Hypertension: Introduction, Types, Causes, and Complications

Cite this chapter.

- Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO 4 ,

- Yoshio Iwashima MD, PhD, FAHA 5 &

- Kei Kamide MD, PhD, FAHA 6

8761 Accesses

4 Citations

Hypertension remains one of the most significant causes of mortality worldwide. It is preventable by medication and lifestyle modification. Office blood pressure (BP), out-of-office BP measurement with ambulatory BP monitoring, and self-BP measurement at home are reliable and important data for assessing hypertension. Primary hypertension can be defined as an elevated BP of unknown cause due to cardiovascular risk factors resulting from changes in environmental and lifestyle factors. Another type, secondary hypertension, is caused by various toxicities, iatrogenic disease, and congenital diseases. Complications of hypertension are the clinical outcomes of persistently high BP that result in cardiovascular disease (CVD), atherosclerosis, kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, preeclampsia, erectile dysfunction, and eye disease. Treatment strategies for hypertension consist of lifestyle modifications (which include a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat food or fish with a reduced content of saturated and total fat, salt restriction, appropriate body weight, regular exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation) and drug therapies, although these vary somewhat according to different published hypertension treatment guidelines.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Changing concepts in hypertension management

Hypertension

Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Hypertension: The Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults: Update of Clinical Guidelines 18 and 34 [Internet]. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2011 Aug. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83274 . PubMed PMID: 22855971.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:3–15.

Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014;63:878–85.

Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253–387.

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Kannel WB, Levy D. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:1682–6.

Kokubo Y, Nakamura S, Watanabe M, Kamide K, Kawano Y, Kawanishi K, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with incident hypertension according to blood pressure categories in non-hypertensive population in the Suita study: an Urban cohort study. Hypertension. 2011;58:E132.

Google Scholar

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10.

Kokubo Y. Traditional risk factor management for stroke: a never-ending challenge for health behaviors of diet and physical activity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:11–7.

Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, Braun LT, Bravata DM, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3754–832.

European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee, ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457–507.

Article Google Scholar

Guild SJ, McBryde FD, Malpas SC, Barrett CJ. High dietary salt and angiotensin II chronically increase renal sympathetic nerve activity: a direct telemetric study. Hypertension. 2012;59:614–20.

Mu S, Shimosawa T, Ogura S, Wang H, Uetake Y, Kawakami-Mori F, et al. Epigenetic modulation of the renal beta-adrenergic-WNK4 pathway in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat Med. 2011;17:573–80.

WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva, World Health Organization (WHO), 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133309/pdf/TOC.pdf .

Kokubo Y. Prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases: a comparison of lifestyle factors in westerners and east Asians. Hypertension. 2014;63:655–60.

Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC, et al. A prospective study of nutritional factors and hypertension among US men. Circulation. 1992;86:1475–84.

Ascherio A, Hennekens C, Willett WC, Sacks F, Rosner B, Manson J, et al. Prospective study of nutritional factors, blood pressure, and hypertension among US women. Hypertension. 1996;27:1065–72.

Stamler J, Liu K, Ruth KJ, Pryer J, Greenland P. Eight-year blood pressure change in middle-aged men: relationship to multiple nutrients. Hypertension. 2002;39:1000–6.

Miura K, Greenland P, Stamler J, Liu K, Daviglus ML, Nakagawa H. Relation of vegetable, fruit, and meat intake to 7-year blood pressure change in middle-aged men: the Chicago Western Electric study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:572–80.

Tsubota-Utsugi M, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Kurimoto A, Suzuki K, et al. High fruit intake is associated with a lower risk of future hypertension determined by home blood pressure measurement: the OHASAMA study. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:164–71.

Ueshima H, Stamler J, Elliott P, Chan Q, Brown IJ, Carnethon MR, et al. Food omega-3 fatty acid intake of individuals (total, linolenic acid, long-chain) and their blood pressure: INTERMAP study. Hypertension. 2007;50:313–9.

Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ, Grobbee DE, Donders AR, Kok FJ. Blood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: metaregression analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1493–9.

Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, de Lezenne CC. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1205–9.

Yamori Y. Food factors for atherosclerosis prevention: Asian perspective derived from analyses of worldwide dietary biomarkers. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2006;11:94–8.

PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM. Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2003;42:878–84.

Hamer M, Chida Y. Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2008;46:9–13.

Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Suematsu C, Okada K, Fujii S, Endo G. Walking to work and the risk for hypertension in men: the Osaka Health Survey. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:21–6.

Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, Gienger AL, Lin N, Lewis R, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296–304.

Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24:215–33.

Groppelli A, Giorgi DM, Omboni S, Parati G, Mancia G. Persistent blood pressure increase induced by heavy smoking. J Hypertens. 1992;10:495–9.

Makris TK, Thomopoulos C, Papadopoulos DP, Bratsas A, Papazachou O, Massias S, et al. Association of passive smoking with masked hypertension in clinically normotensive nonsmokers. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:853–9.

Zanchetti A. Intermediate endpoints for atherosclerosis in hypertension. Blood Press Suppl. 1997;2:97–102.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Iwashima Y, Kokubo Y, Ono T, Yoshimuta Y, Kida M, Kosaka T, et al. Additive interaction of oral health disorders on risk of hypertension in a Japanese urban population: the Suita study. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:710–9.

Zelkha SA, Freilich RW, Amar S. Periodontal innate immune mechanisms relevant to atherosclerosis and obesity. Periodontol 2000. 2010;54:207–21.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Tsioufis C, Kasiakogias A, Thomopoulos C, Stefanadis C. Periodontitis and blood pressure: the concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:1–9.

Kubo M, Hata J, Doi Y, Tanizaki Y, Iida M, Kiyohara Y. Secular trends in the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke and its subtypes in Japanese population. Circulation. 2008;118:2672–8.

Sjol A, Thomsen KK, Schroll M. Secular trends in blood pressure levels in Denmark 1964–1991. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:614–22.

Kokubo Y, Kamide K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Kawanishi K, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita study. Hypertension. 2008;52:652–9.

Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke. 2004;35:776–85.

Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C. Effects of antihypertensive treatment in patients over 65 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Heart. 2014;100:317–23.

Asayama K, Thijs L, Brguljan-Hitij J, Niiranen TJ, Hozawa A, Boggia J, et al. Risk stratification by self-measured home blood pressure across categories of conventional blood pressure: a participant-level meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001591.

Bussemaker E, Hillebrand U, Hausberg M, Pavenstadt H, Oberleithner H. Pathogenesis of hypertension: interactions among sodium, potassium, and aldosterone. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1111–20.

Kokubo Y, Nakamura S, Okamura T, Yoshimasa Y, Makino H, Watanabe M, et al. Relationship between blood pressure category and incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction in an urban Japanese population with and without chronic kidney disease: the Suita study. Stroke. 2009;40:2674–9.

Kokubo Y. The mutual exacerbation of decreased kidney function and hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012;30:468–9.

Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Ono Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. The combined impact of blood pressure category and glucose abnormality on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita study. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:1238–43.

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32.

Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LC. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

Aranda P, Ruilope LM, Calvo C, Luque M, Coca A, Gil de Miguel A. Erectile dysfunction in essential arterial hypertension and effects of sildenafil: results of a Spanish national study. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:139–45.

Sharp SI, Aarsland D, Day S, Sonnesyn H, Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group, Ballard C. Hypertension is a potential risk factor for vascular dementia: systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:661–9.

Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Hirakawa Y, Yoshida D, Doi Y, Hata J, et al. Midlife and late-life blood pressure and dementia in Japanese elderly: the Hisayama study. Hypertension. 2011;58:22–8.

Thukkani AK, Bhatt DL. Renal denervation therapy for hypertension. Circulation. 2013;128:2251–4.

Myat A, Redwood SR, Qureshi AC, Thackray S, Cleland JG, Bhatt DL, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation therapy for resistant hypertension: a contemporary synopsis and future implications. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:184–97.

Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–401.

Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–62.

Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1998;317:703–13.

Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, et al. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–84.

Bangalore S, Kumar S, Lobach I, Messerli FH. Blood pressure targets in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus/impaired fasting glucose: observations from traditional and Bayesian random-effects meta-analyses of randomized trials. Circulation. 2011;123:2799–810, 2799 p following 2810.

Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, D’Agostino Sr R, Ohman EM, Rother J, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297:1197–206.

Perry Jr HM, Davis BR, Price TR, Applegate WB, Fields WS, Guralnik JM, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 2000;284:465–71.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhager WH, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–64.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–98.

American DA. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 Suppl 1:S14–80.

Hollenberg NK, Price DA, Fisher ND, Lansang MC, Perkins B, Gordon MS, et al. Glomerular hemodynamics and the renin-angiotensin system in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 2003;63:172–8.

Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles LG, Flores CA, Aros CA, et al. Renin-angiotensin system activation and interstitial inflammation in human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:(86);S64–70.

Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:1545–53.

Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Shi V, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–28.

Bakris GL, Toto RD, McCullough PA, Rocha R, Purkayastha D, Davis P, et al. Effects of different ACE inhibitor combinations on albuminuria: results of the GUARD study. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1303–9.

ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59.

Download references

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (Nos. 25293147 and 26670320), the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H26-Junkankitou [Seisaku]-Ippan-001), the Rice Health Database Maintenance industry, Tojuro Iijima Memorial Food Science, the Intramural Research Fund of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (22-4-5).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive Cardiology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 5-7-1, Fujishiro-dai, Suita, Osaka, 565-8565, Japan

Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO

Divisions of Hypertension and Nephrology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 5-7-1, Fujishiro-dai, Suita, Osaka, 565-8565, Japan

Yoshio Iwashima MD, PhD, FAHA

Division of Health Science, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Osaka, Japan

Kei Kamide MD, PhD, FAHA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Pharmacology Unit, AIMST University, Bedong, Malaysia

Pitchai Balakumar

Khin Maung-U

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Kokubo, Y., Iwashima, Y., Kamide, K. (2015). Hypertension: Introduction, Types, Causes, and Complications. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Maung-U, K. (eds) Pathophysiology and Pharmacotherapy of Cardiovascular Disease. Adis, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15961-4_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15961-4_30

Publisher Name : Adis, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-15960-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-15961-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among adults: A community based study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Meseret molla asemu.

1 School of Public Health, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Alemayehu Worku Yalew

Negussie deyessa kabeta, desalew mekonnen.

2 College of Health Science, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

In all areas of the World Health Organization, the prevalence of hypertension was highest in Africa. High blood pressure is a significant risk factor for coronary and ischemic diseases, as well as hemorrhagic stroke. However, there were scarce data concerning the magnitude and risk factors of hypertension. Thus, this study aimed to identify the prevalence and associated factors of hypertension among adults in Addis Ababa city.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from June to October 2018 in Addis Ababa city. Participants aged 18 years and older recruited using a multi-stage random sampling technique. Data were collected by face-to-face interview technique. All three WHO STEPS instruments were applied. Additionally, participants’ weight, height, waist, hip, and blood pressure (BP) were measured according to standard procedures.

Multiple logistic regressions were used and Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were also calculated to identify associated factors.

In this study, a total of 3560 participants were included.The median age was 32 years (IQR 25, 45). More than half (57.3%) of the respondents were females. Almost all (96.2%) of participants consumed vegetables and or fruits less than five times per day. Eight hundred and sixty-five (24.3%) of respondents were overweight, while 287 (8.1%) were obese. One thousand forty-one 29.24% (95% CI: 27.75–30.74) were hypertensive, of whom two-thirds (61.95%) did not know that they had hypertension.

Factors significantly associated with hypertension were age 30–49 and ≥50 years (AOR = 2.79, 95% CI: 1.39–5.56) and (AOR = 8.23, 95% CI: 4.09–16.55) respectively, being male (AOR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.18–2.99), consumed vegetables less than or equal to 3 days per week (AOR = 2.44, 95% CI: 1.21–4.93), obesity (AOR = 2.05, 95%CI: 1.13–3.71), abdominal obesity (AOR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.10–2.64) and high triglyceride level (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.38–3.07).

In Addis Ababa, around one in three adults are hypertensive. With a large proportion, unaware of their condition. We recommend integrating regular community-based screening programs as integral parts of the health promotion and disease prevention strategies. Lifestyle interventions shall target the modifiable risk factors associated with hypertension, such as weight loss and increased vegetable consumption.

Introduction

Between 1980 and 2010, the proportion of the world’s population with high blood pressure (defined as systolic and or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg) or uncontrolled hypertension had dropped modestly. However, sharp rises due to population growth and aging have been recorded across the World Health Organization (WHO) regions over the past decade, with the largest rise in Africa at 30%. The lowest prevalence of raised blood pressure was noted in the Americas region, at 18%, while the global estimate among adults aged 18 years and above was around 22% in 2014. According to the WHO estimates,Ethiopia tops at 24.4% for all adults combined [ 1 – 3 ].

High blood pressure accounts for about 13.5% of annual deaths in the world. Moreover, hypertension directly accounts for 54% of all strokes and 47% of all coronary artery disease worldwide. At the same time, the most productive segment of the population is those aged 45 to 69, who make up more than half of this burden [ 4 ].

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for coronary and ischaemic diseases as well as bleeding stroke. It has been shown that blood pressure levels are positively associated with the risk of stroke and coronary heart disease [ 5 ]. One of the most modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular diseases is hypertension. However, awareness towards the treatment and control of hypertension is extremely low among the low and middle-income counties (LMICs), including Ethiopia.On top of this, the health care resources of the LMICs are overwhelmed by other priorities, including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. As a result, many LMICs have not yet given due attention to its prevention and control [ 6 ].

In Ethiopia, non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus have begun to emerge as the leading causes of hospital admissions, morbidity, and mortality in health facilities located around the nation [ 7 ]. A 2016 report by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) found that 95% of Ethiopian adult populations have 1 to 2 risk factors for non-communicable diseases [ 8 , 9 ]. But there was little information on the extent and risk factors for hypertension at the community level in Ethiopia, including the Addis Ababa study area.

That little information was done by using the WHO stepwise tool step one and step two only [ 6 , 10 ]. And the study setting was at the facility level, though; there was a single study done at the national level using all the three World Health Organization stepwise tools [ 8 , 11 ]. Besides, the study area, Addis Ababa, is the largest urban center and capital of Ethiopia, providing approximately one-quarter of the urban population in Ethiopia [ 6 ]. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and associated factors of hypertension in the adult population of Addis Ababa using the three stepwise tools of the World Health Organization.

Study design and area

A cross-sectional community study was conducted from 1 June to 31 October 2018 in Addis Ababa City. Addis Ababa city is the capital city of Ethiopia. Administratively, Addis Ababa subdivided into ten sub-cities and 116 woredas [ 12 ]. According to the Central Statistical Agency of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, the city was projected to inhabit 3,433,999 population by 2017 [ 13 ].

Sampling techniques and sample size determination

Multi-stage cluster sampling techniques were employed by first identifying seven of the ten sub-cities based on preset criteria, including the location of the area, population density, and socioeconomic status. Then, one woreda was randomly selected from each selected sub-cities. After that, two ’ketenas’ were randomly picked from the chosen woredas, which are the smallest geographical units within woredas. Finally, for each ketena, the first household was randomly selected, while subsequent households were selected based on proximity to the first and the preceding household.

A total of 3,724 eligible adults aged 18 and over were interviewed at the selected households. The required sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula by considering: prevalence of hypertension 31.5% from a previous study done in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [ 6 ], α = 0.05 (z = 1.96), the margin of error 2%, design effect of 1.5 and 20% possible non-response rate. We also determined the sample size for the risk factors of hypertension by using two population proportion formula. But the maximum sample size was attained during the single population proportion formula. As well, the total sample size for each sub-city was determined using with probability proportional to size (PPS).

Data collection instruments and measurements

We used the adapted WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance tools. These tools have a sequential process and aim to serve as an entry point for low- and middle-income countries to monitor chronic diseases and their risk factors. All the three WHO STEPS instrument was applied to collect data on the selected information, including socio-demographic, behavioral, physical, and biochemical measurements as a part of the core and expanded modules [ 14 ]. The tools were first pretested among adults found outside the study area and, then modifications were made based on the findings.

The data were collected via face-to-face interview by trained baccalaureate nurse and laboratory technicians. Weighing scales and non stretch tape were used to measure body weight and height. Weight and height were measured as participants were standing without shoes and wearing lightweight clothing. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm; weight was recorded to the nearest 100g. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (weight (kg)/height (m 2 ) and classified as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9) and obese (≥ 30.0).

Waist circumference was measured at the level of the iliac crest using a non stretch tape measure. Hip circumference measured at the maximum circumference of the hip and; waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) calculated as a ratio of waist and hip circumference.

Physical activity was measured using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) section of the STEPS instrument, and the total physical activity is presented in MET (metabolic equivalent) minutes per week. The instrument explores three main areas of day-to-day activities: work (including domestic work), transport, and recreational activities. The level of total physical activity was subsequently classified into high, moderate, or low using the GPAQ analysis guideline provided along with the STEPS instrument [ 14 ].

Using a standardized automated blood pressure monitor, blood pressure was measured on the left arm as per the WHO protocol by informing the participants to remain seated and relaxed.Three blood pressure measurements were taken with at least 3-minute intervals between them. The mean value of the 2 nd and 3 rd measurements was used for analysis [ 14 ]. Blood pressure (BP) classified according to the Seventh Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII) [ 3 ].

To ensure the quality of the data collection, data collectors were trained by the principal investigator; and later on, daily checks were carried out by field supervisors and the principal investigator. The weight of the participants, measured on a pre-calibrated electronic scale. Weighing scales checked and zero levels adjusted between measurements; we also placed the scale on a firm flat surface. The blood pressure was measured in a seated position by a digital device (OMRON M2 Eco). The instrument has been clinically approved and recommended by the World Health Organization. In addition, WHO’s STEPwise tools have been previously validated and implemented in mainly developing countries, including Ethiopia [ 6 , 8 ].

Operational definitions

Hypertension : defined as a mean measured blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg systolic and/or the mean measured diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg or self-reported history of hypertension.

Body Mass Index (BMI) : calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (weight (kg)/height (m 2 ). BMI was categorized as per the World Health Organization guidelines [ 14 ], underweight (BMI <18.5), normal (BMI ≥18.5 to ≤ 24.9), overweight (BMI ≥ 25.0 to ≤ 29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30.0).

Waist to hip ratio : calculated as waist circumference in cm divided by hip circumference in cm and it was used as a measure of abdominal obesity. Waist to hip ratio ≥ 0.90 m in men and ≥ 0.85m in women is defined as having abdominal obesity [ 15 ].

High physical activity: a person reaching any of the following criteria is classified in this category:

- Vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days achieving a minimum of at least 1,500 MET-minutes/week OR

- 7 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate- or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of at least 3,000 MET-minutes per week.

Moderate physical activity: a person not meeting the criteria for the "high" category, but meeting any of the following criteria is classified in this category:

- 3 or more days of vigorous-intensity activity of at least 20 minutes per day

- 5 or more days of moderate-intensity activity or walking of at least 30 minutes per day OR

- 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate- or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of at least 600 MET-minutes per week.

Low physical activity: a person not meeting any of the above mentioned criteria under moderate or high physical activities falls in this category.

Raised fasting blood glucose was defined as capillary whole blood value ≥110 mg/dl.

Raised total cholesterol was defined as total blood cholesterol level ≥190mg/dl.

Raised triglyceride was defined as raised triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dl.

Data analysis

Double data entry procedures were performed using the EpiData 3.1 statistical software, and analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version23. Binary logistical regression was used to identify risk factors for hypertension. Initially, possible risk factors were assessed using bivariate analyses; then we did the multivariable logistic regression model to control confounding factors, and statistical significance was accepted when the P-value < 0.05. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was used to evaluate whether or not the assumptions necessary for the application of multiple logistic regression are met. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were computed.

Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the city government of Addis Ababa Health Bureau Ethical Review Committee (ERC). A letter of permission was obtained from the selected sub-city health offices. Respondents were fully informed about the purpose of the study and gave verbal and written consent. Participants having high blood pressure, high blood glucose level, and or abnormal lipid profiles during the study period were referred and informed to go to nearby health facilities for further diagnosis and management.

Results and discussion

Description of the study participants.

From the total 3724 sampled population, consent was given to the 3560 participants to involve in step one and two questionnaires, making an overall response rate of 95.59%. Using a random sampling technique, 582 (20%) of the study participants who participated in the interview and physical measurements were selected for the step three questionnaires (biochemical assessment).

Respondents were between 18 and 95 years old and, the median age was 32 years old (IQR 25, 45). More than half (57.3%) of the respondents were females. The majority (74.8%) were Orthodox Christians, followed by Muslims (14.9%). Above one-third (37%) of them were self-employed, while nearly a half (49.6%) were currently married ( Table 1 ).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 1520 | 42.7 |

| Female | 2040 | 57.3 |

| Orthodox | 2664 | 74.8 |

| Muslim | 530 | 14.9 |

| Protestant | 333 | 9.4 |

| Catholic | 14 | 0.4 |

| Other | 19 | 0.6 |

| Government employee | 388 | 10.9 |

| Non-government employee | 257 | 7.2 |

| Self employed | 1316 | 37.0 |

| Student | 301 | 8.5 |

| House wife | 750 | 21.1 |

| Daily laborer | 83 | 2.3 |

| Merchant | 69 | 1.9 |

| Unemployed(able to work) | 173 | 4.9 |

| Unemployed(unable to work) | 47 | 1.3 |

| Retired (pensioner) | 176 | 5.0 |

| 18–29 | 1508 | 42.4 |

| 30–49 | 1304 | 36.6 |

| 50 and above (50–95) | 748 | 21.0 |

| 1–4 | 2178 | 61.2 |

| ≥5 | 1382 | 38.8 |

| Never married | 1331 | 37.4 |

| Currently married | 1767 | 49.6 |

| Separated | 49 | 1.4 |

| Divorced | 139 | 3.9 |

| Widowed | 271 | 7.6 |

| Non response | 3 | 0.1 |

| Primary | 1176 | 33.0 |

| Secondary | 719 | 20.2 |

| Preparatory | 464 | 13.0 |

| Technique | 67 | 1.9 |

| College and above | 539 | 15.1 |

| Not attended formal education | 595 | 16.7 |

Behavioral risk factors of the study participants

Tobacco use.

Tobacco use was assessed by interviewing respondents about their current smoking status, previous smoking experience, the age they started smoking, and exposure to second-hand smoke. Overall, about 4.2% (150) of survey respondents were current smokers (daily smokers and non-daily smokers) ( Table 2 ). Of these, a majority (88.66%) smoke cigarettes on daily basis, with an average of 10 cigarettes per day. More than three-fourth 136 (90.66%) of current smokers were male compared to female (p < 0.001). The average age at which smokers started smoking was 21 ± 6.58 years. Fifty-five (1.61 percent) have smoked cigarettes in the past. One hundred nineteen (3.4%) were passive smokers or second-hand smokers.

| Characteristics | Number | Percent | Hypertension (%, CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 1508 | 42.4 | 12.86 (11.17–14.56) |

| 30–49 | 1304 | 36.6 | 31.29 (28.77–33.81) |

| ≥50 | 748 | 21.0 | 58.69 (55.15–62.23) |

| Yes | 150 | 4.2 | 34.67 (26.96–42.37) |

| No | 3410 | 95.8 | 29.00 (27.48–30.53) |

| Yes | 330 | 9.3 | 31.2 (26.19–36.24) |

| No | 3229 | 90.7 | 29.0 (27.45–30.58) |

| Yes | 1162 | 32.6 | 32.79 (30.09–35.49) |

| No | 2397 | 67.4 | 27.53 (25.74–29.32) |

| None | 1107 | 31.1 | 34.24 (31.44–37.04) |

| 1–3 days | 2126 | 59.7 | 27.19 (25.29–29.08) |

| 4–7 days | 266 | 7.5 | 24.81 (19.59–30.04) |

| Don’t know | 61 | 1.7 | 29.51 (17.73–41.29) |

| None | 530 | 14.9 | 30.19 (26.27–34.11) |

| 1–3 days | 2549 | 71.6 | 29.23 (27.46–30.99) |

| 4–7 days | 448 | 12.6 | 28.57 (24.37–32.77) |

| Don’t know | 33 | 0.9 | 24.24 (8.81–39.67) |

| Yes | 542 | 15.2 | 21.77 (18.29–25.26) |

| No | 3018 | 84.8 | 30.58 (28.94–32.23) |

| Yes | 986 | 27.7 | 30.53 (27.65–33.41) |

| No | 2574 | 72.3 | 28.75 (27.00–30.50) |

| Yes | 51 | 8.5 | 58.82 (44.84–72.80) |

| No | 551 | 91.5 | 37.57 (33.51–41.62) |

| Yes | 255 | 43.8 | 49.80 (43.63–55.98) |

| No | 327 | 56.2 | 31.50 (26.44–36.56) |

| Yes | 241 | 41.4 | 54.36 (48.02–60.69) |

| No | 341 | 58.6 | 29.03 (24.19–33.87) |

| Yes | 718 | 20.2 | 38.30 (34.74–41.87) |

| No | 2714 | 76.2 | 26.46 (24.79–28.12) |

| Don’t know | 128 | 3.6 | 37.50 (29.00–46.00) |

Khat chewing

There were 330 (9.3%) participants who reported chewing khat ( Table 2 ). Over a third of the respondents, 105 (31.53%) and half, 172 (51.65%) chew khat on a daily and weekly basis, respectively. On the other hand, 153 participants (4.3%) had previously chewed khat.

Alcohol consumption

One thousand one hundred sixty-two (32.6%) participants consumed alcohol and of that 783 (22.0%) consumed alcohol during the last month ( Table 2 ). Binge drinking is defined; as consuming alcohol for men five and above, or women four and above drink on one occasion and, the result showed that 269 (7.6%) of men and 81 (2.3%) of women binge drunker.

Dietary habits of the study participants

Two thousand three hundred ninety-two (67.2%) consumed fruits, at least one time per week, and the mean fruit consumption per week was 2.12 (±1.48) days, as well, the majority 2268 (94.77%) ate fruit 1–2 serving per day with a mean of 1.36 (±0.58) times per day. Similarly, more than three forth 2997 (84.2%) of the participants ate vegetables at least one time per week with a mean of 2.46 (± 1.46) per week, and most of them 2827 (94.33%) ate it 1–2 times per day with mean serving time per day was 1.55 (±0.61). Nearly three fourth 2511 (70.6%) of respondents reported that they usually use vegetable oils like Nug (Guizotia Abyssinica), Sesame, and Sunflower oil for meal preparation, while nearly one-fourth 839 (23.6%) use a vegetable oil which was solid at room temperature. Nearly all 3423 participants (96.2%) consumed vegetables and fruits less than five times a day.

Physical activity

The total median physical activity of the respondents was 7440 (IQR 2888, 12240) and, the median total physical activity (TPA, in MET-minutes per week) was estimated to be 7800 (IQR 3000, 14280) in males and 7200 (2880, 11320) in females. Approximately 29.5% of males and 4.6% of females were; categorized as having a high (vigorous) level of TPA. However, significantly more women (36.4%) than men (16.0%) classified as having low levels of TPA (P < 0.001). In addition, most of the study participants, 3198 (89.8%), walked or cycled for a minimum of 10 minutes per day.

Physiological characteristics of the study participants

Body mass index and waist to hip ratio.

Weight and height measured in all participants at 3560; the average BMI for respondents was 23.54 (±4.39 kg/m 2 ). Eight hundred and sixty-five (24.3%) were overweight, while 287 (8.1%) were obese. Moreover, the average hip-waist ratio was 0.88 (±0.086 m 2 )) with 0.89 (± 0.086 m 2 ) and 0.87 (±0.085 m 2 ) for men and women, respectively. Over two-thirds of females (67.06%) and 32.9% of males had abdominal obesity.

Biochemical measurements of the respondents

Of the total number of participants, the blood sample was collected from 582 participants (20 percent). The average FBS was 86.7 (±36.2 mg/dl), and the prevalence of high blood sugar, high cholesterol, and triglycerides was 8.5%, 43.8%, and 41.4%, respectively ( Table 2 ).

Prevalence of hypertension

Three consecutive blood pressure measurements took from 3,560 respondents (95.16%) and; an average of the second and third measurements used for blood pressure analysis. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure of the respondents was 125.03 (95% CI: 124.39–125.62) mm Hg and 79.58 (95% CI: 79.8–79.97) mm Hg, respectively. The mean SBP was 126.95 (95% CI: 126.03–127.87) mmHg among males and 123.59 (95% CI: 122.72–124.47) mmHg among females. Likewise, the mean DBP was 80.76 (95% CI: 80.14–81.38) mm Hg in males and 78.69 (95% CI: 78.17–79.21) mm Hg in females. Both mean SBP (P < 0.001) and DBP (P < 0.001) were significantly higher in men compared to women.

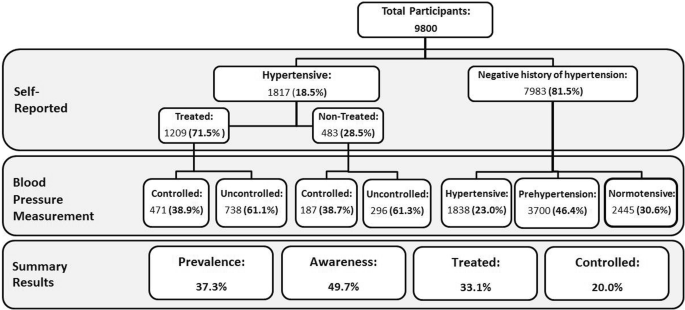

The overall prevalence of hypertension was 29.24% (95% CI: 27.75–30.74), slightly higher among men 30.13 (95% CI: 27.82–32.44) than women 28.58 (95% CI: 26.66–30.54). Of the 1041 hypertensive respondents, 645 (61.95%) had just been diagnosed in the survey (new screening).

Factors associated with hypertension

Multivariable logistic regression analysis found that of several non-modifiable factors, age and gender were associated with hypertension. The odds of hypertension increased with increased age. The odds of hypertension increased almost three times AOR = 2.79 (95% CI: 1.39–5.56) among respondents aged 30–49 years, and it was eight times AOR = 8.23 (95% CI: 4.09–16.55) higher among respondents aged 50 years and above as compared to those 18–22 years old. The odds of hypertension were almost twice as high AOR = 1.88 (95% CI: 1.18–2.99) in men compared with women.

From modifiable and other factors, eating fewer vegetables per week, body mass index, abdominal obesity, and high triglycerides levels were associated with hypertension. The odds of hypertension increased more than two times AOR = 2.44 (95% CI: 1.21–4.93) among respondents who consumed vegetable less than or equal to three days per week compared to those who ate more than three days per week.

The chance of hypertension reduced by 73% among underweight participants AOR = 0.27 (95% CI: 0.07–0.97), but the odds were two times higher AOR = 2.05 (95%CI: 1.13–3.71) among obese participants as compared to those having normal BMI. Moreover, the odds of hypertension was almost two times higher AOR = 1.70 (95% CI: 1.10–2.64) among participants with abdominal obesity as compared to their counterparts.

The odds of hypertension was also increased by two AOR = 2.06 (95% CI: 1.38–3.07) among participants who had high triglyceride level as compared to their counterparts.

The odds of hypertension was also increased by two AOR = 2.06 (95% CI: 1.38–3.07) in participants with high triglyceride level compared to their counterparts. In this particular study, risky behaviors, including alcohol use, vigorous physical activity, family history of hypertension or diabetes, high blood sugar, and high cholesterol level not significantly associated with hypertension ( Table 3 ).

| Variable | Hypertension | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| 18–29 | 194 | 1314 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 30–49 | 408 | 896 | 3.08 (2.55–3.73) | 2.79 (1.39–5.56)* | 0.003 |

| ≥50 | 439 | 309 | 9.62(7.80–11.87) | 8.23 (4.09–16.55)** | < 0.001 |

| Female | 538 | 1457 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 458 | 1062 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | 1.88 (1.18–2.99)* | 0.004 |

| Primary | 334 | 842 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 2 & preparatory | 304 | 879 | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 1.03 (0.58–1.80) | 0.66 |

| Technique & college | 142 | 464 | 0.77 (0.62–0.97) | 0.97 (0.49–1.89) | 0.94 |

| Unable to read & write | 261 | 334 | 1.97 (1.60–2.42) | 1.10 (0.64–1.88) | 0.65 |

| No | 660 | 1737 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 381 | 781 | 1.28 (1.10–1.49) | 1.35 (0.87–2.09) | 0.34 |

| No | 923 | 2095 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 118 | 424 | 0.62 (0.51–0.79) | 1.05 (0.51–2.15) | 0.88 |

| Yes | 848 | 2142 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| No | 169 | 300 | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) | 1.02 (0.59–1.78) | 0.93 |

| Yes | 718 | 1996 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| No | 275 | 443 | 0.58 (0.48–0.69) | 0.73 (0.45–1.19) | 0.34 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 504 | 1539 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| <18.5 | 48 | 319 | 0.46 (0.33–0.63) | 0.27 (0.07–0.97)* | 0.036 |

| 25–29.9 | 341 | 519 | 2.01 (1.69–2.34) | 1.48 (0.95–2.32) | 0.072 |

| ≥ 30 | 145 | 139 | 3.19 (2.47–4.10) | 2.05 (1.13–3.71)* | 0.011 |

| No | 350 | 1308 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 691 | 1211 | 2.13 (1.84–2.48) | 1.70 (1.10–2.64)* | 0.026 |

| No (< 110 mg/dL) | 207 | 344 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes (≥ 110 mg/dL) | 30 | 21 | 2.37 (1.32–4.27) | 0.943 (0.35–2.54) | 0.74 |

| No (<190 mg/dL) | 103 | 224 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes (≥ 190 mg/dL) | 127 | 128 | 2.158 (1.54–3.03) | 0.92 (0.46–1.86) | 0.48 |

| No (<150 mg/dL) | 99 | 242 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes (≥ 150 mg/dL) | 131 | 110 | 2.91 (2.06–4.11) | 2.06 (1.38–3.07)** | < 0.001 |

| >3 days | 128 | 320 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ≤ 3 days | 905 | 2174 | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) | 2.44 (1.21–4.93)* | 0.009 |

P-value < 0.05 * and <0.000**, (backward logistic regression method was employed).

The study found that approximately one in three adults aged 18 and over is hypertensive. During childhood, there are modest facts about a gender change in blood pressure. However, beginning with youth, males tend to have a higher average level. But later in life, the difference gets smaller, and the pattern can even be changed [ 16 ]. The prevalence of hypertension in the current study is slightly higher among men than women, which is comparable; a community-based study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, reported prevalence of hypertension was 31.5% and 28.9% among males and females, respectively [ 6 ]. Moreover, this study is also comparable with other community-based studies conducted in Jalalabad, Afghanistan (28.4), Kenya (29.4%), Uganda (30.5%), and Gondar city (28.3%) [ 10 , 17 – 19 ].

The prevalence of hypertension in this study is considerably higher as compared to other studies Bangladesh (16.0%), Eritrea (16.4%), Addis Ababa (25%), Bahir Dar (25.1%), Durame Southern Ethiopia (22.4%), Gilgel Gibe South West Ethiopia (5.8%) and Mekelle (20.1%) [ 11 , 20 – 25 ]. The difference may be explained by the age differences of the surveyed populations (18 years and above in our case, whereas in the other studies, the age of the participants varies between 15 and 64 years). Differences may also be attributed to the diversity of sociodemographic characteristics, sample size, lifestyle, and dietary patterns of the study participants.

On the contrary, the prevalence of hypertension in our study is lower than other similar community-based studies conducted in South Africa (38.9%), Sudan (35.7%), Nigeria (33.1%) and Cameroon (47.5%) [ 26 – 29 ]. This disparity can be due to variations in race, genetics, and prevalence of obesity (higher among others), all of which are likely to influence blood pressure.

From non-modifiable risk factors, age is one of the risk factors of hypertension proved by many studies; there is a positive association between age and hypertension when age increases, the odds of hypertension also increases [ 6 , 10 , 11 , 17 , 18 , 21 , 24 , 26 ]. It is primarily due to the increase in systolic blood pressure with age, mainly due to the reduction in elasticity (increased stiffness) of large duct arteries [ 30 ]. Inthe same vein, this study, this study found out that respondents aged 30–49 years had 3 times higher odds of hypertension, and 8 fold higher odds among participants aged 50 and above. In terms of gender, the prevalence of hypertension was almost two times higher in males compared to females in the current study, which is consistent with other study findings [ 11 , 22 , 25 , 28 ].

According to the World Health Organization, overweight and obesity are a major risk factor for heart disease, including high blood pressure, which is the number one cause of death [ 31 ]. In our study, the odds of hypertension were two times higher among obese participants compared to those with normal body mass index; however, the chances of hypertension were reduced by 73% among underweight participants. This finding (especially the obese category) was in line with previous reports from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Bangladesh, and Cameroon [ 10 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 32 ], and this showed that obesity is one of the risk factor associated with hypertension almost all studies. Moreover, the odds of hypertension were two times higher among abdominally obese respondents compared to their counterparts, the result is also consistent with other studies [ 27 , 28 , 33 , 34 ].

Hypertriglyceridemia is a powerful predictor of cardiovascular disease, which causes endothelial damage, and loss of physiological vasomotor activity that results from endothelial damage can occur in the form of high blood pressure [ 35 ]. In our study, having a high triglyceride level was independently associated with hypertension. The odds of hypertension increased by two among participants with high triglyceride levels relative to their counterparts; our findings are consistent with those of others [ 33 , 36 ].

Previous studies done so far suggested that use of alcohol, cigarette smoking, Khat use, literacy level, physical activity, raised fasting glucose level, family history of hypertension, family history of diabetes, and excessive salt use were significantly associated with hypertension. In contradiction, in this study, the above variables were not significantly associated with hypertension [ 4 , 17 , 18 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 37 ]. A contradicting finding was noted in this current study where all the above variables showed no significant association with hypertension.The inconsistency in these results may be due to the variation of sample size, study settings, and population characteristics. These variations may also be explained by the research design issues (as a cross-sectional design can’t distinguish the sequences of explanatory variables and the outcome). The other element of this study included adults 18 years of age or older, but different studies used a different age class, which should make comparisons difficult. Additionally, the respondents might not know whether they had a family history of hypertension or not due to the silent killer and asymptomatic nature of the diseases this may underestimate the risk factors of the disease. Though, we use the standardized WHO STEPs risk factor questionnaire allows for comparability on the presence of risk factors between various communities, regions, and countries.

There was a high prevalence of hypertension among adults in the city of Addis Ababa, which may indicate a hidden epidemic in the population. Even though the study was conducted in the capital city, there was a large proportion of hypertensive respondents (61.95%) were unaware of having the condition and newly screened for the first time by the current study. Increasing age, gender being male, obesity and abdominal obesity, consumption of low vegetables, and raised triglyceride levels were significantly associated with hypertension.

As a result, lifestyle changes and the introduction of obesity and hypertension screening programs are recommended. These programs should focus on lifestyle changes, including eating fruits and vegetables, maintaining a normal weight, and weight loss intervention. The findings also underscore the vital need for community-based screening programs for the early detection of hypertension and obesity.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the following organizations and individuals for contributing to the success of this study: The authors wish to extend their most sincere thanks to all participants in the study. We thank the data collectors and supervisors. We also want to convey our deepest gratitude to Armed Forces Comprehensive Specialized Hospital because they allowed us to do all the lipid profiles with their laboratory technicians.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2021; 16(4): e0248934.

Decision Letter 0

21 Dec 2020

PONE-D-20-26679

Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among adults: a Community Based Study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Dear Dr. MESERET MOLLA ASEMU,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

As you will recognize from the comments of the reviewers both raised major points of critique, especially regarding design of the study and presentation of data.

Please submit your revised manuscript within 2 months. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Rudolf Kirchmair

Academic Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. We suggest you thoroughly copyedit your manuscript for language usage, spelling, and grammar. If you do not know anyone who can help you do this, you may wish to consider employing a professional scientific editing service.

Whilst you may use any professional scientific editing service of your choice, PLOS has partnered with both American Journal Experts (AJE) and Editage to provide discounted services to PLOS authors. Both organizations have experience helping authors meet PLOS guidelines and can provide language editing, translation, manuscript formatting, and figure formatting to ensure your manuscript meets our submission guidelines. To take advantage of our partnership with AJE, visit the AJE website ( http://learn.aje.com/plos/ ) for a 15% discount off AJE services. To take advantage of our partnership with Editage, visit the Editage website ( www.editage.com ) and enter referral code PLOSEDIT for a 15% discount off Editage services. If the PLOS editorial team finds any language issues in text that either AJE or Editage has edited, the service provider will re-edit the text for free.

Upon resubmission, please provide the following:

- The name of the colleague or the details of the professional service that edited your manuscript

- A copy of your manuscript showing your changes by either highlighting them or using track changes (uploaded as a *supporting information* file)

- A clean copy of the edited manuscript (uploaded as the new *manuscript* file)

3. Please include additional information regarding the survey or questionnaire used in the study and ensure that you have provided sufficient details that others could replicate the analyses. For instance, if you developed a questionnaire as part of this study and it is not under a copyright more restrictive than CC-BY, please include a copy, in both the original language and English, as Supporting Information.

4. In the Methods, please discuss whether and how the questionnaire was validated and/or pre-tested. If this did not occur, please provide the rationale for not doing so.

5. We note that you have stated that you will provide repository information for your data at acceptance. Should your manuscript be accepted for publication, we will hold it until you provide the relevant accession numbers or DOIs necessary to access your data. If you wish to make changes to your Data Availability statement, please describe these changes in your cover letter and we will update your Data Availability statement to reflect the information you provide.

6. PLOS requires an ORCID iD for the corresponding author in Editorial Manager on papers submitted after December 6th, 2016. Please ensure that you have an ORCID iD and that it is validated in Editorial Manager. To do this, go to ‘Update my Information’ (in the upper left-hand corner of the main menu), and click on the Fetch/Validate link next to the ORCID field. This will take you to the ORCID site and allow you to create a new iD or authenticate a pre-existing iD in Editorial Manager. Please see the following video for instructions on linking an ORCID iD to your Editorial Manager account: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xcclfuvtxQ

7. Thank you for submitting the above manuscript to PLOS ONE. During our internal evaluation of the manuscript, we found significant text overlap between your submission and the following previously published works, some of which you are an author.

https://bmccardiovascdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2261-12-113

https://ejcm.journals.ekb.eg/article_11046_f56232e3d004cc38fe78b7b616f2799e.pdf

https://www.scribd.com/doc/115910728/Ncd-Report-Full-en-English

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2736927/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12889-015-2610-8?code=241bf12b-10c4-493b-805c-c06d7a2cbf80

We would like to make you aware that copying extracts from previous publications, especially outside the methods section, word-for-word is unacceptable. In addition, the reproduction of text from published reports has implications for the copyright that may apply to the publications.

Please revise the manuscript to rephrase the duplicated text, cite your sources, and provide details as to how the current manuscript advances on previous work. Please note that further consideration is dependent on the submission of a manuscript that addresses these concerns about the overlap in text with published work.

We will carefully review your manuscript upon resubmission, so please ensure that your revision is thorough.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Partly

Reviewer #2: Yes

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #1: No

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #1: Yes

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: Line 71- Which are the "Non Communicable Diseases risk factors?

Line 164- Why p-value of < 0.20 was used as criteria to include it in the multivariable logistic

regression model?

Quite a small group of the study population were smokers in this study- can you explain why?

It is recommended that the diagnosis of hypertension should be based on:

repeated office BP measurements on more than one visit in the ESC-guidelines from 2018-

in this study the definition hypertension was defined on just one visit. Is the definition of hypertension chooses too weakly in this study?

Reviewer #2: Manuscript ID number:

Title of paper:

Despite careful approach to investigate Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension, manuscript needs minor revisions to make it easy to understand before being published.

General comments:

1. Language editing strongly recommended

2. The body of the text suffers from several spelling and grammatical errors. Please consider a professional language edit. Example: scare (page 3 first paragraph),

3. Standardized your tables by removing the boarders and include P values in table 3

4. In the abstract result section, almost all (96.2%) of participants consume vegetables and or fruits less than five times per day.

Is that feasible consuming vegetable & fruits five times per day in Ethiopian context? Or you mean five times per week? Make it clear

Page 3 & 4

5. Moreover, in Ethiopia non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus appear on the list of leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the hospitals and regional health bureaus across the country. A report by Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) in 2016 showed that 95% of the Ethiopian adult populations have 1-2 Non-Communicable Diseases risk factors (6, 7). But, there were scare data with regard to the magnitude and risk factors of common non communicable disease at the community level in Ethiopia including the study area Addis Ababa. Moreover, the study area represents the largest urban center in Ethiopia, hosting about 25% of the urban population in the country (5).

Since you are not intended to study all types of non-communicable diseases better to focus on hypertension). Paragraph 4, page 3 needs both language & grammatical edition.

6. The method section, selection of the study participant,

the last paragraph a total of 3724 all needs to reconsider again

7. A community based cross-sectional study was conducted from June to October 2018 in Addis.

Please provide more precise date of study begin and termination

8. Multi-stage cluster sampling techniques was employed. Seven of the ten sub-cities were selected purposefully by considering the area that was found, the population density and the economic activities.

You didn’t say anything about how you determine the sample size. How you calculate your sample size, what assumptions you used to calculate your sample size both for the magnitude & factors. Also, important you should show us how you allocate the number of participants to Sub-cities or Woreda Or Kebeles, Ketenas & households?

9. One of the methods of maintaining the quality of data is keeping the data collection instrument valid & reliable (in you case weight scale & BP apparatus, the STEPS Questionnaire). In this regard you didn’t say anything.

How you maintain the reliability & validity of this instruments? We need more clarification on this issue

10. In the description of the study participants, result section, you calculate both the mean with SD and Median with IQR for the respondents’ age.

What was the reason and which one was appropriate for your data? Need clarification

11. In Tobacco use section to told us about 4.2% (150), of the survey participants were current smokers (daily and non-daily smokers) again in the last two sentence of the same section you presented, fifty-five (1.61%) were ever smoked cigarettes and One hundred nineteen (3.4%) were passive smoking or second-hand smoke.

What does this imply? Are these 55 peoples being among 150 who currently smoke? Needs to be clarified.

12. Weight and height measurement were taken from all participants 3560 and the BMI was calculated for those participants. But you didn’t show how you calculate the BMI (only you defined BMI in the operational definition).

It is important to show how was the BMI calculated in the methods section. The procedure you used needs to be clearly kept in the method section

13. You told us that blood sample was collected from 20% of the total study participants.

It is not sufficient to write 20% of total you need to write the actual number of participants you collect blood sample.

14. In the result section, prevalence of hypertensin, you presented the overall prevalence of hypertension was 29.24% (95% CI: 27.75-30.74), slightly higher among men 30.13 (95% CI: 27.82-32.44), than women 28.58 (95% CI: 26.66-30.54) even though the difference was not statistically significant (χ2=1.015, P= 0.314).

But in the factors associated with you stated that sex had significant association with hypertension (The odds of hypertension was almost two times higher AOR= 1.88 (95% CI: 1.18-2.99) among males as compared to females). Needs clarification and reconsideration.

Page 19 discussion section

15. Hypertension is an important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). It currently accounts for about 13.5% of annual global deaths. Hypertension is directly responsible for 54% of all strokes and 47% of all coronary heart disease worldwide. Moreover, over half of this burden occurs in individuals aged 45–69 years, which is the most productive segment of the population (31).

Better to start your discussion by summary of your results and good if you use this in the introduction section

16. …………. So, the prevalence of hypertension in the current study is slightly higher among men than women which is comparable with a community based study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia which reported the prevalence of hypertension was 31.5% and 28.9% among males and females, respectively (5). Moreover, this study is also comparable with other community-based studies conducted in Jalalabad, Afghanistan (28.4), Kenya (29.4%), Uganda 375 (30.5%), and Gondar city (28.3%) (12-15).

Here first you talk about the association between hypertension and gender or sex and on the next paragraph back to compare the prevalence with other studies. I see some confusion here I think you would want to change the order of the paragraph?

17. ……… which the risk of hypertension increases with age. This is mainly due to systolic blood pressure increase with age, mainly because of reduced elasticity (increased stiffness) of the large conduit arteries (26). In this study respondents aged 30-49 years; had 3 times higher risk of hypertension and even moreover, it is 8 times higher risk among participants aged 50 years and above.

What is your message here for the patients and health care providers you provide? Is there anything that recommend to tackle this problem or age? You should better to emphasize on modifiable factors than non-modifiable like age & sex. Need your consideration

18. This finding (especially obese category) was in line with previous reports from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Bangladesh, and Cameroon (13, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27). Moreover, the risk of hypertension was 2 times higher among abdominally obese respondents and this finding is in line with other studies (24, 25, 28, 29) and the same to the level of triglyceride also.

Since this is the most important area that your recommendation is focused, comparing the findings is not sufficient. Better to find the reason of similarity or differences and give your recommendation or message based on that. Therefore, you need to work on it and put your recommendation.

Page 21, first paragraph

19. In contradiction, in this study the above variables were not significantly associated with hypertension. The inconsistency of these findings may be due to the low prevalence of these factors in the community especially among females.

What does it mean? I don’t think your reason for differences is correct. May you need to find tangible reason for this difference.

20. Additionally, the respondents might not know whether they had a family history of hypertension or diabetes due to the silent killer nature of the diseases this may underestimate the prevalence of the diseases.

How the silent killer nature of the disease affects the prevalence of hypertension since the prevalence was determined by measuring their blood pressure? Or you want to say the severity of the disease? Not clear

Do you think diabetes is a silent killer? Since your objectives did not include diabetes why you include here?

21. The other reason should since some of the information was based on self-report and is subjected to social desirability and recall biases.

These issues are very critical in research. How you manage this social desirability and recall biases since this can affect severely your findings? You have to show us either in the discussion or method section how you control theses biases clearly? In addition, with all these short comings or limitations do think your research could be eligible for publication? Better to avoid those limitations that can be controlled methodologically

22. In the conclusion section …. There was a high prevalence of hypertension among adults in the Addis Ababa city and this may show a hidden epidemic in the population. What is your reference to say high prevalence or to conclude this is a hidden epidemic? You have to show here

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy .

Reviewer #2: No

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/ . PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif . Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Submitted filename: Manuscript ID number.docx

Author response to Decision Letter 0

A rebuttal letter

Manuscript PONE-D-20-26679

Response to Reviewers

Dear Rudolf Kirchmair,

Thank you for the opportunity to provide a revised version of the manuscript. “Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among adults: a Community Based Study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia” for publication in PLOS ONE Journal. We appreciate the time and effort you and the examiners put into providing comments on our manuscript. We have incorporated the suggestions and comments made by the reviewers. These changes are highlighted in the manuscript. A point-by-point response to the reviewers’ comments and concerns is provided below in blue.

• A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

• A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

• An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols

Authors’ response: Dear academic editor, thank you for providing the link. We carefully read and edited our manuscript as per the guidelines.

2. We suggest you thoroughly copyedit your manuscript for language usage, spelling, and grammar. If you do not know anyone who can help you do this, you may wish to consider employing a professional scientific editing service.

Whilst you may use any professional scientific editing service of your choice, PLOS has partnered with both American Journal Experts (AJE) and Editage to provide discounted services to PLOS authors. Both organizations have experience helping authors meet PLOS guidelines and can provide language editing, translation, manuscript formatting, and figure formatting to ensure your manuscript meets our submission guidelines. To take advantage of our partnership with AJE, visit the AJE website ( http://learn.aje.com/plos/ ) for a 15% discount off AJE services. To take advantage of our partnership with Editage, visit the Editage website ( www.editage.com ) and enter referral code PLOSEDIT for a 15% discount off Editage services. If the PLOS editorial team finds any language issues in text that either AJE or Editage has edited, the service provider will re-edit the text for free.

• The name of the colleague or the details of the professional service that edited your manuscript

• A copy of your manuscript showing your changes by either highlighting them or using track changes (uploaded as a *supporting information* file)

• A clean copy of the edited manuscript (uploaded as the new *manuscript* file)