Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Write About Yourself in a College Essay | Examples

Published on September 21, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023.

An insightful college admissions essay requires deep self-reflection, authenticity, and a balance between confidence and vulnerability. Your essay shouldn’t just be a resume of your experiences; colleges are looking for a story that demonstrates your most important values and qualities.

To write about your achievements and qualities without sounding arrogant, use specific stories to illustrate them. You can also write about challenges you’ve faced or mistakes you’ve made to show vulnerability and personal growth.

Table of contents

Start with self-reflection, how to write about challenges and mistakes, how to write about your achievements and qualities, how to write about a cliché experience, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Before you start writing, spend some time reflecting to identify your values and qualities. You should do a comprehensive brainstorming session, but here are a few questions to get you started:

- What are three words your friends or family would use to describe you, and why would they choose them?

- Whom do you admire most and why?

- What are the top five things you are thankful for?

- What has inspired your hobbies or future goals?

- What are you most proud of? Ashamed of?

As you self-reflect, consider how your values and goals reflect your prospective university’s program and culture, and brainstorm stories that demonstrate the fit between the two.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing about difficult experiences can be an effective way to show authenticity and create an emotional connection to the reader, but choose carefully which details to share, and aim to demonstrate how the experience helped you learn and grow.

Be vulnerable

It’s not necessary to have a tragic story or a huge confession. But you should openly share your thoughts, feelings, and experiences to evoke an emotional response from the reader. Even a cliché or mundane topic can be made interesting with honest reflection. This honesty is a preface to self-reflection and insight in the essay’s conclusion.

Don’t overshare

With difficult topics, you shouldn’t focus too much on negative aspects. Instead, use your challenging circumstances as a brief introduction to how you responded positively.

Share what you have learned

It’s okay to include your failure or mistakes in your essay if you include a lesson learned. After telling a descriptive, honest story, you should explain what you learned and how you applied it to your life.

While it’s good to sell your strengths, you also don’t want to come across as arrogant. Instead of just stating your extracurricular activities, achievements, or personal qualities, aim to discreetly incorporate them into your story.

Brag indirectly

Mention your extracurricular activities or awards in passing, not outright, to avoid sounding like you’re bragging from a resume.

Use stories to prove your qualities

Even if you don’t have any impressive academic achievements or extracurriculars, you can still demonstrate your academic or personal character. But you should use personal examples to provide proof. In other words, show evidence of your character instead of just telling.

Many high school students write about common topics such as sports, volunteer work, or their family. Your essay topic doesn’t have to be groundbreaking, but do try to include unexpected personal details and your authentic voice to make your essay stand out .

To find an original angle, try these techniques:

- Focus on a specific moment, and describe the scene using your five senses.

- Mention objects that have special significance to you.

- Instead of following a common story arc, include a surprising twist or insight.

Your unique voice can shed new perspective on a common human experience while also revealing your personality. When read out loud, the essay should sound like you are talking.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

First, spend time reflecting on your core values and character . You can start with these questions:

However, you should do a comprehensive brainstorming session to fully understand your values. Also consider how your values and goals match your prospective university’s program and culture. Then, brainstorm stories that illustrate the fit between the two.

When writing about yourself , including difficult experiences or failures can be a great way to show vulnerability and authenticity, but be careful not to overshare, and focus on showing how you matured from the experience.

Through specific stories, you can weave your achievements and qualities into your essay so that it doesn’t seem like you’re bragging from a resume.

Include specific, personal details and use your authentic voice to shed a new perspective on a common human experience.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write About Yourself in a College Essay | Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/write-about-yourself/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, style and tone tips for your college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to make your college essay stand out | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Essays About Myself: Top 5 Essay Examples Plus Prompts

We are all unique individuals, each with traits, skills, and qualities we should be proud of. Here are examples and prompts on essays about myself .

It is good to reflect on ourselves from time to time. When applying for university or a new job, you may be asked to write about yourself to give the institution a better picture of yourself. Self-understanding and reflection are essential if you want to make a compelling argument for yourself.

Reflect on your life: look back on the people you’ve met, the places you’ve been, and the experiences you’ve had, and think about how they have shaped you into the person you have become today. Think of the bigger picture and be sure to consider who you are based on what others think and say about you, not just who you think you are.

If you are tasked with the prompt, “essays about myself,” keep reading to see some essay examples.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. It’s My Life by Ann Smith

2. how i see myself by leticia woods, 3. the truth about myself by madeline dyer, 4. what we see in others is a reflection of ourselves by sandra brossman, 5. a letter to myself by gladys mclaughlin, 1. introducing yourself, 2. describing your strengths and weaknesses, 3. what sets you apart from others, 4. your beliefs and values, 5. an experience that has defined you as a person, 6. what family means to you, 7. your favorite pasttime.

“Sure, I’ve had bad experiences in my life too, but this is exactly what made me the way I am now: grateful, full of love, with a desire to study well because it will help me become a successful person in future and have a high quality of life. I believe that it is manifesting day by day and I feel even more responsibility for what I do and where I go. With all I already have, I know that I’m on the right path and I will do my best to inspire others to live the way they feel like living as well.”

In her essay, Smith describes her interests, habits, and qualities. She writes that she is sociable, enthusiastic about studying, and friendly. She also touches on others’ opinions of her- that she is funny. One of Smith’s hobbies is photography, which allowed her to meet her best friend. She aims to study hard so she can be successful on whatever path she may follow, and inspire others to live their best life.

“It is this drive that will carry me through my degree program and allow me to absorb the education that I receive and develop solid practical applications from this knowledge. I feel that I will eventually become highly successful in my chosen field because my past has clearly shown my commitment to excellence in every endeavor that I have chosen. Because I remain incredibly focused and committed for future success, I know that my future will be as rewarding as my past.”

Woods discusses how her identity helps her achieve her career goals. First, her commitment to her education is a great asset. Second, prior education and her service in the US Air Force allowed her to learn much about life, the world, and herself, and she was able to learn about different cultures. She believes that experience, devotion, and knowledge will allow her to achieve her dreams.

“I’m getting better as I recover from the brain inflammation which caused my OCD, but I want to have a day like that. A day where I can relax and enjoy life fully again. A day where I haven’t a care in the world. And for that, I need to be kind to myself. I need to relax and remove any pressure I place on myself.”

Dyer reflects on an important part of herself- her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Brain inflammation has made her a perfectionist, and she cannot relax. She is constantly compelled by an inner voice to do things she “should” be doing. She wants to be happy, and will try to shut off this voice by practicing self-affirmation. You might also be interested in these essays about discovering yourself .

“Believe it or not, forgiving YOURSELF is the most effective way to disengage from negative interactions with people. We can only love and accept others to the degree that we love and accept ourselves. When you make it a habit to learn from your relationships, eventually you will discover that you can observe negative traits within others without judgment and without getting hooked into someone else’s drama.”

In her essay, Brossman writes how we see what we desire for ourselves in others. Our relationships help us understand ourselves better; we see people’s bad qualities and criticize them, professing that we will not be like them. On the other hand, we see qualities we like and try to imitate them. To become a better version of yourself, you should learn from your relationships and emulate desirable qualities.

“I never tell anyone that I am tired of work or study. Success will come to those who get up and go far. This is my life motto which always reminds me of how vital it is to be hard-working and resilient towards failures. I learn that no matter what others say (even mother and father) if their

thoughts contradict my goals, I don’t have to listen to them. Nobody will live your life, and nobody should tell you who you are and what you are.”

Mclaughlin writes a letter to her future self, explaining what she envisions for herself in the coming years. She writes about who she is now and describes her vision for how much better she will be in the future. She believes that she will have great encounters that will teach her about life, a loving, kind family, and an independent spirit that will triumph over all her struggles

Writing Prompts For Essays About Myself

Write a basic description of yourself; describe where you live, your school or job, and your family and friends. You should also give readers a glimpse of your personality- are you outgoing, shy, or sporty? If you want to write more, you can also briefly explain your hobbies, interests, and skills.

Each of us has our own strengths and weaknesses. Reflect on what you are good at and what you can improve on and select 1-2 from each to write about. Discuss what you can do to work on your weaknesses and improve yourself.

An essential part of yourself is your uniqueness; for a strong essay about “myself,” think about beliefs, qualities, or values that set you apart from others. Write about one or more, but be sure to explain your choices clearly. You can write about what separates you in the context of your family, friend group, culture, or even society as a whole.

Your beliefs and values are at the core of your being, as they guide the decisions you make every day. Discuss some of your basic beliefs and values and explain why they are important to you. For a stronger essay, be sure to explain how you use these in day-to-day life; give concrete examples of situations in which these beliefs and values are used.

We are all shaped by our past experiences. Reflect on an experience, whether that be an achievement, setback, or just a fun memory, and explain its significance to you. Retell the story in detail and describe how it has impacted you and helped make you the person you are today.

More often than not, family plays a big role in forming us. To give readers a better idea of your identity, describe your idea of family. Discuss its significance, impact, and role in your life. You may also choose to write about how your family has helped shape you into who you are. This should be based on personal experience; refrain from using external sources to inspire you.

Our likes and dislikes are an important part of who we are as well; in your essay, discuss a hobby of yours, preferably one you have been interested in for a long period of time, and explain why you enjoy it so much. You should also write about how it has helped you become yourself and made you a better person.

Grammarly is one of our top grammar checkers. Find out why in this Grammarly review . If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

Self-Introduction Essay

Self introduction essay generator.

A Self Introduction Essay is a window into your personality, goals, and experiences. Our guide, supplemented with varied essay examples , offers insights into crafting a compelling narrative about yourself. Ideal for college applications, job interviews, or personal reflections, these examples demonstrate how to weave your personal story into an engaging essay. Learn to highlight your strengths, aspirations, and journey in a manner that captivates your readers, making your introduction not just informative but also memorable.

What is Self Introduction Essay? A self-introduction essay is a written piece where you describe yourself in a personal and detailed way. It’s a way to introduce who you are, including your name, background, interests, achievements, and goals. This type of essay is often used for college or job applications, allowing others to get to know you better. It’s an opportunity to showcase your personality, experiences, and what makes you unique. Writing a self-introduction essay involves talking about your educational background, professional experiences if any, personal interests, and future aspirations. It’s a chance to highlight your strengths, achievements, and to share your personal story in a way that is engaging and meaningful.

Do you still remember the first time you’ve written an essay ? I bet you don’t even know it’s called an “essay” back then. And back then you might be wondering what’s the purpose such composition, and why are you writing something instead of hanging out with your friends.

Download Self-Introduction Essay Bundle

Now, you probably are already familiar with the definition of an essay, and the basics of writing one. You’re also probably aware of the purpose of writing essays and the different writing styles one may use in writing a composition. Here, we will be talking about self-introduction essay, and look into different example such as personal essay which you may refer to.

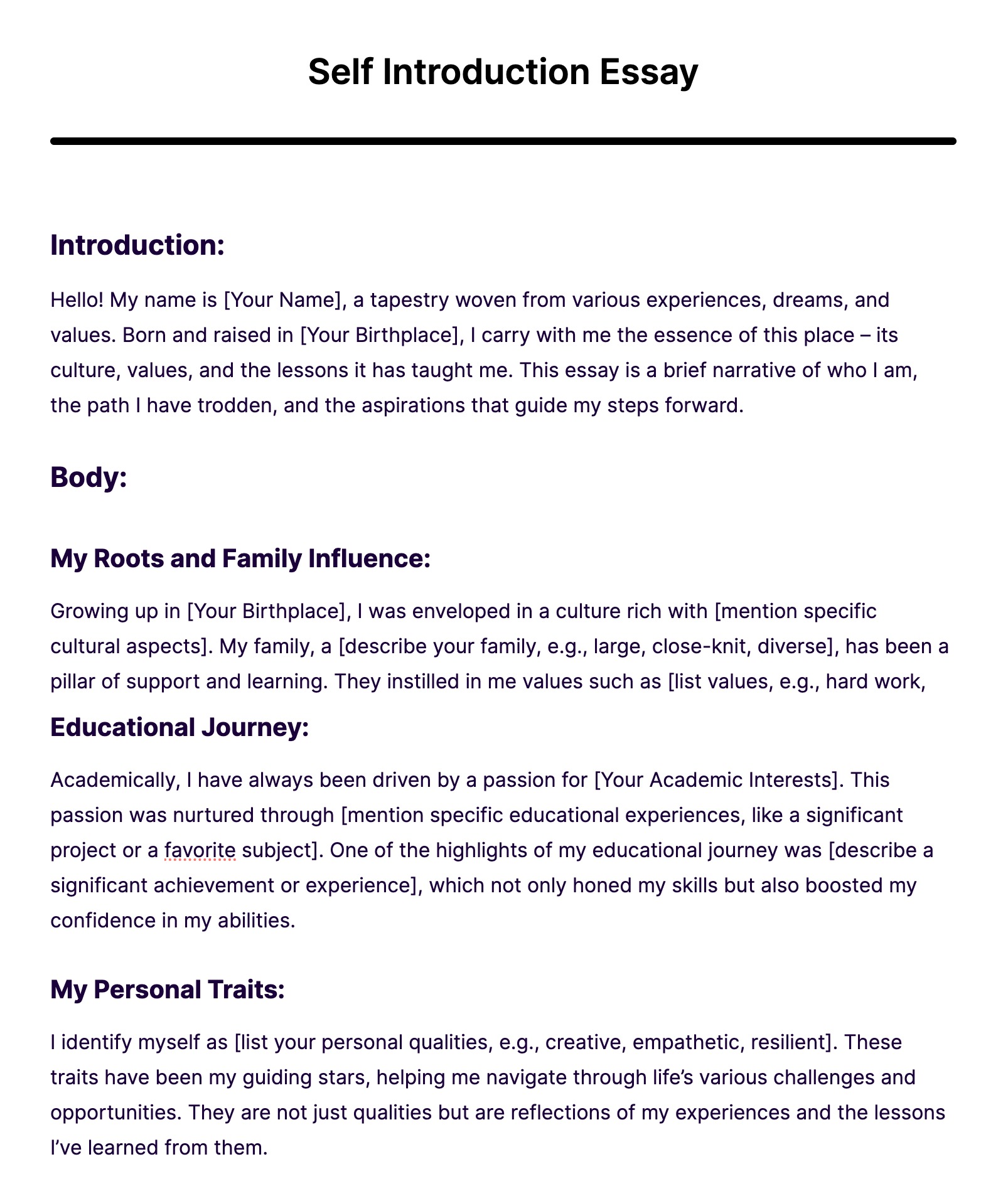

Self Introduction Essay Format

Introduction.

Start with a hook: Begin with an interesting fact, a question, or a compelling statement about yourself to grab the reader’s attention. State your name and a brief background: Share your name, age, and where you’re from or what you currently do (student, job role).

Educational Background

Discuss your current or most recent educational experience: Mention your school, college, or university and your major or area of study. Highlight academic achievements or interests: Share any honors, awards, or special projects that are relevant to your personality or career goals.

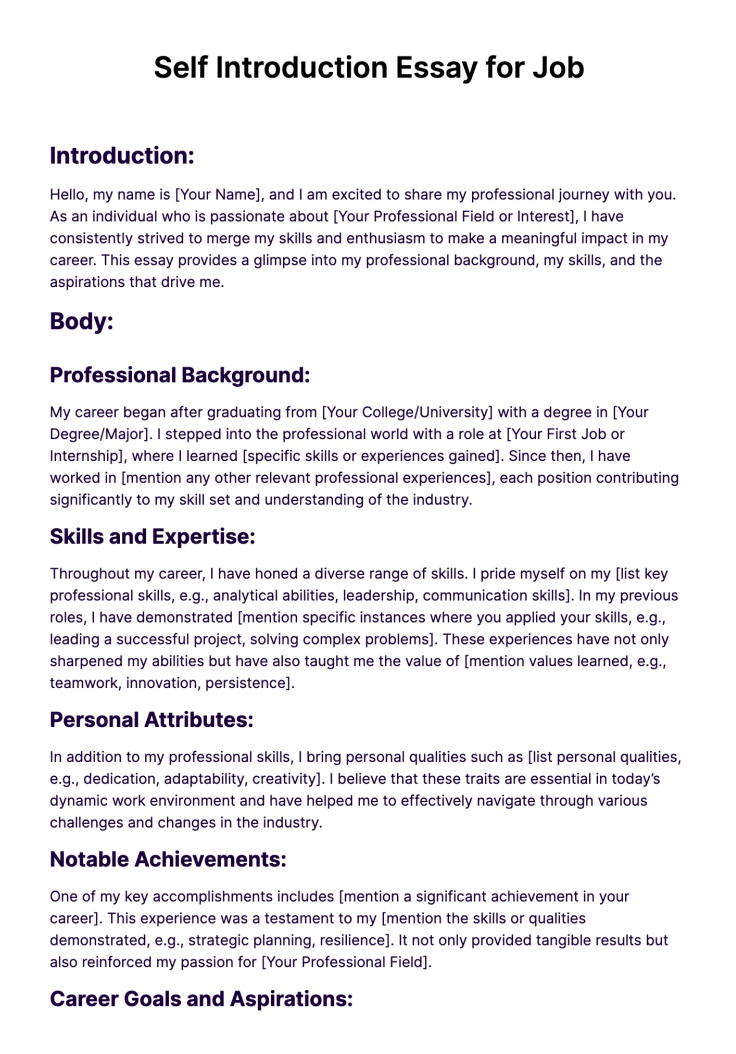

Professional Background

Mention your current job or professional experiences: Briefly describe your role, company, or the type of work you do. Highlight relevant skills or achievements: Share experiences that showcase your abilities and contributions to your field.

Personal Interests and Goals

Share your hobbies or interests: Briefly describe activities you enjoy or passions you pursue outside of work or school. Discuss your short-term and long-term goals: Explain what you aim to achieve in the near future and your aspirations for the long term.

Summarize your strengths and what makes you unique: Reinforce key points about your skills, achievements, or character. Close with a statement on what you hope to achieve or contribute in your next role, educational pursuit, or personal endeavor.

Example of Self Introduction Essay in English

Hello! My name is Alex Johnson, a 21-year-old Environmental Science major at Green Valley University, passionate about sustainable living and conservation efforts. Raised in the bustling city of New York, I’ve always been fascinated by the contrast between urban life and the natural world, driving me to explore how cities can become more sustainable. Currently, in my final year at Green Valley University, I’ve dedicated my academic career to understanding the complexities of environmental science. My coursework has included in-depth studies on renewable energy sources, water conservation techniques, and sustainable agriculture. I’ve achieved Dean’s List status for three consecutive years and led a successful campus-wide recycling initiative that reduced waste by 30%. This past summer, I interned with the City Planning Department of New York, focusing on green spaces in urban areas. I worked on a project that aimed to increase the city’s green coverage by 10% over the next five years. This hands-on experience taught me the importance of practical solutions in environmental conservation and sparked my interest in urban sustainability. Beyond academics, I’m an avid hiker and nature photographer, believing strongly in the power of visual storytelling to raise awareness about environmental issues. My goal is to merge my passion for environmental science with my love for photography to create impactful narratives that promote conservation. In the future, I aspire to work for an NGO that focuses on urban sustainability, contributing to projects that integrate green spaces into city planning. I am also considering further studies in environmental policy, hoping to influence positive change on a global scale. My journey from a curious city dweller to an aspiring environmental scientist has been driven by a deep passion for understanding and protecting our natural world. With a solid educational foundation and practical experience, I am eager to contribute to meaningful environmental conservation efforts. I believe that by combining scientific knowledge with creative communication, we can inspire a more sustainable future for urban areas around the globe.

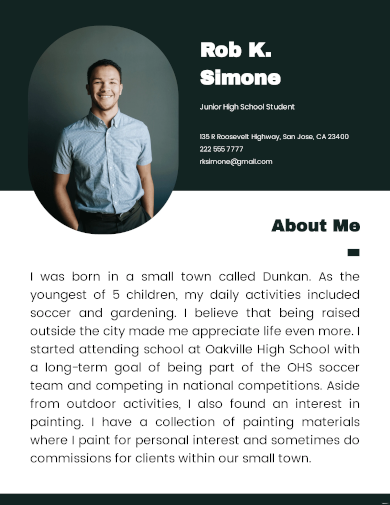

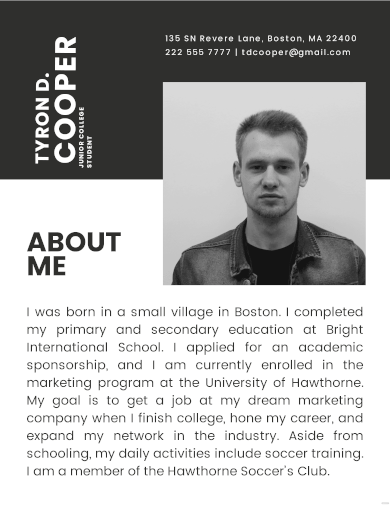

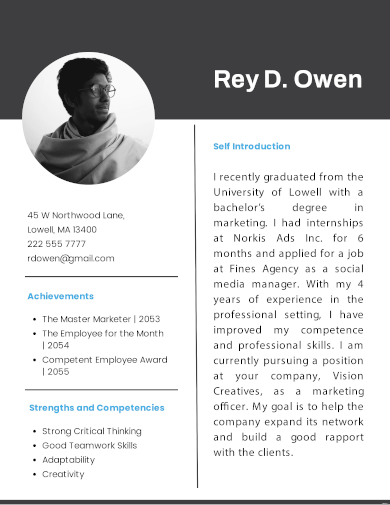

Self Introduction Essay for Job

Self Introduction Essay for Students

Self Introduction Essay Example

Size: 119 KB

Self Introduction For College Students Example

Size: MS Word

Simple Self Introduction For Job Example

Size: 88.4 KB

Free Self Introduction For Kids Example

Size: 123 KB

Simple Self Introduction Example

Size: 178 KB

Self Introduction For Freshers Example

Size: 96.2 KB

Free Self Introduction For Interview Example

Size: 129 KB

Company Self Introduction Example

Size: 125 KB

Self Introduction For First Day At Work Sample

Size: 124 KB

Sample Self Introduction for Scholarship Example

scholarshipsaz.org

Size: 33 KB

Free Self Introduction Sample Example

au-pair4you.at

Size: 22 KB

Creative Essay for Internship Example

wikileaks.org

What to Write in a Self-Introduction Essay

A self-introduction essay, as the name suggest, is an part of an essay containing the basic information about the writer.

In writing a self-introduction essay, the writer intends to introduce himself/herself by sharing a few personal information including the basics (e.g. name, age, hometown, etc.), his/her background information (e.g. family background, educational background, etc.), and interesting facts about him/her (e.g. hobbies, interests, etc). A self-introductory essay primarily aims to inform the readers about a few things regarding the writer. You may also see personal essay examples & samples

How to Write a Self-Introduction Essay

A self-introduction essay is, in most cases, written using the first-person point of view. As a writer, you simply need to talk about yourself and nothing more to a specific audience. You may also like essay writing examples

A self-introduction essay can be easy to write, since all you have to do is to introduce yourself. However, one needs to avoid sounding like a robot or a person speaking in monotone. Of course, you need to make the composition interesting and engaging, instead of making it plain and bland. This is probably the main challenge of writing a self-introduction essay, and the first thing every writer needs to be aware of.

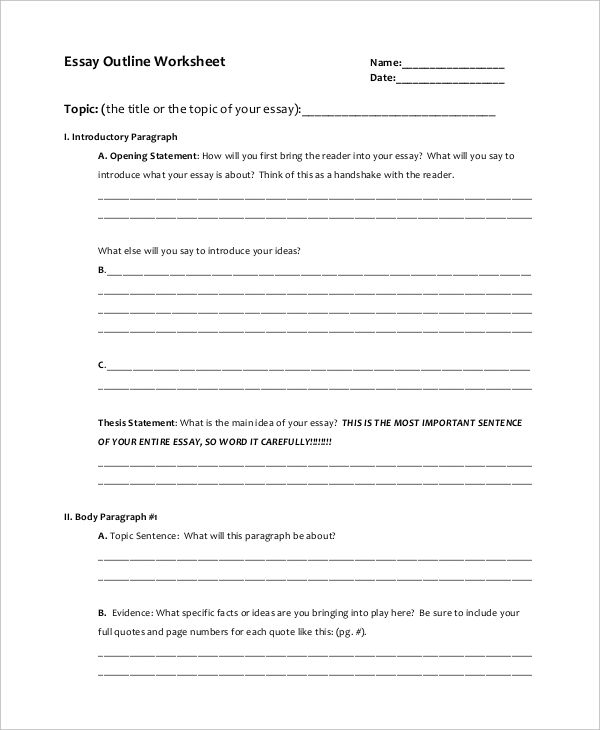

Free Essay Outline Worksheet Example

englishwithhallum.com

Size: 40 KB

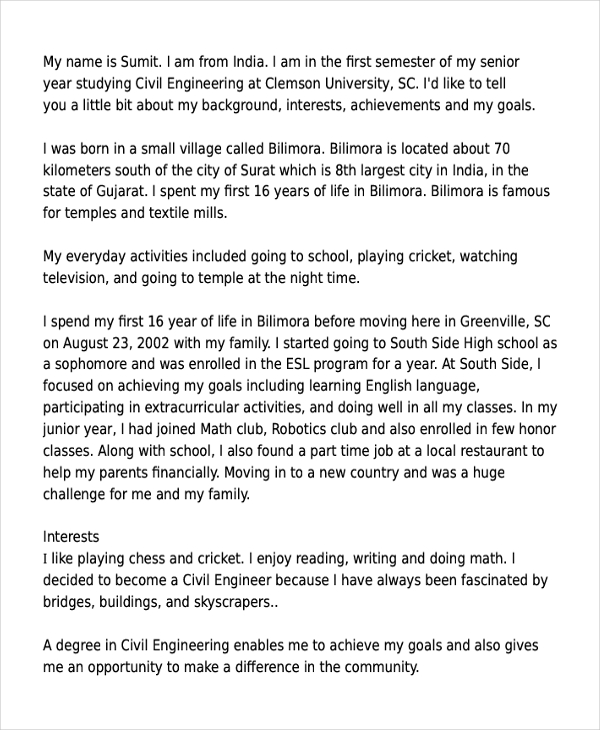

Free Interesting Self Introduction for Student Example

essayforum.com

Size: 14 KB

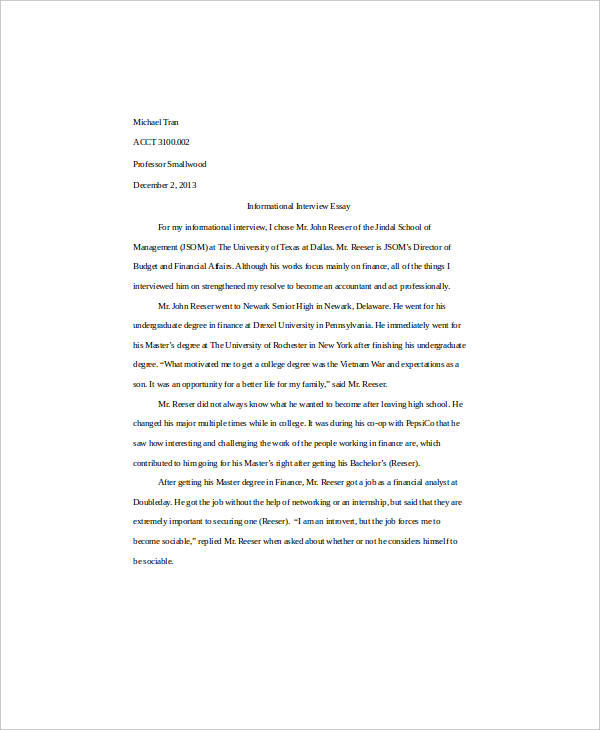

Free Attractive Introduction Essay for Interview Example

michaeltran27.weebly.com

Size: 17 KB

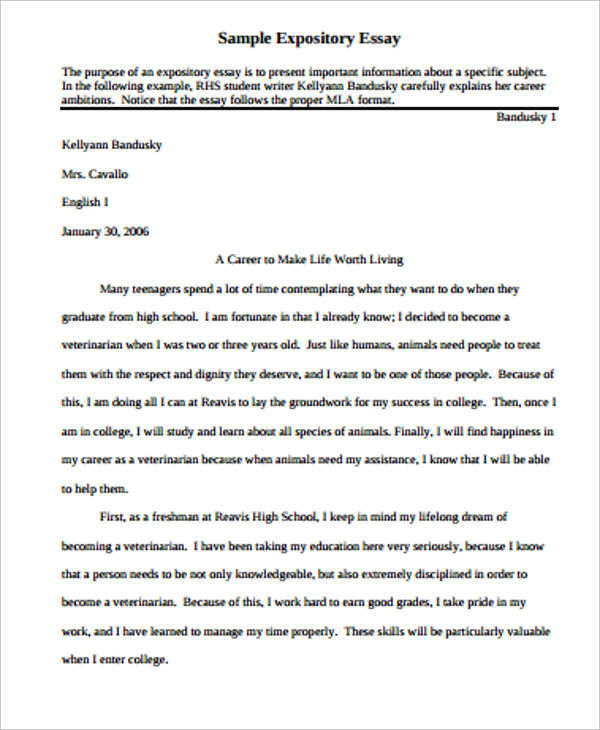

Formal Self Introduction Expository Example

teacherweb.com

Uses of Self Introduction Essay

- College Applications : Many universities and colleges ask for a self-introduction essay as part of the application process. This essay allows admissions officers to learn more about your personality, background, and aspirations beyond your grades and test scores.

- Scholarship Applications : When applying for scholarships, a self-introduction essay can help you stand out. It’s an opportunity to share your achievements, experiences, and the reasons you deserve the scholarship.

- Job Interviews : Preparing a self-introduction essay can be useful for job interviews. It helps you articulate your professional background, skills, and career goals clearly and confidently.

- Networking : In professional networking situations, having a polished self-introduction essay can help you quickly share relevant information about yourself with potential employers, mentors, or colleagues.

- Personal Reflection : Writing a self-introduction essay is a valuable exercise in self-reflection. It can help you understand your own goals, strengths, and weaknesses better.

- Online Profiles : For personal or professional websites, social media, or portfolios, a self-introduction essay provides a comprehensive overview of who you are and what you offer, attracting potential connections or opportunities.

Tips for Writing a Self-Introduction Essay

A self-introduction essay might be one of the easiest essays to start. However, one needs to learn a few things to make the composition worth reading. You might find a lot of tips online on how to write a self-introduction essay, but here are some tips which you might find useful.

1. Think of a catchy title

The first thing that attracts readers is an interesting title, so create one.

2. Introduce yourself

You can create some guide questions to answer like: Who are you? What are your interests? What is your story? Simply talk about yourself like you’re talking to someone you just met.

3. Find a focus

Your life story is too broad, so focus on something, like: What makes you unique?

4. Avoid writing plainly

For example, instead of saying: ‘I like listening to classical music’, you can say: ‘My dad gave me an album containing classical music when I was five, and after listening to it, I was really captivated. I’ve loved it since then.’ You may also check out high school essay examples & samples

5. Simplify your work

Use simple words and language. Write clearly. Describe details vividly.

6. End it with a punch

You cannot just plainly say ‘The End’ at the last part. Create a essay conclusion which would leave an impression to your readers.

7. Edit your work

After wrapping up, take time to review and improve your work. You may also see informative essay examples & samples

What is a Creative Self Introduction Essay?

1. Choose a Theme or Metaphor:

Start with a theme or metaphor that reflects your personality or the message you want to convey. For example, you could compare your life to a book, a journey, or a puzzle.

2. Engaging Hook:

Begin with an attention-grabbing hook, such as a captivating anecdote, a thought-provoking question, a quote, or a vivid description.

3. Tell a Story:

Weave your self-introduction into a narrative or story that highlights your experiences, values, or defining moments. Storytelling makes your essay relatable and memorable.

4. Use Vivid Imagery:

Employ descriptive language and vivid imagery to paint a picture of your life and character. Help the reader visualize your journey.

5. Show, Don’t Tell:

Instead of simply listing qualities or achievements, demonstrate them through your storytelling. Show your resilience, creativity, or determination through the narrative.

6. Include Personal Anecdotes:

Share personal anecdotes that showcase your character, challenges you’ve overcome, or moments of growth.

7. Express Your Passions:

Discuss your passions, interests, hobbies, or aspirations. Explain why they are important to you and how they have influenced your life.

8. Reveal Vulnerability:

Don’t be afraid to show vulnerability or share setbacks you’ve faced. It adds depth to your story and demonstrates your resilience.

9. Highlight Achievements:

Mention significant achievements, awards, or experiences that have shaped your journey. Connect them to your personal growth and values.

10. Convey Your Personality:

Use humor, wit, or elements of your personality to make your essay unique and relatable. Let your voice shine through.

11. Share Future Aspirations:

Discuss your goals, dreams, and what you hope to achieve in the future. Explain how your experiences have prepared you for your next steps.

12. Conclude with a Message:

Wrap up your essay with a meaningful message or reflection that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

13. Revise and Edit:

After writing your initial draft, revise and edit your essay for clarity, coherence, and conciseness. Ensure it flows smoothly.

How do you write an introduction to a self essay?

1. Start with a Hook:

Begin with an engaging hook to capture the reader’s attention. This could be a personal anecdote, a thought-provoking question, a quote, or a vivid description. The hook should relate to the essay’s theme.

2. Introduce Yourself:

After the hook, introduce yourself by stating your name and any relevant background information, such as your age, place of origin, or current location. This helps provide context.

3. Establish the Purpose:

Clearly state the purpose of your self-essay. Explain why you are writing it and what you aim to convey. Are you introducing yourself for a job application, a college admission essay, or a personal blog? Make this clear.

4. Provide a Preview:

Offer a brief preview of the main points or themes you will address in the essay. This helps set expectations for the reader and gives them an overview of what to anticipate.

5. Share Your Thesis or Central Message:

In some self-essays, especially in academic or personal development contexts, you may want to state a central message or thesis about yourself. This is the core idea you’ll explore throughout the essay.

6. Express Your Voice:

Let your unique voice and personality shine through in the introduction. Write in a way that reflects your style and character. Avoid using overly formal or stilted language if it doesn’t align with your personality.

7. Be Concise:

Keep the introduction relatively concise. It should provide an overview without delving too deeply into the details. Save the in-depth discussions for the body of the essay.

8. Revise and Edit:

After writing the introduction, review it for clarity, coherence, and conciseness. Make sure it flows smoothly and leads naturally into the main body of the essay.

Here’s an example of an introduction for a self-essay:

“Standing at the threshold of my college years, I’ve often found myself reflecting on the journey that brought me here. I am [Your Name], a [Your Age]-year-old [Your Origin or Current Location], with a passion for [Your Interests]. In this self-essay, I aim to share my experiences, values, and aspirations as I enter this new chapter of my life. Through personal anecdotes and reflections, I hope to convey the lessons I’ve learned and the person I’m becoming. My central message is that [Your Central Message or Thesis]. Join me as I explore the highs and lows of my journey and what it means to [Your Purpose or Theme].”

What is a short paragraph of self introduction

“Hello, my name is [Your Name], and I am [Your Age] years old. I grew up in [Your Hometown] and am currently studying [Your Major or Grade Level] at [Your School or University]. I have always been passionate about [Your Interests or Hobbies], and I love exploring new challenges and experiences. In my free time, I enjoy [Your Activities or Hobbies], and I’m excited to be here and share my journey with all of you.”

How do I start my self introduction?

1. Greet the Audience:

Start with a warm and friendly greeting. This sets a positive tone and makes you approachable.

Example: “Good morning/afternoon/evening!”

2. State Your Name:

Clearly and confidently state your name. This is the most basic and essential part of any self-introduction.

Example: “My name is [Your Name].”

3. Provide Additional Background Information:

Depending on the context, you may want to share additional background information. Mention where you are from, your current location, or your job title, if relevant.

Example: “I’m originally from [Your Hometown], but I currently live in [Your Current Location].”

4. Express Enthusiasm:

Express your enthusiasm or eagerness to be in the situation or context where you are introducing yourself.

Example: “I’m thrilled to be here today…”

5. State the Purpose:

Clearly state the purpose of your self-introduction. Are you introducing yourself for a job interview, a social gathering, or a specific event? Make it clear why you are introducing yourself.

Example: “…to interview for the [Job Title] position.”

6. Offer a Brief Teaser:

Give a brief teaser or hint about what you’ll be discussing. This can generate interest and set the stage for the rest of the introduction.

Example: “I’ll be sharing my experiences as a [Your Profession] and how my background aligns with the requirements of the role.”

7. Keep It Concise:

Keep your introduction concise, especially in professional settings. You can provide more details as the conversation progresses.

8. Be Confident and Maintain Eye Contact:

Deliver your introduction with confidence and maintain eye contact with the audience or the person you’re addressing.

How can I start my self introduction example?

Hi, I’m [Your Name]. It’s a pleasure to meet all of you. I come from [Your Hometown], and today, I’m excited to tell you a bit about myself. I have a background in [Your Education or Profession], and I’m here to share my experiences, skills, and passions. But before I dive into that, let me give you a glimpse into the person behind the resume. So, here’s a little about me…”

For more insights on crafting a compelling self-introduction, the University of Nevada, Reno’s Writing & Speaking Center provides valuable resources. These can enhance your essay-writing skills, especially in crafting introductions that make a lasting impression.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write a Self Introduction Essay that highlights your unique qualities.

Create a Self Introduction Essay outlining your academic interests.

Self Introduction For Kids Example

Self Introduction For Freshers Example

Self Introduction For Interview Example

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Life

Essay Samples on Myself

A message to myself: reflections, encouragement, and self-compassion.

Within the depths of our thoughts lies a space where we can have a heartfelt conversation with the most familiar person of all—ourselves. This message to myself encapsulates a journey of introspection, offering reflections, encouragement, and a reminder of the importance of self-compassion. In this...

Me, Myself, and I: The Triad of Identity in 500 Words

In the intricate mosaic of human existence, the triad of "Me, Myself, and I" forms the cornerstone of identity—a fusion of experiences, thoughts, emotions, and aspirations that intertwine to create a unique narrative. In this essay, we delve into the complex interplay of these three...

How I Learned to Love Myself

The odyssey of self-love is a deeply personal and transformative one—a journey that I embarked upon with uncertainty and emerged from with a profound sense of how I learned to love myself. In this essay, I delve into the layers of this voyage, exploring the...

Expectations for Myself as a Student

The journey through academia is a pursuit of growth, knowledge, and self-discovery. As I step into this realm, I am guided by expectations for myself as a student—goals that encompass not only academic achievements but also personal development and a commitment to lifelong learning. In...

Introducing Myself: Uniqueness Within and Self-Presentation

Stepping onto the stage of self-presentation, I embark on the journey of introducing myself—an endeavor that requires delicacy, authenticity, and an appreciation for the intricacies that define my identity. In this essay, I navigate the nuances of self-introduction, exploring the essence of who I am,...

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Knowing Myself: Unraveling the Self

The pursuit of knowing myself is an intricate voyage—a path that winds through the labyrinth of thoughts, emotions, and experiences that comprise the essence of who I am. In this introspective essay, I delve into the significance of self-awareness, the layers of identity, and the...

Understanding Myself: the Complexities of Self-Discovery

Embarking on the quest of understanding myself is an odyssey of introspection—a journey that delves into the intricacies of thoughts, emotions, and experiences that shape the unique tapestry of my identity. In this reflective essay, I delve into the significance of self-awareness, the layers of...

The Place I Can Be Myself: a Haven of Authenticity

Amid the bustling rhythms of life, there exists a sanctuary—a refuge where pretenses fade, and authenticity flourishes. In this introspective essay, I delve into the place I can be myself, reflecting on the significance of finding solace in an environment that embraces my true identity,...

Myself as a Writer: Crafting Words, Weaving Worlds

Embracing the identity of a writer is a journey of words and wonder—an odyssey that unfolds through the art of crafting narratives and evoking emotions. In this introspective essay, I delve into the essence of myself as a writer, reflecting on the power of storytelling,...

- Being a Writer

Myself as a Counselor: My Journey as a Compassionate Guide

Stepping into the role of a counselor is an embodiment of empathy, guidance, and a commitment to fostering mental well-being. In this introspective essay, I delve into the realm of myself as a counselor, reflecting on the qualities that define my approach, the significance of...

Discovering Myself: Inner Exploration

The journey of discovering myself is a profound odyssey—a quest that delves into the intricacies of identity, purpose, and the essence of being. In this introspective essay, I embark on an expedition through the inner landscape, unraveling the layers of my character, aspirations, and the...

How I Value Myself: Nurturing Self-Worth

At the core of a fulfilling and empowered life lies the practice of self-worth—a journey of recognizing, appreciating, and embracing one's intrinsic value. In this reflective essay, I embark on an exploration of how I value myself. From acknowledging my strengths to embracing my vulnerabilities,...

History of Myself: Chronicles of Identity and Transformation

The history of myself is a narrative that unfolds across time, encompassing a tapestry of experiences, emotions, growth, and transformation. In this reflective essay, I embark on a journey to trace the history of myself—from the origins that shaped my identity to the chapters of...

Being Myself: Embracing Authenticity and Finding Inner Harmony

In a world often shaped by expectations and comparisons, the journey of being myself emerges as an exploration of authenticity, self-acceptance, and the pursuit of inner harmony. In this reflective essay, I delve into the intricacies of embracing my true self—the challenges, revelations, and rewards...

Describing Myself: Narrative of Self-Discovery

Every individual is an intricate tapestry of stories, experiences, and emotions. In this narrative essay, I embark on a reflective journey to unveil the layers that compose the canvas of my identity. Through the art of storytelling, I delve into the myriad experiences that contribute...

How Do I Define Myself: Unraveling the Layers of My Identity

The essence of being human lies in the intricate tapestry of individuality that weaves together experiences, beliefs, aspirations, and values. In this introspective essay, I embark on a journey to explore the profound question of how do I define myself. From the colors that paint...

- Self Identity

A Letter to Myself: Life's Journey with Reflection and Wisdom

Life is a tapestry woven with moments of joy, challenges, growth, and self-discovery. In this introspective essay, I embark on a journey of a letter to myself. As the author and recipient of this heartfelt correspondence, I delve into the wisdom gained from experiences, the...

Where I See Myself in the Future

The journey of life is akin to an artist's canvas, awaiting the strokes of dreams, ambitions, and actions to paint a masterpiece of the future. In this essay, I embark on a reflective journey to explore where I see myself in the future. From the...

Where Do I See Myself in 5 Years

Life is a journey that unfolds with each passing day, offering us the opportunity to set our sights on the horizon and envision where our efforts will lead us. In this essay, we embark on a voyage of introspection to explore the question: Where do...

Mapping the Future: Where Do I See Myself in 20 Years

Introduction Projecting oneself two decades into the future is a thought-provoking exercise that conjures up a mix of excitement and uncertainty. As I contemplate where I see myself in 20 years, I envision a life marked by personal and professional growth, a harmonious family life,...

- About Myself

Reflections: How Do I See Myself as a Person

Introduction Self-perception is a complex, multifaceted topic, and can be influenced by many factors including our upbringing, our experiences, and our relationships. In this essay, I will explore the topic of self-perception, delving into the various aspects of how I see myself as a person,...

The Person I Am Today: A Reflection on My Experiences and Beliefs

Humans are the most superior creatures amid all the creatures in the entire universe. Being a part of this universe makes me feel small and minuscule in a world where there millions of humans like myself. Although everyone is quite unique in their own way....

- Personality

How I Freed Myself From Diabetes: Strategies and Action Plan

Diabetes has become a nightmare for diabetic patients. This menace is making its roots strong in todays world. This disease has been taking colossal amount of national health budget. With the passage of time the number of diabetics are increasing. According to a report, an...

- Believe in Myself

What Does It Mean to Be Successful: a Change in My Mindset

Can you ever call yourself if you don't have desires to obtain and work for it? And can you even call your self as profitable sitting without problems in your residing room except doing anything? These mindset make a character pick between being failure and...

- Personal Strengths

Discovering My True Self: Embracing Confidence, Self-Belief, and Personal Growth

Before I understand myself, I started believing in myself. I started to think clearly and analyze what's my purpose in this world then I took the risk to study harder to achieve my dreams. I move forward and think positive so that I can concentrate...

Best topics on Myself

1. A Message to Myself: Reflections, Encouragement, and Self-Compassion

2. Me, Myself, and I: The Triad of Identity in 500 Words

3. How I Learned to Love Myself

4. Expectations for Myself as a Student

5. Introducing Myself: Uniqueness Within and Self-Presentation

6. Knowing Myself: Unraveling the Self

7. Understanding Myself: the Complexities of Self-Discovery

8. The Place I Can Be Myself: a Haven of Authenticity

9. Myself as a Writer: Crafting Words, Weaving Worlds

10. Myself as a Counselor: My Journey as a Compassionate Guide

11. Discovering Myself: Inner Exploration

12. How I Value Myself: Nurturing Self-Worth

13. History of Myself: Chronicles of Identity and Transformation

14. Being Myself: Embracing Authenticity and Finding Inner Harmony

15. Describing Myself: Narrative of Self-Discovery

- Career Goals

- Perseverance

- Driving Age

- Credit Card

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Myself: 100 Words, 250 Words and 300 Words

- Updated on

- Mar 12, 2024

We are all different from each other and it is important to self-analyze and know about yourself. Only you can know everything about yourself. But, when it comes to describing yourself in front of others many students fail to do so. This happens due to the confusion generated by a student’s mind regarding what things to include in their description. This confusion never arises when someone is told to give any opinion about others. This blog will help students and children resolve the confusion and it also includes an essay on myself.

While writing an “essay on myself” you should have a unique style so that the reader would engage in your essay. It’s important to induce the urge to know about you in the reader then only you can perform well in your class. I would suggest you include your qualities, strengths, achievements, interests, and passion in your essay. Continue Reading for Essays on myself for children and students!

Quick Read: Essay on Child Labour

Table of Contents

- 1 Long and Short Essay on Myself for Students

- 2 Tips to Write Essay on Myself

- 3 100 Words Essay on Myself

- 4 250 Words Essay on Myself

- 5 10 Lines on Myself Essay for Children

- 6 300 Words Essay on Myself

Quick Read: Trees are Our Best Friend Essay

Long and Short Essay on Myself for Students

Mentioned below are essays on myself with variable word limits. You can choose the essay that you want to present in your class. These essays are drafted in simple language so that school students can easily understand. In addition, the main point to remember while writing an essay on myself is to be honest. Your honesty will help you connect with the reader.

Tell me about yourself is also one of the most important questions asked in the interview process. Therefore, this blog is very helpful for people who want to learn about how to write an essay on myself.

Tips to Write Essay on Myself

Given below are some tips to write an essay on myself:

- Prepare a basic outline of what to include in the essay about yourself.

- Stick to the structure to maintain fluency.

- Be honest to build a connection with the reader.

- Use simple language.

- Try to include a crisp and clear conclusion.

Quick Read: Speech on No Tobacco Day

100 Words Essay on Myself

I am a dedicated person with an urge to learn and grow. My name is Rakul, and I feel life is a journey that leads to self-discovery. I belong to a middle-class family, my father is a handloom businessman, and my mother is a primary school teacher .

I have learned punctuality and discipline are the two wheels that drive our life on a positive path. My mother is my role model. I am passionate about reading novels. When I was younger, my grandmother used to narrate stories about her life in the past and that has built my interest towards reading stories and novels related to history.

Overall I am an optimistic person who looks forward to life as a subject that teaches us values and ways to live for the upliftment of society.

Also Read: Speech on Discipline

250 Words Essay on Myself

My name is Ayushi Singh but my mother calls me “Ayu”. I turned 12 years old this August and I study in class 7th. I have an elder sister named Aishwarya. She is like a second mother to me. I have a group of friends at school and out of them Manvi is my best friend. She visits my house at weekends and we play outdoor games together. I believe in her and I can share anything with her.

Science and technology fascinate me so I took part in an interschool science competition in which my team of 4 girls worked on a 3-D model of the earth representing past, present, and future. It took us a week to finish off the project and we presented the model at Ghaziabad school. We were competing against 30 teams and we won the competition.

I was confident and determined about the fact that we could win because my passion helped me give my 100% input in the task. Though I have skills in certain subjects I don’t have to excel in everything, I struggle to perform well in mathematics . And to enhance my problem-solving skills I used to study maths 2 hours a day.

I wanted to become a scientist, and being punctual and attentive are my characteristics as I never arrive late for school. Generally, I do my work on my own so that I inculcate the value of being an independent person. I always help other people when they are in difficult situations.

Also Read: Essay on the Importance of the Internet

10 Lines on Myself Essay for Children

Here are 10 lines on myself essay for children. Feel free to add them to similar essay topics.

- My name is Ananya Rathor and I am 10 years old.

- I like painting and playing with my dog, Todo.

- Reading animal books is one of my favourite activities.

- I love drawing and colouring to express my imagination.

- I always find joy in spending time outdoors, feeling the breeze on my face.

- I love dancing to Indian classical music.

- I’m always ready for an adventure, whether it’s trying a new hobby or discovering interesting facts.

- Animals are my friends, and I enjoy spending time with pets or observing nature’s creatures.

- I am a very kind person and I respect everyone.

- All of my school teachers love me.

300 Words Essay on Myself

My name is Rakul. I believe that every individual has unique characteristics which distinguish them from others. To be unique you must have an extraordinary spark or skill. I live with my family and my family members taught me to live together, adjust, help others, and be humble. Apart from this, I am an energetic person who loves to play badminton.

I have recently joined Kathak classes because I have an inclination towards dance and music, especially folk dance and classical music. I believe that owing to the diversity of our country India, it offers us a lot of opportunities to learn and gain expertise in various sectors.

My great-grandfather was a classical singer and he also used to play several musical instruments. His achievements and stories have inspired me to learn more about Indian culture and make him proud.

I am a punctual and studious person because I believe that education is the key to success. Academic excellence could make our careers shine bright. Recently I secured second position in my class and my teachers and family members were so proud of my achievement.

I can manage my time because my mother taught me that time waits for no one. It is important to make correct use of time to succeed in life. If we value time, then only time will value us. My ambition in life is to become a successful gynaecologist and serve for human society.

Hence, these are the qualities that describe me the best. Though no one can present themselves in a few words still I tried to give a brief about myself through this essay. In my opinion, life is meant to be lived with utmost happiness and an aim to serve humanity. Thus, keep this in mind, I will always try to help others and be the best version of myself.

Also Read: Essay on Education System

A. Brainstorm Create a format Stick to the format Be vulnerable Be honest Figure out what things to include Incorporate your strengths, achievements, and future goals into the essay

A. In an essay, you can use words like determined, hardworking, punctual, sincere, and objective-oriented to describe yourself in words.

A. Use simple and easy language. Include things about your family, career, education, and future goals. Lastly, add a conclusion paragraph.

This was all about an essay on myself. The skill of writing an essay comes in handy when appearing for standardized language tests. Thinking of taking one soon? Leverage Live provides the best online test prep for the same. Register today and if you wish to study abroad then contact our experts at 1800572000 .

Kajal Thareja

Hi, I am Kajal, a pharmacy graduate, currently pursuing management and is an experienced content writer. I have 2-years of writing experience in Ed-tech (digital marketing) company. I am passionate towards writing blogs and am on the path of discovering true potential professionally in the field of content marketing. I am engaged in writing creative content for students which is simple yet creative and engaging and leaves an impact on the reader's mind.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

it’s an perfect link for students

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Essay Papers Writing Online

Learn the best tips and techniques for crafting a compelling and engaging essay about myself.

When it comes to talking about oneself, it can be quite a challenge to find the right words to express our thoughts and emotions. Writing an essay about oneself is an opportunity to not only showcase our personality, but also our experiences and achievements. It allows us to reflect on our journey and share our unique perspective with the world. Crafting an essay about oneself requires careful consideration of the words we choose and how we structure our thoughts. In this guide, we will explore effective tips and strategies to help you write an exceptional essay that truly captures who you are.

Understanding yourself is the first step. Before diving into writing, take some time to reflect on your experiences, values, and beliefs. Consider the moments that have shaped you and the lessons you have learned along the way. Think about your passions, strengths, and weaknesses. Understanding yourself will help you create a more authentic and compelling essay. Don’t be afraid to dig deep and explore your innermost thoughts and feelings. This self-reflection process will provide a solid foundation for your essay.

Show, don’t tell. Instead of simply listing your accomplishments or personality traits, strive to illustrate them through vivid anecdotes and specific details. This will make your essay more engaging and memorable. Use descriptive language and paint a picture for your readers. For example, if you want to showcase your leadership skills, don’t just say, “I am a great leader.” Instead, share a story of how you organized and successfully led a team to accomplish a challenging task. By providing concrete examples, you will leave a lasting impression on your readers.

Tactics for Crafting a Personal Account: Step-by-Step Manual

Constructing a narrative about oneself can often present a challenge. In order to produce an effective personal essay, it is crucial to employ certain strategies that lend authenticity and engage the reader. This section will outline a step-by-step guide for writing a compelling essay that highlights personal experiences and insights.

Use Personal Anecdotes and Examples

When crafting an essay about yourself, it is important to make it engaging and relatable to your audience. One effective way to achieve this is by using personal anecdotes and examples. These storytelling elements can bring your essay to life and make it more memorable.

Instead of just stating facts about yourself, try incorporating specific instances or events from your life that illustrate your qualities, experiences, or perspectives. For example, if you are writing about your leadership skills, you can share an anecdote about a time when you successfully led a group project or organized a community event.

Personal anecdotes not only add depth and authenticity to your essay, but they also help to showcase your unique personality and differentiate you from other applicants. They provide concrete evidence of your abilities, allowing the reader to form a better understanding of who you are as an individual.

Furthermore, using examples is an effective way to support your claims and arguments. Whether you are discussing your academic achievements, personal growth, or career goals, providing specific examples or evidence can strengthen your essay and make it more persuasive.

Remember to choose anecdotes and examples that are relevant to the points you are trying to make in your essay. They should effectively support your main ideas and contribute to the overall coherence of your piece.

In conclusion, incorporating personal anecdotes and examples in your essay can make it more engaging, relatable, and persuasive. By sharing specific instances from your life, you not only showcase your unique qualities and experiences, but also provide evidence to support your claims. So, don’t be afraid to share your personal stories and experiences – they can make your essay truly standout.

Highlight Your Achievements and Accomplishments

When it comes to writing an essay about oneself, it is essential to showcase your achievements and accomplishments. This section allows you to underscore your skills, experiences, and noteworthy moments in your personal and professional life. By highlighting your accomplishments, you not only demonstrate your abilities but also provide evidence of your dedication, hard work, and commitment to success.

Begin by reflecting on your accomplishments in various areas of your life. Look beyond the obvious academic or professional achievements and consider personal milestones, volunteer work, leadership roles, or any significant challenges you have overcome. These accomplishments can range from winning a sports competition to completing a project successfully or receiving recognition for your contributions.

When describing your achievements, aim to be specific and provide relevant details. For instance, instead of simply stating that you won an award, elaborate on the specific award, including the criteria, the competition or event, and possibly how you felt when you received it. This level of detail helps the reader get a clear sense of your accomplishment and its significance.

Moreover, don’t shy away from discussing challenges you have faced during your journey to highlight your accomplishments. Sharing the obstacles you have overcome demonstrates resilience, determination, and the ability to adapt and grow.

In addition to showcasing your accomplishments, it is pivotal to connect them to your personal and professional goals . Highlight how these achievements have shaped you as an individual and how they relate to your aspirations. Discuss how each accomplishment has contributed to your growth, development, and the acquisition of specific skills or qualities that are relevant to your essay’s overall theme or purpose.

Remember, while it is important to present your achievements, do so humbly and avoid sounding boastful. Instead, focus on conveying your passion, the lessons you have learned, and the positive impact these accomplishments have had on your life.

By highlighting your achievements and accomplishments, you will showcase your abilities, experiences, and the unique qualities that make you stand out. This section allows you to provide a well-rounded view of yourself while demonstrating your potential for future success.

Discuss Your Goals and Aspirations

When writing an essay about yourself, it is important to discuss your goals and aspirations. This section allows you to express your hopes and dreams for the future, showcasing your ambition and drive. By sharing your goals, you provide insight into your motivations and what you hope to achieve in life.

One way to discuss your goals is by highlighting specific career aspirations. You can mention the profession or field you aim to pursue and explain why it is meaningful to you. Perhaps you have always had a passion for science and hope to become a research scientist, or maybe you dream of being a lawyer and fighting for justice. By discussing your career goals, you demonstrate your focus and determination.

Furthermore, it is important to discuss personal goals unrelated to your career. These could include aspirations in areas such as personal growth, relationships, and health. For example, you may have a goal to become a better communicator, to build stronger relationships with loved ones, or to prioritize self-care and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Sharing these goals provides a well-rounded picture of who you are and what you value in life.

In addition to discussing your goals, it is beneficial to explain the reasons behind them. What has influenced or inspired you to set these aspirations? Did a personal experience or role model shape your goals? By providing context, you give your readers a deeper understanding of your motivations and what drives you to pursue these aspirations.

In conclusion, discussing your goals and aspirations in your essay about yourself allows you to showcase your ambition, drive, and motivations. By discussing both career and personal goals, you provide a well-rounded perspective of who you are and what you hope to achieve in life.

Be Honest and Authentic in Your Writing

When it comes to writing about yourself, it is important to be truthful and genuine in your words. Being honest allows you to connect with your readers on a deeper level and creates a sense of authenticity in your writing.

Authenticity in writing means presenting your true self and conveying your thoughts and experiences sincerely. It involves revealing your strengths, weaknesses, successes, and failures without any embellishment or exaggeration. Your readers will appreciate your genuine approach and will be able to relate to you on a personal level.

Being honest in your writing also means being true to yourself. Don’t try to mold your story or experiences to fit a specific narrative or expectation. Instead, embrace your uniqueness, quirks, and individuality. Your personal voice and perspective are what make your essay stand out and resonate with your readers.

In addition to being honest, it is important to be mindful of the tone and language you use in your writing. Be respectful and tactful when discussing sensitive or challenging topics. Maintain a balance between vulnerability and professionalism to ensure your message is conveyed effectively.

Remember, the purpose of writing about yourself is to share your story and experiences, not to impress or gain approval from others. Stay true to yourself and allow your authenticity to shine through your words. By being honest and authentic in your writing, you will not only create a meaningful essay, but also connect with your readers on a deeper level.

Be truthful, genuine, and authentic in your writing, and your essay about yourself will be compelling and impactful.

Revise and Edit Your Essay for Clarity and Coherence

Once you have completed the initial draft of your essay, it is important to carefully revise and edit it to ensure clarity and coherence. Revising and editing involves carefully reviewing your essay for any errors or areas of confusion, and making necessary changes to improve the overall flow and organization of your ideas.

One important aspect of revising and editing is to ensure that your essay is clear and easy to understand. This involves checking for grammar and spelling errors, as well as refining your sentence structure and word choice. By using clear and concise language, you can ensure that your ideas are communicated effectively to your reader.

In addition to clarity, coherence is another key element to consider when revising and editing your essay. Coherence refers to the logical and smooth flow of ideas within your essay. To achieve coherence, you should ensure that your paragraphs are well-organized and that each paragraph links to the next in a logical manner. Transitions and topic sentences can help to achieve this, providing a clear connection between ideas and guiding your reader through your essay.

When revising and editing, it can also be helpful to read your essay out loud. This can help you to identify any awkward or confusing sentences, as well as to check the overall rhythm and flow of your writing. Pay attention to any areas that seem disjointed or difficult to follow, and make changes to improve the overall coherence of your essay.

Finally, it is important to take the time to review and polish your essay before submitting the final version. This involves checking for any remaining errors, refining your language and style, and ensuring that your essay is well-structured and organized. By thoroughly revising and editing your essay, you can ensure that your ideas are presented clearly and coherently, leaving a strong impression on your reader.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

10 Personal Statement Essay Examples That Worked

What’s covered:, what is a personal statement.

- Essay 1: Summer Program

- Essay 2: Being Bangladeshi-American

- Essay 3: Why Medicine

- Essay 4: Love of Writing

- Essay 5: Starting a Fire

- Essay 6: Dedicating a Track

- Essay 7: Body Image and Eating Disorders

- Essay 8: Becoming a Coach

- Essay 9: Eritrea

- Essay 10: Journaling

- Is Your Personal Statement Strong Enough?

Your personal statement is any essay that you must write for your main application, such as the Common App Essay , University of California Essays , or Coalition Application Essay . This type of essay focuses on your unique experiences, ideas, or beliefs that may not be discussed throughout the rest of your application. This essay should be an opportunity for the admissions officers to get to know you better and give them a glimpse into who you really are.

In this post, we will share 10 different personal statements that were all written by real students. We will also provide commentary on what each essay did well and where there is room for improvement, so you can make your personal statement as strong as possible!

Please note: Looking at examples of real essays students have submitted to colleges can be very beneficial to get inspiration for your essays. You should never copy or plagiarize from these examples when writing your own essays. Colleges can tell when an essay isn’t genuine and will not view students favorably if they plagiarized.

Personal Statement Examples

Essay example #1: exchange program.

The twisting roads, ornate mosaics, and fragrant scent of freshly ground spices had been so foreign at first. Now in my fifth week of the SNYI-L summer exchange program in Morocco, I felt more comfortable in the city. With a bag full of pastries from the market, I navigated to a bus stop, paid the fare, and began the trip back to my host family’s house. It was hard to believe that only a few years earlier my mom was worried about letting me travel around my home city on my own, let alone a place that I had only lived in for a few weeks. While I had been on a journey towards self-sufficiency and independence for a few years now, it was Morocco that pushed me to become the confident, self-reflective person that I am today.

As a child, my parents pressured me to achieve perfect grades, master my swim strokes, and discover interesting hobbies like playing the oboe and learning to pick locks. I felt compelled to live my life according to their wishes. Of course, this pressure was not a wholly negative factor in my life –– you might even call it support. However, the constant presence of my parents’ hopes for me overcame my own sense of desire and led me to become quite dependent on them. I pushed myself to get straight A’s, complied with years of oboe lessons, and dutifully attended hours of swim practice after school. Despite all these achievements, I felt like I had no sense of self beyond my drive for success. I had always been expected to succeed on the path they had defined. However, this path was interrupted seven years after my parents’ divorce when my dad moved across the country to Oregon.

I missed my dad’s close presence, but I loved my new sense of freedom. My parents’ separation allowed me the space to explore my own strengths and interests as each of them became individually busier. As early as middle school, I was riding the light rail train by myself, reading maps to get myself home, and applying to special academic programs without urging from my parents. Even as I took more initiatives on my own, my parents both continued to see me as somewhat immature. All of that changed three years ago, when I applied and was accepted to the SNYI-L summer exchange program in Morocco. I would be studying Arabic and learning my way around the city of Marrakesh. Although I think my parents were a little surprised when I told them my news, the addition of a fully-funded scholarship convinced them to let me go.

I lived with a host family in Marrakesh and learned that they, too, had high expectations for me. I didn’t know a word of Arabic, and although my host parents and one brother spoke good English, they knew I was there to learn. If I messed up, they patiently corrected me but refused to let me fall into the easy pattern of speaking English just as I did at home. Just as I had when I was younger, I felt pressured and stressed about meeting their expectations. However, one day, as I strolled through the bustling market square after successfully bargaining with one of the street vendors, I realized my mistake. My host family wasn’t being unfair by making me fumble through Arabic. I had applied for this trip, and I had committed to the intensive language study. My host family’s rules about speaking Arabic at home had not been to fulfill their expectations for me, but to help me fulfill my expectations for myself. Similarly, the pressure my parents had put on me as a child had come out of love and their hopes for me, not out of a desire to crush my individuality.

As my bus drove through the still-bustling market square and past the medieval Ben-Youssef madrasa, I realized that becoming independent was a process, not an event. I thought that my parents’ separation when I was ten had been the one experience that would transform me into a self-motivated and autonomous person. It did, but that didn’t mean that I didn’t still have room to grow. Now, although I am even more self-sufficient than I was three years ago, I try to approach every experience with the expectation that it will change me. It’s still difficult, but I understand that just because growth can be uncomfortable doesn’t mean it’s not important.

What the Essay Did Well

This is a nice essay because it delves into particular character trait of the student and how it has been shaped and matured over time. Although it doesn’t focus the essay around a specific anecdote, the essay is still successful because it is centered around this student’s independence. This is a nice approach for a personal statement: highlight a particular trait of yours and explore how it has grown with you.

The ideas in this essay are universal to growing up—living up to parents’ expectations, yearning for freedom, and coming to terms with reality—but it feels unique to the student because of the inclusion of details specific to them. Including their oboe lessons, the experience of riding the light rail by themselves, and the negotiations with a street vendor helps show the reader what these common tropes of growing up looked like for them personally.

Another strength of the essay is the level of self-reflection included throughout the piece. Since there is no central anecdote tying everything together, an essay about a character trait is only successful when you deeply reflect on how you felt, where you made mistakes, and how that trait impacts your life. The author includes reflection in sentences like “ I felt like I had no sense of self beyond my drive for success, ” and “ I understand that just because growth can be uncomfortable doesn’t mean it’s not important. ” These sentences help us see how the student was impacted and what their point of view is.

What Could Be Improved

The largest change this essay would benefit from is to show not tell. The platitude you have heard a million times no doubt, but for good reason. This essay heavily relies on telling the reader what occurred, making us less engaged as the entire reading experience feels more passive. If the student had shown us what happens though, it keeps the reader tied to the action and makes them feel like they are there with the student, making it much more enjoyable to read.

For example, they tell us about the pressure to succeed their parents placed on them: “ I pushed myself to get straight A’s, complied with years of oboe lessons, and dutifully attended hours of swim practice after school.” They could have shown us what that pressure looked like with a sentence like this: “ My stomach turned somersaults as my rattling knee thumped against the desk before every test, scared to get anything less than a 95. For five years the painful squawk of the oboe only reminded me of my parents’ claps and whistles at my concerts. I mastered the butterfly, backstroke, and freestyle, fighting against the anchor of their expectations threatening to pull me down.”

If the student had gone through their essay and applied this exercise of bringing more detail and colorful language to sentences that tell the reader what happened, the essay would be really great.

Table of Contents

Essay Example #2: Being Bangladeshi-American

Life before was good: verdant forests, sumptuous curries, and a devoted family.

Then, my family abandoned our comfortable life in Bangladesh for a chance at the American dream in Los Angeles. Within our first year, my father was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. He lost his battle three weeks before my sixth birthday. Facing a new country without the steady presence of my father, we were vulnerable — prisoners of hardship in the land of the free. We resettled in the Bronx, in my uncle’s renovated basement. It was meant to be our refuge, but I felt more displaced than ever. Gone were the high-rise condos of West L.A.; instead, government projects towered over the neighborhood. Pedestrians no longer smiled and greeted me; the atmosphere was hostile, even toxic. Schoolkids were quick to pick on those they saw as weak or foreign, hurling harsh words I’d never heard before.

Meanwhile, my family began integrating into the local Bangladeshi community. I struggled to understand those who shared my heritage. Bangladeshi mothers stayed home while fathers drove cabs and sold fruit by the roadside — painful societal positions. Riding on crosstown buses or walking home from school, I began to internalize these disparities. During my fleeting encounters with affluent Upper East Siders, I saw kids my age with nannies, parents who wore suits to work, and luxurious apartments with spectacular views. Most took cabs to their destinations: cabs that Bangladeshis drove. I watched the mundane moments of their lives with longing, aching to plant myself in their shoes. Shame prickled down my spine. I distanced myself from my heritage, rejecting the traditional panjabis worn on Eid and refusing the torkari we ate for dinner every day.

As I grappled with my relationship with the Bangladeshi community, I turned my attention to helping my Bronx community by pursuing an internship with Assemblyman Luis Sepulveda. I handled desk work and took calls, spending the bulk of my time actively listening to the hardships constituents faced — everything from a veteran stripped of his benefits to a grandmother unable to support her bedridden grandchild.