Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Resilience Research Centre, Faculty of Health, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

- Philip Jefferies,

- Michael Ungar

- Published: September 17, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Social anxiety is a fast-growing phenomenon which is thought to disproportionately affect young people. In this study, we explore the prevalence of social anxiety around the world using a self-report survey of 6,825 individuals (male = 3,342, female = 3,428, other = 55), aged 16–29 years (M = 22.84, SD = 3.97), from seven countries selected for their cultural and economic diversity: Brazil, China, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, US, and Vietnam. The respondents completed the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS). The global prevalence of social anxiety was found to be significantly higher than previously reported, with more than 1 in 3 (36%) respondents meeting the threshold criteria for having Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD). Prevalence and severity of social anxiety symptoms did not differ between sexes but varied as a function of age, country, work status, level of education, and whether an individual lived in an urban or rural location. Additionally, 1 in 6 (18%) perceived themselves as not having social anxiety, yet still met or exceeded the threshold for SAD. The data indicate that social anxiety is a concern for young adults around the world, many of whom do not recognise the difficulties they may experience. A large number of young people may be experiencing substantial disruptions in functioning and well-being which may be ameliorable with appropriate education and intervention.

Citation: Jefferies P, Ungar M (2020) Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0239133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133

Editor: Sarah Hope Lincoln, Harvard University, UNITED STATES

Received: March 11, 2020; Accepted: August 31, 2020; Published: September 17, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Jefferies, Ungar. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data files are available from the Open Science Framework repository (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/VCNF7 ).

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: I have read the journal's policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: Unilever funds the lead author's research fellowship at Dalhousie University's Resilience Research Centre, though in no way have they directed this research, its analysis or the reporting or results.

Introduction

Social anxiety occurs when individuals fear social situations in which they anticipate negative evaluations by others or perceive that their presence will make others feel uncomfortable [ 1 ]. From an evolutionary perspective, at appropriate levels social anxiety is adaptive, prompting greater attention to our presentation and reflection on our behaviours. This sensitivity ensures we adjust to those around us to maintain or improve social desirability and avoid ostracism [ 2 ]. However, when out of proportion to threats posed by a normative social situation (e.g., interactions with a peer group at school or in the workplace) and when impairing functioning to a significant degree, it may be classified as a disorder (SAD; formerly ‘social phobia’; [ 3 ]). The hallmark of social anxiety in western contexts is an extreme and persistent fear of embarrassment and humiliation [ 1 , 4 , 5 ]. Elsewhere, notably in Asian cultures, social anxiety may also manifest as embarrassment of others, such as Taijin kyofusho in Japan and Korea [ 6 ]. Common concerns involved in social anxiety include fears of shaking, blushing, sweating, appearing anxious, boring, or incompetent [ 7 ]. Individuals experiencing social anxiety visibly struggle with social situations. They show fewer facial expressions, avert their gaze more often, and express greater difficulty initiating and maintaining conversations, compared to individuals without social anxiety [ 8 ]. Recognising difficulties can lead to dread of everyday activities such as meeting new people or speaking on the phone. In turn, this can lead to individuals reducing their interactions or shying away from engaging with others altogether.

The impact of social anxiety is widespread, affecting functioning in various domains of life and lowering general mood and wellbeing [ 9 ]. For instance, individuals experiencing social anxiety are more likely to be victims of bullying [ 10 , 11 ] and are at greater risk of leaving school early and with poorer qualifications [ 11 , 12 ]. They also tend to have fewer friends [ 13 ], are less likely to marry, more likely to divorce, and less likely to have children [ 14 ]. In the workplace, they report more days absent from work and poorer performance [ 15 ].

A lifetime prevalence of SAD of up to 12% has been reported in the US [ 16 ], and 12-month prevalence rates of .8% have been reported across Europe [ 17 ] and .2% in China [ 18 ]. However, there is an increasing trend to consider a spectrum of social anxiety which takes account of those experiencing subthreshold or subclinical social anxiety, as those experiencing more moderate levels of social anxiety also experience significant impairment across different domains of functioning [ 19 – 21 ]. Therefore, the proportion of individuals significantly affected by social anxiety, which include a substantial proportion of individuals with undiagnosed SAD [ 8 ], may be higher than current estimates suggest.

Studies also indicate younger individuals are disproportionately affected by social anxiety, with prevalence rates at around 10% by the end of adolescence [ 22 – 24 ], with 90% of cases occurring by age 23 [ 16 ]. Higher rates of social anxiety have also been observed in females and are associated with being unemployed [ 25 , 26 ], having lower educational status [ 27 ], and living in rural areas [ 28 , 29 ]. Leigh and Clark [ 30 ] have explored the higher incidence of social anxiety in younger individuals, suggesting that moving from a reliance on the family unit to peer interactions and the development of neurocognitive abilities including public self-consciousness may present a period of greater vulnerability to social anxiety. While most going through this developmentally sensitive period are expected to experience a brief increase in social fears [ 31 ], Leigh and Clark suggest that some who may be more behaviourally inhibited by temperament are at greater risk of developing and maintaining social anxiety.

Recent accounts suggest that levels of social anxiety may be rising. Studies have indicated that greater social media usage, increased digital connectivity and visibility, and more options for non-face-to-face communication are associated with higher levels of social anxiety [ 32 – 35 ]. The mechanism underpinning these associations remains unclear, though studies have suggested individuals with social anxiety favour the relative ‘safety’ of online interactions [ 32 , 36 ]. However, some have suggested that such distanced interactions such as via social media may displace some face to face relationships, as individuals experience greater control and enjoyment online, in turn disrupting social cohesion and leading to social isolation [ 37 , 38 ]. For young people, at a time when the development of social relations is critical, the perceived safety of social interactions that take place at a distance may lead some to a spiral of withdrawal, where the prospect of normal social interactions becomes ever more challenging.

Therefore, in this study, we sought to determine the current prevalence of social anxiety in young people from different countries around the world, in order to clarify whether rates of social anxiety are increasing. Specifically, we used self-report measures (rather than medical records) to discover both the frequency of the disorder, severity of symptoms, and to examine whether differences exist between sexes and other demographic factors associated with differences in social anxiety.

Materials and methods

This study is a secondary analysis of a dataset that was created by Edelman Intelligence for a market research campaign exploring lifestyles and the use of hair care products that was commissioned by Clear and Unilever. The original project to collect the data took place in November 2019, where participants were invited to complete a 20-minute online questionnaire containing measures of social anxiety, resilience, social media usage, and questions related to functioning across various life domains. Participants were randomly recruited through the market research companies Dynata, Online Market Intelligence (OMI), and GMO Research, who hold nationally representative research panels. All three companies are affiliated with market research bodies that set standards for ethical practice. Dynata adheres to the Market Research Society code of conduct; OMI and GMO adhere to the ESOMAR market research code of conduct. The secondary analyses of the dataset were approved by Dalhousie University’s Research Ethics Board.

Participants

There were 6,825 participants involved in the study (male = 3,342, female = 3,428, other = 55), aged 16–29 years (M = 22.84, SD = 3.97), from seven countries selected for their social and economic diversity (Brazil, China, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, US, and Vietnam) (see Table 1 for full sample characteristics). Participant ages were collected in years, but some individuals aged 16–17 were recruited through their parents and their exact age was not given. They were assigned an age of 16.5 years in order to derive the mean age and standard deviation for the full sample.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.t001

Email invitations to participate were sent to 23,346 young people aged 16–29, of whom 76% (n = 17,817) were recruited to take the survey. These were panel members who had previously registered and given their consent to participate in surveys. Sixty-five percent of respondents were ineligible, with 10,816 excluded because they or their close friends worked in advertising, market research, public relations, journalism or the media, or for a manufacturer or retailer of haircare products. A further 176 respondents were excluded for straight-lining (selecting the same response to every item of the social anxiety measure, indicating they were not properly engaged with the survey; [ 39 ]). The final sample comprised 6,825 participants and matched quotas for sex, region, and age, to achieve a sample with demographics representative of each country.

Participants were compensated for their time using a points-based incentive system, where points earned at the end of the survey could be redeemed for gift cards, vouchers, donations to charities, and other products or services.

The survey included the 20-item self-report Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; [ 40 ]). Based on the DSM, the SIAS was originally developed in conjunction with the Social Phobia Scale to determine individuals’ levels of social anxiety and how those with SAD respond to treatment. Both the SIAS and Social Phobia Scale correlate strongly with each other [ 40 – 43 ], but while the latter was developed to assess fears of being observed or scrutinised by others, the SIAS was developed more specifically to assess fears and anxiety related to social interactions with others (e.g., meeting with others, initiating and maintaining conversations). The SIAS discriminates between clinical and non-clinical populations [ 40 , 44 , 45 ] and has also been found to differentiate between those with social anxiety and those with general anxiety [ 46 ], making it a useful clinical screening tool. Although originally developed in Australia, it has been tested and found to work well in diverse cultures worldwide [ 47 – 50 ], and has strong psychometric properties in clinical and non-clinical samples [ 40 , 42 , 43 , 45 – 47 ].

For the current study, all 20 items of the SIAS were included in the survey, though we omitted the three positively-worded items from analyses, as studies have demonstrated that including them results in weaker than expected relationships between the SIAS and other measures, that they hamper the psychometric properties of the measure, and that the SIAS performs better without them [e.g., 51 – 53 ] (the omitted items were ‘I find it easy to make friends my own age’ , ‘I am at ease meeting people at parties , etc’ , and ‘I find it easy to think of things to talk about’ .). One item of the SIAS was also modified prior to use: ‘ I have difficulty talking to attractive persons of the opposite sex’ was altered to ‘ I have difficulty talking to people I am attracted to’ , to make it more applicable to individuals who do not identify as heterosexual, given that the original item was meant to measure difficulty talking to an attractive potential partner [ 54 ].

The questionnaire also included measures of resilience, in addition to other questions concerning functioning in daily life. These were included as part of a corporate social responsibility strategy to investigate the rates of social anxiety and resilience in each target market. A translation agency (Language Connect) translated the full survey into the national languages of the participants.

We analysed social anxiety scores for the overall sample, as well as by country, sex, and age (for sex, given the limited number and heterogeneity of individuals grouped into the ‘other’ category, we only compared males and females). As social anxiety is linked to work status [ 25 ], we also examined differences in SIAS scores between those working and those who were unemployed. Urban/rural differences were also investigated as previous research has suggested anxiety disorders may differ depending on where an individual lives [ 28 ]. Education level [ 27 ], too, was included using completion of secondary education (ISCED level 3) in a subgroup of participants aged 20 years and above to ensure all were above mandatory ages for completing high school. Descriptive statistics are reported for each group with significant differences explored using ANOVA (with Tukey post-hoc tests) or t-tests.

The SIAS is said to be unidimensional when using just the 17 straightforwardly-worded items [ 52 ], with item scores summed to give general social anxiety scores. Higher scores indicate greater levels of social anxiety. Heimberg and colleagues [ 42 ] have suggested a cut-off of 34 on the 20-item SIAS to denote a clinical level of social anxiety (SAD). This level has been adopted in other studies [e.g., 45 ] and found to accurately discriminate between clinical and non-clinical participants [ 53 ]. This threshold for SAD scales to 28.9 when just the 17 items are used, and this is slightly more conservative than others who have used 28 as an adjusted 17-item threshold [ 53 , 55 ]. Therefore, in addition to analyses of raw scores to gauge the severity of social anxiety (and reflect consideration of social anxiety as a spectrum), we also report the proportion of individuals meeting or exceeding this threshold for SAD (≥29) and analyse differences between groups using chi-square tests.

Additionally, despite the unidimensionality of the SIAS, the individual items can be interpreted as examples of contexts where social anxiety may be more or less acutely experienced (e.g., social situations with authority: ‘ I get nervous if I have to speak with someone in authority ’, social situations with strangers: ‘ I am nervous mixing with people I don’t know well ’). Therefore, as social anxiety may be experienced differently depending on culture [ 6 ], we also sorted the items in the measure to understand the top and least concerning contexts for each country.

Finally, we also sought to understand whether individuals perceived themselves as having social anxiety. After completing the SIAS, participants were presented with a definition of social anxiety and asked to reflect on whether they thought this was what they experienced. We contrasted responses with a SIAS threshold analysis to determine discrepancies, including assessment of the proportion of false positives (those who thought they had social anxiety but did not exceed the threshold) and false negatives (those who thought they did not have social anxiety but exceeded the threshold).

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v25 [ 56 ].

As the survey required a response for each item, there were no missing data. The internal reliability of the SIAS was found to be strong (α = .94), with the removal of any item resulting in a reduction in consistency.

Social anxiety by sex, age, and country

In the overall sample, the distribution of social anxiety scores formed an approximately normal distribution with a slightly positive skew, indicating that most respondents scored lower than the midpoint on the measure ( Fig 1 ). However, more than one in three (36%) were found to score above the threshold for SAD. There were no significant differences in social anxiety scores between male and female participants ( t (6768) = -1.37, n.s.) and the proportion of males and females scoring above the SAD threshold did not significantly differ either ( χ 2 (1,6770) = .54, n.s.).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g001

Social anxiety scores significantly differed between countries ( F (6,6818) = 74.85, p < .001, η p 2 = .062). Indonesia had the lowest average scores ( M = 18.94, SD = 13.21) and the US had the highest ( M = 30.35, SD = 15.44). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences ( p s≤.001) between each of the countries, except between Brazil and Thailand, between China and Vietnam, between Russia and China, and between Russia and Indonesia (see Table 2 ). The proportion of individuals exceeding the threshold for SAD was also found to significantly differ between the seven countries (χ 2 (6,6825) = 347.57, p < .001). Like symptom severity, the US had the highest prevalence with more than half of participants surveyed exceeding the threshold (57.6%), while Indonesia had the lowest, with fewer than one in four (22.9%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.t002

A significant age difference was also observed ( F (2,6822) = 39.74, p < .001, η p 2 = .012), where 18-24-year-olds scored significantly higher ( M = 25.33, SD = 13.98) than both 16-17-year-olds ( M = 21.92, SD = 14.24) and 25-29-year-olds ( M = 22.44, SD = 14.22). Also, 25-29-year-olds scored significantly higher than 18-24-year-olds ( p s < .001). The proportion of individuals scoring above the threshold for SAD also significantly differed between age groups (χ 2 (2,6825) = 48.62, p < .001) ( Fig 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g002

A three-way ANOVA confirmed significant main effect differences in social anxiety scores between age groups ( F (2,6728) = 38.93, p < .001, η p 2 = .011) and countries ( F (6,6728) = 45.37, p < .001, η p 2 = .039), as well as the non-significant difference between males and females ( F (1,6728) = .493, n.s.). However, of the interactions between sex, age, and country, the two-way country*age interaction was significant ( F (12,6728) = 1.89, p = .031, η p 2 = .003), where 16-17-year-olds in Indonesia were found to have the lowest scores ( M = 15.70, SD = 13.46) and 25-29-year-olds in the US had the highest ( M = 30.47, SD = 16.17) ( Fig 3 ). There was also a significant country*sex interaction ( F (6,6728) = 2.25, p = .036, η p 2 = .002), where female participants in Indonesia had the lowest scores ( M = 18.07, SD = 13.18) and female participants in the US had the highest ( M = 30.37, SD = 15.11) ( Fig 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g004

Work status

Social anxiety scores were also found to significantly differ in terms of work status (employed/studying/unemployed; F (2,6030) = 9.48, p < .001, η p 2 = .003), with those in employment having the lowest scores ( M = 23.28, SD = 14.32), followed by individuals who were studying ( M = 23.96, SD = 13.50). Those who were unemployed had the highest scores ( M = 26.27, SD = 14.54). Post-hoc tests indicated there were significant differences between those who were employed and unemployed ( p < .001), between those studying and unemployed ( p = .006), but not between those employed and those who were studying. The difference between those exceeding the SAD threshold between groups was also significant (χ 2 (2,6033) = 7.55, p = .023).

Urban/Rural

Social anxiety scores also significantly varied depending on an individual’s place of residence ( F (4,6820) = 9.95, p < .001, η p 2 = .006). However, this was not a linear relationship from urban to rural extremes ( Fig 5 ); instead, those living in suburban areas had the highest scores ( M = 25.64, SD = 14.08) and those in central urban areas had the lowest ( M = 22.70, SD = 14.67). This pattern was reflected in the proportions of individuals exceeding the SAD threshold (χ 2 (4,6825) = 35.84, p < .001).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g005

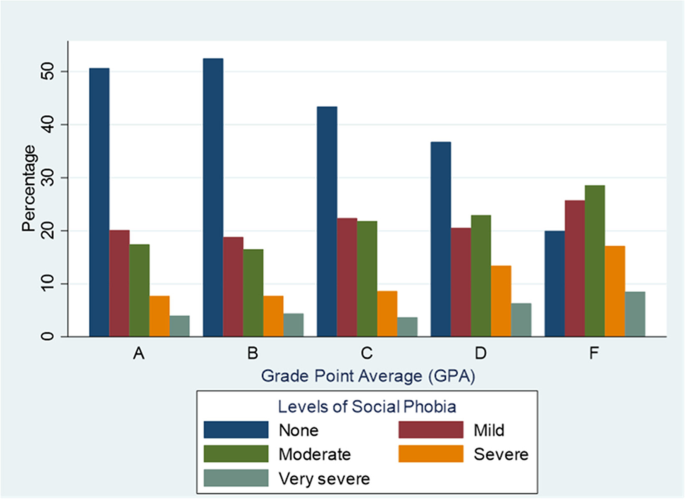

Education level

In the subsample of individuals aged 20 or above, level of education also resulted in a significant differences in social anxiety scores ( t (5071) = 5.51, p < .001), with individuals who completed secondary education presenting lower scores ( M = 23.40, SD = 14.15) than those who had not completed secondary education ( M = 27.94, SD = 15.07). Those exceeding the threshold for SAD also significantly differed (χ 2 (1,5073) = 38.75, p < .001), with half of those who had not finished secondary education exceeding the cut-off (52%), compared to just over a third of those who had (35%).

Concerns by context

Table 3 illustrates the items of the SIAS sorted by severity for each country. For East-Asian countries, speaking with someone in authority was a top concern, but less so for Brazil, Russia, and the US. Patterns became less discernible between countries beyond this top concern, indicating heterogeneity in the specific situations related to social anxiety, although individuals in most countries appeared to be least challenged by mixing with co-workers and chance encounters with acquaintances.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.t003

Self-perceptions of social anxiety

Just over a third of the sample perceived themselves to experience social anxiety (34%). Although this was similar to the proportion of individuals who exceeded the threshold for SAD (36%), perceptions significantly differed from threshold results (χ 2 (1,6825) = 468.80, p < .001). Just fewer than half of the sample (48%) perceived themselves as not being socially anxious and were also below the threshold, and a fifth (18%) perceived themselves as being socially anxious and exceeded the threshold ( Fig 6 ). However, 16% perceived themselves to be socially anxious yet did not exceed the threshold (false positives) and 18% perceived themselves not to be socially anxious yet exceeded the threshold (false negatives). This suggests a large proportion of individuals do not properly recognise their level of social anxiety (over a third of the sample), and perhaps most importantly, that more than 1 in 6 may experience SAD yet not recognise it ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.g006

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133.t004

This study provides an estimate of the prevalence of social anxiety among young people from seven countries around the world. We found that levels of social anxiety were significantly higher than those previously reported, including studies using the 17-item version of the SIAS [e.g., 55 , 57 , 58 ]. Furthermore, our findings show that over a third of participants met the threshold for SAD (23–58% across the different countries). This far exceeds the highest of figures previously reported, such as Kessler and colleague’s [ 16 ] lifetime prevalence rate of 12% in the US.

As this study specifically focuses on social anxiety in young people, it may be that the inclusion of older participants in other studies leads to lower average levels of social anxiety [ 27 , 59 ]. In contrast, our findings show significantly higher rates of SAD than anticipated, and particularly so for individuals aged 18–24. It also extends the argument of authors such as Lecrubier and colleagues [ 60 ] and Leigh and Clark [ 30 ] that developmental challenges during adolescence may provoke social anxiety, especially the crucial later period when leaving school and becoming more independent.

We also found strong variations in levels of social anxiety between countries. Previous explorations of national prevalence rates have been less equivocal, with some reporting differences [ 6 ] while others have not [ 61 ]. Our findings concur with those of Hofmann and colleagues’ [ 6 ] who note that the US has typically high rates of social anxiety, which we also found (in contrast to other countries). However, the authors suggest Russia also has a high prevalence and that Asian cultures typically show lower rates. In contrast, we found samples from Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam had higher rates than in the sample from Russia, and that there were significant differences between Asian countries themselves ( Table 2 ). As our study used the SIAS, which determines how socially anxious an individual is based on their ratings of difficulty in specific social situation, one way of accounting for differences may be to consider the kinds of feared social situations that are covered in the measure. For instance, our breakdown of concerns by country ( Table 3 ) indicates that in Asian countries, speaking with individuals in authority is a strongly feared situation, but this is less challenging in other cultures. For non-Asian countries, one of the strongest concerns was talking about oneself or one’s feelings. In Asian countries, where there is typically less of an emphasis on individualism, talking about oneself may be less stressful if there is less perceived pressure to demonstrate one’s uniqueness or importance. Future investigations could further explore cultural differences in social anxiety across different types of social situations or could confirm cross-cultural social anxiety heterogeneity by using approaches that are less heavily tied to determining social anxiety within given contexts (e.g., a diagnostic interview), as many of the commonly used measures appear to be [ 62 , 63 ].

Our findings also provide mixed support for investigations of other demographic differences in social anxiety. First, previous studies have tended to indicate that female participants score higher than males on measures of social anxiety [ 27 , 64 ]. Although the samples from Brazil and China reflected this, we found no difference between males and females in the overall sample, nor in samples from Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, US, or Vietnam. Sex-related differences in social anxiety have been attributed to gender differences, such as suggestions that girls ruminate more, particularly about relationships with others [ 65 , 66 ]. It is possible that as gender roles and norms vary between countries, and in some instances start to decline, so may differences in social anxiety, which younger generations are likely to reflect first. However, given the unexpected finding that males in Vietnam scored significantly higher than their female counterparts, further investigation is needed to account for the potentially culturally nuanced relationship between sex and social anxiety.

We also confirmed previous findings that higher levels of social anxiety are associated with lower levels of education and being unemployed. Although these findings are in-line with previous research [ 27 , 64 ], our study cannot shed light on causal mechanisms; longitudinal research is required to establish whether social anxiety leads individuals to struggle with school and work, whether struggling in these areas provokes social anxiety, or whether there is a more dynamic relationship.

Finally, we found that 18% of the sample could be classified as “false negatives”. This sizeable group felt they did not have social anxiety, yet their scores on the SIAS considerably exceeded the threshold for SAD. It has been said that SAD often remains undiagnosed [ 67 ], that individuals who seek treatment only do so after 15–20 years of symptoms [ 68 ], and that SAD is often identified when a related condition warrants attention (e.g., depression or alcohol abuse; Schneier [ 5 ]). It has also been reported that many individuals do not recognise social anxiety as a disorder and believe it is just part of their personality and cannot be changed [ 3 ]. Living with an undiagnosed or untreated condition can result in substantial economic consequences for both individuals and society, including a reduced ability to work and a loss of productivity [ 69 ], which may have a greater impact over time compared to those who receive successful treatment. Furthermore, the variety of avoidant (or “safety”) behaviours commonly associated with social anxiety [ 70 , 71 ] mean that affected individuals may struggle or be less able to function socially, and for young people at a time in their lives when relationships with others are particularly crucial [ 72 , 73 ], the consequences may be significant and lasting. Greater awareness of social anxiety and its impact across different domains of functioning may help more young people to recognise the difficulties they experience. This should be accompanied by developing and raising awareness of appropriate services and supports that young people feel comfortable using during these important developmental stages [see 30 , 74 ].

Study limitations

Our ability to infer reasons for the prevalence of SAD is hindered by the present data being cross-sectional, and therefore only allowing for associations to be drawn. We are also unable to confirm the number of clinical cases in the sample, as we did not screen for those who may have received a professional diagnosis of SAD, nor those who are receiving treatment for SAD. Additionally, the use of an online survey incorporating self-report measures incurs the risk of inaccurate responses. Further research could build on this investigation by surveying those in middle and older age to discover whether rates of social anxiety have also risen across other ages, or whether this increase is a youth-related phenomenon. Future investigations could also use diagnostic interviews and track individuals over time to determine the onset and progression of symptoms, including whether those who are subclinical later reach clinical levels, or vice versa, and what might account for such change.

On a global level, we report higher rates of social anxiety symptoms and the prevalence of those meeting the threshold for SAD than have been reported previously. Our findings suggest that levels of social anxiety may be rising among young people, and that those aged 18–24 may be most at risk. Public health initiatives are needed to raise awareness of social anxiety, the challenges associated with it, and the means to combat it.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the role of Edelman Intelligence for collecting the original data on behalf of Unilever and CLEAR as part of their mission to support the resilience of young people.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, assessment and treatment. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society; 2013. Report No.: NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327674/

- 4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013.

- 29. McNeil DW. Evolution of terminology and constructs in social anxiety and its disorders. Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2010. pp. 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375096-9.00001-8

- 33. Dobrean A, Păsărelu C-R. Impact of social media on social anxiety: a systematic review. New Developments in Anxiety Disorders. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2016. https://www.intechopen.com/books/new-developments-in-anxiety-disorders/impact-of-social-media-on-social-anxiety-a-systematic-review

- 44. Blanc ALL, Bruce LC, Heimberg RG, Hope DA, Blanco C, Schneier FR, et al. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of two short forms of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Assessment. 2014 [cited 31 Jan 2020].

- 56. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2017.

- 63. Liebowitz MR, Pharmacopsychiatry MP. Social phobia. 1987.

- 72. Brown BB, Larson J. Peer relationships in adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development, Vol 2, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009. pp. 74–103.

- 73. Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. 6th ed. Handbook of child psychology. 6th ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. pp. 1003–1067. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0316

Social Anxiety Disorder

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, information, published in.

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - American Journal of Psychiatry

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Social Anxiety and Its Maintaining Factors: Accounting for the Role of Neuroticism

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2023

- Volume 45 , pages 469–479, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Caitlin A. Clague 1 &

- Quincy J. J. Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9393-4301 1

5894 Accesses

3 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Models of social anxiety disorder (SAD) and research indicate several cognitive and behavioural maintaining factors that perpetuate social anxiety (i.e., maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, attention towards threat in environment, anticipatory processing, post-event processing, safety behaviours). It is unknown whether these maintaining factors are exclusive to social anxiety or if they are also related to neuroticism – a tendency to experience negative emotions. A community sample of adults ( N = 263) completed measures of relevant constructs (social anxiety, neuroticism, depression, aforementioned maintaining factors). Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the cross-sectional data. In a good fitting model which included depression, social anxiety had unique positive associations with all maintaining factors. Neuroticism had unique positive associations with social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing, but not with any of the other maintaining factors. This model also had superior fit compared to a plausible competing model which did not include neuroticism. Certain maintaining factors may not be exclusive to social anxiety, in contrast to how they are conceptualised in models of SAD. Furthermore, neuroticism may play a role in social anxiety, highlighting the potential of interventions for social anxiety to be advanced through greater incorporation of emotion regulation strategies for negative affect.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of perceived standards on state anxiety, appraisal processes, and negative pre- and post-event rumination in social anxiety disorder.

The influence of anxiety sensitivity, & personality on social anxiety symptoms

The role of loneliness and negative schemas in the moment-to-moment dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a chronic and debilitating mental disorder characterised by significant anxiety in relation to social situations involving the potential for evaluation from other people (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ; Wittchen & Fehm, 2003 ). Psychological models of SAD have highlighted a number of cognitive and behavioural maintaining factors which function to perpetuate social anxiety (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995 ; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997 ; Wong & Rapee, 2016 ). However, within these psychological models, there is limited discussion of the role of personality dimensions. One personality trait that may be relevant to social anxiety is neuroticism, defined as a tendency to experience negative emotions and considered to be one of the five higher-order factors of personality (Goldberg, 1993 ). Given the potential of personality traits to influence psychopathology and its treatment (Bucher et al., 2019 ; Costache et al., 2020 ), further examination of neuroticism in the context of social anxiety and its maintaining factors is warranted.

In a recent psychological model of SAD (Wong & Rapee, 2016 ), maintaining factors for social anxiety are conceptualised as cognitive and behavioural processes that detect and eliminate social-evaluative threat, but which ultimately result in the maintenance of the threat value of social-evaluative stimuli. This in turn maintains maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs and the experience of anxiety in social situations. Within the model, the cognitive and behavioural processes specified can occur before, during or after social situations. First, the cognitive processes developed to detect social-evaluative threat include those that occur during social situations, which involves the directing of attention towards oneself and to one’s surrounds to scan for threat, referred to as self-focus and attention towards threat in the environment, respectively. Self-focused attention is maladaptive as it increases consciousness of internal threat cues (e.g., physiological responses; negative social-evaluative beliefs), whereas attention towards threat in the environment is maladaptive because one’s social context is scanned for evidence that confirms negative evaluation (i.e., threat). In addition, these processes are problematic because they reduce attentional resources available for adaptive task focus (e.g., focusing on what the other person is saying in a conversation). Second, the cognitive processes developed to detect social-evaluative threat also include those that occur before and after social situations, which involves a mental review of upcoming social situations or situations just experienced to scan for threat, referred to as anticipatory processing and post-event processing, respectively. Such mental reviews can involve negative mental imagery, recall of past social failures, and negative views of the self which exaggerate the perceived threat of upcoming social situations or situations just experienced. Third, behavioural processes developed to eliminate social-evaluative threat include those that are performed before or during social situations, referred to as safety behaviours. Safety behaviours aim to reduce the likelihood of the threat of negative evaluation from occurring (e.g., not talking during a conversation to prevent others judging what you say) but can ultimately result in increasing the likelihood of negative evaluation (e.g., not talking results in others thinking you are aloof and unfriendly).

A large body of research has shown positive associations between the aforementioned maintaining factors and social anxiety (maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs: e.g., Wong et al., 2021 ; self-focus and attention towards threat in the environment: e.g., Schultz & Heimberg, 2008 ; anticipatory processing: e.g., Mills et al., 2013 ; post-event processing: e.g., Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008 ; safety behaviours: e.g., Cuming et al., 2009 ). Although theory and empirical research have underscored the importance of the maintaining factors in social anxiety, it is not clear if these maintaining factors are uniquely related to social anxiety. This is particularly the case given evidence that social anxiety is associated with other negative emotional states.

At the disorder level, SAD typically co-occurs with other mental disorders, most commonly other anxiety disorders and depressive disorders (Crome et al., 2015 ; Ruscio et al., 2008 ; Stein et al., 2017 ). Notably, 30–50% of individuals with SAD also have a depressive disorder (e.g., Andrews et al., 2018 ). The co-occurrence of SAD and depression is significant, reflected in models developed to account for the symptom overlap and diagnostic comorbidity between anxiety and depression (e.g., tripartite model; Clark & Watson, 1991 ). Interestingly, there is also research showing that SAD is associated with other negative emotional states such as anger (e.g., Erwin et al., 2003 ) and shame (e.g., Swee et al., 2021 ).

One way to conceptualise these various negative emotional states and capture them in a unified fashion is with the personality trait of neuroticism. Research has shown that neuroticism is elevated in internalising disorders (Kotov et al., 2007 ) and is associated with greater risk of mental disorders (e.g., Kendler & Myers, 2010 ). A number of studies have demonstrated that neuroticism has positive cross-sectional associations with SAD as a diagnostic entity and with social anxiety as a continuous variable (e.g., Allan et al., 2017 ; Bienvenu et al., 2004 ; Costache et al., 2020 ; Levinson et al., 2011 ; Newby et al., 2017 ; Park & Naragon-Gainey, 2020 ). This raises the possibility that neuroticism may also have a link with the maintaining factors of social anxiety. However, no study to date has examined this possibility.

Further supporting the potential for associations between neuroticism and the maintaining factors of social anxiety, neuroticism while mainly characterised as elevated negative emotionality has also been described as involving heightened self-consciousness (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2010 ). This aspect of neuroticism may prompt those maintaining factors of social anxiety which involve attention directed to the self, such as maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, anticipatory processing, and post-event processing (see Wong & Rapee, 2016 ). In addition, studies have shown that neuroticism has positive cross-sectional associations with cognitive and behavioural processes similar to the maintaining factors of social anxiety. For example, neuroticism is positively associated with rumination (e.g., Hervas & Vazquez, 2011 ), a repetitive thinking process similar to anticipatory processing and post-event processing. Neuroticism is also positively associated with behavioural and experiential avoidance (Lommen et al., 2010 ; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018 ), which have overlaps with safety behaviours in the context of social anxiety.

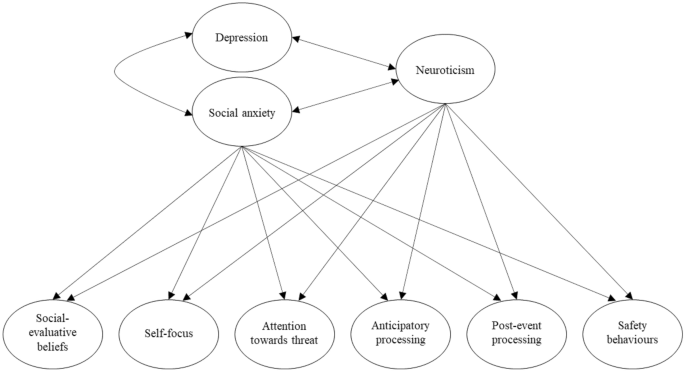

Considering the aforementioned theory and research on the maintaining factors of social anxiety, the link between social anxiety and depression, and the link between social anxiety and neuroticism, this study used a community sample and a structural equation modelling framework to examine a model of social anxiety, depression, and neuroticism, and whether in this context social anxiety and neuroticism would each have unique associations with the maintaining factors of social anxiety. A community sample was used to allow analysis of individuals with a range of social anxiety levels. Based on previous literature (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2010 ; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018 ; Wong & Rapee, 2016 ), we hypothesised that while taking into account depression, both social anxiety and neuroticism would have unique positive associations with each of the maintaining factors (i.e., maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, attention towards threat in the environment, anticipatory processing, post-event processing, safety behaviours; see Fig. 1 ).

Proposed relationships between social anxiety, neuroticism, depression, and the maintaining factors of social anxiety. Double headed arrows reflect expected correlations and single headed arrows reflect expected directional paths. Correlations between the maintaining factors of social anxiety are also expected but are not shown for clarity

Participants

There were 263 adult participants recruited from the Sydney community using social media platforms (e.g., Facebook and Instagram), word-of-mouth, and a university-based research participant recruitment platform. Table 1 shows the demographic and symptom levels of the sample. Participants were entered into a draw to win one of three AU$50 vouchers or, if they were eligible, course credit for their participation. There were no exclusion criteria.

Sample size was determined based on a series of Monte Carlo simulations using the R package simsem (Pornprasertmanit et al., 2021 ). This method involves drawing many samples (i.e., replications) from a hypothesized population model and power for a given parameter is the proportion of the samples for which the null hypothesis (i.e., parameter = 0) is rejected at the .05 level (Muthén & Muthén, 2002 ). As no similar previous study exists, based on our hypothesised model shown in Fig. 1 , we decided for the hypothesised paths from social anxiety and neuroticism to the maintaining factors that medium effect sizes (0.3) would be meaningful to detect. We also set plausible values for the other parameters of the population model (e.g., factor loadings set at 0.75, correlation between social anxiety and neuroticism set at 0.5; see Newby et al., 2017 ; Park & Naragon-Gainey, 2020 ). A final simulation with 1000 replications and alpha = .05 indicated a minimum sample size of 255 would have power > 0.8 to detect medium paths from social anxiety and neuroticism to the maintaining factors. Our actual sample size of 263 exceeded this minimum.

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale – Straightforward Items (SIAS-S) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS)

The 17-item SIAS-S and 20-item SPS are companion measures that assess fears in relation to social interactions and while being observed in daily activities or social performance, respectively (Mattick & Clarke, 1998 ; Rodebaugh et al., 2006 ). Participants rate SIAS and SPS items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all characteristic or true of me) to 4 (Extremely true or characteristic of me), with higher total scores indicating greater social fears. The SIAS-S and SPS have good reliability (see Table 1 ) and validity (Mattick & Clarke, 1998 ; Rodebaugh et al., 2006 ).

Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised–short Form – Neuroticism subscale (EPQR–S–N)

The 12-item EPQR–S–N assesses one’s disposition to neuroticism (Eysenck et al., 1985 ; Sato, 2005 ). Following Sato’s ( 2005 ) recommendations, participants rate EPQR–S–N items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely), with higher total scores indicating greater neuroticism. The EPQR–S–N has good reliability (see Table 1 ) and validity (Sato, 2005 ).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21-item Short Version – Depression Subscale (DASS-D)

The 7-item DASS-D assesses levels of depression over the preceding week (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995 ). Participants rate DASS-D items on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (Did not apply to me at all) to 3 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time), with higher total scores indicating greater depression levels. Following Lovibond and Lovibond ( 1995 ), the DASS-D score was doubled to obtain the full DASS score equivalent. The DASS depression subscale has good internal consistency (see Table 1 ) and validity (Antony et al., 1998 ).

Self-Belief Related to Social Anxiety (SBSA) Scale – Trait Version

The 15-item SBSA assesses maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs and has three subscales: a 4-item high standard beliefs subscale, a 7-item conditional beliefs subscale, and a 4-item unconditional beliefs subscale (Wong et al., 2014 ). Instructions were modified for the current study to assess an individual’s agreement with the beliefs typically in relation to social situations. Participants rate SBSA items on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 (Do not agree to all) to 10 (Strongly agree), with higher total scores indicating stronger maladaptive social-evaluative beliefs. The SBSA has good reliability (see Table 1 ) and validity (Wong et al., 2014 , 2021 ).

Attentional Focus Questionnaire–trait Version (AFQ-T)

The original 24-item AFQ (Rapee & Abbott, 2007 ) assesses attentional focus during a speech task and has two subscales that collectively measure self-focus (4-item attention to past experiences subscale, 5-item attention to physical symptoms subscale) as well as a subscale that measures attention towards threat in the environment (5-item attention to negative evaluation subscale). Instructions and items were modified for the current study to assess an individual’s general tendency to engage in these two forms of attentional focus (i.e., participants asked to rate AFQ-T items based on what they typically focus on during a social situation; example item modification: “I was focusing on my heartbeat” was modified to “I typically focus on my heartbeat.”). Participants rated AFQ-T items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), with higher total scores indicating greater self-focus or attention towards threat in the environment. The original AFQ has good psychometric properties (Rapee & Abbott, 2007 ) and preliminary evidence suggests that the AFQ-T has good reliability (see Table 1 ).

Anticipatory Processing Questionnaire–trait Version (APQ-T)

The original 15-item APQ (Vassilopoulos, 2004 ) assesses anticipatory processing in relation to a specific social situation. Instructions and items were modified for the current study to assess an individual’s general tendency to engage in anticipatory processing (i.e., participants asked to rate APQ-T items based on how they typically are before a social situation; example item modification: “Did you try to stop thinking about the event?” was modified to “Before a social situation, do you typically try to stop thinking about the situation?”). Participants rated APQ-T items on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 10 (Very much so), with higher scores (average of items) indicating greater anticipatory processing. The original APQ has good psychometric properties (Vassilopoulos, 2004 ) and preliminary evidence suggests that the APQ-T has good reliability (see Table 1 ).

Extended Post-event Processing Questionnaire – 15 Item Trait Version (EPEPQ15-T)

The original EPEPQ15 (Wong, 2015 ) assesses post-event processing in relation to a specific social situation and has three subscales: a 7-item cognitive interference subscale, a 4-item negative self subscale, and a 4-item thoughts about the past subscale. Instructions and items were modified for the current study to assess an individual’s general tendency to engage in post-event processing (i.e., participants asked to rate EPEPQ15-T items based on how they typically are after a social situation; example item modification: “After the event was over, did you think about it a lot?” was modified to “After a social situation is over, do you typically think about the situation a lot?”). Participants rated EPEPQ15-T items on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 10 (Very much so), with higher scores (average of items) indicating greater post-event processing. The original EPEPQ15 has good psychometric properties (Wong, 2015 ) and preliminary evidence suggests that the EPEPQ15-T has good reliability (see Table 1 ).

Subtle Avoidance Frequency Examination (SAFE)

The 32-item SAFE assesses an individual’s utilisation of safety behaviours in relation to social situations and has three subscales: a 11-item inhibiting/restricting behaviours subscale, a 15-item active behaviours subscale, and a 6-item management of physical symptoms subscale (Cuming et al., 2009 ). Participants rate SAFE items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of engagement in safety behaviours. The SAFE has good reliability (see Table 1 ) and validity (Cuming et al., 2009 ).

This study was approved by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (H13683). After providing informed consent, participants completed an online demographics questionnaire and then online versions of all study measures (along with other online questionnaires for other studies) presented in a randomised order. This was done while in the presence of a researcher who was on Zoom to maximise data quality.

Statistical Analyses

The R package “lavaan” (Rosseel, 2012 ) was used for the main analyses, which proceeded in two steps: (a) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to examine the fit of a measurement model for the latent variables of interest, and (b) this measurement model was entered into a structural equation model (SEM) to examine the relationships between the latent variables. In the first step, where possible we used the subscales of a measure (e.g., subscales of SAFE) or measures assessing an aspect of a construct (e.g., SIAS-S and SPS measuring facets of social anxiety) as indicators of latent variables (cf. Bagozzi & Heatherton, 1994 ). This was done because we were interested in the constructs broadly defined (as opposed to the specific underlying dimensions), and this also reduced overall model complexity of the SEM in the second step. Where this was not possible (e.g., scale has no subscales), items were used as indicators of latent variables. The latent constructs with indicator variables in parentheses were as follows: social anxiety (SIAS-S and SPS), neuroticism (EPQR-S–N items), depression (DASS-D items), social-evaluative beliefs (SBSA subscales), self-focus (attention to past experiences subscale and attention to physical symptoms subscale of the AFQ-T), attention towards threat in the environment (items of the attention to negative evaluation subscale of the AFQ-T), anticipatory processing (APQ-T items), post-event processing (EPEPQ15-T subscales), and safety behaviour (SAFE subscales). For the second step, relationships between latent variables were specified according to previous theory and research (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2010 ; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018 ; Wong & Rapee, 2016 ). Thus, social anxiety, neuroticism, and depression were expected to be correlated, and both social anxiety and neuroticism were expected to have regression paths to the maintaining factors. Correlations between social anxiety maintaining factors were also allowed (see also Fig. 1 ).

All CFAs were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with robust (Huber-White) standard errors (MLR estimator). This estimator was chosen: (a) to guard against indicator non-normality, and (b) because of the need to treat all indicators as continuous given that subscales were used as indicators for certain latent variables. Notably, there was a small proportion of missing data (see Results) and the MLR estimator can use available data to estimate model parameters if missing values are missing at random (MAR) or missing completely at random (MCAR).

To evaluate model fit, the following fit indices were used (Brown, 2006 ): the χ 2 statistic (smaller values indicate better fit), the comparative fit index (CFI; ≥ .90 suggest acceptable fit; ≥ .95 suggest good fit), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; ≥ .90 suggest acceptable fit; ≥ .95 suggest good fit), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; ≤ .08 suggest acceptable fit; ≤ .05 suggest good fit), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR; ≤ .08 suggest acceptable fit; ≤ .05 suggest good fit).

Preliminary Analyses

Scale means and correlations are shown in Table 1 . All indicators had acceptable levels of skew (all absolute skewness < 3) and kurtosis (all absolute kurtosis < 8; Kline, 2011 ). A range of scores on all the measures was observed, covering the full scale or close to the full scale (see Table 1 ), as was expected given the community sample. At the item level, there were 238 missing data-points out of 38,661 possible (99.38%). At the indicator level, there were 72 missing data-points out of 12,624 possible (99.43% completion rate). Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test was not significant at the indicator level, χ 2 (120) = 99.31, p = .916, indicating the missing data were MCAR. Analyses proceeded with the full sample ( N = 263).

Measurement Model

The CFI and TLI indicated the measurement model did not have an acceptable fit with the data, whereas the RMSEA and SRMR indicated acceptable fit, χ 2 (1238) = 2732.89, CFI = .889, TLI = .881, RMSEA = .071, SRMR = .055. Thus, modification indices were examined. A number of modification indices suggested correlated errors between certain APQ-T items, certain EPQR-S–N items, and certain AFQ-T items. We decided that it would be justifiable to have correlated errors for item pairs within the same scale which had similar wording (see Brown, 2006 ). Based on modification indices, correlated errors were added for 8 APQ-T item pairs (e.g., items of one item pair both referenced avoidance), 3 EPQR-S–N item pairs (e.g., items of one item pair both referenced worry), and 1 AFQ-T item pair (items of item pair both referenced other person). This modified measurement model had acceptable fit on all indices, χ 2 (1226) = 2476.11, CFI = .908, TLI = .900, RMSEA = .065, SRMR = .054. Across all factors, standardised factor loadings ranged from .67 to .98 (all p s < .001), suggesting all indicators were satisfactory markers of their hypothesised construct.

Structural Model

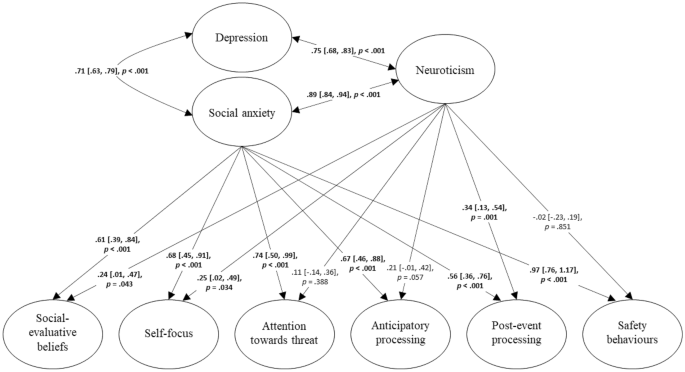

All fit indices suggested that the structural model had acceptable fit with the data, χ 2 (1232) = 2495.14, CFI = .907, TLI = .900, RMSEA = .065, SRMR = .055. Figure 2 shows the standardised estimates of the model. The correlations between social anxiety, depression, and neuroticism were large and significant, ranging from .71 to .89 (all p s < .001). Social anxiety had medium to large significant paths to each of the maintaining factors, ranging from .56 to .97 (all p s < .001). Neuroticism had small significant paths to social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing, ranging from .24 to .34 (all p s < .043). Neuroticism had non-significant paths to attention towards threat in the environment, anticipatory processing, and safety behaviours ranging from –.02 to .21 (all p s > .057).

Relationships between latent variables representing social anxiety, neuroticism, depression, and the maintaining factors of social anxiety. Standardised estimates, 95% confidence intervals in brackets, and p -values are shown. Significant relationships are bolded. Double headed arrows reflect correlations and single headed arrows reflect directional paths. Error terms of certain indicator variables were allowed to correlate (see main text) and correlations between social anxiety maintaining factors were allowed. However, for clarity, only estimates for paths of interest are reported. Full model estimates may be requested from the authors

Exploratory Analysis: Competing Model

A plausible competing structural model was examined. The previous structural model was modified such that neuroticism was removed. Social anxiety and depression were still expected to be correlated, and social anxiety was expected to have regression paths to the maintaining factors. Correlations between social anxiety maintaining factors were again allowed. This model reflected the typical variables examined in relation to social anxiety (i.e., neuroticism is not typically taken into account). This model without neuroticism only had the RMSEA indicating acceptable model fit, χ 2 (1240) = 2841.94, CFI = .882, TLI = .873, RMSEA = .073, SRMR = .300. Hence, the original structural model with neuroticism had superior fit indices. A scaled χ 2 difference test based on Satorra and Bentler ( 2010 ) was also used to compare the difference in fit between the original structural model with neuroticism and the plausible competing structural model without neuroticism (see also Rosseel et al., 2020 , for the lavTestLRT function). Relative to the plausible competing structural model without neuroticism, the original structural model with neuroticism had significantly better fit based on the scaled χ 2 difference test, χ 2 (8) = 214.43, p < .001.

The current study examined whether social anxiety and neuroticism each had unique positive associations with the maintaining factors of social anxiety while taking depression into account. Consistent with predictions, a model reflecting these associations had acceptable fit with the data and indicated that social anxiety had large significant unique positive associations with all maintaining factors. In addition, partially consistent with predictions, this model showed neuroticism had small significant positive unique associations with social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing, but non-significant associations with attention towards threat in the environment, anticipatory processing, and safety behaviours. An exploratory analysis also showed that a plausible competing model which was the original tested model but with neuroticism removed had worse fit indices and significantly worse fit based on a scaled χ 2 difference test relative to the original model.

The finding of large significant unique positive associations between social anxiety and its maintaining factors is consistent with theory (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995 ) and the large body of existing literature showing the same pattern of results (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008 ; Cuming et al., 2009 ; Mills et al., 2013 ; Schultz & Heimberg, 2008 ; Wong et al., 2021 ). The findings of small significant positive unique associations between neuroticism and social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing, but not attention towards threat in the environment, anticipatory processing, and safety behaviours, are novel. These results extend previous research (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2010 ; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018 ) which has suggested but never explicitly tested neuroticism’s potential unique associations with the maintaining factors of social anxiety.

The obtained unique relationships between neuroticism and certain maintaining factors but not others deserve explanation. One possibility is that relative to the other maintaining factors, social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing may involve a greater degree of self-consciousness. Given the conceptualisation of neuroticism as involving heightened self-consciousness (McCrae & Costa, 2010 ), it may thus be the case that individuals with higher levels of neuroticism have a greater tendency to specifically experience social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing. Another potential explanation is that social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing involve a higher level of negative affect compared to the other maintaining factors. Individuals with higher levels of neuroticism may therefore have a predisposition to experience these specific maintaining factors involving greater negative affect. Future research will need to further investigate these potential explanations.

The results of this study have several important implications. First, the results suggest certain maintaining factors of social anxiety may not be exclusively related to social anxiety. This contrasts with prominent theoretical models of SAD (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995 ) which describe the maintaining factors specifically in relation to social anxiety. However, if this study’s results are replicated, in particular with a clinical sample of individuals with SAD, then further research will be needed to determine the exact nature of the relationship between neuroticism and the maintaining factors related to it. Indeed, models of SAD may need to be expanded to include the role that neuroticism plays in relation to social anxiety and its maintaining factors. Second, the results of this study raise the possibility that neuroticism may impact on the treatment of social anxiety. If further research supports the causal role of neuroticism in this context, then neuroticism will need to be considered as part of the assessment of individuals seeking treatment for social anxiety, and existing gold-standard cognitive behavioural therapies for social anxiety (e.g., Clark et al., 2006 ; Rapee et al., 2009 ) may be advanced by incorporating further strategies targeting neuroticism where it is indicated. For example, a greater focus on the practice of cognitive restructuring to encourage cognitive reappraisal for emotion regulation purposes with application to anxiety and other negative affective states may be helpful in this regard (e.g., Dryman & Heimberg, 2018 ). Elements of emotion regulation therapy (e.g., Mennin et al., 2015 ) may also be relevant.

The current study has some limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional and causality cannot be inferred. Future research could evaluate the potential causal or temporal relationships between neuroticism and the maintaining factors by conducting studies with experimental or prospective longitudinal designs. As examples, experimental studies could induce negative emotionality and examine the effects on the maintaining factors as dependent variables, and prospective longitudinal studies could examine whether neuroticism can predict future maintaining factor levels. Second, this study examined a community sample. Although this sample allowed inclusion of individuals with a range of values on variables of interest which allowed this initial study to avoid restriction of range issues, future research should nonetheless replicate this study utilising a clinical sample with SAD as a next step. Third, the majority of participants in our sample were female and were highly educated, limiting generalisability. Future research should replicate the current study in more diverse samples and examine whether certain sample characteristics affect results. Fourth, the current study used modified trait versions of existing measures in the literature. Although these modified trait versions showed promising psychometrics in the current study (e.g., good reliability), further psychometric evaluation of these trait measures is warranted. Fifth, the current study used a specific measure of neuroticism, despite other measures of this construct in the literature (e.g., NEO Personality Inventory-Revised Neuroticism Subscale; Costa & McCrae, 1992 ). Although the EPQR-S–N is a reliable and valid measure of neuroticism, future research may consider replicating the current study with other measures of neuroticism. Finally, the initial measurement model in this study was modified based on modification indices which could have capitalised on chance characteristics in the sample analysed. However, the modifications enabled a sound measurement model before examination of the main structural model.

Overall, this study showed that when social anxiety, neuroticism, and depression are modelled together, social anxiety has unique positive associations with its maintaining factors, and neuroticism additionally has unique positive associations with social-evaluative beliefs, self-focus, and post-event processing. These results suggest that neuroticism may play a role in the context of social anxiety, and raise the interesting potential of existing interventions for social anxiety to be advanced through greater incorporation of emotion regulation strategies.

Data Availability

Data available on request from the authors.

Allan, N. P., Oglesby, M. E., Uhl, A., & Schmidt, N. B. (2017). Cognitive risk factors explain the relations between neuroticism and social anxiety for males and females. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46 , 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1238503

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Andrews, G., Bell, C., Boyce, P., Gale, C., Lampe, L., Marwat, O., Rapee, R., & Wilkins, G. (2018). Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52 , 1109–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418799453

Article Google Scholar

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10 , 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176

Bagozzi, R. P., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self-esteem. Structural Equation Modeling, 1 , 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519409539961

Bienvenu, J., Samuels, J., Costa, P., Reti, I., Eaton, W., & Nestadt, G. (2004). Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety, 20 , 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20026

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research . Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28 , 891–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002

Bucher, M. A., Suzuki, T., & Samuel, D. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review, 70 , 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.002

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. Heimberg, M. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69–93). Guilford Press.

Clark, D. M., Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Grey, N., et al. (2006). Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74 , 568–578. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.74.3.568

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100 , 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual . Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Costache, M. E., Frick, A., Månsson, K., Engman, J., Faria, V., Hjorth, O., Hoppe, J. M., Gingnell, M., Frans, Ӧ, Björkstrand, J., Rosén, J., Alaie, I., Åhs, F., Linnman, C., Wahlstedt, K., Tillfors, M., Marteingsdottir, I., Fredrikson, M., & Furmark, T. (2020). Higher- and lower-order personality traits and cluster subtypes in social anxiety disorder. PLoS ONE, 15 (4), e0232187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232187

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Crome, E., Grove, R., Baillie, A. J., Sunderland, M., Teesson, M., & Slade, T. (2015). DSM-IV and DSM-5 social anxiety disorder in the Australian community. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49 , 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414546699

Cuming, S., Rapee, R. M., Kemp, N., Abbott, M. J., Peters, L., & Gaston, J. E. (2009). A self-report measure of subtle avoidance and safety behaviors relevant to social anxiety: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23 , 879–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.002

Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65 , 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004

Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2003). Anger experience and expression in social anxiety disorder: Pretreatment profile and predictors of attrition and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behavior Therapy, 34 , 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80004-7

Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the Psychoticism Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6 , 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(85)90026-1

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48 , 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Hervas, G., & Vazquez, C. (2011). What else do you feel when you feel sad? Emotional overproduction, neuroticism and rumination. Emotion, 11 , 881–895. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021770

Kendler, K. S., & Myers, J. (2010). The genetic and environmental relationship between major depression and the five-factor model of personality. Psychological Medicine, 40 , 801–806. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291709991140

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Kotov, R., Watson, D., Robles, J. P., & Schmidt, N. B. (2007). Personality traits and anxiety symptoms: The multilevel trait predictor model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45 , 1485–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.011

Levinson, C. A., Langer, J. K., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2011). Self-construal and social anxiety: Considering personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 51 , 355–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.006

Lommen, M. J. J., Engelhard, I. M., & van den Hout, M. A. (2010). Neuroticism and avoidance of ambiguous stimuli: Better safe than sorry? Personality and Individual Differences, 49 , 1001–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.012

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Psychological Foundation.

Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36 , 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2010). NEO inventories professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources .

Mennin, D. S., Fresco, D. M., Ritter, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2015). An open trial of emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and co-occurring depression. Depression and Anxiety, 32 , 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22377

Mills, A. C., Grant, D. M., Lechner, W. V., & Judah, M. R. (2013). Psychometric Properties of the Anticipatory Social Behaviours Questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 35 , 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-013-9339-4

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a monte carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling, 9 , 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0904_8

Naragon-Gainey, K., & Watson, D. (2018). What Lies Beyond Neuroticism? An Examination of the Unique Contributions of Social-Cognitive Vulnerabilities to Internalizing Disorders. Assessment, 25 (2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116659741