The alarming state of the American student in 2022

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, robin lake and robin lake director, center on reinventing public education - arizona state university travis pillow travis pillow innovation fellow, center on reinventing public education - arizona state university.

November 1, 2022

The pandemic was a wrecking ball for U.S. public education, bringing months of school closures, frantic moves to remote instruction, and trauma and isolation.

Kids may be back at school after three disrupted years, but a return to classrooms has not brought a return to normal. Recent results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) showed historic declines in American students’ knowledge and skills and widening gaps between the highest- and lowest-scoring students.

But even these sobering results do not tell us the whole story.

After nearly three years of tracking pandemic response by U.S. school systems and synthesizing knowledge about the impacts on students, we sought to establish a baseline understanding of the contours of the crisis: What happened and why, and where do we go from here?

This first annual “ State of the American Student ” report synthesizes nearly three years of research on the academic, mental health, and other impacts of the pandemic and school closures.

It outlines the contours of the crisis American students have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic and begins to chart a path to recovery and reinvention for all students—which includes building a new and better approach to public education that ensures an educational crisis of this magnitude cannot happen again.

The state of American students as we emerge from the pandemic is still coming into focus, but here’s what we’ve learned (and haven’t yet learned) about where COVID-19 left us:

1. Students lost critical opportunities to learn and thrive.

• The typical American student lost several months’ worth of learning in language arts and more in mathematics.

• Students suffered crushing increases in anxiety and depression. More than one in 360 U.S. children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19.

• Students poorly served before the pandemic were profoundly left behind during it, including many with disabilities whose parents reported they were cut off from essential school and life services.

This deeply traumatic period threatens to reverberate for decades. The academic, social, and mental-health needs are real, they are measurable, and they must be addressed quickly to avoid long-term consequences to individual students, the future workforce, and society.

2. The average effects from COVID mask dire inequities and widely varied impact.

Some students are catching up, but time is running out for others. Every student experienced the pandemic differently, and there is tremendous variation from student to student, with certain populations—namely, Black, Hispanic, and low-income students, as well as other vulnerable populations—suffering the most severe impacts.

The effects were more severe where campuses stayed closed longer. American students are experiencing a K-shaped recovery, in which gaps between the highest- and lowest-scoring students, already growing before the pandemic, are widening into chasms. In the latest NAEP results released in September , national average scores fell five times as much in reading, and four times as much in math, for the lowest-scoring 10 percent of nine-year-olds as they had for the highest-scoring 10 percent.

At the pace of recovery we are seeing today, too many students of all races and income levels will graduate in the coming years without the skills and knowledge needed for college and careers.

3. What we know at this point is incomplete. The situation could be significantly worse than the early data suggest.

The data and stories we have to date are enough to warrant immediate action, but there are serious holes in our understanding of how the pandemic has affected various groups of students, especially those who are typically most likely to fall through the cracks in the American education system.

We know little about students with complex needs, such as those with disabilities and English learners. We still know too little about the learning impacts in non-tested subjects, such as science, civics, and foreign languages. And while psychologists , educators , and the federal government are sounding alarms about a youth mental health crisis, systematic measures of student wellbeing remain hard to come by.

We must acknowledge that what we know at this point is incomplete, since the pandemic closures and following recovery have been so unprecedented in recent times. It’s possible that as we continue to dig into the evidence on the pandemic’s impacts, some student groups or subjects may have not been so adversely affected. Alternatively, the situation could be significantly worse than the early data suggest. Some students are already bouncing back quickly. But for others, the impact could grow worse over time.

In subjects like math, where learning is cumulative, pandemic-related gaps in students’ learning that emerged during the pandemic could affect their ability to grasp future material. In some states, test scores fell dramatically for high schoolers nearing graduation. Shifts in these students’ academic trajectories could affect their college plans—and the rest of their lives. And elevated rates of chronic absenteeism suggest some students who disconnected from school during the pandemic have struggled to reconnect since.

4. The harms students experienced can be traced to a rigid and inequitable system that put adults, not students, first.

• Despite often heroic efforts by caring adults, students and families were cut off from essential support, offered radically diminished learning opportunities, and left to their own devices to support learning.

• Too often, partisan politics, not student needs , drove decision-making.

• Students with complexities and differences too often faced systems immobilized by fear and a commitment to sameness rather than prioritization and problem-solving.

So, what can we do to address the situation we’re in?

Diverse needs demand diverse solutions that are informed by pandemic experiences

Freed from the routines of rigid systems, some parents, communities, and educators found new ways to tailor learning experiences around students’ needs. They discovered learning can happen any time and anywhere. They discovered enriching activities outside class and troves of untapped adult talent.

Some of these breakthroughs happened in public schools—like virtual IEP meetings that leveled power dynamics between administrators and parents advocating for their children’s special education services. Others happened in learning pods or other new environments where families and community groups devised new ways to meet students’ needs. These were exceptions to an otherwise miserable rule, and they can inform the work ahead.

We must act quickly but we must also act differently. Important next steps include:

• Districts and states should immediately use their federal dollars to address the emergent needs of the COVID-19 generation of students via proven interventions, such as well-designed tutoring, extended learning time, credit recovery, additional mental health support, college and career guidance, and mentoring. The challenges ahead are too daunting for schools to shoulder alone. Partnerships and funding for families and community-driven solutions will be critical.

• By the end of the 2022–2023 academic year, states and districts must commit to an honest accounting of rebuilding efforts by defining, adopting, and reporting on their progress toward 5- and 10-year goals for long-term student recovery. States should invest in rigorous studies that document, analyze, and improve their approaches.

• Education leaders and researchers must adopt a national research and development agenda for school reinvention over the next five years. This effort must be anchored in the reality that the needs of students are so varied, so profound, and so multifaceted that a one-size-fits-all approach to education can’t possibly meet them all. Across the country, community organizations who previously operated summer or afterschool programs stepped up to support students during the school day. As they focus on recovery, school system leaders should look to these helpers not as peripheral players in education, but as critical contributors who can provide teaching , tutoring, or joyful learning environments for students and often have trusting relationships with their families.

• Recovery and rebuilding should ensure the system is more resilient and prepared for future crises. That means more thoughtful integration of online learning and stronger partnerships with organizations that support learning outside school walls. Every school system in America should have a plan to keep students safe and learning even when they can’t physically come to school, be equipped to deliver high-quality, individualized pathways for students, and build on practices that show promise.

Our “State of the American Student” report is the first in a series of annual reports the Center on Reinventing Public Education intends to produce through fall of 2027. We hope every state and community will produce similar, annual accounts and begin to define ambitious goals for recovery. The implications of these deeply traumatic years will reverberate for decades unless we find a path not only to normalcy but also to restitution for this generation and future generations of American students.

The road to recovery can lead somewhere new. In five years, we hope to report that out of the ashes of the pandemic, American public education emerged transformed: more flexible and resilient, more individualized and equitable, and—most of all— more joyful.

Related Content

Joao Pedro Azevedo, Amer Hasan, Koen Geven, Diana Goldemberg, Syedah Aroob Iqbal

July 30, 2020

Matthew A. Kraft, Michael Goldstein

May 21, 2020

Dan Silver, Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff

August 16, 2022

Early Childhood Education K-12 Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Online only

Wednesday, 9:00 am - 10:00 am EST

October 30, 2024

Katharine Meyer

October 28, 2024

The global education crisis – even more severe than previously estimated

Ellinore carroll, joão pedro azevedo, jessica bergmann, matt brossard, gwang- chol chang, borhene chakroun, marie-helene cloutier, suguru mizunoya, nicolas reuge, halsey rogers.

In our recent The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery report (produced jointly by UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank), we sounded the alarm: this generation of students now risks losing $17 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value, or about 14 percent of today’s global GDP, because of COVID-19-related school closures and economic shocks. This new projection far exceeds the $10 trillion estimate released in 2020 and reveals that the impact of the pandemic is more severe than previously thought .

