We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Time Management

Importance of Lesson-Planning Essay Examples

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Time Management , Education , Time , Teaching , Learning , Students , Goals , Planning

Words: 2500

Published: 02/02/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Introduction

A lesson plan is a framework for any lesson that a teacher has to compile before attending a class. The lesson plans are the products of a teacher’s thoughts about their classes including what goals they hope to achieve at the end of their classes and gives the different methods/ways of achieving the goals and most of the lesson plans are in written form (O'Bannon, 2008).

Importance of lesson planning

Lesson planning is of great significance to both the learner and the teacher in very many ways. The lesson plan acts as a guide to the teachers in order to efficiently teach the same subject and topic for a presentation. The plan therefore acts as a road map to the teaching process. It therefore keeps the teachers on track in order to accomplish the lesson objectives. In some other cases, through the use of the lesson plans, the teachers are able to achieve a logical content arrangement which in turn makes the lesson to be sequential thus improving the learning teaching process through logical impact of the instructions (O'Bannon, 2008). The lesson plan is significant for enabling the early preparation of teachers making a smooth running of the lesson, this happens when the lesson plan has been effectively organized. The early preparation of the teacher enhances effective content delivery and arrangement of all the required equipment and resources for facilitating the learning of that specific content. Some of the resources and equipment that would be organized prior to the lesson involve computers, projectors, availing hand outs and the preparation of the white writing boards and even the semblance of pens. The lesson planning process is important since it adequately provides an evaluation room and process for the teachers in their teachings and resource use. This is in line with the various components of lesson plans which include the objectives, the instructional activities and assessment/evaluation of the teaching process (Mitchell, Diana, & Stephen, 1999). A lesson plan is important in ensuring time management. Through the use of lesson plans, a teacher is able to be guided by the time limits that are provided against each and every activity that is to be carried out throughout the whole lesson, sticking to the provided time limits enable the students and teachers not to exceed the timeline thereby saving more time for other activities. Each time that has been allocated for each particular learning content is professionally utilized by the teacher thus enhancing a time balance during the teaching-learning process. Through the use of lesson plans, the teacher is able to realize the use of varied activities throughout the lesson. The lesson plan enlists the varied communication and instructional activities that a teacher should engage students in during the class time. Such learning activities include questions and answers, formation of groups for discussions, practicum, discussions, presentations and argumentative statements. Through this, the learners learning ability is boosted and thus learning becomes effective and efficient due to the application of a variety of practices within the single lesson framework. Lesson planning is important in the sense that the plans at times act as the memory banks for the teachers. Since the plans have kind of short notes written on them regarding the subject content to be taught, the teacher might refer to them at the time of memory lapse. This helps the teachers not to give irrelevant or rather suspicious instructions to the students. It therefore further act as a memory defense and a point of reference for the teachers while teaching. Lesson planning is a professional requirement for all teachers. A lesson plan is therefore a professional document that a practicing teacher or rather a teacher trainee needs to posses in order to deliver and work within their professional requirements. The ability of a teacher to make a lesson plan enhances the reliability and credibility of such a teacher in the professional teaching field. Through lesson planning, the teacher is able to carry out an assessment of whether the lesson objectives have been achieved by creating and testing a balance between what the objectives of the lesson were and the probable knowledge that has been gained throughout the lesson time thus enabling the teacher to assess the importance and effectiveness of different strategies and resources in achieving the varied educational goals. Lesson planning is a basis of future planning thus increasing the teacher’s future performance in the delivery of the content to learners. The content that has been taught to a particular group at an earlier date can be delivered to a next group of learners by gaining reference to the already existing lesson plans and short notes as the benchmark (Wong, 1998).

Whether your search query is ' write my paper free ' or 'get me a custom paper', please contact us and we'll do our best to help!

The teaching learning context

The teaching learning context in this case involves a case of children around the age of eight at the lower grade level of learning who are learning more than one language basically English language and other foreign languages. This is basically evident by the presence of writings on the wall marts in a foreign language seemingly Chinese with its relevant translation into the English language. The theories of second language acquisition demand that the learning takes place gradually with limited output during the initial stages of learning new words. In establishing a lesson plan therefore, I would prefer the use of simple models that seem basic such as cups, bowls, spoons and troughs as the learning resources since they are the basic materials that the learners are used to and thus are able to initialize their meanings at a faster rate. This depends on the theory of second language acquisition which states that the progress in learning should be from the less demanding vocabulary related activities towards the complex ones. Vocabulary learning becomes more effective when learners engage themselves with small work groups just like the ones on the wall marts since they are mastered first (Barcroft, 2001). The methodology of learning foreign languages is largely based on the theory stating that it concentrates on simple words with their translations are effective methods of learning and should be reinforced together with relevant together with pictures and pronunciation with maximum avoidance of elements that would distract the process of vocabulary learning such as sentence building at the beginning of the language learning stage. (Nation, 2001) In establishing a lesson plan for such a class, interactions would be a major learning activity since the second language transfer is primarily based on the principles of social interactions with the learners having a comprehensive input to the learning process.

The elements of lesson planning

The core of a lesson is the task and thus the task is organized into varied categories bearing in mind the fact that any vocabulary and grammar formation is largely dependent and increases the likelihood of learners’ distraction away from the task on the detection of errors or looking up languages in grammatical dictionaries. The basic outline of the task based learning lesson is composed of the pre-task, Task and the language focus and task activities.

The lesson or instructional objectives

These are the specific aims that the teacher has for the indicated lesson and should be achieved at the end of the lesson. These are the objectives drawn from the lesson content and should be achieved as short term objectives. The instructional objectives are useful in providing guidance to the teacher in choosing the content matter to be taught to that group of learners. The instructional objectives also guide the teacher on the appropriate selection of materials and resources to be used during the lesson in order to facilitate the learning in class. Through the analysis of the instructional objectives, the teacher is able to design the appropriate teaching strategies and methods. Having understood the lesson objectives, the teacher is able to design and provide the set standards that can be used in measuring the level of student achievements. The objectives are also significant in providing the teachers with the appropriate feedback about the learner and providing observable behaviors to the learners relating to the topic of study (O'Bannon, 2008).

The pre-task cycle

At this point of the lesson, the teacher presents whatever content is to be expected of the students in the task phase. The teacher primes the students with the key vocabulary and grammatical constructs. The learner becomes responsible for selecting the appropriate language for this learning context themselves. The teacher may at this point present the learners with a model of the task through personal involvement, presenting audio materials, video materials or rather presenting the learners with pictures. At this stage, as a teacher I would provide the learners with basic pictures and audio materials that are present as the available resources for such a learning context (Ellis, 2003).

The task cycle

During this phase, the learners are allowed to perform the real task of the lesson; this may take several forms and structures dependent on the type of task thus ranging from small group works, individuals and even stratified clusters of students. The teacher might not play a role at this phase thus changing to be only a counselor or rather an observer. This a more of student centered methodology and is significant in the second language acquisition since the learners need to be more of involved in the process than the teachers. At this point the students will be involved in recitations and group discussions concerning their second language thus their ability to acquire the second language is boosted. After the learner discussions and problem solving approaches, the learners compile a report which is then presented to the teacher and this gives the tasks they have discussed and the final conclusions that they have reached. The learners therefore present their findings in spoken or written formats (Ellis, 2003).

The language focus stage

This stage the specific features from the task and highlighted and a basis of work is instituted upon them. The feedback concerning the learners’ performance at the reporting stage is also provided at this point. The main advantages of task based learning are that the language is used for genuine purposes indicating that real communications is able to take place. At the time when the learners are reporting their discussions they are forced to consider the general language form rather than the specific nature of other models. The aim of task based model is integrating all the four different learning skills. Since the task based learning model is concerned with reading texts, listening to texts, role plays, use of questionnaires and problem solving it offers a great deal of flexibility thus leading more motivational activities of the learners (Ellis, 2003).

The methodology of learning foreign languages is largely based on the theory stating that it concentrates on simple words with their translations are effective methods of learning and should be reinforced together with relevant together with pictures and pronunciation with maximum avoidance of elements that would distract the process of vocabulary learning such as sentence building at the beginning of the language learning stage. The various task phase methodologies such as the use of group discussions and chart studies are very key in improving the second language acquisition process thus would form a basis of learning through the task based model.

Challenges facing teachers in the planning process

Lack of adequate resources The lack of enough resources is one major challenge that faces the lesson planning process. Planning involves the infusion of various resources and equipment in the lesson content and activities. The available limited resources pose a problem when it comes to their utilization and planning for use. The planning of practicum sessions is restricted in such cases since the resources for such activities are not readily available thus limiting the achievement of such instructional objectives based on learner’s practicality and application.

The reference books and dictionaries are also limited thus making the planning for language studies a nightmare to the teachers.

The resources are not up to date The available resources such as dictionaries and encyclopedia may not be up to date thus unable to provide the current information with the changing technological world. Planning for lessons therefore becomes a very heavy task in that the available data does not really match the standards of study. The teachers are therefore unable to effectively plan and deliver to the learners due to the large information gap existing between the updated and old school books.

Limited time available

There is a major challenge in time that is allocated for each and every unit in the schools. All the units are allocated same duration of time which really does not take into considerations the wider nature of certain unit syllabi which require a lot of time. Practicum lessons which require a lot of time are therefore allocated little time thus a problem with achieving the topic objectives.

Individual differences and exposure

Learners hail from different social, economic and political backgrounds thus planning for learner involving activities is a major problem when it comes to assembling technological resources which might have not been exposed to those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This diverts the attention of the planner to use alternative resources which would not be effective. Learners have individual differences such as health issues, intellectual differences within learning institutions. Learners with disabilities require more time that is dedicated to them which is rarely not provided for by the school curriculum (Wong, 1998).

Insights gained for planning in the future

Acquisition of adequate resources and up to date The subject teachers at various learning institutions should be at a position of making requisitions for the resources that are needed for the learning process. The purchase should be made such that the learners do not really strain for the resources during the lesson hours. The resources being purchased should also conform to the changing structures so that they are up to date and with relevant information to help in the knowledge transfer and reconciliation.

Compressing the syllabus content

Since the time available is inadequate for covering the basic syllabus, the syllabus should be compressed such that only the relevant and crucial content is left for study. The teachers can also overcome this by only planning for the lessons in areas of available resources and for a limited duration of time.

SAMPLE LESSON PLAN

Sub-topic: Instructional Objectives:

Barcroft, J. (2001). Second language vocabulary acquisition:A lexical input processing approach. Foreign Language Annals, 37(2), 323-363. Chenoweth, K. (2009). How it's being done:Urgent lessons from unexpected schools. Cambridge: Havard Education Press. Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: New York:Oxford Applied Linguistics. Mitchell, Diana, & Stephen, T. (1999). Exploring and Teaching the English Language Arts (4th ed.). Boston: MA:Allyn & Bacon. Nation, I. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in another language. cambridge: Cambridge University Press. O'Bannon, B. (2008). What is a Lesson Plan? Tennessee: University of Tennesseee. Wong, H. K. (1998). The first Days of School:How to be an effective Teacher. Mountainview,CA: Harry K. Wong Publications.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1243

This paper is created by writer with

ID 270440701

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Probation argumentative essays, tokyo term papers, igor stravinsky term papers, adam and eve term papers, procrastination term papers, open source software term papers, social engineering term papers, sierra leone term papers, heroism term papers, traffic congestion term papers, david hume term papers, neurology term papers, postmodernism in bloody jack essay examples, persuasive essay sample, free serious games essay example, the travels of a t shirt in the global economy report, free essay on modern masters exhibit, example of obama health care bill essay, the vision of islam by sachiko murata and william c chittick book reviews example, good research paper on wuthering heights, reintegration of prisoners research papers examples, abortion research paper sample, example of research paper on comparison and contrast of architecture flow between united states of america and, good research paper on mechanical engineering major, good example of how do the two acolytes in tanizaki junichirs the two acolytes represent essay, others report, diagram responses and summary term paper samples, good example of essay on a study of the morality of zoos, good example of specialty courts report, good essay about as an alternative to the conventional closed narrative in which loose ends, classical argument essay sample, wikipedia project essays examples, good obesity essay example, appian essays, englewood essays, dutton essays, gigi essays, juvenile offenders essays, progressive movement essays, sex discrimination act essays, gender issues essays, inventory system essays, product strategy essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Oxford Education Blog

The latest news and views on education from oxford university press., why is planning so important for effective teaching.

Professor Chris Kyriacou

I have spent more than 30 years teaching about and doing research on what constitutes ‘effective’ teaching. Over the years I have become more and more convinced that the key to being a successful teacher, both in terms of the quality of learning you promote, and in terms of maintaining your own mental health and enthusiasm for the work you do, is to make sure you devote enough time to planning . Of course, we all know that teaching is a complex activity and involves a wide variety of tasks and qualities, but in my dealings with teachers, ranging from novices to experienced, I still come across many teachers who do not devote enough time to planning and haven’t fully realised the massive benefits that good planning offers, and how it can really help them.

How and why is your teaching effective?

As teachers, we know that teaching is, in essence, about helping pupils to learn. Careful thinking about what it is exactly that you want your pupils to learn, and how best to enable your pupils to achieve this through the learning experiences you provide for them, lies at the heart of the planning process. All successful teachers need to be pupil focused; in other words, you have to think about how the learning activity you have set up will be experienced by each pupil, and how this experience will generate your intended learning outcomes. you’ll find that the planning process forces you to make explicit how and why your teaching will be effective for every one of your pupils.

Golden Time

Lesson plans also provide a huge number of important benefits for you. Firstly, a lesson plan helps provide you with thinking time during the lesson. In particular, it enables you to reflect on how the lesson is going whilst it is in progress, and to think about whether and how small adjustments might need to be made, and time to think about how well each pupil’s learning experience is being optimised. Thinking time during a lesson is like gold-dust – it’s the most valuable commodity that a teacher needs to have and is often in short supply. Good planning means that the many decisions that you need to make during a lesson, have already been thought through before the lesson take place. If you’ve planned the learning, and the logistical arrangements for the lesson in advance then you’ll have more time to get on with the business of assessing pupils’ progress whilst the lesson is going on – and you’ll buy yourself some golden time to deal with the unexpected.

Plans help relieve day to day stress

A second important benefit for you is in terms of stress. For newly qualified teachers, you can go into a lesson confident that you have planned what will be happening, that the materials you need to use have been checked and are to hand, that the correct answers to the questions you pose are readily available to you to refer to, and that the precise qualities and features you expect in a good piece of work will be explicit. The more you can do to build up that confidence at the start if the lesson, based on your planning, the more relaxed you will feel.

Try something new!

Finally, another great benefit of planning is that it enables you to be innovative and try out new approaches and ideas in your teaching. When busy and tired, it’s not surprising that some teachers stick with teaching activities that are tried and tested and which manifestly work successfully. There is nothing wrong with this over the short-term. The time and effort you put into planning your lessons will deliver rich dividends for your pupils in being able to experience lessons that you have homed to perfection. However, time marches on, what and how you teach today will not be what is considered to be good practice in the future. The school curriculum is ever changing (and, of course, the new Ofsted Inspection Framework will be on many teachers’ minds at the moment), be it in terms of the content of the course and lessons, the learning outcomes, the use of technology, the methods of assessment, and working with other staff.

Overhauling your planning can be a daunting challenge if you leave adopting such new approaches for too long. Devoting time to planning has an inbuilt element of reflection involved: how can I improve my teaching? Such reflection can help you stay at the forefront of innovative thinking and practice rather than feeling you are having to catch up with good practice under duress.

Professor Chris Kyriacou is based at the University of York Department of Education, and is the author of “Essential Teaching Skills” , the fifth edition of which was published by Oxford University Press in 2018.

Share this:

- Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- School Counseling

- Military and Veterans Counseling

- Social Justice Dashboard

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Admissions FAQs

- Student Profile

- Counseling Licensure

- Mental Health Counselor Jobs

- School Counselor Jobs

- Online Student Experience

- Student Success

Get a Program Brochure

The importance of lesson planning for student success.

Navigate the educational landscape and unlock the secrets to successful teaching with our blog on lesson planning for student success. Explore its significance to teachers and understand why a lesson plan is important in teaching. This comprehensive guide outlines the importance of lesson planning for teachers and provides valuable insights into creating well-structured plans that resonate with curriculum goals. Immerse yourself in strategic lesson planning for a transformative teaching experience that fosters student success and educator growth.

Lesson Planning Is Essential to Teaching

Any experienced teacher will tell you that lesson planning is a big part of the job. Teachers around the world routinely spend as much as half of their working time on non-teaching activities, and lesson planning accounts for much of that time. 1, 2

Lesson planning is how teachers synthesize the curriculum goals with pedagogy and knowledge of their specific teaching context. 3 Ask ten teachers about the benefits of lesson planning, and you might very well get ten unique answers. There are also different opinions about how far ahead a teacher should plan lessons. Some recommend working a week out, while others advocate planning a month ahead. 4, 5

In the end, though, creating successful learning outcomes for students is the goal. Although well-designed lesson plans take time and thought, it's an investment that can provide returns in many ways. Explore the elements to consider when creating lesson plans and what factors teachers can include in planning to assure success for themselves, their classrooms and, most importantly, their students.

