CoB Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU)

- Research Assistantships - Career Impacts

- Learn More About a Topic

- Find Scholarly Articles

- Use Scholarly Articles

- Organizing Your Research

- Cite Your Sources

- Libraries Events - Reading Purple

Question? Ask me!

What is a Scholarly Article?

- Defining scholarly articles

- Peer-review

- Other article types

Scholarly articles are articles written by experts and researchers in a field of study to educate or share new discoveries and research. You can use scholarly articles to find out about new innovations, research methodologies, and to dive more deeply into understanding the themes and subtopics of your field of research.

Other names: Scholarly articles are sometimes also called peer-reviewed articles or academic articles. However, not all scholarly articles are peer reviewed.

How to identify a scholarly article:

- Investigate the publisher. Most scholarly articles are published in peer-reviewed journals, e.g. Strategic Management Journal or Journal of Labor Economics

- Browse the structure of the article. Scholarly articles often contain multiples sections and have headers such as introduction, literature review, methodology, discussion, conclusion, etc.

- Check for in-text citations and a large bibliography at the end of the article

- Take note of the language an author uses to write their article. Scholarly articles often use jargon - or specific terms that are used and understood by other professionals in the field. This can make them tricky to understand by others without deeper expertise of the topic.

If you are using a Libraries' database, use a filter to narrow your search to just scholarly articles. This is helpful if you do not want news or magazine articles to show up in your search results.

What is Peer Review?

Some journals require articles to go through a peer review process before accepting it for publication. This means an article is reviewed by other experts in the field to check for accuracy and relevancy before a journal will publish it.

Why Does This Matter?

Many researchers consider peer review articles as a gold standard in research as they have already been evaluated by a panel of experts. Not all scholarly articles are peer reviewed and while both can be helpful to use in your research, you may need to evaluate scholarly articles for quality just like you would a news article before using it in your research project.

How Can I Tell a Scholarly Article from a Peer Reviewed Journal?

Try googling a journal's name. Many times the journal will mention if they require peer review in their about us, but you can also look at their submission criteria or article requirements to find out what process they use.

For example, this is on the about page for the Journal of Business :

"The Journal of Business (JoB) is a peer-reviewed journal with the focus on research articles and case studies in all academic fields of business discipline. The scope of the journal covers the broad range of areas related to business studies including interdisciplinary topics and newly developing areas of business. Submissions comprise research articles – both theoretical and empirical, case studies and reviews of the literature."

When you are searching in a database there may be other articles that you may come across that are not scholarly, but that can be helpful to you in other ways.

Grey Literature

As the name implies, these articles fall into a sort of grey area, they aren't quite scholarly, but they also don't fit anywhere else. The types of articles you might find that fit into this category are:

- Government documents

- Reports, policies, and white papers either produced by an organization, company, or government agency

- Thesis and dissertations, that graduate students produce as part of their degree requirements

- Conference proceedings that researchers produce to share their research with others in more informal ways than through publication

Trade Journals and Magazines

Trade journals are also not the same as a scholarly journal, though they might be easy to confuse. Trade journals are written for professionals in a trade or industry and cover practical topics that impact their career. These articles are written more like news or magazine articles and are meant for working professionals to learn more about innovative technology, relevant news, and current events that impact their industry.

For example, say you decide to pursue a career in managing a fitness center or gym. A relevant trade journal for you would be National Fitness.

How to Get the Most Out of a Scholarly Article

Because of the technical content and level of prior knowledge the author(s) expect their readers to have; being able to get the most out of a scholarly article is a skill that takes time and practice to get good at.

When you are looking for scholarly articles that fulfill your research needs it can be time consuming to read each one top to bottom to determine whether or not it is relevant to your project. Instead try reading the article out of order to determine whether or not a scholarly article is relevant to your project.

- First, read the abstract - if RELEVANT then read the...

- Discussion and/or Conclusion - if still RELEVANT read the...

- Methodology and/or Literature Review - if SOUND, examine the...

- Argument - if BIAS is limited, check the...

- References or bibliography - for other sources you can use in your research

Start by reading a scholarly article in this order. If what you read sounds relevant, then move on to reading the next section. At any time if they article no longer meets your needs, stop reading and move on. Once you complete reading an article out of order, and you determine that it is relevant to your project, it can be helpful to read the article again from top to bottom and annotate your thoughts as you go.

How to Evaluate Scholarly Articles for Quality

Since many scholarly articles go through a peer review process, it can be quicker and easier to evaluate. However, there are still a few things to investigate before using a scholarly article in your research.

Examine the Article

- How current is the article? Don't just look at when the article was published, but also scan the references to make sure the author(s) used current sources.

- Is the methodology used sound? This may require deeper expertise of the methods used in your field to evaluate. Talk with your faculty mentor about the articles you found to help determine what is appropriate for your field.

- Is this relevant to my research topic? Consider if and how the article you found is relevant to your research topic. Does it provide background on your topic or relate to your research in other ways? Even if an article is well cited, it won't be helpful to you if it doesn't connect to your topic.

Investigate Beyond the Article

- Does the journal require peer review?

- Is this journal well regarded by other experts?

- What expertise do the authors have on this topic?

- What other works have these authors published?

- What is it - https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03974-8

- Tools like Retraction Watch can be helpful

It can be helpful to google the author and publisher to see what you can find out about them.

Evaluating a source is to explore the source. You do not need to answer all the questions above each time you evaluate a source. Over time you will become familiar with well regarded journals and authors in your field. All research skills take practice, the more you use this skill the faster and better you will become at it.

- Retraction Watch A database that tracks retractions of scholarly articles

- Retraction - Example This article was retracted from the journal Environmental Science and Pollution research due to a number of concerns including including but not limited to a compromised peer review process, inappropriate or irrelevant references and citation behavior.

- << Previous: Find Scholarly Articles

- Next: Organizing Your Research >>

- Last Updated: Oct 15, 2024 2:23 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.jmu.edu/reu

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of Street Art Graphics

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research Project Evaluation—Learnings from the PATHWAYS Project Experience

Aleksander galas, aleksandra pilat, matilde leonardi, beata tobiasz-adamczyk.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected] ; Tel.: +48-12-423-1003

Received 2018 May 17; Accepted 2018 May 22; Issue date 2018 Jun.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Background: Every research project faces challenges regarding how to achieve its goals in a timely and effective manner. The purpose of this paper is to present a project evaluation methodology gathered during the implementation of the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the EU PATHWAYS Project). The PATHWAYS project involved multiple countries and multi-cultural aspects of re/integrating chronically ill patients into labor markets in different countries. This paper describes key project’s evaluation issues including: (1) purposes, (2) advisability, (3) tools, (4) implementation, and (5) possible benefits and presents the advantages of a continuous monitoring. Methods: Project evaluation tool to assess structure and resources, process, management and communication, achievements, and outcomes. The project used a mixed evaluation approach and included Strengths (S), Weaknesses (W), Opportunities (O), and Threats (SWOT) analysis. Results: A methodology for longitudinal EU projects’ evaluation is described. The evaluation process allowed to highlight strengths and weaknesses and highlighted good coordination and communication between project partners as well as some key issues such as: the need for a shared glossary covering areas investigated by the project, problematic issues related to the involvement of stakeholders from outside the project, and issues with timing. Numerical SWOT analysis showed improvement in project performance over time. The proportion of participating project partners in the evaluation varied from 100% to 83.3%. Conclusions: There is a need for the implementation of a structured evaluation process in multidisciplinary projects involving different stakeholders in diverse socio-environmental and political conditions. Based on the PATHWAYS experience, a clear monitoring methodology is suggested as essential in every multidisciplinary research projects.

Keywords: public health, project process evaluation, internal evaluation, SWOT analysis, project achievements, project management and monitoring

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, a strong discussion on the role of the evaluation process in research has developed, especially in interdisciplinary or multidimensional research [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Despite existing concepts and definitions, the importance of the role of evaluation is often underestimated. These dismissive attitudes towards the evaluation process, along with a lack of real knowledge in this area, demonstrate why we need research evaluation and how research evaluation can improve the quality of research. Having firm definitions of ‘evaluation’ can link the purpose of research, general questions associated with methodological issues, expected results, and the implementation of results to specific strategies or practices.

Attention paid to projects’ evaluation shows two concurrent lines of thought in this area. The first is strongly associated with total quality management practices and operational performance; the second focuses on the evaluation processes needed for public health research and interventions [ 6 , 7 ].

The design and implementation of process’ evaluations in fields different from public health have been described as multidimensional. According to Baranowski and Stables, process evaluation consists of eleven components: recruitment (potential participants for corresponding parts of the program); maintenance (keeping participants involved in the program and data collection); context (an aspect of environment of intervention); resources (the materials necessary to attain project goals); implementation (the extent to which the program is implemented as designed); reach (the extent to which contacts are received by the targeted group); barriers (problems encountered in reaching participants); exposure (the extent to which participants view or read material); initial use (the extent to which a participant conducts activities specified in the materials); continued use (the extent to which a participant continues to do any of the activities); contamination (the extent to which participants receive interventions from outside the program and the extent to which the control group receives the treatment) [ 8 ].

There are two main factors shaping the evaluation process. These are: (1) what is evaluated (whether the evaluation process revolves around project itself or the outcomes which are external to the project), and (2) who is an evaluator (whether an evaluator is internal or external to the project team and program). Although there are several existing gaps in current knowledge about the evaluation process of external outcomes, the use of a formal evaluation process of a research project itself is very rare.

To define a clear evaluation and monitoring methodology we performed different steps. The purpose of this article is to present experiences from the project evaluation process implemented in the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the EU PATHWAYS project. The manuscript describes key project evaluation issues as: (1) purposes, (2) advisability, (3) tools, (4) implementation, and (5) possible benefits. The PATHWAYS project can be understood as a specific case study—presented through a multidimensional approach—and based on the experience associated with general evaluation, we can develop patterns of good practices which can be used in other projects.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

The first step has been the clear definition of what is an evaluation strategy or methodology . The term evaluation is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as the process of judging something’s quality, importance, or value, or a report that includes this information [ 9 ] or in a similar way by the Oxford Dictionary as the making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something [ 10 ]; assessment and in the activity, it is frequently understood as associated with the end rather than with the process. Stufflebeam, in its monograph, defines evaluation as a study designed and conducted to assist some audience to assess an object’s merit and worth. Considering this definition, there are four categories of evaluation approaches: (1) pseudo-evaluation; (2) questions and/or methods-oriented evaluation; (3) improvement/accountability evaluation; (4) social agenda/advocacy evaluation [ 11 ].

In brief, considering Stufflebeam’s classification, pseudo-evaluations promote invalid or incomplete findings. This happens when findings are selectively released or falsified. There are two pseudo-evaluation types proposed by Stufflebeam: (1) public relations-inspired studies (studies which do not seek truth but gather information to solicit positive impressions of program), and (2) politically controlled studies (studies which seek the truth but inappropriately control the release of findings to right-to-know audiences).

The questions and/or methods-oriented approach uses rather narrow questions, which are oriented on operational objectives of the project. Questions oriented uses specific questions, which are of interest by accountability requirements or an expert’s opinions of what is important, while method oriented evaluations favor the technical qualities of program/process. The general concept of these two is that it is better to ask a few pointed questions well to get information on program merit and worth [ 11 ]. In this group, one may find the following evaluation types: (a) objectives-based studies: typically focus on whether the program objectives have been achieved through an internal perspective (by project executors); (b) accountability, particularly payment by results studies: stress the importance of obtaining an external, impartial perspective; (c) objective testing program: uses standardized, multiple-choice, norm-referenced tests; (d) outcome evaluation as value-added assessment: a recurrent evaluation linked with hierarchical gain score analysis; (e) performance testing: incorporates the assessment of performance (by written or spoken answers, or psychomotor presentations) and skills; (f) experimental studies: program evaluators perform a controlled experiment and contrast the outcomes observed; (g) management information system: provide information needed for managers to conduct their programs; (h) benefit-cost analysis approach: mainly sets of quantitative procedures to assess the full cost of a program and its returns; (i) clarification hearing: an evaluation of a trial in which role-playing evaluators competitively implement both a damning prosecution of a program—arguing that it failed, and a defense of the program—and arguing that it succeeded. Next, a judge hears arguments within the framework of a jury trial and controls the proceedings according to advance agreements on rules of evidence and trial procedures; (j) case study evaluation: focused, in-depth description, analysis, and synthesis of a particular program; (k) criticism and connoisseurship: certain experts in a given area do in-depth analysis and evaluation that could not be done in other way; (l) program theory-based evaluation: based on the theory beginning with another validated theory of how programs of a certain type within similar settings operate to produce outcomes (e.g., Health Believe Model, Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation and Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development - thus so called PRECEDE-PROCEED model proposed by L. W. Green or Stage of Change Theory by Prochaska); (m) mixed method studies: include different qualitative and quantitative methods.

The third group of methods considered in evaluation theory are improvement/accountability-oriented evaluation approaches. Among these, there are the following: (a) decision/accountability oriented studies: emphasizes that evaluation should be used proactively to help improve a program and retroactively to assess its merit and worth; (b) consumer-oriented studies: wherein the evaluator is a surrogate consumer who draws direct conclusions about the evaluated program; (c) accreditation/certification approach: an accreditation study to verify whether certification requirements have been/are fulfilled.

Finally, a social agenda/advocacy evaluation approach focuses on the assessment of difference, which is/was intended to be the effect of the program evaluation. The evaluation process in this type of approach works in a loop, starting with an independent evaluator who provides counsel and advice towards understanding, judging and improving programs as evaluations to serve the client’s needs. In this group, there are: (a) client-centered studies (or responsive evaluation): evaluators work with, and for, the support of diverse client groups; (b) constructivist evaluation: evaluators are authorized and expected to maneuver the evaluation to emancipate and empower involved and affected disenfranchised people; (c) deliberative democratic evaluation: evaluators work within an explicit democratic framework and uphold democratic principles in reaching defensible conclusions; (d) utilization-focused evaluation: explicitly geared to ensure that program evaluations make an impact.

1.2. Implementation of the Evaluation Process in the EU PATHWAYS Project

The idea to involve the evaluation process as an integrated goal of the PATHWAYS project was determined by several factors relating to the main goal of the project, defined as a special intervention to existing attitudes to occupational mobility and work activity reintegration of people of working age, suffering from specific chronic conditions into the labor market in 12 European Countries. Participating countries had different cultural and social backgrounds and different pervasive attitudes towards people suffering from chronic conditions.

The components of evaluation processes previously discussed proved helpful when planning the PATHWAYS evaluation, especially in relation to different aspects of environmental contexts. The PATHWAYS project focused on chronic conditions including: mental health issues, neurological diseases, metabolic disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and persons with cancer. Within this group, the project found a hierarchy of patients and social and medical statuses defined by the nature of their health conditions.

According to the project’s monitoring and evaluation plan, the evaluation process followed specific challenges defined by the project’s broad and specific goals and monitored the progress of implementing key components by assessing the effectiveness of consecutive steps and identifying conditions supporting the contextual effectiveness. Another significant aim of the evaluation component on the PATHWAYS project was to recognize the value and effectiveness of using a purposely developed methodology—consisting of a wide set of quantitative and qualitative methods. The triangulation of methods was very useful and provided the opportunity to develop a multidimensional approach to the project [ 12 ].

From the theoretical framework, special attention was paid to the explanation of medical, cultural, social and institutional barriers influencing the chance of employment of chronically ill persons in relation to the characteristics of the participating countries.

Levels of satisfaction with project participation, as well as with expected or achieved results and coping with challenges on local–community levels and macro-social levels, were another source of evaluation.

In the PATHWAYS project, the evaluation was implemented for an unusual purpose. This quasi-experimental design was developed to assess different aspects of the multidimensional project that used a variety of methods (systematic review of literature, content analysis of existing documents, acts, data and reports, surveys on different country-levels, deep interviews) in the different phases of the 3 years. The evaluation monitored each stage of the project and focused on process implementation, with the goal of improving every step of the project. The evaluation process allowed to perform critical assessments and deep analysis of benefits and shortages of the specific phase of the project.

The purpose of the evaluation was to monitor the main steps of the Project, including the expectations associated with a multidimensional, methodological approach used by PATHWAYS partners, as well as improving communication between partners, from different professional and methodological backgrounds involved in the project in all its phases, so as to avoid errors in understanding the specific steps as well as the main goals.

2. Materials and Methods

The paper describes methodology and results gathered during the implementation of Work Package 3, Evaluation of the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the PATHWAYS) project. The work package was intended to keep internal control over the run of the project to achieve timely fulfillment of tasks, milestones, and purpose by all project partners.

2.1. Participants

The project consortium involved 12 partners from 10 different European countries. There were academics (representing cross-disciplinary research including socio-environmental determinants of health, clinicians), institutions actively working for the integration of people with chronic and mental health problems and disability, educational bodies (working in the area of disability and focusing on inclusive education), national health institutes (for rehabilitation of patients with functional and workplace impairments), an institution for inter-professional rehabilitation at a country level (coordinating medical, social, educational, pre-vocational and vocational rehabilitation), a company providing patient-centered services (in neurorehabilitation). All the partners represented vast knowledge and high-level expertise in the area of interest and all agreed with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-ICF and of the biopsychosocial model of health and functioning. The consortium was created based on the following criteria:

vision, mission, and activities in the area of project purposes,

high level of experience in the area (supported by publications) and in doing research (being involved in international projects, collaboration with the coordinator and/or other partners in the past),

being able to get broad geographical, cultural and socio-political representation from EU countries,

represent different stakeholder type in the area.

2.2. Project Evaluation Tool

The tool development process involved the following steps:

Review definitions of ‘evaluation’ and adopt one which consorts best with the reality of public health research area;

Review evaluation approaches and decide on the content which should be applicable in the public health research;

Create items to be used in the evaluation tool;

Decide on implementation timing.

According to the PATHWAYS project protocol, an evaluation tool for the internal project evaluation was required to collect information about: (1) structure and resources; (2) process, management and communication; (3) achievements and/or outcomes and (4) SWOT analysis. A mixed methods approach was chosen. The specific evaluation process purpose and approach are presented in Table 1 .

Evaluation purposes and approaches adopted for the purpose in the PATHWAYS project.

* Open ended questions are not counted here.

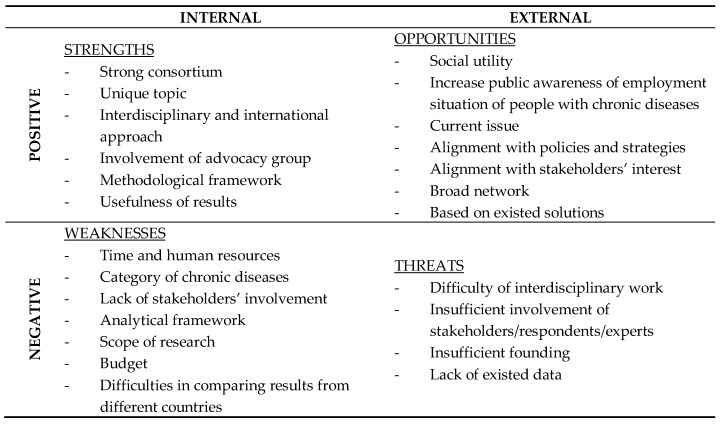

The tool was prepared following different steps. In the paragraph to assess structure and resources, there were questions about the number of partners, professional competences, assigned roles, human, financial and time resources, defined activities and tasks, and the communication plan. The second paragraph, process, management and communication, collected information about the coordination process, consensus level, quality of communication among coordinators, work package leaders, and partners, whether project was carried out according to the plan, involvement of target groups, usefulness of developed materials, and any difficulties in the project realization. Finally, the paragraph achievements and outcomes gathered information about project specific activities such as public-awareness raising, stakeholder participation and involvement, whether planned outcomes (e.g., milestones) were achieved, dissemination activities, and opinions on whether project outcomes met the needs of the target groups. Additionally, it was decided to implement SWOT analysis as a part of the evaluation process. SWOT analysis derives its name from the evaluation of Strengths (S), Weaknesses (W), Opportunities (O), and Threats (T) faced by a company, industry or, in this case, project consortium. SWOT analysis comes from the business world and was developed in the 1960s at Harvard Business School as a tool for improving management strategies among companies, institutions, or organization [ 13 , 14 ]. However, in recent years, SWOT analysis has been adapted in the context of research to improve programs or projects.

For a better understanding of SWOT analysis, it is important to highlight the internal features of Strengths and Weaknesses, which are considered controllable. Strengths refers to work inside the project such as capabilities and competences of partners, whereas weaknesses refers to aspects, which needs improvement, such as resources. Conversely, Opportunities and Threats are considered outside factors and uncontrollable [ 15 ]. Opportunities are maximized to fit the organization’s values and resources and threats are the factors that the organization is not well equipped to deal with [ 9 ].

The PATHWAYS project members participated in SWOT analyses every three months. They answered four open questions about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified in evaluated period (last three months). They were then asked to assess those items on 10-point scale. The sample included results from nine evaluated periods from partners from ten different countries.

The tool for the internal evaluation of the PATHWAYS project is presented in Appendix A .

2.3. Tool Implementation and Data Collection

The PATHWAYS on-going evaluation took place at three-month intervals. It consisted of on-line surveys, and every partner assigned a representative who was expected to have good knowledge on the progress of project’s progress. The structure and resources were assessed only twice, at the beginning (3rd month) and at the end (36th month) of the project. The process, management, and communication questions, as well as SWOT analysis questions, were asked every three months. The achievements and outcomes questions started after the first year of implementation (i.e., after 15th month), and some of items in this paragraph, (results achieved, whether project outcomes meet the needs of the target groups and published regular publications), were only implemented at the end of the project (36th month).

2.4. Evaluation Team

The evaluation team was created from professionals with different backgrounds and extensive experience in research methodology, sociology, social research methods and public health.

The project started in 2015 and was carried out for 36 months. There were 12 partners in the PATHWAYS project, representing Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, Poland, Slovenia and Spain and a European Organization. The on-line questionnaire was sent to all partners one week after the specified period ended and project partners had at least 2 weeks to fill in/answer the survey. Eleven rounds of the survey were performed.

The participation rate in the consecutive evaluation surveys was 11 (91.7%), 12 (100%), 12 (100%), 11 (91.7%), 10 (83.3%), 11 (91.7%), 11 (91.7%), 10 (83.3%), and 11 (91.7%) till the project end. Overall, it rarely covered the whole group, which may have resulted from a lack of coercive mechanisms at a project level to answer project evaluation questions.

3.1. Evaluation Results Considering Structure and Resources (3rd Month Only)

A total of 11 out of 12 project partners participated in the first evaluation survey. The structure and resources of the project were not assessed by the project coordinator and as such, the results in represent the opinions of the other 10 participating partners. The majority of respondents rated the project consortium as having at least adequate professional competencies. In total eight to nine project partners found human, financial and time resources ‘just right’ and the communication plan ‘clear’. More concerns were observed regarding the clarity of tasks, what is expected from each partner, and how specific project activities should be or were assigned.

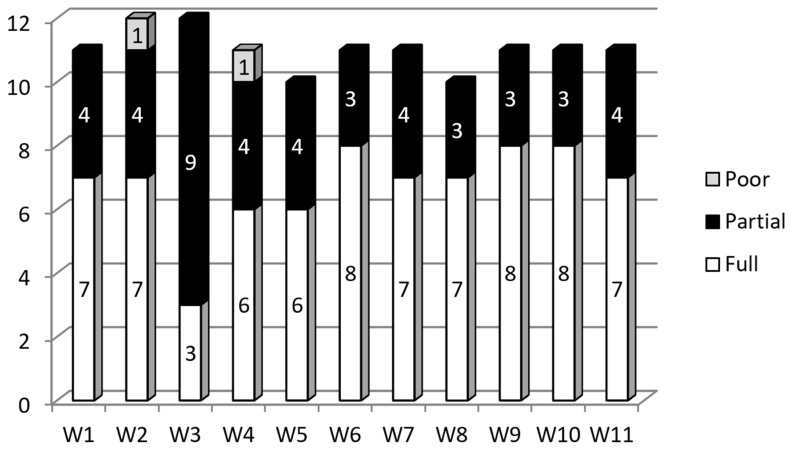

3.2. Evaluation Results Considering Process, Management and Communication

The opinions about project coordination, communication processes (with coordinator, between WP leaders, and between individual partners/researchers) were assessed as ‘good’ and ‘very good’, along the whole period. There were some issues, however, when it came to the realization of specific goals, deliverables, or milestones of the project.

Given the broad scope of the project and participating partner countries, we created a glossary to unify the common terms used in the project. It was a challenge, as during the project implementation there were several discussions and inconsistencies in the concepts provided ( Figure 1 ).

Partners’ opinions about the consensus around terms (shared glossary) in the project consortium across evaluation waves (W1—after 3-month realization period, and at 3-month intervals thereafter).

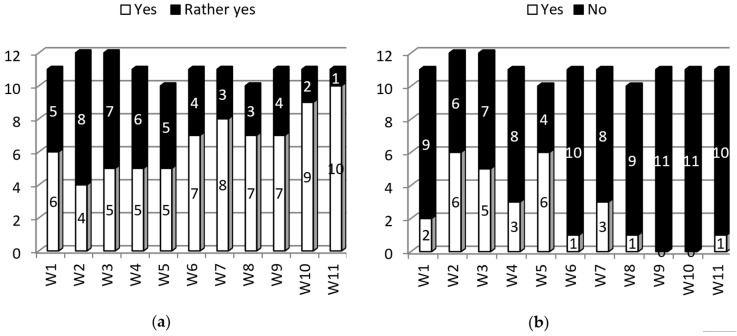

Other issues, which appeared during project implementation, were recruitment of, involvement with, and cooperation with stakeholders. There was a range of groups to be contacted and investigated during the project including individual patients suffering from chronic conditions, patients’ advocacy groups and national governmental organizations, policy makers, employers, and international organizations. It was found that during the project, the interest and the involvement level of the aforementioned groups was quite low and difficult to achieve, which led to some delays in project implementation ( Figure 2 ). This was the main cause of smaller percentages of “what was expected to be done in designated periods of project realization time”. The issue was monitored and eliminated by intensification of activities in this area ( Figure 3 ).

Partners’ reports on whether the project had been carried out according to the plan ( a ) and the experience of any problems in the process of project realization ( b ) (W1—after 3-month realization period, and at 3-month intervals thereafter).

Partners’ reports on an approximate estimation (in percent) of the project plan implementation (what has been done according to the plan) ( a ) and the involvement of target groups (W1—after 3-month realization period, and at 3-month intervals thereafter) ( b ).

3.3. Evaluation Results Considering Achievements and Outcomes

The evaluation process was prepared to monitor project milestones and deliverables. One of the PATHWAYS project goals was to raise public awareness surrounding the reintegration of chronically ill people into the labor market. This was assessed subjectively by cooperating partners and only half (six) felt they achieved complete success on that measure. The evaluation process monitored planned outcomes according to: (1) determination of strategies for awareness rising activities, (2) assessment of employment-related needs, and (3) development of guidelines (which were planned by the project). The majority of partners completely fulfilled this task. Furthermore, the dissemination process was also carried out according to the plan.

3.4. Evaluation Results from SWOT

3.4.1. strengths.

Amongst the key issues identified across all nine evaluated periods ( Figure 4 ), the “strong consortium” was highlighted as the most important strength of the PATHWAYS project. The most common arguments for this assessment were the coordinator’s experience in international projects, involvement of interdisciplinary experts who could guarantee a holistic approach to the subject, and a highly motivated team. This was followed by the uniqueness of the topic. Project implementers pointed to the relevance of the analyzed issues, which are consistent with social needs. They also highlighted that this topic concerned an unexplored area in employment policy. The interdisciplinary and international approach was also emphasized. According to the project implementers, the international approach allowed mapping of vocational and prevocational processes among patients with chronic conditions and disability throughout Europe. The interdisciplinary approach, on the other hand, enabled researchers to create a holistic framework that stimulates innovation by thinking across boundaries of particular disciplines—especially as the PATHWAYS project brings together health scientists from diverse fields (physicians, psychologists, medical sociologists, etc.) from ten European countries. This interdisciplinary approach is also supported by the methodology, which is based on a mixed-method approach (qualitative and quantitative data). The involvement of an advocacy group was another strength identified by the project implementers. It was stressed that the involvement of different types of stakeholders increased validity and social triangulation. It was also assumed that it would allow for the integration of relevant stakeholders. The last strength, the usefulness of results, was identified only in the last two evaluation waves, when the first results had been measured.

SWOT Analysis—a summary of main issues reported by PATHWAYS project partners.

3.4.2. Weaknesses

The survey respondents agreed that the main weaknesses of the project were time and human resources. The subject of the PATHWAYS project turned out to be very broad, and therefore the implementers pointed to the insufficient human resources and inadequate time for the implementation of individual tasks, as well as the project overall. This was related to the broad categories of chronic diseases chosen for analysis in the project. On one hand, the implementers complained about the insufficient number of chronic diseases taken into account in the project. On the other hand, they admitted that it was not possible to cover all chronic diseases in details. The scope of the project was reported as another weakness. In the successive waves of evaluation, the implementers more often pointed out that it was hard to cover all relevant topics.

Nevertheless, some of the major weaknesses reported during the project evaluation were methodological problems. Respondents pointed to problems with the implementation of tasks on a regular basis. For example, survey respondents highlighted the need for more open questions in the survey that the questionnaire was too long or too complicated, that the tools were not adjusted for relevancy in the national context, etc. Another issue was that the working language was English, but all tools or survey questionnaire needed to be translated into different languages and this issue was not always considered by the Commission in terms of timing and resources. This issue could provide useful for further projects, as well as for future collaborations.

The difficulties of involving stakeholders were reported, especially during tasks, which required their active commitment, like participation in in-depth interviews or online questionnaires. Interestingly, the international approach was considered both strength and weakness of the project. The implementers highlighted the complexity of making comparisons between health care and/or social care in different countries. The budget was also identified as a weakness by the project implementers. More funds obtained from the partners could have helped PATHWAYS enhance dissemination and stakeholders’ participation.

3.4.3. Opportunities

A list of seven issues within the opportunities category reflects the positive outlook of survey respondents from the beginning of the project to its final stage. Social utility was ranked as the top opportunity. The implementers emphasized that the project could fill a gap between the existing solutions and the real needs of people with chronic diseases and mental disorders. The implementers also highlighted the role of future recommendations, which would consist of proposed solutions for professionals, employees, employers, and politicians. These advantages are strongly associated with increasing awareness of employment situations of people with chronic diseases in Europe and the relevance of the problem. Alignment with policies, strategies, and stakeholders’ interests were also identified as opportunities. The topic is actively discussed on the European and national level, and labor market and employment issues are increasingly emphasized in the public discourse. What is more relevant is that the European Commission considers the issue crucial, and the results of the project are in line with its requests for the future. The implementers also observed increasing interest from the stakeholders, which is very important for the future of the project. Without doubt, the social network of project implementers provides a huge opportunity for the sustainability of results and the implementation of recommendations.

3.4.4. Threats

Insufficient response from stakeholders was the top perceived threat selected by survey respondents. The implementers indicated that insufficient involvement of stakeholders resulted in low response rates in the research phase, which posed a huge threat for the project. The interdisciplinary nature of the PATHWAYS project was highlighted as a potential threat due to differences in technical terminology and different systems of regulating the employment of persons with reduced work capacity in each country, as well as many differences in the legislation process. Insufficient funding and lack of existing data were identified as the last two threats.

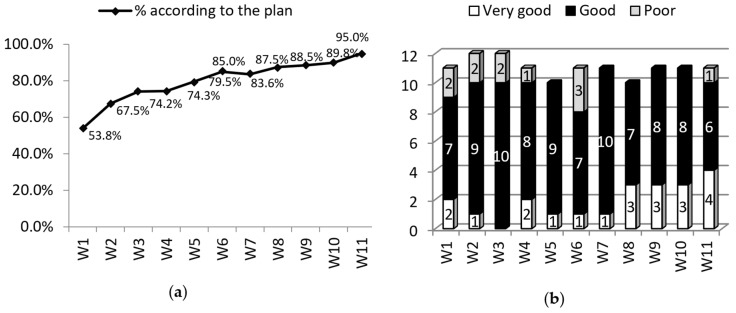

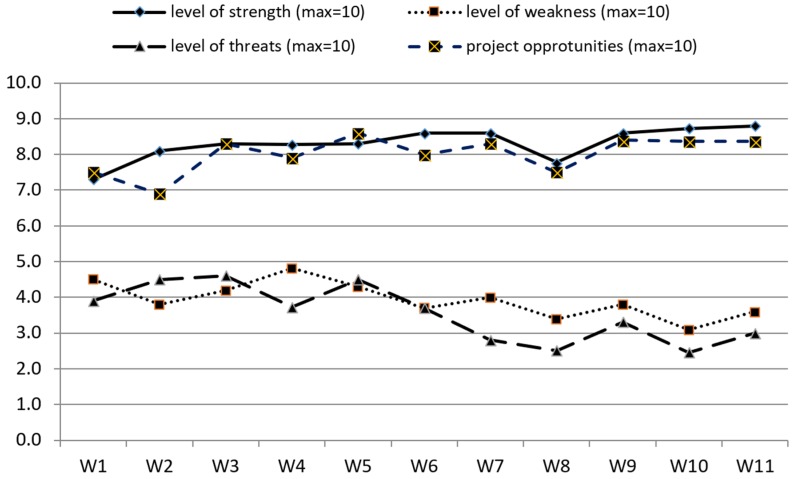

One novel aspect of the evaluation process in the PATHWAYS project was a numerical SWOT analysis. Participants were asked to score strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats from 0 (meaning the lack of/no strengths, weaknesses) to 10 (meaning a lot of ... several ... strengths, weaknesses). This concept enabled us to get a subjective score of how partners perceive the PATHWAYS project itself and the performance of the project, as well as how that perception changes over time. Data showed an increase in both strengths and opportunities and a decrease in weaknesses and threats over the course of project implementation ( Figure 5 ).

Numerical SWOT, combined, over a period of 36 months of project realization (W1—after 3-month realization period, and at 3-month intervals thereafter).

4. Discussion

The need for project evaluation was born from an industry facing challenges regarding how to achieve market goals in more efficient way. Nowadays, every process, including research project implementation, faces questions regarding its effectiveness and efficiency.

The challenge of a research project evaluation is that the majority of research projects are described as unique, although we believe several projects face similar issues and challenges as those observed in the PATHWAYS project.

The main objectives of the PATHWAYS Project were (a) to identify integration and re-integration strategies that are available in Europe and beyond for individuals with chronic diseases and mental disorders experiencing work-related problems (such as unemployment, absenteeism, reduced productivity, stigmatization), (b) to determine their effectiveness, (c) to assess the specific employment-related needs of those people, and (d) to develop guidelines supporting the implementation of effective strategies of professional integration and reintegration. The broad area of investigation, partial knowledge in the field, diversity of determinants across European Union countries, and involvement with stakeholders representing different groups caused several challenges in the project, including:

problem : uncovered, challenging, demanding (how to encourage stakeholders to participate, share experiences),

diversity : different European regions; different determinants: political, social, cultural; different public health and welfare systems; differences in law regulations; different employment policies and issues in the system,

multidimensionality of research: some quantitative, qualitative studies including focus groups, opinions from professionals, small surveys in target groups (workers with chronic conditions).

The challenges to the project consequently led to several key issues, which should be taken, into account during project realization:

partners : with their own expertise and interests; different expectations; different views on what is more important to focused on and highlighted;

issues associated with unification : between different countries with different systems (law, work-related and welfare definitions, disability classification, others);

coordination : as multidimensionality of the project may have caused some research activities by partners to move in a wrong direction (data, knowledge which is not needed for the project purposes), a lack of project vision in (some) partners might postpone activities through misunderstanding;

exchange of information : multidimensionality, the fact that different tasks were accomplished by different centers and obstacles to data collection required good communication methods and smooth exchange of information.

Identified Issues and Implemented Solutions

There were several issues identified through the semi-internal evaluation process performed during the project. Those, which might be more relevant for the project realization, are mentioned in the Table 2 .

Issues identified by the evaluation process and solutions implemented.

The PATHWAYS project included diverse partners representing different areas of expertise and activity (considering broad aspect of chronic diseases, decline in functioning and of disability, and its role in a labor market) in different countries and social security systems, which caused a challenge when developing a common language to achieve effective communication and better understanding of facts and circumstances in different countries. The implementation of continuous project process monitoring, and proper adjustment, enabled the team to overcome these challenges.

The evaluation tool has several benefits. First, it covers all key areas of the research project including structure and available resources, the run of the process, quality and timing of management and communication, as well as project achievements and outcomes. Continuous evaluation of all of these areas provides in-depth knowledge about project performance. Second, the implementation of SWOT tool provided opportunities to share out good and bad experiences by all project partners, and the use of a numerical version of SWOT provided a good picture about inter-relations strengths—weaknesses and opportunities—threats in the project and showed the changes in their intensity over time. Additionally, numerical SWOT may verify whether perception of a project improves over time (as was observed in the PATHWAYS project) showing an increase in strengths and opportunities and a decrease in weaknesses and threats. Third, the intervals in which partners were ‘screened’ by the evaluation questionnaire seems to be appropriate, as it was not very demanding but frequent enough to diagnose on-time some issues in the project process.

The experiences with the evaluation also revealed some limitations. There were no coercive mechanisms for participation in the evaluation questionnaires, which may have caused a less than 100% response rate in some screening surveys. Practically, that was not a problem in the PATHWAYS project. Theoretically, however, this might lead to unrevealed problems, as partners experiencing troubles might not report them. Another point is asking about quality of the consortium to the project coordinator, which has no great value (the consortium is created by the coordinator in the best achievable way and it is hard to expect other comments especially at the beginning of the project). Regarding the tool itself, the question Could you give us approximate estimation (in percent) of the project plan realization (what has been done according to the plan)? was expected to collect information about the project partners collecting data on what has been done out of what should be done during each evaluation period, meaning that 100% was what should be done in 3-month time in our project. This question, however, was slightly confusing at the beginning, as it was interpreted as percentage of all tasks and activities planned for the whole duration of the project. Additionally, this question only works provided that precise, clear plans on the type and timing of tasks were allocated to the project partners. Lastly, there were some questions with very low variability in answer types across evaluation surveys (mainly about coordination and communication). Our opinion is that if the project runs/performs in a smooth manner, one may think such questions useless, but in more complicated projects, these questions may reveal potential causes of troubles.

5. Conclusions

The PATHWAYS project experience shows a need for the implementation of structured evaluation processes in multidisciplinary projects involving different stakeholders in diverse socio-environmental and political conditions. Based on the PATHWAYS experience, a clear monitoring methodology is suggested as essential in every project and we suggest the following steps while doing multidisciplinary research:

Define area/s of interest (decision maker level/s; providers; beneficiaries: direct, indirect),

Identify 2–3 possible partners for each area (chain sampling easier, more knowledge about; check for publications),

Prepare a research plan (propose, ask for supportive information, clarify, negotiate),

Create a cross-partner groups of experts,

Prepare a communication strategy (communication channels, responsible individuals, timing),

Prepare a glossary covering all the important issues covered by the research project,

Monitor the project process and timing, identify concerns, troubles, causes of delays,

Prepare for the next steps in advance, inform project partners about the upcoming activities,

Summarize, show good practices, successful strategies (during project realization, to achieve better project performance).

Acknowledgments

The current study was part of the PATHWAYS project, that has received funding from the European Union’s Health Program (2014–2020) Grant agreement no. 663474.

The evaluation questionnaire developed for the PATHWAYS Project.

SWOT analysis:

What are strengths and weaknesses of the project? (list, please)

What are threats and opportunities? (list, please)

Visual SWOT:

Please, rate the project on the following continua:

How would you rate:

strengths of the project?

(no strengths) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (a lot of strengths, very strong)

weaknesses of the project?

(no weaknesses) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (a lot of weaknesses, very weak)

risk of threats to the project?

(no risks) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (several risks, inability to accomplish the task(s))

project opportunities

(no opportunities) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (project has a lot of opportunities)

Author Contributions

A.G., A.P., B.T.-A. and M.L. conceived and designed the concept; A.G., A.P., B.T.-A. finalized evaluation questionnaire and participated in data collection; A.G. analyzed the data; all authors contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors agreed on the content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- 1. Butler L. Modifying publication practices in response to funding formulas. Res. Eval. 2003;12:39–46. doi: 10.3152/147154403781776780. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Geuna A., Martin B.R. University Research Evaluation and Funding: An International Comparison. Minerva. 2003;41:277–304. doi: 10.1023/B:MINE.0000005155.70870.bd. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Arnold E. Evaluating research and innovation policy: A systems world needs systems evaluations. Res. Eval. 2004;13:3–17. doi: 10.3152/147154404781776509. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Porter A.L., Roessner J.D., Cohen A.S., Perreault M. Interdisciplinary research: Meaning, metrics and nurture. Res. Eval. 2006;15:187–196. doi: 10.3152/147154406781775841. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Barker K. The UK Research Assessment Exercise: The evolution of a national research evaluation system. Res. Eval. 2007;16:3–12. doi: 10.3152/095820207X190674. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Samson D., Terziovski M. The relationship between total quality management practices and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 1999;17:393–409. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00046-1. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Linnan L., Steckler A., editors. Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2002. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research: An Overview.24p [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Baranowski T., Stables G. Process Evaluations of the 5-a-Day Projects. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:157–166. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700202. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Cambridge English Dictionary: Meanings and Definitions. [(accessed on 26 April 2018)]; Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/

- 10. Evaluation | Definition of Evaluation in English by Oxford Dictionaries. [(accessed on 26 April 2018)]; Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/evaluation .

- 11. Stufflebeam D.L. Evaluation Model. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2001. American Evaluation Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Hill T., Westbrook R. SWOT analysis: It’s time for a product recall. Long Range Plan. 1997;30:46–52. doi: 10.1016/S0024-6301(96)00095-7. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Bull J.W., Jobstvogt N., Böhnke-Henrichs A., Mascarenhas A., Sitas N., Baulcomb C., Lambini C.K., Rawlins M., Baral H., Zähringer J., et al. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats: A SWOT analysis of the ecosystem services framework. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016;17:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.012. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Chermack T.J., Kasshanna B.K. The Use and Misuse of SWOT Analysis and Implications for HRD Professionals. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2007;10:383–399. doi: 10.1080/13678860701718760. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Thompson J.L. Strategic Management: Awareness and Change. Chapman & Hall University and Professional Division; Eugene, OR, USA: 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.7 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to undertake a research project and write a scientific paper

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Honorary Reader in Surgery, University of East Anglia, Norwich Research Park, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK E: [email protected]

Accepted 2012 Feb 14.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Research and publishing are essential aspects of lifelong learning in a surgical career. Many surgeons, especially those in training, ask for guidance on how they might start a simple project that may lead to a publication. This short paper offers some practical guidelines on the subject.

Keywords: Research Techniques, Research Activities, Publications, Journal Article

How to get started with a project

How to get started varies depending on whether the project is suggested by a trainer or educational supervisor. Projects suggested by a senior are always offered as an encouragement to a trainee, who should be careful not to respond in a negative way by ignoring the suggestion, coming up with a string of excuses or doing the project badly! Here are some simple steps that may contribute to an organised start on the project. You need a protocol but first you must be clear about what the project will involve.

Undertake a literature search on the suggested topic.

Read all the papers from the last ten years and summarise them on a single page of A4.

Make a note of how many similar series have been produced, their size, the length of follow-up and any special aspects of the subject that have already been addressed.

List aspects of the topic that have not been well covered, perhaps morbidity or surgery for rare indications, or long-term outcomes.

Discuss your thoughts on the subject with your colleagues.

With the strengths and weaknesses of the current literature clear in your own mind, summarise your thoughts in bullet points on a single side of A4 and arrange ten minutes to discuss them with the senior who suggested the topic.

The six steps listed above can be easily completed within a couple of weeks. Once you have discussed and agreed the aims of the project as well as how they can be achieved, you can write your protocol. It is also possible that having studied the literature you decide the suggested project is unlikely to add to our current knowledge and that another topic might be better studied.

A protocol and approval from your trust’s research and development (R&D) department as well as from the research ethics committee (REC) are needed before you begin a research project. If you are planning a service evaluation, REC approval may not be needed. When you have secured the approvals, the process of collecting the data begins.

Examining a case series, there may be hundreds of medical records that need to be studied and it is crucial to draw up a ‘proforma’ on which to record patient data. This should ideally fill no more than one or two sides of A4 and needs to include all the data that you have decided to collect for your particular study. It is crucial not to leave out a dataset you might later wish to look at but on the other hand it is also important not to collect too many data. Because of this fine balance, it is important to draw up a proforma and agree its composition with your supervisor and any co-workers on the project before starting to collect data from the medical records.

Data collection can be time consuming and it may be that several colleagues can work on this to speed the project along. Once all the data proformas are filled in, the data need to be entered into the database, spreadsheet or statistical package of your choice. It is best to use the software favoured by the department or colleagues in medical statistics.

Having looked at the data, discipline yourself to produce a succinct summary on one side of A4. Again, arrange a meeting with your supervisor and any other co-workers to discuss the findings, and give everyone the opportunity to comment and correct the summary. Once the findings are agreed, you are ready to write up the project.

Self-generated projects

Sometimes you will want to develop an idea of your own. It is even more important with a self-generated project to do a thorough literature search to make sure that your ideas will contribute to our knowledge. The discussion of a more ambitious project like a randomised trial should be with as many colleagues as possible, both for advice and also to garner support for your idea. Having produced a single side of A4 summarising your idea, identify a senior colleague who can advise you and proceed as described above.

As noted previously, REC approval is needed for any clinical research involving patients or their data. You will need to prepare an application on the Integrated Research Application System website ( https://www.myresearchproject.org.uk/ ). If you have never done this before, seek advice from your trust’s R&D department. REC approval is time consuming; the following comments may help:

Much of your initial work producing a summary of your idea will be helpful in completing the ethics committee form. It is crucial that submission to your local ethics committee is checked by all your co-workers.

Colleagues from medical statistics and any other parallel disciplines such as radiology or medical chemistry need to be involved right at the start of this formal submission so that all aspects of the study are academically correct. It is especially important to have expert statistical input because it is very demoralising to finish a trial only to be told that your study is woefully underpowered and cannot answer the question that it set out to address!

It is wise to present your idea to the committee in person as this can save time and iron out minor misunderstandings. These ‘glitches’ in an ethics submission can soak up months of precious time and a personal meeting with the REC can help to avoid them.

Many institutions also have research governance or internal review boards that must also pass a project after it has gained ethical approval. Their role is often to assess the financial and organisational impact of a study.

This process seldom takes less than 3 months and may take nearly 12 months. Do not be disheartened by this. If your study is worth doing, then it is worth persevering.

The recording of data using a concise proforma, entry into appropriate computer software and production of a summary of your findings are all conducted in the same way as in the first section of these guidelines.

Writing up a study

One of the most challenging aspects of surgical research is writing a paper. Putting together a manuscript for submission to a journal can be broken down into several simple and relatively self-contained steps:

Journal guidelines : All journals have a set of instructions for potential authors. The suggestions below are an overall guide to writing a paper but should be viewed in the context of the specific guidelines on submission to the journal you have chosen for your work.

Title : Keep this simple and concise.

Authorship : This topic may be a source of some problems. My own observation about authorship is that if you leave somebody out who feels they have contributed to your project, you can make an enemy for life! It is easy to forget colleagues, especially when a project has run for several years. Try, within the internationally agreed authorship guidelines, to include all colleagues who have contributed significantly to your study.

The order of authorship may also cause problems. It is generally agreed that the main researcher who also produced the first draft of the paper is the first author. The second author has usually been the second main contributor to the project. The last author is the senior person supervising the work. Between these positions come all other authors who fulfil the guidelines for authorship. If in any doubt about who should or should not be in the authorship, discuss it with your senior author.

All papers have a corresponding author responsible for answering queries after submission of the manuscript. It is best if he or she is a permanent member of the department as queries may arrive several years after a paper is published.

Abstract : This is usually 200–250 words and should be written in the style of the journal. Generally, this includes sections on background, methods, results and conclusions.

Introduction : This should introduce the reader to the subject covered in the study and explain why this particular study has been undertaken. It should be kept to two or three paragraphs. The first paragraph sets the scene and summarises the current literature. The second paragraph should justify why this particular study or series of cases has been put together.

Patients and methods : The most frequent mistake in this section is to include results as well as patient details. It is important to stick to describing the study population, how they were collected and, crucially, how any analyses were undertaken. Always describe what statistical tests were used and justify why they were appropriate.

Results : These should be presented concisely with as few tables or figures as possible. Use a logical sequence and follow the same sequence in the methods and discussion sections.

- What are the main findings of your work? State clearly what you can conclude from your observations, taking care not to overestimate what you can conclude.

- Why are these findings valid (sample size, methods etc)? Explain what leads you to conclude that your findings may be relied on. Also make sure you highlight any potential weaknesses in your data and consider other potential confounding variables that might invalidate your conclusions.

- How do your observations compare with other work in the same area? Discuss how results from your work compare with other papers on the same subject, either explaining similarities or examining differences.

- Any other business? Are there any unexpected side observations that merit separate discussion? This might include unexpected complications in a trial or a unique subset of patients in a clinical series.

- Restate your main findings and suggest what further work might be helpful in providing more information on the topic of your project.

References : Make sure these are presented in the style of the journal you have selected.

Publication of the paper

This can be the biggest hurdle you have to clear! Some basic rules will help to make this easier. First, never submit a paper without all authors having read it and agreed to the content. Second, never submit a paper to more than one journal at a time. Finally, remember that submission is not the end of your paper but just the beginning.

Selection of the right journal is important. On the basis of their impact factor, journals may be divided into four divisions. Think of it like the football league! The premier division contains journals with impact factors greater than 10, the second division those with impact factors from 5 to 10, the third division with impact factors from 1 to 5 and, finally, the fourth division with impact factors less than 1. Just as with football, journals may be promoted or relegated so it is wise to check online for a journal’s current impact factor.

Discuss with your co-workers what your target journal should be. It is acceptable to aim just higher than you think your paper ranks but obviously pointless sending a small case series to one of the premiership journals. A second consideration is which articles have appeared in your target journal over the last 12 months. If there have been one or more papers on the same subject as your work, it may be better to select an equally ranked journal that has not had a paper on your topic for several years.

Peer review is the process used by journals to select papers for publication. Many papers are rejected immediately but those deemed of potential interest are sent out for peer review. This process usually takes 3–4 months (although some journals such as the Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England have a much quicker turnaround). There are four potential outcomes:

Accept without corrections – this is very rare!

Minor corrections needed followed by resubmission for publication

Major corrections needed and resubmission invited but without any promise to publish

Major criticisms and rejection (for most major journals this is the single largest category of outcomes)

When you receive the reviewer’s comments don’t take them personally! The best way to regard the reviewer’s criticisms is as helpful suggestions to improve your paper. It is crucial to deal with each of the reviewer’s comments carefully, systematically and politely. If possible, respond to the comments within a few days of receiving them.

If your paper has been rejected, then the reviewer’s comments are an excellent set of suggestions to improve the manuscript for submission to another journal. This should probably be in one division lower than your first submission. Again, there is no reason to delay resubmission to another journal more than a few days. Make sure that all possible advice on rewriting and correcting your paper is taken and your work will almost certainly get published eventually!

- View on publisher site

- PDF (187.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Through this concise resource, we believe novice qualitative researchers will be able to scope and frame their qualitative research projects correctly and ensure increased rigor and credibility in their work.

Incorporating a research component along with a sound academic foundation enables students to develop independent critical thinking ... Developing and maintaining undergraduate research programs benefits students, faculty mentors, and the university.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations. [4]

A research proposal aims to show why your project is worthwhile. It should explain the context, objectives, and methods of your research.

Scholarly articles are articles written by experts and researchers in a field of study to educate or share new discoveries and research. You can use scholarly articles to find out about new innovations, research methodologies, and to dive more deeply into understanding the themes and subtopics of your field of research.

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR. Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals. Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

The evaluation process allowed to highlight strengths and weaknesses and highlighted good coordination and communication between project partners as well as some key issues such as: the need for a shared glossary covering areas investigated by the project, problematic issues related to the involvement of stakeholders from outside the project, an...

Abstract. Research and publishing are essential aspects of lifelong learning in a surgical career. Many surgeons, especially those in training, ask for guidance on how they might start a simple project that may lead to a publication. This short paper offers some practical guidelines on the subject.

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review. They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic. There are five key steps to writing a literature review: