You have come to the right place if you are looking for more information about the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). This site is created for individuals considering using the CFIR to evaluate an implementation or design an implementation study.

The CFIR was originally published in 2009 and was updated in 2022 based on user feedback. It will be helpful for new users to read the 2009 article first; specifically Background, Methods, and Overview of the CFIR. Then read the 2022 Updated CFIR article.

This site is under construction. We are working on changing content on this site to reflect the updated CFIR. Please be patient while this is in process.

Supported Web Browsers: Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Safari

The CFIR provides a menu of constructs arranged across 5 domains that can be used in a range of applications. It is a practical framework to help guide systematic assessment of potential barriers and facilitators. Knowing this information can help guide tailoring of implementation strategies and needed adaptations, and/or to explain outcomes.

The Updated CFIR builds on the 2009 version that included constructs from a range of 19 frameworks or related theories including Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory and Greenhalgh and colleagues’ compilation based on their review of 500 published sources across 13 scientific disciplines. The CFIR considered the spectrum of construct terminology and definitions and compiled them into one organizing framework.

The 2022 Updated CFIR draws on more recent literature and feedback from users. As part of the update process, a CFIR Outcomes Addendum was published to establish conceptual distinctions between implementation and innovation outcomes and their potential determinants.

The CFIR was developed by implementation researchers affiliated with the Veterans Affairs (VA) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

By providing a framework of constructs, the CFIR promotes consistent use of constructs, systematic analysis, and organization of findings from implementation studies. User must, however, critique the framework and publish recommendations to improve. This reciprocity is at the heart of building valid and useful theory. See Kislov et al’s call for researchers to engage in theoretically informative implementation research.

- “…while the CFIR’s utility as a framework to guide empirical research is not fully established, it is consistent with the vast majority of frameworks and conceptual models in dissemination and implementation research in its emphasis of multilevel ecological factors… Examining research (and real-world implementation efforts) through the lens of the CFIR gives us some indication of how comprehensively strategies address important aspects of implementation.”

The CFIR has most often been used within healthcare settings but has also been used across a diverse array of setting including low-income contexts and farming .

As of November 2023, the 2009 article was cited over 10,000 times in Google Scholar and over 4600 times in PubMed .

Research Update

+1 (646) 685-4341

Research Update Organization

Create new knowledge : learn, present, and publish.

Clinical Research Education

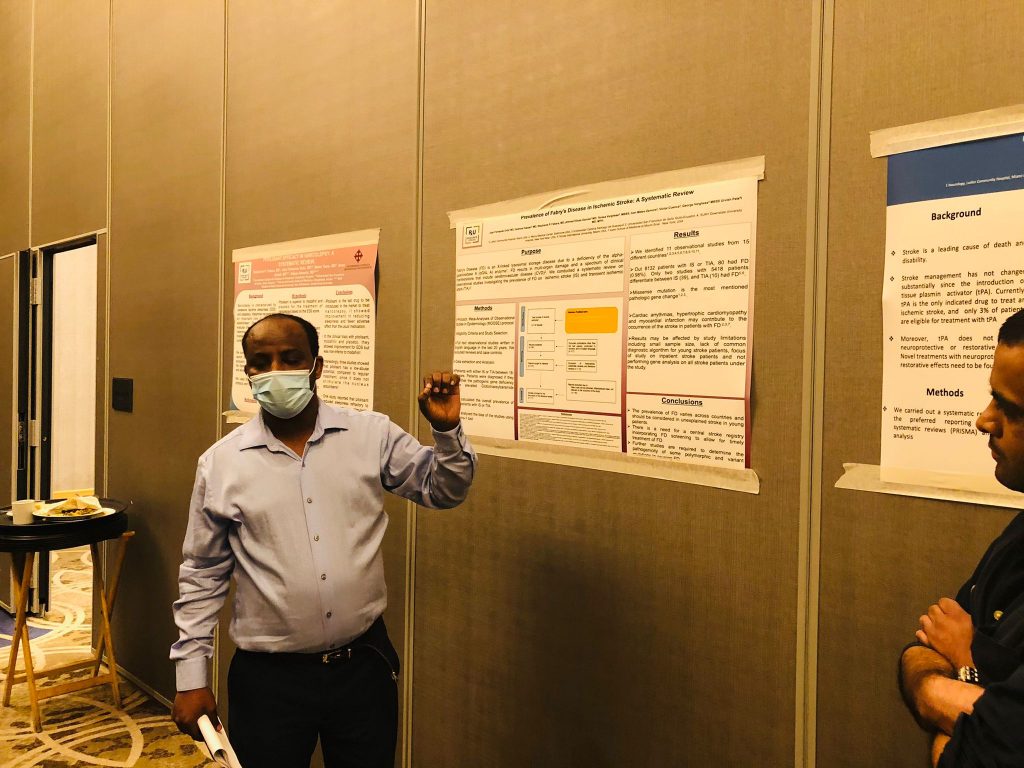

Clinical research training programs, clinical research consultation & support, evidence-based public health awareness, our recently published articles, elevated cardiac troponin i as a predictor of outcomes in covid-19 hospitalizations: a meta-analysis, prevalence and outcomes associated with vitamin d deficiency among indexed hospitalizations with cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disorder—a nationwide study, chronic periodontitis is associated with cerebral atherosclerosis –a nationwide study, intracerebral hemorrhage outcomes in patients using direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin k antagonists: a meta-analysis, liver disease and outcomes among covid-19 hospitalized patients – a systematic review and meta-analysis, early epidemiological indicators, outcomes, and interventions of covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review, an objective histopathological scoring system for placental pathology in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, age-adjusted risk factors associated with mortality and mechanical ventilation utilization amongst covid-19 hospitalizations—a systematic review and meta-analysis authors, biomarkers and outcomes of covid-19 hospitalisations: systematic review and meta-analysis, a rare case of round cell sarcoma with cic-dux4 mutation mimicking a phlegmon: review of literature, sex and racial disparity in utilization and outcomes of t-pa and thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke, is there a smoker’s paradox in covid-19, our philosophy.

Urvish Patel, MD, MPH

Founder, director, and chief education officer, “to advance the knowledge medicine and clinical research by breaking down the research process into a simple yet effective framework that is easy to follow. research update provides the necessary resources so that anyone can execute impactful and empirical research in a timely manner.”.

What People Say About Us

Kulin Patel, MBBS “I got the opportunity to learn research from the Research Update team, I enjoyed working with them. This experience is helping me to envision clinical research during residency…” Google Scholar || Project

Shivani Sharma, MD, BS “I am PGY1 FM Resident. I enjoyed working with the Research Update team. My research mentor- Urvish and his team had supported my research work throughout my journey to residency. Thank you, RxU” Google Scholar || Project

Arsalan Anwar, MBBS “ Dr. Patel has indeed invested his heart and soul in Research Update. He has helped us in fulfilling our goal of becoming an independent clinical researcher. The telegram group discussion also helped me be persistent in my goals. I highly recommend the Research update. …” Google Scholar || Project

Sidra Saleem , MBBS “I want to thank the Research Update team for their invaluable help. They have guided and supported me. One of the projects that I worked on was a headache. It was a smooth and enriching experience working with the team.” Google Scholar || Project

Deep Mehta, MBBS “I worked on an interesting research paper with the team. Learning various softwares like SPSS and RevMan has helped me become an independent researcher. I recommend everyone to join Research Update for excellent guidance in clinical research.” Google Scholar || Project

Dhaivat Shah, MBBS “Research Update helped me gain tremendous research experience. The telegram group discussions were very insightful. Dr. Patel helped me navigate through my MSCR course and has been a guiding torch for me. I highly recommend Research update to every student who is keen to learn Clinical Research.” Google Scholar || Project

About Research Update Organization

Research update organization [irs 501(c)(3) registered-tax-exempt, ein# 83-3619272] is a non-profit educational organization, founded to promote clinical research and its application to enrich community health. founding principles (1) clinical research education & training (2) clinical research consultation & support (3) utilization of clinical research for evidence-based public health awareness.