The Many Reasons Why Lesson Planning Is Important

Effective lesson planning contributes to successful learning outcomes for students in several ways. A well-designed lesson plan:

- Helps students and teachers understand the goals of an instructional module

- Allows the teacher to translate the curriculum into learning activities

- Aligns the instructional materials with the assessment

- Aligns the assessment with the learning goal

- Helps assure that the needed instructional materials are available

- Enables the teacher to thoughtfully address individual learning needs among students

Effective lesson planning can also contribute to the teacher’s own success and well-being. Teachers teach because they want to support students, and effective lesson planning can contribute to job satisfaction when a lesson is successful or a student does well on an assessment. Having a skillfully-planned lesson can also make the act of teaching more pleasurable by increasing the teacher’s confidence in themselves and letting them focus more on interaction with the students than on what is supposed to happen next. Importantly, good planning can save time by avoiding last-minute efforts to buy supplies or create materials needed for a day in the classroom. Teachers can use that reclaimed time for themselves or other parts of their lives, increasing work-life balance.

The Importance of Lesson Planning to Effective Curriculum Delivery

“Curriculum” is a word with many meanings, depending on the context. At the most abstract level, curriculum theory addresses such different aspects of teaching as what elements are included in the course of study, along with considerations of how it is taught and tested. See “What Are the 8 Types of Curriculum?” for more on curriculum theory.

Some curricula are more detailed and structured than others. 6 Regardless of the level of detail, the importance of lesson planning is that it bridges the curriculum’s intent with the daily teaching and learning in a classroom. At a minimum, lesson planning adds the element of time, breaking the curriculum into units delivered each session. Usually, though, teachers incorporate their training and knowledge of their students into the task, translating a previously developed curriculum into an action plan for their classroom.

The Importance of Lesson Planning to Student Assessment

The lesson plan translates the curriculum into clear daily goals for student learning that include a description of the objective and a way to measure the student’s attainment of it. 7 A few standard measurement methods are tests, homework assignments and group work. One benefit of the lesson plan is fitting the assessment to the particular goal while accounting for your specific situation. Some educational writers argue that teachers should design the evaluation before designing the learning activities.4 Working outward from the central idea of the learning objective allows teachers flexibility in choosing the type of assessment that will best suit their students and the classroom environment.

Why Lesson Planning Is Important for Classroom Management

Building the lesson plan outward from your learning goals also offers much-needed flexibility in adapting instructional delivery and classroom management during uncertain times. Classes that move from onsite to online or hybrid require different delivery methods, requiring adjustments to existing plans. Such situations highlight the importance of lesson planning in keeping the class moving smoothly from task to task regardless of the learning environment. Advance lesson planning also minimizes the need for discipline and allows you to make the most of your time with students.

Better Lesson Planning Creates More Student Success

Student success and good behavior are more likely when your pupils are actively engaged in classwork. A thoroughly planned lesson facilitates that desirable state by considering unique student educational needs. “All successful teachers need to be pupil-focused; in other words, you have to think about how the learning activity you have set up will be experienced by each pupil, and how this experience will generate your intended learning outcomes.” 8

Better Lesson Planning Is Important for Teacher Success

Teacher success is predicated on student success. Beyond that, the documents you create as part of the planning process are usually part of your evaluation by school administrators. Therefore, having well-prepared and documented plans is an integral part of your success as a teacher. Your lesson plans also become a repository of your growing knowledge as you continue to teach. The importance of lesson planning in furthering your professional growth is undeniable. Cultivating good habits for preparing and reviewing your lesson plans prepares the ground for your success.

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5js64kndz1f3-en.pdf?expires=1642704108&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=793A8F13FA53BD6FF0680CA7F2DDD448

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from businessinsider.com/teachers-time-spent-after-school-work-2019-10#planning-lessons-can-take-several-hours-a-week-4

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from tesol.org/docs/default-source/books/14002_lesson-planning_ch-1

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from edutopia.org/blog/9-ways-plan-transformational-lessons-todd-finley

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, blog.planbook.com/lesson-plan-classroom-management/

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from https://www.edglossary.org/curriculum/

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from edutopia.org/article/how-universal-design-learning-can-help-lesson-planning-year

- Retrieved on January 20, 2022, from educationblog.oup.com/secondary/english/why-is-planning-so-important-for-effective-teaching

Return to Blog

William & Mary has engaged Everspring , a leading provider of education and technology services, to support select aspects of program delivery.

- CRLT Consultation Services

- Consultation

- Midterm Student Feedback

- Classroom Observation

- Teaching Philosophy

- Upcoming Events and Seminars

- CRLT Calendar

- Orientations

- Teaching Academies

- Provost's Seminars

- Past Events

- For Faculty

- For Grad Students & Postdocs

- For Chairs, Deans & Directors

- Customized Workshops & Retreats

- Assessment, Curriculum, & Learning Analytics Services

- CRLT in Engineering

- CRLT Players

- Foundational Course Initiative

- CRLT Grants

- Other U-M Grants

- Provost's Teaching Innovation Prize

- U-M Teaching Awards

- Retired Grants

- Staff Directory

- Faculty Advisory Board

- Annual Report

- Equity-Focused Teaching

- Preparing to Teach

- Teaching Strategies

- Testing and Grading

- Teaching with Technology

- Teaching Philosophy & Statements

- Training GSIs

- Evaluation of Teaching

- Occasional Papers

Strategies for Effective Lesson Planning

Stiliana milkova center for research on learning and teaching.

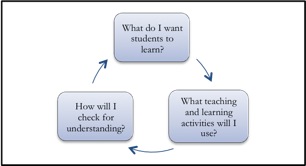

A lesson plan is the instructor’s road map of what students need to learn and how it will be done effectively during the class time. Before you plan your lesson, you will first need to identify the learning objectives for the class meeting. Then, you can design appropriate learning activities and develop strategies to obtain feedback on student learning. A successful lesson plan addresses and integrates these three key components:

- Objectives for student learning

- Teaching/learning activities

- Strategies to check student understanding

Specifying concrete objectives for student learning will help you determine the kinds of teaching and learning activities you will use in class, while those activities will define how you will check whether the learning objectives have been accomplished (see Fig. 1).

Steps for Preparing a Lesson Plan

Below are six steps to guide you when you create your first lesson plans. Each step is accompanied by a set of questions meant to prompt reflection and aid you in designing your teaching and learning activities.

(1) Outline learning objectives

The first step is to determine what you want students to learn and be able to do at the end of class. To help you specify your objectives for student learning, answer the following questions:

- What is the topic of the lesson?

- What do I want students to learn?

- What do I want them to understand and be able to do at the end of class?

- What do I want them to take away from this particular lesson?

Once you outline the learning objectives for the class meeting, rank them in terms of their importance. This step will prepare you for managing class time and accomplishing the more important learning objectives in case you are pressed for time. Consider the following questions:

- What are the most important concepts, ideas, or skills I want students to be able to grasp and apply?

- Why are they important?

- If I ran out of time, which ones could not be omitted?

- And conversely, which ones could I skip if pressed for time?

(2) Develop the introduction

Now that you have your learning objectives in order of their importance, design the specific activities you will use to get students to understand and apply what they have learned. Because you will have a diverse body of students with different academic and personal experiences, they may already be familiar with the topic. That is why you might start with a question or activity to gauge students’ knowledge of the subject or possibly, their preconceived notions about it. For example, you can take a simple poll: “How many of you have heard of X? Raise your hand if you have.” You can also gather background information from your students prior to class by sending students an electronic survey or asking them to write comments on index cards. This additional information can help shape your introduction, learning activities, etc. When you have an idea of the students’ familiarity with the topic, you will also have a sense of what to focus on.

Develop a creative introduction to the topic to stimulate interest and encourage thinking. You can use a variety of approaches to engage students (e.g., personal anecdote, historical event, thought-provoking dilemma, real-world example, short video clip, practical application, probing question, etc.). Consider the following questions when planning your introduction:

- How will I check whether students know anything about the topic or have any preconceived notions about it?

- What are some commonly held ideas (or possibly misconceptions) about this topic that students might be familiar with or might espouse?

- What will I do to introduce the topic?

(3) Plan the specific learning activities (the main body of the lesson)

Prepare several different ways of explaining the material (real-life examples, analogies, visuals, etc.) to catch the attention of more students and appeal to different learning styles. As you plan your examples and activities, estimate how much time you will spend on each. Build in time for extended explanation or discussion, but also be prepared to move on quickly to different applications or problems, and to identify strategies that check for understanding. These questions would help you design the learning activities you will use:

- What will I do to explain the topic?

- What will I do to illustrate the topic in a different way?

- How can I engage students in the topic?

- What are some relevant real-life examples, analogies, or situations that can help students understand the topic?

- What will students need to do to help them understand the topic better?

(4) Plan to check for understanding

Now that you have explained the topic and illustrated it with different examples, you need to check for student understanding – how will you know that students are learning? Think about specific questions you can ask students in order to check for understanding, write them down, and then paraphrase them so that you are prepared to ask the questions in different ways. Try to predict the answers your questions will generate. Decide on whether you want students to respond orally or in writing. You can look at Strategies to Extend Student Thinking , http://www.crlt.umich.edu/gsis/P4_4.php to help you generate some ideas and you can also ask yourself these questions:

- What questions will I ask students to check for understanding?

- What will I have students do to demonstrate that they are following?

- Going back to my list of learning objectives, what activity can I have students do to check whether each of those has been accomplished?

An important strategy that will also help you with time management is to anticipate students’ questions. When planning your lesson, decide what kinds of questions will be productive for discussion and what questions might sidetrack the class. Think about and decide on the balance between covering content (accomplishing your learning objectives) and ensuring that students understand.

(5) Develop a conclusion and a preview

Go over the material covered in class by summarizing the main points of the lesson. You can do this in a number of ways: you can state the main points yourself (“Today we talked about…”), you can ask a student to help you summarize them, or you can even ask all students to write down on a piece of paper what they think were the main points of the lesson. You can review the students’ answers to gauge their understanding of the topic and then explain anything unclear the following class. Conclude the lesson not only by summarizing the main points, but also by previewing the next lesson. How does the topic relate to the one that’s coming? This preview will spur students’ interest and help them connect the different ideas within a larger context.

(6) Create a realistic timeline

GSIs know how easy it is to run out of time and not cover all of the many points they had planned to cover. A list of ten learning objectives is not realistic, so narrow down your list to the two or three key concepts, ideas, or skills you want students to learn. Instructors also agree that they often need to adjust their lesson plan during class depending on what the students need. Your list of prioritized learning objectives will help you make decisions on the spot and adjust your lesson plan as needed. Having additional examples or alternative activities will also allow you to be flexible. A realistic timeline will reflect your flexibility and readiness to adapt to the specific classroom environment. Here are some strategies for creating a realistic timeline:

- Estimate how much time each of the activities will take, then plan some extra time for each

- When you prepare your lesson plan, next to each activity indicate how much time you expect it will take

- Plan a few minutes at the end of class to answer any remaining questions and to sum up key points

- Plan an extra activity or discussion question in case you have time left

- Be flexible – be ready to adjust your lesson plan to students’ needs and focus on what seems to be more productive rather than sticking to your original plan

Presenting the Lesson Plan

Letting your students know what they will be learning and doing in class will help keep them more engaged and on track. You can share your lesson plan by writing a brief agenda on the board or telling students explicitly what they will be learning and doing in class. You can outline on the board or on a handout the learning objectives for the class. Providing a meaningful organization of the class time can help students not only remember better, but also follow your presentation and understand the rationale behind in-class activities. Having a clearly visible agenda (e.g., on the board) will also help you and students stay on track.

Reflecting on Your Lesson Plan

A lesson plan may not work as well as you had expected due to a number of extraneous circumstances. You should not get discouraged – it happens to even the most experienced teachers! Take a few minutes after each class to reflect on what worked well and why, and what you could have done differently. Identifying successful and less successful organization of class time and activities would make it easier to adjust to the contingencies of the classroom. For additional feedback on planning and managing class time, you can use the following resources: student feedback, peer observation, viewing a videotape of your teaching, and consultation with a staff member at CRLT (see also, Improving Your Teaching: Obtaining Feedback , http://www.crlt.umich.edu/gsis/P9_1.php and Early Feedback Form , http://www.crlt.umich.edu/gsis/earlyfeedback.pdf).

To be effective, the lesson plan does not have to be an exhaustive document that describes each and every possible classroom scenario. Nor does it have to anticipate each and every student’s response or question. Instead, it should provide you with a general outline of your teaching goals, learning objectives, and means to accomplish them. It is a reminder of what you want to do and how you want to do it. A productive lesson is not one in which everything goes exactly as planned, but one in which both students and instructors learn from each other.

Additional Resources

Video clips of GSIs at the University of Michigan actively engaging students in a practice teaching session: https://crlte.engin.umich.edu/engineering-gsi-videos/

Plan the First Day's Session: How to create to a lesson plan for the first day of class: http://gsi.berkeley.edu/gsi-guide-contents/pre-semester-intro/first-day-plan/

Fink, D. L. (2005). Integrated course design. Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center. Retrieved from https://www.ideaedu.org/idea_papers/integrated-course-design/

back to top

Contact CRLT

location_on University of Michigan 1071 Palmer Commons 100 Washtenaw Ave. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2218

phone Phone: (734) 764-0505

description Fax: (734) 647-3600

email Email: [email protected]

Connect with CRLT

directions Directions to CRLT

group Staff Directory

markunread_mailbox Subscribe to our Blog

Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

What Makes a Great Lesson Plan?

by Liz Beck | Aug 11, 2021 | Lesson Plans & Planning

In our last article, we explored who a lesson plan is for . Now it’s time to look at what makes a lesson plan well worth all the time and energy it takes to create one that really makes a difference in the classroom.

There are plenty of lesson planning templates out there. If you’re a teacher, we’re willing to bet you’re actually currently required to use a template, and there’s also a chance that you might hate it (can you tell that we hear this a lot?).

So here’s the thing: there is no Great Lesson Plan Template. There are some good ones, but, like we said before, it’s not about the document; it’s about the plan (which might be mostly in your head, or mostly in the Notes app on your iPhone, or mostly on a post-it note crammed at the bottom of your bag).

Madeline Hunter offers a good beginning for lesson planning

Like just about every educational researcher on the planet, I’m a big fan of Madeline Hunter. She formalized the basic concept of a lesson plan in the mid-20th century, and she’s still right. A good lesson plan follows her model : start with an anticipatory set, move to direct teaching/modeling, have the kids do some guided practice, and then check for student understanding.

But, to me, these terms have always felt a bit inaccessible.

Bringing more clarity to the idea of lesson planning

In our post, the Top 6 Myths About Lesson Plans , we defined a good lesson plan like this:

“…a good lesson plan—at the very least—ensures that all of the students learned something worth learning, and their teacher knows for certain that every one of them learned it.”

This definition may be more accessible, but it’s still a bit vague. So let’s unpack it a little bit more:

A great lesson plan is a framework for

- what your students will learn

- how your students will learn it

- how students will know they learned it

- how the teacher will know the students learned it

If you’ve been in a situation where your kids weren’t fully engaged, or they didn’t learn all of the things you wanted them to learn, we have some thoughts about how a better lesson plan might help.

How to know if you have a great lesson plan

A great lesson plan is a sketch for how you’re going to make sure every student in your class engages with the material and grows in their understanding of it during your class period.

At the end of a truly great lesson, you know (for certain!) the following:

- Every student in your class engaged with the material

- Every student in your class moved forward in their understanding and/or development of skills

- Every student in your class knows what they learned, why they learned it, and what their next steps are

If you don’t know these things at the end of the class period, then you didn’t have a great lesson.

Are your students actually engaging?

A great lesson is engaging.

We know the word “engaging” gets tossed around a lot, but it is a crucial aspect of powerful teaching and learning. (Have you ever left a PD session or completely zoned out of it because it was so boring? We have.) With most content, engagement doesn’t happen naturally.

Here’s an example: Let’s say you need your students to learn about the water cycle. They could read about it, but how do you know they learned anything from reading it? Or, honestly, how do you even know for sure that they actually even read it at all? Couldn’t the kids have just stared silently at the book, occasionally turning the pages?

Your students could watch a video about the water cycle, but you’re up against the same conundrum as reading. They may be totally zoning out (spoiler alert: most of them are totally zoning out).

Or maybe they’re going to listen to you tell them about the water cycle. Are you sure they absorbed what you said? Did they take notes? If they took notes, will they actually remember what they wrote down? Will they truly internalize it? Will they be able to explain the water cycle in 5 years? Does it even matter if they remember it? Why?

A caveat about engagement

One of the tricky things is ensuring that you don’t go too far down the spectrum of pure engagement. For example, trying to see who can build the tallest tower out of paper and tape is super engaging. But, there are few scenarios where building that tower leads to any connections to standards. On the other end of the spectrum, watching a teacher give a PowerPoint presentation while you take guided notes is (unless your teacher is a TEDTalk-level speaker), pretty seriously disengaging. Striking the right balance of engagement and actual learning is quite a task, but it’s not insurmountable.

Easy tips for great lesson plans that engage students in powerful learning

So, how do you engage students in powerful learning? You need tools. Lots of them. We recommend getting started with Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion , and a good handful of tech tools . You need to be able to say, “Okay, my kids need to learn how to do _____; what are at least 5 ways I could help them learn that?”

1. Getting every student engaged

Cold-calling: Stop asking kids to raise their hands. Instead, start randomly calling on kids. Yes, this is awkward and uncomfortable. Keep a cup full of popsicle sticks with your students’ names on them if you can’t keep track.

Read, write, think, talk lesson plans: Create lessons that incorporate these four actions and you’ll guarantee some serious engagement.

Movement: Find ways to incorporate movement every 20 minutes or so. Bonus points if you can utilize activities that incorporate movement and content into the same activity (teaching vocabulary terms with movements is a great way to practice this).

2. Making sure you and your students know what they learned

Conferences : Have an individual conversation with every student every week (it’s not that hard, seriously. Set a timer for 1-minute per student if you’re stressed about time, and see if it isn’t a total game-changer for your relationships and behavior)

Exit tickets: Have kids write down what they learned at the end of each class period.

Portfolios: Have students create and maintain a portfolio showcasing their best work and their reflections on why they think it’s so exceptional. Kids can even do this through creating their own websites at free places like Wix and Weebly. The best thing about portfolios is that they require virtually zero effort on the part of the teacher.

3. Making sure you know what you want your students to learn

Questioning: Plan out all of the questions you would want to ask students about the material (that way you don’t end up throwing out tons of easy questions to your kids). Check out these question stems to get started.

“I Can” statements: Reframe your standards into “I Can” statements, and discuss these with your kids.

The 2 Question Test from Wiggins and McTighe: This is one of our favorite tools, and it will help you figure out whether your assessments, products and projects align to what you actually need students to know.

Interested in getting more training for yourself or your school?

If you’re interested in any of the ideas above, but don’t quite know how you might get started, that’s okay! We’re here to help.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive toolkits, interviews, coaching tips, project-based learning ideas and more!

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Planning a Class

If you've ever given a formal presentation on a topic, you've probably done some kind of planning. You may have considered who your audience was and gathered information to meet their needs and interests. Or, you may have considered your own objective and worked to meet this goal. Either way, you probably spent more time gathering and arranging information than you did actually presenting it. Your confidence and ability to present may have also depended on the plan you created.

Planning a class presents similar challenges. Sure, we've all known the instructor who can "wing-it" and still amaze us with their infinite wit and wisdom. But many of us feel that we are not that instructor. In fact, some readers of this guide may be teaching a writing course for the first time. If so, you're probably beginning to realize that planning can be the most challenging part of teaching.

This guide will help you construct successful lesson plans. First, we'll review some effective strategies and techniques. Since there are many factors to consider when planning a class, this chapter is broken down into six different sections. If you are reading this for the first time, is useful to look at all six sections, as each one builds off the one before. In the future, you may decide to only reference the section that serves your immediate purposes.

Guidelines for planning an effective class are:

Using Goals to Shape a Lesson

Planning transitions, planning introductions, planning conclusions, planning classroom discussions.

- Creating Write to Learn Activities

Planning Group Activities

Reflecting on lessons.

- Citation Information

How This Guide Can Help

Begin planning a lesson by considering your goals. In addition to keeping in mind the overall goals for the course, consider the specific goals for that lesson. Ask yourself what you want your students to gain most from the lesson. Often, you'll come up with a list of two or three goals for the class. A successful lesson will combine various goals into a cohesive plan.

Let's say the goals in the syllabus for one class include Discussing and Practicing Critical Reading and Exploring How Purpose, Audience , and Context Influence a Writer's Choices . Lately, however, you've noticed small puddles of drool on your students' desks, a sure sign that they aren't fully involved in class. To help your students become more engaged during class, you create a third goal: Facilitating More Meaningful Discussions . The three goals for this lesson:

- Discussing and Practicing Critical Reading

- Exploring How Purpose, Audience, and Context Influence a Writer's Choices

- Facilitating More Meaningful Discussions

Reflect on your goals for the lesson, then prioritize them. Ask yourself what students most need to gain from the lesson. As you prioritize your goals, reflect once again on the overall goals for the course. Consider, as well, the goals for the current assignment.

If, Practicing Critical Reading is the most important goal for the day, focus your activities to meet this goal. Remember, however that Practicing Critical Reading is not your only goal for the class. Try to imagine how all three of the goals you've defined for the class can translate into activities that feed into each other.

Creating Activities that Reflect Goals

Consider the following example. Over the past few days, you and your students have discussed purpose, audience, and focus. To build on these discussions, use them as a starting point. Spend ten minutes at the beginning of class analyzing the context for the essay you're working with. This will help you pursue your goal of Exploring How Purpose, Audience, and Context Influence a Writer's Choices. After you've analyzed the essay's context, meet your goal of Facilitating More Meaningful Discussions by asking students to briefly share their personal reactions to the main ideas in the text. For the remainder of class, engage your students in a critical reading of the essay and an in-depth discussion of its argument and ideas. Since Practicing Critical Reading is the most important goal for the day, the majority of class time will be spent meeting this goal.

A loose outline of goals and activities might look like this:

- Goal: Exploring How Purpose, Audience, and Context Influence a Writer's Choices Activity: Analyze the context of a text (10 minutes)

- Goal: Facilitating More Meaningful Discussions Activity: Discuss students' reactions to a text (10 minutes)

- Goal: Practicing Critical Reading Activity: Practice critical reading of a text (30 minutes)

Typically, you'll plan more than one activity per class, so creating transitions between those activities is crucial. Students need to know when you're changing the focus of the class. When writing transitions, ask yourself, what is the significance of each of these activities? How do they connect to the daily goals? Why did I arrange them in this order? Is there a more logical way to organize these procedures?

Be sure to write out transition statements in your lesson plans so you don't find yourself grappling for explanations on the spot. If you can't explain the significance of an activity, look back at the unit assignment sheet or the description of goals in your syllabus. If the relevance of an activity is still unclear, replace it with something different to satisfy the same goal.

Strategies for Creating Effective Transitions

Highlight an activity's importance.

To help students understand where they are going, use transitions to explain the goal for an activity and why it is important.

For example: "In this second unit, you'll be concentrating on how cultural contexts shape texts. What influences a writer's perspective on an issue? Why does the writer approach this issue from a particular angle? Investigating the writer's context is important because it will help you read and think critically (two skills you'll develop this semester). Let's practice some critical reading by analyzing the context for the essay you've just read. I'd like you to break into five groups..."

Emphasize the Relationships Among Activities

Think of activities as building blocks, carefully arranged to lead students to a predetermined destination. If you want students to write from a rhetorical approach, consider the steps they have to take and plan accordingly. Then, explain to students how one activity leads to another.

For example: "Now that we've talked a bit about purpose, context, and audience in the writing process, let's identify these three concerns in the first essay assignment."

Emphasize Connections between Activities and Students' Own Writing

Students are more likely to participate when they see how activities relate to their own writing. For this reason, explain to students how an activity will help them become better writers for the next assignment.

For example: "To write effectively, we have to consider the context of our audience. This will help focus our writing so that it speaks to someone with different expectations. Since the context for essay three is not a familiar academic situation, you'll need to analyze your context and audience before constructing your argument. This next activity is aimed at helping you think more about the context for which we'll be writing."

Sample Outline of Lesson Plan with Transitions

The three goals for this lesson:

Activities and Transitions:

Transition: Now that we understand the context for this essay, let's think about it in the context of our classroom. We are not the audience this writer had in mind, so our reactions may be different. What were some of your reactions to the ideas in this essay?

Transition: It's useful to react informally to the ideas in a text but when you write a response for an academic audience, you'll need to show that you've read the text critically first before sharing your views. So let's practice critical reading for the last thirty minutes of class.

- Practice critical reading of a text (30 minutes)

Now that you have a loose outline of your lesson, think about how you'll introduce it. Introductions are important because, like transitions, they guide students' understanding of the course and its goals. When you provide an introduction, students see that you have a sense of where the lesson is headed. Not only will this add to your credibility, but students will be less inclined to ask, "Why do we have to do this?"

Use introductions to connect concepts from earlier classes to the upcoming lesson. Also use them as checkpoints or reminders for yourself and your students - this is where we've been and this is where we're going.

When writing introductions, look back at the previous lesson and tie up any loose ends. Perhaps students were walking out the door when you explained the connection between an activity and an upcoming essay assignment. Introductions are ideal times to reinforce important concepts.

Your introduction should include an outline of daily activities; but it is equally important to explain the purpose of these activities. Why do students need to practice critical reading in a writing class? How will their writing benefit from learning to analyze the rhetorical context surrounding a text? Without explanations, students wonder if their time would be better spent at home eating cheese puffs.

Methods for introducing class:

- Write an outline on the board, "What we'll do today" to provide a clear focus and keep the class on track.

- List activities on an overhead and uncover them as you address each one.

- Have students summarize what you did last class and how it connects to the upcoming essay. Then, explain how the next lesson will build on that.

Sample Outline of Lesson Plan with Transitions and Introduction

Introduction: Last time we discussed the ways context influences the choices a writer makes. Today we'll keep that in mind as we analyze the context for the essay you just read. Since our context is different from the one the writer intended, we'll spend a few minutes discussing your responses to the essay. Then, we'll focus on critical reading because this will help you accurately represent an author's ideas in the summary part of your essay. It will prepare you for the analytical writing we do in units two and three and it will also assist you in gaining the most from texts encountered beyond COCC150.

Effective transitions and introductions guide students' understanding of how activities, discussions and assignments relate to their own writing. Still, some students won't make these connections until they've engaged in class activities. Conclusions reinforce important connections and help students anticipate the goals for the next class.

Methods for concluding class:

- Summarize the information just covered in the class in your own words. Explain how the lesson builds on previous lessons and connects to the upcoming assignment.

- Have students conclude by summarizing or interpreting the significance of the lesson. What did they learn? How will it relate to their assignment?

- Ask students to do a brief "Write To Learn" activity reflecting on one thing they can take from today's class and apply to their writing.

Sample Outline of Lesson Plan with Transitions, Introduction, and a Conclusion

Transition: It's useful to react informally to the ideas in a text but when you write a response for an academic audience, you'll need to show that you've read the text critically first before sharing your views. So, let's practice critical reading for the last thirty minutes of class.

Conclusion: Today we reviewed the ways context influences the choices a writer makes. We also shared some of our responses to the essay and practiced critical reading strategies to help you write an accurate summary for essay one. Next time we'll focus on writing a response and consider the choices you'll have to make when drafting your own writing.

Instructors like to believe that if students are awake and engaged in conversation it's a cause for celebration. But there's more to consider. You may witness a spectacular discussion on the effects of teen magazines on youth culture or the implications of cyborgs in science fiction novels, but at some point you need to ask, "How do these discussions help students become better writers?"

When planning a discussion, consider your daily goals. Ask yourself, what do I want students to gain from this discussion? How will it contribute to the overall goal for the lesson? How does it connect to students' own writing?

Shape your outline or discussion plan to reflect the daily goals.

Discussions happen for different reasons. Perhaps you're leading a discussion to introduce a new concept or assignment. Maybe you're critiquing a sample essay, or looking closely at an assigned reading. Whatever the situation, you'll want to consider your role, as well as the goals. Taken together, these provide a starting point to give shape to your classroom discussions.

Planning to Introduce a New Concept or Assignment

When you are explaining what is meant by context, audience, or purpose ; or you are describing the writing situation for an essay, it is useful to engage students by asking questions that encourage them to reflect on their own knowledge. For example, when introducing audience as a rhetorical concept, you might ask, "Who did you think of as your audience when you completed your assignment for today? How did you make choices based on that audience?"

At some point though, students will begin to ask specific questions. This is an excellent time to define the concept you're introducing and provide them with clear answers.

Suggestions for Planning to Teach a New Concept

When planning to teach a new concept, write detailed notes in your lesson plans to help guide the discussion. Also, have several examples ready in case you need to present your points differently. After you explain a concept, plan to have students apply it to their own thinking or writing. Prepare questions or activities to gauge students' understanding and consider assigning additional reading to reinforce the lesson.

Suggestions for Introducing a New Assignment

When introducing a new assignment, be sure you've carefully reviewed it yourself beforehand. Highlight key places where you'll want to elaborate with examples or explanation. Also, anticipate any questions or confusions students may have.

Plan to check for understanding by asking students to summarize or interpret certain aspects of the assignment. For example, have them analyze the writing situation by asking, "How does this compare to the essay you just finished? Who is your new audience? How will you need to shape your writing to meet the needs of this audience?"

If a student raises a question about a concept or an assignment that you don't have an answer for, simply tell them you'll get back to them next class.

Planning to Model or Critique Student Samples