To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, cyberbullying in higher education: a review of the literature based on bibliometric analysis.

ISSN : 0368-492X

Article publication date: 21 April 2023

Issue publication date: 15 August 2024

The purpose of this study is to review cyberbullying incidents among students in higher education institutions (HEIs). Cyberbullying has become a threat to students' wellbeing as it penetrates one life due to the pervasive availability of digital technologies.

Design/methodology/approach

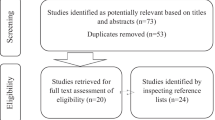

Through a bibliometric analysis, this study analyzes 361 journal publications from the Web of Science (WoS) based on bibliographic coupling and co-word analysis.

Significant themes were found related to cyberbullying in HEIs, particularly related to the impact and determinants of cyberbullying on students. Bibliographic coupling produces three clusters on the current research fronts, while co-word analysis produces four clusters on the prediction of future trends. Implications of this phenomenon warrant comprehensive intervention by the HEIs management to dampen its impact on students' wellbeing. Findings would enhance the fundamental understanding through science mapping on the prevalent and potential incidence of cyberbullying.

Practical implications

Crucial insights will benefit the government, HEIs’ management, educators, scholars, policymakers and parents to overcome this dreadful phenomenon of cyberbullying. Several managerial interventions and mitigation strategies are proposed to reduce and control the occurrence of cyberbullying.

Originality/value

This study presents a bibliometric review to uncover the knowledge structure of cyberbullying studies in HEIs.

- Cyberbullying

- Higher education

- Bibliometric analysis

- Web of Science

Fauzi, M.A. (2024), "Cyberbullying in higher education: a review of the literature based on bibliometric analysis", Kybernetes , Vol. 53 No. 9, pp. 2914-2933. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-12-2022-1667

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

- DOI: 10.1108/k-12-2022-1667

- Corpus ID: 258295680

Cyberbullying in higher education: a review of the literature based on bibliometric analysis

- Muhammad Ashraf Fauzi

- Published in Kybernetes 21 April 2023

- Education, Psychology

6 Citations

Investigating the adverse effects of social media and cybercrime in higher education: a case study of an online university, understanding the influence of cybercrime law absence on cyberbullying in higher institutions of learning: a case of the international university of management, transforming higher education institutions through edi leadership: a bibliometric exploration, green information technology and green information systems: science mapping of present and future trends, creating a positive environment for finding and asking questions in class, medical tourism in south east asia: science mapping of present and future trends, 95 references, cyberbullying: a systematic literature review to identify the factors impelling university students towards cyberbullying, cyberbullying in higher education: a literature review, bullying and cyberbullying: a bibliometric analysis of three decades of research in education, management of cyberbullying: a qualitative exploratory case study of a nigerian university, cyberbullying among university students: gendered experiences, impacts, and perspectives, knowledge hiding behavior in higher education institutions: a scientometric analysis and systematic literature review approach, study of cyberbullying among adolescents in recent years: a bibliometric analysis, cyberbullying: the hidden side of college students, cyberbullying in elementary and middle school students: a systematic review, factors affecting cyberbullying involvement among students of northwestern university, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Cyberbullying in higher education

New citation alert added.

This alert has been successfully added and will be sent to:

You will be notified whenever a record that you have chosen has been cited.

To manage your alert preferences, click on the button below.

New Citation Alert!

Please log in to your account

Information & Contributors

Bibliometrics & citations, view options.

- Abarna S Sheeba J Pradeep Devaneyan S (2023) A novel ensemble model for identification and classification of cyber harassment on social media platform Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems: Applications in Engineering and Technology 10.3233/JIFS-230346 45 :1 (13-36) Online publication date: 1-Jan-2023 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.3233/JIFS-230346

- Wang C Li X Xia L (2023) Long-term effect of cybervictimization on displaced aggressive behavior across two years Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107611 141 :C Online publication date: 1-Apr-2023 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107611

- Achuthan K Nair V Kowalski R Ramanathan S Raman R (2023) Cyberbullying research — Alignment to sustainable development and impact of COVID-19 Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107566 140 :C Online publication date: 1-Mar-2023 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107566

- Show More Cited By

Recommendations

Cyberbullying victimization in higher education.

Few studies have analyzed cyberbullying victimization among university students in comparison to research conducted in other educational levels. The main purpose was to analyze the associations between the cyberbullying victimization and social and ...

Parental mediation, cyberbullying, and cybertrolling

Researchers are concerned with identifying the risk and protective factors associated with adolescents' involvement in cyberharassment. One such factor is parental mediation of children's electronic technology use. Little attention has been given to how ...

Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of cyberbullying and factors in cyberbullying perpetration with a national sample of 4000 adolescents selected through multi-stage cluster sampling. The respondents were 2166 boys (54.1%) and 1834 girls (...

Information

Published in.

Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.

Netherlands

Publication History

Author tags.

- Cyberbullying awareness

- Cyberbullying prevalence

- Higher education cyberbullying

- Social media cyberbullying

- Research-article

Contributors

Other metrics, bibliometrics, article metrics.

- 11 Total Citations View Citations

- 0 Total Downloads

- Downloads (Last 12 months) 0

- Downloads (Last 6 weeks) 0

- Gümüş M Çakır R Korkmaz Ö (2023) Investigation of pre-service teachers’ sensitivity to cyberbullying, perceptions of digital ethics and awareness of digital data security Education and Information Technologies 10.1007/s10639-023-11785-7 28 :11 (14399-14421) Online publication date: 1-Nov-2023 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1007/s10639-023-11785-7

- Celuch M Savela N Oksa R Latikka R Oksanen A (2022) Individual factors predicting reactions to online harassment among Finnish professionals Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107022 127 :C Online publication date: 9-Apr-2022 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107022

- Kaur M Saini M (2022) Indian government initiatives on cyberbullying: A case study on cyberbullying in Indian higher education institutions Education and Information Technologies 10.1007/s10639-022-11168-4 28 :1 (581-615) Online publication date: 4-Jul-2022 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1007/s10639-022-11168-4

- Quayyum F Cruzes D Jaccheri L (2021) Cybersecurity awareness for children International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 10.1016/j.ijcci.2021.100343 30 :C Online publication date: 1-Dec-2021 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.ijcci.2021.100343

- Kopiś-Posiej N Cudo A Tużnik P Wojtasiński M Augustynowicz P Zabielska-Mendyk E Bogucka V (2021) The impact of problematic Facebook use and Facebook context on empathy for pain processing Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106936 124 :C Online publication date: 1-Nov-2021 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106936

- Sarmiento A Herrera-López M Zych I (2019) Is cyberbullying a group process? Online and offline bystanders of cyberbullying act as defenders, reinforcers and outsiders Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.037 99 :C (328-334) Online publication date: 1-Oct-2019 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.037

- Kokkinos C Antoniadou N (2019) Cyber-bullying and cyber-victimization among undergraduate student teachers through the lens of the General Aggression Model Computers in Human Behavior 10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.007 98 :C (59-68) Online publication date: 1-Sep-2019 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.007

View options

Login options.

Check if you have access through your login credentials or your institution to get full access on this article.

