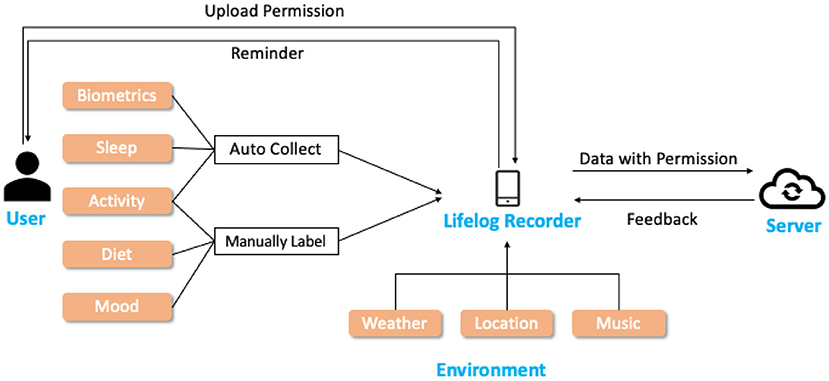

Trait Self-Awareness × Choice Meaningfulness Interaction Effects

As seen in Table Table2 2 , for liking, the interaction between trait self-awareness and choice meaningfulness was only significant in the self-reflection condition and as the significant Wald test demonstrates, the strength of this interaction effect was also significantly different between the control and self-reflection conditions (see Figure Figure2 2 ).

Predicted liking scores by trait self-awareness and choice meaningfulness groups across conditions. Groups were defined as 1 standard deviation above (high) and below (low) the mean (moderate).

The results in Figure Figure2 2 suggest that for the self-reflection group the relationship between choice meaningfulness and liking strengthens as trait self-awareness scores decrease. That is, higher choice meaningfulness scores appear to be strongly associated with higher liking scores for those with lower trait self-awareness scores. This demonstrates a stronger impact of the self-reflection manipulation on participants lower in trait self-awareness and a reduction in the impact of the manipulation as trait self-awareness levels increase. Parallel trends were observed for similarity though the Wald test was only marginally significant.

The present study explored whether engaging in self-reflective reasoning could affect in-group identification and thereby demonstrate an effect of self-reflection on indicators of social identity and the self-concept. The possibility that such an effect could be impacted by the perceived level of meaningfulness associated with reasoning, and modulated by individual differences in trait self-awareness was also explored. Based on previous research, we developed a model which predicted that participants with higher levels of trait self-awareness would be minimally affected by the self-reflection manipulation. It was therefore hypothesized that for these participants self-perception would be related to the perceived meaningfulness of their painting choices more so than condition. The model further predicted that the self-reflection manipulation would have a greater impact on participants lower in trait self-awareness. Consequently, it was further anticipated that for these participants, self-perception would be related to perceived meaningfulness of their painting choices only in the experimental condition (i.e., when they were prompted to self-reflect). Participants’ in-group similarity and liking ratings (but not in-group favoritism allocations) supported these predictions and provided general support for the theoretical model proposed earlier.