- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Boston Massacre

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 24, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

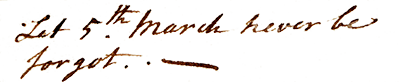

The Boston Massacre was a deadly riot that occurred on March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston. It began as a street brawl between American colonists and a lone British soldier, but quickly escalated to a chaotic, bloody slaughter. The conflict energized anti-British sentiment and paved the way for the American Revolution.

Why Did the Boston Massacre Happen?

Tensions ran high in Boston in early 1770. More than 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000 colonists and tried to enforce Britain’s tax laws, like the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts . American colonists rebelled against the taxes they found repressive, rallying around the cry, “no taxation without representation.”

Skirmishes between colonists and soldiers—and between patriot colonists and colonists loyal to Britain (loyalists)—were increasingly common. To protest taxes, patriots often vandalized stores selling British goods and intimidated store merchants and their customers.

On February 22, a mob of patriots attacked a known loyalist’s store. Customs officer Ebenezer Richardson lived near the store and tried to break up the rock-pelting crowd by firing his gun through the window of his home. His gunfire struck and killed an 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider and further enraged the patriots.

Several days later, a fight broke out between local workers and British soldiers. It ended without serious bloodshed but helped set the stage for the bloody incident yet to come.

How Many Died After Violence Erupted?

On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King’s money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn’t long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.

At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town—usually a warning of fire—sending a mass of male colonists into the streets. As the assault on White continued, he eventually fell and called for reinforcements.

In response to White’s plea and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King’s money, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene with several soldiers and took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House.

Worried that bloodshed was inevitable, some colonists reportedly pleaded with the soldiers to hold their fire as others dared them to shoot. Preston later reported a colonist told him the protestors planned to “carry off [White] from his post and probably murder him.”

The violence escalated, and the colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. Reports differ of exactly what happened next, but after someone supposedly said the word “fire,” a soldier fired his gun, although it’s unclear if the discharge was intentional.

Once the first shot rang out, other soldiers opened fire, killing five colonists–including Crispus Attucks , a local dockworker of mixed racial heritage–and wounding six. Among the other casualties of the Boston Massacre was Samuel Gray, a rope maker who was left with a hole the size of a fist in his head. Sailor James Caldwell was hit twice before dying, and Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr were mortally wounded.

7 Events That Enraged Colonists and Led to the American Revolution

Colonists didn't just take up arms against the British out of the blue. A series of events escalated tensions that culminated in America's war for independence.

8 Things We Know About Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks, a multiracial man who had escaped slavery, is known as the first American colonist killed in the American Revolution.

Did a Snowball Fight Start the American Revolution?

On a cold night in Boston in 1770, angry colonists pelted a lone British sentry with snowballs. The rest is history.

Boston Massacre Fueled Anti-British Views

Within hours, Preston and his soldiers were arrested and jailed and the propaganda machine was in full force on both sides of the conflict.

Preston wrote his version of the events from his jail cell for publication, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as John Hancock and Samuel Adams incited colonists to keep fighting the British. As tensions rose, British troops retreated from Boston to Fort William.

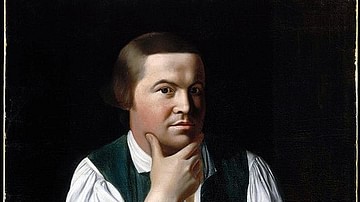

Paul Revere encouraged anti-British attitudes by etching a now-famous engraving depicting British soldiers callously murdering American colonists. It showed the British as the instigators though the colonists had started the fight.

It also portrayed the soldiers as vicious men and the colonists as gentlemen. It was later determined that Revere had copied his engraving from one made by Boston artist Henry Pelham.

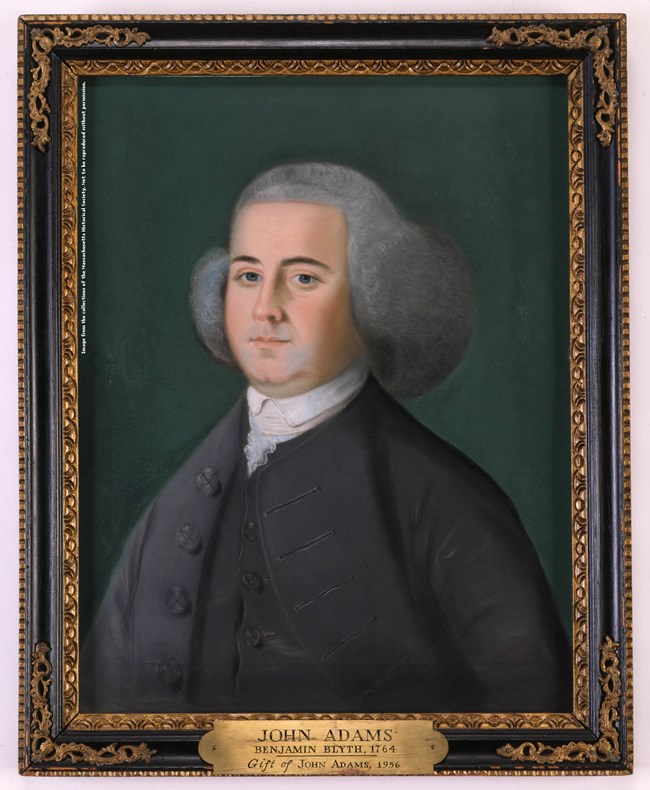

John Adams Defends the British

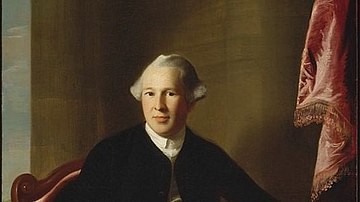

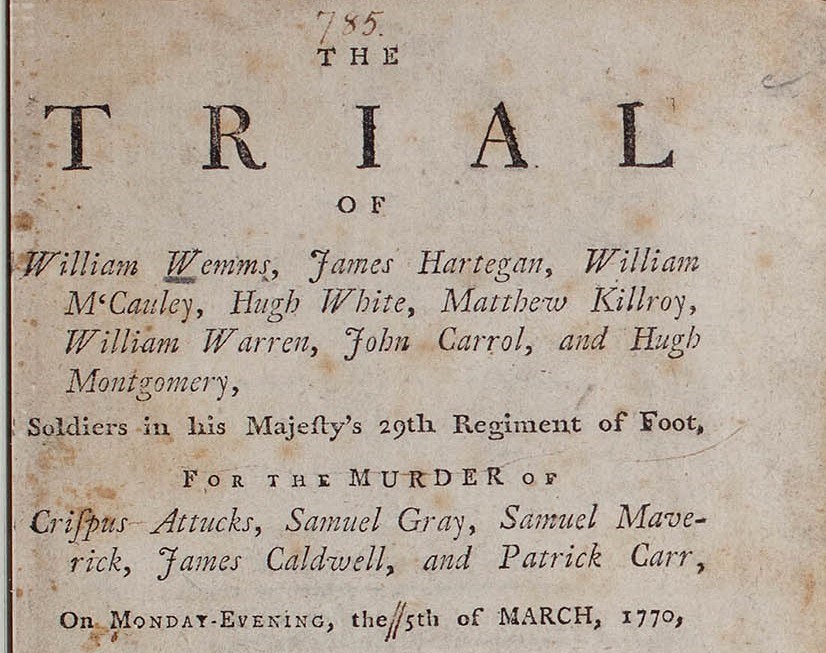

It took seven months to arraign Preston and the other soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre and bring them to trial. Ironically, it was American colonist, lawyer and future President of the United States John Adams who defended them.

Adams was no fan of the British but wanted Preston and his men to receive a fair trial. After all, the death penalty was at stake and the colonists didn’t want the British to have an excuse to even the score. Certain that impartial jurors were nonexistent in Boston, Adams convinced the judge to seat a jury of non-Bostonians.

During Preston’s trial, Adams argued that confusion that night was rampant. Eyewitnesses presented contradictory evidence on whether Preston had ordered his men to fire on the colonists.

But after witness Richard Palmes testified that, “…After the Gun went off I heard the word ‘fire!’ The Captain and I stood in front about half between the breech and muzzle of the Guns. I don’t know who gave the word to fire,” Adams argued that reasonable doubt existed; Preston was found not guilty.

