- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.1: Weight Management intro

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 53421

- Garrett Rieck & Justin Lundin

- College of the Canyons

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Achieving and sustaining appropriate body weight across the lifespan is vital to maintaining good health and quality of life. Many behavioral, environmental, and genetic factors have been shown to affect a person’s body weight. Calorie balance over time is the key to weight management. Calorie balance refers to the relationship between calories consumed from foods and beverages and calories expended in normal body functions (i.e., metabolic processes) and through physical activity. People cannot control the calories expended in metabolic processes, but they can control what they eat and drink, as well as how many calories they use in physical activity.

Calories consumed must equal calories expended for a person to maintain the same body weight. Consuming more calories than expended will result in weight gain. Conversely, consuming fewer calories than expended will result in weight loss. This can be achieved over time by eating fewer calories, being more physically active, or, best of all, a combination of the two.

Maintaining a healthy body weight and preventing excess weight gain throughout the lifespan are highly preferable to losing weight after weight gain. Once a person becomes obese, reducing body weight back to a healthy range requires significant effort over a span of time, even years. People who are most successful at losing weight and keeping it off do so through continued attention to calorie balance.

The current high rates of overweight and obesity among virtually all subgroups of the population in the United States demonstrate that many Americans are in calorie imbalance—that is, they consume more calories than they expend. To curb the obesity epidemic and improve their health, Americans need to make significant efforts to decrease the total number of calories they consume from foods and beverages and increase calorie expenditure through physical activity. Achieving these goals will require Americans to select a healthy eating pattern that includes nutrient-dense foods and beverages they enjoy, meets nutrient requirements, and stays within calorie needs. In addition, Americans can choose from a variety of strategies to increase physical activity.

Key Recommendations

- Prevent and/or reduce overweight and obesity through improved eating and physical activity behaviors.

- Control total calorie intake to manage body weight. For people who are overweight or obese, this will mean consuming fewer calories from foods and beverages.

- Increase physical activity and reduce time spent in sedentary behaviors.

- Maintain appropriate calorie balance during each stage of life—childhood, adolescence, adulthood, pregnancy and breastfeeding, and older age.

An Epidemic of Overweight and Obesity

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States is dramatically higher now than it was a few decades ago. This is true for all age groups, including children, adolescents, and adults. One of the largest changes has been an increase in the number of Americans in the obese category. As shown in the maps below, the prevalence of obesity has doubled and in some cases tripled between the 1990s and 2011.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Obesity Rates

The high prevalence of overweight and obesity across the population is of concern because individuals who are overweight obese, compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions, including the following:

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (Hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

Ultimately, obesity can increase the risk of premature death. These increased health risks are not limited to adults. Weight-associated diseases and conditions that were once diagnosed primarily in adults are now observed in children and adolescents with excess body fat. For example, cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as high blood cholesterol and hypertension, and type 2 diabetes are now increasing in children and adolescents. The adverse effects also tend to persist through the lifespan, as children and adolescents who are overweight and obese are at substantially increased risk of being overweight and obese as adults and developing weight-related chronic diseases later in life. Primary prevention of obesity, especially in childhood, is an important strategy for combating and reversing the obesity epidemic.

All Americans—children, adolescents, adults, and older adults—are encouraged to strive to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. Adults who are obese should make changes in their eating and physical activity behaviors to prevent additional weight gain and promote weight loss. Adults who are overweight should not gain additional weight, and most, particularly those with cardiovascular disease risk factors, should make changes to their eating and physical activity behaviors to lose weight. Children and adolescents are encouraged to maintain calorie balance to support normal growth and development without promoting excess weight gain. Children and adolescents who are overweight or obese should change their eating and physical activity behaviors so that their BMI-for-age percentile does not increase over time. Further, a health care provider should be consulted to determine appropriate weight management for the child or adolescent. Families, schools, and communities play important roles in supporting changes in eating and physical activity behaviors for children and adolescents.

Maintaining a healthy weight also is important for certain subgroups of the population, including women who are capable of becoming pregnant, pregnant women, and older adults.

- Women are encouraged to achieve and maintain a healthy weight before becoming pregnant. This may reduce a woman’s risk of complications during pregnancy, increase the chances of a healthy infant birth weight, and improve the long-term health of both mother and infant.

- Pregnant women are encouraged to gain weight within the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) gestational weight gain guidelines. Maternal weight gain during pregnancy outside the recommended range is associated with increased risks for maternal and child health.

- Adults ages 65 years and older who are overweight are encouraged to not gain additional weight. Among older adults who are obese, particularly those with cardiovascular disease risk factors, intentional weight loss can be beneficial and result in improved quality of life and reduced risk of chronic diseases and associated disabilities.

- Complications |

- Diagnosis |

- Treatment |

- Special Populations |

- Prognosis |

- Prevention |

- Key Points |

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial, relapsing disorder characterized by excess body weight and defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2. Complications include cardiovascular disorders (particularly in people with excess abdominal fat), diabetes mellitus, certain cancers, cholelithiasis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, cirrhosis, osteoarthritis, reproductive disorders in men and women, psychologic disorders, and, for people with BMI ≥ 35, premature death. Diagnosis is based on BMI. Treatment includes lifestyle modification (eg, diet, physical activity, behavior), anti-obesity medications, and bariatric (weight-loss) surgery.

(See also Obesity in Adolescents .)

Prevalence of obesity in the United States is high in all age groups (see table Changes in Prevalence of Obesity According to NHANES ) and has nearly doubled since the obesity epidemic began in the late 1970s. In 2017–2018, 42.4% of adults had obesity: prevalence was highest in men and women age 40 to 59 ( 1 , 2 ). Prevalence was lowest in non-Hispanic Asian adults (17.4%) compared with non-Hispanic Black (49.6%), Hispanic (44.8%), and non-Hispanic White (42.2%) adults. There were no significant differences in prevalence between men and women among non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian, or Hispanic adults; however, prevalence among non-Hispanic Black women (56.9%) was higher than all other groups.

In the United States, obesity and its complications cause as many as 300,000 premature deaths each year, making it second only to cigarette smoking as a preventable cause of death. Also, obesity is associated with greater job absenteeism, loss of productivity, and higher health care costs. The annual cost of health care in the United States related to obesity is estimated to be $150 billion.

The American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) was established in 2011 to help train clinicians and standardize practices for managing obesity. ABOM diplomates come from a variety of specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. Diplomates share a goal of providing compassionate, individualized, and evidence-based care and improving the overall health of the population. The ABOM stresses obesity be considered a chronic disorder that requires lifelong treatment and follow-up.

1. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al : Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2020.

2. The State of Obesity 2022 . Trust for America's Health, 2022. Accessed 10/30/23.

Etiology of Obesity

Causes of obesity are multifactorial and include genetic predisposition and behavioral, metabolic, and hormonal influences. Ultimately, obesity results from a long-standing imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure, including energy utilization for basic metabolic processes and energy expenditure from physical activity. However, many other factors appear to increase a person's predisposition to obesity, including endocrine disruptors (eg, bisphenol A [BPA]), gut microbiome, sleep/wake cycles, and environmental factors.

Genetic factors

Heritability of BMI is high across different age groups, ranging from 40 to 60% ( 1 , 2 ). With few exceptions, obesity does not follow a simple Mendelian pattern of inheritance but is rather a complex interplay of multiple loci. Genetic factors may affect the many signaling molecules and receptors used by parts of the hypothalamus and gastrointestinal tract to regulate food intake (see sidebar Pathways Regulating Food Intake ). Genome studies have helped define signaling pathways implicated in the predisposition to obesity. Differences in expression of signaling molecules within the leptin-melanocortin pathway (eg, the melanocortrin-4 receptor) have been particularly associated with central control of appetite. Genetic factors can be inherited or result from conditions in utero (called genetic imprinting). Environmental conditions such as nutrition, sleep patterns, and alcohol consumption alter gene expression in various metabolic pathways epigenetically; this effect suggests possible reversibility of environmental factors and refinement of therapeutic targets.

Pathways Regulating Food Intake

Genetic factors also regulate energy expenditure, including basal metabolic rate, diet-induced thermogenesis, and nonvoluntary activity–associated thermogenesis. Genetic factors may have a greater effect on the distribution of body fat, particularly abdominal fat (which increases the risk of metabolic syndrome ), than on the amount of body fat.

Lifestyle and behavioral factors

Weight is gained when caloric intake exceeds energy needs. Important determinants of energy intake include

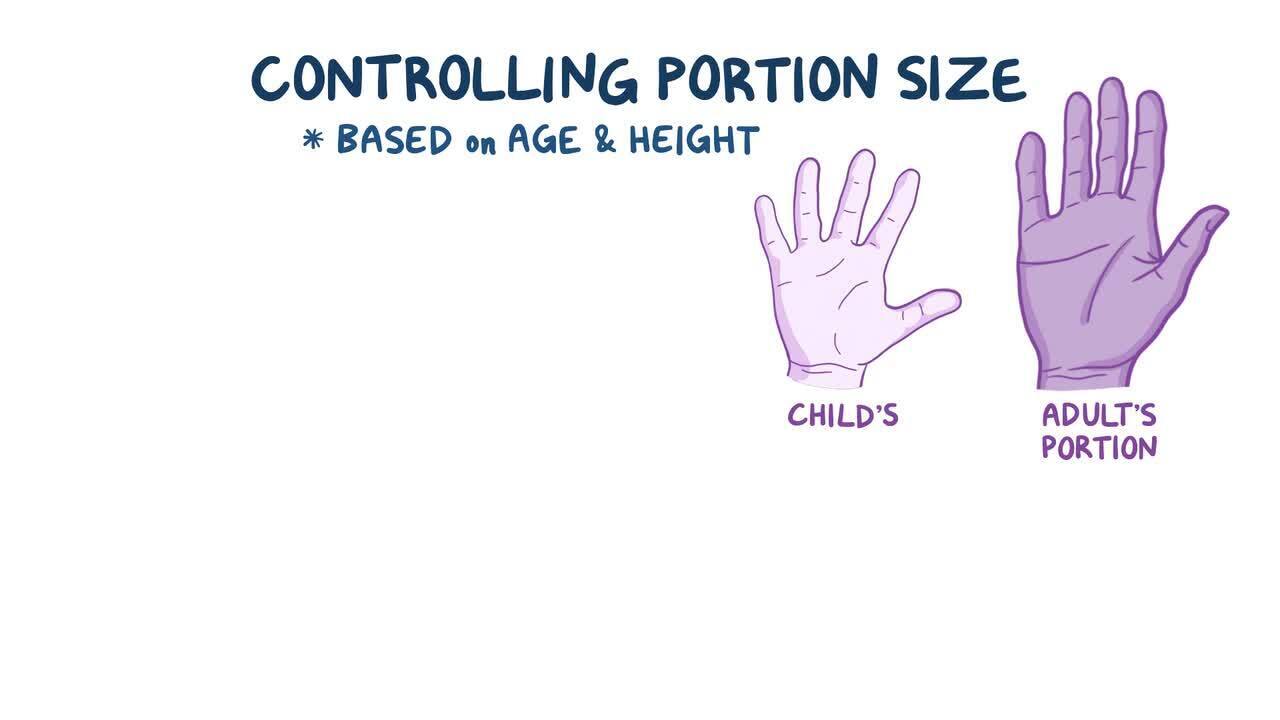

Portion sizes

The energy density of the food

Systemic drivers of lifestyle and behavioral factors are rooted in community culture and economic systems. Communities which do not have access to fresh fruits and vegetables and which do not consume water as the main fluid consumed tend to have higher rates of obesity. High-calorie, energy-dense foods (eg, processed foods), diets high in refined carbohydrates, and consumption of soft drinks, fruit juices, and alcohol promote weight gain.

Access to safe recreational spaces (eg, pedestrian and biking infrastructure, parks) and availability of public transportation can encourage physical activity and help protect against obesity.

Regulatory factors

Prenatal maternal obesity, prenatal maternal smoking , excessive weight gain during pregnancy (see table Guidelines for Weight Gain During Pregnancy ), and intrauterine growth restriction can disturb weight regulation and contribute to weight gain during childhood and later. Obesity that persists beyond early childhood makes weight loss in later life more difficult.

The composition of the gut microbiome also appears to be an important factor; early use of antibiotics and other factors that alter the composition of the gut microbiome may promote weight gain and obesity later in life ( 3 ).

Early exposure to obesogens, a type of endocrine-disrupting chemical (eg, cigarette smoke, bisphenol A, air pollution, flame retardants, phthalates, polychlorinated biphenyls) can alter metabolic set points through epigenetics or nuclear activation, increasing the propensity of developing obesity ( 4 ).

Adverse childhood events or abuse in early childhood increase risk of several disorders, including obesity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's adverse childhood events study demonstrated that childhood history of verbal, physical, or sexual abuse predicted an increase of 8% in risk of a BMI ≥ 30 and 17.3% in risk of a BMI ≥ 40. Certain types of abuse carried the strongest risk. For example, frequent verbal abuse had the largest increase in risk (88%) of a BMI > 40. Being often hit and injured increased the risk of BMI > 30 by 71% ( 5 ). Cited mechanisms for the association between abuse and obesity include neurobiologic and epigenetic phenomena ( 6 ).

Insufficient sleep (usually considered 7 )

Smoking cessation is associated with weight gain and can deter patients from quitting smoking.

Uncommonly, weight gain is caused by one of the following disorders:

Alternations in brain structure and function caused by a tumor (especially a craniopharyngioma) or an infection (particularly those affecting the hypothalamus), which can stimulate consumption of excess calories

Hyperinsulinism due to pancreatic tumors

Hypercortisolism due to Cushing syndrome , which causes predominantly abdominal obesity

Hypothyroidism (rarely a cause of substantial weight gain)

Hypogonadism

Eating disorders

At least 2 pathologic eating patterns may be associated with obesity:

Binge eating disorder is consumption of large amounts of food quickly with a subjective sense of loss of control during the binge and distress after it. This disorder does not include compensatory behaviors, such as vomiting. Binge eating disorder occurs in about 3.5% of women and 2% of men during their lifetime and in about 10 to 20% of people entering weight reduction programs. Obesity is usually severe, large amounts of weight are frequently gained or lost, and pronounced psychologic disturbances are present.

Night-eating syndrome

Similar but less extreme patterns probably contribute to excess weight gain in more people. For example, eating after the evening meal contributes to excess weight gain in many people who do not have night-eating syndrome.

