Home — Essay Samples — History — Declaration of Independence — The Declaration Of Independence Thesis Analysis

The Declaration of Independence Thesis Analysis

- Categories: American History Declaration of Independence

About this sample

Words: 868 |

Published: Mar 5, 2024

Words: 868 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1143 words

2 pages / 834 words

1 pages / 619 words

2 pages / 1082 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence stands as a testament to the enduring principles and values upon which the United States was founded. At its core, this historical document reflects the profound impact of the Enlightenment period [...]

The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important documents in American history. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, it formally announced the thirteen American [...]

"Declaration of Independence." History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2021, www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/declaration-of-independence. Accessed 28 July 2021. Paine, [...]

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, is a cornerstone document in American history, symbolizing the colonies' struggle for freedom and justice. It eloquently articulates the principles of individual liberty [...]

The July 4, 1776, Declaration of Independence document authored by the US Congress is undeniably one of the most important historical primary sources in the US. The document says that human beings are equal, and it is God’s plan [...]

The Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson in 1776, is a significant document in American history. It not only declared independence from British rule but also outlined the rights and principles that should [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Toward independence

- The nature and influence of the Declaration of Independence

- Text of the Declaration of Independence

What is the Declaration of Independence?

where was the declaration of independence signed, where is the declaration of independence, how is the declaration of independence preserved.

- What were John Adams’s accomplishments?

Declaration of Independence

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University - Declaration of Independence

- National Archives - Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

- Bill of Rights Institute - Declaration of Independence (1776)

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Declaration of Independence

- Architect of the Capitol - Declaration of Independence

- Salt Lake Community College Pressbooks - Attenuated Democracy - Deism, the Indigenous Critique, Natural Rights, and the Declaration of Independence

- U.S. Department of State - Office of the Historian - The Declaration of Independence, 1776

- USHistory.org - The Declaration of Independence

- Khan Academy - The Declaration of Independence

- Declaration of Independence - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Declaration of Independence - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

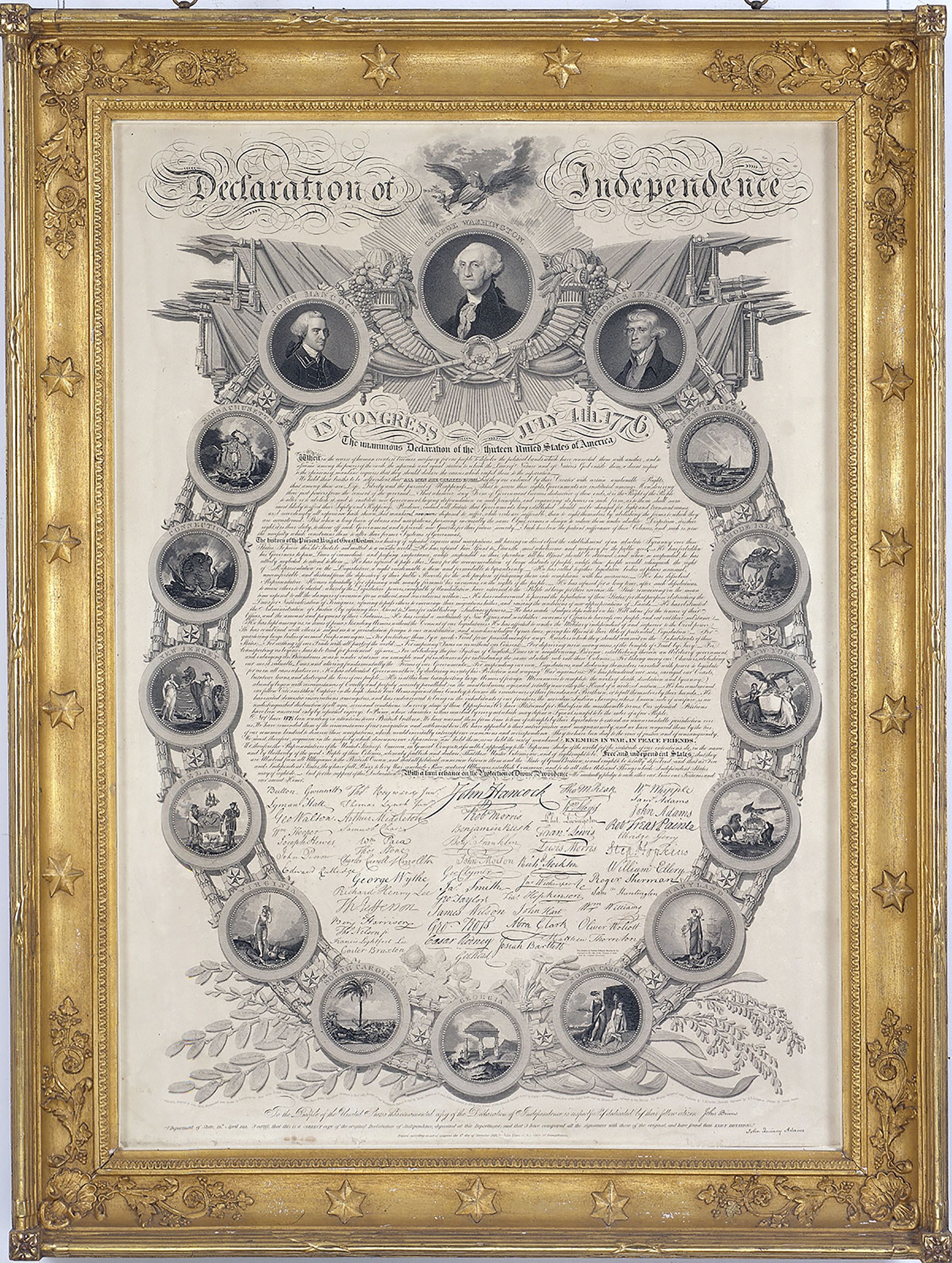

The Declaration of Independence, the founding document of the United States, was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. It explained why the Congress on July 2 “unanimously” (by the votes of 12 colonies, with New York abstaining) had resolved that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be Free and Independent States.”

On August 2, 1776, roughly a month after the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, an “engrossed” version was signed at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall ) in Philadelphia by most of the congressional delegates (engrossing is rendering an official document in a large clear hand). Not all the delegates were present on August 2. Eventually, 56 of them signed the document. Two delegates, John Dickinson and Robert R. Livingston , never signed.

Since 1952 the original parchment document of the Declaration of Independence has resided in the National Archives exhibition hall in Washington, D.C. , along with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights . Before then it had a number of homes and protectors, including the State Department and the Library of Congress . For a portion of World War II it was kept in the Bullion Depository at Fort Knox , Kentucky.

In the 1920s the Declaration of Independence was enclosed in a frame of gold-plated bronze doors and covered with double-paned plate glass with gelatin films between the plates to block harmful light rays. Today it is held in an upright case constructed of ballistically tested glass and plastic laminate. A $3 million camera and computerized system monitor the condition of the Declaration of Independence, Constitution , and Bill of Rights .

Recent News

Declaration of Independence , in U.S. history, document that was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and that announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. It explained why the Congress on July 2 “unanimously” by the votes of 12 colonies (with New York abstaining) had resolved that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be Free and Independent States.” Accordingly, the day on which final separation was officially voted was July 2, although the 4th, the day on which the Declaration of Independence was adopted, has always been celebrated in the United States as the great national holiday—the Fourth of July , or Independence Day .

On April 19, 1775, when the Battles of Lexington and Concord initiated armed conflict between Britain and the 13 colonies (the nucleus of the future United States), the Americans claimed that they sought only their rights within the British Empire . At that time few of the colonists consciously desired to separate from Britain. As the American Revolution proceeded during 1775–76 and Britain undertook to assert its sovereignty by means of large armed forces, making only a gesture toward conciliation, the majority of Americans increasingly came to believe that they must secure their rights outside the empire. The losses and restrictions that came from the war greatly widened the breach between the colonies and the mother country; moreover, it was necessary to assert independence in order to secure as much French aid as possible.

On April 12, 1776, the revolutionary convention of North Carolina specifically authorized its delegates in the Congress to vote for independence. On May 15 the Virginia convention instructed its deputies to offer the motion—“that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States”—which was brought forward in the Congress by Richard Henry Lee on June 7. John Adams of Massachusetts seconded the motion. By that time the Congress had already taken long steps toward severing ties with Britain. It had denied Parliamentary sovereignty over the colonies as early as December 6, 1775, and on May 10, 1776, it had advised the colonies to establish governments of their own choice and declared it to be “absolutely irreconcilable to reason and good conscience for the people of these colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations necessary for the support of any government under the crown of Great Britain,” whose authority ought to be “totally suppressed” and taken over by the people—a determination which, as Adams said, inevitably involved a struggle for absolute independence.

The passage of Lee’s resolution was delayed for several reasons. Some of the delegates had not yet received authorization to vote for separation; a few were opposed to taking the final step; and several men, among them John Dickinson , believed that the formation of a central government, together with attempts to secure foreign aid , should precede it. However, a committee consisting of Thomas Jefferson , John Adams, Benjamin Franklin , Roger Sherman , and Robert R. Livingston was promptly chosen on June 11 to prepare a statement justifying the decision to assert independence, should it be taken. The document was prepared, and on July 1 nine delegations voted for separation, despite warm opposition on the part of Dickinson. On the following day at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) in Philadelphia , with the New York delegation abstaining only because it lacked permission to act, the Lee resolution was voted on and endorsed . (The convention of New York gave its consent on July 9, and the New York delegates voted affirmatively on July 15.) On July 19 the Congress ordered the document to be engrossed as “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America.” It was accordingly put on parchment , probably by Timothy Matlack of Philadelphia. Members of the Congress present on August 2 affixed their signatures to this parchment copy on that day and others later.

The signers were as follows: John Hancock (president), Samuel Adams , John Adams, Robert Treat Paine , and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts; Button Gwinnett , Lyman Hall, and George Walton of Georgia; William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, and John Penn of North Carolina; Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch , Jr., and Arthur Middleton of South Carolina; Samuel Chase , William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Maryland; George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison , Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Carter Braxton of Virginia; Robert Morris , Benjamin Rush , Benjamin Franklin, John Morton , George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson , and George Ross of Pennsylvania; Caesar Rodney and George Read of Delaware; William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, and Lewis Morris of New York; Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon , Francis Hopkinson , John Hart, and Abraham Clark of New Jersey; Josiah Bartlett , William Whipple, and Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire; Stephen Hopkins and William Ellery of Rhode Island; and Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington , William Williams , and Oliver Wolcott of Connecticut . The last signer was Thomas McKean of Delaware , whose name was not placed on the document before 1777.

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

Thomas Jefferson Declaration of Independence: Right to Institute New Government

Through the many revisions made by Jefferson, the committee, and then by Congress, Jefferson retained his prominent role in writing the defining document of the American Revolution and, indeed, of the United States. Jefferson was critical of changes to the document, particularly the removal of a long paragraph that attributed responsibility of the slave trade to British King George III. Jefferson was justly proud of his role in writing the Declaration of Independence and skillfully defended his authorship of this hallowed document.

Influential Precedents

Instructions to virginia's delegates to the first continental congress written by thomas jefferson in 1774.

Thomas Jefferson, a delegate to the Virginia Convention from Albemarle County, drafted these instructions for the Virginia delegates to the first Continental Congress. Although considered too radical by the Virginia Convention, Jefferson's instructions were published by his friends in Williamsburg. His ideas and smooth, eloquent language contributed to his selection as draftsman of the Declaration of Independence. This manuscript copy contains additional sections and lacks others present in the published version, A Summary View of the Rights of British America.

Thomas Jefferson. Instructions to Virginia's Delegates, 1774. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (39)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#039

Fairfax County Resolves, July 18, 1774

The Fairfax County Resolves were written by George Mason (1725–1792) and George Washington (1732/33–1799) and adopted by a Fairfax County Convention chaired by Washington and called to protest Britain's harsh measures against Boston. The resolves are a clear statement of constitutional rights considered to be fundamental to Britain's American colonies. The Resolves call for a halt to trade with Great Britain, including an end to the importation of slaves. Jefferson tried unsuccessfully to include in the Declaration of Independence a condemnation of British support of the slave trade.

