ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Work-life balance, job satisfaction, and job performance of smes employees: the moderating role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors.

- 1 Department of Management, Universitas Negeri Padang, Padang, Indonesia

- 2 BRAC Business School, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 3 Faculty of Economics and Management, National University of Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia

Even though studies on work-life balance and family-supportive supervisor behaviors are prevalent, there are few studies in the SME setting, and the implications are yet unexplained. Thus, the study examines the effect of work-life balance on the performance of employees in SMEs, along with the mediating role of job satisfaction and the moderating role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors. We have developed a conceptually mediated-moderated model for the nexus of work-life balance and job performance. We collected data from SMEs and employed SEM-PLS to test the research hypothesis and model. Empirical results demonstrate that work-life balance positively influences job satisfaction and performance. Our empirical findings also revealed that job satisfaction partially mediates the relationship between work-life balance and job performance. We also found that when FSSB interacts with work-life balance and job satisfaction, it moderates the relationship between work-life balance and job performance and job satisfaction and job performance. Hence, our findings provide exciting and valuable insights for research and practice.

Introduction

The importance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the global and national economies is worth mentioning, considering their role in creating employment and contributing to GDP. According to a World Bank (2020) survey on SMEs, the sector accounts for 90% of businesses and 50% of jobs globally. According to the report, this sector contributes more than 40% of GDP and creates 70% employment in developing economies. The SME sector is rapidly expanding in Indonesia, and around 63 million SMEs operate ( Surya et al., 2021 ). Of those, 62 million are classified as medium-sized firms, and 0.75 million are classified as small businesses. SMEs are divided into four categories: household businesses with 1–5 workers; small and medium businesses with 6–19 workers; medium-sized companies with 20–29 workers; and large companies with more than 100 workers ( Badan Pusat Statistik, 2020 ). More importantly, the sector contributes 61.07% of the country’s total GDP and provides 97% of the entire employment ( ILO, 2019 ; Kementerian Koperasi dan UKM Republik Indonesia, 2019 ; Pramono et al., 2021 ).

Given the importance of SMEs in the economy, it is necessary to maintain and sustain the sector’s human resource performance. A strand of the literature highlighted that firm-specific factors and the environment impact employee performance. Another strand of the literature highlighted that the performance of an employee could be influenced by cognitive factors, such as individual quality ( Luthans et al., 2007 ), supervisor support, work-life balance ( Talukder et al., 2018 ), cognitive abilities, personality ( Kanfer and Kantrowitz, 2005 ), leadership, and family supportive supervisor behaviors ( Walumbwa et al., 2010 ; Wang et al., 2013 ; Kim et al., 2015 ). Although all these factors are important determinants, the current study argues that work-life balance and family supportive supervisor behavior are more important than employees’ involvement in every possible business activity of SMEs.

In the SME world, the working hours are different from those in larger firms. SMEs demand longer hours from employees. Therefore, it is difficult for employees to balance work and personal life. Some of the time, they also failed to maintain social and personal life due to high engagement and stress at work. The entanglements between work and family are a significant source of psychological discomfort for employees ( Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012 ; Lamane-Harim et al., 2021 ). This could lead to job dissatisfaction and poor job performance. Hence, the employee turnover and the intention to quit. On the other hand, Haar et al. (2014) stated that WLB has a positive impact on one’s achievements, including performances. Similarly, increased job satisfaction impacts performance ( Luthans et al., 2007 ; Walumbwa et al., 2010 ). Positive job satisfaction will increase employee capacity, which, if appropriately managed, will have a good impact on the employee’s job performance ( Luthans et al., 2007 ).

However, in the competitive market, being a small team, the SMEs may not be able to afford to lose their skilled and knowledgeable employees as they are involved in product innovation and product sales. In order to facilitate work-life balance, SMEs indeed need to deploy the WLB’s supportive culture. Lamane-Harim et al. (2021) suggest that practices or the introduction of WLBSC could influence job satisfaction and organizational commitment. These factors ultimately determine employee performance in SMEs and their sustainability (e.g., Cuéllar-Molina et al., 2018 ). In the practices of WLBSC, family-supportive supervisor behaviors could play an important role, as family-supportive supervisor behaviors are expected to influence outcomes related to one’s performance ( Wang et al., 2013 ). In previous studies, supportive family supervisor behaviors were associated with job satisfaction and job performance ( Greenhaus et al., 2012 ; Wang et al., 2013 ; Heras et al., 2021 ). Past studies also suggest the mediating role of work-life balance supportive culture in SMEs. However, since the work-life balance supportive culture is a contextual factor and a new introduction into the working environment, it is expected to increase or decrease the extent of the relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job satisfaction and the relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job performance. It also raises the question of how moderation affects the existing relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job satisfaction and the relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job performance. However, past studies have not investigated the moderating role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors (e.g., Greenhaus et al., 2012 ; Wang et al., 2013 ; Heras et al., 2021 ; Lamane-Harim et al., 2021 ).

Past studies on work-life balance have primarily focused on large firms. Several other studies have recommended more studies of this topic in SMEs ( Lavoie, 2004 ; Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012 ). Recently, Lamane-Harim et al. (2021) have researched work-life balance and WLBSC on Spanish SMEs. Furthermore, most research analyzing the relationships between WLBSC and employee outcome has been conducted in the United States. Moreover, national culture can also affect the intensity of the link between WLB practices and their effects on employee outcomes ( Spector et al., 2007 ; Poelmans et al., 2005 ; Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012 ; Lucia-Casademunt et al., 2015 ; Ollier-Malaterre and Foucreault, 2017 ; Putnik et al., 2020 ; Kelley et al., 2021 ). Thus, the current study fills the research gap by examining the moderating role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors on the relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job satisfaction and the relationship between work-life balance (WLB) and job performance. To fulfill these objectives, a review of the literature is carried out. The research hypotheses are developed, which are examined in an empirical study with a sample of employees of Indonesian SMEs in an industrial sector. The implications arising from the investigation are given in the final part. Henceforth, the current study will be beneficial to the SME sector in Indonesia alongside the literature.

Literature Review

Social exchange theory.

According to the Social Exchange Theory (SET) ( Blau, 1964 ), social exchange relationships rest on the norm of reciprocity ( Gouldner, 1960 ). The theory argues that when one party provides a benefit to another, the recipient tends to reciprocate the favor by offering benefits and favorable treatment to the first party ( Coyle-Shapiro and Shore, 2007 ). In an organizational behavior context, the social exchange theory is frequently used to explain the formation and maintenance of interpersonal relationships between employees and employers regarding reciprocation procedures ( Chen et al., 2005 ; Rawshdeh et al., 2019 ). The theory explains why employees choose to be less or more engaged in their jobs ( Lee and Veasna, 2013 ) and how the organizational support system influences subordinates’ creativity ( Amabile et al., 2004 ) and other positive behavior.

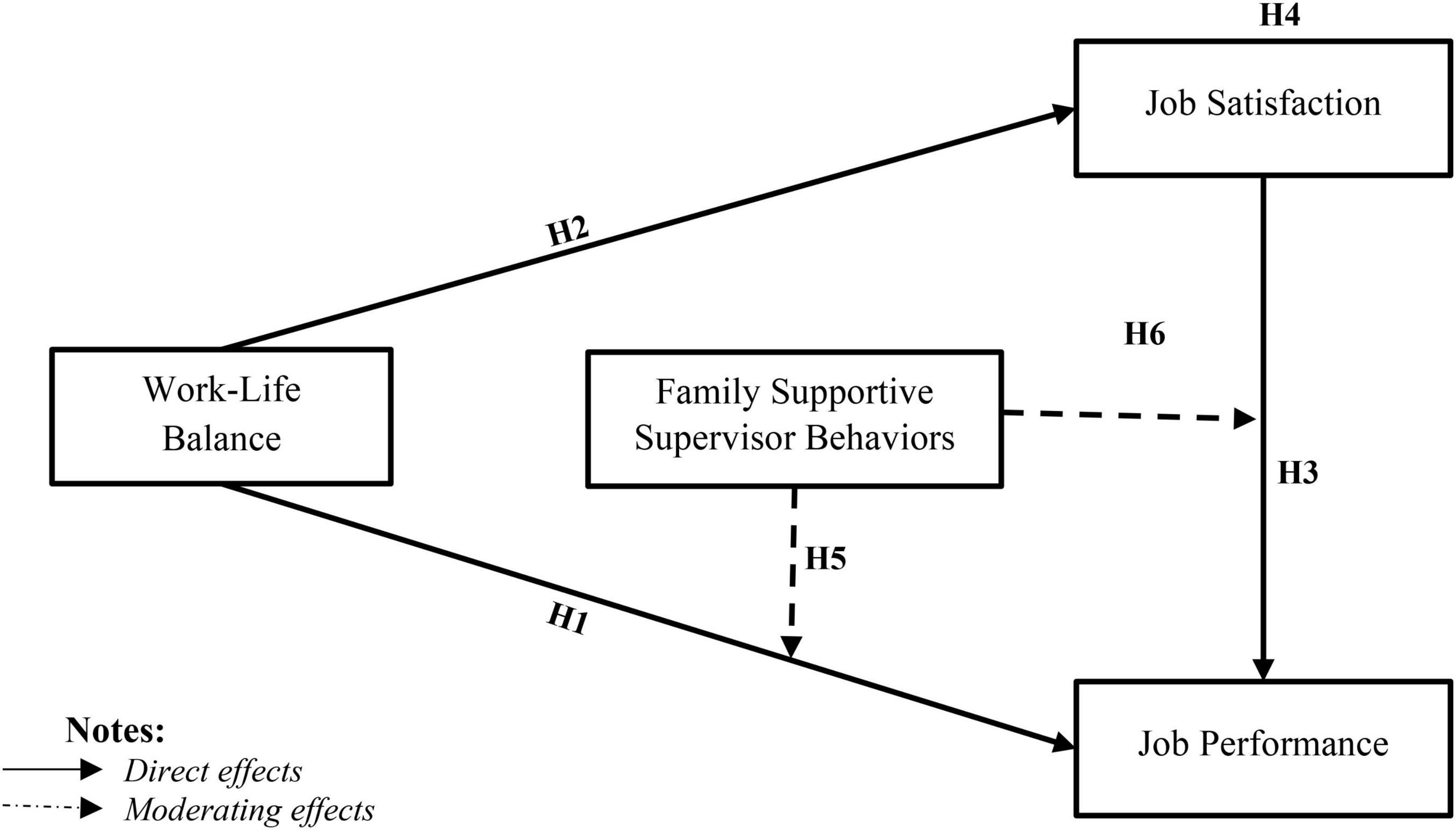

Past studies have argued that when management provides benefits to employees, employees tend to feel indebted to the organization and make more substantial efforts to ensure its well-being and achieve its goal ( Eisenberger et al., 2001 ; Vayre, 2019 ). Several studies found evidence in the work-life balance literature that when organizations or supervisors care about their employees’ personal and professional well-being, employees tend to reciprocate by helping them achieve their goals through improved performance ( Campo et al., 2021 ). Therefore, based on the social exchange theory, this study argues that when organizations take care of the balance between employees’ personal and professional lives, employees’ perceived positive feelings increase their job satisfaction, and they are more inclined to reciprocate the favor through high job performance ( Talukder et al., 2018 ). In such circumstances, the supervisor’s formal and informal support further increases employees’ perceived positive feelings toward the job and strengthens the relationship between work-life balance, job satisfaction, and job performance. We present a conceptual model in Figure 1 , which illustrates the expected causal relationship among study variables.

