- Industries Served

- Core Values

- Differentiators

- Employee & Consultant Reviews

- Client Testimonials

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Quality Assurance

- Regulatory Affairs

- Clinical Operations

- Commissioning, Qualification, and Validation

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls

- Pharmacovigilance

- Expert Witness

- Consulting Projects

- Staff Augmentation

- FTE Recruitment

- Functional Service Program

- Browse Consultant CVs

- Start a Consultant Search

- Join Our Consulting Team

- Insider Newsletter

- White Papers

- Case Studies

- The Life Science Rundown

- The Passionate Workforce Podcast

- Regulations and Standards

- The Passionate Workforce

17 April 2024

Clinical Investigator Site Audits: A Guide and Checklist

In the last decade, there has been a significant shift in auditing clinical trials towards a risk-based model. Our approach takes it a step further by incorporating a quality management framework into our clinical audit methodology.

During our audits, we prioritize areas of risk that have the potential to impact patient safety, reliability of study data, and ethical considerations. Additionally, we strive to identify any underlying process deficiencies.

By carefully assessing which processes are affected and the resulting deficiencies, we are able to enhance the efficiency of the corrective and preventive action process (CAPA) by addressing the root cause of process breakdown and finding effective ways to mitigate it.

Our quality system evaluation extends to investigator or vendor sites and sponsors. By utilizing the QM approach, we analyze whether the process deficiencies occurred during the planning, execution, or verification stages.

Through this comprehensive approach, we have delivered clear and impactful audit findings, which have resulted in more successful CAPA measures and sustainable improvements at the process level. In this article, we will delve into the numerous benefits that this approach offers.

| Our services include: Our Quality Assurance team is well-versed in both domestic and international markets, ready to align with your specific compliance requirements and development phase. to enhance and execute your audit program. |

The Basics of Clinical Investigator Site Audits

Clinical investigator site audits are a critical component of clinical research, serving as a quality assurance tool to ensure that the rights, safety, and well-being of human subjects are protected, and that the data generated from clinical trials are accurate, reliable, and verifiable. These audits are conducted to assess compliance with the study protocol, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements.

What are clinical investigator site audits?

Clinical investigator site audits are formal examinations of how clinical trials are conducted at the research sites. They involve a systematic and independent evaluation of the clinical trial processes and procedures to ensure adherence to clinical protocol, regulatory and ethical standards, and data integrity.

The primary reasons for conducting these audits include:

- To protect the rights and welfare of participants.

- To ensure the credibility and reliability of clinical trial data.

- To verify adherence to the approved protocol and amendments.

- To assess the investigators' and site staff's qualifications and abilities to conduct the trial.

- To ensure that the site is following regulatory requirements and GCP standards.

- To identify areas of potential risk and non-compliance.

- To provide feedback and guidance for continuous improvement.

When are they conducted?

Audits can be performed at various stages of a clinical trial:

- Pre-study audits , before the trial commences, to ensure the site is capable of conducting the trial.

- Routine audits , conducted during the trial, to monitor ongoing compliance and data quality.

- For-cause audits , triggered by specific events or concerns that arise during the trial.

- Close-out audits , conducted after trial completion, to review the entirety of the trial conduct and data collection.

How are they performed?

An audit typically involves:

- A review of essential documents, such as the Investigator's Brochure, trial protocol, informed consent forms, and case report forms.

- Interviews with the principal investigator, study coordinators, and other site staff.

- Direct observation of study processes and procedures.

- Verification of data accuracy by comparing source documents (e.g., medical records) with the data reported to the sponsor.

- Assessment of adverse event reporting and handling.

- Evaluation of the storage and handling of investigational products.

What happens after an audit?

The auditor will provide a report detailing findings and observations after an audit. If non-compliance issues or areas for improvement are identified, the site is usually required to respond with a CAPA. Follow-up audits may be conducted to ensure the CAPA is implemented effectively.

How Clinical Study Audits Have Evolved

In the past, clinical audits were performed based on a set cycle and would cover all aspects of a process from beginning to end.

Instead of routine full-process audits, regulators, including the FDA, now recommend a risk-based approach to determine the timing and focus of audits. This shift emphasizes using resources effectively by targeting areas that present the highest organizational risk.

Audit planning now relies on risk assessments that evaluate operational, regulatory, and compliance factors to identify critical areas for review. Auditors concentrate on elements that affect patient safety, ethical considerations, and data integrity, guided by data analysis and risk indicators. This method enhances organizational efficiency by spotlighting areas with the most significant risk potential.

How We're Taking Clinical Study Audits Even Further

We aim to advance risk-based auditing by applying this approach to identifying and reporting audit findings. This method allows us to highlight non-conformances and pinpoint the flawed processes causing these issues.

By linking deficiencies directly to their consequences, we strengthen our case for necessary changes and improvements, facilitating a clearer understanding among stakeholders of the need for action.

Here's an example to illustrate:

| Consider a scenario where a pharmaceutical company consistently encounters data integrity issues during clinical trials. These issues frequently rank as one of the top findings in regulatory inspections and internal audits. A typical audit might reveal that trial data was not recorded in a timely manner, leading to corrective actions focused on immediate data handling practices, such as retraining staff on proper documentation procedures. However, a more insightful approach would be to investigate the underlying processes contributing to these data integrity issues. For instance, it might be discovered that the electronic data capture (EDC) system is not user-friendly, causing delays in data entry. Alternatively, the root cause could be inadequate staffing or a lack of clear data management protocols. By identifying the core process deficiencies—whether they are technological, procedural, or resource-related—the CAPA can be designed to improve the overall quality management system. This could lead to enhancements in the EDC system, revision of data management protocols, or adjustments in staffing models, thereby preventing similar issues across multiple clinical trials and sites. |

The assessment of the QMS at both the investigator site and the sponsor level is crucial for identifying where failures may have occurred throughout the lifecycle of a clinical study.

Here's how an auditor might approach this assessment:

| Was the study set up correctly? If there were issues in the planning phase, such as inadequate training or unclear protocols, this could lead to systemic problems later on. How well was the study executed? Failures here might include incorrect data collection or non-adherence to the study protocol. Did the principal investigator have proper oversight and control mechanisms to catch issues early? A lack of effective monitoring could allow errors to go unnoticed and unaddressed. Were there prompt and effective corrective actions to address identified errors? Failures to act, or ineffective actions, can exacerbate issues and lead to further non-compliance. |

| Were the tools and instructions provided by the sponsor adequate for successful execution? Insufficient guidance can lead to confusion and non-compliance at the study site. Was the sponsor's monitoring of the clinical study site effective? Inadequate monitoring can miss critical issues that compromise data integrity and participant safety Were there performance indicators to identify risks? The absence of such indicators can prevent the early detection of potential problems. How effective were the sponsor's controls to prevent or mitigate risks? Ineffective controls may not adequately protect against the recurrence of issues. |

The Keys to Success

A clinical investigator site audit checklist.

To ensure FDA compliance during clinical trials, firms should have a comprehensive audit checklist. Here's a structured checklist with key areas to review. Keep in mind this is not exhaustive.

| Verify that the Investigator and site staff have adhered to the IRB-approved study protocol. Confirm documentation and on-site storage of all IRB approvals, amendments, and informed consent documents. Review informed consent forms, medical records, and other source documents for completeness and protocol adherence. Check administrative files, correspondence, subject lists, logs, and forms for accuracy and completeness. Ensure informed consent is obtained using IRB-approved forms and that the process is documented. Review financial interest disclosures from investigators and study staff for currency. Validate that electronic systems meet regulatory requirements and staff are trained in their use. Confirm proper receipt, labeling, inventory, storage, and disposal of the drug. Ensure records are stored and retained according to protocol and regulations. Verify submission of all required reports, especially on safety issues or protocol deviations, to the Sponsor. Assess the Investigator's experience, training, and knowledge of GCP and regulatory requirements. Confirm that the Investigator has sufficient qualified staff and facilities to conduct the trial. Ensure trial subjects receive proper medical care and oversight for trial-related decisions. Check for documented IRB approvals for the research application, consent forms, and subject information. Review compliance with randomization and blinding procedures, and documentation for any unblinding. Ensure data reported to the sponsor is accurate, complete, legible, and timely. Confirm submission of research status to the IRB and immediate reporting of serious adverse events to the sponsor. Review the regulatory binder for completeness, including Form FDA 1572, protocol, and IRB correspondence. Verify qualifications, licenses, and training of all study staff. For high-risk trials, review DSMB reports for compliance issues or patterns. Check that all documents and data are organized and stored securely. Ensure procedures are in place for informing subjects, regulatory authorities, and for subject follow-up. Verify that the IRB and regulatory authorities have been informed of the trial's outcome and that all required reports have been submitted. |

The Importance of Independent Auditors

Conducting an independent audit is essential for several reasons. An objective evaluation is chief among these. Independent audits provide a fresh, unbiased perspective on the quality systems of your program, ensuring a thorough and impartial assessment.

Other reasons include:

Avoiding Conflicts of Interest: Audits performed by parties associated with the program may unintentionally overlook or downplay issues due to inherent conflicts of interest.

Regulatory Compliance: Independent audits are critical for uncovering issues proactively, allowing for corrections before regulatory bodies like the FDA identify them during their inspections.

Vendor Compliance: With the significant investment involved in drug development, ensuring that your vendors adhere to quality standards is crucial. Independent audits scrutinize vendor processes to ensure they meet compliance requirements, safeguarding against costly errors that could be flagged by the FDA.

Risk Mitigation: By identifying and addressing gaps in quality systems early, independent audits help mitigate the risk of non-compliance, which can lead to severe consequences such as trial invalidation or mandated remedial actions.

Investment Protection: Independent audits are a proactive step in protecting your drug development program and financial investment by ensuring that all aspects of the program are compliant and on track.

Quality System Development: Firms like ours not only conduct independent audits but also assist in developing robust quality systems and metrics to monitor ongoing compliance, further safeguarding your investment.

Expertise and Consistency: Independent audits are conducted by seasoned professionals who bring expertise and consistency to the audit process, contributing to the reliability and integrity of your compliance efforts.

To ensure comprehensive compliance and protect your drug development program, we always advise using the services of a specialized firm for independent auditing.

The FDA Group has provided expertise and support in maintaining and improving quality systems for ongoing compliance with FDA regulations for hundreds of firms. Contacting a professional audit service can be a crucial step in ensuring the quality and success of your clinical trial and drug development endeavors.

A Few Investigator Site Audit FAQs

Q: How does a Risk-Based Monitoring (RBM) approach affect the audit process of clinical investigator sites?

RBM tailors the audit process to prioritize the most critical and high-risk aspects of clinical trials. In an RBM approach, auditors give precedence to data and processes that are crucial to protecting human subjects and ensuring the reliability of trial results. Although traditional comprehensive audits may still occur, RBM leads to a more efficient allocation of auditing resources, focusing on areas such as informed consent, adherence to the protocol, and the integrity of reported data. Auditors use a combination of on-site and centralized monitoring techniques to identify and mitigate risks throughout the study.

Q: What are the implications of electronic data capture (EDC) systems on site audits?

EDC systems have significantly changed the landscape of clinical data management and, consequently, the audit process. Auditors must now be proficient in validating electronic systems to ensure they are compliant with 21 CFR Part 11 and other relevant regulations. This includes verifying the security of the system, the accuracy of data transfers, and the integrity of electronic records. Auditors must also assess how site personnel are trained on these systems and how data corrections and audit trails are managed.

Q: How are findings from clinical investigator site audits typically communicated to the sponsor and the site?

Audit findings are typically summarized in a formal audit report that is shared with both the sponsor and the site. The report will categorize findings according to their severity, such as critical, major, or minor non-compliance. It will also recommend CAPAs. The site is usually required to respond to the findings, outlining how they will address each issue and prevent its recurrence. The sponsor is responsible for ensuring that the site implements these CAPAs and may conduct follow-up audits to verify compliance.

Q: Can a clinical investigator site fail an audit, and what are the consequences?

Yes. If a site fails an audit and significant non-compliance issues are found that could affect participant safety, data integrity, or violate regulatory requirements, it can have serious consequences. The consequences can range from requiring a response with CAPAs to more severe actions such as suspending the study at the site, disqualifying the investigator, or reporting the findings to regulatory authorities, which can lead to further regulatory acti ons.

Q: What role do auditors play in the continuous improvement of clinical trial processes?

Auditors play a pivotal role in continuous improvement by not only identifying non-compliance and areas for improvement but also by sharing best practices and providing feedback on processes. Their findings can help shape training programs, refine protocols, and improve overall trial conduct. The goal of an audit is not just to find faults but to help the site enhance its processes for future trials.

Q: How are global clinical trials with multiple international sites managed from an auditing perspective?

Global clinical trials present unique challenges due to varying regulatory requirements and cultural differences. Auditors must be knowledgeable about the local regulations of each country involved. Audits may be conducted by local teams with global coordination to ensure consistency. The audit plan for such trials is often developed with a global scope but allows for local flexibility to address specific regional requirements and risks

Need Clinical Investigator Site Audit Support? We Can Help.

When conducting clinical trials on investigational medicinal products or devices, you must show that planning, study conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, analysis, and reporting all meet the ethical and scientific standards for GCP.

As new technologies transform the way clinical research is carried out around the world, keeping ahead of these trends is no small task. Whether you follow a traditional approach to monitoring or are transitioning to a Risk-Based Monitoring (RBM) system, our quality professionals tailor their auditing plans to accommodate your particular needs.

Our quality professionals closely examine your particular study before planning and executing study-specific GCP audits of protocols, investigator sites, trial master files, pharmacovigilance, databases, and reports.

With the help of experienced industry professionals, you can be confident knowing results are credible and accurate while maintaining quality practices throughout the research.

- Mock BIMO Inspections

- Auditing and document review for SOPs, clinical GCP protocols, and reports

- Audits of submission for ethical approval for GCP clinical trials

- Audits of clinical sites

- Audits of Trial Master Files (TMFs)

- Audits of Contract Research Organizations (CROs) and other vendors

Clinical trial audits are tailored to your particular compliance needs and stage of product development. Our Quality Assurance team has performed audits in a variety of markets both domestic and international.

Contact us to learn more about how we can support your auditing program.

Gap Analysis Remediation: A Guide to Resourcing & Implementation

Topics: GCP

Need clinical site audit support?

Contact us to access the industry's top clinical auditors.

Sign up for updates from our blog.

Proprietary talent selection of former FDA and industry professionals amplified by a corporate culture of responsiveness and execution.

US Toll-Free: 1-833-FDA-GROUP

International: +001 508 926 8330

Advarra Clinical Research Network

Onsemble Community

Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

Participants & Advocacy

Advarra Partner Network

Community Advocacy

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC)

Data Monitoring Committee (DMC)

Endpoint Adjudication (EAC)

GxP Services

Research Compliance & Site Operations

Professional Services

Coverage Analysis

Budget Negotiation

Calendar Build

Technology Staffing

Clinical Research Site Training

Research-Ready Training

Custom eLearning

Services for

Sponsors & CROs

Sites & Institutions

BioPharma & Medical Tech

Oncology Research

Decentralized Clinical Trials

Early Phase Research

Research Staffing

Cell and Gene Therapy

Ready to Increase Your Research Productivity?

Solutions for need.

Clinical Trial Management

Clinical Data Management

Research Administration

Study Startup

Site Support and Engagement

Secure Document Exchange

Research Site Cloud

Solutions for Sites

Enterprise Institution CTMS

Health System/Network/Site CTMS

Electronic Consenting System

eSource and Electronic Data Capture

eRegulatory Management System

Research ROI Reporting

Automated Participant Payments

Life Sciences Cloud

Solutions for Sponsors/CROs

Clinical Research Experience Technology

Center for IRB Intelligence

Not Sure Where To Start?

Resource library.

White Papers

Case Studies

Ask the Experts

Frequently Asked Questions

COVID-19 Support

About Advarra

Consulting Opportunities

Leadership Team

Our Experts

Accreditation & Compliance

Join Advarra

Learn more about our company team, careers, and values. Join Advarra’s Talented team to take on engaging work in a dynamic environment.

Critical Steps for Writing an Impactful Clinical Audit Report

The amount of detail required in an audit may vary – ranging from an executive, high-level summary with detailed observations, to an exhaustive, all-inclusive report. A report may only include detailed observations, but it might also provide a list of all the documents reviewed, describing all processes reviewed in detail, along with any audit observations. While it’s critical for the auditor to understand the expectations of whom they are writing the report for, an impactful clinical audit report includes critical information to describe the status of the auditee in a factual way while excluding information that does not add value to the audience.

As defined in ICH E6 (R2), an audit is “a systematic and independent examination of trial-related activities and documents to determine whether the evaluated trial-related activities were conducted, and the data were recorded, analyzed and accurately reported according to the protocol, sponsor’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), good clinical practice (GCP), and the applicable regulatory requirement(s).”

The audit’s output and report are written evaluations of the audit’s results. A typical audit report contains the following sections:

- General information, including who was audited, what was audited, and where the audit occurred

- Executive summary

- Summary of observations (typically in table format)

- What regulations and guidance the audit was conducted against

- Audit scope

- List of staff involved/interviewed in the audit

- Documentation reviewed during the audit

- Narrative section for describing topics covered and facilities reviewed during the audit

- Detailed observations

Industry standards are shifting to focus on building quality into studies and determining critical-to-quality factors (ref. ICH E8 R1 ) and an appropriate risk management approach (ref. ICH E6 R2 ). The audit report should identify how quality and risk management are managed throughout the entirety of the study conduct.

Critical Steps: Executive Summary

The executive summary succinctly describes the audit’s key points. This gives the audience — especially senior management — the key information and audit outcome. It should include whether it is a routine or for-cause audit, site/vendor identification, dates of audit conduct, and if there were any significant concerns or major findings. Research teams need to include a summary of these findings and an overall statement of compliance and acceptability. They should also indicate if the audit was conducted as planned, and if not, it should state the reason for any deviations from the audit plan.

Critical Steps: Observations

Observations are graded relative to the level of non-compliance or deviation. An example of this is formatting observations as critical, major, minor, or recommendation. The definitions of these are usually described in an audit’s SOPs or detailed in the report template. The definitions are based on the impact or potential to subject safety, data integrity, and the protection of human subject rights.

Multiple major audit observations may result in a systemic critical audit observation, even though each of the major observations are not “critical” themselves. Similarly, the same can be said for multiple minor observations, which may result in a major observation. Potential critical observations must be escalated – usually within 24 hours – to a client, so they can take appropriate action right away. Ideally, reports should be reviewed to ensure consistent observation grading and categorization, providing an objective perspective to verify the report is complete and clear.

Observations should be structured clearly. Typically, they start with an overarching statement of the non-compliance, followed by a detailed description of the issue with examples, and references for non-compliance (e.g., applicable regulations, guidelines, SOPs, protocol, or other study-level plans). The details provided must be factual and not based on subjective information.

When describing the critical and major observations, it’s important to also provide an impact statement. This details how the observation potentially impacts patient safety, their rights, data integrity, etc. Critical and major observations require root cause investigation and corrective and preventive action (CAPA), as ICH E6 R2 addendum section 5.20 requires. Minor observations usually only require correction. Observations must stand alone as the auditee will likely receive them separately from the report. The details in the observation must allow for the auditee to understand the observation and enable them to take action to rectify it.

Critical Steps: Trending

In addition to grading observations, observations should also be categorized – and subcategorized if need be – so trending can be performed. Trending is important to understand the organization’s health, giving visibility to repeat or systemic issues. Instead of raising an observation for each individual discrepancy, similar issues should be grouped in one observation wherever possible, instead of surfacing an observation for each individual discrepancy. For example, instead of creating an observation for a missing ethics committee (EC) letter, and another observation for a missing protocol signature page, these can be grouped under investigator site file/essential documents.

Critical Steps: Narrative

The narrative section of the report is where there are differences in the level of detail required by each organization. A best practice is to evaluate what would be value-added for a particular audit and understand the audience who will read the report. Providing too much information may take away from the site’s or vendor’s status. Some examples include:

- For a site audit, it would be relevant to detail the impact of COVID-19, as this could have resulted in missed patient visits or procedures. Facilities also may not have been available for routine patient visits, monitoring visits, or audits

- For a site audit, a detailed description of the facilities and processes relevant to clinical trial’s conduct (e.g., pharmacy, investigational product administration or infusion of investigational product, laboratory sample, and processing) must be included

- For a vendor audit, it may not be practical to describe company background/mergers in detail if the clinical or procurement team can be easily obtained from the internet

- The clinical team may be familiar with the procedures necessary in the protocol; therefore, each step of a procedure does not need to be described in detail, but rather a high-level description would suffice. If any issues with the process or procedure are identified, the narrative references in the observation section rather than including that deviation detail in the narrative

- Noting each reviewed narrative document can distract from the overall activity of the electronic trial master file (eTMF) or investigator site file (ISF) review activity. Staff can note their review for the eTMF and ISF and list any issues in the observation section or on a separate addendum to the report

Providing the correct level of information in an audit is a delicate balance. Critical to successful audit report writing is to understand the report’s audience, the essential information needed for the audience – site or vendor – to execute the plan, as well as sufficient detail allowing for a full understanding and a chance for observation correction.

Tagged in: CRO , fda audits , quality coe , quality management , sponsors

Back to Resources

Ready to Advance Your Clinical Research Capabilities?

Subscribe to our monthly email.

Receive updates monthly about webinars for CEUs, white papers, podcasts, and more.

Advancing Clinical Research: Safer, Smarter, Faster ™

Copyright © 2024 Advarra. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Cookie Policy

- Advanced Features

- Technical Information

- Rapid Study Development

- Intelligent Electronic Data Capture (EDC)

- Streamlined EDC Data Management

- Electronic Patient Reported Outcomes (ePRO)

- Clinical Randomization Technology (IRT) – Clinical Trial Supply Management (RTSM)

- Enterprise Solution

- Registry Solutions

- See ClinicalPURSUIT Live

A Guide to Writing an Impactful Clinical Audit Report

- Clinical Research

- A Guide to Writing an…

From an all-inclusive, exhaustive report to a high-level, executive summary with in-depth observations, the amount of detail required in an audit may vary. While a report may only include a range of observations, it may also provide a list of every document reviewed, describing every process reviewed in detail, as well as any audit observations .

Although it’s important for the auditor to understand the expectations of whom they’re writing the report for, a good clinical audit report comprises critical information to describe the auditee’s status factually while eliminating information that doesn’t add value to the audience.

Here, our clinical trial data management software expert offers a guide to writing an impactful clinical audit report.

The Executive Summary

The executive summary briefly describes the key points of the audit. This gives the audience, for example, the senior management, audit outcome and key information. It should consist of major findings, significant concerns (if any), dates of audit conduct, vendor/site identification, and whether it’s a for-cause or a routine audit . Research teams must include an overall statement of acceptability and compliance as well as a summary of these findings. They should also include if the audit was performed as planned. If not, reasons must be stated as to why it deviated from the audit plan.

Observations

Besides grading observations, observations must be categorized – and if need be, subcategorized. This will help you perform trending. Trending is important as it gives visibility to systemic or repeats issues and helps you understand the organization’s health. Instead of raising an observation for every individual discrepancy, similar groups must be grouped in a single observation wherever possible. For instance, instead of creating an observation for a missing protocol signature page and another observation for a missing EC (ethics committee) letter, these can be grouped under essential documents.

In the narrative section of the report, there are differences in the level of detail required by every organization. Assess what would be value-added for a certain audit and understand the audience who will read the report. Offering too much information may take away from the vendor’s or site’s status.

Clinical PURSUIT offers top-of-the-line clinical trial data management solutions

Whether you’re looking for randomization and drug supply management solutions or electronic patient-reported outcome software, ClinicalPURSUIT can help.

Get in touch with us now for more information!

Related Posts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.62(2); 2021 Feb

Language: English | French

A practical guide to implementing clinical audit

Clinical audit is a quality improvement tool for evaluating and improving patient care and outcomes. This is achieved by systematically reviewing current practices against explicit criteria and measuring the impact of change(s) introduced to generate improvement. The clinical audit process can be described by “Plan,” “Do,” “Study,” “Act” phases that comprise an audit cycle. The phases are moved through in turn to attempt quality improvement. Clinical audits are widely used in human medicine at both local (individual clinic or hospital) and national (to achieve nationwide improvements in care) levels. Substantial and sustained improvements in patient care have been attributed to the use of clinical audits. Clinical audits have been described in the veterinary literature since the 1990s, but their adoption does not appear widespread. This paper is intended as a practical, “how to” guide to applying clinical audit in veterinary practice.

Résumé

Un guide pratique pour la mise en place d’un audit clinique . Un audit clinique est un outil d’amélioration de la qualité pour évaluer et améliorer les soins aux patients et les résultats. Ceci est obtenu en révisant systématiquement les pratiques actuelles envers des critères spécifiques et en mesurant l’impact des changements introduits pour générer une amélioration. Le processus d’audit clinique peut être décrit par les phases « Planifier », « Exécuter », « Examiner » et « Agir » qu’incluent un cycle d’audit. Le passage en séquence des phases vise une amélioration de la qualité. Les audits cliniques sont utilisés extensivement en médecine humaine à l’échelle locale (clinique individuelle ou hôpital) et nationale (pour atteindre des améliorations des soins à la grandeur du pays). Des améliorations substantielles et soutenues dans les soins aux patients ont été attribuées à l’utilisation des audits cliniques. Les audits cliniques ont été décrits dans la littérature vétérinaire depuis le début des années 1990, mais l’adhésion ne semble pas être répandue. Cet article se veut un guide pratique sur le « comment faire » pour mettre en application un audit clinique en pratique vétérinaire.

(Traduit par D r Serge Messier)

Introduction

Clinical audit is a quality improvement tool that is used to monitor, assess, and improve the quality of care in human and veterinary medicine ( 1 – 7 ). The procedure involves measuring an outcome or process and comparing this to current evidence or best practice, then implementing changes to improve the quality of care ( 8 , 9 ). In human medicine, clinical audit is considered a standard of care ( 2 , 9 , 10 ). For example, The National Hip Fracture Database (UK) has allowed institutions to audit the care they provide to hip fracture patients according to national standards ( 2 ). Through clinical audit, 1 facility was successful in shortening the median time to surgery and discharged more patients to rehabilitation units following a hip fracture ( 2 ). In veterinary medicine, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) includes clinical audit in its Practice Standards Scheme, in which approximately 65% of UK practices participate ( 11 ). Performing clinical audit is a requirement for practices accredited as Veterinary Hospitals and encouraged for those accredited as General Practice and Emergency Service Clinics ( 11 ). However, as audits are not frequently published (there is no requirement for publication in the Practice Standards Scheme), it is unclear to what extent clinical audits are being conducted ( 5 ). At the time of writing, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), and the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) do not appear to provide resources on clinical audit. The aim of this paper is to provide a practical “how-to” guide on performing clinical audit. This guide is supplemented by a fictitious example of a clinical audit ( Appendix , “Antimicrobial use in bacterial cystitis”). Key principles are illustrated with examples, including one based on a clinical audit performed on the subject of postoperative hypothermia in dogs in a large referral hospital ( 4 ).

Antimicrobial use in bacterial cystitis.

| A small animal clinic is looking into performing a clinical audit. The group begins by answering the 3 preparatory questions. After reading the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association recommendations on judicious use of antimicrobials, the veterinary team would like to improve their diagnosis and treatment of bacterial cystitis in dogs ( ). The team agrees to follow the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) guidelines ( ). Based on their clinical experience, the team identifies the following points from the ISCAID guidelines as areas that would qualify as improvement ( ): An initial short audit cycle was conducted over a week and identified that very few sporadic cystitis cases were being cultured and that treatment duration was usually 7 to 10 days. Upon further discussion with the staff there was no clear definition for what was considered sporadic cystitis and therefore what length of treatment was required. The staff created a checklist to aid in identifying cases of sporadic cystitis which included the following i) less than 3 episodes of cystitis in the preceding 12 months; ii) healthy non-pregnant females or neutered males; iii) no known urinary tract anatomical or functional abnormalities or co-morbidities. This information was then brought to the Plan stage. |

| The team’s purpose statement was to improve antimicrobial use following the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial cystitis by: To help achieve these goals the RVTs were in charge of filling the prescriptions and confirming the duration of treatment. |

| One RVT was allocated 2 h a week to collect the data. This involved searching the computer database for “cystitis,” verifying the duration of antimicrobial treatment and determining whether a urine culture was performed. |

| After the 2-month period, the team reviewed the data. A bar graph was used to compare the number of cystitis cases against those cultured ( ). Following discussion, the team realized that discrepancies in performing cultures were largely explained by different levels of comfort with collecting urine ultrasound-guided cystocentesis. A run chart was plotted to monitor treatment duration. The team was happy to see a trend towards treating between 3 to 5 days except for 2 astronomical points ( ). On further investigation they realized that this case was from a locum who was not made aware of the practice policy. |

| To improve urine culturing, the clinic elected to support a continuing education day on basic ultrasonography. Once the CE course was completed, a new clinical audit cycle was performed. |

Materials and methods

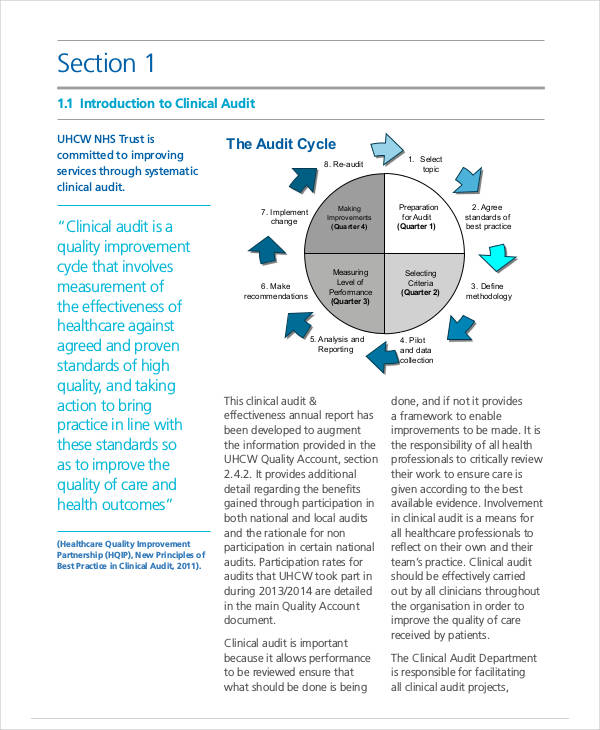

The process of achieving sustained improvement in a complex system, such as the provision of veterinary care, may not be straightforward ( 12 , 13 ). This is because of the complexity of the system and the habits of the workforce. A successful change in practice is reflected in a measurable improvement that can be maintained ( 7 – 9 , 13 , 14 ). Common to most existing descriptions of clinical audit is the concept that an audit is cyclical, repeated at intervals to track performance. Multiple cycles may be necessary to achieve the desired changes, particularly in complex processes or where the key activities resulting in change are not obvious. While several audit cycle models exist, one which has been widely used in the domains of both business and medicine, is the “Model for Improvement” ( 9 , 13 ). The original model consists of 3 preparatory questions linked to a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle ( Figure 1 ). “Plan” is identifying the process(es) and outcome(s) to be studied and how data will be collected, “Do” is collecting the data, “Study” is interpreting the collected data, and “Act” brings the current audit cycle to completion by reviewing the results and planning for ongoing improvement. The following is an elaboration of each component of the model.

The audit cycle, showing the 4 necessary steps of a complete audit cycle, from planning an audit (“Plan”), to the collection and analysis of data (“Do” and “Study”) and identifying steps leading towards improvement (“Act”). The cycle is intended to be repeated with the goal of continuous improvement. Adapted from Langley et al ( 13 ).

Preparatory questions

The 3 preparatory questions of the Model for Improvement precede the first step, the “Plan” stage of the PDSA cycle and improve the likelihood of conducting a successful audit ( 13 ). The questions are: 1. “What are we trying to accomplish?” 2. “How will we know that a change is an improvement?” 3. “What changes can we make that will result in an improvement?”

1. “What are we trying to accomplish?”

Identify the aim of the clinical audit. The selected topic may be determined by relevance to an individual practitioner or clinic, with common topics often related to patient/staff safety, clinical practice or finances ( Table 1 ). When choosing a topic, it is essential that staff understand the rationale for the desired improvement, as this will build buy-in and improve compliance with introduced changes. Ideally, the selected topic has an associated set of explicit criteria/guidelines based on current evidence, against which performance can be compared [e.g., the use of physiologic monitors during cardiopulmonary resuscitation ( 15 )]. Where guidelines exist, they should be written in a way that identifies measurable criteria that have been shown to improve the quality of care ( 16 , 17 ). Unfortunately, in veterinary medicine the evidence-base for outcome criteria or the existence of guidelines is often limited, resulting in a reliance on a combination of evidence and expert opinion, such as seen in consensus guidelines ( 15 , 18 ). Where neither evidence-based criteria nor consensus guidelines exist, criteria may be derived from observation of achievements in comparable settings: this is known as benchmarking. For example, the RCVS Knowledge website has a cumulative online database reporting on the outcomes of neutering procedures (spays and neuters in dogs, cats, and rabbits; currently reports outcomes from over 39 000 procedures) ( 19 ). These outcome data can be used as a benchmark for performance and to potentially identify areas for clinical audit/investigation. For example, the current data show that approximately 1% of cat castrations and 10% of dog castrations have a postoperative complication requiring medical treatment ( 19 ). So, if a practice was experiencing a higher incidence of complications requiring medical treatment with their canine neuters, such as 15%, this suggests an area for improvement and a percentage goal to achieve.

Sample subjects for clinical audit.

| Subject | Potential measurement | Associated criteria/guidelines? | Potential target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staff safety | |||

| Bite wounds | Cat bites that penetrate skin | None | Zero cat bites |

| Patients escaping | Patients escaping kennel, patients loose on walks | None | Zero kennel or walk escapes |

| Finances | |||

| Appointment scheduling | Client wait time beyond scheduled appointment time | None | Within 5 min |

| Emergencies | Returning calls for after hour emergencies | None | Triaging calls within 30 min |

| Clinical practice | |||

| Pre-operative antimicrobials | Antimicrobial administration time and surgical incision time | Within 30 to 60 min of surgery ( ) | Within 60 min |

| Diabetes mellitus management | Appropriate dietary management | American Anima Hospital Association diabetes guidelines ( ) | Achieving and maintaining ideal body mass |

Using our hypothermia example, the response to “What are we trying to accomplish?” would be a reduction in incidence of postoperative hypothermia in dogs. A quick literature search in human and veterinary medicine reveals multiple adverse effects of perioperative hypothermia in humans and a high incidence of postoperative hypothermia in dogs and cats ( 4 , 20 – 23 ). The latter provides indirect support for the perception that the clinic has a high incidence of post-operative hypothermia (an example of benchmarking). The reported incidence of hypothermia in the literature can be used as a performance target, with the goal of providing a similar or better level of care. It is important with this first question that all staff understand the importance of the task identified for improvement. By taking the time to explain the potential adverse effects of hypothermia on patients, staff are encouraged to support the audit and comply with implemented changes. For example, kennel staff members may be more vigilant in monitoring patients’ post-operative temperature if they understand the potential consequences of hypothermia.

2. “How will we know that a change is an improvement?”

It is often easy to introduce a change, but it may not be straightforward, particularly in complex systems, to know if that change has a positive effect. Some form of data collection confirms that a change results in an improvement (and supports future assessments of performance and improves support from staff ). The data collected should provide information relevant to the outcome of interest. In its simplest form, the outcome itself can be measured (e.g., incidence of postoperative hypothermia). However, in complex systems or to better understand weaknesses in a system, it is often helpful to measure processes within a system (e.g., How many cases had active warming applied? Was rectal temperature recorded during surgery?). It is often tempting to focus on outcome measures as these reflect success (or failure). However, focusing on an outcome can be frustrating when it is unclear which processes resulted in an improved outcome. Additionally, if an instituted change does not result in improvement and data collection was limited to an outcome, it is impossible to know if the underlying processes were performed properly or if the right processes were altered, or both [e.g., if the change is to provide active warming during all surgeries and the incidence of hypothermia (outcome measurement) remains unchanged, the cause(s) of failure to generate improvement is unknown]. Similarly, if improvement occurs, the assumption is that this resulted entirely from the introduced change, unless a measure of process(es) is included to ensure that the change was implemented as planned or that other processes were affected/unaffected as predicted (e.g., the incidence of hypothermia drops when active warmers are made available, but perhaps the timing of active warmer use also has an important effect on the incidence of hypothermia). Therefore, including process measurements in an audit provides richer information than focusing exclusively on outcome.

Process measurements relate to specific activities (actions or steps) associated with outcomes. Documenting processes is often more sensitive than measuring outcomes ( 8 , 24 ). Process measurements may be the only feasible option when the outcome of interest is delayed (e.g., time to death or disease development) or the outcome occurs infrequently (e.g., anesthetic death). However, it is not always evident which processes influence outcome and to what extent (not all change in a system will result in improvement) ( 13 ). Ideally, process measurement selection would focus on those with the greatest influence on outcome and amenability to measurement.

Returning to the hypothermia example, focusing on the outcome alone (hypothermia at recovery) could miss processes with a direct and important effect on outcome. These could include, when/if rectal temperatures are recorded in the perioperative period, the use of active warmers (timing of application, temperature setting, availability of warmers), and procedure duration.

3. “What changes can we make that will result in an improvement?”

In veterinary medicine, evidence linking specific activities to beneficial outcomes can be sparse. Methods to help identify items for change (a “needs assessment”) may include conducting initial surveys, receiving feedback from relevant parties, and collecting initial data on performance. In complex systems in which numerous outcomes could be improved, an initial survey of users may help identify which outcomes to initially pursue ( 13 ). For example, with the goal of improved client service, a survey of clients may identify that delays in scheduled appointments are less important than segregated waiting areas for dogs and cats. This information can then be discussed with staff to explore if, and how, suggested changes can be introduced (e.g., feasibility of a screen to provide a visual barrier between cats and dogs), followed by an audit cycle to assess the impact of that change (survey of clients, record of pet density in segregated areas, feedback from staff on effectiveness). When considering a clinical audit, seeking contributions from relevant parties can identify items that may contribute to, or obstruct, the success of an audit (e.g., achieving an outcome of reducing medication errors is more likely to be successful if the number of different concentration preparations is minimized). Performing a short audit cycle, with limited scope, can enable rapid feedback and provide information on the impact of the tested changes. This can be valuable when it is unclear if a change is likely to be successful or there is a financial commitment associated with a change in practice. The resulting information could then be used in a larger scale clinical audit.

In the hypothermia example, it was important to verify the perception that the incidence of postoperative hypothermia was high. An initial, short period of data collection (over 1 wk) showed that 88% of dogs were hypothermic at extubation and that post-operative temperature recording, and warming were inconsistent. Discussing the findings with the registered veterinary technicians (RVTs) revealed that there was no consistent definition of hypothermia applied in the clinic, there was no standard practice for frequency of temperature measurements, and the availability of forced air warmers was limited ( 4 ). This process of acting on the perception that hypothermia was occurring frequently by collecting data to document its incidence and discussing the findings, was effectively a short audit cycle, the outcome of which was to confirm that a problem (hypothermia) existed, and to identify barriers and opportunities for improvement. These findings were incorporated into the “Plan” stage of the larger, more comprehensive, PDSA cycle.

Step 1: “Plan” (preparing for the clinical audit)

The planning stage is critical to the success of the audit cycle and considers: identification of the process(es)/outcome(s) to be studied based upon responses to the 3 preparatory questions (above), identification of the Who, What, When, and Where of the cycle, and preparation for data collection (“Do” phase) ( 8 , 13 ). The 3 preparatory questions should result in a statement of the aim/purpose of the audit cycle ( 1 ). An example of a purpose statement could be: “To improve the management of postoperative hypothermia in dogs presenting for non-urgent procedures.” However, such a statement is vague because no specific target is identified. Should the target be to achieve 0% hypothermia after surgery? This is ideal, but probably unrealistic. A more realistic target might be, “90% of dogs returning to normothermia within 4 h after surgery.” This latter statement recognizes that maintaining normothermia during surgery is difficult, but that management of hypothermia can be improved.

Once the purpose statement has been created, the groups involved and resources required are identified ( 7 ). This allows an appraisal of whether the selected outcome can be realistically manipulated and (hopefully) improved ( 14 ). For the hypothermia example, it is important to ensure that there are sufficient resources (staff and equipment) to support the goal. Similarly, it is important that key parties are invested in the project: presenting the current situation (including the current incidence of hypothermia), the aim of the audit cycle, the reasons why reducing the incidence of hypothermia is important, the planned changes and contributions of staff, are more likely to result in support and eventual success ( 5 ). Absence of staff involvement is a common source of failure or of resistance to bring about change ( 8 , 27 ). Similarly, a key aspect of successful audit is creating an environment in which the goal is improvement rather than placing blame on specific groups or individuals ( 8 ). Finally, an initial timeframe for data collection (the “Do” phase) can be set out. This is determined based upon local constraints but should set a minimum time to have a chance of identifying an improvement (if one were to occur; this could naturally be determined by caseload, for example) and be short enough that lack of success is not unnecessarily prolonged. Visualizing and interpreting data as they are collected (see Step 3: “Study”) can identify when change has occurred and a suitable time to stop data collection.

From this “Plan” stage, the following was described for the hypothermia clinical audit:

- Purpose statement: “to have 90% of dogs return to normothermia within 4 h after surgery.”

- The results of the short data collection period (identifying an 88% incidence of postoperative hypothermia) were presented to the practice, with attendance by the majority of veterinarians, registered veterinary technicians, and technician assistants. An in-person meeting was appropriate for the size of clinic but for larger clinics, or those in which veterinarians work in shifts, more than 1 meeting, or use of e-mail (with a deadline for comments) or posters (for example) could help ensure information was widely communicated.

- A general discussion achieved a consensus to: a. measure rectal temperature hourly when hypothermia was identified at extubation (included in recovery area monitoring by technicians: Who and Where); b. implement a practice-wide target temperature of 37.5°C (What); c. use forced air warmers and continue temperature measurements until the target temperature was achieved; and d. move unused forced air warmers from the surgical floor to the recovery area at the end of the day to ensure equipment availability. Data collection was planned for 1 mo (When) with a view to interpreting the data at this stage (Step 3: “Study”) and deciding the next step(s) (Step 4: “Act”).

Step 2: “Do” (carrying out the plan)

This is the data collection phase. Once the audit is in progress, monitoring the data collection process itself helps ensure that data are being collected properly (staff included in data collection should be appropriately instructed and supported) ( 28 ). Time to collect data should be budgeted into the workload of participants to maximize the likelihood of complete and accurate reporting. There should be the opportunity to record problems encountered as these will help identify causes of audit failure, or limited improvement gains, and can be incorporated in future audit cycles. This could be achieved informally, such as asking for feedback during regular clinic meetings/rounds, or by making available a box in which suggestions can be placed, or providing an e-mail contact (specific person or dedicated e-mail address). Ongoing visualization of data can provide rapid feedback on progress towards achieving a change and serve to motivate participants if goals are set.

In large-scale, multicenter/national audits it can be invaluable to have people dedicated to collecting data, monitoring progress, and providing feedback ( 29 ). This approach facilitates early identification of factors contributing to likely failure to implement change(s), which can then be addressed. Software can also be used to facilitate data collection ( 30 ).

In the hypothermia example, a poster summarizing the changes being implemented was prominently displayed. Additionally, the line in the postoperative record sheet for recording temperature was highlighted. To minimize data loss, a designated person was responsible for inputting data into an electronic spreadsheet weekly.

Step 3: “Study” (data analysis and interpretation)

Following data collection, graphs are often used to visualize and interpret the data. The data should be discussed among colleagues to obtain a wide range of perspectives ( 9 ). This discussion is essential to complete the current audit cycle (moving to the “Act” phase) and prepare for future audits.

A common method of displaying collected clinical audit data, which facilitates tracking of progress, is the run chart ( Figure 2 ) ( 31 ). Run charts are an example of control charts and more sophisticated forms, such as cumulative summation plots, are used in statistical process control, a formal technique to evaluate quality control/improvement ( 3 , 32 , 33 ). Run charts facilitate rapid assessment of the data as they are collected, allowing users to see emerging patterns, including deviations from an audit goal. They are simple and fast to compile, and easy to interpret. The x-axis of a run chart represents a measure of time, such as days or visit/procedure number. The y-axis represents the subject of study e.g., client time in waiting room ( Figure 2 ). Targets to achieve or avoid can be plotted on the y-axis (e.g., Figure 2 shows a desired maximum wait time of 10 min after scheduled appointment time), enabling a rapid assessment of progress and motivation.

Run chart of fictitious data illustrating percentage of clients meeting a goal of 10 min or less (dashed horizontal line) for time spent waiting for appointment to start. The historical median wait time is 15 min (dotted horizontal line). A trend (5 or more consecutive points moving in the same direction) and an astronomical point (deviant data point) are identified. These could result from the knock-on effect of an appointment running late and a cancellation, respectively. The impact of a new DVM requiring longer appointments contrasts with an experienced practitioner (cases 32 onwards).

Beyond subjective observations, several standardized rules can be applied to aid run chart interpretation, including identification of a “trend” and “astronomical point” ( 13 , 31 ). These rules help identify non-random changes in the data and limit the risk of over-interpreting small changes. A trend is identified when 5 (or more) consecutive data points all move in the same direction (either upwards or downwards). Identifying an astronomical point is based on subjective evaluation of the run chart and is indicated by a datum that is striking by its deviation from the adjacent data. More complex interpretations of run charts can also be applied using statistical methods ( 3 , 13 , 31 , 34 ).

For the hypothermia clinical audit, a box plot was used to track the percentage of animals achieving normothermia within 4 h over the 4 wk following the introduction of the temperature management changes ( Figure 3a ). Data were compiled weekly as this fitted in with the work schedule of the person responsible for managing data. A run chart, reflecting rectal temperatures at the target 4-hour time point for individual dogs could also be applied to provide detail at an individual case level ( Figure 3b ).

a — Circles indicate percentage of animals normothermic at 4 h after recovery for 6 days of the week (Monday–Saturday). Box plot (box limits are range, central horizontal line is median: calculated from daily percentage values). The initial positive effects of changes introduced during the audit begin to wane in weeks 3 and 4 (lower median and daily percentages and increased data variability). Tracking performance identifies this change and can be used to trigger a more detailed investigation to understand the basis of the change (e.g., individual case tracking, Figure 3b) or a further audit cycle. b — Run chart showing rectal temperature for sequential cases anesthetized before (cases 1–9) and after (cases 10–28) warming management changes introduced (“Temp mx change”). Changes result in more cases achieving the target temperature and less variability between cases.

The duration of data collection is somewhat arbitrary, often based on a prediction of caseload so that enough cases are collected to be representative. In general, though collecting more data is informative, compliance in maintaining introduced changes and/or continuing data collection is likely to wane over time (especially if data are not visualized on an ongoing basis). In contrast, too short a period of data collection may not provide an accurate reflection of reality and improvements may reflect the Hawthorne effect (a change in behavior as a result of being observed), with a return to previous performance levels once data collection stops ( 35 , 36 ).

Step 4: “Act” (decision for further action based on results)

After data collection and interpretion of results, the current audit cycle is completed by defining and implementing further action to continue improvement (or address identified problems). This could be as simple as intermittent periods of data collection to confirm improvements are maintained. Further audit cycles may be planned, with the goal of continuous improvement (or to test alternative approaches in the case of an unsuccessful outcome). The results of the hypothermia audit were presented to clinic staff, providing the opportunity to reflect on the process and discuss strategies for further improvement (the initial target was achieved but a small number of animals remained hypothermic beyond the 4-hour goal).

Factors associated with failure of clinical audit

Successful audit depends on a careful selection of the audit subject (see preparatory questions) and a supportive environment ( 9 , 27 ). Environment can be considered as structure and culture ( 8 ). Structure refers to ensuring adequate time and resources are available to conduct an audit (from preparation through to data collection and presentation). This could include time to identify relevant guidelines when establishing outcomes/processes to measure and audit targets as well as the time and resources to collect and interpret data. Culture refers to a collective desire to promote and sustain improvement, including supporting openness, so that errors/failures can be identified without blame ( 37 , 38 ). All phases of the audit cycle are more likely to be successful if the process is inclusive, with staff involvement. The extent of involvement varies, from consultation and discussion during the planning phase to participation in data collection and review of results ( 39 ). There is an important distinction between a successful audit cycle, that is, completion of the audit cycle, and success in generating an improvement. Failure to achieve improvement does not necessarily constitute a failed audit process: it may be that the action taken had limited impact on the outcome of interest or was not closely related to the outcome. Failure to achieve improvement still provides useful information to be incorporated in subsequent audit cycles.

Ethical review for clinical audits

The overarching goal of clinical audit is quality improvement, resulting from observing and evaluating processes and outcomes against explicit criteria. Thus, the end result should be an improvement in the quality of care. Understanding the audit cycle process provides a framework for ethical review. It is simplistic to assume that clinical audit does not require ethical review ( 28 , 40 – 43 ). Though clinical audit often differs from prospective clinical research in that animals are not randomized to receive different treatments (with the possibility that a subject receives a less effective/placebo treatment), there are several areas that warrant ethical review: 1. There may be randomization to assess the effect of different interventions in improving standard of care; 2. The change introduced with the goal of improving care may be associated with risk (perceived or actual); 3. Safeguarding of patient data; 4. A radical change in care/practice that could have unforeseen effects; and 5. Re-allocation of resources from other patients as a result of a change in care.

Publishing quality improvement studies

The number of published clinical audits in veterinary medicine is limited, although it is unclear if this reflects the number of audits performed, the selection process of journals or the number of audits submitted for publication ( 5 ). The publication of clinical audits should be encouraged. This is particularly important in veterinary medicine, where evidence of criteria associated with improvement is limited: published audits will disseminate information on the success/failure of changes implemented. Furthermore, as evidence-based guidelines are developed, clinical audit can help evaluate if guidelines are achievable in practice and written in a way that the relationship between process(es) and outcome is clear. To facilitate clinical audit publishing and standardize reporting, reporting guidelines are available: SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) ( 44 , 45 ). These guidelines are also helpful when planning clinical audits, providing a framework of items to consider.

The quality of clinical audit is reflected by completion of the audit (PDSA) cycle, as well as the selection of measurable criteria, reliable and accurate data collection and analysis, and reporting and interpretation of the results ( 8 ).

In conclusion, clinical audit has the potential to promote and maintain high standards of patient care. Available literature shows that clinical audit is being discussed and applied in veterinary medicine ( 1 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 30 , 46 – 48 ), with evidence that complete audit cycles are being performed ( 1 , 3 , 7 , 47 – 49 ). A current barrier to the widespread adoption of clinical audit may be a relative lack of evidence-based guidelines in veterinary medicine. Nevertheless, clinical audit can and should be used to assess performance against widely accepted (best-practice) standards of care. The importance of clinical audit cannot be overstated. With the increase in volume of published literature, a gradual move towards evidence-based veterinary medicine, increased focus on the relationship between human and veterinary medicine (“One Health”), and increasing public awareness, steady improvement of practice standards is a challenging yet critical task. Clinical audit is a useful, accessible, under-utilized tool to achieve this goal.

a — Bar graph of fictitious data showing relationship between weekly cystitis cases and number of cultures performed. b — Run chart documenting duration of antimicrobial prescriptions for fictional cases of cystitis. Upper and lower broken horizontal lines indicate target prescription duration window. Case 17 could be classified as an astronomical point (see text for details), warranting investigation.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (424022-201). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank Dr. Vivian Leung for designing Figure 1 and Dr. Pam Mosedale, Lead Assessor, Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Practice Standards Scheme, for helpful comments on the sections referring to the Practice Standards Scheme. CVJ

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office ( gro.vmca-amvc@nothguorbh ) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

Not a member?

Find out what The Global Health Network can do for you. Register now.

Member Sites A network of members around the world. Join now.

- 1000 Challenge

- ODIN Wastewater Surveillance Project

- CEPI Technical Resources

- UK Overseas Territories Public Health Network

- Global Malaria Research

- Global Outbreaks Research

- Sub-Saharan Congenital Anomalies Network

- Global Pathogen Variants

- Global Health Data Science

- AI for Global Health Research

- MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL

- Virtual Biorepository

- Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

- Rapid Support Team

- The Global Health Network Africa

- The Global Health Network Asia

- The Global Health Network LAC

- Global Health Bioethics

- Global Pandemic Planning

- EPIDEMIC ETHICS

- Global Vector Hub

- Global Health Economics

- LactaHub – Breastfeeding Knowledge

- Global Birth Defects

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- Human Infection Studies

- EDCTP Knowledge Hub

- CHAIN Network

- Brain Infections Global

- Research Capacity Network

- Global Research Nurses

- ZIKAlliance

- TDR Fellows

- Global Health Coordinators

- Global Health Laboratories

- Global Health Methodology Research

- Global Health Social Science

- Global Health Trials

- Zika Infection

- Global Musculoskeletal

- Global Pharmacovigilance

- Global Pregnancy CoLab

- INTERGROWTH-21ˢᵗ

- East African Consortium for Clinical Research

- Women in Global Health Research

- Global Health Research Management

- Coronavirus

Research Tools Resources designed to help you.

- Site Finder

- Process Map

- Global Health Training Centre

- Resources Gateway

- Global Health Research Process Map

- About This Site

Downloadable Templates and Tools for Clinical Research

Welcome to global health trials' tools and templates library. please note that this page has been updated for 2015 following a quality check and review of the templates, and many new ones have been added. please click on the orange text to download each template., the templates below have been shared by other groups, and are free to use and adapt for your researchstudies. please ensure that you read and adapt them carefully for your own setting, and that you reference global health trials and the global health network when you use them. to share your own templates and sops, or comment on these, please email [email protected]. we look forward to hearing from you.

These templates and tools are ordered by category, so please scroll down to find what you need.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| /td>< |

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

To share your own templates and SOPs, or comment on these, please email [email protected]. We look forward to hearing from you!

- Webinar on community engagement in clinical research involving pregnant women

- Free Webinar: Science, technology and innovation for upskilling knowledge-based economies in Africa

- Open Public Consultation on “Strengthened cooperation against vaccine preventable diseases”

Trial Operations Trial Management Ethics and Informed Consent Resources Trial Design Data Management and Statistics

training

This is Degena Bahrey Tadesse from Tigray, Ethiopia. I am new for this web I am assistant professor in Adult Health Nursing Could you share me the sample/templet research proposal for Global Research Nurses Pump-priming Grants 2023: Research Project Award

I have learned lot..Thanks..

i was wondering why there is no SOP on laboratory procedures ?

Hi, Can you provide me the SOP for electronic signatures in Clinical trial

Do you have an "SOP for Telephonic site selection visit". Kindly Share on my registered mail ID

Thank you for sharing the resources. It is very kind of you.

Hi These tolls are very useful! Thank you

Do you have a task and responsability matrix template for clinical trial managment ? Best

I am very much happy to find myself here as a clinician

Dear Getrude

We have a free 14-module course on research ethics on our training centre; you'll receive a certificate if you complete all the modules and quizzes. You can take it in your own time. Just visit 'Training centre' in the tabs above, then 'short courses'.

Kind regards The Editorial Team

need modules on free online gcp course on research ethics

Estimados: me parece excelente el aporte que han hecho dado que aporta. por un lado a mejorar la transparencia del trabajo como a facilitar el seguimiento y supervisión de los mismos. Muchas gracias por ello

We also have an up to date list of global health events available here: https://globalhealthtrials.tghn.org/community/training-events/

Dear Nazish

Thank you, I am glad you found the seminars and the training courses useful. We list many training events (all relevant to Global Health, and as many of them as possible are either free or subsidised) on the 'community' web pages above. Keep an eye on those for events and activities which you can get involved with. Also, if you post an 'introduction' on the introduction group stating where you are from and your research interests, we can keep you updated of relevant local events.

Thanks so much. These are very helpful seminars. Please let me know any other websites/links that provide free or inexpensive lectures on clinical Research. Appreciate your help.

Hi Nazish, and welcome to the Network. The items here are downloadable templates for you to use; it sounds like you may be seeking lectures and eLearning courses? If so - no problem! You can find free seminars with sound and slides here: https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/webinars/ , and you can find free, certified eLearning courses here: https://globalhealthtrials.tghn.org/elearning . Certificates are awarded for the eLearning courses for those scoring over 80% in the quiz at the end of each course. If you need anything else, do ask! Kind regards The Editorial Team

Hi, I am new to this website and also to the Clinical Research Industry for that matter I only am able to see the PDF of these courses, just wanted to know are these audio lectures and also happen to have audio clips that go with the pdf?

This site is impeccable and very useful for my job!!!!

Thank you for your kind comments.

Fantastic resources