Evolutionary thinking: a new perspective on how our brains control behavior takes evolution into account

by Amanda Parker | Jul 22, 2021 | Research

We watch a ball as it falls into our glove. We hear a strange sound in another part of the house and listen intently. In neuroscience, the act of narrowing our senses in response to an environmental event is called “attention,” and it is understood that when we attend to a stimulus, we lose the ability to focus on other surrounding inputs.

“The explanation that the neuroscience community gives for this—the textbook answer—is that we have limited cognitive mechanisms,” said W. Martin Usrey, Professor of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior and Neurology at UC Davis, “and we have to distribute those to certain areas because there is an inherent limitation to what the cortex can do.”

But is the cortex itself inherently limited? And if so, why would this be? Assuming we evolve to better survive our environments, wouldn’t it be more useful, for example, for a mouse to be able to focus on both the owl in the sky and the rustling in the grass at the same time and with equal power?

These questions are at the heart of a perspective published on July 22 in Neuron by Usrey and University of Chicago Maurice Goldblatt Professor of Neurobiology, S. Murray Sherman.

“With the big cerebral cortex that we have, one question that’s always bothered Murray and me is why we can’t heighten our awareness of everything,” said Usrey. “The cortex has this incredible computational power. Why can’t all areas be heightened at once? Why diminish one region so that another area can be enhanced?”

Now, Sherman and Usrey argue that our inability to focus our attention on all stimuli at once is not due to a limitation in the cortex itself, but is a product of the physical constraints in which it must operate. In other words, Sherman and Usrey suggest that attention as we know it is a direct consequence of the way our brain’s structure has evolved.

The cortex and evolution

In all mammals, the brain is composed of numerous components that reflect its evolutionary heritage. The most recent component is the cerebral cortex, which is particularly large and well-developed in humans. Exceptionally intricate, the cortex contains tens of billions of interconnected neurons and underlies all our conscious perceptions and abstract thought. Importantly, the cortex functions by interacting and cooperating with the other, evolutionarily older components.

“It’s almost like you can see the history, like geologists see when they look at layers of sediment,” described Sherman. “In the brain, most of the old circuits are still there and functioning—you add things on, but you don’t throw away the old stuff.”

In other words, as the cortex emerged, the older structures of our brain did not fall away. Instead, they remained, and the cortex evolved to work with them.

“The cortex, which is the pinnacle of our evolution as far as the brain is concerned, doesn’t generally have direct access to our motor neurons to control behavior,” said Sherman. “It has to go through all these old circuits. And in doing that, it has to play nice with all the old circuits that are trying to control behavior at the same time.”

To affect behavior, the cortex must send signals through the older subcortical regions. This represents a bottleneck in the flow of signals originating in the cortex, and these subcortical structures could not function properly if all cortical area simultaneously tried to control them.

“If all cortical areas tried to take control of these subcortical structures without anything to judge what’s best, you’d have utter chaos,” said Sherman.

Not only are there physical constraints to funneling large amounts of information through smaller regions, but without any prioritization of signals, we might receive contradictory information.

“Imagine if your visual cortical areas tell you to go left and the auditory areas tell you to go right,” explained Sherman.

What we call attention, then, Sherman and Usrey suggest, is the prioritization the brain must employ to permit only appropriate cortical areas to dominate subcortical routes to behavior. And this prioritization is required due to the very process of evolution that produced the cortex.

“It’s the filtering,” said Sherman, “to determine which cortical areas or subcortical areas at any given time are going to take control of behavior, which we now think we recognize as attention.”

New ways of thinking

If attention as we know it is a product of our brain’s structural evolution, as Sherman and Usrey argue, why did it evolve this way? Why didn’t we evolve to be able to focus on all environmental stimuli at once?

“An engineer building something as complex as the brain might go through a number of different stages, said Sherman, “and when a better way of doing something is developed, the old way might be thrown out. But evolution doesn’t work that way.”

As Sherman and Usrey say in their article, “evolution is messy.” It doesn’t scrap the whole thing and start fresh when things get complicated. Instead, we change by building upon and adapting what already exists. Although we are always evolving to become better suited for our environments, that evolution is constrained by our current structure and functionality.

In the case of the brain, subcortical structures had already developed circuits for complex motor control. When the cortex subsequently evolved, instead of reproducing all the needed neural circuitry, it took advantage of what was already there.

Attention is traditionally seen as a purely cortical mechanism, which is why the “textbook answer” for why we must limit our focus has been that our cortex must have a limited supply of resources to devote. But Sherman and Usrey argue that, because of the context in which it evolved, the cortex does not function on its own.

“We hope to change the way people think about cortical functioning, writ large,” said Sherman. “If you want to understand the brain, I assert you must take evolution into consideration.”

By Amanda Parker, PhD

All Categories

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

20 Evolutionary Psychology

Ben Jeffares, postdoctoral fellow, Department of Philosophy, Victoria University of Wellington

Kim Sterelny School of Philosophy, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, Australia

- Published: 01 May 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The article presents several models of evolutionary psychology. Nativist evolutionary psychology is built around a most important insight that ordinary human decision-making has a high cognitive load. Evolutionary nativists defend a modular solution to the problem of information load on human decision-making. Human minds comprises of special purpose cognitive devices or modules. One of the modules is a language module, a module for interpreting the thoughts and intentions of others, another is a ‘naive physics’ module for causal reasoning about sticks, stones, and similar inanimate objects, a natural history module for ecological decisions, and a social exchange module for monitoring economic interactions with peers. These modules evolved in response to the distinctive, independent, and recurring problems faced by the ancestors. Domain specific modules handle information about human language, human minds, inanimate causal interactions, the biological world, and other constant adaptive demands faced by human ancestors. Nativist evolutionary psychologists have turned to moral decision making, arguing that cross-cultural moral judgments are invariant in an unexpected way. Natural selection can build and equip a special purpose module only if the information an agent needs to know is stable over evolutionary time. Automatized skills are an alternative means of coping with high-load problems. These skills are phenomenologically rather like modules, but they have very different developmental and evolutionary histories.

At its broadest, evolutionary psychology is the study of the evolved mind. It is a branch of cognitive science that takes the evolutionary history—the etiology—of minds as an important component of a complete psychology. Explaining the origins of our cognitive capacities is an important project in its own right, but many evolutionary psychologists think that an evolutionary framework helpfully guides investigations into the cognitive processes of living humans. This chapter will first sketch the historical background against which evolutionary psychology emerged, and then look at two contrasting views of evolved minds. In Section 2 , we examine the view that sees minds as collections of evolved task-specific modules: nativist evolutionary psychology. In Section 3 , we present the alternative derived directly from evolutionary theory and developmental psychology, a view that takes the role of culture as fundamental. While the truth will lie somewhere between these two views, developing and testing hypotheses will require evidence from the archaeological record. We examine that record and its role in Section 4 . Section 5 outlines the implications for cognitive science and the philosophy of mind.

1. Evolutionary Models of Mind and Behavior

The history of evolutionary psychology is as deep as that of serious evolutionary theory itself: both began with Darwin, and others continued his pioneering work on the evolution of emotion and its expression (see especially Richards 1987 ). However, evolutionary thinking in psychology essentially disappeared with the development of behaviorism. Moreover, the study of behavior was not yet fully established in zoology. This extinction was not local: the evolution of human cognition disappeared as a topic from serious science. Within the biological sciences, evolutionary psychology only returned as a side effect of the establishment of an evolutionary biology of behavior, and that development took much of the century. Early ethology, the study of animal behavior, did not focus on phenomena that extended naturally to human decision making. Many of the early paradigms were of invariant, quite rigid, often ritualized action patterns. Many examples were drawn from mating and brood care of birds, and experiments were typically designed to show that even quite complex and highly structured act sequences could be controlled by simple releasing stimuli. Action was adaptive despite its simple, cue-driven relation to the world, not because of its cognitive complexity (see, e.g., Tinbergen 1960 ). There was some speculation within ethology on how human action should be understood within this framework (see Lorenz 1966 ; Lorenz 1977 ), but these speculations were not integrated with the Tinbergen-Lorenz experimental program (Burkhardt 2005 ). Starved of models of cognitive evolution, the study of human evolution concentrated on changes in morphology and behavior. Thus much of the work of archaeologists and physical anthropologists consisted of chronicling the developments leading to full human behavior, with little informed theorizing about the underlying cognitive mechanisms. When archaeologists did speculate about human cognitive evolution, it was more mythical than methodical (Landau 1984 ).

The connections to human behavior began to be sketched out, as behavioral ecology began to replace ethology (see, e.g., Hamilton 1975 ). Behavioral ecology had a much greater emphasis on formal evolutionary modeling (including sexual selection and kin selection), and its focus shifted to social and sexual decision making. These connections became explicit in the final chapter of Wilson's synthetic overview, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975), and his own subsequent and much less cautious work (1978; Lumsden and Wilson 1981 ). Wilsonian sociobiology was not explicitly a version of evolutionary psychology. Its focus was on supposedly typical forms of human social behavior : those to do with mate choice, child care, intergroup relations and the like. The Wilsonians argued that (for example) both hostility toward strangers and male sexual promiscuity are adaptations. But, while the explicit focus was on action, the Wilsonian program was implicitly committed to strong and probably implausible claims about the psychological mechanisms that generated these distinctive patterns of action. For if xenophobia, say, is an adaptation, then it must be a trait whose occurrence and intensity varies independently of the rest of an individual's behavioral phenotype (for otherwise individuals will not differ just in their xenophobic tendencies (Lewontin 1978 )). For xenophobia to be independent of other behavioral dispositions, the action pattern in question must be generated by an autonomous mechanism (Sterelny 1999 ). Moreover, this propensity must typically be inherited by an agent's offspring.

This picture of the relations between action and cognition is implausibly crude. An agent's disposition to act is dependent not just on the external environment but on the rest of one's cognitive phenotype: on motivation, emotion, and belief. So on these grounds (and others), the Wilsonian program was subject to brutal criticism (Kitcher 1985 ), and has essentially vanished, despite the title of Alcock's 2001 work, The Triumph of Sociobiology .

Even so, humans are animals, and consequently many of the critics accepted that there must be an account of the evolution of human cognition and behavior that would illuminate our current ways of life and social organization (e.g., Kitcher 2001 ; although for a sceptic, see Lewontin 1998 ). Consequently, Wilsonian sociobiology did not vanish without issue. Perhaps its most direct descendant is human behavioral ecology, which maintains the focus on behavior, and like the Wilson program, has imported most of its models from the behavioral ecology of nonhuman animals. Human behavioral ecology focuses on core, fitness-determining decision making (foraging, birth spacing, food sharing, and the like), largely in traditional environments in which the supposed problem of “adaptive lag” (of agents behaving maladaptively because they find themselves in evolutionarily novel environments) is minimized. Human behavioral ecology is focused on individual behavior, and emphasizes the adaptive flexibility of human action: the background assumption is that humans make adaptive choices in just about any social environment. So human behavioral ecologists do not echo Wilsonian sociobiology's claims about genetic constraints on individual action or human social organization, and hence it has not raised the same political suspicions as its predecessor (for reviews of human behavioral ecology that also compare it to other approaches, see Winterhalder and Smith 2000 ; Smith, Borgerhoff-Mulder, and Hill 2001 ; Laland and Brown 2002 ; Smith and Winterhalder 2003 ).

Human behavioral ecology, like Wilsonian sociobiology, says nothing explicitly about our cognitive mechanisms. Rather, it assumes that those mechanisms allow us to assess the causal structure of our environment and to recognize the likely consequences of our actions. And it presupposes that our subjective utilities track fitness. The outcomes we prefer increase fitness, while those we avoid reduce fitness. In contrast, evolutionary psychologists of sundry varieties focus on cognition and its evolution. There is plenty of disagreement among their ranks, but perhaps the most fundamental divide is on how to incorporate culture within an evolutionary framework. One group, the nativist evolutionary psychologists, minimize the role of culture within human life. While we learn much from others, and while that culturally acquired information is essential for a human life, what we learn is constrained by the innate adaptations of the mind. Just as the space of possible languages is constrained by an innate language faculty, so too the space of possible human mating systems, the space of possible folk psychologies, the space of possible folk biologies, and so forth are constrained by innate specializations. Cultural variation is constrained, and individual acquisition within that constrained space is enhanced, by our adapted mind. This model of evolutionary psychology has seized most of the headlines, and it will be our focus in Section 2 . But we will go on to show that it is not the only model of evolutionary psychology: there is a family of alternative models according to which our minds are profoundly shaped by culture and by cultural transmission—alternatives we discuss in Section 3 . Methodological issues are the focus of our final section, for it is not obvious that the historical record is rich enough to discriminate between the various alternative models of cognitive evolution.

2. Evolutionary Nativism

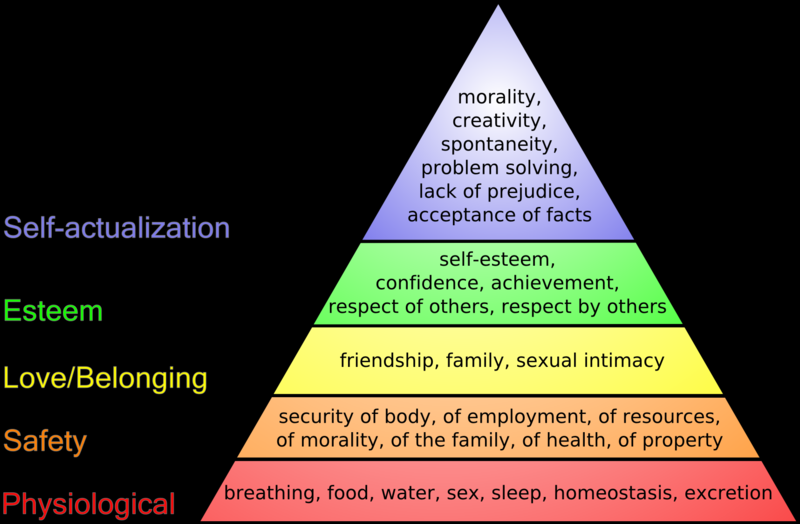

Nativist evolutionary psychology is built around a most important insight: ordinary human decision making has a high cognitive load . To make good decisions, agents must be sensitive to complex, subtle features of their environment. The information-hungry nature of human action first became apparent in thinking about language. Language makes intensive demands on memory. The different parties to a conversation must remember who said what to whom. It also makes intensive demands on attention. In a conversation, you must do more than recall what has been said: you must monitor and act on the effects on your utterances and those of others. You need to be alert to the signs that the conversation is going wrong. Moreover, you will often have to do this while also attending to your physical and social world, for often the point of talking is to coordinate joint action: linguistic acts interface, and are smoothly integrated, with the rest of our lives. Famously, Chomskian linguists argued that learning a first language poses an even more formidable challenge. Every child masters a complex, subtle, intricate set of rules (and a huge vocabulary). Children do so (the argument goes) on the basis of impoverished, perhaps even misleading data (this argument is expounded most brilliantly in Pinker 1994 ; for a sceptical response, see Cowie 1998 ). No wonder then that language is at the core of the cognitive revolution in psychology and is the model evolutionary nativists use in their attempts to synthesize psychology and evolutionary theory.

For, crucially, the point about the cognitive load on language use holds for human decision making generally. Hence much cognitive psychology—psychology with no professional interest in evolution—has followed Chomskian linguistics into some form of nativism: working with the idea that the human mind is specifically prewired for particular learning tasks. We are cognitively competent in the face of difficult challenges because our minds are specifically structured to meet these challenges. Nativist evolutionary psychology gives this idea of prewiring an evolutionary interpretation. Think, for example, of a social negotiation: deciding who does what in organizing a conference. The participants in such a negotiation must estimate what needs to be done and how the total package can be divided into subtasks. They must understand the relative weight of each chore, and the skill set, reliability, and motivation of their partners. Each must be sensitive to the dynamics of the negotiation itself; they must read one another's moods and intentions. We routinely manage such mixes of mindreading, social negotiation and planning, but that should not blind us to the high cognitive load of such achievements. The evolutionary nativist solution to the cognitive load problem is to appeal to special purpose adaptations. Just as we are specifically adapted for language, so too are we specifically adapted to understand our biological and social environment (Atran 1990 , 1998 ). Our minds are ensembles of special purpose devices, each of which is innately equipped to solve the information-hungry but repeated and predictable problems of human life (the classic source for this view is Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby 1992 ; perhaps its most persuasive articulation is Pinker 1997 ).

In short, evolutionary nativists defend a modular solution to the problem of information load on human decision making. On this view, human minds are ensembles of special purpose cognitive devices: modules. We have a language module; a module for interpreting the thoughts and intentions of others; a “naive physics” module for causal reasoning about sticks, stones, and similar inanimate objects; a natural history module for ecological decisions; a social exchange module for monitoring economic interactions with our peers; and so on. The human mind is not an immensely powerful general-purpose problem-solving engine: it is an integrated array of devices, each of which solves a particular type of problem with remarkable efficiency.

These modules evolved in response to the distinctive, independent, and recurring problems our ancestors faced in their lives as Pleistocene foragers. At some stage in human evolutionary history, language became crucial to human life. In such an environment, the barely lingual would have been under an ever-increasing handicap; hence, there would have been selection for an innate language competence. The lives of human ancestors also depended on cautious cooperation—cautious because free riding would have been an ever-present temptation, and so our ancestors needed to monitor social exchange and to interpret other agents as agents. Our ancestors lived technologically enhanced foraging lives: they needed to understand the causal properties of the raw materials from which they fashioned their tools, and the nature of their biological targets. And so we have folk physics and folk biology modules. And so on.

In this view of cognition, and of cognitive evolution, we cope with the information-processing demands on human life because natural selection has pre-equipped us with both the crucial information and the task-specific processing capabilities we need. Domain specific modules handle information about human language, human minds, inanimate causal interactions, the biological world, and other constant adaptive demands faced by human ancestors (for a recent overview, see Barrett and Kurzban 2006 ).

So the empirical program of nativist evolutionary psychologists is, first, to use their model of the evolutionary demands on human cognition to develop hypotheses about the set of specific adaptations we should expect to find. Second, they use the methods of experimental cognitive psychology to test the idea that we have distinctive cognitive skills in the domains so identified. If such skills are found, this is treated as a confirmation of the evolutionary model. The results of this empirical program are very controversial. Evolutionary psychologists are very upbeat. Most famously, John Tooby and Leda Cosmides think they have evidence of distinctive reasoning about social interaction and norm violation (Cosmides and Tooby 1992 ). If the so-called “Wason selection task” is formulated as a problem of policing norm violation, subjects do well. Given logically equivalent tasks with no similar social content, subjects perform poorly. There has also been a good deal of experimental work on mate preference, the results of which have been taken to confirm nativist predictions that males and females have been under divergent selection regimes and look for different qualities in mates (Buss 1994 , 2006 ). As we see it, recent work has undermined Buss's picture in two ways. First, this work highlights the similarities between male and female choice (for example, both sexes weigh intelligence and kindness heavily), and second, mate choice is frequently that expected by behavioral ecologists, demonstrating the adaptive flexibility of mate choice given diverse local conditions (Gangestad and Simpson 2000 ; Fletcher 2002 ; Fletcher and Stenswick 2003 ; Simpson and Orina 2003 ).

As well as experimental work on adults, nativist evolutionary psychologists also take work in developmental psychology seriously, for innate capacities are expected to have a typical developmental signature, namely, early and uniform appearance. Nativist evolutionary psychologists are especially impressed by evidence of very early theory of mind skills in young toddlers, the development of so-called “theory of mind” capacities (Leslie 2000 ; Leslie, Friedman, and German 2004 ; Leslie 2005 ). Recent studies involve a “differential looking time” test. Subjects look longer at situations that surprise them, so the trick is to devise scenarios that would be surprising if and only if the subject understands mental states and their connections to action. Using these tasks, some developmental psychologists argue that very young children have theory of mind capacities (Gergely and Csibra 2003 ; Tomasello et al. 2005 ; Tomasello and Carpenter 2007 ). Indeed, some very recent work seems to show that children between two and three seem to pass nonverbal tests of sophisticated theory of mind capacities, namely understanding the role of false belief (Baillargeon et al. 2010 ). That said, these results are difficult to interpret for we need a robust account of why their capacity to understand false belief is masked in some tasks and not others.

Most recently, nativist evolutionary psychologists have turned to moral decision making, arguing that cross-cultural moral judgments are invariant in a subtle and unexpected way. Agents think foreseen but unintended consequences are morally different from foreseen and intended ones: the first, but not the second, can be tolerated as a price paid for avoiding a greater evil (Hauser 2006 ). There is a good deal of controversy about the robustness of these results and their interpretation. David Buller, in particular, is very sceptical (2005), and his scepticism has provoked a very hostile response (see, e.g., Machery and Barrett 2006 ). Even some of those broadly sympathetic to the nativist program have doubts about the flagship case of social exchange (see Sperber and Girotto 2003 ; in response see Cosmides et al. 2005 ; Cosmides and Tooby 2005 ).

We do not expect this debate to be over any time soon. We too are sceptical of the nativist program, but for different reasons. Natural selection can build and equip a special purpose module only if the information an agent needs to know is stable over evolutionary time. That sometimes happens: the causal properties of sticks, stones, and bones do not change, hence a naive physics module could well be built into human heads. So there is something to the nativist view, but it is not a general solution to the explanatory challenge posed by our capacities to cope with high cognitive-load problems for many features of human environments have not been stable. The social, physical, and cognitive environments in which we act have been extraordinarily varied. Yet we cope: that is a part of the explanation of our cosmopolitan distribution. Social worlds vary in size, family structure, economic basis, technological elaboration, extent and kinds of social hierarchy, and division of labor. They have varied physically and biologically: the world has changed very dramatically in its physical and biological state over the last few hundred thousand years as it has cycled through ice ages. Indeed, Richard Potts has argued that human evolution has been mainly shaped by increasing, and increasingly intense, climatic variability (1996). Moreover, we are now spread over virtually the whole of the globe. The variability of human environments is especially evident when we bear in mind the fact that we are incorrigible and pervasive ecological engineers: change comes not just from migration and external disturbance, but from our relentless habit of modifying our physical, biological, and social circumstances. Tools, clothes, shelter, fire, and agriculture have changed the world we live in. But so has language, ritual, and extended childhoods in which children live with and learn from their family. If many salient features of human worlds vary across time and space, information about those features cannot be engineered into human minds by natural selection. Our ability to act aptly in such worlds cannot depend on innate modules.

If the nativists are right, and general learning and problem-solving capacities are not powerful enough to solve high-load problems rapidly and accurately, we should suffer from the shock of the new far more brutally than we do. Minds adapted for mid-latitude foraging economies and small-scale social lives should short out when confronted with the cognitive and emotional challenges of (say) New York subways or Mexico City traffic. There are indeed maladaptations of modernity. Favored examples are the diseases of obesity and the restriction of family size by the urban middle class. But we are not, it seems, nearly as hopeless as we should be. Nativist evolutionary psychology seems to predict that the closer an agent's environment is to that of our ancient foraging world, the more reliably adaptive the agent's action should be. But the myth of primitive harmony is indeed a myth: there is no evidence that contemporary small-scale foraging peoples manage their lives more adaptively than, say, urban Mexicans (for a blackly comic catalog of human disaster in traditional societies, see Edgerton 1992 ; for nativist responses to this apparent paradox, see Sperber 1996 ; Carruthers 2006 ).

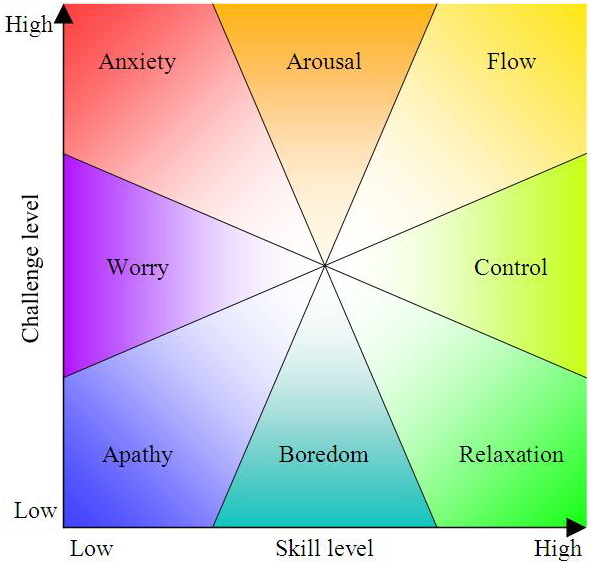

3. Alternative Models of Evolutionary Psychology

So the situation as we see it is this: The evolutionary nativists are right to think that many routine decision-making situations have a high cognitive load, but they are wrong to think that high-load problems can be confronted successfully only by agents with innately specified, special purpose cognitive capacities. Automatized skills are an alternative means of coping with high-load problems. Automatized skills are phenomenologically rather like modules, but they have very different developmental and evolutionary histories. Skills are slowly built, but once built they are enduring and automatic. As with the nativist psychologist's modules, once they are up and running, they are fast, reliable, automatic, and domain specific. Chess players cannot help but see a chess board and its pieces as a chess position. A birder cannot help but see a particular underwing pattern as a whistling kite. Physical skills such as riding a bicycle might be attenuated by muscular disuse, but they are not forgotten. What is more, automatized skills are often adaptive: they equip agents for the specific features of their environment. The hard-won skills of natural history and bushcraft that enable a forager to move silently, see much that is invisible to others, and find his or her way are plainly critical to survival. So too are the skills of observation, anticipation, and coordination that allow a taxi driver to negotiate the chaos that is Mexico City. But such skills are built into no one's genes. A forager's skills will be very different in an Australian aboriginal in the Pilbara, an Ache hunter-gatherer in a central American rainforest, or an Inuit seal hunter.

Such skills are not only phenomenologically similar to modules, they are also inheritable, for they can be accumulated and transmitted culturally. Children resemble their parents not just because they have inherited their parents’ genes, but also because they have inherited their parent's informational resources (and sometimes that of their parents’ social partners). Cultural transmission is reliable and of high fidelity in part because we are genetically adapted to pump information from the prior generation (Tomasello 1999 ; Alvard 2003 ; Gergely and Csibra 2005 ; Csibra and Gergely 2006 ), but also because we structure the learning environment of the next generation. We construct not just our own niche, but that of the next generation. In part, we build not just their physical and biological world, but their learning environment (Avital and Jablonka 2000 ; Laland et al. 2000 ; Sterelny 2003 , 2006 ). So there is a family of alternative models of evolutionary psychology (see, e.g., Tomasello 1999 ; Heyes 2003 ; Sterelny 2003 ; Jablonka and Lamb 2005 ; Richerson and Boyd 2005 ; Laland 2007 ). These models emphasize four factors that structure human cognition. These are: (1) Cultural inheritance: we have complex cognitive adaptations—for example, the natural history competences of foragers—that are built by cumulative selection on culturally transmitted variation. (2) We are adapted for cultural learning: Michael Tomasello, for example, thinks that joint attention is a key adaptation underpinning human cultural learning, allowing individuals to monitor (and learn from) the social and technical activities of others. (3) Human cognition is plastic: very different phenotypes emerge from the interaction between environments and inherited resources. (4) We develop in structured learning environments. We now sketch one model from this family (based on Sterelny 2003 ), and then close with the difficult methodological problem: Can alternative models be tested? Is the historical record rich enough to impose serious evidential constraints on theories of human cognitive evolution?

We begin by contrasting human and chimp culture. Chimpanzee material culture is quite varied, but it is also quite rudimentary: there is no evidence that any chimp tools exist in their current form as the result of a cycle of discovery and improvement (Laland and Galef 2009 ). Cycles of discovery and improvement depend on reliable and high fidelity transmission between generations. If an innovative australopithecine discovers a more efficient way of flaking stone tools, without reliable social transmission, the technique will disappear at the death of its discoverer. Imitation plays little role in chimp social learning, and they lack language. So chimp social learning is not adapted to a communal data base and a communal skill base that can be ratcheted up over the generations. But for the last couple hundred thousand years the human environment has been the result of a ratchet effect in operation: a cycle in which an innovation is made, becomes standard for the group, and it then becomes a basis for further innovation. So material culture and informational culture is built by cumulative improvements. This process of cumulative improvement depends in part on cognitive adaptations for cultural learning: adaptations that make human children soak up the skills and information of the adults with whom they grow up, but it also depends upon information pooling. Information pooling makes the flow of information across generations much more reliable, as children have access to information controlled by the group as a whole. Moreover, information pooling allows an innovation made by any individual in the group to spread through the group as a whole, and that innovation is then available as a foundation for further improvement. To the extent that information pooling is crucial to the reliable and high fidelity transmission of information across generations, human cooperation and human capacities for high-load decision making are intimately linked.

High fidelity cultural transmission is effective because children are adapted to receive this information, and because information pooling ensures that it is sent reliably, with plenty of redundancy (see Csibra and Gergely 2006 , Gergely and Csibra 2005 , Gergely et al. 2007 ); for archaeological support, see Sterelny ( 2011 ) and the citations therein). But it also depends on niche construction. We have become cosmopolitan in part because we have learned to take our world with us. We have progressively modified our own physical, social, and biological environment. Tools, clothes, shelters have changed the worlds we live in. But we have modified our learning environment too: reshaping both the information available to children and the access they have to that information. Learning is scaffolded in many ways. Ecological tools have informational side effects. A fish trap can be used as a template for making more fish traps; a toolmaker can be immersed in a social world where environmentally salient tools, tool manufacture, and tool use are ubiquitous. Skills associated with manufacture are demonstrated in a form suited for learning. Completed and partially completed artifacts are used as teaching props. Practice is supervised and corrected. The decomposition of a skill into its components is made obvious; subtle elements will often be exaggerated, slowed down, or repeated. Moreover, skills are often taught in an optimal sequence so that one forms a platform for the next. This makes it possible to learn the otherwise unlearnable. Artifacts also act as props in games, rituals, and storytelling, providing opportunities for motor skill acquisition by novice users, and opportunities for an individual to understand artifact deployment within highly coordinated group activities well before their contribution is crucial to group success.

On this view, the organization of human learning environments, cultural variation in those learning environments, and human developmental plasticity interact to provide a range of human cognitive phenotypes. Humans do not have a single cognitive design; cognitive skills are a fundamental part of our cognitive systems, and these in turn are contingent on our environment. Only highly structured developmental environments make the acquisition of complex automatized skills possible. These skills are phenomenologically like modules: they are fast, automatic, and typically adaptive. Skilled drivers make life-and-death decisions without skipping a conversational beat based on quite subtle information about the physical conditions and the behavior of other drivers. But these skills are developmentally very different from modules: they develop slowly, with much practice and instruction, and with much variation both with and across cultures.

Dan Dennett has suggested a more radical version of the idea that differences in technology result in profoundly different developmental trajectories. He has proposed that our capacity to represent and reason about our own thoughts and those of others depends on prior exposure to public representations. Agents in a culture with enduring public symbols inherit an ability to make those symbols themselves objects of perception and to manipulate them voluntarily. Imagine a group of friends drawing a sketch map in the sand to coordinate a hike. Those representations are voluntary and planned. Dennett suggests that we first learn to think about thoughts by thinking about these public representations. In drafting and altering a sketch map, we are using cognitive skills that are already available—they are just being switched to a new target. Moreover, manipulation of such a public representation makes fewer demands on memory; no one has to remember where on the map the camp site is represented. Rich metarepresentational capacities are developmentally scaffolded by an initial stage in which public representations are objects of thought and action (Dennett 2000 ); Andy Clark develops a similar picture in his 2002 work.

Nativist evolutionary psychologists think we have a “folk psychology” module for we are very good at estimating what others will think and do. If an arrangement goes wrong, and a friend fails to turn up to a meeting at a café, we are quite good at working how to recoordinate on the fly. We predict others’ responses, even taking into account the fact that their response will depend on what they expect us to do. The nativist explanation of this remarkable capacity is that we have an innate module equipped with a good model of human thought and decision. There is an alternative: we interpret others as the result of having a biologically prepared, culturally amplified, automated skill. That skill is acquired very reliably, both because humans of one generation engineer the learning environment of the next generation, and because the acquisition of this skill is supported by perceptual systems tuned to relevant cues. We are sensitive to facial expression; signs of affect in voice, posture, and movement; the behavioral signatures that distinguish between intentional and accidental action, and the like. These systems make the right aspects of behavior, voice, posture, and facial expression salient to us. They make learning easier because we are apt to notice the right things in other agents. The acquisition of interpretive skills depends on perceptual preadaptation and individual exploration in a socially structured learning environment.

In addition to these perceptual preadaptations, children live in an environment soaked with agents interpreting one another. They are exposed both to third party interpretation, and to others interpreting them. Much of this interpretation is linguistic but there are also contingent interactions in which the child is treated as an agent: imitation games, joint attention, and joint play. It helps that children interact with their developing peers for they have not yet gained the abilities to mask their emotions, inhibit their desires, and suppress their beliefs. Interacting with more transparent agents simplifies the problem of inferring from an action to its psychological root. In adults, the connection between psychological state and action can be very complex and indirect. How could anyone learn that action depends on an agent's beliefs and goals, when those are so hidden? But when children interact with their peers, the connections between desire, emotion, and action will often be very direct. Children are less good at concealing overt signs of their emotion than adults, and less good at resisting the urge to act on those emotions. As three- and four-year-olds are making crucial developmental transitions, this lack of inhibition of their peers simplifies their epistemic environment.

Parents make the interpretive task easier by offering models of their own and their children's actions: they often rehearse interpretations of both their own and their children's actions. Likewise, children's narrative stories are full of simplified and explicit interpretative examples. Language itself scaffolds the acquisition of interpretative capacities by supplying a premade set of interpretative tools. Thus linguistic labels help make differences salient (Peterson and Siegal 1999 ). Finally, focusing on the concept of belief can make the task of acquiring theory of mind seem even more challenging than it really is. Belief and preference are often hidden, having no overt and distinctive behavioral signature. But many folk psychological concepts—those for sensations and emotions—do have a regular behavioral signature, and these scaffold the acquisition of less behaviorally overt concepts by making available easier examples of inner causes of outer actions (Sterelny forthcoming).

The position outlined agrees with the nativists’ scepticism about the power of general purpose learning mechanisms. Nativists think evolution has solved this problem by reducing the amount we need to learn. But the alternative model suggests that evolution has found a different and more flexible strategy: the power of general purpose learning has been augmented by optimizing the learning environment. No doubt the cognitive capacities involved in understanding others would be very hard to acquire by our own unaided efforts, but we do not have to acquire them that way. Our environments have been informationally engineered to circumvent the cognitive limits of individuals on their own. Alternatives to nativist evolutionary psychology present a model of how a fast, automatic, and sophisticated cognitive specialization can develop without it depending on specific innate structures.

Of course many hybrids are possible. Perhaps folk psychology is acquired both through a richly structured environment together with some minimal but specific prewiring: a view that might be very plausible, if the evidence for very early acquisition is further supported. In any case, it is likely that the truth will lie somewhere between the two extremes of nativism and niche construction. The alternatives will be refined and tested within the laboratories of cognitive scientists. But that is not the only evidence that is relevant, for if modules and automatized skills are phenomenologically similar, then one way of choosing between the two hypotheses is the rate of change in behaviors over time. Niche construction and other culture and learning based models predict that human behavior and social organization should be highly variable in space and time (since cultural variation is not constrained by innate modules). Moreover, our distinctive cognitive capacities are coevolutionary products of individual innovation, cultural transmission, and niche construction. This implies that they should appear gradually, as their appearance does not depend on genetic change in the human lineage. The nativist model makes contrary predictions. Change should be more stepwise, as a cognitive module comes on-line, opening up a new set of behaviors. But is there enough information in the historical record for us to tell who is right? We conclude with this pressing methodological problem, beginning with a review of the record and its data.

4. Going Beyond the Evidence? Historical Traces of Cognitive Evolution

As noted in Section 1 , there has been speculation about the evolution of human psychology for well over a century. However, within archaeology and paleoanthropology this speculation has typically been naϯve about the cognitive sciences. Psychologists’ speculations on human evolution have been equally naϯve (see for instance Foley 1996 ). This began to change in the latter decades of the last century, with a small but significant number of publications that were either joint productions of cognitive scientists and archaeologists (Noble and Davidson 1996 ), or that took cognitive theories more seriously (Wynn 1991 ; Wynn 1993 ; Renfrew 1994 ; Mithen 1996 ). This new movement within archaeology and evolutionary studies both tested the claims of evolutionary psychology and morphed into an active branch of “evolutionary psychology” in its own right. So what can this area of evolutionary psychology tell us? Can it discriminate between alternative hypotheses about the history of cognition?

Archaeology can tell us a great deal about our human ancestors. Analysis of a stone tool can show that a hominin manufactured it out of a certain rock type, and thus can also show that hominins traveled long distances, or traded, for the raw material. Biochemical analysis can show that there are residues of animal protein on the tool that indicates its use for butchery. Microscopic analysis can show wear patterns characteristic of certain functions. Fossil evidence provides information about physiological adaptations, such as a shift to bipedalism, and the evolution of precision grip. However, this information is not about cognition as such. To go beyond artifacts and fossils, we have to construct models of behavior, and from these behaviors, models of the associated cognitive skills. So we have evidence for specific cognitive capacities only if these capacities have impacts upon the physical world: impacts that are a consequence of behaviors that are preserved in the historical record. Thus, the best models of cognitive evolution tested in the historical record will take the external environment and its manipulation by actors seriously.

The key, then, to making the physical evidence of the archaeological and fossil record act as a means for testing hypotheses of evolutionary psychology is the construction of models of behavior that make predictions about the interactions of individuals and groups with their physical world. A speech act might leave no direct physical evidence, but a speech act might be necessary for a particular kind of learning, behavior, or activity that in turn leaves some kind of physical evidence. We may not be in a position to determine directly when sophisticated forward planning emerges within the human lineage, but indirectly, the capacity can be inferred from behaviors that require this capacity; behaviors that in turn leave evidential traces.

The notion that we can utilize physical by-products of behavior as tools for understanding minds should not alarm us. We as individuals do this every day when we interpret the desires and beliefs of our fellow agents through the consequences of their actions. We are quite comfortable inferring a set of beliefs and desires about an individual when arriving at a shared office to find an office mate's computer on, and a warm cup of coffee and a scatter of articles on her desk, despite her temporary absence. Forensic scientists routinely reconstruct behaviors and motives from physical evidence in ways that juries find persuasive. So for the historical record to act as a test of evolutionary psychology hypotheses, our models of cognition and behavior should derive predictions about further evidence that can then be detected in the historical record. This information is going to come in two forms: fossil evidence and archaeological evidence.

Behaviors and brains do not fossilize. However, there are endocasts of fossil hominin skulls, which are molds taken from inside a fossil cranium. These can reveal the crude anatomy, hints of surface features, and size of hominin brains. How informative endocasts are, however, remains an open question. It seems unlikely that the folding of the brain surface relates directly to function, as surface folding may well be the result of an allometric process, with increased brain size resulting in increased folding. Sulci, gyrus, and other surface features of the brain, being highly labile and dependent upon body size (Sereno and Tootell 2005 ), may not then be diagnostic of function. Perhaps the surface features of the brain are only informative where gross anatomy of hominin brains reveal changes in sensory input capacities. Endocasts can reveal differences in the relative size of, say, the frontal lobes versus the cerebellum, but again, how much this reveals about cognitive function is highly dependent upon the extent to which specific, functional aspects are localized, and whether these relations between gross structure and function are stable homologies across species. Certainly, the resolution at this level is not enough to inform us of the emergence of specific functions. However, this gross anatomy, along with overall brain size, may provide clues as to the increasing importance of cognitive strategies in human evolution, even if they are uninformative of specific cognitive adaptations per se (Deacon 1997 ).

Fossilized physiological traits directly associated with specialized behaviors may provide clues to cognitive developments. Language adaptations provide a good example here. Breathing control necessary for speech requires increased muscle and nerve control and an inevitable widening of the thoracic vertebral canal. Paleoanthropologists have detected this feature in fossils of Homo neandertalensis , and Homo sapiens , but not in earlier hominins such as Homo erectus and the Australopithecines, nor in extant primates (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ). Other physiological by-products of specialized behaviors include adaptations for precision grip associated with toolmaking (See for instance Marzke 1992 ; Tocheri et al. 2003 ). So there is a clear potential for an important subset of behaviors to leave signals in the fossil record, and these are equally signals of the cognitive mechanisms that drive those behaviors.

Archaeological finds of tools, marked and cracked bones, and other manipulated objects are at once highly suggestive of cognitive developments and novel behavior, but they also require a good understanding of the relationship between the evidence, the behavior, and its cognitive basis. Modeling these relationships is not straightforward. For a start, tools and their diversification in the latter stages of human evolution may be in part a response to changing economic requirements (Stiner et al. 2000 ). So there remains the constant concern that absence of archaeological evidence for cognitive sophistication is not evidence for the absence of cognitive sophistication.

A further problem is that of determining the function of specific tool types, for function tells us about the agent's behavior, and hence the mind responsible for that behavior. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the case of the Acheulean bifaces of the Early Stone Age of Africa, and the Lower Paleolithic of Europe. This technology contravenes many of the expectations we have of a fully human culture: it shows little change over an extended period (approximately two million years ago to .6 mya) and little regional differentiation over a large area (Africa and Eurasia). Quite how hominins used Acheulean handaxes is problematic. The associated cognitive developments are also difficult to interpret. They have been associated with preferences for symmetry (Wynn 1995 , 2002 ), with sexual selection in hominins (Kohn and Mithen 1999 ; Kohn 2000 ), and even as the by-product of a sophisticated hunting strategy utilizing handaxes as “killer Frisbees” (Calvin 1983 ).

The Cambridge Archaeologist Graham Clark proposed an alternative classification based on differing manufacturing methods, which is probably more suitable for evolutionary psychologists.

Mode 1 tools are simple chopping tools and flakes; they emerge approximately 2.6 million years ago in Africa with the Homo genus and make a first appearance in Europe some time later. They are typically modified cobbles, and appear to be manufactured by Early Homo species in direct response to immediate requirements.

Mode 2 tools are associated with the classic Acheulean Handaxes. These tools are bifacially flaked tools; many seem to be manufactured to a standardized “tear drop” shape and are associated with increased transportation of raw materials. Mode 2 technology makes its first appearance approximately 1.6 to 1.5 million years ago, and it overlaps with Homo erectus’ long tenure on the planet.

Mode 3 tools are manufactured from a “prepared core.” This two-step process has an initial piece of raw material that is shaped, and from this large uniform flakes are removed. These standardized flakes are in turn shaped into different tools. Mode 3 technology is associated with Homo neandertalensis and other “Archaic” sapiens.

Mode 4 Tools (Upper Paleolithic and Later Stone Age) represent the emergence of blades and finer worked stone tools, and is generally considered to represent the emergence of a full human suite of toolmaking capacities. (Although not necessarily the emergence of Homo sapiens as a species.) Mode 4 tools show regionalization, specialization, and increased use of alternative materials. Symbolic art and other cultural traits are associated with the emergence of Mode 4 technologies. The middle to upper Paleolithic transition represents the sudden arrival of Mode 4 technology in Europe, but appears to have been a gradual transition from middle to later stone age in Africa from approximately one hundred thousand years ago or even earlier (see text).