Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

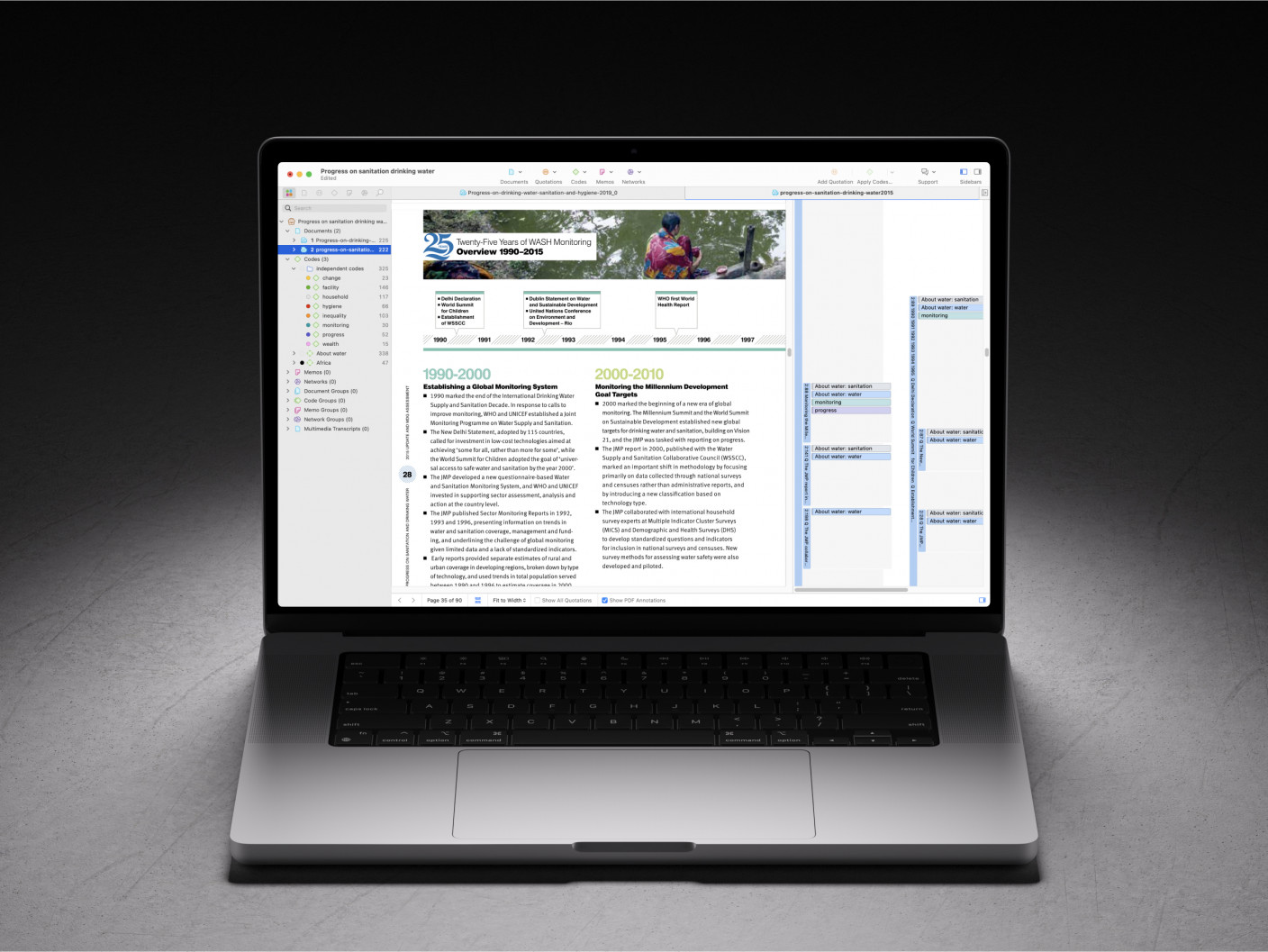

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

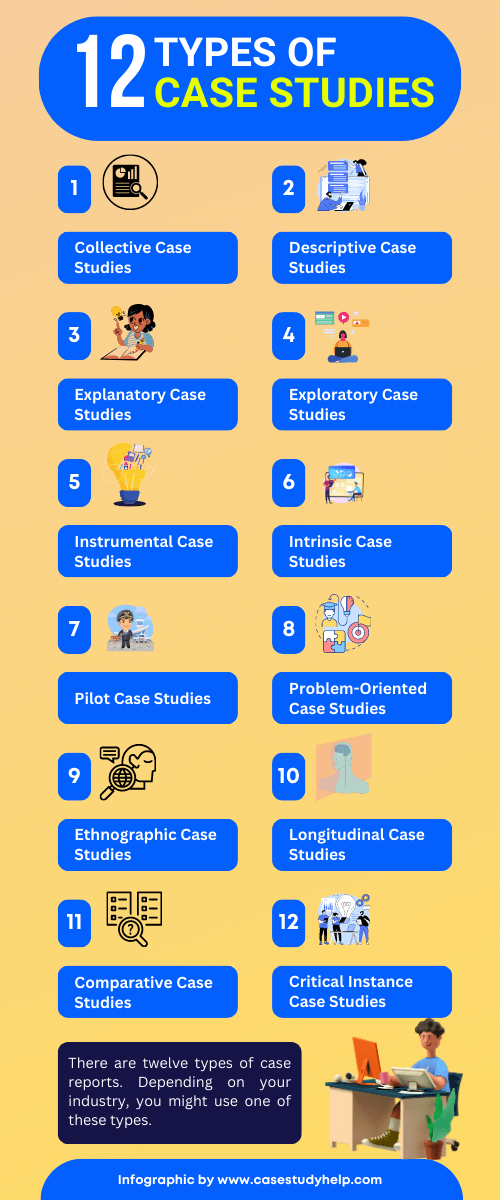

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is a Case Study? Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost Leave a Comment

Case Study Definition

A case study is an in-depth investigation of a single person, group, event, or community. This research method involves intensively analyzing a subject to understand its complexity and context. The richness of a case study comes from its ability to capture detailed, qualitative data that can offer insights into a process or subject matter that other research methods might miss.

A case study strives for a holistic understanding of events or situations by examining all relevant variables. They are ideal for exploring ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions in contexts where the researcher has limited control over events in real-life settings. Unlike narrowly focused experiments, these projects seek a comprehensive understanding of events or situations.

In a case study, researchers gather data through various methods such as participant observation, interviews, tests, record examinations, and writing samples. Unlike statistically-based studies that seek only quantifiable data, a case study attempts to uncover new variables and pose questions for subsequent research.

A case study is particularly beneficial when your research:

- Requires a deep, contextual understanding of a specific case.

- Needs to explore or generate hypotheses rather than test them.

- Focuses on a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context.

Learn more about Other Types of Experimental Design .

Case Study Examples

Various fields utilize case studies, including the following:

- Social sciences : For understanding complex social phenomena.

- Business : For analyzing corporate strategies and business decisions.

- Healthcare : For detailed patient studies and medical research.

- Education : For understanding educational methods and policies.

- Law : For in-depth analysis of legal cases.

For example, consider a case study in a business setting where a startup struggles to scale. Researchers might examine the startup’s strategies, market conditions, management decisions, and competition. Interviews with the CEO, employees, and customers, alongside an analysis of financial data, could offer insights into the challenges and potential solutions for the startup. This research could serve as a valuable lesson for other emerging businesses.

See below for other examples.

| What impact does urban green space have on mental health in high-density cities? | Assess a green space development in Tokyo and its effects on resident mental health. |

| How do small businesses adapt to rapid technological changes? | Examine a small business in Silicon Valley adapting to new tech trends. |

| What strategies are effective in reducing plastic waste in coastal cities? | Study plastic waste management initiatives in Barcelona. |

| How do educational approaches differ in addressing diverse learning needs? | Investigate a specialized school’s approach to inclusive education in Sweden. |

| How does community involvement influence the success of public health initiatives? | Evaluate a community-led health program in rural India. |

| What are the challenges and successes of renewable energy adoption in developing countries? | Assess solar power implementation in a Kenyan village. |

Types of Case Studies

Several standard types of case studies exist that vary based on the objectives and specific research needs.

