- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Validity – Types and Examples

Research Validity – Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Validity

Research validity is a critical concept in academic research, referring to the degree to which a study accurately measures what it intends to measure. It assesses the credibility of research results, determining whether the conclusions drawn from a study genuinely reflect the reality of the situation or variables being studied. Without validity, research findings lose their utility and relevance, making it essential for scholars to ensure that their studies are both valid and reliable.

Types of Research Validity

Research validity can be broadly divided into two main categories: Internal Validity and External Validity . Each category has distinct subtypes that serve to address specific areas of concern in the research design and findings.

1. Internal Validity

Internal validity focuses on the extent to which a study’s results can be attributed to the variables manipulated or measured rather than to other extraneous factors. High internal validity means that the study effectively demonstrates causation between the variables being examined.

- Construct Validity : This subtype of internal validity ensures that the operational definitions of variables accurately represent the theoretical constructs. For instance, if a study aims to measure intelligence, construct validity assesses whether the tools used (like IQ tests) truly reflect intelligence rather than other factors, such as memory or educational background.

- Content Validity : Content validity is concerned with whether the measurement covers the entire scope of the concept being studied. For instance, in a study on job satisfaction, content validity would ensure that questions cover all relevant aspects of job satisfaction, such as work environment, compensation, and career development.

- Criterion Validity : Criterion validity evaluates how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another established measure. It is divided into two types: concurrent validity (assessed when the measurements are taken at the same time) and predictive validity (assessed when the measure predicts a future outcome). For example, if a new test of college readiness correlates strongly with existing SAT scores, it would demonstrate high criterion validity.

2. External Validity

External validity refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be generalized to other populations, settings, or times. High external validity indicates that the results are applicable beyond the specific conditions of the study.

- Population Validity : This type of validity is concerned with the extent to which the findings can be generalized to larger populations. If a study on employee motivation is conducted only among tech industry workers, population validity examines whether the findings would apply to employees in other sectors.

- Ecological Validity : Ecological validity focuses on whether the findings can be generalized to real-world settings. For example, if a study on classroom behavior is conducted in a highly controlled lab setting, its ecological validity would be questionable because it may not accurately reflect behavior in an actual classroom environment.

Threats to Validity

Various factors can threaten the validity of research, potentially leading to biased or inaccurate conclusions. Understanding these threats is essential for researchers to mitigate their impact.

Threats to Internal Validity

- Selection Bias : Differences in the characteristics of participants across groups can distort study results.

- Maturation : Participants may change over time due to natural developmental processes, affecting study outcomes.

- History : External events occurring during the study period may influence results, particularly in longitudinal studies.

- Instrumentation : Changes in measurement tools or procedures during the study can introduce variability unrelated to the variables being studied.

Threats to External Validity

- Sample Characteristics : Using a non-representative sample limits the generalizability of the findings.

- Setting Effects : Conducting research in an artificial environment can affect behavior, reducing ecological validity.

- Timing of Measurement : Results collected at one time may not be applicable at another, especially if societal or cultural factors shift.

Strategies to Enhance Research Validity

To increase the validity of their research, scholars can implement various strategies:

- Randomization : Randomly assigning participants to different groups helps control for selection bias and improves internal validity.

- Control Groups : Using a control group allows researchers to account for extraneous variables, providing a comparison to the experimental group.

- Blinding : Blinding participants (and, when possible, researchers) to the conditions helps reduce bias in responses and analysis.

- Pilot Testing : Conducting pilot tests allows researchers to refine their measurement tools, improving construct and content validity.

- Replication : Replicating a study in different contexts or with different populations enhances external validity, demonstrating the robustness of the findings.

Let’s say a researcher wants to study how the amount of sleep high school students get each night affects their academic performance.

- Construct Validity : To measure academic performance, the researcher decides to use students’ GPAs. Construct validity examines whether GPA accurately represents academic success. If the study only looks at GPA, it might miss other aspects of academic performance, such as critical thinking or classroom engagement. To strengthen construct validity, the researcher could include additional measures, like standardized test scores or teacher evaluations, to capture the full scope of academic performance.

- Content Validity : The researcher includes a survey that asks about both weekday and weekend sleep patterns. This ensures that the study covers all relevant aspects of sleep behavior and isn’t limited to only one part of the week, enhancing content validity.

- Population Validity : Suppose this study only involves students from a single high school in a wealthy district. While the findings may apply to similar schools, they may not be generalizable to students in rural or low-income areas, who may experience different sleep-related factors (e.g., longer commute times or part-time jobs). To improve population validity, the researcher could include students from various backgrounds and locations.

- Ecological Validity : The researcher collects data through a lab experiment, where students sleep in a controlled environment with specific lights and sounds. This setup could limit ecological validity, as it doesn’t fully mimic a real bedroom environment. To improve ecological validity, the researcher could collect data from students’ actual homes to observe sleep patterns in a natural setting.

Strategies to Improve Validity in This Study

- Random Assignment : The researcher could randomly assign students to get different amounts of sleep to ensure that any differences in academic performance are likely due to sleep rather than other factors.

- Control Group : Including a control group that maintains a regular sleep schedule allows for comparisons and helps control for extraneous factors that might affect performance.

- Blinding : If possible, blinding both students and teachers to the study conditions can reduce any influence of expectations on behavior or performance.

By addressing these aspects, the researcher can increase both the internal and external validity of the study, making the findings more accurate and generalizable.

Validity is a foundational aspect of rigorous research, underpinning the credibility and applicability of a study’s findings. By understanding and addressing various types of validity and the threats associated with them, researchers can design studies that provide reliable and generalizable insights. Whether assessing internal or external validity, it is crucial for scholars to implement strategies that strengthen their research, ensuring that the results contribute meaningfully to the body of knowledge.

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research . Houghton Mifflin.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference . Houghton Mifflin.

- Trochim, W. M., Donnelly, J. P., & Arora, K. (2015). Research Methods: The Essential Knowledge Base . Cengage Learning.

- Babbie, E. R. (2020). The Practice of Social Research . Cengage Learning.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Internal Validity – Threats, Examples and Guide

External Validity – Threats, Examples and Types

Face Validity – Methods, Types, Examples

Reliability – Types, Examples and Guide

Content Validity – Measurement and Examples

Test-Retest Reliability – Methods, Formula and...

Reliability vs Validity in Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

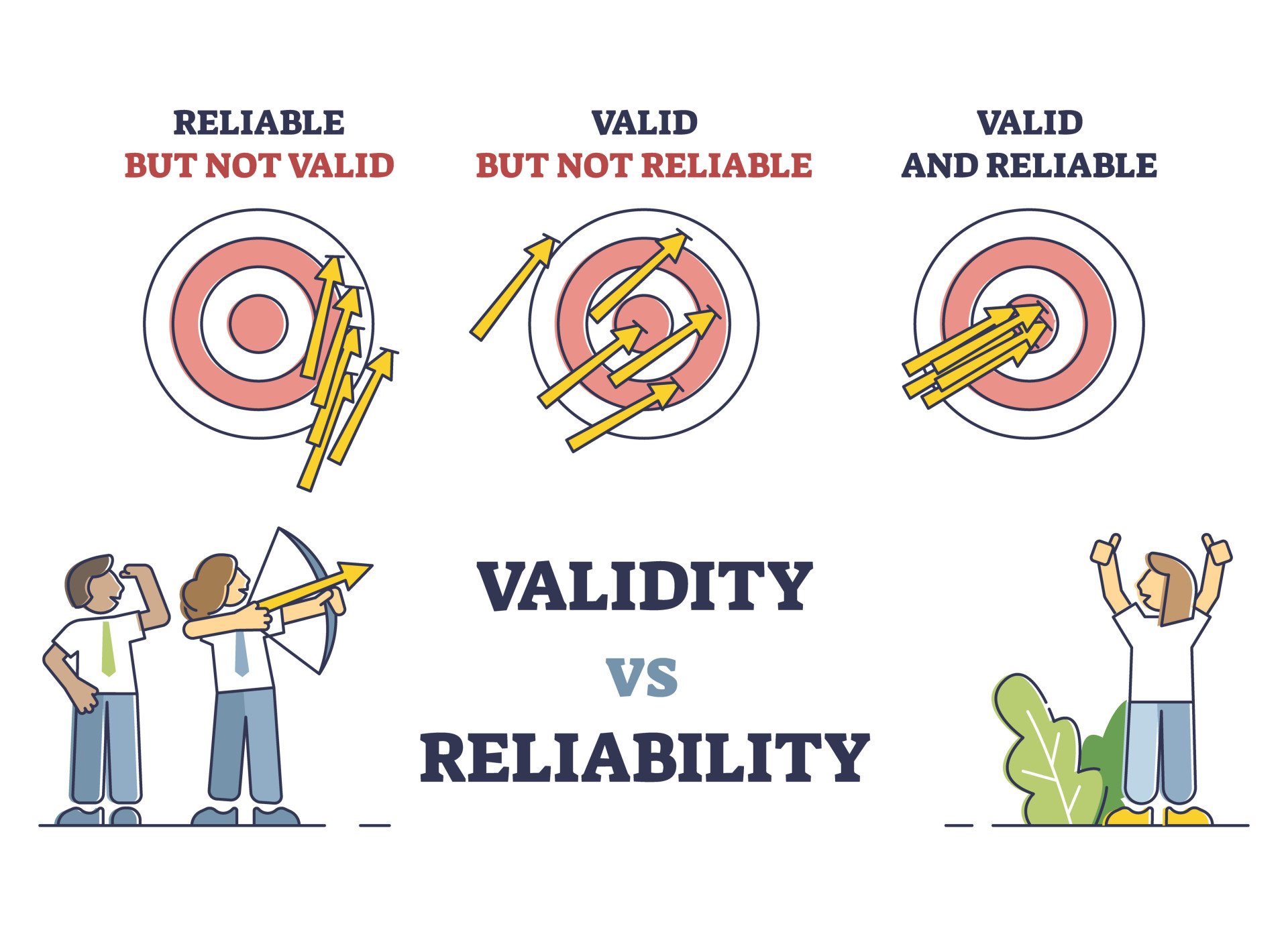

- Reliability in research refers to the consistency and reproducibility of measurements. It assesses the degree to which a measurement tool produces stable and dependable results when used repeatedly under the same conditions.

- Validity in research refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of measurements. It examines whether a research instrument or method effectively measures what it claims to measure.

- A reliable instrument may not necessarily be valid, as it might consistently measure something other than the intended concept.

While reliability is a prerequisite for validity, it does not guarantee it.

A reliable measure might consistently produce the same result, but that result may not accurately reflect the true value.

For instance, a thermometer could consistently give the same temperature reading, but if it is not calibrated correctly, the measurement would be reliable but not valid.

Assessing Validity

A valid measurement accurately reflects the underlying concept being studied.

For example, a valid intelligence test would accurately assess an individual’s cognitive abilities, while a valid measure of depression would accurately reflect the severity of a person’s depressive symptoms.

Quantitative validity can be assessed through various forms, such as content validity (expert review), criterion validity (comparison with a gold standard), and construct validity (measuring the underlying theoretical construct).

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the extent to which a psychological instrument accurately and fully reflects all the features of the concept being measured.

Content validity is a fundamental consideration in psychometrics, ensuring that a test measures what it purports to measure.

Content validity is not merely about a test appearing valid on the surface, which is face validity . Instead, it goes deeper, requiring a systematic and rigorous evaluation of the test content by subject matter experts.

For instance, if a company uses a personality test to screen job applicants, the test must have strong content validity, meaning the test items effectively measure the personality traits relevant to job performance.

Content validity is often assessed through expert review, where subject matter experts evaluate the relevance and completeness of the test items.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity examines how well a measurement tool corresponds to other valid measures of the same concept.

It includes concurrent validity (existing criteria) and predictive validity (future outcomes).

For example, when measuring depression with a self-report inventory, a researcher can establish criterion validity if scores on the measure correlate with external indicators of depression such as clinician ratings, number of missed work days, or length of hospital stay.

Criterion validity is important because, without it, tests would not be able to accurately measure in a way consistent with other validated instruments.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a particular measurement reflects the theoretical construct ( existing theory and knowledge ) it is intended to measure.

It goes beyond simply assessing whether a test covers the right material or predicts specific outcomes.

Instead, construct validity focuses on the meaning of the test scores and how they relate to the theoretical framework of the construct.

For instance, if a researcher develops a new questionnaire to evaluate aggression, the instrument’s construct validity would be the extent to which it assesses aggression as opposed to assertiveness, social dominance, and so on.

Assessing construct validity involves multiple methods and often relies on the accumulation of evidence over time.

Assessing Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of measurement results.

In simpler terms, a reliable tool produces consistent results when applied repeatedly under the same conditions.

Test-Retest Reliability

This method assesses the stability of a measure over time .

The same test is administered to the same group twice, with a reasonable time interval between tests.

The correlation coefficient between the two sets of scores represents the reliability coefficient.

A high correlation indicates that individuals maintain their relative positions within the group despite potential overall shifts in performance.

For example, a researcher administers a depression screening test to 100 participants. Two weeks later, they give the exact same test to the same people.

Comparing scores between Time 1 and Time 2 reveals a correlation of 0.85, indicating good test-retest reliability since the scores remained stable over time.

Factors influencing test-retest reliability :

- Memory effects: If respondents remember their answers from the first testing, it could artificially inflate the reliability coefficient.

- Time interval between testings: A short interval might lead to inflated reliability due to memory effects, while an excessively long interval increases the chance of genuine changes in the trait being measured.

- Test length and nature of test materials: These can also affect the likelihood of respondents remembering their previous answers.

- Stability of the trait being measured: If the trait itself is unstable and subject to change, test-retest reliability might be low even with a reliable measure.

Interrater Reliability

Interrater reliability assesses the consistency or agreement among judgments made by different raters or observers.

Multiple raters independently assess the same set of targets, and the consistency of their judgments is evaluated.

Adequate training equips raters with the necessary knowledge and skills to apply scoring criteria consistently, reducing systematic errors.

A high interrater reliability indicates that the raters are interchangeable and the rating protocol is reliable.

For example:

- Research: Evaluating the consistency of coding in qualitative research or assessing the agreement among raters evaluating behaviors in observational studies.

- Education: Determining the degree of agreement among teachers grading essays or other subjective assignments.

- Clinical Settings: Evaluating the consistency of diagnoses made by different clinicians based on the same patient information.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency refers to the consistency of measurement itself . It examines the degree to which different items within a test or scale are measuring the same underlying construct.

For instance, consider a test designed to assess self-esteem.

If the items within the test are internally consistent, individuals with high self-esteem should generally score highly on all or most of the items. Conversely, those with low self-esteem should consistently score lower on those same items.

While internal consistency is a necessary condition for validity, it does not guarantee it. A measure can be internally consistent but still not accurately measure the intended construct.

Methods for estimating internal consistency:

- Split-half reliability divides a test into two parts (such as odd and even number items) and correlates their scores to check consistency.

- Cronbach’s alpha (α) is the most widely used measure of internal consistency. It represents the average of all possible split-half reliability coefficients that could be computed from the test.

Ensuring Validity

- Define concepts clearly: Start with a clear and precise definition of the concepts you want to measure. This clarity will guide the selection or development of appropriate measurement instruments.

- Use established measures: Whenever possible, use well-established and validated measures that are reliable and valid in previous research. If adapting a measure from a different culture or language, carefully translate and validate it for the target population.

- Pilot test instruments: Before conducting the main study, pilot test your measurement instruments with a smaller sample to identify potential issues with wording, clarity, or response options.

- Use multiple measures (triangulation): Employing multiple methods of data collection (e.g., interviews, observations, surveys) or data analysis can enhance the validity of the findings by providing converging evidence from different sources.

- Address potential biases: Carefully consider factors that could introduce bias into the research, such as sampling methods, data collection procedures, or the researcher’s own preconceptions.

Ensuring Reliability

- Standardize procedures: Establish clear and consistent procedures for data collection, scoring, and analysis. This standardization helps minimize variability due to procedural inconsistencies.

- Train observers or raters: If using multiple raters, provide thorough training to ensure they understand the rating scales, criteria, and procedures. This training enhances interrater reliability by reducing subjective variations in judgments.

- Optimize measurement conditions: Create a controlled and consistent environment for data collection to minimize external factors that could influence responses. For example, ensure participants have adequate privacy, time, and clear instructions.

- Use reliable instruments: Select or develop measurement instruments that have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability, such as a high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Address potential issues with reverse-coded items or item heterogeneity that can affect internal consistency.

How should I report validity and reliability in my research?

- Introduction: Discuss previous research on the validity and reliability of the chosen measures, highlighting any limitations or considerations.

- Methodology: Detail the steps taken to ensure validity and reliability, including the measures used, sampling methods, data collection procedures, and steps to address potential biases.

- Results: Report the reliability coefficients obtained (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, Cohen’s Kappa) and discuss their implications for the study’s findings.

- Discussion: Critically evaluate the validity and reliability of the findings, acknowledging any limitations or areas for improvement.

validity and reliability in qualitative & quantitative research

While both qualitative and quantitative research strive to produce credible and trustworthy findings, their approaches to ensuring reliability and validity differ.

Qualitative research emphasizes the richness and depth of understanding, and quantitative research focuses on measurement precision and statistical analysis.

Qualitative Research

While traditional quantitative notions of reliability and validity may not always directly apply, qualitative researchers emphasize trustworthiness and transferability .

Credibility refers to the confidence in the truth and accuracy of the findings, often enhanced through prolonged engagement, persistent observation, and triangulation.

Transferability involves providing rich descriptions of the research context to allow readers to determine the applicability of the findings to other settings.

Confirmability is the degree to which the findings are shaped by the participants’ experiences rather than the researcher’s biases, often addressed through reflexivity and audit trails.

They focus on establishing confidence in the findings by:

- Triangulating data from multiple sources.

- Member checking , allowing participants to verify the interpretations.

- Providing thick, rich descriptions to enhance transferability to other contexts.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research typically relies more heavily on statistical measures of reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, test-retest correlations) and validity (e.g., factor analysis, correlations with criterion measures).

