Stay up to date on consumer trends by opting into our newsletter.

Ask a Free Question

We just need a little info to track your question and ensure you get the results back!

Meet them where they are. How mobile research gets you closer to consumers.

We’ve all felt the shift.

The economy, largely driven by consumer spending, has impacted buying behavior.

As research professionals, that’s exactly what we study. Change. We rely on consumers to tell us what they’re thinking, how they’re buying, and why they’re making certain decisions.

Our jobs depend on the insights we receive. So, what do we do when the climate in which our consumer buy, changes?

We change too.

- Using mobile research.

In 2017, a research crisis was declared 1 .

People were concerned. The most common ways to collect insights, weren’t working the way that they used to. Specifically, there were issues with:

- Door-to-door surveys: Expensive, intrusive 2

- Paper and pen surveys: Slow, and hard to review 3

- Telephone surveys: Less than 6% answer 4

- Online surveys: Only 49% of respondents were satisfied 5

Enter mobile research.

Today, a whopping 81% of the U.S. owns a smartphone 6 . And they spend more than three hours a day on their phones. That’s an easy-to-reach, collective and representative audience.

The idea behind mobile research is to use smartphones to reach consumers. It isn’t tied down by in-person interviews, landlines, or hardline computers. It moves with the people you study. As such, it eliminates virtually all the issues that our industry is used to, addressed above.

Case Study: Cell phone carrier .

A major cellphone brand was in a tough scenario.

They were tracking consumers to their stores, but struggling to get a complete picture of the people likely to buy their brand. Specifically, they couldn’t get an accurate sample of:

- Young people

- Hispanic Americans

Using any of the four methods above.

Missing a majority of their target market meant a higher incidence rating, and higher costs. It also meant that they had to ask detailed questions to identify the make, model and carrier of people they could reach. Collectively, their challenges limited the accuracy of the research.

Here’s how they solved the problem: They switched to a mobile research tracker. Like a typical brand tracker, this research continued to follow their consumers. Yet, now they had the ability to open up the panel to 81% of the U.S. population who owns a smartphone.

This meant that the brand could now access 10 million daily consumer journeys via a market research app. They were able to meet their target market needs, find out exactly what make, model and carrier participants had – without asking – and increase their incidence rating.

With a mobile app, they are also tracking online and app behavior.

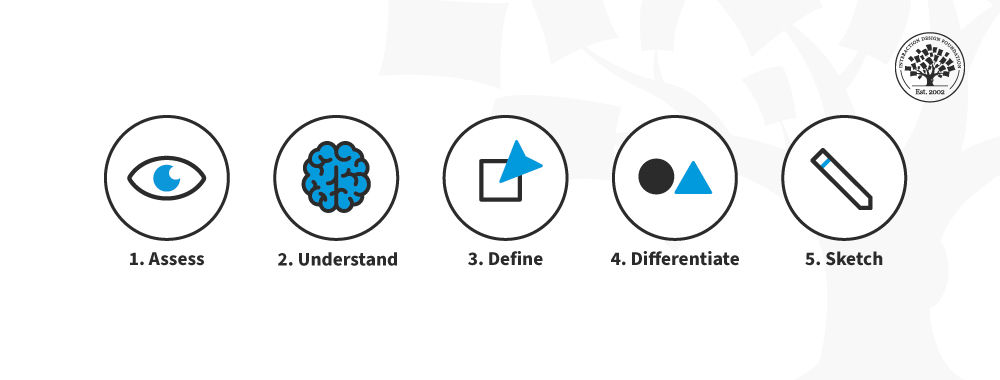

How mobile research works :

Here’s how mobile market research works, in detail. And the three things you need to make it work for your research projects.

- Identify the need.

- Pick your audience.

- Add behavioral data.

We’ll take a look at each one, together, to get you comfortable with the platform as a whole.

- #1: Identify the need.

Any good research project starts with a goal in mind.

Mobile research is no different. It’s simply a weapon of choice, focused on acquiring accurate data and insights. So, you’ll start in the same way you always do, with a simple question:

What is the goal of this study?

With that in mind, you can craft a compelling questionnaire (QRE) alone, or with a research provider. Either way, your questioning should be designed to meet that primary goal.

Example: COVID-19 need .

In the wake of COVID-19, consumer spending shifted.

In order to understand the impact, we decided to research buying behavior. The goal was to track the purchases of essential, versus non-essential, items at big-box retailers.

We expected the virus to reduce non-essential spending. On the other hand, we expected food and toiletries would increase, as consumers prepared for a possible quarantine. Not wanting to rely on the questionnaire alone, we chose to leverage behavioral data as well.

We’ll share more about behavioral research, which is unique to mobile, in section 3.

- #2: Pick your audience.

In mobile research, your audience lives in an app.

That app is how you connect with consumers’ smartphones. When consumers download the app, they’re sent a survey, asking for their demographic data.

Example demographics include:

- Relationship status

- And more than 200+ other pieces of data

All of their data points are stored in the app. This gives you, the researcher, a great degree of flexibility to profile your ideal target audience. You choose exactly who to include as a panelist.

Example: COVID-19 panel .

We needed men and women 18+.

The app gave us 1,133 participants: split 48% male, 52% female. The primary age was 18-44 years old. Participants were screened on knowledge of Coronavirus and a retailer visit within 30 days. Stated data was collected with a 13-question survey via the Surveys On The Go® app.

We fielded and collected data in as little as two hours. The speed with which you can conduct mobile research is powerful. Full projects can be completed within a 24-hour period.

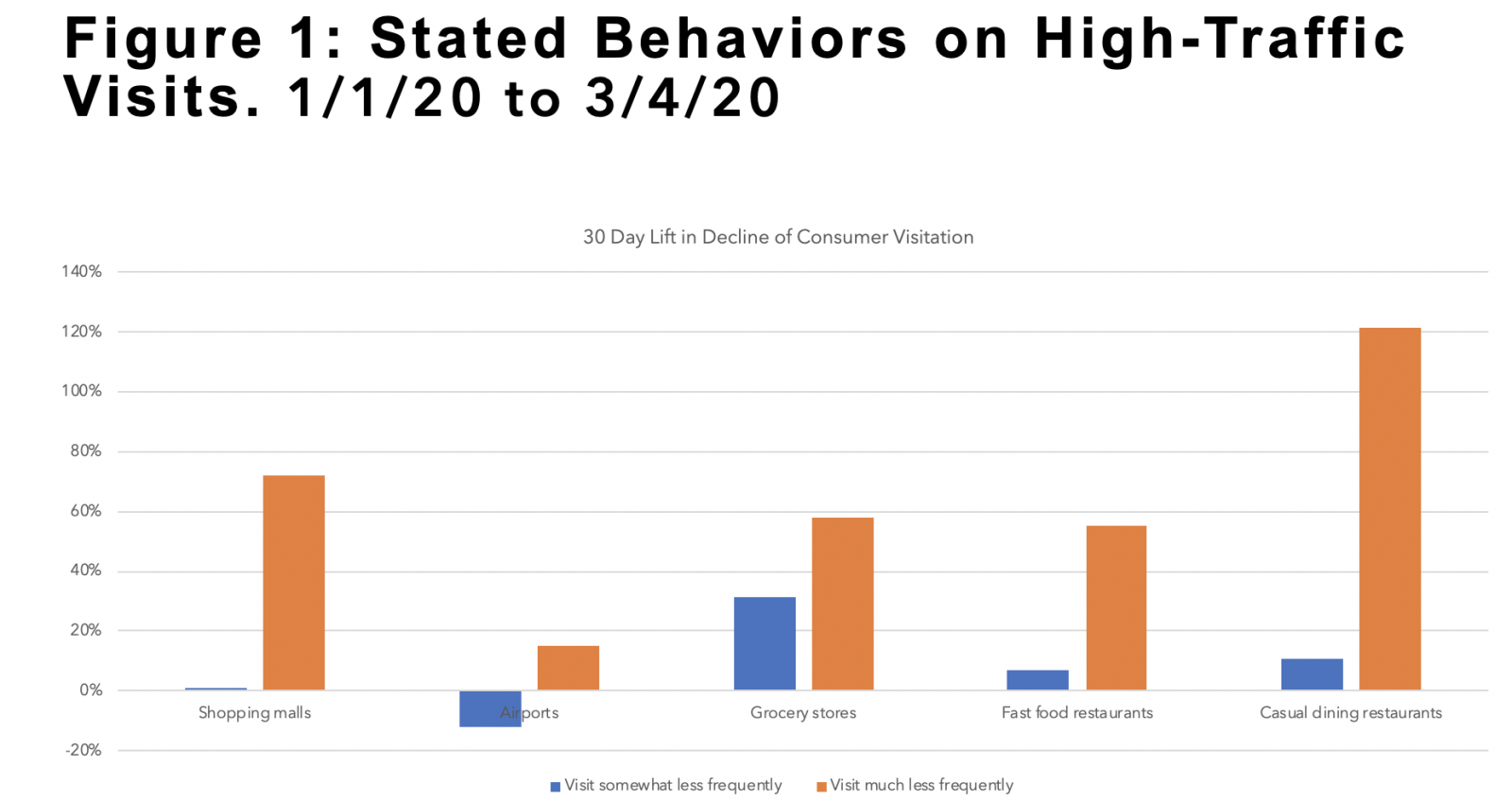

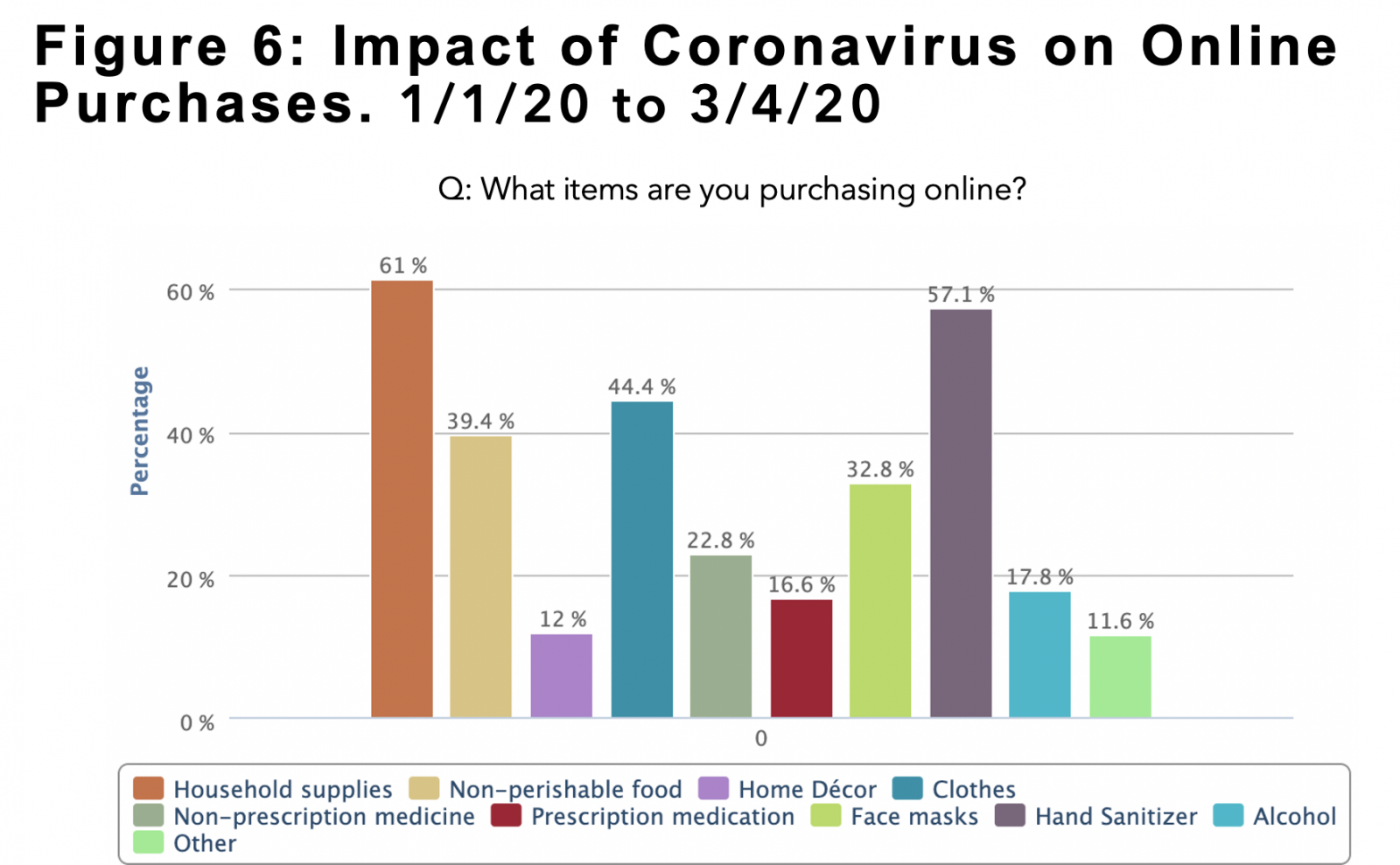

Here are examples of the stated behaviors they shared.

Figure 1 & 2: percent change was used to calculate increase/decrease from February to March waves.

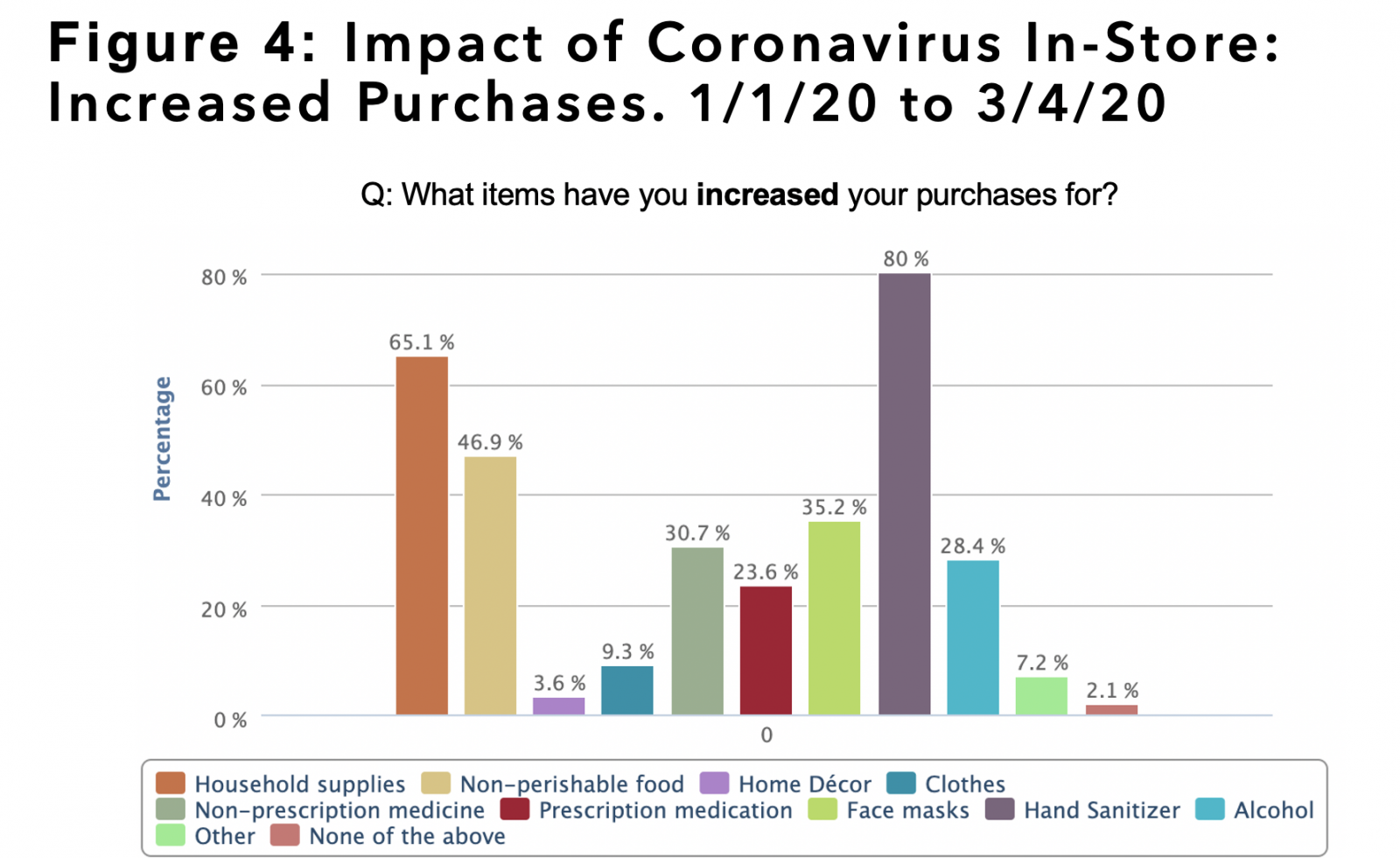

We see that consumers stocking up for a quarantine.

This shows in increased purchases in hand sanitizer (80%), household supplies (65%), nonperishable foods (49%), and face masks (35%). Generally, respondents are preparing for 2 to 4 weeks, which explains the buying shift at big box retailers, where they can buy in bulk.

- #3: Add behavioral data.

The real difference in mobile research: behavioral data.

Behavior-driven research is the ability to see what consumers do, rather than rely on stated data alone. The reason it’s so important is that it eliminates fraud and recall bias in one step 7 .

Consumers can’t remember everything. So, if we only ask them to state their behavior, and they can’t really remember what they did, it puts the entire project at risk for being inaccurate 8 .

Mobile research has a solution.

Here, the research is being done on an app.

That app is connected to GPS on the smartphone. When a consumer moves, the app knows it. And the app can now send a survey to that consumer in real-time, right as they’re walking into (or out of) a location, interacting with an app, or doing an online activity.

That’s behavioral research.

Example: COVID-19 behavioral data .

Here’s an example of behavioral research with COVID-19.

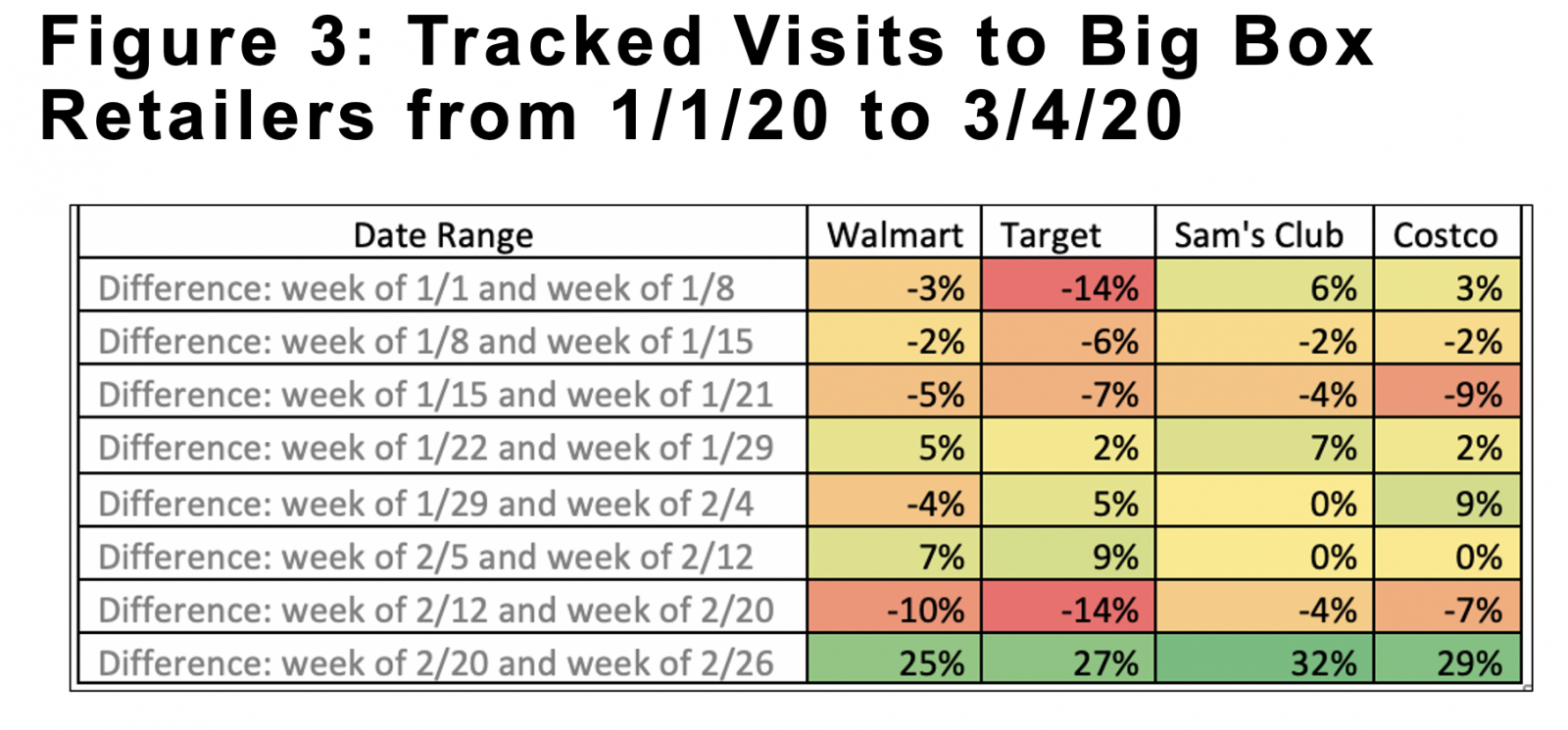

We tracked total visits to Walmart, Target, Sam’s Club and Costco.

Each participant was GeoValidated through GPS using the Surveys On The Go® app. A visit was defined as going a listed retailer from January 1 st , 2020 to March 4 th , 2020. Visits were tracked week over week.

Here’s their behavioral data.

Figure 3: percent change was used to calculate increase/decrease from week over week from 1/1 through 2/26.

Stated and behavioral data, together, shows us a massive shift in consumer spending.

Once COVID-19 was declared a pandemic 9 there was up to a 32% lift in visits to big-box retailers. When combined with the stated data, we’re given a very detailed picture. Consumers are very clearly preparing for a potential quarantine.

They’re looking to buy essentials in bulk.

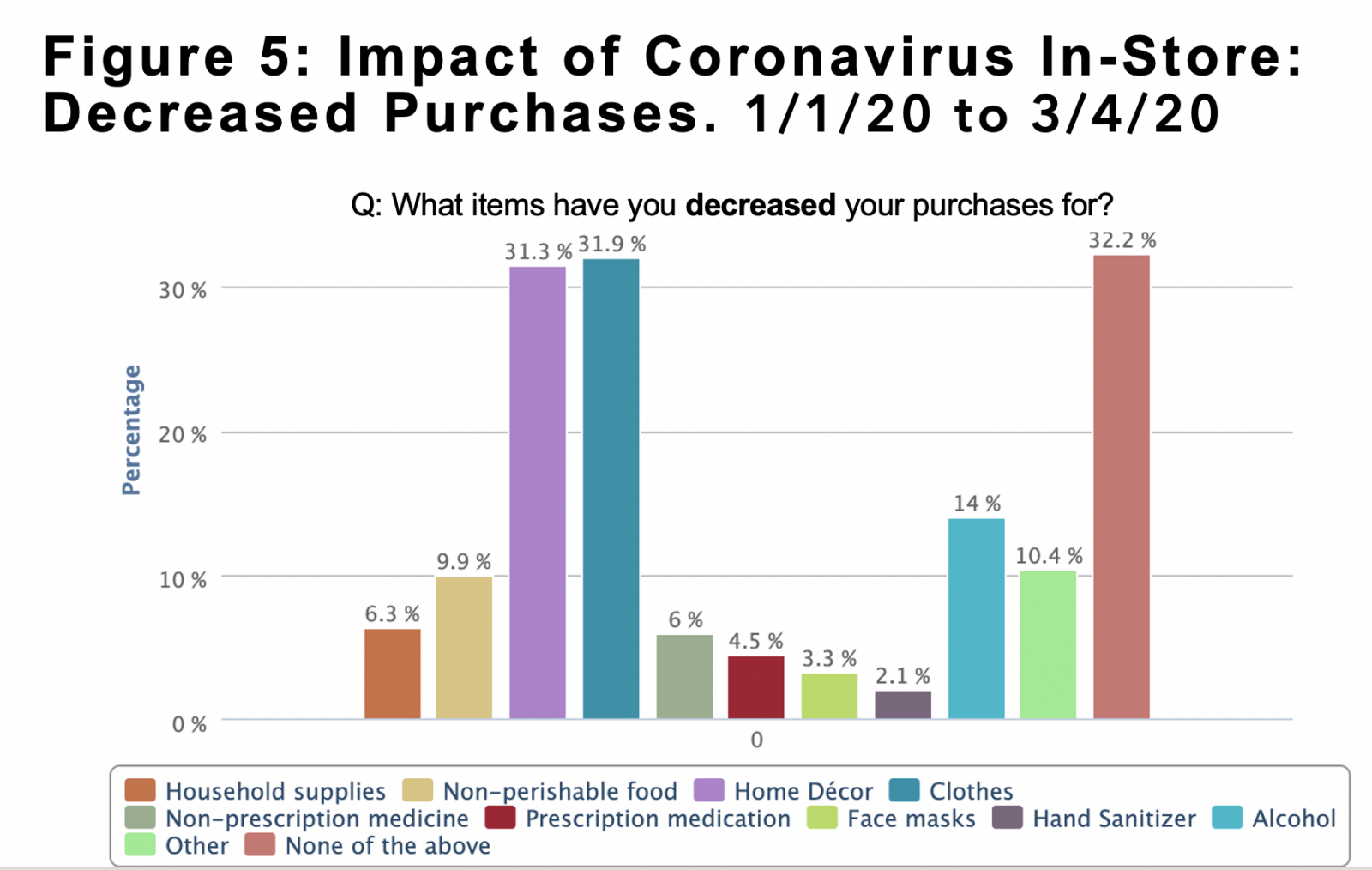

At the same time, in-store purchases decreased in home décor (31%) and clothes (32%).

We’d expect consumers to decrease non-essential in-store spend as they focus on food and supplies, if they believe they’re about to quarantine.

What’s interesting, is that we still see non-essentials being bought. Consumers are just buying them online, instead of in-store. There’s a 46% increase. We see this in Figure 5 below.

Hearing, and seeing consumer behavior – in one place – is powerful.

Stated surveys allow us to tap into the voice of the customer, but behavioral data gives the credence we need to be sure our research picture is accurate. This is only possible with mobile research, which has the technology to paint the full picture for researchers in the field.

- Final thoughts.

Market research is personal.

We’re in the business of working with real people. And we need to get even more personal if we want to improve the result of our research. It’s not enough to base important business decisions on guessing who consumers are, what they want, or why they want it.

To do that, we need to be talking to real people in real-time.

That’s what mobile research does. And that’s why is forging a new union between behavioral and survey data. You now have the power to track real consumers historically and in real-time.

Mobile research brings big data, consumer journeys, and survey data: into one.

It’s a single home for reaching a representative, first-party consumer panel. The result is more powerful than any tool we’ve had before. It’s consumer understanding based on reality. And we’re excited to see our industry continue to expand, and benefit from, the latest technology.

References:

- https://3905270.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/3905270/ebook/P2P_eBook_2018_FINAL_print.pdf

- Corey & Freeman, 1990; Taylor, Wilson, & Wakefield, 1998

- Peter Ward Taralyn Clark Ramon Zabriskie, 2014

- https://www.politico.com/story/2019/02/27/phone-polling-crisis-1191637

- https://go.mfour.com/hubfs/ebook/P2P_eBook_2018_FINAL_print.pdf

- https://mfour.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/How-to-Predict-Future-Behavior-and-Impact-Revenue-Guide.pdf?utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_hk7DDSUuhjnH-aDfP-hnglZDUyMUIeEUr13sXC78yAVezW6XTVoYpffVu2p0NYzz4wzCH

- https://mfour.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/How-to-Predict-Future-Behavior-and-Impact-Revenue-Guide.pdf?utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&_hsenc=p2ANqtz–pkXkynKZZOGnpcNMS9Xb4Setr_lnsbufV8knul76gpy7NXRGhibH5uXHcubNrwJ2XTg29

- https://go.mfour.com/blog/flawed-recall-means-fractured-data-use-geolocation-to-solve-memory-decay

- https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/10/dow-futures-point-to-a-loss-of-more-than-400-points-after-tuesdays-surge.html

By Allyson Wehn

Reviewed by Cathy Karcher

Posted on May 6th, 2020

Learn more about vTracker+™

- Case Study: Cell phone carrier.

Explore More Posts

Why customer experience tracking is important for business growth.

Today, customer experience (CX) has emerged as a key differentiator for businesses. The modern consumer...

What is the customer satisfaction index? Strategies for enhanced consumer loyalty and satisfaction.

Understanding and Improving Customer Satisfaction Index Are you striving to improve your customer satisfaction index?...

Unleashing the power of brand tracking: How to stay ahead in the digital landscape.

In today’s hyper-competitive digital landscape, staying ahead of the competition is a constant challenge. Brands...

Stay in Touch

Three Great Examples of Mobile Research in Action

In order to tailor their offerings to rapidly changing consumer preferences and to maintain an edge, organisations are increasingly looking for new ways to tap into real-time customer insights. While staying ahead of this trend is creating new challenges for researchers the advent of mobile technology is also opening up new opportunities for savvy companies.

Mobile research isn’t limited to sending out SMS surveys – the most forward-thinking organisations are taking mobile-based research technology to new heights with some innovative projects. From Facebook and QR code integration to track which products customers ‘like’ most, to advanced location-based mobile feedback, these examples should provide inspiration for any organisation wanting to dig into insightful and timely consumer intelligence.

In this edition of Mobile Matters, we take a look at three innovative case studies of mobile research in action – be sure to have a read through and see if any of these could be implemented in your own company’s research efforts.

1. Out-of-box experiences

You’ve likely seen them before: user-generated videos of customers unboxing their new gadgets live on camera and recording the experience. These first impressions a customer has of a new product can offer immensely valuable insight for a business – but is there a cohesive way of collecting this feedback?

‘Out-of-box’ experience surveys are a great way for companies to gauge these reactions. A simple card placed within the box, complete with a QR code that instantly opens up the survey, means you give customers the opportunity to log their initial product experiences and feedback at the vital stage of their interaction with you.

It’s like being right there by the customer’s side as they open their purchase and express their raw and authentic impressions of the initial experience. This is as close and as timely as it gets – no more waiting for the customer to log on days later to provide feedback and ideas to improve, by which time their recall may not be as sharp.

2. QR code and social media integration

Social media is now an integral part of many consumers’ personal lives – so why not use the opportunity to gain consumer insight in an engaging manner?

The ease of doing so was demonstrated in a well-executed marketing campaign by fashion label Diesel. The company took the Facebook concept of ‘liking’ straight into the real world, setting up targeted QR codes next to each of their denim products. A shopper in a physical Diesel store could scan the code of a product they liked, and in the process, instantly share their preferences on their Facebook wall.

Not only is this a great way to spread rapid word-of-mouth marketing through social media, it’s a powerful method of collecting real-time, in-store feedback on customer preferences, providing the ability to determine which products are the most popular at any given time.

3. Location-based feedback

Location-based mobile feedback technologies are on the rise, offering businesses an innovative way to measure customer feedback based on their physical locations. According to ABI Research, the market for retail indoor location technologies is set to reach AUD$5.4 billion by 2018.

Technologies such as this can assist companies that want more in-the-moment feedback. In the example mentioned above, location-based feedback could act as an extension to Diesel’s retail QR code campaign. For example, triggering a mobile survey about a reward program member’s in-store experiences as soon as they are 25 metres or more away from your store.

The Coca-Cola Village Amusement Park in Israel showed how effective this can be, especially for younger demographics. Visitors to the park were issued with personalised RFID (Radio-frequency identification) bracelets that were embedded with their Facebook details. Each ride at the park had a reader which visitors simply had to swipe with their bracelets to express their ‘like’ for the particular amusement, with their preferences again being broadcast on Facebook.

With RFID technologies growing in uptake and the use of products such as Apple’s new internet connected watch set to explode, this sort of real-time customer insight could be worth looking into – imagine the possible applications if it is transferred into retail stores.

Mobile technologies are evolving at faster rates than ever before, introducing countless new opportunities for organisations to conduct mobile research with their customers. As these examples above demonstrate, they can be a great way to tap into your customers’ insights in real-time, gaining incredibly rich, accurate and relevant information.

Happy surveying!

Ready to run to your next research project?

We’d love to speak with you to see if we can assist with your next mobile research project – please give us a call on +61 2 9232 0172 and ask for an obligation-free quote from one of our Business Solutions team members. Alternatively, drop us a note .

We have helped over 1,000 organisations to utilise feedback as a means to improve employee engagement and increase customer satisfaction and referrals. And now we’d love to help you!

Phone us on +61 2 9232 0172 or submit your demo request today via the form below:

Software Proudly Developed Hosted & Supported: From Australia

- PeoplePulse, an ELMO solution.

- Head office: Level 27, 580 George St, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

- +61 2 9232 0172

Call us on +61 2 9232 0172 to discuss your Employee/Customer Survey needs, and for a free, no-obligation online demo. Press 1 for sales and ask to speak with a PeoplePulse representative. Alternatively, please click on “REQUEST DEMO” below:

Request Demo

Mobile Methodologies: Theory, Technology and Practice

- September 2008

- Geography Compass 2(5):1266 - 1285

- Cynidr Consulting

- The University of Manchester

- University of Birmingham

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- J TRANSP GEOGR

- Yongcheng Wang

- Eric Siu-kei Cheng

- Rebecca Solnit

- GEOGR ANN B

- T. Hagerstrand

- Geraldine Pratt

- Edward W. Soja

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Mobile Market Research: What Is It, and Why Should You Do It?

Discover the advantages of mobile market research and learn effective strategies for gathering valuable consumer insights in today's mobile-driven world.

Aishwarya N K

June 27, 2023

.png)

In this Article

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

AI-generated article summary

- Quota sampling divides a target population into subgroups and sets specific targets for the number of respondents from each subgroup

- It's a non-random sampling method that's useful when researchers need to ensure representation from different demographics or characteristics.

- Use quota sampling when you want to gather data quickly and cheaply while ensuring representation from important subgroups within your target audience.

Get fast AI summaries of customer calls and feedback with magic summarize in Decode

In today's digital age, mobile market research has emerged as a powerful tool for gaining valuable consumer insights. With the widespread use of mobile devices, researchers now have the opportunity to tap into a larger and more diverse participant pool, gather real-time data, and engage with participants on their terms. The benefits of conducting mobile market research are extensive, but it is crucial to keep certain tips in mind to maximize the effectiveness of your mobile research efforts. In this article, we will explore the benefits of mobile market research and provide practical tips for conducting successful studies tailored to the realm of consumer research.

What is mobile market research?

Mobile market research refers to the use of mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, as a platform for conducting market research activities. It leverages the widespread usage and capabilities of mobile technology to gather consumer insights, collect data, and conduct surveys or studies.

The use of mobile market research has been growing rapidly due to the increasing ubiquity of mobile devices and the convenience they offer. Researchers and businesses can take advantage of mobile market research to gain a deeper understanding of their target audience, conduct research in real-world contexts, and make data-driven decisions that align with the evolving consumer landscape.

What are the benefits of conducting mobile market research?

Access to a larger and more diverse participant pool.

Mobile devices have become ubiquitous, allowing researchers to reach a larger and more diverse audience. This means you can gather insights from different demographics, geographical locations, and socioeconomic backgrounds, providing a broader representation of your target market.

Real-time data collection

Mobile market research allows for real-time data collection, enabling researchers to capture insights as they happen. Participants can provide feedback, opinions, or complete surveys instantly using their mobile devices, eliminating delays associated with traditional methods like paper surveys or face-to-face interviews. For instance, a fashion retailer can conduct a real-time mobile survey during a fashion show to gather immediate feedback on runway designs, ensuring timely and relevant data for decision-making.

Convenience and flexibility for participants

Mobile research offers convenience to participants as they can engage in surveys or studies at their own convenience. They can respond to surveys anytime, anywhere, making it easier for them to participate and increasing the likelihood of higher response rates. Mobile research also accommodates participants' busy schedules and provides flexibility in completing tasks. For instance, a consumer electronics company conducting mobile research can leverage GPS data to understand the locations where consumers interact with their products, helping them tailor marketing strategies to specific regions or target local preferences.

Enhanced data accuracy

Mobile devices often come equipped with features like GPS, cameras, and sensors that can provide more accurate and contextual data. Researchers can leverage these features to capture location-based information, multimedia responses, or track participant behaviors, resulting in richer and more precise data.

Improved engagement and interactivity

Mobile market research leverages the interactive capabilities of mobile devices, such as touchscreens and multimedia support. Researchers can incorporate engaging elements like videos, images, and interactive question formats, making the research experience more enjoyable and interactive for participants. This can lead to higher participant engagement and better-quality responses. For example, a cosmetics brand can include interactive product demos or virtual makeup try-ons in their mobile research study, allowing participants to engage with the brand and provide feedback on their preferences in a more interactive way.

Cost-effectiveness

Mobile research can be more cost-effective compared to traditional methods. It eliminates the need for printing and distributing paper surveys, hiring interviewers, or renting physical research facilities. With mobile devices, researchers can conduct studies remotely, reducing logistical costs and potentially reaching a larger sample size within a given budget. For instance, a fast-food chain can use mobile surveys to collect feedback on customer satisfaction, saving costs on printing and manually entering survey data into a system.

Rich data collection methods

Mobile devices support various data collection methods beyond surveys, such as passive data collection, mobile diaries, and in-app tracking. These methods provide researchers with in-depth insights into consumer behaviors, preferences, and usage patterns, offering a more holistic understanding of the target market.

Faster data analysis

Mobile market research often involves digital data collection, which can be automatically stored and processed. Researchers can use data analysis tools and software to quickly analyze and derive insights from the collected data, reducing the time and effort required for manual data entry and analysis.

Tips to keep in mind while conducting mobile market research

Make the surveys mobile-friendly.

Design surveys that are optimized for mobile devices, ensuring they are visually appealing, easy to navigate, and responsive to different screen sizes. Keep the questions concise and precise, and use mobile-friendly response formats like checkboxes or sliders.

Read more: How to Conduct a Survey For Actionable Consumer Insights

Keep it short and engaging

Mobile users have limited attention spans, so keep the surveys or research activities short and engaging. Break down longer surveys into smaller, more manageable sections to maintain participant interest and reduce abandonment.

Include multimedia content

Mobile devices support various multimedia formats, so consider integrating visual and audio elements into your research activities. This can include image-based questions, video feedback, or audio recordings to capture rich and detailed insights.

Conduct usability testing on mobile devices

Conduct usability testing specifically on mobile devices to evaluate the user experience of your mobile app or website. Test navigation, responsiveness, and overall usability to identify areas for improvement.

Consider data security and privacy

Respect mobile users' privacy and ensure data security throughout the research process. Obtain informed consent, anonymize data, and adhere to relevant data protection regulations to build trust with participants.

Make sure to test across multiple devices

Ensure your research activities are compatible with various mobile devices and operating systems. Test on different devices, screen sizes, and platforms to ensure a consistent user experience across the mobile landscape.

Focus on continuous testing

Mobile market research should be an ongoing process rather than a one-time event. Regularly collect data, monitor trends, and gather feedback to stay updated with evolving consumer behaviors and preferences in the mobile space.

Conducting mobile market research with Decode

Mobile market research has revolutionized the way businesses can gather insights about their consumers. By leveraging the benefits it offers, researchers can unlock a wealth of valuable information that can shape strategic decisions and drive business growth.

Decode allows you to conduct qualitative and quantitative market research with ease on mobile devices. Decode is an integrated DIY consumer research platform which uses patented technologies such as Eye Tracking, Facial Coding, and Voice AI to get real-time insights into customer feedback and insights. With Decode, you can gain deeper insights into consumer behaviors, preferences, and usage patterns, enabling you to make informed decisions that resonate with your target audience and drive your business forward in the dynamic mobile landscape.

{{cta-button}}

Frequently Asked Questions

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

With lots of unique blocks, you can easily build a page without coding.

Click on Study templates

Start from scratch

Add blocks to the content

Saving the Template

Publish the Template

Aishwarya tries to be a meticulous writer who dots her i’s and crosses her t’s. She brings the same diligence while curating the best restaurants in Bangalore. When she is not dreaming about her next scuba dive, she can be found evangelizing the Lord of the Rings to everyone in earshot.

Senior Product Marketing Specialist

Related Articles

Top AI Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top AI events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top Insights Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top Insights events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top CX Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top CX events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

How to Build an Experience Map: A Complete Guide

An experience map is essential for businesses, as it highlights the customer journey, uncovering insights to improve user experiences and address pain points. Read to find more!

Everything You Need to Know about Intelligent Scoring

Are you curious about Intelligent Scoring and how it differs from regular scoring? Discover its applications and benefits. Read on to learn more!

Qualitative Research Methods and Its Advantages In Modern User Research

Discover how to leverage qualitative research methods, including moderated sessions, to gain deep user insights and enhance your product and UX decisions.

The 10 Best Customer Experience Platforms to Transform Your CX

Explore the top 10 CX platforms to revolutionize customer interactions, enhance satisfaction, and drive business growth.

TAM SAM SOM: What It Means and How to Calculate It?

Understanding TAM, SAM, SOM helps businesses gauge market potential. Learn their definitions and how to calculate them for better business decisions and strategy.

Understanding Likert Scales: Advantages, Limitations, and Questions

Using Likert scales can help you understand how your customers view and rate your product. Here's how you can use them to get the feedback you need.

Mastering the 80/20 Rule to Transform User Research

Find out how the Pareto Principle can optimize your user research processes and lead to more impactful results with the help of AI.

Understanding Consumer Psychology: The Science Behind What Makes Us Buy

Gain a comprehensive understanding of consumer psychology and learn how to apply these insights to inform your research and strategies.

A Guide to Website Footers: Best Design Practices & Examples

Explore the importance of website footers, design best practices, and how to optimize them using UX research for enhanced user engagement and navigation.

Customer Effort Score: Definition, Examples, Tips

A great customer score can lead to dedicated, engaged customers who can end up being loyal advocates of your brand. Here's what you need to know about it.

How to Detect and Address User Pain Points for Better Engagement

Understanding user pain points can help you provide a seamless user experiences that makes your users come back for more. Here's what you need to know about it.

What is Quota Sampling? Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use It?

Discover Quota Sampling: Learn its process, types, and benefits for accurate consumer insights and informed marketing decisions. Perfect for researchers and brand marketers!

What Is Accessibility Testing? A Comprehensive Guide

Ensure inclusivity and compliance with accessibility standards through thorough testing. Improve user experience and mitigate legal risks. Learn more.

Maximizing Your Research Efficiency with AI Transcriptions

Explore how AI transcription can transform your market research by delivering precise and rapid insights from audio and video recordings.

Understanding the False Consensus Effect: How to Manage it

The false consensus effect can cause incorrect assumptions and ultimately, the wrong conclusions. Here's how you can overcome it.

5 Banking Customer Experience Trends to Watch Out for in 2024

Discover the top 5 banking customer experience trends to watch out for in 2024. Stay ahead in the evolving financial landscape.

The Ultimate Guide to Regression Analysis: Definition, Types, Usage & Advantages

Master Regression Analysis: Learn types, uses & benefits in consumer research for precise insights & strategic decisions.

EyeQuant Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best eyequant alternative to improve user experience and an AI-powered solution for all your user research needs.

EyeSee Alternative

Embrace the Insights AI revolution: Meet Decode, your innovative solution for consumer insights, offering a compelling alternative to EyeSee.

Skeuomorphism in UX Design: Is It Dead?

Skeuomorphism in UX design creates intuitive interfaces using familiar real-world visuals to help users easily understand digital products. Do you know how?

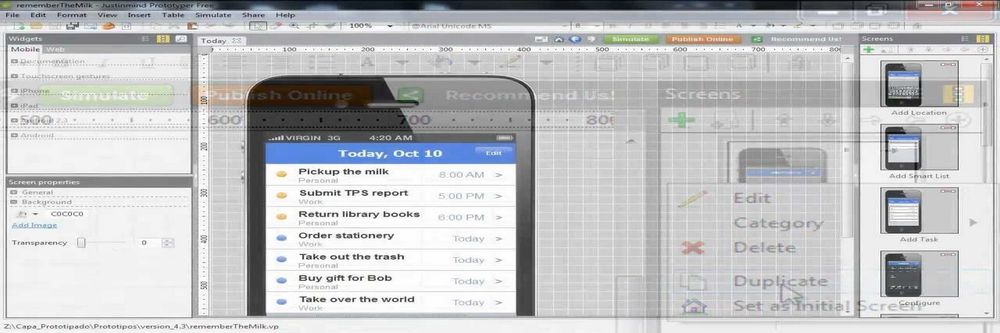

Top 6 Wireframe Tools and Ways to Test Your Designs

Wireframe tools assist designers in planning and visualizing the layout of their websites. Look through this list of wireframing tools to find the one that suits you best.

Revolutionizing Customer Interaction: The Power of Conversational AI

Conversational AI enhances customer service across various industries, offering intelligent, context-aware interactions that drive efficiency and satisfaction. Here's how.

User Story Mapping: A Powerful Tool for User-Centered Product Development

Learn about user story mapping and how it can be used for successful product development with this blog.

What is Research Hypothesis: Definition, Types, and How to Develop

Read the blog to learn how a research hypothesis provides a clear and focused direction for a study and helps formulate research questions.

Understanding Customer Retention: How to Keep Your Customers Coming Back

Understanding customer retention is key to building a successful brand that has repeat, loyal customers. Here's what you need to know about it.

Demographic Segmentation: How Brands Can Use it to Improve Marketing Strategies

Read this blog to learn what demographic segmentation means, its importance, and how it can be used by brands.

Mastering Product Positioning: A UX Researcher's Guide

Read this blog to understand why brands should have a well-defined product positioning and how it affects the overall business.

Discrete Vs. Continuous Data: Everything You Need To Know

Explore the differences between discrete and continuous data and their impact on business decisions and customer insights.

50+ Employee Engagement Survey Questions

Understand how an employee engagement survey provides insights into employee satisfaction and motivation, directly impacting productivity and retention.

What is Experimental Research: Definition, Types & Examples

Understand how experimental research enables researchers to confidently identify causal relationships between variables and validate findings, enhancing credibility.

A Guide to Interaction Design

Interaction design can help you create engaging and intuitive user experiences, improving usability and satisfaction through effective design principles. Here's how.

Exploring the Benefits of Stratified Sampling

Understanding stratified sampling can improve research accuracy by ensuring diverse representation across key subgroups. Here's how.

A Guide to Voice Recognition in Enhancing UX Research

Learn the importance of using voice recognition technology in user research for enhanced user feedback and insights.

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook: Design Creation and Testing

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook covers setting up Figma, creating designs, advanced features, prototyping, and testing designs with real users.

The Power of Organization: Mastering Information Architectures

Understanding the art of information architectures can enhance user experiences by organizing and structuring digital content effectively, making information easy to find and navigate. Here's how.

Convenience Sampling: Examples, Benefits, and When To Use It

Read the blog to understand how convenience sampling allows for quick and easy data collection with minimal cost and effort.

What is Critical Thinking, and How Can it be Used in Consumer Research?

Learn how critical thinking enhances consumer research and discover how Decode's AI-driven platform revolutionizes data analysis and insights.

How Business Intelligence Tools Transform User Research & Product Management

This blog explains how Business Intelligence (BI) tools can transform user research and product management by providing data-driven insights for better decision-making.

What is Face Validity? Definition, Guide and Examples

Read this blog to explore face validity, its importance, and the advantages of using it in market research.

What is Customer Lifetime Value, and How To Calculate It?

Read this blog to understand how Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) can help your business optimize marketing efforts, improve customer retention, and increase profitability.

Systematic Sampling: Definition, Examples, and Types

Explore how systematic sampling helps researchers by providing a structured method to select representative samples from larger populations, ensuring efficiency and reducing bias.

Understanding Selection Bias: A Guide

Selection bias can affect the type of respondents you choose for the study and ultimately the quality of responses you receive. Here’s all you need to know about it.

A Guide to Designing an Effective Product Strategy

Read this blog to explore why a well-defined product strategy is required for brands while developing or refining a product.

A Guide to Minimum Viable Product (MVP) in UX: Definition, Strategies, and Examples

Discover what an MVP is, why it's crucial in UX, strategies for creating one, and real-world examples from top companies like Dropbox and Airbnb.

Asking Close Ended Questions: A Guide

Asking the right close ended questions is they key to getting quantitiative data from your users. Her's how you should do it.

Creating Website Mockups: Your Ultimate Guide to Effective Design

Read this blog to learn website mockups- tools, examples and how to create an impactful website design.

Understanding Your Target Market And Its Importance In Consumer Research

Read this blog to learn about the importance of creating products and services to suit the needs of your target audience.

What Is a Go-To-Market Strategy And How to Create One?

Check out this blog to learn how a go-to-market strategy helps businesses enter markets smoothly, attract more customers, and stand out from competitors.

What is Confirmation Bias in Consumer Research?

Learn how confirmation bias affects consumer research, its types, impacts, and practical tips to avoid it for more accurate and reliable insights.

Market Penetration: The Key to Business Success

Understanding market penetration is key to cracking the code to sustained business growth and competitive advantage in any industry. Here's all you need to know about it.

How to Create an Effective User Interface

Having a simple, clear user interface helps your users find what they really want, improving the user experience. Here's how you can achieve it.

Product Differentiation and What It Means for Your Business

Discover how product differentiation helps businesses stand out with unique features, innovative designs, and exceptional customer experiences.

What is Ethnographic Research? Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand Ethnographic research, its relevance in today’s business landscape and how you can leverage it for your business.

Product Roadmap: The 2024 Guide [with Examples]

Read this blog to understand how a product roadmap can align stakeholders by providing a clear product development and delivery plan.

Product Market Fit: Making Your Products Stand Out in a Crowded Market

Delve into the concept of product-market fit, explore its significance, and equip yourself with practical insights to achieve it effectively.

Consumer Behavior in Online Shopping: A Comprehensive Guide

Ever wondered how online shopping behavior can influence successful business decisions? Read on to learn more.

How to Conduct a First Click Test?

Why are users leaving your site so fast? Learn how First Click Testing can help. Discover quick fixes for frustration and boost engagement.

What is Market Intelligence? Methods, Types, and Examples

Read the blog to understand how marketing intelligence helps you understand consumer behavior and market trends to inform strategic decision-making.

What is a Longitudinal Study? Definition, Types, and Examples

Is your long-term research strategy unclear? Learn how longitudinal studies decode complexity. Read on for insights.

What Is the Impact of Customer Churn on Your Business?

Understanding and reducing customer churn is the key to building a healthy business that keeps customers satisfied. Here's all you need to know about it.

The Ultimate Design Thinking Guide

Discover the power of design thinking in UX design for your business. Learn the process and key principles in our comprehensive guide.

100+ Yes Or No Survey Questions Examples

Yes or no survey questions simplify responses, aiding efficiency, clarity, standardization, quantifiability, and binary decision-making. Read some examples!

What is Customer Segmentation? The ULTIMATE Guide

Explore how customer segmentation targets diverse consumer groups by tailoring products, marketing, and experiences to their preferred needs.

Crafting User-Centric Websites Through Responsive Web Design

Find yourself reaching for your phone instead of a laptop for regular web browsing? Read on to find out what that means & how you can leverage it for business.

How Does Product Placement Work? Examples and Benefits

Read the blog to understand how product placement helps advertisers seek subtle and integrated ways to promote their products within entertainment content.

The Importance of Reputation Management, and How it Can Make or Break Your Brand

A good reputation management strategy is crucial for any brand that wants to keep its customers loyal. Here's how brands can focus on it.

A Comprehensive Guide to Human-Centered Design

Are you putting the human element at the center of your design process? Read this blog to understand why brands must do so.

How to Leverage Customer Insights to Grow Your Business

Genuine insights are becoming increasingly difficult to collect. Read on to understand the challenges and what the future holds for customer insights.

The Complete Guide to Behavioral Segmentation

Struggling to reach your target audience effectively? Discover how behavioral segmentation can transform your marketing approach. Read more in our blog!

Creating a Unique Brand Identity: How to Make Your Brand Stand Out

Creating a great brand identity goes beyond creating a memorable logo - it's all about creating a consistent and unique brand experience for your cosnumers. Here's everything you need to know about building one.

Understanding the Product Life Cycle: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the product life cycle, or the stages a product goes through from its launch to its sunset can help you understand how to market it at every stage to create the most optimal marketing strategies.

Empathy vs. Sympathy in UX Research

Are you conducting UX research and seeking guidance on conducting user interviews with empathy or sympathy? Keep reading to discover the best approach.

What is Exploratory Research, and How To Conduct It?

Read this blog to understand how exploratory research can help you uncover new insights, patterns, and hypotheses in a subject area.

First Impressions & Why They Matter in User Research

Ever wonder if first impressions matter in user research? The answer might surprise you. Read on to learn more!

Cluster Sampling: Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand how cluster sampling tackles the challenge of efficiently collecting data from large, spread-out populations.

Top Six Market Research Trends

Curious about where market research is headed? Read on to learn about the changes surrounding this field in 2024 and beyond.

Lyssna Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best lyssna alternative to usability testing, to create a solution for all your user research needs.

What is Feedback Loop? Definition, Importance, Types, and Best Practices

Struggling to connect with your customers? Read the blog to learn how feedback loops can solve your problem!

UI vs. UX Design: What’s The Difference?

Learn how UI solves the problem of creating an intuitive and visually appealing interface and how UX addresses broader issues related to user satisfaction and overall experience with the product or service.

The Impact of Conversion Rate Optimization on Your Business

Understanding conversion rate optimization can help you boost your online business. Read more to learn all about it.

Insurance Questionnaire: Tips, Questions and Significance

Leverage this pre-built customizable questionnaire template for insurance to get deep insights from your audience.

UX Research Plan Template

Read on to understand why you need a UX Research Plan and how you can use a fully customizable template to get deep insights from your users!

Brand Experience: What it Means & Why It Matters

Have you ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Validity in Research: Definitions, Types, Significance, and Its Relationship with Reliability

Is validity ensured in your research process? Read more to explore the importance and types of validity in research.

The Role of UI Designers in Creating Delightful User Interfaces

UI designers help to create aesthetic and functional experiences for users. Here's all you need to know about them.

Top Usability Testing Tools to Try

Using usability testing tools can help you understand user preferences and behaviors and ultimately, build a better digital product. Here are the top tools you should be aware of.

Understanding User Experience in Travel Market Research

Ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Top 10 Customer Feedback Tools You’d Want to Try

Explore the top 10 customer feedback tools for analyzing feedback, empowering businesses to enhance customer experience.

10 Best UX Communities on LinkedIn & Slack for Networking & Collaboration

Discover the significance of online communities in UX, the benefits of joining communities on LinkedIn and Slack, and insights into UX career advancement.

The Role of Customer Experience Manager in Consumer Research

This blog explores the role of Customer Experience Managers, their skills, their comparison with CRMs, their key metrics, and why they should use a consumer research platform.

Product Review Template

Learn how to conduct a product review and get insights with this template on the Qatalyst platform.

What Is the Role of a Product Designer in UX?

Product designers help to create user-centric digital experiences that cater to users' needs and preferences. Here's what you need to know about them.

Top 10 Customer Journey Mapping Tools For Market Research in 2024

Explore the top 10 tools in 2024 to understand customer journeys while conducting market research.

Generative AI and its Use in Consumer Research

Ever wondered how Generative AI fits in within the research space? Read on to find its potential in the consumer research industry.

All You Need to Know About Interval Data: Examples, Variables, & Analysis

Understand how interval data provides precise numerical measurements, enabling quantitative analysis and statistical comparison in research.

How to Use Narrative Analysis in Research

Find the advantages of using narrative analysis and how this method can help you enrich your research insights.

A Guide to Asking the Right Focus Group Questions

Moderated discussions with multiple participants to gather diverse opinions on a topic.

Maximize Your Research Potential

Experience why teams worldwide trust our Consumer & User Research solutions.

Book a Demo

- Solutions Industry Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Member Experience Technology Use case AskWhy Communities Audience InsightsHub InstantAnswers Digsite LivePolls Journey Mapping GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys Research Edition

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Webinars Help center

Mobile Research

Mobile research is a rapidly growing discipline of researchers who focus primarily on mobile-based research studies..

Join over 10 million users

Content Index

- What is Mobile Research?

Applications of Mobile Research

Factors affecting mobile research.

- Advantages of Mobile Research

Mobile Research Survey Tool

Watch the 1-minute tour

Most of the 2000s were spent on static devices like desktops. The world has transformed since then and so has the use of digital platforms and these days every person is online “on the go”. Almost 95% of the US citizens own a mobile phone and 90% of them have mobile internet access. Moreover, smartphone usage has doubled in the past 3 years with October 2016 marking the first time in history when mobile access through smartphones surpassed desktops.

With the rapid growth of mobile internet access, there is an unprecedented opportunity to tap into this newly assembled base of users to conducted focused and more precise mobile research.

So, what is mobile research?

Mobile research is a rapidly growing discipline of researchers who focus primarily on mobile-based research studies to tap into the flexibility, customizability, accuracy, and localization to get faster and more precise insights.

It’s easy, convenient and straightforward to capture data from anywhere and anytime as it uses the benefits of “mobile” technology to conduct effective “research”.

This research type can be used in three major ways:

- Recruiting a panel that will take a survey using their mobile platforms.

- Appoint interviewers to collect responses using tablets or smartphones.

- Collect data without internet (Offline mobile surveys).

In the first method, you can arrange a panel that would respond to your surveys and give you precise insights. As a panel consists of selected, filtered and handpicked individuals who already qualify for the research, asking them questions and getting insights is not just more easier but far more accurate and detailed.

The second method is applied on site for B2B or B2C purposes where you appoint interviewers or in most cases employees, to collect data on mobile devices. This method is very effective during concerts or live events where face to face data collection is possible for understanding user experience and making improvements.

Another way of conducting this research is by collecting data from locations where internet isn’t available. In such cases, the data collected offline will get automatically synced once internet becomes accessible.

In mobile research, all respondents take part from a mobile device. This presents researchers with both - opportunities and some restrictions. In such a situation, it is important to keep in mind these factors that affect the mobile research process:

Scrolling can get on people’s nerves. Respondents do not mind switching pages to answers ‘n’ number of questions but they do mind long scrolling surveys. This may impact the number of people completing the survey and can be quite a decisive factor for mobile research. If your survey has too many questions, you should increase the number of pages rather than increasing the length of a single page that would increase the scrolling time.

This can also be done by evaluating the questions that you intend to add in this research survey. Removing all the redundant questions will not only shorten the surveys but will also increase the effectiveness of the survey as a shorter survey will be easy and less time consuming to fill out.

For any kind of survey, question types are important and when it comes to mobile surveys, this can be all the more important. Create questions that the respondents can easily reply to from their mobile devices. Multiple choice questions are one of the most popularly used questions for a mobile-friendly survey. You may also want to avoid using open ended or descriptive questions because of the limitations that come with the size of the mobile screen. Instead of asking longer questions, you can also split the question into various multiple choice questions which will get you better results.

Apart from the question types in general, you may want to take care of the answer options too. Offering positive options first and then the negative options will affect the kind of answers you get. For mobile devices, horizontal scrolling should be strictly restricted as it can get very laborious for respondents to do that.

Loading time of videos and images are different for laptops and for mobile devices. Most mobile devices are operated using the data from phone networks and not ethernet or wi-fi. Due to this, it takes more time for the videos to load on phone than it would take on a laptop.

Decide on the minimum number of videos that you would like to use on mobile devices that may not impact the number of people taking the mobile research survey.

A few other factors that affect mobile research-

- Create mobile compatible logos.

- Mobile-friendly fonts and texts.

- Option for full screen coverage that will eliminate interruptions from other applications.

Advantages of Mobile Research:

As everyone is on mobile devices these days, gauging attention of the respondents via mobile research is prompter than the other means. Due to the various modes like surveys or mobile applications or GPS, getting in touch with your respondents becomes a very easy job. If the survey has direct, relevant questions, survey makers can get faster and more accurate answers via these research surveys.

In case a survey requires the respondents to fill in specific details, uploading images or recording voice notes or collecting information in a diary format is easier using mobile surveys. This is the main reason why these surveys are more adaptable than the traditional ones.

Quicker survey completion time, higher rate in collecting data, tracking of the respondent’s geo location etc. are other reasons that mobile research surveys are better.

These research surveys can be made interactive by asking the respondents to submit videos or images.

All QuestionPro mobile research survey tools offer 100% mobile compatible surveys. All the surveys created using our online platform are by default mobile compatible with no display restrictions regarding of the type of questions (standard or advanced).

QuestionPro also offers an offline mobile application to conduct these surveys in locations where internet connection isn’t available. Incase the responses are collected offline, they can be conveniently synced when network is accessible again. Due to this integral feature, you can get in touch with respondents that you usually wouldn’t be able to with the other survey tools in the market.

Along with these offerings, QuestionPro also provides 250+ mobile friendly survey templates.

- Sample questions

- Sample reports

- Survey logic

- Integrations

- Professional services

- Survey Software

- Customer Experience

- Communities

- Polls Explore the QuestionPro Poll Software - The World's leading Online Poll Maker & Creator. Create online polls, distribute them using email and multiple other options and start analyzing poll results.

- Research Edition

- InsightsHub

- Survey Templates

- Case Studies

- AI in Market Research

- Quiz Templates

- Qualtrics Alternative Explore the list of features that QuestionPro has compared to Qualtrics and learn how you can get more, for less.

- SurveyMonkey Alternative

- VisionCritical Alternative

- Medallia Alternative

- Likert Scale Complete Likert Scale Questions, Examples and Surveys for 5, 7 and 9 point scales. Learn everything about Likert Scale with corresponding example for each question and survey demonstrations.

- Conjoint Analysis

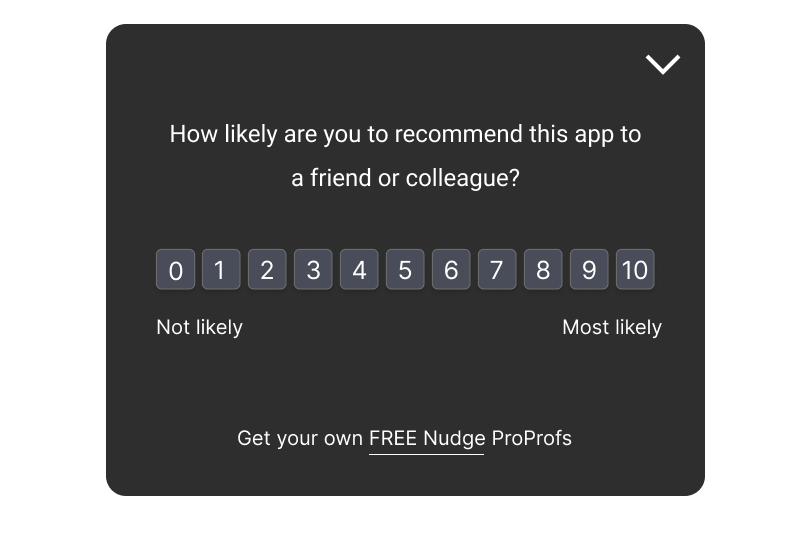

- Net Promoter Score (NPS) Learn everything about Net Promoter Score (NPS) and the Net Promoter Question. Get a clear view on the universal Net Promoter Score Formula, how to undertake Net Promoter Score Calculation followed by a simple Net Promoter Score Example.

- Offline Surveys

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Survey Software Employee survey software & tool to create, send and analyze employee surveys. Get real-time analysis for employee satisfaction, engagement, work culture and map your employee experience from onboarding to exit!

- Market Research Survey Software Real-time, automated and advanced market research survey software & tool to create surveys, collect data and analyze results for actionable market insights.

- GDPR & EU Compliance

- Employee Experience

- Customer Journey

- Executive Team

- In the news

- Testimonials

- Advisory Board

QuestionPro in your language

- Encuestas Online

- Pesquisa Online

- Umfrage Software

- برامج للمسح

Awards & certificates

The experience journal.

Find innovative ideas about Experience Management from the experts

- © 2021 QuestionPro Survey Software | +1 (800) 531 0228

- Privacy Statement

- Terms of Use

- Cookie Settings

- About About dataSpring Get to know your Asian panel insights provider. Meet the Team We aspire to be visionary, passionate, and relentless drivers of dataSpring values. Careers See our current openings and let’s build great things together! Visit Us Check out our offices in key cities across Asia.

- Products dataSpring Panels Asian Sample We’re ready to serve your research needs with our expansive coverage in Asia. Panel Sources Our secure data comes from proprietary panels, API integration, and third-party partners. Panel Quality Our industry-leading Quality Check System ensures data validity and valuable insights. Operations Enjoy convenient 24/7 support from our highly-capable Springers who speak your language. Get Our Panel Book Solutions Products Complete your requirements with our reliable platforms. Services We provided solutions for every stage of your projects. Mobile Platform Draw in-the-moment insights from Asian mobile consumers with our all-in-one platform. Check our mobile capabilities

- Resources Get started Understanding Online Research Panels Mobile Research Essentials Downloadable Media Newsletter Press Releases Resources Blogs Read more on topics about online research solutions to get you started. Eye On Asia Check out the latest trends in Asia and learn valuable local insights. dS Insights Relevant and beneficial market research content, updated regularly. Eye On Asia Podcast Listen to the latest market research news and trends in Asia in dataSpring's monthly podcast. リソース ブログ マーケティングリサーチやアジア諸国の情報について Eye On Asia アジアの最新トレンドをチェックして、現地の貴重な情報を知ることができます。 最新のインサイト情報 アジア地域のパネルについては、毎月実施される自主調査より詳しい情報をご確認いただけます。 Eye On Asia Podcast Eye On Asia Podcastにて、最新のアジアのマーケティングリサーチに関するニュースやトレンドを聞くことができます。

- Ask dataSpring

- About dataSpring

- Meet the Team

- Asian Sample

- Panel Sources

- Panel Quality

- Mobile Platform

- Understanding Online Research Panels

- Mobile Research Essentials

- Eye On Asia

- dS Insights

- Eye On Asia Podcast

- Downloadable Media

- Press Releases

- オンラインパネルについて

- モバイルリサーチの必要性について

- Ask dataSpring Contact Us

Relevant and beneficial market research content, updated regularly.

[Infographic] Pros and Cons of Mobile Research

![example of mobile research [Infographic] Pros and Cons of Mobile Research](https://www.d8aspring.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Blog/20180302-%5BInfographic%5D-Pros-and-Cons-of-Mobile-Research-Photo-1.jpg?width=680&name=20180302-%5BInfographic%5D-Pros-and-Cons-of-Mobile-Research-Photo-1.jpg)

Mobile phone adoption, especially smartphones, can help researchers and consultants expand and enrich their studies by capturing data at decisive moments in the decision-making process.

While not fully adopted by the industry, there is growing use of the platform: the latest Greenbook Research Industry Trends Report (GRIT) reveals 52% of companies are conducting mobile first surveys, 46% are delving in mobile qualitative, and 36% are utilizing mobile in ethnographic studies.

But it is important to do more than simply adapt online surveys to the mobile screen and call it a day. It is vital to weigh the pros and cons of mobile research to ensure the method fits the objectives of the study.

Pros and Cons of Mobile Research

![example of mobile research [Infographic] Pros and Cons of Mobile Research](https://www.d8aspring.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Blog/20180302-%5BInfographic%5D-Pros-and-Cons-of-Mobile-Research-Photo-2.jpg?width=680&name=20180302-%5BInfographic%5D-Pros-and-Cons-of-Mobile-Research-Photo-2.jpg)

1. Target Reach

Mobile is often the best and most efficient way to reach audiences who are primarily on their smartphone (millennials, business and professional people). The same is true in global studies where a large portion of the population's only internet access is through a mobile device.

2. Sample Authentication

The built-in GPS allows a measure of quality control by allowing the sample supplier to determine if the respondent is an actual person and not a bot. Further, if the study involves a travel task, such as shopping at a specific store or auto dealership, the data can verify that the respondent did indeed make the visit.

3. Real-time Input

As noted above, the GPS capabilities of mobile devices allow sample suppliers with mobile panels to engage respondents 'in-the-moment'. This immediacy is crucial when trying to understand a consumer's thought process during the shopping and buying experience. Technologies like geo-fencing allow the supplier to intercept respondents when visiting certain venues or stores.

4. Respondent Experience

Because of the limitations of the mobile survey platform (see Cons, below), most mobile surveys are short and succinct, making participation more enjoyable for the respondent. This higher level of engagement by respondents leads to more considered response and higher data quality.

5. Richer Data

The addition of passive data can add depth to the survey by understanding the activities respondents perform on their smartphone, along with their location information. Of course, these need to be done with the respondent's consent . In addition to passive data, the attachment of photos, voice notes, and videos can help go 'beyond the numbers' and provide texture, context, and nuance to the data.

1. Survey Length Limitations

Mobile's 'in-the-moment' advantage is also a disadvantage in that respondents use of their mobile phone tends to be quick and on-the-go. Long mobile surveys are at risk of distraction from other apps, text messages, and outside influences. This may result in higher incomplete rates which can drive up the cost and lower data quality.

2. Complexity Issues

The mobile phone questionnaire experience is much different from that of online or offline methods. The small screen display does not lend itself to long attribute batteries or lengthy pull-down lists. Using question designs that require the user to scroll excessively or pinch and zoom may compromise data quality because the respondent may not take the time to see all the response options. Save complexity for online surveys.

3. Image Video Restrictions

While many use their smartphone extensively for image and video viewing, including media in a survey for evaluation (e.g., product or ad concepts, package designs, etc.) is not recommended. Because the viewing experience can vary greatly from device to device, it is impossible to know if the media is being evaluated on a fair and equal basis, potentially skewing results significantly.

4. Gen Pop Reach

While we think of mobile and smartphones as fairly ubiquitous, some sample audiences may be less inclined to participate due to data use or comfort with the technology. Mobile only audiences tend to skew younger and/or more affluent, so make sure your method approach matches your sample needs.

5. Device Considerations

Mobile survey apps need to be configured to work on a wide range of operating systems to avoid a skewed sample. While iPhones and Androids dominate the smartphone market, 'mobile' may include tablets and other devices that have different operating systems (Amazon Fire, Windows 10).

Mobile research should be thought of as another viable method in the researcher's toolbox and not a universal approach for all situations. Conducting research outside the home or office is a huge opportunity for the industry to bring new insight and perspective to all kinds of consumer experiences and behaviors. But because mobile can provide such easy access to personal data, it is essential to respect the privacy of the respondent and obtain explicit consent for data retrieval (see ESOMAR's Mobile Research Guidelines ).

Due to advances in mobile device technology and widespread adaption of mobile phones for online access, especially in Asia , mobile research has become a powerful tool for market researchers to harness. If you want to know more about mobile research, how to enhance your methodology toolbox, and Asia mobile panels, check out our Mobile Research Essentials page .

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

Advances in mobile technology make it imperative for researchers and consultants to consider privacy in mobile research studies.

Questionnaire design in mobile devices is one of the essential elements in constructing a successful mobile market research study. Just as online surveys changed questionnaire design from telephone da...

Contact us anytime 24/7! One of our Springers will be in touch with you within 24-48 hours to follow up on your request.

- Tokyo +81 3-5294-5970

- Shanghai +86 21-5238-7703

- Seoul +82 2-778-6051

- Manila +63 2-8899-3862

- Singapore +65 9001-1137

- Los Angeles +1 718-404-9260

- London +44 7724-025-169

© 2024 dataSpring Inc. Know today, Power tomorrow INTAGE GROUP

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Mobile phone data: a survey of techniques, features, and applications.

1. Introduction

2. survey methodology.

- IC1: A study has to be in a journal or proceedings

- IC2: Studies are peer-reviewed articles

- IC3: A study must be written in the English language

- IC4: A study must be published from 2013 to 2021

- EC1: Articles that are not written in English

- EC2: A study that is not published between 2013 and 2021

3. Mobile Phone Data Types

4. human mobility patterns, 4.1. urban environment, 4.2. classification of urban land use, 4.3. urban crime research, 4.4. public health, 4.5. transportation research, 5. human communication behaviors, 5.1. the construction of social networks, 5.2. network metrics, 6. discussion, 6.1. public datasets in mobile phone data, 6.2. distribution of mobile phone data applications, 6.3. methods, 6.4. managerial implications, 7. research opportunities, 8. privacy concerns and ethical implications, 9. conclusions and limitations, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest, abbreviations.

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CDRs | Call detail records |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SNA | Social network analysis |

| LSOAs | Lower super output areas |

| SVM | Support vector machines |

| RF | Random forest |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| FCM | Fuzzy c-means |

| GCN | Graph convolutional network |

| GMM | Gaussian mixture model |

| DBSCAN | Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise |

| GBDT | Gradient boosting decision tree |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron |

| DT | Decision trees |

| BP | Backward propagation |

| HC | Hierarchical clustering |

| LR | Logistic regression |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SDAE | Stacked denoising autoencoder |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| SVM-Linear | SVM with linear kernel |

| SVM-RBF | SVM with radial basis function kernel |

| CART | Classification and regression tree (CART) |

| Bagged CART | Bagging classification and regression trees |

| FRNN | Fuzzy-rough nearest neighbors |

| FKNN | Fuzzy k-nearest neighbor |

| REDCAP | Regionalization with dynamically constrained agglomerative Clustering and partitioning |

| SLPA | Speaker–listener label propagation algorithm |

| SMS | Short message service |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| PAM | Partitioning around medoids |

- Blondel, V.D.; Decuyper, A.; Krings, G. A survey of results on mobile phone datasets analysis. EPJ data science 2015 , 4 , 10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ghahramani, M.; Zhou, M.; Wang, G. Urban sensing based on mobile phone data: Approaches, applications, and challenges. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2020 , 7 , 627–637. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Taha, K.; Yoo, D. SIIMCO: A forensic investigation tool for identifying the influential members of a criminal organization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Secur. 2015 , 11 , 811–822. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hassan, S.U.; Shabbir, M.; Iqbal, S.; Said, A.; Kamiran, F.; Nawaz, R.; Saif, U. Leveraging deep learning and SNA approaches for smart city policing in the developing world. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019 , 56 , 102045. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Griffiths, G.; Johnson, S.D.; Chetty, K. UK-based terrorists’ antecedent behavior: A spatial and temporal analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2017 , 86 , 274–282. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eagle, N.; Pentland, A.; Lazer, D. Inferring friendship network structure by using mobile phone data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009 , 106 , 15274–15278. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Deville, P.; Linard, C.; Martin, S.; Gilbert, M.; Stevens, F.R.; Gaughan, A.E.; Blondel, V.D.; Tatem, A.J. Dynamic population mapping using mobile phone data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014 , 111 , 15888–15893. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Pei, T.; Sobolevsky, S.; Ratti, C.; Shaw, S.L.; Li, T.; Zhou, C. A new insight into land use classification based on aggregated mobile phone data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2014 , 28 , 1988–2007. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Mao, H.; Ahn, Y.Y.; Bhaduri, B.; Thakur, G. Improving land use inference by factorizing mobile phone call activity matrix. J. Land Use Sci. 2017 , 12 , 138–153. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Frias–Martinez, V.; Soto, V.; Sánchez, A.; Frias–Martinez, E. 2014. Consensus clustering for urban land use analysis using cell phone network data. Int. J. Ad Hoc Ubiquitous Comput. 2014 , 17 , 39–58. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jia, Y.; Ge, Y.; Ling, F.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Urban land use mapping by combining remote sensing imagery and mobile phone positioning data. Remote Sens. 2018 , 10 , 446. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Yuan, G.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Lai, J.; Li, T.; Liu, Z. Recognition of functional areas based on call detail records and point of interest data. J. Adv. Transp. 2020 , 2020 , 8956910. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mao, H.; Thakur, G.; Bhaduri, B. Exploiting mobile phone data for multi-category land use classification in Africa. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGSPATIAL Workshop on Smart Cities and Urban Analytics, Burlingame, CA, USA, 31 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lenormand, M.; Picornell, M.; Cantú-Ros, O.G.; Louail, T.; Herranz, R.; Barthelemy, M.; Frías-Martínez, E.; San Miguel, M.; Ramasco, J.J. Comparing and modelling land use organization in cities. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015 , 2 , 150449. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Ríos, S.A.; Muñoz, R. Land Use detection with cell phone data using topic models: Case Santiago, Chile. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017 , 61 , 39–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Järv, O.; Tenkanen, H.; Toivonen, T. Enhancing spatial accuracy of mobile phone data using multi-temporal dasymetric interpolation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017 , 31 , 1630–1651. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, T.; Du, Y.; Pei, T.; Yi, J.; Peng, H. 2018. Mapping hourly dynamics of urban population using trajectories reconstructed from mobile phone records. Trans. GIS 2018 , 22 , 494–513. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Calabrese, F.; Ferrari, L.; Blondel, V.D. Urban sensing using mobile phone network data: A survey of research. Acm Comput. Surv. Csur 2014 , 47 , 1–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bachir, D.; Khodabandelou, G.; Gauthier, V.; El Yacoubi, M.; Puchinger, J. Inferring dynamic origin-destination flows by transport mode using mobile phone data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019 , 101 , 254–275. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Rietveld, P.; Koomen, E.; Tranos, E. Evaluating the impact of land-use density and mix on spatiotemporal urban activity patterns: An exploratory study using mobile phone data. Environ. Plan. A 2014 , 46 , 2769–2785. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dong, Y.; Pinelli, F.; Gkoufas, Y.; Nabi, Z.; Calabrese, F.; Chawla, N.V. Inferring unusual crowd events from mobile phone call detail records. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Porto, Portugal, 7–11 September 2015; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2015; pp. 474–492. [ Google Scholar ]

- Furno, A.; El Faouzi, N.E.; Fiore, M.; Stanica, R. Fusing GPS probe and mobile phone data for enhanced land-use detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 5th IEEE International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems (MT-ITS), Naples, Italy, 26–28 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 693–698. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zinman, O.; Lerner, B. Utilizing digital traces of mobile phones for understanding social dynamics in urban areas. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020 , 24 , 535–549. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yang, X.; Fang, Z.; Yin, L.; Li, J.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Z. Revealing the relationship of human convergence–divergence patterns and land use: A case study on Shenzhen City, China. Cities 2019 , 95 , 102384. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Jing, Y. How urban land use influences commuting flows in Wuhan, Central China: A mobile phone signaling data perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020 , 53 , 101914. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Novović, O.; Brdar, S.; Mesaroš, M.; Crnojević, V.; Papadopoulos, A.N. Uncovering the relationship between human connectivity dynamics and land use. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020 , 9 , 140. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Long, D.; Liu, L.; Xu, M.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; He, L. Ambient population and surveillance cameras: The guardianship role in street robbers’ crime location choice. Cities 2021 , 115 , 103223. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Malleson, N.; Andresen, M.A. Exploring the impact of ambient population measures on London crime hotspots. J. Crim. Justice 2016 , 46 , 52–63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bogomolov, A.; Lepri, B.; Staiano, J.; Oliver, N.; Pianesi, F.; Pentland, A. Once upon a crime: Towards crime prediction from demographics and mobile data. In Proceedings of the 16th international conference on multimodal interaction, Istanbul, Turkey, 12 November 2014; pp. 427–434. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bogomolov, A.; Lepri, B.; Staiano, J.; Letouzé, E.; Oliver, N.; Pianesi, F.; Pentland, A. Moves on the street: Classifying crime hotspots using aggregated anonymized data on people dynamics. Big Data 2015 , 3 , 148–158. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rummens, A.; Snaphaan, T.; Van de Weghe, N.; Van den Poel, D.; Pauwels, L.J.; Hardyns, W. Do mobile phone data provide a better denominator in crime rates and improve spatiotemporal predictions of crime? ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021 , 10 , 369. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Long, D.; Liao, W. An examination of spatial differences between migrant and native offenders in committing violent crimes in a large Chinese city. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019 , 8 , 119. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- He, L.; Páez, A.; Jiao, J.; An, P.; Lu, C.; Mao, W.; Long, D. Ambient population and larceny-theft: A spatial analysis using mobile phone data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020 , 9 , 342. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ferrara, E.; Meo, D.; Catanese, S.; Fiumara, G. Detecting criminal organizations in mobile phone networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014 , 41 , 5733–5750. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]