The SAFe® Epic – an example

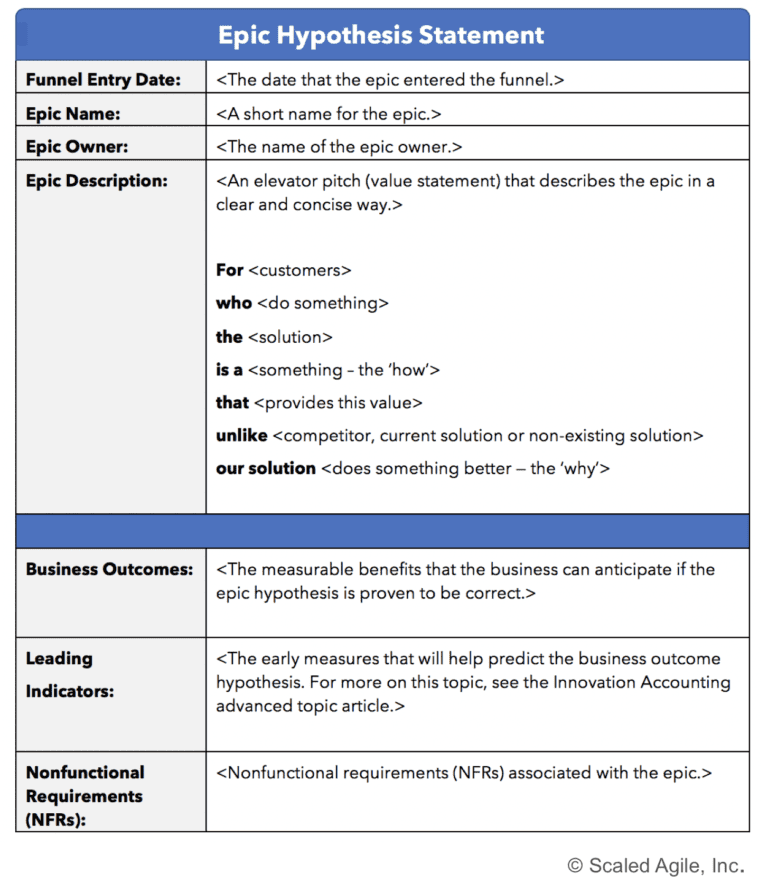

We often have questions about what a “good” sufficiently developed SAFe Epic looks like. In this example we use with clients during the Lean Portfolio Management learning journey, we dive into an example of real-world details behind an epic hypothesis statement.

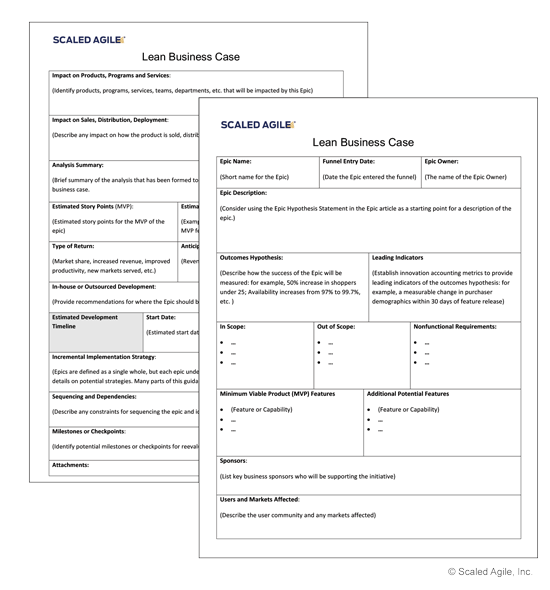

For now, we have not provided a fully developed SAFe Lean Business Case as an example because business cases are typically highly contextual to the business or mission. That being said please remember that the core of the business case is established and driven from the Epic Hypothesis Statement and carried over into the documented business case.

Agile Lifecycle Management Solution Enabler Epic

Epic Owner: John Q. Smith

Epic Description

The big awesome product company requires a common platform for collaboration on work of all types across the portfolio for all teams, managers, architects, directors, and executives including customer collaboration and feedback loops. This solution will solve the problems in our system where we have poor quality or non-existent measurement and multiple disparate systems to manage and report on work.

For the Portfolio Teams

Who needs to manage their work, flow, and feedback

The single-source system of record for all work

IS A web-based software tool suite that provides customizable workflows that support the enterprise strategic themes related to creating better business and IT outcomes using guidance from the Scaled Agile Framework for Lean Enterprises (SAFe), Technology Business Management (TBM), and Value Stream Management (VSM) via the Flow Framework

THAT will provide a common place for all customers and portfolio stakeholders to have a transparent vision into all of the work occurring in the system/portfolio, provide a mechanism to manage capacity at scale, and enable easier concurrent road mapping

UNLIKE the current array of disparate, ad hoc tools and platforms

OUR SOLUTION will organize all work in a holistic, transparent, visible manner using a common enterprise backlog model combined with an additive enterprise agile scaling framework as guidance including DevOps, Lean+Systems Thinking, and Agile

Business Outcomes:

- Validate that the solution provides easy access to data and/or analytics, and charts for the six flow metrics: distribution, time, velocity, load, efficiency, and predictability for product/solution features (our work). (binary)

- The solution also provides flow metrics for Lean-Agile Teams stories and backlog items. (binary)

- 90% of teams are using the solution to manage 100% of their work and effort within the first year post implementation

- All features and their lead, cycle, and process times (for the continuous delivery pipeline) are transparent. Feature lead and cycle times for all value streams using the system are visible. (binary)

- Lean flow measurements — Lead and cycle times, six SAFe flow metrics, and DevOps metrics enabled in the continuous delivery pipeline integrated across the entire solution platform (binary)

- Activity ratios for workflow, processes, and steps are automatically calculated (binary)

- Percent complete and accurate (%C&A) measures for value streams automatically calculated or easily accessible data (binary)

- Number of documented improvements implemented in the system by teams using data/information sourced from the ALM solution > 25 in the first six months post implementation

- Number of documented improvements implemented in the system by teams using data/information sourced from the ALM solution > 100 in the first year post implementation

- Flow time metrics improve from baseline by 10% in the first year post implementation (lead time for features)

- Portfolio, Solution/Capability, and Program Roadmaps can be generated by Lean Portfolio Management (LPM), Solution Management, and Product Management at will from real-time data in the ALM (binary)

- Roadmaps will be available online for general stakeholder consumption (transparency)

- Increase customer NPS for forecasting and communication of solution progress and transparency of execution by 20% in the first year post implementation (survey + baseline)

- Build a taxonomy for all work including a service catalog (binary)

- Run the system and the system produces the data to produce the capacity metrics for all value streams to enable the LPM guardrail (binary)

- Stops obfuscation of work hidden in the noise of the one sized fits all backlog model (everything is a CRQ/Ticket) and allows for more accurate and representative prioritization including the application of an economic decision-making framework using a taxonomy for work (binary)

- Enables full truth in reporting and transparency of actual flow to everyone, real-time – including customers (100% of work is recorded in the system of record)

- Enables live telemetry of progress towards objectives sourced through all backlogs, roadmaps, and flow data and information (dependent)

- 90% of teams are using the solution to manage 100% of their capacity within the first year post implementation

Leading Indicators:

- Total value stream team member utilization > 95% daily vs. weekly vs. per PI

- Low daily utilization < 75% indicates there is a problem with the solution, training, or something else to explore

- % of teams using the ALM solution to manage 100% of their work and effort

- Number of changes in the [old solutions] data from the implementation start date

- Usage metrics for the [old solutions]

- We can see kanban systems and working agreements for workflow state entry and exit criteria in use in the system records

- Teams have a velocity metric that they use solely for the use of planning an iterations available capacity and not for measuring team performance (only useful for planning efficiency performance)

- Teams use velocity and flow metrics to make improvements to their system and flow (# of improvements acted from solution usage)

- Teams are able to measure the flow of items per cycle (sprint/iteration) and per effort/value (story points; additive)

- Program(s)[ARTs] are able to measure the flow of features per cycle (PI) and per effort/value (story points; additive from child elements)

- Portfolio(s) are able to measure the flow of epics per cycle (PI) and per effort/value (story points; additive from child elements)

- % of total work activity and effort in the portfolio visible in the solution

- Show the six flow metrics

- Features (Program) – current PI and two PI’s into the future

- Epics and Capabilities – current PI up to two+ years into the future

- are the things we said we were going to work on and what we actually worked on in relation to objectives and priorities (not just raw outputs of flow) the same?

- The portfolio has a reasonable and rationalized, quality understanding of how much capacity exists across current and future cycles (PI) in alignment with the roadmap

- Identification and reporting of capacity across Portfolio is accurate and predictable;

- Identification of Operational/Maintenance-to-Enhancement work ratio and work activity ratios and % complete and accurate (%C&A) data readily available in the system

- including operations and maintenance (O&M) work and enhancements,

- highlighting categories/types of work

- Work activity ratios are in alignment with process strategy and forecasts, process intent, and incentivizing business outcomes;

- allows leadership to address systemic issues;

- data is not just reported, but means something and is acted upon through decision-making and/or improvements

- # of epics created over time

- # of epics accepted over time

- # of MVP’s tested and successful

- Parameters configured in the tool to highlight and constrain anti-patterns

- Stimulates feedback loop to assist in making decisions on whether to refine/improve/refactor and in that case, what to refine/improve/refactor

- Strategic themes, objectives, key results, and the work in the portfolio – Epics, Capabilities, Features, Stories traceability conveyed from Enterprise to ART/Team level

Non-Functional Requirements

- On-Premise components of the ALM solution shall support 2-Factor Authentication

- SaaS components of the ALM solution shall support 2-Factor Authentication and SAML 2.0

- The system must be 508 compliant

- The system must be scalable to support up to 2000 users simultaneously with no performance degradation or reliability issues

- Must be the single-source system for all work performed in the portfolio and value streams.

- ALM is the single-source system of record for viewing and reporting roadmap status/progress toward objectives

Building your Experiment – The Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

Once you have constructed a quality hypothesis statement the product management team should begin work on building the lean business case and MVP concept. How are you going to test the hypothesis? How can we test the hypothesis adequately while also economically wrt to time, cost, and quality? What are the key features that will demonstrably support the hypothesis?

- Name First Last

Epical epic. Agile epic examples

What is an agile epic, what to use it for, and foremost how?

Requirements. Small, large, technical, business, operational, and researchable. And above all, plenty of them. During four years of ScrumDesk development, we have more than 800 requirements in our backlog. And these are the only requirements that we have decided to implement without any further ideas that would be nice to have. It is, of course, difficult to navigate such a long list without any additional organization of the backlog structure. And this is where Epic comes to help.

Every Scrum or Agile training introduces the term Epic. In training sessions, epics are presented by only using one image, and essentially, they are not even explained assuming their simplicity. It is not rocket science. However, the question emerges as soon as a product owner starts preparing a backlog of the product. How to organize epics? What are they supposed to describe? How to organize them?

Epic is a set of requirements that together deliver greater business value and touch the same portion of the product, either functional or logical.

Agile Epic, similar to the requirement itself (often User story), is supposed to deal with a problem of single or multiple users and at the same time should be usable and valuable.

How to identify epic?

It is no science at all. Start with thinking about a product from a large perspective. Agile epic is a large high-level functionality. Their size is large, usually in hundreds of story points. However, all these chunks of functionalities must be usable end to end. In practice, we have encountered multiple approaches to epic design. Let’s try to see which one is the best for you.

Epics are managed by product management or other strategic roles. For smaller products, Product Owners identify them. Agile epics help structure your work into valuable parts that can be developed faster while delivering value to users.

I. Epic as a part of the product

Epic can represent a large, high-level yet functional unit of the product. For example, in ScrumDesk we have epics BACKLOG, PLAN, WORK, REPORTS. In the app, you can find parts, and modules, which are called the same way as a given epic.

Top epics of the ScrumDesk product

This backlog organization is appropriate when you are creating a product that you are going to be developing in the long run.

Why use this method of epic organization?

- As a product owner, you simply have to be able to orientate yourself in parts of the product and know what you have or have not finished yet.

- At the same time, it is easy to measure progress by parts of the product.

- The Product Owner is naturally urged to change the order of features in the epic , which leads to the creation of rapid delivery of a minimum of viable product increments .

The disadvantage of this method is the lacking view of the user journey It is not visible which parts of the backlog cover what parts of the user value flow. E.g. process from registration, and basket to payment. Each part of the process can belong to a different epic.

Epics, in this case, do not end here, they are not concluded because the functional unit is delivered in the long term. In years. In the roadmap, the implementation of level features of individual epics is planned.

II. Epic as a part of the business flow

This approach is based on the fact, that we know the flow of values, meaning a business process that we can divide into individual parts and then make it more detailed and deliver iteratively. High-level functionalities follow the business workflows.

Epics by the business workflow

For example, an e-shop. Agile epics candidates would be:

- Product catalog viewing – for portraying categories of goods and a list of goods in each category, filtering and searching for goods.

- Product selection – a selection of interesting products such as favorites, comparing, pricing, or adding to a cart.

- The Cart of the products – browsing the content of a basket, comparing, and counting the total price.

- Payment – choice of payment options, total order, total price, shipping, the payment itself, and payment confirmation.

- Product delivery – a visual display of the delivery status, email, and SMS notifications.

The product owner is naturally able to focus on the delivery of the whole customer’s experience . The first fully functional version is then created quite quickly and is subsequently improved iteratively. Epic Payment is based on VISA, transfer, and cash. In the first version, only Visa payment will be delivered, transfer and cash in the next one.

The development of epics takes a longer time in this case. It does not usually make sense to close them, as they will be further elaborated in the future by other features. Business easily understands the state of the implemented application (e-shop) which simplifies communication and significantly improves cooperation between IT and business. It is important to use commercial terms rather than technological ones.

III. Project as epic

Do you deliver products to a client in various phases and various projects? In this case, it may be easier to create epics according to projects or the project’s phases.

Epics as project or phase

Such epics are usually considered finished (closed) when the project is delivered. The advantage is obvious. There is an absolutely clear state of implementation of the project. Participants and stakeholders have excellent transparency. At the same time, stakeholders can focus on preparing for the next phase of the project.

On the other hand, it can be quite difficult to keep an overview of the functionalities units of the product itself. The state is more perceived by architects rather than the business itself. In real life, we also came across seeing this way to lead to a change in the company’s focus, or even to the degradation of its vision. A company that once wanted to act as a product and solution maker became a company fully listening to clients. Their products became a ‘toy’ in the hands of clients which led to people leaving teams because they have lost the personal connection with the product. They often lose the power to say NO.

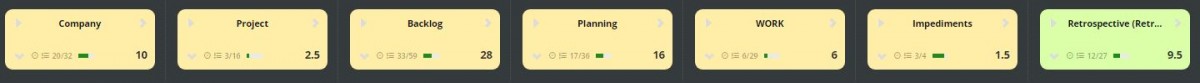

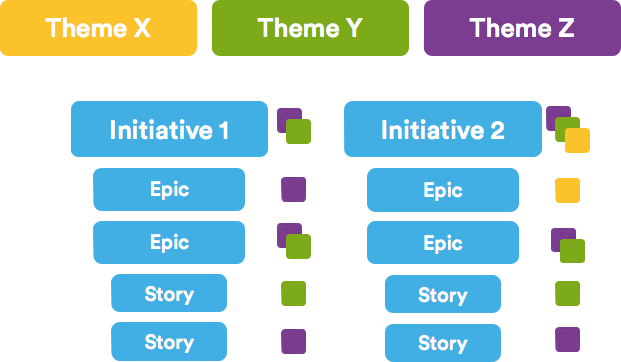

It is also practical to use themes for further categorization of requirements . This creates a virtual matrix, in which each requirement belongs to a certain product set and also might belong to a business theme that is communicated to clients. In ScrumDesk we use, for example, themes for identifying clients who had requested larger sets of features, and we, after all, decided to include them in backlogs. As a product owner, I know how to communicate the status of requirements with a client while still keeping my eyes on the implementation of the product itself.

Epics and Themes

Themes in the product world are often determined by top management at strategic meetings and these topics are subsequently implemented in multiple value streams supported by multiple products. An example of such strategic themes can be 3D Maps, AI (Artificial Intelligence) in risky investments, and traveling without physical gates and cards.

Artificial Epics

In addition to business logic, an application has many parts that create a basic core of a product, but a customer rarely notices them.

First of all, you need to think about and register, for example, the design of architecture, suggestion of UX layout of an app, initial frameworks, and technological preparation. In later phases, the functionalities are still touching the entire product at once. E.g. logging, error handling etc. In ScrumDesk we had an epic called #APPLICATION for such requirements.

When we started four years ago, we decided to keep all bugs in epics titled #TECH. Symbol # indicates artificial epic.

Later we changed this strategy and now we are trying to put every requirement, regardless of its type, under the right epic, as the epic either repairs or expands, improves from the technological point of view.

Epic and business value

In Agile, each requirement should deliver additional business value. However, in the case of more complex applications, it is almost impossible to evaluate the value supplied at such a low level. In this case, it is easier to determine the business value at the level of epic . Epic then can analyze, suggest and prepare ahead of implementation itself beforehand.

It is also possible to create a business case and consequently the business value itself. Such an approach is recommended, for example, Scaled Agile Framework, in which the epic adds value to the selected value stream.

Epics in SAFe

How to prepare epics?

Product Owner prepares epics in advance, prior to planning and implementation.