The goal is to demonstrate that the measures are consistent, accurate, and meaningfully related to the concepts they are intended to assess.

9 Types of Validity in Research

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Validity refers to whether or not a test or an experiment is actually doing what it is intended to do.

Validity sits upon a spectrum. For example:

- Low Validity: Most people now know that the standard IQ test does not actually measure intelligence or predict success in life.

- High Validity: By contrast, a standard pregnancy test is about 99% accurate , meaning it has very high validity and is therefore a very reliable test.

There are many ways to determine validity. Most of them are defined below.

Types of Validity

1. face validity.

Face validity refers to whether a scale “appears” to measure what it is supposed to measure. That is, do the questions seem to be logically related to the construct under study.

For example, a personality scale that measures emotional intelligence should have questions about self-awareness and empathy. It should not have questions about math or chemistry.

One common way to assess face validity is to ask a panel of experts to examine the scale and rate it’s appropriateness as a tool for measuring the construct. If the experts agree that the scale measures what it has been designed to measure, then the scale is said to have face validity.

If a scale, or a test, doesn’t have face validity, then people taking it won’t be serious.

Conbach explains it in the following way:

“When a patient loses faith in the medicine his doctor prescribes, it loses much of its power to improve his health. He may skip doses, and in the end may decide doctors cannot help him and let treatment lapse all together. For similar reasons, when selecting a test one must consider how worthwhile it will appear to the participant who takes it and other laymen who will see the results” (Cronbach, 1970, p. 182).

2. Content Validity

Content validity refers to whether a test or scale is measuring all of the components of a given construct. For example, if there are five dimensions of emotional intelligence (EQ), then a scale that measures EQ should contain questions regarding each dimension.

Similar to face validity, content validity can be assessed by asking subject matter experts (SMEs) to examine the test. If experts agree that the test includes items that assess every domain of the construct, then the test has content validity.

For example, the math portion of the SAT contains questions that require skills in many types of math: arithmetic, algebra, geometry, calculus, and many others. Since there are questions that assess each type of math, then the test has content validity.

The developer of the test could ask SMEs to rate the test’s construct validity. If the SMEs all give the test high ratings, then it has construct validity.

3. Construct Validity

Construct validity is the extent to which a measurement tool is truly assessing what it has been designed to assess.

There are two main methods of assessing construct validity: convergent and discriminant validity.

Convergent validity involves taking two tests that are supposed to measure the same construct and administering them to a sample of participants. The higher the correlation between the two tests, the stronger the construct validity.

With divergent validity, two tests that measure completely different constructs are administered to the same sample of participants. Since the tests are measuring different constructs, there should be a very low correlation between the two.

4. Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to whether or not the results of an experiment are due to the manipulation of the independent, or treatment, variables. For example, a researcher wants to examine how temperature affects willingness to help, so they have research participants wait in a room.

There are different rooms, one has the temperature set at normal, one at moderately warm, and the other at very warm.

During the next phase of the study, participants are asked to donate to a local charity before taking part in the rest of the study. The results showed that as the temperature of the room increased, donations decreased.

On the surface, it seems as though the study has internal validity: room temperature affected donations. However, even though the experiment involved three different rooms set at different temperatures, each room was a different size. The smallest room was the warmest and the normal temperature room was the largest.

Now, we don’t know if the donations were affected by room temperature or room size. So, the study has questionable internal validity.

Another way internal validity is assessed is through inter-rater reliability measures, which helps bolster both the validity and reliability of the study.

5. External Validity

External validity refers to whether the results of a study generalize to the real world or other situations. A lot of psychological studies take place in a university lab. Therefore, the setting is not very realistic.

This creates a big problem regarding external validity. Can we say that what happens in a lab would be the same thing that would happen in the real world?

For example, a study on mindfulness involves the researcher randomly assigning different research participants to use one of three mindfulness apps on their phones at home every night for 3 weeks. At the end of three weeks, their level of stress is measured with some high-tech EEG equipment.

This study has external validity because the participants used real apps and they were at home when using those apps. The apps and the home setting are realistic, so the study has external validity.

See More: Examples of External Validity

6. Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity is a method of assessing validity that involves comparing a new test with an already existing test, or an already established criterion.

For example, a newly developed math test for the SAT will need to be validated before giving it to thousands of students. So, the new version of the test is administered to a sample of college math majors along with the old version of the test.

Scores on the two tests are compared by calculating a correlation between the two. The higher the correlation, the stronger the concurrent validity of the new test.

7. Predictive Validity

Predictive validity refers to whether scores on one test are associated with performance on a given criterion. That is, can a person’s score on the test predict their performance on the criterion?

For example, an IT company needs to hire dozens of programmers for an upcoming project. But conducting interviews with hundreds of applicants is time-consuming and not very accurate at identifying skilled coders.

So, the company develops a test that contains programming problems similar to the demands of the new project. The company assesses predictive validity of the test by having their current programmers take the test and then compare their scores with their yearly performance evaluations.

The results indicate that programmers with high marks in their evaluations also did very well on the test. Therefore, the test has predictive validity.

Now, when new applicants’ take the test, the company can predict how well they will do at the job in the future. People that do well on the predictor variable test will most likely do well at the job.

8. Statistical Conclusion Validity

Statistical conclusion validity refers to whether the conclusions drawn by the authors of a study are supported by the statistical procedures.

For example, did the study apply the correct statistical analyses, were adequate sampling procedures implemented, did the study use measurement tools that are valid and reliable?

If the answers to those questions are all “yes,” then the study has statistical conclusion validity. However, if the some or all of the answers are “no,” then the conclusions of the study are called into question.

Using the wrong statistical analyses or basing the conclusions on very small sample sizes, make the results questionable. If the results are based on faulty procedures, then the conclusions cannot be accepted as valid.

9. Criterion Validity

Criterion validity is sometimes called predictive validity. It refers to how well scores on one measurement device are associated with scores on a given performance domain (the criterion).

For example, how well do SAT scores predict college GPA? Or, to what extent are measures of consumer confidence related to the economy?

An example of low criterion validity is how poorly athletic performance at the NFL’s combine actually predicts performance on the field on gameday. There are dozens of tests that the athletes go through, but about 99% of them have no association with how well they do in games.

However, nutrition and exercise are highly related to longevity (the criterion). Those constructs have criterion validity because hundreds of studies have identified that nutrition and exercise are directly linked to living a longer and healthier life.

There are so many types of validity because the measurement precision of abstract concepts is hard to discern. There can also be confusion and disagreement among experts on the definition of constructs and how they should be measured.

For these reasons, social scientists have spent considerable time developing a variety of methods to assess the validity of their measurement tools. Sometimes this reveals ways to improve techniques, and sometimes it reveals the fallacy of trying to predict the future based on faulty assessment procedures.

Cook, T.D. and Campbell, D.T. (1979) Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Cohen, R. J., & Swerdlik, M. E. (2005). Psychological testing and assessment: An introduction to tests and measurement (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cronbach, L. J. (1970). Essentials of Psychological Testing . New York: Harper & Row.

Cronbach, L. J., and Meehl, P. E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin , 52 , 281-302.

Simms, L. (2007). Classical and Modern Methods of Psychological Scale Construction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2 (1), 414 – 433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00044.x

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP0996Y

Reliability and Validity – Definitions, Types & Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

A researcher must test the collected data before making any conclusion. Every research design needs to be concerned with reliability and validity to measure the quality of the research.

What is Reliability?

Reliability refers to the consistency of the measurement. Reliability shows how trustworthy is the score of the test. If the collected data shows the same results after being tested using various methods and sample groups, the information is reliable. If your method has reliability, the results will be valid.

Example: If you weigh yourself on a weighing scale throughout the day, you’ll get the same results. These are considered reliable results obtained through repeated measures.

Example: If a teacher conducts the same math test of students and repeats it next week with the same questions. If she gets the same score, then the reliability of the test is high.

What is the Validity?

Validity refers to the accuracy of the measurement. Validity shows how a specific test is suitable for a particular situation. If the results are accurate according to the researcher’s situation, explanation, and prediction, then the research is valid.

If the method of measuring is accurate, then it’ll produce accurate results. If a method is reliable, then it’s valid. In contrast, if a method is not reliable, it’s not valid.

Example: Your weighing scale shows different results each time you weigh yourself within a day even after handling it carefully, and weighing before and after meals. Your weighing machine might be malfunctioning. It means your method had low reliability. Hence you are getting inaccurate or inconsistent results that are not valid.

Example: Suppose a questionnaire is distributed among a group of people to check the quality of a skincare product and repeated the same questionnaire with many groups. If you get the same response from various participants, it means the validity of the questionnaire and product is high as it has high reliability.

Most of the time, validity is difficult to measure even though the process of measurement is reliable. It isn’t easy to interpret the real situation.

Example: If the weighing scale shows the same result, let’s say 70 kg each time, even if your actual weight is 55 kg, then it means the weighing scale is malfunctioning. However, it was showing consistent results, but it cannot be considered as reliable. It means the method has low reliability.

Internal Vs. External Validity

One of the key features of randomised designs is that they have significantly high internal and external validity.

Internal validity is the ability to draw a causal link between your treatment and the dependent variable of interest. It means the observed changes should be due to the experiment conducted, and any external factor should not influence the variables .

Example: age, level, height, and grade.

External validity is the ability to identify and generalise your study outcomes to the population at large. The relationship between the study’s situation and the situations outside the study is considered external validity.

Also, read about Inductive vs Deductive reasoning in this article.

Looking for reliable dissertation support?

We hear you.

- Whether you want a full dissertation written or need help forming a dissertation proposal, we can help you with both.

- Get different dissertation services at ResearchProspect and score amazing grades!

Threats to Interval Validity

Threats of external validity, how to assess reliability and validity.

Reliability can be measured by comparing the consistency of the procedure and its results. There are various methods to measure validity and reliability. Reliability can be measured through various statistical methods depending on the types of validity, as explained below:

Types of Reliability

Types of validity.

As we discussed above, the reliability of the measurement alone cannot determine its validity. Validity is difficult to be measured even if the method is reliable. The following type of tests is conducted for measuring validity.

Does your Research Methodology Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of Research Methodology strong.

How to Increase Reliability?

- Use an appropriate questionnaire to measure the competency level.

- Ensure a consistent environment for participants

- Make the participants familiar with the criteria of assessment.

- Train the participants appropriately.

- Analyse the research items regularly to avoid poor performance.

How to Increase Validity?

Ensuring Validity is also not an easy job. A proper functioning method to ensure validity is given below:

- The reactivity should be minimised at the first concern.

- The Hawthorne effect should be reduced.

- The respondents should be motivated.

- The intervals between the pre-test and post-test should not be lengthy.

- Dropout rates should be avoided.

- The inter-rater reliability should be ensured.

- Control and experimental groups should be matched with each other.

How to Implement Reliability and Validity in your Thesis?

According to the experts, it is helpful if to implement the concept of reliability and Validity. Especially, in the thesis and the dissertation, these concepts are adopted much. The method for implementation given below:

Frequently Asked Questions

What is reliability and validity in research.

Reliability in research refers to the consistency and stability of measurements or findings. Validity relates to the accuracy and truthfulness of results, measuring what the study intends to. Both are crucial for trustworthy and credible research outcomes.

What is validity?

Validity in research refers to the extent to which a study accurately measures what it intends to measure. It ensures that the results are truly representative of the phenomena under investigation. Without validity, research findings may be irrelevant, misleading, or incorrect, limiting their applicability and credibility.

What is reliability?

Reliability in research refers to the consistency and stability of measurements over time. If a study is reliable, repeating the experiment or test under the same conditions should produce similar results. Without reliability, findings become unpredictable and lack dependability, potentially undermining the study’s credibility and generalisability.

What is reliability in psychology?

In psychology, reliability refers to the consistency of a measurement tool or test. A reliable psychological assessment produces stable and consistent results across different times, situations, or raters. It ensures that an instrument’s scores are not due to random error, making the findings dependable and reproducible in similar conditions.

What is test retest reliability?

Test-retest reliability assesses the consistency of measurements taken by a test over time. It involves administering the same test to the same participants at two different points in time and comparing the results. A high correlation between the scores indicates that the test produces stable and consistent results over time.

How to improve reliability of an experiment?

- Standardise procedures and instructions.

- Use consistent and precise measurement tools.

- Train observers or raters to reduce subjective judgments.

- Increase sample size to reduce random errors.

- Conduct pilot studies to refine methods.

- Repeat measurements or use multiple methods.

- Address potential sources of variability.

What is the difference between reliability and validity?

Reliability refers to the consistency and repeatability of measurements, ensuring results are stable over time. Validity indicates how well an instrument measures what it’s intended to measure, ensuring accuracy and relevance. While a test can be reliable without being valid, a valid test must inherently be reliable. Both are essential for credible research.

Are interviews reliable and valid?

Interviews can be both reliable and valid, but they are susceptible to biases. The reliability and validity depend on the design, structure, and execution of the interview. Structured interviews with standardised questions improve reliability. Validity is enhanced when questions accurately capture the intended construct and when interviewer biases are minimised.

Are IQ tests valid and reliable?

IQ tests are generally considered reliable, producing consistent scores over time. Their validity, however, is a subject of debate. While they effectively measure certain cognitive skills, whether they capture the entirety of “intelligence” or predict success in all life areas is contested. Cultural bias and over-reliance on tests are also concerns.

Are questionnaires reliable and valid?

Questionnaires can be both reliable and valid if well-designed. Reliability is achieved when they produce consistent results over time or across similar populations. Validity is ensured when questions accurately measure the intended construct. However, factors like poorly phrased questions, respondent bias, and lack of standardisation can compromise their reliability and validity.

You May Also Like

In correlational research, a researcher measures the relationship between two or more variables or sets of scores without having control over the variables.

Sampling methods are used to to draw valid conclusions about a large community, organization or group of people, but they are based on evidence and reasoning.

Thematic analysis is commonly used for qualitative data. Researchers give preference to thematic analysis when analysing audio or video transcripts.

As Featured On

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

Splash Sol LLC

- How It Works

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

In quantitative research , you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid. There are four main types of validity:

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

- Content validity : Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure?

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

Note that this article deals with types of test validity, which determine the accuracy of the actual components of a measure. If you are doing experimental research, you also need to consider internal and external validity , which deal with the experimental design and the generalisability of results.

Table of contents

Construct validity, content validity, face validity, criterion validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether a measurement tool really represents the thing we are interested in measuring. It’s central to establishing the overall validity of a method.

What is a construct?

A construct refers to a concept or characteristic that can’t be directly observed but can be measured by observing other indicators that are associated with it.

Constructs can be characteristics of individuals, such as intelligence, obesity, job satisfaction, or depression; they can also be broader concepts applied to organisations or social groups, such as gender equality, corporate social responsibility, or freedom of speech.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity is about ensuring that the method of measurement matches the construct you want to measure. If you develop a questionnaire to diagnose depression, you need to know: does the questionnaire really measure the construct of depression? Or is it actually measuring the respondent’s mood, self-esteem, or some other construct?

To achieve construct validity, you have to ensure that your indicators and measurements are carefully developed based on relevant existing knowledge. The questionnaire must include only relevant questions that measure known indicators of depression.

The other types of validity described below can all be considered as forms of evidence for construct validity.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Content validity assesses whether a test is representative of all aspects of the construct.

To produce valid results, the content of a test, survey, or measurement method must cover all relevant parts of the subject it aims to measure. If some aspects are missing from the measurement (or if irrelevant aspects are included), the validity is threatened.

Face validity considers how suitable the content of a test seems to be on the surface. It’s similar to content validity, but face validity is a more informal and subjective assessment.

As face validity is a subjective measure, it’s often considered the weakest form of validity. However, it can be useful in the initial stages of developing a method.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test can predict a concrete outcome, or how well the results of your test approximate the results of another test.

What is a criterion variable?

A criterion variable is an established and effective measurement that is widely considered valid, sometimes referred to as a ‘gold standard’ measurement. Criterion variables can be very difficult to find.

What is criterion validity?

To evaluate criterion validity, you calculate the correlation between the results of your measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. If there is a high correlation, this gives a good indication that your test is measuring what it intends to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 November 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/validity-types/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test). On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more ...

Validity and Reliability in Quantitative Research. ... have been provided regarding the main methods used in the evaluation of validity and reliability with examples taken from the literature. ...

Research Validity. Research validity is a critical concept in academic research, referring to the degree to which a study accurately measures what it intends to measure. It assesses the credibility of research results, determining whether the conclusions drawn from a study genuinely reflect the reality of the situation or variables being studied.

Validity. Validity is defined as the extent to which a concept is accurately measured in a quantitative study. For example, a survey designed to explore depression but which actually measures anxiety would not be considered valid. The second measure of quality in a quantitative study is reliability, or the accuracy of an instrument.In other words, the extent to which a research instrument ...

the studies. In quantitative research, this is achieved through measurement of the validity and reliability.1 Validity Validity is defined as the extent to which a concept is accurately measured in a quantitative study. For example, a survey designed to explore depression but which actually measures anxiety would not be consid-ered valid.

Validity in research refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of measurements. It examines whether a research instrument or method effectively measures what it claims to measure. ... Quantitative validity can be assessed through various forms, such as content validity (expert review), criterion validity ... For example: Research: ...

Types of Validity 1. Face Validity. Face validity refers to whether a scale "appears" to measure what it is supposed to measure. That is, do the questions seem to be logically related to the construct under study.. For example, a personality scale that measures emotional intelligence should have questions about self-awareness and empathy. It should not have questions about math or chemistry.

It's important to consider reliability and validity when you are creating your research design, planning your methods, and writing up your results, especially in quantitative research. Failing to do so can lead to several types of research bias and seriously affect your work.

Example; Content validity: It shows whether all the aspects of the test/measurement are covered. A language test is designed to measure the writing and reading skills, listening, and speaking skills. It indicates that a test has high content validity. Face validity: It is about the validity of the appearance of a test or procedure of the test.

In quantitative research, you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements. Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid.