How Much Time Do College Students Spend on Homework

by Jack Tai | Oct 9, 2019 | Articles

Does college life involve more studying or socializing?

Find out how much time college students need to devote to their homework in order to succeed in class.

We all know that it takes hard work to succeed in college and earn top grades.

To find out more about the time demands of studying and learning, let’s review the average homework amounts of college students.

HowtoLearn.com expert, Jack Tai, CEO of OneClass.com shows how homework improves grades in college and an average of how much time is required.

How Many Hours Do College Students Spend on Homework?

Classes in college are much different from those in high school.

For students in high school, a large part of learning occurs in the classroom with homework used to support class activities.

One of the first thing that college students need to learn is how to read and remember more quickly. It gives them a competitive benefit in their grades and when they learn new information to escalate their career.

Taking a speed reading course that shows you how to learn at the same time is one of the best ways for students to complete their reading assignments and their homework.

However, in college, students spend a shorter period in class and spend more time learning outside of the classroom.

This shift to an independent learning structure means that college students should expect to spend more time on homework than they did during high school.

In college, a good rule of thumb for homework estimates that for each college credit you take, you’ll spend one hour in the classroom and two to three hours on homework each week.

These homework tasks can include readings, working on assignments, or studying for exams.

Based upon these estimates, a three-credit college class would require each week to include approximately three hours attending lectures and six to nine hours of homework.

Extrapolating this out to the 15-credit course load of a full-time student, that would be 15 hours in the classroom and 30 to 45 hours studying and doing homework.

These time estimates demonstrate that college students have significantly more homework than the 10 hours per week average among high school students. In fact, doing homework in college can take as much time as a full-time job.

Students should keep in mind that these homework amounts are averages.

Students will find that some professors assign more or less homework. Students may also find that some classes assign very little homework in the beginning of the semester, but increase later on in preparation for exams or when a major project is due.

There can even be variation based upon the major with some areas of study requiring more lab work or reading.

Do College Students Do Homework on Weekends?

Based on the quantity of homework in college, it’s nearly certain that students will be spending some of their weekends doing homework.

For example, if each weekday, a student spends three hours in class and spends five hours on homework, there’s still at least five hours of homework to do on the weekend.

When considering how homework schedules can affect learning, it’s important to remember that even though college students face a significant amount of homework, one of the best learning strategies is to space out study sessions into short time blocks.

This includes not just doing homework every day of the week, but also establishing short study blocks in the morning, afternoon, and evening. With this approach, students can avoid cramming on Sunday night to be ready for class.

What’s the Best Way to Get Help with Your Homework?

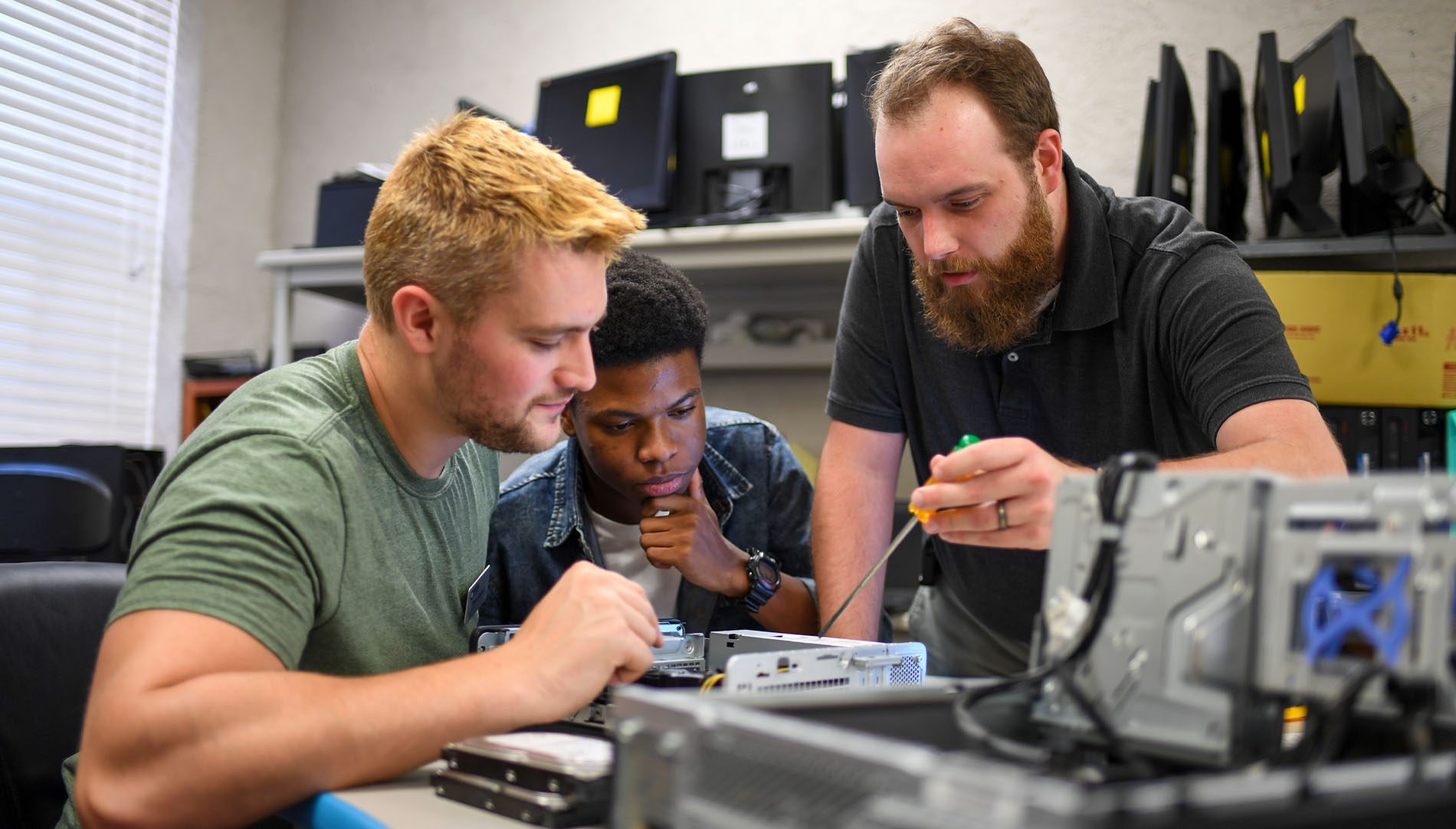

In college, there are academic resources built into campus life to support learning.

For example, you may have access to an on-campus learning center or tutoring facilities. You may also have the support of teaching assistants or regular office hours.

That’s why OneClass recommends a course like How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It which gives a c hoice to support your learning.

Another choice is on demand tutoring.

They send detailed, step-by-step solutions within just 24 hours, and frequently, answers are sent in less than 12 hours.

When students have on-demand access to homework help, it’s possible to avoid the poor grades that can result from unfinished homework.

Plus, 24/7 Homework Help makes it easy to ask a question. Simply snap a photo and upload it to the platform.

That’s all tutors need to get started preparing your solution.

Rather than retyping questions or struggling with math formulas, asking questions and getting answers is as easy as click and go.

Homework Help supports coursework for both high school and college students across a wide range of subjects. Moreover, students can access OneClass’ knowledge base of previously answered homework questions.

Simply browse by subject or search the directory to find out if another student struggled to learn the same class material.

Related articles

NEW COURSE: How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It

Call for Entries Parent and Teacher Choice Awards. Winners Featured to Over 2 Million People

All About Reading-Comprehensive Instructional Reading Program

Parent & Teacher Choice Award Winner – Letter Tracing for Kids

Parent and Teacher Choice Award Winner – Number Tracing for Kids ages 3-5

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Kids

One Minute Gratitude Journal

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Teens

Make Teaching Easier! 1000+ Images, Stories & Activities

Prodigy Math and English – FREE Math and English Skills

Recent Posts

- 5 Essential Techniques to Teach Sight Words to Children

- 7 Most Common Reading Problems and How to Fix Them

- Best Program for Struggling Readers

- 21 Interactive Reading Strategies for Pre-Kindergarten

- 27 Education Storybook Activities to Improve Literacy

Recent Comments

- Glenda on How to Teach Spelling Using Phonics

- Dorothy on How to Tell If You Are an Employee or Entrepreneur

- Pat Wyman on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- kapenda chibanga on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- Jennifer Dean on 9 Proven Ways to Learn Anything Faster

College Homework: What You Need to Know

- April 1, 2020

Samantha "Sam" Sparks

- Future of Education

Despite what Hollywood shows us, most of college life actually involves studying, burying yourself in mountains of books, writing mountains of reports, and, of course, doing a whole lot of homework.

Wait, homework? That’s right, homework doesn’t end just because high school did: part of parcel of any college course will be homework. So if you thought college is harder than high school , then you’re right, because in between hours and hours of lectures and term papers and exams, you’re still going to have to take home a lot of schoolwork to do in the comfort of your dorm.

College life is demanding, it’s difficult, but at the end of the day, it’s fulfilling. You might have had this idealized version of what your college life is going to be like, but we’re here to tell you: it’s not all parties and cardigans.

How Many Hours Does College Homework Require?

Here’s the thing about college homework: it’s vastly different from the type of takehome school activities you might have had in high school.

See, high school students are given homework to augment what they’ve learned in the classroom. For high school students, a majority of their learning happens in school, with their teachers guiding them along the way.

In college, however, your professors will encourage you to learn on your own. Yes, you will be attending hours and hours of lectures and seminars, but most of your learning is going to take place in the library, with your professors taking a more backseat approach to your learning process. This independent learning structure teaches prospective students to hone their critical thinking skills, perfect their research abilities, and encourage them to come up with original thoughts and ideas.

Sure, your professors will still step in every now and then to help with anything you’re struggling with and to correct certain mistakes, but by and large, the learning process in college is entirely up to how you develop your skills.

This is the reason why college homework is voluminous: it’s designed to teach you how to basically learn on your own. While there is no set standard on how much time you should spend doing homework in college, a good rule-of-thumb practiced by model students is 3 hours a week per college credit . It doesn’t seem like a lot, until you factor in that the average college student takes on about 15 units per semester. With that in mind, it’s safe to assume that a single, 3-unit college class would usually require 9 hours of homework per week.

But don’t worry, college homework is also different from high school homework in how it’s structured. High school homework usually involves a take-home activity of some kind, where students answer certain questions posed to them. College homework, on the other hand, is more on reading texts that you’ll discuss in your next lecture, studying for exams, and, of course, take-home activities.

Take these averages with a grain of salt, however, as the average number of hours required to do college homework will also depend on your professor, the type of class you’re attending, what you’re majoring in, and whether or not you have other activities (like laboratory work or field work) that would compensate for homework.

Do Students Do College Homework On the Weekends?

Again, based on the average number we provided above, and again, depending on numerous other factors, it’s safe to say that, yes, you would have to complete a lot of college homework on the weekends.

Using the average given above, let’s say that a student does 9 hours of homework per week per class. A typical semester would involve 5 different classes (each with 3 units), which means that a student would be doing an average of 45 hours of homework per week. That would equal to around 6 hours of homework a day, including weekends.

That might seem overwhelming, but again: college homework is different from high school homework in that it doesn’t always involve take-home activities. In fact, most of your college homework (but again, depending on your professor, your major, and other mitigating factors) will probably involve doing readings and writing essays. Some types of college homework might not even feel like homework, as some professors encourage inter-personal learning by requiring their students to form groups and discuss certain topics instead of doing take-home activities or writing papers. Again, lab work and field work (depending on your major) might also make up for homework.

Remember: this is all relative. Some people read fast and will find that 3 hours per unit per week is much too much time considering they can finish a reading in under an hour.The faster you learn how to read, the less amount of time you’ll need to devote to homework.

College homework is difficult, but it’s also manageable. This is why you see a lot of study groups in college, where your peers will establish a way for everyone to learn on a collective basis, as this would help lighten the mental load you might face during your college life. There are also different strategies you can develop to master your time management skills, all of which will help you become a more holistic person once you leave college.

So, yes, your weekends will probably be chock-full of schoolwork, but you’ll need to learn how to manage your time in such a way that you’ll be able to do your homework and socialize, but also have time to develop your other skills and/or talk to family and friends.

College Homework Isn’t All That Bad, Though

Sure, you’ll probably have time for parties and joining a fraternity/sorority, even attend those mythical college keggers (something that the person who invented college probably didn’t have in mind). But I hate to break it to you: those are going to be few and far in between. But here’s a consolation, however: you’re going to be studying something you’re actually interested in.

All of those hours spent in the library, writing down papers, doing college homework? It’s going to feel like a minute because you’re doing something you actually love doing. And if you fear that you’ll be missing out, don’t worry: all those people that you think are attending those parties aren’t actually there because they, too, will be busy studying!

About the Author

News & Updates

Top college majors for any aspiring doctor or healthcare worker, 3 ways summer camps benefit the growth and development of your child, 10 career paths you can take when in college.

How Much Homework is Too Much?

When redesigning a course or putting together a new course, faculty often struggle with how much homework and readings to assign. Too little homework and students might not be prepared for the class sessions or be able to adequately practice basic skills or produce sufficient in-depth work to properly master the learning goals of the course. Too much and some students may feel overwhelmed and find it difficult to keep up or have to sacrifice work in other courses.

A common rule of thumb is that students should study three hours for each credit hour of the course, but this isn’t definitive. Universities might recommend that students spend anywhere from two or three hours of study or as much as six to nine hours of study or more for each course credit hour. A 2014 study found that, nationwide, college students self reported spending about 17 hours each week on homework, reading and assignments. Studies of high school students show that too much homework can produce diminishing returns on student learning, so finding the right balance can be difficult.

There are no hard and fast rules about the amount of readings and homework that faculty assign. It will vary according to the university, the department, the level of the classes, and even other external factors that impact students in your course. (Duke’s faculty handbook addresses many facets of courses, such as absences, but not the typical amount of homework specifically.)

To consider the perspective of a typical student that might be similar to the situations faced at Duke, Harvard posted a blog entry by one of their students aimed at giving students new to the university about what they could expect. There are lots of readings, of course, but time has to be spent on completing problem sets, sometimes elaborate multimedia or research projects, responding to discussion posts and writing essays. Your class is one of several, and students have to balance the needs of your class with others and with clubs, special projects, volunteer work or other activities they’re involved with as part of their overall experience.

The Rice Center for Teaching Excellence has some online calculators for estimating class workload that can help you get a general understanding of the time it may take for a student to read a particular number of pages of material at different levels or to complete essays or other types of homework.

To narrow down your decision-making about homework when redesigning or creating your own course, you might consider situational factors that may influence the amount of homework that’s appropriate.

Connection with your learning goals

Is the homework clearly connected with the learning goals of your students for a particular class session or week in the course? Students will find homework beneficial and valuable if they feel that it is meaningful . If you think students might see readings or assignments as busy work, think about ways to modify the homework to make a clearer connection with what is happening in class. Resist the temptation to assign something because the students need to know it. Ask yourself if they will actually use it immediately in the course or if the material or exercises should be relegated to supplementary material.

Levels of performance

The type of readings and homework given to first year students will be very different from those given to more experienced individuals in higher-level courses. If you’re unsure if your readings or other work might be too easy (or too complex) for students in your course, ask a colleague in your department or at another university to give feedback on your assignment. If former students in the course (or a similar course) are available, ask them for feedback on a sample reading or assignment.

Common practices

What are the common practices in your department or discipline? Some departments, with particular classes, may have general guidelines or best practices you can keep in mind when assigning homework.

External factors

What type of typical student will be taking your course? If it’s a course preparing for a major or within an area of study, are there other courses with heavy workloads they might be taking at the same time? Are they completing projects, research, or community work that might make it difficult for them to keep up with a heavy homework load for your course?

Students who speak English as a second language, are first generation students, or who may be having to work to support themselves as they take courses may need support to get the most out of homework. Detailed instructions for the homework, along with outlining your learning goals and how the assignment connects the course, can help students understand how the readings and assignments fit into their studies. A reading guide, with questions prompts or background, can help students gain a better understanding of a reading. Resources to look up unfamiliar cultural references or terms can make readings and assignments less overwhelming.

If you would like more ideas about planning homework and assignments for your course or more information and guidance on course design and assessment, contact Duke Learning Innovation to speak with one of our consultants .

How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

- Share article

Editor’s note: This is an adapted excerpt from You, Your Child, and School: Navigate Your Way to the Best Education ( Viking)—the latest book by author and speaker Sir Ken Robinson (co-authored with Lou Aronica), published in March. For years, Robinson has been known for his radical work on rekindling creativity and passion in schools, including three bestselling books (also with Aronica) on the topic. His TED Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” holds the record for the most-viewed TED talk of all time, with more than 50 million views. While Robinson’s latest book is geared toward parents, it also offers educators a window into the kinds of education concerns parents have for their children, including on the quality and quantity of homework.

The amount of homework young people are given varies a lot from school to school and from grade to grade. In some schools and grades, children have no homework at all. In others, they may have 18 hours or more of homework every week. In the United States, the accepted guideline, which is supported by both the National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association, is the 10-minute rule: Children should have no more than 10 minutes of homework each day for each grade reached. In 1st grade, children should have 10 minutes of daily homework; in 2nd grade, 20 minutes; and so on to the 12th grade, when on average they should have 120 minutes of homework each day, which is about 10 hours a week. It doesn’t always work out that way.

In 2013, the University of Phoenix College of Education commissioned a survey of how much homework teachers typically give their students. From kindergarten to 5th grade, it was just under three hours per week; from 6th to 8th grade, it was 3.2 hours; and from 9th to 12th grade, it was 3.5 hours.

There are two points to note. First, these are the amounts given by individual teachers. To estimate the total time children are expected to spend on homework, you need to multiply these hours by the number of teachers they work with. High school students who work with five teachers in different curriculum areas may find themselves with 17.5 hours or more of homework a week, which is the equivalent of a part-time job. The other factor is that these are teachers’ estimates of the time that homework should take. The time that individual children spend on it will be more or less than that, according to their abilities and interests. One child may casually dash off a piece of homework in half the time that another will spend laboring through in a cold sweat.

Do students have more homework these days than previous generations? Given all the variables, it’s difficult to say. Some studies suggest they do. In 2007, a study from the National Center for Education Statistics found that, on average, high school students spent around seven hours a week on homework. A similar study in 1994 put the average at less than five hours a week. Mind you, I [Robinson] was in high school in England in the 1960s and spent a lot more time than that—though maybe that was to do with my own ability. One way of judging this is to look at how much homework your own children are given and compare it to what you had at the same age.

Many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all.

There’s also much debate about the value of homework. Supporters argue that it benefits children, teachers, and parents in several ways:

- Children learn to deepen their understanding of specific content, to cover content at their own pace, to become more independent learners, to develop problem-solving and time-management skills, and to relate what they learn in school to outside activities.

- Teachers can see how well their students understand the lessons; evaluate students’ individual progress, strengths, and weaknesses; and cover more content in class.

- Parents can engage practically in their children’s education, see firsthand what their children are being taught in school, and understand more clearly how they’re getting on—what they find easy and what they struggle with in school.

Want to know more about Sir Ken Robinson? Check out our Q&A with him.

Q&A With Sir Ken Robinson

Ashley Norris is assistant dean at the University of Phoenix College of Education. Commenting on her university’s survey, she says, “Homework helps build confidence, responsibility, and problem-solving skills that can set students up for success in high school, college, and in the workplace.”

That may be so, but many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all. Families have busy lives, and it can be hard for parents to find time to help with homework alongside everything else they have to cope with. Norris is convinced it’s worth the effort, especially, she says, because in many schools, the nature of homework is changing. One influence is the growing popularity of the so-called flipped classroom.

In the stereotypical classroom, the teacher spends time in class presenting material to the students. Their homework consists of assignments based on that material. In the flipped classroom, the teacher provides the students with presentational materials—videos, slides, lecture notes—which the students review at home and then bring questions and ideas to school where they work on them collaboratively with the teacher and other students. As Norris notes, in this approach, homework extends the boundaries of the classroom and reframes how time in school can be used more productively, allowing students to “collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique [each other’s work], and share those experiences.”

Even so, many parents and educators are increasingly concerned that homework, in whatever form it takes, is a bridge too far in the pressured lives of children and their families. It takes away from essential time for their children to relax and unwind after school, to play, to be young, and to be together as a family. On top of that, the benefits of homework are often asserted, but they’re not consistent, and they’re certainly not guaranteed.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Course Workload Estimator

A blog post that describes the genesis of this estimator, as well as some of its potential uses, can be read here . You can also find a stand-alone version of the estimator that can be embedded into your site here .

Estimation Details

Somewhat surprisingly, there is very little research about the amount of time it takes the average college student to complete common academic tasks. We have self-reported estimates of how much total time they spend on academic work outside of class (12-15 hours), but we don't know much about the quality and quantity of the work that is produced in that time frame (let alone how the time is allocated to different tasks). We also know quite a bit about how students tackle common academic tasks , but those studies rarely ask students to report on how long it takes them to complete the task (whether reading a book, writing a paper, or studying for an exam). The testing literature provides some clues (because valid instrument design depends on data about the average speed of test takers), but it's tough to generalize from the experience of taking high-stakes, timed tests to the experience of working on an assignment in the comfort of your dorm. And while there is a sizable literature on reading, the nature and purpose of the reading tasks in these experiments are also quite different from what students typically encounter in college.

All of which is to say the estimates above are just that: estimates .

To arrive at our estimates, we began with what we knew from the literature and then filled in the gaps by making a few key assumptions. The details of our calculations are below. If you still find our assumptions unreasonable, however, the estimator allows you to manually adjust our estimated rates. We also welcome those who have knowledge of research about which we are unaware to suggest improvements.

Reading Rates

Of all the work students might do outside of class, we know the most about their reading. Educators, cognitive psychologists, and linguists have been studying how human beings read for more than a century. One of the best summaries of this extensive literature is the late Keith Rayner's recently published " So Much to Read, So Little Time: How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help? " A central insight of this piece (along with the literature it summarizes) is that none of us read at a constant rate. Instead, we use varying rates that depend on the difficulty and purpose of the reading task (Rayner et al., 2016; Love, 2012; Aronson, 1983; Carver, 1983, 1992; Jay and Dahl, 1975; Parker, 1962; Carrillo and Sheldon, 1952; Robinson, 1941). Another obvious (but rarely acknowledged) insight is that a page-based reading rate is going to vary by the number of words on the page. As a result, our estimator assumes that reading rate will be a function of three factors: 1) page density, 2) text difficulty, and 3) reading purpose. For the sake of simplicity, we limited the variation within each factor to three levels.