Volume 10 Supplement 1

7th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health

- Meeting abstract

- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2015

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): progress to date, tools and resources, and plans for the future

- Laura Damschroder 1 ,

- Carmen Hall 2 ,

- Leah Gillon 1 ,

- Caitlin Reardon 1 ,

- Caitlin Kelley 1 ,

- Jordan Sparks 1 &

- Julie Lowery 1

Implementation Science volume 10 , Article number: A12 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

9255 Accesses

48 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

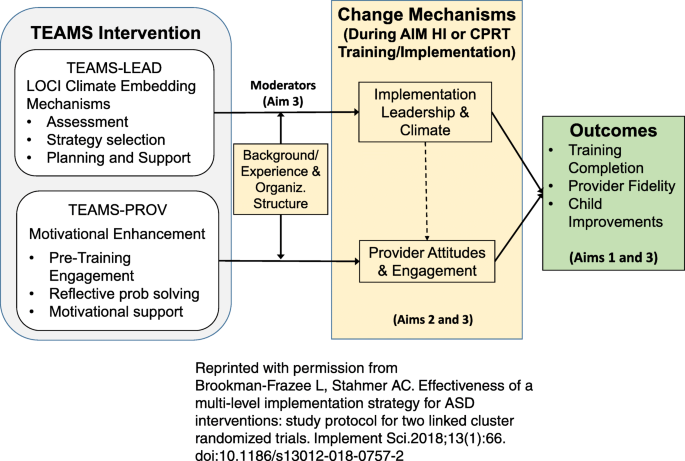

The objective of this presentation is to introduce the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), present results of a literature synthesis of studies citing the CFIR, highlight improvements expected in a second version of the framework, and present tools and resources available for researchers using the CFIR that will be available on a newly revamped website.

In a series of four interactive virtual panels, we elicited user feedback from implementation research novices and experts on needed CFIR tools. In addition, we searched multiple databases to identify articles that cited the CFIR. Articles were characterized as original research, syntheses, study protocols, or general background references.

347 published articles cited the CFIR, with an average of growth rate of four additional articles per week; fifty-one were original research, protocols, or syntheses. Recommendations were extracted from these articles and used to inform updates for CFIR V2. Refinements will include improved clarity in definitions for existing constructs, addition of new constructs, and better framing of the purpose and uses of CFIR. The CFIR website was significantly redesigned with the addition of new tools and resources including: 1) an interview guide creation tool; 2) links to a periodically updated bibliography of articles applying the CFIR; 3) two published quantitative measures related to organizational change mapped to CFIR constructs; 4) in-depth guidance on how to apply the CFIR; and 5) plans for the future. A demonstration of the publically available website will be provided along with the URL.

Advances for D&I

The CFIR brings clarity to commonly studied constructs by suggesting clear and consistent terms and definitions that can be applied across diverse settings, within and outside healthcare. Use of the CFIR is growing. CFIR V2 along with tools, resources, and published applications, will help researchers collectively advance the science of implementation.

Department of Veteran Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (Grant # RRP 12-494).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Clinical Management Research, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Laura Damschroder, Leah Gillon, Caitlin Reardon, Caitlin Kelley, Jordan Sparks & Julie Lowery

Gusek Hall Consulting, Roseville, MN, 55113, USA

Carmen Hall

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Damschroder, L., Hall, C., Gillon, L. et al. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): progress to date, tools and resources, and plans for the future. Implementation Sci 10 (Suppl 1), A12 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-10-S1-A12

Download citation

Published : 14 August 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-10-S1-A12

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Veteran Affair

- Health Service Research

- Implementation Research

- User Feedback

- Quality Enhancement

Implementation Science

ISSN: 1748-5908

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

How to Use a Conceptual Framework for Better Research

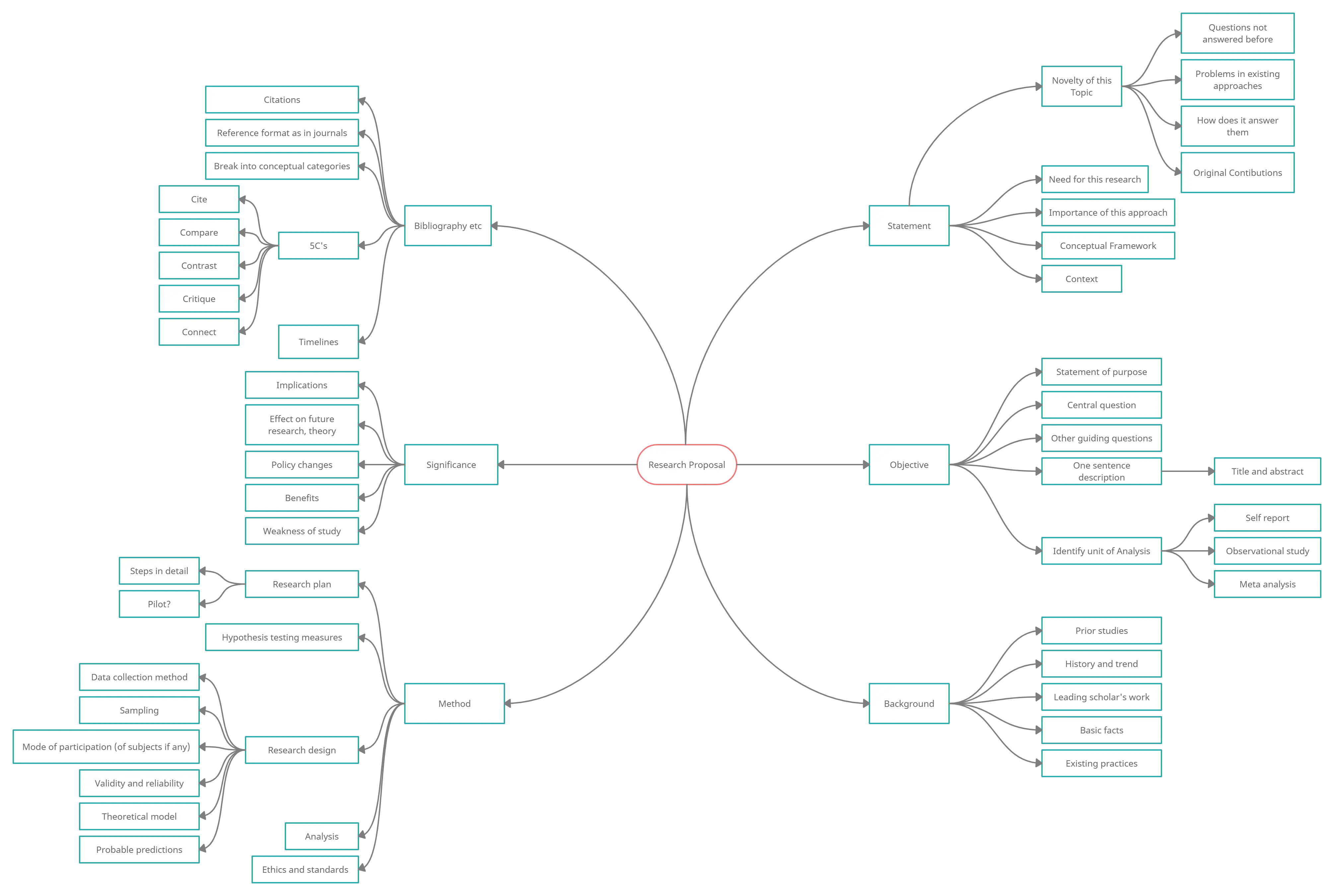

A conceptual framework in research is not just a tool but a vital roadmap that guides the entire research process. It integrates various theories, assumptions, and beliefs to provide a structured approach to research. By defining a conceptual framework, researchers can focus their inquiries and clarify their hypotheses, leading to more effective and meaningful research outcomes.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework is essentially an analytical tool that combines concepts and sets them within an appropriate theoretical structure. It serves as a lens through which researchers view the complexities of the real world. The importance of a conceptual framework lies in its ability to serve as a guide, helping researchers to not only visualize but also systematically approach their study.

Key Components and to be Analyzed During Research

- Theories: These are the underlying principles that guide the hypotheses and assumptions of the research.

- Assumptions: These are the accepted truths that are not tested within the scope of the research but are essential for framing the study.

- Beliefs: These often reflect the subjective viewpoints that may influence the interpretation of data.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Together, these components help to define the conceptual framework that directs the research towards its ultimate goal. This structured approach not only improves clarity but also enhances the validity and reliability of the research outcomes. By using a conceptual framework, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and focus on essential variables and relationships.

For practical examples and to see how different frameworks can be applied in various research scenarios, you can Explore Conceptual Framework Examples .

Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks Used in Research

Understanding the various types of conceptual frameworks is crucial for researchers aiming to align their studies with the most effective structure. Conceptual frameworks in research vary primarily between theoretical and operational frameworks, each serving distinct purposes and suiting different research methodologies.

Theoretical vs Operational Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are built upon existing theories and literature, providing a broad and abstract understanding of the research topic. They help in forming the basis of the study by linking the research to already established scholarly works. On the other hand, operational frameworks are more practical, focusing on how the study’s theories will be tested through specific procedures and variables.

- Theoretical frameworks are ideal for exploratory studies and can help in understanding complex phenomena.

- Operational frameworks suit studies requiring precise measurement and data analysis.

Choosing the Right Framework

Selecting the appropriate conceptual framework is pivotal for the success of a research project. It involves matching the research questions with the framework that best addresses the methodological needs of the study. For instance, a theoretical framework might be chosen for studies that aim to generate new theories, while an operational framework would be better suited for testing specific hypotheses.

Benefits of choosing the right framework include enhanced clarity, better alignment with research goals, and improved validity of research outcomes. Tools like Table Chart Maker can be instrumental in visually comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different frameworks, aiding in this crucial decision-making process.

Real-World Examples of Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Understanding the practical application of conceptual frameworks in research can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your studies. Here, we explore several real-world case studies that demonstrate the pivotal role of conceptual frameworks in achieving robust research conclusions.

- Healthcare Research: In a study examining the impact of lifestyle choices on chronic diseases, researchers used a conceptual framework to link dietary habits, exercise, and genetic predispositions. This framework helped in identifying key variables and their interrelations, leading to more targeted interventions.

- Educational Development: Educational theorists often employ conceptual frameworks to explore the dynamics between teaching methods and student learning outcomes. One notable study mapped out the influences of digital tools on learning engagement, providing insights that shaped educational policies.

- Environmental Policy: Conceptual frameworks have been crucial in environmental research, particularly in studies on climate change adaptation. By framing the relationships between human activity, ecological changes, and policy responses, researchers have been able to propose more effective sustainability strategies.

Adapting conceptual frameworks based on evolving research data is also critical. As new information becomes available, it’s essential to revisit and adjust the framework to maintain its relevance and accuracy, ensuring that the research remains aligned with real-world conditions.

For those looking to visualize and better comprehend their research frameworks, Graphic Organizers for Conceptual Frameworks can be an invaluable tool. These organizers help in structuring and presenting research findings clearly, enhancing both the process and the presentation of your research.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Own Conceptual Framework

Creating a conceptual framework is a critical step in structuring your research to ensure clarity and focus. This guide will walk you through the process of building a robust framework, from identifying key concepts to refining your approach as your research evolves.

Building Blocks of a Conceptual Framework

- Identify and Define Main Concepts and Variables: Start by clearly identifying the main concepts, variables, and their relationships that will form the basis of your research. This could include defining key terms and establishing the scope of your study.

- Develop a Hypothesis or Primary Research Question: Formulate a central hypothesis or question that guides the direction of your research. This will serve as the foundation upon which your conceptual framework is built.

- Link Theories and Concepts Logically: Connect your identified concepts and variables with existing theories to create a coherent structure. This logical linking helps in forming a strong theoretical base for your research.

Visualizing and Refining Your Framework

Using visual tools can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your conceptual framework. Decision Tree Templates for Conceptual Frameworks can be particularly useful in mapping out the relationships between variables and hypotheses.

Map Your Framework: Utilize tools like Creately’s visual canvas to diagram your framework. This visual representation helps in identifying gaps or overlaps in your framework and provides a clear overview of your research structure.

Analyze and Refine: As your research progresses, continuously evaluate and refine your framework. Adjustments may be necessary as new data comes to light or as initial assumptions are challenged.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your conceptual framework is not only well-defined but also adaptable to the changing dynamics of your research.

Practical Tips for Utilizing Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Effectively utilizing a conceptual framework in research not only streamlines the process but also enhances the clarity and coherence of your findings. Here are some practical tips to maximize the use of conceptual frameworks in your research endeavors.

- Setting Clear Research Goals: Begin by defining precise objectives that are aligned with your research questions. This clarity will guide your entire research process, ensuring that every step you take is purposeful and directly contributes to your overall study aims. \

- Maintaining Focus and Coherence: Throughout the research, consistently refer back to your conceptual framework to maintain focus. This will help in keeping your research aligned with the initial goals and prevent deviations that could dilute the effectiveness of your findings.

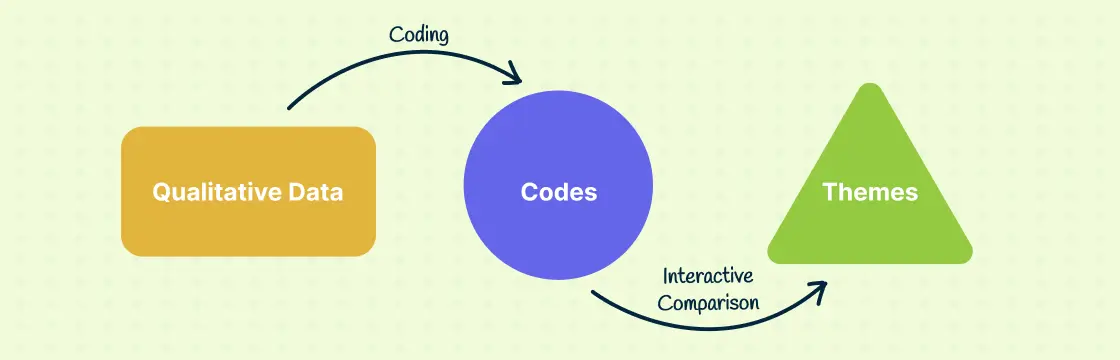

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Use your conceptual framework as a lens through which to view and interpret data. This approach ensures that the data analysis is not only systematic but also meaningful in the context of your research objectives. For more insights, explore Research Data Analysis Methods .

- Presenting Research Findings: When it comes time to present your findings, structure your presentation around the conceptual framework . This will help your audience understand the logical flow of your research and how each part contributes to the whole.

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls: Be vigilant about common errors such as overcomplicating the framework or misaligning the research methods with the framework’s structure. Keeping it simple and aligned ensures that the framework effectively supports your research.

By adhering to these tips and utilizing tools like 7 Essential Visual Tools for Social Work Assessment , researchers can ensure that their conceptual frameworks are not only robust but also practically applicable in their studies.

How Creately Enhances the Creation and Use of Conceptual Frameworks

Creating a robust conceptual framework is pivotal for effective research, and Creately’s suite of visual tools offers unparalleled support in this endeavor. By leveraging Creately’s features, researchers can visualize, organize, and analyze their research frameworks more efficiently.

- Visual Mapping of Research Plans: Creately’s infinite visual canvas allows researchers to map out their entire research plan visually. This helps in understanding the complex relationships between different research variables and theories, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of the research process.

- Brainstorming with Mind Maps: Using Mind Mapping Software , researchers can generate and organize ideas dynamically. Creately’s intelligent formatting helps in brainstorming sessions, making it easier to explore multiple topics or delve deeply into specific concepts.

- Centralized Data Management: Creately enables the importation of data from multiple sources, which can be integrated into the visual research framework. This centralization aids in maintaining a cohesive and comprehensive overview of all research elements, ensuring that no critical information is overlooked.

- Communication and Collaboration: The platform supports real-time collaboration, allowing teams to work together seamlessly, regardless of their physical location. This feature is crucial for research teams spread across different geographies, facilitating effective communication and iterative feedback throughout the research process.

Moreover, the ability t Explore Conceptual Framework Examples directly within Creately inspires researchers by providing practical templates and examples that can be customized to suit specific research needs. This not only saves time but also enhances the quality of the conceptual framework developed.

In conclusion, Creately’s tools for creating and managing conceptual frameworks are indispensable for researchers aiming to achieve clear, structured, and impactful research outcomes.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Chiraag George is a communication specialist here at Creately. He is a marketing junkie that is fascinated by how brands occupy consumer mind space. A lover of all things tech, he writes a lot about the intersection of technology, branding and culture at large.

Search NORC

Enter Search Value

The Community-Engaged Research Framework

Anmol Sanghera

- Sabrina Avripas

- Ashani Johnson-Turbes

For inquiries, email:

Download Equity Brief

Print Version

This Equity Brief describes the Community-Engaged Research Framework and highlights strategies for applying the principles of the Framework in practice. The Framework consists of six principles, grounded in theory and practice, that inform community engagement. It serves as a conceptual model to guide researchers in authentically engaging community members and organizations in social and behavioral science research.

Introduction

This Equity Brief describes the Community-Engaged Research (CEnR) Framework, or “the Framework,” six principles for engaging communities throughout the full research process and strategies for applying the principles in practice. The Framework is grounded in theory and existing community engagement literature and frameworks (e.g., inclusive research, community-based participatory research, community-based participatory action research, community-directed research, emancipatory research). [1-6] It serves as a conceptual model for researchers and communities to use to authentically engage each other in social and behavioral science research.

Community-Engaged Research

Community-engaged research is an approach to inclusive and equitable research [i] that joins researchers with communities as partners throughout the full cycle of the research process. [1,5,7,8] Its emphasis is on the relationship between researchers and communities, not on the methodological approach to conduct the research; teams [ii] can use both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. [7,8] Community-engaged research may improve validity and relevance of data and results from the study, increase the data’s cultural relevance to community needs, enhance use of the data to create behavioral, social, services, or policy change, and increase the capacity of both communities and researchers. [7,8]

Exhibit 1: Continuum of Community Engagement in Research

Source: Adapted from the ATSDR Principles of Community Engagement and Wilder Involving Community Members in Evaluation: A Planning Framework

Community-engaged research exists along a continuum (Exhibit 1) that ranges in spectrum of community involvement from less (community as advisor) to more (community as equal partner or as leader) engagement. [1,5,7,8] Teams should strive to reach a level of shared leadership; however, time and resource constraints, historical mistrust, and competing priorities may make this level of engagement in every project difficult. [7-9]

The Community-Engaged Research Framework (Exhibit 2) consists of six principles for researcher and community partnerships to apply when engaging throughout the full research process. The inner circle displays the six principles essential to community engagement throughout each phase of the research process. The principles are not listed in any specific order and apply to all steps of the research process. These principles apply regardless of where a research study is on the continuum of community engagement. [1,7,8,10] The outer ring lists the phases of the research process, adapted from the Culturally Responsive Evaluation Framework, which centers both the theory and practice of “evaluation in culture” and ensures evaluation is responsive to values and beliefs. We have modified this evaluation framework to include the research process more broadly.

Exhibit 2: Community-Engaged Research Framework

© 2023 NORC. Source: Adapted from the Culturally Responsive Evaluation Framework and based on principles adapted from various frameworks for community-engaged research.

This section describes each principle and the actionable strategies teams can use to apply the principle throughout the research process. While we describe strategies within a specific principle, many are applicable across principles.

PRINCIPLE: AVOIDANCE OF HARM

All team members understand the immediate and broader implications of the research in context (e.g., community, society, systems) and actively avoid harming [iii] or marginalizing the communities in which the project is embedded. [5]

All team members recognize their own conscious and unconscious biases, how the research process can impact communities, and how the community and researchers benefit. [5,10-12] Avoidance of harm also requires listening to and respecting community expertise to better understand harm and strategies for avoidance. [5] Avoiding or doing no harm is especially important in research with historically and contemporarily marginalized and minoritized populations. [5,10]

Avoidance of harm prevents researchers from perpetuating a cycle of negative or exploitative interactions between communities and researchers, governments, and other systems, which has resulted in distrust among historically marginalized and minoritized communities. [5,8,9] It also helps teams develop appropriate protections to mitigate risks.

Actionable Strategies

Understand historical and contemporary contexts and their impact on community(ies). [5,10] Understanding communities’ context, needs, and sociopolitical environment is iterative; it requires remaining open, asking questions, conducting needs assessments, and stepping back when needed. [5,11]

- Define community and harm in partnership with communities, and understand key principles and trauma.4,5 Understand how aspects of racism and other systems of oppression influence study design, implementation, and dissemination, and adapt research processes and analysis to this context. [5,13]

- Critically deliberate on and pursue opportunities that address inequities due to race, ethnicity, class, caste, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, physical ability, and other social constructs. [4]

- Actively challenge systems of oppression and injustice, including those lingering in some research traditions, by improving coordination, enhancing existing services, and identifying, mobilizing, and strengthening assets and resources that enhance community’s capacity to make decisions.

Implement strategies to mitigate harm. Researchers’ actions may unknowingly or unintentionally harm communities.

- Develop in partnership with communities or use existing frameworks [iv] to mitigate harm if there are adverse effects of research actions.

- Prioritize the expertise of communities most affected by the harm when developing solutions to mitigate harms and challenges.

Maintain community-researcher relationships beyond one project or funding period. Allocate adequate resources to maintain relationships with communities over the long-term. Continually reflect, assess, and communicate to maintain and deepen relationships for long-term action and sustainability. Take part in community meetings and events, meet community leaders, and build and foster relationships.

PRINCIPLE: SHARED POWER AND EQUITY IN DECISION-MAKING

All team members participate collaboratively, equitably, and cooperatively in all decisions within each phase of the research process. [5,14]

Shared power and equity in decision-making ensures teams incorporate the experiences and needs of communities into every aspect of the research process, from conception to dissemination, and use of findings to inform policies, programs, and services. Teams establish a governance structure that includes the voices of communities directly impacted by the issue or topic they are researching and employ equitable structures of decision-making and contribution. [4-6,13,14] This approach helps overcome non-participatory governance structures that are researcher-led with little room for community input or involvement, which can result in research that does not address community needs or interests. [2,7]

Create a diverse and inclusive team. Include people with subject matter expertise and lived experiences to ensure the team reflects the community in which the project is embedded. Identify gaps in expertise and engage additional partners to fill gaps. [6]

Establish governance structures that eliminate Non-Participatory power hierarchies that de-value community experience and expertise.

- Create structures that promote equity and power sharing to overcome power differentials. Include avenues for shared decision-making (e.g., co-principal investigators, equal representation on steering committees). [4,5,13,14]

- Overcome relational dynamics that limit opportunities for economically and socially marginalized and disadvantaged groups that are part of project teams. Treat all team members with integrity and respect (e.g., do not undermine or invalidate people’s experiences, thoughts, or ideas; practice active listening; be considerate of others’ time, schedules, language, and cultural norms). [4,8,9]

Discuss up front what communities want to contribute and ultimately get from the research. Collectively establish parameters for data ownership and dissemination of findings. Be inclusive of communities’ right to access their collective data and research protocols by giving data and results back to the communities in which the research takes place. [6,14]

PRINCIPLE: TRANSPARENCY & OPEN COMMUNICATION

Researchers and community partners communicate openly and honestly about power dynamics and decision-making processes around project objectives and research processes, resources and finances, challenges and limitations, data, research findings, and dissemination strategies. [4,5,15]

Transparency and open communication require that all team members know who is involved in the study and why; the intent and purpose of a project; how resources are shared and allocated; and the apparent and hidden potential benefits, harms, and limitations of a project. [4,5]

Lack of transparency may result in lack of trust if communities feel like they are being taken advantage of or do not understand researchers’ motivations and intentions. [16-18] Transparency and open communication create more authentic working relationships, build trust, and help mend relationships between researchers and communities; build on avoidance of harm to reduce the risk of unintentionally harming communities; demonstrate integrity for working through difficult issues; and improves investment in the relationship to promote sustainability. [16-18]

Collaboratively establish open communication approaches and channels.

- Determine methods, cadence, and mode of communication and meeting coordination.

- Set schedules, establish points of contacts and preferred formats for communication, and set timelines and frequencies of communication.

Minimize hierarchy in communication processes, “gatekeepers,” and barriers to lines of communication. Share information readily with each member of the team about research processes and objectives, roles, motives, resources and finances, progress, timelines, etc. at every stage and at every level of the project. [4,5,17]

PRINCIPLE: MUTUAL ACCOUNTABILITY & RESPECT

Develop an equitable structure of incorporating input into decision-making processes, promoting commitment, and addressing discord directly.

Teams collaboratively define roles and decision-making authority, establishing a shared vision for the partnership and the research. [14,15] They also continually assess progress towards achieving that vision throughout the decision-making process. Teams facilitate discussions that allow for respectful discord and a process for reconciling discord in every phase of the research process. [4]

Non-participatory research that lacks mutual accountability and respect risks members losing interest and investment in the work, leading to a lack of respect for values and needs. Mutual accountability and respect promote a more equitable collaboration and continued involvement of members throughout all phases of the research. [19]

Collectively develop charters and establish ground rules.

- Develop partnership arrangements (e.g., memorandum of understanding) that document the scope and nature of the partnership and align scope with each member’s capacity. Determine where on the continuum of engagement the study and relationships lie and set expectations for that relationship early and often.

- Delineate responsibilities and expectations for each person on the team. [14,15] Set realistic commitments and provide opportunities to share progress towards those commitments. [19]

- Develop a vision statement for the work and a charter for upholding and making progress towards that vision. Revise the charter as needed. [20]

- Create and implement decision-making protocols to promote follow through and commitment to roles and responsibilities, ways to track progress on achieving the goals and vision of the partnership, and continually share lessons learned. [20]

Establish structures to overcome discord.

- Develop ground rules for reconciling discord. Make time and space for individuals to speak comfortably and express discord without fear.

- Acknowledge missteps, challenges, and limitations and work openly to address them. Be willing to adapt throughout the partnership and process. [5]

PRINCIPLE: ACCESSIBILITY & DEMONSTRATED VALUE

Value time and contributions of all team members and develop flexible and equitable methods of engagement. [5,13]

Teams demonstrate accessibility and demonstrated value through fair and equitable compensation, reasonable and thoughtful requests for time, and flexibility and accessibility in methods of engagement and communication. [5,15]

Non-participatory research may prioritize researcher views, perspectives, and methods of engagement. Participatory research recognizes that each team member brings their own unique perspectives and skills and adds valuable experiences, resources, and social networks to the research process. [19] It also considers each team member’s barriers to engagement and establishes approaches to overcome those barriers. Accessibility and demonstrated value promote greater acceptance of alternative perspectives and trust, inclusivity, and engagement.

Acknowledge all team members and value their expertise, skills, and contributions.

- Create a shared space that equally values all team members’ contributions and voices to facilitate co-design, co-creation, and shared decision-making, and to advance individual and collective development, growth, and learning. [15]

- Integrate opportunities for relationship-building activities, informal networking, team building, and engagement outside of project activities. [19]

- Ask how individuals and communities would like to be acknowledged and give credit for contributions. Create publication and data use guidelines.

- Collaboratively determine adequate compensation structures for all members’ contribution and time in their preferred method and form of value. [15]

Demonstrate cultural responsiveness [v] and inclusivity.

- Understand that engagement and relationship building take time. Allow sufficient time to establish relationships and account for the limited time some members have to engage in research.

- Practice cultural humility. [vi] Conduct self-reflection about your own biases, power, and privileges. [4,5,10] Ask questions and take time to understand local and cultural practices and nuances. [4,5]

- Understand and address barriers to engagement. Provide accessible modalities of participation and access, including flexibility in meeting times and location, interpreters and translated materials, plain language materials, childcare, transportation, and technology support. [15] Conduct engagements at times and in places convenient to communities. Offer disability accommodations and be flexible with requests for time commitment and deadlines. [5,15]

PRINCIPLE: CAPACITY BRIDGING & CO-LEARNING

All team members learn from each other and engage in bi-directional feedback and conversation. [vii]

Capacity bridging and co-learning expands tools, resources, skills, and knowledge among all team members. [21–23] It also promotes sustainability beyond one research project or funding opportunity. [23] Embedded throughout the research process are educational opportunities for all team members to become agents for community change. Teams should work together to re-define the research process and relationship, not to transform community partners into researchers (unless that is the ask of community partners). [15] Non-participatory research that focus solely on building the capacity of community members fall short in fostering bi-directional knowledge, skills, and capacity. Researchers should learn about historical and contemporary local culture and context, lived experiences of community partners, and community engagement strategies. [14]

Facilitate the reciprocal transfer of knowledge, skills, and capacity. [21,22] Maintain open dialogue, conduct and receive trainings, and bi-directionally share information, tools, and data. [14]

Translate knowledge into action. Document and share lessons learned about what works and what does not work about the process, and partnership successes, weaknesses, and challenges to further facilitate co-learning. [19] Understand how results from the study can improve programs, policies, or services to benefit both the advancement of science and the community. [19]

Affirm community strengths and assets. Conduct activities like community asset mapping and strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analyses, and practice positive marginality [viii] to understand each team member’s perspectives, knowledge, and expertise. Highlight and affirm community strengths. [4] Employ multiple methods and forums for community involvement beyond inclusion of community members on the project team (e.g., advisory boards, town halls, listening sessions, public comment).

The Community-Engaged Research Framework is a conceptual model that guides community engagement using the following six key principles: (1) Avoidance of harm; (2) Shared Power and Equity in Decision-Making; (3) Transparency and Open Communication; (4) Mutual Accountability and Respect; (5) Accessibility and Demonstrated Value; and (6) Capacity Bridging and Co-learning.

Applying these principles and their associated actionable strategies facilitates conduct of inclusive and equitable research and evaluation that centers people’s cultures and community. Community-engaged research will vary depending on the community, project, client, capacity, and available funding and resources. The Community-Engaged Research Framework is a model that teams can tailor as needed to their specific research, needs, context, and communities under inquiry. This Equity Brief shares NORC’s Community-Engaged Research Framework. A subsequent equity brief will discuss strategies for putting the framework into practice.

Download This Equity Brief

Acknowledgements.

This Community-Engaged Research Framework was made possible with funding from NORC’s Diversity, Racial Equity, and Inclusion (DREI) Research Innovation Fund. We thank the following:

- Work group members: Manal Sidi, Anna Schlissel, Chandria Jones, James Iveniuk, Jocelyn Wilder, and Stefan Vogler for their contributions to framework development.

- NORC reviewers: Roy Ahn, Michelle Johns, Carly Parry, and Vince Welch.

- External reviewers: Carmen Hughes, Health IT Division Director, National Center for Primary Care, Morehouse School of Medicine and Hager Shawkat, Program Director, Sauti Yetu Center for African Women.

[i] Inclusive & Equitable Research are “the methods of practice for Equity Science that is collaborative research embracing a range of theoretical frameworks and mixed methods that are focused on centering and empowering people and communities under inquiry and democratizing the research process to promote equity.” Johnson-Turbes, A., Jones, C., Johns, M.M., & Welch, V. (2022). Inclusive and Equitable Research Framework [Unpublished Manuscript]. Center on Equity Research, NORC at the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

[ii] A “team” consists of individuals, community-based organizations, researchers, evaluators, community leaders, and other key individuals or entities partners as determined by the project.

[iii] “Do No Harm,” a principle requiring healthcare providers to consider if the risk of their actions will hurt a patient versus improve a patient’s condition, is central to healthcare. Its origins trace back to the Hippocratic Oath and its development in the 1990s by Mary Anderson as an approach to working on conflict affected situations. The term is widely used (and sometimes, misused) to the design and conduct of research to ensure inclusivity and advance equity. In social science research, the interpretation of “do no harm” should also weigh the risk of harming an individual or potential benefits from data collection, analysis, or results dissemination. Like in medicine, the goal of research should be to advance equity and promote wellbeing, in line with beneficence. See Kinsinger FS. Beneficence and the professional’s moral imperative. J Chiropr Humanit. Published online 2009.

[iv] For example, Glover et al 2020’s Framework for Identifying and Mitigating the Equity Harms of COVID-19 Policy Interventions adapts the idea of “duty to warn” for research to inform communities about potential harm.

[v] Cultural responsiveness is the “ability to learn from and relate respectfully to people from your own and other cultures,” which promotes increased level of comfort, knowledge, freedom, capacity, and resources and knowledge. [23]

[vi] Cultural humility is the practice of self-evaluation and self-reflection to examine our own biases, acknowledgement and shift of power dynamics and imbalances, and accountability for one’s own actions as well as those of its organization or institution. [12]

[vii] Capacity building refers to building capacity, knowledge, and skills, of someone, usually a community person, to a research team. [21] Capacity bridging expands this notion to acknowledge that one person can bring many things to their position on a team. [21] It also acknowledges the reciprocity of knowledge sharing between academics, researchers, community-based researchers, and individuals—so that all members are learning from each other. [21] This term was coined by the AHA Centre.

[viii] Positive Marginality promotes the idea that injustice is rooted in structural determinants rather than personal or community behavior. It promotes the idea that “belonging to a non-dominant cultural or demographic group can be advantageous rather than oppressive.” [24]

[1] Wilder Foundation. Using a Framework for Community-Engaged Research. Published 2018. Accessed December 12, 2022.

[2] Nind M. What Is Inclusive Research. Bloomsbury Academic; 2014.

[3] International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. What Is Participatory Health Research? (PDF) ; 2013. Accessed January 1, 2024.

[4] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Engagement Framework (PDF) ; 2017. Accessed January 2, 2024.

[5] Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI), Michigan Health Endowment Fund. Community Engagement & Collective Impact Phase 1 Environmental Scan (PDF). Accessed January 2, 2024.

[6] Black Health Equity Working Group. A Data Governance Framework for Health Data Collected from Black Communities in Ontario. ; 2021. Accessed January 2, 2024.

[7] McDonald MA. Practicing Community-Engaged Research (PDF). Duke Center for Community Research. Published 2009. Accessed December 11, 2022.

[8] NIH Publication No. 11-7782. Principles of Community Engagement Second Edition (PDF) ; 2011. Accessed December 12, 2022.

[9] Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. ATSDR’s Community Engagement Playbook (PDF). Accessed January 1, 2024.

[10] Ross L, Brown J, Chambers J, et al. Key Practices for Community Engagement in Research on Mental Health or Substance Use (PDF). Accessed December 11, 2022.

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Practitioners Guide for Advancing Health Equity: Community Strategies for Preventing Chronic Disease (PDF) ; 2013. Accessed December 12, 2022.

[12] Hughes-Hassell S, Rawson CH, Hirsh K. Project READY: Reimagining Equity & Access for Diverse Youth, Module 8: Cultural Competence & Cultural Humility. University of North Carolina, Institute of Museum and Library Services. Accessed December 13, 2022.

[13] NORC. Community Engagement Panel: Community Engagement through Participatory Analysis.

[14] Wilder J, Agboola F, Vogler S, Rugg G, Iveniuk J. Chicago Community Alliance: Guidelines for Creating Community Engaged Research.; 2022.

[15] Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard T, Paez K, Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement (2013 inaugural panel). The PCORI Engagement Rubric: Promising Practices for Partnering in Research (PDF). Ann Fam Med. Published online 2017:165-170. Accessed February 14, 2024.

[16] Jamshidi E, Morasae EK, Shahandeh K, et al. Ethical Considerations of Community-based Participatory Research: Contextual Underpinnings for Developing Countries. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(10):1328-1336.

[17] Jones Mcmaughan D, Dolwick Grieb SM, Kteily-Hawa R, Key KD. Promoting and Advocating for Ethical Community Engagement: Transparency in the Community-Engaged Research Spectrum (PDF). Accessed February 6, 2024.

[18] Goodman LA, Thomas KA, Serrata JV, et al. Power through Partnerships: A CBPR Toolkit for Domestic Violence Researchers. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence ; 2017. Accessed February 6, 2024.

[19] Marquez E, Smith S, Tu T, Ayele S, Haboush-Deloye A,, Lucero J. A Step-by-Step Guide to Community-Based Participatory Research (PDF) ; 2022. Accessed February 6, 2024.

[20] Lo L, Aron LY, Pettit KLS, Scally CP. Mutual Accountability Is the Key to Equity-Oriented Systems Change How Initiatives Can Create Durable Shifts in Policies and Practices Background and Mutual Accountability Framework.; 2021.

[21] AHA Centre. Capacity Bridging Fact Sheet ; 2018.

[22] CDAC Network. The CDAC Capacity Bridging Initiative Facilitating Inclusion and Maximising Collaboration in CCE/AAP (PDF). Accessed February 6, 2024.

[23] Kozleski E, Harry B. Cultural, Social, and Historical Frameworks That Influence Teaching and Learning in U.S. Schools ; 2005.

[24] Streets VN. Reconceptualizing Women’s STEM Experiences: Building a Theory of Positive Marginality. Vol Dissertation ; 2016. Accessed December 13, 2022.

NORC at the University of Chicago conducts research and analysis that decision-makers trust. As a nonpartisan research organization and a pioneer in measuring and understanding the world, we have studied almost every aspect of the human experience and every major news event for more than eight decades. Today, we partner with government, corporate, and nonprofit clients around the world to provide the objectivity and expertise necessary to inform the critical decisions facing society.

Research Divisions

- NORC Health

Departments, Centers & Programs

- Center on Equity Research

- Petry S. Ubri

- Health Equity

Want to work with us?

Explore NORC Health Projects

Reproductive health experiences & access.

Tracking reproductive health experiences and access in the U.S.

Health Communication AI

Combining the trust-building ability of digital opinion leaders with the scalability of AI to revolutionize health communication

Positive Adolescent Interpersonal Relationships (PAIR)

Expanding NORC’s STRiV research to reflect diverse adolescent experiences and communities

Processes for updating guidelines: protocol for a systematic review

Karen Cardwell Roles: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation Joan Quigley Roles: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Barbara Clyne Roles: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Barrie Tyner Roles: Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Marie Carrigan Roles: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing Susan Smith Roles: Writing – Review & Editing Máirín Ryan Roles: Writing – Review & Editing Michelle O'Neill Roles: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing

Systematic review, guideline methodology, guideline update, prioritization methodology.

Abbreviations

CG, Clinical guideline; CIMO, Context, intervention, mechanism, outcome; GIN, Guidelines International Network; NCG, National Clinical Guideline; PRISMA-P, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols.

Introduction

In Ireland, the National Clinical Effectiveness Committee (NCEC), established in September 2010, works to prioritise and quality assure National Clinical Guidelines (NCGs) so as to recommend them to the Minister for Health to become part of a suite of NCGs 1 . Clinical guidelines (CGs) are systematically developed statements, based on a thorough evaluation of the evidence, to assist practitioner and service users’ decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances across the entire clinical system 1 . The recommendations contained within CGs are underpinned by evidence syntheses, that is, systematic reviews or adaptation of existing CGs and or recommendations 2 . Ongoing evolution of the scientific literature brings the emergence of new evidence which can change the findings of a systematic review and, as a consequence, change the recommendations made within a CG. As such, CGs need to be updated regularly to ensure validity of the recommendations contained within 3 .

Updating CGs is an iterative process that is both resource intensive and time-consuming. Typically, CGs are updated in accordance with a pre-defined time-period. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 4 , American College of Physicians 5 and US Preventive Services Task Force 6 indicate that CGs should be updated every five years; in Ireland, the National Clinical Effectiveness Committee advises updating CGs every three years 1 . However, it is also acknowledged that deciding to update a CG depends on factors other than pre-defined time periods, such as the volume and potential impact of new research published on the topic, clinical burden of the topic, economic impact and resources available to update a guideline 1 . For that reason, policy makers and other stakeholders are advocating for a move away from updating guidelines based on a pre-defined time-period and moving towards updating guidelines based on prioritisation criteria, to ensure appropriate investment of resources 7 .

Just as evolution of the scientific literature brings new clinical evidence that can impact the recommendations within a CG, it also brings advancement in methodologies used in development and updating of CGs 3 . One such advancement has been the emergence of rapid and living guidelines which aim to provide timely advice for decision-makers by optimising the guideline development process whereby individual recommendations can be updated as soon as new relevant evidence becomes available 8 . The use of rapid and living guidelines has been especially evident throughout the COVID-19 pandemic where the emphasis was on development and implementation of strategies to manage the rapidly evolving evidence base in response to a public health emergency 9 .

Previous systematic reviews on this topic have summarised guidance from methodological handbooks for updating clinical practice guidelines 3 , strategies for prioritisation of clinical guidelines that require updating 7 and prioritisation processes for the de novo development, updating or adaptation of guidelines 10 . However, the evidence synthesised was largely published over a decade ago and related to update processes developed for a particular disease-specific guideline or specifically to updating systematic reviews, not updating clinical guidelines.

Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to describe the most recent guideline update processes, including up-to-date prioritisation methods, used by international or national groups who provide methods guidance for developing and updating clinical guidelines. The focus of this systematic review was not on adaptation, contextualization, or de novo development of guidelines, but instead updating processes for existing guidelines. This will support guideline development groups nationally and internationally in consideration of amendments to the current update processes.

Details of this protocol have been submitted to the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42021274400). Any amendments made to the protocol will be acknowledged on PROSPERO and in any subsequent publications. This protocol outlines the proposed approach to achieve the stated purpose and has been informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines 11 .

Criteria for considering publications for this review

This systematic review protocol has been developed to answer the review question:

What are the most recent guideline update processes, including up-to-date prioritisation methods, used by international or national groups who provide methods guidance for developing and updating clinical guidelines?

The review question was formulated in line with the CIMO (Context, Intervention, Mechanism, Outcome) framework 12 , as presented in Table 1 . The CIMO framework describes “the problematic Context, for which the design proposition suggests a certain Intervention type, to produce, through specified generative Mechanisms, the intended Outcome(s)” 12 . The context describes the environment within which change occurs, the intervention is what influences a change, the mechanism is triggered by the intervention and this produces the outcome 12 .

Table 1. Context, Intervention, Mechanism, Outcome.

| ▪ Clinical guidelines require updating to maintain relevancy. | |

| ▪ International or national groups provide methods guidance (in published handbooks and/or peer-reviewed articles) for developing and updating clinical guidelines, as well as prioritising clinical guidelines for updating. | |

| ▪ Clinical guidelines considered for updating (includes full, modular, rapid updates). ▪ Tools or guidance available to support prioritisation. | |

| ▪ Description of update (or retirement) process (including roles and responsibilities at each stage) ○ types of update that exist ○ criteria used to determine if update necessary ○ process for retiring a guideline ○ criteria to prioritise which guideline is updated first ○ criteria to prioritise which clinical questions within a guideline are updated ○ evidence synthesis methodologies used to update clinical questions ○ dissemination of updated guideline ○ resources required to undertake update ○ differences between review process for updated guideline verses original guideline ○ differences between approval and endorsement process for updated guideline versus original guideline ▪ Evaluation of the process ○ usability and or critique of the updating methodology ○ timeliness, that is, specific processes that enable a more efficient and timely update. |

The types of publications eligible for inclusion will be:

▪ methodological handbooks that provide updating guidance, including prioritisation methods, for clinical practice guidelines

▪ peer-reviewed articles that describe or have implemented updating guidance, including prioritisation methods.

Only publications from 2011 onwards will be considered for inclusion; publications published before 2011 will have been included in the index documents 3 , 7 but will not be included in this review.

Exclusion criteria. The following exclusion criteria will be applied:

▪ Due to issues relating to transferability of guidelines developed for specific diseases, disease-specific publications (handbooks and or peer-reviewed publications which describe, or have implemented, guidance for updating disease-specific guidelines).

▪ Editorials/commentaries/opinion pieces.

▪ Abstracts only.

▪ Animal studies.

▪ Non-English language publications.

Search methods for identification of studies

Due to changes in process and methodologies in guideline development in the last 10 years, the overall search span for this review will be the last 10-years (2011–2021). The primary data source for this review will be methodological handbooks which detail update processes, including prioritisation methods, used by international or national groups who provide methods guidance for developing and updating clinical guidelines. Through scoping searches, we identified a published systematic review of methodological handbooks that provide guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines 3 . This systematic review by Vernooij et al. 3 was published in 2014 and will be considered an index document, whereby for methodological handbooks, data from 2011–2012 will be taken from Vernooij et al. 3 and data from 2013–2021 will be gathered through a new search of organisations’ websites and grey literature.

The secondary data source will be peer-reviewed articles which detail the development of, and or evaluation of guideline update processes. For peer-reviewed articles, data from 2011–2021 will be gathered through a database search. While peer-reviewed articles will not be the primary data source for this systematic review, they may serve as “sign-posts” to the handbooks and may also provide qualitative data relating to the usability of the handbooks and update processes.

In 2017, Martinez-Garcia et al. 7 published a systematic review of prioritisation processes for updating guidelines which focused on peer-reviewed articles rather than methodological handbooks. Data specific to prioritisation methods from 2011–2015 will be taken from Martinez-Garcia et al. , 7 and data from 2016–2021 will be gathered from the new database search.

Organisations. The websites of organisations listed in Table 2 will be searched for relevant methodological handbooks. The organisations were chosen based on advice from the Clinical Effectiveness Unit of the Department of Health (which supports the work of the National Clinical Effectiveness Committee), and or identification of the organisation from previous systematic reviews on this topic and guidance being available in English.

When guideline manuals are not found online, or where any data gaps are identified, these will be addressed by contacting organisations (via email) to gather information relating to guideline update processes (including prioritisation methods). Other relevant organisations identified during the searching process will also have their website searched.

Table 2. Organisations that will be searched for relevant methodological handbooks.

| Organisation name | Organisation URL |

|---|---|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA | |

| Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia | |

| Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, Belgium | |

| Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Canada | |

| European Network for Health Technology Assessment | |

| Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland | |

| Guidelines International Network | |

| Institute of Medicine, USA | |

| McMaster GRADE centre, Canada | |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK | |

| Ravijuhend, Estonia | |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Scotland | |

| National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden | |

| Public Health Agency of Sweden, Sweden | |

| The Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand, New Zealand | |

| World Health Organization |

Grey literature. Other sources of grey literature will be searched for relevant methodological handbooks. These are listed in Table 3 .

Table 3. Grey literature that will be searched for relevant methodological handbooks.

| Grey literature source | URL |

|---|---|

| Google (first 10 pages of results) | |

| Open Grey | |

| Reference chasing | NA |

Databases. The following databases will be searched for peer-reviewed articles using the search strategy defined in Supplementary file 1:

▪ Medline (EBSCO)

▪ Embase (OVID)

▪ The Cochrane Methodology Register

Selection of eligible publications

Methodological handbooks will be identified through searching the websites of eligible organisations (see Table 2 ) and through screening the methodological handbooks included in the index document 3 . This will be done by one reviewer and relevant handbooks will be imported into Endnote (Version X8). Imported handbooks will be reviewed by a second reviewer to confirm their eligibility.

All citations identified from the collective search strategy (see Supplementary file 1), and through screening the peer-reviewed articles included in the index document 7 , will be exported to EndNote (Version X8) for reference management, where duplicates will be identified and removed. Using Covidence ( www.covidence.org ), two reviewers will independently review the titles and abstracts of the remaining citations to identify those for full-text review. The full texts will be obtained and independently evaluated by two reviewers applying the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Where disagreements occur, discussions will be held to reach consensus and where necessary, a third reviewer will be involved. Citations excluded during the full-text review stage will be documented alongside the reasoning for their exclusion and included in the PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Data will be extracted from methodological handbooks by one reviewer and checked for accuracy and omissions by a second. Where disagreements occur, discussions will be held to reach consensus and where necessary, a third reviewer will be involved. Data extraction will be conducted in Microsoft Word, using a data extraction form (Supplementary file 2). The data extraction form will be piloted first and refined as necessary.

Relevant data to be extracted will include:

▪ the types of update that exist, for example partial or full

▪ criteria used to determine if an update is necessary

▪ process for retiring a guideline

▪ criteria used to prioritise which guideline to update first

▪ criteria used to prioritise clinical questions to be updated within a guideline

▪ evidence synthesis methodologies used to update clinical guideline and clinical questions

▪ dissemination of updated clinical guideline

▪ resources required to undertake update

▪ process of reviewing the updated guideline

▪ process of approving and endorsing the updated guideline.

Peer-reviewed articles will not be the primary data source for this systematic review; the primary data source is most likely to be the methodological handbooks. However, in addition to signposting to methodological handbooks, and providing supplemental data relating to update and prioritisation processes, peer-reviewed articles may also provide usability and process evaluation data (relating to the associated handbook); these data will be extracted (see Supplementary file 2).

Quality assessment

Methodological handbooks will be quality assessed independently by two reviewers and any disagreements will be resolved by deliberation, or if necessary, a third reviewer. In the absence of an appropriate quality assessment tool that is specific for methodological handbooks or guidance, quality will be assessed using the GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist, which is a checklist of items to consider during the development of guidelines. Specifically, we will use the six criteria relating to updating guidelines 13 . Reviewers will assess, that the methodological handbook covers the following areas:

1. Addresses policy, procedure and timeline for routinely monitoring and reviewing whether the guideline needs to be updated.

2. Addresses who will be responsible for routinely monitoring the literature and assessing whether new significant evidence is available.

3. Sets the conditions that will determine when a partial or a full update of the guideline is required.

4. Makes arrangements for guideline group membership and participation after completion of the guideline.

5. Addresses plans for the funding and logistics for updating the guideline in the future.

6. Addresses documentation of the plan and proposed methods for updating the guideline to ensure they are followed 13 .

Methodological quality of peer-reviewed articles will be independently assessed by two reviewers. Depending on study design an appropriate version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale 14 or the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional studies (AXIS) 15 will be used. The tools will be piloted first on a small number of included studies, and modifications made if needed, before standardising for the remaining studies. Any disagreements will be resolved by deliberation or, if necessary, a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

As the main data to be extracted for this review is descriptive in nature a narrative synthesis will be undertaken. Data will be summarised under the following headings:

▪ Description of update (or retirement) process (including roles and responsibilities at each stage)

▪ Evaluation of the process.

Dissemination

The PRISMA checklist will be used to report findings of the review. We will communicate the findings to the NCEC to inform updating processes in Ireland. Findings will also be communicated by publication in a peer-reviewed journal, and by participation in scientific meetings and national and international conferences.

Study status

Agreement on the study protocol, searching of organisations, grey literature and databases, data extraction and quality assessment is complete. Data synthesis is ongoing.

Updating clinical guidelines is an iterative process that is both resource intensive and time-consuming. This systematic review will summarise the most recent updating and prioritisation processes for clinical guidelines. The findings will support guideline development organisations nationally and internationally to ensure appropriate investment of resources. It will support them in considering and or modifying their current methodologies for updating clinical guidelines. This will be of particular interest in light of new and updated methodologies that have been especially evident throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

Underlying data.

No data are associated with this article.

Extended data

Figshare: Supplementary files, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16723063 .

This project contains the following extended data:

- Supplementary file 1: Search strategy

- Supplementary file 2: Data extraction tables

Reporting guidelines

Figshare: PRISMA-P Checklist for “Processes for updating guidelines: protocol for a systematic review”, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16723021 .

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Authors’ contribution

KC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation; JQ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Writing – Review & Editing; BC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Writing – Review & Editing; BT: Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Writing – Review & Editing; MC: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; SS: Writing – Review & Editing; MR: Writing – Review & Editing; MON: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Clinical Effectiveness Unit of the Department of Health and acknowledge the support of the Health Technology Assessment directorate at HIQA.

- 1. Government of Ireland: How to develop a national clinical guideline: a manual for guideline developers. [updated 2019 Jan; cited 2021 Jul 29]. Reference Source

- 2. Sharp MK, Tyner B, Awang Baki DAB, et al. : Evidence synthesis summary formats for clinical guideline development group members: a mixed-methods systematic review protocol [version 1; peer review: 1 approved with reservations]. HRB Open Res. 2021; 4 : 76. Publisher Full Text

- 3. Vernooij RW, Sanabria AJ, Solà I, et al. : Guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review of methodological handbooks. Implement Sci. 2014; 9 : 3. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Developing NICE guidelines: the manual (PMG20). [updated 2020 Oct 15; cited 2021 Sep 28]. Reference Source

- 5. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Lin JS, et al. : The Development of Clinical Guidelines and Guidance Statements by the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians: Update of Methods. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170 (12): 863–70. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 6. US Preventive Services Task Force: Procedure Manual. [updated 2021 May; cited 2021 Sep 28]. Reference Source

- 7. Martínez García L, Pardo-Hernández H, Sanabria AJ, et al. : Guideline on terminology and definitions of updating clinical guidelines: The Updating Glossary. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018; 95 : 28–33. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 8. Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, et al. : Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017; 91 : 47–53. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 9. Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. : Rapid review methods guidance aids in Cochrane’s quick response to the COVID-19 crisis. In: Collaborating in response to COVID-19: editorial and methods initiatives across Cochrane. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021; 28–31. Reference Source

- 10. El-Harakeh A, Lotfi T, Ahmad A, et al. : The implementation of prioritization exercises in the development and update of health practice guidelines: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (3): e0229249. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 11. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. : Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015; 4 (1): 1. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 12. Denyer D, Tranfield D, van Aken JE: Developing Design Propositions through Research Synthesis. Organization Studies. 2008; 29 (3): 393–413. Publisher Full Text

- 13. GIN-McMaster: GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist. [updated 2014 Jun 02; cited 2021 Jul 29]. Reference Source

- 14. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. : The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. [updated 2001; cited 2021 Jul 29]. Reference Source

- 15. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. : Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016; 6 (12): e011458. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

Comments on this article Comments (0)

Open peer review.

Is the rationale for, and objectives of, the study clearly described?

Is the study design appropriate for the research question?

Are sufficient details of the methods provided to allow replication by others?

Are the datasets clearly presented in a useable and accessible format?

Not applicable

Competing Interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Reviewer Expertise: Public health, health services research, clinical guideline development

- Respond or Comment

- COMMENT ON THIS REPORT

- Reference is made to “national clinical

- Reference is made to “national clinical guidelines” in the abstract and the first paragraph of the introduction. However, the remit of the proposed work seems broader. Guidelines may be in place for jurisdictions that are sub-national, and for professional organizations. In addition, I was left uncertain whether preventive health care and public health were within scope.

- In the second paragraph of the introduction, signal detection methods have been proposed for triggering updates of evidence syntheses that underpin guidelines. See for example Newberry SJ et al. 1 , Shekelle PG et al. 2 . Briefly showing the readers that these have been considered in developing the searches in the systematic review will increase confidence in the evidence as to whether or not these methods have been used; if they have been used, how much and what has been the experience; if there is no evidence that they have been used, is there any on why not.

- I was surprised that there was no mention of the concept of living guidelines – see Akl EA et al. 3 (the same comment as for the signal detection methods; the COVID-19 pandemic has catalyzed interest) or the AGREE statement 4 ( https://www.agreetrust.org/agree-ii/ ), which includes a point about updating procedures (domain 3, point 14). The AGREE II instrument is a tool to assess the quality and reporting of practice guidelines and is internationally used. Having guidelines based on up-to-date evidence is obviously an important domain of guideline quality, and I think it's important to make the link to this in the review.

- Table 1 – what belongs under “Mechanism” and under “Outcome” is unclear.

- Table 2 – consideration might be given to Canadian and US Task Forces on Preventive Health Care, the UK National Screening Committee , and the IARC Cancer Prevention Handbooks (e.g. cervical cancer screening is covered in Vol. 10 and the upcoming Vol. 18; breast cancer in Vols. 7 and 15). This links back to the comments I made on the scope of the review. If preventive health is within scope, these strike me as well recognized international sources to consider.