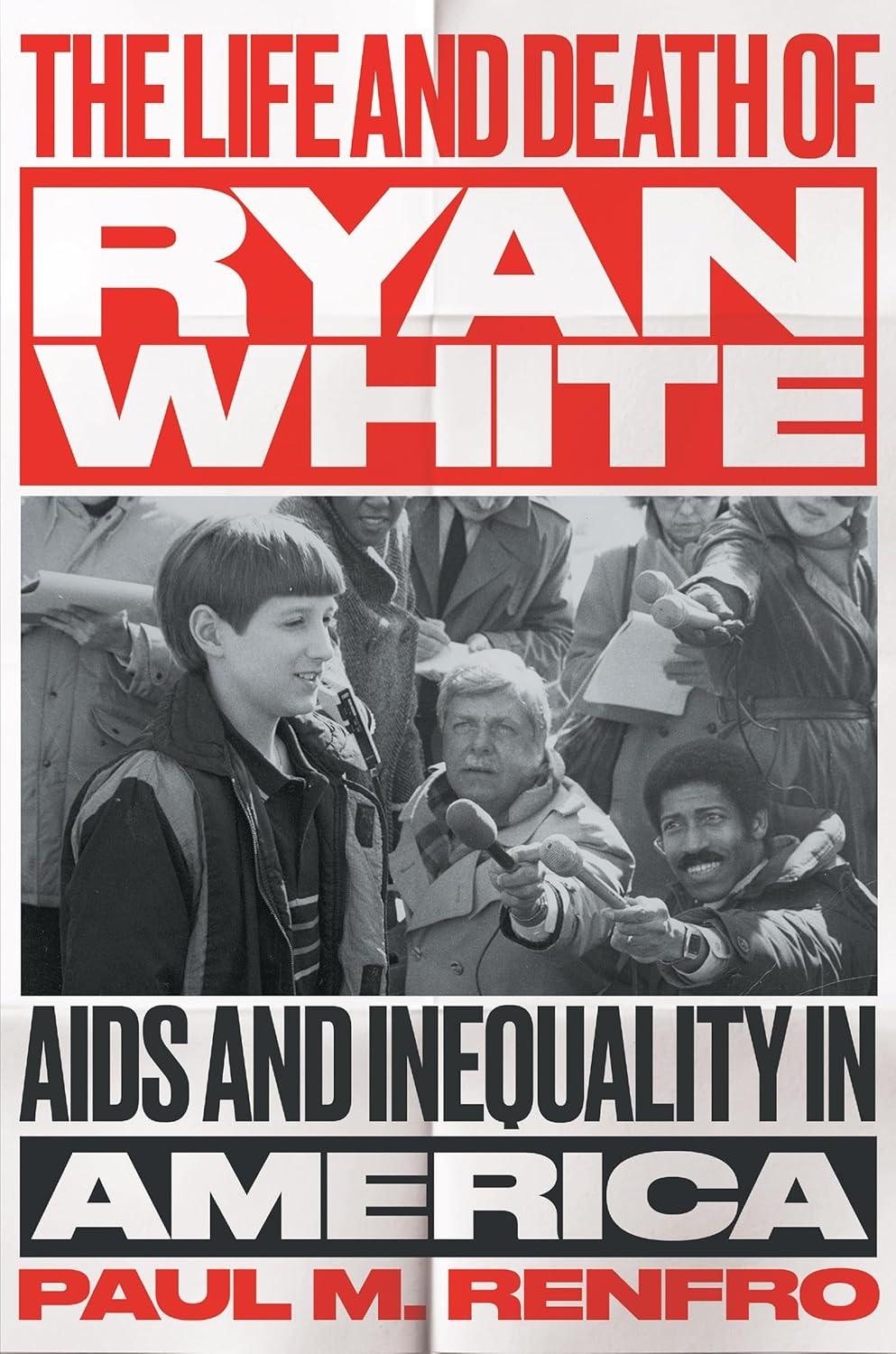

“I Am the Face of AIDS”

...a face of AIDS that caring human beings could not turn their back upon. The committee report vividly illustrated the power of White’s perceived innocence and exceptional victimhood. While “caring human beings” could apparently spurn other PWAs, they could not in good conscience ignore Ryan.

To be sure, the CARE Act was quite popular with legislators even before Ryan’s name was attached to the bill. An increasingly visible and militant AIDS movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s had prompted a stronger government response to the epidemic, particularly at the federal level. Upon its introduction in early March 1990—and before it was named for Ryan—S. 2240 boasted one sponsor and 25 cosponsors. It secured another six cosponsors in early April. But Ryan’s name and image rendered the bill all but unassailable. Calling it the Ryan White CARE Act enabled lawmakers and activists to further “sanitize” HIV/AIDS—and, in so doing, to authorize AIDS funding without incurring the wrath of antigay and antidrug forces. Indeed, attaching Ryan’s name to the Senate bill attracted additional cosponsors, thereby establishing a filibuster-proof majority that would keep the virulently homophobic senator Jesse Helms at bay. By the time the bill passed a (heavily Democratic) Senate in May, 66 Senators had cosponsored it.

Yet because Ryan was such a potent and popular symbol, the invocation of his name and image by federal lawmakers proved contentious. Everyone wanted to be on Ryan’s side. For Ted Kennedy (D-Massachusetts) and other supporters of the CARE Act—even activists who may have privately opposed the use of “a politically safe symbol”—that meant passing the bill in Ryan’s name. For Jesse Helms and his ilk, that meant “protecting” White and other “innocent victim[s]” from MSM, IV drug users, Hollywood elites, and even certain congresspeople. Through his characteristically cruel and incendiary rhetoric, Helms sought to wrest control of Ryan’s name and image away from Kennedy and other CARE Act proponents. Although in one sense his efforts failed, given the wide margins by which the Ryan White CARE Act passed, they also revealed the limits of respectability politics and the politics of innocence in this context. Specifically, Helms correctly identified White as an exceptional PWA who helped direct public attention away from stigmatized groups disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS—particularly MSM and those who use intravenous drugs. Through this and related observations, Helms reinforced the perceived symbolic and moral distance between White and other, more “typical” PWAs and successfully promoted policies to further police and subjugate those in the latter category.

As the Senate debated the proposed Ryan White CARE Act in mid-May 1990, Helms inveighed against “the Hollywood and media crowd,” the “homosexual segment of the AIDS lobby,” congresspeople, and other groups that he claimed were “exploit[ing]” White. For Helms, “the cynical exploitation...