Page Density*

- 450 words: Typical of paperback pages, as well as the 6" x 9" pages of academic journal articles

- 600 words: Typical of academic monograph pages

- 750 words: Typical of textbook pages that are 25% images, as well as the full-size pages of two-column academic journal articles

* estimates were determined by direct sampling of texts in our personal collection

Text Difficulty

- No New Concepts: The reader knows the meaning of each word and has enough background knowledge to immediately understand the ideas expressed

- Some New Concepts: The reader is unfamiliar with the meaning of some words and doesn't have enough background knowledge to immediately understand some of the ideas expressed.

- Many New Concepts: The reader is unfamiliar with the meaning of many words and doesn't have enough background knowledge to immediately understand most of the ideas expressed

Reading Purpose

- Survey: Reading to survey main ideas; OK to skip entire portions of text

- Understand: Reading to understand the meaning of each sentence

- Engage: Reading while also working problems, drawing inferences, questioning, and evaluating

What we know from the research:

The optimal reading rate of the skilled adult reader (including college students) is around 300 words per minute. This assumes a "normal" reading environment in which there are no new words or concepts in the text and the purpose of the reading is to understand the meaning of each sentence (Rayner et al., 2016; Carver, 1982).

Adults can read faster than 300 words per minute, but if the goal is to understand the meaning of sentences, rates beyond 300 words per minute reduce comprehension in a near linear fashion (Zacks and Treiman, 2016; Love, 2012; Carver, 1982).

The default reading rates of college students under these normal conditions can range from 100-400 words per minute (Rayner et al., 2016; Siegenthaler et al., 2011; Acheson et al., 2008; Carver, 1982, 1983, 1992; Underwood et al., 1990; Hausfeld, 1981; Just and Carpenter, 1980; Jay and Dahl, 1975; Grob, 1970; McLaughlin, 1969; Robinson and Hall, 1941).

There is no real upper limit on skimming speeds, but the average college student skims for main ideas at rates between 450 and 600 words per minute (Rayner et al., 2016; Carver 1992; Just and Carpenter, 1980; Jay and Dahl, 1975)

In conditions where the material is more difficult (i.e., with some new words and concepts), the optimal reading rate slows to 200 words per minute (Carver, 1992).

In conditions where the purpose is to memorize the text for later recall, the optimal reading rate slows even further to 138 words per minute or lower (Carver, 1992).

Although this has not been measured (to our knowledge), reading experts have argued that it is perfectly reasonable to slow down to rates below 50 words per minute if the goal is to engage a text (Parker, 1962).

What we don't know, but deduce and/or stipulate:

Given that the rates above were discovered in laboratory conditions, when subjects are asked to perform in short, time-constrained intervals, we assume that the reading rates in actual conditions, when students read for longer periods with periodic breaks, will be slightly slower.

Because there is no research on the time it takes students to engage texts, we assume that the rates would be similar to the rates found when students are asked to memorize a text for later recall. Although these are incredibly different tasks, both require attention to details alongside additional processing. If anything, we imagine equating these two rates significantly under estimates the time it takes to read for engagement (for an example of the sort of reading that is likely to take more time than it takes to memorize, see the appendix of Perry et al., 2015).

If the reading purpose remains the same, the change in reading rates across text difficulty levels is linear.

The rate of change in reading rates across text difficulty levels is the same across reading purposes.

Combining what we know with what we assume allows us to construct the following table of estimated reading rates (with rates about which we are most confident in yellow):

Writing Rates

Sadly, we know much less about student writing rates than we do about reading rates. This is no doubt because writing rates vary even more widely than reading rates. Nevertheless, we've found at least one study that can give us a place to begin. In " Individual Differences in Undergraduate Essay-Writing Strategies ," Mark Torrance and his colleagues find (among other things) that 493 students reported spending anywhere between 9 to 15 hours on 1500-word essays. In these essays, students were asked to produce a "critical description and discussion of psychological themes" using at least one outside source. Torrance and his colleagues also show that students who spent the least time reported no drafting, while those who spent the most time reported multiple drafts, along with detailed outlining and planning. And the students who spent the most time received higher marks than those who spent the least (Torrance et al., 2000).

Although the sample of this study is sizable, we should not read too much into a single result of student self-reports about a single assignment from a single institution. But to arrive at our estimates, we must. Users should simply be aware that the table below is far more speculative than our reading rate estimates. And that the time your students spend on these tasks is likely to vary from these estimates in significant ways.

As with reading rates, we assume that writing rates will be a function of a variety of factors. The three we take into account are 1) page density, 2) text genre, 3) degree of drafting and revision.

Page Density

- 250 words: Double-Spaced, Times New Roman, 12-Point Font, 1" Margins

- 500 words: Single-Spaced, Times New Roman, 12-Point Font, 1" Margins

- Reflection/Narrative: Essays that require very little planning or critical engagement with content

- Argument: Essays that require critical engagement with content and detailed planning, but no outside research

- Research: Essays that require detailed planning, outside research, and critical engagement

Drafting and Revision

- No Drafting: Students submit essays that were never revised

- Minimal Drafting: Students submit essays that were revised at least once

- Extensive Drafting: Students submit essays that were revised multiple times

What we assume to arrive at our estimates:

- The results of the Torrance study are reasonably accurate.

- The assignment in the study falls within the "argument" genre. It's hard to tell without more details, but "critical description and discussion" seems to imply more than reflection. And while an outside source was required, finding and using a single source falls well below the expectations of a traditional research paper.

- Students write at a constant rate. That is, we assume that a student writing the same sort of essay will take exactly twice as much time to write a 12 page paper as she takes to write a 6 page paper. There are good reasons to think this assumption is unrealistic, but because we have no way of knowing how much rate might shift over the course of a paper, we assume constancy.

- Students will spend less time writing a reflective or narrative essay than they spend constructing an argumentative essay (assuming the same degree of drafting and revision). For simplicity's sake, we assume they will spend exactly half the time. It's highly unlikely to be this linear, but we don't know enough to make a more accurate assumption.

- Students will spend more time writing a research paper than they spend on their argumentative essays. Again, for simplicity's sake, we assume they will spend exactly twice the amount of time. It's not only unlikely to be this linear, it's also likely to vary greatly by the amount of outside reading a student does and the difficulty of the sources he or she tackles.

These assumptions allow us to construct the following table of estimated writing rates (with rates about which we are most confident in yellow):

Bibliography

Aaronson, Doris, and Steven Ferres. “Lexical Categories and Reading Tasks.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 9, no. 5 (1983): 675–99. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.9.5.675.

Acheson, Daniel J., Justine B. Wells, and Maryellen C. MacDonald. “New and Updated Tests of Print Exposure and Reading Abilities in College Students.” Behavior Research Methods 40, no. 1 (2008): 278–89. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.1.278.

Carrillo, Lawrence W., and William D. Sheldon. “The Flexibility of Reading Rate.” Journal of Educational Psychology 43, no. 5 (1952): 299–305. doi:10.1037/h0054161.

Carver, Ronald P. “Is Reading Rate Constant or Flexible?” Reading Research Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1983): 190–215. doi:10.2307/747517.

———. “Optimal Rate of Reading Prose.” Reading Research Quarterly 18, no. 1 (1982): 56–88. doi:10.2307/747538.

———. “Reading Rate: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications.” Journal of Reading 36, no. 2 (1992): 84–95.

Dehaene, Stanislas. Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read . Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.

Grob, James A. “Reading Rate and Study-Time Demands on Secondary Students.” Journal of Reading 13, no. 4 (1970): 285–88.

Hausfeld, Steven. “Speeded Reading and Listening Comprehension for Easy and Difficult Materials.” Journal of Educational Psychology 73, no. 3 (1981): 312–19. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.73.3.312.

Jay, S., and Patricia R. Dahl. “Establishing Appropriate Purpose for Reading and Its Effect on Flexibility of Reading Rate.” Journal of Educational Psychology 67, no. 1 (1975): 38–43. doi:10.1037/h0078669.

Just, Marcel A., and Patricia A. Carpenter. “A Theory of Reading: From Eye Fixations to Comprehension.” Psychological Review 87, no. 4 (1980): 329–54. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.4.329.

Love, Jessica. “ Reading Fast and Slow .” The American Scholar , March 1, 2012.

McLaughlin, G. Harry. “Reading at ‘Impossible’ Speeds.” Journal of Reading 12, no. 6 (1969): 449–510.

Parker, Don H. “Reading Rate Is Multilevel.” The Clearing House 36, no. 8 (1962): 451–55.

Perry, John, Michael Bratman, and John Martin Fischer. “ Appendix: Reading Philosophy .” In Introduction to Philosophy: Classical and Contemporary Readings , 7 edition. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Rayner, Keith, Elizabeth R. Schotter, Michael E. J. Masson, Mary C. Potter, and Rebecca Treiman. “So Much to Read, So Little Time How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help?” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 17, no. 1 (May 1, 2016): 4–34. doi:10.1177/1529100615623267.

Robinson, F., and P. Hall. “Studies of Higher-Level Reading Abilities.” Journal of Educational Psychology 32, no. 4 (1941): 241–52. doi:10.1037/h0062111.

Siegenthaler, Eva, Pascal Wurtz, Per Bergamin, and Rudolf Groner. “Comparing Reading Processes on E-Ink Displays and Print.” Displays 32, no. 5 (December 2011): 268–73. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2011.05.005.

Torrance, Mark, Glyn V. Thomas, and Elizabeth J. Robinson. “Individual Differences in Undergraduate Essay-Writing Strategies: A Longitudinal Study.” Higher Education 39, no. 2 (2000): 181–200.

Underwood, Geoffrey, Alison Hubbard, and Howard Wilkinson. “Eye Fixations Predict Reading Comprehension: The Relationships between Reading Skill, Reading Speed, and Visual Inspection.” Language and Speech 33, no. 1 (January 1, 1990): 69–81.

Wolf, Maryanne. Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . Reprint edition. New York: Harper Perennial, 2008.

Zacks, Jeffrey M., and Rebecca Treiman. “ Sorry, You Can’t Speed Read .” The New York Times , April 15, 2016.

- College Prep & Testing

- College Search

- Applications & Admissions

- Alternatives to 4-Year College

- Orientation & Move-In

- Campus Involvement

- Campus Resources

- Homesickness

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Transferring

- Residential Life

- Finding an Apartment

- Off-Campus Life

- Mental Health

- Alcohol & Drugs

- Relationships & Sexuality

- COVID-19 Resources

- Paying for College

- Banking & Credit

- Success Strategies

- Majors & Minors

- Study Abroad

- Diverse Learners

- Online Education

- Internships

- Career Services

- Graduate School

- Graduation & Celebrations

- First Generation

- Shop for College

- Academics »

Student Study Time Matters

Vicki nelson.

Most college students want to do well, but they don’t always know what is required to do well. Finding and spending quality study time is one of the first and most important skills that your student can master, but it's rarely as simple as it sounds.

If a student is struggling in class, one of the first questions I ask is, “How much time do you spend studying?”

Although it’s not the only element, time spent studying is one of the basics, so it’s a good place to start. Once we examine time, we can move on to other factors such as how, where, what and when students are studying, but we start with time .

If your student is struggling , help them explore how much time they are spending on schoolwork.

How Much Is Enough?

Very often, a student’s answer to how much time they spend hitting the books doesn’t match the expectation that most professors have for college students. There’s a disconnect about “how much is enough?”

Most college classes meet for a number of “credit hours” – typically 3 or 4. The general rule of thumb (and the definition of credit hour adopted by the Department of Education) is that students should spend approximately 2–3 hours on outside-of-class work for each credit hour or hour spent in the classroom.

Therefore, a student taking five 3-credit classes spends 15 hours each week in class and should be spending 30 hours on work outside of class , or 45 hours/week total.

When we talk about this, I can see on students’ faces that for most of them this isn’t even close to their reality!

According to one survey conducted by the National Survey of Student Engagement, most college students spend an average of 10–13 hours/week studying, or less than 2 hours/day and less than half of what is expected. Only about 11% of students spend more than 25 hours/week on schoolwork.

Why Such a Disconnect?

Warning: math ahead!

It may be that students fail to do the math – or fail to flip the equation.

College expectations are significantly different from the actual time that most high school students spend on outside-of-school work, but the total picture may not be that far off. In order to help students understand, we crunch some more numbers.

Most high school students spend approximately 6 hours/day or 30 hours/week in school. In a 180 day school year, students spend approximately 1,080 hours in school. Some surveys suggest that the average amount of time that most high school students spend on homework is 4–5 hours/week. That’s approximately 1 hour/day or 180 hours/year. So that puts the average time spent on class and homework combined at 1,260 hours/school year.

Now let’s look at college: Most semesters are approximately 15 weeks long. That student with 15 credits (5 classes) spends 225 hours in class and, with the formula above, should be spending 450 hours studying. That’s 675 hours/semester or 1,350 for the year. That’s a bit more than the 1,260 in high school, but only 90 hours, or an average of 3 hours more/week.

The problem is not necessarily the number of hours, it's that many students haven’t flipped the equation and recognized the time expected outside of class.

In high school, students’ 6-hour school day was not under their control but they did much of their work during that time. That hour-or-so a day of homework was an add-on. (Some students definitely spend more than 1 hour/day, but we’re looking at averages.)

In college, students spend a small number of hours in class (approximately 15/week) and are expected to complete almost all their reading, writing and studying outside of class. The expectation doesn’t require significantly more hours; the hours are simply allocated differently – and require discipline to make sure they happen. What students sometimes see as “free time” is really just time that they are responsible for scheduling themselves.

Help Your Student Adjust to College Academics >

How to Fit It All In?

Once we look at these numbers, the question that students often ask is, “How am I supposed to fit that into my week? There aren’t enough hours!”

Again: more math.

I remind students that there are 168 hours in a week. If a student spends 45 hours on class and studying, that leaves 123 hours. If the student sleeps 8 hours per night (few do!), that’s another 56 hours which leaves 67 hours, or at least 9.5 hours/day for work or play.

Many colleges recommend that full-time students should work no more than 20 hours/week at a job if they want to do well in their classes and this calculation shows why.

Making It Work

Many students may not spend 30 or more hours/week studying, but understanding what is expected may motivate them to put in some additional study time. That takes planning, organizing and discipline. Students need to be aware of obstacles and distractions (social media, partying, working too many hours) that may interfere with their ability to find balance.

What Can My Student Do?

Here are a few things your student can try.

- Start by keeping a time journal for a few days or a week . Keep a log and record what you are doing each hour as you go through your day. At the end of the week, observe how you have spent your time. How much time did you actually spend studying? Socializing? Sleeping? Texting? On social media? At a job? Find the “time stealers.”

- Prioritize studying. Don’t hope that you’ll find the time. Schedule your study time each day – make it an appointment with yourself and stick to it.

- Limit phone time. This isn’t easy. In fact, many students find it almost impossible to turn off their phones even for a short time. It may take some practice but putting the phone away during designated study time can make a big difference in how efficient and focused you can be.

- Spend time with friends who study . It’s easier to put in the time when the people around you are doing the same thing. Find an accountability partner who will help you stay on track.

- If you have a job, ask if there is any flexibility with shifts or responsibilities. Ask whether you can schedule fewer shifts at prime study times like exam periods or when a big paper or project is due. You might also look for an on-campus job that will allow some study time while on the job. Sometimes working at a computer lab, library, information or check-in desk will provide down time. If so, be sure to use it wisely.

- Work on strengthening your time management skills. Block out study times and stick to the plan. Plan ahead for long-term assignments and schedule bite-sized pieces. Don’t underestimate how much time big assignments will take.

Being a full-time student is a full-time job. Start by looking at the numbers with your student and then encourage them to create strategies that will keep them on task.

With understanding and practice, your student can plan for and spend the time needed to succeed in college.

Get stories and expert advice on all things related to college and parenting.

Table of Contents

- Rhythm of the First Semester

- Tips from a Student on Making It Through the First Year

- Who Is Your First‑Year Student?

- Campus Resources: Your Cheat Sheet

- Handling Roommate Issues

- Study Time Matters

- The Importance of Professors and Advisors

- Should My Student Withdraw from a Difficult Course?

- Essential Health Conversations

- A Mental Health Game Plan for College Students and Families

- Assertiveness is the Secret Sauce

- Is Your Student at Risk for an Eating Disorder?

- Learning to Manage Money

- 5 Ways to Begin Career Prep in the First Year

- The Value of Outside Opportunities

Housing Timeline

Don't Miss Out!

Get engaging stories and helpful information all year long. Join our college parent newsletter!

Powerful Personality Knowledge: How Extraverts and Introverts Learn Differently

College Preparedness: Recovering from the Pandemic

How much time should you spend studying? Our ‘Goldilocks Day’ tool helps find the best balance of good grades and well-being

Senior Research Fellow, Allied Health & Human Performance, University of South Australia

Professor of Health Sciences, University of South Australia

Disclosure statement

Dot Dumuid is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship GNT1162166 and by the Centre of Research Excellence in Driving Global Investment in Adolescent Health funded by NHMRC GNT1171981.

Tim Olds receives funding from the NHMRC and the ARC.

University of South Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

For students, as for all of us, life is a matter of balance, trade-offs and compromise. Studying for hours on end is unlikely to lead to best academic results. And it could have negative impacts on young people’s physical, mental and social well-being.

Our recent study found the best way for young people to spend their time was different for mental health than for physical health, and even more different for school-related outcomes. Students needed to spend more time sitting for best cognitive and academic performance, but physical activity trumped sitting time for best physical health. For best mental health, longer sleep time was most important.

It’s like a game of rock, paper, scissors with time use. So, what is the sweet spot, or as Goldilocks put it, the “just right” amount of study?

Read more: Back to school: how to help your teen get enough sleep

Using our study data for Australian children aged 11 and 12, we are developing a time-optimisation tool that allows the user to define their own mental, physical and cognitive health priorities. Once the priorities are set, the tool provides real-time updates on what the user’s estimated “Goldilocks day” looks like.

More study improves grades, but not as much as you think

Over 30 years of research shows that students doing more homework get better grades. However, extra study doesn’t make as much difference as people think. An American study found the average grades of high school boys increased by only about 1.5 percentage points for every extra hour of homework per school night.

What these sorts of studies don’t consider is that the relationship between time spent doing homework and academic achievement is unlikely to be linear. A high school boy doing an extra ten hours of homework per school night is unlikely to improve his grades by 15 percentage points.

There is a simple explanation for this: doing an extra ten hours of homework after school would mean students couldn’t go to bed until the early hours of the morning. Even if they could manage this for one day, it would be unsustainable over a week, let alone a month. In any case, adequate sleep is probably critical for memory consolidation .

Read more: What's the point of homework?

As we all know, there are only 24 hours in a day. Students can’t devote more time to study without taking this time from other parts of their day. Excessive studying may become detrimental to learning ability when too much sleep time is lost.

Another US study found that, regardless of how long a student normally spent studying, sacrificing sleep to fit in more study led to learning problems on the following day. Among year 12s, cramming in an extra three hours of study almost doubled their academic problems. For example, students reported they “did not understand something taught in class” or “did poorly on a test, quiz or homework”.

Excessive study could also become unhelpful if it means students don’t have time to exercise. We know exercise is important for young people’s cognition , particularly their creative thinking, working memory and concentration.

On the one hand, then, more time spent studying is beneficial for grades. On the other hand, too much time spent studying is detrimental to grades.

We have to make trade-offs

Of course, how young people spend their time is not only important to their academic performance, but also to their health. Because what is the point of optimising school grades if it means compromising physical, mental and social well-being? And throwing everything at academic performance means other aspects of health will suffer.

US sleep researchers found the ideal amount of sleep for for 15-year-old boys’ mental health was 8 hours 45 minutes a night, but for the best school results it was one hour less.

Clearly, to find the “Goldilocks Zone” – the optimal balance of study, exercise and sleep – we need to think about more than just school grades and academic achievement.

Read more: 'It was the best five years of my life!' How sports programs are keeping disadvantaged teens at school

Looking for the Goldilocks Day

Based on our study findings , we realised the “Goldilocks Day” that was the best on average for all three domains of health (mental, physical and cognitive) would require compromises. Our optimisation algorithm estimated the Goldilocks Day with the best overall compromise for 11-to-12-year-olds. The breakdown was roughly:

10.5 hours of sleep

9.5 hours of sedentary behaviour (such as sitting to study, chill out, eat and watch TV)

2.5 hours of light physical activity (chores, shopping)

1.5 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (sport, running).

We also recognised that people – or the same people at different times — have different priorities. Around exam time, academic performance may become someone’s highest priority. They may then wish to manage their time in a way that leads to better study results, but without completely neglecting their mental or physical health.

To better explore these trade-offs, we developed our time-use optimisation tool based on Australian data . Although only an early prototype, the tool shows there is no “one size fits all” solution to how young people should be spending their time. However, we can be confident the best solutions will involve a healthy balance across multiple daily activities.

Just like we talk about the benefits of a balanced diet, we should start talking about the benefits of balanced time use. The better equipped young people and those supporting them are to find their optimal daily balance of sleep, sedentary behaviours and physical activities, the better their learning outcomes will be, without compromising their health and well-being.

- Mental health

- Physical activity

- Children's mental health

- Children and sleep

- Children's well-being

- children's physical health

- Sleep research

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Module 6: Learning Styles and Strategies

Class-time to study-time ratio, learning objectives.

- Describe typical ratios of in-class to out-of-class work per credit hour and how to effectively schedule your study time

Class- and Study-Time Ratios

After Kai decides to talk to his guidance counselor about his stress and difficulty balancing his activities, his guidance counselor recommends that Kai create a schedule. This will help him set time for homework, studying, work, and leisure activities so that he avoids procrastinating on his schoolwork. His counselor explains that if Kai sets aside specific time to study every day—rather than simply studying when he feels like he has the time—his study habits will become more regular, which will improve Kai’s learning.

At the end of their session, Kai and his counselor have put together a rough schedule for Kai to further refine as he goes through the next couple of weeks.

Although Kai knows that studying is important and he is trying to keep up with homework, he really needs to work on time management. This is challenging for many college students, especially ones with lots of responsibilities outside of school. Unlike high school classes, college classes meet less often, and college students are expected to do more independent learning, homework, and studying.

You might have heard that the ratio of classroom time to study time should be 1:2 or 1:3. This would mean that for every hour you spend in class, you should plan to spend two to three hours out of class working independently on course assignments. If your composition class meets for one hour, three times a week, you’d be expected to devote from six to nine hours each week on reading assignments, writing assignments, etc.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that the 1:2 or 1:3 ratio is generally more appropriate for semester long courses of 18 weeks. More and more institutions of higher learning are moving away from semesters to terms ranging from 16 to 8 weeks long.

The recommended classroom time to study time ratio might change depending on the course (how rigorous it is and how many credits it’s worth), the institution’s expectations, the length of the school term, and the frequency with which a class meets. For example, if you’re used to taking classes on a quarter system of 10 weeks, but then you start taking courses over an 8 weeks period, you may need to spend more time studying outside of class since you’re trying to learn the same amount of information in a shorter term period. You may also find that if one of the courses you’re taking is worth 1.5 credit hours but the rest of your courses are worth 1 credit hour each, you may need to put in more study hours for your 1.5 credit hour course. Finally, if you’re taking a course that only meets once a week like a writing workshop, you may consider putting in more study and reading time in between class meetings than the general 1:2 or 1:3 ratio.

If you account for all the classes you’re taking in a given semester, the study time really adds up—and if it sounds like a lot of work, it is! Remember, this schedule is temporary while you’re in school. The only way to stay on top of the workload is by creating a schedule to help you manage your time. You might decide to use a weekly or monthly schedule—or both. Whatever you choose, the following tips can help you design a smart schedule that’s easy to follow and stick with.

Start with Fixed Time Commitments

First off, mark down the commitments that don’t allow any flexibility. These include class meetings, work hours, appointments, etc. Capturing the “fixed” parts of your schedule can help you see where there are blocks of time that can be used for other activities.

Kai’s Schedule

Kai is taking four classes: Spanish 101, US History, College Algebra, and Introduction to Psychology. He also has a fixed work schedule—he works 27 hours a week.

Consider Your Studying and Homework Habits

When are you most productive? Are you a morning person or a night owl? Block out your study times accordingly. You’ll also want to factor in any resources you might need. For instance, if you prefer to study very early or late in the day, and you’re working on a research paper, you might want to check the library hours to make sure it’s open when you need it.

Since Kai’s Spanish class starts his schedule at 9:00 every day, Kai decides to use that as the base for his schedule. He doesn’t usually have trouble waking up in the mornings (except for on the weekends), so he decides that he can do a bit of studying before class. His Spanish practice is often something he can do while eating or traveling, so this gives him a bit of leniency with his schedule.

Kai’s marked work in grey, classes in green, and dedicated study time in yellow:

Even if you prefer weekly over monthly schedules, write reminders for yourself and keep track of any upcoming projects, papers, or exams. You will also want to prepare for these assignments in advance. Most students eventually discover (the hard way) that cramming for exams the night before and waiting till the last minute to start on a term paper is a poor strategy. Procrastination creates a lot of unnecessary stress, and the resulting final product—whether an exam, lab report, or paper—is rarely your best work. Try simple things to break down large tasks, such as setting aside an hour or so each day to work on them during the weeks leading up to the deadline. If you get stuck, get help from your instructor early, rather than waiting until the day before an assignment is due.

Schedule Leisure Time

It might seem impossible to leave room in your schedule for fun activities, but every student needs and deserves to socialize and relax on a regular basis. Try to make this time something you look forward to and count on, and use it as a reward for getting things done. You might reserve every Friday or Saturday evening for going out with friends, for example. Perhaps your children have sporting events or special occasions you want to make time for. Try to reschedule your study time so you have enough time to study and enough time to do things outside of school that you want to do.

When you look at Kai’s schedule, you can see that he’s left open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday evenings. While he plans on using Sundays to complete larger assignments when he needs to, he’s left his Friday and Saturday evenings open for leisure.

Now that you have considered ways to create a schedule, you can practice making one that will help you succeed academically. The California Community College’s Online Education site has a free source for populating a study schedule based on your individual course load.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- College Success. Authored by : Jolene Carr. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of hammock. Authored by : eltpics. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/qLiEyP . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Six Tips for College Health and Safety. Provided by : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Located at : http://www.cdc.gov/features/collegehealth/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Interactive visualization requires JavaScript

Related research and data

- Conditional correlation between log income and life satisfaction

- Correlation between life satisfaction and mental illness

- Country-level estimates of patience

- Country-level estimates of positive reciprocity

- Depression prevalence vs. self-reported life satisfaction

- Gender gap in leisure time

- Happiness inequality during periods of economic growth

- Happiness vs. life satisfaction

- How Europeans spend their time

- How important family is to people in life

- How important friends are to people in life

- How important leisure is to people in life

- How important politics is to people in life

- How important religion is to people in life

- How important work is to people in life

- Life satisfaction vs. CO₂ emissions per capita

- Life satisfaction vs. child mortality

- Life satisfaction vs. life expectancy

- Participation time by activity, per day

- Participation time in household and family care per day

- Participation time in leisure, social, and associative life per day

- Participation time in personal care per day

- People who report having friends or relatives they can count on

- Self-reported life satisfaction

- Self-reported life satisfaction vs. GDP per capita

- Share of people who say they are happy First & last waves

- Share of people who say they are happy

- Share of people who say they are satisfied with their life

- Share that feel safe walking alone around the area they live at night

- Time spent on leisure, social, and associative life per day

- Weekly hours dedicated to home production in the USA, by demographic group

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Students Spend More Time on Homework but Teachers Say It's Worth It

Time spent on homework has increased in recent years, but educators say that's because the assignments have also changed.

Students Spending More Time on Homework

iStockphoto

High school students get assigned up to 17.5 hours of homework per week, according to a survey of 1,000 teachers.

Although students nowadays are spending significantly more time on homework assignments – sometimes up to 17.5 hours each week – the type and quality of the assignments have changed to better capture critical thinking skills and higher levels of learning, according to a recent survey of teachers conducted by the University of Phoenix College of Education.

The survey of 1,000 K-12 teachers found, among other things, that high school teachers on average assign about 3.5 hours of homework each week. For high school students who typically have five classes with different teachers, that could mean as much as 17.5 hours each week. By comparison, the survey found middle school teachers assign about 3.2 hours of homework each week and kindergarten through fifth grade teachers assign about 2.9 hours each week.

[ READ : Standardized Testing Debate Should Focus on Local School Districts, Report Says ]

By comparison, a 2011 study from the National Center for Education Statistics found high school students reported spending an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, while a 1994 report from the National Center for Education Statistics – reviewing trends in data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – found 39 percent of 17-year-olds said they did at least one hour of homework each day.

"What has changed is not necessarily the magic number of how many hours they’re doing per night, but it’s the quality of the homework," says Ashley Norris, assistant dean of the university's college of education. Part of that shift in recent years, she says, may come from more schools implementing the Common Core State Standards, which are intended to put more of an emphasis on critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

"You see a change from teachers … giving, really, busy work … to where they’re actually creating long-term projects that students have to manage outside of the classroom, or reading, where they read and come back into the classroom and share their findings," Norris says. "It's not just about rote memorization, because we know that doesn't stick."

For younger students, having more meaningful homework assignments can help build time-management skills, as well as enhance parent-child interaction, Norris says. But the bigger connection for high school students, she says, is doing assignments outside of the classroom that get them interested in a career path.

[ MORE : How Virtual Games Can Help Struggling Students Learn ]

Moving forward, as more schools dive into more time-consuming – but Norris says more meaningful – assignments, there may be a greater shift in the number of schools utilizing the "flipped classroom" method, in which students watch a lesson or lecture at home online, and bring their questions to the classroom to work with their peers while the teacher is present to help facilitate any problems that arise.

"This is already happening in the classrooms. And I think that idea, this whole idea where homework is this applied learning that goes outside the boundaries of a classroom – what can we use that actual class time for?" Norris says "To come back and collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique our own [work] and share those experiences."

Join the Conversation

Tags: K-12 education , education , Common Core , teachers

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Q&A: Border Mayor Backs Biden Action

Elliott Davis Jr. June 6, 2024

Sounding the Alarm on Election Integrity

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton June 5, 2024

FCC Head Pushes AI Ad Plan

What to Know: Biden’s Trip to France

Laura Mannweiler June 5, 2024

Dems Look to Press GOP on Contraception

Earth Hit a Grim Hot Streak Last Month

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder June 5, 2024

The Center For Learning & Teaching

- Canvas Tutorials

- Knowledge Base

- Appointments

- Who To Go To

- Faculty Central

- About the CLT

Understanding and Estimating Instructional Time and Homework

Introduction.

What counts as “class time” — especially when you are adapting a course to a new format like hybrid or online? How do you structure time to maximize engagement and (in online or hybrid situations) get the most out of synchronous or in-person time? Here we explain the relationship between instructional time, homework, and credit hours, so you can understand what Champlain and our accreditors require. We also discuss some options for instructional time that may be very different from what you would do in the classroom.

Credit Hours, Instructional Time, and Out-of-Class Work

Students’ class loads are measured in credit hours; a typical full-time load at Champlain is 15 hours, usually equaling five three-hour classes, although this may vary. The number of credit hours associated with a course is determined by the number of hours it “meets” per week — that is, the amount of instructional time. (This will vary for capstones, internships, and some other course types.)

Most faculty who teach in person are not used to thinking about instructional time. Instead, we think about the hours that we are in the classroom with our students each week. But we can learn from Champlain College Online and other online or blended modes of learning that instructional time can take different forms, many of which might not involve synchronous or in-person interaction.

The key characteristic of instructional time is interaction between instructor and students. The New England Commission on Higher Education (NECHE), Champlain’s accreditor, requires that we provide quality learning experiences that include “ regular, substantive academic interaction ” between instructor and students. Regular interaction means that the faculty member connects with students fairly frequently, in a way that students can grow to expect. Substantive interaction means that the faculty-student interaction is academic in nature and initiated by the instructor.

Therefore, in a hybrid or online course, instructional time is the total hours your students spend in synchronous activities AND asynchronous instructional equivalents like watching recorded lectures, taking quizzes via Canvas, participating in discussion forums, and activities you might normally do as a group, such as a virtual field trip or service project.

According to NECHE, alongside instructional time each week, students should spend approximately twice the number of hours they spend “in class” doing work for that class. That is, if a course is worth three credits (about two and a half hours of instructional time), on average students should be doing approximately five hours of preparation and out-of-class assignments each week, for a total of seven and a half hours of time committed to that course. Rice University’s Center for Teaching Excellence provides an interactive tool for estimating out-of-class student time commitments.

For more information on how this math works, please see Albright College’s explanation of Carnegie Units and credit hours .

Planning Online or Hybrid Instructional Time Equivalents

In the classroom, we know what constitutes instructional time: things we do when we are physically present with students. In fully online situations, we must consider the amount of time students are expected to spend on asynchronous instructional equivalents. In hybrid situations, we must carefully consider the mix of in-person and virtual interaction to calculate instructional time.

Virtual instructional time can involve adaptations of in-person instruction. It can also involve different kinds of activities. Some strategies for interactive, engaging instruction that does not take place through videoconference lecturing include:

Possible Adaptations of In-Person Instruction

- Recorded lecture

- Synchronous small group discussions, critiques, labs, projects, etc.

- Asynchronous discussion forums

- Quizzes and tests delivered via Canvas

- Guest speaker virtual “visit” or webinar

- Library education sessions or consultations with a research librarian (currently offered virtually)

Possible Instructional Time Innovations

- One-on-one or small-group synchronous conversations with the instructor (similar to the tutorial system )

- Individual real-world experiences shared through reflection or discussion (e.g., plant observation walk, interviewing a professional in the field, service learning, etc)

- Virtual tours and field trips

- Lecture-style slides, or written instructor-created content that would normally be delivered via lecture in class

- Collaborative whiteboard, brainstorming, and/or problem-solving activities (synchronous or asynchronous)

- Collaborative reading and annotation using a tool like Hypothesis or Perusall

- Remote/virtual labs

- Low-stakes surveys, quizzes, or check-ins

- Peer review (synchronous or asynchronous)

- Contributing to and commenting on a virtual gallery

There are many options! This list is not intended to be exhaustive. When deciding on instructional time activities, you should focus on options that are highly interactive (student-faculty and/or student-student) and/or focus on experiences like labs, field trips, interviews, or service learning.

Estimating Workloads

This wide range of strategies is great, and it raises an important question: how long does it take students to do these things? How do you get the amount of instructional time equivalents to roughly mirror the number of hours you would spend in a classroom with your students, when you students are completing tasks on their own time and may not work at the same speed?

First of all, something to consider: students generally work a lot less hard when they are sitting in a classroom taking part in an all-class discussion than they do when everyone is required to contribute a discussion post or two on Canvas. A group lab may be less work than a virtual one. The great thing about this is that your instruction can become much richer as students branch out into the things that most pique their interest. However, be aware that asynchronous instructional time can be much more mental labor and organizational work than some forms of classroom instruction, and so your students may be working harder for the same amount of instructional time, or may be spending more time than you think. Create your prompts, assignments, and grading schemes in a way that acknowledges this increased effort.

Pragmatically, here are some estimated amounts of time students might spend doing common virtual learning tasks. (We’re skipping over tasks that have a clearer time commitment like lecture videos and timed quizzes.)

- Discussion posts: minimum of 30 minutes for a 250-word/one-paragraph post and skimming other posts. Direct responses to other students’ posts may take a little less time.

- Blog post: approximately 30 minutes for a 250-word reflection post. If you require research or longer posts, allot at least an hour.

- Case study activities: account for reading time as well as writing time, which will vary widely depending on the exercise. An optimal adult reader who reads visually, does not have reading-related disabilities, and is fluent in English can read about 300 words per minute with no new concepts. For new concepts, writing for an academic audience (eg. journal articles), special genres of writing (e.g. legal cases), or texts you want students to analyze deeply, estimate 150 words per minute. Allow writing time as above. Thus a case study analysis based on a news article–which is a great option for a discussion forum!–with a 250-word response might take 30-45 minutes. On the other hand, analysis of a fifteen-page journal article with a 250-word response could easily take an hour and a half or more.

- Independently arranged interview, field trip, or service learning experience: make sure to add an estimate of the time it takes to arrange an experience (if students are doing that work) to the experience itself.

These suggested times may seem slow to you–but remember, you are estimating based on the speed of an average student.

We also provide a resource on strategies for balancing synchronous and asynchronous teaching , as well as some slides with examples of how to balance and estimate synchronous and asynchronous instructional time equivalents in different types of classes.

Works Consulted

Other institutions’ approaches.

- Course Workload Estimator , Rice University Center for Teaching Excellence

- Credit and Contact Hour and Instructional Equivalencies Guidelines , Valdosta State University

- Guidelines for Instructional Time Equivalencies Across Formats/Assignment of Credit Hours , Misericordia University

- Instructional Equivalencies Chart , Albright College

Was this article helpful?

About the author.

Caroline Toy

Related articles.

- Upvote hand icon 0

- Views/Eye icon 561

- Views/Eye icon 549

- Views/Eye icon 555

- Upvote hand icon 2

- Views/Eye icon 966

- Views/Eye icon 645

- Views/Eye icon 901

- Student Life

- Career Success