An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.11(7); 2021

Original research

Psychological factors for the onset of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective studies, zhongfang fu.

1 Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam UMC, Location AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Marlies Brouwer

Mitzy kennis.

2 ARQ National Psychotrauma Centre, ARQ centre of Expertise for the Impact of Disasters and Crises, Diemen, The Netherlands

Alishia Williams

3 Department of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Pim Cuijpers

4 Department of Clinical Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Claudi Bockting

5 Centre for Urban Mental Health, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Associated Data

bmjopen-2021-050129supp001.pdf

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

A comprehensive overview of the evidence for factors derived from leading psychological theories of the onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) that underpin psychological interventions is scarce. We aimed to systematically investigate the prospective evidence for factors derived from the behavioural, cognitive, diathesis–stress, psychodynamic and personality-based theories for the first onset of MDD.

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Databases PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane and Embase and published articles were systematically searched from inception up to August 2019. Prospective, longitudinal studies that investigated theory-derived factors before the first onset of MDD, established by a clinical interview, were included. Screening, selection and data extraction of articles were conducted by two screeners. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria were used to estimate level of confidence and risk of bias. Meta-analysis was conducted using random-effects models and mixed-method subgroup analyses.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Effect size of a factor predicting the onset of MDD (OR, risk ratio or HR).

From 42 133 original records published to August 2019, 26 studies met the inclusion criteria. Data were only available for the cognitive (n=6585) and personality-based (n=14 394) theories. Factors derived from cognitive theories and personality-based theories were related to increased odds of MDD onset (pooled OR=2.12, 95% CI: 1.12 to 4.00; pooled OR=2.43, 95% CI: 1.41 to 4.19). Publication bias and considerable heterogeneity were observed.

There is some evidence that factors derived from cognitive and personality-based theories indeed predict the onset of MDD (ie, dysfunctional attitudes and negative emotionality). There were no studies that prospectively studied factors derived from psychodynamic theories and not enough studies to examine the robust evidence for behavioural and diathesis–stress theories. Overall, the prospective evidence for psychological factors of MDD is limited, and more research on the leading psychological theories is needed.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017073975.

Strengths and limitations of this study

- This meta-analysis investigated the prospective evidence for factors derived from five psychological theories of major depressive disorder (MDD): behavioural, cognitive, psychodynamic, personality-based and diathesis–stress.

- Prospective, longitudinal studies that investigated theory-derived factors before the first onset of MDD, as established by a clinical interview, were included.

- This meta-analysis was an extensive broad review that included prospective, longitudinal studies that assessed the psychological factors before the first onset of MDD, and where MDD was established through clinical interviews.

- The limited number of eligible prospective studies with theory-derived factors on onset of MDD prevented us from drawing strong inferences on the evidence for the leading psychological theories.

- The influence of concurrent levels of baseline depressive symptoms on the prediction of MDD could not be ruled out, there was a potential publication bias and various ways to operationalise the theories across studies may have contributed to considerable heterogeneity.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent and highly disabling mental health disorder that has been identified as one of the leading causes of disease burden. 1 There are several preventative interventions and treatment options available for MDD (antidepressants and psychological interventions). 2 3 However, their effectiveness raises concerns, with high relapse rates and approximately 50% of patients showing a clinical meaningful reduction in symptoms, or attaining full remission. 4 Moreover, there is no indication that the effectiveness of current treatments for MDD improved over the past years. 4 A recent meta-analysis found a significant decline since 1960 of the effectiveness of psychological interventions compared with control groups (including active control, waitlist control, usual care, or placebo or antidepressants) for MDD for youth. 5 In addition, reported treatment effects may be overestimated due to publication bias and other biases (eg, bias due to treatment allocation, selective reporting of outcomes). 3 6 The identification of factors that precede and increase the risk of the first onset of MDD might provide points to target with (preventive) interventions. Psychological factors believed to account for the onset of MDD generally originate from psychological models and theories. 7 Up to now, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence for the leading psychological theories of the first onset of MDD is scarce.

Most current psychological interventions for prevention and treatment of MDD, for example, cognitive therapy (CT), 8 9 behaviour activation (BA), 10 psychoanalytic therapy 11 and interpersonal therapy (IPT), 12 are derived from five psychological theories, which guided our systematic search (see online supplemental appendix A ): behavioural, cognitive, psychodynamic, personality-based and most theories include an overarching diathesis–stress perspective. 13 The core principles of the five theories are briefly summarised below in reference to the corresponding psychological intervention.

Supplementary data

Each theory postulates a hypothesis on specific factors that contribute to the aetiology of MDD. For example, cognitive theories emphasise the dominant role of cognitions in the development of MDD, and the way individuals view themselves, others and the world. 8 9 Negative cognitive processing across these domains is proposed to lead to an increased risk of MDD. The factors for the onset of MDD include higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes and beliefs, negative attributional style, rumination and learnt helplessness. 9 14–20 CT (often combined with behavioural interventions) is an example of a cognitive theory-based intervention.

Originating from a framework of the learning theory, 21 behavioural theories, that underlie treatments like BA, emphasise the role of the environment and the interaction between individuals and their environment in the development of MDD (eg, references 22–28 ). It posited that decline of positive feedback prompts withdrawal behaviour (ie, low rate of response-contingent positive reinforcement) which further leads to depression. 27 29 Examples of behavioural theory-derived factors are classical and operant conditioning, social skills or behaviours that lack potential reward-value such as withdrawal and inactivity. 29

The psychodynamic theories were among the earliest to explain mental disorders including MDD, and have been used by clinicians and researchers to develop successive, overlapping models. 30–38 Vulnerability factors derived from these theories include the mother–child relationship, object relations, quality of attachment with caregivers 35–38 and significant childhood experiences. 30–35 Interventions derived from the psychodynamic theories (eg, psychoanalytic, psychodynamic and specific forms of IPT) often include a focus on attachment and interpersonal relationships. 11

Another longstanding perspective, personality-based theories of MDD, has become an umbrella of multiple personality-based factors that may be related to the onset of MDD. The theories cover various taxonomies (traits/temperament) 39 and hierarchy (‘Big Five’, 40 ‘Big Three’). 41 Among these, two major domains can be distilled: positive emotionality (PE) and negative emotionality (NE), with the assumption that depression-prone individuals experience heightened NE (eg, neuroticism) and reduced PE (eg, extraversion). 42 Even though these four theories of MDD differ in the proposed vulnerability factors, the majority of these theories underscore the importance of stress in the development of MDD. Diathesis–stress theories underlying these theories propose that vulnerability factors (ie, the theory-derived vulnerability factors, ‘diatheses’) are activated by stress, or a combination of the vulnerability factor and stress, which leads to the development of MDD. 43

Over the past decades, numerous studies and reviews have been conducted to delineate putative factors leading to the onset of MDD (eg, references 42 44–51 ) indicating that cognitive processes such as rumination and a dysfunctional thinking style 48 and personality traits (eg, neuroticism) 42 52 increase the risk to develop MDD. Nevertheless, these reviews have not culminated in definitive evidence that supports etiological theories for onset of MDD. Support for the theories is largely based on cross-sectional studies and/or studies that assessed MDD using self-reports instead of clinical interviews, or where relapse and onset were combined (eg, references 48 49 53 ). Clinical interviews are needed to reliably establish whether there is indeed a first onset of MDD, as opposed to (subthreshold and/or self-reported) depressive symptomatology alone since self-report measures are not sufficient. To overcome these limitations, a systematic review of prospective, longitudinal, studies is needed among individuals without a history of MDD, where theory-derived factors are measured before the onset of MDD. This systematic review and meta-analysis investigate and summarise the evidence for factors derived from five leading theories of MDD that underpin most used treatment options.

