How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

The 7 cs of communication.

A Checklist for Clear Communication

Creative Problem-Solving Technique

Using Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and take advantage of our 30% offer, available until May 31st .

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Winning Body Language

Business Stripped Bare

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Nine ways to get the best from x (twitter).

Growing Your Business Quickly and Safely on Social Media

Managing Your Emotions at Work

Controlling Your Feelings... Before They Control You

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Paired comparison analysis.

Working Out Relative Importances

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Casey Life Skills Toolkit

Casey Life Skills (CLS) is a set of free tools that assess the independent skills youth need to achieve their long-term goals. It aims to guide youth toward developing healthy, productive lives. Some of the functional areas that CLS assesses include:

- Daily living and self-care activities

- Maintaining healthy relationships

- Work and study habits

- Using community resources

- Money management

- Computer literacy and online safety

- Civic engagement

- Navigating the child welfare system

Inside the CLS Toolkit, you will find these resources:

- CLS Assessments in PDF and Excel format, giving you several options to administer the assessments and integrating them into your own systems.

- Practitioner's Guide , which shares best practices for administering and scoring the assessments, and more details on how CLS is beneficial for the service provider and youth.

- Resources to Inspire Guide , which lists resources that have been vetted by youth, caregivers and service providers as helpful ways to strengthen independent life skills.

These tools have been revised to ensure that they incorporate the needs of youth in the 21 st century. They have been developed in collaboration with foster care alumni, resource parents, service providers and child welfare experts to center the needs and voices of youth. Please see Release Notes below for periodic updates.

CLS is designed to be used in a collaborative conversation between an educator, mentor, case worker or other service provider and any youth between the ages of 14 and 21. It can be used by all youth regardless of whether they are in foster care, live with biological parents or reside in a group home. The tool should be used as a guide to empower youth in their journey to understand and enhance their life skills.

Youth typically will require 30-40 minutes to complete the CLS standard assessment, or 5-10 minutes to complete the CLSA short assessment. The assessment can be administered all at once or divided into the nine subsections. The educator, mentor, case worker or service provider are encouraged to use the CLS Resources to Inspire Guide with the youth after the assessment to create a learning plan and support the development and strengthening of skills.

Both versions of the CLS assessment have been reviewed and revised by a team that has worked with foster care alumni, resource parents, agency staff and life skills experts. We have used a diversity, equity and inclusion lens to help guide these revisions. We have included two new skill areas: civic engagement and navigating the child welfare system. We have also included a new supplement that assesses a youth’s access to formal and informal supports.

Version 1.4 (December 19, 2022)

- 7 new supplemental forms in English and Spanish are available in PDF and self-scoring Excel version (American Indian and Native Alaskan, LGBTQ+, Parenting Infants, Parenting Young Children, Support Systems, Youth Level 1, and Youth Level 2).

- CLS Standard and Short assessment in English and Spanish are available in PDF and self-scoring Excel version.

Version 1.3 (June 8, 2022)

- Revised Demographic section in all assessments to provide the option of “Other” and “Prefer not to Say”.

- Added Spanish version for CLS Practitioner’s Guide, CLS Standard assessment, CLS Short Assessment and CLS social support supplemental assessment.

- Added 6 Supplemental assessments for LGBTQ youth, American Indian and Native Alaskan, Youth level 1, Youth level 2, Parenting youth, and Parenting Infants.

Version 1.2 (January 25, 2022)

- Corrects calculation error in example on p. 13 of Practitioner’s Guide

- Updates link for cooking measurements on p. 13 of Resources to Inspire Guide.

Version 1.1 (December 7, 2021)

- Corrects formula error in the standard assessment results tab cell B9 affecting score calculations for Career and Education planning.

Version 1.0 (November 8, 2021)

- Initial Release of CLS toolkit

Can I use the CLS online assessment after April 11 th , 2022?

No, the old Casey Life Skills website is only available until April 10, 2022. After that time, using the new Casey Life Skills Toolkit will be the only way to administer CLS assessments.

Can my old account be used with the new system?

The new, downloadable Casey Life Skills Toolkit does not require you to create or maintain an account, although you will need to fill in contact details and agree to licensing terms in order to access the download. Since the new Toolkit does not use accounts or logins, your old Casey Life Skills account will not be used in the new system.

Will my data for all old CLS assessments be deleted in April or May?

You can preserve your data by downloading it from the old system using these steps: https://www.casey.org/media/CLS-Data-Download-Instructions.pdf . This download tool will be available for you to use until May 9, 2022, after which all data in the old system will be deleted. The earlier, April 11 deadline is when assessments can no longer be created in the old system, but you will still have about a month after the old assessment tool closes down in order to export data.

The new user agreement asks for someone with authority to enter a contract to sign the agreement. It also says it’s non-transferable. So how do front line staff access the toolkit?

The agreement is with the organization that is going to use it. Someone with authority to bind that organization needs to sign it. Once the contract is signed, you will be able to download the toolkit content and use it within the organization (including front line staff). There is no password or username needed. However, you may not share or transfer the content of the toolkit outside your organization.

I'm not able to download the toolkit.

Please review the steps below to see if they address your issue:

- Make sure that you are downloading the Toolkit using a modern browser such as Chrome, Edge, Safari, Firefox, or Opera. Internet Explorer is not supported at this time.

- When completing the form in the download agreement popup, make sure that you have filled in all fields and that you have clicked the box beside "I Accept the Terms of the Agreement Above."

- If you have tried using the download with a supported browser and confirmed that you've filled in all fields on the popup, please contact your internal IT department for further assistance. Some organizations may have security measures in place that prevent you from downloading or decompressing a *.zip file, which is the file format Casey Family Programs is using to distribute the Toolkit.

- Even if you have security policies in place that block these types of downloads by default, your IT department may be able to work with you to develop an exception process -- for example, an IT administrator may be able to download the toolkit themselves and verify that it is safe, then distribute the Toolkit by email or secure file sharing within your organization. Other organizations may choose to fully rebuild CLS in their own survey and assessment tools, which is a permitted use (with attribution and without modification to the questions) under the terms of the new licensing agreement.

- Whichever path you choose, it's important to begin developing these new IT processes as soon as possible, since the old Casey Life Skills website will not accept any new assessments after April 10, 2022.

Can I use the new toolkit online?

The new CLS toolkit is a downloadable set of PDFs and XLTX files that are intended to be used in desktop applications rather than online. The XLTX versionworks with Microsoft Excel and has the ability to score the assessment automatically (all the results can be viewed in the ‘result’ tab). The PDF version can be printed and hand scored. All hand scoring instructions are available in the Practitioner’s Guide. The new licensing agreement for the CLS Toolkit does permit your organization to import the CLS questions (unaltered, and with attribution) into your own online survey or assessment tool. Building a new online version of CLS is a technical project that would most likely need to be undertaken by the administrators of your tools. Although Casey Family Programs is no longer participating in building online versions of CLS, we can offer some limited support if your IT department has specific questions about adopting this approach.

Are there bar graphs available in the new toolkit?

The old Casey Life Skills reporting features are being retired, since it would not be possible for Casey Family Programs to provide these reports without storing your agency's sensitive youth data. However, the new Excel spreadsheets included in the downloadable Toolkit do contain a tab called Results where youth responses are tabulated and depicted in a similar bar graph as well.

Where do we enter the new CLS assessment answers on the website?

The newest version of Casey Life Skills is only available as a downloadable PDF or Excel spreadsheet -- it is not being incorporated into the old Casey Life Skills website. To download the new Toolkit, go to https://www.casey.org/casey-life-skills . Please note that the old Casey Life Skills website is only available until April 10, 2022. After that time, using the new Casey Life Skills Toolkit will be the only way to administer CLS assessments.

Will I be able to email youth using the new system?

The old Casey Life Skills website included a feature that allowed you to email youth links to create accounts, take assessments, and view their results. Providing this service required Casey Family Programs to store personally identifiable information about youth. This online mailing functionality is being retired by April 11, 2022, in order to allow your organization to control how youth information is stored and used.

You can now use the Toolkit to send the same type of information to youth using your own systems, rather than using Casey Family Programs' systems to send and receive information on your behalf.

After you have downloaded the Toolkit and extracted its files, you may simply send youth a copy of the Excel spreadsheet version of the assessment as an attachment to one of your standard emails. After they have filled in the spreadsheet, they will be able to save the file and send it back to you as an attachment or upload it to a file sharing system owned by your organization. The spreadsheet also contains a Results tab that you and the youth can use to view and discuss their scores. Please consult with your IT department if you have questions about how best to securely send and receive Excel files.

Does Casey Life Skills offer a curriculum that addresses areas for improvement identified by the assessment?

Casey Family Programs has recently updated a list of recommended resources that you can use to follow up with youth who have taken the assessment. We have also provided a Skills worksheet that can help you and the youth develop a plan for their life skills development. These recommended resources are collected in our Resources to Inspire Guide , which you can find inside the new downloadable Toolkit. We have also provided suggestions in the Practitioner's Guide on how best to use the assessment results to help strengthen youth skills.

Is training available on administering Casey Life Skills ?

Information on how to administer Casey Life Skills and how to score the assessment are contained in our Practitioner's Guide , which you can find inside the new downloadable Toolkit. If you still have practice-related questions after reviewing the guide, please fill out the "Feedback and support" form at https://www.casey.org/casey-life-skills , or email us at [email protected] .

Is it possible to compare the results of two assessments taken by the same youth?

We do not currently offer reports that can compare two assessments taken by the same youth over a period of time. However, our new Toolkit ( https://www.casey.org/casey-life-skills/ ) does include Excel versions of the assessments that you can administer to youth. Once you have collected their responses in this new format, you can create new reports using Excel.

Can I use the new XLST version of the assessment with online spreadsheet applications such as Google Sheets?

The XLTX assessment files included in the Toolkit were created and tested in Microsoft Excel, which is available for both Windows and Apple devices. It is possible to open the files with Google Sheets. In Google Sheets, you may go to File > Open > Upload, then select the CLS file you would like to upload. When using Google Sheets for multiple assessments we recommend you use File > Make a Copy to generate a new, duplicate spreadsheet from a blank master file before distributing the survey link to a new respondent.

Please note that our technical support is not intended to be a recommendation for the adoption of any particular product, and you will still need to make your own judgement regarding the security and privacy of tools like Google Sheets following your organizational policies for managing youth data.

I don’t have access to Microsoft Excel. Is there another program I can use instead?

The XLTX assessment files included in the Toolkit we created and tested in Microsoft Excel, which is available for both Windows and Apple devices. If you don't have access to Excel, however, there are free and open-source spreadsheet programs that will also work (for example, LibreOffice), with some differences in user experience. If you can't find an alternative spreadsheet program that you're willing to install on your device, we would recommend using the PDF format of Casey Life Skills, which can be printed and filled out by hand.

Can I upload the survey to an alternate survey platform such as Qualtrics or Survey Monkey?

Yes! The terms of the new licensing agreement allow you to upload CLS assessments into the survey platform of your choosing for non-commercial purposes, provided that you do not alter the questions and that you attribute Casey Family Programs as the developer of the survey. Please review our new licensing agreement for further terms.

At this time we are only offering CLS in an XLST or PDF format. If you would like to upload CLS using the native file format of another survey tool, the easiest way to accomplish this would most likely be to use Microsoft Excel to manipulate the XLST version of the assessment provided in our Toolkit and save your work as a CSV formatted for the platform you are targeting. At this time, we are not able to create CLS in alternate file formats, but we will try to help answer specific questions if you run into issues while creating your surveys.

Resources Questions from the field Research reports Speeches and testimony Policy resources Practice tools Browse all resources DOWNLOAD CLS Toolkit ZIP: 21.7 MB

Thank you for your interest in our publications. If you'd like to receive alerts about new resources and announcements, please subscribe to our email lists. We will not share your information.

- Sign up to receive announcements and other updates from Casey Family Programs.

- Sign up to receive research information, resources and other updates from Casey Family Programs.

Receive Email Updates

Receive periodic email from Casey Family Programs. We will not share your information.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Professor of Business Administration, Distinguished University Service Professor, and former dean of Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, facets of life skills education – a systematic review.

Quality Assurance in Education

ISSN : 0968-4883

Article publication date: 22 August 2022

Issue publication date: 28 February 2023

The study aims to review the existing theories and literature related to life skills education for adolescents to construct a model portraying the inter-relatedness between these variables. This study discerns the inferences from the studies conducted earlier to propose various aspects to be considered for future research and interventions targeting the effectiveness of life skills education for adolescents.

Design/methodology/approach

Prolific examination of numerous theoretical and empirical studies addressing these variables was carried out to formulate assertions and postulations. Deducing from the studies in varied streams of education, public health, psychology, economics and international development, this paper is an endeavor toward clarifying some pertinent issues related to life skills education.

Although there is abundant evidence to encourage and assist the development of life skills as a tool to achieve other outcomes of interest, it is also important to see life skills as providing both instrumental and ultimate value to adolescents. Quality life skills education needs to be intertwined with the curriculum through the primary and secondary education, in the same way as literacy and numeracy skills.

Originality/value

The present study has important implications for educators and policymakers for designing effective life skills education programs. Additionally, this paper provides a three-step model based on Lewin’s three step prototype for change, to impart life skills trainings to adolescents through drafting pertinent systems. This will help in imparting quality life skills education to adolescents and raising them to be psychologically mature adults.

- Life skills

- Adolescents

- Lewin’s three step model for change

- Life skills education

- Socio economic status

- Lewin’s force field theory

Bansal, M. and Kapur, S. (2023), "Facets of life skills education – a systematic review", Quality Assurance in Education , Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 281-295. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-04-2022-0095

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Publisher Home

- Author Guidelines

- Editorial Team

- Quality Policy

- Submission Procedure

- Publication Ethics

- Announcements

Developing Important Life Skills through Project-Based Learning: A Case Study

Main article content.

case study, life skills development, Project-based learning, education

Project-based Learning (PBL) is regarded as an effective teaching method to help students develop their life skills to meet the needs of the 21st century. However, PBL has not been widely implemented in Vietnam. Therefore, this case study was conducted to explore how effective PBL was to students' life skills development. Thirty-three students and an instructor in a university participated in the study. Data were collected using six classroom observations, and semi-structured interviews with nine students and the instructor. The study showed that PBL dramatically helped improve the students' problem-solving, critical-thinking, time-management, and interpersonal relationship skills. PBL also promoted some students' creativity, information technology (IT), research, leadership and film-making skills. The benefits and difficulties they encountered while doing projects motivated them to love projects that they even suggested that the school should incorporate more projects into the curriculum. The study recommends that PBL should be more widely implemented to maximize the development of students' life skills at universities.

Article Sidebar

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

Modal Header

Workforce Skills Curriculum Development in Context: Case Studies in Rwanda, Algeria, and the Philippines

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 November 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Catherine Honeyman 13 ,

- Laura Cordisco Tsai 14 ,

- Nancy Chervin 15 ,

- Melanie Sany 15 &

- Janice Ubaldo 16

Part of the book series: Young People and Learning Processes in School and Everyday Life ((YPLP,volume 5))

7676 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Life skills programming in the field of international workforce development operates within a professional community of practice that is shaped by dynamics of power, influence, and resources, as well as by specific local contexts and actors. This chapter gives detailed insight into three case studies of youth workforce life skills programming developed by the organizations World Learning, Education Development Center, and 10ThousandWindows in different national settings and with distinct youth populations, highlighting how these organizations have interacted with the larger field and learned from one another to address issues of contextualization, pedagogy, sustainability, and scale. Through descriptions of programming in Rwanda, Algeria, and the Philippines, the chapter offers insight into the complexities of life skills curriculum development and contextualization processes and highlights issues that remain difficult to resolve, as well as new frontiers for programming in rapidly changing economies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Global Perspectives on Youth and School-to-Work Transitions in the Twenty-First Century: New Challenges and Opportunities in Skills Training Programs

Developmental Approach to Work Readiness for Youth: Focus on Transferable Skills

A Possible Me? Inspiring Learning Among Regional Young People for the Future World of Work

- Youth employment

- Workforce development

- Soft skills

- Life skills

- Philippines

Introduction

One major domain of life skills programming falls within the workforce development field, which broadly focuses on preparing people for employment or self-employment in particular social and economic contexts (related to what Murphy-Graham & Cohen, Chap. 2 , [this volume] categorize as labor market outcomes). Workforce development programming may focus on different age groups and on a range of workforce concerns; this chapter’s focus is on life skills for youth workforce programming in the international development arena.

Diverse youth workforce development actors have their own institutional perspectives on life skills—whether referred to as transferable skills, social emotional skills, soft skills, or under other names. There is growing consensus, however, that these skills play a crucial role in youth employment, entrepreneurship, and earning outcomes and should be a focus of investment in addition to the more traditional emphasis on academic, technical, and vocational skills. At the national level, workforce development actors involved in life skills education include government agencies, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) agencies, higher education institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and private sector representatives. Multilateral organizations, bilateral donors and philanthropy funders, and international nonprofit and for-profit organizations are also involved in workforce development programs in various contexts.

Approaches to life skills in these circles are shaped by a variety of factors, including funders and their priorities, exchanges among implementing organizations, research, and local concerns. This chapter focuses on how three organizations involved in youth workforce development have interacted with these different forms of influence on life skills programming, confronting questions of contextualization, pedagogy, sustainability, and scale in three very different contexts—Rwanda, Algeria, and the Philippines. In particular, we focus on donor and developed country institutions as powerful actors in an international field of influence that shapes programming, and the discourse of an ad hoc professional community of practice that shares ways of thinking and doing around life skills—while also showing that this international influence is tempered by efforts to adapt life skills programming for particular contexts and populations.

Influences of an International Community of Practice

The three organizations whose cases are featured in this chapter, World Learning, Education Development Center (EDC), and 10ThousandWindows (10KW), are all nonprofit organizations active in the youth workforce development field. While World Learning and EDC are both based in Washington, DC and operate various types of educational programming in multiple countries around the world, 10KW focuses its work specifically on survivors of human trafficking and violence in the Philippines. As organizations, we have come into contact in a variety of spaces focusing on international workforce development and life skills programming for employability—including in conferences, webinars, workshops, and email listservs. These spaces have created, both intentionally and organically, a large professional community of practice characterized by a shared interest in teaching employability skills internationally. By “community of practice” we mean the social relationships that naturally develop among people and institutions engaging in related activities, who over time develop shared ways of thinking and doing through situated learning, as described in the ethnographic work of Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger ( 1991 ). This particular ad hoc community of practice also includes many other members from the international development community.

The situated learning around employability life skills programming that takes place within this community of practice is influenced by factors of power, positionality, and command of resources (Bourdieu, 1972 , 1990 ), as well as by research, context, and learning from experience. Major developed-country education systems and large private corporations have significant influence in this international community of practice, as life skills curricular frameworks such as Equipped for the Future, SCANS, P21, and ATC21S, reflecting the input of companies such as Apple, Microsoft, CISCO, and Intel, have been taken up as references for developing country contexts (See Stites, 2011 for more on the history of corporate frameworks and influences). Other organizations and funders, including the OECD (Kautz et al., 2014 ), the World Bank ( 2019 ), the World Economic Forum ( 2018 ), and the MasterCard Foundation ( 2017 ), also publish influential resources on life skills and their relationship to improving employment outcomes, carrying significant weight with practitioners due to these organizations’ economic, cultural, and social capital (Bourdieu, 1986 ).

For many organizations implementing international youth workforce programs, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) also plays a prime, influential role as one of the largest funders of international workforce development programming. USAID-funded workforce development projects, each typically 3–5 years in length, operate in some 30 countries around the world. Recent figures suggest they reach approximately 200,000 youth per year (Honeyman & Fletcher, 2019 ). While this reach is still nowhere near the numbers of youth involved in government-run workforce development systems in those same countries, USAID has had an outsized influence in consolidating certain research in the life skills domain, and has shaped practice through intentional learning coordination mechanisms, Footnote 1 through the assumptions set out within USAID requests for proposals, and through other means such as standardized indicators for measuring project achievements. Among other effects is USAID’s adoption of the term “soft skills” for the social, emotional, cognitive, and employability skills that are the focus of the workforce development programming it funds. In contrast, USAID primarily uses the term “social-emotional learning” for basic education programs, and “life skills” for youth sexual and reproductive health-focused programs, despite significant overlap among the specific skills designated by these terms. Because this chapter is concerned with workforce development programming that has been influenced by USAID terminology, we use the term “soft skills” from this point forward (although we recognize these are broadly equivalent to “life skills” as conceived by other authors in this volume).

Some two dozen international organizations, both for-profit and non-profit, implement most of the large-scale workforce development programs funded by USAID, the US Department of Labor, and the US Department of State. Footnote 2 As the research and discourse around soft skills and employability has evolved over the past two decades in the fields of psychology, education, and economics, as well as within donor discourse, these organizations have increasingly converged in their language and practices even as they have deepened and clarified their approaches to soft skills programming. The three case studies featured in this chapter illustrate that convergence while also offering insight into the complexities of soft skills curriculum development and revision processes in very different contexts and with different target populations. Footnote 3

Each organization included in this chapter first developed its own institutional approach to soft skills curriculum around 2009, beginning with projects in the core national contexts featured here. A brief timeline illustrates how these organizations, and their soft skills education programming and discourse, have been tied together within the larger community of practice described previously. EDC’s soft skills approach, first developed for Rwanda in 2009 and initially based on US and OECD curricular frameworks, became one of the sources consulted in a pivotal USAID-funded publication “Key ‘soft skills’ that foster youth workforce success: Toward a consensus across fields” (Lippman et al., 2015 ). Featuring an extensive international literature review, that publication aimed to determine the skills with greatest international research evidence of impact on four types of workforce outcomes—employment, promotion, income, and entrepreneurial success—as well as the skills with evidence of malleability during the youth years. The report ultimately recommended that programs focus on five soft skills: positive self-concept, self-control, social skills, communication, and higher-order thinking skills. Subsequently, USAID funded a literature review on effective pedagogical methods for soft skills development, which also drew on EDC approaches among a range of other models (Soares et al., 2017 ). USAID circulated these publications widely and referred to them in requests for proposals, ensuring that they became well-known among the organizations implementing workforce development programs internationally.

Meanwhile, World Learning and 10KW had also developed their own approaches to soft skills programming around 2009, drawing on a combination of US and international influences (Algeria and the Philippines, respectively). In 2017, after many years of program implementation, World Learning consulted the USAID publications above, as well as other research sources, to create guidance for its own soft skills curriculum revision process globally. World Learning also shared this guidance and a set of curriculum development tools externally in industry-specific conferences and other settings. It was in one such conference Footnote 4 that 10KW, EDC, and World Learning staff came together and began exchanging experiences around their soft skills curricula and programming, with 10KW subsequently using the World Learning tools for its own process of curricular revision.

Our conversations and experiences as technical advisors of organizations implementing soft skills programming for workforce development within this international community of practice have brought to the fore three major issues in developing our programs: contextualizing the focus of soft skills programming, determining and training for effective pedagogical approaches, and sustaining and scaling up these initiatives.

Contextualization

In the midst of a movement towards more uniform global recommendations for soft skills development, and despite a certain homogenizing influence from institutions such as USAID and the OECD as described previously, international development program implementers continue to recognize the key importance of having contextually relevant curricula that evolve based on experience with particular populations. The cases in this chapter show how implementing organizations must both respond to the expectations of funders and report on standardized indicators, and also dialogue with and respond to important local actors, including government agencies, training institutions, and youth themselves.

While the past decade has featured demonstrably greater consensus around the importance of teaching particular soft skills, how to do so effectively is another matter. The authors’ experience with mainstream competency-based curriculum development processes around the world shows that education institutions often end up neglecting the non-academic skills and “attitudes” aspect of their curriculum development frameworks as they progress from initial outlines towards more detailed curricula, pedagogical recommendations, and learning materials (see Honeyman, 2016 ). In great part, this may be because the methods for developing soft skills are not well known or understood. The cases in this chapter therefore document our pedagogical approaches for developing these skills.

Sustainability and Scale

Another significant challenge that implementers of soft skills development programming face is the question of how to institutionalize effective curricula into a broader system capable of reaching much larger populations, or deepen it to achieve sustainable change for target populations over time. Research by the MasterCard Foundation (Ignatowski, 2017 ) examined three soft skills development programs in Sub-Saharan Africa that have achieved larger scale, identifying six key drivers: an enabling policy environment, evidence of impact on youth outcomes, strong political champions, wide stakeholder engagement, decentralization of authority, and flexible funding. This chapter’s cases illustrate the importance of these factors and make clear that the dominant short-term project-based mode of the major funders of soft skills and workforce development programming poses a significant obstacle to sustaining and scaling up such programming, ultimately limiting the chances for many youth to develop these skills despite the significant resources invested for that purpose.

The case studies that follow focus on illustrating how the three aspects of soft skills curriculum development addressed above—contextualization, pedagogy, and sustainability and scale Footnote 5 —have played out in three very different contexts: Rwanda, Algeria, and the Philippines. A concluding section following the case studies highlights common challenges with soft skills curriculum development processes, as well as discussing the new frontiers that are now emerging in the teaching of soft skills for labor market outcomes.

Rwanda: Work Ready Now (Education Development Center)

Information provided for this case study was primarily collected in the form of practitioner reflections. It also includes reference to an experimental study with randomly assigned treatment and control groups, which was approved by EDC’s ethics review board.

Country Context

Since 2009, Education Development Center has been leading youth programs in Rwanda with funding from USAID and the MasterCard Foundation. EDC’s local team and partners provide youth with the skills to continue their education, find employment, or start their own businesses. Rwanda is a youthful country: 50% of the population is below 20 years old. Despite impressive economic growth in the past decade, the national poverty rate is 39%; among youth, however, it is 70% (with 55% in extreme poverty). In 2018, 31% of youth were not engaged in education, employment or training, and 65% were underemployed (World Bank, 2020 ). Youth are disproportionately located in—and migrating to—urban areas, where youth unemployment is three times that of rural areas (YouthStart, 2016 ). Each year, 125,000 first-time job seekers enter the labor market, a number which the economy is unable to absorb, so only a handful gain access to the formal sector (YouthStart, 2016 ). As a result, most youth work in the informal sector.

Over the last decade, there has been a consistent, clear vision to propel Rwanda into middle-income status, which includes significant changes to the workforce development system. One of the main targets has been to create roughly 200,000 non-farming jobs per year, which has motivated action across national ministries. The government has also emphasized the role of TVET in reaching its economic goals, aiming to increase the number of lower secondary school students entering TVET from 21% in 2017 to 60% by 2024. Nonetheless, when EDC began our work in Rwanda in 2008 with the USAID Akazi Kanoze project focusing on out-of-school youth between the ages of 14 and 24, we found that there was:

No curriculum informed by employer demand, nor localized labor market assessments

No incorporation of soft skills into the secondary school curriculum

Little to no use of hands-on, learner-centered pedagogical approaches.

In response to these gaps, we developed an approach that included work readiness training for youth. In close partnership with the Rwandan government, our strategy grew organically as we adapted our work readiness curriculum to various youth populations. As the approach gained more interest from the government, demands to expand the program beyond out-of-school youth to those in the TVET and formal education systems increased, enabling us to work with the government and local organizations in adapting and incorporating our training into existing systems.

Our original program design, responding to USAID-required activities, proposed a model that networked out-of-school youth with business opportunities through local NGOs. As we grappled with the question of how these NGOs could better prepare youth for jobs, the idea of a work readiness curriculum emerged, focusing on building the soft skills and competencies youth need for their first entry-level jobs or to run their own small businesses. At the time, little detailed information existed in the international development space about curricula that met these requirements, so we began by developing a curriculum framework that defined the key content areas for a comprehensive skill development program with an emphasis on livelihoods and work. The curriculum framework initially drew from the Equipped for the Future standards, developed for adult learners in the United States, and which was externally evaluated in 2011 to ensure alignment with three internationally recognized work readiness frameworks: SCANS, P21, and ATC21S (Stites, 2011 ). In 2015, we also analyzed how the Big Five Personality Factors (see Murphy-Graham & Cohen, Chap. 2 , this volume) were addressed because these categories of noncognitive skills are related to success in both school and the workplace. The Big Five are increasingly viewed as important for a variety of uses in workforce development: selection, training, outcomes assessment, professional development, and international comparisons (Roberts et al., 2015 ). In 2013, EDC and Professional Examination Services developed a learner assessment using situational judgement questions based on the Big Five Personality Factors and Work Ready Now (WRN) modules. It is important to note that the WRN framework was developed 5 years before USAID conducted its review of soft skills frameworks and skill areas, described in the previous section. Our framework was later included in, and seems to have significantly shaped, this research.

This framework served as a starting point for developing the curriculum in Rwanda, later becoming EDC’s global Work Ready Now (WRN) curriculum. A curriculum framework, the scaffold upon which a full curriculum is built, defines the skills, knowledge, and behaviors that are to be taught and learned. EDC’s WRN framework covers intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, including skills that are used in a variety of settings and not just work (such as goal-setting and communication), employability skills (such as workplace behaviors), and critical thinking skills (such as evaluation of appropriate strategies). Illustrative teaching and learning activities accompany each skill.

After a review of the framework in Rwanda, modules were drafted by a mix of Rwanda- and US-based technical advisors. Next, a series of curriculum development and revision workshops took place. A group of Rwandan NGO partners, facilitators, and business representatives as well as staff from the Rwandan Ministry of Public Service and Labour (MIFOTRA) and the Workforce Development Agency (WDA) reviewed the modules. They also provided feedback regarding the content, language, methodology, context, and cultural appropriateness. This process resulted in deleting, changing, and adding activities, particularly to align with Rwanda’s skills development priorities in customer care and entrepreneurship.

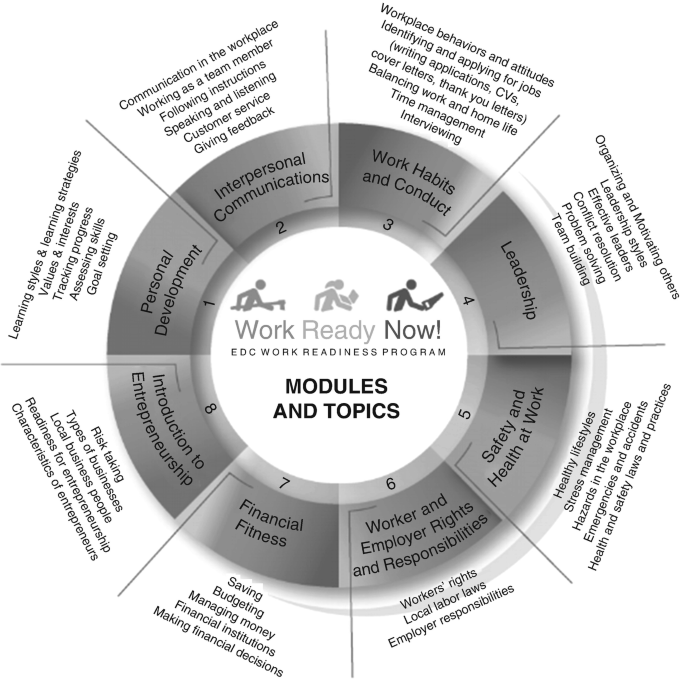

The resulting Rwandan curriculum consisted of eight modules, with materials for 120 h of instruction, as depicted in Fig. 6.1 .

Work Ready Now modules and topics

These modules include personal development, communication, finding and keeping work, leadership, health and safety, workers’ rights and responsibilities, financial fitness, and an introduction to entrepreneurship. Overall, the modules seek to develop a large number of specific soft skills, including: self-reflection, assessing, goal-setting, taking initiative, communication (listening and speaking in the workplace, giving presentations, giving and receiving instructions and feedback), social skills (cooperating, working in a team, providing good customer service), cognitive skills (finding and analyzing information, reading for information, decision-making, and problem-solving), behaving appropriately at work, planning skills (managing time, managing home and work life, tracking personal progress), and leadership, among others.

The original intention was that other countries could develop their own curriculum using the WRN framework. Though the curriculum development process proved to be time-intensive, taking almost a year in Rwanda, we found that the resulting curriculum and materials were easily adaptable for other contexts and that it would not be necessary for every country to start from scratch. We have been able to adapt versions of the Rwandan WRN curriculum to new countries according to youth levels of education and socioeconomic situations. Key players adapt WRN to the local cultural and economic context during a workshop, which brings together youth-serving organizations, government officials, instructors, and the private sector. A local adaptation will pinpoint issues such as needing to prepare youth for communicating with people from other cultures, identifying the specific finance service providers in a country, or localizing job seeking processes such as the use of virtual interviews and networking sites like LinkedIn which vary from country to country. Furthermore, the majority of scenarios, work-based situations, and role models come from examples from the country of adaptation. We developed a WRN implementation toolkit to formalize this adaptation process. This toolkit helped to maintain consistency and quality as we contextualized WRN for 26 countries in the last 10 years.

The WRN curriculum developed first in Rwanda uses techniques such as group activities, role-plays, large- and small-group discussions, and personal reflection. Youth practice customer service interactions in role plays, simulate doing a complex office move to learn about cooperating as a team, and map out their goals as they create professional development plans. Like the World Learning and 10KW programs described below, youth also develop career portfolios comprised of items they will use for job seeking, and wraparound activities such as workplace exposure to complement the training outside of the classroom. Work exposure includes observations, informational interviews, and job shadowing assignments that require the youth to identify workplaces and build relationships with employees at local businesses. After completion of the WRN training, Rwandan youth enter an accompaniment phase of the program where they continue to do observations and conduct informational interviews as they seek employment or begin their own business.

Our experience in Rwanda demonstrated that for implementation to be successful, the content and pedagogy must be maintained, and sufficient teacher training provided. WRN’s participatory learner-centered approach is intentionally outlined in very detailed steps. It is designed for use by both less experienced facilitators and instructors who may be accustomed to more traditional approaches. We found that, on the one hand, an NGO facilitator may be youthful and energetic and take naturally to the activities but have minimal prior facilitation experience. On the other hand, a Rwandan schoolteacher may have taught for 20 years, but mainly through lecture format. Both groups appreciate that the steps walk them through what they say and do all along the way.

The training of trainer’s approach emphasizes mastering the content and pedagogy. Trainings are slowly paced, with a day spent on each module. The first training of trainers workshops in Rwanda averaged 10 days in total (split into two workshops, covering different modules, with the second workshop including reflection on their teaching so far). Each trainer gains a background in adult learning, experiences learner-centered instruction, and leads at least two teaching demonstrations. They receive structured feedback both during the training and while implementing the curriculum. Teachers tend to be enthusiastic adopters of the curriculum. While teachers in Rwanda had received professional development in learner-centered approaches as part of the formal school system, many have remarked that it was the WRN training that helped them finally grasp this approach. Practicing the delivery of activities during the training and using the methods in the curriculum with youth in their classrooms helped them to internalize learner-centered, participatory approaches. Class size needed to be considered carefully, however. The curriculum was originally designed for a trainer and assistant to lead a class of 25 youth. In the Rwandan school system, the ratio was often one teacher to up to 50 youth in a class. Activities were rethought so they could still be participatory within this constraint.

Today, these practices, particularly the pedagogy underlying the WRN approach and the use of the WRN curriculum itself, are widespread among a number of private and public service providers including public technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and formal education institutions. By including local stakeholders in the development process, they took ownership of the curriculum and promoted it in their institutions. For instance, following the first Rwandan curriculum revision workshop described above, the Ministry of Public Service and Labour requested that we provide training to several hundred youth. Ultimately, we trained and mentored over 200 trainers from private institutions, as well as over 700 school directors, master trainers, and teachers from public TVET and secondary schools. This learner-centered soft skills training reached over 200,000 in-school youth and 60,000 out-of-school youth.

While the soft skills program in Rwanda began with USAID-defined objectives and funding, it soon evolved beyond that frame towards institutionalization into permanent Rwandan structures and policies. Our work with out-of-school youth sparked interest from the Rwandan Ministry of Education, who in turn asked that we adapt WRN for the formal education system. This request took place in the midst of an education reform process that moved the system to a competency-based approach. Given WRN’s standards-based framework, it was a good match. The in-school adaptation in Rwanda took place alongside national reforms in two types of schools: TVET and general secondary.

For TVET, there was an existing effort with the government’s Workforce Development Agency to develop competency-based curricula in the national system. EDC plugged into that effort by mapping WRN content throughout the school year in each of the technical curricula. WRN aligned with the TVET qualification’s required complementary competencies, which include employability and life skills that are applicable to all occupations. At the same time, the local EDC team advocated for work readiness skills to be taught through the entire TVET system. The life skills curriculum was then validated and mandated as Level 3 under the TVET qualification framework. EDC worked with the WDA to merge its eight modules into five courses that included dedicated time for our activities. Minor adjustments were made to the terminology of the WRN training manual so it aligned with their curriculum. For example, WRN’s Personal Development module was integrated in their “Occupational and Learning Process” course.

For general secondary education, the government had started aligning the entire secondary curriculum to a competency-based approach, and it became clear that WRN could address some needs during this alignment. Through a comprehensive design process, we worked with the Ministry of Education (MOE) to embed WRN into their entrepreneurship instruction at all levels of lower and upper secondary. We participated in the competency-based curriculum reform process led by the Rwanda Education Board to help the entrepreneurship team integrate the curriculum. The team closely compared the existing materials with ours, developed a syllabus, and identified when WRN activities would be used by teachers in their units. Other than aligning terminologies, no major changes were required. The biggest challenge was deciding how to spread out the work readiness curriculum modules across the grade levels without losing continuity. We addressed this challenge by repeating essential topics within modules across the years. For example, goal setting and planning repeats itself over the years as learners’ interests and skills develop and change.

Because the WRN soft skills content is embedded into a national curriculum, it is not something “extra” for the teachers to do, but rather helps by providing them with high quality content that addresses the skills they need to teach. A true collaboration with the MOE enables us not only to align the competencies and the skills prioritized by the government of Rwanda and WRN, but also to influence the broader curriculum reform through WRN pedagogy and approach. In this shift to a competency-based approach, teachers were going to be required to teach differently—in a more participatory and less didactic way. WRN provided a model of how to implement a competency-based curriculum.

While adapting the curriculum to an in-school program, several considerations had to be addressed. First, for both school systems, careful consideration was taken to align the WRN competencies with the government’s own competency framework. In that process we helped the Rwandan Education Board integrate the content and methodology into entrepreneurship for secondary schools and we helped WDA integrate WRN into their core competencies in vocational schools.

Second, the flow and scaffolding of the competencies was considered carefully as the modules would be taught by different teachers at different levels. We needed to determine how the skills and activities in each module would be distributed across levels and subjects, ensuring that foundational knowledge and skills that feed into subsequent topics in the WRN curriculum were introduced before the more complicated topics. For instance, identifying one’s values, interests, and skills feeds into the next step of goal setting and writing a professional development plan. In Rwanda, this instruction was taught across all 6 years of secondary school but within one subject (entrepreneurship). Experience has shown that it is better to integrate the curriculum into as few subjects and levels as feasible in order to keep the WRN training as intact and compact as possible, so as to encourage youth to build self-confidence and comfort with their group. Facilitators also become familiar with the strengths and areas for growth among the youth. When it is not possible to keep it intact, it is helpful to have a week, at the end of the school year, when the students all come together at a given time to review key lessons.

Third, we found that it is important to identify the teachers, their availability, and who will train them. These could be local implementing partners or the inspectors in the system responsible for teacher training. In Rwanda, the capacity of Rwanda Polytechnic officials is now being developed to be responsible for teacher training for the TVET level 2 programs.

Finally, there are considerations to be made beyond the content and methodologies when integrating into schools and institutionalizing training materials into a school system. Adjustments may need to be made to the activity lengths (to fit within classes of 40 or 45 min length instead of 1–2 h sessions), to the materials used so that they are affordable (for ministries who purchase classroom supplies and parents who purchase the school books), and to the assessments (to ensure that the soft skills assessment can be used nationwide across all schools and in a format that can be administered by teachers in a classroom).

To make this range of work possible over multiple years, EDC competed for additional funding under multiple projects and donors. Without piecing together resources over a longer period of time, this depth of institutionalization and influence on the Rwandan educational system would not have been possible within a single project’s implementation timeframe.

Our research indicates that the route that we have taken – focusing on this particular content and pedagogy, while using a systems-strengthening approach – is meeting the needs of youth, employers, and educators. For out-of-school youth, 66% of program graduates have found employment or started an income-generating activity within 6 months of graduation. Ninety-seven percent met or exceeded employer expectations. In regard to in-school youth, youth in the program had larger gains in work readiness knowledge and key competencies than their peers. Participants were more likely to be employed after completing the program than those who did not participate (Alcid & Martin, 2017 ).

One of our key lessons learned was the extent of our curriculum’s adaptability. Two primary factors stand out: firstly, that a detailed curriculum framework guided its development. Secondly, it was vetted locally at all stages, from the framework development to the original adaptation and all subsequent adaptations. In the 10 years since we first developed the curriculum, technology has quickly changed the nature of the workplace. Yet the curriculum stands the test of time. It emphasizes skills such as adaptability, willingness to be a lifelong learner, and diligence—all of which are cited as key skills by employers globally. In today’s COVID-impacted world, we are exploring how to use technology for teacher training and delivery to youth without compromising quality and the value of face-to-face interaction.

Algeria: WorkLinks (World Learning)

This case study is primarily based on practitioner reflections and routine analysis of project monitoring and evaluation data collected as part of an educational process. It also includes reference to qualitative research approved by World Learning’s School for International Training IRB (IORG # 0004408).

World Learning has worked in Algeria since 2005, and we began workforce development-related programming in 2010 with support from the US State Department, later including private funders such as HSBC Bank and Anadarko Petroleum. In large part due to funder priorities, our focus in these projects has been quite different from EDC’s initial emphasis on out-of-school youth, described in the previous case study. In Algeria, we work primarily with the country’s large population of unemployed but educated youth with at least a high school diploma, and often a university or even post-graduate degree. Data on youth unemployment rates in Algeria varies widely. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, one study suggested that at least 39% of university graduates remain unemployed even three years after graduation (CREAD and ILO, 2017 ); official statistics—last reported in 2018 before a wave of protests that has continued to the present—documented overall youth unemployment at 29.1% (ONS, 2018 ). Algeria is considered an upper middle income country, but with a stalled economy that is nearly completely dependent on petroleum, accounting for over 94% of the country’s export revenue and making the country extremely vulnerable to external oil price shocks. Footnote 6 In this context, our youth workforce development projects have focused primarily on improving youth integration into formal employment positions in a variety of industries, including petroleum, plastics, construction materials, pharmaceuticals, IT, education and training, and more—across 12 Algerian governorates ranging from the highly-populated cities on the Mediterranean coast to desert regions in the south.

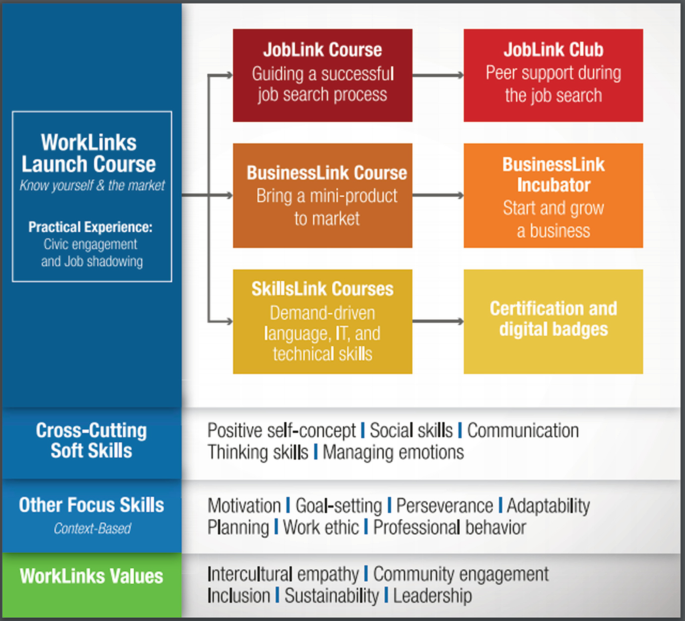

Since 2010, our approach to employability and soft skills training has evolved considerably, responding to local context, donor priorities, and implementation realities, as well as efforts to more deliberately incorporate research on effective soft skills instruction. World Learning’s Algerian education specialists, specifically trained in experiential learning pedagogy (Kolb, 1984 ), began initially with a small set of core courses that we developed to meet the needs of a new career center at the University of Ouargla, following some informal employer outreach and observation of students’ skills gaps in seeking employment. The modules, typically lasting 2 h each, included personal skills and interest assessments, writing customized CVs and cover letters, practicing interview skills, and learning about job search techniques. They did not overtly reference other soft skills, but they employed an experiential learning methodology used in all of World Learning’s global programs, which formally or informally employs cycles of experience, reflection, conceptualization, and further experimentation, designed to foster the development of communication, social skills, and critical thinking. For subsequent projects starting in 2012 and 2015 with university and TVET career centers in other parts of the country, field staff reflected on a key obstacle young people faced in Algeria—the lack of work experience—and sought to encourage volunteering as a means for overcoming this barrier, as well as for encouraging broader civic engagement and fostering increased engagement of youth with disabilities and other barriers to workforce participation. This team revised the curriculum accordingly, introducing new modules on leadership, overcoming individual and collective obstacles, volunteering to gain work experience, and action planning. This revised version continued focusing on communication and social skills, and added a focus on additional soft skills such as goal-orientation, planning, problem-solving, and teaching the value of social inclusion.

In 2017, we decided to re-examine this soft skills curriculum again for two reasons. First, with the publication of the USAID-funded literature reviews described in the introduction, it was clear that the research base around soft skills had developed to the point that it could inform our curriculum development and implementation more clearly than before. And second, we had conducted an initial tracer study of 678 program participants, which did not show the clear correlation that we had expected between completion of the soft skills courses and improved employment outcomes. While the data showed that youth who took our soft skills courses were significantly less likely to be in the inactive NEET Footnote 7 (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) category than their peers who did not take our courses, that difference was largely due to furthering their studies rather than increased rates of employment. This data was non-experimental and so could not determine the direction of causality; additionally, the choice to pursue further studies could reflect one success of the soft skills courses in helping youth evaluate their own skills in relation to market opportunities, determining that they needed some further education/training to find employment. Nevertheless, these findings also suggested a need to re-examine the curriculum, to ensure that it was actually teaching the skills youth most needed in order to find employment in the Algerian context.

Anticipating that this question would affect not only our work in Algeria, but also around the world, we began first by cataloguing all the international research we could find regarding the range of soft skills we should consider to improve youth employment outcomes. We also convened World Learning staff implementing a variety of types of youth programs in different countries to discuss how they selected the soft skills to focus on in a particular context, how they developed curriculum frameworks, what they found to be the most effective pedagogical practices, and how they evaluated instructor pedagogy and student achievements. This process resulted in a set of practitioner-oriented curriculum development tools in a publication titled Soft Skills Development: Guiding Notes for Project and Curriculum Design and Evaluation (Honeyman, 2018 ). These tools included: an inventory of 44 soft skills terms and clusters found in the research we consulted, to aid curriculum designers in making more conscious and specific choices around which skills they intended to build; a checklist of pedagogical practices found to be effective in the research we consulted and in World Learning experience; an example pedagogical observation form for assessing current instructor practices; guidance on creating psychometric or observation-based soft skills assessments; an example observation rubric for assessing student skills; and curriculum framework planning guides for specific skills and for a cluster of skills, among other resources. This toolkit was intended to help World Learning staff design and implement a variety of youth programs around the world in an explicitly context-responsive way.

We next searched for context-specific information on the soft skills needs of youth in Algeria. However, we quickly found that the little information that was available struggled with vague terminology and a lack of clarity in skills definitions, making it difficult to know precisely which skills to teach. With support from the US Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), we therefore designed and undertook qualitative research in Algeria to examine specific contextual needs for soft skills, as well as examine what the existing soft skills courses were achieving and where there may be gaps (Honeyman, 2019 ). This research included re-analyzing qualitative interview data with 140 employers and other stakeholders from nine local labor market assessments we had conducted (Farrand, 2019 ). It also involved new individual questionnaires and focus group discussions with stratified groups of 90 Algerian youth beneficiaries of our program—male and female, employed and unemployed—in six governorates. We asked youth to describe personal weaknesses that had hindered them in their job search, as well as contextual obstacles they faced, and they shared their own theories regarding the major differences between youth who had and had not succeeded in finding employment.