An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Levels of Reading Comprehension in Higher Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Cristina de-la-peña.

1 Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación, Universidad Internacional de la Rioja, Logroño, Spain

María Jesús Luque-Rojas

2 Department of Theory and History of Education and Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education, University of Malaga, Málaga, Spain

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Higher education aims for university students to produce knowledge from the critical reflection of scientific texts. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a deep mental representation of written information. The objective of this research was to determine through a systematic review and meta-analysis the proportion of university students who have an optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension. Systematic review of empirical studies has been limited from 2010 to March 2021 using the Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, and PsycINFO databases. Two reviewers performed data extraction independently. A random-effects model of proportions was used for the meta-analysis and heterogeneity was assessed with I 2 . To analyze the influence of moderating variables, meta-regression was used and two ways were used to study publication bias. Seven articles were identified with a total sample of the seven of 1,044. The proportion of students at the literal level was 56% (95% CI = 39–72%, I 2 = 96.3%), inferential level 33% (95% CI = 19–46%, I 2 = 95.2%), critical level 22% (95% CI = 9–35%, I 2 = 99.04%), and organizational level 22% (95% CI = 6–37%, I 2 = 99.67%). Comparing reading comprehension levels, there is a significant higher proportion of university students who have an optimal level of literal compared to the rest of the reading comprehension levels. The results have to be interpreted with caution but are a guide for future research.

Introduction

Reading comprehension allows the integration of knowledge that facilitates training processes and successful coping with academic and personal situations. In higher education, this reading comprehension has to provide students with autonomy to self-direct their academic-professional learning and provide critical thinking in favor of community service ( UNESCO, 2009 ). However, research in recent years ( Bharuthram, 2012 ; Afflerbach et al., 2015 ) indicates that a part of university students are not prepared to successfully deal with academic texts or they have reading difficulties ( Smagorinsky, 2001 ; Cox et al., 2014 ), which may limit academic training focused on written texts. This work aims to review the level of reading comprehension provided by studies carried out in different countries, considering the heterogeneity of existing educational models.

The level of reading comprehension refers to the type of mental representation that is made of the written text. The reader builds a mental model in which he can integrate explicit and implicit data from the text, experiences, and previous knowledge ( Kucer, 2016 ; van den Broek et al., 2016 ). Within the framework of the construction-integration model ( Kintsch and van Dijk, 1978 ; Kintsch, 1998 ), the most accepted model of reading comprehension, processing levels are differentiated, specifically: A superficial level that identifies or memorizes data forming the basis of the text and a deep level in which the text situation model is elaborated integrating previous experiences and knowledge. At these levels of processing, the cognitive strategies used, are different according to the domain-learning model ( Alexander, 2004 ) from basic coding to a transformation of the text. In the scientific literature, there are investigations ( Yussof et al., 2013 ; Ulum, 2016 ) that also identify levels of reading comprehension ranging from a literal level of identification of ideas to an inferential and critical level that require the elaboration of inferences and the data transformation.

Studies focused on higher education ( Barletta et al., 2005 ; Yáñez Botello, 2013 ) show that university students are at a literal or basic level of understanding, they often have difficulties in making inferences and recognizing the macrostructure of the written text, so they would not develop a model of a situation of the text. These scientific results are in the same direction as the research on reading comprehension in the mother tongue in the university population. Bharuthram (2012) indicates that university students do not access or develop effective strategies for reading comprehension, such as the capacity for abstraction and synthesis-analysis. Later, Livingston et al. (2015) find that first-year education students present limited reading strategies and difficulties in understanding written texts. Ntereke and Ramoroka (2017) found that only 12.4% of students perform well in a reading comprehension task, 34.3% presenting a low level of execution in the task.

Factors related to the level of understanding of written information are the mode of presentation of the text (printed vs. digital), the type of metacognitive strategies used (planning, making inferences, inhibition, monitoring, etc.), the type of text and difficulties (novel vs. a science passage), the mode of writing (text vs. multimodal), the type of reading comprehension task, and the diversity of the student. For example, several studies ( Tuncer and Bahadir, 2014 ; Trakhman et al., 2019 ; Kazazoglu, 2020 ) indicate that reading is more efficient with better performance in reading comprehension tests in printed texts compared to the same text in digital and according to Spencer (2006) college students prefer to read in print vs. digital texts. In reading the written text, metacognitive strategies are involved ( Amril et al., 2019 ) but studies ( Channa et al., 2018 ) seem to indicate that students do not use them for reading comprehension, specifically; Korotaeva (2012) finds that only 7% of students use them. Concerning the type of text and difficulties, for Wolfe and Woodwyk (2010) , expository texts benefit more from the construction of a situational model of the text than narrative texts, although Feng (2011) finds that expository texts are more difficult to read than narrative texts. Regarding the modality of the text, Mayer (2009) and Guo et al. (2020) indicate that multimodal texts that incorporate images into the text positively improve reading comprehension. In a study of Kobayashi (2002) using open questions, close, and multiple-choice shows that the type and format of the reading comprehension assessment test significantly influence student performance and that more structured tests help to better differentiate the good ones and the poor ones in reading comprehension. Finally, about student diversity, studies link reading comprehension with the interest and intrinsic motivation of university students ( Cartwright et al., 2019 ; Dewi et al., 2020 ), with gender ( Saracaloglu and Karasakaloglu, 2011 ), finding that women present a better level of reading comprehension than men and with knowledge related to reading ( Perfetti et al., 1987 ). In this research, it was controlled that all were printed and unimodal texts, that is, only text. This is essential because the cognitive processes involved in reading comprehension can vary with these factors ( Butcher and Kintsch, 2003 ; Xu et al., 2020 ).

The Present Study

Regardless of the educational context, in any university discipline, preparing essays or developing arguments are formative tasks that require a deep level of reading comprehension (inferences and transformation of information) that allows the elaboration of a situation model, and not having this level can lead to limited formative learning. Therefore, the objective of this research was to know the state of reading comprehension levels in higher education; specifically, the proportion of university students who perform optimally at each level of reading comprehension. It is important to note that there is not much information about the different levels in university students and that it is the only meta-analytic review that explores different levels of reading comprehension in this educational stage. This is a relevant issue because the university system requires that students produce knowledge from the critical reflection of scientific texts, preparing them for innovation, employability, and coexistence in society.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility criteria: inclusion and exclusion.

Empirical studies written in Spanish or English are selected that analyze the reading comprehension level in university students.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) book chapters or review books or publications; (b) articles in other languages; (c) studies of lower educational levels; (d) articles that do not identify the age of the sample; (e) second language studies; (f) students with learning difficulties or other disorders; (g) publications that do not indicate the level of reading comprehension; (h) studies that relate reading competence with other variables but do not report reading comprehension levels; (i) pre-post program application work; (j) studies with experimental and control groups; (k) articles comparing pre-university stages or adults; (l) publications that use multi-texts; (m) studies that use some type of technology (computer, hypertext, web, psychophysiological, online questionnaire, etc.); and (n) studies unrelated to the subject of interest.

Only those publications that meet the following criteria are included as: (a) be empirical research (article, thesis, final degree/master’s degree, or conference proceedings book); (b) university stage; (c) include data or some measure on the level of reading comprehension that allows calculating the effect size; (d) written in English or Spanish; (e) reading comprehension in the first language or mother tongue; and (f) the temporary period from January 2010 to March 2021.

Search Strategies

A three-step procedure is used to select the studies included in the meta-analysis. In the first step, a review of research and empirical articles in English and Spanish from January 2010 to March 2021. The search is carried out in online databases of languages in Spanish and English, such as Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, Medline, and PsycINFO, to review empirical productions that analyze the level of reading comprehension in university students. In the second step, the following terms (titles, abstracts, keywords, and full text) are used to select the articles: Reading comprehension and higher education, university students, in Spanish and English, combined with the Boolean operators AND and OR. In the last step, secondary sources, such as the Google search engine, Theseus, and references in publications, are explored.

The search reports 4,294 publications (articles, theses, and conference proceedings books) in the databases and eight records of secondary references, specifically, 1989 from WoS, 2001 from Scopus, 42 from Medline, and 262 of PsycINFO. Of the total (4,294), 1,568 are eliminated due to duplications, leaving 2,734 valid records. Next, titles and abstracts are reviewed and 2,659 are excluded because they do not meet the inclusion criteria. The sample of 75 publications is reduced to 40 articles, excluding 35 because the full text cannot be accessed (the authors were contacted but did not respond), the full text did not show specific statistical data, they used online questionnaires or computerized presentations of the text. Finally, seven articles in Spanish were selected for use in the meta-analysis of the reading comprehension level of university students. Data additional to those included in the articles were not requested from the selected authors.

The PRISMA-P guidelines ( Moher et al., 2015 ) are followed to perform the meta-analysis and the flow chart for the selection of publications relevant to the subject is exposed (Figure 1) .

Flow diagram for the selection of articles.

Encoding Procedure

This research complies with what is established in the manual of systematic reviews ( Higgins and Green, 2008 ) in which clear objectives, specific search terms, and eligibility criteria for previously defined works are established. Two independent coders, reaching a 100% agreement, carry out the study search process. Subsequently, the research is codified, for this, a coding protocol is used as a guide to help resolve the ambiguities between the coders; the proposals are reflected and discussed and discrepancies are resolved, reaching a degree of agreement between the two coders of 97%.

For all studies, the reference, country, research objective, sample size, age and gender, reading comprehension test, other tests, and reading comprehension results were coded in percentages. All this information was later systematized in Table 1 .

Results of the empirical studies included in the meta-analysis.

| S. No. | Reference | Country | Objective | Sample ( °/age/sex) | Comprehension Instrumentos | Other tests | Reading comprehension results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ecuador | Assess the effectiveness of didactic strategies to strengthen the level of reading comprehension | 30 Educación/unknown/unknown | text with 12SS questions | Literal: 40% Inferential: 40% Critical: 20% | ||

| 2. | México | Validate reading comprehension test | 570 Psychology/19.9 years/72% women 28% men | Instrument to measure reading comprehension of university students (ICLAU) | Literal: 41% Inferential: 33% Critical: 47% Appreciative: 72% Organization.: 75% Prueba general: 66% | ||

| 3. | México | Assess reading comprehension | 101 Education/unknown/unknown | text with questions | Literal: 52.86% Inferential: 52.92% Critical: 53.89% Organization: 66.46% Appreciative: 44.01% | ||

| 4. | Bolivia | Identify the relationship between reading comprehension and academic performance | 49 Psychology/18.5 years/87.8% women 12.2% men | Instrument to measure reading comprehension in university students (ICLAU) | Academic qualifications | Literal: 67.3% Inferential: 12.2% Organization: 4.1% Critical: 0% Appreciative: 0% | |

| 5. | Chile | Know the level of reading comprehension | 44 Kinesiology and Nutrition and Dietetics/unknown/unknown | Instrument to measure reading comprehension in university students (ICLAU) | Literal: 43.2% Inferential: 4.5% Critical: 0% Organization: 4.5% | ||

| 6. | Colombia | Characterize the cognitive processes involved in reading and their relationship with reading comprehension levels | 124 Psychology/16–30 years/unknown | Arenas Reading Comprehension Assessment Questionnaire (2007) | Literal: 56.4% Inferential: 43.5% Critical: 0% | ||

| 7. | Perú | Determine the level of reading comprehension | 126 from the 1°year University/43% men and 57% women/15–26 years | Reading comprehension test 10 fragments with 28 questions | Bibliographic datasheet | Literal: 86.7% Inferential: 45.4% Critical: 34.29% |

In relation to the type of reading comprehension level, it was coded based on the levels of the scientific literature as follows: 1 = literal; 2 = inferential; 3 = critical; and 4 = organizational.

Regarding the possible moderating variables, it was coded if the investigations used a standardized reading comprehension measure (value = 1) or non-standardized (value = 0). This research considers the standardized measures of reading comprehension as the non-standardized measures created by the researchers themselves in their studies or questionnaires by other authors. By the type of evaluation test, we encode between multiple-choice (value = 0) or multiple-choices plus open question (value = 1). By type of text, we encode between argumentative (value = 1) or unknown (value = 0). By the type of career, we encode social sciences (value = 1) or other careers (health sciences; value = 0). Moreover, by the type of publication, we encode between article (value = 1) or doctoral thesis (value = 0).

Effect Size and Statistical Analysis

This descriptive study with a sample k = 7 and a population of 1,044 university students used a continuous variable and the proportions were used as the effect size to analyze the proportion of students who had an optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension. As for the percentages of each level of reading comprehension of the sample, they were transformed into absolute frequencies. A random-effects model ( Borenstein et al., 2009 ) was used as the effect size. These random-effects models have a greater capacity to generalize the conclusions and allow estimating the effects of different sources of variation (moderating variables). The DerSimonian and Laird method ( Egger et al., 2001 ) was used, calculating raw proportion and for each proportion its standard error, value of p and 95% confidence interval (CI).

To examine sampling variability, Cochran’s Q test (to test the null hypothesis of homogeneity between studies) and I 2 (proportion of variability) were used. According to Higgins et al. (2003) , if I 2 reaches 25%, it is considered low, if it reaches 50% and if it exceeds 75% it is considered high. A meta-regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of the moderator variables (type of measure, type of evaluation test, type of text, type of career, and type of publication) in each level of reading comprehension of the sample studies. For each moderating variable, all the necessary statistics were calculated (estimate, standard error, CI, Q , and I 2 ).

To compare the effect sizes of each level (literal, inferential, critical, and organizational) of reading comprehension, the chi-square test for the proportion recommended by Campbell (2007) was used.

Finally, to analyze publication bias, this study uses two ways: Rosenthal’s fail-safe number and regression test. Rosenthal’s fail-safe number shows the number of missing studies with null effects that would make the previous correlations insignificant ( Borenstein et al., 2009 ). When the values are large there is no bias. In the regression test, when the regression is not significant, there is no bias.

The software used to classify and encode data and produce descriptive statistics was with Microsoft Excel and the Jamovi version 1.6 free software was used to perform the meta-analysis.

The results of the meta-analysis are presented in three parts: the general descriptive analysis of the included studies; the meta-analytic analysis with the effect size, heterogeneity, moderating variables, and comparison of effect sizes; and the study of publication bias.

Overview of Included Studies

The search carried out of the scientific literature related to the subject published from 2010 to March 2021 generated a small number of publications, because it was limited to the higher education stage and required clear statistical data on reading comprehension.

Table 1 presents all the publications reviewed in this meta-analysis with a total of students evaluated in the reviewed works that amounts to 1,044, with the smallest sample size of 30 ( Del Pino-Yépez et al., 2019 ) and the largest with 570 ( Guevara Benítez et al., 2014 ). Regarding gender, 72% women and 28% men were included. Most of the sample comes from university degrees in social sciences, such as psychology and education (71.42%) followed by health sciences (14.28%) engineering and a publication (14.28%) that does not indicate origin. These publications selected according to the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis come from more countries with a variety of educational systems, but all from South America. Specifically, the countries that have more studies are Mexico (28.57%) and Colombia, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador with 14.28% each, respectively. The years in which they were published are 2.57% in 2018 and 2016 and 14.28% in 2019, 2014, and 2013.

A total of 57% of the studies analyze four levels of reading comprehension (literal, inferential, critical, and organizational) and 43% investigate three levels of reading comprehension (literal, inferential, and critical). Based on the moderating variables, 57% of the studies use standardized reading comprehension measures and 43% non-standardized measures. According to the evaluation test used, 29% use multiple-choice questions and 71% combine multiple-choice questions plus open questions. 43% use an argumentative text and 57% other types of texts (not indicated in studies). By type of career, 71% are students of social sciences and 29% of other different careers, such as engineering or health sciences. In addition, 71% are articles and 29% with research works (thesis and degree works).

Table 2 shows the reading comprehension assessment instruments used by the authors of the empirical research integrated into the meta-analysis.

Reading comprehension assessment tests used in higher education.

| Studies | Evaluation tests | Description | Validation/Baremation |

|---|---|---|---|

| text with 12 questions | Text “Narcissism” with 12 questions: 4 literal, 4 inferential, and 4 critical. 40 min | Validation: no Reliability: no Baremation: no | |

| ; ; | Instrument to measure reading comprehension in university students (ICLAU) | 965-word text on “Evolution and its history.” Then 7 questions are answered as: 2 literal, 2 inferential, 1 organizational, 1 critical, and 1 appreciative. 1 h | Inter-judge validation Reliability: no Baremation: no |

| text with questions | 596-word text on “Ausubel’s theory.” Then literal, inferential, organizational, appreciative, and critical level questions | Validation: no Reliability: no Baremation: no | |

| Arenas Reading Comprehension Assessment Questionnaire (2007) | Texts 4: 2 literary and 2 scientific with 32 questions each and four answer options | Inter-judge validation Reliability: no Baremation: no | |

| Reading comprehension test by Violeta Tapia Mendieta and Maritza Silva Alejos | 35 min | Validation: empirical validity: 0.58 Reliability: test-retest: 0.53 Baremation: yes |

Meta-Analytic Analysis of the Level of Reading Comprehension

The literal level presents a mean proportion effect size of 56% (95% CI = 39–72%; Figure 2 ). The variability between the different samples of the literal level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 162.066, p < 0.001; I 2 = 96.3%). No moderating variable used in this research had a significant contribution to heterogeneity: type of measurement ( p = 0.520), type of test ( p = 0.114), type of text ( p = 0.520), type of career ( p = 0.235), and type of publication ( p = 0.585). The high variability is explained by other factors not considered in this work, such as the characteristics of the students (cognitive abilities) or other issues.

Forest plot of literal level.

The inferential level presents a mean proportion effect size of 33% (95% CI = 19–46%; Figure 3 ). The variability between the different samples of the inferential level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 125.123, p < 0.001; I 2 = 95.2%). The type of measure ( p = 0.011) and the type of text ( p = 0.011) had a significant contribution to heterogeneity. The rest of the variables had no significance: type of test ( p = 0.214), type of career ( p = 0.449), and type of publication ( p = 0.218). According to the type of measure, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential administering a standardized test is 28.7% less than when a non-standardized test is administered. The type of measure reduces variability by 2.57% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the inferential level. According to the type of text, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential using an argumentative text is 28.7% less than when using another type of text. The type of text reduces the variability by 2.57% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the inferential level.

Forest plot of inferential level.

The critical level has a mean effect size of the proportion of 22% (95% CI = 9–35%; Figure 4 ). The variability between the different samples of the critical level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 627.044, p < 0.001; I 2 = 99.04%). No moderating variable used in this research had a significant contribution to heterogeneity: type of measurement ( p = 0.575), type of test ( p = 0.691), type of text ( p = 0.575), type of career ( p = 0.699), and type of publication ( p = 0.293). The high variability is explained by other factors not considered in this work, such as the characteristics of the students (cognitive abilities).

Forest plot of critical level.

The organizational level presents a mean effect size of the proportion of 22% (95% CI = 6–37%; Figure 5 ). The variability between the different samples of the organizational level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 1799.366, p < 0.001; I 2 = 99.67%). The type of test made a significant contribution to heterogeneity ( p = 0.289). The other moderating variables were not significant in this research: type of measurement ( p = 0.289), type of text ( p = 0.289), type of career ( p = 0.361), and type of publication ( p = 0.371). Depending on the type of test, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in organizational with multiple-choices tests plus open questions is 37% higher than while using only multiple-choice tests. The type of text reduces the variability by 0.27% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the organizational level.

Forest plot of organizational level.

Table 3 shows the difference between the estimated effect sizes and the significance. There is a larger proportion of students having an optimal level of reading comprehension at the literal level compared to the inferential, critical, and organizational level; an optimal level of reading comprehension at the inferential level vs. the critical and organizational level.

Results of effect size comparison.

| Difference | CI | Value of | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal-Inferential | 110.963 | 22.9% | 18.7035–26.9796% | < 0.0001 |

| Literal-Critical | 248.061 | 33.6% | 25.5998–37.4372% | < 0.0001 |

| Literal-Organizational | 264.320 | 34.6% | 30.6246–38.4088% | < 0.0001 |

| Inferential-Critical | 30.063 | 10.7% | 6.865–14.4727% | < 0.0001 |

| Inferential-Organizational | 36.364 | 11.7% | 7.9125–15.4438% | < 0.0001 |

| Critical-Organizational | 0.309 | 1% | −2.5251–4.5224% | = 0.5782 |

Analysis of Publication Bias

This research uses two ways to verify the existence of bias independently of the sample size. Table 4 shows the results and there is no publication bias at any level of reading comprehension.

Publication bias results.

| Fail-safe N | Value of | Regression test | Value of | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal | 3115.000 | <0.001 | −0.571 | 0.568 |

| Inferential | 1145.000 | <0.001 | 0.687 | 0.492 |

| Critical | 783.000 | <0.001 | 1.862 | 0.063 |

| Organizational | 1350.000 | <0.001 | 1.948 | 0.051 |

This research used a systematic literature search and meta-analysis to provide estimates of the number of cases of university students who have an optimal level in the different levels of reading comprehension. All the information available on the subject at the international level was analyzed using international databases in English and Spanish, but the potentially relevant publications were limited. Only seven Spanish language studies were identified internationally. In these seven studies, the optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension varied, finding heterogeneity associated with the very high estimates, which indicates that the summary estimates have to be interpreted with caution and in the context of the sample and the variables used in this meta-analysis.

In this research, the effects of the type of measure, type of test, type of text, type of career, and type of publication have been analyzed. Due to the limited information in the publications, it was not possible to assess the effect of any more moderating variables.

We found that some factors significantly influence heterogeneity according to the level of reading comprehension considered. The type of measure influenced the optimal performance of students in the inferential level of reading comprehension; specifically, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential worsens if the test is standardized. Several studies ( Pike, 1996 ; Koretz, 2002 ) identify differences between standardized and non-standardized measures in reading comprehension and a favor of non-standardized measures developed by the researchers ( Pyle et al., 2017 ). The ability to generate inferences of each individual may difficult to standardize because each person differently identifies the relationship between the parts of the text and integrates it with their previous knowledge ( Oakhill, 1982 ; Cain et al., 2004 ). This mental representation of the meaning of the text is necessary to create a model of the situation and a deep understanding ( McNamara and Magliano, 2009 ; van den Broek and Espin, 2012 ).

The type of test was significant for the organizational level of reading comprehension. The proportion of students who have an optimal level in organizational improves if the reading comprehension assessment test is multiple-choice plus open questions. The organizational level requires the reordering of written information through analysis and synthesis processes ( Guevara Benítez et al., 2014 ); therefore, it constitutes a production task that is better reflected in open questions than in reproduction questions as multiple choice ( Dinsmore and Alexander, 2015 ). McNamara and Kintsch (1996) identify that open tasks require an effort to make inferences related to previous knowledge and multidisciplinary knowledge. Important is to indicate that different evaluation test formats can measure different aspects of reading comprehension ( Zheng et al., 2007 ).

The type of text significantly influenced the inferential level of reading comprehension. The proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential decreases with an argumentative text. The expectations created before an argumentative text made it difficult to generate inferences and, therefore, the construction of the meaning of the text. This result is in the opposite direction to the study by Diakidoy et al. (2011) who find that the refutation text, such as the argumentative one, facilitates the elaboration of inferences compared to other types of texts. It is possible that the argumentative text, given its dialogical nature of arguments and counterarguments, with a subject unknown by the students, has determined the decrease of inferences based on their scarce previous knowledge of the subject, needing help to elaborate the structure of the text read ( Reznitskaya et al., 2007 ). It should be pointed out that in meta-analysis studies, 43% use argumentative texts. Knowing the type of the text is relevant for generating inferences, for instance, according to Baretta et al. (2009) the different types of text are processed differently in the brain generating more or fewer inferences; specifically, using the N400 component, they find that expository texts generate more inferences from the text read.

For the type of career and the type of publication, no significance was found at any level of reading comprehension in this sample. This seems to indicate that university students have the same level of performance in tasks of literal, critical inferential, and organizational understanding regardless of whether they are studying social sciences, health sciences, or engineering. Nor does the type of publication affect the state of the different levels of reading comprehension in higher education.

The remaining high heterogeneity at all levels of reading comprehension was not captured in this review, indicating that there are other factors, such as student characteristics, gender, or other issues, that are moderating and explaining the variability at the literal, inferential, critical, and organizational reading comprehension in university students.

To the comparison between the different levels of reading comprehension, the literal level has a significantly higher proportion of students with an optimal level than the inferential, critical, and organizational levels. The inferential level has a significantly higher proportion of students with an optimal level than the critical and organizational levels. This corresponds with data from other investigations ( Márquez et al., 2016 ; Del Pino-Yépez et al., 2019 ) that indicate that the literal level is where university students execute with more successes, being more difficult and with less success at the inferential, organizational, and critical levels. This indicates that university students of this sample do not generate a coherent situation model that provides them with a global mental representation of the read text according to the model of Kintsch (1998) , but rather they make a literal analysis of the explicit content of the read text. This level of understanding can lead to less desirable results in educational terms ( Dinsmore and Alexander, 2015 ).

The educational implications of this meta-analysis in this sample are aimed at making universities aware of the state of reading comprehension levels possessed by university students and designing strategies (courses and workshops) to optimize it by improving the training and employability of students. Some proposals can be directed to the use of reflection tasks, integration of information, graphic organizers, evaluation, interpretation, nor the use of paraphrasing ( Rahmani, 2011 ). Some studies ( Hong-Nam and Leavell, 2011 ; Parr and Woloshyn, 2013 ) demonstrate the effectiveness of instructional courses in improving performance in reading comprehension and metacognitive strategies. In addition, it is necessary to design reading comprehension assessment tests in higher education that are balanced, validated, and reliable, allowing to have data for the different levels of reading comprehension.

Limitations and Conclusion

This meta-analysis can be used as a starting point to report on reading comprehension levels in higher education, but the results should be interpreted with caution and in the context of the study sample and variables. Publications without sufficient data and inaccessible articles, with a sample of seven studies, may have limited the international perspective. The interest in studying reading comprehension in the mother tongue, using only unimodal texts, without the influence of technology and with English and Spanish has also limited the review. The limited amount of data in the studies has limited meta-regression.

This review is a guide to direct future research, broadening the study focus on the level of reading comprehension using digital technology, experimental designs, second languages, and investigations that relate reading comprehension with other factors (gender, cognitive abilities, etc.) that can explain the heterogeneity in the different levels of reading comprehension. The possibility of developing a comprehensive reading comprehension assessment test in higher education could also be explored.

This review contributes to the scientific literature in several ways. In the first place, this meta-analytic review is the only one that analyzes the proportion of university students who have an optimal performance in the different levels of reading comprehension. This review is made with international publications and this topic is mostly investigated in Latin America. Second, optimal performance can be improved at all levels of reading comprehension, fundamentally inferential, critical, and organizational. The literal level is significantly the level of reading comprehension with the highest proportion of optimal performance in university students. Third, the students in this sample have optimal performance at the inferential level when they are non-argumentative texts and non-standardized measures, and, in the analyzed works, there is optimal performance at the organizational level when multiple-choice questions plus open questions are used.

The current research is linked to the research project “Study of reading comprehension in higher education” of Asociación Educar para el Desarrollo Humano from Argentina.

Data Availability Statement

Author contributions.

Cd-l-P had the idea for the article and analyzed the data. ML-R searched the data. Cd-l-P and ML-R selected the data and contributed to the valuable comments and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared affiliation though no other collaboration with one of the authors ML-R at the time of the review.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding. This paper was funded by the Universidad Internacional de la Rioja and Universidad de Málaga.

- Afflerbach P., Cho B.-Y., Kim J.-Y. (2015). Conceptualizing and assessing higher-order thinking in reading . Theory Pract. 54 , 203–212. 10.1080/00405841.2015.1044367 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexander P. A. (2004). “ A model of domain learning: reinterpreting expertise as a multidimensional, multistage process ,” in Motivation, Emotion, and Cognition: Integrative Perspectives on Intellectual Functioning and Development. eds. Dai D. Y., Sternberg R. J. (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; ), 273–298. [ Google Scholar ]

- Amril A., Hasanuddin W. S., Atmazaki (2019). The contributions of reading strategies and reading frequencies toward students’ reading comprehension skill in higher education . Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. (IJEAT) 8 , 593–595. 10.35940/ijeat.F1105.0986S319 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baretta L., Braga Tomitch L. M., MacNair N., Kwan Lim V., Waldie K. E. (2009). Inference making while reading narrative and expository texts: an ERP study . Psychol. Neurosci. 2 , 137–145. 10.3922/j.psns.2009.2.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barletta M., Bovea V., Delgado P., Del Villar L., Lozano A., May O., et al.. (2005). Comprensión y Competencias Lectoras en Estudiantes Universitarios. Barranquilla: Uninorte. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bharuthram S. (2012). Making a case for the teaching of reading across the curriculum in higher education . S. Afr. J. Educ. 32 , 205–214. 10.15700/saje.v32n2a557 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P. T., Rothstein H. R. (2009). Introduction to Meta-Analysis. United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 45–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butcher K. R., Kintsch W. (2003). “ Text comprehension and discourse processing ,” in Handbook of Psychology: Experimental Psychology. 2nd Edn . Vol . 4 . eds. Healy A. F., Proctor R. W., Weiner I. B. (New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 575–595. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cain K., Oakhill J., Bryant P. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills . J. Educ. Psychol. 96 , 31–42. 10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell I. (2007). Chi-squared and Fisher-Irwin tests of two-by-two tables with small sample recommendations . Stat. Med. 26 , 3661–3675. 10.1002/sim.2832, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cartwright K. B., Lee S. A., Barber A. T., DeWyngaert L. U., Lane A. B., Singleton T. (2019). Contributions of executive function and cognitive intrinsic motivation to university students’ reading comprehension . Read. Res. Q. 55 , 345–369. 10.1002/rrq.273 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Channa M. A., Abassi A. M., John S., Sahito J. K. M. (2018). Reading comprehension and metacognitive strategies in first-year engineering university students in Pakistan . Int. J. Engl. Ling. 8 , 78–87. 10.5539/ijel.v8n6p78 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cox S. R., Friesner D. L., Khayum M. (2014). Do Reading skills courses help underprepared readers achieve academic success in college? J. College Reading and Learn. 33 , 170–196. 10.1080/10790195.2003.10850147 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Del Pino-Yépez G. M., Saltos-Rodríguez L. J., Moreira-Aguayo P. Y. (2019). Estrategias didácticas para el afianzamiento de la comprensión lectora en estudiantes universitarios . Revista científica Dominio de las Ciencias 5 , 171–187. 10.23857/dc.v5i1.1038 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewi R. S., Fahrurrozi, Hasanah U., Wahyudi A. (2020). Reading interest and Reading comprehension: a correlational study in Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta . Talent Dev. Excell. 12 , 241–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diakidoy I. N., Mouskounti T., Ioannides C. (2011). Comprehension and learning from refutation and expository texts . Read. Res. Q. 46 , 22–38. 10.1598/RRQ.46.1.2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dinsmore D. J., Alexander P. A. (2015). A multidimensional investigation of deep-level and surface-level processing . J. Exp. Educ. 84 , 213–244. 10.1080/00220973.2014.979126 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger M., Smith D., Altmand D. G. (2001). Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. London: BMJ Publishing Group. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feng L. (2011). A short analysis of the text variables affecting reading and testing reading . Stud. Lit. Lang. 2 , 44–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Figueroa Romero R. L., Castañeda Sánchez W., Tamay Carranza I. A. (2016). Nivel de comprensión lectora en los estudiantes del primer ciclo de la Universidad San Pedro, filial Caraz, 2016. (Trabajo de investigación, Universidad San Pedro). Repositorio Institucional USP. Available at: http://repositorio.usanpedro.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/USANPEDRO/305/PI1640418.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (Accessed February 15, 2021).

- Guevara Benítez Y., Guerra García J., Delgado Sánchez U., Flores Rubí C. (2014). Evaluación de distintos niveles de comprensión lectora en estudiantes mexicanos de Psicología . Acta Colombiana de Psicología 17 , 113–121. 10.14718/ACP.2014.17.2.12 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo D., Zhang S., Wright K. L., McTigue E. M. (2020). Do you get the picture? A meta-analysis of the effect of graphics on reading comprehension . AERA Open 6 , 1–20. 10.1177/2332858420901696 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins J. P., Green S. (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses . BMJ 327 , 327–557. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hong-Nam K., Leavell A. G. (2011). Reading strategy instruction, metacognitive awareness, and self-perception of striving college developmental readers . J. College Literacy Learn. 37 , 3–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kazazoglu S. (2020). Is printed text the best choice? A mixed-method case study on reading comprehension . J. Lang. Linguistic Stud. 16 , 458–473. 10.17263/jlls.712879 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kintsch W. (1998). Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kintsch W., van Dijk T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production . Psychol. Rev. 85 , 363–394. 10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kobayashi M. (2002). Method effects on reading comprehension test performance: test organization and response format . Lang. Test. 19 , 193–220. 10.1191/0265532202lt227oa [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Koretz D. (2002). Limitations in the use of achievement tests as measures of educators’ productivity . J. Hum. Resour. 37 , 752–777. 10.2307/3069616 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Korotaeva I. V. (2012). Metacognitive strategies in reading comprehension of education majors . Procedural-Social and Behav. Sci. 69 , 1895–1900. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.143 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kucer S. B. (2016). Accuracy, miscues, and the comprehension of complex literary and scientific texts . Read. Psychol. 37 , 1076–1095. 10.1080/02702711.2016.1159632 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Livingston C., Klopper B., Cox S., Uys C. (2015). The impact of an academic reading program in the bachelor of education (intermediate and senior phase) degree . Read. Writ. 6 , 1–11. 10.4102/rw.v6i1.66 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Márquez H., Díaz C., Muñoz R., Fuentes R. (2016). Evaluación de los niveles de comprensión lectora en estudiantes universitarios pertenecientes a las carreras de Kinesiología y Nutrición y Dietética de la Universidad Andrés Bello, Concepción . Revista de Educación en Ciencias de la Salud 13 , 154–160. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mayer R. E. (ed.) (2009). “ Modality principle ,” in Multimedia Learning. United States: Cambridge University Press, 200–2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- McNamara D. S., Kintsch W. (1996). Learning from texts: effects of prior knowledge and text coherence . Discourse Process 22 , 247–288. 10.1080/01638539609544975 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McNamara D. S., Magliano J. (2009). “ Toward a comprehensive model of comprehension ,” in The psychology of learning and motivation. ed. Ross E. B. (New York: Elsevier; ), 297–384. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al.. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement . Syst. Rev. 4 :1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ntereke B. B., Ramoroka B. T. (2017). Reading competency of first-year undergraduate students at the University of Botswana: a case study . Read. Writ. 8 :a123. 10.4102/rw.v8i1.123 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oakhill J. (1982). Constructive processes in skilled and less skilled comprehenders’ memory for sentences . Br. J. Psychol. 73 , 13–20. 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1982.tb01785.x, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parr C., Woloshyn V. (2013). Reading comprehension strategy instruction in a first-year course: an instructor’s self-study . Can. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 4 :3. 10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2013.2.3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perfetti C. A., Beck I., Bell L. C., Hughes C. (1987). Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal: a longitudinal study of first-grade children . Merrill-Palmer Q. 33 , 283–319. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pike G. R. (1996). Limitations of using students’ self-reports of academic development as proxies for traditional achievement measures . Res. High. Educ. 37 , 89–114. 10.1007/BF01680043 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pyle N., Vasquez A. C., Lignugaris B., Gillam S. L., Reutzel D. R., Olszewski A., et al.. (2017). Effects of expository text structure interventions on comprehension: a meta-analysis . Read. Res. Q. 52 , 469–501. 10.1002/rrq.179 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rahmani M. (2011). Effects of note-taking training on reading comprehension and recall . Reading Matrix: An Int. Online J. 11 , 116–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reznitskaya A., Anderson R., Kuo L. J. (2007). Teaching and learning argumentation . Elem. Sch. J. 107 , 449–472. 10.1086/518623 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sáez Sánchez B. K. (2018). La comprensión lectora en jóvenes universitarios de una escuela formadora de docentes . Revista Electrónica Científica de Investigación Educativa 4 , 609–618. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanabria Mantilla T. R. (2018). Relación entre comprensión lectora y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de primer año de Psicología de la Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. (Trabajo de grado, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana). Repositorio Institucional UPB. Available at: https://repository.upb.edu.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.11912/5443/digital_36863.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (Accessed February 15, 2021).

- Saracaloglu A. S., Karasakaloglu N. (2011). An investigation of prospective teachers’ reading comprehension levels and study and learning strategies related to some variables . Egit. ve Bilim 36 , 98–115. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smagorinsky P. (2001). If meaning is constructed, what is it made from? Toward a cultural theory of reading . Rev. Educ. Res. 71 , 133–169. 10.3102/00346543071001133 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spencer C. (2006). Research on learners’ preferences for reading from a printed text or a computer screen . J. Dist. Educ. 21 , 33–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Trakhman L. M. S., Alexander P., Berkowitz L. E. (2019). Effects of processing time on comprehension and calibration in print and digital mediums . J. Exp. Educ. 87 , 101–115. 10.1080/00220973.2017.1411877 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tuncer M., Bhadir F. (2014). Effect of screen reading and reading from printed out material on student success and permanency in introduction to computer lesson . Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 13 , 41–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ulum O. G. (2016). A descriptive content analysis of the extent of Bloom’s taxonomy in the reading comprehension questions of the course book Q: skills for success 4 reading and writing . Qual. Rep. 21 , 1674–1683. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNESCO (2009). “Conferencia mundial sobre la Educación Superior – 2009.” La nueva dinámica de la educación superior y la investigación para el cambio social y el desarrollo; July 5-8, 2009; Paris.

- van den Broek P., Espin C. A. (2012). Connecting cognitive theory and assessment: measuring individual differences in reading comprehension . Sch. Psychol. Rev. 43 , 315–325. 10.1080/02796015.2012.12087512 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van den Broek P., Mouw J. M., Kraal A. (2016). “ Individual differences in reading comprehension ,” in Handbook of Individual Differences in Reading: Reader, Text, and Context. ed. Afflerbach E. P. (New York: Routledge; ), 138–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolfe M. B. W., Woodwyk J. M. (2010). Processing and memory of information presented in narrative or expository texts . Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 80 , 341–362. 10.1348/000709910X485700, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu Y., Wong R., He S., Veldre A., Andrews S. (2020). Is it smart to read on your phone? The impact of reading format and culture on the continued influence of misinformation . Mem. Cogn. 48 , 1112–1127. 10.3758/s13421-020-01046-0, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yáñez Botello C. R. (2013). Caracterización de los procesos cognoscitivos y competencias involucrados en los niveles de comprensión lectora en Estudiantes Universitarios . Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología 13 , 75–90. 10.18270/chps.v13i2.1350 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yussof Y. M., Jamian A. R., Hamzah Z. A. Z., Roslan A. (2013). Students’ reading comprehension performance with emotional . Int. J. Edu. Literacy Stud. 1 , 82–88. 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.1n.1p.82 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zheng Y., Cheng L., Klinger D. A. (2007). Do test format in reading comprehension affect second-language students’ test performance differently? TESL Can. J. 25 , 65–78. 10.18806/tesl.v25i1.108 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Proficiency Level of the Reading Comprehension in the Academic Performance of the Grade 11 students in the

This study was conducted to determine The Proficiency Level of the Reading Comprehension in the Academic Performance of the Grade 11 students in the Sisters of Mary School Girlstown Inc. SY. 2018 - 2019. There 220 respondents were randomly selected out of 489 through the use of stratified random sampling using the class section as the strata. For data collection, reading comprehension passages and academic performance surveys were used. To obtain the needed data the respondents answered 19 reading comprehension test. The study of the findings confirmed that there is no significant correlation between reading comprehension and academic performance.

Related Papers

nichole S E R E N I O serad

CHAPTER 1_2_3

John Roy Baran

john fred fulgencio

mark F U C K you

Sisters of Mary School - Boystown, Inc.

ferlez bagaan

Self-esteem and academic achievement.

Janelle Tesado

PRII DUH...HUMANA NA JUD

zander bestudio

Computer literacy is the level of knowledge and great skill regarding effective use of computer and technologies for individuals' aims. However, the use purposes of computer could change from person to person. Therefore, there is not an explicit standard regarding the computer literacy levels. Yet, there is a common view for basic computer literacy levels. Although, there conducted studies concerning computer use in many fields, very limited number of studies related to computer literacy levels could be reached. Starting from this emphasis, this study aimed to identify the computer literacy levels of the individuals graduated from the grade 9 student in the junior high school in the sisters of mary school-girlstown Inc. 631 students from various 27 batch participated in the study. According to the results of analyses conducted, their basic computer literacy levels were founded to below.

Joel Meniado

Marry Macasaet

Metacognitive reading strategies and reading motivation play a significant role in enhancing reading comprehension. In an attempt to prove the foregoing claim in a context where there is no strong culture for reading, this study tries to find out if there is indeed a relationship between and among metacognitive reading strategies, reading motivation, and reading comprehension performance. Prior to finding out relationships, the study tried to ascertain the level of awareness and use of metacognitive reading strategies of the respondents when they read English academic texts, their level of motivation and reading interests, and their overall reading performance. Using descriptive survey and descriptive correlational methods with 60 randomly selected Saudi college-level EFL students in an all-male government-owned industrial college in Saudi Arabia, the study found out that the respondents moderately use the different metacognitive reading strategies when reading academic texts. Of the three categories of metacognitive reading strategies, the Problem-Solving Strategies (PROB) is the most frequently used. It was also revealed that the respondents have high motivation to read. They particularly prefer to read humor/comic books. On the level of reading comprehension performance, the respondents performed below average. Using t-test, the study reveals that there is no correlation between metacognitive reading strategies and reading comprehension. There is also no correlation between reading interest/motivation and reading comprehension. However, there is positive correlation between reading strategies and reading motivation. The findings of this study interestingly contradict previous findings of most studies, thus invite more thorough investigation along the same line of inquiry.

Christopher Espiritu

Karen Wixson

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

amado cadiong

Axcell Delis Belleza (Naval State University)

Axcell Belleza

Naomie B . Daguinotas

Manit Bacate

Russell Gersten

The Elementary School Journal

Deena Abdl Hameed Saleh AlJa

Elizabeth Dutro

Cebu Normal University

MARIA GRIZEL RAGANDANG

Laverne Ladion

Daboy Ignacio

Christopher Contreras

Asian EFL Journal

Romualdo Mabuan

jeverlyn gedo cruz

Maria Cequena , Joeseph Velasquez

Becky H. Huang

Barbara Acosta

Ahmad Molavi

Elnaz Sarabchian

Rezei Tadako

Nguyen Thi Kim Phuong

Charles Hausman , Annela Teemant

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research

Research and Statistics Center

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Method

Amin Karimnia

Elizabeth R. Hinde

National Center for …

jovelyn sinlao

National Center For Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance

Rosemarie Sumalinog Gonzales

GATR Journals

Hugh Fox III

Rainulfo Pagaran

Journal of …

Maeghan Hennessey

Journal of deaf studies and deaf education

Diane Nielsen

Eric Camburn

Karesha Faith Cardente

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Development of the reading comprehension strategies questionnaire (rcsq) for late elementary school students.

- 1 Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 2 Department of Data-analysis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

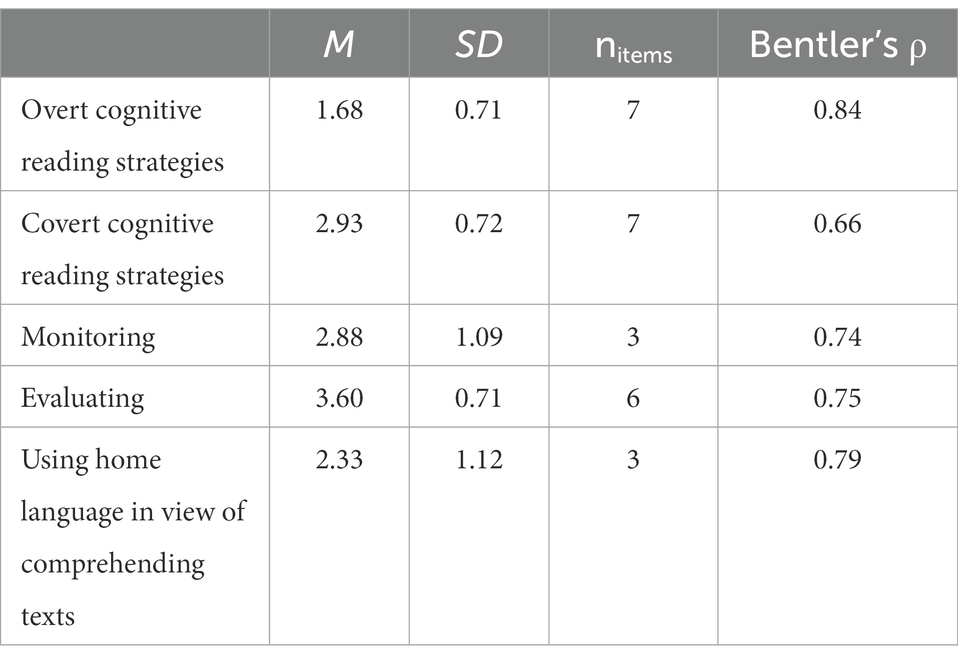

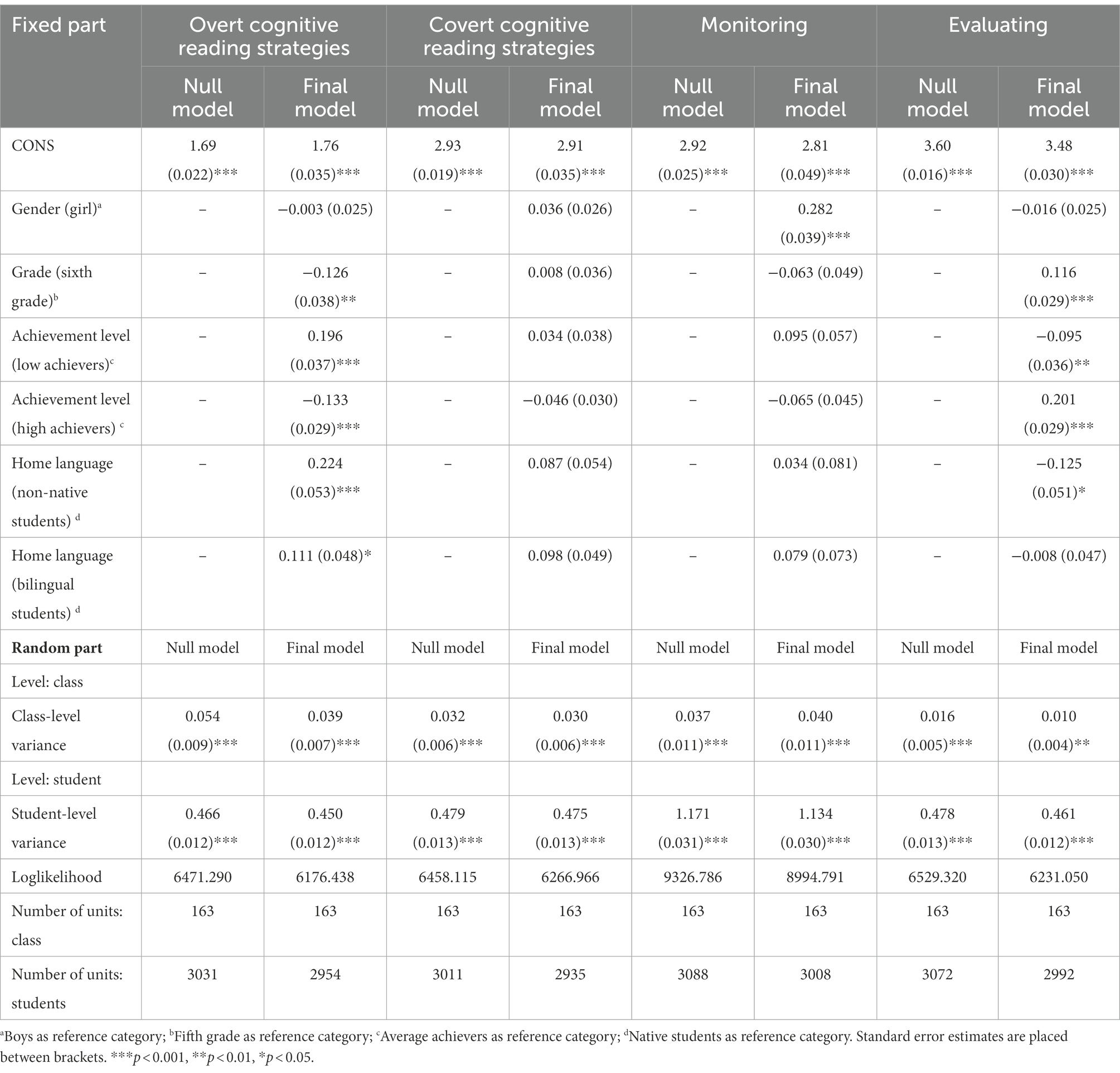

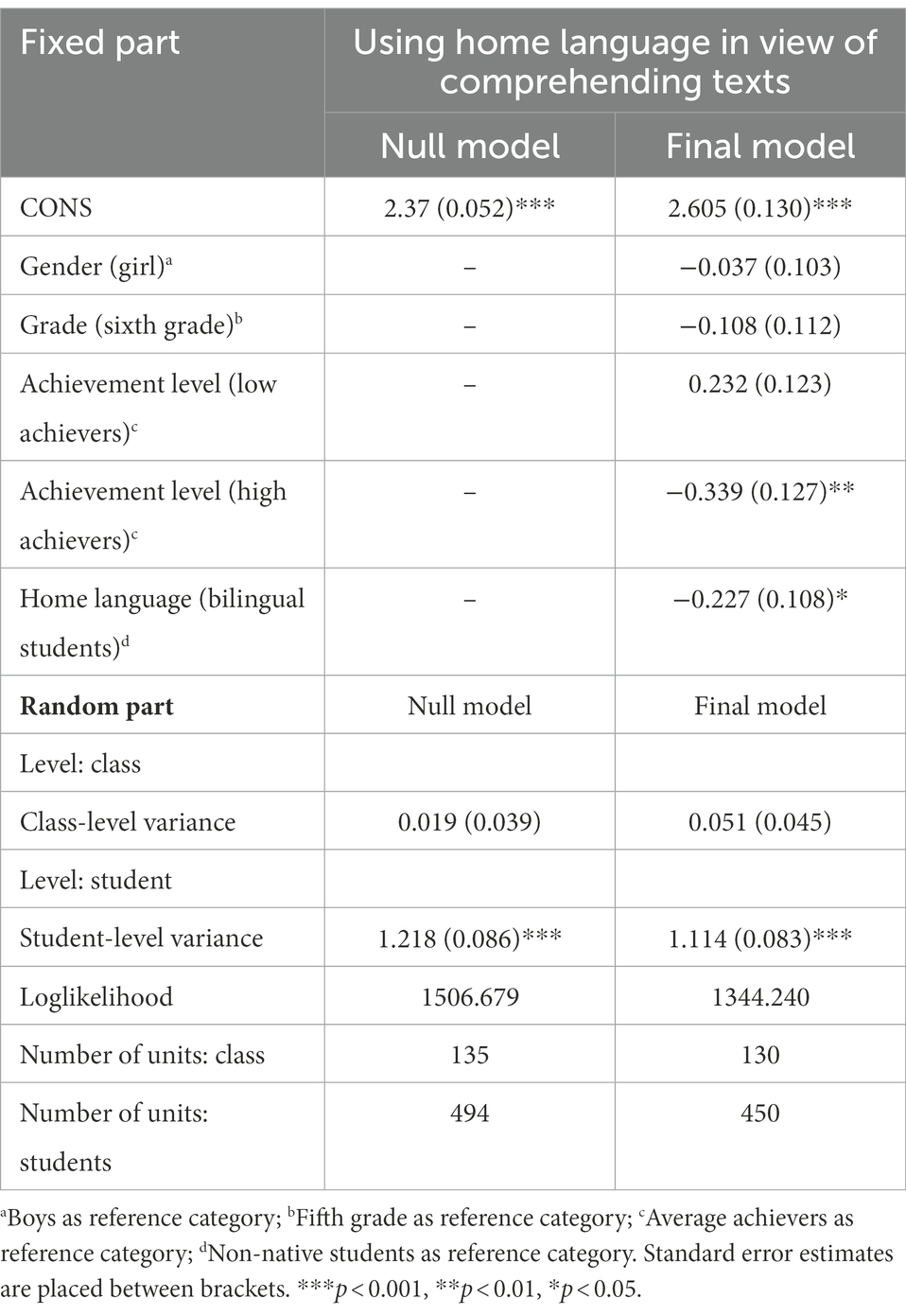

Late elementary education constitutes a critical period in the development of reading comprehension strategies, a key competence in today’s society. However, to date, appropriate measurements to map late elementary students’ reading strategies are lacking. In this respect, the present article first describes the development and validation of the 26-item reading comprehension strategies questionnaire (RCSQ). To this aim, exploratory (sample 1: n = 1585 students) and confirmatory (sample 2: n = 1585 students) factor analyses were conducted. These analyses resulted in the RCSQ, consisting of five subscales: (1) overt cognitive reading strategies, (2) covert cognitive reading strategies, (3) monitoring, and (4) evaluating. For non-native and bilingual students, a fifth subscale ‘using home language in view of comprehending texts’ emerged. Second, multilevel analyses were performed to explore individual differences in late elementary students’ reading comprehension strategy use. Implications for practice and future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Reading comprehension is a key competence for students’ success in school (e.g., academic achievement) as well as in life (e.g., job success). Moreover, poor reading comprehension is negatively correlated with students’ learning performance, problem solving skills, and their future school and work career ( OECD, 2018 ; Nanda and Azmy, 2020 ). Reading comprehension is defined as a complex and multifaceted process of creating meaning from texts ( van Dijk and Kintsch, 1983 ; Castles et al., 2018 ). Notwithstanding the acknowledged importance of reading comprehension, many children struggle with it in late elementary education (i.e., fifth-and sixth-graders), especially when it comes to understand expository texts ( Rasinski, 2017 ). According to both national and international studies, Flemish students are not performing well in reading comprehension ( Tielemans et al., 2017 ; Support Center for Test Development and Polls [Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen], 2018 ). More particularly, the results of a study on a representative sample of Flemish sixth-graders showed that 16% of the students failed to achieve basic reading comprehension standards ( Support Center for Test Development and Polls [Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen], 2018 ). Further, the study of Dockx et al. (2019) indicated that the fourth-grade results of high performing countries are only achieved by sixth-grade Flemish students. This is alarming, since poor reading comprehension can negatively influence access to higher education and fruitful education ( Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Moreover, late elementary education is a critical period to develop appropriate expository text comprehension skills ( Keresteš et al., 2019 ). Reading comprehension strategies play an essential role in effective comprehension of expository texts ( Follmer and Sperling, 2018 ). Unfortunately, to date only few studies addressed the challenge of mapping students’ reading strategy repertoire precisely in this critical period. This might be due to the lack of reliable and valid measurement instruments attuned to this age group. Therefore, the present study aimed to fill this gap by developing an age-appropriate expository reading comprehension strategies questionnaire. Additionally, individual differences in Flemish late elementary students’ actual strategy use (i.e., according to their gender, grade, achievement level, and home language) are examined by means of this questionnaire.

2. Reading comprehension strategy use

2.1. theoretical and empirical background.

Reading comprehension strategies have already been defined in many ways. However, in general, the following aspects are unanimously stressed: (1) the active role of proficient readers ( Garner, 1987 ; Winograd and Hare, 1988 ), (2) the relevance of deliberate and planful activities during reading ( Garner, 1987 ; Afflerbach et al., 2008 ), and (3) the aim to improve text comprehension ( Graesser, 2007 ; Afflerbach et al., 2008 ). Essentially, reading strategies are consequently described as deliberate and planful procedures with the goal to make sense of what is read, in which readers themselves play an active role.

Prior research conceptually refers to several reading strategy classifications, i.e., according to strategies’ perceptibility, their approach, their goal, or their nature. Kaufman et al. (1985) classification is based on the perceptibility, differentiating between overt, observable (e.g., taking notes) and covert, non-observable strategies (e.g., imagining). However, this classification rarely occurred in subsequent research. A recent meta-analysis of Lin (2019) refers to research relying on the three other classifications. First, based upon the approach, Block (1986) and Lee-Thompson (2008) distinguish bottom-up (e.g., decoding) and top-down strategies (e.g., using prior knowledge). Second, Mokhtari and Sheorey (2002) classify reading strategies regarding their goal; distinguishing global (e.g., text previewing), problem-solving (e.g., rereading), and support (e.g., highlighting) strategies. Third, as to their nature, cognitive (e.g., summarizing) and metacognitive (e.g., setting goals) strategies have been distinguished ( Phakiti, 2008 ; Zhang, 2018b ). Additionally, motivational strategies (e.g., the use of positive or negative self-talk) are referred to as a third component of this last classification (e.g., O’Malley and Chamot, 1990 ; Pintrich, 2004 ).

Empirical studies on reading strategy use have already focused on different target groups (e.g., children with autism; Jackson and Hanline, 2019 ; English Foreign Language learners; Habók and Magyar, 2019 ), in various subject domains (e.g., English language course; Shih et al., 2018 ; history; ter Beek et al., 2019 ), and at different educational levels (e.g., university level; Phakiti, 2008 ; secondary school students; Habók and Magyar, 2019 ). These studies mainly focus on reading strategy instruction (e.g., ter Beek et al., 2019 ) or on the relationship between reading strategy use and comprehension (e.g., Muijselaar et al., 2017 ). In this respect, good comprehenders appear to handle the use of strategies more strategically and effectively ( Wang, 2016 ; Zhang, 2018b ). Furthermore, good comprehenders dispose of a wide repertoire of strategies and are able to use these adaptively depending on the situation ( Cromley and Wills, 2016 ). On the other hand, the research of Seipel et al. (2017) concludes that both poor and good comprehenders engage in a range of comprehension strategies, adapted moment-by-moment. The difference between both groups concerns which strategies are used (e.g., good comprehenders engage in more high-level processes such as monitoring their progress; Lin, 2019 ), but also when these are used (e.g., good comprehenders make more elaborations toward the text’s end). Finally, several studies examined students’ reading strategy use in relation to student characteristics such as grade, gender, achievement level, or home language (e.g., Denton et al., 2015 ; Van Ammel et al., 2021 ). For example, the study of Denton et al. (2015) on secondary students reported higher strategy use for girls, older students, and high comprehenders.

However, research on late elementary students reading strategy use, and the relation between these students’ strategy use and student characteristics is missing, probably due to the lack of appropriate measurement instruments. In addition, the context of our increasingly diverse society (e.g., between 2009 and 2019 the number of students with a home language other than the instructional language increased from 11.7 to 19.1% in Flanders; Department of Education and Training, 2020 ) is not yet reflected in the currently available instruments. More specifically, existing instruments are designed to be used with either native (e.g., Mokthari and Reichard, 2002 ) or non-native speakers (e.g., Zhang, 2018b ) instead of aiming at measuring students’ strategy use across diverse groups. Therefore, the present study focuses on the strategy use of native (i.e., students who have the instructional language as home language), non-native (i.e., students whose home language is not the instructional language), and bilingual students (i.e., students who use both the instructional language as another language at home).

2.2. Measuring reading comprehension strategies

The variety of definitions and classifications of reading comprehension strategies as found in the literature, is also reflected in the available instruments used to map these strategies. In this respect, eight current instruments are considered in our study ( Carrell, 1989 ; Mokthari and Reichard, 2002 ; Dreyer and Nel, 2003 ; Phakiti, 2003 , 2008 ; Zhang and Seepho, 2013 ; Shih et al., 2018 ; Zhang, 2018b ). The classification according to the approach of reading strategies is reflected in the questionnaire of Carrell (1989) and Shih et al. (2018) , while the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory ( Mokthari and Reichard, 2002 ), which is currently the most used instrument, reflects the classification based upon the goal of reading strategies. Various strategy questionnaires (i.e., Phakiti, 2003 , 2008 ; Zhang and Seepho, 2013 ; Zhang, 2018b ) are based upon the classification regarding their nature. The classification according to the strategy’s perceptibility is not used in published reading strategy instruments; while on the other hand some researchers appear not to rely on any classification (e.g., Dreyer and Nel, 2003 ).

When overviewing the available instruments assessing reading comprehension strategy use, three important aspects should be noticed. First, different classifications are often used separately and are not integrated into a comprehensive framework or measurement instrument. Second, the previously published instruments mostly focus on older students (secondary education; e.g., Mokthari and Reichard, 2002 ; Shih et al., 2018 ; or higher education; e.g., Phakiti, 2008 ; Zhang, 2018b ) and/or focused exclusively on the strategy use of non-native students (e.g., Phakiti, 2003 , 2008 ; Zhang and Seepho, 2013 ; Shih et al., 2018 ). In sum, an instrument attuned to late elementary school students, also taking into account diversity in home language, is currently lacking. A third consideration concerns the measurement method. All abovementioned research uses self-reports to map strategy use. Self-reports are advantageous as the reading process is less disturbed then when using online measurement methods and they are relatively easy to implement on large-scale ( Schellings and van Hout-Wolters, 2011 ; Vandevelde et al., 2013 ). Considering these advantages, there is a permanent need for reliable and valid self-report questionnaires ( Vandevelde et al., 2013 ). On the other hand, it is questionable whether accurate answers can be collected from students with this method ( Cromley and Azevedo, 2006 ), since they might rather provide insight in students’ perceptions than in their actual strategy use ( Bråten and Samuelstuen, 2007 ). However, this concern might partly be met by using task-specific instruments ( Schellings et al., 2013 ). The items of a task-specific instrument examine students’ particular skills or approach in the context of a just completed task (e.g., reading comprehension test), while a general instrument measures students’ skills or approach in general, independent of a particular task. In this respect, general instruments are considered in the literature as a poor predictor of actual strategy use, given the context-, domain-, and goal-dependence of reading comprehension strategies ( Bråten and Samuelstuen, 2007 ). Therefore, task-specific instruments are believed to provide a better estimate of one’s own strategy use ( Schellings et al., 2013 ; Merchie et al., 2014 ). Unfortunately, except for the instrument of Phakiti (2003 , 2008) , currently available questionnaires do not formulate items in a task-specific way (e.g., Shih et al., 2018 ; Zhang, 2018b ).

In conclusion, a new task-specific self-report instrument for late elementary school students, including native, non-native, and bilingual speakers, is urgently needed to map their reading strategy use.

3. Objectives of the study

The first research objective (RO1) is to develop and validate a task-specific self-report questionnaire measuring late elementary school students’ expository reading comprehension strategies. The second research objective (RO2) is to examine individual differences in students’ strategy use (i.e., according to students’ gender, grade, achievement level, and home language) by means of this newly developed instrument.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. participants.

A total of 3,170 students (51.5% fifth-graders, 48.5% sixth-graders, 49.5% boys, 50.5% girls) from 163 classes in 68 different schools in Flanders (Belgium) participated. The average number of participating students was 46.62 ( SD = 24.75) within schools and 19.45 ( SD = 4.77) within classes. A convenience sample method was used to recruit the participants (i.e., inviting Flemish schools by e-mail to participate; response rate of 20.67%). The overall mean age of the students was 11.38 years ( SD = 0.93). 87.3% of the students were native speakers of the instructional language (i.e., Dutch), 7.1% were non-native speakers (i.e., another language than Dutch as home language), and 5.6% were bilingual speakers (i.e., Dutch combined with another language as home language). The research was in line with the country’s privacy legislation as informed consent was obtained for all participants. In this respect, agreeing to participate via the informed consent was the inclusion criteria for the participants to be involved in the study.

4.2. Measurement instrument: Development of the reading comprehension strategies questionnaire

Due to the caveats detected in prior research (see section “Introduction”), a new task-specific measurement instrument was developed and validated ( cf . RO1), consistent with the Standards for Educational and Psychological testing ( American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014 ) and following prior research (e.g., Vandevelde et al., 2013 ; Merchie et al., 2014 ). Based on the guidelines regarding effective test development ( Downing, 2006 ), a multistep process was applied. First, an item pool of 61 items was deducted from eight previously published measurement instruments on reading strategy use ( Carrell, 1989 ; Mokthari and Reichard, 2002 ; Dreyer and Nel, 2003 ; Phakiti, 2003 , 2008 ; Zhang and Seepho, 2013 ; Shih et al., 2018 ; Zhang, 2018b ). Relevant items reflecting the different classifications (i.e., based upon the perceptibility, approach, goal, or nature; see introduction section) were selected to guarantee a diversity of strategies. More specifically, overt and covert (i.e., based upon the perceptibility), bottom-up and top-down (i.e., based upon the approach), global, problem-solving, and support (i.e., based upon the goal), and cognitive and metacognitive (i.e., based upon the nature) reading strategies were included. Further, the items were adjusted to the target group by simplifying words, phrases, or sentences (e.g., “to increase my understanding” was changed into “to better understand the text”). Second, to ensure content validity, the items were reviewed for content quality and clarity by two experts on reading comprehension and instrument development, and by a primary school teacher, resulting only in minor word modifications. For each item the experts debated whether the item was essential, useful, or not necessary ( cf . Lawshe, 1975 ) to ensure reading comprehension strategies are covered in their entirety. In consultation with the teacher the word usage of the questionnaire was aligned with the classroom vocabulary (e.g., “section” was changed into “paragraph”). Third, one fifth grade class ( n = 22) identified confusing words during answering the RCSQ items to avoid construct-irrelevant variance (i.e., examine the comprehensibility and possible ambiguity of the items). After this step, the instrument consisted of 58 items for all students and 3 additional items for non-native and bilingual students (61 items in total).

Items were alphabetically sorted under the titles “before reading,” “during reading,” and “after reading” in order to present the RCSQ items in a logical sequence to the students, as advised by the Flemish Education Council ( Merchie et al., 2019 ). However, the subscales emerging from the exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) analyses were used to calculate students’ scores on the RSCQ and not the abovementioned threefold division in the presentation for the students. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). As substantiated above, developing a task-specific RCSQ was opted for. Therefore, the items referred to a reading comprehension task administered beforehand. This task was representative for a reading comprehension lesson in Flemish education (i.e., reading three short expository texts, followed by 8–12 content-related questions). The items of the RCSQ are expressed in the past tense and explicitly make a link between the questioned strategies and the reading comprehension task (e.g., “Before I started reading, I first looked at the questions”).

4.3. Procedure

The reading comprehension task and RCSQ were administered in a whole-class setting in Dutch during a 50-min class period in the presence of a researcher and the teacher. The students also received a background questionnaire to map their individual student characteristics (e.g., gender, home language). Students’ achievement level was mapped by means of a teacher rating, since experienced teachers can make accurate judgments to this respect ( Südkamp et al., 2012 ). More specifically, teachers indicated their students as high, average, or low achievers.

4.4. Data analysis methods

4.4.1. ro1: parallel, exploratory, and confirmatory factor analyses, measurement invariance tests, and reliability analyses.

In view of RO1, parallel analyses (PA), exploratory factor analyses (EFA), confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) and reliability analyses were conducted to develop and validate the reading comprehension strategies questionnaire.

4.4.1.1. Parallel and exploratory factor analyses

First, the sample was split using SPSS 25 random sampling, to execute EFA ( n = 1585) and CFA ( n = 1585) in two independent subsamples. Chi-square analyses shows no significant differences between both samples in terms of students’ gender (χ2 = 0.016, df = 1, p = 0.901), grade (χ2 = 0.182, df = 1, p = 0.670), achievement level (χ2 = 2.171, df = 2, p = 0.338), and home language (χ2 = 2.673, df = 2, p = 0.263).

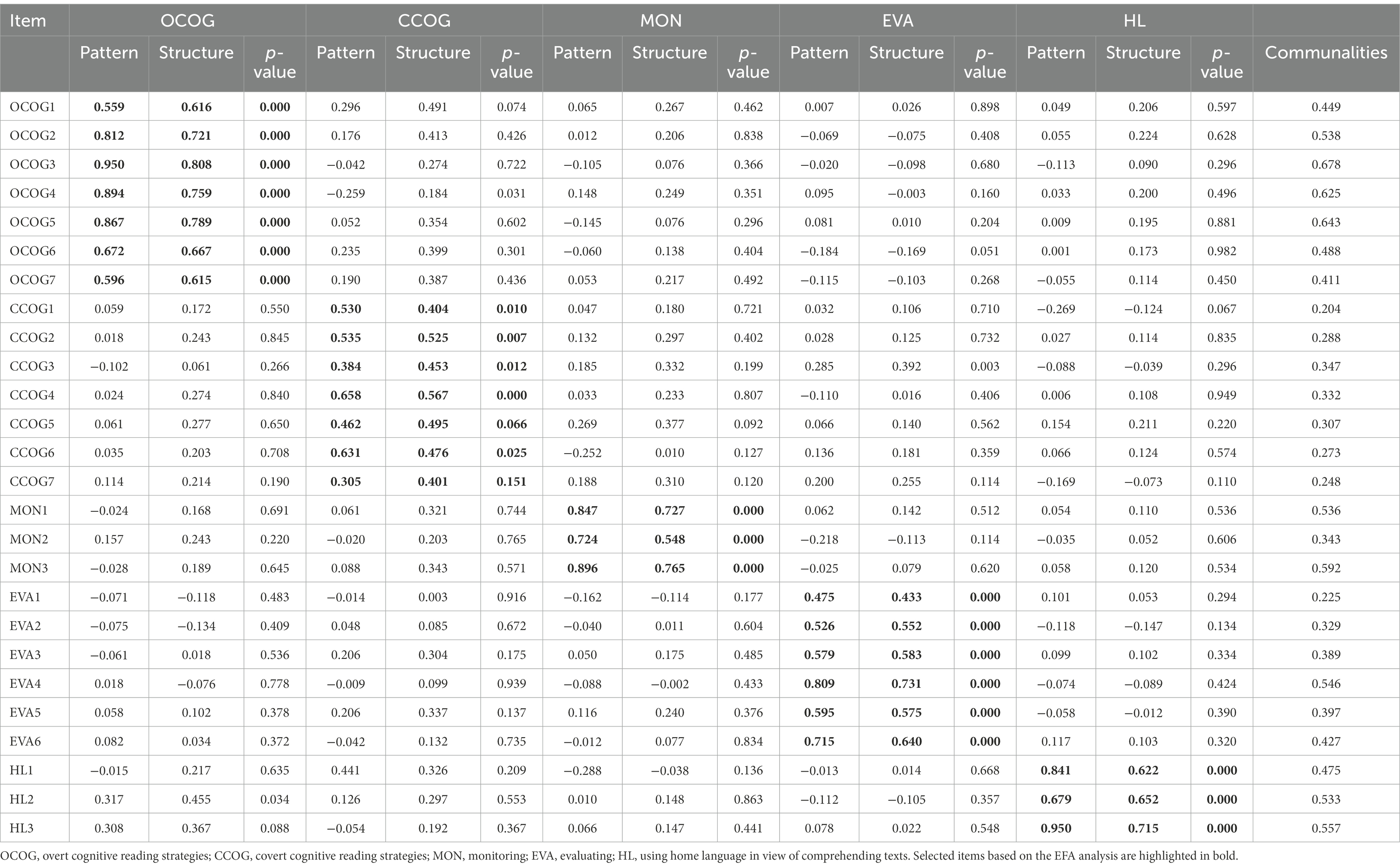

Second, PA and EFA were iteratively conducted on the first sample ( n = 1585) in R 3.6.1 ( R Core Team, 2014 ). PA was performed in order to determine the numbers of factors to be retained, using the 95th percentile of the distribution of random data eigenvalues and 1,000 random data sets ( Hayton et al., 2004 ). The EFA was performed with the lavaan package 0.6–5 ( Rosseel, 2012 ) using a robust Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLR) for the non-normality of the data and geomin rotation to uncover the questionnaire’s underlying structure. Geomin rotation was opted for, since it can offer satisfactory solutions when a factor loading structure is too complex to analyze with other rotation methods ( Hattori et al., 2017 ), as was the case in the present sample. Cluster robust standard errors were applied to account for the data’s nested structure. The number of factors was specified, based on the parallel analyses. Resulting models were iteratively compared, consisting of five-to eight-factor solutions. The following criteria were used to determine the best model fit: (a) significance level to select stable items ( Cudeck and O’Dell, 1994 ), (b) deletion of items with factor loadings under.30 and cross loadings ( Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013 ), and (c) theoretical relevance of the items.

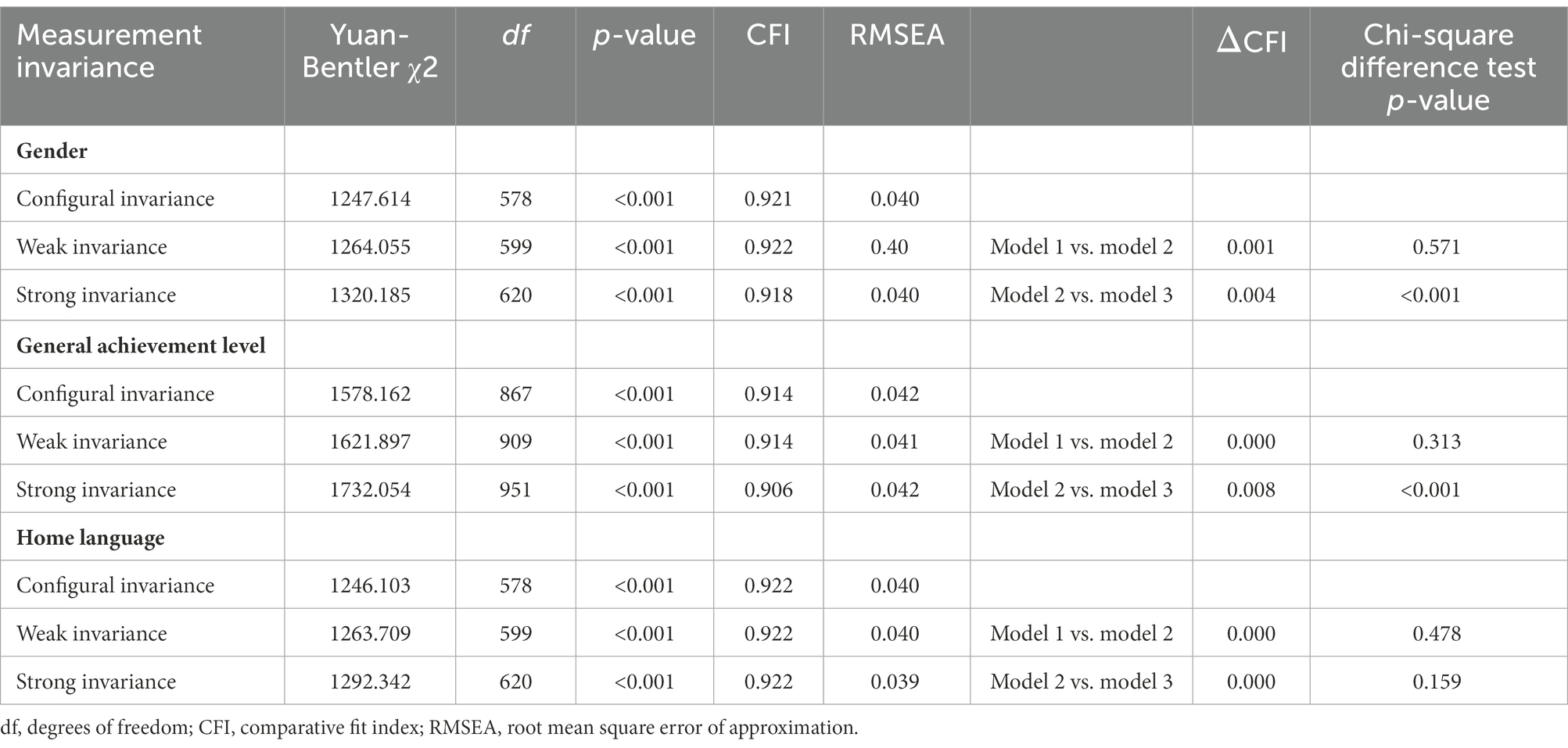

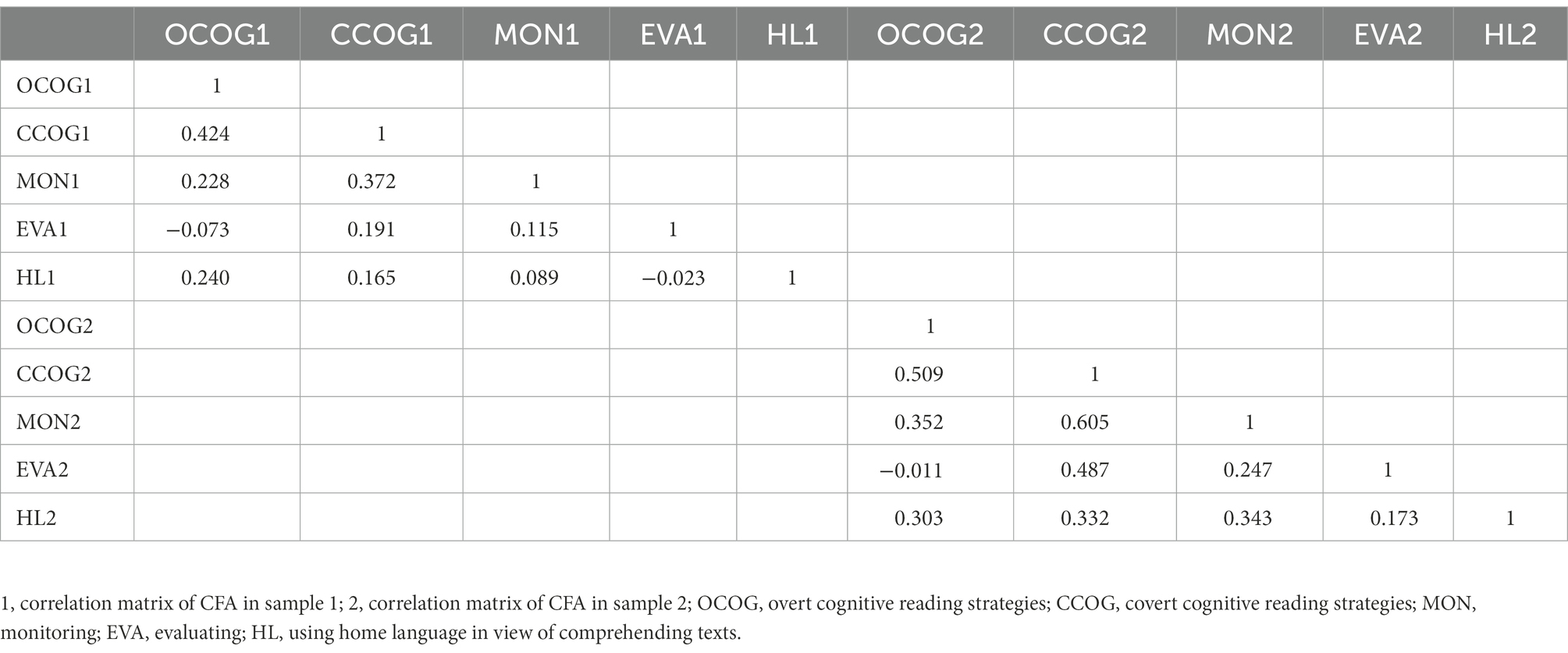

4.4.1.2. Confirmatory analyses