Full Access

Share this publication link.

Copying failed.

Share on social media

Affiliations, export citations.

- Please download or close your previous search result export first before starting a new bulk export. Preview is not available. By clicking download, a status dialog will open to start the export process. The process may take a few minutes but once it finishes a file will be downloadable from your browser. You may continue to browse the DL while the export process is in progress. Download

- Download citation

- Copy citation

We are preparing your search results for download ...

We will inform you here when the file is ready.

Your file of search results citations is now ready.

Your search export query has expired. Please try again.

The Infona portal uses cookies, i.e. strings of text saved by a browser on the user's device. The portal can access those files and use them to remember the user's data, such as their chosen settings (screen view, interface language, etc.), or their login data. By using the Infona portal the user accepts automatic saving and using this information for portal operation purposes. More information on the subject can be found in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service. By closing this window the user confirms that they have read the information on cookie usage, and they accept the privacy policy and the way cookies are used by the portal. You can change the cookie settings in your browser.

- Login or register account

INFONA - science communication portal

- advanced search

- conferences

- Collections

Review Cyberbullying in higher education: A literature review $("#expandableTitles").expandable();

- Contributors

Fields of science

- Bibliography

Computers in Human Behavior > 2017 > 69 > C > 268-274

Identifiers

| journal ISSN : | 0747-5632 |

| DOI |

User assignment

| Assign to other user | |

Assignment remove confirmation

You're going to remove this assignment. are you sure.

Lynette K. Watts

- Radiologic Sciences Department, Midwestern State University, 3410 Taft Blvd., Bridwell Hall Office 201E, Wichita Falls, TX 76308, USA

Jessyca Wagner

- Radiologic Sciences Department, Midwestern State University, 3410 Taft Blvd., Bridwell Hall, Office 216, Wichita Falls, TX 76308, USA

Benito Velasquez

- Athletic Training Department, School of Allied Health, Lincoln Memorial University, 6965 Cumberland Gap Parkway, Harrogate, TN 37752, USA

Phyllis I. Behrens

- University of Missouri Extension, 3950 Newman Road, Plaster Hall 107A, Joplin, MO 64801-1512, USA

Higher education cyberbullying Cyberbullying prevalence Cyberbullying awareness Social media cyberbullying

Additional information

- Read online

- Add to read later

- Add to collection

- Add to followed

Export to bibliography

- Terms of service

Accessibility options

- Report an error / abuse

Reporting an error / abuse

Sending the report failed.

Submitting the report failed. Please, try again. If the error persists, contact the administrator by writing to [email protected].

You can adjust the font size by pressing a combination of keys:

- CONTROL + + increase font size

- CONTROL + – decrease font

You can change the active elements on the page (buttons and links) by pressing a combination of keys:

- TAB go to the next element

- SHIFT + TAB go to the previous element

IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- Social Psychology

- Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify the Factors Impelling University Students Towards Cyberbullying

- August 2020

- IEEE Access 8(99):2020

- Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman

- University of Portsmouth

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- S. Tamilselvi

- Civica Moehaimin Dhewanty

- Budi Darma Setiawan

- Juveria Fathima

- Padmaja Kadiri

- S.Jayanth Naik

- Philippe Ea

- Jiahui Xiang

- Osman Salem

- Aye Thazin Khine

- Zaw Ye Htut

- Nobuyuki Hamajima

- José Manuel García-Fernández

- Int J Ment Health Addiction

- Emrah Emirtekin

- Sadia Musharraf

- Muhammad Anis-ul-Haque

- PSYCHIAT RES

- PERS INDIV DIFFER

- J AFFECT DISORDERS

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Education & Teaching

| Kindle Price: | $0.99 | Amazon.com Services LLC |

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Cyberbullying in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature Kindle Edition

- Print length 27 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publication date January 12, 2016

- File size 174 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Not Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

Product details

- ASIN : B01AKQK0B2

- Publisher : Paul D Seeley; 1st edition (January 12, 2016)

- Publication date : January 12, 2016

- Language : English

- File size : 174 KB

- Simultaneous device usage : Unlimited

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Not Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 27 pages

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Report an issue

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Cyberbullying: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify the Factors Impelling University Students Towards Cyberbullying

IEEE Access

Related Papers

Beth Sockman

Helen Cowie , Carrie Myers

Students within the university sector are ‘digital natives’. Technology is not ‘new’ or ‘alien’ to them, but rather it is an accepted and normalised part of everyday life (Simmons et al., 2016). With this level of expertise and competence, we could assume that university students are relatively happy with their online relationships. However, in recent years there has been a growing realisation that, for some students at least, the online world is a very dangerous place. The age of the students is of key importance here too, as those in higher and further education are young adults, rather than children in need of parental support. From this perspective, the university as an institution has a duty of care to its students in their learning environment regardless of their age. In this article, we consider the social and cultural contexts which either promote or discourage cyberbullying among university students. Finally, the implications for policies, training and awareness-raising are discussed along with ideas for possible future research in this under researched area. Key words: bullying/cyberbullying at university; bystanders; bullies; victims; cyberbullying and the law, cyberbully/victims, cultural context

Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research

Humaira Jami

The purpose of the study was to explore modes, strategies, and consequences of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among university students. In-depth interviews of 14 volunteer university students (8 male and 6 female) were conducted who volunteered to participate in the study in which 10 participants were “cybervictims” whereas 4 were “cyberbully-victim”. Interview guide was used for conducting unstructured interviews. Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed different experiences in cyberspace with respect to gender and role (cybervictim and cyberbully-victim) in experiencing cyberbullying and cyber-victimization. Three themes emerged that is psychological consequences (emotional, behavioral, and cognitive), social consequences (family and peers), and change in lifestyle (online, offline, and academic). Facebook was found to be the most prevalent mode of cyberbullying. The cyberbully-victim participants derived more happiness while bullying and had revengeful attitud...

Journal of interpersonal violence,

Technology has many positive effects on education, but negative effects also exist. One of the negative effects is cyberbullying spreading out of school boundaries to the social networks. The increasing popularity of social media among youngsters engenders cyberbullies who exploit the virtual environment besides the usual emails. This distresses the students and adversely affects their families, teachers, and others around them. Although research studies mainly concentrate on prior education, there seems to be a need to investigate the situation in higher education. This study focuses on students studying technology and related disciplines, who are hence likely to be well connected with cyberspace, and explores their awareness about cyberbullying. The findings reveal that female students have significantly less awareness than males. This study will help address some gender issues in cyberbullying.

Cem güzeller

The aim of this study is to determine and analyse the relationships between the cyberbullying perceptions of university students and their psychological aggression behaviours. The population of the study in the relationship survey model included 250 university students from different Faculties at Akdeniz University (Antalya/TURKEY). In order to measure the cyberbullying perceptions and psychological aggression behaviours of these university students, the "Cyberbullying Questionnaire" and the "Psychological Aggression Questionnaire" were used. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the relationships among the variables used in the study. Results of this study revealed that there is a positive and moderate level relationship between cyberbullying perceptions and psychological aggression behaviours. Moreover, there is a negative and high-level relationship between cyberbullying perceptions and gender.