Etiology references

1. Mahmoud AM : An overview of epigenetics in obesity: The role of lifestyle and therapeutic interventions. Int J Mol Sci 23 (3):1341. 2022. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031341

2. Nan C, Guo B, Claire Warner C, et al : Heritability of body mass index in pre-adolescence, young adulthood and late adulthood. Eur J Epidemiol 27 (4):247–253, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9678-6 Epub 2012 Mar 18.

3. Ajslev TA, Andersen CS, Gamborg M, et al : Childhood overweight after establishment of the gut microbiota: The role of delivery mode, pre-pregnancy weight and early administration of antibiotics. Int J Obes 35 (4): 522–529, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.27

4. Heindel JJ, Newbold R, Schug TT : Endocrine disruptors and obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11 (11):653–661, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.163

5. Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, et al : Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26 (8):1075–1082, 2002. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038

6. Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al : The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256 (3):174–186, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

7. Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, et al : Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med 1 (3):e62, 2004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062 Epub 2004 Dec 7.

Complications of Obesity

Complications of obesity can affect almost every organ system; they include the following:

Metabolic syndrome

Diabetes mellitus

Cardiovascular disorders

Venous thromboembolism

Liver disorders ( metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease , which may lead to cirrhosis )

Gallbladder disease ( cholelithiasis )

Gastroesophageal reflux

Obstructive sleep apnea

Reproductive system disorders, including infertility in both sexes, a low serum testosterone level in men, and polycystic ovary syndrome in women

Many cancers (especially colon cancer and breast cancer )

Osteoarthritis

Tendon and fascial disorders

Skin disorders (eg, intertriginous infections )

Hypertension

Depression , anxiety , and body dysmorphic disorder

Fat tissue is an active endocrine organ that secretes adipokines and free fatty acids that increase systemic inflammation, resulting in conditions such as , atherosclerosis , and impaired immunity.

The pathogenesis of obesity-related hypertension is mediated largely by activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system via leptin and angiotensin directly released from visceral adipocytes. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity increases vasoconstriction.

, dyslipidemias , and hypertension (metabolic syndrome) can develop, often leading to diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease . These complications are more likely in patients with fat that is concentrated abdominally (visceral fat), a high serum triglyceride level, a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus or premature cardiovascular disease, or a combination of these risk factors.

Obstructive sleep apnea can result if excess fat in the neck compresses the airway during sleep. Breathing stops for moments, as often as hundreds of times a night. This disorder, often undiagnosed, can cause loud snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness and increases the risk of hypertension , cardiac arrhythmias , and metabolic syndrome .

Obesity may cause obesity-hypoventilation syndrome (Pickwickian syndrome). Impaired breathing leads to hypercapnia, reduced sensitivity to carbon dioxide in stimulating respiration, hypoxia, cor pulmonale , and risk of premature death. This syndrome may occur alone or secondary to obstructive sleep apnea.

Skin disorders are common; increased sweat and skin secretions, trapped in thick folds of skin, are conducive to fungal and bacterial growth, making intertriginous infections especially common.

Being overweight probably predisposes to gout , deep venous thrombosis , and pulmonary embolism .

Obesity leads to social, economic, and psychologic problems as a result of prejudice, discrimination, poor body image, and low self-esteem. For example, people may be underemployed or unemployed.

Diagnosis of Obesity

Body mass index (BMI)

Waist circumference

Body composition analysis

In adults, BMI, defined as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m 2 ), is used to screen for overweight or obesity:

Overweight = 25 to 29.9 kg/m2

Class I obesity = 30 to 34.9 kg/m2

Class II obesity = 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

Class II obesity = ≥ 40 kg/m2

BMI is a commonly used tool that can be easily calculated and correlates with metabolic and fat mass disease in human population studies. However, BMI is a crude screening tool and has limitations in many subpopulations. It tends to overdiagnose overweight and obesity in muscular patients and underdiagnose them in patients with sarcopenia. Some experts think that BMI cutoffs should vary based on ethnicity, sex, and age. The World Health Organization (WHO) and International Diabetes Federation suggest lower cutoff points for people of Asian descent compared with those of other ethnicities ( 1 ).

Waist circumference and the presence of metabolic syndrome appear to predict risk of metabolic and cardiovascular complications better than BMI does ( 2 ). The waist circumference that increases risk of complications due to obesity varies by ethnic group and sex ( 3 ).

Body composition—the percentage of body fat and muscle—is also considered when obesity is diagnosed. Although probably unnecessary in routine clinical practice, body composition analysis can be helpful if clinicians question whether elevated BMI is due to muscle or excessive fat.

Men are considered to have obesity when body fat levels are > 25%. In women, the cutoff is > 32%.

The percentage of body fat can be estimated by measuring skinfold thickness (usually over the triceps) or determining mid upper arm muscle area .

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) can estimate percentage of body fat simply and noninvasively. BIA estimates percentage of total body water directly; percentage of body fat is derived indirectly. BIA is most reliable in healthy people and in people with only a few chronic disorders that do not change the percentage of total body water (eg, moderate obesity, diabetes mellitus). Whether measuring BIA poses risks in people with implanted defibrillators is unclear.

Underwater (hydrostatic) weighing is the most accurate method for measuring percentage of body fat. Costly and time-consuming, it is used more often in research than in clinical care. To be weighed accurately while submerged, people must fully exhale beforehand.

Imaging procedures, including CT, MRI, and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), can also estimate the percentage and distribution of body fat but are usually used only for research.

Other testing

Patients with obesity should be screened for common comorbid disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea , diabetes , dyslipidemia , hypertension , steatotic liver disease , and depression . Screening tools can help; for example, for obstructive sleep apnea, clinicians can use an instrument such as the STOP-BANG questionnaire (see table STOP-BANG Risk Score for Obstructive Sleep Apnea ) and often the apnea-hypopnea index (total number of apnea or hypopnea episodes occurring per hour of sleep). Obstructive sleep apnea is often underdiagnosed, and obesity increases the risk.

Diagnosis references

1. WHO Expert Consultation : Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet . 363 (9403):157–163, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 Erratum in Lancet 363 (9412):902, 2004.

3. Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al : Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS [International Atherosclerosis Society] and ICCR [International Chair on Cardiometabolic Risk] Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 16 (3):177–189, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0310-7 Epub 2020 Feb 4.

3. Luo J, Hendryx M, Laddu D, et al : Racial and ethnic differences in anthropometric measures as risk factors for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019 42 (1):126–133. 2019. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1413 Epub 2018 Oct 23.

Treatment of Obesity

Dietary management

Physical activity

Behavioral interventions, anti-obesity medications.

Bariatric surgery

Weight loss of even 5 to 10% improves overall health, helps reduce risk of developing cardiovascular complications (eg, hypertension , dyslipidemia , ) and helps lessen their severity ( 1 ), and may lessen the severity of other complications and comorbid disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea , steatotic liver disease , infertility , and depression .

Support from health care practitioners, peers, and family members and various structured programs can help with weight loss and weight maintenance. Emphasizing obesity as a chronic disorder, rather than a cosmetic issue caused by lack of self-control, helps empower patients to seek sustainable care and clinicians to provide such care. Using people-first language, such as "people with obesity" rather than "obese people," helps avoid labeling patients by their disease and combats stigma.

Balanced eating is important for weight loss and maintenance.