The methodology adopted in this meta-analysis and review was in line with the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, online supplemental appendix B ).

Search strategies

The current study was embedded in a larger project (‘My optimism wears heavy boots’, Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study) 54 investigating the psychological and biological factors of MDD onset and relapse. 55 56 Therefore, some searches were combined over topics (see online supplemental appendix A ). PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane and Embase were searched for relevant articles published from inception up to August 2019. The search combined keywords and text words relate to: first onset and studies with a prospective longitudinal design; MDD and five leading theories. Selection of the search terms indicative of the five psychological theories were guided by prior reviews, books and an extensive international expert panel (see acknowledgements for the expert panel). Snowballing was conducted by checking inclusions of previous published reviews and articles citing included studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if the following criteria were fulfilled: (1) diagnostic status of MDD was indicated for all participants and was established through a clinical interview at follow-up (ie, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) from DSM, CIDI from International Classification of Diseases (ICD)); (2) at baseline, participants did not meet criteria for MDD (and did not have depressive symptoms above cut-off scores for MDD), and did not have prior history of MDD; (3) participants with first-onset MDD had no comorbidity with other types of depressive disorder, other mental disorders or physical disease; (4) the study design was prospective/longitudinal; (5) the target variable(s) (theory-derived factors) were assessed before the first onset of MDD; participants needed to be assessed at least twice (baseline and follow-up) and (6) the study was original research, published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language. Studies with patients older than 65 years old were excluded because of the heterogeneity introduced by geriatric depression. When multiple publications with data from the same study cohort were available, we included the publication with longest period of follow-up length. When the follow-up period was equal, studies with largest number of total participants were included.

Selection process

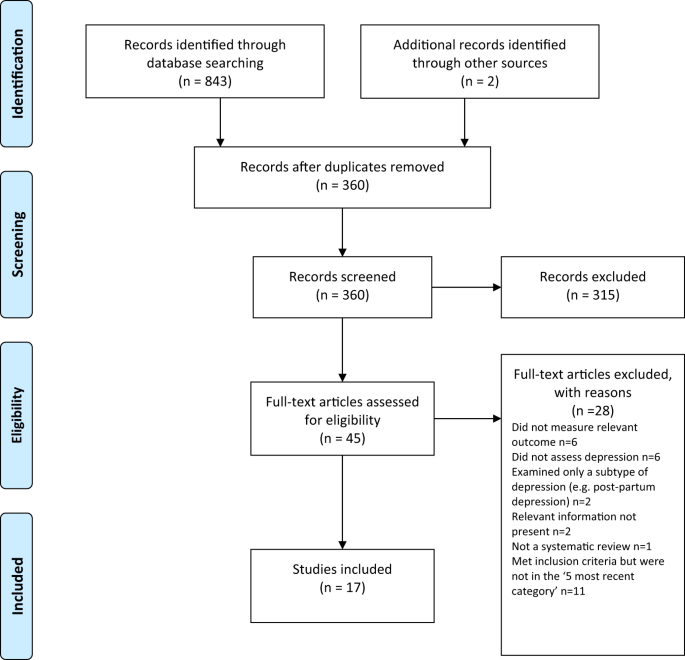

The PRISMA flow diagram for all theories is depicted in figure 1 . All records were screened by two screeners in an independent, but not fully blind way; the second screeners could see the decisions from the first screener. All eligible records that met the inclusion criteria during initial screening of the titles and abstracts were further assessed for eligibility by two screeners based on full texts. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consulting a senior author. Multiple screeners were included and assigned pairwise during this process, see author contributions and acknowledgements for the full list.

PRISMA flow diagram for the systematic review. *Studies can be included in both theories at same time. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; MDD, major depressive disorder

Quality assessment and data extraction

Two researchers assessed the risk of bias and level of confidence for the overall evidence for the psychological theories, using the criteria of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation. 57 Risk of bias was indicated in ‘+’ (low risk of bias=0), ‘?’ (unclear risk of bias=1) and ‘−’ (high risk of bias=2). Score 0–6, 6–12 and 12–18, indicated low, moderate and high risk of bias, respectively. We extracted demographic information, baseline depressive symptoms and its measurement scales, method of MDD diagnosis, psychological factors and statistical information to calculate the effect sizes. Authors were contacted when a study met the inclusion criteria, but reported insufficient data to calculate effect sizes. These authors were inquired via emails (a reminder was sent 2 weeks after if no response) on the possibility to provide the relevant statistics within 2 months. Studies were excluded in the meta-analysis if the necessary data were not provided within this timeframe.

Primary outcome

Primary outcome was the onset of MDD at study follow-up, as established by a clinical interview (eg, ICD, SCID) or expert opinion (eg, trained psychiatrist or clinical psychologist).

Statistical analysis

The programme Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA V.3.3) 58 was used to enter data of each study and each identified factor, and to calculate pooled effect sizes, forest plots, funnel plots and heterogeneity. The effect size of each factor reported in the article had to be expressed as an OR, risk ratio (RR) or HR, with 95% CIs, to indicate the relationship between the factor and time to, or odds or risk of having an onset of MDD at study follow-up. Alternatively, we calculated the OR, RR or HR by using reported statistics from each study and each factor. For example, the article needed to report means, SD, number of participants or beta coefficient with SE. These data were entered and OR, RR or HR with 95% CIs were then calculated using CMA. 58 If more than one measure from the same main psychological theory was reported in the same study, a combined effect size was calculated in CMA. 58 If a study reported multiple factors derived from different theories, the effect sizes of these factors were allocated to the corresponding theory or theories.

We then calculated pooled effect sizes (HR, RR and OR) and its 95% CI of each main theory separately using all (combined) factors assigned to that main theory. For example, the pooled effect size was calculated for all factors combined related to the cognitive theory (eg, dysfunctional attitudes, rumination, automatic thoughts). Since we expected considerable heterogeneity among studies and measures, a random effects model was employed to calculate pooled effect sizes. Second, separate subgroup analyses were conducted for each factor alone, if there were enough studies reporting that factor. To conduct these subgroup analyses, pooled effect sizes of each (theory-derived) factor were calculated using a mixed-effects model, with a random effects model to summarise the studies within each subgroup and a fixed effects model to test for differences between subgroups.

The I 2 was calculated to assess heterogeneity between studies for each analysis. In general, heterogeneity is categorised at 0%–40% (low), 30%–60% (moderate), 50%–90% (substantial) and 75%–100% (considerable). 59 The 95% CIs around I 2 were calculated using the non-central χ2-based approach within the Heterogi module for Stata. 60 Funnel plots were visually inspected for publication bias, and investigated with Egger’s test and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure. Trim-and-fill procedure was used to adjust potential publication bias. In this procedure, the asymmetric outlying studies in the funnel plot were first trimmed off and the true centre of the funnel was estimated with the symmetric remainders. Then, the funnel plot was filled with replacement of the trimmed studies and their missing counterparts around the centre. A newly pooled overall effect size based on this filled funnel plot indicated the OR after statistically adjusting the publication bias.

A priori, we aimed to conduct a meta-regression if the number of studies was sufficient, including investigating several potential continuous moderators of interest such as age, percentage female and baseline depressive symptoms were investigated. These variables were considered clinically relevant to major depression. 61–63 Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine if potential outliers, research designs and low-quality studies, affected the pooled effect sizes. The minimum number of studies was set at three studies for the main and subgroup analyses, and 10 for meta-regression.

Patient and Public Involvement

No patient involved.

Out of 69 667 identified records (see figure 1 ), 42 133 records were inspected on title/abstract after removal of duplicates, of which 52 articles met initial inclusion criteria across the psychological theories. For 26 of these articles (see online supplemental appendix C ), participants with prior MDD episodes were included and therefore those articles were excluded. In total, 26 articles were included in the final review. There were no eligible articles detected for the psychodynamic theories. A quantitative meta-analysis was only possible for the cognitive and personality-based theories. See table 1 for the characteristics of the included studies.

Selected characteristics of included studies

| Source (author, year) | Vulnerability measure | Mean age/range | SD of age | Sex (% female) | Length of follow-up (months) | Diagnostic tool | Baseline depression severity | Risk of bias | Country | |||||||||

| Cognitive theories | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||||||||

| Alloy 2006 * † | CSQ, DAS | 347 | 18.89 | Nr | 67.1 | 30 | K-SADS | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | USA |

| Goodyer , 2000 ‡ | RSQ | 172 | 13.75 | Nr | 60.4 | 12 | K-SADS | Low | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | – | UK |

| Giollabhui , 2018 *† | HSC, ACSQ-M | 173 | 12–13 | Nr | 56 | 18 | K-SADS-E | Low | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | USA |

| Kruijt , 2013 *§† | LEIDS | 834 | 41.5 | 11.5 | 63.8 | 24 | CIDI | Low | – | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | ? | NL |

| Mathew , 2011 | DAS | 1222 | 16.6 | 1.2 | 49.2 | 144 | K-SAD/ SCID; | Nr | + | + | + | – | + | ? | + | ? | – | USA |

| Nusslock 2011 † | CSQ, DAS, RSQ | 40 | 20.32 | 1.25 | 42.5 | 36 | SADS-C; SADS-L | Low | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | – | USA |

| Ormel 2004 *¶ † | UCS | 3998 | 40 | 11.4 | 49.7 | 36 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | – | + | ? | ? | ? | – | NL |

| Otto 2007 * † | DAS | 500 | 40.9 | 2.5 | 100 | 36 | SCID | Low | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | – | USA |

| Stange , 2016 | CRSQ | 341 | 12.41 | 0.63 | 53.2 | 34.13 | K-SADS | Low | + | + | + | + | + | ? | – | ? | ? | USA |

| Stone , 2011 *† | CRSQ | 95 | 11–15 | Nr | 62 | 24 | K-SADS | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | – | USA |

| Wilkinson , 2013 ‡† | RDQ | 598 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 43 | 12 | K-SADS-L | Low | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | UK |

| Personality-based theories | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eldesouky , 2018 *† | NEO-PI-R, MAPP, SIDP-IV | 758 | 59.60 | 2.7 | 55 | 60 | C-DIS-IV | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | USA |

| Bijl , 2002 ¶ | GNQ | 4455 | 18–64 | Nr | 50.3 | 12 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | NL |

| Fanous , 2007 **, † | EPQ | 1862 | 36.8 | 9.1 | 0 | 12 | SCID | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | – | USA |

| Goldstein , 2017 *† | BFI | 463 | 14.4 | 0.63 | 100 | 18 | K-SADS-PL | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | USA |

| Kendler , 1993 ** | EPQ-FormB | 1477 | 30.1 | 7.6 | 100 | 12 | DSM-III | Nr | + | + | + | ? | + | + | ? | ? | – | USA |

| Kendler , 2006 | EPQ-FormB | 20 081 | 29.2 | 8.9 | Nr | 17.4 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | – | SE |

| Kessler , 2008*, † | GPS, ABI | 4470 | 18–54 | Nr | Nr | 120 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | USA |

| Kopala-Sibley , 2017 † | BFI | 504 | 14.4 | 0.6 | 100 | 12 | K-SADS-PL | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | – | USA |

| Kruijt , 2013 §† | NEO-FFI | 834 | 41.5 | 11.5 | 63.8 | 24 | CIDI | Low | – | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | ? | NL |

| Mathew , 2011 | MMPI | 1222 | 16.6 | 1.2 | 49.2 | 144 | K-SADS /SCID | Nr | + | + | + | – | + | ? | + | ? | – | USA |

| Noteboom , 2016 §† | NEO-FFI | 648 | 41.4 | 14.7 | 61.1 | 24 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | NL |

| Nusslock , 2011 *† | BAS/BIS | 40 | 20.32 | 1.25 | 42.5 | 36 | SADS-C; SADS-L | Low | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | – | USA |

| Ormel , 2004 *¶† | ABI | 3998 | 40 | 11.4 | 49.7 | 36 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | – | + | ? | ? | ? | – | NL |

| Roberts and Kendler, 1999 ** | EPQ | 1128 | 30.1 | 7.6 | 100 | 17 | SCID | Nr | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | ? | – | USA |

| Tokuyama , 2003 *† | FFI | 1365 | 34.2 | 10.3 | 52.6 | 12 | DSM-IV | Nr | + | ? | + | – | – | ? | + | ? | – | JP |

| Behavioural theories | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stavrakakis , 2013 | Physical activity | 2149 | 13.02 | 0.61 | 52.9 | 30 | CIDI | Nr | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | + | NL |

| Østergaard , 2012 | Time of sitting | 11 862 | 43 | Nr | 60.6 | 144 | ICD | Nr | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | – | DK |

| Diathesis–stress theories | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coventry , 2009 | KPSS x SLE | 6755 | Nr | Nr | 62.7 | 12 | SSAGA | Nr | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | AU |

| Carter and Garber, 2011 | CASQ x LEDS-A | 207 | 11.86 | 0.57 | 54.2 | 72 | K-SADS-PL | Low | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | USA |

Risk of bias: 1, selection of participants; 2, diagnosis of MDD; 3, without prior history of depression; 4, covariates controlled; 5, assessment of vulnerabilities; 6, quality of assessment; 7, adequate follow-up; 8, similar treatment between onset and non-onset group; 9, other sources of bias; ‘+’, low risk of bias; ‘-’, high risk of bias; ‘?’, unclear risk of bias.

*Data derived from the Cognitive Vulnerability of Depression project

†Studies included in the meta-analysis

‡Cambridge secondary students

§Data derived from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety project; both studies were included in the meta-analysis since they measured different personality factors

¶Data derived from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS); data with the longest follow-up were retained in the meta-analysis

**Data derived from the Virginia Twin Study; data with longest follow-up were retained in the meta-analysis

ABI, Amsterdam Biographic Inventory; ACSQ, Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire; ACSQ-M, Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire-Modified; ALEQ, Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire; ASI, Attachment Style Interview; BFI, Big Five Inventory; CAS, Child Assessment Scale (for structured interview); CASQ, Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CRSQ, Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; CSQ, Cognitive Style Questionnaire; DAS, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; DIA-X/M-CIDI, Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-III; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; FPI, Freiburg Personality Inventory; GNQ, Groningse Neuroticisme Questionnaire; HSC, Hopelessness Scale for Children; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IPPA, Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; KASQ-C, Kastan Attributional Style Questionnaire for Children; KPSS, Kessler Perceived Social Support; K-SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; K-SADS-L, Kiddie Schedule for the Affective Disorders Lifetime version; KSADS-PL, Kiddie Schedule for the Affective Disorders Past and Lifetime version; LEDS, Life Events and Difficulties (LEDS) interview; LEDS-A, Life Events and Difficulties (LEDS) interview for adolescents; LEDS-r, Leiden Index of Depression Sensitivity-revised; MAPP, Multisource Assessment of Personality Pathology; MLES, Major Life Events Scale; MMPI, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory; MPQ, Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire; NEO-FFI, Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five Factor Inventory; NEO-FFI, Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five Factor Inventory; NEO-PI-R, Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Personality Inventory-Revised; Nr, not reported; NRI, Network of Relationships Inventory; PSE, Present State Examination; RDQ, Responses to Depression Questionnaire; RRS, Ruminative Response Scale; RSQ, Response Style Questionnaire; SADS-C, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Change version; SADS-L, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Epidemiological version–Present and Lifetime; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCID-NP, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM: Non-patient Lifetime; SIDP-IV, Semi-Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality; SLE, Stressful Life Events; SPIKE, Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of the Social Consequences of Psychological Disturbances for Epidemiology; SSAGA, Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism; UCS, Utrecht Coping Scale.

Behavioural theories

Two studies were eligible for the behavioural theories 64 65 and could not be meta-analysed. Both studies investigated the association between physical activities and onset of MDD, involving 14 011 adolescents and adults. Low levels of physical activities were not associated with an increased risk of developing MDD.

Cognitive theories

Eleven studies were included (8320 participants), of which eight studies were eligible for the quantitative synthesis (6585 participants; M age range=13–41; see figure 1 ). Follow-up time ranged from 1 to 12 years. The result of the overall analysis is shown in figure 2 . The pooled OR for the cognitive theory was 2.12 (95% CI: 1.12 to 4.00), which indicates that the combination of cognitive theory-derived factors predicted the first onset of MDD. Heterogeneity was considerable (I 2 =97%, 95% CI: 95% to 98%). Inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (p=0.12) did not indicate asymmetry; while Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure (three studies trimmed) suggest potential publication bias. After statistically adjusting for publication bias, the overall OR decreased to 1.11 with 95% CI as 0.60 to 2.06. The level of confidence was moderate. Given the low number of studies (<10), no meta-regression analysis or subgroup analyses were conducted. Therefore, we were unable to examine potential moderators. The results remained comparable after removing one study with a moderate risk of bias 66 ( OR =1.90, 95% CI: 1.02 to 3.55), however, were non-significant after conducting sensitivity analyses where one study with a different research design was removed (behaviour risk design; 67 OR =1.88, 95% CI: 0.97 to 3.94). Two studies reported predictive value with one study controlling for baseline depressive symptom exclusively, and the other study controlling for other covariates concurrently. 66 68 We could therefore not investigate the impact of depressive symptoms on the meta-analysis.

Forest plot of cognitive and personality-based theories to predict first onset of MDD. MDD, major depressive disorder.

Personality-based theories

Negative emotionality.

In total, 15 studies that investigated NE could be included in the qualitative synthesis (43 305 participants), of which nine studies were included in the quantitative analysis (14 394 participants, M age range=14–64). Follow-up length varied from 1 to 12 years. Eight of these nine studies investigated the role of neuroticism as a vulnerability factor; other factors were borderline personality and behaviour inhibition system. The pooled OR for the NE was 2.43 (95% CI: 1.41 to 4.19), indicating that NE was related to the first onset of MDD. See figure 2 for the overall results. Heterogeneity between studies was considerable (I 2 =96%; 95% CI: 94% to 97%), with a wide CI. The confidence of evidence was of high certainty. Inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (p=0.52) did not indicate asymmetry, while trim and fill procedure indicated risk for publication bias with four trimmed studies resulted in an adjusted OR as 1.39 (95% CI: 0.74 to 2.59). Sensitivity analysis revealed similar decline after removal of two studies 69 70 with moderate risk of bias ( OR =1.86; 95% CI: 1.25 to 2.78). The limited number of studies prohibited subgroup analyses and metaregression to investigate the effects of baseline depressive symptoms on the results.

Positive emotionality

Six studies (8848 participants) focused on PE. The pooled OR was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.84 to 1.03), which indicates that positive personality traits did not decrease the odds of MDD onset. After removing one study with a high risk of bias, the effect remained non-significant ( OR =0.94; 95% CI: 0.85 to 1.05). Heterogeneity between studies was low (I 2 =37%; 95% CI: 0% to 75%). A publication bias was not indicated (Egger’s test p=0.63; number of trimmed studies=0).

Diathesis–stress theories

Two studies were identified that prospectively examined the interaction between theory-derived factors with stress on first onset of MDD, that is, diathesis–stress theories. 71 72 Therefore, quantitative analyses were prohibited. The studies indicated non-significant results of social support 69 and negative attributional style 68 separately in interaction with stress, as predictors of MDD. No other studies included in the other theories combined the factors with measures of stress.

The aim was to systematically examine the evidence for psychological factors derived from five leading psychological theories that explain onset of MDD: behavioural, cognitive, personality-based, psychodynamic theories, including the diathesis–stress theory. Out of 42 133 identified records, 26 studies examined theory-derived factors prospectively in participants without a history of MDD, of which 14 studies could be meta-analysed for the cognitive and personality-based theories. We identified no prospective studies on psychological factors such as attachment, object relations and identification, as mentioned in psychodynamic theories, and there were not enough studies for quantitative analyses of factors derived from the behavioural theory or diathesis–stress theory. Consistent with previous reviews, 42 48 individuals with higher levels of dysfunctional attitudes, rumination, and greater cognitive reactivity, as well as higher levels of the personality trait ‘NE’, had an increased odd to develop MDD. Therefore, there was some prospective evidence for the cognitive and personality-based theories of MDD.

This extensive systematic search enabled us to investigate prospectively assessed factors derived from five theories in clinically established MDD, while the lack of evidence overall remains noteworthy. Despite the strengths of this meta-analysis, that is, the inclusion of prospective, longitudinal studies that assessed the psychological factors before the first onset of MDD, and where MDD was established through clinical interviews, some limitations should be noted. The influence of concurrent levels of baseline depressive symptoms on the prediction of MDD cannot be ruled out due to the low number of studies reporting baseline symptomatology (4/14). The marked heterogeneity that was observed may be attributed to low levels of consensus on operationalization of the theories, after consultation of lead experts in clinical psychology and psychiatry (see acknowledgements for details) to determine which factors belonged to which theories. Together with the potential publication bias, this can diminish the reliance of our result.

Despite these limitations, the present review takes an important first step to demonstrate the overall empirical status of five leading psychological theories that underpin widely used psychological interventions for MDD. The prospective evidence for the cognitive and personality-based theories in relation to onset of MDD could assist researchers and clinicians to identify potential treatment targets and/or defined high-risk groups. As mentioned, cognitive theories 9 and personality theories 42 as well as psychodynamic theories have an overlap with the diathesis–stress theory, yet there were not enough studies prospectively measuring stress or life events to investigate diathesis–stress theories. This precluded further examination of the influence of theory-derived factors under certain stressful situation. Overall, the limited number of eligible prospective studies on onset of MDD prevented us from drawing strong inferences.

The results highlight the lack of evidence of the factors derived from each theory in the onset of MDD. A research agenda should be formulated to systematically address these identified issues, including improved operationalization of leading theories, improved assessment of their factors and the use of prospective designs. All to ensure that interventions for depression are grounded in a solid foundation of clinical research. A framework that incorporates psychological, biological, environmental and social risk factors would provide a more integrative, holistic approach to unravel the underlying mechanisms of MDD.

There is some evidence that factors derived from cognitive and personality-based theories indeed predict the onset of MDD (ie, dysfunctional attitudes, cognitive styles, cognitive reactivity and NE). However, there were no studies that prospectively studied factors derived from psychodynamic theories and not enough studies to be able to examine the robust evidence for behavioural and diathesis–stress theories. More prospective and unified research is required to enable future systematic reviews. Overall, the prospective evidence for theory-derived psychological factors of MDD is limited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank Dr H Burger for his advice and guidance, and the following student researchers for their assistance: F Moysidis, C Robertson, M Wauben, S Framson, M van Dalen, M Rennert, I Baltrusaityte, L Sun, C Song, Q Yu, WJ Li and B Yücel. Also, we would like to acknowledge the professional help from NIAS theme group (My optimism wears heavy boots: So much research, so few implications, towards ‘patient–proof’ empirical models and more effective interventions in mental health) from 1 February to 30 June in 2017. In specific, we would like to thank Dr A Cramer, Professor S Hollon, Professor J Ormel, Dr G Siegle, Professor P Spinhoven, Professor E Holmes, Professor C Harmer, Dr C Vinkers and Professor M van den Hout and the expert advisors Professor D Barlow, Dr H Boettcher, Dr S Dimidjian, Dr C Martell, Professor D Ekers and Dr L Gerritsen for their input and assistance in the project.

Contributors: CB initiated the project. CB, MB and MK set up the project, protocols and literature searches. ZF, MB, MK, AW and CB did the literature searches, extracted the data and selected the articles. ZF, AW and MB entered the data. ZF, MB, PC and CB conducted the data analyses. ZF, CB, AW, MK, PC and MB wrote and revised the manuscript. CB and MB are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was partially supported by Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS), Grant awarded to Professor C Bockting (“My Optimism Wears Heavy Boots: So much research, so few implications, towards ‘patient-proof’ empirical models and more effective interventions in mental health”) Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW).

Disclaimer: The funding source had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Ethics statements, patient consent for publication.

Not required.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2022

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

- Joanna Moncrieff 1 , 2 ,

- Ruth E. Cooper 3 ,

- Tom Stockmann 4 ,

- Simone Amendola 5 ,

- Michael P. Hengartner 6 &

- Mark A. Horowitz 1 , 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 28 , pages 3243–3256 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1.34m Accesses

343 Citations

9453 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Diagnostic markers

A Correspondence to this article was published on 16 June 2023

A Comment to this article was published on 16 June 2023

The serotonin hypothesis of depression is still influential. We aimed to synthesise and evaluate evidence on whether depression is associated with lowered serotonin concentration or activity in a systematic umbrella review of the principal relevant areas of research. PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO were searched using terms appropriate to each area of research, from their inception until December 2020. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and large data-set analyses in the following areas were identified: serotonin and serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, concentrations in body fluids; serotonin 5-HT 1A receptor binding; serotonin transporter (SERT) levels measured by imaging or at post-mortem; tryptophan depletion studies; SERT gene associations and SERT gene-environment interactions. Studies of depression associated with physical conditions and specific subtypes of depression (e.g. bipolar depression) were excluded. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed the quality of included studies using the AMSTAR-2, an adapted AMSTAR-2, or the STREGA for a large genetic study. The certainty of study results was assessed using a modified version of the GRADE. We did not synthesise results of individual meta-analyses because they included overlapping studies. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020207203). 17 studies were included: 12 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 1 collaborative meta-analysis, 1 meta-analysis of large cohort studies, 1 systematic review and narrative synthesis, 1 genetic association study and 1 umbrella review. Quality of reviews was variable with some genetic studies of high quality. Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, showed no association with depression (largest n = 1002). One meta-analysis of cohort studies of plasma serotonin showed no relationship with depression, and evidence that lowered serotonin concentration was associated with antidepressant use ( n = 1869). Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the 5-HT 1A receptor (largest n = 561), and three meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining SERT binding (largest n = 1845) showed weak and inconsistent evidence of reduced binding in some areas, which would be consistent with increased synaptic availability of serotonin in people with depression, if this was the original, causal abnormaly. However, effects of prior antidepressant use were not reliably excluded. One meta-analysis of tryptophan depletion studies found no effect in most healthy volunteers ( n = 566), but weak evidence of an effect in those with a family history of depression ( n = 75). Another systematic review ( n = 342) and a sample of ten subsequent studies ( n = 407) found no effect in volunteers. No systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies has been performed since 2007. The two largest and highest quality studies of the SERT gene, one genetic association study ( n = 115,257) and one collaborative meta-analysis ( n = 43,165), revealed no evidence of an association with depression, or of an interaction between genotype, stress and depression. The main areas of serotonin research provide no consistent evidence of there being an association between serotonin and depression, and no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations. Some evidence was consistent with the possibility that long-term antidepressant use reduces serotonin concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Genetic contributions to brain serotonin transporter levels in healthy adults

Neocortical serotonin 2A receptor binding, neuroticism and risk of developing depression in healthy individuals

The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies

Introduction.

The idea that depression is the result of abnormalities in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT), has been influential for decades, and provides an important justification for the use of antidepressants. A link between lowered serotonin and depression was first suggested in the 1960s [ 1 ], and widely publicised from the 1990s with the advent of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Although it has been questioned more recently [ 5 , 6 ], the serotonin theory of depression remains influential, with principal English language textbooks still giving it qualified support [ 7 , 8 ], leading researchers endorsing it [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], and much empirical research based on it [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Surveys suggest that 80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance’ [ 15 , 16 ]. Many general practitioners also subscribe to this view [ 17 ] and popular websites commonly cite the theory [ 18 ].

It is often assumed that the effects of antidepressants demonstrate that depression must be at least partially caused by a brain-based chemical abnormality, and that the apparent efficacy of SSRIs shows that serotonin is implicated. Other explanations for the effects of antidepressants have been put forward, however, including the idea that they work via an amplified placebo effect or through their ability to restrict or blunt emotions in general [ 19 , 20 ].

Despite the fact that the serotonin theory of depression has been so influential, no comprehensive review has yet synthesised the relevant evidence. We conducted an ‘umbrella’ review of the principal areas of relevant research, following the model of a similar review examining prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder [ 21 ]. We sought to establish whether the current evidence supports a role for serotonin in the aetiology of depression, and specifically whether depression is associated with indications of lowered serotonin concentrations or activity.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The present umbrella review was reported in accordance with the 2009 PRISMA statement [ 22 ]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO in December 2020 (registration number CRD42020207203) ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=207203 ). This was subsequently updated to reflect our decision to modify the quality rating system for some studies to more appropriately appraise their quality, and to include a modified GRADE to assess the overall certainty of the findings in each category of the umbrella review.

In order to cover the different areas and to manage the large volume of research that has been conducted on the serotonin system, we conducted an ‘umbrella’ review. Umbrella reviews survey existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses relevant to a research question and represent one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis available [ 23 ]. Although they are traditionally restricted to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to identify the best evidence available. Therefore, we also included some large studies that combined data from individual studies but did not employ conventional systematic review methods, and one large genetic study. The latter used nationwide databases to capture more individuals than entire meta-analyses, so is likely to provide even more reliable evidence than syntheses of individual studies.

We first conducted a scoping review to identify areas of research consistently held to provide support for the serotonin hypothesis of depression. Six areas were identified, addressing the following questions: (1) Serotonin and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA–whether there are lower levels of serotonin and 5-HIAA in body fluids in depression; (2) Receptors - whether serotonin receptor levels are altered in people with depression; (3) The serotonin transporter (SERT) - whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter in people with depression (which would lower synaptic levels of serotonin); (4) Depletion studies - whether tryptophan depletion (which lowers available serotonin) can induce depression; (5) SERT gene – whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter gene in people with depression; (6) Whether there is an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression.

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and large database studies in these six areas in PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO using the Healthcare Databases Advanced Search tool provided by Health Education England and NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). Searches were conducted until December 2020.

We used the following terms in all searches: (depress* OR affective OR mood) AND (systematic OR meta-analysis), and limited searches to title and abstract, since not doing so produced numerous irrelevant hits. In addition, we used terms specific to each area of research (full details are provided in Table S1 , Supplement). We also searched citations and consulted with experts.

Inclusion criteria were designed to identify the best available evidence in each research area and consisted of:

Research synthesis including systematic reviews, meta-analysis, umbrella reviews, individual patient meta-analysis and large dataset analysis.

Studies that involve people with depressive disorders or, for experimental studies (tryptophan depletion), those in which mood symptoms are measured as an outcome.

Studies of experimental procedures (tryptophan depletion) involving a sham or control condition.

Studies published in full in peer reviewed literature.

Where more than five systematic reviews or large analyses exist, the most recent five are included.

Exclusion criteria consisted of:

Animal studies.

Studies exclusively concerned with depression in physical conditions (e.g. post stroke or Parkinson’s disease) or exclusively focusing on specific subtypes of depression such as postpartum depression, depression in children, or depression in bipolar disorder.

No language or date restrictions were applied. In areas in which no systematic review or meta-analysis had been done within the last 10 years, we also selected the ten most recent studies at the time of searching (December 2020) for illustration of more recent findings. We performed this search using the same search string for this domain, without restricting it to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data analysis

Each member of the team was allocated one to three domains of serotonin research to search and screen for eligible studies using abstract and full text review. In case of uncertainty, the entire team discussed eligibility to reach consensus.

For included studies, data were extracted by two reviewers working independently, and disagreement was resolved by consensus. Authors of papers were contacted for clarification when data was missing or unclear.

We extracted summary effects, confidence intervals and measures of statistical significance where these were reported, and, where relevant, we extracted data on heterogeneity. For summary effects in the non-genetic studies, preference was given to the extraction and reporting of effect sizes. Mean differences were converted to effect sizes where appropriate data were available.

We did not perform a meta-analysis of the individual meta-analyses in each area because they included overlapping studies [ 24 ]. All extracted data is presented in Table 1 . Sensitivity analyses were reported where they had substantial bearing on interpretation of findings.

The quality rating of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was assessed using AMSTAR-2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) [ 25 ]. For two studies that did not employ conventional systematic review methods [ 26 , 27 ] we used a modified version of the AMSTAR-2 (see Table S3 ). For the genetic association study based on a large database analysis we used the STREGA assessment (STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies) (Table S4 ) [ 28 ]. Each study was rated independently by at least two authors. We report ratings of individual items on the relevant measure, and the percentage of items that were adequately addressed by each study (Table 1 , with further detail in Tables S3 and S4 ).

Alongside quality ratings, two team members (JM, MAH) rated the certainty of the results of each study using a modified version of the GRADE guidelines [ 29 ]. Following the approach of Kennis et al. [ 21 ], we devised six criteria relevant to the included studies: whether a unified analysis was conducted on original data; whether confounding by antidepressant use was adequately addressed; whether outcomes were pre-specified; whether results were consistent or heterogeneity was adequately addressed if present; whether there was a likelihood of publication bias; and sample size. The importance of confounding by effects of current or past antidepressant use has been highlighted in several studies [ 30 , 31 ]. The results of each study were scored 1 or 0 according to whether they fulfilled each criteria, and based on these ratings an overall judgement was made about the certainty of evidence across studies in each of the six areas of research examined. The certainty of each study was based on an algorithm that prioritised sample size and uniform analysis using original data (explained more fully in the supplementary material), following suggestions that these are the key aspects of reliability [ 27 , 32 ]. An assessment of the overall certainty of each domain of research examining the role of serotonin was determined by consensus of at least two authors and a direction of effect indicated.

Search results and quality rating

Searching identified 361 publications across the 6 different areas of research, among which seventeen studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 and Table S1 for details of the selection process). Included studies, their characteristics and results are shown in Table 1 . As no systematic review or meta-analysis had been performed within the last 10 years on serotonin depletion, we also identified the 10 latest studies for illustration of more recent research findings (Table 2 ).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagramme.

Quality ratings are summarised in Table 1 and reported in detail in Tables S2 – S3 . The majority (11/17) of systematic reviews and meta-analyses satisfied less than 50% of criteria. Only 31% adequately assessed risk of bias in individual studies (a further 44% partially assessed this), and only 50% adequately accounted for risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review. One collaborative meta-analysis of genetic studies was considered to be of high quality due to the inclusion of several measures to ensure consistency and reliability [ 27 ]. The large genetic analysis of the effect of SERT polymorphisms on depression, satisfied 88% of the STREGA quality criteria [ 32 ].

Serotonin and 5-HIAA

Serotonin can be measured in blood, plasma, urine and CSF, but it is rapidly metabolised to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). CSF is thought to be the ideal resource for the study of biomarkers of putative brain diseases, since it is in contact with brain interstitial fluid [ 33 ]. However, collecting CSF samples is invasive and carries some risk, hence large-scale studies are scarce.

Three studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (Table 1 ). One meta-analysis of three large observational cohort studies of post-menopausal women, revealed lower levels of plasma 5-HT in women with depression, which did not, however, reach statistical significance of p < 0.05 after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Sensitivity analyses revealed that antidepressants were strongly associated with lower serotonin levels independently of depression.

Two meta-analyses of a total of 19 studies of 5-HIAA in CSF (seven studies were included in both) found no evidence of an association between 5-HIAA concentrations and depression.

Fourteen different serotonin receptors have been identified, with most research on depression focusing on the 5-HT 1A receptor [ 11 , 34 ]. Since the functions of other 5-HT receptors and their relationship to depression have not been well characterised, we restricted our analysis to data on 5-HT 1A receptors [ 11 , 34 ]. 5-HT 1A receptors, known as auto-receptors, inhibit the release of serotonin pre-synaptically [ 35 ], therefore, if depression is the result of reduced serotonin activity caused by abnormalities in the 5-HT 1A receptor, people with depression would be expected to show increased activity of 5-HT 1A receptors compared to those without [ 36 ].

Two meta-analyses satisfied inclusion criteria, involving five of the same studies [ 37 , 38 ] (see Table 1 ). The majority of results across the two analyses suggested either no difference in 5-HT 1A receptors between people with depression and controls, or a lower level of these inhibitory receptors, which would imply higher concentrations or activity of serotonin in people with depression. Both meta-analyses were based on studies that predominantly involved patients who were taking or had recently taken (within 1–3 weeks of scanning) antidepressants or other types of psychiatric medication, and both sets of authors commented on the possible influence of prior or current medication on findings. In addition, one analysis was of very low quality [ 37 ], including not reporting on the numbers involved in each analysis and using one-sided p-values, and one was strongly influenced by three studies and publication bias was present [ 38 ].

The serotonin transporter (SERT)

The serotonin transporter protein (SERT) transports serotonin out of the synapse, thereby lowering the availability of serotonin in the synapse [ 39 , 40 ]. Animals with an inactivated gene for SERT have higher levels of extra-cellular serotonin in the brain than normal [ 41 , 42 , 43 ] and SSRIs are thought to work by inhibiting the action of SERT, and thus increasing levels of serotonin in the synaptic cleft [ 44 ]. Although changes in SERT may be a marker for other abnormalities, if depression is caused by low serotonin availability or activity, and if SERT is the origin of that deficit, then the amount or activity of SERT would be expected to be higher in people with depression compared to those without [ 40 ]. SERT binding potential is an index of the concentration of the serotonin transporter protein and SERT concentrations can also be measured post-mortem.

Three overlapping meta-analyses based on a total of 40 individual studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (See Table 1 ) [ 37 , 39 , 45 ]. Overall, the data indicated possible reductions in SERT binding in some brain areas, although areas in which effects were detected were not consistent across the reviews. In addition, effects of antidepressants and other medication cannot be ruled out, since most included studies mainly or exclusively involved people who had a history of taking antidepressants or other psychiatric medications. Only one meta-analysis tested effects of antidepressants, and although results were not influenced by the percentage of drug-naïve patients in each study, numbers were small so it is unlikely that medication-related effects would have been reliably detected [ 45 ]. All three reviews cited evidence from animal studies that antidepressant treatment reduces SERT [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. None of the analyses corrected for multiple testing, and one review was of very low quality [ 37 ]. If the results do represent a positive finding that is independent of medication, they would suggest that depression is associated with higher concentrations or activity of serotonin.

Depletion studies

Tryptophan depletion using dietary means or chemicals, such as parachlorophenylalanine (PCPA), is thought to reduce serotonin levels. Since PCPA is potentially toxic, reversible tryptophan depletion using an amino acid drink that lacks tryptophan is the most commonly used method and is thought to affect serotonin within 5–7 h of ingestion. Questions remain, however, about whether either method reliably reduces brain serotonin, and about other effects including changes in brain nitrous oxide, cerebrovascular changes, reduced BDNF and amino acid imbalances that may be produced by the manipulations and might explain observed effects independent of possible changes in serotonin activity [ 49 ].

One meta-analysis and one systematic review fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Table 1 ). Data from studies involving volunteers mostly showed no effect, including a meta-analysis of parallel group studies [ 50 ]. In a small meta-analysis of within-subject studies involving 75 people with a positive family history, a minor effect was found, with people given the active depletion showing a larger decrease in mood than those who had a sham procedure [ 50 ]. Across both reviews, studies involving people diagnosed with depression showed slightly greater mood reduction following tryptophan depletion than sham treatment overall, but most participants had taken or were taking antidepressants and participant numbers were small [ 50 , 51 ].

Since these research syntheses were conducted more than 10 years ago, we searched for a systematic sample of ten recently published studies (Table 2 ). Eight studies conducted with healthy volunteers showed no effects of tryptophan depletion on mood, including the only two parallel group studies. One study presented effects in people with and without a family history of depression, and no differences were apparent in either group [ 52 ]. Two cross-over studies involving people with depression and current or recent use of antidepressants showed no convincing effects of a depletion drink [ 53 , 54 ], although one study is reported as positive mainly due to finding an improvement in mood in the group given the sham drink [ 54 ].

SERT gene and gene-stress interactions

A possible link between depression and the repeat length polymorphism in the promoter region of the SERT gene (5-HTTLPR), specifically the presence of the short repeats version, which causes lower SERT mRNA expression, has been proposed [ 55 ]. Interestingly, lower levels of SERT would produce higher levels of synaptic serotonin. However, more recently, this hypothesis has been superseded by a focus on the interaction effect between this polymorphism, depression and stress, with the idea that the short version of the polymorphism may only give rise to depression in the presence of stressful life events [ 55 , 56 ]. Unlike other areas of serotonin research, numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of genetic studies have been conducted, and most recently a very large analysis based on a sample from two genetic databanks. Details of the five most recent studies that have addressed the association between the SERT gene and depression, and the interaction effect are detailed in Table 1 .

Although some earlier meta-analyses of case-control studies showed a statistically significant association between the 5-HTTLPR and depression in some ethnic groups [ 57 , 58 ], two recent large, high quality studies did not find an association between the SERT gene polymorphism and depression [ 27 , 32 ]. These two studies consist of by far the largest and most comprehensive study to date [ 32 ] and a high-quality meta-analysis that involved a consistent re-analysis of primary data across all conducted studies, including previously unpublished data, and other comprehensive quality checks [ 27 , 59 ] (see Table 1 ).

Similarly, early studies based on tens of thousands of participants suggested a statistically significant interaction between the SERT gene, forms of stress or maltreatment and depression [ 60 , 61 , 62 ], with a small odds ratio in the only study that reported this (1.18, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.28) [ 62 ]. However, the two recent large, high-quality studies did not find an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression (Border et al [ 32 ] and Culverhouse et al.) [ 27 ] (see Table 1 ).

Overall results

Table 3 presents the modified GRADE ratings for each study and the overall rating of the strength of evidence in each area. Areas of research that provided moderate or high certainty of evidence such as the studies of plasma serotonin and metabolites and the genetic and gene-stress interaction studies all showed no association between markers of serotonin activity and depression. Some other areas suggested findings consistent with increased serotonin activity, but evidence was of very low certainty, mainly due to small sample sizes and possible residual confounding by current or past antidepressant use. One area - the tryptophan depletion studies - showed very low certainty evidence of lowered serotonin activity or availability in a subgroup of volunteers with a family history of depression. This evidence was considered very low certainty as it derived from a subgroup of within-subject studies, numbers were small, and there was no information on medication use, which may have influenced results. Subsequent research has not confirmed an effect with numerous negative studies in volunteers.

Our comprehensive review of the major strands of research on serotonin shows there is no convincing evidence that depression is associated with, or caused by, lower serotonin concentrations or activity. Most studies found no evidence of reduced serotonin activity in people with depression compared to people without, and methods to reduce serotonin availability using tryptophan depletion do not consistently lower mood in volunteers. High quality, well-powered genetic studies effectively exclude an association between genotypes related to the serotonin system and depression, including a proposed interaction with stress. Weak evidence from some studies of serotonin 5-HT 1A receptors and levels of SERT points towards a possible association between increased serotonin activity and depression. However, these results are likely to be influenced by prior use of antidepressants and its effects on the serotonin system [ 30 , 31 ]. The effects of tryptophan depletion in some cross-over studies involving people with depression may also be mediated by antidepressants, although these are not consistently found [ 63 ].

The chemical imbalance theory of depression is still put forward by professionals [ 17 ], and the serotonin theory, in particular, has formed the basis of a considerable research effort over the last few decades [ 14 ]. The general public widely believes that depression has been convincingly demonstrated to be the result of serotonin or other chemical abnormalities [ 15 , 16 ], and this belief shapes how people understand their moods, leading to a pessimistic outlook on the outcome of depression and negative expectancies about the possibility of self-regulation of mood [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. The idea that depression is the result of a chemical imbalance also influences decisions about whether to take or continue antidepressant medication and may discourage people from discontinuing treatment, potentially leading to lifelong dependence on these drugs [ 67 , 68 ].

As with all research synthesis, the findings of this umbrella review are dependent on the quality of the included studies, and susceptible to their limitations. Most of the included studies were rated as low quality on the AMSTAR-2, but the GRADE approach suggested some findings were reasonably robust. Most of the non-genetic studies did not reliably exclude the potential effects of previous antidepressant use and were based on relatively small numbers of participants. The genetic studies, in particular, illustrate the importance of methodological rigour and sample size. Whereas some earlier, lower quality, mostly smaller studies produced marginally positive findings, these were not confirmed in better-conducted, larger and more recent studies [ 27 , 32 ]. The identification of depression and assessment of confounders and interaction effects were limited by the data available in the original studies on which the included reviews and meta-analyses were based. Common methods such as the categorisation of continuous measures and application of linear models to non-linear data may have led to over-estimation or under-estimation of effects [ 69 , 70 ], including the interaction between stress and the SERT gene. The latest systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies was conducted in 2007, and there has been considerable research produced since then. Hence, we provided a snapshot of the most recent evidence at the time of writing, but this area requires an up to date, comprehensive data synthesis. However, the recent studies were consistent with the earlier meta-analysis with little evidence for an effect of tryptophan depletion on mood.

Although umbrella reviews typically restrict themselves to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to provide the most comprehensive possible overview. Therefore, we chose to include meta-analyses that did not involve a systematic review and a large genetic association study on the premise that these studies contribute important data on the question of whether the serotonin hypothesis of depression is supported. As a result, the AMSTAR-2 quality rating scale, designed to evaluate the quality of conventional systematic reviews, was not easily applicable to all studies and had to be modified or replaced in some cases.

One study in this review found that antidepressant use was associated with a reduction of plasma serotonin [ 26 ], and it is possible that the evidence for reductions in SERT density and 5-HT 1A receptors in some of the included imaging study reviews may reflect compensatory adaptations to serotonin-lowering effects of prior antidepressant use. Authors of one meta-analysis also highlighted evidence of 5-HIAA levels being reduced after long-term antidepressant treatment [ 71 ]. These findings suggest that in the long-term antidepressants might produce compensatory changes [ 72 ] that are opposite to their acute effects [ 73 , 74 ]. Lowered serotonin availability has also been demonstrated in animal studies following prolonged antidepressant administration [ 75 ]. Further research is required to clarify the effects of different drugs on neurochemical systems, including the serotonin system, especially during and after long-term use, as well as the physical and psychological consequences of such effects.

This review suggests that the huge research effort based on the serotonin hypothesis has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis to depression. This is consistent with research on many other biological markers [ 21 ]. We suggest it is time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression is not empirically substantiated.

Data availability

All extracted data is available in the paper and supplementary materials. Further information about the decision-making for each rating for categories of the AMSTAR-2 and STREGA are available on request.

Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:1237–64.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. What Is Psychiatry? 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-psychiatry-menu .

GlaxoSmithKline. Paxil XR. 2009. www.Paxilcr.com (site no longer available). Last accessed 27th Jan 2009.

Eli Lilly. Prozac - How it works. 2006. www.prozac.com/how_prozac/how_it_works.jsp?reqNavId=2.2 . (site no longer available). Last accessed 10th Feb 2006.

Healy D. Serotonin and depression. BMJ: Br Med J. 2015;350:h1771.

Article Google Scholar

Pies R. Psychiatry’s New Brain-Mind and the Legend of the “Chemical Imbalance.” 2011. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatrys-new-brain-mind-and-legend-chemical-imbalance . Accessed March 2, 2021.

Geddes JR, Andreasen NC, Goodwin GM. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2020.

Book Google Scholar

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 10th Editi. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2017.

Cowen PJ, Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatry. 2015;14:158–60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:409–18.

Yohn CN, Gergues MM, Samuels BA. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol Brain. 2017;10:28.

Hahn A, Haeusler D, Kraus C, Höflich AS, Kranz GS, Baldinger P, et al. Attenuated serotonin transporter association between dorsal raphe and ventral striatum in major depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:3857–66.

Amidfar M, Colic L, Kim MWAY-K. Biomarkers of major depression related to serotonin receptors. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2018;14:239–44.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Albert PR, Benkelfat C, Descarries L. The neurobiology of depression—revisiting the serotonin hypothesis. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:2378–81.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pilkington PD, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. The Australian public’s beliefs about the causes of depression: associated factors and changes over 16 years. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:356–62.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. A disease like any other? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–30.

Read J, Renton J, Harrop C, Geekie J, Dowrick C. A survey of UK general practitioners about depression, antidepressants and withdrawal: implementing the 2019 Public Health England report. Therapeutic Advances in. Psychopharmacology. 2020;10:204512532095012.

Google Scholar

Demasi M, Gøtzsche PC. Presentation of benefits and harms of antidepressants on websites: A cross-sectional study. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2020;31:53–65.

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Kirsch I. Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based. Medicine. 2020;25:130–130.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D. Do antidepressants cure or create abnormal brain states? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e240.

Kennis M, Gerritsen L, van Dalen M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:321–38.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21:95–100.

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2,. version 6.Cochrane; 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Huang T, Balasubramanian R, Yao Y, Clish CB, Shadyab AH, Liu B, et al. Associations of depression status with plasma levels of candidate lipid and amino acid metabolites: a meta-analysis of individual data from three independent samples of US postmenopausal women. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00870-9 .

Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T, et al. Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:133–42.

Little J, Higgins JPT, Ioannidis JPA, Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, et al. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)— An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000022.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. What is quality of evidence and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8.

Yoon HS, Hattori K, Ogawa S, Sasayama D, Ota M, Teraishi T, et al. Relationships of cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels with clinical variables in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e947–56.

Kugaya A, Seneca NM, Snyder PJ, Williams SA, Malison RT, Baldwin RM, et al. Changes in human in vivo serotonin and dopamine transporter availabilities during chronic antidepressant administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:413–20.

Border R, Johnson EC, Evans LM, Smolen A, Berley N, Sullivan PF, et al. No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:376–87.

Ogawa S, Tsuchimine S, Kunugi H. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite concentrations in depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of historic evidence. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;105:137–46.

Nautiyal KM, Hen R. Serotonin receptors in depression: from A to B. F1000Res. 2017;6:123.

Rojas PS, Neira D, Muñoz M, Lavandero S, Fiedler JL. Serotonin (5‐HT) regulates neurite outgrowth through 5‐HT1A and 5‐HT7 receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1000–9.

Kaufman J, DeLorenzo C, Choudhury S, Parsey RV. The 5-HT1A receptor in Major Depressive Disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:397–410.

Nikolaus S, Müller H-W, Hautzel H. Different patterns of 5-HT receptor and transporter dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders – a comparative analysis of in vivo imaging findings. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27:27–59.

Wang L, Zhou C, Zhu D, Wang X, Fang L, Zhong J, et al. Serotonin-1A receptor alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of molecular imaging studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–9.

Kambeitz JP, Howes OD. The serotonin transporter in depression: Meta-analysis of in vivo and post mortem findings and implications for understanding and treating depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:358–66.