George Mason and George Washington. Fairfax County Resolves, 1774. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (40)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#040

George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted by George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee (1730–1778) and adopted unanimously in June 1776 during the Virginia Convention in Williamsburg that propelled America to independence. It is one of the documents heavily relied on by Thomas Jefferson in drafting the Declaration of Independence. The Virginia Declaration of Rights can be seen as the fountain from which flowed the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The document exhibited here is Mason's first draft to which Thomas Ludwell Lee added several clauses. Even a cursory examination of Mason's and Jefferson's declarations reveal the commonality of language and principle.

George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee. Draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (41)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#041

Thomas Jefferson's Draft of a Constitution for Virginia, predecessor of The Declaration Of Independence

Immediately on learning that the Virginia Convention had called for independence on May 15, 1776, Jefferson, a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress, wrote at least three drafts of a Virginia constitution. Jefferson's drafts are not only important for their influence on the Virginia government, they are direct predecessors of the Declaration of Independence. Shown here is Jefferson's litany of governmental abuses by King George III as it appeared in his first draft.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Virginia Constitution, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (45)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#045

The Fragment

Fragment of the earliest known draft of the declaration, june, 1776.

This is the only surviving fragment of the earliest draft of the Declaration of Independence. This fragment demonstrates that Jefferson heavily edited his first draft of the Declaration of Independence before he prepared a fair copy that became the basis of “the original Rough draught.” None of the deleted words and passages in this fragment appears in the “Rough draught,” but all of the undeleted 148 words, including those careted and interlined, were copied into the “Rough draught” in a clear form.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft fragment of the Declaration of Independence, 1776, Manuscript. Manuscript Division (48)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#048

The Rough Draft

Original rough draft of the declaration.

Written in June 1776, Thomas Jefferson's draft of the Declaration of Independence, included eighty-six changes made later by John Adams (1735–1826), Benjamin Franklin 1706–1790), other members of the committee appointed to draft the document, and by Congress. The “original Rough draught” of the Declaration of Independence, one of the great milestones in American history, shows the evolution of the text from the initial composition draft by Jefferson to the final text adopted by Congress on the morning of July 4, 1776. At a later date perhaps in the nineteenth century, Jefferson indicated in the margins some but not all of the corrections suggested by Adams and Franklin. Late in life Jefferson endorsed this document: “Independence Declaration of original Rough draught.”

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Declaration of Independence, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (49)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#049

Back to top

The Graff House where Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence

The house of Jacob Graff, brick mason, located at the southwest corner of Market and Seventh Street, Philadelphia, was the residence of Thomas Jefferson when he drafted the Declaration of Independence. The three-story brick house is pictured here in Harper's Weekly, April 7, 1883. Jefferson rented the entire second floor for himself and his household staff.

Harper's Weekly, April 7, 1883. Reproduction of journal page. Prints and Photographs Division (43)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#043

Submitting the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress, June 28, 1776

This image is considered one of the most realistic renditions of this historical event. Jefferson is the tall person depositing the Declaration of Independence on the table. Benjamin Franklin sits to his right. John Hancock (1737–1793) sits behind the table. Fellow committee members, John Adams, Roger Sherman (1721–1793), and Robert R. Livingston (1746–1813) stand (left to right) behind Jefferson.

Edward Savage and/or Robert Edge Pine. Congress Voting the Declaration of Independence, c. 1776. Copyprint of oil on canvas, Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (53)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#053

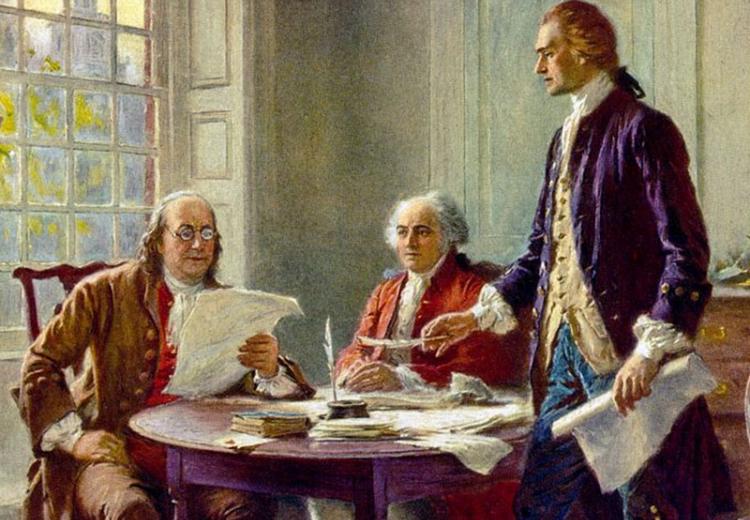

The “Declaration Committee,” chaired by Thomas Jefferson

On June 11, 1776, anticipating that the vote for independence would be favorable, Congress appointed a committee to draft a declaration: Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and John Adams of Massachusetts. Currier and Ives prepared this imagined scene for the one hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Currier and Ives. The Declaration Committee, New York, 1876. Copyprint of lithograph. Prints and Photographs Division (56)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#056

The Final Document

George washington's copy of the declaration of independence.

This is the surviving fragment of John Dunlap's initial printing of the Declaration of Independence, which was sent to George Washington by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress on July 6, 1776. General Washington had the Declaration read to his assembled troops in New York on July 9. Later that night the Americans destroyed a bronze statue of Great Britain's King George III, which stood at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green.

[ In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration By the Representatives of the United States of America, In General Congress Assembled. ] [Philadelphia: John Dunlap, July 4, 1776]. Broadside with broken at lines 34 and 54 with text below line 54 missing. Manuscript Division (51)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#051

Independence Hall

Congress voted for Independence in the Pennsylvania State House located on Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Charles Willson Peale painted this northwest view of the state house and its sheds in 1778. The building was ornamented by two clocks and a steeple, which was removed shortly after the British left Philadelphia in 1778.

James Trenchard after a painting by Charles Willson Peale. A NW View of the State House in Philadelphia in Columbian Magazine, 1787. Copyprint of engraving. Rare Book & Special Collections Division (44)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#044

Prospect of Philadelphia

This is a view of the city of Philadelphia in 1768 from the Jersey shore, with a street map and an enlarged engraving of the State House and the River Battery. Jefferson would have seen Philadelphia, as depicted, when he visited Annapolis, Philadelphia, and New York in 1766. The Philadelphia skyline had not dramatically changed when Jefferson returned in 1775.

George Heap under the direction of Nicholas Scull, surveyor general of Pennsylvania. Prospect of the City of Philadelphia, 1768. Copyprint of map and engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (6)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#006

Destroying the statue of King George III

After hearing the Declaration of Independence read on July 9, the American army destroyed the statue of King George III at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green in New York City.

John C. McRae after Johnannes A. Oertel. Pulling down the statue of George III by the “Sons of Freedom,” at the Bowling Green, City of New York, July 1776. New York : Published by Joseph Laing, [ca. 1875] Copyprint of engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (52)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#052

First public reading of the Declaration of Independence

Pennsylvania militia colonel John Nixon (1733–1808) is portrayed in the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence on July 6, 1776. This scene was created by William Hamilton after a drawing by George Noble and appeared in Edward Barnard, History of England (London, 1783).

The Manner in Which the American Colonies Declared Themselves Independent of the King of England, Throughout the Different Provinces, on July 4, 1776. Copyprint of etching. Prints and Photographs Division (57)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#057

The Aftermath

Jefferson's draft of the declaration of independence, as reported to congress.

This copy of the Declaration represents the fair copy that the committee presented to Congress. Jefferson noted that “the parts struck out by Congress shall be distinguished by a black line drawn under them, & those inserted by them shall be placed in the margin or in a concurrent column.” Despite its importance in the story of the evolution of the text, this copy of the Declaration has received very little public attention.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Declaration of Independence, 1776. Manuscript. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p2.jpg ">Page 2 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p3.jpg ">Page 3 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p4.jpg ">Page 4 . Manuscript Division (50)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#050

Jefferson consoled for his “mangled” manuscript

Thomas Jefferson sent copies of the Declaration of Independence to a few close friends, such as Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794), indicating the changes that had been made by Congress. Lee, replied: “I wish sincerely, as well for the honor of Congress, as for that of the States, that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it is. It is wonderful, and passing pitiful, that the rage of change should be so unhappily applied. However the Thing is in its nature so good, that no Cookery can spoil the Dish for the palates of Freemen.”

Richard Henry Lee to Thomas Jefferson, July 21, 1776. Manuscript letter. Manuscript Division (54)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#054

The Goddess Of Liberty

In this allegorical print, the Goddess of Liberty points to Thomas Jefferson's portrait while gazing at the portrait of George Washington. It was made late in Jefferson's second presidential administration. The cupids here are the Genius of Peace and the Genius of Gratitude, and in this context Jefferson is “Liberty's Genius.”

The Goddess of Liberty with a Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, Salem, Massachusetts, January 15, 1807. Copyprint of painting. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, the Mabel Brady Garvan Collection (32)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#032

Thomas Jefferson's portable writing desk

The Declaration of Independence was composed on this mahogany lap desk, designed by Jefferson and built by Philadelphia cabinet maker Benjamin Randolph. Jefferson gave it to Joseph Coolidge, Jr. (1798–1879) when he married Ellen Randolph, Jefferson's granddaughter. In giving it, Jefferson wrote on November 18, 1825: “Politics, as well as Religion, has it's superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day give imaginary value to this relic, for it's association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence.” Coolidge replied, on February 27, 1826, that he would consider the desk “no longer inanimate, and mute, but as something to be interrogated and caressed.”

Benjamin Randolph after a design by Thomas Jefferson. Portable writing desk, Philadelphia, 1776. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (30)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#030

Thomas Jefferson's monogrammed silver pen

Thomas Jefferson ordered this small cylindrical silver fountain pen with a gold nib from his agent in Richmond, Virginia. It was probably made by William Cowan (1779–1831), a Richmond watchmaker. An elliptical cap that screws into the end of the cylinder and caps the ink reservoir is engraved “TJ”.

Probably by William Cowan. Silver pen, Richmond, Virginia, c.1824. Courtesy of the Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc. (31)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#031

Lord Kames, Henry Home, Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion

This is Jefferson's personal copy of the Scottish moral philosopher's work and is one of the few books annotated by Jefferson. Lord Kames (1696–1782) was a leader of the “moral sense” school, that advocated that men had an inner sense of right and wrong. Lord Kames provided the philosophical foundation of the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” which was appropriated by Jefferson as an inalienable right of mankind in the Declaration of Independence.

Lord Kames (Henry Home). Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion. Two parts. Edinburgh: R. Fleming, for A. Kincaid and A. Donaldson, 1751. Rare Book and Special Collections Division (34)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#034

Algernon Sidney, Discourses Concerning Government

Jefferson considered Algernon Sidney's (1622–1683) Discourses the best fundamental textbook on the principles of government. In a December 13, 1804 letter to Mason Weems, Jefferson commented that “they are in truth a rich treasure of republican principles . . . it is probably the best elementary book of the principles of government.” Sidney was a republican executed by the British for seditious writings including the Discourses. This is Jefferson's personal copy which was sold to Congress in 1815.

Algernon Sidney. Discourses Concerning Government by Algernon Sidney with his Letters, Trial Apology and some Memoirs of His Life. London: Printed for A. Millar, 1763. Rare Book and Special Collections Division (35)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#035

Liberty And Science

Thomas Jefferson is pictured, at the beginning of his first presidential term, holding the Declaration of Independence with scientific instruments in the background. Tiebout used the bust portrait of Rembrandt Peale and created an imaginary full-body, because no standing portrait of Jefferson had been painted.

Cornelius Tiebout. Thomas Jefferson: President of the United States, Philadelphia, 1801. Copyprint of engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (95)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#095

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Argument of the Declaration of Independence

Thomas Jefferson (right), Benjamin Franklin (left), and John Adams (center) meet at Jefferson's lodgings, on the corner of Seventh and High (Market) streets in Philadelphia, to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence.

Wikimedia Commons

Long before the first shot was fired, the American Revolution began as a series of written complaints to colonial governors and representatives in England over the rights of the colonists.

In fact, a list of grievances comprises the longest section of the Declaration of Independence. The organization of the Declaration of Independence reflects what has come to be known as the classic structure of argument—that is, an organizational model for laying out the premises and the supporting evidence, the contexts and the claims for argument.

According to its principal author, Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration was intended to be a model of political argument. On its 50th anniversary, Jefferson wrote that the object of the Declaration was “[n]ot to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent , and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take.”

Guiding Questions

What kind of a document is the Declaration of Independence?

How do the parts and structure of the document make for a good argument about the necessity of independence?

What elements of the Declaration of Independence have been fulfilled and what remains unfulfilled?

Learning Objectives

Analyze the Declaration of Independence to understand its structure, purpose, and tone.

Analyze the items and arguments included within the document and assess their merits in relation to the stated goals.

Evaluate the short and long term effects the Declaration of Independence on the actions of citizens and governments in other nations.

Lesson Plan Details

The American Revolution had its origin in the colonists’ concern over contemporary overreach by the King and Parliament as well as by their awareness of English historical precedents for the resolution of civic and political issues as expressed in such documents as (and detailed in our EDSITEment lesson on) the Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights.

The above video on the Prelude to Revolution addresses the numerous issues that were pushing some in the colonies toward revolution. For example, opponents of the Stamp Act of 1765 declared that the act—which was designed to raise money to support the British army stationed in America after 1763 by requiring Americans to buy stamps for newspapers, legal documents, mortgages, liquor licenses, even playing cards and almanacs—was illegal and unjust because it taxed Americans without their consent. In protesting the act, they cited the following prohibition against taxation without consent from the Magna Carta , written five hundred and fifty years earlier, in 1215: “No scutage [tax] ... shall be imposed..., unless by common counsel....” American resistance forced the British Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act in 1766. In the succeeding years, similar taxes were levied by Parliament and protested by many Americans.

In June 1776, when it became clear that pleas and petitions to the King and Parliament were useless, the members of the Continental Congress assigned the task of drafting a "declaration of independence" to a committee that included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Considered by his peers in the Congress and the committee as one of the most highly educated and most eloquent members of the Congress, Jefferson accepted the leadership of the committee.

For days, he labored over the draft, working meticulously late into the evenings at his desk in his lodging on Market Street in Philadelphia, carefully laying out the charges against His Majesty King George III, of Great Britain and the justification for separation of the colonies. Franklin and Adams helped to edit Jefferson’s draft. After some more revisions by the Congress, the Declaration was adopted on July 4. It was in that form that the colonies declared their independence from British rule.

What is an Argument? An argument is a set of claims that includes 1) a conclusion; and 2) a set of premises or reasons that support it. Both the conclusion(s) and premise(s) are “claims”, that is, declarative sentences that are offered by the author of the argument as "truth statements". A conclusion is a claim meant to be supported by premises, while a premise is a claim that operates as a "reason why," or a justification for the conclusion. All arguments will have at least one conclusion and one—and often more than one—premise in its support.

The above video from PBS Digital Studios on How to Argue provides an analysis of the art of persuasion and how to construct an argument. The focus on types of arguments begins at the 5:10 mark of the video.

In the first of this lesson’s three activities, students will develop a list of complaints about the way they are being treated by parents, teachers, or other students. In the second activity, they will prioritize these complaints and organize them into an argument for their position.

In the last activity, they will examine the Declaration of Independence as a model of argument, considering each of its parts, their function, and how the organization of the whole document aids in persuading the audience of the justice and necessity of independence. Students will then use what they have learned from examining the Declaration to edit their own list of grievances. Finally they will reflect on that editing process and what they have learned from it.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.8 Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

NCSS.D1.1.6-8. Explain how a question represents key ideas in the field.

NCSS.D2.Civ.3.6-8. Examine the origins, purposes, and impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements.

NCSS.D2.Civ.4.6-8. Explain the powers and limits of the three branches of government, public officials, and bureaucracies at different levels in the United States and in other countries.

NCSS.D2.Civ.5.6-8. Explain the origins, functions, and structure of government with reference to the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions, and selected other systems of government.

NCSS.D2.His.2.6-8. Classify series of historical events and developments as examples of change and/or continuity.

NCSS.D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.

NCSS.D2.His.4.6-8. Analyze multiple factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

Activity 2. Worksheet 1. So, What Are You Going to Do About It?

Activity 3. Worksheet 2. The Declaration of Independence in Six Parts

Assessment Section

Activity 1. Considering Complaints

Tell students that you have overheard them make various complaints at times about the way they are treated by some other teachers and other fellow students: complaints not unlike those that motivated the founding fathers at the time of the American Revolution. Explain that even though adults have the authority to restrict some of their rights, this situation is not absolute. Also point out that fellow students do not have the right to “bully” or take advantage of them.

- Arrange students in small groups of 2–3 and give them five minutes to list complaints on a sheet of paper about the way they’re treated by some adults or other students. Note that the complaints should be of a general nature (for example: recess should be longer; too much busy-work homework; high school students should be able to leave campus for lunch; older students shouldn’t intimidate younger students, etc.).

- Collect the list. Choose a selection of complaints that will guide the following class discussion. Save the lists for future reference.

- Preface the discussion by remarking that there are moments when all of us are more eager to express what's wrong than we are to think critically about the problem and possible solutions. There is no reason to think people were any different in 1776. It's important to understand the complaints of the colonists as one step in a process involving careful deliberation and attempts to redress grievances.

Use these questions to help your students consider their concerns in a deliberate way:

- WHO makes the rules they don't like?

- WHO decides if they are fair or not?

- WHAT gives the rule-maker the right to make the rules?

- HOW does one get them changed?

- WHAT does it mean to be independent from the rules? and finally,

- HOW does a group of people declare that they will no longer follow the rules?

Exit Ticket: Have students write down their complaints as a list, identifying the reasons why the treatment under discussion is objectionable and organizing the list according to some principle, such as from less to more important. Let each student comment on one another student’s list and its organization.

View this satirical video entitled "Too Late to Apologize" about the motives for the Declaration of Independence as you transition to Activity Two.

Activity 2: So, What are You Going to Do About It?

Ask the students to imagine that, in the hope of effecting some changes, they are going to compose a document based on their complaints to be sent to the appropriate audience.

Divide the class into small groups of 2–3 students and distribute the handout, “ So, What Are You Going To Do About It? ” Tell students that before they begin to compose their “declaration” they should consider the questions on the handout. (Note: The questions correspond to the sections of the Declaration noted in parentheses. The Declaration itself will be discussed in Activity 3. This discussion serves as a prewriting activity for the writing assignment.)

Exit Ticket: Hold a general discussion with the class about the questions. Have individual groups respond to the questions in each of the sections and ask other groups to contribute.

Activity 3. The Parts of the “Declaration”

The Declaration of Independence was created in an atmosphere of complaints about the treatment of the colonies under British rule. In this activity students will identify and analyze the parts of the Declaration through a close reading. Students will also be given the opportunity to construct a document in the manner of the Declaration of Independence based on their own complaints.

Provide every student with a copy of the Declaration of Independence in Six Parts . Ask them to “scan” the entire document once to understand the parts and their function. After that they will be asked to reread the document this time more closely. Have students identify the six sections (below) by describing what is generally being said in each. Help students identify these sections with the following titles:

Preamble: the reasons WHY it is necessary to EXPLAIN their actions (from "WHEN, in the Course of human Events" to "declare the Causes which impel them to the Separation.")

Statement of commonly accepted principles: specifying what the undersigned believed, the philosophy behind the document (from "We hold these Truths to be self-evident" to "an absolute Tyranny over these States") which underlies the argument

List of Complaints: the offenses by King and Parliament that impelled the declaration (from "To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World" to "unfit to be the ruler of a free people")

Statements of prior attempts to redress grievances: (From "Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren," to "Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.")

Conclusion: (From "WE, therefore" to "and our sacred Honour.") Following from the principles held by the Americans, and the actions of the King and Parliament, the people have the right and duty to declare independence.

Oath: Without this oath on the part of the colonists dedicating themselves to securing independence by force of arms, the assertion would be mere parchment.

Exit Ticket: Have students arrange their constructed complaint into a master document (“Parts of Your Argument” section of worksheet 1) for further analysis by matching each section of their personal complaints to the above six corresponding sections of the Declaration.

As an assessment, students make a deeper analysis of the Declaration and compare their declarations to the founding document.

Divide the class into small groups of 3–4 students, each taking one of the Declaration’s sections, as defined in Activity 3. Distribute copies of the student handout, “Analyzing the Declaration of Independence.” Assign each group one of the sections and have them answer the questions from their section.

Guide students in understanding how their section of the Declaration of Independence corresponds to the relevant question of their personal declaration in Activity 3.

Once the groups have finished their handouts, have each report their findings to the class. As they listen to the other presentations, have students take notes to complete the entire handout.

For a final summing up, have students reflect on what they have learned about making an argument from the close study of Declaration’s structure.

- Have students conduct research into the historical events that led to the colonists' complaints and dissatisfaction with British rule. Direct students to the annotated Declaration of Independence on Founding.com which provides the historical context for each of the grievances. Ask them to identify and then list some of the specific complaints they have found. After reviewing the complaints, have students research specific historic events related to the grievances listed.

- The historical events students choose could also be added to a timeline by connecting an excerpt of a particular complaint to a brief, dated summary of an event. The complaints relate to actual events, but the precise events were not discussed in the Declaration. Why do the students think the framers decided to do that? ( Would the student declarations also be more effective without specific events tied to the complaints?

Materials & Media

Worksheet 1. declare the causes: what are you going to do about it, worksheet 2. declare the causes. the declaration of independence in six parts, related on edsitement, a more perfect union, declare the causes: the declaration of independence, the declaration of sentiments by the seneca falls conference (1848), not only paul revere: other riders of the american revolution.

Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which is celebrated in the US as Independence Day.

The Declaration was not considered a significant document until more than 50 years after its signing, as it was initially seen as a routine formality to accompany Congress' vote for independence. However, it has since become appreciated as one of the most important human rights documents in Western history. Largely influenced by Enlightenment ideals, particularly those of John Locke , the Declaration asserts that "all men are created equal" and are endowed with the "certain unalienable rights" to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness"; this has become one of the best-known statements in US history and has become a moral standard that the United States, and many other Western democracies, have since strived for. It has been cited in the push for the abolition of slavery and in many civil rights movements, and it continues to be a rallying cry for human rights to this day. Alongside the Articles of Confederation and the US Constitution, the Declaration of Independence was one of the most important documents to come out of the American Revolutionary era. This article includes a brief history of the factors that led the colonies to declare independence from Britain, as well as the complete text of the Declaration itself.

Road to Independence

For much of the early part of their struggle with Great Britain, most American colonists regarded independence as a final resort, if they even considered it at all. The argument between the colonists and the British Parliament, after all, largely boiled down to colonial identity within the British Empire ; the colonists believed that, as subjects of the British king and descendants of Englishmen, they were entitled to the same constitutional rights that governed the lives of those still in England . These rights, as expressed in the Magna Carta (1215), the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, and the Bill of Rights of 1689, among other documents, were interpreted by the Americans to include self-taxation, representative government, and trial by jury. Englishmen exercised these rights through Parliament, which, at least theoretically, represented their interests; since the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they attempted to exercise their own 'rights of Englishmen' through colonial legislative assemblies such as Virginia's House of Burgesses .

Parliament, however, saw things differently. It agreed that the colonists were Britons and were subject to the same laws, but it viewed the colonists as no different than the 90% of Englishmen who owned no land and therefore could not vote, but who were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament. Under this pretext, Parliament decided to directly tax the colonies and passed the Stamp Act in 1765. When the Americans protested that Parliament had no authority to tax them because they were not represented in Parliament, Parliament responded by passing the Declaratory Act (1766), wherein it proclaimed that it had the authority to pass binding legislation for all Britain's colonies "in all Cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). After doubling down, Parliament taxed the Americans once again with the Townshend Acts (1767-68). When these acts were met with riots in Boston, Parliament sent regiments of soldiers to restore the king's peace. This only led to acts of violence such as the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and acts of disobedience such as the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773).

While the focal point of the argument regarded taxation, the Americans believed that their rights were being violated in other ways as well. As mandated in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774, Britain announced that American dissidents would now be tried by Vice-Admiralty courts or shipped to England for trial, thereby depriving them of a jury of peers; British soldiers could be quartered in American-owned buildings; and Massachusetts' representative government was to be suspended as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, with a military governor to be installed. Additionally, there was the question of land; both the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 restricted the westward expansion of Americans, who believed they were entitled to settle the West. While the colonies viewed themselves as separate polities within the British Empire and would not view themselves as a single entity for many years to come, they had nevertheless become bound together over the years due to their shared Anglo background and through their military cooperation during the last century of colonial wars with France. Their resistance to Parliament only tied them closer together and, after the passage of the Intolerable Acts, the colonies announced support for Massachusetts and began mobilizing their militias.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, all thirteen colonies soon joined the rebellion and sent representatives to the Second Continental Congress, a provisional wartime government. Even at this late stage, independence was an idea espoused by only the most radical revolutionaries like Samuel Adams . Most colonists still believed that their quarrel was with Parliament alone, that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) secretly supported them and would reconcile with them if given the opportunity; indeed, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), regiments of American rebels reported for duty by announcing that they were "in his Majesty's service" (Boatner, 539). In August 1775, King George III dispelled such notions when he issued his Proclamation of Rebellion, in which he announced that he considered the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and ordered British officials to endeavor to "withstand and suppress such rebellion". Indeed, George III would remain one of the biggest advocates of subduing the colonies with military force; it was after this moment that Americans began referring to him as a tyrant and hope of reconciliation with Britain diminished.

Writing the Declaration

By the spring of 1776, independence was no longer a radical idea; Thomas Paine 's widely circulated pamphlet Common Sense had made the prospect more appealing to the general public, while the Continental Congress realized that independence was necessary to procure military support from European nations. In March 1776, the revolutionary convention of North Carolina became the first to vote in favor of independence, followed by seven other colonies over the next two months. On 7 June, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion putting the idea of independence before Congress; the motion was so fiercely debated that Congress decided to postpone further discussion of Lee's motion for three weeks. In the meantime, a committee was appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence, in the event that Lee's motion passed. This five-man committee was comprised of Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

The Declaration was primarily authored by the 33-year-old Jefferson, who wrote it between 11 June and 28 June 1776 on the second floor of the Philadelphia home he was renting, now known as the Declaration House. Drawing heavily on the Enlightenment ideas of John Locke, Jefferson places the blame for American independence largely at the feet of the king, whom he accuses of having repeatedly violated the social contract between America and Great Britain. The Americans were declaring their independence, Jefferson asserts, only as a last resort to preserve their rights, having been continually denied redress by both the king and Parliament. Jefferson's original draft was revised and edited by the other men on the committee, and the Declaration was finally put before Congress on 1 July. By then, every colony except New York had authorized its congressional delegates to vote for independence, and on 4 July 1776, the Congress adopted the Declaration. It was signed by all 56 members of Congress; those who were not present on the day itself affixed their signatures later.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America. When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to separation. Remove Ads Advertisement We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive toward these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such a form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. – Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. He has refused to Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. Remove Ads Advertisement He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws of Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. Love History? Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter! He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rules into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, be declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death , desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections against us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare , is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. – And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

The following is a list of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, many of whom are considered the Founding Fathers of the United States. John Hancock , as president of the Continental Congress, was the first to affix his signature. Robert R. Livingston was the only member of the original drafting committee to not also sign the Declaration, as he had been recalled to New York before the signing took place.

Massachusetts: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry.

New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton.

Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins , William Ellery.

Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott.

New York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris.

New Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark.

Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross.

Delaware: George Read, Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKean.

Maryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Virginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton.

North Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn.

South Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., Arthur Middleton.

Georgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Boatner, Mark M. Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence. London: Cassell, 1973., 1973.

- Britannica: Text of the Declaration of Independence , accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence - Signed, Writer, Date | HISTORY , accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence: A Transcription | National Archives , accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage, 1993.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the declaration of independence, who wrote the declaration of independence, who signed the declaration of independence, related content.

Second Continental Congress

Natural Rights & the Enlightenment

First Continental Congress

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Enlightenment

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2024, April 03). Declaration of Independence . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified April 03, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 03 Apr 2024. Web. 29 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 03 April 2024. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Research & Education

- Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia

Declaration of Independence

Who wrote the declaration of independence.

Thomas Jefferson is considered the primary author of the Declaration of Independence , although Jefferson's draft went through a process of revision by his fellow committee members and the Second Continental Congress.

HOW THE DECLARATION CAME ABOUT

America's declaration of independence from the British Empire was the nation's founding moment. But it was not inevitable. Until the spring of 1776, most colonists believed that the British Empire offered its citizens freedom and provided them protection and opportunity. The mother country purchased colonists' goods, defended them from Native American Indian and European aggressors, and extended British rights and liberty to colonists.

In return, colonists traded primarily with Britain, obeyed British laws and customs, and pledged their loyalty to the British crown. For most of the eighteenth century, the relationship between Britain and her American colonies was mutually beneficial. Even as late as June 1775, Thomas Jefferson said that he would "rather be in dependence on Great Britain, properly limited, than on any nation upon earth, or than on no nation." [1]

But this favorable relationship began to face serious challenges in the wake of the Seven Years' War. In that conflict with France, Britain incurred an enormous debt and looked to its American colonies to help pay for the war. Between 1756 and 1776, Parliament issued a series of taxes on the colonies, including the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Duties of 1766, and the Tea Act of 1773. Even when the taxes were relatively light, they met with stiff colonial resistance on principle, with colonists concerned that “taxation without representation” was tyranny and political control of the colonies was increasingly being exercised from London. Colonists felt that they were being treated as second-class citizens. But after initially compromising on the Stamp Act, Parliament supported increasingly oppressive measures to force colonists to obey the new laws. Eventually, tensions culminated in the shots fired between British troops and colonial militia at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

Despite the outbreak of violence, the majority of colonists wanted to remain British. Only when King George III failed to address colonists' complaints against Parliament or entertain their appeals for compromise did colonists begin to consider independence as a last resort. Encouraged by Thomas Paine ’s pamphlet, “Common Sense,” more and more colonists began to consider independence in the spring of 1776. At the same time, the continuing war and rumors of a large-scale invasion of British troops and German mercenaries diminished hopes for reconciliation.

While the issue had been discussed quietly in the corridors of the Continental Congress for some time, the first formal proposal for independence was not made in the Continental Congress until June 7, 1776. It came from the Virginian Richard Henry Lee, who offered a resolution insisting that "all political connection is, and ought to be, dissolved" between Great Britain and the American colonies. [2] But this was not a unanimous sentiment. Many delegates wanted to defer a decision on independence or avoid it outright. Despite this disagreement, Congress did nominate a drafting committee—the Committee of Five (John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman)—to compose a declaration of independence. Thomas Jefferson, known for his eloquent writing style and reserved manner, became the principal author.

The Declaration and the Committee of Five

As he sat at his desk in a Philadelphia boarding house, Jefferson drafted a "common sense" treatise in “terms so plain and firm, as to command [the] assent” of mankind. [3] Some of his language and many of his ideas drew from well-known political works, such as George Mason's Declaration of Rights. But his ultimate goal was to express the unity of Americans—what he called an "expression of the american mind"—against the tyranny of Britain. [4]

Jefferson submitted his "rough draught" of the Declaration on June 28. Congress eventually accepted the document, but not without debating the draft for two days and making extensive changes. (See edited draft at left.) Jefferson was unhappy with many of the revisions—particularly the removal of the passage on the slave trade and the insertion of language less offensive to Britons—and in later years would often provide his original draft to correspondents. Benjamin Franklin tried to reassure Jefferson by telling him the now-famous tale of a merchant whose storefront sign bore the words: "John Thompson, Hatter, makes and sells hats for ready money;" after a circle of critical friends offered their critiques, the sign merely read, "John Thompson" above a picture of a hat. [5]

Pressured by the news that a fleet of British troops lay off the coast of New York, Congress adopted the Lee resolution of independence on July 2nd, the day which John Adams always believed should be celebrated as American independence day, and adopted the Declaration of Independence explaining its action on July 4.

The Declaration was promptly published, and throughout July and August, it was spread by word of mouth, delivered on horseback and by ship, read aloud before troops in the Continental Army, published in newspapers from Vermont to Georgia, and dispatched to Europe. The Declaration roused support for the American Revolution and mobilized resistance against Britain at a time when the war effort was going poorly.

The Declaration provides clear and emphatic statements supporting self-government and individual rights, and it has become a model of such statements for several hundred years and around the world.

PRINTING AND SIGNING THE DECLARATION

Contrary to popular belief, the Declaration of Independence was not signed on July 4th, the day it was officially adopted by the Continental Congress.

On the evening of July 4, 1776, a manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence was taken to Philadelphia printer, John Dunlap. By the next morning, finished copies had been printed and delivered to Congress for distribution. The number printed is not known, though it must have been substantial; the broadsides were distributed by members of Congress throughout the Colonies. Post riders were sent out with copies of the Declaration, and General Washington, then in New York, had several brigades of the army drawn up at 6 p.m. on July 9 to hear it read. The Declaration was read from the balcony of the State House in Boston on July 18 but did not reach Georgia until mid-August. Twenty-five original copies of what is referred to as the "Dunlap Broadside" are still in existence.

By July 9 all thirteen colonies had signified their approval of the Declaration, and so on July 19 Congress was able to order that the Declaration be "fairly engrossed on parchment. . .and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Timothy Matlack is believed to be the person who printed this version of the Declaration. On August 2nd the document was ready, and the journal of the Continental Congress records that "The declaration of Independence being engrossed and compared at the table eas signed."

In time, 56 delegates would sign the “original” engrossed version (including several who had not been present on July 4th).

Following the signing, it is believed that the document accompanied the Continental Congress during the Revolution and remained with government records following the war. During the War of 1812, it was kept at a private residence in Leesburg, Virginia, and during World War II it was housed at Fort Knox. Today, the original document is kept in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

THE LEGACY OF THE DECLARATION

Before Americans were American, they were British. Before Americans governed themselves, they were governed by a distant British king and a British Parliament in which they had no vote. Before America was an independent state, it was a dependent colony. Before Americans expressed support for equality, their government and society were aristocratic and highly hierarchical. These transformations were complex, but the changes owe a great deal to the Declaration of Independence of 1776, what has been properly termed “America’s mission statement.”

AN AMERICAN PEOPLE

In its opening lines, the Declaration made a radical statement: America was “one People." On the eve of independence, however, the thirteen colonies had been separate provinces, and colonists' loyalties were to their individual colonies and the British Empire rather than to each other. In fact, only commercial and cultural ties with Britain served to unify the colonies. Yet the Declaration helped to transform South Carolinians, Virginians, New Yorkers and other colonists into Americans.

A NEW SYSTEM OF GOVERNANCE

The Declaration announced America's separation from one of the world's most powerful empires: Britain. Parliament's taxes imposed without American representation, along with King George III's failure to address or ease his subjects' grievances, made dissolving the "bands which have connected them" not just a choice, but an urgent necessity. As the Declaration made clear, the "long train of abuses and usurpations" and the tyranny exhibited "over these States" forced the colonists to "alter their former system of Government." In such circumstances, Jefferson explained that it was the people’s “right, it was their duty,” to throw off the repressive government. Under the new "system," Americans would govern themselves.

CLOSER TO EUROPE

America did not secede from the British Empire to be alone in the world. Instead, the Declaration proclaimed that an independent America had assumed a "separate and equal station" with the other "powers of the earth." With this statement, America sought to occupy an equal place with other modern European nations, including France, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and even Britain. America's independence signaled a fundamental change: once-dependent British colonies became independent states that could make war, create alliances with foreign nations, and engage freely in commerce.

EQUAL RIGHTS

The Declaration proclaimed a landmark principle—that "all men are created equal." Colonists had always seen themselves as equal to their British cousins and entitled to the same liberties. But when Parliament passed laws that violated colonists' "inalienable rights" and ruled the American colonies without the "consent of the governed," colonists concluded that as a colonial master Britain was the land of tyranny, not freedom. The Declaration sought to restore equal rights by rejecting Britain's oppression.

THE "SPIRIT OF ‘76"

The principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence promised to lead America—and other nations on the globe—into a new era of freedom. The revolution begun by Americans on July 4, 1776 would never end. It would inspire all peoples living under the burden of oppression and ignorance to open their eyes to the rights of mankind, to overturn the power of tyrants, and to declare the triumph of equality over inequality. Thomas Jefferson recognized as much, preparing a letter for the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration less than two weeks before his death, he expressed his belief that the Declaration