Figure 1. Conceptual research model.

Job Performance

Employee job performance refers to an employee’s expertise in carrying out their duties in a way that helps the organization achieve its goals ( Luthans et al., 2007 , 2008 ; Nohe et al., 2014 ; Moonsri, 2018 ). It is also defined as an individual’s productivity compared to their coworkers on a variety of job-related behaviors and results ( Babin and Boles, 1998 ; Aeknarajindawat and Jermsittiparsert, 2020 ). Performance is determined by the quality and quantity of work completed as part of an employee’s assigned responsibilities. Employee performance directly influences an organization’s financial and non-financial outcomes ( Anitha, 2014 ). Thus, organizations need high-performing employees to achieve their corporate goals, vision, and mission and gain a competitive advantage ( Thevanes and Mangaleswaran, 2018 ).

A business must have a persistent competitive advantage in the SME context with many competitors to compete with other companies in the same industry. While job stress has been shown to have a significant negative impact on employee performance, work overload, lack of work-life balance, management style, and job insecurity are some of the factors that contribute to increased job stress ( Naqvi et al., 2013 ). Since SMEs need employees to work longer hours, it is possible that SMEs’ employees lack a healthy balance between work and family life, thereby impacting their job performance. Organizations are increasingly focusing on implementing a variety of HR practices and strategies, including work-life balance, on increasing employee job performance, as work-life balance is seen as one of the most important factors influencing job performance ( Thevanes and Mangaleswaran, 2018 ). Previous research found ample evidence that work-life balance is essential to increasing employee job performance ( Preena, 2021 ). Therefore, the role of work-life in influencing SME employees’ job performance should be determined to ensure the industry’s survival.

Work-Life Balance, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance

Work-life balance refers to balancing one’s professional work, family responsibilities, and other personal activities ( Keelan, 2015 ; Kerdpitak and Jermsittiparsert, 2020 ). It refers to an employee’s sense of a balance between work and personal life ( Haar et al., 2014 ). It represents how people fulfill or should fulfill their business and personal obligations so that an overlapping situation is avoided ( Konrad and Mangel, 2000 ). The changing work patterns and the pressing demand for domestic chores have had an adverse impact on people’s work, social, and family lives ( Barling and Macewen, 1992 ). Therefore, researchers suggested that the human resource management of an organization should develop effective policies such as adequate mentoring, support, flexible working hours, reducing workload, and many others that can reduce employees’ work-life conflict ( Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012 ) and positively influence their satisfaction ( Allen et al., 2020 ) and performance ( Hughes and Bozionelos, 2007 ).

Work-life balance is one of the most important issues that human resource management should address in organizations ( Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). Regardless of their size, organizations should ensure that employees have adequate time to fulfill their family and work commitments ( Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). A flexible working environment allows employees to balance personal and professional responsibilities ( Redmond et al., 2006 ). Organizations that ignore the issue of work-life balance suffer from reduced productivity and employee performance ( Naithani, 2010 ). Indeed, employees with a healthy work-life balance are generally grateful to their employers ( Roberts, 2008 ). As a result, they put forth their best effort for the company as a gesture of gratitude, resulting in improved job performance ( Ryan and Kossek, 2008 ). Thus, a high work-life balance employee could be highly productive and an excellent performer ( French et al., 2020 ). Thus, based on these discussions and research findings, we developed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Work-life balance has a positive effect on job performance.

Previous researchers have argued that satisfaction and success in family life can lead to success and satisfaction at work Victoria et al. (2019) . Employees who are pleased with their personal and professional achievements are more likely to achieve the organizational goal ( Dousin et al., 2019 ). While the work-life conflict has been shown to have a negative impact on employee job performance and satisfaction ( Dousin et al., 2019 ), work-life balance has been found to improve employee satisfaction and job performance in various industries and countries ( Mendis and Weerakkody, 2017 ; Thevanes and Mangaleswaran, 2018 ; Victoria et al., 2019 ; Obrenovic et al., 2020 ; Rini et al., 2020 ; Preena, 2021 ). It is documented that medical doctors’ job satisfaction and performance are influenced by their perceptions of flexible working hours and supportive supervision ( Dousin et al., 2019 ). Besides, there is ample empirical evidence that job satisfaction can positively influence employee job performance ( Krishnan et al., 2018 ; Zhao et al., 2019 ; Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). Based on the above research findings, the following hypotheses have been developed:

Hypothesis 2: Work-life balance has a positive effect on job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: Job satisfaction has a positive influence on job performance

Job satisfaction refers to the positive attitude felt by an employee toward the company where they work ( Luthans et al., 2007 ; Tschopp et al., 2014 ). It combines cognitive and affective responses to the disparity between what an employee wants and what they get ( Cranny et al., 1992 ). Previous research has often linked a person’s job satisfaction with their behavior at work ( Crede et al., 2007 ). It is argued that employees would be more committed to their jobs if they found them satisfying and enjoyable ( Noah and Steve, 2012 ). Employee job satisfaction is influenced by an organization’s commitment to work-life balance, and satisfied employees are more likely to invest their time and effort in the development of the organization ( Dousin et al., 2019 ) in exchange for the support they received ( Krishnan et al., 2018 ; Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). Previous research found that employee work-life balance increases employee job performance by positively influencing psychological well-being ( Haider et al., 2017 ). Dousin et al. (2019) found that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between employee work-life balance and job performance in a medical context. Since work-life balance has been seen as an influencer of job satisfaction ( Victoria et al., 2019 ) and job satisfaction influences employee job performance ( Dormann and Zapf, 2001 ; Saari and Judge, 2004 ; Crede et al., 2007 ; Luthans et al., 2007 ; Tschopp et al., 2014 ; Krishnan et al., 2018 ; Zhao et al., 2019 ; Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). Thus, based on the above research findings, this study offers the following hypothesis:

H4: Job satisfaction significantly mediates the relationship between work-life balance and job performance.

Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors

Hammer et al. (2009) define family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) as the emotional, instrumental, role-modeling, and creative work-family management supportive behaviors that the supervisors provide to ensure employee effectiveness and satisfaction on and off the job. It refers to an employee’s perception of their supervisor’s positive attitude toward them ( Clark et al., 2017 ). Supervisory support could be formal or informal ( Achour et al., 2020 ). It is critical in developing flexible work arrangements ( Suriana et al., 2021 ).

Supervisory supportive behavior is very important for ensuring work-life balance and achieving organizational goals. It has been shown to reduce work-family spillover ( García-Cabrera et al., 2018 ) by increasing employee job satisfaction autonomy and reducing work pressure ( Marescaux et al., 2020 ). The flexibility and independence generated by FSSB help to reduce work-family conflict ( Greenhaus et al., 2012 ) by increasing employees’ control over their work ( Marescaux et al., 2020 ) and allowing them to strike a balance between their work and family life ( Heras et al., 2021 ). Employees who believe their managers care about their personal and professional lives are more likely to improve their performance and meet supervisory objectives ( Rofcanin et al., 2018 ). In a university-based study, Achour et al. (2020) showed how supervisory support positively moderates the relationship between a female academic’s work-family demands and perceived well-being. Kim et al. (2017) show that supervisory support can strengthen the relationship between deep acting and job performance, exacerbating the negative relationship between surface acting and job performance. Therefore, this study argues that, in an organization, when work-life balance is valued, supervisory support might influence employees’ positive perception, and the effect of work-life balance strategies and job satisfaction on job performance will be greater.

Hypothesis 5: Family-supportive supervisor behaviors will strengthen the positive effect of work-life balance on job performance.

Hypothesis 6: Family-supportive supervisor behaviors will strengthen the positive effect of job satisfaction on job performance.

Methods and Results

The current study has adopted a quantitative approach to determine the causal relationship of a phenomenon or problem-solving understudy to see how far the influence of exogenous variables extends to endogenous variables. The current study has also developed and distributed structured questionnaires to around 600 employees who work in SMEs in Indonesia.

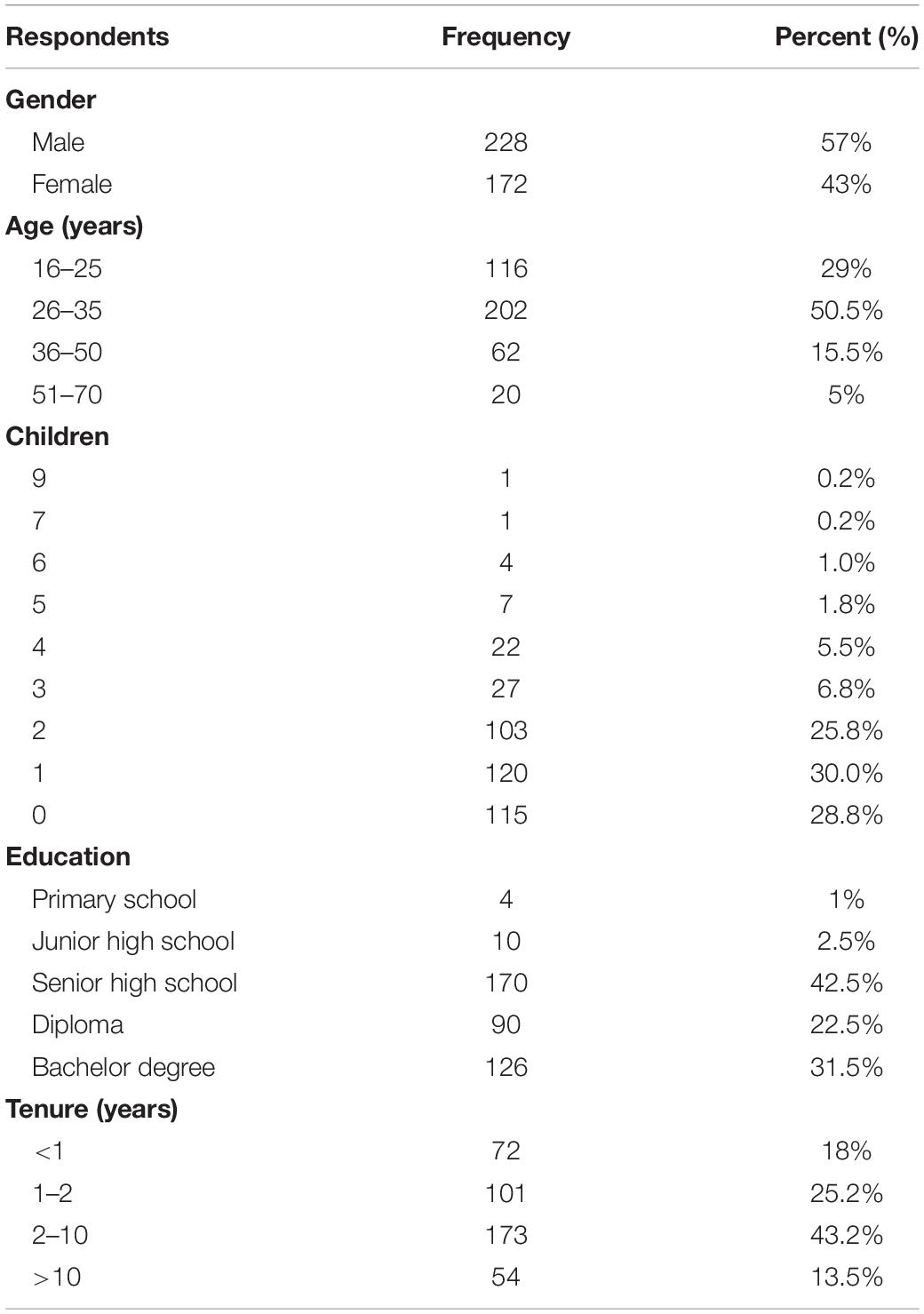

To obtain and collect data, the study employed a non-probability method, namely purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is limited to certain types of people who can provide the desired information, maybe because they are the only ones who have it, or perhaps they fit the criteria set by the researcher ( Sekaran and Bougie, 2017 ). The selected sample is employees who work in SMEs that already have an employee recruitment system, have supervisors, and are married. The sample size was taken as many as 400 samples with consideration of the adequacy of the sample statistically to get a power of 0.8 with an alpha of 0.05. The sample was repeated at least five times until 20 items were observed ( Hair et al., 2015 ). The demographic profile of the respondents is presented in Table 1 . The majority of the respondents were male (57%), aged 26–35 (50.5%), had one child (30%), were senior high school graduates (42.5%), and had 2 to 10 years of experience (43.2%). Furthermore, measurements and variables are presented in Table 2 . The construct measurement items are reflective in nature.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

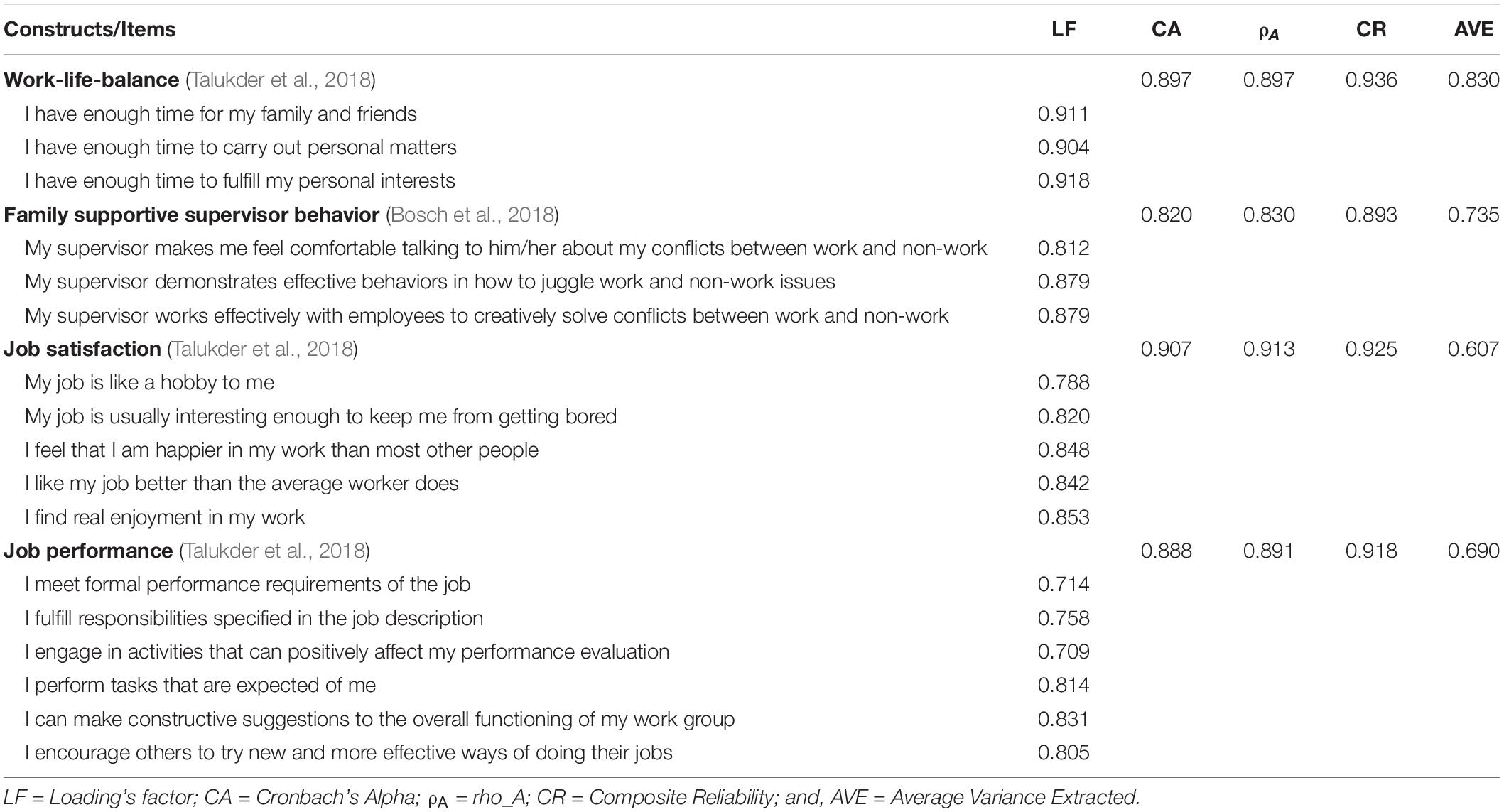

Table 2. Summary for convergent validity and internal consistency reliability.

Empirical Estimations and Results

We employ the Partial Least Square (PLS) method to test hypotheses, considering variables’ direct, indirect, and total effects. PLS was chosen because the method of solving structural equation modeling (SEM) with PLS, which in this case fits the research objectives, is more appropriate than other SEM techniques. PLS is an analytical method that is not based on many assumptions ( Hair et al., 2015 ). Finally, we employ PLS-SEM because of its applicability and effectiveness in both exploratory and confirmatory research and prediction ( Chin and Dibbern, 2010 ; Ringle et al., 2012 ). To cope with missing values, we consider the mean replacement strategy ( Wesarat et al., 2018 ). The parameters of the measurement and structural models are computed in accordance with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2014) . Hypothesis testing is done by looking at the p -value generated by the inner model. This test is carried out by operating bootstrapping on the SmartPLS 3.0 program to obtain the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables.

Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement model has been evaluated in this study based on internal consistency, construct validity, and instrument reliability. The composite reliability can be used to assess the reliability of a variable’s indicators. With its indicators, there is a latent loading factor value. The loading factor is the path coefficient that connects the latent variable to the indicator. If an indicator has a composite reliability value greater than 0.6, it can fulfill reliability requirements. Cronbach’s alpha needs to be taken into account in the reliability test using the composite reliability approach. If a value has a Cronbach’s alpha value better than 0.7, it is deemed to be consistent ( Hair et al., 2014 ). Convergent validity testing reveals the average variance extracted value (AVE), which should be greater than 0.6 Hair et al. (2014) . The discriminant validity test is carried out by examining the value of the cross-loading factor and the criterion of the heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT). The HTMT ratio should not exceed 0.85 ( Henseler et al., 2015 ). Finally, the multi-collinearity test focuses on determining if there is a relationship between exogenous variables. The tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values are used to analyze the extent of collinearity. A VIF value of less than 10 indicates the presence of a collinearity-free indicator. Multi-collinearity is not an issue in our study as we used reflective measuring items.

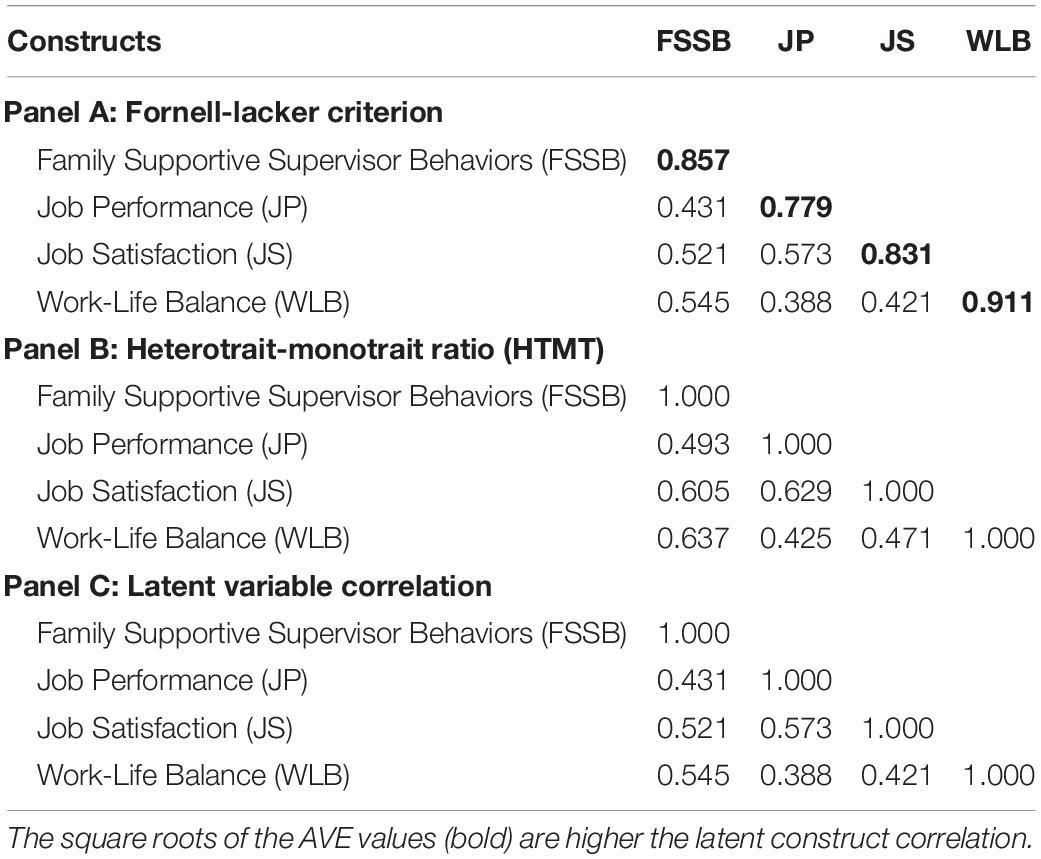

The results of convergent validity and composite reliability are presented in Table 2 . We have observed that Cronbach’s alpha values for the construct lie between 0.820 and 0.907, which are above the cut-off value of 0.6, and all latent variables had Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.7. So, it can be concluded that the construct of our study has met the reliability criteria. Additionally, the indicator loadings range between 0.709 and 0.918, which has been presented in Figure 2 , suggesting good content validity. Furthermore, the AVE value of our study variable is more than 0.50, indicating that convergent validity has been established. Furthermore, the results of discriminant validity are presented in Table 3 . From the Fornell-Lacker Criterion in Panel A of Table 3 , we noted the square roots of the AVE values (bold) are higher than the latent construct correlation. We also found that the HTMT ratio in Panel B of Table 3 between variables was less than 0.85. Henceforth, the Fornell-Lacker Criterion and HTMT ratio indicates the discriminant validity of the construct. In panel C of Table 3 , the correlation between constructs is less than 0.90, showing no multicollinearity issue in the model ( Pallant, 2011 ; Hair et al., 2013 ).

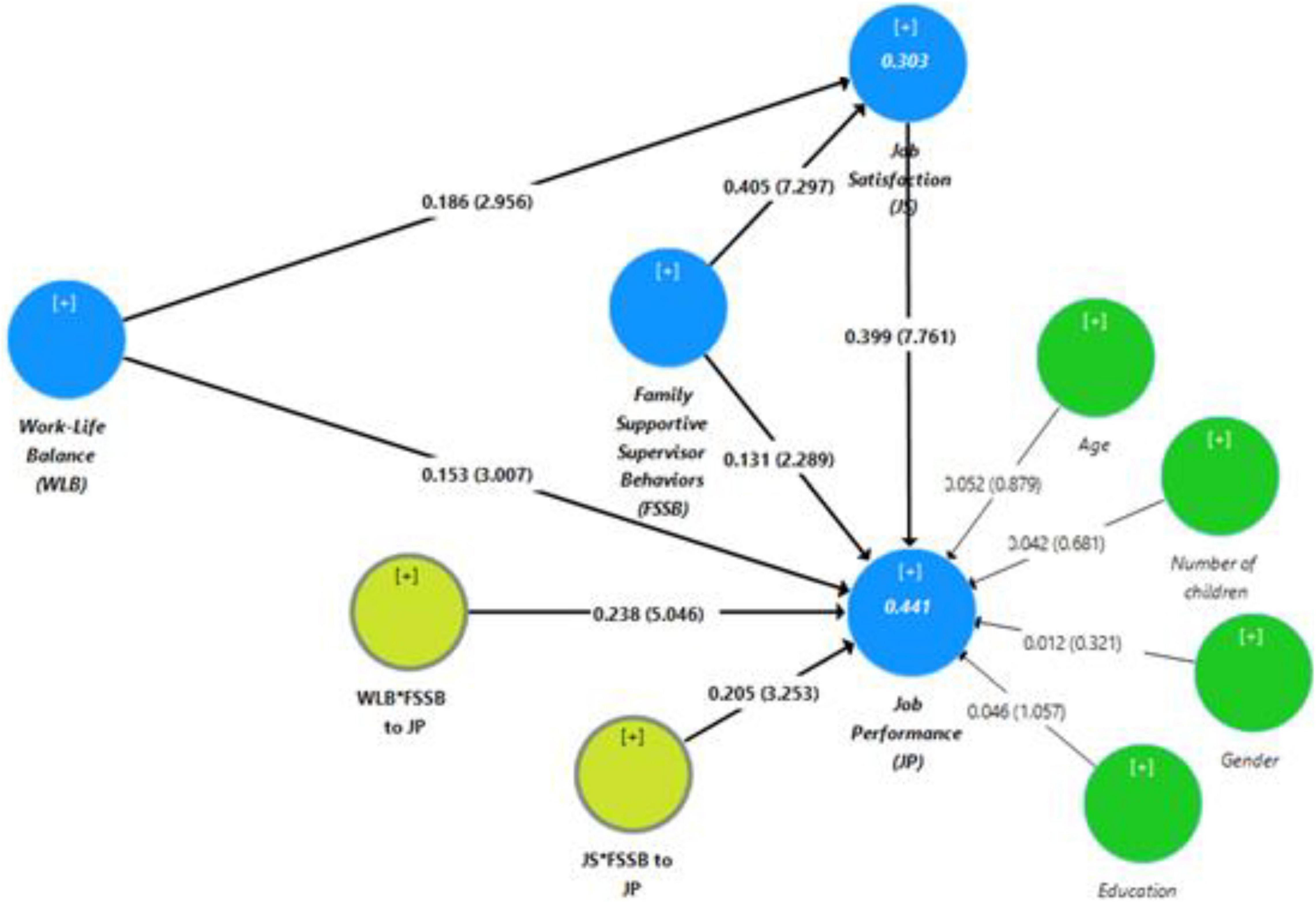

Figure 2. Result of structural model.

Table 3. Discriminant validity and latent variable correlation.

Structural Model Evaluation

Once the measurement model had met all the thresholds, the next step was to test the structural model. The r-square (reliability indicator) for endogenous components can be used to evaluate the structural model. The goal of variance analysis (R2) is to identify how exogenous variables affect endogenous variables. Figure 2 shows that R 2 of 0.44 of job performance indicates that work-life balance, family-supportive supervisor behaviors, and job satisfaction explain 44 percent of the job performance variable, while the remaining 56 percent is explained by outside factors. Job satisfaction’s R 2 of 0.304 indicates that work-life balance, family-supportive supervisor behaviors, and job performance explain 30.4 percent of the job satisfaction variable. In contrast, the remaining 69.6 percent is explained by components other than those explored in this study. The R 2 of the endogenous variables job performance and job satisfaction in our study model is greater than 20%, indicating a good model ( Hair et al., 2014 ).

Hypothesis Testing

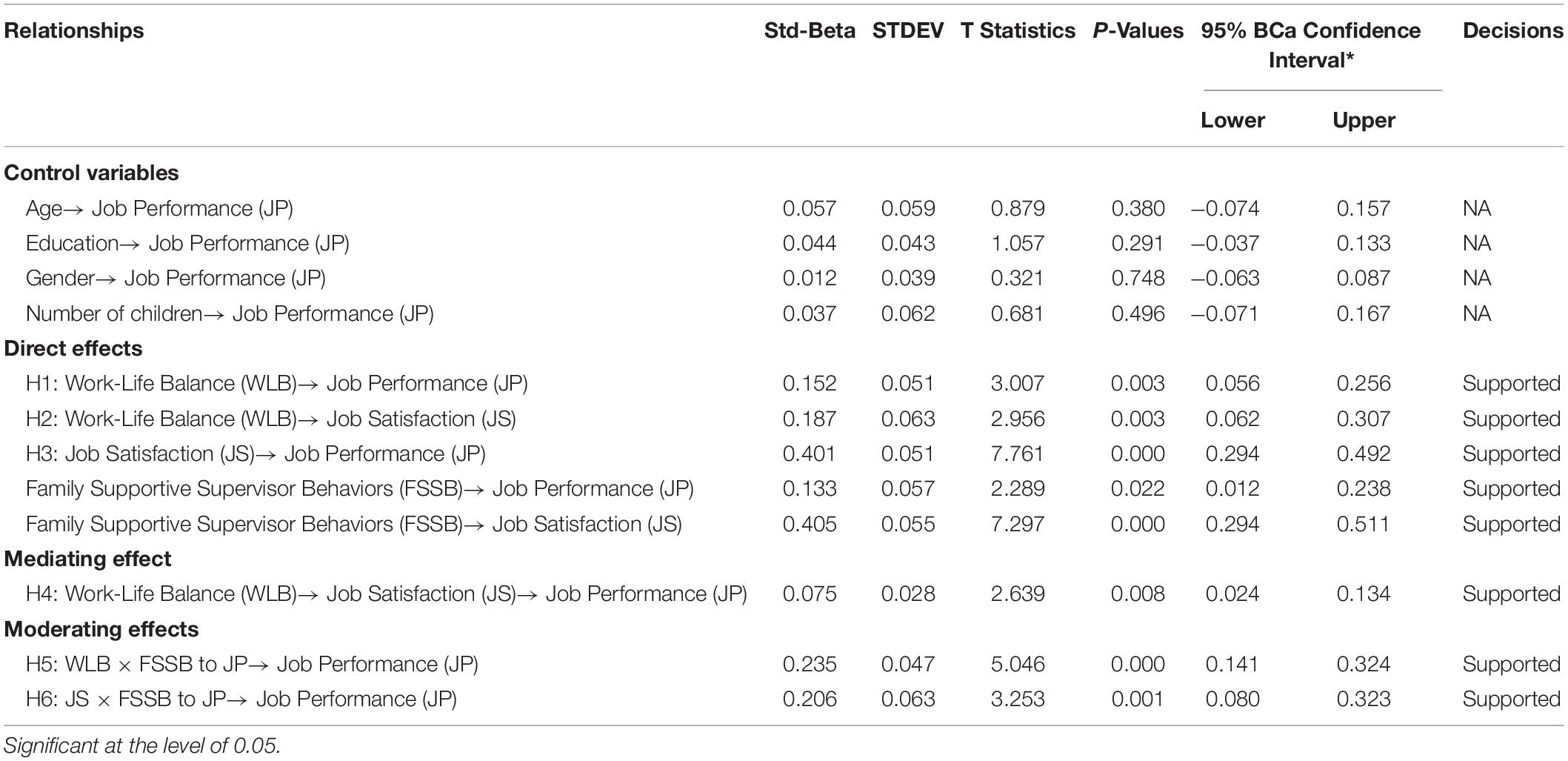

For Hypothesis testing, resampling with bootstrapping can be used to compute the statistical t value. This study considered 5,000 sub-sample for bootstrapping and a two-tail significance level with biased correction. The empirical results for hypothesis testing are presented in Figure 2 and Table 4 . Our hypotheses are supported by the empirical results at the significance level of 5%.

Table 4. Results for direct effects, mediating effect, and moderating effect.

Conclusion and Discussion

Theoretical implications.

Employees who have a poor work-life balance suffer from reduced productivity and low employee performance ( Naithani, 2010 ). In contrast, employees with a healthy work-life balance have improved job performance ( Roberts, 2008 ; Ryan and Kossek, 2008 ). In this regard, our findings demonstrate that the direct effect of work-life balance on job performance is significant with a coefficient of 0.152 (T-statistic of 3.007), suggesting a positive relationship between work-life balance and job performance. These empirical results also suggest that the employee’s job performance will also increase with a higher work-life balance. The respondents in the study also commented on their readiness to be flexible at work when needed, and they underlined that they are not ready to sacrifice their personal lives for work. Thus, the empirical findings lend strong support to our hypothesis H1. Our results are in line with the social exchange theory that a balanced proportion of time given by an employee to work-life and life-outside of work will make the employee more productive ( Brough et al., 2008 ; Roberts, 2008 ; Ryan and Kossek, 2008 ; Hofmann and Stokburger-Sauer, 2017 ). In support of the WLB and performance nexus, French et al. (2020) and Haar et al. (2014) stated that a high work-life balance also makes individuals yield to their higher job performance. Therefore, SMEs need to create a work-life balance supportive culture in the organization in order to bring out employees’ best performances, which could lead to better firm performance. The fact is that the entanglements between work and family are a significant source of psychological discomfort for employees ( Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012 ), which causes poor performance. Additionally, Lamane-Harim et al. (2021) suggested that WLB could lead to better employee outcomes in Spanish SMEs. As a result, both employees and employers must work together to foster a work-life balance-supportive culture in the organization, which is especially difficult in the SME sector.

According to Victoria et al. (2019) , satisfied and prosperous family life could lead to success and satisfaction at work. Therefore, the importance of work-life in employee job satisfaction is indicated in the literature ( Dousin et al., 2019 ). Concerning that affirmation, this study’s evidence demonstrates that the effect of work-life balance on job satisfaction is significant with a coefficient of 0.187 (with a T-statistic value of 2.95), which is indicative of a positive relationship between work-life balance and job satisfaction. This finding implies that with a higher work-life balance, the job satisfaction of employees will also increase. Henceforth, the current results are strongly supported by hypothesis H2. These findings are in line with Haar et al. (2014) ; Dousin et al. (2019) , and many others. Their studies also found that work-life balance has a positive effect on job satisfaction; namely, the higher the work-life balance, the higher the job satisfaction of employees. Flexible working hours, given autonomy, and company policies that support the creation of a balance between work and personal life will lead to higher job satisfaction ( French et al., 2020 ). Feeney and Stritch (2019) stated that family-friendly policies and a culture of family support are essential in generating a healthy work climate. Henceforth, job satisfaction will increase. Additionally, creating a family-supporting culture, flexible working hours, and autonomy could not be done in the SME industry as the working environment is different from that of large organizations. However, suppose SMEs take the initiative to create some sort of flexible working hours and give some autonomy depending on their position inside the company. In that case, the employees could be more satisfied, especially if the primary intention is to increase employee productivity and performance. In support of this statement, our findings have found a positive influence of job satisfaction on job performance.

Job satisfaction and job performance are widely studied relationships in HRM and organizational contexts. Most studies have discovered a positive relationship between job satisfaction and job performance ( Dormann and Zapf, 2001 ; Saari and Judge, 2004 ; Crede et al., 2007 ; Luthans et al., 2007 ; Tschopp et al., 2014 ; Krishnan et al., 2018 ; Jermsittiparsert et al., 2019 ; Zhao et al., 2019 ; Abdirahman et al., 2020 ). As expected, in the current context of the study, we also found that the effect of job satisfaction on job performance is significant, with a coefficient of 0.401 (with a T-statistic value of 7.761). Hence, the current empirical findings lend strong support to H3 that job satisfaction will increase job performance. Therefore, in line with the extant studies, we also argue that SMEs should attempt to keep employees satisfied with their jobs so they can generate their best performance. The organizational theory suggests that perceived job satisfaction makes employees more committed toward their jobs, hence better output. In the SME case, work–life balance and a supportive culture could play an important role in making employees more committed and satisfied, which will increase job performance. Our hypothesis rectifies this assertation that H3 work-life balance has positive effects on job satisfaction.

In their study, Haider et al. (2017) have discussed how work-life balance increases employee job performance via influencing psychological well-being. Job satisfaction is one of the main components of psychological well-being at the workplace. Therefore, on the mediating role of job satisfaction, our findings demonstrate that the relationship between work-life balance and job performance is mediated by job satisfaction (with a coefficient of 0.075 and a T-statistic value of 2.64). Since there is a direct relationship between work-life balance and job performance, it can be concluded that the mediation is a partial mediation rather than a full one. Thus, our hypothesis H4 is accepted. The current empirical findings also support the past empirical studies, as Dousin et al. (2019) found the mediation role of job satisfaction between employee work-life balance and job performance in a medical context. Hence, our findings imply that work-life balance improves job performance by increasing job satisfaction.

Family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) in the organization are about work-family spillover ( García-Cabrera et al., 2018 ) by boosting employee job satisfaction autonomy and minimizing work pressure ( Marescaux et al., 2020 ). Hence, it has been able to increase job satisfaction and performance. In this regard, although we do not hypothesize the direct effect of family-supportive supervisor behaviors, our findings confirm that FSSB positively influences job satisfaction and performance. Therefore, the existence of FSSB is essential to improve employees’ job satisfaction and job performance. Hence, these findings agree with the past studies that present a positive influence of FSSB on job satisfaction and job performance ( Rofcanin et al., 2018 ; Talukder et al., 2018 ; Campo et al., 2021 ). Henceforth, these findings confirm the assertion of social exchange theory and organizational support theory that supervisors’ formal and informal support further increase employees’ attitude toward the job, which improves job satisfaction and job performance ( Talukder et al., 2018 ).

Furthermore, our empirical results indicate that the interaction between FSSB and work-life balance positively affects job performance (with a coefficient of 0.235 and a t-statistic of 5.04). These findings suggest that when FSSB interacts with work-life balance, it attenuates the link between work-life balance and job satisfaction and job performance. As a result, the current findings provide significant support for our hypothesis H5. Kim et al. (2017) discovered that supervisory support could increase the link between deep acting and work performance. On the other hand, Alias (2021) suggest that supervisory support cannot moderate the relationship between flexible work arrangements and employee performance. Our findings, however, offer evidence that contradicts the assertion of Alias (2021) , in which we demonstrated that there could be moderating effects on the relationship between work-life balance and job performance. Hence, our finding adds novel evidence in the area of work-life balance and job performance. Again, these findings reinforce the need for a work–life balance supportive culture in the organization, as it could facilitate supervisory actions to a certain degree in supporting employees’ family and personal life.

Based on hypothesis H5, we concurred on the moderating impact of FSSB on the link between job satisfaction and job performance. We evaluated the moderating influence of FSSB on this relationship. The current study’s empirical findings indicate that the interaction effects of FSSB and work satisfaction on job performance are relatively positive (with a coefficient of 0.206 and a t-statistic of 3.25). These findings suggest that when FSSB interacts with work-life balance and job satisfaction, it moderates the link between work-life balance and job satisfaction and job performance. Hence, the current empirical results verify our claim and offer substantial support for Hypothesis H6. The interaction effects are reasonably sensible in that when employees are satisfied and believe that they will receive the required support from their boss while coping with family or personal concerns. As a result, when the level of belief and job satisfaction rises, so does the level of job commitment and engagement, resulting in higher job performance. In this regard, the current study contributes to the body of evidence on the FSSB’s moderating effects on job satisfaction and performance.

Practical Implications

In support of the WLB-performance nexus, several studies have indicated that an excellent work balance also leads to more extraordinary job performance. Thus, SMEs must foster a work–life balance-friendly culture to bring out the best in their employees, which may contribute to improved business/firm performance. In reality, the entanglements between work and family are a major source of psychological distress for employees, resulting in poor performance. Henceforth, the implementation of various WLB practices is suggested for Indonesian SMEs, particularly those not required by regulation or legal minimum to fulfill the needs of all employees. Furthermore, we also recommend that firms should provide separate WLB practice alternatives for men and women because the impacts of WLB on job satisfaction are varied, as suggested by Lamane-Harim et al. (2021) . Furthermore, family-supportive supervisor behaviors are important for promoting employees’ performance. Therefore, firms and supervisors provide some support to employees to handle and overcome family-related issues. In this regard, our findings emphasized the need to establish a work–life balance supportive culture in the firm as it might assist supervisory activities in supporting workers’ family and personal life to a different extent. In addition, managers may gain useful knowledge to create efficient job systems to improve job performance in SMEs, taking into account the relevance of work-life balance, family supportive supervisor behaviors, and job satisfaction. Individuals in SMEs can increase job performance by balancing their work and personal life. The impact of SMEs on employee work-life balance and performance is a fascinating topic. As a result, work-life balance will have a bigger impact on the organization’s overall performance.

Limitation and Future Research

We propose that this research be expanded into a longitudinal study in the future, providing a greater grasp of the issue. However, the findings may not be generalizable, and the results must be interpreted in light of the evolving context and economic conditions in which the study was done. Additionally, future studies should look into religiosity as a moderator of the relationship between WLB and job satisfaction and performance. It’s important to think about becoming a moderator since employees who have a strong understanding of religion and put it into practice have a good sense of self-control. It could have a different effect when attempting to explain the link between work-life balance and job performance. Stress and anxiety are one of the most essential factors to consider when attempting to explain the link between WLB and job performance. Many employees may feel stressed and anxious about their professional and personal development while working in SMEs. As a result, as moderators in this association, it may be an important aspect to investigate in future research. Finally, future research should look at deviant behavior as a result of work-life balance and job satisfaction. Employees with a poor work-life balance and dissatisfaction are more likely to engage in deviant behavior.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided by the first author upon request.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdirahman, H. I. H., Najeemdeen, I. S., Abidemi, B. T., and Ahmad, R. (2020). The relationship between job satisfaction, work-life balance and organizational commitment on employee performance. Adv. Business Res. Int. J. 4, 42–52. doi: 10.24191/abrij.v4i1.10081

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Achour, Y., Ouammi, A., Zejli, D., and Sayadi, S. (2020). Supervisory model predictive control for optimal operation of a greenhouse indoor environment coping with food-energy-water nexus. IEEE Access 8, 211562–211575. doi: 10.1109/access.2020.3037222

Aeknarajindawat, N., and Jermsittiparsert, K. (2020). Does organization justice influence the organization citizenship behavior, job satisfaction & organization outcomes? Syst. Rev. Pharm. 11, 489–496.

Google Scholar

Alias, E. S. B. (2021). Supervisor support as a moderator between flexible working arrangement and job performance–Malaysia evidence. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 12, 525–539.

Allen, T. D., French, K. A., Dumani, S., and Shockley, K. M. (2020). A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 105, 539–576. doi: 10.1037/apl0000442

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., and Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: perceived leader support. Leadersh. Q. 15, 5–32. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.003

Anitha, J. (2014). Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 63, 308–323. doi: 10.1108/ijppm-01-2013-0008

Babin, B. J., and Boles, J. S. (1998). Employee behavior in a service environment: a model and test of potential differences between men and women. J. Market. 62, 77–91. doi: 10.2307/1252162

Badan Pusat Statistik (2020). Statistik Indonesia dalam Infografis 2020. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Barling, J., and Macewen, K. E. (1992). Linking work experiences to facets of marital functioning. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 573–583. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130604

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bosch, M. J., Heras, M., Las, Russo, M., Rofcanin, Y., and Grau i Grau, M. (2018). How context matters: the relationship between family supportive supervisor behaviours and motivation to work moderated by gender inequality. J. Busi. Res. 82, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.026

Brough, P., Holt, J., Bauld, R., Biggs, A., and Ryan, C. (2008). The ability of work-life balance policies to influence key social/organisational issues. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 46, 261–274. doi: 10.1177/1038411108095758.

Campo, A. M. D. V., Avolio, B., and Carlier, S. I. (2021). The relationship between telework, job performance, work–life balance and family supportive supervisor behaviours in the context of COVID-19. Glob. Bus. Rev. [Epub ahead of print].

Cegarra-Leiva, D., Sánchez-Vidal, M. E., and Cegarra-Navarro, J. G. (2012). Work life balance and the retention of managers in Spanish SMEs. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 23, 91–108. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.610955

Chen, Z. X., Aryee, S., and Lee, C. (2005). Test of a mediation model of perceived organizational support. J. Vocation. Behav. 66, 457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.01.001

Chin, W. W., and Dibbern, J. (2010). “An introduction to a permutation based procedure for multi-group PLS analysis: results of tests of differences on simulated data and a cross cultural analysis of the sourcing of information system services between Germany and the USA,” in Handbook of Partial Least Squares , eds V. Esposito Vinzi, W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang (Berlin: Springer), 171–193. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_8

Clark, M. A., Rudolph, C. W., Zhdanova, L., Michel, J. S., and Baltes, B. B. (2017). Organizational support factors and work–family outcomes: exploring gender differences. J. Fam. Issues 38, 1520–1545. doi: 10.1177/0192513x15585809

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A., and Shore, L. M. (2007). The employee–organization relationship: where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 17, 166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.03.008

Cranny, C. J., Smith, P. C., and Stone, E. (1992). Job satisfaction: how people feel about their jobs. Pers. Psychol. 46, 365–472.

Crede, M., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., Dalal, R. S., and Bashshur, M. (2007). Job satisfaction as mediator: an assessment of job satisfaction’s position within the nomological network. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 80, 515–538. doi: 10.1348/096317906x136180

Cuéllar-Molina, D., García-Cabrera, A. M., and Lucia-Casademunt, A. M. (2018). Is the institutional environment a challenge for the well-being of female managers in Europe? The mediating effect of work–life balance and role clarity practices in the workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:1813. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091813

Direnzo, M. S., Greenhaus, J. H., and Weer, C. H. (2015). Relationship between protean career orientation and work-life balance: a resource perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 538–560. doi: 10.1002/job.1996

Dormann, C., and Zapf, D. (2001). Job satisfaction: a meta-analysis of stabilities. J. Organ. Behav. 22, 483–504. doi: 10.1002/job.98

Dousin, O., Collins, N., and Kaur Kler, B. (2019). Work-life balance, employee job performance and satisfaction among doctors and nurses in Malaysia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 9, 306–319. doi: 10.5296/ijhrs.v9i4.15697

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., and Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 42–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

Feeney, M. K., and Stritch, J. M. (2019). Family-friendly policies, gender, and work–life balance in the public sector. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 39, 422–448. doi: 10.1177/0734371X17733789

French, K. A., Allen, T. D., Miller, M. H., Kim, E. S., and Centeno, G. (2020). Faculty time allocation in relation to work-family balance, job satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 120:103443. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103443

García-Cabrera, A. M., Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., Cuéllar-Molina, D., and Padilla-Angulo, L. (2018). Negative work-family/family-work spillover and well-being across Europe in the hospitality industry: the role of perceived supervisor support. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 26, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.01.006

Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity, american sociological review. Am. Sociol. Rev. 25, 161–178. doi: 10.2307/2092623

Greenhaus, J. H., Ziegert, J. C., and Allen, T. D. (2012). When family-supportive supervision matters: relations between multiple sources of support and work-family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.008

Haar, J. M., Russo, M., Suñe, A., and Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work-life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: a study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 85, 361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.010

Haider, S., Jabeen, S., and Ahmad, J. (2017). Moderated mediation between work life balance and employee job performance: the role of psychological wellbeing and satisfaction with co-workers. Rev. Psicol. Trabajo Organ. 34, 1–24.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 46, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 26, 106–121. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hair, J., Wolfinbarger, M., Money, A. H., Samouel, P., and Page, M. J. (2015). Essentials of Business Research Methods. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Yragui, N. L., Bodner, T. E., and Hanson, G. C. (2009). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). J. Manag. 35, 837–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328510

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Heras, M. L., Rofcanin, Y., Escribano, P. I., Kim, S., and Mayer, M. C. J. (2021). Family-supportive organisational culture, work–family balance satisfaction and government effectiveness: evidence from four countries. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 31, 454–475. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12317

Hofmann, V., and Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2017). The impact of emotional labor on employees’ work-life balance perception and commitment: a study in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 65, 47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.003

Hughes, J., and Bozionelos, N. (2007). Work-life balance as source of job dissatisfaction and withdrawal attitudes: an exploratory study on the views of male workers. Pers. Rev. 36, 145–154. doi: 10.1108/00483480710716768

ILO (2019). Financing Small Businesses in Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities/International Labour Office. Jakarta: ILO.

Jermsittiparsert, K., Suan, C., and Kaliappen, N. (2019). The mediating role of organizational commitment and the moderating role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance of educationists in public sector institutes of Thailand. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change 6, 150–171.

Kanfer, R., and Kantrowitz, T. M. (2005). “Ability and non-ability predictors of job performance,” in Psychological Management of Individual Performance , ed. S. Sonnentag (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 27–50. doi: 10.1002/0470013419.ch2

Keelan, R. (2015). A M ā ori perspective on well-being. He Kupu 4:15.

Kelley, H. H., LeBaron-Black, A., Hill, E. J., and Meter, D. (2021). Perceived family and partner support and the work-family interface: a meta-analytic review. Rev. Psicol. Trabajo Organ. 37, 143–155. doi: 10.5093/jwop2021a15

Kementerian Koperasi dan UKM Republik Indonesia (2019). Laporan Kinerja Kementerian Koperasi dan UKM Tahun 2019. Jakarta: Kementerian Koperasi dan UKM Republik Indonesia.

Kerdpitak, C., and Jermsittiparsert, K. (2020). The effects of workplace stress, work-life balance on turnover intention: an empirical evidence from pharmaceutical industry in Thailand. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 11, 586–594.

Kim, H. J., Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., and Jun, J. K. (2017). Is all support equal? The moderating effects of supervisor, coworker, and organizational support on the link between emotional labor and job performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 20, 124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brq.2016.11.002

Kim, T. Y., Liu, Z., and Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). Leader-member exchange and job performance: the effects of taking charge and organizational tenure. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 216–231. doi: 10.1002/job.1971

Konrad, A. M., and Mangel, R. (2000). The impact of work-life programs on firm productivity. Strateg. Manag. J. 21, 1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/1097-0266(200012)21:12<1225::aid-smj135>3.0.co;2-3

Krishnan, R., Loon, K. W., and Tan, N. Z. (2018). The effects of job satisfaction and work-life balance on employee task performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 8, 652–662. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Lamane-Harim, J., Cegarra-Leiva, D., and Sánchez-Vidal, M. E. (2021). Work–life balance supportive culture: a way to retain employees in Spanish SMEs. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. [Epub ahead of print].

Lavoie, A. (2004). Work-life balance and SMEs: avoiding the “One-Size-Fits-All” trap. CFIB Res. 1–13.

Lee, L. Y., and Veasna, S. (2013). The effects of social exchange perspective on employee creativity: a multilevel investigation. Psychol. Res. 3:660.

Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., García-Cabrera, A. M., and Cuéllar-Molina, D. G. (2015). National culture, work-life balance and employee well-being in European tourism firms?: the moderating effect of uncertainty avoidance values. Tour. Manage. Stud. 11, 62–69.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., and Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Luthans, F., Norman, S. M., Avolio, B. J., and Avey, J. B. (2008). The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—employee performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 219–238.

Marescaux, E., Rofcanin, Y., Las Heras, M., Ilies, R., and Bosch, M. J. (2020). When employees and supervisors (do not) see eye to eye on family supportive supervisor behaviours: the role of segmentation desire and work-family culture. J. Vocat. Behav. 121:103471. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103471

Mendis, M. D. V. S., and Weerakkody, W. A. S. (2017). The impact of work life balance on employee performance with reference to telecommunication industry in Sri Lanka: a mediation model. Kelaniya J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 12, 72–100. doi: 10.4038/kjhrm.v12i1.42

Moonsri, K. (2018). The influence of job satisfaction affecting organizational commitment of the small and medium business employee. Asian Administr. Manag. Rev. 1, 138–146. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689511

Naithani, D. (2010). Overview of work-life balance discourse and its relevance in current economic scenario. Asian Soc. Sci. 6, 148–155.

Naqvi, S. M. H., Khan, M. A., Kant, A. Q., and Khan, S. N. (2013). Job stress and employees’ productivity: case of Azad Kashmir public health sector. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 5, 525–542.

Noah, Y., and Steve, M. (2012). Work environment and job attitude among employees in a Nigerian work organization. J. Sustain. Soc. 1, 36–43.

Nohe, C., Michel, A., and Sonntag, K. (2014). Family-work conflict and job performance: a diary study of boundary conditions and mechanisms. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 339–357. doi: 10.1002/job.1878

Obrenovic, B., Jianguo, D., Khudaykulov, A., and Khan, M. A. S. (2020). Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: a job performance model. Front. Psychol. 11:475. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475

Ollier-Malaterre, A., and Foucreault, A. (2017). Cross-national work-life research: cultural and structural impacts for individuals and organizations. J. Manage. 43, 111–136. doi: 10.1177/0149206316655873

Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step guide To Data Analysis Using SPSS. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 4 Edn, Vol. 3rd. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Poelmans, S., O’Driscoll, M., and Beham, B. (2005). “An overview of international research on the work-family interface,” in Work and Family: An International Research Perspective , ed. S. A. Y. Poelmans (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 3–46. doi: 10.4324/9781410612601

Pramono, R., Sondakh, L. W., Bernarto, I., Juliana, J., and Purwanto, A. (2021). Determinants of the small and medium enterprises progress: a case study of SME entrepreneurs in Manado, Indonesia. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 8, 881–889.

Preena, R. (2021). Impact of work-life balance on employee performance: an empirical study on a shipping company in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 10, 48–73.

Putnik, K., Houkes, I., Jansen, N., Nijhuis, F., and Kant, I. (2020). Work-home interface in a cross-cultural context: a framework for future research and practice. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 31, 1645–1662. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1423096

Rawshdeh, Z. A., Makhbul, Z. K. M., Shah, N. U., and Susanto, P. (2019). Impact of perceived socially responsible-HRM practices on employee deviance behavior. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 9, 447–466.

Redmond, J., Valiulis, M., and Drew, E. (2006). Literature Review of Issues Related to Work-Life Balance, Workplace Culture and Maternity/Childcare Issues. Dublin: Crisis Pregnancy Agency.

Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., and Straub, D. W. (2012). Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly”. J. Educ. Bus. 36, iii–xiv. doi: 10.2307/41410402

Rini, R., Yustina, A. I., and Santosa, S. (2020). How work family conflict, work-life balance, and job performance connect: evidence from auditors in public accounting firms. J. ASET 12, 144–154.

Roberts, E. (2008). Time and work-life balance: the roles of “temporal customization” and “life temporality.”. Gend. Work Organ. 15, 430–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00412.x

Rofcanin, Y., de Jong, J. P., Las Heras, M., and Kim, S. (2018). The moderating role of prosocial motivation on the association between family-supportive supervisor behaviours and employee outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 107, 153–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.04.001

Ryan, A. M., and Kossek, E. E. (2008). Work-life policy implementation: breaking down or creating barriers to inclusiveness? Hum. Resour. Manag. 47, 295–310. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20213

Saari, L. M., and Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 43, 395–407. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20032

Sekaran, U., and Bougie, R. (2017). Metode Penelitian Bisnis, Edisi 6 Buku 2. Jakarta: Salemba Empat.

Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S. A. Y., Lapierre, L. M., Cooper, C. L., Michael, O., et al. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work-family conflict. Pers. Psychol. 60, 805–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00092.x

Suriana, E., Razak, A. Z. A. A., Hudin, N. S., and Sharif, S. (2021). Supervisor Support as a moderator between flexible working arrangement and job performance- Malaysia evidence. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 12, 525–539.

Surya, B., Menne, F., Sabhan, H., Suriani, S., Abubakar, H., and Idris, M. (2021). Economic growth, increasing productivity of SMEs, and open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 7:20. doi: 10.3390/joitmc7010020

Talukder, A. K. M., Vickers, M., and Khan, A. (2018). Supervisor support and work-life balance: impacts on job performance in the Australian financial sector. Personnel Rev. 47, 727–744. doi: 10.1108/pr-12-2016-0314

Thevanes, N., and Mangaleswaran, T. (2018). Relationship between work-life balance and job performance of employees. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 20, 11–16.

Tschopp, C., Grote, G., and Gerber, M. (2014). How career orientation shapes the job satisfaction-turnover intention link. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 151–171. doi: 10.1002/job.1857

Vayre, É (2019). Impacts of telework on the worker and his professional, family and social spheres. Le Travail Humain 82, 1–39.

Victoria, A. O., Olive, E. U., Babatunde, A. H., and Nanle, M. (2019). Work-life balance and employee performance: a study of selected peposit money banks in Lagos State, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 5, 1787–1795. doi: 10.32861/jssr.512.1787.1795

Walumbwa, F. O., Peterson, S. J., Avolio, B. J., and Hartnell, C. A. (2010). An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 63, 937–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01193.x

Wang, P., Walumbwa, F. O., Wang, H., and Aryee, S. (2013). Unraveling the relationship between family-supportive supervisor and employee performance. Group Organ. Manag. 38, 258–287. doi: 10.1177/1059601112472726

Wesarat, P. O., Majid, A. H., Shari, M. Y., Khaidir, A., and Susanto, P. (2018). Mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between work-life balance and job performance among academics: data screening. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 7, 214–216.

World Bank (2020). Small and Medium Enterprises Finance. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed January 10, 2022).

Zhao, K., Zhang, M., Kraimer, M. L., and Yang, B. (2019). Source attribution matters: mediation and moderation effects in the relationship between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 40, 492–505. doi: 10.1002/job.2345

Keywords : work-life balance, job satisfaction, job performance, family-supportive supervisor behaviors, Indonesia

Citation: Susanto P, Hoque ME, Jannat T, Emely B, Zona MA and Islam MA (2022) Work-Life Balance, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance of SMEs Employees: The Moderating Role of Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 13:906876. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.906876

Received: 29 March 2022; Accepted: 27 April 2022; Published: 21 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Susanto, Hoque, Jannat, Emely, Zona and Islam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Enamul Hoque, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Job performance in healthcare: a systematic review

Marcel krijgsheld, lars g tummers, floortje e scheepers.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Sep 9; Accepted 2021 Nov 30; Collection date 2022.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Healthcare organisations face major challenges to keep healthcare accessible and affordable. This requires them to transform and improve their performance. To do so, organisations must influence employee job performance. Therefore, it is necessary to know what the key dimensions of job performance in healthcare are and how these dimensions can be improved. This study has three aims. The first aim is to determine what key dimensions of job performance are discussed in the healthcare literature. The second aim is to determine to which professionals and healthcare organisations these dimensions of job performance pertain. The third aim is to identify factors that organisations can use to affect the dimensions of job performance in healthcare.

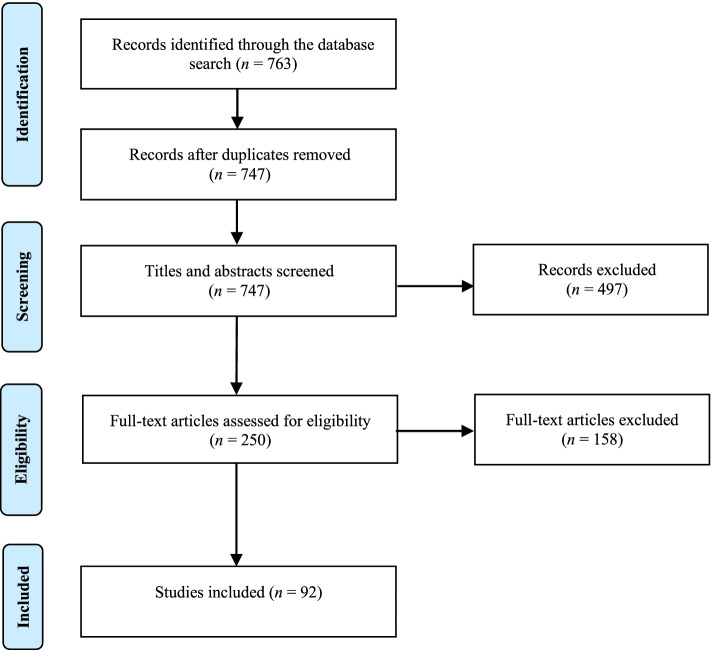

A systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The authors searched Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Books, which resulted in the identification of 763 records. After screening 92 articles were included.

The dimensions – task, contextual, and adaptative performance and counterproductive work behaviour – are reflected in the literature on job performance in healthcare. Adaptive performance and counterproductive work behaviour appear to be under-researched. The studies were conducted in different healthcare organisations and pertain to a variety of healthcare professionals. Organisations can affect job performance on the macro-, meso-, and micro-level to achieve transformation and improvement.

Based on more than 90 studies published in over 70 journals, the authors conclude that job performance in healthcare can be conceptualised into four dimensions: task, contextual and adaptive performance, and counterproductive work behaviour. Generally, these dimensions correspond with the dimensions discussed in the job performance literature. This implies that these dimensions can be used for further research into job performance in healthcare. Many healthcare studies on job performance focus on two dimensions: task and contextual performance. However, adaptive performance, which is of great importance in constantly changing environments, is under-researched and should be examined further in future research. This also applies to counterproductive work behaviour. To improve job performance, interventions are required on the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels, which relate to governance, leadership, and individual skills and characteristics.

Keywords: Systematic review, Job performance, Task performance, Contextual performance, Adaptive performance, Counterproductive work behaviour, Healthcare

Together with governments and policymakers, healthcare organisations face major challenges to ensure healthcare remains accessible and affordable. This requires healthcare organisations to transform and improve their performance. These challenges cannot be met without the involvement and excellent performance of healthcare employees.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) expects that in 2050, almost 27% of the population will be over 65 years old and more than 10% will be over 80 [ 1 ]. This may lead to increasing demand for healthcare. According to the OECD, healthcare expenditure in terms of gross domestic product will grow from 8.8% in 2017 to 10.2% in 2030 in OECD countries [ 1 ]. A record amount of money is being spent on healthcare, and this is expected to further increase due to pressure arising from, among other factors, an ageing population. However, advances in medical technology and rising public expectations regarding healthcare services also contribute to increasing health expenditure [ 2 , 3 ]. Accessibility is not the only challenge arising from an ageing population and the consequent increasing demand for care; a shortage of healthcare professionals is another major challenge healthcare organisations face [ 4 , 5 ]. All these challenges make healthcare perhaps one of the most important areas in which the change and improvement of organisational performance are necessary [ 2 ]. As healthcare is mainly people work, change and improvement in organisational performance will be closely linked to the performance (i.e., the actions and behaviours) of employees [ 6 ]. In other words, the job performance of healthcare professionals is of crucial importance to achieve organisational goals [ 6 – 8 ].

Job performance has been widely discussed and conceptualised in various ways [ 8 ]. This is reflected in Koopmans et al.’s [ 9 ] systematic review, in which the authors identify 17 generic and 18 job-specific frameworks. The job-specific frameworks in that study relate to the army and employees and management in the service and sales sector. However, Greenslade and Jimmieson’s (2007) framework was developed for the healthcare sector [ 10 ] based on Borman and Motowidlo’s theoretical model [ 11 ]. Based on the 35 frameworks Koopmans et al. identify four main dimensions: task performance, contextual performance, adaptive performance, and counterproductive work behaviour [ 9 ].

Task performance has a direct relationship with the organisational technical core [ 11 – 14 ]. The term refers to direct activities (such as treating patients) and indirect activities (such as hiring nurses) that are a formal part of a worker’s job [ 15 ]. Task performance is seen as an encompassing dimension that also includes aspects such as task behaviour [ 16 ], job and non-job specific tasks [ 17 ], role performance [ 18 ], technical activities [ 19 ], and action orientation [ 20 ]. Contextual performance includes, among other items, interpersonal behaviour [ 16 ], organisational citizenship behaviour [ 21 ], extra role performance [ 22 ], and peer team interaction [ 23 ]. Contextual performance concerns the broader organisational, social, and psychological environment in which a technical core must function [ 11 – 14 ]; it includes activities such as volunteering for extra work and maintaining good interpersonal relationships [ 15 ]. Adaptive performance refers to the extent to which an individual adapts to changes in work systems or work roles [ 9 ]. It is also defined as adaptability and pro-activity [ 24 ] and creative performance [ 21 ]. Attention towards adaptive performance has increased in recent decades due to the dynamic nature of work environments [ 25 ]. In earlier frameworks, adaptive performance was seen as a separate dimension [ 26 – 28 ] instead of a component of contextual performance [ 29 ]. Finally, counterproductive work behaviour refers to behaviour that is harmful to the performance of an organisation [ 30 ]. It includes, for instance, off-task behaviour, unruliness, theft, drug abuse [ 29 ], absenteeism (not attending work) and presenteeism (attending work while ill [ 31 – 33 ];).

To change and improve the performance of healthcare professionals, and thus the performance of healthcare organisations, it is important to determine whether the four dimensions can be used as a reference for job performance research in healthcare. Although Greenslade and Jimmieson (2007) propose a framework, it focuses specifically on nurses and only includes the task and contextual performance dimensions, thus having little applicability in healthcare research in general. Therefore, it is important to determine how job performance in healthcare is treated in the research literature and whether it relates to the dimensions of task, contextual, and adaptive performance and counterproductive work behaviour. To arrive at findings about whether the four dimensions can be applied to the broad field of healthcare, it is important to investigate in which sectors of healthcare and in relation to which professionals the dimensions have been used in research. Finally, to change and improve the performance of the healthcare professional, it is relevant to determine how and at which level organisations can implement changes to affect job performance. In summary, the purpose of this review is to answer the following questions:

Which of the four job performance dimensions are described in studies focusing on job performance in healthcare?

To which professionals and health organisations do the dimensions of job performance discussed in the studies pertain?

How and on which level can organisations affect the job performance of healthcare professionals?

This research was accomplished by conducting a systematic literature review. The method section describes the process of identification, screening, and assessing the eligibility of studies. The results section begins with an overview that sets out the distribution of the studies. The overview reveals in which year, and in which journal the articles were published. It also details whether studies were carried out in developed or developing countries. Further, this paper explains how it assesses the methodological quality of the studies. Following this overview, this paper presents the answers to the research questions, beginning first with the job dimensions identified in the selected studies, and then proceeding to an analysis of the type of organisations the studies examined and the healthcare professionals to which the studies pertain. Finally, the results section describes the factors that can affect job performance at different organisational levels. The discussion section discusses the results and reflects on a few of this paper’s limitations. The conclusion section provides suggestions that can be used for future research on job performance in healthcare based on this study’s findings.

The literature search was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 34 ]. To find eligible studies, four databases were searched: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Books. The goal of the research strategy was to find articles and books that relate to job performance in healthcare and include a broad scope of healthcare professionals. The search strategy is detailed in Appendix A .

Eligibility criteria

Studies included in the review must meet the following criteria. They must relate to job performance in the field of healthcare. Job performance or comparable terms, such as work performance or work behaviour, must appear in the title or abstract. Studies that examine at least one of the four dimensions or related terms are also eligible. Studies published between 1996 and December 2019 were selected. As part of the pragmatic approach to gathering literature, only studies written in English were considered. All articles published in international journals that were selected for this study must have been peer-reviewed.

Study selection

Through the search strategy, 763 records were identified, including four books. After 17 duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 747 records were screened. This resulted in the exclusion of 497 records (including three books). Although the studies are related to healthcare, job performance was not the main objective of these studies. For example, a few studies examine musculoskeletal disorders and their impact on nursing tasks [ 16 , 17 ]. Other studies focus on job satisfaction [ 18 , 19 ]. After the exclusion of these 497 studies, the authors read the remaining 250 articles in detail and analysed their eligibility. This resulted in the exclusion of another 158 studies. The grounds for exclusion are as follows. Studies that focus on a specific task, such as working with electronic healthcare systems [ 20 , 21 ], radiation therapy [ 35 ], cervical screening [ 36 ], and communication in the operating theatre [ 24 , 25 ], were excluded.

Full-text articles were not available for two studies. After completing the process of screening and analysing the articles, a total of 92 articles, including one book chapter, met the eligibility criteria. The study selection process is depicted schematically in Fig. 1 using the PRISMA flowchart [ 34 ].

Flowchart study selection

After categorising the articles by year of publication and the journals and countries in which they were published, the methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the integrated quality criteria for the review of multiple study designs [ 37 ]. Studies that could not be assessed using the ICROMS tool were assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers [ 38 ]. Because not all the selected studies directly refer to task, contextual, or adaptive performance or counterproductive work behaviour, it was imperative to assign terms, such as nursing work, tasks, or activities and indirect or direct care [ 27 , 28 ] to one of the dimensions. The assignment of the terms was accomplished using the definitions of the four dimensions. To determine whether the dimensions of job performance were used in the broad field of health care, the type of organisation in which job performance was studied was examined. In addition, it was analysed to which professionals these studies related. Finally, the factors influencing job performance were categorised into macro-, meso-, and micro-level factors. All coding can be viewed on the Open Science Framework (OSF) database.

Before answering the research questions, this paper provides an overview that sets out the distribution of the studies. The overview reveals in which year and in which journal the articles were published. It also shows whether the studies were carried out in developed or developing countries. Results of the assessment of the methodological quality of the studies are provided below.

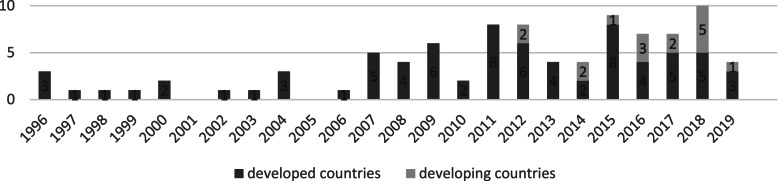

Distribution of the studies

Table 1 reveals that most studies (82.6%) were conducted in developed countries (e.g., [ 39 – 41 ]), with the United States being the most common study location (29.4% of all studies; e.g., [ 42 – 44 ]). With regard to developing countries, China was the most common study location (e.g., [ 45 , 46 ]).

Distribution of the articles in developed and developing countries

a Based on the IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2018/October

b See Appendix B . c Studies conducted in two countries

The articles included in this review were published in 76 different journals ( Appendix C ). The journals can be divided into healthcare fields, such as nursing [ 47 ], medicine [ 42 ], healthcare [ 48 ], and psychology [ 49 ], and into journals with a focus on specific topics, such as maternity [ 50 ] , ergonomics [ 51 ], and critical care [ 52 ]. Almost 20% of the articles were published in the following four journals: BMC Health Services Research, the Journal of Advanced Nursing , the International Journal of Medical Informatics, and the Journal of Managerial Psychology . Most of the studies were conducted in a single country, which raises questions about their external validity.