International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education Research

John Mark R . Asio

In the advent of the "new normal" during the pandemic era, strategies to teach and learn switched to online. Students' behavior and attitude also shifted from face-to-face to online. This study aims to assess the students' profiles and the prevalence of cyberbullying in the higher education institutions in Central Luzon, Philippines. The study used a descriptive-correlational technique with the help of an online survey to gather data. Using a convenience sampling technique, 300 higher education students participated in the online survey during the first semester of 2021-2022. In order to attain the objective of the study, the investigators used a standardized instrument. With the help of SPSS 23, the data analyst analyzed the gathered data using the following statistical tools: frequency, weighted mean, and non-parametrical tests like Kruskal-Wallis, Mann-Whitney U, and Spearman rho. The investigator found that the studentrespondents were "never" cyberbullying victims or offenders. Furthermore, statistical inferences showed a variation for cyberbullying offenders as to age and sponsorship/scholarship and a weak indirect relationship between cyberbullying offenders and sponsorship/scholarship characteristics of the students. The investigators recommended pertinent implications for the new normal of learning among students and the institution from the study results.

Information Systems Education Journal

Jiyoon Yoon

Carlos P . Zalaquett

Cyberbullying is commonly presented as affecting K-12 populations. Current research suggests cyberbullying continues in college. A diverse sample of 613 university students was surveyed to study their cyberbullying experiences in high school and college. Nineteen percent of the sample reported being a victim of cyberbullying in college and 35% of this subsample reported being cyberbullied in high school. Additional findings and practical implications are presented.

Fatin Athirah

Participants were 439 college students who were asked how often they had experienced each of a series of bullying behaviors since they have been in college. Results indicated that 38% of college students knew someone who had been cyberbullied, 21.9% had been cyberbullied, and 8.6% had cyberbullying someone else. It was apparent that some forms of electronic media are more commonly used to cyberbully others than are other forms. All the cyberbullying behaviors and traditional bullying behaviors were significantly positively inter-correlated. There were no significant gender or ethnic group differences in any of the cyberbullying behaviors.

The Investigation of Predictors of Cyberbullying andCyber Victimization in University Students

Gizem Akcan

Information and communication technologies catch the attention of people via media that some problems like cyber bullying and cyber victimization are also increased with technological developments. The aim of this study is to examine the effects of gender, frequency of internet usage, perceived academic achievement on cyber bullying, and victimization. The research sample consisted of 151 (76 female,75 male) high school and university students. Demographic Information Form, Cyber Bullying and Cyber Victimization Scales were administered to the participants. According to the results of the Mann Whitney U-test, males were more likely to be cyberbulliers than females; however, they were also more likely to be victims. In the correlational analysis, it was determined that cyberbullying correlated positively with cybervictimization. Furthermore, multi regression analysis showed that cyberbullying was predicted by perceived academic achievement. However, the results of the multi regression analysis indicated that cybervictimization was predicted by frequency of internet usage.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Education Research International

Chantal Faucher , Wanda Cassidy

Nafsika Antoniadou

Jurnal Bimbingan dan Konseling Terapan

Kezia Yemima

EUROASIA SUMMIT (Congress on Scientific Researches and Recent Trends-8th)

Ceren Çubukçu Çerasi

Dr Yusri Bin Kamin

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences (PROSOC)

Shawn Ellis

Mohinder Singh

International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation

Elena BUJOREAN

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology

Prof.Dr. Bahadır Erişti , Yavuz Akbulut

Crime Prevention and Community Safety

Marta Mangiarulo

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Helen Cowie

Tammy Zacchilli

Cyberbullying

Esharenana Adomi

Applied Quantitative Analysis

mark april barbado

Journal of Information Systems and Informatics

Albertina Iileka

Ellen Kraft

Journal of Human Sciences

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies

Memory Mabika

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10244080

Cyberbullying and the Faculty Victim Experience: Perceptions and Outcomes

Jillian r. williamson yarbrough.

1 Management Department, West Texas A&M University, 2501 4th Ave, Canyon, TX 79016 USA

Katelynn Sell

2 Nova Southeastern University, 3300 S. University Drive, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328-2004 USA

3 Bilingual and ESL Education, West Texas A&M University, 2501 4th Ave, Canyon, TX 79016 USA

Leslie Ramos Salazar

4 Business Communication, West Texas A&M University, 2501 4th Ave, Canyon, TX 79016 USA

Associated Data

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding auther, JRWY, upon reasonable request.

Cyberbullying affects US youth, adolescents, and adults and can occur in various settings. Among the academic literature exploring cyberbullying, most discuss cyberbullying of youth and adolescents within the K-12 academic setting. While some studies address cyberbullying targeting adults, a limited amount of research has been conducted on the topic of cyberbullying among adults within the higher education context. Of the studies that explore cyberbullying in higher education, a considerable proportion focus on cyberbullying incidents between college students. Less discussed, however, are the experiences of university faculty who have been cyberbullied by either their students, fellow faculty, or administrators. Few, if any, studies address cyberbullying of faculty as the phenomenon relates to the COVID-19 pandemic. The following qualitative study aims to fill this gap through examining the lived experiences of faculty victims of cyberbullying. Utilizing the theoretical lens of disempowerment theory, researchers recruited a diverse population of twenty-five university faculty from across the USA who self-reported being victims of cyberbullying. The study analyzes participants’ interview responses to determine common experiences of faculty and overarching themes concerning cyberbullying in the academic workplace, particularly within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team applied disempowerment theory to support thematic analysis. In addition, the present article offers potential solutions for supporting faculty as they navigate virtual learning environments. The study’s findings hold practical implications for faculty, administrators, and stakeholders in institutions of higher education who seek to implement research-driven policies to address cyberbullying on their campuses.

Introduction

Cyberbullying entails using electronic devices to bully another person through threats, spreading rumors, and/or impersonating others. Cyberbullying can occur in various digital settings such as in email correspondence, text messages, or on social media platforms. Cyberbullying is a component of cyber-abuse, or online abusive interpersonal behaviors that are overly aggressive in nature and that threaten, harass, embarrass, or socially ostracize the victim (Piotrowski, 2012 ). The phenomenon has been growing in prevalence and is on the rise worldwide (Cook, 2021 ). While significant academic research has examined cyberbullying among youth and adolescents (Calvete et al., 2010 ; Hutson et al., 2018 , Li et al., 2016 ; Nikolaou, 2021 ; Patchin & Hinduja, 2010 ), fewer research studies have explored cyberbullying among adults. Yet, most adults have first-hand or second-hand experience with cyberbullying. Indeed, in 2014, the Pew Research Center reported that 75% of US adults have witnessed cyberbullying while 40% of US adults have personally experienced some form of online harassment (Duggan, 2014 ).

