Apartheid in South Africa Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

South Africa is one of the countries with rich and fascinating history in the world. It is regarded as the most developed state in Africa and among the last to have an elected black president towards the end of the 20 th century. Besides its rich history, the South African state has abundant natural resources, fertile farms and a wide range of minerals including gold.

The country is the world’s leading miner of diamonds and gold with several metal ores distributed around the country like platinum (Rosmarin & Rissik, 2004). South Africa experiences a mild climate that resembles that of San Francisco bay.

With its geographical location and development, South Africa is one of the most accessible African countries. All these factors contribute to South Africa’s global prominence, especially before and after the reign of its first black President, Nelson Mandela in 1994.

However, these alone do not add up to what the country’s history. In fact, South Africa’s history sounds incomplete without the mention of Apartheid, a system that significantly shaped and transformed the country in what it is today.

Without apartheid, many argue that South Africa would have probably been a different country with unique ideologies, politics and overall identity. In other words, apartheid greatly affected South Africa in all spheres of a country’s operation. From segregation to all forms of unfairness, apartheid system negatively affected South Africans and the entire country (Pfister, 2005).

On the other hand, some people argue that apartheid positively affected South Africa in countless ways. This essay gives a detailed coverage of the issue of apartheid in South Africa and its impact to the economy, politics and social life of South Africans.

To achieve this task, the analysis is divided into useful sections, which give concise and authentic information concerning the topic. Up to date sources were consulted in researching the topic to ensure that data and information used in describing the concept is up to date, from reputable and recommended authors.

Among important segments of the essay include but not limited to the literature review, history, background information and recommendations.

Research questions

In addressing the issue of Apartheid in South Africa, this essay intends to provide answers to the following questions:

- What was apartheid system?

- What are the factors that led to the apartheid system?

- What were the negative effects of the apartheid system?

- What were the positive effects of the apartheid system?

- Why was it necessary to end apartheid in South Africa?

Literature Review

Apartheid in South Africa is one of the topics which have received massive literature coverage even after the end of the regime. Most of the documented information describes life before 1994 and what transpired after Nelson Mandela took leadership as the first black African President of the state.

This segment, therefore, explores the concept concerning what authors, scholars and researchers have recorded in books, journals and on websites as expounded in the following analytical sections.

Apartheid in South Africa

Apartheid refers to a South African system that propagated racial discrimination imposed between 1948 and 1994 by National Party regimes. During this period of decades, the rights of the majority “blacks” were undermined as white minority settlers maintained their supremacy and rule through suppressive tactics.

Apartheid was primarily developed after the Second World War by the Broederbond and Afrikaner organizations and was extended to other parts of South West Africa, currently known as Namibia until it became an independent state four years before the end of apartheid.

According to Allen 2005, discrimination of black people in South Africa began long before apartheid was born during the colonial era. In his survey, Allen noted that apartheid was ratified after the general election which was held in 1948.

The new legislation that the governments adopted classified all South African inhabitants into four groups based on their racial identity (Allen, 2005). These groups were Asians, whites, natives and colored. This led to all manners of segregation that ensured complete distinction among these groups, achieved through forced displacement of the oppressed groups without necessarily thinking about their rights.

The practice continued throughout the period, reaching heightened moments when non-whites were deprived of political representation in 1970, the year when blacks were denied citizenship right causing them to become members of Bantustans who belonged to self-governing homes (Allen, 2005).

Besides residential removal and displacement, other forms of discrimination dominated in public institutions like education centers, hospitals and beaches among other places which were legally meant for everybody regardless of their skin color, gender or country of origin.

In rare cases where black accessed these services, they were provided with inferior options as compared to what whites received (Allen, 2005). As a result, there was significant violence witnessed across the country, accompanied by internal resistance from people who believed that they were being exploited and languishing in poverty at the expense of white minorities.

Consequently, the country suffered trade embargoes as other countries around the world distanced themselves from South African rule as a way of condemning it and raising their voices in support for those who were considered less human in their own country.

Overwhelmed by the desire for equality, South Africa witnessed countless uprisings and revolts, which were welcomed with imprisoning of political and human rights activists who were strongly opposed to the apartheid rule.

Banning of opposition politics was also adopted in order to suppress leaders who believed in justice for humanity (Edwards & Hecht, 2010). As violence escalated around the country, several state organizations responded by sponsoring violence and increasing the intensity of oppression.

The peak of apartheid opposition was in 1980s when attempts to amend apartheid legislation failed to calm black people forcing President Frederik Willem de Klerk to enter into negotiations with black leaders to end apartheid in 1990.

The culmination of the negotiations was in 1994 when a multi-racial and democratic election was held with Nelson Mandela of African National Congress emerging the winner and the first black president in South Africa (Edwards & Hecht, 2010). Although apartheid ended more than a decade ago, it is important to note its impact and ruins are still evident in South Africa.

Background Information

Segregation took shape in the Union of South Africa in order to suppress the black people’s participation in politics and economic life. White rulers believed that the only way of maintaining their rule was to ensure that black people do not have opportunities to organize themselves into groups that would augment their ability to systematize themselves and fight back for their rights.

However, despite these efforts, black people in South Africa became integrated into the economic and industrial society than any other group of people in Africa during the 20 th century (Edwards & Hecht, 2010).

Clerics, educations and other professionals grew up to be key players as the influence of blacks sprouted with Mission Christianity significantly influencing the political landscape of the union. Studying in abroad also played a major role as blacks gained the momentum to fight for their rights as the move received support from other parts of the world (Burger, 2011).

There were continuous attempts from the government to control and manipulate black people through skewed policies, which were aimed at benefiting whites at the expense of the majority. The year 1902 saw the formation of the first political organization by Dr Abdurrahman which was mainly based in Cape Province.

However, the formation of the African National Congress in 1912 was a milestone as it brought together traditional authorities, educationists and Christian leaders (Burger, 2011). Its initial concern was defined by constitutional protests as its leaders demanded recognition and representation of the blacks.

Efforts by union workers to form organizations for the purpose of voicing their concerns were short-lived as their efforts were short down by white authorities. This led to strikes and militancy, which was experienced throughout 1920s. The formation of the Communist Party proved to be a force to last as it united workers’ organizations and non-racialism individuals (Beinart & Dubow, 1995).

Segregation of blacks was also witnessed in job regulations as skilled job opportunities remained reserved for white people. The introduction of pass-laws further aimed at restricting African mobility thus limiting their chances of getting organized.

These laws were also designed to have all blacks participate in forced labor as they did not have a clear channel to air their views. According to historic findings, all these efforts were inclined towards laying the foundation for apartheid in later years.

Noteworthy, there were divisions among whites as they differed with regard to certain ideologies and stances. For instance, they could not agree on their involvement in First World War I as the National Party dislodged from the South African Party (Beinart & Dubow, 1995). Conversely, allocation of skilled jobs to whites targeted high productivity from people who had experience while pass-laws prevented aimless movement.

Labor issues continued to emerge through organized strikes though these efforts were constantly thwarted by the government using brutal and inhumane ways like seclusion of migrant residential houses using compounds.

Miners also protested against low payment and poor living standards, conditions which promoted hostility between black and white labor forces, culminating into a bloody rebellion in 1922 (Beinart & Dubow, 1995).

Intensified discrimination against blacks mounted to serve the interests of white rulers through reinforcement of the unfair government policies and employment bar in certain areas like the railway and postal service to address the infamous “poor-white problem”.

The world depression of early 1930s led to the union of major white parties which was closely followed by the breakaway by a new Afrikaner led by Dr. DF Malan. The entrenchment of the white domination led to the elimination of Africans from the voters’ role in 1936 (Burger, 2011).

These continued up to the end of the Second World War when the government intensified segregation rules in 1948 that led to the conception and birth of Apartheid in South Africa.

Desmond Tutu against Apartheid

As mentioned above, Mission Christianity played a major role in the fight against apartheid and restoration of justice in South Africa. This saw several leaders rise to the limelight as they emerged to be the voice of the voiceless in the South African State.

One of these Christian leaders was Archbishop Desmond Tutu who has remained in the history of South Africa, featuring prominently in the reign of apartheid (BBC, 2010). He is well known worldwide for his anti-apartheid role and for boldly speaking for the blacks.

He served a very important role, especially during the entire time when Nelson Mandela was serving his prison term making him nominated for the highly coveted and prestigious Nobel Peace Prize award in 1984 for his relentless anti-apartheid efforts.

This was a real implication that the world had not only observed Tutu’s efforts but also raised its voice against the discriminatory rule in South Africa.

After Nelson Mandela was elected democratically in 1984, he appointed Archbishop Desmond Tutu to steer the South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission which was mandated to investigate all forms of crimes committed by blacks and whites during the whole period of apartheid.

Although Tutu was a teacher by training, he dropped the career after the adoption of the Bantu Education Act in 1953 (BBC, 2010). The act was meant to extend apartheid to black schools around the country, causing several schools to close down due to lack of finances after the government discontinued subsidized programs for those that did not comply.

To confirm and affirm that apartheid was not the best regime option in South Africa, Desmond Tutu was highly influenced by white clergymen like Bishop Trevor Huddleston, who strongly opposed the idea of racial discrimination that was being propagated by the white government (BBC, 2010).

Although he was closely involved in active politics, he remained focused on religious motivation, arguing that racialism was not the will of God, and that it was not to live forever. His appointment as the head of the Anglican church in 1986 did not deter him from fighting apartheid as he risked being jailed after he called the public to boycott municipal elections that were held in 1988.

He welcomed President FW De Klerk’s reforms in 1989, which included the release of the one who was later to become the first black president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela and the reinstatement of the African National Congress (BBC, 2010).

Nelson Mandela against Apartheid

Nelson Mandela is regarded as a key player in the fight against apartheid in South Africa as he led black people together with other activists to publicly denounce and condemn the discriminatory regimes of the time. As a way of demonstrating his dissatisfaction and criticism of apartheid, Mandela publicly burnt his “pass”.

All blacks were required to carry their passes as the government prohibited the movement of people to other districts (Atlas College, 2011). While working with ANC, Mandela’s involvement in anti-apartheid efforts was increased as he realized the need to have active resistance in dealing with apartheid.

He was severally charged with treason and acquitted although in 1964, Mandela was life imprisoned a move that was considered to be ill-motivated to maintain the white rule supremacy. He continued his fight while in prison as his message penetrated every village and district in the country.

Although he acted together with like-minded people, Nelson Mandela’s name stands high as the leader of the anti-apartheid campaign which culminated in his election as the first black president of South Africa in 1994 (Atlas College, 2011).

Opposing opinion

Although apartheid was highly condemned and still receives high-charged criticism, some people view it from a different perspective. Did apartheid have any benefit to the people of South Africa and to the nation at large?

Apart from propagating injustices across the country, apartheid is one of the economic drivers of South Africa with some of the policies and strategies used during that time still under active implementation by the government.

For instance, the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) was orchestrated by ANC and served as the core platform during the elections that were held in 1994 (Lundahl & Petersson, 2009). The programme focused on improvement of infrastructure, improvement of housing facilities, free schooling, sharing of land to the landless, clean water and affordable health facilities among others.

This led to the improvement of social amenities in the country. RDP also continued financing the budget revenue. It therefore suffices to mention that those who support apartheid base their argument on the status of the country after 1994 when subsequent governments chose to adopt some strategies from apartheid to drive the reconstruction agenda (Lundahl & Petersson, 2009).

As one of the leading economies in Africa, some of the institutions, factories and companies which were established during apartheid significantly contribute to development in the country. Even though new plans have been adopted, majority have their foundations rocked on apartheid.

As a result of these development initiatives, a lot has changed in South Africa. There has been substantive economic growth augmented by several factors which relate to apartheid (Lundahl & Petersson, 2009). Improved living standards among South Africans cannot also be ignored in any discussion of apartheid.

Many jobs have been created for the skilled people who never found an opportunity to work when the regime was at its operational peak. South Africa also prides on some of the most prestigious learning institutions in the region which are highly ranked on the world list. It therefore suffices to mention that apartheid had several advantages which cannot be overshadowed by its disadvantages.

Against Apartheid

Despite the advantages of apartheid discussed above, there is no doubt that the system negatively impacted South Africans in a myriad of ways. From undermining of human rights to promotion of hostility and violence among residents, there is enough evidence to condemn the regime. It affected several social structures people were not allowed to freely intermarry and interact.

This was coupled with limited expression rights as they were believed not to have rights. Movement was highly restricted as black people were to walk with passes and restricted to move within one district. Additionally, forceful evacuation was a norm as black people never owned land and houses permanently (Burger, 2011). What about employment?

Many skilled jobs were strictly reserved for whites as black people survived on manual duties with little or no pay. This contributed to low living standards and inability to meet their needs, manifested through labor strikes which were continuously witnessed in several organizations.

Consequently, violence escalated with police brutality hitting high levels and several people losing their lives as others spent the rest of their lives in jail. It was a system that needed more condemnation than just protesting in order to allow justice to prevail (Pfister, 2005).

Apartheid in South Africa is one of the most outstanding in the history of the country with millions of people with painful and remarkable memories.

With its culmination in 1994 democratic elections which saw Nelson Mandela rise to power, the regime had severe negative effects, which necessitated the need to end it and pave the way for a fair nation that respects humanity regardless of skin color, ethnicity, country of origin and gender (Pfister, 2005).

Based on the above analysis, it is important for a number of lessons to be learnt from it. World leaders need to establish and implement leadership mechanisms that would prevent recurrence of apartheid in South Africa or in other parts of the world.

To the millions who suffered under rule, reconciliation efforts are essential in allowing them to accept themselves and move on with life as they mingle with thousands of white settlers who continue owning parcels of land in the country. It should however to be forgotten that apartheid was important in transforming South Africa into what it is today. From factories and infrastructure to a stable economy, it had lifetime merits that ought to be acknowledged throughout in history.

Allen, J. (2005). Apartheid South Africa: An Insider’s Overview of the Origin and Effects of Separate Development . Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse.

Atlas College. (2011). Nelson Mandela and Apartheid. Atlas College . Web.

BBC. (2010). Profile: Archbishop Desmond Tutu . BBC News . Web.

Beinart, W., & Dubow, S. (1995). Segregation and apartheid in twentieth-century South Africa . London: Routledge.

Burger, D. (2011). History. South African Government Information . Web.

Edwards, P., & Hecht, G. (2010). History and the Techno politics of Identity: The Case of Apartheid South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36 (3), p. 619-639.

Lundahl, M., & Petersson, L. (2009). Post-Apartheid South Africa; an Economic Success Story? United Nations University . Web.

Pfister, R. (2005). Apartheid South Africa and African states: from pariah to middle power, 1961-1994 . London: I.B.Tauris.

Rosmarin, I., & Rissik, D. (2004). South Africa. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.

- Dynamics of the Relationship between Central Government and Regional Administrations in Spain since 1978

- Impact of Apartheid on Education in South Africa

- Achievements of Nelson Mandela

- Mandela’s Leadership

- Nelson Mandela: Biography and Influences

- Peace and Justice

- Disease in The News

- The Construction of the Postmodern Subject in Professional Writing

- The Syrian Conflict: An International Crisis

- Some of the most significant innovations of the 20th Century

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, March 27). Apartheid in South Africa. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid-in-south-africa/

"Apartheid in South Africa." IvyPanda , 27 Mar. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid-in-south-africa/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Apartheid in South Africa'. 27 March.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Apartheid in South Africa." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid-in-south-africa/.

1. IvyPanda . "Apartheid in South Africa." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid-in-south-africa/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Apartheid in South Africa." March 27, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/apartheid-in-south-africa/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Apartheid Essay for Grade 9 Examples: 300 -1000 Words

The apartheid era in South Africa was a time of extreme racial segregation and discrimination that lasted from 1948 to 1994. Writing an essay about this complex subject requires an understanding of history, social dynamics, and human rights. This guide will help you break down the topic into manageable parts for a well-structured essay.

Section 1: Introduction to Apartheid

- Background : Explain what apartheid was, when it began, and who was involved.

- Thesis Statement : Summarise your main argument or perspective on apartheid.

- Keyword : Apartheid, racial segregation.

Section 2: Implementation of Apartheid Laws

- Introduction : Detail how apartheid laws were created and implemented.

- Examples : Mention laws such as the Population Registration Act, Group Areas Act.

- Keyword : Laws, racial classification.

Section 3: Effects on South African Society

- Introduction : Describe how apartheid affected different racial groups.

- Examples : Provide real-life examples, like forced relocations.

- Keyword : Discrimination, societal impact.

Section 4: Resistance to Apartheid

- Introduction : Explain how individuals and groups resisted apartheid.

- Examples : Talk about movements like the ANC, people like Nelson Mandela.

- Keyword : Resistance, liberation movements.

Section 5: End of Apartheid

- Introduction : Discuss how apartheid came to an end and the transition to democracy.

- Examples : Refer to negotiations, elections, and the role of global pressure.

- Keyword : Democracy, reconciliation.

- Summary : Recap the main points and restate your thesis.

- Closing Thoughts : Offer a reflection on the legacy of apartheid in contemporary South Africa.

Additional Tips

- Use Simple Language : Write in a way that’s easy to understand.

- Use South African Context : Focus on facts and examples relevant to South Africa.

- Research : Back up your points with well-researched facts and theories.

Introduction

Apartheid , a system of racial segregation that lasted from 1948 to 1994, defined a dark era in South African history. It dictated where people could live, work, and even socialise, based on their racial classification. This essay will explore the genesis of apartheid, its impact on South African society, the brave resistance against it, and finally, its dismantling.

Section 1: Implementation of Apartheid Laws

In 1948, the National Party came to power and implemented apartheid as a legal system. The Population Registration Act classified South Africans into four racial categories: Black, White, Coloured, and Indian. Following this, the Group Areas Act designated different living areas for each racial group. These laws not only separated people but ensured that the majority of the country’s resources were reserved for the white minority.

Section 2: Effects on South African Society

The effects of apartheid were profound and painful. Black South Africans were forcibly relocated to townships with poor living conditions. The Bantu Education Act provided an inferior education for Black children, preparing them only for menial jobs. Families were torn apart, and non-white South Africans were treated as second-class citizens, all in the name of maintaining white supremacy.

Section 3: Resistance to Apartheid

Despite the oppressive regime, many South Africans resisted apartheid. The African National Congress (ANC) and other liberation movements organised protests and strikes. Icons like Nelson Mandela and Albertina Sisulu fought tirelessly against the system. The Soweto Uprising in 1976, where students protested against the use of Afrikaans in schools, is a stark example of how even the youth were involved in the struggle.

Section 4: End of Apartheid

The journey to end apartheid was long and fraught with challenges. International pressure, economic sanctions, and internal unrest gradually weakened the apartheid government. Negotiations began, leading to the release of political prisoners like Mandela. In 1994, South Africa held its first democratic elections, in which all racial groups could vote, marking the official end of apartheid.

Apartheid was a system that caused immense suffering and division in South Africa. Its impact is still felt today, as the country grapples with issues of inequality and racial tension. However, the end of apartheid also symbolises the triumph of justice, human rights, and the indomitable spirit of the South African people. The lessons learned from this period continue to shape South Africa’s journey towards a more inclusive and compassionate society. The story of apartheid is not just a history lesson; it is a guide for future generations about the importance of unity, resilience, and the continuous pursuit of equality.

Looking for something specific?

You may also like.

Implications of not Furthering your Studies After Grade 9

On Which NQF Level is Grade 9 Registered?

Physical Science Grade 9 Latest Experiments and Memos for CAPS Assessments: South Africa

Technology Grade 9 Free Textbooks and Teacher Guides for download

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Apartheid (1948-1994).

Apartheid is the name of the racial institution that was established in 1948 by the National Party that governed South Africa until 1994. The term, which literally means “apartness,” reflected a violently repressive policy designed to ensure that whites, who comprised 20% of the nation’s population, would continue to dominate the country.

Although the policy began officially in 1948, the practice of racial discrimination has deep roots in South African society. As early as 1788, Dutch colonizers began establishing laws and regulations that separated white settlers and native Africans. These laws and regulations continued after the British occupation in 1795, and soon led to the channeling of Africans into specific areas that would later constitute their so-called homelands. By 1910, the year that all of the formerly separate Boer Republics united with the British colony to become the Union of South Africa, there were nearly 300 reserves for natives throughout the country.

By 1948, Dr. D.F. Malan, the prime architect of apartheid, led the National Party in the first campaign that centered on openly racist appeals to white unity. The Party promised that if elected it would make permanent these reserves under the joint fundamental principles of separation and trusteeship. The National Party swept into office, winning 80 seats (mainly from Afrikaner voters), compared to the United Party’s 64 seats.

Soon afterwards the new government instituted a number of policies in the name of apartheid which sought to “ensure the survival of the white race” and to keep the different races separate on every level of society and in every facet of life. One of the first acts passed was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, in 1949, which outlawed marriage between Europeans and non-Europeans. The following year new legislation banned sexual intercourse between Europeans and non-Europeans. Additionally, in 1950, the Malan government passed the Population Registration Act, which categorized every South African by race, and subsequently required people to carry with them at all times a card stating their racial identity. This Act was later modified in 1952, by issuing “reference books” instead of identification passes. Anyone caught without their “reference book” was fined or imprisoned.

The Group Areas Act of 1950, however, was the core of apartheid in South Africa. The act marked off areas of land for different racial groups, and made it illegal for people to live in any but their designated areas. Thousands of Africans were uprooted and moved into racially segregated neighborhoods in cities or to reserves which by the 1970s would be called homelands.

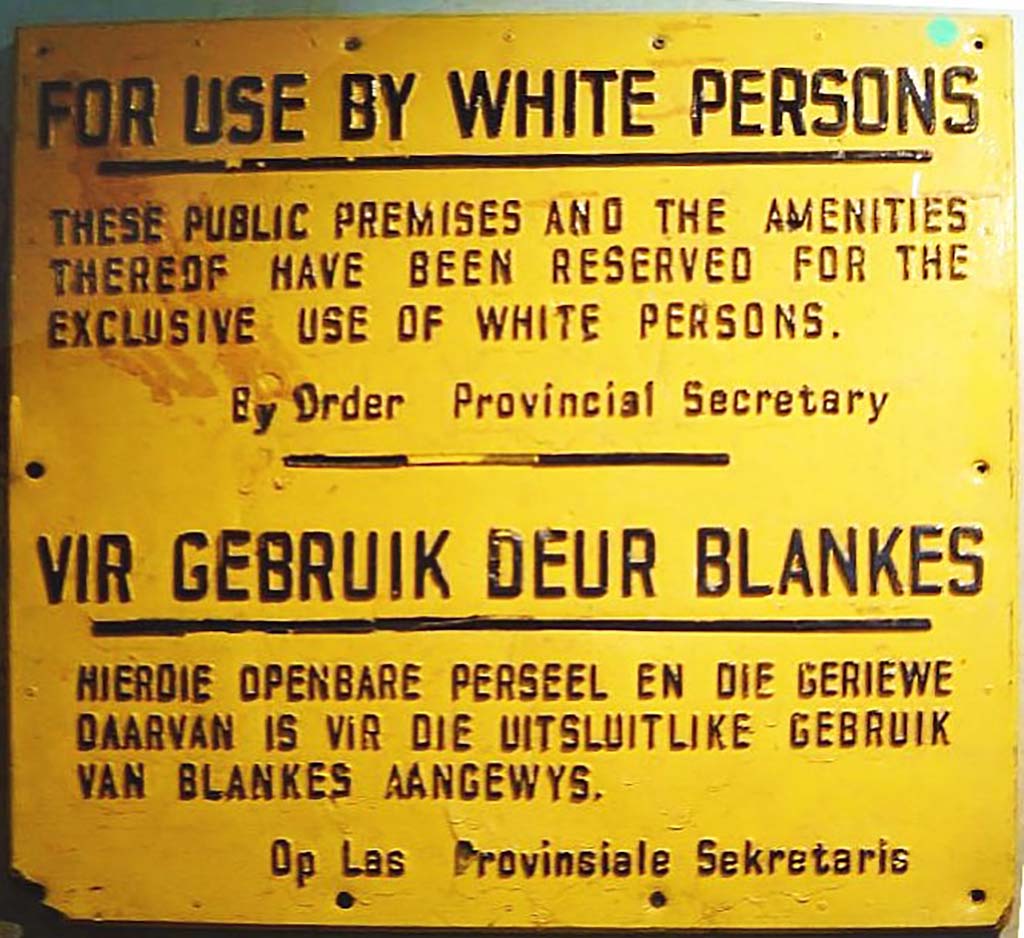

In conjunction with the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953, even black workers who during the day worked in the now residentially white only cities were still required to use different public transportation, post offices, restaurants, schools, and even separate doors, benches, and counters. The Natives Urban Areas Act in 1952 and the Native Labor Act in 1953 placed more restrictions on the black majority in South Africa.

Three important movements challenged apartheid. The oldest was the African National Congress (ANC) which was founded in 1912. The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) broke away from the ANC in 1958 and initiated its own campaign against apartheid. Both groups were eventually banned by the South African government and forced underground where they began violent campaigns of resistance. In the late 1960s, the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) was formed. Today it is known as the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) in South Africa.

Apartheid formally ended in 1994 with the first election which allowed the participation of all adult voters. With that election Nelson Mandela became the first black president of South Africa.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Martin Meredith, In the Name of Apartheid (New York: Harper & Row Publishers,1988); Mokgethi Motlhabi, Challenge to Apartheid: Toward a Moral National Resistance (Grand Rapids: William B. Erdmann’s Publishing Company, 1988); L.E. Neame, T he History of Apartheid: The Story of the Colour War in South Africa (New York: London House & Maxwell, 1962); U.S. Department of State: Diplomacy in Action. “The end of apartheid.” http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/pcw/98678.htm .

- Teaching Resources

- Upcoming Events

- On-demand Events

Introduction: Early Apartheid: 1948-1970

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- facebook sharing

- email sharing

Table of contents:

Triumph of the National Party

- Science, God and Race

Many Nations

The passbook system, the defiance campaign, the freedom charter, women protest, the sharpeville massacre, the rivonia trial, shut down at home, organizing overseas.

The roots of apartheid can be found in the history of colonialism in South Africa and the complicated relationship among the Europeans that took up residence, but the elaborate system of racial laws was not formalized into a political vision until the late 1940s. That system, called apartheid (“apartness”), remained in place until the early 1990s and set the country apart, eventually making South Africa a pariah state shunned by much of the world.

Having aggressively promoted an ideology of Afrikaner nationalism for a decade, the National Party won South Africa’s 1948 election by promising to clamp down on non-white groups. Once in office, the National Party promptly began to institute racial laws and regulations it called apartheid (a word that means “apartness” in Afrikaans). Led by Daniel Malan, a former pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church turned politician, the National Party described apartheid in a pamphlet produced for the election as “a concept historically derived from the experience of the established White population of the country, and in harmony with such Christian principles as justice and equity. It is a policy which sets itself the task of preserving and safeguarding the racial identity of the White population of the country; of likewise preserving and safeguarding the identity of the indigenous peoples as separate racial groups.” 1

- 1 D. W. Kruger, ed., South African Parties and Policies 1910–1960 (London: Bowes and Bowes, 1960), available at Politicsweb, accessed July 29, 2015.

Apartheid Era Sign

The Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (passed in 1953) led to signs such as the one shown above. The Act prohibited people of different races from using the same public amenities.

By 1948, segregation of the races had long been the norm. But as journalist Allister Sparks noted, apartheid, drawing on racist anthropology and racist theology, “substituted enforcement for convention. What happened automatically before was now codified in law and intensified when possible. . . . [Racism] became a matter of doctrine, of ideology, of theologized faith infused with a special fanaticism, a religious zeal.” 1

Religion was an important aspect of Afrikaner identity. Most Afrikaners were members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, a strict and conservative Calvinist church that promoted the belief that the Afrikaners were a new “chosen people” to whom God had given South Africa. Journalist Terry Bell explained the role of religion in the outlook of those who supported the National Party: “Afrikaners [saw themselves] as players in the unfolding of the Book of Revelations, upholding the light of Christian civilization against an advancing wall of darkness. . . . It was God’s will that the ‘Afrikaner nation’ . . . linked by language and a narrow Calvinism, had been placed on the southern tip of the African continent.” 2 As a result, they saw themselves as a select group whose right to the land was greater than any other group’s.

The new National Party administration offered a stark view of ethnic categories. As laid out in the Population Registration Act of 1950, these categories were as follows: “white” (“a person who in appearance obviously is, or who is generally accepted as a white person, but does not include a person who, although in appearance obviously a white person, is generally accepted as a coloured person”), “native” (“a person who in fact is or is generally accepted as a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa”), and “coloured” (“a person who is not a white person or a native”). 3 “Indian” was soon added as a fourth group. The groups were not only portrayed as distinct and fundamentally different; drawing on principles of Social Darwinism, they were ranked hierarchically in terms of supposed intellectual capacity and other attributes. The white population stood at the pinnacle of the South African racial hierarchy, with the National Party ideology claiming that they should dominate the other groups because of their natural superiority. Their control of the state guaranteed whites superior access to education, healthcare, employment, and housing. “Natives,” or black South Africans, stood at the very bottom of this steep hierarchy—a necessity in the eyes of Afrikaners, who believed not only that their livelihoods depended on depriving black South Africans of land, voting rights, the right to marry freely, and, above all, the right to participate freely in the labor market but also that Africans were not as deserving as whites of these privileges. Indian and “coloured” groups were “ranked” above black South Africans, allowing them some employment and mobility privileges denied to black South Africans yet still making them subservient to the white South African population.

| nationality | Percent of Population |

|---|---|

| Native | 68.3% |

| White | 19.3% |

| Colored | 9.4% |

| Indian | 3% |

Science, God, and Race

The triumph of the National Party pushed to the forefront of South African racism the ideas fostered by church leaders and scholars in Afrikaner institutions. During the 1930s, scientific books and articles, some written by scholars at Stellenbosch University and the University of Pretoria, lent credence to the idea that white populations were of superior intelligence to nonwhite groups. The Dutch Reformed Church, whose congregations had been segregated since 1857, also preached that, following the Tower of Babel, God had ordained that different cultures be distinct and sovereign. The church’s ideas combined with the pseudoscience of race to give rise to a secular theology of Christian nationalism. If groups were to develop as God intended, they needed to live separately.

Because they conceived of blacks and whites as fundamentally different, Afrikaners concluded that contact between the groups fostered conflict. Each group would prosper most if left to develop on its own; to impose segregation was to protect and promote black culture, they argued. The 1947 National Party campaign pamphlet explained:

The party holds that a positive application of apartheid between the white and non-white racial groups and the application of the policy of separation also in the case of the non-White racial groups is the only sound basis on which the identity and the survival of each race can be assured and by means of which each race can be stimulated to develop in accordance with its own character, potentialities and calling. Hence inter marriage between the two groups will be prohibited. Within their own areas the non-white communities will be afforded full opportunity to develop, implying the establishment of their own institutions and social services, which will enable progressive non-Whites to take an active part in the development of their own peoples. The policy of our country should envisage total apartheid as the ultimate goal of a natural process of separate development. 4

The reading Apartheid Policies offers a more extended explanation of the ideas behind apartheid, as publicly articulated by the party.

A contradiction arose, however, because if black South African labor had been subtracted from the white South African economy, the latter would have immediately collapsed. While the theory of apartheid argued that the races should be kept separate, the economy of the South African state depended heavily on black South African labor. Therefore, the apartheid state had to permit black South African laborers to come and go between white and black territories.

After the National Party took power, it implemented a series of laws designed both to separate each of the country’s racial groups and to divide and weaken the black South African population and allow for the easy exploitation of its labor. The Population Registration Act created a national system of racial classification that gave every citizen a single identification number and racial label that determined exactly what privileges this person would be able to enjoy. Where one could live, whether one had to carry a passbook to travel, and what sort of education one could receive depended on one’s racial classification. While white South Africans enjoyed every conceivable right, black South Africans could not vote for South African officials, and coloured South Africans could only vote for white representatives—they could not run for office themselves. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 banned interracial marriage, while the Immorality Act of 1950 “prohibited sex between whites and non-whites.”

| Law | Year | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Prohibition of Mixed Marriages | 1949 | Banned marriage between whites and non-whites. |

| Population Registration Act | 1950 | Created a national register in which every individual’s race was officially recorded. |

| Group Areas Act | 1950 | Legally codified segregation by creating distinct residential areas for each race. |

| Immorality Act | 1950 | Prohibited sex between whites and non-whites. |

| Suppression of Communism Act | 1950 | Outlawed communism. Allowed detention on communism charges of those who objected to or protested apartheid. |

| Bantu Authorities Act | 1951 | Created black homelands and governments. |

| Separate Representation of Voters Act | 1951 | Removed coloureds from voter rolls. |

| Bantu Education Act | 1953 | Set up a separate educational system for black South Africans, charged with creating an “appropriate” curriculum. |

| Native Resettlement Act | 1954 | Allowed the removal of black South Africans from areas reserved for whites. |

| Extension of Education Act | 1956 | Excluded black South Africans from white universities. Set up separate universities for each racial group. |

| Terrorism Act | 1967 | Allowed indefinite detention without trial of opponents of apartheid and created a security force. |

The Group Areas Act of 1950 was the Malan government’s first attempt to increase the separation between white and black urban residential areas. The law was both a continuation of earlier laws of segregation and a realization of an apartheid ideal that cultures should be allowed to develop separately. The law declared many historically black urban areas officially white. The Native Resettlement Act of 1954 authorized the government to force out longtime residents and knock down buildings to make room for white-owned homes and businesses. Whole neighborhoods were destroyed under the authority of this act. For example, on February 9, 1955, Prime Minister Malan sent in 2,000 police officers to remove the 60,000 residents of Sophiatown, a vibrant African neighborhood in central Johannesburg. Black South African residents were forcibly resettled in the Meadowlands neighborhood of Soweto, where they were expected to move into houses without electricity, water, or toilets. In Durban, Indian neighborhoods faced a similar fate. City centers became enclaves for the white South African population, while black, coloured, and Indian South Africans were relegated to townships at the periphery of the urban areas, which were often far removed from centers of employment and resources such as hospitals and recreation spaces. Generally, the townships were intended to contain the black South African population by restricting movement through urban planning while ensuring that black South Africans had permission to leave these areas in order to work.

- 1 Allister Sparks, The Mind of South Africa: The Story of the Rise and Fall of Apartheid (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2006), 190.

- 2 Terry Bell, Unfinished Business: South Africa, Apartheid and Truth (London: Verso, 2003), 23.

- 3 Population Registration Act (1950) , Wikisource entry, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 4 D. W. Kruger, ed., South African Parties and Policies 1910–1960 (London: Bowes and Bowes, 1960), available at Politicsweb, accessed July 29, 2015.

Bantustans in South Africa

With the passing of the Bantu Authorities Act in 1951, the apartheid set in motion the creation of ten bantustans in South Africa, illustrated in this map.

Apartheid laws treated black South Africans not as citizens of South Africa but rather as members of assigned ethnic communities. The Bantu Authorities Act (1951) and the Bantu Self-Government Act (1959) created ten “homelands” for black South Africans, known as Bantustans, and established new authorities in the Bantustans. While the apartheid state portrayed the Bantustans as a system that offered black South Africans independence, giving the appearance of self-government, the leaders of the homelands were appointed by the apartheid state. Furthermore, black South Africans were assigned these ethnic identities and corresponding “homelands” even if they did not see this as a central aspect of their identity. Black South Africans were essentially stripped of their South African citizenship.

By making black South Africans citizens of Bantustans, the government deflected any possible criticisms of refusing them the right to vote in South Africa. But this arrangement also very deliberately created a system of migrant labor. Since the homeland areas, which were mostly rural and underdeveloped, offered inhabitants few employment opportunities, most had to search for work in cities and live temporarily in townships. Given the desperate situation in the homelands, the apartheid state was ensured of a regular source of cheap labor for white-owned businesses and homes.

Although they were said by apartheid authorities to bear a historical association with the different kingdoms, Bantustans were scattered around the fringes of the country without any consideration for the well-being of their residents. KwaZulu in Natal, for example, was divided into many pieces, separated by large areas designated as white. The apartheid government reserved urban areas, the most desirable farmland, and regions rich in natural resources for white South Africans, while it allocated the least arable land for the Bantustans. Although black South Africans constituted nearly 70% of the population, only 13% of South Africa’s territory was allocated to the Bantustans. The reading A Wife’s Lament offers a look at how the creation of the homelands affected black South African families.

Girl Walking to School, Mthatha

A child walks to school through the barren village of Qunu, South Africa, located just outside of the town of Mthatha.

Dividing the black South African population into Bantustans was in part intended to break the solidarity that had formed between groups of black South Africans in the face of white oppression. By cultivating a false sense of “tribal” belonging, the government sought to reduce the black South African population to many small, ineffective groups, channeling discontent from resistance to apartheid into internal bickering.

A decade after the rise of the National Party, many black South Africans found themselves effectively stateless. They could only enter white areas to work, and they needed documents authorizing them to do so.

By the middle of the twentieth century, vast numbers of black South Africans commuted daily from Bantustans and townships to the white areas where they worked. Various forms of internal passports had existed in South Africa since the early twentieth century, but the apartheid government expanded and formalized the pass system. Designed to satisfy both the need for black labor and the need to protect white advantages, “pass” laws required every black male over the age of 16 to carry a passbook, which contained a photograph, fingerprints, a racial classification, place of work, and the bearer’s police record.

Additionally, the passbook had to have a current signature from an employer and proof that the bearer had paid income taxes. The passbook bureaucracy was so convoluted that few people were able keep their records current, providing authorities with an excuse for detaining black South African men at will. Anyone living in a black township on the outskirts of a white city who did not possess appropriate papers was effectively treated as an illegal alien and subject to arrest. Those found in violation were sometimes imprisoned, often forced to pay fines, and sometimes sent back to their homelands. Eventually, black South African women were also required to carry passes, an act that had a tragic impact on the lives of tens of thousands of families who were not allowed to live together. Only a few of these women with formal salaried employment were able to secure the necessary passes and keep them current, thereby satisfying the authorities’ requirements to be legally living in the same house as their husbands. Most black South African women were forced to remain in the homelands, raising their children and eking out a living off the land while their husbands worked in the cities or on white-owned farms.

Most black South Africans were obliged to leave “white areas” by sunset. At the country’s many checkpoints and roadblocks, black South Africans were at the mercy of the police and could summarily be stopped, arrested, and deported to homelands. Thousands of black South Africans were forced to break the law on a daily basis as they searched for work or attempted to keep their families together.

Police carried out daily raids on black residences, bursting in at midnight, forcing residents to show their passes, and arresting those out who did not have them. Police brutality was rife; hundreds of thousands of black South Africans were arrested, thousands disappeared from their homes without a trace, and hundreds lost their lives to the guns and batons of law enforcement officials. The government recruited black South Africans to join the police force and serve as informants, torturers, and, in some cases, executioners, and for a variety of reasons (bribes, economic pressures, and scare tactics), some black South Africans helped the government enforce apartheid. The reading Experiencing Apartheid gives an account of how the draconian enforcement of apartheid laws could affect black South Africans.

As apartheid laws were implemented, South Africa’s black leaders looked for a way to protest the changes imposed by the minority white government. Denied the right to vote, they had to find other means of expressing opposition outside the formal political system. From 1950 to 1952, the African National Congress (ANC) organized mass actions, which included boycotts, civil disobedience, demonstrations, and strikes.

A group of resisters proudly pose after their release from prison in Durban during the Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws, 1952.

Launched in April 1952, on the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the first Dutch colonists, this Defiance Campaign became the largest campaign of civil disobedience in South Africa’s history up to that point. It was also the first multiracial mass-resistance campaign, and its unified leadership included representatives from the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, and the Coloured People’s Congress. Together with other groups, these organizations formed the Congress Alliance, which forged a multiracial front against the implementation of apartheid. 1 Following heavily attended demonstrations in a number of towns, defiance of the newly erected racial laws commenced on June 26, 1953. Ten thousand volunteers, organized by the leader of the ANC Youth League, 34-year-old Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, were instructed to enter forbidden areas without passes, use entrances designated “Europeans only,” and occupy “white only” counters and waiting rooms. 2 These violations were designed to flood the prison system, rendering law enforcement impossible.

- 1 For Nelson Mandela’s description of the first months of the campaign and the unity between the different groups, see “ We Defy—10,000 Volunteers Protest Against Unjust Laws ,” August 30, 1952, African National Congress website, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 2 Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story , 3rd ed. (Cape Town: The Reader’s Digest Association Limited, 1994), 385.

Nelson Mandela, 1937

A young Nelson Mandela poses for a photograph in Umtata shortly before moving to Fort Beaufort to attend Healdtown Comprehensive School.

A decade later, Mandela reflected on the goals and strategies behind the Defiance Campaign:

Even after 1949, the ANC remained determined to avoid violence. At this time, however, there was a change from the strictly constitutional means of protest which had been employed in the past. The change was embodied in a decision which was taken to protest against apartheid legislation by peaceful, but unlawful, demonstrations against certain laws. Pursuant to this policy the ANC launched the Defiance Campaign, in which I was placed in charge of volunteers. This campaign was based on the principles of passive resistance. More than 8,500 people defied apartheid laws and went to jail. Yet there was not a single instance of violence in the course of this campaign on the part of any defier. I and nineteen colleagues were convicted for the role which we played in organising the campaign, but our sentences were suspended mainly because the judge found that discipline and non-violence had been stressed throughout. 1

The government lashed out, arresting over 8,000 South Africans and handing out stiff penalties and long prison sentences to those who had broken apartheid laws. It adopted the Public Safety Act (1953), which allowed the president to suspend all existing laws, stripping away basic civil liberties. “The government saw the campaign,” Mandela later recalled, “as a threat to its security and its policy of apartheid. They regarded civil disobedience not as a form of protest but as a crime, and were perturbed by the growing partnership between Africans and Indians. Apartheid was designed to divide racial groups, and we showed that different groups could work together. The prospect of a united front between Africans and Indians, between moderates and radicals, greatly worried them.” 2

While the Defiance Campaign lost momentum after a few months, and it did not achieve many concessions from the government, it was a turning point for South Africa. For the liberation movement, it was the first mass campaign, swelling the membership ranks of the ANC from just 7,000 to 100,000 and helping to transform the group from an elite organization into a mass movement. 3

In early 1955, the ANC organized a listening campaign, in which they sent out 50,000 volunteers to talk with people across the country about their political hopes for South Africa. In June 1955, the ANC, along with several other anti-apartheid political organizations—the South African Indian Congress, the Coloured People’s Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, and the Congress of Democrats—developed a set of political demands that drew on the results of these interviews. The “Freedom Charter,” as it became known, called for a nonracial South Africa, in which people of all races would have equal rights and would share in the country’s wealth.

The Freedom Charter became the political agenda for the ANC, shaping its actions over the next several decades. The charter called for rights for all South Africans, not just black South Africans, and this concept of nonracialism became an important principle behind the ANC’s approach to political change. The Freedom Charter served as the guiding document for the ANC in its struggle against apartheid and beyond, as its nonracialism ultimately became a basis for ANC policies after the fall of apartheid. The reading The Freedom Charter includes the text of this foundational document.

Although their role has often been overlooked in historical accounts of resistance to apartheid, black South African women played an important part in opposing the system of racial segregation. (White and “coloured” women were part of the resistance, but the vast majority were black South Africans.) In the early 1900s, black South African women successfully resisted proposed legislation that would require them to carry passbooks. After a setback in 1918, women organized again to end the practice altogether under the leadership of Charlotte Maxeke, a gifted singer, social worker, and activist—a hero of the early days of protest. She was called “the mother of African freedom in this country” by A. B. Xuma, who served as the president of the ANC in the 1940s. 4

- 1 Nelson Mandela, “ An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die ,” The Guardian , April 22, 2007, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 2 Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1994), 116.

- 3 For a full and vivid description of the campaign, see Monty Naicker, “The Defiance Campaign Recalled,” June 30, 1972, African National Congress website, accessed July 27, 2015.

- 4 Andile Mnyandu, “ Charlotte Maxeke ,” eThekwini Municipality website, accessed July 27, 2015.

Woman Showing Her Passbook

An unidentified black South African woman defiantly shows her passbook.

The multiracial Federation of South African Women was formed in the 1950s, representing hundreds of thousands of women. Together with the ANC Women’s League, the federation organized many local demonstrations against the pass laws, culminating in the March on Pretoria. On August 9, 1956, about 20,000 women peacefully gathered in front of the city’s Union Buildings. They stood in silence for 30 minutes and then, breaking the quiet, chanted a call to the prime minister: “Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo!” (Now that you have touched the women, you have struck a rock!) Alerted to the protest ahead of time, the prime minister, J. G. Strijdom, had slipped out of town. Before they concluded their protest, activists left on the prime minister’s door a petition bearing the signatures of 100,000 women. Their chant became the slogan for future women’s protests. The reading Women Rise Up against Apartheid and Change the Movement features a firsthand account of the 1956 women’s march.

By the late 1950s, a growing number of activists questioned the tactics of the African National Congress. The young founders of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), formed in 1959, believed that only an all-black African organization, in league with anti-colonial Africans throughout the continent, could adopt the forceful posture necessary to overcome apartheid. The time had come, these firebrands believed, to reclaim the land stolen by whites. In his inaugural speech, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, head of the PAC, outlined their approach:

[W]e reject both apartheid and so-called multi-racialism as solutions of our socio-economic problems. . . . To us the term “multi-racialism” implies that there are such basic insuperable differences between the various national groups here that the best course is to keep them permanently distinctive in a kind of democratic apartheid. That to us is racialism multiplied, which probably is what the term connotes. We aim, politically, at government of the Africans by the Africans, for the Africans, everybody who owes his only loyalty to Afrika and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African. 1

Questioning the effectiveness of nonviolence against apartheid, the PAC set up a military wing, Poqo, that was feared by the white establishment.

The PAC announced to authorities that it would lead a peaceful demonstration against pass laws in the township of Sharpeville on March 21, 1960. Some 5,000 protesters gathered in the town center and then marched toward the police station to turn themselves in for defying pass laws. 2 Around midday, the police panicked and opened fire on the demonstrators, killing 69 people and wounding another 180. Most were shot in the back as they fled.

Black South African leaders called for a day of mourning and a “stay-at-home” strike on March 28, 1960. Hundreds of thousands of black South Africans did not show up for work that day, making it the first successful national strike in the nation’s history. Marches took place in Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town; the largest included a group of 30,000 who marched from Langa to Cape Town, led by 23-year-old Philip Kgosana. Fearing that black protests might spread, the government acted decisively in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre. It declared a state of emergency and arrested more than 11,000 people, including the leaders of both the ANC and the PAC. On April 8, the government banned both organizations. This put an abrupt end to the protests and ushered in a period of harsh repression that lasted for more than a decade.

During the 1960s, the government intensified its policies against the anti-apartheid movement by severely restricting the ability of the movement’s leaders to speak in public and to mobilize the population. The government went on to scrap what few rights non-white workers had, including the rights to organize, bargain, and strike, and it also intensified efforts to shut down surviving black urban neighborhoods and move the black population to the townships and homelands.

Although officially banned, the ANC continued to function clandestinely. The young leadership of the ANC, having seen their hopes for change dashed so violently, began to discuss a new approach to resistance. Despite opposition from the old guard, in 1961 the young upstarts prevailed: while there would never be official ANC approval, the creation of an armed wing was tacitly accepted. Named Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation,” known as MK), the clandestine group had Nelson Mandela as its commander.

Such a group needed new skills and new partners. Mandela and the other militant ANC members formed an alliance with the South African Communist Party, a multiracial political organization with ties to the Soviet Union that had been banned in 1950 but remained active underground, working primarily to support the interests of workers. They based MK operations at a farm in Rivonia, not far from Johannesburg. Setting up a network of operatives committed to terror permitted MK, over a year and a half, to carry out approximately 200 attacks on government facilities. By January 1962, Mandela had traveled to Algeria, where he learned the basics of guerrilla warfare from members of that nation’s National Liberation Front. A fortnight after his return to South Africa, he was arrested on the charges of inciting workers to strike and leaving the country without a passport. A year later, Mandela’s MK comrades were arrested at their Rivonia training camp.

In 1963, three years after the terror of the Sharpeville massacre carried out by government forces, the Rivonia Trial began with the government seeking to accuse its opponents of fomenting violence. Ten defendants, including six black Africans, three white Jews, and the son of an Indian immigrant, were charged with sabotage and attempting to violently overthrow the government of South Africa.

During the trial, the defendants decided not to deny the charge of sabotage. They wanted the world to know what they had done and why. Their lawyers expressed misgivings about their decision, because it meant that they could be put to death for treason. But the revolutionaries felt that they had to take the risk, using the trial to make their positions known to every person in South Africa.

When he took the stand at the Pretoria Supreme Court, Mandela described his personal journey within the resistance movement, explaining the reasoning behind the adoption of a militant approach. (The reading Mandela on Trial includes the text of this testimony.) The prosecutor attempted to prove that the group, which he labeled communist, was plotting to overthrow the government of South Africa. He played on Afrikaner fears of Soviet revolutionary plots. The government had long presented itself as a true ally of the West, securing generous financial and military support—a position unusual among African states, many of which adopted socialism as a reaction against the colonial powers they had thrown off.

When the trial ended in June 1964, two men had been acquitted. Six of the remaining eight, including Mandela, were found guilty on all counts and sentenced to life in prison.

In the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre and the government crackdown that followed, the ANC leadership charged Oliver Tambo, the organization's deputy president, with the task of beginning to organize overseas. With protest nearly impossible within the country and so many top ANC leaders in prison, Tambo looked for new ways to fight against the apartheid regime. Making use of a home base in London, he lobbied international leaders to speak out against the brutality in his homeland. Almost immediately, Tambo and British anti-apartheid movement activists organized to have South Africa removed from the British Commonwealth, an intergovernmental organization made up of countries that were formerly part of the British Empire—a move that succeeded in 1961. At the same time, activists began to lobby against South Africa in the United Nations, winning a 1962 vote at the UN General Assembly for a trade ban on South Africa. A partial arms ban followed a year later. Further international pressure against South Africa’s discriminatory policies came from the International Olympic Committee, which first suspended South Africa from participating in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and then formally banned the country from the Olympics in 1970. The ANC, with Tambo’s leadership, eventually set up 27 overseas missions.

However, diplomacy was only one part of the strategy. In 1965, the countries of Tanzania and Zambia agreed to let the ANC’s unofficial armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), set up paramilitary training camps. Under the leadership of Abongz Mbede and Joe Slovo, a South African Jew whose family emigrated from Lithuania, the MK sought to bring what they called an “armed struggle” to South Africa. In the late 1960s, though, South Africa was surrounded by neighbors that were allies of the apartheid government, making it difficult for fighters to make it into the country. An official history of the ANC describes the situation:

The ANC consultative conference at Morogoro, Tanzania in 1969 looked for solutions to this problem. . . .The Morogoro Conference called for an all-round struggle. Both armed struggle and mass political struggle had to be used to defeat the enemy. But the armed struggle and the revival of mass struggle depended on building ANC underground structures within the country. A fourth aspect of the all-round struggle was the campaign for international support and assistance from the rest of the world. These four aspects were often called the four pillars of struggle. The non-racial character of the ANC was further consolidated by the opening up of the ANC membership to non-Africans. 3

- 1 “ Robert Sobukwe Inaugural Speech, April 1959 ,” African National Congress website, accessed June 2018.

- 2 David James Smith, Young Mandela: The Revolutionary Years (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2010), 210.

- 3 “ A Brief History of the African National Congress ,” African National Congress website, accessed June 2018.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “ Introduction: Early Apartheid: 1948-1970 ”, last updated August 3, 2018.

You might also be interested in…

10 questions for the future: student action project, 10 questions for the present: parkland student activism, the union as it was, radical reconstruction and the birth of civil rights, expanding democracy, voting rights in the united states, my part of the story: exploring identity in the united states, the struggle over women’s rights, equality for all, protesting discrimination in bristol, the hope and fragility of democracy in the united states, enacting freedom, inspiration, insights, & ways to get involved.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Harsh Reality of Life Under Apartheid in South Africa

By: Erin Blakemore

Updated: August 1, 2023 | Original: April 26, 2019

From 1948 through the 1990s, a single word dominated life in South Africa. Apartheid —Afrikaans for “apartness”—kept the country’s majority Black population under the thumb of a small white minority. It would take decades of struggle to stop the policy, which affected every facet of life in a country locked in centuries-old patterns of discrimination and racism.

What Was Apartheid?

The segregation began in 1948 after the National Party came to power. The nationalist political party instituted policies of white supremacy, which empowered white South Africans who descended from both Dutch and British settlers in South Africa while further disenfranchising Black Africans.

The system was rooted in the country’s history of colonization and slavery. White settlers had historically viewed Black South Africans as a natural resource to be used to turn the country from a rural society to an industrialized one. Starting in the 17th century, Dutch settlers relied on slaves to build up South Africa. Around the time that slavery was abolished in the country in 1863, gold and diamonds were discovered in South Africa.

That discovery represented a lucrative opportunity for white-owned mining companies that employed—and exploited—Black workers. Those companies all but enslaved Black miners while enjoying massive wealth from the diamonds and gold they mined. Like Dutch slaveholders, they relied on intimidation and discrimination to rule over their Black workers.

Apartheid Laws and Segregation

The mining companies borrowed a tactic that earlier slaveholders and British settlers had used to control Black workers: pass laws . As early as the 18th century, these laws had required members of the Black majority, and other people of color, to carry identification papers at all times and restricted their movement in certain areas. They were also used to control Black settlement, forcing Black people to reside in places where their labor would benefit white settlers.

Those laws persisted through the 20th century as South Africa became a self-governing dominion of the United Kingdom. Between 1899 and 1902, Britain and the Dutch-descended Afrikaners fought one another in the Boer War, a conflict that the Afrikaners eventually lost. Anti-British sentiment continued to foment among white South Africans, and Afrikaner nationalists developed an identity rooted in white supremacy. When they took control in 1948, they made the country’s already discriminatory laws even more draconian.

Racist fears and attitudes about “natives” colored white society. Though apartheid was supposedly designed to allow different races to develop on their own, it forced Black South Africans into poverty and hopelessness. “Grand” apartheid laws focused on keeping Black people in their own designated “homelands.” And “petty” apartheid laws focused on daily life and restricted almost every facet of Black life in South Africa.

Pass laws and apartheid policies prohibited Black people from entering urban areas without immediately finding a job. It was illegal for a Black person not to carry a passbook. Black people could not marry white people. They could not set up businesses in white areas. Everywhere from hospitals to beaches was segregated. Education was restricted. And throughout the 1950s, the NP passed law after law regulating the movement and lives of Black people.

Though they were disempowered, Black South Africans protested their treatment within apartheid. In the 1950s, the African National Congress, the country’s oldest Black political party, initiated a mass mobilization against the racist laws, called the Defiance Campaign . Black workers boycotted white businesses, went on strike, and staged non-violent protests.

These acts of defiance were met with police and state brutality. Protesters were beaten and tried en masse in unfair legal proceedings. But though the campaigns took a toll on Black protesters, they didn’t generate enough international pressure on the South African government to inspire reforms.

Steve Biko, Nelson Mandela and the Black Consciousness Movement

In 1960, South African police killed 69 peaceful protesters in Sharpeville, sparking nationwide dissent and a wave of strikes. A subgroup of protesters who were tired of what they saw as ineffective nonviolent protests began to embrace armed resistance instead. Among them was Nelson Mandela , who helped organize a paramilitary subgroup of the ANC in 1960. He was arrested for treason in 1961 and was sentenced to life in prison for charges of sabotage in 1964.

In response to the 1960 protests, the government declared a state of emergency. This tactic cleared the way for even more apartheid laws to be put in place. Despite the state of emergency, Black groups continued to organize and protest. But a crackdown on many movement leaders forced them into exile abroad.

Anti-apartheid protests continued as life for Black South Africans became more and more dire under apartheid. On June 16, 1976, up to 10,000 Black schoolchildren, inspired by new tenets of Black consciousness, marched to protest a new law that forced them to learn Afrikaans in schools. Steve Biko , anti-apartheid activist and co-founder of the South African Students' Organization, spearheaded the movement and was arrested multiple times for his activism before dying from injuries sustained while in police custody on September 12, 1977.

How Nelson Mandela Used Rugby as a Symbol of South African Unity

In a nation bitterly divided by apartheid, Mandela used the game to foster shared national pride.

Nelson Mandela: His Written Legacy

Read excerpts from letters, speeches and memoirs reflecting on each stage of his life—from the innocence of a tribal village boy to the triumphs and pressures of being South Africa's first black president.

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela’s Childhood and Education Nelson Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, into a royal family of the Xhosa‑speaking Thembu tribe in the South African village of Mvezo, where his father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa (c. 1880‑1928), served as chief. His mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was the third of Mphakanyiswa’s four wives, who together bore him […]

When Did Apartheid End?

During the 1980s, resistance became even more fierce. Peaceful and violent protests finally began to spark international attention. Nelson Mandela , the movement’s most powerful and well-known representative, had been imprisoned since 1964. But he inspired his followers to continue resisting and conducted secret negotiations to end apartheid.

By the end of the 1980s, discontentment was growing among white South Africans about what they saw as South Africa’s diminished international standing. By then, the country faced sanctions and economic ramifications as international businesses, celebrities, and other governments pressured the government to end discrimination. As the economy faltered, the government was locked in a stalemate with anti-apartheid activists.

But when South African president P.W. Botha resigned in 1989, the stalemate finally broke. Botha’s successor, F.W. de Klerk, decided it was time to negotiate to end apartheid in earnest.

In February 1990, de Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and other opposition groups and released Mandela, whose secret negotiations had thus far failed, from prison. Despite continued political violence, Mandela, de Klerk and their allies began intensive negotiations.