Strategies include

Eating small meals and avoiding or carefully choosing snacks

Substituting fresh fruits and vegetables and salads for refined carbohydrates and processed food

Substituting water for soft drinks or juices

Limiting alcohol consumption to moderate levels

Including no- or low-fat dairy products, which are part of a healthy diet and help provide an adequate amount of vitamin D

Low-calorie, high-fiber diets that modestly restrict calories (by 600 kcal/day) and that incorporate lean protein appear to have the best long-term outcome. Foods with a low glycemic index (see table Glycemic Index of Some Foods ) and marine fish oils or monounsaturated fats derived from plants (eg, olive oil) reduce the risk of cardiovascular disorders and diabetes .

Use of meal replacements can help with weight loss and maintenance; these products can be used regularly or intermittently.

Diets that are overly restrictive are unlikely to be maintained or to result in long-term weight loss. Diets that limit caloric intake to basal energy expenditure (BEE), described as very low calorie diets, can have as few as 800 kcal/day.

Energy expenditure and metabolic rate vary with diet and activity. Restrictive dieting may produce short-term modest weight loss; however, levels of hormones such as leptin, insulin , gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), and ghrelin change to favor weight regain. In a long-term analysis of low-calorie diets, between one- third and two thirds of dieters regained more weight than they lost initially ( 2 ).

Exercise increases energy expenditure, basal metabolic rate, and diet-induced thermogenesis. Exercise also seems to regulate appetite to more closely match caloric needs. Other benefits associated with physical activity include

Increased insulin sensitivity

Improved lipid profile

Lower blood pressure

Better aerobic fitness

Improved psychologic well-being

Decreased risk of breast and colon cancer

Increased life expectancy

Exercise, including strengthening (resistance) exercises, increases muscle mass. Because muscle tissue burns more calories at rest than does fat tissue, increasing muscle mass produces lasting increases in basal metabolic rate. Exercise that is interesting and enjoyable is more likely to be sustained. A combination of aerobic and resistance exercise is better than either alone. Guidelines suggest physical activity of 150 minutes/week for health benefits and 300 to 360 minutes/week for weight loss and maintenance. Developing a more physically active lifestyle can help with weight loss and maintenance.

Clinicians can recommend various behavioral interventions to help patients lose weight ( 3 ). They include

Self-monitoring

Stress management

Contingency management

Problem solving

Stimulus control

Support may come from a group, friends or family members. Participation in a support group can improve adherence to lifestyle changes and thus increase weight loss. The more frequently people attend group meetings, the greater the support, motivation, and supervision they receive and the greater their accountability, resulting in greater weight loss. Patients can get support by using social media to connect with each other and clinicians.

Self-monitoring may include keeping a food log (including the number of calories in foods), weighing regularly, and observing and recording behavioral patterns. Other useful information to record includes time and location of food consumption, the presence or absence of other people, and mood. Clinicians can provide feedback about how patients may improve their eating habits.

Stress management involves teaching patients to identify stressful situations and to develop strategies to manage stress that do not involve eating (eg, going for a walk, meditating, deep breathing).

Contingency management involves providing tangible rewards for positive behaviors (eg, for increasing time spent walking or reducing consumption of certain foods). Rewards may be given by other people (eg, from members of a support group or a health care practitioner) or by the person (eg, purchase of new clothing or tickets to a concert). Verbal rewards (praise) may also be useful.

Problem solving involves identifying and planning ahead for situations that increase the risk of unhealthy eating (eg, travelling, going out to dinner) or that reduce the opportunity for physical activity (eg, driving across country).

Stimulus control involves identifying obstacles to healthy eating and an active lifestyle and developing strategies to overcome them. For example, people may avoid going by a fast food restaurant or not keep sweets in the house. For a more active lifestyle, they may take up an active hobby (eg, gardening), enroll in scheduled group activities (eg, exercise classes, sports teams), walk more, make a habit of taking the stairs instead of elevators, and park at the far end of parking lots (resulting in a longer walk).

Technology-based resources such as applications for mobile devices, and other technological devices may also help with adherence to lifestyle changes and weight loss. Applications can help patients set a weight-loss goal, monitor their progress, track food consumption, and record physical activity.

Pharmacotherapy to treat obesity should be considered for people with a BMI of > 27 kg/m2 plus comorbidities or 30 kg/m2 without comorbidities ( 4 ). Before prescribing medications, clinicians must identify comorbidities that may be affected by medications (eg. diabetes , seizure disorders , opioid use disorder ), and concomitant medications that may promote weight gain.

Most anti-obesity medications are in one of the following classes:

glucagon -like peptide 1 [GLP-1] agonists)

Weight loss, effects on comorbidities, and adverse effect profiles differ widely among medications.

Patients must be warned that stopping long-term anti-obesity medications may result in weight regain.

Specific medications include:

inhibits pancreatic lipase, decreasing intestinal absorption of fat and improving blood glucose and lipids. Because orlistat orlistat difficult to tolerate. Orlistat is available over-the-counter.

The combination of (used to treat seizure disorders and migraines) is approved for long-term use. This combination medication results in weight loss for up to 2 years. Because birth defects are a risk, the combination should be given to women of reproductive age only if they are using contraception and are tested monthly for pregnancy. Other potential adverse effects include sleep problems, cognitive impairment, and increased heart rate. Long-term cardiovascular effects are unknown, and postmarketing studies are ongoing ( 5 ).

lorcaserin compared with those taking placebo. The most common adverse effects in patients without diabetes are headache, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, and constipation; these effects are usually self-limited. Lorcaserin serotonin syndrome is a risk. Lorcaserin was withdrawn from the United States market after an increased cancer risk was identified in a postmarketing trial ( 6 ).

bupropion include nausea, vomiting, headache, and mild increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Contraindications to bupropion include uncontrolled hypertension and a history of or risk factors for seizures because bupropion reduces the seizure threshold.

7 insulin release from the pancreas to induce glycemic control; liraglutide also stimulates satiety and reduces food intake. Liraglutide is injected daily, and dose is titrated up over the course of 5 weeks. Adverse effects include nausea and vomiting; liraglutide has warnings that include acute pancreatitis and risk of thyroid C-cell tumors.

insulin release and reduces appetite and energy intake via effects on appetite centers in the hypothalamus. Semaglutide 2.4 mg subcutaneously has resulted in a mean body weight loss of 14.9% at 68 weeks versus 2.4% in patients treated with placebo ( 8 ). Patients taking semaglutide also had greater improvements in cardiovascular risk factors as well as patient-reported physical functioning. Like liraglutide , the most common adverse effects of semaglutide include nausea and diarrhea, which are usually transient and mild to moderate in severity. Warnings for semaglutide include thyroid tumors and pancreatitis.

is a novel gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 agonist used to treat type 2 diabetes. In a phase 3 trial, it resulted in substantial and sustained reductions in body weight in patients who did not have diabetes. Improvements in cardiometabolic disease were also observed. It can cause pancreatitis, hypoglycemia, and C-cell tumors of the thyroid and is contraindicated in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 ( 9 ).

All GLP-1 agonists are associated with adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, and delayed gastric emptying, which can increase the risk of aspiration. The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting recommends holding daily-dosed GLP-1 agonists the day of surgery and weekly-dosed medications 1 week before surgery ( 10 ).

Studies have shown that anti-obesity medications can be safe and effective for weight loss after bariatric surgery if weight is regained. Investigation into the use of anti-obesity medications (eg, GLP-1 receptor agonists) as a bridge t therapy to metabolic and bariatric surgery is ongoing ( 11 ).

Anti-obesity medications should be stopped or changed if patients do not have documented weight loss after 12 weeks of treatment.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for patients with severe obesity.

Treatment references

1. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert, MA, et al : 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 140 (11):e596-e646, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 Epub 2019 Mar 17.

2. Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, et al : Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. Am Psychol 62 (3):220–233, 2007. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220

3. US Preventive Services Task Force : Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults. JAMA 320 (11):1163–1171, 2018, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13022

4. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 22 Suppl 3:1–203, 2016. doi: 10.4158/EP161365.GL Epub 2016 May 24.

5. Jordan J, Astrup A, Engeli S, et al J Hypertens 32 (6): 1178–1188, 2014. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000145 Published online 2014 Apr 30.

6. Mahase E M: Weight loss pill praised as "holy grail" is withdrawn from US market over cancer link. BMJ 20;368:m705, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m705 PMID: 32079611.

7. Mehta A, Marso SP, Neeland, IJ Obes Sci Pract 3 (1):3–14, 2017. doi: 10.1002/osp4.84 Epub 2016 Dec 19.

8. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al N Engl J Med 18;384(11):989, 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

9. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al N Engl J Med 21;387 (3):205–216, 2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038 Epub 2022 Jun 4.

10. Joshi GP, Abdelmalak BB, Weigel WA, et al

11. Mok J, Mariam OA, Brown A, et al JAMA Surg 158 (10):1003–1011, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.2930

Special Populations in Obesity

Obesity is a particular concern in children and older adults.

Obesity in children is defined as BMI greater than the 95th percentile. For children with obesity, complications are more likely to develop because the duration of the disorder is longer. More than 25% of children and adolescents meet overweight or obesity criteria. (See also Obesity in Adolescents .) Similar to adults, complications related to obesity in children include hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes and joint problems.

Risk factors for obesity in infants are low birth weight ( 1 ) and maternal weight, diabetes, and smoking .

After puberty, food intake increases; in boys, the extra calories are used to increase protein deposition, but in girls, fat storage is increased.

For children with obesity, psychologic complications (eg, poor self-esteem, social difficulties, depression) and musculoskeletal complications can develop early. Some musculoskeletal complications, such as slipped capital femoral epiphyses , are specific to children. Other early complications may include obstructive sleep apnea , , hyperlipidemia, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis . Risk of cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, hepatic, and other obesity-related complications increases when these children become adults.

Risk of obesity persisting into adulthood depends partly on when obesity first develops. In a meta-analysis of several large cohort studies, 55% of children with obesity continued to have obesity in adolescence, and 70% continued to have obesity over the age of 30 ( 2 ).

Treatment of obesity in children and adolescents involves lifestyle modifications and, for children with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery .. Participating in physical activities during childhood may promote a lifelong physically active lifestyle. Limiting sedentary activities (eg, watching TV, using the computer or handheld devices) can also help. Medications and surgery are avoided but, if complications of obesity are life threatening, may be warranted.

Measures that control weight and prevent obesity in children may have the largest public health benefits. Such measures should be implemented in the family, schools, and primary care. However, lifestyle modifications often do not result in permanent weight loss.

The 2023 updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that children and adolescents who have severe obesity (defined as BMI ≥ 40 or BMI > 35 with significant health complications related to obesity) should be treated with metabolic and bariatric surgery, and treatment should involve a multidisciplinary team. The major metabolic and bariatric surgical societies have similar recommendations; however, metabolic and bariatric surgery is not often used in children and adolescents. Barriers include stigma against bariatric surgery in this population and lack of available centers and clinicians trained to take care of children and adolescents with obesity ( 3 ).

Older adults

In the United States, the percentage of older people with obesity has been increasing.

With age, body fat increases and is redistributed to the abdomen, and muscle mass is lost, largely because of physical inactivity, but decreased androgens and growth hormone (which are anabolic) and inflammatory cytokines produced in obesity may also play a role.

Risk of complications depends on

Body fat distribution (increasing with a predominantly abdominal distribution)

Duration and severity of obesity

Associated sarcopenia

Increased waist circumference, suggesting abdominal fat distribution, predicts morbidity (eg, hypertension , diabetes mellitus , coronary artery disease ) and mortality risk better in older adults than does BMI. With aging, fat tends to accumulate more in the waist.

For older adults, physicians may recommend that caloric intake be reduced and physical activity be increased. However, if older patients wish to substantially reduce their caloric intake, their diet should be supervised by a physician. Physical activity also improves muscle strength, endurance, and overall well-being and reduces the risk of developing chronic disorders such as diabetes. Activity should include strengthening and endurance exercises.

Metabolic and bariatric surgery has historically been used less frequently in older patients. In a large retrospective study comparing outcomes in patients sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass , complication rates between the groups were similar. Although older patients tended to have higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores and more comorbidities at baseline, morbidity and mortality after surgery did not differ between groups. In the ≥ 65 group, the positive effect of bariatric surgery on weight loss and obesity-related comorbidities was present but less pronounced than in the 4 ).

Special populations references

1. Jornayvaz FR, Vollenweider P, Bochud M, et al : Low birth weight leads to obesity, diabetes and increased leptin levels in adults: The CoLaus study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 15:73, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0389-2

2. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen ACG, Woolacott N : Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 17 (2):95–107, 2016. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334 Epub 2015 Dec 23.

3. Elkhoury D, Elkhoury C, Gorantla VR . Improving access to child and adolescent weight loss surgery: A review of updated National and International Practice Guidelines. Cureus 15 (4):e38117, 2023. doi: 10.7759/cureus.38117

4. Iranmanesh P, Boudreau V, Ramji K, et al : Outcomes of bariatric surgery in elderly patients: A registry-based cohort study with 3-year follow-up. Int J Obes (Lond) 46 (3), 574–580 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-01031-]]

Prognosis for Obesity

If untreated, obesity tends to progress. The probability and severity of complications are proportional to

The absolute amount of fat

The distribution of the fat

Absolute muscle mass

After weight loss, most people return to their pretreatment weight within 5 years, and accordingly, obesity requires a lifelong management program similar to that for any other chronic disorder. Also, when anti-obesity medications are stopped, patients tend to regain weight.

Prevention of Obesity

Regular physical activity and healthy eating improve general fitness, can control weight, and help prevent diabetes mellitus and obesity. Even without weight loss, exercise decreases the risk of cardiovascular disorders. Dietary fiber decreases the risk of colon cancer and cardiovascular disorders.

Sufficient and good-quality sleep, management of stress, and moderation of alcohol intake are also important. However, many biologic and socioeconomic factors are out of a person's control.

Obesity increases the risk of many common health problems and causes up to 300,000 premature deaths each year in the United States, making it second only to cigarette smoking as a preventable cause of death.

Excess caloric intake and too little physical activity contribute the most to obesity, but genetic susceptibility and various disorders (including eating disorders) may also contribute.

Screen patients using BMI and waist circumference and, when body composition analysis is indicated, by measuring skinfold thickness or using bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Screen patients with obesity for common comorbid disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, steatotic liver disease, and depression.

Encourage patients to lose even 5 to 10% of body weight by changing their diet, increasing physical activity, and using behavioral interventions if possible.

Consider anti-obesity medications if BMI is ≥ 30 or if BMI is ≥ 27 with complications (eg, hypertension, insulin resistance); however, for severe obesity, surgery is most effective.

Encourage all patients to exercise, to eat healthily, to get enough sleep, and to manage stress.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- Weight Management

- Understanding Adult Overweight & Obesity

- Health Risks

- Español

Health Risks of Overweight & Obesity

In this section:

Type 2 diabetes

High blood pressure, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver diseases, some cancers, breathing problems, osteoarthritis, diseases of the gallbladder and pancreas, kidney disease, pregnancy problems, fertility problems, sexual function problems, mental health problems.

Overweight and obesity may increase your risk for many health problems—especially if you carry extra fat around your waist. Reaching and staying at a healthy weight can help prevent these problems, stop them from getting worse, or even make them go away.

Type 2 diabetes is a disease that occurs when your blood glucose , also called blood sugar, is too high. Nearly 9 in 10 people with type 2 diabetes have overweight or obesity. 12 Over time, high blood glucose can lead to heart disease , stroke, kidney disease , eye problems , nerve damage , and other health problems .

If you are at risk for type 2 diabetes, you may be able to prevent or delay diabetes by losing at least 5% to 7% of your starting weight. 13,14 For instance, if you weigh 200 pounds, your goal would be to lose about 10 to 14 pounds.

High blood pressure , also called hypertension, is a condition in which blood flows through your blood vessels with a force greater than normal. Having a large body size may increase blood pressure because your heart needs to pump harder to supply blood to all your cells. Excess fat may also damage your kidneys , which help regulate blood pressure.

High blood pressure can strain your heart, damage blood vessels, and raise your risk of heart attack , stroke , kidney disease , and death. 10 Losing enough weight to reach a healthy body mass index range may lower high blood pressure and prevent or control related health problems.

Heart disease is a term used to describe several health problems that affect your heart, such as a heart attack , heart failure , angina , or an abnormal heart rhythm. Having overweight or obesity increases your risk of developing conditions that can lead to heart disease, such as high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol , and high blood glucose. In addition, excess weight can also make your heart have to work harder to send blood to all the cells in your body. Losing excess weight may help you lower these risk factors for heart disease.

A stroke happens when a blood vessel in your brain or neck is blocked or bursts, cutting off blood flow to a part of your brain. A stroke can damage brain tissue and make you unable to speak or move parts of your body.

Overweight and obesity are known to increase blood pressure—and high blood pressure is the leading cause of strokes. Losing weight may help you lower your blood pressure and other risk factors for stroke, including high blood glucose and high blood cholesterol.

Metabolic syndrome is a group of conditions that increase your risk for heart disease, diabetes , and stroke. To be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, you must have at least three of the following conditions

- large waist size

- high level of triglycerides in your blood

- high blood pressure

- high level of blood glucose when fasting

- low level of HDL cholesterol —the “good” cholesterol—in your blood

Metabolic syndrome is closely linked to overweight and obesity and to a lack of physical activity. Healthy lifestyle changes that help you control your weight may help you prevent and reduce metabolic syndrome.

Fatty liver diseases develop when fat builds up in your liver , which can lead to severe liver damage, cirrhosis , or even liver failure . These diseases include nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) .

NAFLD and NASH most often affect people who have overweight or obesity. People who have insulin resistance , unhealthy levels of fat in the blood, metabolic syndrome , type 2 diabetes, and certain genes can also develop NAFLD and NASH.

If you have overweight or obesity, losing at least 3% to 5% of your body weight may reduce fat in the liver. 15

Cancer is a collection of related diseases. In all types of cancer, some of the body’s cells begin to grow abnormally or out of control. The cancerous cells sometimes spread to other parts of the body.

Overweight and obesity may raise your risk of developing certain types of cancer . Men with overweight or obesity are at a higher risk for developing cancers of the colon , rectum , and prostate . 10 Among women with overweight or obesity, cancers of the breast , lining of the uterus , and gallbladder are more common.

Adults who gain less weight as they get older have lower risks of many types of cancer, including colon, kidney , breast, and ovarian cancers . 16

Overweight and obesity can also affect how well your lungs work, and excess weight increases your risk for breathing problems. 17

Sleep apnea

Sleep apnea is a common problem that can happen while you are sleeping. If you have sleep apnea, your upper airway becomes blocked, causing you to breathe irregularly or even stop breathing altogether for short periods of time. Untreated sleep apnea may raise your risk for developing many health problems, including heart disease and diabetes.

Obesity is a common cause of sleep apnea in adults. 18 If you have overweight or obesity, you may have more fat stored around your neck, making the airway smaller. A smaller airway can make breathing difficult or cause snoring. If you have overweight or obesity, losing weight may help reduce sleep apnea or make it go away.

Asthma is a chronic, or long-term, condition that affects the airways in your lungs. The airways are tubes that carry air in and out of your lungs. If you have asthma, the airways can become inflamed and narrow at times. You may wheeze, cough, or feel tightness in your chest.

Obesity can increase your risk of developing asthma, experiencing worse symptoms, and having a harder time managing the condition. 19 Losing weight can make it easier for you to manage your asthma. For people who have severe obesity, weight-loss surgery—also called metabolic and bariatric surgery—may improve asthma symptoms. 17

Osteoarthritis is a common, long-lasting health problem that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and reduced motion in your joints . Obesity is a leading risk factor for osteoarthritis in the knees, hips, and ankles. 20

Having overweight or obesity may raise your risk of getting osteoarthritis by putting extra pressure on your joints and cartilage. If you have excess body fat, your blood may have higher levels of substances that cause inflammation . Inflamed joints may raise your risk for osteoarthritis.

If you have overweight or obesity, losing weight may decrease stress on your knees, hips, and lower back and lessen inflammation in your body. If you have osteoarthritis, losing weight may improve your symptoms. Research shows that exercise is one of the best treatments for osteoarthritis. Exercise can improve mood, decrease pain, and increase flexibility.

Gout is a kind of arthritis that causes pain and swelling in your joints. Gout develops when crystals made of a substance called uric acid build up in your joints. Risk factors include having obesity, being male, having high blood pressure, and eating foods high in purines . 21 These foods include red meat, liver, and anchovies.

Gout is treated mainly with medicines. Losing weight may also help prevent and treat gout. 22

Overweight and obesity may raise your risk of getting gallbladder diseases, such as gallstones and cholecystitis . People who have obesity may have higher levels of cholesterol in their bile , which can cause gallstones. They may also have a large gallbladder that does not work well.

Having a large amount of fat around your waist may raise your risk for developing gallstones. But losing weight quickly also increases your risk. If you have obesity, talk with your health care professional about how to lose weight safely .

Obesity can also affect your pancreas , a large gland behind your stomach that makes insulin and enzymes to help you digest food. People who have obesity have a higher risk of developing inflammation of the pancreas, called pancreatitis . High levels of fat in your blood can also raise your risk of having pancreatitis. You can lower your chances of getting pancreatitis by sticking with a low-fat, healthy eating plan.