For good preparation he needs support from multiple people:

- an architect for a rough design of the architecture that is needed to implement the epic,

- stakeholders, for whom the functionality will be delivered, for business value determination and business case,

- UX Designer to work out framework principles of interface design and usability of the epic,

- People from service and support for a good design of epic from the operational perspective,

- And whoever else is needed

PREARE EPICS IN SCRUMDESK FOR FREE

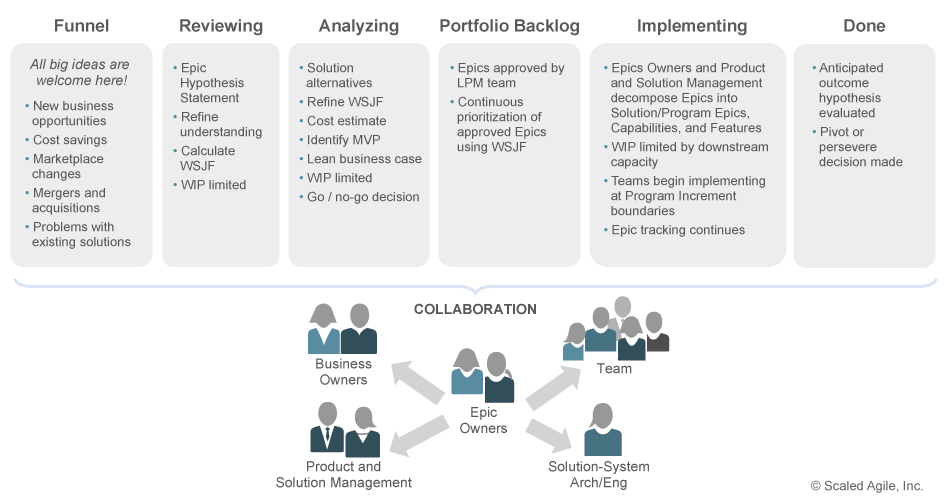

Preparation of an epic can, and often has a different process than the requirements themselves. In SAFe ‘Portfolio Kanban’ is recommended for the preparation of epics. Therefore, a separate Kanban board with multiple statuses exists on which the momentum of the epic realization is transparently displayed. This creates space for regular meetings of a small team preparing requirements ahead and continuous improvement of epic details.

Portfolio Kanban systems for epics management

The Product Owner basically works in two-time spaces. In the first one, he prepares epics for the future, and in the second he contributes to the implementation of already developed epics.

How ScrumDesk helps with epics?

ScrumDesk supports epics from its first version. As we use ScrumDesk for the development of the ScrumDesk, we identified and tried different approaches to backlog organization. In the first version epics were just titles, later we added possibilities to:

- add more details in the description of the epic,

- visualize epics as colored cards in user stories map,

- added an option to track the business value, risk, effort (as an aggregation of child requirements),

- break down epics into features and/or user stories to manage complex backlogs,

- track comments and changes,

- attach files (i.e. business cases),

- possibility to add the timeline for epics and features with the support of agile roadmaps displaying not just plans, but comparing them to reality as well.

Common mistakes

- Epic by technology layer. Database, backend, frontend. Functionality is not covered end-to-end, it only supplies parts of it.

- Epic by product version. The product version is a set of properties from different epics. Unlike the epic, the version has a timeline as well.

- Epic by a customer (stakeholder) to which part of the functionality is being delivered. If you need to evidence the customer, evidence it in a separate attribute and organize the epics according to the procedures above.

- When the product assumptions change, the form of epic organization will not readjust. Adapt and select appropriate approaches as needed. Do not be afraid to work with the backlog and change it so you can orient quickly, you can choose other ways of epics organization and especially to have it transparent for the team as well as stakeholders.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/sebrendel/8155603332

- http://www.scaledagileframework.com/epic/

- http://www.scaledagileframework.com/portfolio-kanban/

Found this interesting? Share, please!

About the author: dusan kocurek.

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

What is an epic in agile? Complete guide with examples

Agile development is an iterative process that enables software development teams to accelerate their time to market by fostering and embracing a culture of continuous learning. Agile teams learn by doing.

In product development, the strategy and roadmap is based on data and insights from the market, which is always evolving. The product team must be dynamic enough to adapt to shifting requirements and user needs. This is a core agile value as outlined in the Agile Manifesto .

It’s not enough to anticipate user needs because they are ever-evolving. Agile development teams work in short, iterative sprints , which affords them the flexibility and pragmatism required to deliver complex products.

What is an epic?

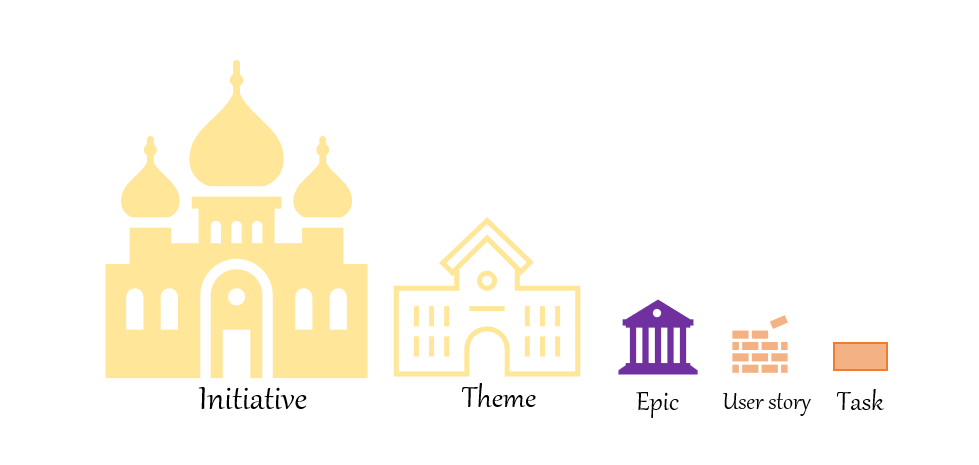

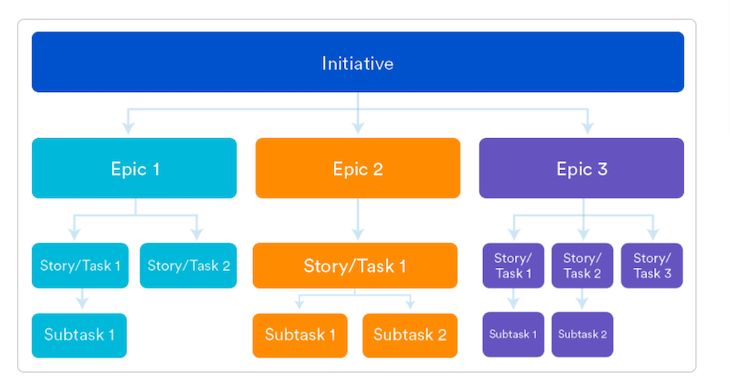

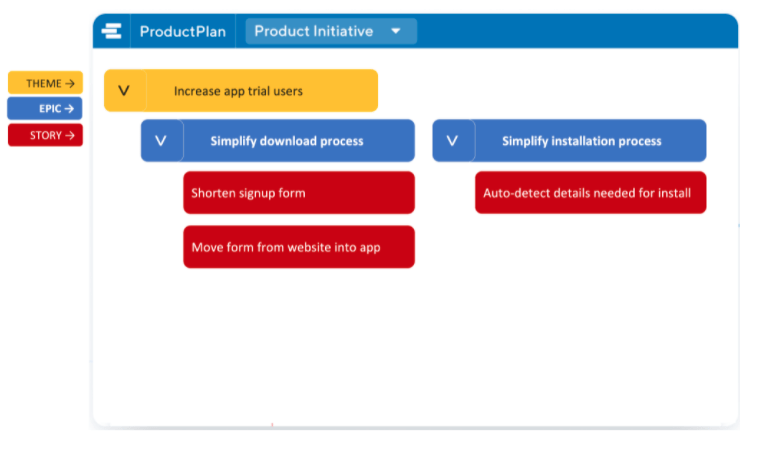

An epic is a feature or functionality consisting of multiple building blocks and scenarios. Epics are derived from themes or initiatives and can be segmented into smaller pieces called user stories .

An epic can span across multiple sprints, teams, and even projects. The theme, epic, and user stories share the same strategic goal at different levels of the focus area.

Consider the example of building a house. If an initiative is like building the ground floor, an epic is like creating a kitchen and a user story is like building a wall, with each brick being a task.

Agile development breaks down a broad product vision into small, achievable tasks that produce frequently updated results.

Like building a house, the product development lifecycle can feel overwhelming. The direction of where to start may not be apparent to everyone working on the product. But it helps to break down the larger initiative into several themes — for example, building the foundation and the ground floor.

You can break it down further into epics — e.g., building each room — and then even further to building a wall. This gives us a clearer picture of what we need to achieve today to make meaningful progress toward the strategic initiative .

In large organizations, where several cross-functional teams are involved in product development, epics help everyone get on the same page around development goals, dependencies, and priorities.

Epics vs. user stories vs. initiatives

Depending on the organization’s size, the product’s complexity, the composition of initiatives, themes, and epic may vary in dimensions. Smaller products or organizations may only have one top hierarchy. However, if the design of scale is used within the circumference of an organization, the basic idea is the same.

A product roadmap boils down to smaller, achievable tasks. In any product development cycle, multiple features concurrently fulfill users’ needs. But that doesn’t mean the product needs to be fully developed with all features complete at the time of launch .

A core value of agile development is quick delivery and learning by doing. Breaking the theme into various levels helps shorten the product development lifecycle from ideation to execution.

This segmentation also helps in prioritization by slicing the initiative into more manageable minimum viable products (MVPs) . The MVPs can be developed and launched to the user within a short period, allowing the team to learn and iterate, validate ideas, and adjust the roadmap as necessary.

Regardless of how you structure the hierarchy structure of themes/initiatives, epics, and user stories, each level is defined with a purpose.

Themes and initiatives

Themes and initiatives define the product vision. The big idea is segmented into strategic goals.

The purpose of the theme is to be the North Star, providing a clear picture of the entire organization’s focus area.

The initiative can be closing a market gap, addressing a pain point, innovation, market fit, etc.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

An epic is the actualization of the product roadmap. The initiative is further segmented into defined features to develop.

Epics create alignment between the organization and the product development when it comes to prioritization .

User stories

A user story is user-focused and driven by user value.

Even though the product vision and roadmap come from within the organization, development should always be completely user-centric. User stories help the development team empathize with the user and clarify the value produced as a result of the product from the customer’s perspective.

How to write an epic

An epic is a high-level requirement of a feature. When writing an epic, your goal is to align stakeholders with your product vision and roadmap. To achieve that alignment with clarity and focus, you should provide all the relevant information, including any dependencies, clarify any misunderstandings, and establish a clear direction with a measurable goal.

Collaboration is key to a good epic description. Though the product manager is responsible for writing an epic spec, they’re not expected to be an expert at all levels. When creating an epic spec document, collaborate with your team to discuss and align on solution design, UX design, and the customer journey. Bring in all the required knowledge and expertise early to avoid getting stuck later on.

What to include in an epic

Every development is different, so the epic specs will differ from product to product. Some epics include granular detail while others only highlight high-level requirements.

An epic should include at least the bare minimum information the product team requires to get started on user stories and prioritize tasks to solve the customer’s needs as efficiently as possible.

Introduction

The introduction should outline the “why” and the “what” — the reason for prioritizing and developing the feature and user pain points to solve. You should also include the metrics and KPIs for measuring the performance.

In addition, any documentation or early wireframes you can provide go a long way toward establishing a common understanding of the goal and path to successful delivery. Some things to consider:

- Summary of features and reasons for developing them

- Performance metrics and KPIs

- Links to specific documentation

- Marketing plans and legal requirements (if any)

- Early wireframes

Product requirements

An essential objective of the epic is to establish a shared understanding of the development goal. The epic should include the feature’s functional and nonfunctional requirements.

The product requirements documentation might mention availability in multiple languages or on multiple devices, for example.

Design requirements

You should always collaborate with the UX designer to write the design requirement. They are the expert and will surely have insights to share from their countless user test experiences.

Examples of product design requirements might include things like:

- Where to place search functionality for each device

- A request for a prototype to simplify future group discussions

Engineering requirements

You should strive for alignment with the target architecture while compiling the high-level requirement in an epic. Like the tech stack or solution design, consideration in the early stages will help you estimate more accurately and maximize efficiency down the line.

For example, let’s say the engineering team wants to create an API to integrate with some existing database functionality to fetch a list of songs. Investigating these opportunities during the initial stages of creating the epic helps you avoid incurring inadvertent technical debt .

KPI and metrics

KPIs guide every product development cycle. A concrete set of metrics and goals will help the teams focused and motivated to hit stated objectives.

KPIs should be tangible and measurable. A vague KPI is of no value and does not motivate action. At first, some KPIs may seem not measurable, but after aligning with data analysts, there is always a way to measure development value in numbers.

For example, increasing customer satisfaction is a good KPI, but a little vague. Instead, try adding metrics such as net promoter score (NPS) or the number of times a user interacts with a new functionality in one session.

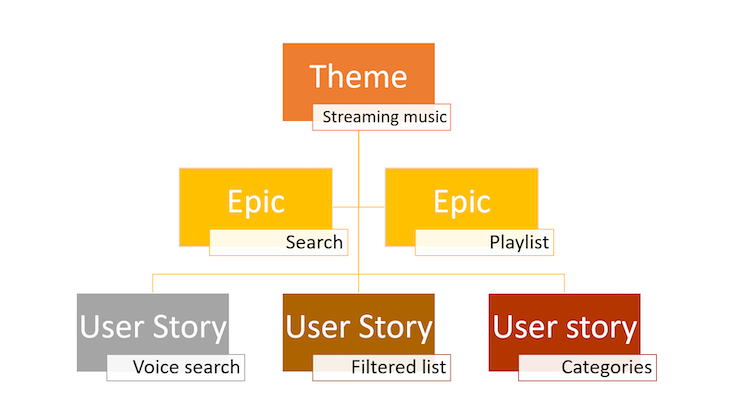

A real-world example of an epic

Let’s consider the example of a music streaming app to demonstrate how an epic is structured. Suppose you want to add search functionality to the app. The database contains more than 1 million songs from across the globe — a key differentiator for your product, so the search functionality is deemed critical to enable users to find whatever music they are looking for intuitively.

Using the epic template below, our epic would look something like this:

Keeping with this example, an epic spec document pertaining to the items populating the template above might read as follows:

The new search functionality will allow users to narrow down their search and offer suggestions to help them find the music they want to listen to instantly.

Our research shows that 86 percent of our user base is interested in the search functionality. Since the most commonly identified problem with searching music is that people can’t remember or recognize the song’s name, a voice search service shows the most considerable demand.

We expect this functionality will increase the number of songs played per user by 10 percent on average, which will result in approximately 30 percent additional time spent per month using the app.

- Users can initiate a search from multiple suitable pages in the app

- Users can begin a voice search

- AI integration in search functionality

- Customized search suggestions

- Should include tracking on each page

- Display search suggestions in a list filtered is different categories

- Design should work with accessibility rules

- New API’s to be built only in the new backend system

- Dependencies shared with the AI integration team

- Conversion rate: Clicks on the suggested list of songs

- Use of voice search: Avg. use per session per user

A good epic spec document will help you foster collaboration and achieve alignment across your team and your organization. Epics also make it easier to write user stories, slice down and prioritize the backlog, and run a smoother scrum .

In agile development, all the frameworks, structures, and processes are created with one principle: the ability to be flexible and deliver quickly to learn iteratively.

The main goal of any process or documentation is to create alignment, avoid misunderstanding, and minimize inadvertent technical debts while accelerating time to market.

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket generates product insights that lead to meaningful action

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #agile and scrum

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

5 lessons from helping 9 startups move to outcome-driven work

Learn five essential lessons from guiding nine startups to an outcome-driven, product-led approach, including niche focus, flexible frameworks, and decisive action.

Leader Spotlight: Slowing things down to run really fast, with Brian Bates

Brian Bates, Senior Vice President of Business Development at Lively Root, talks about how he works to scale small startups.

Building and scaling product teams in startups vs. large enterprises

When a product team is scaled correctly, it is well-equipped to meet unique challenges and opportunities in an ever-changing product landscape. Discover how to build and scale product teams effectively, no matter the size of your organization.

Crafting meaningful core values for your company

Core values provide all individuals within an organization a framework to make their own decisions on a day-to-day basis.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Pinterest

- Share through Email

What Is An Agile Epic? Best Practices, Template & Example

Agile epics are a crucial tool for grouping user stories into bigger initiatives and structure an agile backlog. Here are some pro tips on how you can use epics to their full potential.

Do you know the difference between an agile epic and a user story ? Or how to best use agile epics for your product requirements and product roadmap? If you’d like to learn how to use agile epics to your advantage, read on for my top seven tips and a template to start.

What Is An Agile Epic?

An agile epic is a useful tool in agile project management used to structure your agile backlog and roadmap.

Simply put, an agile epic is a collection of smaller user stories that describe a large work item. Consider an epic a large user story. For example, epics are often used to describe a new product feature or bigger piece of functionality to be developed.

An epic is the top informational level in an agile backlog. It contains several user stories and each user story in turn contains all the tasks required for implementation.

Agile epics are mostly used when a piece of work is too big to be delivered in a single sprint or iteration. If you use an epic to group your user stories for a new feature, it is easy to keep track of progress and know what percentage of work is completed versus outstanding.

Epics are usually written and maintained by the product owner or product manager.

7 Best Practices To Using Agile Epics

There is no set template for an agile epic. You can write it in any way you like as long as it helps with planning your work and communication with your agile teams and stakeholders.

Regardless if you use a scrum or kanban or a hybrid development process, epics will help you plan your work and report on it.

Here are some tips to make sure that your agile epics are most useful.

Stay in-the-know on all things product management including trends, how-tos, and insights - delivered right to your inbox.

- Your email *

- By submitting this form, you agree to receive our newsletter and occasional emails related to The Product Manager. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, please review our Privacy Policy . We're protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

1. Start With Epic Then Stories (Top Down)

Finding your epics can very usefully be done with a user story map . Your top level “Activity” in the user story map becomes an epic and the lower levels become the user stories, tasks, and acceptance criteria .

When you are developing a whole new product, starting with epics and fleshing them out in more detail as you go along, gives you an idea of the milestones completed and outstanding.

Often agile epics correspond to features or larger improvements (e.g. a redesign of part of your product), but it is entirely up to you how you want to structure your epics.

2. Name An Epic Well

When you name your agile epics, think about who will consume this information. For example, your agile development teams need to understand what they are building and your stakeholders also need to understand your progress.

Whereas a user story describes an end-user need, it’s good practice if the epic describes an outcome you want to achieve with it.

Consider these examples for epic names:

- Checkout flow V2

- Streamline checkout flow

- Increase conversion rate in checkout

The first name doesn’t describe at all what it is other than some kind of work on checkout. The second name is better as it describes that the checkout flow is to be streamlined. But the third name is even better as it includes an outcome that you want to achieve with this streamlining.

In agile management tools, like Atlassian’s Jira for example, epics can be used for filtering, grouping, and reporting. Therefore choosing a name that speaks for itself is important.

3. Make Your Epics The Right Size

An epic is usually used when work on a backlog item requires more than a single sprint to complete. An epic can break down into as many user stories as you like as long as you can keep track of the whole list.

An epic should be not too big and not too small. A rule of thumb would be an implementation timeframe between a few weeks and a few months. This is a good size for reporting on the percentage completed.

Making epics too big means that progress is very slow, percentages hardly increase over a two-week sprint and reporting is not meaningful. Also if an epic takes too long to implement, there are likely to be so many changes to requirements along the way that reporting progress almost becomes meaningless.

Making epics too small means that you will have a great number of them to juggle in your backlog or roadmap. It can become difficult to retain a high-level view of many smaller tasks. Also if epics are completed in a very short time (e.g. a single sprint), they just add additional overhead without providing much value.

4. Use Epics To Structure Your Backlog

Epics are an excellent way to structure a product backlog that usually consists of a very long list of user stories. Not every story requires to be included in an epic, as small pieces of work are simply completed within one sprint. But to structure bigger items of work into epics has two main benefits:

- It provides a high-level view of the big items in your backlog,

- As the size of an epic is made up of the addition of story points of all its user stories, epics also provide a comparison of the relative size of initiatives for prioritization .

The list of epics can also be used to create a high-level view of a product roadmap for senior management.

5. Use Epics To Coordinate Multiple Teams

Epics can be very useful to coordinate chunks of work across multiple agile software development teams. Combining work for multiple product teams in a single epic allows you to break down the reporting per team and track progress overall.

6. Include Success Metrics

When defining an epic it is worthwhile thinking about what success metric can be associated with it. Ultimately all product deliverables serve to bring value to end-users. Including a success metric in your epic means that development team members and stakeholders all understand what you are trying to achieve with this piece of work.

Some companies use OKRs to set quarterly goals. Referencing an OKR metric in an epic is an excellent way to tie an epic back to the business objectives.

7. Make Epics Flexible In Scope

As an epic describes a high-level work item continuing over several weeks or months, it is likely that new insight arises or new technical complications are discovered as work progresses. Therefore an epic needs to be flexible in scope.

The scope of an epic is defined by the scope of its associated user stories, usually measured in story points. As new requirements emerge, new user stories may be added and the scope of the epic increases.

Related Read: Best Agile Product Management Software

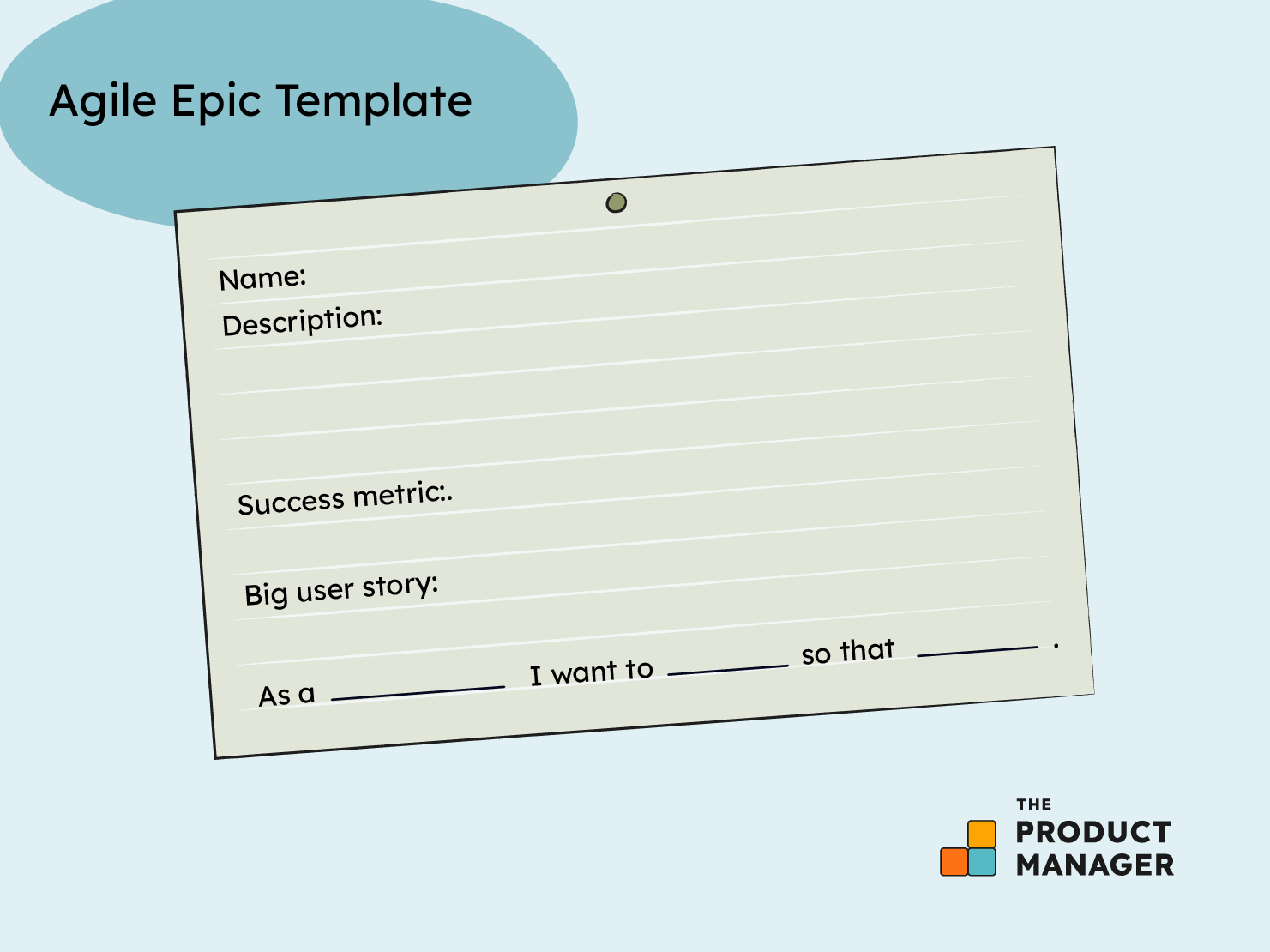

Agile Epic Template

There is no set format for an epic, but a few things are useful as described above.

- Choose a good name that speaks for itself.

- In the description, give a rough outline of what the epic encompasses. Reference any company goals to illustrate how this ties in with business priorities.

- The success metric describes specifically what will be measured after completion of this epic.

- Big user story denotes a user story at the level of the whole epic. This is very useful in order to document how this epic delivers a better user experience.

More Articles

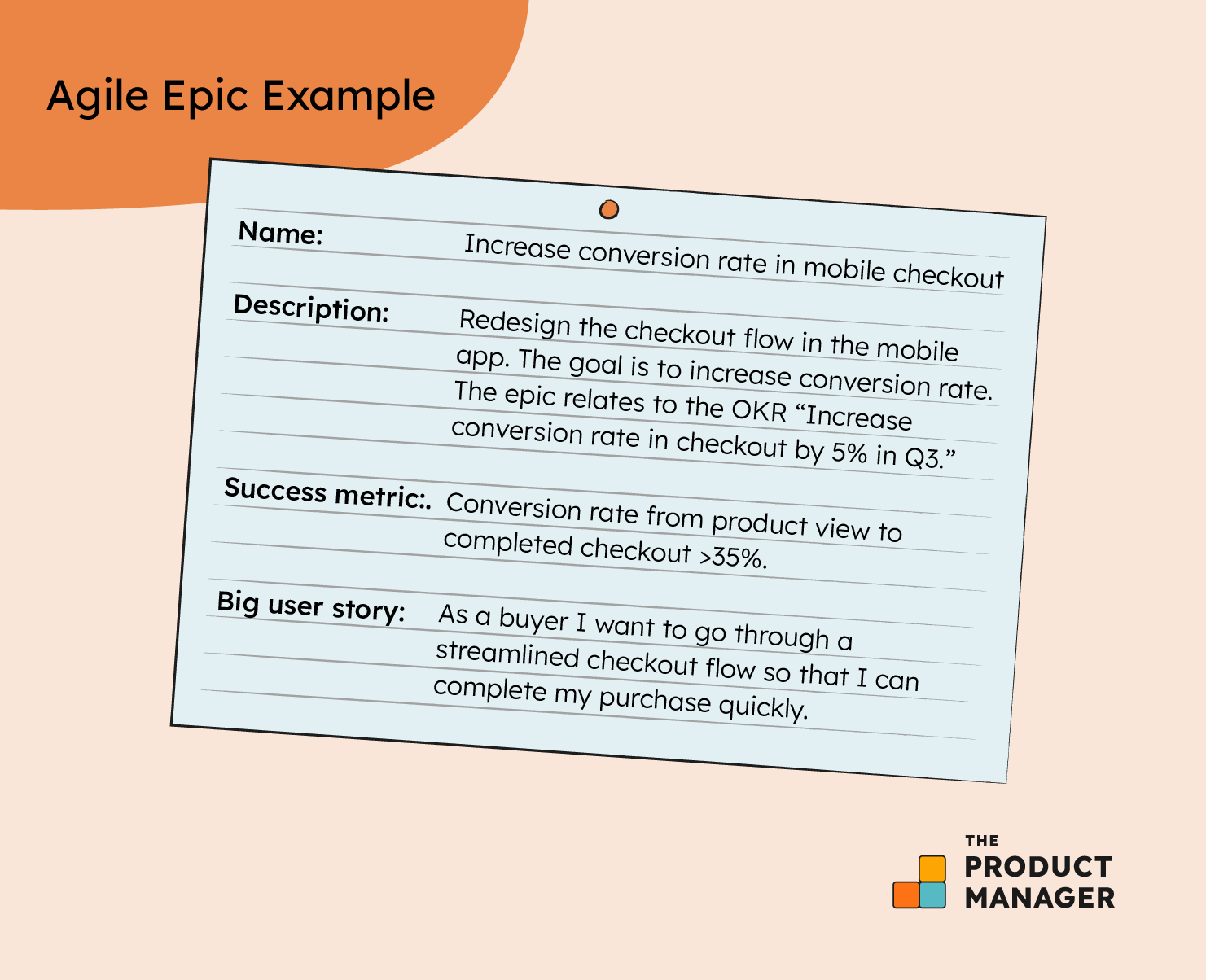

Product strategy: what it is, and how to nail it, the top 10 ux design trends of 2024, 13 brainstorming techniques every product manager needs to know, agile epic example.

Here is an example of an epic for a new streamlined mobile app checkout flow in order to increase conversion.

Within this epic, we could then have user stories such as:

- Integrate Apple Pay ( “As a buyer, I want to pay with one touch on my phone so that I can complete checkout quickly” )

- Use billing address as shipping address per default ( “As a buyer, I want to enter my address details only once so that I can complete checkout quickly” )

Agile epics are a flexible tool in your agile toolkit. When starting a major new development, think about the big pieces of work required to complete it and define a few epics. You can then create all your user stories within these epics as you go along and retain a much better overview than in an unstructured backlog.

Epics can be used in many ways. I would be very interested to learn how you use epics in your agile teams in the comments.

For more articles with hands-on practical information about a great variety of product management topics—including agile methodology!— subscribe to our newsletter .

Also Worth Checking Out:

- Product Pricing: Value-Based Strategy, Software Packaging with Dan Balcauski

- 4 Best Online Agile Product Management Certifications

Developing a Winning Epic Hypothesis Statement that Captivates Stakeholders using SAFe

The Scaled Agile Framework®, or SAFe, was created in 2011 and built upon the classic Agile manifesto by incorporating key ideas from the Lean methodology.

Organisations using this framework can accomplish a wide range of advantages, according to SAFe developers, such as:

20-50% increases in productivity

30-75% quicker time to market

10-50%Increases in employee engagement

Assume that in order to reap the benefits of project management, your Executive Action Team (EAT) wants to embrace a Lean-Agile mentality. If so, it needs to become proficient in crafting and presenting an Epic Hypothesis Statement (EHS). Check out the Agile certification course to learn more.

Creating a strong EHS and persuading your stakeholders to embrace your bold idea are crucial to attaining business agility and optimising development procedures. On the other hand, neglecting to do so will impede your pipeline for continuous delivery and hinder you from effectively creating functional software.

It’s imperative that you nail your EHS pitch because there is a lot riding on it. We’ve developed this useful tool to assist you pitch your Epic Hypothesis Statement to your EAT in order to support these efforts.

Table of Contents

What Is an Executive Action Team (EAT)?

One of the cross-functional teams in the SAFe framework is the Executive Action Team (EAT). This group drives organisational transformation and eliminates barriers to systemic advancement. Additionally, the EAT will hear your EHS and choose whether or not to add it to the Epic queue.

The idea that change must originate at the top is one of the fundamental tenets of the lean-agile approach. An effective EHS pitch will pique the interest of Executive Action Team stakeholders and persuade them to adopt your Epic Hypothesis Statement.

What Is an Epic Hypothesis Statement (EHS)?

A comprehensive hypothesis that outlines an epic or sizable undertaking intended to overcome a growth impediment or seize a growth opportunity is called the Epic Hypothesis Statement (EHS).

Epics are typically customer-facing and always have a large scale. They need to assist a business in meeting its present requirements and equip it to face obstacles down the road.

The Epic Hypothesis Statement (EHS) is typically delivered to the EAT in the style of an elevator pitch: it is brief, simple, and concise, although the statement itself will be highly thorough.

Key Components of an Epic Hypothesis Statement

The Portfolio Kanban system’s initial funnelling phase is expanded upon in the Epic Hypothesis Statement. The concept started out as just one, like “adding self-service tools to the customer’s loan management portal.”

You must refine this fundamental concept into a fully realised endeavour in your role as the Epic Owner. In the event that your theory is verified, you must also describe the anticipated advantages the firm will enjoy. Your EHS also has to have leading indications that you can track as you move toward validating your hypotheses.

Let’s expand on the example of the self-service tool.

You could expand on the basic premise of integrating self-service capabilities into the loan management portal that is visible to customers if you wanted to develop an EHS. Indicate which specific tools you want to use and how they will enhance the client journey in your explanation of the initiative.

For example, the following could be considered expected benefit outcomes of this initiative:

- A reduction in calls to customer service

- Better customer satisfaction and engagement

- improved image of the brand

It’s true that some advantages would be hard to measure. Complementary objectives and key results (OKRs) are therefore quite important to include in your EHS since they will support your pitch to your EAT regarding the benefits of your EHS.

Pitching Your EHS

It’s time to submit your finished Epic Hypothesis Statement to the EAT for consideration. You need to do the following if you want to involve your stakeholders.

Make Use of Powerful Visuals

The Agile manifesto and the Portfolio Kanban system both stress the value of visualisation. Including images in your EHS pitch demonstrates to your audience that you understand these approaches in their entirety and aids with their understanding of your concept.

Explain the Applicability of Your OKRs

Your suggested endeavour and the OKRs you’ve chosen should be clearly connected. Nevertheless, it never hurts to emphasise this point by outlining how each OKR you select will assist in monitoring the advancement of your theory’s proof.

Close the Deal with a Powerful Concluding Statement

Your Epic Hypothesis Statement is ultimately a sales pitch. Handle it as such by providing a succinct yet captivating conclusion. Go over the possible advantages of your project again, and explain why you think it will help the business achieve its short- and long-term objectives.

The Perfect EHS Pitch Starts with a Great Idea

By utilising the aforementioned strategies and recommendations, you can create an extensive EHS that grabs the interest of your stakeholders. But never forget that the quality of your idea will determine how well your pitch goes.

Work with your EAT to integrate ideas that have a significant impact into your workflow for managing your portfolio. Next, choose a notion you are enthusiastic about and develop your hypothesis around it. You’ll have no trouble crafting the ideal EHS pitch.

Conclusion To learn more about Agile and SAFe, check out the SAFe Agile certification course online.

What is Interruption Testing?

Approaches for being a lead business analyst, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Related Articles

Intelligence and Curiosity- How you can master POETIC leadership in Agile

How to handle Bugs, Incidents, Problems, and Service Requests in Agile

What Are The Differences Between PSM And CSM?

The Difference Between PRINCE2 and SCRUM

agility at scale

- Team and Technical Agility Assessment Service

- Agile Product Delivery Assessment Service

- Case Studies

- Agile Leadership

- Agile Planning

- Agile Practices

- Agile Requirements Management

- Distributed Teams

- Large Scale Scrum (LeSS)

- Lean and Agile Principles

- Organizational Culture

- Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe)

- Scaling Agile

Implementing SAFe: Requirements Model (v6)

Table of Contents

What is the SAFe Requirements Model?

The SAFe Requirements Model is a hierarchical structure that manages and organizes requirements in large-scale Agile projects.

The SAFe Requirements Model helps organizations align their business objectives with their development efforts, ensuring that teams deliver value incrementally while focusing on the overall strategy. The SAFe Requirements Model is organized into three levels:

- Epics are high-level initiatives representing significant organizational value and span multiple planning intervals.

- Features are mid-level requirements that provide more detailed descriptions of the functionality needed to achieve the goals set forth by the Epics.

- Stories are the smallest units of work, representing individual tasks to be completed by Agile teams, typically within a single iteration.

What are SAFe Epics?

Portfolio Epics are large-scale business initiatives that drive change and provide substantial business benefits.

The strategic investment themes drive all new development, and requirements epics are derived from these decisions.

Epics are large-scale development initiatives that realize the value of investment themes.

Epics in the SAFe Requirements Model are large-scale, cross-cutting initiatives that encapsulate significant development efforts and provide substantial value to the organization or end-users. They can be business epics, which focus on delivering customer or user value, or enabler epics, which address technical or architectural enhancements to support the development of business epics. Epics typically span multiple Agile Release Trains (ARTs) and Planning Intervals (PIs), requiring collaboration and coordination among various teams.

Epics are the highest-level requirements artifact used to coordinate development. In the requirements model, they sit between investment themes and features.

- Epics are usually driven (parented by) investment themes. However, some epics can be independent (they do not require a parent to exist).

- Epics are not implemented directly. Instead, they are broken down into Features and User Stories, which the teams use for actual coding and testing.

- Epics are not directly testable. They are tested through the acceptance tests associated with the features and stories that implement them.

What are the key elements of a SAFe Epic Statement?

An Epic Statement comprises a brief description, the customer or business benefit, and the success criteria.

When documenting epics in SAFe, the following key elements are included:

| Epic ID | A unique identifier for easy tracking and reference. |

| Epic Title | This concise, descriptive title summarizes the epic’s main objective. |

| Epic Description | A high-level description that provides context and clarifies the intended outcome or functionality. |

| Business Outcome Hypothesis | A statement articulating the expected value or benefits to the organization or customers from implementing the epic, usually including quantifiable metrics. |

| Leading Indicators | Early signals or metrics provide insight into the epic’s progress and success. |

| Acceptance Criteria | A list of conditions for the epic to be considered complete and accepted by stakeholders, defining the desired functionality, quality, and performance. |

| Dependencies | Any relationships or dependencies with other epics, features, or components must be addressed or coordinated for successful implementation. |

| Priority | The relative importance of the epic within the portfolio backlog is used to guide investment decisions and the allocation of resources. |

| Size or Effort Estimate | A rough estimation of the effort or complexity involved in implementing the epic is typically expressed in story points or team weeks to help inform capacity planning and scheduling. |

What are the differences between SAFe Business Epics and Enabler Epics?

Business Epics delivers direct business value, while Enabler Epics provides the technological or architectural advancements necessary to support business Epics.

In the SAFe Requirements Model, the difference between enabler epics and business epics lies in their focus and purpose:

- Business Epics: These are large-scale initiatives aimed at delivering customer or user value, addressing new features, products, or services that have a direct impact on the organization’s business outcomes. Business epics typically focus on solving customer problems, capturing market opportunities, or improving the user experience.

- Enabler Epics: These epics focus on technical, architectural, or process enhancements that support the development and delivery of business epics. Enabler epics may not provide direct customer value but are essential for improving the organization’s underlying infrastructure, technology, or capabilities, making it easier to deliver business value more efficiently and effectively.

Business Epics and Enabler Epics in SAFe serve different but equally important roles. Business Epics are initiatives that deliver direct customer or business value. They represent substantial investments and have a clear tie to business outcomes. On the other hand, Enabler Epics support the implementation of Business Epics. They represent the necessary technological or architectural advancements that facilitate the delivery of business value. While they may not directly impact the customer, they are vital in realizing Business Epics.

What is the SAFe Portfolio Backlog?

The Portfolio Backlog is a prioritized list of Portfolio Epics.

The Portfolio Backlog within SAFe serves as the repository for upcoming Portfolio Epics. It is a prioritized list of Epics, with those at the top representing the highest priority and most significant initiatives that need to be undertaken. This backlog helps to align the organization around the most important strategic initiatives, allowing for effective decision-making and allocation of resources across the portfolio.

The Portfolio Backlog provides a clear picture of the organization’s direction and value delivery at the Portfolio level, guiding the allocation of resources, funding, and coordination of efforts across multiple Agile Release Trains (ARTs) and Solution Trains to align with the overall strategy.

What are SAFe Product Features?

SAFe Product Features are serviceable system components that provide business value and address user needs.

Features are described as follows:

Features are services provided by the system that fulfill stakeholder needs.

Within the realm of SAFe, Product Features are distinct pieces of functionality that are of value to the user or the business. They are typically larger than individual User Stories and represent services the system provides that fulfill specific user needs. Features form a critical part of the Program Backlog.

In describing the features of a product or system, we take a more abstract and higher-level view of the system of interest. In so doing, we have the security of returning to a more traditional description of system behavior, the feature.

Features as ART-Level Artifacts

A “Feature” in the SAFe Requirements Model is a high-level, functional requirement that delivers value to the end-user or customer. Features are typically part of a larger product or system and are aligned with the goals of a specific Planning Interval (PI), which usually spans 8-12 weeks.

Features live above software requirements and bridge the gap from the problem domain (understanding the needs of the users and stakeholders in the target market) to the solution domain (specific requirements intended to address the user needs).

Features are usually expressed as bullet points or, at most, a couple of sentences. For instance, you might describe a few features of an online email service like this:

Enable “Stars” for marking important conversations or messages, acting as a visual reminder to follow up on a message or conversation later. Introduce “Labels” as a “folder-like” metaphor for organizing conversations.

Feature Statement and Template

In the SAFe Requirements Model, a feature is typically documented using the following:

| Title | A concise summary of the feature’s purpose. |

| Description | A brief overview of the desired outcome. |

| Benefit Hypothesis | Expected value or benefit statement. |

| Acceptance Criteria | Conditions for completion and stakeholder acceptance. |

| Dependencies | Related features, components, or teams to coordinate. |

| Priority | Feature’s importance within the PI backlog for planning. |

| Size/Effort | Rough implementation effort estimate for capacity planning. |

What are the differences between SAFe Features and SAFe Capabilities?

SAFe Features are system functionality that provides value to users, while SAFe Capabilities are higher-level functionalities that provide value to customers and stakeholders.

SAFe distinguishes between Features and Capabilities based on their level of abstraction and scope. Features at the Program Level are functionality increments that address user needs and deliver value. They are smaller in scope and more detailed compared to Capabilities. On the other hand, Capabilities are placed at the Large Solution Level, representing higher-level functionalities that deliver value to customers and stakeholders. They are typically bigger, encompass broader functionality, and may require multiple Agile Release Trains (ARTs) to implement.

The main difference between capabilities and features in the SAFe Requirements Model lies in their scope and granularity:

- Capabilities : Capabilities are high-level functional requirements that describe essential building blocks of a solution in the Large Solution level of the SAFe Requirements Model. They span multiple Agile Release Trains (ARTs) and represent the functionality needed to deliver value to end-users or customers. Capabilities provide a broader perspective on the solution and help coordinate efforts among multiple ARTs working together.

- Features : Features are smaller, more granular functional requirements at the Program level in the SAFe Requirements Model. They describe specific functionalities or enhancements that deliver value within a single Agile Release Train (ART). Features are derived from capabilities and are broken down into user stories, which Agile teams implement during iterations.

In summary, capabilities are high-level, cross-ART functional requirements for large-scale solutions. At the same time, features are more granular, ART-specific requirements that deliver value as part of a product or system.

How are SAFe Features tested?

SAFe Features are tested through iteration testing, integration testing, and system demos.

The SAFe approach to testing Features involves three specific practices, ensuring functionality and integration, and they are:

- Iteration Testing , where each feature is tested during the iteration it’s developed.

- Integration Testing is where Features are tested in conjunction with other system elements to ensure they work together properly.

- System Demos allow stakeholders to inspect the integrated system and provide feedback, enabling further refinement and validation of Features.

Story-level testing ensures that methods and classes are reliable (unit testing) and stories serve their intended purpose (functional testing). A feature may involve multiple teams and numerous stories. Therefore, testing feature functionality is as crucial as testing story implementation.

Moreover, many system-level “what if” considerations (think alternative use-case scenarios) must be tested to guarantee overall system reliability. Some of these can only be tested at the full system level. So indeed, features, like stories, require acceptance tests as well.

Every feature demands one or more acceptance tests, and a feature cannot be considered complete until it passes.

What are Nonfunctional Requirements?

Nonfunctional Requirements (NFRs) are specifications about system qualities such as performance, reliability, and usability.

In SAFe, Nonfunctional Requirements (NFRs) denote the ‘ilities’ – system attributes like scalability, reliability, usability, and security. Unlike functional requirements, which define what a system does, NFRs describe how it does it. These are critical factors that shape system behavior and often have system-wide implications. NFRs are a constant consideration throughout the development process, helping to ensure that the system meets the necessary standards and delivers a satisfying user experience.

Nonfunctional Requirements as Backlog Constraints

From a requirements modeling perspective, we could include the NFRs in the program backlog, but their behavior tends to differ. New features usually enter the backlog, get implemented and tested, and then are removed (though ongoing functional tests ensure the features continue to work well in the future). NFRs restrict new development, reducing the level of design freedom that teams might otherwise possess. Here’s an example:

For partner compatibility, implement SAML-based single sign-on (NFR) for all products in the suite.

In other cases, when new features are implemented, existing NFRs must be reconsidered, and previously sufficient system tests may need expansion. Here’s an example:

The new touch UI (new feature) must still adhere to our accessibility standards (NFR).

Thus, in the requirements model, we represented NFRs as backlog limitations.

We first observe that nonfunctional requirements may constrain some backlog items while others do not. We also notice that some nonfunctional requirements may not apply to any backlog items, meaning they stand alone and pertain to the entire system.

Regardless of how we view them, nonfunctional requirements must be documented and shared with the relevant teams. Some NFRs apply to the whole system, and others are specific to a team’s feature or component domain.

How are Nonfunctional Requirements tested?

Nonfunctional Requirements are tested through methods like performance testing, usability testing, and security testing.

The testing of Nonfunctional Requirements (NFRs) in SAFe involves specialized techniques corresponding to each type of NFR. For instance, performance testing measures system responsiveness and stability under varying workloads. Usability testing assesses the system’s user-friendliness and intuitiveness. Security testing evaluates the system’s resistance to threats and attacks. By testing NFRs, teams ensure that the system delivers the right functionality and provides the right quality of service, thereby maximizing user satisfaction and trust.

Most nonfunctional (0…*) requirements necessitate one or more tests. Instead of labeling these tests as another form of acceptance tests and further overusing that term, we’ve called them system qualities tests. This name implies that these tests must be conducted periodically to verify that the system still exhibits the qualities expressed by the nonfunctional requirements.

What is the SAFe ART Backlog?

The SAFe Program Backlog is a prioritized list of features awaiting development within an Agile Release Train.

Within SAFe, the Program Backlog serves as a holding area for upcoming Features, which are system-level services that offer user benefits and are set to be developed by a specific Agile Release Train (ART). These Features are prioritized based on their value, risk, dependencies, and size. The backlog helps provide transparency and drives PI planning, guiding the ART toward achieving the desired outcomes.

Features are brought to life by stories. During release planning, features are broken down into stories, which the teams utilize to implement the feature’s functionality.

What are SAFe User Stories?

SAFe User Stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the capability, usually a user or customer.

User Stories within SAFe are a tool for expressing requirements. They focus on the user’s perspective, facilitating a clear understanding of who the user is, what they need, and why they need it. User Stories promote collaboration and customer-centric development by emphasizing value delivery and verbal communication.

What is the definition of a SAFe User Story?

A SAFe User Story is a requirement expressed from the end-user perspective, detailing what the user wants to achieve and why.

In SAFe, a User Story is an informal, natural language description of one or more features of a software system. It is centered around the end-user and their needs, providing context for the development team. User stories are the agile alternative to traditional software requirements statements (or use cases in RUP and UML), serving as the backbone of agile development. Initially developed within the framework of XP, they are now a staple of agile development in general and are covered in most Scrum courses.

In the SAFe Requirements Model, user stories replace traditional software requirements, conveying customer needs from analysis to implementation.

A user story is defined as:

A user story is a concise statement of intent that outlines what the system needs to do for the user.

Typically, user stories follow a standard (user voice) format:

As a <role>, I can <activity> so that <business value>.

This format encompasses elements of the problem space (the delivered business value), the user’s role (or persona), and the solution space (the activity the user performs with the system). For example:

“As a Salesperson (<role>), I want to paginate my leads when I send mass e-mails (<what I do with the system>) so that I can quickly select a large number of leads (<business value I receive>).”

What are the 3-Cs of user stories?

The 3-Cs of user stories refer to Card, Conversation, and Confirmation.

In the realm of SAFe, these three Cs are fundamental to the creation and execution of User Stories. The “Card” typically represents the User Story, written in simple language. “Conversation” signifies the collaborative discussions that clarify the details of the User Story and refine its requirements. “Confirmation” establishes acceptance criteria to determine when the User Story is completed successfully. This trio of components ensures clarity and shared understanding in value delivery.

- “Card” refers to the two or three sentences that convey the story’s intent.

- “Conversation” involves elaborating on the card’s intent through discussions with the customer or product owner. In other words, the card also signifies a “commitment to a conversation” about the intent.

- “Confirmation” is the process by which the team, via the customer or customer proxy, determines that the code fulfills the story’s entire intent.

Note that stories in XP and Agile are often manually written on physical index cards. However, agile project management tools usually capture the “card” element as text and attachments in the enterprise context. Still, teams frequently use physical cards for planning, estimating, prioritizing, and visibility during daily stand-ups.

This straightforward alliteration and Agile’s passion for “all code is tested code” demonstrates how quality is achieved during code development rather than afterward.

The SAFe Requirements model represents the confirmation function as an acceptance test verifying that the story has been implemented correctly. We’ll refer to it as story acceptance tests to distinguish it from other acceptance tests and consider them an artifact separate from the (user) story.

The model is explicit in its insistence on the relationship between the story and the story acceptance test as follows:

- In the one-to-many (1..*) relationship, every story has one (or more) acceptance tests.

- It’s done when it passes. A story cannot be considered complete until it has passed the acceptance test(s).

Acceptance tests are functional tests that confirm the system implements the story as intended. Story acceptance tests are automated whenever possible to prevent the creation of many manual tests that would quickly hinder the team’s velocity.

What is the difference between SAFe Enabler Stories and SAFe User Stories?

SAFe Enabler Stories support the exploration, architecture, infrastructure, and compliance activities needed to build a system, unlike User Stories, which focus on end-user functionality.

The main difference between an enabler user story and a typical user story in the SAFe Requirements Model lies in their focus and purpose:

- Enabler Story: An enabler story represents work needed to support the development of a product or system but does not necessarily deliver customer value directly. Enabler user stories are used to address technical or architectural needs, reduce technical debt, or improve infrastructure. They are often larger and more complex than typical user stories, as they address non-functional requirements crucial for the product’s success.

- User Story: A typical user story represents a specific feature or functionality that delivers value to the customer or end-user. Typical user stories are more focused and granular than enabler user stories, describing specific actions or behaviors the user can perform with the product. They are usually smaller and more straightforward than enabler user stories, making them easier to estimate and prioritize.

Enabler Stories in SAFe facilitate the technical aspects of the system under development, such as architectural advancements or exploration activities. They differ from User Stories, which are primarily concerned with user-facing functionalities. Although Enabler Stories do not directly deliver user-valued functionality, they are vital for the evolution of the system and the delivery of future user value.

What are User Story sub-tasks?

User Story sub-tasks are smaller, manageable tasks derived from a User Story to facilitate its implementation.

Sub-tasks provide a way to break down a User Story into smaller, actionable pieces of work. These smaller tasks make the implementation more manageable and provide a clear path to completion. Sub-tasks can be assigned to different team members and tracked separately, providing a granular view of progress toward completing the User Story.

To ensure that teams fully comprehend the work required and can meet their commitments, many agile teams adopt a detailed approach to estimating and coordinating individual work activities necessary to complete a story. This is done through tasks, which we’ll represent as an additional model element:

Tasks implement stories. Tasks are the smallest units in the model and represent activities specific team members must perform to achieve the story. In our context:

A task is a small unit of work essential for completing a story.

Tasks have an owner (the person responsible for the task) and are estimated in hours (typically four to eight). The burndown (completion) of task hours indicates one form of iteration status. As suggested by the one-to-many relationship shown in the model, even a small story often requires more than one task, and it’s common to see a mini life cycle coded into a story’s tasks. Here’s an example:

- Task 1: Define acceptance test—Josh, Don, Ben

- Task 2: Code story—Josh

- Task 3: Code acceptance test—Ben

- Task 4: Get it to pass—Josh and Ben

- Task 5: Document in user help—Carly

In most cases, tasks are “children” of their associated story (deleting the story parent deletes the task). However, for flexibility, the model also supports stand-alone tasks and tasks that support other team objectives. This way, a team need not create a story to parent an item like “install more memory in the file server.”

What are User Story Acceptance tests?

User Story Acceptance tests are predefined criteria that a User Story must meet to be considered complete.

Acceptance tests for User Stories in SAFe provide clear, specific criteria determining when the story is done. These criteria are defined by the Product Owner in collaboration with the team and quality specialists and are based on the user’s expectations. They ensure the delivered functionality meets the desired value and quality, driving user satisfaction.

What are User Story Unit Tests?

User Story Unit Tests are low-level tests designed to verify the functionality of individual components of a User Story.

Unit tests in the context of User Stories involve testing individual components or units of the software to ensure they perform as expected. Developers typically create these tests during the implementation of the User Story. They form the first line of defense in catching and correcting defects, ensuring the integrity of the codebase, and promoting high-quality delivery.

Unit tests verify that the smallest module of an application (a class or method in object-oriented programming; a function or procedure in procedural programming) functions as intended. Developers create unit tests to check that the code executes the logic of the specific module. In test-driven development (TDD), the test is crafted before the code. Before a story is complete, the test must be written, passed, and incorporated into an automated testing framework.

Mature agile teams employ extensive practices for unit testing and automated functional (story acceptance) testing. Moreover, for those in the process of implementing tools for their agile project, adopting this meta-model can provide inherent traceability of story-to-test without burdening the team. Real Quality in Real Time

The fusion of crafting a streamlined story description, engaging in a conversation about the story, expanding the story into functional tests, augmenting the story’s acceptance with unit tests, and automating testing are how Scaled Agile teams achieve top-notch quality during each iteration. In this manner: Quality is built in, one story at a time. Ongoing quality assurance is accomplished through continuous and automated execution of the aggregated functional and unit tests.

How are Stories used in User Research or Data Science contexts?

Stories in User Research or Data Science represent hypotheses or questions about user behavior that need to be answered using data.

In User Research or Data Science, stories often take the form of hypotheses or research questions about user behavior. These stories guide the research process, providing clear objectives and helping to structure the analysis. By focusing on the user and their needs, these stories promote a user-centric approach to data analysis, helping to uncover meaningful, actionable insights.

Research (User Research, Data Science Research, etc.) has become integral to software development in today’s data-driven landscape. Like traditional software development, research activities also benefit from breaking work into smaller, manageable tasks. Although not officially part of the SAFe Requirements Model, we have devised a variation on the user story to address this unique aspect of data science projects. This document integrates with the team level in SAFe, ensuring that data science work aligns with Agile principles and practices.

What is a hypothesis test?

A hypothesis test is a statistical method used to make decisions or draw conclusions about population parameters based on sample data.

Within the statistical domain, hypothesis testing serves as a cornerstone methodology. It’s a process that allows analysts to test assumptions (hypotheses) about a population parameter. It involves formulating a null and alternative hypothesis, choosing a significance level, calculating the test statistic, and interpreting the results. This technique enables uncertainty-free decision-making, allowing organizations to draw data-driven conclusions and make informed decisions.

What is a hypothesis test in an Agile context?

A hypothesis test in an Agile context is a method used to validate assumptions about user behavior, system performance, or other product aspects based on collected data.