What is the Critical Thinking Test?

Critical thinking practice test, take a free practice critical thinking test, practice critical thinking test.

Updated November 16, 2023

The Critical Thinking Test is a comprehensive evaluation designed to assess individuals' cognitive capacities and analytical prowess.

This formal examination, often referred to as the critical thinking assessment, is a benchmark for those aiming to demonstrate their proficiency in discernment and problem-solving.

In addition, this evaluative tool meticulously gauges a range of skills, including logical reasoning, analytical thinking, and the ability to evaluate and synthesize information.

This article will embark on an exploration of the Critical Thinking Test, elucidating its intricacies and elucidating its paramount importance. We will dissect the essential skills it measures and clarify its significance in gauging one's intellectual aptitude.

We will examine examples of critical thinking questions, illuminating the challenging scenarios that candidates encounter prompting them to navigate the complexities of thought with finesse.

Before going ahead to take the critical thinking test, let's delve into the realm of preparation. This segment serves as a crucible for honing the skills assessed in the actual examination, offering candidates a chance to refine their analytical blades before facing the real challenge. Here are some skills that will help you with the critical thinking assessment: Logical Reasoning: The practice test meticulously evaluates your ability to deduce conclusions from given information, assess the validity of arguments, and recognize patterns in logic. Analytical Thinking: Prepare to dissect complex scenarios, identify key components, and synthesize information to draw insightful conclusions—a fundamental aspect of the critical thinking assessment. Problem-Solving Proficiency: Navigate through intricate problems that mirror real-world challenges, honing your capacity to approach issues systematically and derive effective solutions. What to Expect: The Critical Thinking Practice Test is crafted to mirror the format and complexity of the actual examination. Expect a series of scenarios, each accompanied by a set of questions that demand thoughtful analysis and logical deduction. These scenarios span diverse fields, from business and science to everyday scenarios, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of your critical thinking skills. Examples of Critical Thinking Questions Scenario: In a business context, analyze the potential impacts of a proposed strategy on both short-term profitability and long-term sustainability. Question: What factors would you consider in determining the viability of the proposed strategy, and how might it affect the company's overall success? Scenario: Evaluate conflicting scientific studies on a pressing environmental issue.

Question: Identify the key methodologies and data points in each study. How would you reconcile the disparities to form an informed, unbiased conclusion?

Why Practice Matters

Engaging in the Critical Thinking Practice Test familiarizes you with the test format and cultivates a mindset geared towards agile and astute reasoning. This preparatory phase allows you to refine your cognitive toolkit, ensuring you approach the assessment with confidence and finesse.

We'll navigate through specific examples as we proceed, offering insights into effective strategies for tackling critical thinking questions. Prepare to embark on a journey of intellectual sharpening, where each practice question refines your analytical prowess for the challenges ahead.

This is a practice critical thinking test.

The test consists of three questions .

After you have answered all the questions, you will be shown the correct answers and given full explanations.

Make sure you read and fully understand each question before answering. Work quickly, but don't rush. You cannot afford to make mistakes on a real test .

If you get a question wrong, make sure you find out why and learn how to answer this type of question in the future.

Six friends are seated in a restaurant across a rectangular table. There are three chairs on each side. Adam and Dorky do not have anyone sitting to their right and Clyde and Benjamin do not have anyone sitting to their left. Adam and Benjamin are not sitting on the same side of the table.

If Ethan is not sitting next to Dorky, who is seated immediately to the left of Felix?

You might also be interested in these other PRT articles:

Recruiting?

- Search for:

- Verbal Aptitude Tests

- Numerical Aptitude Test

- Non-verbal Aptitude Test

- Mechanical Aptitude Tests

- Tests by Publisher

- Personality Test

- Prep Access

- Articles & News

A Critical Thinking test, also known as a critical reasoning test, determines your ability to reason through an argument logically and make an objective decision. You may be required to assess a situation, recognize assumptions being made, create hypotheses, and evaluate arguments.

What questions can I expect?

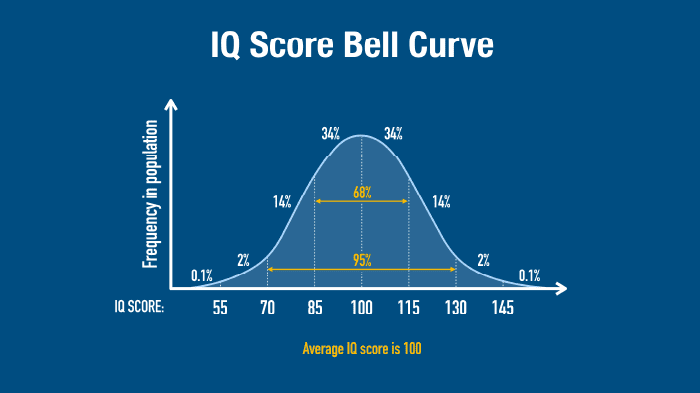

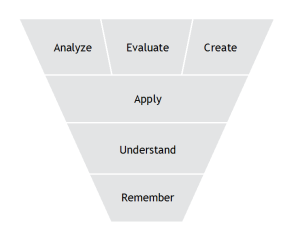

Questions are likely based on the Watson and Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal model, which contains five sections designed to assess how well an individual reasons analytically and logically. The five sections are:

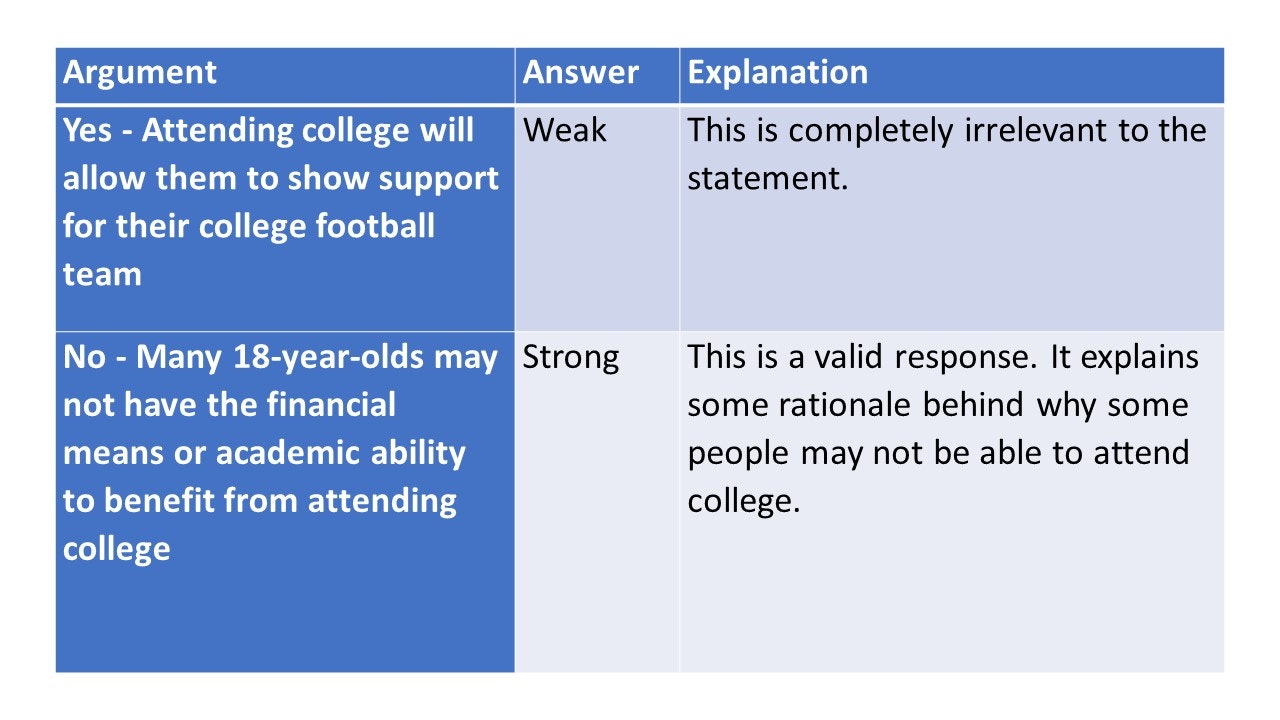

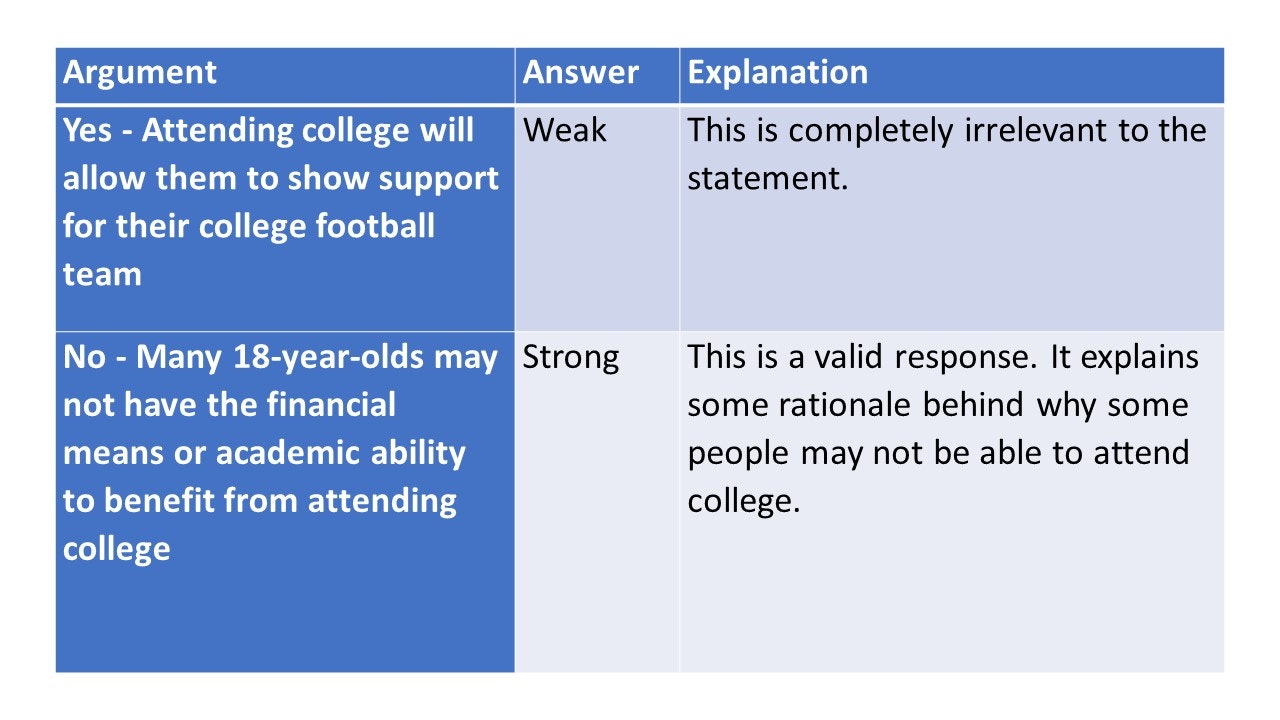

Arguments : In this section, you are tested on your ability to distinguish between strong and weak arguments. For an argument to be strong, it must be both significant and directly related to the question. An argument is considered weak if it is not directly related to the question, of minor importance, or confuses correlation with causation, which is the incorrect assumption that correlation implies causation.

Assumptions : An assumption is something taken for granted. People often make assumptions that may not be correct. Being able to identify these is a key aspect of critical reasoning. A typical assumption question will present a statement and several assumptions, and you are required to identify whether an assumption has been made.

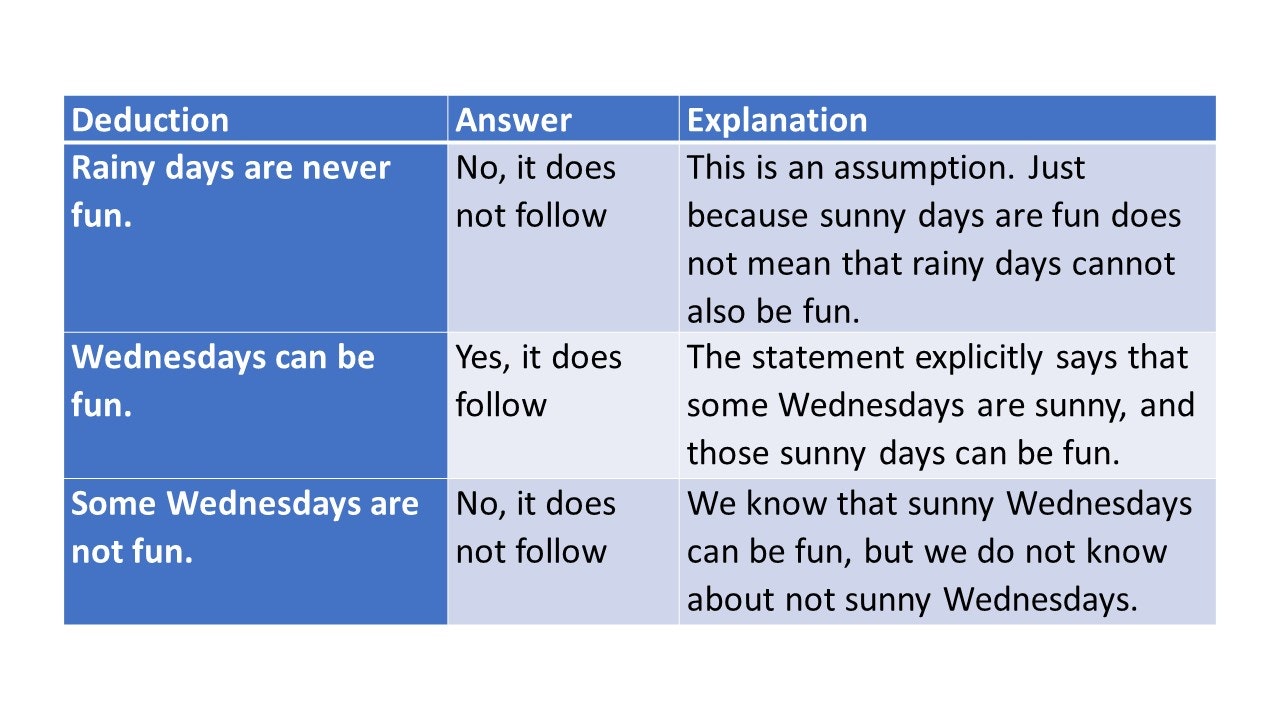

Deductions : Deduction questions require you to draw conclusions based solely on the information provided in the question, disregarding your own knowledge. You will be given a passage of information and must evaluate whether a conclusion made from that passage is valid.

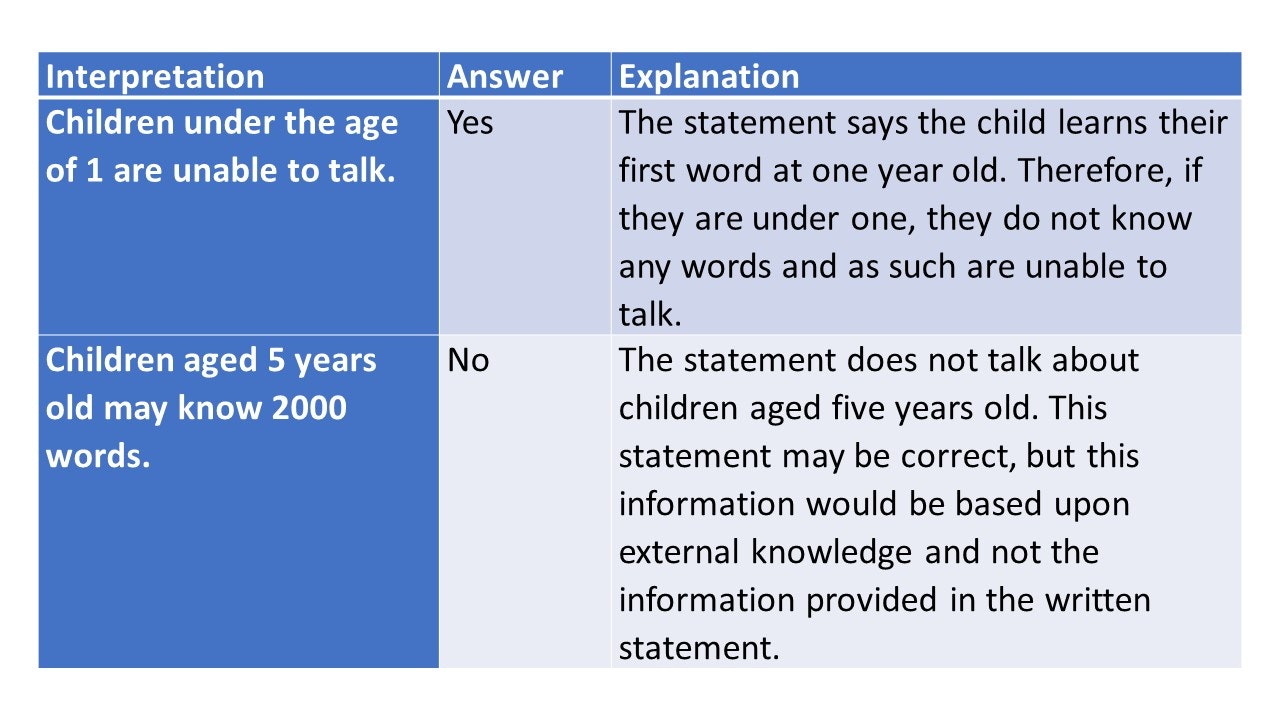

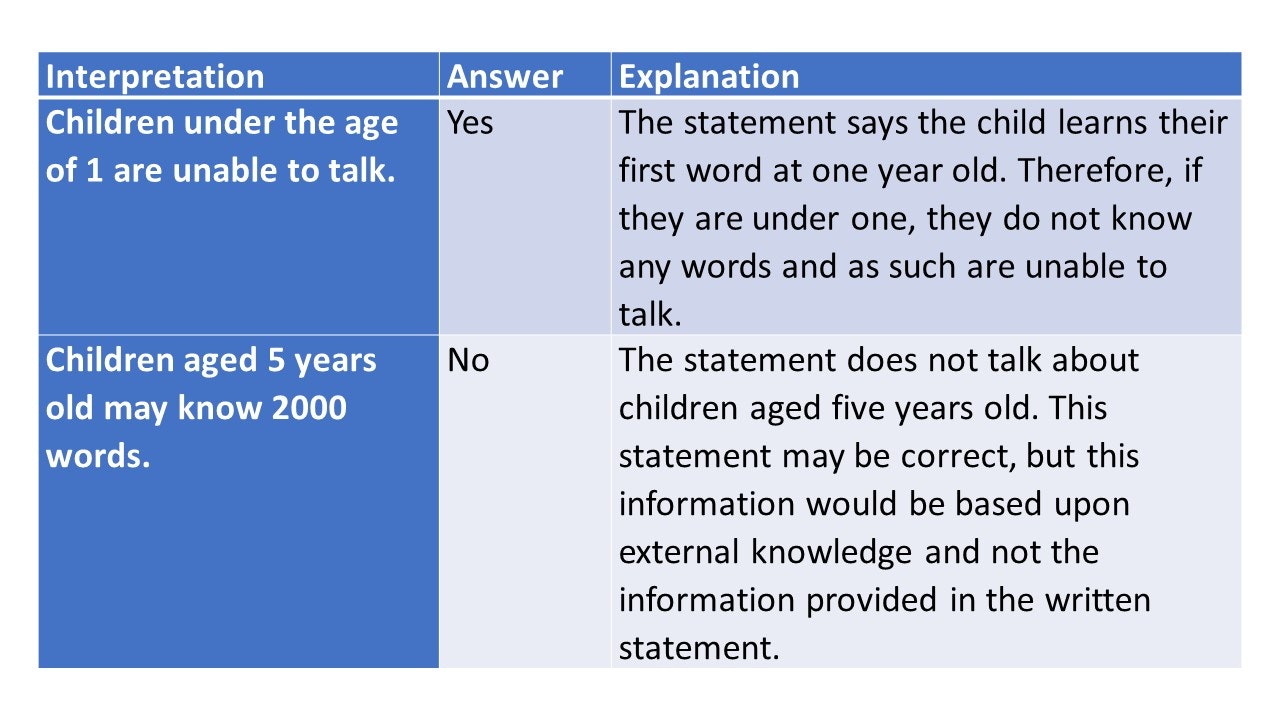

Interpretation : In these questions, you are given a passage of information followed by a proposed conclusion. You must consider the information as true and decide whether the proposed conclusion logically and undoubtedly follows.

Inferences : Inference involves drawing conclusions from observed or supposed facts. It is about deducing information that is not explicitly stated but implied by the given information. For example, if we find a public restroom door locked, we infer that it is occupied.

Critical Thinking example:

Read the following statement and decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the information given.

Statement: Every librarian at the city library has completed a master’s degree in Library Science. Sarah is a librarian at the city library.

Conclusion: Sarah has completed a master’s degree in Library Science.

Does this conclusion logically follow from the statement?

Answer Options:

Explanation: Select your answer to display explanation.

The statement establishes that every librarian at the city library has completed a master’s degree in Library Science. Since Sarah is identified as a librarian at this library, it logically follows that she has completed a master’s degree in Library Science. The conclusion is a direct inference from the given information.

Where are Critical thinking tests used?

Critical thinking tests are commonly used in educational institutions for admissions and assessments, particularly in courses requiring strong analytical skills. In the professional realm, they are a key component of the recruitment process for roles demanding problem-solving and decision-making abilities, and are also utilized in internal promotions and leadership development. Additionally, these tests are integral to professional licensing and certification in fields like law and medicine, and are employed in training and development programs across various industries.

Practice Critical Thinking Test

Try a free critical thinking test. This free practice test contains 10 test questions and has a time limit of 6 minutes.

Verbal Test Prep

Verbal Test Preparation Package includes all nine verbal question categories, including:

- Critical Thinking

- Deductive Reasoning

- Verbal Reasoning

- Word Analogy

6 months access

What you get

- 1000+ verbal practice questions

- Clearly Explained Solutions

- Test statistics

- Score progression charts

- Compare your performance

- Vocabulary Trainer

- Friendly customer service

- 24/7 access on all devices

Discover how to make smart hiring decisions.

Unlock Your Potential

Improve your performance with our test preparation platform.

- Access 24/7 from all your devices .

- More than 1000 verbal practice questions.

- Solutions explained in detail.

- Keep track of your performance with charts and statistics.

- Reference scores to compare your performance against others

- Vocabulary Trainer.

- Friendly customer service.

Simplify Your Study Maximize Your Score

Get instant access to our test prep platform.

Username or email address * Required

Password * Required

Remember me Log in

Lost your password?

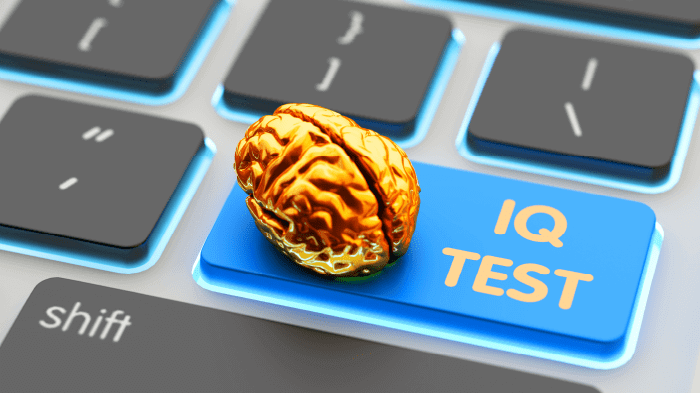

What Is the Watson Glaser Test?

Who uses the watson glaser test and why, why is it so important to be a critical thinker, what is the watson glaser red model, how to pass a watson glaser test in 2024, how to prepare for a watson glaser critical appraisal in 2024, frequently asked questions, the watson glaser critical thinking appraisal.

Updated May 10, 2024

Modern employers have changed the way that they recruit new candidates. They are no longer looking for people who have the technical skills on paper that match the job description.

Instead, they are looking for candidates who can demonstrably prove that they have a wider range of transferrable skills.

One of those key skills is the ability to think critically .

Firms (particularly those in sectors such as law, finance, HR and marketing ) need to know that their employees can look beyond the surface of the information presented to them.

They want confidence that their staff members can understand, analyze and evaluate situations or work-related tasks. There is more on the importance of critical thinking later in this article.

This is where the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking test comes into play.

The Watson Glaser critical thinking test is a unique assessment that provides a detailed analysis of a participant’s ability to think critically.

The test lasts 30 minutes and applicants can expect to be tested on around 40 questions in five distinct areas :

Assumptions

Interpretation.

The questions are multiple-choice and may be phrased as true/false statements in a bid to see how well the participant has understood and interpreted the information provided.

Employers around the world use it during recruitment campaigns to help hiring managers effectively filter their prospective candidates .

The Watson Glaser test has been used for more than 85 years; employers trust the insights that the test can provide.

In today’s competitive jobs market where every candidate has brought the best of themselves, it can be increasingly difficult for employers to decide between applicants.

On paper, two candidates may appear identical, with a similar level of education, work experience, and even interests and skills.

But that does not necessarily mean both or either of them is right for the job.

There is much information available on creating an effective cover letter and resume, not to mention advice on making a good impression during an interview.

As a result, employers are increasingly turning to psychometric testing to look beyond the information that they have.

They want to find the right fit: someone who has the skills that they need now and in the future. And with recruitment costs rising each year, making the wrong hiring decision can be catastrophic.

This is where the Watson Glaser test can help.

It can provide hiring managers with the additional support and guidance they need to help them make an informed decision.

The Watson Glaser test is popular among firms working in professional services (such as law, banking and insurance) . It is used for recruitment for junior and senior positions and some of the world’s most recognized establishments are known for their use of the test.

The Bank of England, Deloitte, Hiscox, Linklaters and Hogan Lovells are just a few employers who enhance their recruitment processes through Watson Glaser testing.

Critical thinking is all about logic and rational thought. Finding out someone’s critical thinking skill level is about knowing whether they can assess whether they are being told the truth and how they can use inferences and assumptions to aid their decision-making.

If you are working in a high-pressure environment, having an instinctive ability to look beyond the information provided to the underlying patterns of cause-and-effect can be crucial to do your job well.

Although it is often thought of concerning law firms and finance teams, it is easy to see how critical thinking skills could be applied to a wide range of professions.

For example, HR professionals dealing with internal disputes may need to think critically. Or social workers and other health professionals may need to use critical thinking to assess whether someone is vulnerable and in need of help and support when that person does not or cannot say openly.

Practice Watson Glaser Test with TestHQ

Critical thinking is about questioning what you already know . It is about understanding how to find the facts and the truth about a situation or argument without being influenced by other people’s opinions .

It is also about looking at the bigger picture and seeing how decisions made now may have short-term benefits but long-term consequences.

For those working in senior managerial roles, this ability to think objectively can make a big difference to business success.

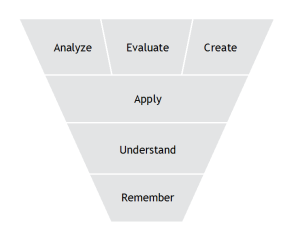

As part of the critical thinking assessment, the Watson Glaser Test focuses on the acronym, 'RED':

- R ecognize assumptions

- E valuate arguments

- D raw conclusions

Put simply, the RED model ensures you can understand how to move beyond subconscious bias in your thinking. It ensures that you can identify the truth and understand the differences between fact and opinion.

To recognize assumptions , you must understand yourself and others: what your thought patterns and past experiences have led you to conclude about the world.

Evaluating arguments requires you to genuinely consider the merits of all options in a situation, and not just choose the one you feel that you ‘ought’ to.

Finally, to draw an accurate and beneficial conclusion you must trust your decision-making and understanding of the situation.

Watson Glaser Practice Test Questions & Answers

As mentioned earlier, the Watson Glaser Test assesses five core elements. Here, they will be examined in more depth:

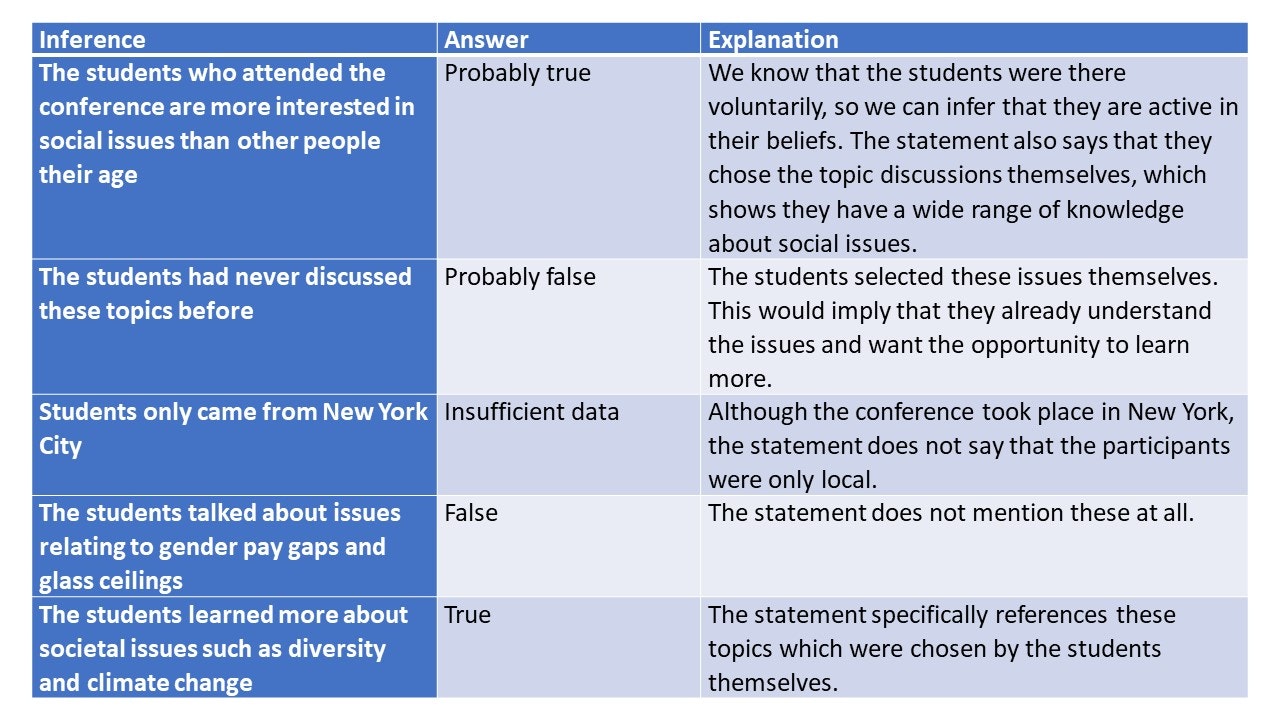

This part of the test is about your ability to draw conclusions based on facts . These facts may be directly provided or may be assumptions that you have previously made.

Within the assessment, you can expect to be provided with a selection of text. Along with the text will be a statement.

You may need to decide whether that statement is true, probably true, insufficient data (neither true nor false), probably false or false.

The test looks to see if your answer was based on a conclusion that could be inferred from the text provided or if it is based on an assumption you previously made.

Take a Watson Glaser Practice Test

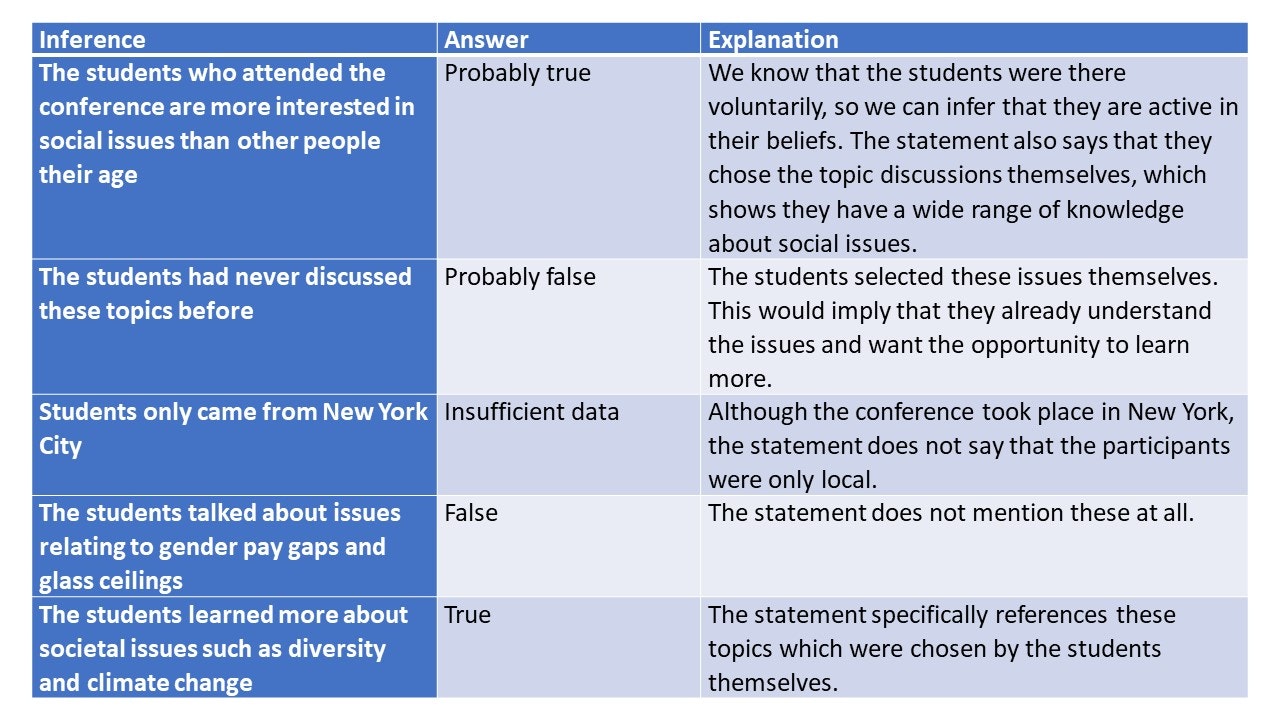

Example Statement:

500 students recently attended a voluntary conference in New York. During the conference, two of the main topics discussed were issues relating to diversity and climate change. This is because these are the two issues that the students selected that are important to them.

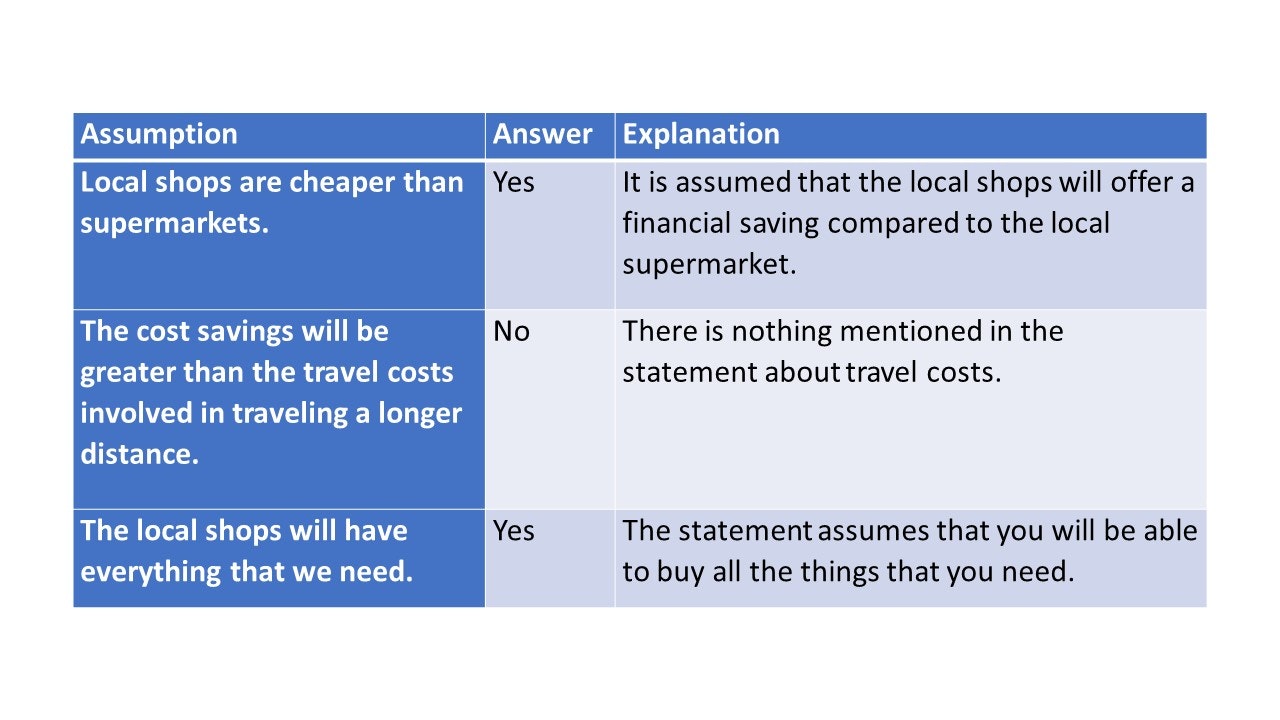

Many people make decisions based on assumptions. But you need to be able to identify when assumptions are being made.

Within the Watson Glaser test , you will be provided with a written statement as well as an assumption.

You will be asked to declare whether that assumption was made in the text provided or not .

This is an important part of the test; it allows employers to understand if you have any expectations about whether things are true or not . For roles in law or finance, this is a vital skill.

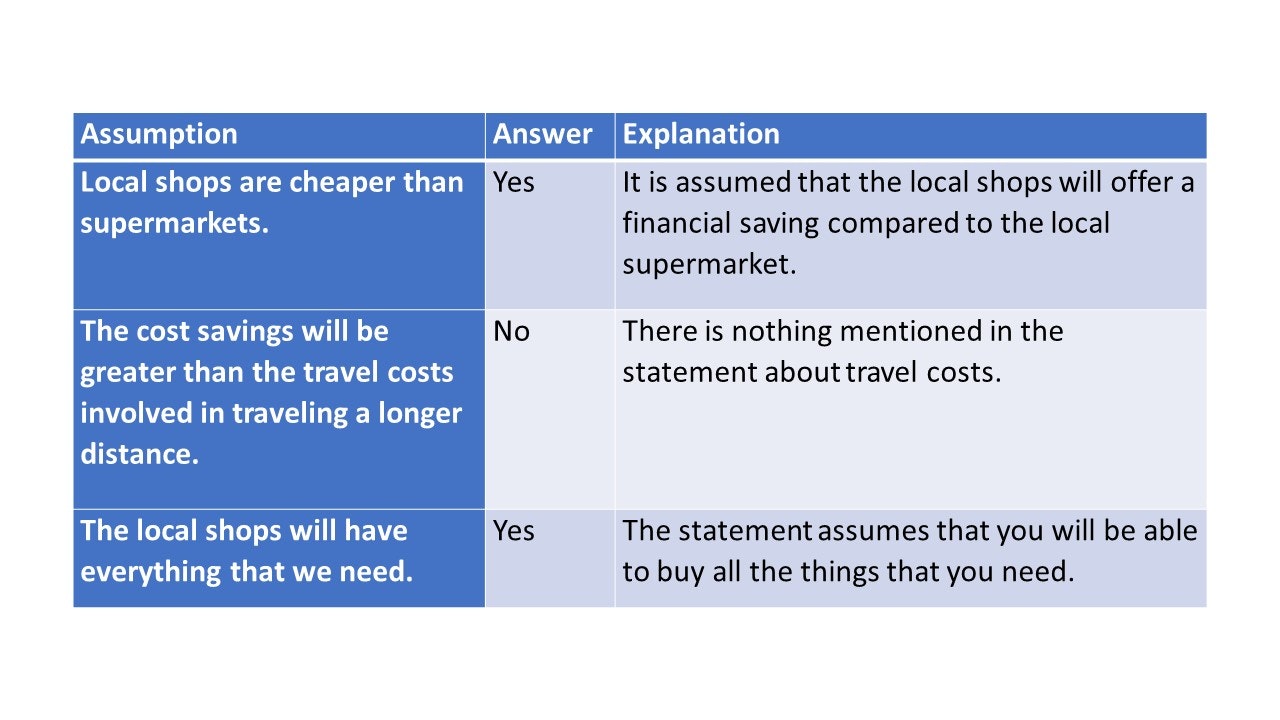

We need to save money, so we’ll visit the local shops in the nearest town rather than the local supermarket

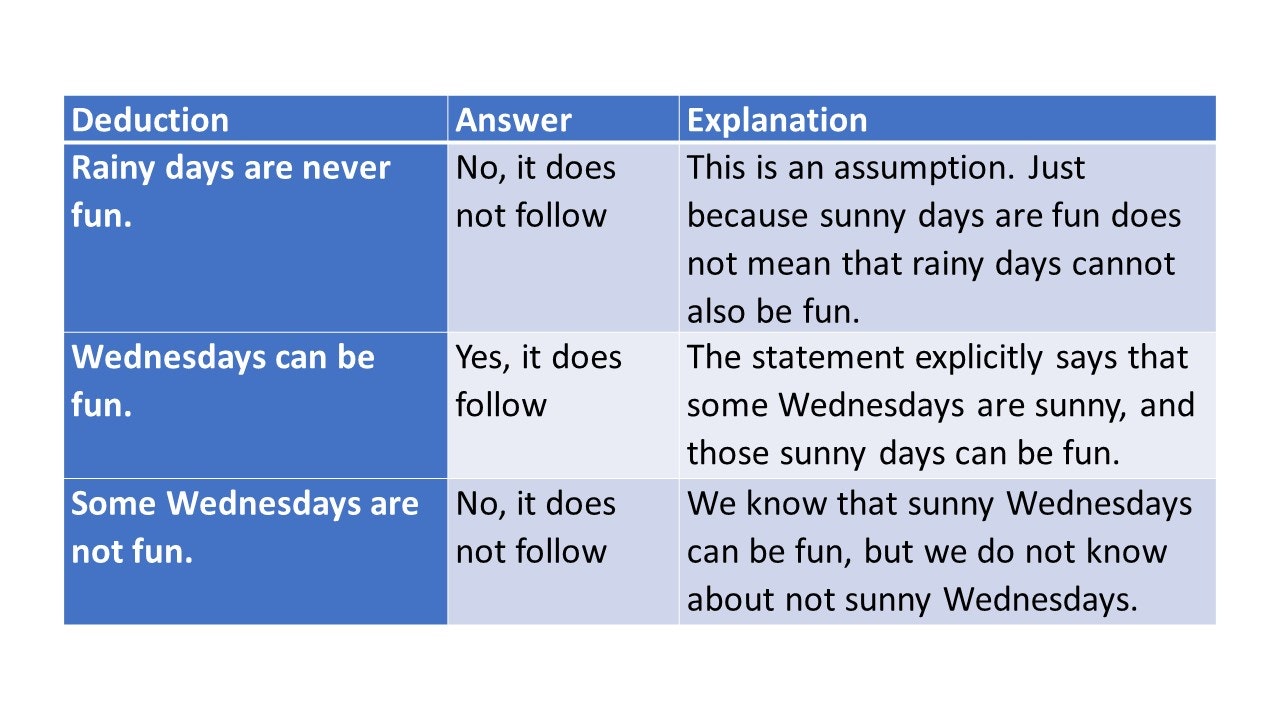

As a core part of critical thinking, 'deduction' is the ability to use logic and reasoning to come to an informed decision .

You will be presented with several facts, along with a variety of conclusions. You will be tasked with confirming whether those conclusions can be made from the information provided in that statement.

The answers are commonly in a ‘Yes, it follows/No, it does not follow’ form.

It is sometimes sunny on Wednesdays. All sunny days are fun. Therefore…

If you need to prepare for a number of different employment tests and want to outsmart the competition, choose a Premium Membership from TestHQ . You will get access to three PrepPacks of your choice, from a database that covers all the major test providers and employers and tailored profession packs.

Get a Premium Package Now

Critical thinking is also about interpreting the information correctly. It is about using the information provided to come to a valuable, informed decision .

Like the deduction questions, you will be provided with a written statement, which you must assume to be true.

You will also be provided with a suggested interpretation of that written statement. You must decide if that interpretation is correct based on the information provided, using a yes/no format.

A study of toddlers shows that their speech can change significantly between the ages of 10 months and three years old. At 1 year old, a child may learn their first word whereas at three years old they may know 200 words

Evaluation of Arguments

This final part requires you to identify whether an argument is strong or weak . You will be presented with a written statement and several arguments that can be used for or against it. You need to identify which is the strongest argument and which is the weakest based on the information provided.

Should all 18-year-olds go to college to study for a degree after they have graduated from high school?

There are no confirmed pass/fail scores for Watson Glaser tests; different sectors have different interpretations of what is a good score .

Law firms, for example, will require a pass mark of at least 75–80% because the ability to think critically is an essential aspect of working as a lawyer.

As a comparative test, you need to consider what the comparative ‘norm’ is for your chosen profession. Your score will be compared to other candidates taking the test and you need to score better than them.

It is important to try and score as highly as you possibly can. Your Watson Glaser test score can set you apart from other candidates; you need to impress the recruiters as much as possible.

Your best chance of achieving a high score is to practice as much as possible in advance.

Everyone will have their own preferred study methods, and what works for one person may not necessarily work for another.

However, there are some basic techniques everyone can use, which will enhance your study preparation ahead of the test:

Step 1 . Pay Attention to Online Practice Tests

There are numerous free online training aids available; these can be beneficial as a starting point to your preparation.

However, it should be noted that they are often not as detailed as the actual exam questions.

When researching for online test questions, make sure that any questions are specific to the Watson Glaser Test , not just critical thinking.

General critical thinking questions can help you improve your skills but will not familiarize you with this test. Therefore, make sure you practice any questions which follow the ‘rules’ and structure of a Watson Glaser Test .

Step 2 . Paid-for Preparation Packs Can Be Effective

If you are looking for something that mimics the complexity of a Watson Glaser test , you may wish to look at investing in a preparation pack.

There are plenty of options available from sites such as TestHQ . These are often far more comprehensive than free practice tests.

They may also include specific drills (which take you through each of the five stages of the test) as well as study guides, practice tests and suggestions of how to improve your score.

Psychologically, if you have purchased a preparation pack, you may be more inclined to increase your pre-test practice/study when compared to using free tools, due to having invested money.

Step 3 . Apply Critical Thinking to All Aspects of Your Daily Routine

The best way to improve your critical thinking score is to practice it every day.

It is not just about using your skills to pass an exam question; it is about being able to think critically in everyday scenarios.

Therefore, when you are reading the news or online articles, try to think whether you are being given facts or you are making deductions and assumptions from the information provided.

The more you practice your critical thinking in these scenarios, the more it will become second nature to you.

You could revert to the RED model: recognize the assumptions being made, by you and the author; evaluate the arguments and decide which, if any, are strong; and draw conclusions from the information provided and perhaps see if they differ from conclusions drawn using your external knowledge.

Prepare for Watson Glaser Test with TestHQ

Nine Top Tips for Ensuring Success in Your Watson Glaser Test

If you are getting ready to participate in a Watson Glaser test, you must be clear about what you are being asked to do.

Here are a few tips that can help you to improve your Watson Glaser test score.

1. Practice, Practice, Practice

Critical thinking is a skill that should become second nature to you. You should practice as much as possible, not just so that you can pass the test, but also to feel confident in using your skills in reality.

2. The Best Success Is Based on the Long-Term Study

To succeed in your Watson Glaser test , you need to spend time preparing.

Those who begin studying in the weeks and months beforehand will be far more successful than those who leave their study to the last minute.

3. Acquaint Yourself With the Test Format

The Watson Glaser test has a different type of question to other critical thinking tests.

Make sure that you are aware of what to expect from the test questions. The last thing you want is to be surprised on test day.

4. Read the Instructions Carefully

This is one of the simplest but most effective tips. Your critical thinking skills start with understanding what you are being asked to do. Take your time over the question.

Although you may only have 30 minutes to complete the test, it is still important that you do not rush through and submit the wrong answers. You do not get a higher score if you finish early, so use your time wisely.

5. Only Use the Information Provided in the Question

Remember, the purpose of the test is to see if you can come to a decision based on the provided written statement.

This means that you must ignore anything that you think you already know and focus only on the information given in the question.

6. Widen Your Non-Fictional Reading

Reading a variety of journals, newspapers and reports, and watching examples of debates and arguments will help you to improve your skills.

You will start to understand how the same basic facts can be presented in different ways and cause people to draw different conclusions.

From there, you can start to enhance your critical thinking skills to go beyond the perspective provided in any given situation.

7. Be Self-Aware

We all have our own biases and prejudices whether we know them or not. It is important to think about how your own opinions and life experiences may impact how you perceive and understand situations.

For example, someone who has grown up with a lot of money may have a different interpretation of what it is like to go without, compared to someone who has grown up in extreme poverty.

It is important to have this self-awareness as it is important for understanding other people; this is useful if you are working in sectors such as law.

8. Read the Explanations During Your Preparation

To make the most of practice tests, make sure you read the analysis explaining the answers, regardless of if you got the question right or wrong.

This is the crux of your study; it will explain the reasoning why a certain answer is correct, and this will help you understand how to choose the correct answers.

9. Practice Your Timings

You know that you will have five sections to complete in the test. You also know that you have 30 minutes to complete the test.

Therefore, make sure that your timings are in sync within your practice, so you can work your way through the test in its entirety.

Time yourself on how long each section takes you and put in extra work on your slowest.

What score do you need to pass the Watson Glaser test?

There is no standard benchmark score to pass the Watson Glaser test . Each business sector has its own perception of what constitutes a good score and every employer will set its own requirements.

It is wise to aim for a Watson Glaser test score of at least 75%. To score 75% or higher, you will need to correctly answer at least 30 of the 40 questions.

The employing organization will use your test results to compare your performance with other candidates within the selection pool. The higher you score in the Watson Glaser test , the better your chances of being hired.

Can you fail a Watson Glaser test?

It is not possible to fail a Watson Glaser test . However, your score may not be high enough to meet the benchmark set by the employing organization.

By aiming for a score of at least 75%, you stand a good chance of progressing to the next stage of the recruitment process.

Are Watson Glaser tests hard?

Many candidates find the Watson Glaser test hard. The test is designed to assess five different aspects of logical reasoning skills. Candidates must work under pressure, which adds another dimension of difficulty.

By practicing your critical thinking skills, you can improve your chances of achieving a high score on the Watson Glaser test .

How do I prepare for Watson Glaser?

To prepare for Watson Glaser , you will need to practice your critical thinking abilities. This can be achieved through a range of activities; for example, reading a variety of newspapers, journals and other literature.

Try applying the RED model to your reading – recognize the assumptions being made (both by you and the writer), evaluate the arguments and decide which of these (if any) are strong.

You should also practice drawing conclusions from the information available to you.

Online Watson Glaser practice assessments are a useful way to prepare for Watson Glaser. These practice tests will give you an idea of what to expect on the day, although the questions are not usually as detailed as those in the actual test.

You might also consider using a paid-for Watson Glaser preparation pack, such as the one available from TestHQ . Preparation packs provide a comprehensive test guide, including practice tests and recommendations on how to improve your test score.

How long does the Watson Glaser test take?

Candidates are allowed 30 minutes to complete the Watson Glaser test . The multiple-choice test questions are grouped into five distinct areas – assumptions, deduction, evaluation, inference and interpretation.

Which firms use the Watson Glaser test?

Companies all over the world use the Watson Glaser test as part of their recruitment campaigns.

It is a popular choice for professional service firms, including banking, law, and insurance. Firms using the Watson Glaser test include the Bank of England, Hiscox, Deloitte and Clifford Chance.

How many times can you take the Watson Glaser test?

Most employers will only allow you to take the Watson Glaser test once per application. However, you may take the Watson Glaser test more than once throughout your career.

What is the next step after passing the Watson Glaser test?

The next step after passing the Watson Glaser test will vary between employers. Some firms will ask you to attend a face-to-face interview after passing the Watson Glaser test, others will ask you to attend an assessment center. Speak to the hiring manager to find out the process for the firm you are applying for.

Start preparing in advance for the Watson Glaser test

The Watson Glaser test differs from other critical thinking tests. It has its own rules and formations, and the exam is incredibly competitive. If you are asked to participate in a Watson Glaser test it is because your prospective employer is looking for the ‘best of the best’. Your aim is not to simply pass the test; it is to achieve a higher score than anyone else taking that test .

Therefore, taking the time to prepare for the Watson Glaser test is vital for your chances of success. You need to be confident that you know what you are being asked to do, and that you can use your critical thinking skills to make informed decisions.

Your study is about more than helping you to pass a test; it is about providing you with the skills and capability to think critically about information in the ‘real world’ .

You might also be interested in these other Psychometric Success articles:

Or explore the Aptitude Tests / Test Types sections.

Critical Thinking Test Practice ▷ Free Critical Reasoning Samples & Tips 2024

Employers? Hire Better With Our Aptitude Test

Start Preparing for Your Critical Thinking Test. This page features a brief introduction, followed by question examples with detailed explanations, and a free test sample.

Table of Contents :

✻ What is a Critical Thinking Test ?

✻ Sample Questions

Related links

✻ Free Critical Thinking Practice Test

✻ Watson Glaser Practice Test

Have you been invited to take a Watson Glaser Test ? Access our tailored prep and our Free Watson Glaser Test .

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking, also known as critical reasoning, is the ability to assess a situation and consider/understand various perspectives, all while acknowledging, extracting and deciphering facts, opinions and assumptions. Critical thinking tests are a sub-type of aptitude exams or psychometric tests used in pre-employment assessment for jobs reacquiring advanced analytical and learning skills.

The Skills You Will Be Tested On

Critical thinking tests can have 5 major sections or sub-tests that assess and measure a variety of aspects.

1) Inference

In this section, you are asked to draw conclusions from observed or supposed facts. You are presented with a short text containing a set of facts you should consider as true.

Below the text is a statement that could be inferred from the text. You need to make a judgement on whether this statement is valid or not, based on what you have read.

Furthermore, you are asked to evaluate whether the statement is true, probably true, there is insufficient data to determine, probably false, or false.

For example: if a baby is crying and it is his feeding time, you may infer that the baby is hungry. However, the baby may be crying for other reasons—perhaps it is hot.

2) Recognising Assumptions

In this section, you are asked to recognise whether an assumption is justifiable or not.

Here you are given a statement followed by an assumption on that statement. You need to establish whether this assumption can be supported by the statement or not.

You are being tested on your ability to avoid taking things for granted that are not necessarily true. For example, you may say, "I’ll have the same job in three months," but you would be taking for granted the fact that your workplace won't make you redundant, or that you won’t decide to quit and explore various other possibilities.

You are asked to choose between the options of assumption made and assumption not made.

3) Deduction

This section tests your ability to weigh information and decide whether given conclusions are warranted.

You are presented with a statement of facts followed by a conclusion on what you have read. For example, you may be told, "Nobody in authority can avoid making uncomfortable decisions."

You must then decide whether a statement such as "All people must make uncomfortable decisions" is warranted from the first statement.

You need to assess whether the conclusion follows or the conclusion does not follow what is contained in the statement. You can read more about our deductive logical thinking test resources here.

4) Interpretation

This section measures your ability to understand the weighing of different arguments on a particular question or issue.

You are given a short paragraph to read, which you are expected to take as true. This paragraph is followed by a suggested conclusion, for which you must decide if it follows beyond a reasonable doubt.

You have the choice of conclusion follows and conclusion does not follow.

5) Evaluation of Arguments

In this section you are asked to evaluate the strength of an argument.

You are given a question followed by an argument. The argument is considered to be true, but you must decide whether it is a strong or weak argument, i.e. whether it is both important and directly related to the question.

Ace Your Job Search with a Custom Prep Kit

Job hunting doesn't have to be stressful. Prepare smarter and ace your interviews faster with our Premium Membership.

Critical Thinking Question Examples

As there are various forms of critical thinking and critical reasoning, we've provided a number of critical thinking sample questions.

You can take our full Critical Thinking Sample Test to see more questions.

Argument Analysis Sample Question

Which of the following is true?

- Most of the people surveyed, whether they own pets or do not own pets, displayed outstanding interpersonal capacities.

- The adoption of a pet involves personal sacrifice and occasional inconvenience.

- People with high degrees of empathy are more likely to adopt pets than people with low degrees of empathy.

- Interpersonal capacities entail tuning in to all the little signals necessary to operate as a couple.

- A person's degree of empathy is highly correlated with his or her capacity for personal sacrifice.

The correct answer is C

Answer explanation: In a question of this type, the rule is very simple: the main conclusion of an argument is found either in the first or the last sentence. If, however, the main conclusion appears in the middle of an argument, it will begin with a signal word such as thus, therefore, or so. Regardless of where the main conclusion appears, the rest of the passage will give the reasons why the conclusion is true or should be adopted. The main conclusion in this passage is the last sentence, signaled by the words, 'This indicates that people who are especially empathetic are more likely to adopt a pet than people who are less empathetic'.

Argument Practice Sample Question

A: No. Differential bonuses have been found to create a hostile working environment, which leads to a decrease in the quality and quantity of products .

This argument is:

The correct answer is A (Strong)

Schema of the statement: Differential cash bonuses (productivity↑) → workplace↑

Explanation: This argument targets both the action and the consequences of the action on the object of the statement. It states that the action (implementing differential cash bonuses) has a negative effect on the workplace (a decrease in the quality and quantity of products). Therefore, it is an important argument, one that is relevant for the workplace. Note that this argument does not specifically target differential cash bonuses. Still, they are considered a sub-group of the subject of the argument (differential bonuses).

Interpretations Sample Question

Proposed assumption: Vicki and Bill encountered a personal battle because they couldn’t come to terms with their disease.

A. Conclusion follows

B. Conclusion does not follow

The correct answer is B (Conclusion does not follow)

It is plausible that the reason people who suffer from sleep apnoea encounter a personal battle is because of an inability to come to terms with this disease. However, since the passage does not provide an actual reason, you cannot reach this conclusion without reasonable doubt.

The most common type of Critical Thinking Assessment is the Watson Glaser .

Difficult and time-pressured, the Watsong Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA) takes a unique testing approach that breaks away from more traditional assessments. To see examples, check out our free Watson Glaser practice test .

Our expertly curated practice programme for the Watson Glaser will provide you with:

- A full-length diagnostic simulation

- Focused practice tests for the different test sections: inferences, assumptions, deductive reasoning, interpretations, and arguments.

- 3 additional full-length simulations

- Interactive tutorials

Or learn more about the Watson Glaser Test.

| Free Critical Thinking Test Sample Complete your test to get a predicted score, then review your answers |

| Test Time | 18:45 min |

| Questions | 25 (5 sections) |

| Pass Score | 8 |

Critical Thinking Tests FAQs

What critical reasoning test am I most likely to take?

Very Likely the Watson-Glaser test

Another popular critical thinking assessment, Watson-Glaser is a well-established psychometric test produced by Pearson Assessments.

The Watson-Glaser test is used for two main purposes: job selection/talent management and academic evaluations. The Watson-Glaser test can be administered online or in-person.

For Watson Glaser practice questions, click here !

What skills do critical reasoning test measure?

Critical Thinking can refer to various skills:

- Defining the problem

- Selecting the relevant information to solve the problem

- Recognising assumptions that are both written and implied in the text

- Creating hypotheses and selecting the most relevant and credible solutions

- Reaching valid conclusions and judging the validity of inferences

Pearson TalentLens condenses critical thinking into three major areas:

- R ecognise assumptions – the ability to notice and question assumptions, recognise information gaps or unfounded logic. Basically not taking anything for granted.

- E valuate arguments – the ability to analyse information objectively without letting your emotions affect your opinion.

- D raw conclusions – the ability to reach focused conclusions and inferences by considering diverse information, avoiding generalisations and disregarding information that is not available.

These are abilities that employers highly value in their employees, because they come into play in many stages of problem-solving and decision-making processes in the workplace, especially in business, management and law.

Why are critical thinking tests important to employers?

Critical thinking, or critical reasoning, is important to employers because they want to see that when dealing with an issue, you are able to make logical decisions without involving emotions.

Being able to look past emotions will help you to be open-minded, confident, and decisive—making your decisions more logical and sound.

What professions use critical thinking tests?

Below are some professions that use critical thinking tests and assessments during the hiring process as well as some positions that demand critical thinking and reasoning skills:

Preparation Packs for Critical Thinking & Critical Reasoning Assessmentsץ The Critical Thinking PrepPack™ provides you with the largest assembly of practice tests, study guides and tutorials. Our tests come complete with straightforward expert explanations and predictive score reports to let you know your skill level as well as your advancement. By using our materials you can significantly increase your potential within a few days and secure yourself better chances to get the job.

Create Your Custom Assessment Prep Kit

Job-seeking can be a long and frustrating process, often taking months and involving numerous pre-employment tests and interviews. To guide you through it, we offer a Premium Membership .

Choose 3 Preparation Packs at 50% discount for 1, 3, or 6 months.

Are you about to apply for a role in the finance industry?

Several major banking and consulting employers evaluate their applicants using critical thinking tests, among other methods. Visit your potential employer's page to better understand the tests you are about to face, and start preparing today!

HSBC | UBS | Bain & Co | Macquarie | Morgan Stanley | Barclays | EIB | Deloitte | Deutsche Bank | KPMG | PWC | Lazard | EY | Nomura | BCG | BNP Paribas | Jefferies | Moelis & Co

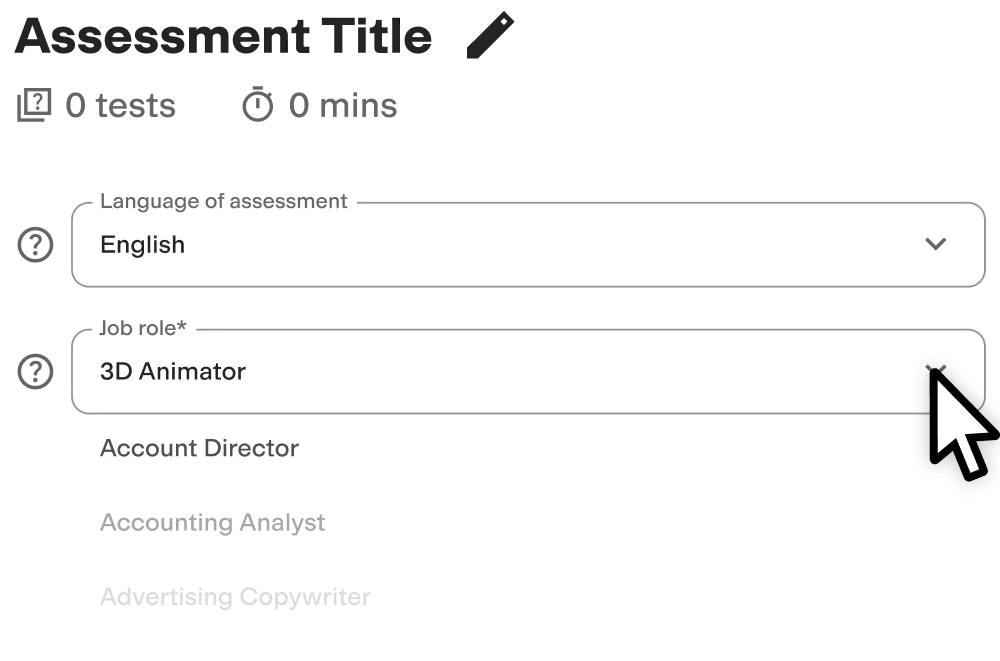

Fill in the details of your test, and you will be redirected to the relevant page:

More on this topic

- Watson Glaser Practice Test

- Clifford Chance Watson Glaser

- Linklaters Watson Glaser

- Hogan Lovells Watson Glaser

- Watson Glaser & RANRA Practice Bundle

- ISEB Practice Test

Since 1992, JobTestPrep has stood for true-to-original online test and assessment centre preparation. Our decades of experience make us a leading international provider of test training. Over one million customers have already used our products to prepare professionally for their recruitment tests.

- Arabic Site

- United States

- TestPrep-Online

- Terms & Conditions

- Refund Policy

- Affiliate Programme

- Higher Education

- Student Beans

Critical Thinking test

Summary of the critical thinking test.

This online Critical Thinking skills assessment evaluates candidates’ skills in critical thinking through inductive and deductive reasoning problems . This pre-employment aptitude test helps you identify candidates who can evaluate information and make sound judgments using logic and analytical skills.

Covered skills

Analyzing syllogisms

Making inferences

Recognizing assumptions and fallacies

Weighing arguments

Use the Critical Thinking test to hire

Any role that involves a high degree of critical and independent thinking to solve complex problems, such as analysts, engineers, executives, lawyers, marketers, and data scientists, among many others.

About the Critical Thinking test

Effective critical thinking requires skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, and evaluating information to make a sound, logical judgment or formulate an innovative solution.

In practice, this means that candidates can identify what information is important to solving a problem, gather it where possible, and draw conclusions to reach a solution. It requires using a range of soft skills and cognitive abilities, including:

Logical reasoning

Open-mindedness

Strategizing

These skills are difficult, or even impossible, to glean from a resume; employers should use critical thinking skills tests instead to assess them quickly and easily without bias.

Our Critical Thinking test evaluates candidates’ abilities to:

Solve syllogisms through deductive reasoning skills and logical thinking

Interpret sequences and arrangements, evaluate arguments to find a weak argument, and draw sound conclusions

Ask deduction questions and assess cause-and-effect relationships

Practice reading comprehension to recognize assumptions

These types of questions ( see our practice test for sample questions ) measure critical thinking by presenting candidates with single or multiple-choice statements, asking them to analyze the information and use logic to identify the correct answer.

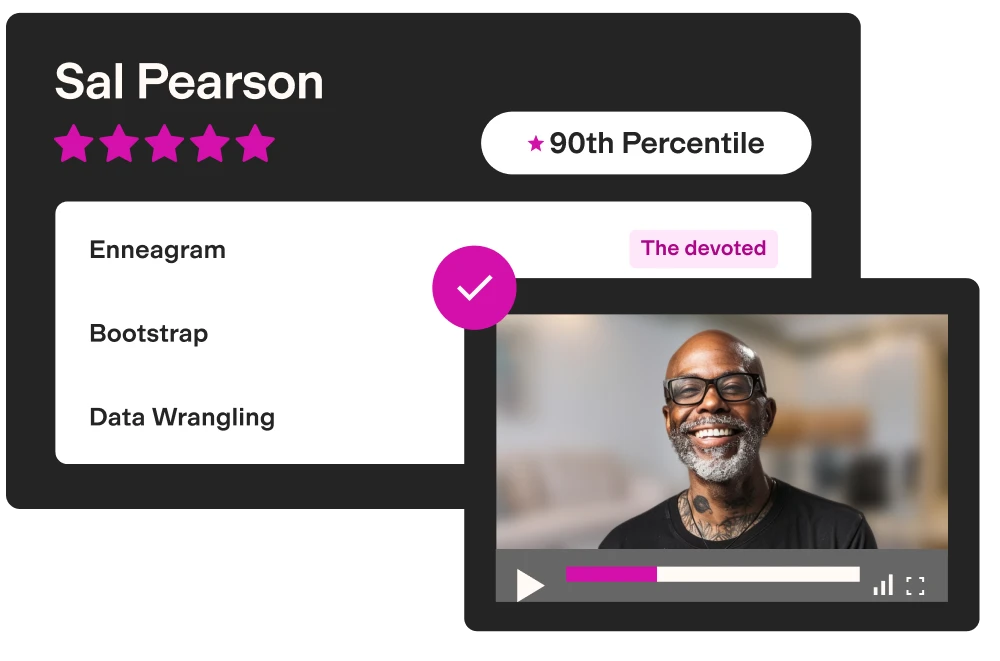

By using a critical thinking assessment test to screen candidates with a time limit, you can ensure that everyone you invite to interviews meets a baseline requirement for critical thinking skills. Besides, you reach this conclusion through a data-driven, unbiased method that takes a fraction of the time of traditional resume screening.

The test is made by a subject-matter expert

Testgorilla assessment team.

TestGorilla's Assessment Team is responsible for the delivery of leading edge, science-based measurement, assessment content, insights and innovation. The team is comprised of organizational psychologists, data scientists, psychometricians, academics, researchers, writers, and editors.

Collectively, the Assessment Team boasts more than 15 advanced degrees, more than 100 scientific publications and presentations, and almost 100 years of assessment and talent acquisition industry experience.

Crafted with expert knowledge

TestGorilla’s tests are created by subject matter experts. We assess potential subject-matter experts based on their knowledge, ability, and reputation. Before being published, each test is peer-reviewed by another expert, then calibrated using hundreds of test takers with relevant experience in the subject.

Our feedback mechanisms and unique algorithms allow our subject-matter experts to constantly improve their tests.

What our customers are saying

TestGorilla helps me to assess engineers rapidly. Creating assessments for different positions is easy due to pre-existing templates. You can create an assessment in less than 2 minutes. The interface is intuitive and it’s easy to visualize results per assessment.

VP of engineering, mid-market (51-1000 FTE)

Any tool can have functions—bells and whistles. Not every tool comes armed with staff passionate about making the user experience positive.

The TestGorilla team only offers useful insights to user challenges, they engage in conversation.

For instance, I recently asked a question about a Python test I intended to implement. Instead of receiving “oh, that test would work perfectly for your solution,” or, “at this time we’re thinking about implementing a solution that may or may not…” I received a direct and straightforward answer with additional thoughts to help shape the solution.

I hope that TestGorilla realizes the value proposition in their work is not only the platform but the type of support that’s provided.

For a bit of context—I am a diversity recruiter trying to create a platform that removes bias from the hiring process and encourages the discovery of new and unseen talent.

Chief Talent Connector, small business (50 or fewer FTE)

Use TestGorilla to hire the best faster, easier and bias-free

Our screening tests identify the best candidates and make your hiring decisions faster, easier, and bias-free.

Learn how each candidate performs on the job using our library of 400+ scientifically validated tests.

Test candidates for job-specific skills like coding or digital marketing, as well as general skills like critical thinking. Our unique personality and culture tests allow you to get to know your applicants as real people – not just pieces of paper.

Give all applicants an equal, unbiased opportunity to showcase their skills with our data-driven and performance-based ranking system.

With TestGorilla, you’ll get the best talent from all walks of life, allowing for a stronger, more diverse workplace.

Our short, customizable assessments and easy-to-use interface can be accessed from any device, with no login required.

Add your company logo, color theme, and more to leave a lasting impression that candidates will appreciate.

Watch what TestGorilla can do for you

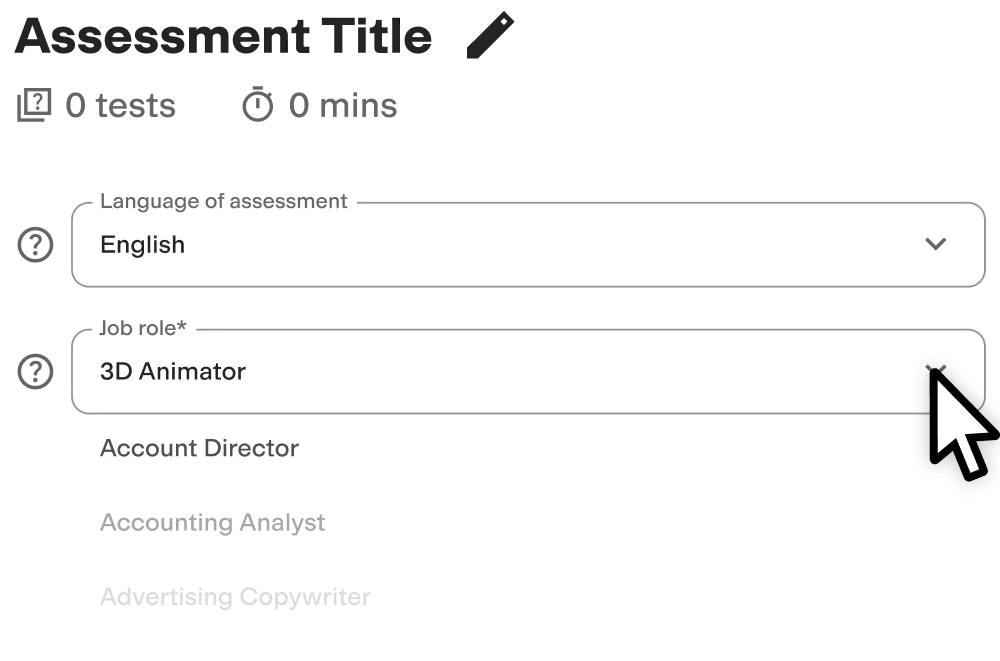

Create high-quality assessments, fast.

Building assessments is a breeze with TestGorilla. Get started with these simple steps.

Building assessments is quick and easy with TestGorilla. Just pick a name, select the tests you need, then add your own custom questions.

You can customize your assessments further by adding your company logo, color theme, and more. Build the assessment that works for you.

Send email invites directly from TestGorilla, straight from your ATS, or connect with candidates by sharing a direct link.

Have a long list of candidates? Easily send multiple invites with a single click. You can also customize your email invites.

Discover your strongest candidates with TestGorilla’s easy-to-read output reports, rankings, and analytics.

Easily switch from a comprehensive overview to a detailed analysis of your candidates. Then, go beyond the data by watching personalized candidate videos.

View a sample report

The Critical Thinking test will be included in a PDF report along with the other tests from your assessment. You can easily download and share this report with colleagues and candidates.

Why are critical thinking skills important to employers?

The importance of critical thinking abilities in the workplace comes from its ability to improve performance in almost any role. If a candidate can think critically about problems, they are likely to solve them faster and with less need for intervention from superiors .

Critical thinking practice is essential for managers, who regularly need to make decisions that affect multiple people and involve many variables. Other benefits of fostering critical thinking in the workplace include:

Encouraging creative problem-solving and organizational agility

Improving conflict resolution

Promoting ethical decision-making

Creating a culture of continuous learning

Asking all applicants to answer critical reasoning test questions can help you hire competent employees and effective managers on a global scale in a fraction of the time. Nexus HR, an HR services provider, did precisely this with our tests – reducing their “time-to-fill” metrics for open positions and improving the quality of hire, particularly in India and the Philippines.

Critical-thinking competencies to hire for

Candidates with critical-thinking skills have several competencies:

Observation skills: They constantly seek new information by asking others or observing their environment and the people around them.

Analysis: They can use fast thinking to analyze new situations, but they can also slow down and analyze situations by asking questions and conducting research.

Decision-making: After observing and analyzing the data available, candidates can critically evaluate the information at their disposal to make a data-driven decision .

Communication: A great critical thinker also knows the importance of communicating their decisions to those around them and understands how best to organize this information for others.

Problem-solving: The candidate can apply their skills in observing and analyzing data to decision-making and finding solutions to complex problems.

What job roles can you hire with our Critical Thinking test?

This Critical Thinking assessment test is not role-specific, which means you can use the Critical Thinking test for employment across any number of roles.

Here are a few examples:

Analysts must know how to interpret data, identify patterns, and provide actionable, feasible insights

Engineers use their critical thinking skills to tackle complex problems and devise effective solutions that meet or exceed safety standards

Chief executive officers must be able to shape organizational strategy, adapt to change, and inspire their workers to perform at their best

Lawyers analyze case law, construct arguments, and navigate legal complexities with sharp critical thinking

Marketers craft compelling brand messages and develop successful go-to-market strategies thanks to a mixture of research and strategic thinking

Data scientists rely on critical thinking skills to examine data sets, spot trends, and make informed business decisions

Teachers design tutorials, create practice questions, evaluate student performance, and adapt their teaching methods based on careful analysis and reflective judgment

Healthcare professionals use critical thinking skills to assess patient symptoms and devise appropriate care plans

Create a multi-measure assessment: 4 tests to pair with the Critical Thinking test

With TestGorilla, you can combine up to five psychometric tests into a multi-measure assessment to find well-rounded candidates.

Here are the tests you should consider including alongside our critical thinking evaluation in your recruitment process.

Communication test : Assess candidates’ ability to communicate clearly and professionally through written, verbal, or non-verbal communication.

Time Management test : Present candidates with typical workplace scenarios to assess how effectively they can prioritize, plan, and execute tasks.

Problem Solving test : Hire candidates with the ability to analyze and interpret textual information to make correct decisions.

Big Five (OCEAN) test : Evaluate candidates on five key factors of personality: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability.

Note: We haven’t included any role-specific skills tests here because they depend on the position you’re hiring for. However, we highly recommend you add at least one in your five-test assessment to ensure your candidates possess the right skills for the job.

An assessment is the total package of tests and custom questions that you put together to evaluate your candidates. Each individual test within an assessment is designed to test something specific, such as a job skill or language. An assessment can consist of up to 5 tests and 20 custom questions. You can have candidates respond to your custom questions in several ways, such as with a personalized video.

Yes! Custom questions are great for testing candidates in your own unique way. We support the following question types: video, multiple-choice, coding, file upload, and essay. Besides adding your own custom questions, you can also create your own tests.

A video question is a specific type of custom question you can add to your assessment. Video questions let you create a question and have your candidates use their webcam to record a video response. This is an excellent way to see how a candidate would conduct themselves in a live interview, and is especially useful for sales and hospitality roles. Some good examples of things to ask for video questions would be "Why do you want to work for our company?" or "Try to sell me an item you have on your desk right now."

Besides video questions, you can also add the following types of custom questions: multiple-choice, coding, file upload, and essay. Multiple-choice lets your candidates choose from a list of answers that you provide, coding lets you create a coding problem for them to solve, file upload allows your candidates to upload a file that you request (such as a resume or portfolio), and essay allows an open-ended text response to your question. You can learn more about different custom question types here .

Yes! You can add your own logo and company color theme to your assessments. This is a great way to leave a positive and lasting brand impression on your candidates.

Our team is always here to help. After you sign up, we’ll reach out to guide you through the first steps of setting up your TestGorilla account. If you have any further questions, you can contact our support team via email, chat or call. We also offer detailed guides in our extensive help center .

It depends! We offer five free tests, or unlimited access to our library of 400+ tests with the price based on your company size. Find more information on our pricing plans here , calculate the cost-benefit of using TestGorilla assessments, or speak to one of our sales team for your personalized demo and learn how we can help you revolutionize hiring today.

Yes. You can add up to five tests to each assessment.

We recommend using our assessment software as a pre-screening tool at the beginning of your recruitment process. You can add a link to the assessment in your job post or directly invite candidates by email.

TestGorilla replaces traditional resume screening with a much more reliable and efficient process, designed to find the most skilled candidates earlier and faster.

We offer the following cognitive ability tests : Numerical Reasoning, Problem Solving, Attention to Detail, Reading Comprehension, and Critical Thinking.

Our cognitive ability tests allow you to test for skills that are difficult to evaluate in an interview. Check out our blog on why these tests are so useful and how to choose the best one for your assessment.

Related tests

Intermediate math, mechanical reasoning, attention to detail (textual), verbal reasoning, problem solving, numerical reasoning, computational thinking, basic math calculations, understanding instructions, attention to detail (visual).

Get 25% off all test packages.

Get 25% off all test packages!

Click below to get 25% off all test packages.

Critical Thinking Tests

Critical thinking tests, sometimes known as critical reasoning tests, are often used by employers. They evaluate how a candidate makes logical deductions after scrutinising the evidence provided, while avoiding fallacies or non-factual opinions. Critical thinking tests can form part of an assessment day, or be used as a screening test before an interview.

What is a critical thinking test?

A critical thinking test assesses your ability to use a range of logical skills to evaluate given information and make a judgement. The test is presented in such a way that candidates are expected to quickly scrutinise the evidence presented and decide on the strength of the arguments.

Critical thinking tests show potential employers that you do not just accept data and can avoid subconscious bias and opinions – instead, you can find logical connections between ideas and find alternative interpretations.

This test is usually timed, so quick, clear, logical thinking will help candidates get the best marks. Critical thinking tests are designed to be challenging, and often used as part of the application process for upper-management-level roles.

What does critical thinking mean?

Critical thinking is the intellectual skill set that ensures you can process and consider information, challenge and analyse data, and then reach a conclusion that can be defended and justified.

In the most simple terms, critical reasoning skills will make sure that you are not simply accepting information at face value with little or no supporting evidence.

It also means that you are less likely to be swayed by ‘false news’ or opinions that cannot be backed with facts – which is important in high-level jobs that require logical thinking.

For more information about logical thinking, please see our article all about logical reasoning .

Which professions use critical thinking tests, and why?

Typically, critical thinking tests are taken as part of the application process for jobs that require advanced skills in judgement, analysis and decision making. The higher the position, the more likely that you will need to demonstrate reliable critical reasoning and good logic.

The legal sector is the main industry that uses critical thinking assessments – making decisions based on facts, without opinion and intuition, is vital in legal matters.

A candidate for a legal role needs to demonstrate their intellectual skills in problem-solving without pre-existing knowledge or subconscious bias – and the critical thinking test is a simple and effective way to screen candidates.

Another industry that uses critical thinking tests as part of the recruitment process is banking. In a similar way to the legal sector, those that work in banking are required to make decisions without allowing emotion, intuition or opinion to cloud coherent analysis and conclusions.

Critical thinking tests also sometimes comprise part of the recruitment assessment for graduate and management positions across numerous industries.

The format of the test: which skills are tested?

The test itself, no matter the publisher, is multiple choice.

As a rule, the questions present a paragraph of information for a scenario that may include numerical data. There will then be a statement and a number of possible answers.

The critical thinking test is timed, so decisions need to be made quickly and accurately; in most tests there is a little less than a minute for each question. Having experience of the test structure and what each question is looking for will make the experience smoother for you.

There are typically five separate sections in a critical thinking test, and each section may have multiple questions.

Inference questions assess your ability to judge whether a statement is true, false, or impossible to determine based on the given data and scenario. You usually have five possible answers: absolutely true, absolutely false, possibly true, possibly false, or not possible to determine.

Assumptions

In this section, you are being assessed on your ability to avoid taking things for granted. Each question gives a scenario including data, and you need to evaluate whether there are any assumptions present.

Here you are given a scenario and a number of deductions that may be applicable. You need to assess the given deductions to see which is the logical conclusion – does it follow?

Interpretation

In the interpretation stage, you need to read and analyse a paragraph of information, then interpret a set of possible conclusions, to see which one is correct. You are looking for the conclusion that follows beyond reasonable doubt.

Evaluation of Arguments

In this section, you are given a scenario and a set of arguments that can be for or against. You need to determine which are strong arguments and which are weak, in terms of the information that you have. This decision is made based on the way they address the scenario and how relevant they are to the content.

How best to prepare for a critical thinking test

The best way to prepare for any type of aptitude test is to practice, and critical thinking tests are no different.

Taking practice tests, as mentioned above, will give you confidence as it makes you better understand the structure, layout and timing of the real tests, so you can concentrate on the actual scenarios and questions.

Practice tests should be timed. This will help you get used to working through the scenarios and assessing the conclusions under time constraints – which is a good way to make sure that you perform quickly as well as accurately.

In some thinking skills assessments , a timer will be built in, but you might need to time yourself.

Consistent practice will also enable you to pinpoint any areas of the critical thinking test that require improvement. Our tests offer explanations for each answer, similar to the examples provided above.

Publishers of critical thinking tests

The watson glaser critical thinking test.

The Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (W-GCTA) is the most popular and widely used critical thinking test. This test has been in development for 85 years and is published by TalentLens .

The W-GCTA is seen as a successful tool for assessing cognitive abilities, allowing recruiting managers to predict job success, find good managers and identify future leaders. It is available in multiple languages including English, French and Spanish.

The test itself can be used as part of an assessment day or as a screening assessment before an interview. It consists of 40 questions on the 5 sections mentioned above, and is timed at 30 minutes. Click here for more information on Watson Glaser tests .

SHL critical reasoning test

SHL is a major aptitude test publisher, which offers critical thinking as part of its testing battery for pre-employment checks.

SHL tests cover all kinds of behavioural and aptitude tests, from logic to inference, verbal to numerical – and with a number of test batteries available online, they are one of the most popular choices for recruiters.

Cornell critical thinking test

The Cornell critical thinking test was made to test students and first developed in 1985. It is an American system that helps teachers, parents and administrators to confidently predict future performance for college admission, gifted and advanced placement programs, and even career success.

Prepare yourself for leading employers

5 Example critical thinking practice questions with answers

In this section, you need to deduce whether the inferred statement is true, false or impossible to deduce.

The UK Government has published data that shows 82% of people under the age of 30 are not homeowners. A charity that helps homeless people has published data that shows 48% of people that are considered homeless are under 30.

The lack of affordable housing on the sales market is the reason so many under-30s are homeless.

- Definitely True

- Probably True

- Impossible to Deduce

- Probably False

- Definitely False

The information given does not infer the conclusion given, so it is impossible to deduce if the inference is correct – there is just not enough information to judge the inference as correct.

The removal of the five-substitution rule in British football will benefit clubs with a smaller roster.

Clubs with more money would prefer the five-substitute rule to continue.

Assumption Not Made

This is an example of a fallacy that could cause confusion for a candidate – it encourages you to bring in any pre-existing knowledge of football clubs.

It would be easy to assume the assumption has been made when you consider that the more money a club has, the more players they should have on the roster. However, the statement does not make the assumption that the clubs with more money would prefer to continue with the five-substitute rule.

All boys love football. Football is a sport, therefore:

- All boys love all sports

- Girls do not love football

- Boys are more likely to choose to play football than any other sport

In this section we are looking for the conclusion that follows the logic of the statement. In this example, we cannot deduce that girls do not love football, because there is not enough information to support that.

In the same way the conclusion that all boys love all sports does not follow – we are not given enough information to make that assumption. So, the conclusion that follows is 3: boys are more likely to choose football than any other sport because all boys like football.

The British Museum has a range of artefacts on display, including the largest privately owned collection of WWII weaponry.

There is a larger privately owned collection of WWII weaponry in the USA.

Conclusion Does Not Follow

The fact that the collection is in the British Museum does not make a difference to the fact it is the largest private collection – so there cannot be a larger collection elsewhere.

The Department for Education should lower standards in examinations to make it fairer for less able students.

- Yes – top grades are too hard for lower-income students

- No – less fortunate students are not capable of higher standards

- Yes – making the standards lower will benefit all students

- No – private school students will suffer if grade standards are lower

- The strongest argument is the right answer, not the one that you might personally believe.

In this case, we need to assess which argument is most relevant to the statement. Both 1 and 4 refer to students in particular situations, which isn’t relevant to the statement. The same can be said about 2, so the strongest argument is 3, since it is relevant and addresses the statement given.

Sample Critical Thinking Tests question Test your knowledge!

What implication can be drawn from the information in the passage?

A company’s internal audit revealed that departments with access to advanced analytics tools reported higher levels of strategic decision-making. These departments also showed a higher rate of reaching their quarterly objectives.

- Strategic decision-making has no link to the achievement of quarterly objectives.

- Access to advanced analytics does not influence a department's ability to make strategic decisions.

- Advanced analytics tools are the sole reason for departments reaching their quarterly objectives.

- Departments without access to advanced analytics tools are unable to make strategic decisions.

- Advanced analytics tools may facilitate better strategic decision-making, which can lead to the achievement of objectives.

After reading the passage below, what conclusion is best supported by the information provided?

- Job satisfaction increases when employees start their day earlier.

- Starting early may lead to more efficient task completion and less job-related stress.

- Workers who start their day later are more efficient at completing tasks.

- There is a direct correlation between job satisfaction and starting work early.

- The study concludes that job-related stress is unaffected by the start time of the workday.

Based on the passage below, which of the following assumptions is implicit?

- Inter-departmental cooperation is the sole factor influencing project completion rates.

- The increase in project completion rates is due entirely to the specialized team-building module.

- Team-building exercises have no effect on inter-departmental cooperation.

- The specialized team-building module may contribute to improvements in inter-departmental cooperation.

- Departments that have not undergone the training will experience a decrease in project completion rates.

What is the flaw in the argument presented in the passage below?

- The assumption that a casual dress code is suitable for all company types.

- High-tech companies have a casual dress code to increase employee productivity specifically.

- The argument correctly suggests that a casual dress code will increase employee morale in every company.

- Morale and productivity cannot be affected by a company's dress code.

- A casual dress code is more important than other factors in determining a company's success.

Which statement is an inference that can be drawn from the passage below?

- Telecommuting employees are less productive than on-site workers.

- The reduction in operational costs is directly caused by the increase in telecommuting employees.

- Telecommuting may have contributed to the decrease in operational costs.

- Operational costs are unaffected by employee work locations.

- The number of telecommuting employees has no impact on operational costs.

Start your success journey

Access one of our Watson Glaser tests for FREE.

The tests were well suited to the job that I’ve applied for. They are easy to do and loads of them.

Sophie used Practice Aptitude Tests to help pass her aptitude tests for Deloitte.

Hire better talent

At Neuroworx we help companies build perfect teams

Critical Thinking Tests Tips

The most important factor in your success will be practice. If you have taken some practice tests, not only will you start to recognise the way questions are worded and become familiar with what each question is looking for, you will also be able to find out whether there are any parts that you need extra practice with.

It is important to find out which test you will be taking, as some generic critical thinking practice tests might not help if you are taking specific publisher tests (see the section below).

2 Fact vs fallacy

Practice questions can also help you recognise the difference between fact and fallacy in the test. A fallacy is simply an error or something misleading in the scenario paragraph that encourages you to choose an invalid argument. This might be a presumption or a misconception, but if it isn’t spotted it can make finding the right answer impossible.

3 Ignore what you already know

There is no need for pre-existing knowledge to be brought into the test, so no research is needed. In fact, it is important that you ignore any subconscious bias when you are considering the questions – you need logic and facts to get the correct answer, not intuition or instinct.

4 Read everything carefully

Read all the given information thoroughly. This might sound straightforward, but knowing that the test is timed can encourage candidates to skip content and risk misunderstanding the content or miss crucial details.

During the test itself, you will receive instructions that will help you to understand what is being asked of you on each section. There is likely to be an example question and answer, so ensure you take the time to read them fully.

5 Stay aware of the time you've taken

This test is usually timed, so don’t spend too long on a question. If you feel it is going to take too much time, leave it and come back to it at the end (if you have time). Critical thinking tests are complex by design, so they do have quite generous time limits.

For further advice, check out our full set of tips for critical thinking tests .

Prepare for your Watson Glaser Assessments

Immediate access. Cancel anytime.

- 20 Aptitude packages

- 59 Language packages

- 110 Programming packages

- 39 Admissions packages

- 48 Personality packages

- 315 Employer packages

- 34 Publisher packages

- 35 Industry packages

- Dashboard performance tracking

- Full solutions and explanations

- Tips, tricks, guides and resources

- Access to free tests

- Basic performance tracking

- Solutions & explanations

- Tips and resources

Critical Thinking Tests FAQs

What are the basics of critical thinking.

In essence, critical thinking is the intellectual process of considering information on its merits, and reaching an analysis or conclusion from that information that can be defended and rationalised with evidence.

How do you know if you have good critical thinking skills?

You are likely to be someone with good critical thinking skills if you can build winning arguments; pick holes in someone’s theory if it’s inconsistent with known facts; reflect on the biases inherent in your own experiences and assumptions; and look at problems using a systematic methodology.

Reviews of our Watson Glaser tests

What our customers say about our Watson Glaser tests

Jozef Bailey

United Kingdom

April 05, 2022

Doesn't cover all aspects of Watson-Glaser tests but useful

The WGCTA uses more categories to assess critical thinking, but this was useful for the inference section.

April 01, 2022

Just practicing for an interview

Good information and liked that it had a countdown clock, to give you that real feel in the test situation.

Jerico Kadhir

March 31, 2022

Aptitude test

It was OK, I didn't understand personally whether or not the "cannot say" option was acceptable or not in a lot of the questions, as it may have been a trick option.

Salvarina Viknesuari

March 15, 2022

I like the test because the platform is simple and engaging while the test itself is different than most of the Watson Glaser tests I've taken.

Alexis Sheridan

March 02, 2022

Some of the ratios were harder than I thought!

I like how clear the design and layout is - makes things very easy (even if the content itself is not!)

Cyril Lekgetho

February 17, 2022

Mental arithmetic

I enjoyed the fact that there were multiple questions pertaining to one passage of information, rather than multiple passages. However I would've appreciated a more varied question type.

Madupoju Manish

February 16, 2022

Analytics are the best questions

I like the test because of its time schedule. The way the questions are prepared makes it easy to crack the original test.

Chelsea Franklin

February 02, 2022

Interesting

I haven't done something like this for ages. Very good for the brain - although I certainly experienced some fog whilst doing it.

[email protected]

January 04, 2022

Population/exchange rates were the hardest

Great test as it felt a bit time pressured. Very different types of questions in terms of difficulty.

faezeh tavakoli

January 02, 2022

More attention to detail + be more time conscious

It was asking about daily stuff we all deal with, but as an assessment it's scrutinising how we approach these problems.

By using our website you agree with our Cookie Policy.

Stack Exchange Network