Kidney disease means your kidneys are damaged and can’t filter your blood as they should. Obesity raises the risk of developing diabetes and high blood pressure, which are the most common causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Even if you don’t have diabetes or high blood pressure, having obesity may increase your risk of developing CKD and speed up its progress. 23

If you have overweight or obesity, losing weight may help you prevent or delay CKD. If you are in the early stages of CKD, consuming healthy foods and beverages , being active, and losing excess weight may slow the progress of the disease and keep your kidneys healthier longer. 24

Overweight and obesity raise the risk of developing health problems during pregnancy that can affect the pregnancy and the baby’s health. Pregnant people who have obesity may have a greater chance of 10

- developing gestational diabetes , or diabetes that occurs during pregnancy

- having preeclampsia , or high blood pressure during pregnancy, which can cause severe health problems for the pregnant person and baby if left untreated

- needing a caesarean delivery —or c-section—and, as a result, taking longer to recover after giving birth

- having complications from surgery and anesthesia , especially if they have severe obesity

- gaining more weight or continuing to have overweight or obesity after the baby is born

Having obesity or gaining too much weight during pregnancy can also increase health risks for the baby, including 25

- being born larger than expected based on the sex of the baby or the duration of the pregnancy

- developing chronic diseases as adults, including type 2 diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and asthma

Talk with your health care professional about how to

- reach a healthy weight before pregnancy

- gain a healthy amount of weight during pregnancy

- safely lose weight after your baby is born

Obesity increases the risk of developing infertility . Infertility in women means not being able to get pregnant after a year of trying, or getting pregnant but not being able to carry a pregnancy to term. For men, it means not being able to get a woman pregnant. 26

Obesity is linked to lower sperm count and sperm quality in men. 27 In women, obesity is linked to problems with the menstrual cycle and ovulation . 26 Obesity can also make it harder to become pregnant with the help of certain infertility treatments or procedures. 26

Women with obesity who lose 5% of their body weight may increase their chances of having regular menstrual periods, ovulating, and becoming pregnant. 28

Obesity may also increase the risk of developing sexual function problems. 29 Having overweight or obesity increase the risk of developing erectile dysfunction (ED) , a condition in which males are unable to get or keep an erection firm enough for satisfactory sexual intercourse.

Few studies have looked at how obesity may affect female sexual function by contributing to problems such as loss of sexual desire, being unable to become or stay aroused, being unable to have an orgasm, or having pain during sex. 30 But research suggests that healthy eating, increased physical activity, and weight loss may help reduce sexual function problems in people with obesity. 29,30

In addition to increasing the risk for developing physical health problems, obesity can also affect mental health, increasing the risk for developing 31

- long-term stress

- body image problems

- low self-esteem

- eating disorders

Studies show that people with overweight or obesity are also likely to face weight-related bias at school and work, which may cause long-term harm to their quality of life. 31 Losing excess weight has been found to improve body image and self-esteem and reduce symptoms of depression. 32

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.2(4); Oct-Dec 2014

Prevention of overweight and obesity in adult populations: a systematic review

Leslea peirson.

1 McMaster Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre, Hamilton, Ont.

James Douketis

2 Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

3 St. Joseph’s HealthCare Hamilton, Hamilton, Ont.

Donna Ciliska

Donna fitzpatrick-lewis, muhammad usman ali, parminder raina, associated data.

The prevalence of normal-weight adults is decreasing, and the proportion in excessive weight categories (body mass index ≥ 25) is increasing. In this review, we sought to identify interventions to prevent weight gain in normal-weight adults.

We searched multiple databases from January 1980 to June 2013. We included randomized trials of primary care–relevant behavioural, complementary or alternative interventions for preventing weight gain in normal-weight adults that reported weight change at least 12 months after baseline. We included any studies reporting harms. We planned to extract and pool data for 4 weight outcomes, 6 secondary health outcomes and 5 adverse events categories.

One small study provided moderate-quality evidence. The 12-month program, which used education and financial strategies and was offered more than 25 years ago in the United States, was successful in stabilizing weight and producing weight loss. More intervention participants maintained their baseline weight or lost weight than controls (82% v. 56%, p < 0.0001), and program participants maintained their weight better than controls by showing greater weight reduction by the end of the intervention (mean difference adjusted for height –0.82, 95% confidence interval –1.57 to –0.06, kg). No evidence was available for sustained effects or for any other weight outcomes, secondary outcomes or harms.

Interpretation

We were unable to determine whether behavioural interventions led to weight-gain prevention and improved health outcomes in normal-weight adults. Given the importance of primary prevention, and the difficulty of losing weight and maintaining weight loss, this paucity of evidence is surprising and leaves clinicians and public health practitioners with unclear direction. Registration: PROSPERO no. CRD42012002753

Overweight and obesity (body mass index [BMI] 25–29.9 and ≥ 30, respectively), are global problems with increasing prevalence in most countries. 1 Excess adiposity is related to a considerable increase in morbidity 2 – 4 and premature mortality. 5 , 6 The natural history of weight changes in adults has not been well studied, but data were collected on Canadian adults and analyzed for changes between 1996/97 and 2004/05. 7 The overall change was average gain of 4 kg for men and 3.4 kg for women. 7 Similarly, a large cohort study in the United States found that nonobese adults gain, on average, 0.8 lb (about 0.36 kg) annually. 8 Another Canadian-based study showed that the prevalence of normal-weight adults decreased by almost 7% between 2000/01 and 2011, and the authors predicted a continued decline in this weight category, estimating that more than 55% of the adult population would be overweight or obese by 2019. 9

Although a number of groups have produced clinical guidelines for overweight and obesity, there is an identified gap in knowledge regarding interventions that help maintain normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9). 10 – 15 Prevention is ideal, but it is not clear whether interventions for normal-weight people can prevent weight gain. We conducted a systematic review to address whether primary care–relevant interventions for normal-weight adults led to short-term or sustained weight-gain prevention or improved health outcomes.

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (no. CRD42012002753) ( www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero ).

Search strategy

We searched Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PsycINFO from January 1980 to June 2013. The MEDLINE search strategy is provided as an example in Appendix 1 (available at http://www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E268/suppl/DC1 ). References of primary studies included in this review and related systematic reviews were searched for studies not captured by our search.

PICOS statement

The PICOS (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, setting) framework was as follows: (P) normal-weight adults aged 18 years or older; (I) behavioural, complementary or alternative interventions for weight-gain prevention; (C) no intervention, usual care or minimal component; (O) change in weight, BMI, waist circumference or total body fat percentage, change in secondary health outcomes (lipids, glucose, blood pressure), and harms of interventions; and (S) generalizable to Canadian primary care settings. Additional details are provided in Box 1 .

Population, intervention, comparator, outcomes and setting

• Normal-weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) adults aged ≥ 18 yr

Interventions

• Behavioural (diet, exercise and/or lifestyle), complementary or alternative (e.g., acupuncture, chiropractic, herbal supplements) interventions for preventing weight gain

Intervention effectiveness

• No intervention, usual care or minimal intervention (e.g., newsletter or single information session on healthy living)

Intervention harms

• Any type of comparison group or no comparison group

• Primary weight outcomes: change in weight (kg), BMI and waist circumference; total body fat percentage; secondary health outcomes: change in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, incidence of type 2 diabetes, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure

• Labelling; disordered eating; psychological distress, such as anxiety, depression and stigma; nutritional deficits; cost burden

• Generalizable to Canadian primary care settings, or feasible for conducting in or referral from primary care; interventions should be initiated through (or feasible within) a primary care setting and (could be) delivered by a health care professional (e.g., physician, psychologist, nurse, dietician)

Note: BMI = body mass index.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Box 2 .

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

• Intervention involved a behavioural, complementary and/or alternative strategy for weight-gain prevention; behavioural interventions could include diet, exercise and/or lifestyle strategies (lifestyle strategies were typically referred to as such by study authors and often included counselling, education or support, and environmental changes in addition to diet and/or exercise); complementary and alternative interventions included strategies such as acupuncture, chiropractic treatment and herbal supplements

• Intervention targeted adults aged ≥ 18 yr with normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9)

• Population was unselected, selected for low cardiovascular disease risk, or selected for increased risk for cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia or type 2 diabetes; population could include some (but not all) people with cardiovascular disease

• Randomized controlled trial with no intervention, usual care or minimal component (e.g., single newsletter or information session on general health) comparison group (condition applied only to studies assessing intervention effectiveness)

• Sample included at least 30 participants per arm at both baseline and the minimum outcome assessment point

• Reported data for 1 or more specified weight outcomes [i.e., change in weight (kg), BMI, waist circumference, total body fat percentage]

• Reported data for outcomes of interest at least 12 mo after baseline assessment

• No restrictions on study design, comparison group, number of participants, weight outcome reporting or timing of assessment were applied to studies that reported data for harms

• Results were published in English or French

Studies were excluded for the following reasons:

• Intervention involved a faith-based approach, a pharmacologic strategy or a surgical procedure

• Intervention targeted people who were underweight (BMI < 18.5), or overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25)

• Population was limited to participants with cardiovascular disease, or specifically enrolled participants who were pregnant, had an eating disorder or a condition that predisposes weight gain (e.g., metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome)

• Intervention was conducted in an in-patient hospital, institutional, school or occupational setting, or any setting deemed not generalizable to primary care, such as those with existing social networks among participants or the ability to offer intervention elements that could not be replicated in a primary health care setting; clinical institutions (hospital, metabolic units) were excluded because we believed these were unlikely to be primary prevention programs and would mostly include overweight or obese people

• Design was a case report, case series or chart review

• Only available results were published in a language other than English or French

Study selection, quality assessment and data abstraction

Titles and abstracts of papers were reviewed independently in duplicate. Any citation marked for inclusion by either team member went to full-text screening, which was also done independently in duplicate. Randomized trials were assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. 16 Overall, strength of the evidence (assessed as high, moderate, low or very low quality) was determined using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework (GRADEpro version 3.2). One team member completed full data abstraction and a second verified all extractions. All data were re-verified before analyses. Interrater disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis plan

For meta-analyses, we planned to use posttreatment means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous outcomes (e.g., weight in kg) and number-of-events data for binary outcomes (e.g., incidence of type 2 diabetes). We intended to use the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model with inverse variance method to generate summary measures of effect as mean difference for continuous outcomes and risk ratio for binary outcomes. 17 For studies that did not report SDs, we planned to calculate this value from the reported standard error (SE) of the mean, or from the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). 18 For studies that provided neither SDs nor SEs for follow-up data, we would impute the SD from baseline values or included studies of similar sample size and for the same outcome. For studies with more than one intervention arm (e.g., 2 diet plus exercise arms, one community-based group and one correspondence course), we planned to pool the data to do a pair-wise comparison with the control group. Alternatively, if groups were substantively different (e.g., low-calorie diet, high-intensity aerobic exercise), we intended to include the data for each arm compared with the control group but split the sample size for the control group to avoid a unit-of-analysis error and double counting. 16 Weight reported in pounds was to be converted to kilograms. Similarly, if total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins and fasting glucose were reported in mg/dL, they would be converted to Canadian standard units (i.e., mmol/L). We planned to use the Cochran Q (α = 0.10) and I 2 statistic to quantify heterogeneity within and between subgroups. If sufficient data were available, sensitivity analyses would be performed to evaluate statistical stability and effect on statistical heterogeneity. Subanalyses were to be based on the following: type of intervention (diet, exercise, diet plus exercise, lifestyle), intervention duration (≤□12 mo, > 12 mo), sex, baseline cardiovascular disease risk status (high risk: identified risk factors and/or diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia; low risk; unselected population; or not specified) and the study’s risk-of-bias rating (high, unclear, low).

The database search located 31 974 unique studies. Manual searches and reviews of reference lists from recent (published 2012–2013) relevant systematic reviews located 15 additional studies. After full-text screening, only one study was located that met the inclusion criteria for this review ( Figure 1 ).

Selection of studies on interventions to prevent weight gain in normal-weight adults.

Included study

We found one trial that met the inclusion criteria for a normal-weight population. 19 Twenty-five other studies were excluded because of samples of mixed-weight populations; this indirect evidence is reported in the adult overweight and obesity prevention review we prepared for the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. 20 The included pilot study was a randomized controlled trial of a 12-month education- and incentive-based intervention conducted in the US state of Minnesota in the 1980s. The study involved collaboration between researchers in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota and staff at a local health department. A staged recruitment strategy began with mailed invitations to a random sample of 3000 adults out of about 6000 who attended a centre for cardiovascular risk factor screening in the previous 18 months and whose weight was recorded as normal (i.e., < 115% ideal weight as per 1983 Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tables). Because of study limitations, only 61% of those who indicated interest (422/690) were invited to attend an orientation session, and 219 people were enrolled (110 assigned to the intervention group; 109 assigned to the control group). Based on measures taken at the screening visit, the sample was 71% female, mean age was 45.9 years, mean BMI was 23.1, mean systolic blood pressure was 114.1 mm Hg, mean diastolic blood pressure was 69.8 mm Hg, mean serum cholesterol level was 4.9 mmol/L and 8% of the participants smoked. The only significant baseline difference between intervention and control groups was the percentage of participants with prior involvement in formal weight-control programs (18% intervention, 30% control).

To raise awareness, participants in the Pound of Prevention pilot program ( n = 110) were mailed monthly newsletters containing information about weight-related issues (e.g., diet, exercise, psychology of weight management, association between weight and health). To encourage regular self-monitoring, on a monthly basis they were asked to mail a record of their weight and a description of any weight-control strategies they were using. To increase motivation, a financial incentive system was set up to withdraw $10 per month from each intervention participant’s personal bank account. The accumulated money was reimbursed with interest at any time on request or at the end of the 1-year study, on the condition that the participant’s weight did not increase from baseline. Finally, about 6 months into the program a 4-session mini-course was offered to provide more extensive information and assistance on managing and losing weight through diet and exercise. Although open to all intervention participants, these sessions were primarily intended for those who experienced weight gain or who were unhappy about the amount of weight they gained during the first half of the program. Control participants ( n = 109) had no contact with the program other than attending the orientation session when baseline measures were collected before group assignment and attending a follow-up visit for the 1-year outcome assessment.

There were insufficient trials to perform meta-analyses for any outcomes.

The included study 19 reported only weight change in pounds (converted here to kilograms). All but 9 participants were included in the analysis. Five program participants dropped out because they moved and 2 discontinued their involvement for unspecified reasons. Two control participants were excluded from the analysis because medical conditions prevented taking weight measurements. More intervention participants ( n = 103) maintained their baseline weight or lost weight during the 12-month intervention than control participants ( n = 108) (82% v. 56%, p < 0.0001). Although both groups showed an overall reduction in weight from the baseline to postintervention assessments, our calculations show that program participants had a greater reduction in weight by the end of the intervention (mean difference adjusted for height –0.82, 95% CI –1.57 to –0.06, kg). No data were available to assess maintenance of weight-gain prevention, intervention effects on any other weight-related or secondary health outcomes, or adverse effects of program participation.