The pandemic and school closures not only jeopardized children’s health and safety with domestic violence and child labor increasing, but also impacted student learning substantially. The report indicates that in low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty – already above 50 percent before the pandemic – could reach 70 percent largely as a result of the long school closures and the relative ineffectiveness of remote learning.

Unless action is taken, learning losses may continue to accumulate once children are back in school, endangering future learning.

Figure 1. Countries must accelerate learning recovery

Severe learning losses and worsening inequalities in education

Results from global simulations of the effect of school closures on learning are now being corroborated by country estimates of actual learning losses. Evidence from Brazil , rural Pakistan , rural India , South Africa , and Mexico , among others, shows substantial losses in math and reading. In some low- and middle-income countries, on average, learning losses are roughly proportional to the length of the closures—meaning that each month of school closures led to a full month of learning losses (Figure 1, selected LMICs and HICs presents an average effect of 100% and 43%, respectively), despite the best efforts of decision makers, educators, and families to maintain continuity of learning.

However, the extent of learning loss varies substantially across countries and within countries by subject, students’ socioeconomic status, gender, and age or grade level (Figure 1 illustrates this point, note the large standard deviation, a measure which shows data are spread out far from the mean). For example, results from two states in Mexico show significant learning losses in reading and in math for students aged 10-15. The estimated learning losses were greater in math than reading, and they disproportionately affected younger learners, students from low-income backgrounds, and girls.

Figure 2. The average learning loss standardized by the length of the school closure was close to 100% in Low- and Middle-Income countries, and 43% in High-Income countries, with a standard deviation of 74% and 30%, respectively.

While most countries have yet to measure learning losses, data from several countries, combined with more extensive evidence on unequal access to remote learning and at-home support, shows the crisis has exacerbated inequalities in education globally.

- Children from low-income households, children with disabilities, and girls were less likely to access remote learning due to limited availability of electricity, connectivity, devices, accessible technologies as well as discrimination and social and gender norms.

- Younger students had less access to age-appropriate remote learning and were more affected by learning loss than older students. Pre-school-age children, who are at a pivotal stage for learning and development, faced a double disadvantage as they were often left out of remote learning and school reopening plans.

- Learning losses were greater for students of lower socioeconomic status in various countries, including Ghana , Mexico , and Pakistan .

- While the gendered impact of school closures on learning is still emerging, initial evidence points to larger learning losses among girls, including in South Africa and Mexico .

As a result, these children risk missing out on much of the boost that schools and learning can provide to their well-being and life chances. The learning recovery response must therefore target support to those that need it most, to prevent growing inequalities in education.

Beyond learning, growing evidence shows the negative effects school closures have had on students’ mental health and well-being, health and nutrition, and protection, reinforcing the vital role schools play in providing comprehensive support and services to students.

Critical and Urgent Need to Focus on Learning Recovery

How should decision makers and the international community respond to the growing global education crisis?

Reopening schools and keeping them open must be the top priority, globally. While nearly every country in the world offered remote learning opportunities for students, the quality and reach of such initiatives varied, and in most cases, they offered a poor substitute for in-person instruction. Stemming and reversing learning losses, especially for the most vulnerable students, requires in-person schooling. Decision makers need to reassure parents and caregivers that with adequate safety measures, such as social distancing, masking, and improved ventilation, global evidence shows that children can resume in-person schooling safely.

But just reopening schools with a business-as-usual approach won’t reverse learning losses. Countries need to create Learning Recovery Programs . Three lines of action will be crucial:

- Consolidating the curriculum – to help teachers prioritize essential material that students have missed while out of school, even if the content is usually covered in earlier grades, to ensure the curriculum is aligned to students’ learning levels. As an example, Tanzania consolidated its curriculum for grade 1 and 2 in 2015, reducing the number of subjects taught and increasing time on ensuring the acquisition of foundational numeracy and literacy.

- Extending instructional time – by extending the school day, modifying the academic calendar to make the school year longer, or by offering summer school for all students or those in need. In Mexico , the Ministry of Public Education announced planned extensions to the academic calendar to help recovery. In Madagascar , the government scaled up an existing two-month summer “catch-up” program for students who reintegrate into school after having left the system.

- Improving the efficiency of learning – by supporting teachers to apply structured pedagogy and targeted instruction. A structured pedagogy intervention in Kenya using teachers guides with lesson plans has proven to be highly effective. Targeted instruction, or aligning instruction to students’ learning level, has been successfully implemented at scale in Cote D’Ivoire .

Finally, the report emphasizes the need for adequate funding. As of June 2021, the education and training sector had been allocated less than 3 percent of global stimulus packages. Much more funding will be needed for immediate learning recovery if countries are to avert the long-term damage to productivity and inclusion that they now face.

Learning Recovery as a Springboard to an Accelerated Learning Trajectory

Accelerating learning recovery has benefits that go well beyond short-term gains: it can give children the necessary foundations for a lifetime of learning, and it can help countries increase the efficiency, equity, and resilience of schooling. This can be achieved if countries build on investments made and lessons learned during the crisis—most notably, with a focus on six areas:

- Assessing student learning so instruction can be targeted to students’ learning levels and specific needs.

- Investing in digital learning opportunities for all students, ensuring that technology is fit for purpose and focused on enhancing human interactions.

- Reinforcing support that leverages the role of parents, families, and communities in children’s learning.

- Ensuring that teachers are supported and have access to practical, high-quality professional development opportunities, teaching guides and learning materials.

- Increasing the share of education in the national budget allocation of stimulus packages and tying it to investments mentioned above that can accelerate learning.

- Investing in evidence building - in particular, implementation research, to understand what works and how to scale what works to the system level.

It is time to shift from crisis response to learning recovery. We must make sure that investments and actions for learning recovery lay the foundations for more efficient, equitable, and resilient education systems—systems that truly deliver learning and well-being for all children and youth. Only then can we ensure learning continuity in the face of future disruption.

The report was produced as part of the Mission: Recovering Education 2021 , through which the World Bank , UNESCO , and UNICEF are focused on three priorities: bringing all children back to schools, recovering learning losses, and preparing and supporting teachers.

Get updates from Education for Global Development

Thank you for choosing to be part of the Education for Global Development community!

Your subscription is now active. The latest blog posts and blog-related announcements will be delivered directly to your email inbox. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Young Professional

Lead Economist

Education Researcher – UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti

Chief, Education – UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti

Chief of Education Policy Section, Division of Policies and Lifelong Learning Systems, UNESCO Education Sector

Director, Division for Policies and Lifelong Learning Systems, UNESCO Education Sector

Senior Economist

Senior Advisor, Statistics and Monitoring (Education) – UNICEF New York HQ

Senior Adviser Education, UNICEF Headquarters

Lead Economist, Education Global Practice

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Ways To Give . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

Ten of the biggest problems facing education

Aug 21, 2024

Many kids in the US head back to school this month. However, 250 million children around the world will be left out of the classroom. Revised for 2024, here are ten of the biggest problems facing education around the world.

Education can help us end poverty. It gives kids the skills they need to survive and thrive, opening the door to jobs, resources, and everything else that they need to live full, creative lives. In fact, UNESCO reports that if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, an estimated 171 million people could escape the cycle of poverty . And if all adults completed their secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

So why are 250 million children around the world currently out of school? We aren’t at a loss for reasons after the last few years. Here are the top ten problems facing education in 2024.

Learn more about how we're helping more people to learn… more

Last year we reached over 1.1 million people with our education programs. Get updates from classrooms around the world with our newsletter.

1. Conflict and violence

Conflict is one of the main reasons that kids are kept out of the classroom, with USAID estimating that half of all children not attending school are living in a conflict zone — some 125 million in total. To get a sense of this as a growing issue, in 2013, UNESCO reported that conflict was keeping 50 million students out of the classroom. Last year alone, 19 million children in Sudan were out of school due to renewed conflict .

Education is a lifeline during a conflict , protecting children from forced recruitment and potential attacks, while giving them a sense of normalcy in times that are anything but. It’s also a critical element in reducing the chance of future conflicts in certain areas. However, despite international humanitarian law, schools have become targets of attacks in many recent conflicts. Many parents have opted to keep their children at home as a result. However, these are not easy years to make up. According to UNESCO, the first two years of the Syria crisis erased all the country's educational progress since the start of the 21st century. Recovering these missed years also takes more time and effort, with many Syrian children requiring psychosocial care that hinders a "normal" learning curve. Unfortunately, as conflicts become more protracted, they are also threatening to create multiple lost generations.

When conflict meets the classroom: How does war affect education?

The consequences of conflict meeting the classroom.

2. Violence and bullying in the classroom

Violence can also carry over into the classroom. One UN study found that, while 102 countries have banned corporal punishment in schools, that ban isn’t always enforced. Many children have faced sexual violence and bullying in the classroom, either from fellow pupils or faculty and staff.

Children will often drop out of school altogether to avoid these situations. Even when they stay in school, the violence they experience can affect their social skills and self-esteem. It also has a negative impact on their educational achievement. Concern has addressed this head-on in Sierra Leone with our Safe Learning Model .

3. Climate change

Climate change is another major threat to education . Extreme weather events and related natural disasters destroy schools and other infrastructure key to accessing education (such as roads), and rebuilding damaged classrooms doesn’t happen overnight.

Climate change also affects children’s health, both physical and emotional, making it hard to keep up with school (and at times making it hard for teachers themselves to focus on delivering a quality education ). With climate change linked so tightly to poverty, it also leads families to withdraw their children from school when they can no longer afford the fees or need their children to contribute to the household income.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to education — and growing

Education is key to ending climate change — but climate change is also one of the biggest threats to education.

4. Harvest seasons and market days

In agricultural communities, the harvest is both a vital source of food and income. During these periods, children are often required to skip school to help their families harvest and sell crops. Sometimes they'll be out of school for weeks at a stretch. Families who make their living from farming may also have to move around if they have herds that graze, or to harvest crops planted in different areas. This is also disruptive for children and their education.

5. Unpaid and underqualified teachers

When governments are dysfunctional, public servants aren’t paid. That includes teachers. In some countries, teachers aren’t paid for months at a time. Many have no choice but to quit their posts to find other sources of income or are moved to other districts.

As a result, schools often struggle to find qualified teachers to replace those who have left. But, without qualified teachers in the classrooms, children suffer the most. In sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank estimates that the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 (with no updates yet as to how the pandemic may have affected these numbers). The World Bank adds that teachers in STEM are especially hard to come by in low-income countries.

What does Quality Education mean? Breaking down SDG #4

Breaking down Sustainable Development Goal #4.

6. The cost of supplies and uniforms

Although many countries provide free elementary education, attending school still comes at a cost. Parents and caretakers often pay for mandatory uniforms and other fees. School supplies are also necessary. These costs alone can keep students out of the classroom.

7. Being an older student

According to UNICEF, adolescents are twice as likely to be out of school compared to younger children. Globally, that means one in five students between the ages of 12 and 15 is out of school. As children get older, they face increased pressure to drop out so that they can work and contribute to their family income.

One solution we’ve adopted at Concern is to help those who didn't complete their education learn many of the things they missed out on, including financial literacy, business management, and vocational skills.

8. Being female

In many countries around the world, girls are more likely to be excluded from education than boys . This is despite all the efforts and progress made in recent years to increase the number of girls in school. According to UNESCO, up to 80% of school-aged girls who are currently out of school are unlikely to ever start. For boys, that same figure is just 16%. This rate is highest in emergency situations and fragile contexts.

Many schools have no toilets (let alone separate bathrooms for boys and girls). This usually means more missed days for girls when they get their period: The World Bank estimates that girls around the world miss up to 20% of their school days due to period poverty and stigma .

Girls may also be pressured to drop out of school to help out their family, as we mentioned above with regards to taking a job. However, in many countries where Concern works, they may also be forced out of school to get married. Girls who enter into an early or forced marriage usually leave school to take care of their new families. According to the UN, 33% of girls in low-income countries wed before the age of 18. Just over 11% get married before the age of 15. In most instances, marriage and having children mean the end of a girl’s formal education.

Child marriage and education: The blackboard wins over the bridal altar

For girls, child marriage (aka forced marriage) means the end of an education. Here's how a landmark ruling in Malawi is helping to keep girls in school.

9. Outbreaks and epidemics

We learned this the hard way with COVID-19. Even if the student body is healthy, they may be kept out of school if an epidemic has hit their area. Teachers might get sick, and families with sick parents may need their children to stay home and help out. Quarantines often go into effect.

The 2014-16 West African Ebola outbreak was a severe problem for education in countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone . Ebola put the education of 3 million children in these countries on hold. As a response, we worked with the governments of both countries to deliver lessons by radio. We also trained community members to work with small groups of children on basic reading and math. As schools reopened, we shifted our focus to helping children get back into classrooms safely, but many kids still had a lot of catching up to do.

10. Language and literacy barriers

Even if a child goes to school in the town where they were born and grew up their entire life, they may face a language barrier in the classroom between their mother tongue and the official lingua franca used in education systems. In Marsabit county, Kenya , the first language for most children is Borana. Once students start school, they must learn two new languages to understand their teachers: Swahili and English.

UNESCO estimates that 40% of school-aged children don’t have access to education in a language that they understand. This is especially difficult for students who have migrated to a new country, such as Syrian refugee children being hosted in Türkiye: Not only do they have to switch from Levantine Arabic to Turkish, but they also have to learn an entirely new alphabet.

This dovetails with literacy , another key issue in education. If a student struggles with reading (even in their mother tongue), it can have a ripple effect on their ability to learn in all other subjects. Many students drop out if they feel like they can’t keep up, either due to the quality of the teaching or to a special accommodation they need for their learning that can’t be made.

Concern’s work in education

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Our focus is on improving access to education, improving the quality of teaching and learning, and fostering safe learning environments

We've brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers. Last year alone, we reached 1.1 million people with education programs across ten countries.

Learn more about Concern's education programs.

Support Concern's work

Problems in education: Solved

Project Profile

Right to Learn

Safe Learning Model

Language barriers in the classroom: From mother tongue to national language

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Livelihoods

Health and nutrition

Climate and environment

Emergencies

Gender equality

Policy and advocacy

View all countries

View all publications

View all news

What we stand for

Our history

Why partner with Concern?

Public donations

Institutions and Partnerships

Trusts and foundations

Corporate donations

Donations over £1,000

How money is spent

Annual reports

How we are governed

Codes and policies

Supply chain

Through to 2

Hunger crisis appeal

Donating by post and phone

Weekly Lottery

Corporate giving

Emergency support

Concern Philanthropic Circle

Donate in memory

Leave a gift in your will

Wedding favours

Your donation and Gift Aid

Volunteer in Northern Ireland

Volunteer internationally

- Ration Challenge

London Marathon

London Winter Walk

Skydive for Concern

Start your own fundraiser

Charity fundraising tips

FAST Youth Ambassador

Knowledge Matters Magazine

Global Hunger Index

Learning Papers

Where we work

Research and reports

Latest news

Our annual report

How we raise money

Transparency and accountability

Donate today

Donate to Concern

Partner with us

Campaign with us

Buy an alternative gift

Other ways to support

Events and challenges

Schools and youth

Our Northern Ireland shops

Knowledge Hub

Knowledge Hub resources

- Debating at school

- Volunteer with us

- Job vacancies

10 of the biggest problems facing education

Children across the UK are heading back to school in the coming weeks. However, 250 million children around the world will be left out of the classroom. Revised for 2024, here are 10 of the biggest problems facing education around the world.

Education can help us end poverty. It gives kids the skills they need to survive and thrive, opening the door to jobs, resources, and everything else that they need to live full, creative lives. In fact, UNESCO reports that if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, an estimated 171 million people could escape the cycle of poverty . And if all adults completed their secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

So why are 250 million children around the world currently out of school? We aren’t at a loss for reasons after the last few years. Here are the top 10 problems facing education in 2024.

1. Conflict and violence

Conflict is one of the main reasons that kids are kept out of the classroom, with USAID estimating that half of all children not attending school are living in a conflict zone — some 125 million in total. To get a sense of this as a growing issue, in 2013, UNESCO reported that conflict was keeping 50 million students out of the classroom. Last year alone, 19 million children in Sudan were out of school due to renewed conflict.

Education is a lifeline during a conflict, protecting children from forced recruitment and potential attacks, while giving them a sense of normalcy in times that are anything but. It’s also a critical element in reducing the chance of future conflicts in certain areas. However, despite international humanitarian law, schools have become targets of attacks in many recent conflicts. Many parents have opted to keep their children at home as a result. However, these are not easy years to make up. According to UNESCO, the first two years of the Syria crisis erased all the country's educational progress since the start of the 21st century. Recovering these missed years also takes more time and effort, with many Syrian children requiring psychosocial care that hinders a "normal" learning curve. Unfortunately, as conflicts become more protracted, they are also threatening to create multiple lost generations.

2. Violence and bullying in the classroom

Violence can also carry over into the classroom. One UN study found that, while 102 countries have banned corporal punishment in schools, that ban isn’t always enforced. Many children have faced sexual violence and bullying in the classroom, either from fellow pupils or faculty and staff.

Children will often drop out of school altogether to avoid these situations. Even when they stay in school, the violence they experience can affect their social skills and self-esteem. It also has a negative impact on their educational achievement. Concern has addressed this head-on in Sierra Leone with our Safe Learning Model .

3. Climate change

Climate change is another major threat to education. Extreme weather events and related natural disasters destroy schools and other infrastructure key to accessing education (such as roads), and rebuilding damaged classrooms doesn’t happen overnight.

Climate change also affects children’s health, both physical and emotional, making it hard to keep up with school (and at times making it hard for teachers themselves to focus on delivering a quality education). With climate change linked so tightly to poverty, it also leads families to withdraw their children from school when they can no longer afford the fees or need their children to contribute to the household income.

4. Harvest seasons and market days

In agricultural communities, the harvest is both a vital source of food and income. During these periods, children are often required to skip school to help their families harvest and sell crops. Sometimes they'll be out of school for weeks at a stretch. Families who make their living from farming may also have to move around if they have herds that graze, or to harvest crops planted in different areas. This is also disruptive for children and their education.

5. Unpaid and underqualified teachers

When governments are dysfunctional, public servants aren’t paid. That includes teachers. In some countries, teachers aren’t paid for months at a time. Many have no choice but to quit their posts to find other sources of income or are moved to other districts.

As a result, schools often struggle to find qualified teachers to replace those who have left. But, without qualified teachers in the classrooms, children suffer the most. In sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank estimates that the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 (with no updates yet as to how the pandemic may have affected these numbers). The World Bank adds that teachers in STEM are especially hard to come by in low-income countries.

6. The cost of supplies and uniforms

Although many countries provide free primary education, attending school still comes at a cost. Parents and caretakers often pay for mandatory uniforms and other fees. School supplies are also necessary. These costs alone can keep students out of the classroom.

7. Being an older student

According to UNICEF, adolescents are twice as likely to be out of school compared to younger children. Globally, that means one in five students between the ages of 12 and 15 is out of school. As children get older, they face increased pressure to drop out so that they can work and contribute to their family income.

One solution we’ve adopted at Concern is to help those who didn't complete their education learn many of the things they missed out on, including financial literacy, business management, and vocational skills.

8. Being female

In many countries around the world, girls are more likely to be excluded from education than boys. This is despite all the efforts and progress made in recent years to increase the number of girls in school. According to UNESCO, up to 80% of school-aged girls who are currently out of school are unlikely to ever start. For boys, that same figure is just 16%. This rate is highest in emergency situations and fragile contexts.

Many schools have no toilets (let alone separate bathrooms for boys and girls). This usually means more missed days for girls when they get their period. The World Bank estimates that girls around the world miss up to 20% of their school days due to period poverty and stigma.

Girls may also be pressured to drop out of school to help out their family, as we mentioned above with regards to taking a job. However, in many countries where Concern works, they may also be forced out of school to get married. Girls who enter into an early or forced marriage usually leave school to take care of their new families. According to the UN, 33% of girls in low-income countries wed before the age of 18. Just over 11% get married before the age of 15. In most instances, marriage and having children mean the end of a girl’s formal education.

9. Outbreaks and epidemics

We learned this the hard way with COVID-19. Even if the student body is healthy, they may be kept out of school if an epidemic has hit their area. Teachers might get sick, and families with sick parents may need their children to stay home and help out. Quarantines often go into effect.

The 2014-16 West African Ebola outbreak was a severe problem for education in countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone . Ebola put the education of 3 million children in these countries on hold. As a response, we worked with the governments of both countries to deliver lessons by radio. We also trained community members to work with small groups of children on basic reading and maths. As schools reopened, we shifted our focus to helping children get back into classrooms safely, but many kids still had a lot of catching up to do.

10. Language and literacy barriers

Even if a child goes to school in the town where they were born and grew up their entire life, they may face a language barrier in the classroom between their mother tongue and the official lingua franca used in education systems. In Marsabit county, Kenya , the first language for most children is Borana. Once students start school, they must learn two new languages to understand their teachers: Swahili and English.

UNESCO estimates that 40% of school-aged children don’t have access to education in a language that they understand. This is especially difficult for students who have migrated to a new country, such as Syrian refugee children being hosted in Türkiye : Not only do they have to switch from Levantine Arabic to Turkish, but they also have to learn an entirely new alphabet.

This dovetails with literacy, another key issue in education. If a student struggles with reading (even in their mother tongue), it can have a ripple effect on their ability to learn in all other subjects. Many students drop out if they feel like they can’t keep up, either due to the quality of the teaching or to a special accommodation they need for their learning that can’t be made.

Concern's work in education

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. We integrate our education programmes into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Our focus is on improving access to education, improving the quality of teaching and learning, and fostering safe learning environments

We've brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers. Last year alone, we reached 1.1 million people with education programmes across 10 countries.

Learn more about Concern's education programmes.

Problems in education, solved

Education - Safe Learning Model Research

The power of education and emotional support in Syria to avoid another ‘lost generation’

How has Covid-19 affected education?

Share your concern.

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions

How politics and the pandemic put schools in the line of fire

A previous version of this story incorrectly said that 39 percent of American children were on track in math. That is the percentage performing below grade level.

Test scores are down, and violence is up . Parents are screaming at school boards , and children are crying on the couches of social workers. Anger is rising. Patience is falling.

For public schools, the numbers are all going in the wrong direction. Enrollment is down. Absenteeism is up. There aren’t enough teachers, substitutes or bus drivers. Each phase of the pandemic brings new logistics to manage, and Republicans are planning political campaigns this year aimed squarely at failings of public schools.

Public education is facing a crisis unlike anything in decades, and it reaches into almost everything that educators do: from teaching math, to counseling anxious children, to managing the building.

Political battles are now a central feature of education, leaving school boards, educators and students in the crosshairs of culture warriors. Schools are on the defensive about their pandemic decision-making, their curriculums, their policies regarding race and racial equity and even the contents of their libraries. Republicans — who see education as a winning political issue — are pressing their case for more “parental control,” or the right to second-guess educators’ choices. Meanwhile, an energized school choice movement has capitalized on the pandemic to promote alternatives to traditional public schools.

“The temperature is way up to a boiling point,” said Nat Malkus, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank. “If it isn’t a crisis now, you never get to crisis.”

Experts reach for comparisons. The best they can find is the earthquake following Brown v. Board of Education , when the Supreme Court ordered districts to desegregate and White parents fled from their cities’ schools. That was decades ago.

Today, the cascading problems are felt acutely by the administrators, teachers and students who walk the hallways of public schools across the country. Many say they feel unprecedented levels of stress in their daily lives.

Remote learning, the toll of illness and death, and disruptions to a dependable routine have left students academically behind — particularly students of color and those from poor families. Behavior problems ranging from inability to focus in class all the way to deadly gun violence have gripped campuses. Many students and teachers say they are emotionally drained, and experts predict schools will be struggling with the fallout for years to come.

Teresa Rennie, an eighth-grade math and science teacher in Philadelphia, said in 11 years of teaching, she has never referred this many children to counseling.

“So many students are needy. They have deficits academically. They have deficits socially,” she said. Rennie said that she’s drained, too. “I get 45 minutes of a prep most days, and a lot of times during that time I’m helping a student with an assignment, or a child is crying and I need to comfort them and get them the help they need. Or there’s a problem between two students that I need to work with. There’s just not enough time.”

Many wonder: How deep is the damage?

Learning lost

At the start of the pandemic, experts predicted that students forced into remote school would pay an academic price. They were right.

“The learning losses have been significant thus far and frankly I’m worried that we haven’t stopped sinking,” said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

Some of the best data come from the nationally administered assessment called i-Ready, which tests students three times a year in reading and math, allowing researchers to compare performance of millions of students against what would be expected absent the pandemic. It found significant declines, especially among the youngest students and particularly in math.

The low point was fall 2020, when all students were coming off a spring of chaotic, universal remote classes. By fall 2021 there were some improvements, but even then, academic performance remained below historic norms.

Take third grade, a pivotal year for learning and one that predicts success going forward. In fall 2021, 38 percent of third-graders were below grade level in reading, compared with 31 percent historically. In math, 39 percent of students were below grade level, vs. 29 percent historically.

Damage was most severe for students from the lowest-income families, who were already performing at lower levels.

A McKinsey & Co. study found schools with majority-Black populations were five months behind pre-pandemic levels, compared with majority-White schools, which were two months behind. Emma Dorn, a researcher at McKinsey, describes a “K-shaped” recovery, where kids from wealthier families are rebounding and those in low-income homes continue to decline.

“Some students are recovering and doing just fine. Other people are not,” she said. “I’m particularly worried there may be a whole cohort of students who are disengaged altogether from the education system.”

A hunt for teachers, and bus drivers

Schools, short-staffed on a good day, had little margin for error as the omicron variant of the coronavirus swept over the country this winter and sidelined many teachers. With a severe shortage of substitutes, teachers had to cover other classes during their planning periods, pushing prep work to the evenings. San Francisco schools were so strapped that the superintendent returned to the classroom on four days this school year to cover middle school math and science classes. Classes were sometimes left unmonitored or combined with others into large groups of unglorified study halls.

“The pandemic made an already dire reality even more devastating,” said Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, referring to the shortages.

In 2016, there were 1.06 people hired for every job listing. That figure has steadily dropped, reaching 0.59 hires for each opening last year, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show. In 2013, there were 557,320 substitute teachers, the BLS reported. In 2020, the number had fallen to 415,510. Virtually every district cites a need for more subs.

It’s led to burnout as teachers try to fill in the gaps.

“The overall feelings of teachers right now are ones of just being exhausted, beaten down and defeated, and just out of gas. Expectations have been piled on educators, even before the pandemic, but nothing is ever removed,” said Jennifer Schlicht, a high school teacher in Olathe, Kan., outside Kansas City.

Research shows the gaps in the number of available educators are most acute in areas including special education and educators who teach English language learners, as well as substitutes. And all school year, districts have been short on bus drivers , who have been doubling up routes, and forcing late school starts and sometimes cancellations for lack of transportation.

Many educators predict that fed-up teachers will probably quit, exacerbating the problem. And they say political attacks add to the burnout. Teachers are under scrutiny over lesson plans, and critics have gone after teachers unions, which for much of the pandemic demanded remote learning.

“It’s just created an environment that people don’t want to be part of anymore,” said Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “People want to take care of kids, not to be accused and punished and criticized.”

Falling enrollment

Traditional public schools educate the vast majority of American children, but enrollment has fallen, a worrisome trend that could have lasting repercussions. Enrollment in traditional public schools fell to less than 49.4 million students in fall 2020 , a 2.7 percent drop from a year earlier .

National data for the current school year is not yet available. But if the trend continues, that will mean less money for public schools as federal and state funding are both contingent on the number of students enrolled. For now, schools have an infusion of federal rescue money that must be spent by 2024.

Some students have shifted to private or charter schools. A rising number , especially Black families , opted for home schooling. And many young children who should have been enrolling in kindergarten delayed school altogether. The question has been: will these students come back?

Some may not. Preliminary data for 19 states compiled by Nat Malkus, of the American Enterprise Institute, found seven states where enrollment dropped in fall 2020 and then dropped even further in 2021. His data show 12 states that saw declines in 2020 but some rebounding in 2021 — though not one of them was back to 2019 enrollment levels.

Joshua Goodman, associate professor of education and economics at Boston University, studied enrollment in Michigan schools and found high-income, White families moved to private schools to get in-person school. Far more common, though, were lower-income Black families shifting to home schooling or other remote options because they were uncomfortable with the health risks of in person.

“Schools were damned if they did, and damned if they didn’t,” Goodman said.

At the same time, charter schools, which are privately run but publicly funded, saw enrollment increase by 7 percent, or nearly 240,000 students, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. There’s also been a surge in home schooling. Private schools saw enrollment drop slightly in 2020-21 but then rebound this academic year, for a net growth of 1.7 percent over two years, according to the National Association of Independent Schools, which represents 1,600 U.S. schools.

Absenteeism on the rise

Even if students are enrolled, they won’t get much schooling if they don’t show up.

Last school year, the number of students who were chronically absent — meaning they have missed more than 10 percent of school days — nearly doubled from before the pandemic, according to data from a variety of states and districts studied by EveryDay Labs, a company that works with districts to improve attendance.

This school year, the numbers got even worse.

In Connecticut, for instance, the number of chronically absent students soared from 12 percent in 2019-20 to 20 percent the next year to 24 percent this year, said Emily Bailard, chief executive of the company. In Oakland, Calif., they went from 17.3 percent pre-pandemic to 19.8 percent last school year to 43 percent this year. In Pittsburgh, chronic absences stayed where they were last school year at about 25 percent, then shot up to 45 percent this year.

“We all expected that this year would look much better,” Bailard said. One explanation for the rise may be that schools did not keep careful track of remote attendance last year and the numbers understated the absences then, she said.

The numbers were the worst for the most vulnerable students. This school year in Connecticut, for instance, 24 percent of all students were chronically absent, but the figure topped 30 percent for English-learners, students with disabilities and those poor enough to qualify for free lunch. Among students experiencing homelessness, 56 percent were chronically absent.

Fights and guns

Schools are open for in-person learning almost everywhere, but students returned emotionally unsettled and unable to conform to normally accepted behavior. At its most benign, teachers are seeing kids who cannot focus in class, can’t stop looking at their phones, and can’t figure out how to interact with other students in all the normal ways. Many teachers say they seem younger than normal.

Amy Johnson, a veteran teacher in rural Randolph, Vt., said her fifth-graders had so much trouble being together that the school brought in a behavioral specialist to work with them three hours each week.

“My students are not acclimated to being in the same room together,” she said. “They don’t listen to each other. They cannot interact with each other in productive ways. When I’m teaching I might have three or five kids yelling at me all at the same time.”

That loss of interpersonal skills has also led to more fighting in hallways and after school. Teachers and principals say many incidents escalate from small disputes because students lack the habit of remaining calm. Many say the social isolation wrought during remote school left them with lower capacity to manage human conflict.

Just last week, a high-schooler in Los Angeles was accused of stabbing another student in a school hallway, police on the big island of Hawaii arrested seven students after an argument escalated into a fight, and a Baltimore County, Md., school resource officer was injured after intervening in a fight during the transition between classes.

There’s also been a steep rise in gun violence. In 2021, there were at least 42 acts of gun violence on K-12 campuses during regular hours, the most during any year since at least 1999, according to a Washington Post database . The most striking of 2021 incidents was the shooting in Oxford, Mich., that killed four. There have been already at least three shootings in 2022.

Back to school has brought guns, fighting and acting out

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security, which maintains its own database of K-12 school shootings using a different methodology, totaled nine active shooter incidents in schools in 2021, in addition to 240 other incidents of gunfire on school grounds. So far in 2022, it has recorded 12 incidents. The previous high, in 2019, was 119 total incidents.

David Riedman, lead researcher on the K-12 School Shooting Database, points to four shootings on Jan. 19 alone, including at Anacostia High School in D.C., where gunshots struck the front door of the school as a teen sprinted onto the campus, fleeing a gunman.

Seeing opportunity

Fueling the pressure on public schools is an ascendant school-choice movement that promotes taxpayer subsidies for students to attend private and religious schools, as well as publicly funded charter schools, which are privately run. Advocates of these programs have seen the public system’s woes as an excellent opportunity to push their priorities.

EdChoice, a group that promotes these programs, tallies seven states that created new school choice programs last year. Some are voucher-type programs where students take some of their tax dollars with them to private schools. Others offer tax credits for donating to nonprofit organizations, which give scholarships for school expenses. Another 15 states expanded existing programs, EdChoice says.

The troubles traditional schools have had managing the pandemic has been key to the lobbying, said Michael McShane, director of national research for EdChoice. “That is absolutely an argument that school choice advocates make, for sure.”

If those new programs wind up moving more students from public to private systems, that could further weaken traditional schools, even as they continue to educate the vast majority of students.

Kevin G. Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado, who opposes school choice programs, sees the surge of interest as the culmination of years of work to undermine public education. He is both impressed by the organization and horrified by the results.

“I wish that organizations supporting public education had the level of funding and coordination that I’ve seen in these groups dedicated to its privatization,” he said.

A final complication: Politics

Rarely has education been such a polarizing political topic.

Republicans, fresh off Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia governor’s race, have concluded that key to victory is a push for parental control and “parents rights.” That’s a nod to two separate topics.

First, they are capitalizing on parent frustrations over pandemic policies, including school closures and mandatory mask policies. The mask debate, which raged at the start of the school year, got new life this month after Youngkin ordered Virginia schools to allow students to attend without face coverings.

The notion of parental control also extends to race, and objections over how American history is taught. Many Republicans also object to school districts’ work aimed at racial equity in their systems, a basket of policies they have dubbed critical race theory. Critics have balked at changes in admissions to elite school in the name of racial diversity, as was done in Fairfax, Va. , and San Francisco ; discussion of White privilege in class ; and use of the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which suggests slavery and racism are at the core of American history.

“Everything has been politicized,” said Domenech, of AASA. “You’re beside yourself saying, ‘How did we ever get to this point?’”

Part of the challenge going forward is that the pandemic is not over. Each time it seems to be easing, it returns with a variant vengeance, forcing schools to make politically and educationally sensitive decisions about the balance between safety and normalcy all over again.

At the same time, many of the problems facing public schools feed on one another. Students who are absent will probably fall behind in learning, and those who fall behind are likely to act out.

A similar backlash exists regarding race. For years, schools have been under pressure to address racism in their systems and to teach it in their curriculums, pressure that intensified after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Many districts responded, and that opened them up to countervailing pressures from those who find schools overly focused on race.

Some high-profile boosters of public education are optimistic that schools can move past this moment. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona last week promised, “It will get better.” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said, “If we can rebuild community-education relations, if we can rebuild trust, public education will not only survive but has a real chance to thrive.”

But the path back is steep, and if history is a guide, the wealthiest schools will come through reasonably well, while those serving low-income communities will struggle. Steve Matthews, superintendent of the 6,900-student Novi Community School District in Michigan, just northwest of Detroit, said his district will probably face a tougher road back than wealthier nearby districts that are, for instance, able to pay teachers more.

“Resource issues. Trust issues. De-professionalization of teaching is making it harder to recruit teachers,” he said. “A big part of me believes schools are in a long-term crisis.”

Valerie Strauss contributed to this report.

The pandemic’s impact on education

The latest: Updated coronavirus booster shots are now available for children as young as 5 . To date, more than 10.5 million children have lost one or both parents or caregivers during the coronavirus pandemic.

In the classroom: Amid a teacher shortage, states desperate to fill teaching jobs have relaxed job requirements as staffing crises rise in many schools . American students’ test scores have even plummeted to levels unseen for decades. One D.C. school is using COVID relief funds to target students on the verge of failure .

Higher education: College and university enrollment is nowhere near pandemic level, experts worry. ACT and SAT testing have rebounded modestly since the massive disruptions early in the coronavirus pandemic, and many colleges are also easing mask rules .

DMV news: Most of Prince George’s students are scoring below grade level on district tests. D.C. Public School’s new reading curriculum is designed to help improve literacy among the city’s youngest readers.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What’s It Like To Be a Teacher in America Today?

3. problems students are facing at public k-12 schools, table of contents.

- Problems students are facing

- A look inside the classroom

- How teachers are experiencing their jobs

- How teachers view the education system

- Satisfaction with specific aspects of the job

- Do teachers feel trusted to do their job well?

- Likelihood that teachers will change jobs

- Would teachers recommend teaching as a profession?

- Reasons it’s so hard to get everything done during the workday

- Staffing issues

- Balancing work and personal life

- How teachers experience their jobs

- Lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Major problems at school

- Discipline practices

- Policies around cellphone use

- Verbal abuse and physical violence from students

- Addressing behavioral and mental health challenges

- Teachers’ interactions with parents

- K-12 education and political parties

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

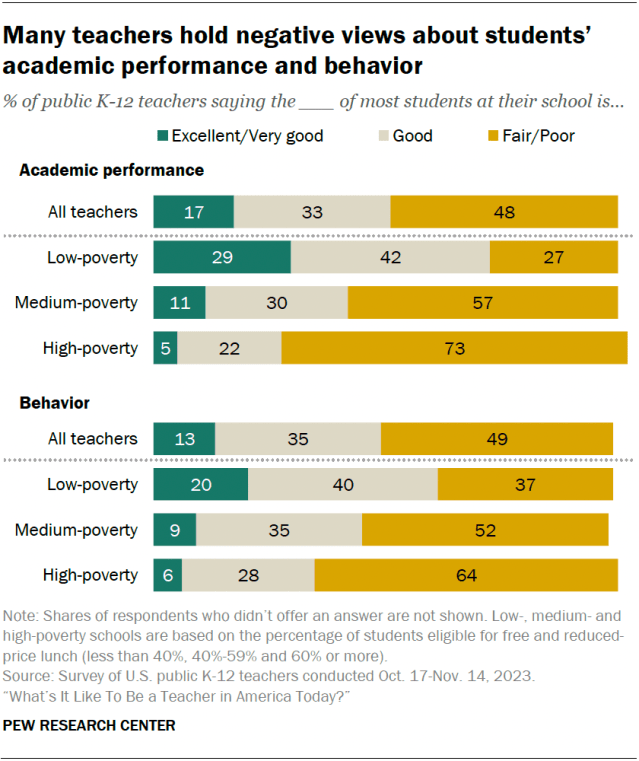

We asked teachers about how students are doing at their school. Overall, many teachers hold negative views about students’ academic performance and behavior.

- 48% say the academic performance of most students at their school is fair or poor; a third say it’s good and only 17% say it’s excellent or very good.

- 49% say students’ behavior at their school is fair or poor; 35% say it’s good and 13% rate it as excellent or very good.

Teachers in elementary, middle and high schools give similar answers when asked about students’ academic performance. But when it comes to students’ behavior, elementary and middle school teachers are more likely than high school teachers to say it’s fair or poor (51% and 54%, respectively, vs. 43%).

Teachers from high-poverty schools are more likely than those in medium- and low-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are fair or poor.

The differences between high- and low-poverty schools are particularly striking. Most teachers from high-poverty schools say the academic performance (73%) and behavior (64%) of most students at their school are fair or poor. Much smaller shares of teachers from low-poverty schools say the same (27% for academic performance and 37% for behavior).

In turn, teachers from low-poverty schools are far more likely than those from high-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are excellent or very good.

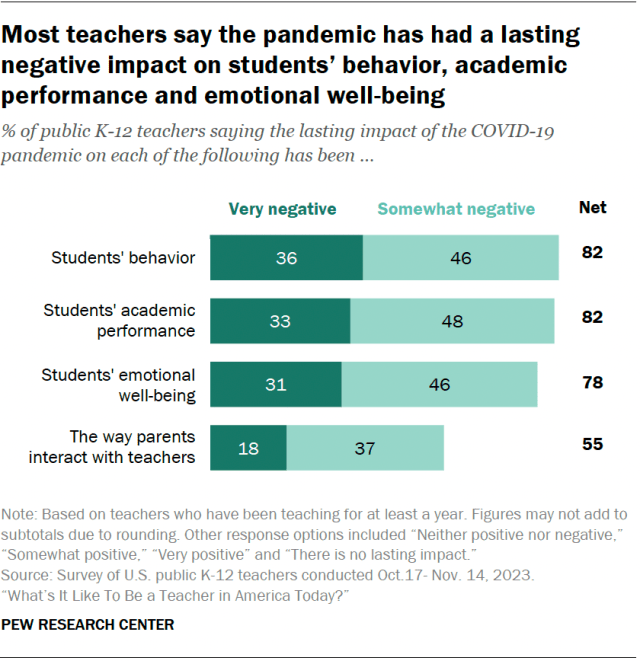

Among those who have been teaching for at least a year, about eight-in-ten teachers say the lasting impact of the pandemic on students’ behavior, academic performance and emotional well-being has been very or somewhat negative. This includes about a third or more saying that the lasting impact has been very negative in each area.

Shares ranging from 11% to 15% of teachers say the pandemic has had no lasting impact on these aspects of students’ lives, or that the impact has been neither positive nor negative. Only about 5% say that the pandemic has had a positive lasting impact on these things.

A smaller majority of teachers (55%) say the pandemic has had a negative impact on the way parents interact with teachers, with 18% saying its lasting impact has been very negative.

These results are mostly consistent across teachers of different grade levels and school poverty levels.

When we asked teachers about a range of problems that may affect students who attend their school, the following issues top the list:

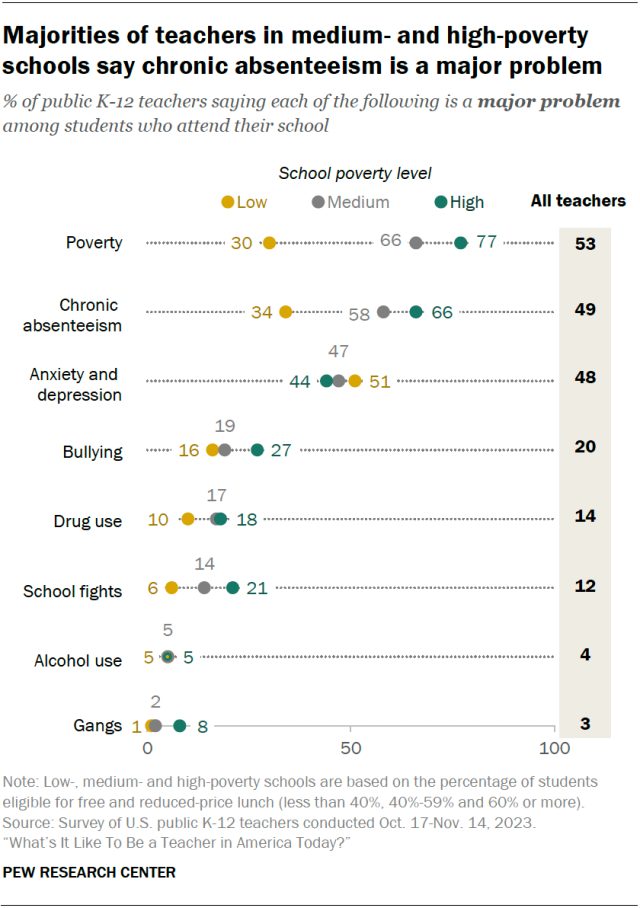

- Poverty (53% say this is a major problem at their school)

- Chronic absenteeism – that is, students missing a substantial number of school days (49%)

- Anxiety and depression (48%)

One-in-five say bullying is a major problem among students at their school. Smaller shares of teachers point to drug use (14%), school fights (12%), alcohol use (4%) and gangs (3%).

Differences by school level

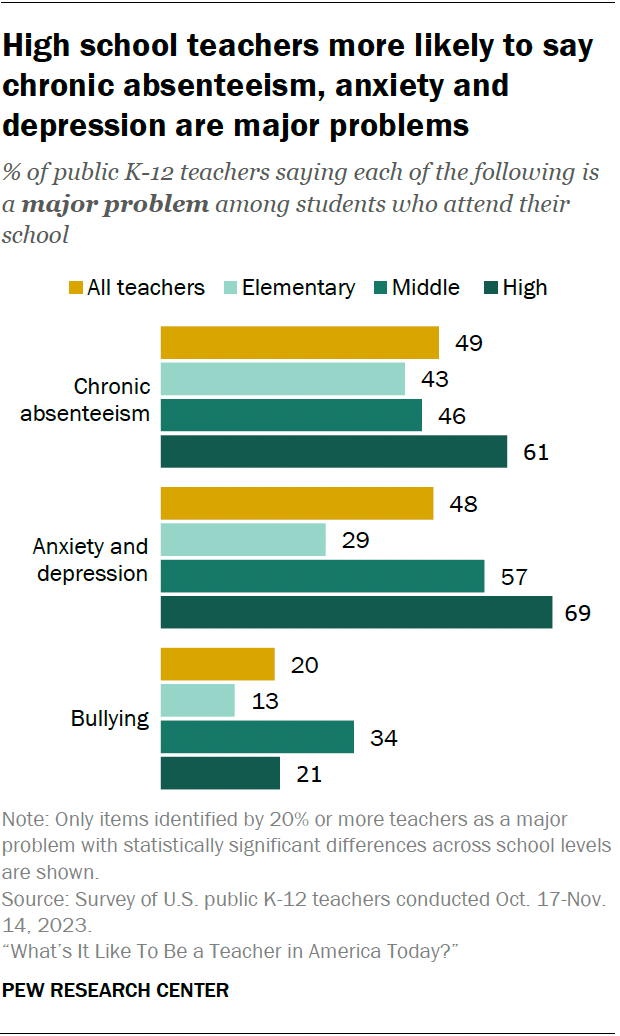

Similar shares of teachers across grade levels say poverty is a major problem at their school, but other problems are more common in middle or high schools:

- 61% of high school teachers say chronic absenteeism is a major problem at their school, compared with 43% of elementary school teachers and 46% of middle school teachers.

- 69% of high school teachers and 57% of middle school teachers say anxiety and depression are a major problem, compared with 29% of elementary school teachers.

- 34% of middle school teachers say bullying is a major problem, compared with 13% of elementary school teachers and 21% of high school teachers.

Not surprisingly, drug use, school fights, alcohol use and gangs are more likely to be viewed as major problems by secondary school teachers than by those teaching in elementary schools.

Differences by poverty level

Teachers’ views on problems students face at their school also vary by school poverty level.

Majorities of teachers in high- and medium-poverty schools say chronic absenteeism is a major problem where they teach (66% and 58%, respectively). A much smaller share of teachers in low-poverty schools say this (34%).

Bullying, school fights and gangs are viewed as major problems by larger shares of teachers in high-poverty schools than in medium- and low-poverty schools.

When it comes to anxiety and depression, a slightly larger share of teachers in low-poverty schools (51%) than in high-poverty schools (44%) say these are a major problem among students where they teach.

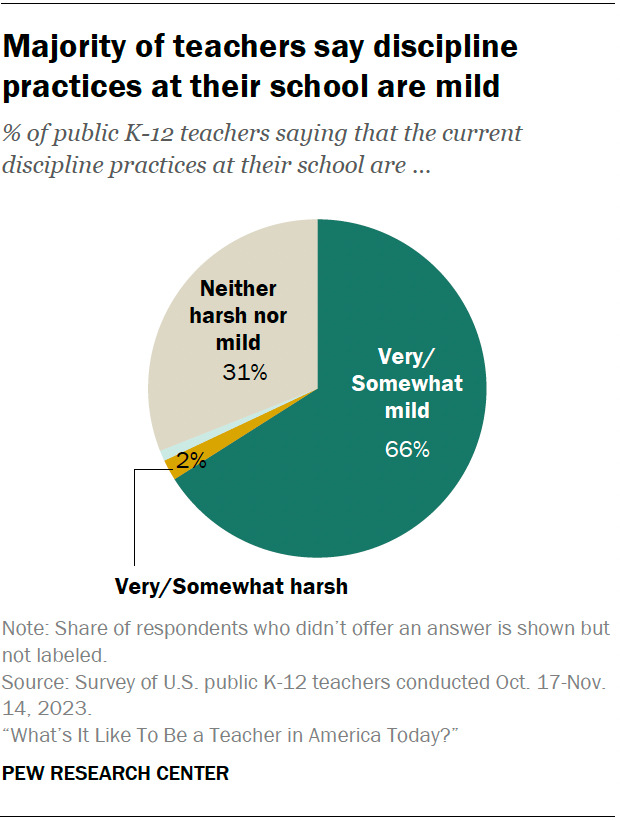

About two-thirds of teachers (66%) say that the current discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat mild – including 27% who say they’re very mild. Only 2% say the discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat harsh, while 31% say they are neither harsh nor mild.

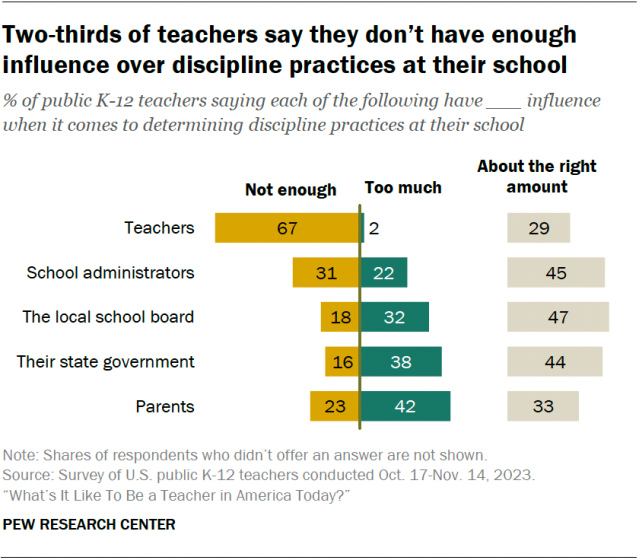

We also asked teachers about the amount of influence different groups have when it comes to determining discipline practices at their school.

- 67% say teachers themselves don’t have enough influence. Very few (2%) say teachers have too much influence, and 29% say their influence is about right.

- 31% of teachers say school administrators don’t have enough influence, 22% say they have too much, and 45% say their influence is about right.

- On balance, teachers are more likely to say parents, their state government and the local school board have too much influence rather than not enough influence in determining discipline practices at their school. Still, substantial shares say these groups have about the right amount of influence.

Teachers from low- and medium-poverty schools (46% each) are more likely than those in high-poverty schools (36%) to say parents have too much influence over discipline practices.

In turn, teachers from high-poverty schools (34%) are more likely than those from low- and medium-poverty schools (17% and 18%, respectively) to say that parents don’t have enough influence.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Education & Politics

5 facts about child care costs in the U.S.

Most hispanic americans say increased representation would help attract more young hispanics to stem, most americans back cellphone bans during class, but fewer support all-day restrictions, a look at historically black colleges and universities in the u.s., key facts about public school teachers in the u.s., most popular, report materials.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Trade Schools, Colleges and Universities

Join Over 1.5 Million People We've Introduced to Awesome Schools Since 2001

Trade Schools Home > Articles > Issues in Education

Major Issues in Education: Hot Topics

By Publisher | Last Updated August 29, 2024

In America, issues in education are big topics of discussion, both in the news media and among the general public. The current education system is beset by a wide range of challenges, from cuts in government funding to changes in disciplinary policies—and much more. Everyone agrees that providing high-quality education for our citizens is a worthy ideal. However, there are many diverse viewpoints about how that should be accomplished. And that leads to highly charged debates, with passionate advocates on both sides.

Understanding education issues is important for students, parents, and taxpayers. By being well-informed, you can contribute valuable input to the discussion. You can also make better decisions about what causes you will support or what plans you will make for your future.

This article provides detailed information on many of today's most relevant post-secondary education issues.

7 Big Issues in Higher Education

1. Student loan forgiveness

Here's how the American public education system works: Students attend primary and secondary school at no cost. They have the option of going on to post-secondary training (which, for most students, is not free). So, with costs rising at both public and private institutions of higher learning, student loan debt is one of the most prominent issues in education today. Students who graduated from college in 2022 came out with an average debt load of $37,338. As a whole, Americans owe over $1.7 trillion in student loans.

Currently, students who have received certain federal student loans and are on income-driven repayment plans can qualify to have their remaining balance forgiven if they haven't repaid the loan in full after 20 to 25 years, depending on the plan. Additionally, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program allows qualified borrowers who go into public service careers (such as teaching, government service, social work, or law enforcement) to have their student debt canceled after ten years.

However, potential changes are in the works. The Biden-Harris Administration is working to support students and make getting a post-secondary education more affordable. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Education provided more than $17 billion in loan relief to over 700,000 borrowers. Meanwhile, a growing number of Democrats are advocating for free college as an alternative to student loans.

2. Completion rates

The large number of students who begin post-secondary studies but do not graduate continues to be an issue. According to a National Student Clearinghouse Research Center report , the overall six-year college completion rate for the cohort entering college in 2015 was 62.2 percent. Around 58 percent of students completed a credential at the same institution where they started their studies, and about another 8 percent finished at a different institution.

Completion rates are increasing, but there is still concern over the significant percentage of college students who do not graduate. Almost 9 percent of students who began college in 2015 had still not completed a degree or certificate six years later. Over 22 percent of them had dropped out entirely.

Significant costs are associated with starting college but not completing it. Many students end up weighed down by debt, and those who do not complete their higher education are less able to repay loans. Plus, students who do not complete college miss out on the formal credentials that could lead to higher earnings. Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in 2023, students who begin college but do not complete a degree have median weekly earnings of $992. By contrast, associate degree holders have median weekly wages of $1,058, and bachelor's degree recipients have median weekly earnings of $1,493.

Students leave college for many reasons, but chief among them is money. To mitigate that, some institutions have implemented small retention or completion grants. Such grants are for students who are close to graduating, have financial need, have used up all other sources of aid, owe a modest amount, and are at risk of dropping out due to lack of funds. One study found that around a third of the institutions that implemented such grants noted higher graduation rates among grant recipients.

3. Student mental health

Mental health challenges among students are a growing concern. A survey by the American College Health Association in the spring of 2019 found that over two-thirds of college students had experienced "overwhelming anxiety" within the previous 12 months. Almost 45 percent reported higher-than-average stress levels.

Anxiety, stress, and depression were the most common concerns among students who sought treatment. The 2021 report by the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) noted that the average number of appointments students need has increased by 20 percent.

And some schools are struggling to keep up. A 2020 report found that the average student-to-clinician ratio on U.S. campuses was 1,411 to 1. So, in some cases, suffering students face long waits for treatment.

4. Sexual assault