The experiences of adult victims of cyberbullying proves distinct from the experiences of youth victims (Scheff, 2019 ). One unique aspect involves adults’ experiences with cyberbullying in the workplace (Chapel et al., 2019 ). Workplace bullying is defined as a systematic, repetitive engagement of interpersonally abusive behavior that negatively impacts the victim and the organization (Sansone & Sansone, 2015 ). While workplace bullying previously occurred primarily face-to-face, technology is enabling a virtual form, cyberbullying. In a large study of workplace conditions, Kowalski et al. ( 2018 ) found that 20% of workers reported experiencing cyberbullying. This proves especially concerning since cyberbullying leads to problematic outcomes for both the individual victim and the organization for which they work. First, the targets of workplace bullying may experience mental distress, sleep disturbances, fatigue, energy deprivation, depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders. Cyberbullying may even lead to victims’ committing suicide (Alipan et al., 2021 ; Sansone & Sansone, 2015 ). Second, cyberbullying hurts organizational effectiveness by damaging organizational culture, employee well-being, employee work engagement, and employee retention (Karthikeyan, 2020 ; Muhonen et al., 2017 ).

Clearly, the issue of cyberbullying in the workplace is significant and growing. Studying specific work environments can yield targeted solutions to the problem. One industry that is grappling with cyberbullying’s deleterious effects is academia. The literature that has studied cyberbullying within the higher education context has primarily concentrated on the experiences of college students who have been bullied by other students (Cimke & Cerit, 2021 ; Faucher et al., 2014 ; Khine et al., 2020 ; Kowalski et al., 2022 ; Molluzzo & Lawler, 2012 ; Varghese & Pistole, 2017 ; Whittaker & Kowalski, 2015 ). A limited number of peer-reviewed research articles have explored the effects of cyberbullying on college and university faculty who have experienced cyberbullying within a workplace context.

Despite the topic not receiving significant discussion in the academic research, the cyberbullying of college and university faculty proves a pervasive problem. Faculty regularly experience cyberbullying not only from students, but from colleagues, superiors, and the general public (Cassidy et al., 2016 ; Cassidy et al., 2017 ; Cuevas, 2018 ; Lloro-Bidart, 2018 ; Meriläinen et al., 2016 ; Weiss, 2020 ). An examination of whether the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to augmented levels of cyberbullying against faculty proves especially necessary. Due to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, faculty are increasingly engaging with students and colleagues through online learning management systems, email, and social media. Apart from engaging in increased amounts of online communication, many faculty saw their work duties shift to a virtual format for several months during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, various colleges and universities have shifted courses that had been conducted previously “in-person” in brick-and-mortar classrooms to an online format (Clemmons et al., 2022 ; Fogg et al., 2020 ; Kourgiantakis et al., 2021 ). Since the nature of communication, collaboration, and coursework has changed significantly in academia during the COVID-19 pandemic, the forms and amount of cyberbullying of college faculty may have, likewise, been transformed.

One reason this may be the case is that increases in electronic forms of communication contribute to heightened levels of cyberbullying. When people communicate virtually, they receive fewer social cues, have an increased sense of anonymity, and feel less concern over the tone of their message due to the asynchronous nature of the communication (Wildermuth & Davis, 2012 ). When considering the higher education workplace for faculty, the amount of time that faculty spend working online correlates to the likelihood that faculty become cyberbullying victims (Cassidy et al., 2014 ). Since the COVID-19 pandemic has led to greater amounts of electronic communication between faculty and students and increases in the number of job-related duties that faculty perform virtually, faculty may be more likely to experience cyberbullying. However, to the researchers’ best understanding, academic research studies on the topic have yet to be published on the subject. The following study seeks to fill this gap through conducting a qualitative analysis of interviews with 25 university faculty from across the USA who self-reported that they had been victimized by cyberbullying in the workplace. Specifically, this study seeks to explore university faculty’s lived cyberbullying experiences using disempowerment theory as a framework (Kane & Montgomery, 1998 ).

According to the disempowerment theory, individuals who feel inadequate are at risk of employing power assertions, including violence, to control people who they perceive as threatening (Archer, 1994 ). The theory identifies a range of risk factors that may predict the use of violence to re-establish power, authority, or control of others in a relationship (Bosco et al., 2022 ; McKenry et al., 2006 ). Individual factors such as self-esteem, personality, mental health issues, substance misuse, family origin, and insecure attachment can make a person more prone to abuse others. According to disempowerment theory, acts of violence or aggression are ultimately seen as an individual’s attempt to reassert power and maintain control over another individual (Kwong-Lai Poon, 2011 ; Mendoza, 2011 ).

Disempowerment theory offers a theoretical framework to understand cyberbullying perpetration and victimization based on the power dynamics of workplace relationships (Kane & Montgomery, 1998 ). With this theoretical perspective, cyberbullying in the workplace can be at least partially explained by increased feelings of disempowerment among employees. Feelings of disempowerment lead to negative emotions and job attitudes that disrupt work-related goals (Kituyi, 2021 ). When employees feel disempowered in relationships within a work context, employees may attack others to regain a sense of empowerment over their victims. Over time, this creates a negative work environment, which can adversely influence workplace productivity (Farley et al., 2015 ). In higher education, disempowerment theory posits that power imbalances can occur between faculty and students, faculty and staff, and faculty and administrators given varying ranks, positions, and years of work-related experience (Keashly & Neuman, 2010 ; Woudstra et al., 2018 ). From this disempowerment perspective, workplace cyberbullying leads to negative outcomes for victims such as high stress, demoralization, and low mental well-being (O’Donnell et al., 2010 ; Tsang & Liu, 2016 ).

Apart from applying disempowerment theory to examine faculty’s lived experiences of cyberbullying in the academic workplace, the study elaborates on the frequency and forms of cyberbullying that faculty members face. Furthermore, the article details the negative impacts of cyberbullying on faculty. Finally, the authors connect the study’s findings with the extant literature and propose practical solutions to the current issue of cyberbullying in academia.

Literature Review

Cyberbullying is associated with significant negative outcomes such as depression, low self-esteem, emotional distress, and even self-harm (Celik et al., 2012 ; Coyne et al., 2016 ; Eyuboglu et al., 2021 ). There are numerous forms of cyberbullying such as hate speech, harassment, and trolling and each form will have different consequences and outcomes (Park et al., 2021 ; Saladino et al., 2020 ; Xu & Trzaskawka, 2021 ). Various research studies have explored cyberbullying among youth in the K-12 learning environment, concluding that cyberbullying proves prevalent in K-12 schools (Calvete et al., 2010 ; Hutson et al., 2018 ; Li et al., 2016 ; Nikolaou, 2021 ; Patchin & Hinduja, 2010 ). Significant research has also been conducted concerning college students’ cyberbullying experiences. Like K-12 students, a substantial proportion of college students—upwards of half of college students—report experiencing cyberbullying within the last 6 months (Kowalski et al., 2022 ). College students often report receiving cyber abuse from their fellow student peers, causing significant harm to victims’ emotional wellbeing (Cimke & Cerit, 2021 ; Faucher et al., 2014 ; Khine et al., 2020 ; Kowalski et al., 2022 ; Molluzzo & Lawler, 2012 ; Varghese & Pistole, 2017 ; Whittaker & Kowalski, 2015 ). Additionally, there is a growing body of literature examining the adult experience with cyberbullying in the workplace (Chapel et al., 2019 ; Coyne et al, 2016 ; Vranjes et al, 2017 ). As the present paper concentrates on cyberbullying that targets faculty in the workplace, the literature review will primarily focus on this aspect of cyberbullying.

Cyberbullying in the Workplace

Several studies have examined cyberbullying in the workplace among adult populations, concluding that cyberbullying had deleterious effects on worker’s emotional well-being, overall social interactions at work, job satisfaction, and job commitment. Specifically, Kowalski et al. ( 2018 ) found that cyberbullying victimization among employees led to enhanced counterproductive work behavior, depression, and reduced job satisfaction. In a large study featuring 254 white collar employees across several corporations, Loh and Snyman ( 2020 ) determined that workplace cyberbullying led to an increased level of perceived stress, causing reduced job satisfaction. In the study, females reported more negative effects from workplace cyberbullying than males (Loh & Snyman, 2020 ). Another study documented that perceived cyberbullying across industries positively related with social vulnerability and social withdrawal (Qaisar et al., 2020 ). In a cross-sectional study among employees, Makalesi et al. ( 2022 ) concluded that workplace cyberbullying was positively correlated with employee burnout, which indirectly affected employee work engagement in the organization.

Several studies have also explored workplace cyberbullying in the healthcare field. For instance, Farley et al. ( 2015 ) found that 42.2% of trainee doctors experienced cyberbullying, and this negatively impacted their job satisfaction and mental strain. In another study, Park and Choi ( 2018 ) noted that 8% of nurses experienced workplace cyberbullying, which the authors linked to nurses’ intentions to leave their current jobs in general and tertiary hospitals especially in cases where nurse victims received little social support. Another study indicated that the workplace cyberbullying of nurses was shown to lead to increased job stress and reduced self-esteem (Kim & Choi, 2021 ).

Workplace cyberbullying is also evident in online labor fields. D’Cruz and Noronha ( 2018a ) conducted interviews among 13 clients and freelancers who used electronic platforms as part of their jobs. The researchers indicated themes of victims seeking resolution and moving on after the workplace cyberbullying experiences. In a follow-up study, D’Cruz and Noronha ( 2018b ) also interviewed 13 clients and freelancers in online jobs and found that when seeking resolution from the cyberbullying experience, employees focused on maintaining platform mechanisms, implementing interventions, taking initiative, and being cautious. Further, employees overcame cyberbullying through consulting informal social support systems, through avoiding risks, and by increasing their sense of control and personal growth. As can be seen in the aforementioned studies, cyberbullying has become a widespread problem across various industries. The next section of the literature review will discuss the academic literature related to cyberbullying in academia, which can have a direct impact on faculty’s experiences of cyberbullying within the workplace.

Cyberbullying in Higher Education

While the overall amount of academic literature focusing on university faculty’s experiences with cyberbullying proves scant, some studies have researched the perceptions of students and faculty related to cyberbullying in academia. Molluzzo et al. ( 2013 ) examined perceptions of cyberbullying of both full-time and part-time faculty at a large, private metropolitan university. The authors documented that 98% of faculty participants believed cyberbullying was unethical. Further, the researchers identified an overwhelming perception among both faculty and student participants that their university needed to do more to educate students, faculty, and staff about the damaging effects of cyberbullying (Molluzzo et al., 2013 ). Molluzzo and Lawler ( 2014 ) explored both student and faculty perceptions related to cyberbullying at Pace University, a private university. The researchers determined that students were almost twice as likely as faculty to identify cyberbullying as a significant issue affecting them personally (47.4% of students vs. 26.2% of faculty). The researchers’ survey showed that 76.3% of students and 55.6% of faculty agreed that their university is working to address cyberbullying. In another study, Meter et al. ( 2021 ) determined that among the sixteen college student participants in their exploratory, qualitative study, students overwhelmingly viewed cyberbullying as a gray area. Furthermore, students’ definitions of cyberbullying were highly varied. However, there existed a relative consensus among student participants that the distance between the bully and victim empowered the bully (Meter et al., 2021 ).

Other academic research exploring cyberbullying in higher education has documented the substantial prevalence of cyberbullying on college campuses in the USA and Canada. In Molluzzo et al.’s ( 2013 ) study, 12% of faculty participants were aware of the cyberbullying of students at the university, and 10% reported being cyberbullied themselves by a student or another faculty member through social media. In Molluzzo and Lawler’s ( 2014 ) follow-up study, 16.0% of students and 6.3% of faculty were aware of cyberbullying at other institutions. Cassidy et al. ( 2016 ) reported incidents of cyberbullying from four Canadian universities and found that 25% of surveyed faculty members had experienced cyberbullying by students and15% had been attacked by colleagues. Additionally, the study identified that females were more likely to be the target of cyberbullying. Cassidy et al. ( 2017 ) conducted an additional study with a qualitative thematic analysis regarding the impacts of cyberbullying on post-secondary students, faculty, and administrators from four Canadian universities. Interestingly, students primarily reported being cyberbullied by other students, while faculty reported being cyberbullied by both students and colleagues. Hollis ( 2021 ) examined cyberbullying in the higher education workplace among work colleagues. A sample of 578 higher education professionals and faculty members were collected in late 2017/early 2018. Forty-five percent of respondents reported they were targets of cyberbullying in higher education via email, social media, and/or text communication from colleagues in their higher education work environment. Uniquely the study applied social dominance theory to examine whether women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community reported more incidents of cyberbullying. Through a chi-square analysis, it was confirmed that people of color and members of the LGBTQ community were more likely to be targets of cyberbullying in higher education. Meter et al. ( 2021 ) learned that nearly all college student participants in their qualitative exploratory study had observed or experienced cyberbullying.

While academic literature that focuses on the cyberbullying of faculty in the workplace proves scarce, a few academic research studies have documented the negative impacts of cyberbullying on college faculty. In their study of the various episodes of cyberbullying occurring at four Canadian universities, Cassidy et al. ( 2017 ) found that the negative impacts of cyberbullying proved consistent across age and position/title. Participants reported that cyberbullying had negative effects on their mental health, physical health, and perceptions of self. Victims, likewise, reported that cyberbullying harmed their personal and professional lives while also causing victims to have increased concern for their personal safety (Cassidy et al., 2017 ). Blizard ( 2018 ) explored the negative impact of faculty cyberbullied by their students. Targeted faculty experienced negative physical, emotional, relational, and occupational effects. One faculty member even resigned their position and moved to another country due to cyberbullying. The researcher noted that faculty victims encountered detrimental effects in their relationships with others. Indeed, 74% of victims felt their relationships with students deteriorated, while 37% concluded that their relationships with both colleagues and administrators declined (Blizard, 2018 ).

The literature communicates that adults are experiencing cyberbullying in the workplace and, specifically, faculty are experiencing cyberbullying in their role as educational facilitators. While there is emerging research specifically addressing cyberbullying in academia, there is a gap in the literature that identifies faculty victims’ perceptions of cyberbullying. In a similar vein, few studies have explored the lasting, negative impacts of cyberbullying on college faculty. Insight from faculty on viable solutions to cyberbullying has, likewise, been largely unexplored. As such, this study will contribute to existing research by examining the experiences of faculty victims of cyberbullying and faculty victims’ beliefs on how cyberbullying in the academic workplace should be resolved. By conducting and analyzing faculty interviews, the authors gathered new perspectives not addressed in prior research. Moreover, as few studies have utilized disempowerment theory to explain cyberbullying incidents targeting college faculty, the current study adds much to the extant literature.

Research Questions

- RQ1: What factors explain cyberbullying perpetration against faculty?

- RQ2: How did faculty cyberbullying experiences change during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ3: What are the challenges of faculty dealing with cyberbullying?

The mixed-method study employed a phenomenological, qualitative research design with descriptive statistical methods. This methodology was particularly appropriate as it allowed the researchers to acquire, and later convey, the lived experiences of research participants. Life experiences are difficult to study through quantitative inquiry, as individual experiences cannot be replicated (Lloyd et al., 2014 ). While individual experiences are unique, the phenomenological research approach seeks to arrive at a description of the nature of a particular group through understanding commonalities of lived experiences within an identified group (Creswell, 2013 ). Through interviewing individuals who have first-hand knowledge of an event or an experience, researchers seek to understand each participant, what participants have experienced in terms of this phenomenon, and what contexts or situations have typically influenced their experiences (Moustakas, 1994 ).

Participants

The research team consisted of four faculty members from a mid-size, regional state university in the Southwest. Three members of the research team were business professors, while the fourth member was a faculty member in the department of education. All research team members had conducted previous research on the topic of cyberbullying in the workplace. Several members of the research team had published individual book chapters in a book edited by one of the research team members.

The research team selected subjects through purposive sampling, specifically recruiting tenure track and non-tenure track faculty currently teaching in higher education institutions in the USA. Researchers recruited 25 participants to engage in individual qualitative interviews. Recruitment of participants continued until researchers reached theoretical saturation regarding the themes and topics being discussed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ). Further, 25 participants are consistent with Creswell’s ( 2013 ) guidelines of between five and 25 participants for a phenomenological study. Participants had to meet the following criteria: at least 18 years old, currently serving in a faculty position at a higher education institution, and having experience teaching at least one online course within the past year. Participants were recruited via email, word-of-mouth, and oral presentations. Researchers examined all forms of cyberbullying. Participant demographics are listed in Table Table1 1 .

Demographics of the participants

| Participant | Title | Years teaching | Location | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adjunct | 25 + | Texas | Male |

| 2 | Adjunct | 1 | Florida | Female |

| 3 | Faculty and director | 20 + | Texas | Female |

| 4 | Assistant professor of management | 8 to 10 years | Texas | Male |

| 5 | Lecturer | 16 years | Texas | Male |

| 6 | CEO Educational Consulting Company | 27 | California | Male |

| 7 | Adjunct instructor | 20 | Texas | Male |

| 8 | Professor | 11 | Georgia | Male |

| 9 | Professor | 13 | Texas | Male |

| 10 | Assistant professor | 17 | Texas | Female |

| 11 | Associate professor and interim chair | 7 | Texas | Female |

| 12 | Assistant professor | 18 | Texas | Female |

| 13 | Associate professor and department chair | 20 + | Texas | Female |

| 14 | Lecturer | 4 | Texas | Male |

| 15 | Lecturer | 7 | Texas | Female |

| 16 | Assistant professor | 5 | Texas | Male |

| 17 | Associate | 9 | Texas | Female |

| 18 | Full professor | 30 | Texas | Male |

| 19 | Associate professor | 4 | Texas | Female |

| 20 | Associate professor | 11 | Texas | Female |

| 21 | Lecturer | 6 | Texas | Female |

| 22 | Lecturer | 3 | Texas | Female |

| 23 | Clinical associate professor | 7 | Texas | Female |

| 24 | Associate professor | 5 | Texas | Male |

| 25 | Professor | 28 | Texas | Male |

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the researchers recruited participants using purposeful sampling. Researchers recruited participants by emailing announcements to faculty discussion groups and listservs. Researchers also used word of mouth to recruit participants. Faculty self-selected if they had interest in participating in the study based on their perceptions and experiences of workplace cyberbullying in higher education institutions. If faculty members expressed interest in participating in the study, they received a description of the research study via email with the information necessary regarding the study. Participants were asked to confirm interest by contacting one of the researchers and by signing the informed consent document via email or face-to-face. To assess participants’ cyberbullying experiences, they were asked to discuss their specific cyberbullying experiences in performing duties such as teaching, research, and service in their academic job. The research team led semi-structured interviews via Zoom, which were audio–video recorded using the meeting application’s recording feature. Interview questions are listed in Table Table2. 2 . Two of the eight interview questions specifically addressed topics related to disempowerment theory. Specifically, question 5 of the interview protocol asked participants to consider why cyberbullying happens to faculty and why the faculty member, herself/himself, believed that they had been targeted. Based on participants’ answers, the researchers asked follow-up questions related to power dynamics and possible motivations for the abuser to engage in cyberbullying. Question 6 asked participants to reflect on how the COVID-19 pandemic had changed the nature of cyberbullying attacks against faculty. While not directly stated to participants to skew participants’ responses, one intent behind this question was for participants to consider how the COVID-19 pandemic, a natural disaster which left countless people feeling helpless, physically ill, and disempowered, might have influenced the cyberbullying of faculty members. Whenever possible, at least two researchers conducted the interviews. Having multiple researchers attend each interview supported the thematic analysis of the interviews, as it allowed for researchers to compare notes and agree upon central themes. Before each interview, participants were asked if they felt comfortable being interviewed by multiple interviewers or if they preferred to only be interviewed by the primary researcher. Following each interview, the researchers who conducted the interview met among themselves to debrief and compare notes. Each participant was assigned a code to preserve anonymity, and each interview lasted approximately 1 h. Interviews were transcribed and reviewed so that researchers could identify central themes across the interviews and descriptive tables were developed from the interview data.

Interview questions

| Demographic information: |

| Title: |

| Years teaching: |

| Years teaching online: |

| Percentage of work duties moving online based on the pandemic: |

| Type of institution where you work: |

| 1. Before we get started, can you tell me about the types of online and virtual academic experiences you have had? |

| a) What are your online experiences with teaching, research, and conferences prior to the pandemic? |

| b) Do you feel that the amount of time that you spend online for work-related purposes has changed since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020? Why or why not? |

| 2. We define cyberbullying as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices.” How do you define cyberbullying? |

| 3. Can you describe a time when you experienced cyberbullying in relation to your teaching, research, service, or other aspects of your job? |

| 4. How did this experience make you feel? |

| a) How did it impact you personally? |

| b) How did you deal with each incident of cyberbullying? |

| c) Did you find that the person who dealt with the incident of cyberbullying handled the situation effectively? Why or why not? |

| d) Do you think the incident (s) of cyberbullying have been resolved? Why or why not? |

| 5. Why do you think cyberbullying happens to faculty? Explain. |

| a) Why do you think you were a target of cyberbullying? |

| 6. Do you think cyberbullying for faculty has changed at all during the pandemic? Explain. |

| a) Do you feel that the amount of time that you spend online for work-related purposes relates to your experiences with cyberbullying? Why or why not? |

| 7. Based on your experience, describe a specific impact of cyberbullying on the faculty, the student, or the institution. |

| 8. What are the barriers to reporting cyberbullying to the appropriate authorities at your institution? |

Data Analysis

After researchers performed interviews, researchers transcribed the interviews. The data analysis process followed five steps: (1) prepare and organize data, (2) review and explore data, (3) create initial codes, (4) review the codes, and (5) present the themes in a cohesive manner. The first step required the primary researcher to engage in data by creating interview transcripts and reviewing each interview word for word. Next, the primary researcher examined transcripts to explore the data. From the review of transcripts, the primary researcher identified macro-level themes for each interview question. Next, the primary researcher gave the other research team members interview transcripts and a table indicating the cumulative frequency of macro-level themes across the interviews. Each researcher team member individually reviewed the transcripts and considered micro-level theme interpretations. The research team members then met as a group to review the macro-level and micro-level themes. The research team came to a consensus on macro- and micro-level themes, primarily through redefining, associating, or consolidating identified concepts (Alhojailan, 2012 ). As a result, the research team agreed upon three macro-level themes (Table (Table3) 3 ) and several micro-level question themes (Tables (Tables4, 4 , ,5, 5 , ,6, 6 , and and7). 7 ). The three macro-level themes were identified when a clear theme was evident across several interviews (indicated by having a high percentage of participants corroborating the same theme). Through this process, the researchers constructed a collaborative meaning of the participants’ experiences as faculty victims of cyberbullying, particularly within the context of disempowerment theory. Incorporating disempowerment theory to determine meaning of participants’ responses and to explain participants’ responses within a theoretical framework allowed the researchers to develop a greater understanding of the given phenomenon. Inter-theme reliability was tested for the thematic analysis to ensure the themes’ interpretation was maintained between coders (Crabtree & Miller, 1999 ). Any discrepancies between coders and researchers were discussed until a consensus was reached and 100% inter-coder reliability was achieved.

Overall study themes

RQ1: Subtheme 1: Anonymity fuels cyberbullying. Subtheme 2: Power dynamics fuel cyberbullying. |

RQ2: The COVID-19 pandemic helped fuel cyberbullying against faculty. |

RQ3: Subtheme 1: Faculty felt vulnerable. Subtheme 2: Faculty do not perceive that their university has clear cyberbullying policies and procedures in place to protect faculty. |

Reasons cyberbullying happens to faculty

| Why do you think cyberbullying happens to faculty? | Percentage | Overall occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Anonymity. | 0.28 | 7 |

| Power. | 0.24 | 6 |

| Blaming others for your problems. | 0.12 | 3 |

| When students don’t get what they want. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Technology availability. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Happens in all workplaces. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Politics. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Grade manipulation. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Lack of communication skills. | 0.04 | 1 |

Cyberbullying during the pandemic

| Do you think cyberbullying for faculty has changed at all during the pandemic? | Percentage | Overall occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 0.8 | 20 |

| No | 0.12 | 3 |

| I do not know. | 0.08 | 2 |

Barriers to reporting cyberbullying

| What are the barriers to reporting cyberbullying to the appropriate authorities at your institution? | Percentage | Overall occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| No clear cyberbullying policy at the university. | 0.28 | 7 |

| Retaliation. | 0.16 | 4 |

| There are no barriers. | 0.12 | 3 |

| Lack of trust. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Fear. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Knowing nothing will be done if you report. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Hassel to report. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Intimidation. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Shame. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Expectations that faculty handle their own student situations. | 0.04 | 1 |

| I have no idea. | 0.04 | 1 |

Bystanders not reporting cyberbullying instances

| What do you think might be the reasons bystanders choose to not report cyberbullying instances? | Prevalence | Overall occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Not trusting the system. | 0.16 | 4 |

| It does not affect them. | 0.16 | 4 |

| Fear they will be a victim too. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Lack of awareness. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Faculty should handle their own class events. | 0.08 | 2 |

| Power differentials. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Retaliation. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Bystanders. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Embarrassment. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Fear of being ostracized. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Apathy. | 0.04 | 1 |

| I am not involved in this. | 0.04 | 1 |

| It did not happen to me. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Policies not clear. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Do not agree that the event was cyberbullying. | 0.04 | 1 |

| Anonymity. | 0.04 | 1 |

There were three consistent themes identified across the faculty interviews. First, victims perceived that anonymity and power dynamics significantly influenced cyberbullying incidents. Second, faculty believed that the pandemic led to an increase in cyberbullying against faculty. Third, faculty felt particularly vulnerable to cyberbullying incidents because their universities lacked clear cyberbullying policies and procedures to support faculty victims of cyberbullying. The thematic findings were developed through intense review of participant interview data. The data was examined for key words and similar experiences to support identification of themes.

Anonymity, Power Dynamics, and Cyberbullying

One common theme that addressed RQ1 (factors explaining cyberbullying perpetration against faculty) across many of the interviews was the relationship between anonymity (subtheme 1) and power dynamics (subtheme 2) with cyberbullying. To begin, many participants viewed the aggressor’s perceived sense of anonymity online as a contributing factor to cyberbullying incidents. When asked, “ Why do you think cyberbullying happens to faculty ,” more than a quarter of participants (28% or 7 participants) stated that anonymity was a significant reason for cyberbullying. One participant explained that anonymity provides the cyberbullying perpetrator protection, allowing the cyberbully to “hide behind a computer and say…inappropriate things and things they wouldn’t say face-to-face.” Another participant reiterated this viewpoint: “I think that sort of anonymity or that sense of it’s easier to send this kind of rude email to someone versus saying that to their face. I’ve received [that] from students, for instance.” Descriptive frequency analysis was also used, which pointed to other reasons for why cyberbullying occurs to faculty including power (the second most common explanation with 24% of participants associating cyberbullying with the abuser’s quest for power), blaming others, technological availability, politics, grade manipulation, and lack of communication skills, among others listed in Table Table4. 4 . Several of those reasons—most notably exerting power and attempting to manipulate professors’ grading—directly tie to disempowerment theory, a topic which will be elaborated upon in the “ Discussion ” section of this paper.

Cyberbullying of Faculty During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A major theme derived from RQ2 (cyberbullying changes during the COVID-19 pandemic) highlighted that most participants believed that the COVID-19 pandemic created unique conditions for cyberbullying incidents. In response to the question, “ Do you think cyberbullying for faculty has changed at all during the pandemic ,” four-fifths of participants, twenty participants out of twenty-five, felt that cyberbullying had changed during the pandemic. Of the 80% of participants that perceived cyberbullying had changed during the pandemic, nearly half discussed how cyberbullying had increased during the pandemic. Five participants identified that added stress was a factor for increased cyberbullying. As one participant described, cyberbullying had changed “just based on the additional stresses that people have been dealing with through the pandemic…[This] may not be necessarily anything to do with the faculty member, but maybe just life stresses.” Several participants (12%) believed that increased technology usage had spurred cyberbullying during the pandemic. A participant noted, “Everything is more online, so I think the opportunity is [there] for someone to encounter cyber bullying.” Finally, three participants believed social dissention during the pandemic factored into increases in cyberbullying. As one participant explained, cyberbullying changed because of “the situation that we’ve been brought throughout the pandemic, not necessarily because of COVID, but because of everything that happened through COVID, you know, with the riots and all the unrest that happened.” Descriptive frequency analysis also pointed to those changes that occurred from compounding issues, distance communication, more online interaction, exhaustion, and burnout (see Table Table5). 5 ). As will be addressed in the “ Discussion ” section of the article, participants’ attributing the heightened levels of workplace cyberbullying against faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic to increased stress, social unrest, exhaustion, and burnout further justify the application of disempowerment theory as an analytical tool.

Faculty Vulnerability and a Lack of Institutional Support

A central theme based on RQ3 (challenges of cyberbullying on faculty) from the interviews included many participants’ feelings of vulnerability as faculty (subtheme 1) and dissatisfaction with their institutions’ handling of cyberbullying (subtheme 2). Many participants mentioned faculty’s vulnerability to cyberbullying due to the public nature of their positions and the accessibility to professors through social media. Five faculty participants (20% of all participants) specifically recommended that faculty be cautious with sharing information on social media. One participant provided the following admonition: “Don’t be on social media. I think that is one thing. I just feel like a lot of times when you put everything that is important to you [online] that you’re vulnerable…It does give a person who could harm you or who wants to bully you or to cause you distress that ammunition.” Interestingly, some participants felt particularly powerless to protect themselves from cyberbullying. Two quotes from different participants demonstrate these faculty members’ sense of incapacitation: “I really don’t think we can [prevent cyberbullying]. I think we’re pretty vulnerable. I mean, you’ve got different types of students from different backgrounds” (participant 21). A second participant stated “I really don’t know how you could protect yourself against it [cyberbullying], because how do you stop somebody from bullying you? Right?” (participant 19).

Other faculty felt reporting cyberbullying to their institutions led to negative professional repercussions. In terms of their individual experiences as cyberbullying victims, four of the twenty-five participants (16% of all participants) directly referred to the retaliation that professors could receive for reporting cyberbullying. One participant described choosing to not report the cyberbullying incident out of fear of being further targeted by the cyberbully—an administrator—in retaliation for reporting: “I didn’t want to report it because I didn’t want, you know, him to give me bad feedback on my evaluation.” Another participant detailed specific retribution that she received due to reporting cyberbullying: “Well, as a result of me reporting it, he reported me to the ombudsman person. And so, then I had to meet with that individual about my quote, unquote treatment of him, and I was not willing to go into detail with her on anything.” The connection between “disempowerment” theory and acts of retribution will be detailed in the “ Discussion ” section of the paper.

Related to many faculty’s feelings of vulnerability to cyberbullying were several faculty’s perception that higher education institutions failed to adequately respond to cyberbullying. When participants were asked, “What are the barriers to reporting cyberbullying to the authorities at your institution?” 28%, or seven out of twenty-five participants stated that they were unaware of a clear cyberbullying policy at their university and, without a policy, steps for reporting were difficult to identify. One participant described how there had never been clear guidance in her institution for how to address cyberbullying, while another participant stated that institutions needed a clear policy “…for people to know where to go and how to do it [report cyberbullying], knowing what the processes are, being very clear about those processes, and making it very accessible and easy to do.” From the descriptive statistical analysis, other barriers for reporting cyberbullying included lack of trust, fear, reporting issues, intimidation, and shame (see Table Table6 6 ).

On a related question involving faculty challenges, “ What do you think might be the reason bystanders choose to not report cyberbullying instances ,” four participants (16%) felt that institutions would not address cyberbullying effectively. One participant depicted her lack of confidence in her institution’s ability in blunt terms: “I will say, in my instance…I find that nothing will come from it. It’ll just be filed away under. ‘OK. We’ll just keep an eye on it.’” Another professor detailed both a lack of faith in their institution’s ability to handle the solution as well as a suspicion of retribution for reporting cyber victimization as an outside bystander observing the cyberbullying: “Again, not trusting the system. I’ve seen [that] you’re told that something’s anonymous, but I don’t trust that.” Table Table7 7 provides other reasons faculty believed bystanders failed to report observing cyberbullying (e.g., faculty believing that the cyberbullying did not affect them personally, lack of awareness, fear, concerns about retaliation, etc.).

Apart from these three central themes, the researchers concluded that cyberbullying is a nuanced experience with varied perceptions. Through the interviews, it was clear that cyberbullying can be clinically defined, but that the individuals’ perception of what designates cyberbullying and of their individual experiences with cyberbullying varied. Some faculty members felt the experience of cyberbullying was humorous, they never felt helpless, and they perceived all bullying events as stemming from issues internalized by the bully. While other faculty described their cyberbullying experiences as hopeless, scary, and without potential for resolve. One variation between these two extremes within the group was the victims’ perception of their own ability to bring about a resolution. The faculty that believed they could resolve the issue or that they, through their own power, had resolved it, perceived the cyberbullying attack as less concerning. The faculty that believed their cyberbullying experiences could not be resolved and that they had no administrative support were more fearful for their lives and careers.

The present study documents the lived experiences of 25 faculty who experienced cyberbullying in the university workplace. Participants shared a range of perspectives concerning the cyberbullying incident’s effect on their work life and emotional health. While each faculty’s experiences as a victim of cyberbullying proved unique, the researchers identified three consistent themes through the collective interview process. First, anonymity of the bully is a significant contributor to the rise of cyberbullying as well as the bully’s desire to reassert power. Second, the challenges that arose from the global COVID-19 pandemic spurred increases of cyberbullying against academic faculty. Third, faculty do not perceive that there are clear cyberbullying policies and procedures in place at their universities to support faculty.

As discussed earlier, several participants in the present study believed that the cyberbullying events they had experienced would not occur in a face-to-face environment. The victims perceived that their cyberbullies felt empowered to voice discourteous comments, since the bullies believed they were impervious to repercussions through operating behind the veil of a computer screen and/or a screen name. Cyberbullying literature supports this finding. Wildermuth and Davis ( 2012 ) conclude that the internet provides many aggressors with a perception that they can commit acts of cyberaggression with impunity. The authors explain that the asynchronous nature of many electronic forms of communication and the lack of social cues/context cause many abusers to feel that their communication has less of a “real” effect on victims. Disempowerment theory suggests that anonymity can provide a sense of power over victims given bullies’ perceptions of protection behind a computer screen (Kane & Montgomery, 1998 ). Additionally, the theory that the relative anonymity of the internet influences cyberbullying is further evidenced by the work of Cuevas ( 2018 ) and Lloro-Bidart ( 2018 ), two professors who documented their separate, individual experiences with cyberbullying. Whereas cyber vigilantes targeted Cuevas ( 2018 ), a professor in Georgia, for his politically themed social media posts, Lloro-Bidart ( 2018 ), a Californian academic, received verbal assaults for her published, scholarly work related to ecofeminism. In both cases, most of the vitriolic messages directed at the victims originated from non-university affiliated individuals who absconded their identities on the internet.