Illustrative Case Study : Descriptive in nature, these studies use one or two instances to depict a situation, helping to familiarize the unfamiliar and establish a common understanding of the topic.

Exploratory Case Study : Conducted as precursors to large-scale investigations, they assist in raising relevant questions, choosing measurement types, and identifying hypotheses to test.

Cumulative Case Study : These studies compile information from various sources over time to enhance generalization without the need for costly, repetitive new studies.

Critical Instance Case Study : Focused on specific sites, they either explore unique situations with limited generalizability or challenge broad assertions, to identify potential cause-and-effect issues.

Pros and Cons

As with any research study, case studies have a set of benefits and drawbacks.

- Provides comprehensive and detailed data.

- Offers a real-life perspective.

- Flexible and can adapt to discoveries during the study.

- Enables investigation of scenarios that are hard to assess in laboratory settings.

- Facilitates studying rare or unique cases.

- Generates hypotheses for future experimental research.

- Time-consuming and may require a lot of resources.

- Hard to generalize findings to a broader context.

- Potential for researcher bias.

- Cannot establish causality .

- Lacks scientific rigor compared to more controlled research methods .

Crafting a Good Case Study: Methodology

While case studies emphasize specific details over broad theories, they should connect to theoretical frameworks in the field. This approach ensures that these projects contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the subject, rather than standing as an isolated entity.

The following are critical steps in developing a case study:

- Define the Research Questions : Clearly outline what you want to explore. Define specific, achievable objectives.

- Select the Case : Choose a case that best suits the research questions. Consider using a typical case for general understanding or an atypical subject for unique insights.

- Data Collection : Use a variety of data sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and archival records, to provide multiple perspectives on the issue.

- Data Analysis : Identify patterns and themes in the data.

- Report Findings : Present the findings in a structured and clear manner.

Analysts typically use thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes within the data and compare different cases.

- Qualitative Analysis : Such as coding and thematic analysis for narrative data.

- Quantitative Analysis : In cases where numerical data is involved.

- Triangulation : Combining multiple methods or data sources to enhance accuracy.

A good case study requires a balanced approach, often using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

The researcher should constantly reflect on their biases and how they might influence the research. Documenting personal reflections can provide transparency.

Avoid over-generalization. One common mistake is to overstate the implications of a case study. Remember that these studies provide an in-depth insights into a specific case and might not be widely applicable.

Don’t ignore contradictory data. All data, even that which contradicts your hypothesis, is valuable. Ignoring it can lead to skewed results.

Finally, in the report, researchers provide comprehensive insight for a case study through “thick description,” which entails a detailed portrayal of the subject, its usage context, the attributes of involved individuals, and the community environment. Thick description extends to interpreting various data, including demographic details, cultural norms, societal values, prevailing attitudes, and underlying motivations. This approach ensures a nuanced and in-depth comprehension of the case in question.

Learn more about Qualitative Research and Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data .

Morland, J. & Feagin, Joe & Orum, Anthony & Sjoberg, Gideon. (1992). A Case for the Case Study . Social Forces. 71(1):240.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

Comments and questions cancel reply.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in the US |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race, and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 19 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The case study creation process

Types of case studies, benefits and limitations.

- Where was science invented?

- When did science begin?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Academia - Case Study

- Verywell Mind - What is a Case Study?

- Simply Psychology - Case Study Research Method in Psychology

- CORE - Case study as a research method

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - The case study approach

- BMC Journals - Evidence-Based Nursing - What is a case study?

- Table Of Contents

case study , detailed description and assessment of a specific situation in the real world created for the purpose of deriving generalizations and other insights from it. A case study can be about an individual, a group of people, an organization, or an event, among other subjects.

By focusing on a specific subject in its natural setting, a case study can help improve understanding of the broader features and processes at work. Case studies are a research method used in multiple fields, including business, criminology , education , medicine and other forms of health care, anthropology , political science , psychology , and social work . Data in case studies can be both qualitative and quantitative. Unlike experiments, where researchers control and manipulate situations, case studies are considered to be “naturalistic” because subjects are studied in their natural context . ( See also natural experiment .)

The creation of a case study typically involves the following steps:

- The research question to be studied is defined, informed by existing literature and previous research. Researchers should clearly define the scope of the case, and they should compile a list of evidence to be collected as well as identify the nature of insights that they expect to gain from the case study.

- Once the case is identified, the research team is given access to the individual, organization, or situation being studied. Individuals are informed of risks associated with participation and must provide their consent , which may involve signing confidentiality or anonymity agreements.

- Researchers then collect evidence using multiple methods, which may include qualitative techniques, such as interviews, focus groups , and direct observations, as well as quantitative methods, such as surveys, questionnaires, and data audits. The collection procedures need to be well defined to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the evidence.

- The collected evidence is analyzed to come up with insights. Each data source must be reviewed carefully by itself and in the larger context of the case study so as to ensure continued relevance. At the same time, care must be taken not to force the analysis to fit (potentially preconceived) conclusions. While the eventual case study may serve as the basis for generalizations, these generalizations must be made cautiously to ensure that specific nuances are not lost in the averages.

- Finally, the case study is packaged for larger groups and publication. At this stage some information may be withheld, as in business case studies, to allow readers to draw their own conclusions. In scientific fields, the completed case study needs to be a coherent whole, with all findings and statistical relationships clearly documented.

Case studies have been used as a research method across multiple fields. They are particularly popular in the fields of law, business, and employee training; they typically focus on a problem that an individual or organization is facing. The situation is presented in considerable detail, often with supporting data, to discussion participants, who are asked to make recommendations that will solve the stated problem. The business case study as a method of instruction was made popular in the 1920s by instructors at Harvard Business School who adapted an approach used at Harvard Law School in which real-world cases were used in classroom discussions. Other business and law schools started compiling case studies as teaching aids for students. In a business school case study, students are not provided with the complete list of facts pertaining to the topic and are thus forced to discuss and compare their perspectives with those of their peers to recommend solutions.

In criminology , case studies typically focus on the lives of an individual or a group of individuals. These studies can provide particularly valuable insight into the personalities and motives of individual criminals, but they may suffer from a lack of objectivity on the part of the researchers (typically because of the researchers’ biases when working with people with a criminal history), and their findings may be difficult to generalize.

In sociology , the case-study method was developed by Frédéric Le Play in France during the 19th century. This approach involves a field worker staying with a family for a period of time, gathering data on the family members’ attitudes and interactions and on their income, expenditures, and physical possessions. Similar approaches have been used in anthropology . Such studies can sometimes continue for many years.

Case studies provide insight into situations that involve a specific entity or set of circumstances. They can be beneficial in helping to explain the causal relationships between quantitative indicators in a field of study, such as what drives a company’s market share. By introducing real-world examples, they also plunge the reader into an actual, concrete situation and make the concepts real rather than theoretical. They also help people study rare situations that they might not otherwise experience.

Because case studies are in a “naturalistic” environment , they are limited in terms of research design: researchers lack control over what they are studying, which means that the results often cannot be reproduced. Also, care must be taken to stay within the bounds of the research question on which the case study is focusing. Other limitations to case studies revolve around the data collected. It may be difficult, for instance, for researchers to organize the large volume of data that can emerge from the study, and their analysis of the data must be carefully thought through to produce scientifically valid insights. The research methodology used to generate these insights is as important as the insights themselves, for the latter need to be seen in the proper context. Taken out of context, they may lead to erroneous conclusions. Like all scientific studies, case studies need to be approached objectively; personal bias or opinion may skew the research methods as well as the results. ( See also confirmation bias .)

Business case studies in particular have been criticized for approaching a problem or situation from a narrow perspective. Students are expected to come up with solutions for a problem based on the data provided. However, in real life, the situation is typically reversed: business managers face a problem and must then look for data to help them solve it.

- User Experience (UX) Testing User Interface (UI) Testing Ecommerce Testing Remote Usability Testing About the company ' data-html="true"> Why Trymata

- Usability testing

Run remote usability tests on any digital product to deep dive into your key user flows

- Product analytics

Learn how users are behaving on your website in real time and uncover points of frustration

- Research repository

A tool for collaborative analysis of qualitative data and for building your research repository and database.

See an example

Trymata Blog

How-to articles, expert tips, and the latest news in user testing & user experience

Knowledge Hub

Detailed explainers of Trymata’s features & plans, and UX research terms & topics

Visit Knowledge Hub

- Plans & Pricing

Get paid to test

- For UX & design teams

- For product teams

- For marketing teams

- For ecommerce teams

- For agencies

- For startups & VCs

- Customer Stories

How do you want to use Trymata?

Conduct user testing, desktop usability video.

You’re on a business trip in Oakland, CA. You've been working late in downtown and now you're looking for a place nearby to grab a late dinner. You decided to check Zomato to try and find somewhere to eat. (Don't begin searching yet).

- Look around on the home page. Does anything seem interesting to you?

- How would you go about finding a place to eat near you in Downtown Oakland? You want something kind of quick, open late, not too expensive, and with a good rating.

- What do the reviews say about the restaurant you've chosen?

- What was the most important factor for you in choosing this spot?

- You're currently close to the 19th St Bart station, and it's 9PM. How would you get to this restaurant? Do you think you'll be able to make it before closing time?

- Your friend recommended you to check out a place called Belly while you're in Oakland. Try to find where it is, when it's open, and what kind of food options they have.

- Now go to any restaurant's page and try to leave a review (don't actually submit it).

What was the worst thing about your experience?

It was hard to find the bart station. The collections not being able to be sorted was a bit of a bummer

What other aspects of the experience could be improved?

Feedback from the owners would be nice

What did you like about the website?

The flow was good, lots of bright photos

What other comments do you have for the owner of the website?

I like that you can sort by what you are looking for and i like the idea of collections

You're going on a vacation to Italy next month, and you want to learn some basic Italian for getting around while there. You decided to try Duolingo.

- Please begin by downloading the app to your device.

- Choose Italian and get started with the first lesson (stop once you reach the first question).

- Now go all the way through the rest of the first lesson, describing your thoughts as you go.

- Get your profile set up, then view your account page. What information and options are there? Do you feel that these are useful? Why or why not?

- After a week in Italy, you're going to spend a few days in Austria. How would you take German lessons on Duolingo?

- What other languages does the app offer? Do any of them interest you?

I felt like there could have been a little more of an instructional component to the lesson.

It would be cool if there were some feature that could allow two learners studying the same language to take lessons together. I imagine that their screens would be synced and they could go through lessons together and chat along the way.

Overall, the app was very intuitive to use and visually appealing. I also liked the option to connect with others.

Overall, the app seemed very helpful and easy to use. I feel like it makes learning a new language fun and almost like a game. It would be nice, however, if it contained more of an instructional portion.

All accounts, tests, and data have been migrated to our new & improved system!

Use the same email and password to log in:

Legacy login: Our legacy system is still available in view-only mode, login here >

What’s the new system about? Read more about our transition & what it-->

What is a Case Study? Definition, Research Methods, Sampling and Examples

What is a Case Study?

A case study is defined as an in-depth analysis of a particular subject, often a real-world situation, individual, group, or organization.

It is a research method that involves the comprehensive examination of a specific instance to gain a better understanding of its complexities, dynamics, and context.

Case studies are commonly used in various fields such as business, psychology, medicine, and education to explore and illustrate phenomena, theories, or practical applications.

In a typical case study, researchers collect and analyze a rich array of qualitative and/or quantitative data, including interviews, observations, documents, and other relevant sources. The goal is to provide a nuanced and holistic perspective on the subject under investigation.

The information gathered here is used to generate insights, draw conclusions, and often to inform broader theories or practices within the respective field.

Case studies offer a valuable method for researchers to explore real-world phenomena in their natural settings, providing an opportunity to delve deeply into the intricacies of a particular case. They are particularly useful when studying complex, multifaceted situations where various factors interact.

Additionally, case studies can be instrumental in generating hypotheses, testing theories, and offering practical insights that can be applied to similar situations. Overall, the comprehensive nature of case studies makes them a powerful tool for gaining a thorough understanding of specific instances within the broader context of academic and professional inquiry.

Key Characteristics of Case Study

Case studies are characterized by several key features that distinguish them from other research methods. Here are some essential characteristics of case studies:

- In-depth Exploration: Case studies involve a thorough and detailed examination of a specific case or instance. Researchers aim to explore the complexities and nuances of the subject under investigation, often using multiple data sources and methods to gather comprehensive information.

- Contextual Analysis: Case studies emphasize the importance of understanding the context in which the case unfolds. Researchers seek to examine the unique circumstances, background, and environmental factors that contribute to the dynamics of the case. Contextual analysis is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions and generalizing findings to similar situations.

- Holistic Perspective: Rather than focusing on isolated variables, case studies take a holistic approach to studying a phenomenon. Researchers consider a wide range of factors and their interrelationships, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of the case. This holistic perspective helps in providing a more complete understanding of the subject.

- Qualitative and/or Quantitative Data: Case studies can incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data, depending on the research question and objectives. Qualitative data often include interviews, observations, and document analysis, while quantitative data may involve statistical measures or numerical information. The combination of these data types enhances the depth and validity of the study.

- Longitudinal or Retrospective Design: Case studies can be designed as longitudinal studies, where the researcher follows the case over an extended period, or retrospective studies, where the focus is on examining past events. This temporal dimension allows researchers to capture changes and developments within the case.

- Unique and Unpredictable Nature: Each case study is unique, and the findings may not be easily generalized to other situations. The unpredictable nature of real-world cases adds a layer of authenticity to the study, making it an effective method for exploring complex and dynamic phenomena.

- Theory Building or Testing: Case studies can serve different purposes, including theory building or theory testing. In some cases, researchers use case studies to develop new theories or refine existing ones. In others, they may test existing theories by applying them to real-world situations and assessing their explanatory power.

Understanding these key characteristics is essential for researchers and practitioners using case studies as a methodological approach, as it helps guide the design, implementation, and analysis of the study.

Key Components of a Case Study

A well-constructed case study typically consists of several key components that collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation. Here are the key components of a case study:

- Provide an overview of the context and background information relevant to the case. This may include the history, industry, or setting in which the case is situated.

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define what the study aims to achieve and the questions it seeks to answer.

- Clearly identify the subject of the case study. This could be an individual, a group, an organization, or a specific event.

- Define the boundaries and scope of the case study. Specify what aspects will be included and excluded from the investigation.

- Provide a brief review of relevant theories or concepts that will guide the analysis. This helps place the case study within the broader theoretical context.

- Summarize existing literature related to the subject, highlighting key findings and gaps in knowledge. This establishes the context for the current case study.

- Describe the research design chosen for the case study (e.g., exploratory, explanatory, descriptive). Justify why this design is appropriate for the research objectives.

- Specify the methods used to gather data, whether through interviews, observations, document analysis, surveys, or a combination of these. Detail the procedures followed to ensure data validity and reliability.

- Explain the criteria for selecting the case and any sampling considerations. Discuss why the chosen case is representative or relevant to the research questions.

- Describe how the collected data will be coded and categorized. Discuss the analytical framework or approach used to identify patterns, themes, or trends.

- If multiple data sources or methods are used, explain how they complement each other to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings.

- Present the key findings in a clear and organized manner. Use tables, charts, or quotes from participants to illustrate the results.

- Interpret the results in the context of the research objectives and theoretical framework. Discuss any unexpected findings and their implications.

- Provide a thorough interpretation of the results, connecting them to the research questions and relevant literature.

- Acknowledge the limitations of the study, such as constraints in data collection, sample size, or generalizability.

- Highlight the contributions of the case study to the existing body of knowledge and identify potential avenues for future research.

- Summarize the key findings and their significance in relation to the research objectives.

- Conclude with a concise summary of the case study, its implications, and potential practical applications.

- Provide a complete list of all the sources cited in the case study, following a consistent citation style.

- Include any additional materials or supplementary information, such as interview transcripts, survey instruments, or supporting documents.

By including these key components, a case study becomes a comprehensive and well-rounded exploration of a specific subject, offering valuable insights and contributing to the body of knowledge in the respective field.

Sampling in a Case Study Research

Sampling in case study research involves selecting a subset of cases or individuals from a larger population to study in depth. Unlike quantitative research where random sampling is often employed, case study sampling is typically purposeful and driven by the specific objectives of the study. Here are some key considerations for sampling in case study research:

- Criterion Sampling: Cases are selected based on specific criteria relevant to the research questions. For example, if studying successful business strategies, cases may be selected based on their demonstrated success.

- Maximum Variation Sampling: Cases are chosen to represent a broad range of variations related to key characteristics. This approach helps capture diversity within the sample.

- Selecting Cases with Rich Information: Researchers aim to choose cases that are information-rich and provide insights into the phenomenon under investigation. These cases should offer a depth of detail and variation relevant to the research objectives.

- Single Case vs. Multiple Cases: Decide whether the study will focus on a single case (single-case study) or multiple cases (multiple-case study). The choice depends on the research objectives, the complexity of the phenomenon, and the depth of understanding required.

- Emergent Nature of Sampling: In some case studies, the sampling strategy may evolve as the study progresses. This is known as theoretical sampling, where new cases are selected based on emerging findings and theoretical insights from earlier analysis.

- Data Saturation: Sampling may continue until data saturation is achieved, meaning that collecting additional cases or data does not yield new insights or information. Saturation indicates that the researcher has adequately explored the phenomenon.

- Defining Case Boundaries: Clearly define the boundaries of the case to ensure consistency and avoid ambiguity. Consider what is included and excluded from the case study, and justify these decisions.

- Practical Considerations: Assess the feasibility of accessing the selected cases. Consider factors such as availability, willingness to participate, and the practicality of data collection methods.

- Informed Consent: Obtain informed consent from participants, ensuring that they understand the purpose of the study and the ways in which their information will be used. Protect the confidentiality and anonymity of participants as needed.

- Pilot Testing the Sampling Strategy: Before conducting the full study, consider pilot testing the sampling strategy to identify potential challenges and refine the approach. This can help ensure the effectiveness of the sampling method.

- Transparent Reporting: Clearly document the sampling process in the research methodology section. Provide a rationale for the chosen sampling strategy and discuss any adjustments made during the study.

Sampling in case study research is a critical step that influences the depth and richness of the study’s findings. By carefully selecting cases based on specific criteria and considering the unique characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation, researchers can enhance the relevance and validity of their case study.

Case Study Research Methods With Examples

- Interviews:

- Interviews involve engaging with participants to gather detailed information, opinions, and insights. In a case study, interviews are often semi-structured, allowing flexibility in questioning.

- Example: A case study on workplace culture might involve conducting interviews with employees at different levels to understand their perceptions, experiences, and attitudes.

- Observations:

- Observations entail direct examination and recording of behavior, activities, or events in their natural setting. This method is valuable for understanding behaviors in context.

- Example: A case study investigating customer interactions at a retail store may involve observing and documenting customer behavior, staff interactions, and overall dynamics.

- Document Analysis:

- Document analysis involves reviewing and interpreting written or recorded materials, such as reports, memos, emails, and other relevant documents.

- Example: In a case study on organizational change, researchers may analyze internal documents, such as communication memos or strategic plans, to trace the evolution of the change process.

- Surveys and Questionnaires:

- Surveys and questionnaires collect structured data from a sample of participants. While less common in case studies, they can be used to supplement other methods.

- Example: A case study on the impact of a health intervention might include a survey to gather quantitative data on participants’ health outcomes.

- Focus Groups:

- Focus groups involve a facilitated discussion among a group of participants to explore their perceptions, attitudes, and experiences.

- Example: In a case study on community development, a focus group might be conducted with residents to discuss their views on recent initiatives and their impact.

- Archival Research:

- Archival research involves examining existing records, historical documents, or artifacts to gain insights into a particular phenomenon.

- Example: A case study on the history of a landmark building may involve archival research, exploring construction records, historical photos, and maintenance logs.

- Longitudinal Studies:

- Longitudinal studies involve the collection of data over an extended period to observe changes and developments.

- Example: A case study tracking the career progression of employees in a company may involve longitudinal interviews and document analysis over several years.

- Cross-Case Analysis:

- Cross-case analysis compares and contrasts multiple cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences.

- Example: A comparative case study of different educational institutions may involve analyzing common challenges and successful strategies across various cases.

- Ethnography:

- Ethnography involves immersive, in-depth exploration within a cultural or social setting to understand the behaviors and perspectives of participants.

- Example: A case study using ethnographic methods might involve spending an extended period within a community to understand its social dynamics and cultural practices.

- Experimental Designs (Rare):

- While less common, experimental designs involve manipulating variables to observe their effects. In case studies, this might be applied in specific contexts.

- Example: A case study exploring the impact of a new teaching method might involve implementing the method in one classroom while comparing it to a traditional method in another.

These case study research methods offer a versatile toolkit for researchers to investigate and gain insights into complex phenomena across various disciplines. The choice of methods depends on the research questions, the nature of the case, and the desired depth of understanding.

Best Practices for a Case Study in 2024

Creating a high-quality case study involves adhering to best practices that ensure rigor, relevance, and credibility. Here are some key best practices for conducting and presenting a case study:

- Clearly articulate the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define the research questions or problems you aim to address, ensuring a focused and purposeful approach.

- Choose a case that aligns with the research objectives and provides the depth and richness needed for the study. Consider the uniqueness of the case and its relevance to the research questions.

- Develop a robust research design that aligns with the nature of the case study (single-case or multiple-case) and integrates appropriate research methods. Ensure the chosen design is suitable for exploring the complexities of the phenomenon.

- Use a variety of data sources to enhance the validity and reliability of the study. Combine methods such as interviews, observations, document analysis, and surveys to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Clearly document and describe the procedures for data collection to enhance transparency. Include details on participant selection, sampling strategy, and data collection methods to facilitate replication and evaluation.

- Implement measures to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. Triangulate information from different sources to cross-verify findings and strengthen the credibility of the study.

- Clearly define the boundaries of the case to avoid scope creep and maintain focus. Specify what is included and excluded from the study, providing a clear framework for analysis.

- Include perspectives from various stakeholders within the case to capture a holistic view. This might involve interviewing individuals at different organizational levels, customers, or community members, depending on the context.

- Adhere to ethical principles in research, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality, and addressing any potential conflicts of interest.

- Conduct a rigorous analysis of the data, using appropriate analytical techniques. Interpret the findings in the context of the research questions, theoretical framework, and relevant literature.

- Offer detailed and rich descriptions of the case, including the context, key events, and participant perspectives. This helps readers understand the intricacies of the case and supports the generalization of findings.

- Communicate findings in a clear and accessible manner. Avoid jargon and technical language that may hinder understanding. Use visuals, such as charts or graphs, to enhance clarity.

- Seek feedback from colleagues or experts in the field through peer review. This helps ensure the rigor and credibility of the case study and provides valuable insights for improvement.

- Connect the case study findings to existing theories or concepts, contributing to the theoretical understanding of the phenomenon. Discuss practical implications and potential applications in relevant contexts.

- Recognize that case study research is often an iterative process. Be open to revisiting and refining research questions, methods, or analysis as the study progresses. Practice reflexivity by acknowledging and addressing potential biases or preconceptions.

By incorporating these best practices, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their case studies, making valuable contributions to the academic and practical understanding of complex phenomena.

Interested in learning more about the fields of product, research, and design? Search our articles here for helpful information spanning a wide range of topics!

A Guide to the System Usability Scale (SUS) and Its Scores

What is usability metrics, types best practices & more, jobs to be done (jtbd): definition, framework & applications, time on task: a key metric for enhancing productivity and ux.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons