An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research: Articulating Questions, Generating Hypotheses, and Choosing Study Designs

Mary p tully.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address correspondence to: Dr Mary P Tully, Manchester Pharmacy School, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PT UK, e-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

Articulating a clear and concise research question is fundamental to conducting a robust and useful research study. Although “getting stuck into” the data collection is the exciting part of research, this preparation stage is crucial. Clear and concise research questions are needed for a number of reasons. Initially, they are needed to enable you to search the literature effectively. They will allow you to write clear aims and generate hypotheses. They will also ensure that you can select the most appropriate research design for your study.

This paper begins by describing the process of articulating clear and concise research questions, assuming that you have minimal experience. It then describes how to choose research questions that should be answered and how to generate study aims and hypotheses from your questions. Finally, it describes briefly how your question will help you to decide on the research design and methods best suited to answering it.

TURNING CURIOSITY INTO QUESTIONS

A research question has been described as “the uncertainty that the investigator wants to resolve by performing her study” 1 or “a logical statement that progresses from what is known or believed to be true to that which is unknown and requires validation”. 2 Developing your question usually starts with having some general ideas about the areas within which you want to do your research. These might flow from your clinical work, for example. You might be interested in finding ways to improve the pharmaceutical care of patients on your wards. Alternatively, you might be interested in identifying the best antihypertensive agent for a particular subgroup of patients. Lipowski 2 described in detail how work as a practising pharmacist can be used to great advantage to generate interesting research questions and hence useful research studies. Ideas could come from questioning received wisdom within your clinical area or the rationale behind quick fixes or workarounds, or from wanting to improve the quality, safety, or efficiency of working practice.

Alternatively, your ideas could come from searching the literature to answer a query from a colleague. Perhaps you could not find a published answer to the question you were asked, and so you want to conduct some research yourself. However, just searching the literature to generate questions is not to be recommended for novices—the volume of material can feel totally overwhelming.

Use a research notebook, where you regularly write ideas for research questions as you think of them during your clinical practice or after reading other research papers. It has been said that the best way to have a great idea is to have lots of ideas and then choose the best. The same would apply to research questions!

When you first identify your area of research interest, it is likely to be either too narrow or too broad. Narrow questions (such as “How is drug X prescribed for patients with condition Y in my hospital?”) are usually of limited interest to anyone other than the researcher. Broad questions (such as “How can pharmacists provide better patient care?”) must be broken down into smaller, more manageable questions. If you are interested in how pharmacists can provide better care, for example, you might start to narrow that topic down to how pharmacists can provide better care for one condition (such as affective disorders) for a particular subgroup of patients (such as teenagers). Then you could focus it even further by considering a specific disorder (depression) and a particular type of service that pharmacists could provide (improving patient adherence). At this stage, you could write your research question as, for example, “What role, if any, can pharmacists play in improving adherence to fluoxetine used for depression in teenagers?”

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Being able to consider the type of research question that you have generated is particularly useful when deciding what research methods to use. There are 3 broad categories of question: descriptive, relational, and causal.

Descriptive

One of the most basic types of question is designed to ask systematically whether a phenomenon exists. For example, we could ask “Do pharmacists ‘care’ when they deliver pharmaceutical care?” This research would initially define the key terms (i.e., describing what “pharmaceutical care” and “care” are), and then the study would set out to look for the existence of care at the same time as pharmaceutical care was being delivered.

When you know that a phenomenon exists, you can then ask description and/or classification questions. The answers to these types of questions involve describing the characteristics of the phenomenon or creating typologies of variable subtypes. In the study above, for example, you could investigate the characteristics of the “care” that pharmacists provide. Classifications usually use mutually exclusive categories, so that various subtypes of the variable will have an unambiguous category to which they can be assigned. For example, a question could be asked as to “what is a pharmacist intervention” and a definition and classification system developed for use in further research.

When seeking further detail about your phenomenon, you might ask questions about its composition. These questions necessitate deconstructing a phenomenon (such as a behaviour) into its component parts. Within hospital pharmacy practice, you might be interested in asking questions about the composition of a new behavioural intervention to improve patient adherence, for example, “What is the detailed process that the pharmacist implicitly follows during delivery of this new intervention?”

After you have described your phenomena, you may then be interested in asking questions about the relationships between several phenomena. If you work on a renal ward, for example, you may be interested in looking at the relationship between hemoglobin levels and renal function, so your question would look something like this: “Are hemoglobin levels related to level of renal function?” Alternatively, you may have a categorical variable such as grade of doctor and be interested in the differences between them with regard to prescribing errors, so your research question would be “Do junior doctors make more prescribing errors than senior doctors?” Relational questions could also be asked within qualitative research, where a detailed understanding of the nature of the relationship between, for example, the gender and career aspirations of clinical pharmacists could be sought.

Once you have described your phenomena and have identified a relationship between them, you could ask about the causes of that relationship. You may be interested to know whether an intervention or some other activity has caused a change in your variable, and your research question would be about causality. For example, you may be interested in asking, “Does captopril treatment reduce blood pressure?” Generally, however, if you ask a causality question about a medication or any other health care intervention, it ought to be rephrased as a causality–comparative question. Without comparing what happens in the presence of an intervention with what happens in the absence of the intervention, it is impossible to attribute causality to the intervention. Although a causality question would usually be answered using a comparative research design, asking a causality–comparative question makes the research design much more explicit. So the above question could be rephrased as, “Is captopril better than placebo at reducing blood pressure?”

The acronym PICO has been used to describe the components of well-crafted causality–comparative research questions. 3 The letters in this acronym stand for Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. They remind the researcher that the research question should specify the type of participant to be recruited, the type of exposure involved, the type of control group with which participants are to be compared, and the type of outcome to be measured. Using the PICO approach, the above research question could be written as “Does captopril [ intervention ] decrease rates of cardiovascular events [ outcome ] in patients with essential hypertension [ population ] compared with patients receiving no treatment [ comparison ]?”

DECIDING WHETHER TO ANSWER A RESEARCH QUESTION

Just because a question can be asked does not mean that it needs to be answered. Not all research questions deserve to have time spent on them. One useful set of criteria is to ask whether your research question is feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. 1 The need for research to be ethical will be covered in a later paper in the series, so is not discussed here. The literature review is crucial to finding out whether the research question fulfils the remaining 4 criteria.

Conducting a comprehensive literature review will allow you to find out what is already known about the subject and any gaps that need further exploration. You may find that your research question has already been answered. However, that does not mean that you should abandon the question altogether. It may be necessary to confirm those findings using an alternative method or to translate them to another setting. If your research question has no novelty, however, and is not interesting or relevant to your peers or potential funders, you are probably better finding an alternative.

The literature will also help you learn about the research designs and methods that have been used previously and hence to decide whether your potential study is feasible. As a novice researcher, it is particularly important to ask if your planned study is feasible for you to conduct. Do you or your collaborators have the necessary technical expertise? Do you have the other resources that will be needed? If you are just starting out with research, it is likely that you will have a limited budget, in terms of both time and money. Therefore, even if the question is novel, interesting, and relevant, it may not be one that is feasible for you to answer.

GENERATING AIMS AND HYPOTHESES

All research studies should have at least one research question, and they should also have at least one aim. As a rule of thumb, a small research study should not have more than 2 aims as an absolute maximum. The aim of the study is a broad statement of intention and aspiration; it is the overall goal that you intend to achieve. The wording of this broad statement of intent is derived from the research question. If it is a descriptive research question, the aim will be, for example, “to investigate” or “to explore”. If it is a relational research question, then the aim should state the phenomena being correlated, such as “to ascertain the impact of gender on career aspirations”. If it is a causal research question, then the aim should include the direction of the relationship being tested, such as “to investigate whether captopril decreases rates of cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension, relative to patients receiving no treatment”.

The hypothesis is a tentative prediction of the nature and direction of relationships between sets of data, phrased as a declarative statement. Therefore, hypotheses are really only required for studies that address relational or causal research questions. For the study above, the hypothesis being tested would be “Captopril decreases rates of cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension, relative to patients receiving no treatment”. Studies that seek to answer descriptive research questions do not test hypotheses, but they can be used for hypothesis generation. Those hypotheses would then be tested in subsequent studies.

CHOOSING THE STUDY DESIGN

The research question is paramount in deciding what research design and methods you are going to use. There are no inherently bad research designs. The rightness or wrongness of the decision about the research design is based simply on whether it is suitable for answering the research question that you have posed.

It is possible to select completely the wrong research design to answer a specific question. For example, you may want to answer one of the research questions outlined above: “Do pharmacists ‘care’ when they deliver pharmaceutical care?” Although a randomized controlled study is considered by many as a “gold standard” research design, such a study would just not be capable of generating data to answer the question posed. Similarly, if your question was, “Is captopril better than placebo at reducing blood pressure?”, conducting a series of in-depth qualitative interviews would be equally incapable of generating the necessary data. However, if these designs are swapped around, we have 2 combinations (pharmaceutical care investigated using interviews; captopril investigated using a randomized controlled study) that are more likely to produce robust answers to the questions.

The language of the research question can be helpful in deciding what research design and methods to use. Subsequent papers in this series will cover these topics in detail. For example, if the question starts with “how many” or “how often”, it is probably a descriptive question to assess the prevalence or incidence of a phenomenon. An epidemiological research design would be appropriate, perhaps using a postal survey or structured interviews to collect the data. If the question starts with “why” or “how”, then it is a descriptive question to gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon. A qualitative research design, using in-depth interviews or focus groups, would collect the data needed. Finally, the term “what is the impact of” suggests a causal question, which would require comparison of data collected with and without the intervention (i.e., a before–after or randomized controlled study).

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has briefly outlined how to articulate research questions, formulate your aims, and choose your research methods. It is crucial to realize that articulating a good research question involves considerable iteration through the stages described above. It is very common that the first research question generated bears little resemblance to the final question used in the study. The language is changed several times, for example, because the first question turned out not to be feasible and the second question was a descriptive question when what was really wanted was a causality question. The books listed in the “Further Reading” section provide greater detail on the material described here, as well as a wealth of other information to ensure that your first foray into conducting research is successful.

This article is the second in the CJHP Research Primer Series, an initiative of the CJHP Editorial Board and the CSHP Research Committee. The planned 2-year series is intended to appeal to relatively inexperienced researchers, with the goal of building research capacity among practising pharmacists. The articles, presenting simple but rigorous guidance to encourage and support novice researchers, are being solicited from authors with appropriate expertise.

Previous article in this series:

Bond CM. The research jigsaw: how to get started. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(1):28–30.

Competing interests: Mary Tully has received personal fees from the UK Renal Pharmacy Group to present a conference workshop on writing research questions and nonfinancial support (in the form of travel and accommodation) from the Dubai International Pharmaceuticals and Technologies Conference and Exhibition (DUPHAT) to present a workshop on conducting pharmacy practice research.

- 1. Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W, Grady D, Newman T. Designing clinical research. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Lipowski EE. Developing great research questions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(17):1667–70. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070276. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Further Reading

- Cresswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. London (UK): Sage; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: how to do clinical practice research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar R. Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners. 3rd ed. London (UK): Sage; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith FJ. Conducting your pharmacy practice research project. London (UK): Pharmaceutical Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (592.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Hypothesis: How to Write it, Types, and Examples

Any research begins with a research question and a research hypothesis . A research question alone may not suffice to design the experiment(s) needed to answer it. A hypothesis is central to the scientific method. But what is a hypothesis ? A hypothesis is a testable statement that proposes a possible explanation to a phenomenon, and it may include a prediction. Next, you may ask what is a research hypothesis ? Simply put, a research hypothesis is a prediction or educated guess about the relationship between the variables that you want to investigate.

It is important to be thorough when developing your research hypothesis. Shortcomings in the framing of a hypothesis can affect the study design and the results. A better understanding of the research hypothesis definition and characteristics of a good hypothesis will make it easier for you to develop your own hypothesis for your research. Let’s dive in to know more about the types of research hypothesis , how to write a research hypothesis , and some research hypothesis examples .

Table of Contents

What is a hypothesis ?

A hypothesis is based on the existing body of knowledge in a study area. Framed before the data are collected, a hypothesis states the tentative relationship between independent and dependent variables, along with a prediction of the outcome.

What is a research hypothesis ?

Young researchers starting out their journey are usually brimming with questions like “ What is a hypothesis ?” “ What is a research hypothesis ?” “How can I write a good research hypothesis ?”

A research hypothesis is a statement that proposes a possible explanation for an observable phenomenon or pattern. It guides the direction of a study and predicts the outcome of the investigation. A research hypothesis is testable, i.e., it can be supported or disproven through experimentation or observation.

Characteristics of a good hypothesis

Here are the characteristics of a good hypothesis :

- Clearly formulated and free of language errors and ambiguity

- Concise and not unnecessarily verbose

- Has clearly defined variables

- Testable and stated in a way that allows for it to be disproven

- Can be tested using a research design that is feasible, ethical, and practical

- Specific and relevant to the research problem

- Rooted in a thorough literature search

- Can generate new knowledge or understanding.

How to create an effective research hypothesis

A study begins with the formulation of a research question. A researcher then performs background research. This background information forms the basis for building a good research hypothesis . The researcher then performs experiments, collects, and analyzes the data, interprets the findings, and ultimately, determines if the findings support or negate the original hypothesis.

Let’s look at each step for creating an effective, testable, and good research hypothesis :

- Identify a research problem or question: Start by identifying a specific research problem.

- Review the literature: Conduct an in-depth review of the existing literature related to the research problem to grasp the current knowledge and gaps in the field.

- Formulate a clear and testable hypothesis : Based on the research question, use existing knowledge to form a clear and testable hypothesis . The hypothesis should state a predicted relationship between two or more variables that can be measured and manipulated. Improve the original draft till it is clear and meaningful.

- State the null hypothesis: The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between the variables you are studying.

- Define the population and sample: Clearly define the population you are studying and the sample you will be using for your research.

- Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis: Select appropriate research methods, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies, which will allow you to test your research hypothesis .

Remember that creating a research hypothesis is an iterative process, i.e., you might have to revise it based on the data you collect. You may need to test and reject several hypotheses before answering the research problem.

How to write a research hypothesis

When you start writing a research hypothesis , you use an “if–then” statement format, which states the predicted relationship between two or more variables. Clearly identify the independent variables (the variables being changed) and the dependent variables (the variables being measured), as well as the population you are studying. Review and revise your hypothesis as needed.

An example of a research hypothesis in this format is as follows:

“ If [athletes] follow [cold water showers daily], then their [endurance] increases.”

Population: athletes

Independent variable: daily cold water showers

Dependent variable: endurance

You may have understood the characteristics of a good hypothesis . But note that a research hypothesis is not always confirmed; a researcher should be prepared to accept or reject the hypothesis based on the study findings.

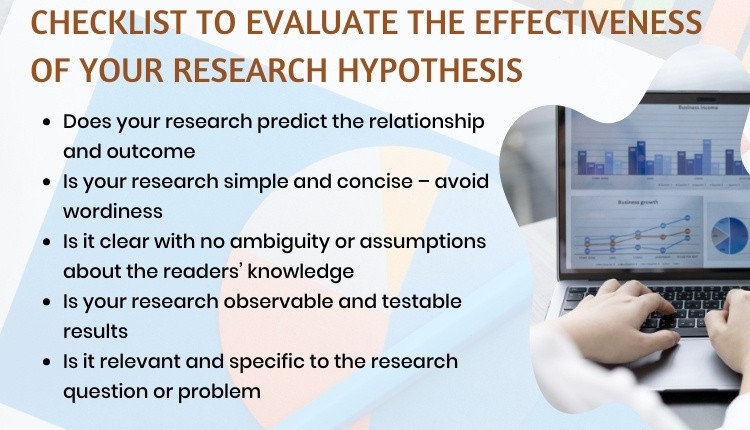

Research hypothesis checklist

Following from above, here is a 10-point checklist for a good research hypothesis :

- Testable: A research hypothesis should be able to be tested via experimentation or observation.

- Specific: A research hypothesis should clearly state the relationship between the variables being studied.

- Based on prior research: A research hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and previous research in the field.

- Falsifiable: A research hypothesis should be able to be disproven through testing.

- Clear and concise: A research hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner.

- Logical: A research hypothesis should be logical and consistent with current understanding of the subject.

- Relevant: A research hypothesis should be relevant to the research question and objectives.

- Feasible: A research hypothesis should be feasible to test within the scope of the study.

- Reflects the population: A research hypothesis should consider the population or sample being studied.

- Uncomplicated: A good research hypothesis is written in a way that is easy for the target audience to understand.

By following this research hypothesis checklist , you will be able to create a research hypothesis that is strong, well-constructed, and more likely to yield meaningful results.

Types of research hypothesis

Different types of research hypothesis are used in scientific research:

1. Null hypothesis:

A null hypothesis states that there is no change in the dependent variable due to changes to the independent variable. This means that the results are due to chance and are not significant. A null hypothesis is denoted as H0 and is stated as the opposite of what the alternative hypothesis states.

Example: “ The newly identified virus is not zoonotic .”

2. Alternative hypothesis:

This states that there is a significant difference or relationship between the variables being studied. It is denoted as H1 or Ha and is usually accepted or rejected in favor of the null hypothesis.

Example: “ The newly identified virus is zoonotic .”

3. Directional hypothesis :

This specifies the direction of the relationship or difference between variables; therefore, it tends to use terms like increase, decrease, positive, negative, more, or less.

Example: “ The inclusion of intervention X decreases infant mortality compared to the original treatment .”

4. Non-directional hypothesis:

While it does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables, a non-directional hypothesis states the existence of a relationship or difference between variables but not the direction, nature, or magnitude of the relationship. A non-directional hypothesis may be used when there is no underlying theory or when findings contradict previous research.

Example, “ Cats and dogs differ in the amount of affection they express .”

5. Simple hypothesis :

A simple hypothesis only predicts the relationship between one independent and another independent variable.

Example: “ Applying sunscreen every day slows skin aging .”

6 . Complex hypothesis :

A complex hypothesis states the relationship or difference between two or more independent and dependent variables.

Example: “ Applying sunscreen every day slows skin aging, reduces sun burn, and reduces the chances of skin cancer .” (Here, the three dependent variables are slowing skin aging, reducing sun burn, and reducing the chances of skin cancer.)

7. Associative hypothesis:

An associative hypothesis states that a change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables.

Example: “ There is a positive association between physical activity levels and overall health .”

8 . Causal hypothesis:

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect interaction between variables.

Example: “ Long-term alcohol use causes liver damage .”

Note that some of the types of research hypothesis mentioned above might overlap. The types of hypothesis chosen will depend on the research question and the objective of the study.

Research hypothesis examples

Here are some good research hypothesis examples :

“The use of a specific type of therapy will lead to a reduction in symptoms of depression in individuals with a history of major depressive disorder.”

“Providing educational interventions on healthy eating habits will result in weight loss in overweight individuals.”

“Plants that are exposed to certain types of music will grow taller than those that are not exposed to music.”

“The use of the plant growth regulator X will lead to an increase in the number of flowers produced by plants.”

Characteristics that make a research hypothesis weak are unclear variables, unoriginality, being too general or too vague, and being untestable. A weak hypothesis leads to weak research and improper methods.

Some bad research hypothesis examples (and the reasons why they are “bad”) are as follows:

“This study will show that treatment X is better than any other treatment . ” (This statement is not testable, too broad, and does not consider other treatments that may be effective.)

“This study will prove that this type of therapy is effective for all mental disorders . ” (This statement is too broad and not testable as mental disorders are complex and different disorders may respond differently to different types of therapy.)

“Plants can communicate with each other through telepathy . ” (This statement is not testable and lacks a scientific basis.)

Importance of testable hypothesis

If a research hypothesis is not testable, the results will not prove or disprove anything meaningful. The conclusions will be vague at best. A testable hypothesis helps a researcher focus on the study outcome and understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved. A testable hypothesis helps a researcher make precise predictions based on prior research.

To be considered testable, there must be a way to prove that the hypothesis is true or false; further, the results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on research hypothesis

1. What is the difference between research question and research hypothesis ?

A research question defines the problem and helps outline the study objective(s). It is an open-ended statement that is exploratory or probing in nature. Therefore, it does not make predictions or assumptions. It helps a researcher identify what information to collect. A research hypothesis , however, is a specific, testable prediction about the relationship between variables. Accordingly, it guides the study design and data analysis approach.

2. When to reject null hypothesis ?

A null hypothesis should be rejected when the evidence from a statistical test shows that it is unlikely to be true. This happens when the test statistic (e.g., p -value) is less than the defined significance level (e.g., 0.05). Rejecting the null hypothesis does not necessarily mean that the alternative hypothesis is true; it simply means that the evidence found is not compatible with the null hypothesis.

3. How can I be sure my hypothesis is testable?

A testable hypothesis should be specific and measurable, and it should state a clear relationship between variables that can be tested with data. To ensure that your hypothesis is testable, consider the following:

- Clearly define the key variables in your hypothesis. You should be able to measure and manipulate these variables in a way that allows you to test the hypothesis.

- The hypothesis should predict a specific outcome or relationship between variables that can be measured or quantified.

- You should be able to collect the necessary data within the constraints of your study.

- It should be possible for other researchers to replicate your study, using the same methods and variables.

- Your hypothesis should be testable by using appropriate statistical analysis techniques, so you can draw conclusions, and make inferences about the population from the sample data.

- The hypothesis should be able to be disproven or rejected through the collection of data.

4. How do I revise my research hypothesis if my data does not support it?

If your data does not support your research hypothesis , you will need to revise it or develop a new one. You should examine your data carefully and identify any patterns or anomalies, re-examine your research question, and/or revisit your theory to look for any alternative explanations for your results. Based on your review of the data, literature, and theories, modify your research hypothesis to better align it with the results you obtained. Use your revised hypothesis to guide your research design and data collection. It is important to remain objective throughout the process.

5. I am performing exploratory research. Do I need to formulate a research hypothesis?

As opposed to “confirmatory” research, where a researcher has some idea about the relationship between the variables under investigation, exploratory research (or hypothesis-generating research) looks into a completely new topic about which limited information is available. Therefore, the researcher will not have any prior hypotheses. In such cases, a researcher will need to develop a post-hoc hypothesis. A post-hoc research hypothesis is generated after these results are known.

6. How is a research hypothesis different from a research question?

A research question is an inquiry about a specific topic or phenomenon, typically expressed as a question. It seeks to explore and understand a particular aspect of the research subject. In contrast, a research hypothesis is a specific statement or prediction that suggests an expected relationship between variables. It is formulated based on existing knowledge or theories and guides the research design and data analysis.

7. Can a research hypothesis change during the research process?

Yes, research hypotheses can change during the research process. As researchers collect and analyze data, new insights and information may emerge that require modification or refinement of the initial hypotheses. This can be due to unexpected findings, limitations in the original hypotheses, or the need to explore additional dimensions of the research topic. Flexibility is crucial in research, allowing for adaptation and adjustment of hypotheses to align with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

8. How many hypotheses should be included in a research study?

The number of research hypotheses in a research study varies depending on the nature and scope of the research. It is not necessary to have multiple hypotheses in every study. Some studies may have only one primary hypothesis, while others may have several related hypotheses. The number of hypotheses should be determined based on the research objectives, research questions, and the complexity of the research topic. It is important to ensure that the hypotheses are focused, testable, and directly related to the research aims.

9. Can research hypotheses be used in qualitative research?

Yes, research hypotheses can be used in qualitative research, although they are more commonly associated with quantitative research. In qualitative research, hypotheses may be formulated as tentative or exploratory statements that guide the investigation. Instead of testing hypotheses through statistical analysis, qualitative researchers may use the hypotheses to guide data collection and analysis, seeking to uncover patterns, themes, or relationships within the qualitative data. The emphasis in qualitative research is often on generating insights and understanding rather than confirming or rejecting specific research hypotheses through statistical testing.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Paperpal Review: Key Features, Pricing Plans, and How-to-Use

How to Structure a Dissertation?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Qualitative study.

Steven Tenny ; Janelle M. Brannan ; Grace D. Brannan .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. [1] Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." [2] Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. [2] One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. [3] Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. [4] While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design originates in social and cultural anthropology and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. [2] Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. [2] That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc, through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded theory

Grounded Theory is the "generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior." [5] Unlike quantitative research, which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and, therefore, lends itself to research aimed at social interactions or experiences. [3] [2] In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the "study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular.” [5] At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are pretty similar, but the differences can be seen upon careful examination. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the individual's perspective. [2] Phenomenology is essentially looking into the "lived experiences" of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way from their perspective. Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources. In contrast, Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomenon from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called a "thick" or "rich" description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of "thick" description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, hoping to create a cohesive story or narrative. [2] While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be "opportunities for innovation." [2]

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards underpinning different research approaches. Essentially, research paradigms are the "worldviews" that inform research. [4] It is valuable for qualitative and quantitative researchers to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontologies and epistemologies. Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality,” whereas epistemology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of knowledge" that inform researchers' work. [2] It is essential to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a complete understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, researchers must understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist versus postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we must discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social and natural sciences. [4] Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in their research. It stems from positivist ontology, that there is an objective reality that exists that is wholly independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained, but could be approximated. [4] Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world,” and therefore, postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. [4] An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are also constructivist, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but instead that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. "Constructivism contends that individuals' views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality.” [6] constructivist thought focuses on how "reality" is not a fixed certainty and how experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike positivist views, that there is not necessarily an "objective"reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and our world are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.” [4]

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have. It can even change the role of the researchers. [2] For example, is the researcher an "objective" observer, such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the study undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research and reflect on their positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection: [7]

- Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale for being the most informative.

- Criterion sampling selection based on pre-identified factors.

- Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

- Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

- Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

- Typical case sampling selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques, including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic, and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one-on-one and appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be participant-observers to share the experiences of the subject or non-participants or detached observers.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or the participants' environment, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed, which may then be coded manually or using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo. [8] [9] [10]

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. [11] Results could also be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

The healthcare team can use two reporting standards to standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. [12] The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a more comprehensive range of qualitative research. [13]

Applications

Many times, a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis, which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data to better understand what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative techniques can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research, researchers can explore poorly studied subjects with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual actions, and social science research.

An excellent qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected that will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because, often, the information sought is not well categorized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of why teens start to smoke and factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered "cool," and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current nonsmokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the survey results to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the primary factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the primary factor that contributed to teens starting smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on keeping teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly in the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure to smoke. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and sees that the smokers tend to hang out in a shady, overgrown area of the park. The researcher notes that smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park, where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk populations their perceptions of the changes and what factors are still at play, and quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community and the incidence of new teen smokers, among others. [14] [15]

Qualitative research functions as a standalone research design or combined with quantitative research to enhance our understanding of the world. Qualitative research uses techniques including structured and unstructured interviews, focus groups, and participant observation not only to help generate hypotheses that can be more rigorously tested with quantitative research but also to help researchers delve deeper into the quantitative research numbers, understand what they mean, and understand what the implications are. Qualitative research allows researchers to understand what is going on, especially when things are not easily categorized. [16]

- Issues of Concern

As discussed in the sections above, quantitative and qualitative work differ in many ways, including the evaluation criteria. There are four well-established criteria for evaluating quantitative data: internal validity, external validity, reliability, and objectivity. Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability are the correlating concepts in qualitative research. [4] [11] The corresponding quantitative and qualitative concepts can be seen below, with the quantitative concept on the left and the qualitative concept on the right:

- Internal validity: Credibility

- External validity: Transferability

- Reliability: Dependability

- Objectivity: Confirmability

In conducting qualitative research, ensuring these concepts are satisfied and well thought out can mitigate potential issues from arising. For example, just as a researcher will ensure that their quantitative study is internally valid, qualitative researchers should ensure that their work has credibility.

Indicators such as triangulation and peer examination can help evaluate the credibility of qualitative work.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple data collection methods to increase the likelihood of getting a reliable and accurate result. In our above magic example, the result would be more reliable if we interviewed the magician, backstage hand, and the person who "vanished." In qualitative research, triangulation can include telephone surveys, in-person surveys, focus groups, and interviews and surveying an adequate cross-section of the target demographic.

- Peer examination: A peer can review results to ensure the data is consistent with the findings.

A "thick" or "rich" description can be used to evaluate the transferability of qualitative research, whereas an indicator such as an audit trail might help evaluate the dependability and confirmability.

- Thick or rich description: This is a detailed and thorough description of details, the setting, and quotes from participants in the research. [5] Thick descriptions will include a detailed explanation of how the study was conducted. Thick descriptions are detailed enough to allow readers to draw conclusions and interpret the data, which can help with transferability and replicability.

- Audit trail: An audit trail provides a documented set of steps of how the participants were selected and the data was collected. The original information records should also be kept (eg, surveys, notes, recordings).

One issue of concern that qualitative researchers should consider is observation bias. Here are a few examples:

- Hawthorne effect: The effect is the change in participant behavior when they know they are being observed. Suppose a researcher wanted to identify factors that contribute to employee theft and tell the employees they will watch them to see what factors affect employee theft. In that case, one would suspect employee behavior would change when they know they are being protected.

- Observer-expectancy effect: Some participants change their behavior or responses to satisfy the researcher's desired effect. This happens unconsciously for the participant, so it is essential to eliminate or limit the transmission of the researcher's views.

- Artificial scenario effect: Some qualitative research occurs in contrived scenarios with preset goals. In such situations, the information may not be accurate because of the artificial nature of the scenario. The preset goals may limit the qualitative information obtained.

- Clinical Significance

Qualitative or quantitative research helps healthcare providers understand patients and the impact and challenges of the care they deliver. Qualitative research provides an opportunity to generate and refine hypotheses and delve deeper into the data generated by quantitative research. Qualitative research is not an island apart from quantitative research but an integral part of research methods to understand the world around us. [17]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Qualitative research is essential for all healthcare team members as all are affected by qualitative research. Qualitative research may help develop a theory or a model for health research that can be further explored by quantitative research. Much of the qualitative research data acquisition is completed by numerous team members, including social workers, scientists, nurses, etc. Within each area of the medical field, there is copious ongoing qualitative research, including physician-patient interactions, nursing-patient interactions, patient-environment interactions, healthcare team function, patient information delivery, etc.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Steven Tenny declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Janelle Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Grace Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Tenny S, Brannan JM, Brannan GD. Qualitative Study. [Updated 2022 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022] Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1; 2(2022). Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Macromolecular crowding: chemistry and physics meet biology (Ascona, Switzerland, 10-14 June 2012). [Phys Biol. 2013] Macromolecular crowding: chemistry and physics meet biology (Ascona, Switzerland, 10-14 June 2012). Foffi G, Pastore A, Piazza F, Temussi PA. Phys Biol. 2013 Aug; 10(4):040301. Epub 2013 Aug 2.

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. [Early Hum Dev. 2020] The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov; 150:105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12.

- Review Invited review: Qualitative research in dairy science-A narrative review. [J Dairy Sci. 2023] Review Invited review: Qualitative research in dairy science-A narrative review. Ritter C, Koralesky KE, Saraceni J, Roche S, Vaarst M, Kelton D. J Dairy Sci. 2023 Sep; 106(9):5880-5895. Epub 2023 Jul 18.

- Review Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: a review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016] Review Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: a review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Husk K, Lovell R, Cooper C, Stahl-Timmins W, Garside R. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 21; 2016(5):CD010351. Epub 2016 May 21.

Recent Activity

- Qualitative Study - StatPearls Qualitative Study - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Craft a Strong Research Hypothesis

- 4 minute read

- 406.5K views

Table of Contents

A research hypothesis is a concise statement about the expected result of an experiment or project. In many ways, a research hypothesis represents the starting point for a scientific endeavor, as it establishes a tentative assumption that is eventually substantiated or falsified, ultimately improving our certainty about the subject investigated.

To help you with this and ease the process, in this article, we discuss the purpose of research hypotheses and list the most essential qualities of a compelling hypothesis. Let’s find out!

How to Craft a Research Hypothesis

Crafting a research hypothesis begins with a comprehensive literature review to identify a knowledge gap in your field. Once you find a question or problem, come up with a possible answer or explanation, which becomes your hypothesis. Now think about the specific methods of experimentation that can prove or disprove the hypothesis, which ultimately lead to the results of the study.

Enlisted below are some standard formats in which you can formulate a hypothesis¹ :

- A hypothesis can use the if/then format when it seeks to explore the correlation between two variables in a study primarily.

Example: If administered drug X, then patients will experience reduced fatigue from cancer treatment.

- A hypothesis can adopt when X/then Y format when it primarily aims to expose a connection between two variables

Example: When workers spend a significant portion of their waking hours in sedentary work , then they experience a greater frequency of digestive problems.

- A hypothesis can also take the form of a direct statement.

Example: Drug X and drug Y reduce the risk of cognitive decline through the same chemical pathways

What are the Features of an Effective Hypothesis?

Hypotheses in research need to satisfy specific criteria to be considered scientifically rigorous. Here are the most notable qualities of a strong hypothesis:

- Testability: Ensure the hypothesis allows you to work towards observable and testable results.

- Brevity and objectivity: Present your hypothesis as a brief statement and avoid wordiness.

- Clarity and Relevance: The hypothesis should reflect a clear idea of what we know and what we expect to find out about a phenomenon and address the significant knowledge gap relevant to a field of study.

Understanding Null and Alternative Hypotheses in Research

There are two types of hypotheses used commonly in research that aid statistical analyses. These are known as the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . A null hypothesis is a statement assumed to be factual in the initial phase of the study.

For example, if a researcher is testing the efficacy of a new drug, then the null hypothesis will posit that the drug has no benefits compared to an inactive control or placebo . Suppose the data collected through a drug trial leads a researcher to reject the null hypothesis. In that case, it is considered to substantiate the alternative hypothesis in the above example, that the new drug provides benefits compared to the placebo.

Let’s take a closer look at the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis with two more examples:

Null Hypothesis:

The rate of decline in the number of species in habitat X in the last year is the same as in the last 100 years when controlled for all factors except the recent wildfires.

In the next experiment, the researcher will experimentally reject this null hypothesis in order to confirm the following alternative hypothesis :

The rate of decline in the number of species in habitat X in the last year is different from the rate of decline in the last 100 years when controlled for all factors other than the recent wildfires.

In the pair of null and alternative hypotheses stated above, a statistical comparison of the rate of species decline over a century and the preceding year will help the research experimentally test the null hypothesis, helping to draw scientifically valid conclusions about two factors—wildfires and species decline.

We also recommend that researchers pay attention to contextual echoes and connections when writing research hypotheses. Research hypotheses are often closely linked to the introduction ² , such as the context of the study, and can similarly influence the reader’s judgment of the relevance and validity of the research hypothesis.

Seasoned experts, such as professionals at Elsevier Language Services, guide authors on how to best embed a hypothesis within an article so that it communicates relevance and credibility. Contact us if you want help in ensuring readers find your hypothesis robust and unbiased.

References

- Hypotheses – The University Writing Center. (n.d.). https://writingcenter.tamu.edu/writing-speaking-guides/hypotheses

- Shaping the research question and hypothesis. (n.d.). Students. https://students.unimelb.edu.au/academic-skills/graduate-research-services/writing-thesis-sections-part-2/shaping-the-research-question-and-hypothesis

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

How to Write an Effective Problem Statement for Your Research Paper

You may also like.

Submission 101: What format should be used for academic papers?

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.