Writing A Self-Compassion Letter: Helpful Tips & Samples

Of course, the purpose of writing a self-compassion letter is to cultivate and enhance kindness and compassion for yourself.

A self-compassion letter can also be a powerful tool for self-reflection, self-forgiveness , and emotional healing.

This precise guide gives you tips, example samples, and strategies to write your first self-compassion letter.

5 Tips For Writing A Self-Compassion Letter

- Practice writing self-compassion letters weekly or at least once a month for sustainable effects.

- Make your self-compassion letter personal and genuine, addressing your specific feelings and situations to create a deeper connection and foster emotional healing.

- Understand that feeling self-compassion may not be immediate; it takes time to foster a positive relationship with yourself.

- If writing from an imaginary friend’s perspective is uncomfortable, consider using the viewpoint of a loved one, best friend, or mentor who cares deeply for you.

- Feel free to substitute perspectives with any of the mentioned alternatives for a more comfortable experience.

How To Write A Self-Compassion Letter

To write a self-compassion letter, follow these steps:

• Reflect on an aspect of yourself that triggers feelings of shame, insecurity, or inadequacy. This could be linked to your personality, behavior, abilities, relationships, or any other area of your life. Note it down and describe the emotions it evokes.

• Acknowledge and validate your emotions. Recognize that it is normal to feel this way and that everyone experiences similar feelings at times. Remind yourself that you are not alone in your struggle.

• Imagine how you would respond to a close friend who was experiencing the same issue. Consider the compassionate, supportive, and understanding words you would use to comfort them.

• Write the letter as if you were addressing that friend , but direct the words of compassion, empathy, and encouragement toward yourself. Be gentle and patient with your feelings, and avoid harsh judgment or criticism.

• Include specific examples of your strengths and accomplishments to help counterbalance the negative thoughts and feelings you are experiencing. Focus on your growth and resilience.

• Conclude the letter with a memorable, authentic quote that resonates with you and reinforces the message of self-compassion, as these:

“Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.” — Plato

“Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them, humanity cannot survive.” — Dalai Lama

“To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Self-Compassion Letter Samples

Sample Letter Example 1:

Dear [Your Name], I want to remind you of the incredible strength and resilience you possess. Life can be challenging, and you’ve faced many obstacles with courage and determination. Now, when you’re experiencing setbacks, is the time to acknowledge your accomplishments and be feel good about yourself. Remember that everyone faces challenges, and it’s a natural part of the human experience. Start treating yourself with the same compassion and understanding you extend to others. You are not alone in your struggles; you have YOU. And it’s okay to seek support from otjhes when you need it. Take breaks and practice self-care. Allow yourself the space to feel your emotions and process your experiences. Do things that bring you joy and help you recharge, whether it’s spending time in nature, enjoying a hobby, or connecting with loved ones. Take a moment to appreciate your journey so far and recognize your growth. You are unique and valuable, and your contributions make a difference. Remember. you deserve your kindness, compassion, and care, just as much as anyone else. August 9, 2024 7:20 am 33 Letters of Compassion: To: The Unseen. Love, Rosie With love and support, [Your Name]

Sample Letter Example 2:

Dear [Your Name], Remember, you deserve all the love, care, and kindness you give to your best friend. You’ve supported others numerous times, and now it’s crucial to support yourself too. Facing challenges or setbacks, be gentle with yourself, knowing nobody is perfect and mistakes are natural. Offer yourself the same patience and understanding as you would to your best friend. Celebrate your strengths and achievements without dwelling on your perceived shortcomings. Embrace your successes and focus on your personal growth and resilience, just as your best friend would encourage you to do. Prioritize self-care and well-being, engaging in activities that bring joy, relaxation, and self-connection. Surround yourself with uplifting people who offer love and support when needed (and get rid of toxic people in your life ). During your moments of self-doubt or hardship, remind yourself that you’re deserving of compassion, empathy, and love, just like your best friend. Your journey showcases your strength and character, so extend the same kindness and warmth to yourself as you would to your closest friend. With love and encouragement, [Your Name]

What are the benefits of a self-compassion letter?

Writing self-compassionate letters can increase self-compassion, improve well-being, and boost motivation for self-improvement. Shapira & Mongrain (2010) found that writing a letter to yourself from the perspective of a compassionate other can decrease depressive symptoms and increase happiness over time. Breines and Chen (2012) discovered that those who wrote a compassionate paragraph to themselves about a personal flaw felt more self-compassion afterward.

What is self-compassion in simple words?

Self-compassion is treating yourself with kindness during difficult times, just as you would comfort a friend. It means accepting your struggles without harsh judgment and reminding yourself that everyone faces challenges. Self-compassion cultivates understanding, patience, and support for yourself.

“Painful feelings are, by their very nature, temporary. They will weaken over time as long as we don’t prolong or amplify them through resistance or avoidance. The only way to eventually free ourselves from debilitating pain, therefore, is to be with it as it is. The only way out is through.” — Kristin Neff Creator of the Self-compassion Scales, Author of “ Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself “

Final Words

A self-compassion letter gives you the understanding, kindness, and support you need to navigate difficult emotions and experiences.

Write one today.

What Self-Kindness Really Means? How To Have More of It?

Author Bio: Researched and reviewed by Sandip Roy — a medical doctor, psychology writer, and happiness researcher, who writes on mental well-being, happiness, positive psychology, and philosophy (especially Stoicism ).

• Our Happiness Story !

√ If you liked it, please spread the word .

About Author/Editor

Dr. Sandip Roy is a medical doctor and psychology writer, with a unique focus on mental well-being, positive psychology, narcissism, and Stoicism. His warm-hearted expertise has helped many mental abuse survivors find happiness again. Co-author of 'Critique of Positive Psychology and Positive Interventions' . Find him on LinkedIn .

*Our site is reader-supported. When you buy through our links, we earn a tiny percentage, at no extra cost to you. See Disclosure for details.

When it comes to mental well-being, you don't have to do it alone. Going to therapy to feel better is a positive choice. Therapists can help you work through your trauma triggers and emotional patterns.

Ep. 153: A Self-Compassion Letter

Welcome back to another episode of Your Anxiety Toolkit. Recently we have talked a lot about self-compassion. If you go back to episodes 134, 146, and 147, you will see self-compassion mentioned a lot. Today we are going to expand on that discussion by learning how to write ourselves a self-compassion letter.

I have actually been doing this with my clients for years and it really just involves putting your self-compassion into words which can actually be so helpful.

There are several steps in writing your self-compassion letter. The first step is to show awareness of your struggle. You might say “I see that you are having a hard time.” Whatever it is, just bring it to your awareness and write it down.

The second step is bringing in some words of unconditional love. No matter how much you are suffering, you still get to be loved and cared for.

The third step is to show yourself some empathy for the distress you are in. You might say “I see you. I see the pain you are going through. I can relate to that.”

The fourth step is recognizing your common humanity. In your letter, you want to bring in the common humanity of your struggle. You could say “Everybody knows what it is like to have anxiety . I am definitely not alone.”

Next you want to normalize the fact that when we suffer we all want to engage in safety behaviors. A safety behavior is anything you may do to try and take away your fear, or shame, or sadness. Safety behaviors usually have unintended consequences and they usually end up causing more problems. Instead you would want to explore some more helpful solutions. You are going to look at the situation and say “How might I help myself?”

The last step is to say something really, really kind to yourself and finally you are going to read your self-compassion letter aloud.

Below is an example of my own self-compassion letter.

Kimberley, my dear one. It’s okay that I’m having a hard time right now. I feel afraid and I really just want to jump out of my skin. This is really a difficult time for me. Now, what I am feeling is not wrong. I’m doing the best I can with what I have at this moment. My suffering, this discomfort I feel, it deserves to be met with kindness and tenderness. I deserve that. I am worthy of this kindness and tenderness I’m giving myself. And I wish for myself to have some peace of mind. I know it’s a hard time, but I know I will find peace.

Now I’m going to find this peace mostly by doing what I’m doing right now, which is changing the way I respond to my suffering. Every single pain that shows up inside me, I’m going to meet with kindness and I’m going to recognize that each moment of suffering is worthy of self-compassion.

I’m strong and I can face fear and I can hold space for my emotions, no matter how hard it is. I deserve to be a safe place for fear, as it rises and falls in my body. I am my best ally and I have everything I need right here inside me to get through these hard times.

Now I promise to be there for myself when things get hard. I’m sending you my love.

Now Kimberley, go gently into this moment, my darling.

ERP School, BFRB School, and Mindfulness School for OCD are all now open for purchase. If you feel you would benefit, please go to cbtschool.com

- August 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

818-452-3510

CALABASAS OFFICE 23801 Calabasas Rd, Suite 2036 Calabasas CA 91302

832-559-2622

(832) 299-5686

February 21, 2022

Compassionate Letter Writing

Written by Rachel Eddins

Posted in Tools & Exercises and with tags: journal exercises , self-compassion

Learning self-compassion is a key skill to overcoming anxiety , depression , negative self-talk , and feelings of shame . This exercise, compassionate letter writing , can help you deal with negative life events and things about yourself that you may be struggling with.

Writing to yourself from your compassionate self can help you realize that you are only human and that everyone has something about themself that they aren’t happy with. It can also help you see more clearly constructive changes that you may be able to make to help you feel happier and healthier and even help you judge yourself less.

Compassionate Letter Writing From the Perspective of a Compassionate Other

The idea of compassionate letter writing is to help you refocus your thoughts and feelings on being supportive, helpful, and caring of yourself. Practicing doing this can help you access an aspect of yourself that can help tone down more negative feelings and thoughts .

Self-compassion can be cultivated in many ways.

Research has shown that writing a letter to yourself from the perspective of a compassionate other can help increase self-compassion and improve well-being.

This tool was adapted from Kristen Neff’s self-compassion exercise called Exploring Self- Compassion Through Writing.

Choose an aspect of yourself or your life that you dislike and criticize. It can be something that makes you feel ashamed, unworthy, inadequate, or self-conscious. Examples may include appearance, career, relationships, health, and others.

- Write in detail about how this perceived inadequacy makes you feel.

- What thoughts, images, emotions, or stories arise when you think about it?

Now, imagine someone who is unconditionally loving, accepting, and supportive.

Gently and lovingly, this friend sees your strengths and opportunities for growth, including the negative aspects of you. The friend accepts and forgives , embracing you kindly just as you are.

- Now write a letter to yourself from the perspective of this kind friend.

- What does this friend say to you?

- How is compassion demonstrated?

- How does this friend encourage and support you in taking steps to change?

Let the words flow from you: do not think too hard about phrasing or structure. Just write from the perspective of deep kindness, understanding, and non-judgmental acceptance.

After fully drafting the letter, put it aside for at least fifteen minutes or more if you wish.

- When some time has passed, return to the letter and reread it.

- Let the words fully sink in.

- Feel the encouragement, support, compassion, and acceptance, and let every positive word rush into you.

Whenever you are feeling down, review the letter about this aspect of yourself that you feel is not favorable. Providing self-acceptance and self-support is the first step to change.

You can also apply this exercise to aspects of your body – writing the letter from your body to yourself.

Or try this body acceptance exercise.

Compassionate Letter Writing from Your Caring Self

In this exercise, you will focus on using. your own voice to provide care and kindness to yourself. Think again about an aspect of yourself or your life that you dislike and criticize as you did in step 1 above.

Next, try imagining the last time you felt deep kindness and care for someone else.

To start your letter, try to feel that part of you that can be kind and understanding of others; and how you would be if caring for someone you like.

- Consider your general manner, facial expressions, voice tone, and feelings that come with your caring self.

- Think about that part of you as the type of self you would like to be.

- Think about the qualities you would like your compassionate self to have. It does not matter if you feel you are like this – but focus on the ideal you would like to be.

- Spend a few moments really thinking about this and trying to feel in contact with that ‘kind’ part of you.

As you write your letter, try to allow yourself to have understanding and acceptance for your distress. For example, your letter might start with “I am sad you feel distressed; your distress is understandable because…….”

Note the reasons, realizing your distress makes sense. Then perhaps you could continue your letter with… “I would like you to know that…” (e.g., your letter might point out that as we become depressed, our depression can come with a powerful set of thoughts and feelings – so how you see things right now may be the depression view on things).

Given this, we can try and ‘step to the side of the depression’ and write and focus on how best to cope , and what is helpful.

More Ideas for Compassionate Letter Writing

There are a number of ideas that you might consider in your letter. Do not feel you have to cover them all. In fact, you might want to try different things in different compassionate letters to yourself.

With all of these ideas, although it can be difficult, try to avoid telling yourself what you should or should not think, feel or do. There is no right or wrong, it is the process of trying to think in a different way that is important.

Standing Back:

Once you have acknowledged your distress and not blamed yourself for it, it is useful if your letter can help you stand back from the distress of your situation for a moment. If you could do that, what would be helpful for you to focus on and attend to?

For example, you might think about how you would feel about the situation in a couple of days, weeks, or months, or you might recall that the depression can lift at certain times and remember how you feel then.

How have you coped in the past?

It can be helpful to recall in your letter and bring to your attention, the times that you have coped with difficulties before ; bring those to mind. If there are any tendencies to dismiss them, note them, but try to hold your focus on your letter. Your letter can focus on your efforts and on what you are able to do.

Your compassionate side might gently help you see things in a less black and white way. Your compassionate side is never condemning and will help you reduce self-blaming.

Explore the balanced view through compassion.

Remember your compassionate side will help you with kindness and understanding.

Here are some examples: If someone has shunned you and you are upset by that, your compassionate side will help you recognize your upset but also those thoughts such as ‘the person doesn’t like me, or that I am therefore unlikeable,’ may be very unfair. Perhaps a more balanced view would be the person who shunned you can do this to others and has difficulties of their own; your compassionate side can remind you that you have other friends who don’t treat you this way.

As another example, if you have forgotten to do something or have made a mistake and are very frustrated and you are cross with yourself, your compassionate side will understand your frustration and anger but help you see that the mistake was a genuine mistake and is not evidence of being stupid or useless. It will help you think about what is the most compassionate and helpful thing to do in these circumstances.

Not alone :

When we feel distressed we can often feel that we are different in some way. However, rather than feeling alone and ashamed remember many others can feel depressed with negative thoughts about themselves, the world, or their future. In fact, 1 in 20, or more, of us can be depressed at any one time, so the depression is very sad but is far from uncommon. Your depression is not a personal weakness, inadequacy, badness, or failure.

Self-criticism :

If you are feeling down, disappointed, or are being harsh on yourself, note in your letter that self-criticism is often triggered by disappointment (e.g., making a mistake or not looking like we would like to), loss (e.g., of hoped for love) or fear (e.g., of criticism and/or rejection).

Maybe being self-critical is a way you have learned to cope with these things or take your frustration out on yourself, but this is not a kind or supportive thing to do. Understandable perhaps, but it does not help us deal with the disappointment, loss or fear. So we need to acknowledge and be understanding and compassionate about the disappointment, loss or fear. Allow yourself to be sensitive to those feelings.

Compassionate behavior:

It is useful to think about what might be the compassionate thing to do at this moment or at some time ahead – how might your compassionate part help you do those things? So in your letter, you may want to think about how you can bring compassion into action in your life.

If there are things you are avoiding or finding difficult to do, write down some small steps to move you forward. Try to write down steps and ideas that encourage you and support you to do the things that you might find difficult. If you are unsure what to do, maybe try to brainstorm as many options as you can and think about which ones appeal to you. Could you ask others for help?

If you are in a dilemma about something, focus on the gentle compassionate voice inside you and write down the different sides of the dilemma. Note that dilemmas are often difficult, and at times there are hard choices to be made. Therefore, these may take time to work through. Talking through with others might be a helpful thing to do. Acceptance of the benefits and losses of a decision can take time.

Compassion for feelings:

Your compassionate side will have compassion for your feelings. If you are having powerful feelings of frustration, anger or anxiety, then compassionately recognize these. Negative emotions are part of being human and can become more powerful in depression or when we are distressed but they do not make you a bad person – just a human being trying to cope with difficult feelings.

We can learn to work with these feelings as part of our ‘humanness’ without blaming or condemning ourselves for them. Your compassionate mind will remind you that we often don’t choose to feel negatively and these feelings can come quite quickly. In this sense it is ‘not our fault’, although we can learn how to work with these difficult feelings and take responsibility.

Loss of positive feelings:

If you are feeling bad because you have lost positive feelings then we can be compassionate to this loss – it is very sad to lose positive feelings. Sometimes we lose loving feelings because a relationship has run its course, or we are just exhausted, or depression can block positive emotion systems .

As we recover from the depression these positive systems can return. Your compassionate letter can help you see this without self blaming.

What is helpful:

Your compassionate letter will be a way of practicing how to really focus on things that you feel help you. If thoughts come to mind that make you feel worse, then notice them, let them go and refocus on what might be helpful – remember there are no ‘I shoulds’.

Now try to focus on the feelings of warmth and genuine wish to help in the letter as you write it. Spend time breathing gently and really try, as best you can, to let feelings of warmth be there for you. When you have written your letter, read it through slowly, with as much warmth as you can muster. If you were writing to somebody else would you feel your letter is kind and helpful? Could you change anything to make it more warm and helpful?

Find other self-compassion journal exercises and meditations here and here .

Take our Self-Compassion Quiz and find out.

Continue Practicing Compassionate Letter Writing

Remember that this is an exercise that might seem difficult to do at times but with practice you are exercising a part of your mind that can be developed to be helpful to you. Some people find that they can rework their letters the next day so they can think through things in a different way. The key of compassionate letter writing is the desire and effort of becoming inwardly gentle, compassionate and self-supportive. The benefits of this work may not be immediate but like ‘exercising to get fit’ can emerge over time with continued practice.

Sometimes people find that even though they are depressed they would very much like to develop a sense of self that can be wise and compassionate to both themselves and others. You can practice thinking about how, each day, you can become more and more as you wish to be. As in all things there will be good times and not so good.

Spend time imagining your postures and facial expressions, thoughts and feelings that go with being compassionate and practice creating these inside you. This means being open with our difficulties and distress, rather than just trying to get rid of them .

Source: Professor Paul Gilbert PhD, FBPsS, OBE

For additional help learning self-compassion contact us at 832-559-2622. We will help you get started with one of our Houston , Montrose , or Sugar Land therapists .

Give our best tips, tools, and tactics for living the life of your dreams.

" * " indicates required fields

Take our emotion regulation quiz and find out.

Grounding & Self Soothing Get instant access to your free ebook.

Learn skills to regulate your emotions.

Register for an upcoming free webinar led by a licensed clinician on a mental wellness topic.

Feel better and improve your emotional health — Sign up for our inspirational self-help articles and guides.

Blog Categories

Need help with personal development.

CALL US 832-559-2622

TEXT US 832-699-5001

Related Resources

Get a Free Email eCourse Select as many as you want.

Download a Free eBook Select as many as you want.

Exploring Different Therapy Types: CBT, EMDR, DBT and More

15 Ways to Speak So Your Child Will Listen

How to Practice Self Compassion: Exercises for Self Love & Appreciation

About eddins counseling group.

Our therapists are committed to helping you feel better and find solutions that will work for you. We provide compassionate care to address the emotional, career, and relationship needs of children, teens, adults, families, and couples.

Therapy services are offered in person throughout Houston and Sugar Land, TX . Therapy is also offered online in multiple states throughout the US.

TAKE THE NEXT STEP

GET SELF HELP RESOURCES

TAKE A FREE SELF-HELP TEST

The self-tests and quizzes are tools to help you with mental, emotional, career and relationship wellness.

BOOK AN APPOINTMENT

Schedule an appointment with a Counselor. Scheduling is flexible and convenient.

AS FEATURED IN

OUR LOCATIONS

HEIGHTS LOCATION

5225 Katy Fwy, Suite 103, Houston, TX 77007

MONTROSE LOCATION

802 West Alabama St., Houston, TX 77006

SUGAR LAND LOCATION

12930 Dairy Ashford Rd., Suite 103, Sugar Land, TX 77478

ONLINE THERAPY AVAILABLE IN

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Self-compassion 8a: writing a compassionate letter.

“In this exercise we are going to write about difficulties, but from the perspective of the compassionate part of ourselves.”

Dear David, I know you are feeling really anxious right now, that you would really enjoy having your needs to be understood and accepted met.

It's understandable that you're feeling that way, since you worked really hard to write that email to your friend, to disagree in a really polite way, and you were hoping that it would become a positive conversation. Instead, your friend decided to stop emailing you for a while.

I want you to remember, though, that your brain is designed to help you care about relationships. You're feeling anxious because you also have a need for connection and community, and your brain is reminding you of that. That reaction is natural and important, and you can use it to help you keep making decisions that meet your needs.

In fact, would you be willing to go spend some time connecting with a friend sometime soon? It's been a while since you played guitar with X – would that be a good place to start?

Exercise 3: Exploring self-compassion through writing

Part one: which imperfections make you feel inadequate.

Everybody has things about themselves that they don’t like, that cause them to feel shame, to feel insecure, or not “good enough.” It is the human condition to be imperfect, and feelings of failure and inadequacy are part of the experience of living a human life. Try writing about an issue you have that tends to make you feel inadequate or bad about yourself (physical appearance, work or relationship issues…) What emotions come up for you when you think about this aspect of yourself? Try to just feel your emotions exactly as they are – no more, no less – and then write about them.

Part Two: Write a letter to yourself from the perspective of an unconditionally loving imaginary friend

Now think about an imaginary friend who is unconditionally loving, accepting, kind and compassionate. Imagine that this friend can see all your strengths and all your weaknesses, including the aspect of yourself you have just been writing about. Reflect upon what this friend feels towards you, and how you are loved and accepted exactly as you are, with all your very human imperfections. This friend recognizes the limits of human nature, and is kind and forgiving towards you. In his/her great wisdom this friend understands your life history and the millions of things that have happened in your life to create you as you are in this moment. Your particular inadequacy is connected to so many things you didn’t necessarily choose: your genes, your family history, life circumstances – things that were outside of your control.

Write a letter to yourself from the perspective of this imaginary friend – focusing on the perceived inadequacy you tend to judge yourself for. What would this friend say to you about your “flaw” from the perspective of unlimited compassion? How would this friend convey the deep compassion he/she feels for you, especially for the pain you feel when you judge yourself so harshly? What would this friend write in order to remind you that you are only human, that all people have both strengths and weaknesses? And if you think this friend would suggest possible changes you should make, how would these suggestions embody feelings of unconditional understanding and compassion? As you write to yourself from the perspective of this imaginary friend, try to infuse your letter with a strong sense of his/her acceptance, kindness, caring, and desire for your health and happiness.

Part Three: Feel the compassion as it soothes and comforts you

After writing the letter, put it down for a little while. Then come back and read it again, really letting the words sink in. Feel the compassion as it pours into you, soothing and comforting you like a cool breeze on a hot day. Love, connection and acceptance are your birthright. To claim them you need only look within yourself.

Other Exercises

Exercise 8: Taking care of the caregiver

Exercise 7: Identifying what we really want

Exercise 6: Self-Compassion Journal

Subscribe to receive free regular self-compassion info and practices from dr. kristin neff.

- About Self-Compassion

- About Kristin

COPYRIGHT © 2024 SELF-COMPASSION LLC, KRISTIN NEFF, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Terms of Use/Privacy Policy , Disclaimer

The Self-Compassion Community

Scholarship Application Form

One of the kindest things you can do for another is to give them the gift of self-compassion.

Community for Deepening Practice

Befriend Yourself

Customizing Loving-Kindness Phrases

Today, we wrapped up our session on MSC Session 3, Practicing Loving-Kindness. After reviewing the prior month’s work on deepening understanding of mindfulness, compassion, and loving kindness, we invited our hearts’ answers to these questions: “What do I need?” and “What do I long to hear?” As a way to continue the process of cultivating goodwill […]

A Self-Compassionate Letter as You Begin Your Journey

The Invitation:

Over the past three weeks, we’ve revisited familiar MSC territory from MSC Session 1. This week’s invitation is to bring awareness to what you’ve discovered during the last three weeks of preparatory work to help you write a compassionate letter for yourself. This letter will live with your Roadmap and be a companion during your journey; you may wish to pull it out anytime you feel your energy lagging, your commitment wavering, or your purpose coming into question. The reason for the exploration and the compassionate letter is to remember that this is a journey and to move away as best we can from where we think we “should be” to lovingly be with where we are.

Your journal and a pen you love to write with. (We especially encourage you to handwrite this letter.)

The Process:

- To begin, simply free-write anything that’s on your mind about the CDP course . Allow it all to emerge. You might give voice to uncertainty, fear, excitement, curiosity, or anything in between. Allow enough time and space for the quietest thoughts to arise, then set them free in your journal.

- Once you feel you’ve said everything you need to say, go back over your writing and underline any words or phrases which emerge and seem like they need a kind response . Perhaps a fear expressed, or ambivalence, or an element of self-doubt.

- Next, please write a self-compassionate letter in response to any of the underlined words/phrases from Step 2. Practice using your self-compassionate voice as you write . You might even begin your letter with a term of endearment, remembering to bring the same kindness to your letter as you would to a good friend. IF you find that you have difficulty summoning a self-compassionate voice, we invite you to write your letter from the perspective of a being who wishes the very best for you: a pet, a friend, a mentor, or another loved one.

- What words do you need to hear as you venture out on this journey?

- Knowing that all experiences shift through periods of difficulty and ease, open and closing, what might support you personally along the way?

- From this early leg of the journey, what words will you say to yourself when you’re thinking about quitting?

- If you have identified misgivings or hindrances to self-compassion, how might you bring care and kindness to these aspects of your experience? If you have identified the pain of one of more of the myths of self compassion, how might your respond to yourself lovingly about these?

- How we can attend to ourselves lovingly in these ways? Physical, mental, emotional, relational, and spiritual?

- What resources can you draw upon during your time in the program that will help you stay committed to taking care of yourself?

- Once you’ve finished your letter, we encourage you to keep it somewhere accessible so that if you wish, you may draw upon the strength of your own words in the future.

- As you read your letter to yourself you may like to remember soothing touch, the half smile, and pay attention to the tone of your voice as you read.

One step further…

If you wish, you may choose to submit a photo or a scan of your self-compassionate letter to one of the teachers via email, and when the moment is right, we will print it out and mail a physical copy back to you sometime during the next several months as a gentle and reminder of your own voice of support.

The Reflection:

As you write, be present to any joy or excitement that emerges.

If fear or doubt emerges, is there one small, tender step you can take to soothe yourself?

Now that you’ve written this self-compassionate letter, can you think of any specific actions you can take to set the stage for a truly deepening experience in your life?

If you wish, feel free to share your explorations on the Discussion board.

© 2018 Aimee Eckhardt. Please do not duplicate without written permission.

This site uses functional cookies and external scripts to improve your experience.

Privacy settings

Privacy Settings

This site uses functional cookies and external scripts to improve your experience. Which cookies and scripts are used and how they impact your visit is specified on the left. You may change your settings at any time. Your choices will not impact your visit. You may read our full privacy policy here:

Privacy Policy .

NOTE: These settings will only apply to the browser and device you are currently using.

Cookie policy

This website uses cookies to analyze traffic. We also share information about your use of our site with analytics partners who may combine it with other information that you’ve provided to them or that they’ve collected from your use of their services. You consent to our cookies if you continue to use our website.

Develop Empathy for Others and Self-Compassion for Yourself

Important strategies to help you develop both..

Posted June 23, 2020

This is Part 4 of a series of 5. To read Part 1, click here.

When it comes to empathy, generally speaking, there tend to be two types of people—those who have difficulty empathizing with others, and those who “over empathize” by focusing too much attention on the needs and feelings of others and not enough on their own. Those who have difficulty empathizing with others are prone to abusive behavior and those who “over empathize” tend to be easily victimized.

For some, one of the after-effects of having been neglected or abused as a child is that their ability to have empathy for others is compromised. Because they likely experienced little empathy from their parents, they may not even know what empathy looks and feels like. Research, including that conducted by the APA Presidential Task Force, consistently finds that lack of empathy is associated with a tendency toward family violence. Parents who are unable to empathize with their children (put themselves in their children’s place) are more harsh and demanding than parents who have empathy.

If you recognize that you have difficulty empathizing with others the following exercise will strengthen your empathetic abilities by helping you imagine what someone else is feeling.

Exercise: Imaginary letters

In this exercise, you will write several imaginary letters. These letters will be to yourself, from your partner and children.

- One by one imagine what your partner and each of your children would like to say to you about the way they feel when you are at your worst. For example, put yourself in your partner’s place when you lose your temper and “go off” on him or her. Write down all the things you imagine he or she might be feeling (angry, hurt, depressed ) and how you imagine it makes your partner feel about himself or herself (insecure, defeated). If you have children, write a letter describing how you imagine each child feels when you are too busy to spend time with him, when you become impatient, or when you are too demanding. For example: “I hate it that you expect so much of me. You make me feel like I’m stupid or lazy. I’m not perfect. When you expect me to be I just feel like giving up.”

- You may choose to write all your letters at one sitting or to spread them out over time, possibly writing one letter a day or even one letter a week.

- When you have completed all your letters begin reading them to yourself, one by one.

- Imagine that each letter was actually written by this person and allow your heart to open to their words. When it becomes difficult to take in, take a deep breath and remember your commitment to yourself to break the cycle. Try not to become defensive or to slip into denial .

Self-Compassion

As important as it is to develop empathy for others, it is equally important to learn to provide self-compassion for yourself. While compassion is the ability to feel and connect with the suffering of another human being, self-compassion is the ability to feel and connect with one’s own suffering. More specifically for our purposes, self-compassion is the act of extending compassion to one’s self in instances of perceived inadequacy, failure, or general suffering.

Kristin Neff is the leading researcher in the growing field of self-compassion. In her ground-breaking book, she defines self-compassion as “being open to and moved by one’s own suffering, experiencing feelings of caring and kindness toward oneself, taking an understanding, nonjudgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one’s experience is part of the common human experience.”

Those who were abused or neglected in childhood tend to blame themselves for the abuse or neglect they suffered. In addition, they were likely deeply shamed by their abusive or neglectful parents and thus feel “full of shame.” Because of this, some build up a defensive wall to protect themselves from experiencing any further shame. This wall cuts them off from others, especially from having empathy for others.

By practicing self-compassion, an abusive person can slowly begin to understand why he or she took on an abusive pattern. He learns to make the all-important connection between the abuse he experienced and his tendency to become abusive. He will become more able to have compassion for the small neglected or abused child he was and to use that self-compassion to begin nurturing himself in actions and in words. Once he is healed of debilitating shame through self-compassion he can afford to lower the wall of defensiveness that protects him from further shaming and by doing so, free himself to begin to truly connect with others—and to eventually have compassion for others—which in turn, will make him far less likely to re-offend.

Through self-compassion, an abusive person can learn to forgive himself for his abusive behavior and to connect with how badly he truly feels for what he has done to others. As he gradually begins to feel more forgiving and ultimately more loving toward himself the self-hatred and shame he has been carrying his entire life begins to melt away. This can be a major step toward breaking the cycle of abuse because child abuse and partner abuse are often projections of the shame and self-hatred we are carrying.

On the other hand, some victims of neglect and abuse in childhood react differently to having been abused. They also suffer from tremendous shame and self-hatred but instead of putting up a wall to protect themselves from further shame, as those who become abusive can do, this shame causes them to believe they do not deserve to be treated with respect, or that they do not deserve to be loved. Therefore, when someone mistreats them, they often feel they deserved it.

These victims of childhood neglect or abuse tend to put up with unacceptable behavior and are unable to defend themselves. Without self-compassion people tend to judge themselves harshly when they make a mistake or when they don’t meet their own unreasonable expectations or the high expectations of others. They begin to chastise themselves and beat themselves up for not being perfect. And without self-compassion, they continue to blame themselves for the horrible ways that people treat them. Most important, without self-compassion they cannot even acknowledge the pain at having been abused in the past. Without this important acknowledgment, there can be no healing.

Whether you are afraid of becoming abusive or have already begun to abuse, afraid of being victimized, or have already established a pattern of being a victim, practicing self-compassion can help you break the cycle of abuse. Due to what we now know about the neural plasticity of the brain—the capacity of our brains to grow new neurons and new synaptic connections—we can proactively repair (and re-pair) the old shame memory with new experiences of self-empathy and self-compassion.

How to begin to practice self-compassion

- Make the connection between your current behavior and your past experience with abuse or neglect.

- Say to yourself, either out loud or silently to yourself, “It is understandable that I would behave in this way due to the abuse/neglect I have suffered.” This is not an excuse, just an acknowledgment of the facts.

By learning to practice self-compassion you will rid yourself of the belief that you are worthless, defective, bad, or unlovable. Instead of trying to ignore these false yet powerful beliefs, trying to convince yourself otherwise by puffing yourself up, overachieving, or becoming a perfectionist , your shame needs to be actively approached, recognized, validated, and understood.

Exercise: Becoming Compassionate Toward Yourself

- Think about the most compassionate person you have known—someone who has been kind, understanding, and supportive of you. It may have been a teacher, a friend, or perhaps a friend’s parent. Think about how this person conveyed their compassion toward you and how you felt in this person’s presence.

- If you can’t think of someone in your life who has been compassionate toward you, think of a compassionate public figure or even a fictional character from a book, film, or television.

- Now imagine that you have the ability to become as compassionate toward yourself as this person has been toward you (or you imagine this person would be toward you). How would you treat yourself? What kinds of words would you use when you talk to yourself?

This is the goal of self-compassion—to treat yourself in the same way the most compassionate person you know would treat you—to talk to yourself in the same loving, kind, and supportive ways that this compassionate person would talk to you.

Neff, Kristin. (2015). Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. New York: William Morrow.

Engel, Beverly (2015). It Wasn't Your Fault: Freeing Yourself from the Shame of Child Abuse with the Power of Self Compassion.

Oakland: New Harbinger.

Beverly Engel has been a therapist specializing in abuse issues for the past 35 years. Beverly is the author of numerous self-help books, including her latest books: Freedom at Last: Healing the Shame of Childhood Sexual Abuse; Escaping Emotional Abuse and It Wasn’t Your Fault .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A Brief Self-Compassionate Letter-Writing Intervention for Individuals with High Shame

Michaela b. swee.

1 Temple University, Philadelphia, USA

Keith Klein

2 Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, USA

Susan Murray

Richard g. heimberg, associated data.

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Over the last decade, the mental health of undergraduate students has been of increasing concern and the prevalence of psychological disorders among this population has reached an unprecedented high. Compassion-based interventions have been used to treat shame and self-criticism, both of which are common experiences among undergraduate students and transdiagnostic vulnerability factors for an array of psychological disorders. This randomized controlled study examined the utility of a brief online self-compassionate letter-writing intervention for undergraduate students with high shame.

Participants were 68 undergraduates who scored in the upper quartile on shame. Individuals were randomly assigned to a 16-day self-compassionate letter-writing intervention ( n = 29) or a waitlist control group ( n = 39). Participants completed baseline, post-assessment, and one-month follow-up measures.

Participants who practiced self-compassionate letter writing evidenced medium-to-large reductions in global shame, external shame, self-criticism, and general anxiety at post-assessment, and gains were sustained at follow-up. Additionally, there were trend-level effects for increases in self-compassion and decreases in depression for those who participated in the intervention.

Conclusions

This study examined the efficacy of self-compassionate letter-writing as a stand-alone intervention for undergraduate students with high shame. This brief, easily accessible, and self-administered practice may be beneficial for a host of internalizing symptoms in this population and may support university counseling centers as they navigate high demand for mental health services.

The prevalence of mental health disorders among undergraduate students increased from 22 to 36% between 2007 and 2017 (Lipson et al., 2018 ). Thirty-five percent of first-year college students worldwide met criteria for at least one lifetime psychological disorder (Auerbach et al., 2018 ). In 2020, 35% and 39% of undergraduates met criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, respectively, and suicide is identified as one of the leading causes of death in this population (Chirikov et al., 2020 ; Turner et al., 2013 ). The proportion of students seeking mental health services also increased substantially, from 19 to 34%, between 2007 and 2017 (Lipson et al., 2018 ). The COVID-19 global pandemic has only exacerbated mental health concerns among university students, increasing loneliness and isolation and significantly affecting quality of life (Chirikov et al., 2020 ; Lederer et al., 2021 ). Thus, there is an urgent need to consider additional resources and interventions for addressing and improving mental health in this population.

Research has shown that 25% of undergraduates endorse clinical levels of shame (Andrews et al., 2002 ; Cook, 1996 ). Shame is a highly painful emotion reflecting negative judgment, disapproval, or rejection of core aspects of the self (Cândea & Szentágotai-Tăta, 2018 ). Shame can be internal , in which the self is both the judge and the object of judgment, or external , in which the judge is the other as seen through one’s own eyes (Gilbert, 2000 ; Matos et al., 2013 ). Elevated levels of shame have been observed across numerous psychological disorders, including anxiety disorders (e.g., Fergus et al., 2010 ), depression (e.g., Mills et al., 2015 ), post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g., Feiring et al., 2002 ), eating disorders (e.g., Kelly & Carter, 2013 ), and personality disorders (e.g., Ritter et al., 2013 ). Some data have also suggested that shame is related to poorer psychotherapy outcome (Wiltink et al., 2016 ). The impairing, transdiagnostic nature of shame makes it an important target for intervention.

Shame and self-compassion have evidenced a significant, inverse relationship and fostering self-compassion has been associated with decreased shame (Kelly & Waring, 2018 ; Matos et al., 2017 ; Reilly et al., 2014 ; Woods & Proeve, 2014 ). Compassion is understood as a sensitivity to the suffering of self and others, with a deep commitment to try to relieve it (Lama, 2001 ). Compassion has three flows: compassion flowing out to others, compassion flowing in from others, and self-compassion (i.e., compassion flowing in from the self). Self-compassion is considered to be an antidote for shame, as it involves the courage to attune to one’s own suffering accompanied by the wisdom to act in ways that may be helpful in moments of pain (Gilbert, 2010 ). Directing compassion toward oneself in moments of pain or struggle provides an opportunity for individuals to acknowledge and validate their experience, rather than criticize or punish themselves, which can prolong suffering. Self-compassion, as an alternative to self-judgment or self-disparagement, allows individuals the space to consider what might be helpful during a period of struggle, which is an adaptive alternative to rumination and self-criticism.

Two well-known approaches to foster greater self-compassion are Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert, 2010 , 2014 ) and Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC; Neff, 2003a ). CFT focuses on helping individuals learn to regulate their emotions, establish safeness within themselves, and increase the warmth, care, and kindness with which they relate to themselves (Gilbert, 2010 ). MSC helps individuals foster greater self-compassion through mindfulness, self-kindness, and the concept of common humanity, which highlights the ways in which human beings can relate to one another through the common experience of pain (Neff, 2003a ). Established mindfulness, self-compassion, and acceptance-based interventions also focus on factors including the mind–body relationship, fostering non-judgment and acceptance of experience, and affect regulation through self-soothing (for a meta-analysis of self-compassion-focused interventions, see Ferrari et al., 2019 ).

Interventions that focus on fostering self-compassion demonstrated increases in self-compassion and compassion for others, self-reassurance, and self-soothing, as well as reductions in shame, self-criticism, anxiety, depression, stress, perceived inferiority, and submissive behavior (Cuppage et al., 2018 ; Gilbert & Procter, 2006 ; Judge et al., 2012 ; Matos et al., 2017 ). Importantly, some evidence suggested that these interventions may have lasting effects (Cuppage et al., 2018 ). One exercise that can be used to enhance self-compassion is self-compassionate writing, and existing studies examining the efficacy of short-term self-compassionate writing practice showed promising results (Johnson & O’Brien, 2013 ; Kelly & Waring, 2018 ; Stern & Engeln, 2018 ; Wong & Mak, 2016 ). Compared to control conditions, self-compassionate writing was associated with increased body satisfaction and positive affect in undergraduate women (Stern & Engeln, 2018 ), decreases in bodily shame and increases in self-compassion in women with anorexia nervosa (Kelly & Waring, 2018 ), and lower levels of negative affect and state shame in university students (Johnson & O’Brien, 2013 ). Given that only 25% of undergraduate students indicated that they would seek treatment for an emotional problem, with the majority of students stating that they would prefer to address such difficulties on their own (Ebert et al., 2019 ), it is crucial to identify mental health interventions that are not only effective but that students feel comfortable utilizing. Self-compassionate letter writing can be done alone and practiced when needed and thus may appeal to students, particularly for those whose shame interferes with seeking treatment.

Given the importance of finding additional ways to improve mental health among undergraduate students, the current study sought to examine the helpfulness of a 2-week self-compassionate letter-writing intervention for undergraduate students with high levels of shame. In addition to examining effects of the intervention following the two-week self-compassionate practice, we included a one-month follow-up assessment to determine whether any therapeutic effects would be maintained following cessation of the intervention, which would support initial findings of longer-term gains (Cuppage et al., 2018 ). We hypothesized that those who practiced self-compassionate letter writing would experience greater decreases in global and external shame, self-criticism, general anxiety, and depression, and greater increases in self-compassion than those in the waitlist control group and that these gains would be maintained at follow-up.

Participants

A power analysis for a repeated-measures between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) design conducted in G*Power (Faul et al., 2009 ) yielded a total target sample size of 62 to detect a medium effect size with 80% power. Given that there is no gold standard power analysis method for multilevel modeling, and previous studies demonstrated small to medium increases in self-compassion and medium to large reductions in shame in samples of 40–90 (e.g., Johnson & O’Brien, 2013 ; Kelly & Waring, 2018 ), we aimed for a total target enrollment of 60 participants, 30 per group.

The final sample for this study comprised 68 undergraduate students recruited through the university’s online research system, flyers posted around campus, and departmental e-mail listservs. Inclusion criteria were being 18 years of age or older, self-reported English fluency in speaking, reading, and writing, and baseline scores ≥ 65 on the Experience of Shame Scale (ESS; Andrews et al., 2002 ). Though there is no established cut-off score on the ESS to indicate clinically meaningful shame, research in an English-speaking undergraduate sample indicated that the mean ESS score was 55.58 ( SD = 13.95; Andrews et al., 2002 ), suggesting that the 75 th percentile of ESS scores falls at approximately a score of 65, which was used as the minimal cut-off score for the current study.

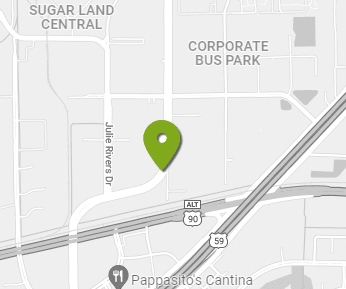

Demographic characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table Table1. 1 . Sixty-eight participants completed the baseline assessment ( n intervention = 29; n control = 39), 50 participants completed the post-intervention assessment ( n intervention = 20; n control = 30), and 32 participants completed the follow-up assessment ( n intervention = 15; n control = 17).

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of sample ( n = 68)

| Intervention Group ( = 29) | Control Group ( = 39) | Statistical Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ( , ) | 20.29 | 2.26 | 20.59 | 3.62 | (65) = -0.39 |

| Female ( , %) | 25 | 86.2 | 30 | 76.9 | χ (1) = 0.93 |

| Gender minority ( , %) | 1 | 3.4 | 3 | 7.7 | χ (1) = 0.54 |

| Sexual orientation minority ( %) | 13 | 44.8 | 17 | 43.6 | χ (1) = 0.004 |

| Racial identity ( ) | χ (3) = 1.09 | ||||

| Black/African American | 2 | 6.9 | 6 | 15.4 | – |

| Asian | 5 | 17.2 | 7 | 17.9 | – |

| White | 17 | 58.6 | 23 | 59.0 | – |

| Other (e.g., mixed race) | 3 | 10.3 | 3 | 7.7 | – |

| Missing or not reported | 2 | 6.9 | – | – | – |

| Ethnicity ( ) | χ (1) = 1.81 | ||||

| Hispanic | 5 | 17.2 | 3 | 7.7 | – |

| Non-Hispanic | 21 | 72.4 | 35 | 89.7 | – |

| Missing or not reported | 3 | 10.3 | 1 | 2.6 | – |

| Concurrent treatment ( , %) | 9 | 31.0 | 18 | 46.2 | χ (1) = 1.59 |

| Change in treatment ( , %) | 3 | 10.3 | 3 | 7.7 | χ (1) = 0.66 |

| Average # letters written | 8.17 | 6.18 | – | – | – |

| ESS | 79.17 | 9.54 | 77.56 | 9.44 | (66) = 0.69 |

| OAS-2 | 18.83 | 7.16 | 18.72 | 5.44 | (66) = 0.07 |

| FSCRS-IS | 23.55 | 6.15 | 22.97 | 6.35 | (66) = 0.38 |

| SCS-SF | 28.66 | 7.71 | 27.95 | 6.75 | (66) = 0.40 |

| PHQ-9 | 13.17 | 6.47 | 13.77 | 5.17 | (66) = -0.42 |

| GAD-7 | 12.72 | 5.04 | 12.05 | 4.49 | (66) = 0.58 |

Gender minority = gender identity other than cisgender; sexual orientation minority = sexual orientation other than heterosexual; concurrent treatment = receiving psychotherapy or psychotropic medication at the time of beginning the study; change in treatment = change in psychotherapy or psychotropic medication over the course of the study; average # letters written = the average number of completed days of the intervention; ESS Experience of Shame Scale, OAS-2 Other As Shamer Scale-2, FSCRS-IS Forms of Self Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale, Inadequate Self Subscale, SCS-SF Self-compassion Scale-Short form, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale. None of the tests were statistically significant

Participants completed baseline measures, and those who were eligible were randomly assigned to the self-compassionate letter-writing condition or a waitlist control group. A CONSORT study flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1 . Randomization was stratified by ESS scores to increase the likelihood that the distribution of shame scores would be equivalent across groups. It should be noted that participants were randomized following a 1:1 ratio from the initiation of the study through February 2020. Due to slower than anticipated recruitment in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we randomized participants in a 2:1 fashion (intervention vs. control group) between March 2020 and January 2021, which was the end of the data collection period. Participants in both groups completed post-assessment measures 16 days following completion of baseline measures as well as a one-month follow-up assessment. Participants assigned to the control group were given the opportunity to engage in the self-compassionate letter-writing practice upon completion of the study. Intervention participants were first directed to an online video that offered brief psychoeducation about self-compassion and the current study. Participants were asked to reserve 30 min per day for this exercise and be in a private space where they could read their letters out loud to themselves. They were then instructed to listen to audio recordings which guided them through imaginal and written exercises to foster compassion for others, including writing a compassionate letter to an imagined other who was experiencing pain or suffering. Starting in the second session, participants were prompted to begin self-compassionate letter writing (they could also continue writing compassionate other-focused letters on an optional basis). They were asked to complete daily self-compassionate letters for the remainder of the study. As compensation, all participants were offered course credit and the opportunity to be entered into a gift card raffle for up to US$150 based on level of participation. The current intervention was inspired by the research of Kelly and Leybman ( 2012 ) and Kelly and Waring ( 2018 ) and draws on Gilbert’s CFT ( 2010 ) as well as Neff and Germer’s MSC ( 2013 ). For further details about the self-compassionate letter-writing intervention, see Table Table2 2 .

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Description of self-compassionate letter-writing intervention

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Days 3–16 |

|---|---|---|

Participants were given an orientation to compassion and its three flows (compassion flowing out to others, compassion flowing in from others, and compassion flowing in from the self: self-compassion). The definition of self-compassion was given, benefits of self-compassion practice were described, and acknowledgment of fears around giving and receiving compassion from others and practicing self-compassion were discussed Participants were asked to identify up to 10 pros and 10 cons to developing self-compassion Introduction to Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise (compassion directed towards another person): Step 1: Participants were asked to imagine that someone they care for is struggling with depression and shame and to notice how it feels to experience compassion for this individual in their body Step 2: Participants were asked to generate 2–3 statements to convey the following sentiments and were given examples of each: 1. Validate this person’s suffering 2. Remind this person that any single moment of suffering is temporary and will pass 3. Express the desire to help and support this individual 4. Remind this person that pain is part of the human condition—all humans experience it Step 3: Participants were then asked to write a free-flowing compassionate letter to the person they were thinking of, using the sentiments generated in Part 2 if helpful. Participants were also offered examples of compassionate letters Step 4: Participants were asked to read the letter to themselves in a warm, caring, and gentle tone of voice | Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise (directed towards another person): Participants were asked to repeat Steps 1, 3, and 4 of the Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise from Day 1 and were reminded of the components of a Compassionate Letter described in Step 2. Next, participants were introduced to a similar Self-Compassionate Letter Writing Exercise that followed the same structure Self-Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise (compassion directed towards oneself): Step 1: Participants were asked to reflect on something in their life around which they were feeling ashamed or self-critical. They were asked to notice any self-judgmental thoughts or unpleasant sensations arising and guided to gently refocus their attention on directing self-compassion toward themselves around their experience Step 2: Participants were asked to generate 2–3 statements to convey the following sentiments about their own experience and were given examples of each: 1. Validate your own suffering 2. Remind yourself that any single moment of suffering is temporary and will pass 3. Express the desire to help and support yourself 4. Remind yourself that pain is part of the human condition—all humans experience it Step 3: Participants were then asked to write a free-flowing self-compassionate letter to themselves, using the sentiments generated in Part 2 if helpful. Participants were also offered examples of self-compassionate letters Step 4: Participants were asked to read the self-compassionate letter to themselves in a warm, caring, and gentle tone of voice | Participants were given the opportunity to do the Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise (i.e., compassionate letter written to another person in pain), but this was optional Participants were asked to complete the Self-Compassionate Letter-Writing Exercise that they learned and practiced during Day 2 |

Participants in the intervention condition were asked to spend 20–30 min per day on the self-compassionate letter-writing task. The intervention described herein was delivered through a series of recorded audio prompts embedded on the website that participants could play and listen to, as well as written prompts and large text boxes in which participants could write their responses to the prompts and their letters

Demographic Characteristics

At baseline, all participants completed a brief measure assessing demographic variables. Participants were also asked to report if they were in therapy or receiving psychiatric treatment at the time of the study. Participants were also asked at the end of their participation whether any change in concurrent treatment had occurred during the study period.

Experience of Shame Scale (ESS )

The ESS is a 25-item measure of global shame that probes characterological, behavioral, and bodily shame. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale based on the past year. Scores on the ESS range from 25–100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of shame. The ESS has shown strong internal consistency (α = 0.92), good 11-week test–retest reliability ( r = 0.88), and strong convergent validity with other measures of shame (Andrews et al., 2002 ). The ESS demonstrated strong internal consistency and scale reliability in our sample at baseline (α = 0.83, ω = 0.79), post-assessment (α = 0.94, ω = 0.94), and follow-up (α = 0.94, ω = 0.94).

The Other as Shamer Scale-2 (OAS-2 )

The OAS-2 is an 8-item version of the original OAS (Goss et al., 1994 ), which measures external shame. The OAS-2 asks individuals to rate how frequently they experience external shame on a 5-point Likert-type scale, such that higher scores indicate greater external shame. The OAS-2 demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.82), as well as a large correlation with the original OAS ( r = 0.91) and a moderate correlation with the ESS ( r = 0.54; Matos et al., 2015 ). The OAS-2 demonstrated strong reliability in our sample at baseline (α = 0.85, ω = 0.85), post-assessment (α = 0.90, ω = 0.90), and follow-up (α = 0.95, ω = 0.95).

Forms of Self Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS )

The FSCRS is comprised of three subscales, one of which is the 9-item self-criticism subscale, Inadequate Self (e.g., “I am easily disappointed with myself”), which was used in this study. Items on the Inadequate Self subscale are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with higher scores indicating higher self-criticism. The Inadequate Self subscale demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.90) as well as good convergent validity with other measures of self-criticism ( r -values = 0.63–0.77; Gilbert et al., 2004 ). The Inadequate Self subscale demonstrated strong internal consistency and reliability in our sample at baseline (α = 0.88, ω = 0.88), post-assessment (α = 0.92. ω = 0.92), and follow-up (α = 0.92, ω = 0.92).

Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF )

The SCS-SF is a 12-item version of the original 26-item SCS (Neff, 2003b ) measuring self-compassion. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion. The SCS-SF has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.87) and is strongly correlated with the original SCS ( r = 0.97; Raes et al., 2011 ). The SCS-SF showed strong internal consistency and reliability in our sample at baseline (α = 0.84, ω = 0.83), post-assessment (α = 0.86, ω = 0.85), and follow-up (α = 0.88, ω = 0.87).

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a 10-item screening tool for depression. Individuals are asked to rate the severity of depressive symptoms occurring over the past two weeks. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.89; Kroenke et al., 2001 ) and scale reliability, which was also true in our sample at baseline (α = 0.83, ω = 0.83), post-assessment (α = 0.92, ω = 0.92), and follow-up (α = 0.91, ω = 0.91).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7 )

The GAD-7 assesses symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Individuals rate their symptoms of general anxiety over the past two weeks on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. The GAD-7 demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.92) and one-week test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.83; Spitzer et al., 2006 ). The GAD-7 demonstrated strong internal consistency and scale reliability in our sample at baseline (α = 0.82, ω = 0.83), post-assessment (α = 0.85, ω = 0.85), and follow-up (α = 0.92, ω = 0.92).

Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were conducted in IBM® SPSS® Statistics, Version 24. Two-tailed independent samples t -tests were conducted to assess differences between the intervention and control groups on continuous demographic variables (e.g., age) and baseline measures. χ 2 tests were conducted to determine whether groups differed on categorical demographic variables.

To examine the influence of potential confounding variables on the effect of time, standardized residual change scores for the baseline-to-post-assessment and the post-assessment-to-follow-up periods were calculated. Standardized residual change scores were selected over raw change scores because they account for variability at baseline and thus are considered superior estimates of change (Tucker et al., 1966 ).

Correlations between standardized residual change scores and baseline demographic characteristics were examined using Pearson’s r and Spearman’s ρ. Additionally, standardized residual change scores for the baseline-to-post-assessment and post-assessment-to-follow-up periods were correlated with the number of letters written in the intervention group to probe for the presence of a possible dose–response effect. Gender was examined as a covariate in the multilevel models. However, gender and other covariates did not affect model outcomes, so they were removed to conserve power in the final analyses.

Primary analyses

Because observations were nested within participants over time, we conducted hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimations in R (R Development Core Team, 2013 ) with the lme4 and lmerTest packages (Bates et al., 2015 ; Kuznetsova et al., 2017 ). HLM using REML is robust to missing data and unequal assessment timepoint intervals across persons (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002 ) and thus provides unbiased estimates in the presence of incomplete data.

Prior to conducting HLM, the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homogeneity of the residuals were assessed. The assumptions of linearity and homogeneity were examined graphically. The normality assumption was examined via standard z -scores of skewness and kurtosis. The standard error covariance structure was compared to compound symmetry and first-order autoregressive covariance structures using estimates of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) statistic (Akaike, 1981 ). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated by dividing the random effect variance by the total variance to determine the proportion of variance explained by between-person differences.

To assess the primary study aims, we examined the impact of the intervention on the six outcome variables. First, an unconditional intercept model was specified with no predictors in the model; Outcome tj = β 00 + ε ti . Next, an unconditional growth model that included time (Timepoint) at the occasion level was estimated; Outcome tj = β 00 + β 01 T i m e p o i n t + ε ti . The final interaction model included time, group, and the group by time interaction as predictors of the level-1 intercept and slope parameters; Outcome tj = β 00 + β 01 T i m e p o i n t + β 02 G r o u p + β 03 T i m e p o i n t G r o u p + μ 01 T i m e p o i n t + ε ti . To better understand the differential effects of the intervention, all significant group by time interactions were probed using simple slope analyses.

Preliminary Analyses

Two-tailed independent samples t -tests revealed no differences between the intervention and control groups on age or any outcome measure at baseline; χ 2 tests revealed no group differences in demographic characteristics (Table (Table1). 1 ). Means and standard deviations for all outcome variables across the three assessment time points, as well as between- and within-group effect sizes, are displayed in Table Table3. 3 . Bivariate correlations are presented in Table Table4 4 .

Raw means and standard deviations of study variables and effect sizes

| Intervention | Control | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline ( = 29) | Post ( = 20) | Follow-up ( = 15) | Baseline ( = 39) | Post ( = 30) | Follow-up ( = 17) | ||||||||

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | ||||||||

| ESS | 79.17 | 9.54 | 63.25 | 15.67 | 66.27 | 13.58 | 77.56 | 9.44 | 74.87 | 14.71 | 73.94 | 17.23 | |

| OAS-2 | 18.83 | 7.16 | 15.75 | 6.97 | 15.60 | 8.18 | 18.72 | 5.44 | 21.17 | 6.05 | 19.29 | 9.05 | |

| FSCRS-IS | 23.55 | 6.15 | 20.90 | 8.17 | 17.67 | 7.78 | 22.97 | 6.35 | 23.97 | 6.04 | 23.47 | 7.42 | |

| SCS-SF | 28.66 | 7.71 | 33.00 | 7.84 | 32.87 | 8.52 | 27.95 | 6.75 | 27.67 | 7.04 | 26.72 | 10.02 | |

| PHQ-9 | 13.17 | 6.47 | 10.00 | 7.15 | 10.47 | 7.10 | 13.77 | 5.17 | 14.70 | 5.80 | 14.29 | 7.11 | |

| GAD-7 | 12.72 | 5.04 | 10.35 | 5.76 | 8.00 | 4.86 | 12.05 | 4.49 | 12.53 | 4.80 | 11.94 | 6.79 | |

| Between-Group Effect Sizes | Within-Group Effect Sizes (Baseline/Post-assessment) | ||||||||||||

| Post-assessment | Follow-up | Intervention Group | Control Group | ||||||||||

| ESS | 0.76 | 0.49 | -1.23 | -0.25 | |||||||||

| OAS-2 | 0.83 | 0.43 | -0.55 | + 0.34 | |||||||||

| FSCRS-IS | 0.43 | 0.76 | -0.40 | + 0.04 | |||||||||

| SCS-SF | 0.72 | 0.66 | + 0.65 | -0.03 | |||||||||

| PHQ-9 | 0.72 | 0.54 | -0.56 | + 0.16 | |||||||||

| GAD-7 | 0.41 | 0.67 | -0.58 | + 0.02 | |||||||||

ESS Experience of Shame Scale, OAS-2 Other As Shamer Scale-2, FSCRS-IS Forms of Self Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale, Inadequate Self Subscale, SCS-SF Self-compassion Scale-Short form, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; Cohen’s d effect size: small ( d = 0.20), medium ( d = 0.50), large ( d = 0.80); a plus or minus sign fronting a within-group effect size indicates the direction of change (i.e., increase or decrease in magnitude)

Bivariate correlations of study variables at baseline

| ESS | OAS-2 | FSCRS-IS | SCS-SF | PHQ-9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS-2 | 0.48 | – | – | – | – |

| FSCRS-IS | 0.32 | 0.42 | – | – | – |

| SCS-SF | -0.38 | -0.42 | -0.58 | – | – |

| PHQ-9 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.40 | -0.32 | – |

| GAD-7 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.30 | -0.23 | 0.63 |

ESS Experience of Shame Scale, OAS-2 Other As Shamer Scale – 2, FSCRS-IS Forms of Self Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale, Inadequate Self Subscale, SCS-SF Self-compassion Scale- Short form, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; 2-tailed correlations

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01