The remaining soldiers claimed self-defense and were all found not guilty of murder. Two of them—Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy—were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumbs as first offenders per English law.

To Adams’ and the jury’s credit, the British soldiers received a fair trial despite the vitriol felt towards them and their country.

Aftermath of the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre had a major impact on relations between Britain and the American colonists. It further incensed colonists already weary of British rule and unfair taxation and roused them to fight for independence.

Yet perhaps Preston said it best when he wrote about the conflict and said, “None of them was a hero. The victims were troublemakers who got more than they deserved. The soldiers were professionals…who shouldn’t have panicked. The whole thing shouldn’t have happened.”

Over the next five years, the colonists continued their rebellion and staged the Boston Tea Party , formed the First Continental Congress and defended their militia arsenal at Concord against the redcoats, effectively launching the American Revolution . Today, the city of Boston has a Boston Massacre site marker at the intersection of Congress Street and State Street, a few yards from where the first shots were fired.

After the Boston Massacre. John Adams Historical Society. Boston Massacre Trial. National Park Service: National Historical Park of Massachusetts. Paul Revere’s Engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The Boston Massacre. Bostonian Society Old State House. The Boston “Massacre.” H.S.I. Historical Scene Investigation.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

The killing of Christopher Seider and the end of the rope

From mob to “massacre”.

- Aftermath and agitprop

What was the Boston Massacre?

Why did the boston massacre happen.

- What are the American colonies?

- Who established the American colonies?

- What pushed the American colonies toward independence?

Boston Massacre

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Bill of Rights Institute - The Boston Massacre

- National Park Service - Boston Massacre

- Khan Academy - The Boston Massacre

- The Ohio State University - Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective - The Boston Massacre

- Teach Democracy - The Boston Massacre

- World History Encyclopedia - Boston Massacre

- Colonial America - Boston Massacre Facts

- Alpha History - The Boston Massacre

- American Battlefield Trust - The Boston Massacre

- Public Broadcasting Service - Africans in America - The Boston Massacre

- Boston Massacre - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Boston Massacre - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The incident was the climax of growing unrest in Boston , fueled by colonists’ opposition to a series of acts passed by the British Parliament . Especially unpopular was an act that raised revenue through duties on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea. On March 5, 1770, a crowd confronted eight British soldiers in the streets of the city. As the mob insulted and threatened them, the soldiers fired their muskets, killing five colonists.

In 1767 the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts , designed to exert authority over the colonies. One of the acts placed duties on various goods, and it proved particularly unpopular in Massachusetts . Tensions began to grow, and in Boston in February 1770 a patriot mob attacked a British loyalist, who fired a gun at them, killing a boy. In the ensuing days brawls between colonists and British soldiers eventually culminated in the Boston Massacre.

Why was the Boston Massacre important?

The incident and the trials of the British soldiers, none of whom received prison sentences, were widely publicized and drew great outrage. The events contributed to the unpopularity of the British regime in much of colonial North America and helped lead to the American Revolution .

Boston Massacre , (March 5, 1770), skirmish between British troops and a crowd in Boston , Massachusetts . Widely publicized, it contributed to the unpopularity of the British regime in much of colonial North America in the years before the American Revolution .

In 1767, in an attempt to recoup the considerable treasure expended in the defense of its North American colonies during the French and Indian War (1754–63), the British Parliament enacted strict provisions for the collection of revenue duties in the colonies. Those duties were part of a series of four acts that became known as the Townshend Acts , which also were intended to assert Parliament’s authority over the colonies, in marked contrast to the policy of salutary neglect that had been practiced by the British government during the early to mid-18th century. The imposition of those duties—on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea upon their arrival in colonial ports—met with angry opposition from many colonists in Massachusetts. In addition to organized boycotts of those goods, the colonial response took the form of harassment of British officials and vandalism. Parliament answered British colonial authorities’ request for protection by dispatching the 14th and 29th regiments of the British army to Boston, where they arrived in October 1768. The presence of those troops, however, heightened the tension in an already anxious environment .

Early in 1770, with the effectiveness of the boycott uneven, colonial radicals, many of them members of the Sons of Liberty , began directing their ire against those businesses that had ignored the boycott. The radicals posted signs (large hands emblazoned with the word importer ) on the establishments of boycott-violating merchants and berated their customers. On February 22, when Ebenezer Richardson, who was known to the radicals as an informer, tried to take down one of those signs from the shop of his neighbour Theophilus Lillie, he was set upon by a group of boys. The boys drove Richardson back into his own nearby home, from which he emerged to castigate his tormentors, drawing a hail of stones that broke Richardson’s door and front window. Richardson and George Wilmont, who had come to his defense, armed themselves with muskets and accosted the boys who had entered Richardson’s backyard. Richardson fired, hitting 11-year-old Christopher Seider (or Snyder or Snider; sources differ on his last name), who died later that night. Seemingly, only the belief that Richardson would be brought to justice in court prevented the crowd from taking immediate vengeance upon him.

With tensions running high in the wake of Seider’s funeral, brawls broke out between soldiers and rope makers in Boston’s South End on March 2 and 3. On March 4 British troops searched the rope works owned by John Gray for a sergeant who was believed to have been murdered. Gray, having heard that British troops were going to attack his workers on Monday, March 5, consulted with Col. William Dalrymple, the commander of the 14th Regiment. Both men agreed to restrain those in their charge, but rumours of an imminent encounter flew.

On the morning of March 5 someone posted a handbill ostensibly from the British soldiers promising that they were determined to defend themselves. That night a crowd of Bostonians roamed the streets, their anger fueled by rumours that soldiers were preparing to cut down the so-called Liberty Tree (an elm tree in what was then South Boston from which effigies of men who had favoured the Stamp Act had been hung and on the trunk of which was a copper-plated sign that read “The Tree of Liberty”) and that a soldier had attacked an oysterman. One element of the crowd stormed the barracks of the 29th Regiment but was repulsed. Bells rang out an alarm and the crowd swelled , but the soldiers remained in their barracks, though the crowd pelted the barracks with snowballs. Meanwhile, the single sentry posted outside the Customs House became the focus of the rage for a crowd of 50–60 people. Informed of the sentry’s situation by a British sympathizer, Capt. Thomas Preston marched seven soldiers with fixed bayonets through the crowd in an attempt to rescue the sentry. Emboldened by the knowledge that the Riot Act had not been read—and that the soldiers could not fire their weapons until it had been read and then only if the crowd failed to disperse within an hour—the crowd taunted the soldiers and dared them to shoot (“provoking them to it by the most opprobrious language,” according to Thomas Gage , commander in chief of the British army in America). Meanwhile, they pelted the troops with snow, ice, and oyster shells.

In the confusion, one of the soldiers, who were then trapped by the patriot mob near the Customs House, was jostled and, in fear, discharged his musket . Other soldiers, thinking they had heard the command to fire, followed suit. Three crowd members—including Crispus Attucks , a Black sailor who likely was formerly enslaved—were shot and died almost immediately. Two of the eight others who were wounded died later. Hoping to prevent further violence, Lieut. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson , who had been summoned to the scene and arrived shortly after the shooting had taken place, ordered Preston and his contingent back to their barracks, where other troops had their guns trained on the crowd. Hutchinson then made his way to the balcony of the Old State House, from which he ordered the other troops back into the barracks and promised the crowd that justice would be done, calming the growing mob and bringing an uneasy peace to the city.

Everything you've ever wanted to know about the American Revolution

Boston Massacre of 1770 | Summary, Causes, Effects, Facts

About the author.

Edward A. St. Germain created AmericanRevolution.org in 1996. He was an avid historian with a keen interest in the Revolutionary War and American culture and society in the 18th century. On this website, he created and collated a huge collection of articles, images, and other media pertaining to the American Revolution. Edward was also a Vietnam veteran, and his investigative skills led to a career as a private detective in later life.

The Boston Massacre was an incident that occurred on March 5, 1770, where a group of British soldiers fired into a crowd of civilians on King Street in Boston.

In this article, we’ve explained what happened during the Boston Massacre, and what caused it. We’ve also explained what happened in the aftermath, and provided some interesting facts about the event.

On the evening of March 5, 1770, two British soldiers guarding the Boston Custom House got into an argument with a local apprentice, leading one of the soldiers to hit the boy over the head with his musket.

A colonist who witnessed the assault began arguing with the soldiers, and gradually a mob formed, surrounding the British troops on the steps of the Custom House.

The crowd grew to over 300 people over the course of a few hours, and the British called for backup. They eventually ended up with nine men, including Captain Thomas Preston, who arrived from the nearby barracks.

The crowd threw snowballs, stones, and other projectiles, and hurled insults at the soldiers. Eventually, the soldiers panicked, and let out a volley of shots.

Three Americans were killed instantly, and another two would later die in hospital. Eight further civilians were injured.

In the late 1760s, tension was building between American colonists and the British government.

The British implemented the Stamp Act in 1765 , creating a new direct tax on colonial consumers. This led to widespread protests – colonists were outraged, as they did not feel the British had the right to tax them without their consent. Ultimately, the British were forced to repeal the Stamp Act a year later.

To the colonists’ dismay, the British immediately began implementing new laws to try and increase taxation revenue, in part by cracking down on illegal smuggling.

In 1767 and 1768, the British implemented the Townshend Acts . The Acts gave customers officials more power to search colonial ships and seize goods, and made it so that people accused of smuggling would be tried by a judge, rather than a colonial jury, increasing the likelihood of a conviction.

The acts also reduced the tax on tea purchased from the British East India Company, and placed new taxes on certain goods traded by colonial merchants.

The Townshend Acts caused widespread discontent, especially in Boston. At the time, Boston was a major trading hub, meaning it was home to large numbers of colonial merchants, sailors, and traders, who relied on being able to conduct commerce (including illegal smuggling) to make a living.

Boston residents were also upset by the presence of large numbers of British troops stationed in the city, who had arrived in 1768 to deal with protests, vandalism, and violence caused by the Townshend Acts.

Officially, under the British Quartering Act of 1765 , Massachusetts was supposed to provide housing and other supplies to British troops in their colony, which further upset the colonists.

Essentially, the Boston Massacre occurred because the people of Boston were extremely upset with the British authorities in the late 1760s and early 1770s. They felt that the British were threatening their livelihoods, freedom, and the autonomy of their colony.

Aftermath and effects

Immediately after the Boston Massacre, there was a fight to control the narrative about what happened.

The Patriot side labeled the event “The Boston Massacre” and portrayed it as a senseless killing of unarmed civilians, orchestrated by the British Army.

Paul Revere produced a famous propaganda engraving of the incident, which is shown below.

This engraving is not factually accurate – the British did not open fire in an orderly fashion as the image suggests, and they were not given the order to fire as the scene depicts.

The British called the event “The Incident on King Street” and tried to quell tensions in Boston. British troops were removed from the city, and those involved in the massacre were arrested and charged with murder.

For the Patriot side, propaganda about the Boston Massacre was very effective. The event caused an increase in colonial unity against British rule, and was used to demonstrate that the British government were tyrants, as hardline Patriots argued.

The trials for the soldiers were held in a colonial court in Massachusetts. The colonial government wanted to avoid a further escalation in tension with the British, so care was taken to ensure a fair trial.

John Adams , a leading Patriot, was brought in to defend the soldiers to avoid any accusations of bias from Bostonians.

The trial was decided by jury, to improve public trust. However, none of the jurors were from Boston, as the court thought that Bostonians would be too biased against the British.

Adams argued that the soldiers feared for their lives, and were forced to open fire after the crowd attacked them. He claimed that the crowd got close enough to grab the soldier’s bayonets, although some eyewitness accounts contradicted this.

In the end, six of the eight soldiers were acquitted, including Captain Preston. Two soldiers who were found to have fired into the crowd were found guilty of manslaughter, and were sentenced to branding of the thumb, escaping the death penalty.

- The first person killed during the massacre is thought to be Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American descent. He is remembered as a significant figure in African-American history, as the first person killed during the American Revolution, five years before the Revolutionary War officially started.

- The term “Boston Massacre” was coined by Samuel Adams to emphasize the brutality of the event and rally public support against the British government. The word was used to evoke strong emotions, even though the killing was relatively small in scale compared to most definitions of the word “massacre”.

- Following the incident, Bostonians began the tradition of marking the anniversary of the event with speeches and commemorations, which became known as the “Boston Massacre Orations”.

- The famous engraving by Paul Revere, depicting the Boston Massacre, was actually based on a drawing by Henry Pelham, another artist. Revere’s version was altered to emphasize the violence of the British.

- It remains unclear who exactly fired the first shot during the Boston Massacre. Some reports suggest that a soldier was knocked down by a club or a stick, and his musket discharged as he fell, while others believe the firing was more deliberate.

Related posts

Diary of charles herbert, american prisoner of war in britain.

Read the diary of Charles Herbet, a Continental soldier that was captured by the British Army and sent to a prison of war camp in the UK.

1781 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1781 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

1780 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1780 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre , or the Incident on King Street, occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, on 5 March 1770, when nine British soldiers fired into a crowd of American colonists, ultimately killing five and wounding another six. The massacre was heavily propagandized by colonists such as Paul Revere and helped increase tensions in the early phase of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

In the mid-1760s, the Parliament of Great Britain attempted to directly tax the Thirteen Colonies of British North America to raise revenue in the aftermath of the expensive Seven Years' War (1756-1763). Although Parliament believed it was well within its authority, the American colonists disagreed; as subjects of the British Crown, the colonists believed they enjoyed the same rights as all Britons, including the right of self-taxation. Since the colonists were unrepresented in Parliament, they contended that Parliament had no power to directly tax them; prominent colonists like Samuel Adams (1722-1803) of Boston argued that the Americans would be resigning themselves to the status of 'tributary slaves' if they consented to pay the Parliamentary tax (Schiff, 73).

In April 1765, news reached the colonies that Parliament had issued the Stamp Act , a direct tax on all paper documents. The outraged colonists protested the Stamp Act in a variety of ways; the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a series of resolves denouncing the act as a violation of Americans' rights, while colonial merchants began boycotting British imports. However, the most dramatic opposition to the Stamp Act took place in Boston, the capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. On 14 August 1765, a mob of Bostonians hanged an effigy of Andrew Oliver, the stamp distributor for Massachusetts, from an elm tree before viciously ransacking his house that evening. Fearing for his life, Oliver resigned the next day, but the mob was unsatisfied; on 26 August, it attacked the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts, stealing all movable goods from the house. These riots were celebrated throughout the colonies; the Sons of Liberty, a loosely organized group of colonial political agitators, dated its founding from the riots, while the elm tree on which Oliver's effigy was hanged became known as Boston's 'Liberty Tree'.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766, but the colonists barely had time to celebrate before a new set of taxes and regulations, the Townshend Acts , were passed by Parliament between 1767 and 1768. These acts imposed new duties on goods such as glass, paint, and tea, and required a Board of Commissioners to set up headquarters in Boston to oversee the collection of the taxes. When the five commissioners arrived in Boston in November 1767, they were greeted by a hostile crowd carrying effigies and wearing labels that read, "Liberty & Property & no Commissioners" (Middlekauff, 163). Nor did the commissioners receive a much warmer welcome from Boston's leading citizens; John Hancock (1737-1793), one of the city's wealthiest merchants, refused to allow his Cadet Company, a military organization he operated, to participate in a parade held to welcome the commissioners. Eager to put men like Hancock in his place, the commissioners seized Hancock's sloop, the Liberty , on 10 June 1768, on the pretext that the Liberty had transported contraband goods and that its captain had threatened a tax collector.

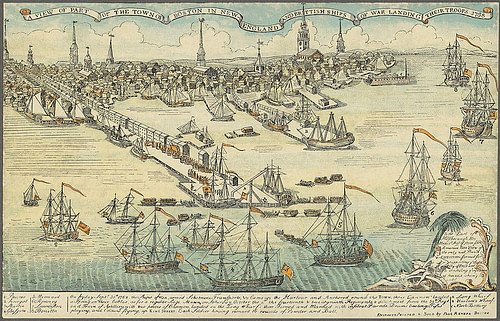

When British sailors arrived to take possession of the Liberty , they were greeted by a mob, who were already angry that the British had been impressing Boston sailors into the Royal Navy. A brawl broke out along the docks that soon blossomed into a city-wide riot, as thousands of colonists roamed the streets beating up tax collectors and attacking the commissioners' homes. The royal officials had to flee to Castle Island, a fortified island in Boston Harbor, to escape the violence. To restore order, General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of all British forces in North America, decided to move troops into Boston. Roughly 2,000 British soldiers, mostly from the 29th and 14th regiments, were loaded into transports and carried from Halifax to Boston, arriving in the town on 1 October 1768. A manifestation of Britain's imperial power, the red-coated soldiers disembarked and marched to Boston Common, their fixed bayonets gleaming in the sunlight.

A Garrison Town

The British force was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Dalrymple of the 14th Regiment, who sent a request to Boston officials to supply quarters and provisions for his men. The colonial authorities refused, telling Dalrymple that there were ample barracks on Castle Island, and until those barracks reached capacity, they would not pay for any British soldiers to be quartered in Boston itself. After several days of fruitless negotiations, during which time the British regiments remained stuck on the ships, Colonel Dalrymple finally had enough. He ordered all his men into Boston; if the stubborn local officials refused to provide quarters, Dalrymple would simply camp his men on Boston Common.

The majority of the 29th Regiment did indeed set up camp on the common, pitching their tents amongst the town's livestock, while the 14th Regiment got slightly luckier and moved into Faneuil Hall, drafty and cramped though it was. With the rapid approach of winter, these accommodations could only last for so long, and within weeks, the troops had moved into warehouses, inns, and other buildings rented out by private citizens. If the Bostonian officials had hoped to make a point by refusing to pay for the army's lodgings, Colonel Dalrymple had made a point of his own: until Boston cleaned up its act, the soldiers were here to stay. For the next year and a half, this was an unavoidable fact of life, as Bostonians and soldiers lived and worked side by side.

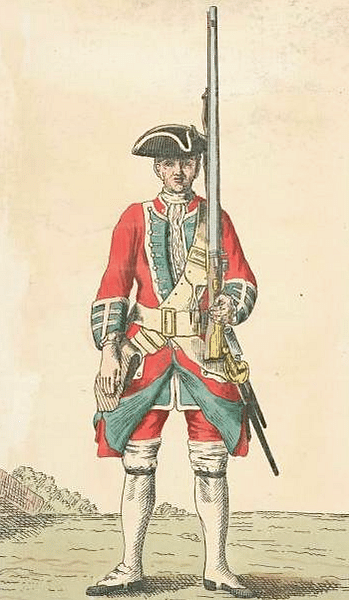

The enmity between the colonists and the soldiers was apparent from the beginning. The daily sight of armed redcoats patrolling their streets and standing guard outside public buildings was almost too much to bear for the Bostonians, who were unused to having their personal liberties challenged in such a way. The colonists particularly hated having their comings and goings challenged by British sentries, posted on major streets. Though it was standard procedure for sentries posted anywhere in Britain to challenge passers-by, the Bostonians resented this and often chose not to respond; this sometimes led to scuffles that would more than likely end with the unruly colonist being hit with a musket butt. Matters were not helped by the fact that off-duty soldiers often drank to excess, leading to several incidents where colonists were taunted or threatened by drunken soldiers.

The longer the British soldiers remained in Boston, the more they integrated themselves within the community, much to the chagrin of some of their new neighbors. Army regulations at the time allowed off-duty soldiers to find work at civilian jobs to supplement their military incomes. These soldiers were often willing to work below the going rate of pay, leading them to take jobs that Bostonian laborers felt belonged to them. Some British soldiers courted and even married Boston women , a union unacceptable to any self-respecting Son of Liberty. Bostonian Judge Richard Dana, for instance, went so far as to prevent his daughter from leaving the house, for fear that she would fraternize with a soldier.

At the same time, many Bostonians took pity on the British soldiers, especially after witnessing the harsh discipline they were subjected to. It was not uncommon for soldiers to receive hundreds of lashes for infractions that the colonists considered insignificant; one Private Daniel Rogers was sentenced to 1,000 lashes from a cat-o'-nine-tails after deserting his post to visit his family in nearby Marshfield. Rogers received 170 lashes before losing consciousness; he was spared from enduring the rest of his punishment after Bostonians petitioned Colonel Dalrymple to have mercy on him.

Private Richard Eames, another deserter, was not so lucky; after being caught on a farm in Framingham, Eames was executed by firing squad on Boston Common. Such actions horrified the colonists and convinced them of the cruelty of the British army. By April 1769, an average of one British soldier was deserting every two and a half days, a rate that alarmed military officials, who suspected that the colonists were aiding runaway soldiers. They were not wrong, as some Bostonians were actively encouraging the soldiers to desert; the rate of desertion added to the propaganda of the Sons of Liberty, who wasted no time using it to show that American life was preferable to life in the British army.

Murder of Christopher Seider

As tensions rose between Bostonians and British soldiers, colonial merchants' boycotts of the Townshend Acts remained in force. However, some merchants, like Theophilus Lillie, refused to comply with the boycotts; Lillie argued that the Bostonians had no more right to force him to comply with a boycott than Parliament had to tax the colonies. Lillie's outspokenness marked him as a target for Boston's liberty faction; on 22 February 1770, a crowd primarily comprised of young boys carried a sign to his shop that read "Importer", singling Lillie out as a violator of the boycott.

One of Lillie's neighbors, Ebenezer Richardson, attempted to shoo the crowd away and tear down the sign. Richardson was well-known as an informant for royal officials, and the crowd quickly redirected its anger toward him. The crowd followed him home and surrounded his house, with some participants shouting: "Come out you damn son of a bitch, I'll have your heart and liver out" (Middlekauff, 208). Richardson felt his life was in danger, and after some of the crowd began breaking his windows, he fired a gun into the mass of people. One boy was wounded and another, eleven-year-old Christopher Seider, was killed. Richardson was arrested and eventually convicted of murder, although he was ultimately freed when the king pardoned him.

The murder of young Seider only served to pour gas on the fire. Richardson was not a British soldier, but his actions increased the town's disdain of royal officials and of the soldiers, who were after all there to see those officials' policies carried out. The Sons of Liberty organized Seider's funeral, which was attended by thousands of Bostonians.

Brawl at Gray's Ropewalk

In the weeks following Seider's funeral, fights between soldiers and Bostonians became more frequent. The most consequential of these occurred on 2 March, when an off-duty soldier walked into John Gray's Ropewalk searching for a job. When the soldier asked a ropemaker if he had any work, the ropemaker responded that he did, inviting the soldier to "clean my shithouse" (Middlekauff, 209). The soldier took this as an insult and struck the ropemaker; their fight quickly turned into a street brawl as more soldiers and Bostonians joined the fray. The following day, several more fights broke out, often involving clubs and cudgels. With tensions in the city at an all-time high, it was only a matter of time before blood would be spilled.

The Incident

At 8 p.m. on 5 March 1770, Private Hugh White of the 29th Regiment was standing guard outside the customshouse on King Street. As he stood at his post, Private White overheard Edward Gerrish, an apprentice, insult an army officer by saying that there were "no gentlemen among the officers of the 29th" (Middlekauff, 210). White took it upon himself to discipline the lad by giving him a blow on the ear; Gerrish also appears to have been struck by an off-duty soldier standing nearby. Word that Gerrish had been accosted by a British soldier quickly spread and within 20 minutes, a crowd of angry Bostonians had surrounded Private White. The crowd hurled verbal abuse at the soldier; when White threatened to run them through with his bayonet if they did not disperse, the crowd started throwing snowballs and chunks of ice. White backed up to the door of the customshouse, where he attempted to hold back the mob singlehandedly.

Captain Thomas Preston watched with mounting unease. Preston was in command that evening and was aware that he would have to act if the crowd did not clear off on its own. It soon became apparent that Preston would have no such luck; the city's church bells began to ring, which usually meant that there was a fire. At first, scores of well-meaning civilians showed up carrying buckets of water to help put out the nonexistent flame, then others arrived, carrying clubs and even swords, their anger fueled by rumors that British soldiers meant to cut down the Liberty Tree. Preston decided to act; he ordered six privates and a corporal to follow him into the crowd, intending to rescue White. Preston and the soldiers easily pushed their way through the crowd but found themselves trapped when the Bostonians filled in behind them.

With the soldiers now trapped by the mob, Preston ordered his men to form a semicircle, their backs to the customshouse, and load their muskets. For 15 tense minutes, the standoff continued; some of the redcoats were recognized by the colonists as having participated in the brawl outside Gray's Ropewalk, leading tensions to increase. By this point, the crowd numbered 300-400, and angry Bostonians continued to throw snowballs and pieces of ice at the soldiers. Some colonists began striking the soldiers' muskets with sticks, daring them to fire. Captain Preston positioned himself in front of his men, at which point a colonist warned him to "take care of your men for if they fire, your life must be answerable." To this, Preston simply replied, "I am sensible of it" (Middlekauff, 211). An innkeeper named Richard Palmes then pulled Preston aside to inquire if the soldiers' muskets were loaded; Preston responded that they were but assured Palmes that they would not fire.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

As Preston and Palmes spoke, a piece of ice flung from the crowd hit Private Hugh Montgomery, causing him to slip and fall down. Montgomery staggered to his feet before discharging his musket into the crowd, despite having received no order to do so. After Montgomery's shot rang out, there was a short pause before the other soldiers opened fire. Eleven men were hit. Three died instantly including ropemaker Samuel Gray, mariner James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race sailor of African and Native American descent. Samuel Maverick, a 17-year-old apprentice, became the fourth victim when he died of his wounds the next morning, while Patrick Carr, an Irish immigrant, sustained a wound in the abdomen and lingered for two weeks before finally succumbing.

Although the crowd was scattered by the shooting, it had reformed within hours and began prowling the streets calling for vengeance against Captain Preston and his men. Lieutenant Governor Hutchinson knew he had to de-escalate the situation and had Preston and the other eight soldiers arrested the following day; the British soldiers were indicted for murder. Despite the rage that many Bostonians felt toward the British army, Boston officials were aware that they needed to ensure a fair trial, lest they give the army reason to retaliate. To achieve this purpose, the trials of Preston and his men were delayed until autumn, to give tempers time to cool off and to have a better chance of finding an impartial jury. The soldiers would be defended by John Adams (1735-1826), a Bostonian lawyer destined to become the second President of the United States. Although Adams was an ardent Patriot, he firmly believed that everyone was entitled to a fair trial, leading him to accept the case.

Captain Preston was tried first, in the last week of October 1770. After calling many witnesses who gave often contradictory accounts, Adams was able to give the jury reasonable doubt that Preston had given the order to fire, and the captain was acquitted. The other eight soldiers were tried together a month later; Adams told the jury that they had been accosted by a violent mob and had only fired out of self-defense. This mob, according to Adams, was comprised mainly of "molattoes, Irish teagues, and Jack Tars [i.e., sailors]" (Zabin, 216). By painting the mob as consisting mostly of those considered to be outsiders, he successfully deflected the blame from both the 'upstanding' Bostonians and the soldiers. Again, Adams achieved his goal; six soldiers were fully acquitted. Two were convicted of manslaughter and had their thumbs branded, a light punishment compared with the penalty of death that was originally on the table.

Although the soldiers were lightly punished, the people of Boston would not soon forget that five of their number had been killed in cold blood by soldiers of His Majesty's army. Tensions between colonists and redcoats only increased after the incident; a famous engraving by Paul Revere (1735-1818), based on an original by Henry Pelham, depicts the line of British soldiers calmly firing a volley into the crowd, Captain Preston standing behind them with his sword raised. While this is clearly a propagandized version of events, it became accepted by many colonists who began referring to the incident as the 'Boston Massacre'.

The massacre holds an important place in the story of the American Revolution, marking the first instance in which blood was spilled over the cause of American liberty. More colonists began to view Britain, and even the king, with distrust; after the massacre, the lines between American 'Loyalists', or supporters of Britain, and 'Patriots', or supporters of the Liberty cause, became more defined, helping to hasten the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and, ultimately, the drafting of the American Declaration of Independence .

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Boston Massacre | History, Facts, Site, Deaths, & Trial | Britannica , accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- Brands, H. W. The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. Anchor, 2002.

- McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Schiff, Stacy. The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams. Little, Brown and Company, 2022.

- Zabin, Serena R. . The Boston Massacre: A Family History. Mariner Books, 2020.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What was the boston massacre, was the boston massacre self-defense, what happened in the boston massacre trial, why was the boston massacre significant, related content.

Paul Revere

Townshend Acts

Samuel Adams

Boston Tea Party

Joseph Warren

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2023, November 13). Boston Massacre . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Boston_Massacre/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " Boston Massacre ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified November 13, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/Boston_Massacre/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " Boston Massacre ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 13 Nov 2023. Web. 28 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 13 November 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

The Boston Massacre

Written by: bill of rights institute, by the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how British colonial policies regarding North America led to the Revolutionary War

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Stamp Act Resistance Narrative and The Boston Tea Party Narrative following the Acts of Parliament Lesson to show the growing tensions between England and the colonies.

In late 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which taxed the colonists on purchases of British lead, glass, paint, paper, and tea. The British also headquartered customs officials in Boston to collect the new round of taxes and enforce trade regulations more stringently. The colonists could buy only British goods, and now those goods were hit with tariffs that meant there was no limit to Parliament’s taxing power, because the colonists were forbidden to manufacture many of their own goods.

Colonial reaction was swift. John Dickinson wrote in Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania that if Parliament succeeded in “taking money out of our pockets without our consent . . . our boasted liberty is but . . . a sound and nothing else.” Massachusetts sent other colonies a circular letter drafted by Samuel Adams denouncing the taxes. In Williamsburg, George Mason and George Washington followed the example of other colonies by creating an agreement not to import any British goods. Throughout the colonies, women held spinning bees, gatherings in their homes where they made homespun clothing as a symbol of republican simplicity to replace imported luxuries.

Bostonians protested the taxes in the streets, assembled at town meetings, and threatened customs officials, leading Royal Governor Francis Bernard to dissolve the assembly. The British also dispatched four thousand redcoats as a show of force to pacify the city. Many colonists considered the peacetime presence of this standing army, which their legislatures did not invite, a grave threat to their liberties and a gross violation of the 1689 English Bill of Rights. Its presence strained an already tense atmosphere. John Adams, cousin of Samuel Adams, wrote later that the troops’ “very appearance in Boston was a strong proof to me, that the determination in Great Britain to subjugate us was too deep and inveterate ever to be altered by us.” Fights erupted in taverns and streets as mobs of townspeople wielded insults, clubs, swords, and shovels against redcoats armed with bayonets.

On the morning of February 22, 1770, a crowd of hundreds threatened a merchant, Theophilus Lillie, who had violated the boycott of British goods. After Lillie’s neighbor, Ebenezer Richardson, rushed to his aid, the throng chased Richardson, who retreated inside his own house. The crowd lobbed taunts and rotten food. As his windows shattered, Richardson fired into the crowd, killing an eleven-year-old boy. The mob seized Richardson, beat him senseless, and nearly hanged him. Samuel Adams used the incident to portray the dead boy as a martyr to British tyranny and organized a funeral procession attended by thousands.

A few days later, near the customs house, a group of hostile boys insulted a young sentry who responded by smashing the butt of his musket into a boy’s head. The church bells tolled, bringing hundreds of citizens into the streets to pelt the sentry with snowballs, rocks, and ice. Captain Thomas Preston marched a few men out to relieve the sentry, forming a line and ordering the crowd to disperse. In the skirmishes that followed, one soldier was knocked down by a club; he rose and discharged his musket. The rest of the soldiers fired a volley that struck eleven Bostonians, instantly killing three and mortally wounding two more. Preston and his men were jailed that night, and the rest of the troops relocated to a fort in Boston harbor, narrowly averting a full-scale battle.

Patriot leaders seized on the “massacre” for a public relations victory. The British government – responsible for protecting its subjects’ rights to life, liberty, and property – in the years since the French and Indian War had seemed to seize colonists’ property and curtail their liberty; now its soldiers had taken their lives. Ten thousand mourners attended the funeral procession staged by Samuel Adams. Silversmith Paul Revere contributed an engraving showing bloodthirsty soldiers firing at innocent civilians; it was mostly propaganda but served to galvanize many colonists’ feelings about British oppression.

Why would Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre rouse colonists toward the Patriot cause?

John Adams, then a practicing lawyer, defended the British soldiers in court, an unpopular decision that nevertheless defined his stand for justice and the rule of law. Preston was judged not to have given an order to fire and was acquitted. Most of the soldiers were also acquitted on the grounds of self-defense. Adams had proved that in the colonies, the law was supreme. He staked his public reputation and Patriot credentials on the principle that the traditional rights of Englishmen were deserved by all, even hated British soldiers who had slain five colonists. His courageous act contributed to a relative calm that lasted a few years. Meanwhile, Parliament revoked the hated Townshend Acts, except, fatefully, the tax on tea.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following methods was not used by colonists to protest the Acts passed by Parliament after the French and Indian War?

- Boycotting British imports such as textiles

- Publishing written arguments in newspapers and pamphlets

- Antagonizing British soldiers in the streets with verbal and physical attacks

- Forming militia and securing funds to declare a war for independence

2. The Boston Massacre refers to

- the period when mobs frequently wounded or killed British soldiers in the streets of Boston because the soldiers were viewed as symbols of British tyranny

- the episode in which a Boston mob attacked British soldiers who then fired into the crowd, killing five colonists

- the period when the British enforced the Stamp, Sugar, Tea, and Townshend Acts on the colonies

- the funerals held for murdered colonists that thousands of Bostonians attended to demonstrate solidarity against the British

3. Which of the following provides an example of colonists participating in an economic protest against the Townsend Acts?

- Well-known leaders like John Dickinson writing circular letters in protest

- Women creating homespun clothes instead of purchasing imported goods

- An organization called the Sons of Liberty burning effigies in public

- Protestors dressing up like American Indians and dumping tea into the harbor

4. What was the effect of the Boston Massacre engraving and funeral procession in other colonies?

- Patriots in other colonies interpreted the Boston event as a danger to all colonies.

- Newspapers barely reported the events and few colonists took notice.

- Loyalists were impressed by the successful actions taken by the British to regain control.

- Immediate actions were taken to create an intercolonial body that would protest these actions.

5. What was John Adams’ intention when he defended the British redcoats involved in the Boston Massacre?

- Adams was a fierce Loyalist who believed the crown had absolute authority in the colonies and desired to prove the redcoats had committed no crime.

- Adams wanted each redcoat to suffer the consequences of his murderous actions.

- Adams desired to prove that the colonists, regardless of their political rage, would always uphold the rule of law.

- Adams longed for a position as a lawyer in Great Britain and knew this case could fulfill his dream.

6. Which of the following was Britain’s direct response to the Boston Massacre?

- Passage of the Declaratory Act, reasserting British jurisdiction over the colonies

- Closing of Boston Harbor in retaliation for colonial economic protest

- Repeal of all Townsend Act taxes except the one on tea

- Awarding of religious freedom to French-Canadian colonists under British rule

7. Which of the following best contextualizes the Boston Massacre?

- British declared that each purchased paper item would require a stamp tax.

- The Proclamation of 1763 prohibited settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains.

- Rowdy colonists dressed as American Indians and poured East India Tea into the harbor.

- British customs officials were headquartered in Boston to enforce the newly declared Townsend Acts.

Free Response Questions

- Briefly summarize the interactions between the British government and North American colonists that led to the Boston Massacre.

- Explain how John Adams’s defense of British troops in Boston demonstrated the strength of the rule of law in colonial America.

AP Practice Questions

“And thereupon the said Lords Spiritual and Temporal and Commons, pursuant to their respective letters and elections, being now assembled in a full and free representative of this nation, taking into their most serious consideration the best means for attaining the ends aforesaid, do in the first place (as their ancestors in like case have usually done) for the vindicating and asserting their ancient rights and liberties declare That the pretended power of suspending the laws or the execution of laws by regal authority without consent of Parliament is illegal; That the pretended power of dispensing with laws or the execution of laws by regal authority, as it hath been assumed and exercised of late, is illegal; That the commission for erecting the late Court of Commissioners for Ecclesiastical Causes, and all other commissions and courts of like nature, are illegal and pernicious; That levying money for or to the use of the Crown by pretence of prerogative, without grant of Parliament, for longer time, or in other manner than the same is or shall be granted, is illegal; That it is the right of the subjects to petition the king, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal; That the raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, unless it be with consent of Parliament, is against law.”

English Bill of Rights, 1689

1. The principle expressed in the English Bill of Rights that contributed most to the tensions in Boston was

- the right of petition should not be denied

- a standing army should not be kept among them during a time of peace

- the king should not suspend or ignore laws

- special courts should not be convened

2. Taken as a whole, the English Bill of Rights most clearly demonstrates the British belief in the principle of

- due process

- regal authority

- the rule of law

- the common good

“The mob still increased and were more outrageous, striking their clubs or bludgeons one against another, and calling out, come on you rascals, you bloody backs, you lobster scoundrels, fire if you dare, G-d damn you, fire and be damned. . . . At this time I was between the soldiers and the mob, parleying with, and endeavouring all in my power to persuade them to retire peaceably, but to no purpose. . . . On this a general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs and snowballs being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger, some persons at the same time from behind calling out, damn your bloods-why don’t you fire. Instantly three or four of the soldiers fired, one after another, and directly after three more in the same confusion and hurry. The mob then ran away, except three unhappy men who instantly expired, in which number was Mr. Gray at whose rope-walk the prior quarrels took place; one more is since dead, three others are dangerously, and four slightly wounded. The whole of this melancholy affair was transacted in almost 20 minutes. On my asking the soldiers why they fired without orders, they said they heard the word fire and supposed it came from me. This might be the case as many of the mob called out fire, fire, but I assured the men that I gave no such order; that my words were, don’t fire, stop your firing.”

Captain Prescott, Account of the Boston Massacre, 1770

3. The excerpt gives historians insight into the

- likelihood that authors who opposed British policy exploited the event for political gain by omitting certain details

- strict discipline was observed by all redcoats assigned to Boston even in tense situations

- health care provided to those injured during conflict regardless of race or social status

- nonviolent protest strategies colonists used to decry perceived British injustice

4. An important consequence of the account described in the excerpt was that the

- British soldiers were acquitted on the grounds of self-defense

- British soldiers were reprimanded in colonial courts and then executed

- Colonial vigilantes took to the streets to silence any further discussion of the massacre

- Colonial minutemen began stockpiling weapons for a retaliatory offensive

5. Which of the following best describes a reaction to the event described in the excerpt?

- Colonists along the Atlantic seaboard realized the tense circumstances caused unnecessary death and vowed to restore order in their cities.

- British parliament was so moved by the Captain’s words that it ordered his troops to escort the funeral for those unfairly slain.

- Patriots used the event to galvanize citizens by producing images and rhetoric.

- Imperial rivals, such as France and Spain, sent letters of caution to Great Britain encouraging it to reduce the force used in the colonies.

Primary Sources

“Biography of John Adams. The Boston Massacre.” American History. University of Groningen. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/biographies/john-adams/the-boston-massacre.php

Chappel, Alonzo. Boston Massacre . Printed 1878 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-e8e9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770. https://gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/road-revolution/resources/paul-revere%E2%80%99s-engraving-boston-massacre-1770

Suggested Resources

Archer, Richard. As If an Enemy’s Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

McCullough, David. John Adams . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Zobel, Hiller B. The Boston Massacre . New York: Norton, 1970.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Perspectives on the Boston Massacre

- Reactions and Responses

- The Massacre Illustrated

- Anniversaries

- Browse Items by Format

Eventually two trials (one for Captain Preston, the other for the eight British soldiers) were held in the fall of 1770, with John Adams and Josiah Quincy serving as defense attorneys for the soldiers and Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine representing the “Relatives of the Deceased.” Even after the verdicts were announced - the Captain and six soldiers were acquitted, while two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter - the reverberations of the Boston Massacre continued, including annual commemorations held by colonists as a way of supporting or furthering the Revolutionary cause.

We invite you to read and examine materials offering a range of perspectives on this important event in our nation's history.

Funding from the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati supported this project.

American Revolution: The Boston Massacre

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/khickman-5b6c7044c9e77c005075339c.jpg)

- M.A., History, University of Delaware

- M.S., Information and Library Science, Drexel University

- B.A., History and Political Science, Pennsylvania State University

In the years following the French and Indian War , the Parliament increasingly sought ways to alleviate the financial burden caused by the conflict. Assessing methods for raising funds, it was decided to levy new taxes on the American colonies with the goal of offsetting some of the cost for their defense. The first of these, the Sugar Act of 1764 , was quickly met by outrage from colonial leaders who claimed "taxation without representation," as they had no members of Parliament to represent their interests. The following year, Parliament passed the Stamp Act which called for tax stamps to be placed on all paper goods sold in the colonies. The first attempt to apply a direct tax to the North American colonies, the Stamp Act was met with widespread protests.

Across the colonies, new protest groups, known as the " Sons of Liberty " formed to fight the new tax. Uniting in the fall of 1765, colonial leaders appealed to Parliament stating that as they had no representation in Parliament, the tax was unconstitutional and against their rights as Englishmen. These efforts led to the Stamp Act's repeal in 1766, though Parliament quickly issued the Declaratory Act which stated that they retained the power to tax the colonies. Still seeking additional revenue, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in June 1767. These placed indirect taxes on various commodities such as lead, paper, paint, glass, and tea. Again citing taxation without representation, the Massachusetts legislature sent a circular letter to their counterparts in the other colonies asking them to join in resisting the new taxes.

London Responds

In London, the Colonial Secretary, Lord Hillsborough, responded by directing colonial governor to dissolve their legislatures if they responded to the circular letter. Sent in April 1768, this directive also ordered the Massachusetts legislature to rescind the letter. In Boston, customs officials began to feel increasingly threatened which led their chief, Charles Paxton, to request a military presence in the city. Arriving in May, HMS Romney (50 guns) took up a station in the harbor and immediately angered Boston's citizens when it began impressing sailors and intercepting smugglers. Romney was joined that fall by four infantry regiments which were dispatched to the city by General Thomas Gage . While two were withdrawn the following year, the 14th and 29th Regiments of Foot remained in 1770. As military forces began to occupy Boston, colonial leaders organized boycotts of the taxed goods in an effort to resist the Townshend Acts.

The Mob Forms

Tensions in Boston remained high in 1770 and worsened on February 22 when young Christopher Seider was killed by Ebenezer Richardson. A customs official, Richardson had randomly fired into a mob that had gathered outside his house hoping to make it disperse. Following a large funeral, arranged by Sons of Liberty leader Samuel Adams , Seider was interred at the Granary Burying Ground. His death, along with a burst of anti-British propaganda, badly inflamed the situation in the city and led many to seek confrontations with British soldiers. On the night of March 5, Edward Garrick, a young wigmaker's apprentice, accosted Captain Lieutenant John Goldfinch near the Custom House and claimed that the officer had not paid his debts. Having settled his account, Goldfinch ignored the taunt.

This exchange was witnessed by Private Hugh White who was standing guard at the Custom House. Leaving his post, White exchanged insults with Garrick before striking him in the head with his musket . As Garrick fell, his friend, Bartholomew Broaders, took up the argument. With tempers rising, the two men created a scene and a crowd began to gather. In an effort to quiet the situation, local book merchant Henry Knox informed White that if he fired his weapon he would be killed. Withdrawing to safety of the Custom House stairs, White awaited aid. Nearby, Captain Thomas Preston received word of White's predicament from a runner.

Blood on the Streets

Gathering a small force, Preston departed for the Custom House. Pushing through the growing crowd, Preston reached White and directed his eight men to form a semi-circle near the steps. Approaching the British captain, Knox implored him to control his men and reiterated his earlier warning that if his men fired he would be killed. Understanding the delicate nature of the situation, Preston responded that he was aware of that fact. As Preston yelled at the crowd to disperse, he and his men were pelted with rocks, ice, and snow. Seeking to provoke a confrontation, many in the crowd repeatedly yelled "Fire!" Standing before his men, Preston was approached by Richard Palmes, a local innkeeper, who inquired if the soldiers' weapons were loaded. Preston confirmed that they were but also indicated that he was unlikely to order them to fire as he was standing in front of them.

Shortly thereafter, Private Hugh Montgomery was hit with an object that caused him to fall and drop his musket. Angered, he recovered his weapon and yelled "Damn you, fire!" before shooting into the mob. After a brief pause, his compatriots began firing into the crowd though Preston had not given orders to do so. In the course of the firing, eleven were hit with three being killed instantly. These victims were James Caldwell, Samuel Gray, and Crispus Attucks . Two of the wounded, Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr, died later. In the wake of the firing, the crowd withdrew to the neighboring streets while elements of the 29th Foot moved to Preston's aid. Arriving on the scene, Acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson worked to restore order.

Immediately beginning an investigation, Hutchison bowed to public pressure and directed that British troops be withdrawn to Castle Island. While the victims were laid to rest with great public fanfare, Preston and his men were arrested on March 27. Along with four locals, they were charged with murder. As tensions in the city remained dangerously high, Hutchinson worked to delay their trial until later in the year. Through the summer, a propaganda war was waged between the Patriots and Loyalists as each side tried to influence opinion abroad. Eager to build support for their cause, the colonial legislature endeavored to ensure that the accused received a fair trial. After several notable Loyalist attorneys refused to defend Preston and his men, the task was accepted by well-known Patriot lawyer John Adams .

To assist in the defense , Adams selected Sons of Liberty leader Josiah Quincy II, with the organization's consent, and Loyalist Robert Auchmuty. They were opposed by Massachusetts Solicitor General Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine. Tried separately from his men, Preston faced the court in October. After his defense team convinced the jury that he had not ordered his men to fire, he was acquitted. The following month, his men went to court. During the trial, Adams argued that if the soldiers were threatened by the mob, they had a legal right to defend themselves. He also pointed out that if they were provoked, but not threatened, the most they could be guilty of was manslaughter. Accepting his logic, the jury convicted Montgomery and Private Matthew Kilroy of manslaughter and acquitted the rest. Invoking the benefit of clergy, the two men were publicly branded on the thumb rather than imprisoned.

Following the trials, tension in Boston remained high. Ironically, on March 5, the same day as the massacre, Lord North introduced a bill in Parliament that called for a partial repeal of the Townshend Acts. With the situation in the colonies reaching a critical point, Parliament eliminated most aspects of the Townshend Acts in April 1770, but left a tax on tea. Despite this, conflict continued to brew. It would come to head in 1774 following the Tea Act and the Boston Tea Party . In the months after the latter, Parliament passed a series of punitive laws, dubbed the Intolerable Acts , which set the colonies and Britain firmly on the path to war. The American Revolution would begin on April 19, 1775, when to two sides first clashed at Lexington and Concord .

- Massachusetts Historical Society: The Boston Massacre

- Boston Massacre Trials

- iBoston: Boston Massacre

- The Root Causes of the American Revolution

- American Revolution: Boston Tea Party

- American Revolution: The Intolerable Acts

- Questions Left by The Boston Massacre

- All About the Sons of Liberty

- American Revolution: Siege of Boston

- The Battles of Lexington and Concord

- American Revolution: The Townshend Acts

- American Revolution Battles

- John Hancock: Founding Father With a Famous Signature

- The Currency Act of 1764

- Quartering Act, British Laws Opposed by American Colonists

- Biography of Paul Revere: Patriot Famous for His Midnight Ride

- American Revolution: The Stamp Act of 1765

- American Revolution: Early Campaigns

- An Introduction to the American Revolutionary War

Account of the Boston Massacre

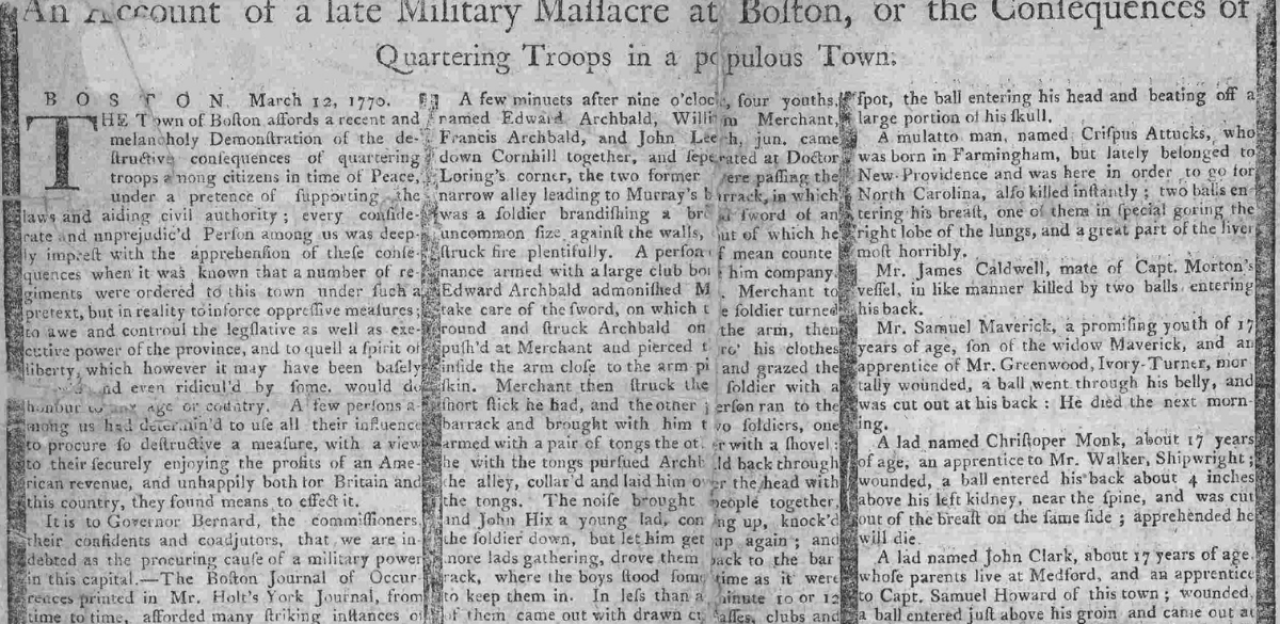

An Account of a late Military Massacre at Boston, or the Consequences of Quartering Troops in a populous Town.

BOSTON March 12, 1770.

THE Town of Boston affords a recent and melancholy Demonstration of the destructive consequences of quartering troops among citizens in time of Peace, under a pretence of supporting the laws and aiding civil authority; every considerate and unprejudic'd Person among us was deeply imprest with the apprehension of these consequences when it was known that a number of regiments were ordered to this town under such a pretext, but in reality to inforce oppressive measures; to awe and controul the legslative as well as executive power of the province, and to quell a spirit of liberty, which however it may have been basely and even ridicul'd by some, would do honour to any age or country. A few persons among us had determin'd to use all their influence to procure so destructive a measure, with a view to their securely enjoying the profits of an American revenue, and unhappily both for Britain and this country, they found means to effect it.

It is to Governor Bernard, the commissioners, their confidents and coadjutors, that we are indebted as the procuring cause of a military power in this capital.—The Boston Journal of Occurrences printed in Mr. Holt's York Journal, from time to time, afforded many striking instances of the distresses brought upon the inhabitants by this measure; and since those Journals have been discontinued, our troubles from that quarter have been growing upon us: We have known a party of soldiers in the face of day fire off a loaded musket upon the inhabitants, others have been prick'd with bayonets, and even our magistrate assaulted and put in danger of their lives, where offenders brought before them have been rescued and why those and other bold and base criminals have as yet escaped the punishment due to their crimes, may be soon matter of enquiry by the representative body of this people.—It is natural to suppose that when the inhabitants saw those laws which had been enacted for their security, and which they were ambitious of holding up to the soldiery, eluded, they should most commonly resent for themselves—and accordingly if so has happened; many have been the squabbles between them and the soldiery; but it seems their being often worsted by our youth in those ren counters, has only serv'd to irritate the former.—What passed at Mr. Gray's rope walk, has already been given the public, and may be said to have led the way to the late catastrophe.—That the rope walk lads when attacked by superior numbers should defend themselves with so much spirit and success in the club-way, was too mortifying, and perhaps it may hereafter appear, that even some of their officers, were unnappily affected with this circumstance: Divers stories were propagated among the soldiery, that serv'd to agitate their spirits particularly on the Sabbath, that one Chambers, a serjeant, represented as a sober man, had been missing the preceding day, and must therefore have been murdered by the townsmen; an officer of distinction so far credited this report, that he enter'd Mr. Gray's rope-walk that Sabbath; and when enquired of by that gentleman as soon as he could meet him, the occasion of his so doing, the officer reply'd, that it was to look if the serjeant said to be murdered had not been hid there; this sober serjeant was found on the Monday unhurt in a house of pleasure.—The evidences already collected shew, that many threatnings had been thrown out by the soldiery, but we do not pretend to say there was any preconcerted plan; when the evidences are published, the world will judge.—We may however venture to declare, that it appears too probable from their conduct, that some of the soldiery aimed to draw and provoke the townsmen into squabbles, and that they then intended to make use of other weapons than canes, clubs or bludgeons,

Our readers will doubtless expect a circumstantial account of the tragical affair on Monday night last; but we hope they will excuse our being so particular as we should have been, had we not seen that the town was intending an inquiry and full representation thereof.

On the evening of Monday, being the 5th current, several soldiers of the 29th regiment were seen parading the streets with their drawn cutlasses and , abusing and wounding numbers of the .

A few minutes after nine o'clock, four youths, named Edward Archbald, William Merchant, Francis Archbald, and John Leech, jun. came down Cornhill together, and seperated at Doctor Loring's corner, the two former were passing the narrow alley leading to Murray's barrack, in which was a soldier brandishing a sword of an uncommon size against the walls, but of which he struck fire plentifully. A person of mean countenance armed with a large club bore him company. Edward Archbald admonished Mr. Merchant to take care of the sword, on which the soldier turned round and struck Archbald on the arm, then push'd at Merchant and pierced thro' his clothes inside the arm close to the arm pit and grazed the skin. Merchant then struck the soldier with a short stick he had, and the other person ran to the barrack and brought with him two soldiers, one armed with a pair of tongs the other with a shovel; he with the tongs pursued Archbald back through the alley, collar'd and laid him over the head with the tongs. The noise brought people together, and John Hix a young lad, coming up, knock'd the soldier down, but let him get up again; and more lads gathering, drove them back to the barrack, where the boys stood sometime as it were to keep them in. In less than a minute 10 or 12 of them came out with drawn cutlasses, clubs and bayonets, and set upon the med boys and young folks, who stood them a little while but finding the inequality of their equipment dispersed.—On hearing the noise, one Samuel Atwood, came up to see what was the matter, and entering the alley from dock square, heard the latter part of the combat, and when the boys dispersed he met the 10 or 12 soldiers aforesaid rushing down the alley towards the square, and asked them if they intended to murder the people? They answered Yes, by G—d, root and branch! With that one of them struck Mr. Atwood with a club, which was repeated by another and being he turned to go off, received a wound on the left shoulder which reached the bone and gave him much pain. Retreating a few steps Mr Atwood met two offcers and said, Gentlemen what is the matter? They answered, you'll see by and by. Immediately after those heroes appeared in the square, asking where were the boogers where were the cowards? But notwithstanding their fierceness to naked men, one of them advanced towards a youth who had a split of a raw stave in his hand, and said damn them here is one of them; but the young man seeing a person near him with a drawn sword and a good cane ready to support him, held up his stave in defiance, and they quietly passed by him, up the little alley by Mr. Silsby's to King Street, where they attacked single and unarmed persons till they raised much clamour, and then turned down Cornhill street insulting all they met in like manner, and pursuing some to their very doors.