Instant insights, infinite possibilities

55 research questions about mental health

Last updated

11 March 2024

Reviewed by

Brittany Ferri, PhD, OTR/L

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Research in the mental health space helps fill knowledge gaps and create a fuller picture for patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers. Over time, these efforts result in better quality care and more accessible treatment options for those who need them.

Use this list of mental health research questions to kickstart your next project or assignment and give yourself the best chance of producing successful and fulfilling research.

- Why does mental health research matter?

Mental health research is an essential area of study. It includes any research that focuses on topics related to people’s mental and emotional well-being.

As a complex health topic that, despite the prevalence of mental health conditions, still has an unending number of unanswered questions, the need for thorough research into causes, triggers, and treatment options is clear.

Research into this heavily stigmatized and often misunderstood topic is needed to find better ways to support people struggling with mental health conditions. Understanding what causes them is another crucial area of study, as it enables individuals, companies, and policymakers to make well-informed choices that can help prevent illnesses like anxiety and depression.

- How to choose a strong mental health research topic

As one of the most important parts of beginning a new research project, picking a topic that is intriguing, unique, and in demand is a great way to get the best results from your efforts.

Mental health is a blanket term with many niches and specific areas to explore. But, no matter which direction you choose, follow the tips below to ensure you pick the right topic.

Prioritize your interests and skills

While a big part of research is exploring a new and exciting topic, this exploration is best done within a topic or niche in which you are interested and experienced.

Research is tough, even at the best of times. To combat fatigue and increase your chances of pushing through to the finish line, we recommend choosing a topic that aligns with your personal interests, training, or skill set.

Consider emerging trends

Topical and current research questions are hot commodities because they offer solutions and insights into culturally and socially relevant problems.

Depending on the scope and level of freedom you have with your upcoming research project, choosing a topic that’s trending in your area of study is one way to get support and funding (if you need it).

Not every study can be based on a cutting-edge topic, but this can be a great way to explore a new space and create baseline research data for future studies.

Assess your resources and timeline

Before choosing a super ambitious and exciting research topic, consider your project restrictions.

You’ll need to think about things like your research timeline, access to resources and funding, and expected project scope when deciding how broad your research topic will be. In most cases, it’s better to start small and focus on a specific area of study.

Broad research projects are expensive and labor and resource-intensive. They can take years or even decades to complete. Before biting off more than you can chew, consider your scope and find a research question that fits within it.

Read up on the latest research

Finally, once you have narrowed in on a specific topic, you need to read up on the latest studies and published research. A thorough research assessment is a great way to gain some background context on your chosen topic and stops you from repeating a study design. Using the existing work as your guide, you can explore more specific and niche questions to provide highly beneficial answers and insights.

- Trending research questions for post-secondary students

As a post-secondary student, finding interesting research questions that fit within the scope of your classes or resources can be challenging. But, with a little bit of effort and pre-planning, you can find unique mental health research topics that will meet your class or project requirements.

Examples of research topics for post-secondary students include the following:

How does school-related stress impact a person’s mental health?

To what extent does burnout impact mental health in medical students?

How does chronic school stress impact a student’s physical health?

How does exam season affect the severity of mental health symptoms?

Is mental health counseling effective for students in an acute mental crisis?

- Research questions about anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression are two of the most commonly spoken about mental health conditions. You might assume that research about these conditions has already been exhausted or that it’s no longer in demand. That’s not the case at all.

According to a 2022 survey by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 12.5% of American adults struggle with regular feelings of worry, nervousness, and anxiety, and 5% struggle with regular feelings of depression. These percentages amount to millions of lives affected, meaning new research into these conditions is essential.

If either of these topics interests you, here are a few trending research questions you could consider:

Does gender play a role in the early diagnosis of anxiety?

How does untreated anxiety impact quality of life?

What are the most common symptoms of anxiety in working professionals aged 20–29?

To what extent do treatment delays impact quality of life in patients with undiagnosed anxiety?

To what extent does stigma affect the quality of care received by people with anxiety?

Here are some examples of research questions about depression:

Does diet play a role in the severity of depression symptoms?

Can people have a genetic predisposition to developing depression?

How common is depression in work-from-home employees?

Does mood journaling help manage depression symptoms?

What role does exercise play in the management of depression symptoms?

- Research questions about personality disorders

Personality disorders are complex mental health conditions tied to a person’s behaviors, sense of self, and how they interact with the world around them. Without a diagnosis and treatment, people with personality disorders are more likely to develop negative coping strategies during periods of stress and adversity, which can impact their quality of life and relationships.

There’s no shortage of specific research questions in this category. Here are some examples of research questions about personality disorders that you could explore:

What environments are more likely to trigger the development of a personality disorder?

What barriers impact access to care for people with personality disorders?

To what extent does undiagnosed borderline personality disorder impact a person’s ability to build relationships?

How does group therapy impact symptom severity in people with schizotypal personality disorder?

What is the treatment compliance rate of people with paranoid personality disorder?

- Research questions about substance use disorders

“Substance use disorders” is a blanket term for treatable behaviors and patterns within a person’s brain that lead them to become dependent on illicit drugs, alcohol, or prescription medications. It’s one of the most stigmatized mental health categories.

The severity of a person’s symptoms and how they impact their ability to participate in their regular daily life can vary significantly from person to person. But, even in less severe cases, people with a substance use disorder display some level of loss of control due to their need to use the substance they are dependent on.

This is an ever-evolving topic where research is in hot demand. Here are some example research questions:

To what extent do meditation practices help with craving management?

How effective are detox centers in treating acute substance use disorder?

Are there genetic factors that increase a person’s chances of developing a substance use disorder?

How prevalent are substance use disorders in immigrant populations?

To what extent do prescription medications play a role in developing substance use disorders?

- Research questions about mental health treatments

Treatments for mental health, pharmaceutical therapies in particular, are a common topic for research and exploration in this space.

Besides the clinical trials required for a drug to receive FDA approval, studies into the efficacy, risks, and patient experiences are essential to better understand mental health therapies.

These types of studies can easily become large in scope, but it’s possible to conduct small cohort research on mental health therapies that can provide helpful insights into the actual experiences of the people receiving these treatments.

Here are some questions you might consider:

What are the long-term effects of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with severe depression?

How common is insomnia as a side effect of oral mental health medications?

What are the most common causes of non-compliance for mental health treatments?

How long does it take for patients to report noticeable changes in symptom severity after starting injectable mental health medications?

What issues are most common when weaning a patient off of an anxiety medication?

- Controversial mental health research questions

If you’re interested in exploring more cutting-edge research topics, you might consider one that’s “controversial.”

Depending on your own personal values, you might not think many of these topics are controversial. In the context of the research environment, this depends on the perspectives of your project lead and the desires of your sponsors. These topics may not align with the preferred subject matter.

That being said, that doesn’t make them any less worth exploring. In many cases, it makes them more worthwhile, as they encourage people to ask questions and think critically.

Here are just a few examples of “controversial” mental health research questions:

To what extent do financial crises impact mental health in young adults?

How have climate concerns impacted anxiety levels in young adults?

To what extent do psychotropic drugs help patients struggling with anxiety and depression?

To what extent does political reform impact the mental health of LGBTQ+ people?

What mental health supports should be available for the families of people who opt for medically assisted dying?

- Research questions about socioeconomic factors & mental health

Socioeconomic factors—like where a person grew up, their annual income, the communities they are exposed to, and the amount, type, and quality of mental health resources they have access to—significantly impact overall health.

This is a complex and multifaceted issue. Choosing a research question that addresses these topics can help researchers, experts, and policymakers provide more equitable and accessible care over time.

Examples of questions that tackle socioeconomic factors and mental health include the following:

How does sliding scale pricing for therapy increase retention rates?

What is the average cost to access acute mental health crisis care in [a specific region]?

To what extent does a person’s environment impact their risk of developing a mental health condition?

How does mental health stigma impact early detection of mental health conditions?

To what extent does discrimination affect the mental health of LGBTQ+ people?

- Research questions about the benefits of therapy

Therapy, whether that’s in groups or one-to-one sessions, is one of the most commonly utilized resources for managing mental health conditions. It can help support long-term healing and the development of coping mechanisms.

Yet, despite its popularity, more research is needed to properly understand its benefits and limitations.

Here are some therapy-based questions you could consider to inspire your own research:

In what instances does group therapy benefit people more than solo sessions?

How effective is cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with severe anxiety?

After how many therapy sessions do people report feeling a better sense of self?

Does including meditation reminders during therapy improve patient outcomes?

To what extent has virtual therapy improved access to mental health resources in rural areas?

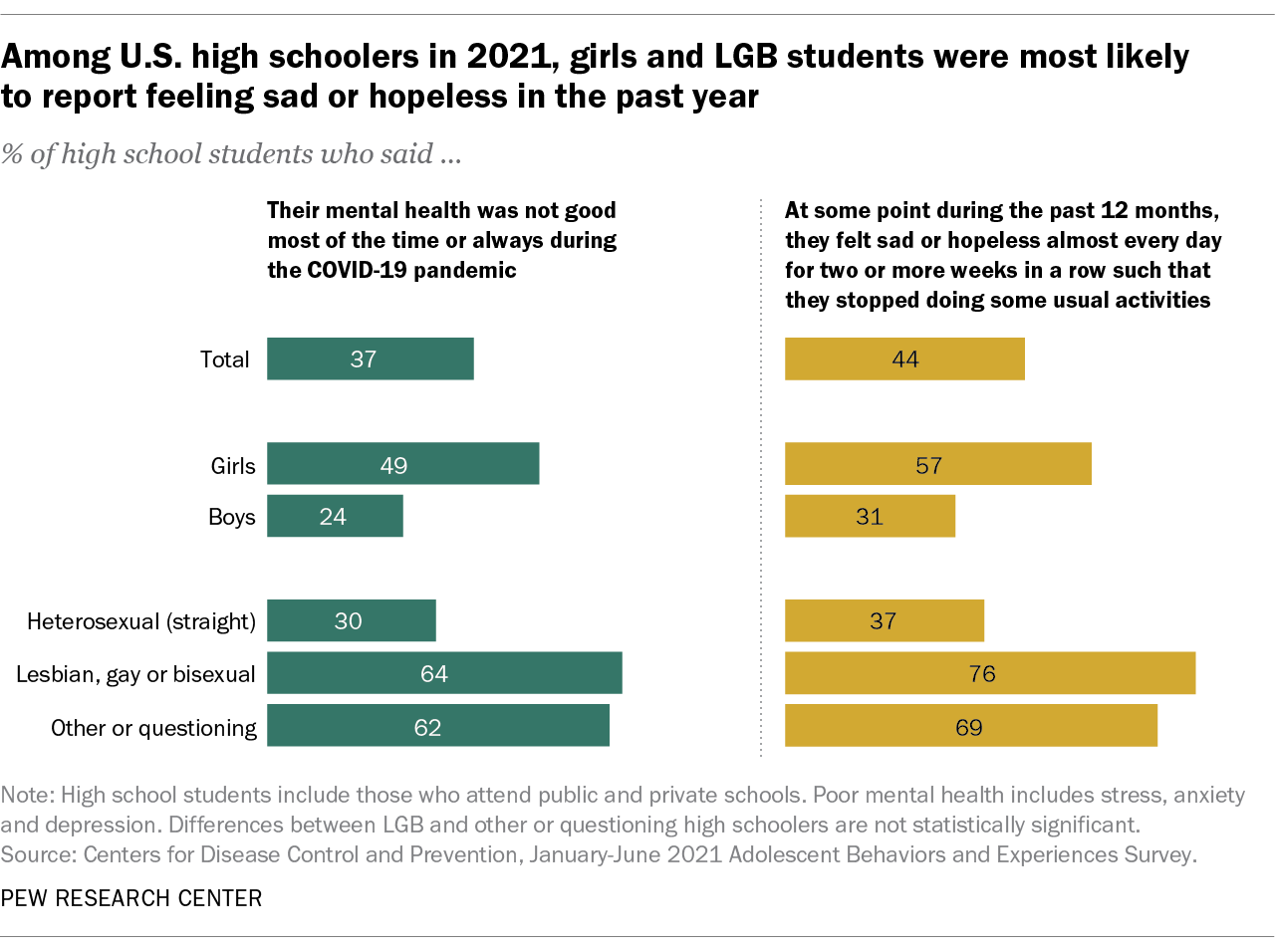

- Research questions about mental health trends in teens

Adolescents are a particularly interesting group for mental health research due to the prevalence of early-onset mental health symptoms in this age group.

As a time of self-discovery and change, puberty brings plenty of stress, anxiety, and hardships, all of which can contribute to worsening mental health symptoms.

If you’re looking to learn more about how to support this age group with mental health, here are some examples of questions you could explore:

Does parenting style impact anxiety rates in teens?

How early should teenagers receive mental health treatment?

To what extent does cyberbullying impact adolescent mental health?

What are the most common harmful coping mechanisms explored by teens?

How have smartphones affected teenagers’ self-worth and sense of self?

- Research questions about social media and mental health

Social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and X (formerly Twitter) have significantly impacted day-to-day communication. However, despite their numerous benefits and uses, they have also become a significant source of stress, anxiety, and self-worth issues for those who use them.

These platforms have been around for a while now, but research on their impact is still in its infancy. Are you interested in building knowledge about this ever-changing topic? Here are some examples of social media research questions you could consider:

To what extent does TikTok’s mental health content impact people’s perception of their health?

How much non-professional mental health content is created on social media platforms?

How has social media content increased the likelihood of a teen self-identifying themselves with ADHD or autism?

To what extent do social media photoshopped images impact body image and self-worth?

Has social media access increased feelings of anxiety and dread in young adults?

- Mental health research is incredibly important

As you have seen, there are so many unique mental health research questions worth exploring. Which options are piquing your interest?

Whether you are a university student considering your next paper topic or a professional looking to explore a new area of study, mental health is an exciting and ever-changing area of research to get involved with.

Your research will be valuable, no matter how big or small. As a niche area of healthcare still shrouded in stigma, any insights you gain into new ways to support, treat, or identify mental health triggers and trends are a net positive for millions of people worldwide.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Topics & Ideas: Mental Health

100+ Mental Health Research Topic Ideas To Fast-Track Your Project

If you’re just starting out exploring mental health topics for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll help kickstart your research topic ideation process by providing a hearty list of mental health-related research topics and ideas.

PS – This is just the start…

We know it’s exciting to run through a list of research topics, but please keep in mind that this list is just a starting point . To develop a suitable education-related research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan of action to fill that gap.

If this sounds foreign to you, check out our free research topic webinar that explores how to find and refine a high-quality research topic, from scratch. Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help, consider our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Overview: Mental Health Topic Ideas

- Mood disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Psychotic disorders

- Personality disorders

- Obsessive-compulsive disorders

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Eating disorders

- Substance-related disorders

Mood Disorders

Research in mood disorders can help understand their causes and improve treatment methods. Here are a few ideas to get you started.

- The impact of genetics on the susceptibility to depression

- Efficacy of antidepressants vs. cognitive behavioural therapy

- The role of gut microbiota in mood regulation

- Cultural variations in the experience and diagnosis of bipolar disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder: Environmental factors and treatment

- The link between depression and chronic illnesses

- Exercise as an adjunct treatment for mood disorders

- Hormonal changes and mood swings in postpartum women

- Stigma around mood disorders in the workplace

- Suicidal tendencies among patients with severe mood disorders

Anxiety Disorders

Research topics in this category can potentially explore the triggers, coping mechanisms, or treatment efficacy for anxiety disorders.

- The relationship between social media and anxiety

- Exposure therapy effectiveness in treating phobias

- Generalised Anxiety Disorder in children: Early signs and interventions

- The role of mindfulness in treating anxiety

- Genetics and heritability of anxiety disorders

- The link between anxiety disorders and heart disease

- Anxiety prevalence in LGBTQ+ communities

- Caffeine consumption and its impact on anxiety levels

- The economic cost of untreated anxiety disorders

- Virtual Reality as a treatment method for anxiety disorders

Psychotic Disorders

Within this space, your research topic could potentially aim to investigate the underlying factors and treatment possibilities for psychotic disorders.

- Early signs and interventions in adolescent psychosis

- Brain imaging techniques for diagnosing psychotic disorders

- The efficacy of antipsychotic medication

- The role of family history in psychotic disorders

- Misdiagnosis and delayed treatment of psychotic disorders

- Co-morbidity of psychotic and mood disorders

- The relationship between substance abuse and psychotic disorders

- Art therapy as a treatment for schizophrenia

- Public perception and stigma around psychotic disorders

- Hospital vs. community-based care for psychotic disorders

Personality Disorders

Research topics within in this area could delve into the identification, management, and social implications of personality disorders.

- Long-term outcomes of borderline personality disorder

- Antisocial personality disorder and criminal behaviour

- The role of early life experiences in developing personality disorders

- Narcissistic personality disorder in corporate leaders

- Gender differences in personality disorders

- Diagnosis challenges for Cluster A personality disorders

- Emotional intelligence and its role in treating personality disorders

- Psychotherapy methods for treating personality disorders

- Personality disorders in the elderly population

- Stigma and misconceptions about personality disorders

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

Within this space, research topics could focus on the causes, symptoms, or treatment of disorders like OCD and hoarding.

- OCD and its relationship with anxiety disorders

- Cognitive mechanisms behind hoarding behaviour

- Deep Brain Stimulation as a treatment for severe OCD

- The impact of OCD on academic performance in students

- Role of family and social networks in treating OCD

- Alternative treatments for hoarding disorder

- Childhood onset OCD: Diagnosis and treatment

- OCD and religious obsessions

- The impact of OCD on family dynamics

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Causes and treatment

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Research topics in this area could explore the triggers, symptoms, and treatments for PTSD. Here are some thought starters to get you moving.

- PTSD in military veterans: Coping mechanisms and treatment

- Childhood trauma and adult onset PTSD

- Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) efficacy

- Role of emotional support animals in treating PTSD

- Gender differences in PTSD occurrence and treatment

- Effectiveness of group therapy for PTSD patients

- PTSD and substance abuse: A dual diagnosis

- First responders and rates of PTSD

- Domestic violence as a cause of PTSD

- The neurobiology of PTSD

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

This category of mental health aims to better understand disorders like Autism and ADHD and their impact on day-to-day life.

- Early diagnosis and interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder

- ADHD medication and its impact on academic performance

- Parental coping strategies for children with neurodevelopmental disorders

- Autism and gender: Diagnosis disparities

- The role of diet in managing ADHD symptoms

- Neurodevelopmental disorders in the criminal justice system

- Genetic factors influencing Autism

- ADHD and its relationship with sleep disorders

- Educational adaptations for children with neurodevelopmental disorders

- Neurodevelopmental disorders and stigma in schools

Eating Disorders

Research topics within this space can explore the psychological, social, and biological aspects of eating disorders.

- The role of social media in promoting eating disorders

- Family dynamics and their impact on anorexia

- Biological basis of binge-eating disorder

- Treatment outcomes for bulimia nervosa

- Eating disorders in athletes

- Media portrayal of body image and its impact

- Eating disorders and gender: Are men underdiagnosed?

- Cultural variations in eating disorders

- The relationship between obesity and eating disorders

- Eating disorders in the LGBTQ+ community

Substance-Related Disorders

Research topics in this category can focus on addiction mechanisms, treatment options, and social implications.

- Efficacy of rehabilitation centres for alcohol addiction

- The role of genetics in substance abuse

- Substance abuse and its impact on family dynamics

- Prescription drug abuse among the elderly

- Legalisation of marijuana and its impact on substance abuse rates

- Alcoholism and its relationship with liver diseases

- Opioid crisis: Causes and solutions

- Substance abuse education in schools: Is it effective?

- Harm reduction strategies for drug abuse

- Co-occurring mental health disorders in substance abusers

Choosing A Research Topic

These research topic ideas we’ve covered here serve as thought starters to help you explore different areas within mental health. They are intentionally very broad and open-ended. By engaging with the currently literature in your field of interest, you’ll be able to narrow down your focus to a specific research gap .

It’s important to consider a variety of factors when choosing a topic for your dissertation or thesis . Think about the relevance of the topic, its feasibility , and the resources available to you, including time, data, and academic guidance. Also, consider your own interest and expertise in the subject, as this will sustain you through the research process.

Always consult with your academic advisor to ensure that your chosen topic aligns with academic requirements and offers a meaningful contribution to the field. If you need help choosing a topic, consider our private coaching service.

Good morning everyone. This are very patent topics for research in neuroscience. Thank you for guidance

What if everything is important, original and intresting? as in Neuroscience. I find myself overwhelmd with tens of relveant areas and within each area many optional topics. I ask myself if importance (for example – able to treat people suffering) is more relevant than what intrest me, and on the other hand if what advance me further in my career should not also be a consideration?

This information is really helpful and have learnt alot

Phd research topics on implementation of mental health policy in Nigeria :the prospects, challenges and way forward.

This info is indeed help for someone to formulate a dissertation topic. I have already got my path from here.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 July 2023

Assessment of depression and anxiety in young and old with a question-based computational language approach

- Sverker Sikström 1 ,

- Bleona Kelmendi 2 &

- Ninni Persson 3 , 4

npj Mental Health Research volume 2 , Article number: 11 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

8003 Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Human behaviour

Middle aged adults experience depression and anxiety differently than younger adults. Age may affect life circumstances, depending on accessibility of social connections, jobs, physical health, etc, as these factors influence the prevalence and symptomatology. Depression and anxiety are typically measured using rating scales; however, recent research suggests that such symptoms can be assessed by open-ended questions that are analysed by question-based computational language assessments (QCLA). Here, we study middle aged and younger adults’ responses about their mental health using open-ended questions and rating scales about their mental health. We then analyse their responses with computational methods based on natural language processing (NLP). The results demonstrate that: (1) middle aged adults describe their mental health differently compared to younger adults; (2) where, for example, middle aged adults emphasise depression and loneliness whereas young adults list anxiety and financial concerns; (3) different semantic models are warranted for younger and middle aged adults; (4) compared to young participants, the middle aged participants described their mental health more accurately with words; (5) middle-aged adults have better mental health than younger adults as measured by semantic measures. In conclusion, NLP combined with machine learning methods may provide new opportunities to identify, model, and describe mental health in middle aged and younger adults and could possibly be applied to the older adults in future research. These semantic measures may provide ecological validity and aid the assessment of mental health.

Introduction

Depression and anxiety disorders are global phenomena and create widespread and growing problems in healthcare 1 . Untreated depression can be disabling 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 and have financial consequences 6 . In 2000, the economic burden of depression in the US was an estimated USD 83.1 billion, of which USD 51.5 billion were workplace costs 7 . Early and efficient diagnostic methods are essential for applying effective and appropriate treatment. The development of more precise diagnostic instruments and accessible treatment methods is warranted. One important aspect is how such disorders vary across the lifespan. Rating scales have typically been used to quantify levels of depression and anxiety. In contrast, language is a natural way for people to communicate their mental states, and language ability is preserved or even improves as people age 8 . Recent advancements in computational language models (CLA) allow for quantitative assessment of depression and anxiety using words generated from open questions related to mental health 9 . This unique study aims to assess age differences in the reporting of mental health issues using question based computational language assessments (QCLA), which to the best of our knowledge has not been done previously.The prevalence of depression and anxiety varies across the lifespan 10 , 11 , therefore the age dependent differences in the word responses and description of mental health using the QCLA approach is of interest. Studies have identified age differences in the prevalence of depression and anxiety. Younger adults (16–29 years) were more likely to be affected by depression and severe anxiety than the older adults 10 . Contrary to this report, Lenze et al. 12 , found a relatively high rate of both current and lifetime anxiety disorders in the elderly, where 35% of the older participants had received an anxiety disorder diagnosis at least once, and 23% had been diagnosed recently. In summary, the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders varies across the lifespan.

In the following, we will provide a current review of the literature on the differences in terms of mental health between younger, middle age and old adults.

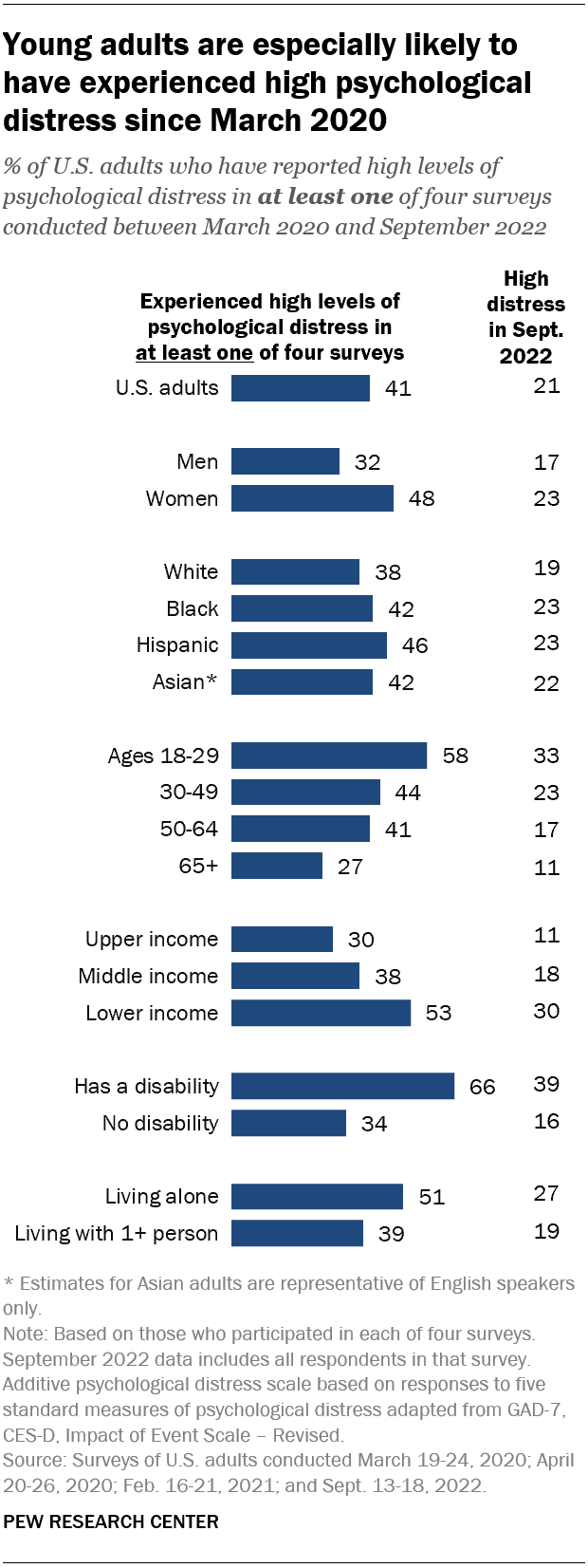

Young adults

Younger adults (16–29 years) are more likely to be affected by depression and severe anxiety than older adults 10 . In 2022, the young age group was most affected by severe anxiety at 16% and in Sweden 13 ; 4% was diagnosed with depression 13 . There is emerging evidence, that the prevalence of anxiety disorders is associated with young age, but also female gender and given chronic diseases 14 . In terms of aetiology, different subtypes of childhood maltreatment, child–parent bonding, stressful life events, as well as a genetic liability predict subsequent depression 15 , 16 . Depression is a risk factor for all-cause mortality, with greater risk for greater severity 17 . Thus, suicide is the most common cause of death in young men in the United Kingdom aged between 25 and 34 years 18 . Life changes and stress because of the Covid-19 pandemic are mirrored in an increase of depression and anxiety in the young 19 . Younger adults who struggle financially are at higher risk of mental health problems 20 .

Middle-aged adults

In Sweden, approximately 7% of middle-aged adults (30–59 years) are diagnosed with depression 13 , while only very few are affected by severe anxiety 13 . Regarding the period prevalence of 1 year, one in seven middle-aged participants (45–64 years) experienced symptoms consistent with ICD-10 anxiety or affective disorder in the preceding 12 months 21 . Anxiety disorders are most prevalent in the lifespan of 25–44 years 13 . In comparison to the prevalence of 1 in 16 of the older age group (60–75 and older), middle-aged adults were more likely to be affected by anxiety and affective disorders 21 . Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental illness that may occur at any age during the lifespan. However, the highest risk period for onset is from mid to late adolescence to early 40s 22 . The presence of a physical disorder is significantly associated with the presence of mental disorders for middle-aged people 21 . Depression may even worsen health conditions, as it is associated with macrovascular complications and all-cause mortality in a patient cohort with diabetes 23 . For anxiety disorders among middle-aged and older adults, physical health, socioeconomic status, immigrant status and nutritional factors are associated with its occurrence 24 . Perceived stress interacts with age during the development of depression and anxiety disorders 25 , 26 . Employment and marital status may function as an important predictor of mental disorders in middle-aged groups 21 . Middle-aged participants were more likely to be affected by a mental disorder 12 months after experiencing separation, divorce, or death of a partner 13 , 21 .

Regarding the point and lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the elderly, Lenze et al. 12 found a relatively high rate of both current and lifetime anxiety disorders in the elderly, where 35% of the older participants had received an anxiety disorder diagnosis at least once, and 24% had been diagnosed recently. Depression late in life displays a clinical phenomenon 27 ; there is a greater likelihood of comorbidities, differing aetiology and symptom expression compared to depression in younger adults. The aetiology of depression in the elderly is more heterogeneous than in younger adults 28 . Age-related changes in the brain, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases may be of importance for the development of depression in later life 27 , 28 . Studies have shown that comorbidity between clinically significant depression and anxiety may be as high as 48.3% 29 . The risk of mortality due to depression and anxiety disorders is higher in older adults 30 , while suicide risk is particularly high in older men 31 . For the elderly (75 years or older), the likelihood for a suicide attempt rises by three times in comparison to younger age groups 32 . Anxiety-related disorders are also correlated with a higher level of suicidality 12 . The elderly showed higher levels of loneliness, as well as higher levels of distress and exhaustion during the Covid-19 pandemic, with anxiety influencing the emergence of depression 33 . Bergdahl and Bergdahl 25 observed perceived stress to be impacting the development of depression and anxiety disorders among high age groups (60–69 years) in Sweden. Elderly are more likely to be widowed and in poor health compared to younger adults, which can aggravate the risk of depression 34 , 35 . In contrast, social capital (i.e., resources from social networks) may function as a source of mental wellbeing in the elderly 36 .

In summary, the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders varies across the lifespan. While there are no age of onset (AOO) specific guidelines for treating depression, the treatment of pre-adult or late-life depression should be considered individually depending on the patient 22 , as age-specific differences in life circumstances may influence the onset. Therefore specialised diagnostic methods should be considered for younger and older adults implementing each reality of life and language for patients affected by depression and anxiety disorders.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have shown beneficial effects in clinical decision-making, treatments, managing healthcare and research 37 , 38 , 39 . AI technologies can help quantify mental health in electronic health records, mood rating scales, brain imaging data, novel monitoring systems, smartphone or video data and social media platforms. AI has demonstrated great accuracy in predicting and classifying depression, anxiety and other psychiatric illnesses or suicide ideation 40 , 41 . AI methods have been used to analyse social media posts for depression, providing an opportunity for studying a large population 42 , 43 using probabilistic models, crowdsourcing technology 44 , 45 and computational language assessments (CLA) (Eichstaedt et al. 6 ). These findings suggest the significance and value of words when describing mental health.

A natural language processing method called latent semantic analysis (LSA) 46 , where open-ended questions about mental health are applied, may facilitate registration of information closer to individual behaviour in a real-world setting. The LSA has been validated against several traditional rating scales, and demonstrated good statistical properties with competitive, or even higher reliability 9 .

The QCLA can be applied to semantic data (i.e., words and sentences), where the assessment is based on high-dimensional word embeddings from a large language corpus 47 ). Kjell et al. 48 investigated word response relating to the symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalised anxiety disorders (GAD) as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The results of the QCLA showed that all primary and secondary language responses correlated significantly with the depression scale Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9 49 ). Together, these findings suggest that QCLA may be helpful in clinical assessment of mental health.

Machine learning (ML) and (AI) methods demonstrate potential, as subjective descriptions of mental health can be monitored and to facilitate the diagnostic process 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 . Advances in ML and AI could provide more personalised care for patients to aid decisions on the best suitable treatments and interventions 54 . While text offers a rich source of unstructured information for ML models, there is risk that this learning will also pick up the human biases that ML is based on ref. 54 . An example of such bias is that old and young people may be assessed on the same criteria, whereas symptoms may differ with age, which emphasises that more research is required.

Currently, there is a large gap in knowledge about how people of different ages describe their mental health in their own words. An age-specific application of machine learning and artificial intelligence methods may allow for personalised assessment and treatment of mental health 55 , 56 .

Our research question addresses differences in descriptive word responses related to mental health in younger and middle-aged adults. The aim is to investigate potential differences in the semantic representation across the lifespan.

We hypothesise that the semantic representations of mental health differ for younger (i.e., young) and older (i.e., middle-aged) adults (H1), and that these differences are expressed in specific semantic attributes (H2). Given H1 is supported, we hypothesise that different prediction models are required for predicting mental health in younger and older adults (H3). Due to language skills improving with age, we hypothesise that the prediction models may be more accurate for older (H4). Given previous reports on rating scales for measuring mental health in younger and older adults, we hypothesise that the language-based prediction models of older individuals show better mental health than for the younger (H5).

Participants

The study consisted of 883 participants with English as a first language. Seven participants were removed from the analysis as they either failed to follow the instructions, or did not respond to the control questions correctly (e.g., choose the option on the left hand side). The final analysis included 876 participants. 457 participants were recruited from the Mechanical Turk ( www.mturk.com ) platform, and 419 from the Prolific Academic ( https://prolific.co/ ) platform. Half the participants were recruited by screening for MDD or GAD as assessed by using the self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms (SDAS) (Sikström et al., 57 in revision), which is an online version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). The SDAS has been validated by clinicians for MDD (Kappa = 0.76) and for GAD (Kappa = 0.52), for details of this see the Supplementary Information. The other half of participants were recruited without screening; however, they were also assessed by SDAS. Using this measure, 61 (34 younger) participants had MDD alone, 137 (70 younger) had GAD alone, and 259 (139 younger) had both MDD and GAD. Participants younger than the median age of 32.5 were categorised as younger. The age in the given sample ranged from 18 to 70 years ( M = 35.5, SD = 11.9). 538 participants identified as female, 327 as male and 11 as “other gender”. The study lasted approximately 20 min, and participants received USD 4 for their time.

Semantic open-ended questions—Word responses

In total, the participants were asked 11 open-end questions and five rating scales. The open-ended questions can roughly be categorised into topics of; mental health, causes of mental health, positive psychology, and symptoms of mental health. Three open-ended questions were about mental health: “Describe your mental health with descriptive words”, “During the last two weeks, describe in words whether you felt depressed or not”, “During the last two weeks, describe in words whether you have felt worry or not”. They were also asked three questions about the underlying causes of their mental health, depression, and anxiety (“Describe the reason for your mental health/depression/worry in descriptive words). There were two open-ended questions for positive psychology, one on satisfaction (“Overall in your life, describe in words whether you are satisfied or not?”) and harmony (“Overall in your life, describe in words whether you are in harmony with your life or not?”). Eight questions were asked about symptoms (“Describe your sleep/concentration/appetite/energy/self/movement/behaviour/interest with descriptive words)”. The participants were asked to respond using five words for the mental health questions (general, depression, anxiety), three words for the reason questions (general reason, depression reason, anxiety reason), three words for the positive psychology questions (satisfaction, harmony), and two words for the symptom questions. The participants were asked to write one word in each text box, thus the number of boxes matched the number words they were asked to write.

Rating scales

The following rating scales were used to measure depression PHQ-9 49 , anxiety Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7 58 )), satisfaction with life (SWILS 59 , 60 ), and harmony in life (HILS 48 ). SDAS was used to validate the participants’ MDD and GAD diagnoses.

Control items

One control item per rating scale was included, for example “Answer ‘disagree’ on this question”. If the participant failed to answer all the control questions correctly, they were excluded from the analysis. These control questions were essential for ensuring the quality of the dataset by guaranteeing the participant’s focus on the task and to improve the statistical reliability 61 , 62 , 63 .

Demographic inventory

A demographic survey was included, in which the participants were asked about their age and gender. They were also asked to provide their country of origin and first language, as well as a description of their estimated household income. In order to measure the estimated household income, the participants responded to the question “Does the total income of your household allow you to cover your needs?” with either, “Our income does not cover our needs, there are great difficulties” (1) to “Our income covers our needs, we can save” (7).

To participate in the study, a declaration of informed written consent was required. Participants were told that their responses would be anonymised before analysis, and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without needing to give a reason. The questions and rating scales were presented in a random order. Finally, demographic information was collected, and a debrief on the purpose of the study was provided.

The study was reviewed by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (EPN), who determined no ethical approval was needed, as the participants were anonymously recruited and tested (reg. no.: 2020-00730).

Data analyses

The primary aim of the analysis was to study age differences in mental health by looking at the differences in the semantic representations of the descriptive words dependent on their age. The machine learning was trained to the continuous value of age. Methods proposed by Kjell et al. 9 were used and the words were quantified using a latent semantic analysis (LSA) trained to predict the participants’ age with machine learning.

The data analysis was conducted using the online software for statistical analysis of text, SemanticExcel.com. This software includes pre-programmed semantic representations that are generated by the LSA method based on the English version of Google N-gram data ( N = 5). In this method, a co-occurrence matrix is generated first, where each cell includes the frequency of a word in the N-gram. The content of the cells is then normalised by taking the logarithm of the frequency plus one. A semantic representation is then generated by applying a data compression algorithm known as the singular value decomposition (SVD). This generates vectors describing the words in the corpus. Each vector consists of 512 dimensions and is normalised to a length of one. The word responses were added together, and the length was again normalised to one, so that each response to a word question was described by one vector (see Kjell et al. 9 for details). The semantic similarity between two semantic representations can be measured using the cosine of the angle between the vectors, which is calculated as the inner product of the two vectors divided by the product of their magnitudes.

We investigated whether semantic representation depends on age by predicted age from the semantic representation. A variable, called “All texts”, were generated that included the text responses from all the questions for each participant. Age was predicted based on this variable, using the method described in the “Data analysis” section.

Given that the semantic representation differs depending on age, we are interested in studying what attributes are indicative of younger and older people’s description of their mental health (where participants younger than the median age of 32.5 were categorised as young). We used the model generated for the concatenation of all the text that was generated in the analysis of H1, and applied this model to words in the dataset. Then we used two-sided t tests to investigate whether each word was indicative of young or old participants.

We applied the linguist inquire word count (LIWC), a method to assess the how related texts are to certain predefined and manually generated word list 64 . These word lists ( N = 63) represent psychologically relevant categories of words (e.g., emotions, work, stress). The LIWC measures is based on word frequency, and not on word embeddings, and is calculated by counting the percentage of words in each text that is also is presented in each LIWC word list.

Machine learning was used to study whether the semantic representation depended on the age of the participants (for methodological details, see Kjell et al. 9 ). Multiple linear regression ( y = c × x ) was used to predict the age ( y ) using the semantic representation ( x ) as input. The training and test data set was separated by using a 10% leave-out cross-validation procedure. The number of dimensions used in the regression was optimised using a nested cross-validation procedure. The predicted values of age were compared with the empirical data using Pearson correlation ( r ), and the proportion of explained variance ( r 2 ).

Basic statistics

The dataset consisted of a total of 36,396 words, with 4010 unique words. Participants on average generated 42 words (standard deviation 1.4). The mean natural word frequency, as measured by Google N-grams, was 0.00011. The frequency of the words, nor the log frequency of the words, did not correlate with age.

H1: does the semantic representation depend on age?

The results showed that this semantic representation from the All texts variable predicted age (Pearson correlation between predict and empirical age; r = 0.31, r 2 = 0.10, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, prediction models were generated separately for each text variable. The results showed that seven variables were significant, following Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison (sleep, self, affective behaviour, general, energy, harmony, depression), gender without correction for multiple comparison (movement, worry, depression reason, worry reason). Three questions did not correlate with age (appetite general, and interest) (see Table 1 ).

H2: word indicative of younger and older adults

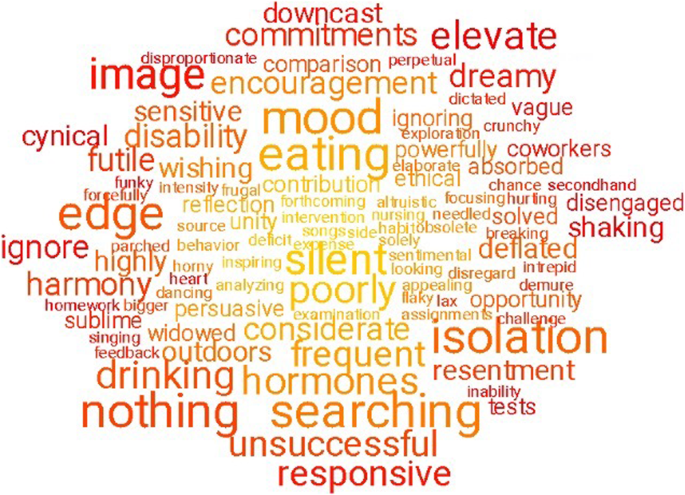

Figure 1 shows a word cloud that summarise the words for all participants (see the footnote for details). Figure 2 shows word clouds indicative of young (left) and old (right) participants and follows the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. These words were manually classified by the authors into ten semantic categories in Table 2A .

Note: The word clouds show 100 words that are the most indicative of the text data compared with a random sample of words in Google N-gram. The words were taken from the concatenation of all text questions “Text all” and compared with a random sample of words in Google N-gram, using the multiple linear regression as specified in the text. All words showed significant Pearson correlations with age following the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, where the colour coding represent the p values. The font size represents the frequency of the words in the data set.

Note: The word clouds show 100 words that are the most indicative of the younger adults (left cloud) and older adults (right cloud) ages. See also footnote to Fig. 1 .

The results show that older people relate their mental health to words related to anxiety (“anxious”, “worry”, etc.), whereas young individuals focus on words related to depression and stress (“sad”, “stressed”, “restless”, “depressed” etc.). Furthermore, younger adults mention issues related to their main activities (e.g., “work”, “school”, “relationships”), whereas the older population uses words more focused on feelings and body states (i.e., “hunger”, “health”, “death”, “crying”, “insomnia”).

Here we used LIWC to investigate which categories are indicative of the younger and the older groups by using the “All text” variable. The LIWC scores in the 63 categories was correlated with age. Table 2B shows the LIWC categories with Pearson correlation coefficients that were significantly different from zero. The “insight” and “cognitive processes” categories correlated positively with age, following the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The “family”, “money”, “discrepancy” and “positive emotion” categories also correlated positively, but without correction for multiple comparisons. The “anxiety”, “friends”, “function words”, “adverbs”, “space”, “assent”, “negative emotion”, “feeling” and “relativity” categories correlated negatively with age, without correction for multiple comparisons.

H3: do younger and older adults require different semantic prediction models?

Here we investigate whether a prediction model of mental health trained on older or younger adults differs from a prediction model applied to younger or and older groups. Two hypotheses are tested here. If the prediction models that are trained and tested on the older group are better at predicting mental health scores than the prediction models that are trained and tested on the younger group, then this supports the idea that the data quality of the old group is better than the younger group (H3). Furthermore, if there is an interaction effect between whether the training and test is made on the same versus different groups, and the older versus younger group, then this supports the hypothesis that different prediction models are required for older versus the younger groups (H2).

Hypothesis 3 is evaluated as follows: the data set was divided using median split criteria, where young participants were aged below 32.5, and an older group equal to or larger than this age. The cross-validation procedure was applied separately to each of the 17 semantic representations (listed in Table 1 ). These semantic representations were trained on each of the four mental health rating scales (i.e., related to depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), harmony (HILS) and satisfaction (SWLS)). 68 prediction models were generated for each of the four groups and the results were evaluated using Pearson correlations between predicted and empirical rating for each of these models.

A repeated measure ANOVA was used to analyse the correlation coefficients, where the factors were age (younger versus older) and testing-training (same versus opposite data). There was a significant age by test–training interaction ( F (1, 67) = 22.2, p < 0.001, Fig. 3 ), indicating that models generated older and younger people depending on whether they were tested on the younger and older participants. This suggests that the different prediction models are required for the younger and older study groups, and Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Note: The y-axis shows the Pearson correlation ( a ) and mean squared error (MSE) ( b ) between predicted and empirical rating scales averaged over all the semantic representations and the rating scales. The training data is divided into younger (left) and older participants (right), using either models trained on the same data set that they were applied on (blue) or trained on the opposite dataset (red).

H4: do older people generate better semantic prediction models?

The ANOVA also shows a significant main effect on age ( F (1, 67) = 196.3, p < 0.001) indicating that ratings scales are better predicted from the semantic representations for the older compared to the younger participants (Fig. 3 ), supporting Hypothesis 4. Thus, accuracy was higher for older participants both when they were evaluated on the older participants and when they were evaluated on the younger participants.

H5: mental health in younger and older adults

Word clouds show words indicative of young and old people (on the x-axis) with low or high for depression (on the y -axis for Fig. 4 ) and low or high anxiety (on the y-axis for Fig. 5 ). Rating scales and semantic measures of mental health were correlated with age (Table 3 ). Rating scales of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) correlated negatively with age following the Bonferroni correction of multiple comparisons. Similar results were found for the corresponding semantic measures, based on training of these rating scales. Finally, we correlated the semantic measures, using the rating scales as covariates. The results show that the semantic measures of depression and anxiety still correlated with age following the corresponding rating scales as covariates.

Note. The word clouds on the left are represent young people and those in the right old people ( r = 0.28). The upper word clouds represent high PHQ-9 scores and the lower word clouds low PHQ-9 scores ( r = 0.76). See also footnote to Fig. 1 .

Note. Same as Fig. 4 , however, the upper word clouds represent high GAD-7 and the lower word clouds low GAD-7 ( r = 0.71).

The aim of this article has been to investigate age differences in mental health using semantic representations generated from descriptive keyword responses to mental health questions. Indeed, the results demonstrated age differences; (1) middle-aged adults describe their mental health differently compared to younger adults; (2) for example, middle-aged adults emphasise depression and loneliness, whereas young adults list anxiety and money; (3) different semantic models are warranted for younger and middle-aged adults; (4) middle-aged participants described their mental health more accurately compared to young participants; (5) middle-aged adults have better mental health than younger adults as measured using semantic measures.

The first and second hypotheses addressed age differences to be found in the semantic representation. The age differences found in specifically semantic open-ended mental health questions is a novel discovery. Our data provides the possibility to summarise age-related themes linked to young and old people, using indicative words (see word cloud in Figs. 1 , 2 , 4 , and 5 ). The young population lists words linking to aspects of social relationships, suggesting these are important for their mental health, while the older adults use words related to health, disease, death, insomnia, sadness and appetite.

Previous reports using more traditional rating scales have found that geriatric depression may emerge from neuronal age-related changes, and sometimes even neurodegenerative disease and cardiovascular changes in the brain 28 . This has given rise to selective rating scales for the elderly, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale 65 . Age differences in reported symptoms may, in part, be the result of generational differences regarding environmental factors such as personal circumstances (e.g., refs. 19 , 20 , 33 , 66 , 67 , 68 ). This explanation could be of particular importance as genetic factors potentially play a greater role in the emergence of depression and anxiety among younger adults 27 , 28 . The semantic open-ended question tool used in the current report may aid, speed up and facilitate proper diagnostic process regardless of a patient’s age in primary care context where expertise in geriatrics is less common.

The third hypothesis assumes that younger and older people may require different semantic prediction models. The present findings suggest that different prediction models are needed for younger and older adults. However, the model most appropriate for middle-aged adults was also better fitted to the data from the younger participants. We propose that the semantic data contains sufficient information for generating reasonable predictions in data from both younger and middle-aged adults. Middle-aged adults often out-perform younger adults in language skills 69 . The elderly has more advanced semantic networks as life experience may, in part, mediate such effects. Future studies focussing on an elderly sample may benefit from the assessment of language skills as a potential moderator of the effects reported herein.

The fourth hypothesis examined how well the semantic representation could predict rating scales depended both on whether the prediction models were based on younger or older adults. The prediction model of several ratings scales yielded higher accuracy when training was based on the older participants. A possible interpretation of this is that middle-aged adults are better at expressing their mental health in free words than younger adults. This finding was true, both when the data was evaluated on the younger and the middle-aged groups. This suggests that the finding cannot be easily explained with the notion that younger adults are less careful when responding to surveys. Sloppy answers would have generated less accurate rating scales, leading to the poorest predictability when applying the young model to the young dataset. In contrast, we found an interaction effect between the age group that the model was trained on and the age group that it was evaluated on, possibly suggesting a difference in semantic models for young and old. Overall, this suggests an interpretation that the older adults generated more informative descriptive keywords of their mental health than their younger counterparts.

Hypothesis 5 states that mental health varies in younger and older adults. According to the present study, older age was associated with lower levels of depression, which aligns with previously reported findings (18–29 years) in Villarroel et al. 70 , who discovered this was the case for both the rating scales and the semantic measures. Interestingly, these findings remain significant for the semantic measures, even after controlling for the effect of more traditional rating scales such as PHQ-9. This may indicate that the semantic measure of depression and anxiety provides additional information to the results of the rating scales.

Language is the natural way for people to communicate their mental state. Nevertheless, the dominating method of measuring psychological constructs are rating scales. A possible reason for this is that language has been difficult to quantify. Recent developments in natural language processing provide unprecedented opportunities for measuring language, with the possible application to mental health and ageing. There are several advantages with QCLA:

Language is the natural way for people to communicate their mental state. Sikström et al. 71 showed that people prefer to describe their mental health using written language responses, as they found this method to be more precise and they are able to elaborate on their responses. Additionally, it was the preferred way to communicate with mental health professionals compared to rating scales. However, when rating scales were preferred, this was due to their ease and speed of use.

Language base measure of mental health has high validity . When mental health is measured using computational methods using words generated to describe mental health, there is evidence of a high correlation with validated scales of depression and anxiety 9 . Furthermore, combining free text and word responses about harmony and satisfaction using transformer-based models demonstrate, to our knowledge, the highest correlation yet between language responses and rating scales, which rivals the theoretical limits based on test–retest data ( r = 0.84, r 2 = 66).

Language can be used to describe mental health constructs . Rating scales are defined by researchers and provide a fixed measure of scale. In contrast, the QCLA approach allows for a data-driven measure of constructs, where data from a specific group of participants (i.e., culture, age, etc.) can be used to describe constructs. This definition can subsequently be visualised in a word cloud. We believe that this provides a more dynamic and natural way of thinking about mental constructs, as the scales of constructs are generated from data in a particular context.

Computational analysis of language can be used for clinical assessments . In combination with machine learning, the semantic mental health constructs can estimate age-specific mental health trajectories. Such algorithms may contribute to more efficient healthcare treatments, or may even serve as a means for notifying healthcare personnel or family members about how to act on subclinical symptoms and how to best support individuals with mental health problems.

Personal assessment . One major strength of the open-ended measure of mental health is that the participants describe their mental health status in their own words. This measure promotes ecological validity to a greater extent, as the responses are closer to their personal communication style and real-life context when compared to traditional rating tools, such as Likert scales, based on fixed items. Furthermore, open-ended questions can counteract the effect of reporting bias when assessing mental health. Self-reported information from traditional questionnaires may contain social desirability biases 72 , which can escalate or underestimate the studied effects of mental health.

The present results should be interpreted in the context of some limitations of QCLA. First, the study suffers from limited generalisability due to the non-random recruitment procedure. Second, another limitation is the associative nature of the current study, which precludes making direct inference about causality due to the lack of experimental control. Third, the sample consisted of a small proportion of old adults. There is a demand for future studies to focus on this age group in order to conclude differences of language usage and AI models to describe mental health in the elderly. Therefore, our results would benefit from future replications to increase the generalisability.

In conclusion, combining latent semantic estimates with machine learning methods may provide new opportunities to discriminate, model, and describe mental health in older and younger adults. Together, these methodologies may provide greater accuracy and precision in the evaluation of mental health across the adult lifespan.

Data availability

The data is not publicly available as it includes sensitive text data; however, requests for the data can be submitted to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The data analysis was conducted using the online software for statistical analysis of text, SemanticExcel that can be accessed on semanticexcel.com 73 . For code, see https://github.com/sverkersikstrom/semanticCode .

WHO. Mental health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1 (2021).

McCracken, L. M., Badinlou, F., Buhrman, M. & Brocki, K. C. Psychological impact of COVID-19 in the Swedish population: depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. Eur. Psychiatry 63 , e81 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mihalopoulos, C. & Vos, T. Cost–effectiveness of preventive interventions for depressive disorders: an overview. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 13 , 237–242 (2013).

Moreira-Almeida, A., Lotufo Neto, F. & Koenig, H. G. Religiousness and mental health: a review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 28 , 242–250 (2006).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 , 2197–2223 (2012).

Eichstaedt, J. C. et al. Facebook language predicts depression in medical records. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 11203–11208 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Greenberg, P. E. et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J. Clin. Psychiatry 64 , 1465–1475 (2003).

Kemper, S., Kynette, D. & Norman, S. in Everyday Memory and Aging (eds West, R. L. & Sinnott, J. D.) 138–152 (Springer, 1992).

Kjell, O. N. E., Kjell, K., Garcia, D. & Sikström, S. Semantic measures: using natural language processing to measure, differentiate, and describe psychological constructs. Psychol. Methods 24 , 92–115 (2019).

Statista. Sweden: share of people with depression, by age 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/960041/share-of-people-diagnosed-with-depression-in-sweden-by-age/ (2021).

Statista. Sweden: share of people with severe anxiety, by age 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/961442/share-of-people-with-severe-anxiety-in-sweden-by-age/ (2021).

Lenze, E. J. et al. Comorbid anxiety disorders in depressed elderly patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 157 , 722–728 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Statista. Share of people diagnosed with depression in Sweden 2022, by age. https://www.statista.com/statistics/961442/share-of-people-with-severe-anxiety-in-sweden-by-age/ (2023).

Remes, O., Brayne, C., Van Der Linde, R. & Lafortune, L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. 6 , e00497 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Su, Y. et al. Specific and cumulative lifetime stressors in the aetiology of major depression: a longitudinal community-based population study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31 , E3 (2022).

Tausczik, Y. R. & Pennebaker, J. W. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 29 , 24–54 (2010).

Article Google Scholar

Xia, W. et al. Association between self-reported depression and risk of all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality. J. Affect. Disord. 299 , 353–358 (2022).

Agerbo, E., Nordentoft, M. & Mortensen, P. B. Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: nested case-control study. BMJ 325 , 74 (2002).

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G. & Nelson, B. D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 52 , 3222–3230 (2021).

Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., Golberstein, E. & Hefner, J. L. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 77 , 534–542 (2007).

Trollor, J. N., Anderson, T. M., Sachdev, P. S., Brodaty, H. & Andrews, G. Age shall not weary them: mental health in the middle-aged and the elderly. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 41 , 581–589 (2007).

Yalin, N., Young, A. H. in Age of Onset of Mental Disorders (eds de Girolamo, G., McGorry, P. & Sartorius, N.) 111–124 (Springer, 2019).

Wu, C., Hsu, L. & Wang, S. Association of depression and diabetes complications and mortality: a population-based cohort study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29 , E96 (2020).

Davison, K. M. et al. Nutritional factors, physical health and immigrant status are associated with anxiety disorders among middle-aged and older adults: findings from baseline data of the Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 1493 (2020).

Bergdahl, J. & Bergdahl, M. Perceived stress in adults: prevalence and association of depression, anxiety and medication in a Swedish population. Stress Health 18 , 235–241 (2002).

Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J. & Learmouth, A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc. 25 , 41–67 (2005).

Gottfries, C. G. Late life depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 251 (Suppl. 2), II57–II61 (2001).

Gottfries, C. G. Is there a difference between elderly and younger patients with regard to the symptomatology and aetiology of depression? Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 13 , S13–S18 (1998).

Johansson, R., Carlbring, P., Heedman, Å., Paxling, B. & Andersson, G. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ 1 , e98 (2013).

Rapp, M. A., Gerstorf, D., Helmchen, H. & Smith, J. Depression predicts mortality in the young old, but not in the oldest old: results from the Berlin Aging Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16 , 844–852 (2008).

De Leo, D. Late-life suicide in an aging world. Nat. Aging 2 , 7–12 (2022).

Ojagbemi, A., Oladeji, B., Abiona, T. & Gureje, O. Suicidal behaviour in old age-results from the Ibadan Study of Ageing. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 1–7 (2013).

Yildirim, H., Işik, K. & Aylaz, R. The effect of anxiety levels of elderly people in quarantine on depression during covid-19 pandemic. Soc. Work Public Health 36 , 194–204 (2021).

Fischer, L. R., Wei, F., Solberg, L. I., Rush, W. A. & Heinrich, R. L. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51 , 1554–1562 (2003).

Gorska-Ciebiada, M., Saryusz-Wolska, M., Ciebiada, M. & Loba, J. Mild cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms in elderly patients with diabetes: prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. J. Diabet. Res. 2014 , 179648 (2014).

Nyqvist, F., Forsman, A. K., Giuntoli, G. & Cattan, M. Social capital as a resource for mental well-being in older people: a systematic review. Aging Mental Health 17 , 394–410 (2013).

Luxton, D. D. in Artificial Intelligence in Behavioral and Mental Health Care (ed. Luxton, D. D.) 1–26 (Academic Press, 2016).

Mathers, C. D. & Loncar, D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3 , e442 (2006).

Mazure, C. M. & Maciejewski, P. K. A model of risk for major depression: effects of life stress and cognitive style vary by age. Depress. Anxiety 17 , 26–33 (2003).

Graham, S. et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 , 116 (2019).

Graham, S. A. & Depp, C. A. Artificial intelligence and risk prediction in geriatric mental health: what happens next? Int. Psychogeriatr. 31 , 921–923 (2019).

Lin, L. Y. et al. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depress. Anxiety 33 , 323–331 (2016).

Lindwall, M., Rennemark, M., Halling, A., Berglund, J. & Hassmén, P. Depression and exercise in elderly men and women: findings from the Swedish national study on aging and care. J. Aging Phys. Activity 15 , 41–55 (2007).

Choudhury, M. de, Counts, S. & Horvitz, E. Social media as a measurement tool of depression in populations. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Web Science Conference 47–56 (ACM, 2013).

D’Alfonso, S. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted online social therapy for youth mental health. Front. Psychol. 8 , 796 (2017).

Landauer, T. K. & Dumais, S. T. A solution to Plato’s problem: the latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychol. Rev. 104 , 211–240 (1997).

Kjell, K., Johnsson, P. & Sikström, S. Freely generated word responses analyzed with artificial intelligence predict self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and worry. Front. Psychol. 12 , 602581 (2021).

Kjell, O. N. E., Daukantaitė, D., Hefferon, K. & Sikström, S. The harmony in life scale complements the satisfaction with life scale: expanding the conceptualization of the cognitive component of subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 126 , 893–919 (2016).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 , 606–613 (2001).

Lovejoy, C. A., Buch, V. & Maruthappu, M. Technology and mental health: the role of artificial intelligence. Eur. Psychiatry 55 , 1–3 (2019).

Löwe, B., Unützer, J., Callahan, C. M., Perkins, A. J. & Kroenke, K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med. Care 42 , 1194–1201 (2004).

Löwe, B. et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care 46 , 266–274 (2008).

Lu, G. et al. Tough times, extraordinary care: a critical assessment of chatbot-based digital mental healthcare solutions for older persons to fight against pandemics like COVID-19. In Proceedings of Sixth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology 735–743 (Springer, 2022).

Chen, I. Y., Szolovits, P. & Ghassemi, M. Can AI help reduce disparities in general medical and mental health care? AMA J. Ethics 21 , E167–E179 (2019).

Horn, R. L. & Weisz, J. R. Can artificial intelligence improve psychotherapy research and practice? Adm. Policy Ment. Health 47 , 852–855 (2020).

Jha, I. P., Awasthi, R., Kumar, A., Kumar, V. & Sethi, T. Learning the mental health impact of COVID-19 in the United States with explainable artificial intelligence. JMIR Ment. Health 8 , e25097 (2021).

Sikström S., Kjell O. (in revision). Language Analyzed by Computational Methods Predicts Depression Episodes More Accurately than Rating Scales Alone.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166 , 1092–1097 (2006).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49 , 71–75 (1985).

Erickson, K. I., Leckie, R. L. & Weinstein, A. M. Physical activity, fitness, and gray matter volume. Neurobiol. Aging 35 (Suppl. 2), S20–S28 (2014).

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T. & Davidenko, N. Instructional manipulation checks: detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 45 , 867–872 (2009).

O’Riley, A. A. & Fiske, A. Emphasis on autonomy and propensity for suicidal behavior in younger and older adults. Suicide Life-threatening Behav. 42 , 394–404 (2012).

Pearson, S. et al. Depression and insulin resistance: cross-sectional associations in young adults. Diabetes Care 33 , 1128–1133 (2010).

Pennebaker, J. W. Using computer analyses to identify language style and aggressive intent: the secret life of function words. Dyn. Asymmetric Conflict 4 , 92–102 (2011).

Yesavage, J. A. et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res . 17 , 37–49 (1982).

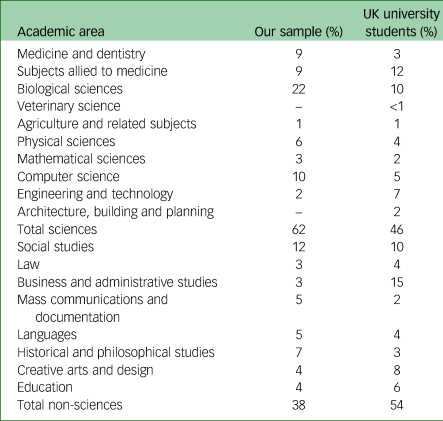

Virgincar, A., Doherty, S. & Siriwardhana, C. The impact of forced migration on the mental health of the elderly: a scoping review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 28 , 889–896 (2016).