Are peaceful protests more effective than violent ones?

- Search Search

As unrest erupts across the world after the killing of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white police officer, even some peaceful protests have descended into chaos, calling into question the efficacy of violence when it comes to spurring social change.

“There’s certainly more evidence that peaceful protests are more successful because they build a wider coalition,” says Gordana Rabrenovic , associate professor of sociology and director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict.

Gordana Rabrenovic is an associate professor of sociology and director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Who’s responsible for inciting this violence—the protesters or the police—is another debate entirely. But, Rabrenovic says, one thing is clear: in order for a movement to gain support and inspire lasting change, peace and consensus are essential.

“Violence can scare away your potential allies. You need the people on the sidelines to say, ‘This is my issue, too,’” she says. “For the people who say, ‘All lives matter,’ that’s true, but not all lives are in danger. You need to convince them.”

Still, it’s not always easy, or even feasible, for groups of oppressed people to take this moral high road, Rabrenovic says.

“The system doesn’t work for them,” she says. “They may think the only way to deal with the system is to destroy it.”

Black people in the U.S. are not only three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, but they’re also less likely to be armed than white people during these interactions with police.

For Black people who experience violence at the hands of the people and institutions that are supposed to protect them, the question becomes: “If they use violence, why shouldn’t we use violence?” Rabrenovic says. “They know that violence works, otherwise they wouldn’t use it.”

Exactly how that violence manifests is another matter entirely, but, Rabrenovic says, one thing is almost always true: violence is the spark that ignites the movement.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s is one example. The overall ethos of Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement was peace. But the catalyst was violence—hundreds of years of lynchings, lawful inequality, and oppression.

In fact, peace was strategically used during the civil rights movement to emphasize the violence Black people in the U.S. endured. Protesters were intentionally peaceful to prevent any question of who started the violence and whether it was justified. The results were inarguable visuals of peaceful Black protesters being attacked by dogs and beaten by police.

“Even peaceful civil rights movements are violent because it’s violence that motivates people to take action,” Rabrenovic says. Translating a violent history into a peaceful future is the hard part.

“Violence might be the quickest way to achieve your goals, but in order to sustain your victory, you would need to use coercion and have some kind of apparatus in place that keeps people in constant fear of punishment,” she says. “And nobody wants to live like that.”

While the George Floyd protests are a good starting point, the protests alone aren’t enough to sustain an entire movement, Rabrenovic says. “We need to give people other tools.”

Voting is one example. “We need to vote,” she says. “The government is us.”

One could argue that for Black and other disenfranchised people in the U.S., voting seems futile . But Rabrenovic counters, “If voting didn’t work, there wouldn’t be voter suppression.”

“You can’t suppress everyone,” she says. “That’s why it’s important to build a wide coalition, to bring in as many people as you can.”

We can’t keep living with only ourselves in mind. We need each other, she says. And protests are only the beginning.

For media inquiries , please contact [email protected] .

Editor's Picks

After pain and perseverance, maddie vizza returns to lead northeastern women’s basketball team, conference champions abigail hassman and ben godish lead northeastern to ncaa cross country regionals, uniformed police reduced public sexual harassment in india more than undercover officers new research finds, why are the best new artists nominees at the grammys not that new, anne boleyn’s forgotten years in france: new book explores how politics may have sealed her fate, featured stories, who’s afraid of iambic pentameter not the northeastern shakespeare society, northeastern celebrates resilient master’s degree recipients in london, encourages grads to shape a better world, computational chemistry promises to upset traditional methods of chemical synthesis, iuds still ‘very safe’ in light of new research on breast cancer risk.

Recent Stories

Nonviolence

As a theologian, Martin Luther King reflected often on his understanding of nonviolence. He described his own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom , and in subsequent books and articles. “True pacifism,” or “nonviolent resistance,” King wrote, is “a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love” (King, Stride , 80). Both “morally and practically” committed to nonviolence, King believed that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom” (King, Stride , 79; Papers 5:422 ).

King was first introduced to the concept of nonviolence when he read Henry David Thoreau’s Essay on Civil Disobedience as a freshman at Morehouse College . Having grown up in Atlanta and witnessed segregation and racism every day, King was “fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system” (King, Stride , 73).

In 1950, as a student at Crozer Theological Seminary , King heard a talk by Dr. Mordecai Johnson , president of Howard University. Dr. Johnson, who had recently traveled to India , spoke about the life and teachings of Mohandas K. Gandhi . Gandhi, King later wrote, was the first person to transform Christian love into a powerful force for social change. Gandhi’s stress on love and nonviolence gave King “the method for social reform that I had been seeking” (King, Stride , 79).

While intellectually committed to nonviolence, King did not experience the power of nonviolent direct action first-hand until the start of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955. During the boycott, King personally enacted Gandhian principles. With guidance from black pacifist Bayard Rustin and Glenn Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation , King eventually decided not to use armed bodyguards despite threats on his life, and reacted to violent experiences, such as the bombing of his home, with compassion. Through the practical experience of leading nonviolent protest, King came to understand how nonviolence could become a way of life, applicable to all situations. King called the principle of nonviolent resistance the “guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method” ( Papers 5:423 ).

King’s notion of nonviolence had six key principles. First, one can resist evil without resorting to violence. Second, nonviolence seeks to win the “friendship and understanding” of the opponent, not to humiliate him (King, Stride , 84). Third, evil itself, not the people committing evil acts, should be opposed. Fourth, those committed to nonviolence must be willing to suffer without retaliation as suffering itself can be redemptive. Fifth, nonviolent resistance avoids “external physical violence” and “internal violence of spirit” as well: “The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him” (King, Stride , 85). The resister should be motivated by love in the sense of the Greek word agape , which means “understanding,” or “redeeming good will for all men” (King, Stride , 86). The sixth principle is that the nonviolent resister must have a “deep faith in the future,” stemming from the conviction that “The universe is on the side of justice” (King, Stride , 88).

During the years after the bus boycott, King grew increasingly committed to nonviolence. An India trip in 1959 helped him connect more intimately with Gandhi’s legacy. King began to advocate nonviolence not just in a national sphere, but internationally as well: “the potential destructiveness of modern weapons” convinced King that “the choice today is no longer between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence” ( Papers 5:424 ).

After Black Power advocates such as Stokely Carmichael began to reject nonviolence, King lamented that some African Americans had lost hope, and reaffirmed his own commitment to nonviolence: “Occasionally in life one develops a conviction so precious and meaningful that he will stand on it till the end. This is what I have found in nonviolence” (King, Where , 63–64). He wrote in his 1967 book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? : “We maintained the hope while transforming the hate of traditional revolutions into positive nonviolent power. As long as the hope was fulfilled there was little questioning of nonviolence. But when the hopes were blasted, when people came to see that in spite of progress their conditions were still insufferable … despair began to set in” (King, Where , 45). Arguing that violent revolution was impractical in the context of a multiracial society, he concluded: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that. The beauty of nonviolence is that in its own way and in its own time it seeks to break the chain reaction of evil” (King, Where , 62–63).

King, “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” 13 April 1960, in Papers 5:419–425 .

King, Stride Toward Freedom , 1958.

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

The Future of Nonviolent Resistance

- Erica Chenoweth

Select your citation format:

Over the past fifty years, nonviolent civil resistance has overtaken armed struggle as the most common form of mobilization used by revolutionary movements. Yet even as civil resistance reached a new peak of popularity during the 2010s, its effectiveness had begun to decline—even before the covid-19 pandemic brought mass demonstrations to a temporary halt in early 2020. This essay argues that the decreased success of nonviolent civil resistance was due not only to savvier state responses, but also to changes in the structure and capabilities of civil-resistance movements themselves. Perhaps counterintuitively, the coronavirus pandemic may have helped to address some of these underlying problems by driving movements to turn their focus back to relationship-building, grassroots organizing, strategy, and planning.

T he year 2019 saw what may have been the largest wave of mass, nonviolent antigovernment movements in recorded history. 1 Large-scale protests, strikes, and demonstrations erupted across dozens of countries on an unprecedented scale. While 2011 has been called the year of the protester, 2019 has an even greater claim to that title.

About the Author

Erica Chenoweth is Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights and International Affairs at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and a Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. This essay is adapted from their next book Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know, which is forthcoming from Oxford University Press .

View all work by Erica Chenoweth

In some cases, these uprisings yielded dramatic results. In April 2019, Omar al-Bashir—the Sudanese tyrant who had overseen the massacre of hundreds of thousands in Darfur, given sanctuary to jihadist groups in the 1990s, and terrorized opponents with mass arrests, torture, and summary executions—fell from power. Weeks later, Algeria’s president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who was seeking an unconstitutional fifth term in office, also fell, toppled by a popular uprising known as the Smile Revolution. In July 2019, the governor of Puerto Rico was forced to resign after hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans gathered in mass demonstrations and carried out work stoppages, demanding accountability for his ineptitude and mocking statements regarding victims of Hurricane Maria. And since October 2019, governments have fallen to popular protest movements in places as diverse as Iraq, Lebanon, and Bolivia. In Chile, protests against austerity measures forced the government into prolonged negotiations over its fiscal policies. In Hong Kong, the leaderless movement that emerged to resist a pro-Beijing extradition law bolstered its numbers and escalated its demands following a mismanaged and brutal crackdown, propelling prodemocracy parties to victory in November 2019 local-government elections. In the first serious [End Page 69] challenge to the legitimacy of the right-wing turn carried out by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, hundreds of thousands of Indians began taking part in a mass campaign to resist citizenship-registration plans that threaten to render millions of Indian Muslims stateless. And since 2017, the United States has experienced its own wave of mass movements mobilizing for racial justice, immigration justice, gun control, women’s rights, climate justice, LGBTQ rights, and Donald Trump’s impeachment or resignation, among other goals.

Within a few months, however, most of this street activity had ground to a halt. The global coronavirus pandemic—and government responses to it—forced people in early 2020 to abandon mass demonstrations. Taking advantage of this sudden lapse in conventional forms of popular resistance, a host of governments across the world have pushed forward divisive policies that range from the suspension of free speech to controversial judicial appointments to bans on immigrant or refugee admissions.

The interruption caused by the pandemic only added to a series of daunting challenges that have plagued mass movements in recent years. In fact, although nonviolent resistance campaigns reached a new peak of popularity over the past decade, their effectiveness had begun to decline even before the pandemic hit. The main culprit for this has been changes in the structure and capabilities of these movements themselves. Perhaps counterintuitively, the coronavirus pandemic may have helped to address some of these underlying problems by driving movements to turn their focus back to relationship-building, grassroots organizing, strategy, and developing narratives that resonate with a captive audience. And as 2020 continues to unfold, many movements—including those in the United States—have roared back with much greater strength and capacity for long-term transformation.

The Expansion of Nonviolent Resistance

Nonviolent resistance is a method of struggle in which unarmed people confront an adversary by using collective action—including protests, demonstrations, strikes, and noncooperation—to build power and achieve political goals. Sometimes called civil resistance, people power, unarmed struggle, or nonviolent action, nonviolent resistance has become a mainstay of political action across the globe. Armed struggle used to be the primary way in which movements fought for change from outside the political system. Today, campaigns in which people rely overwhelmingly on nonviolent resistance have replaced armed struggle as the most common approach to contentious action worldwide.

For example, over the period 1900–2019, analysts have identified a total of 628 maximalist mass campaigns (those that seek to remove the incumbent national leadership from power or create territorial independence [End Page 70] through secession or the expulsion of a foreign military occupation or colonial power). 2 Although liberation movements are often depicted as bands of gun-wielding rebels, fewer than half these campaigns (303) involved organized armed resistance. The other 325 relied overwhelmingly on nonviolent civil resistance. 3 Faced with dire circumstances, more people turn to nonviolent civil resistance than to violence—and this has become increasingly true over the past fifty years.

Why have people seeking political change increasingly been turning to civil resistance? There are a few possible reasons.

First, it may be that more people around the world have come to see nonviolent resistance as a legitimate and successful method for creating change—a factor addressed in greater detail below. Although nonviolent resistance is not yet universally understood or accepted, the preference [End Page 71] for nonviolent resistance has become more widespread. 4

Second, new information technology is making it easier to learn about events that previously went unreported. 5 As internet access expands, more and more people are consuming news online via newspaper websites, social media, private chatrooms, and more. People in Mongolia can read about, become inspired by, and learn from the deeds of people in Malawi. As an increasingly common and effective method of struggle, civil resistance may be drawing increased attention from news outlets and scholars around the globe. And with access to new channels of communication, people can also bypass formal gatekeepers to communicate directly with others whom they perceive as likeminded. Since elites can no longer control information as easily as they once could, news and information featuring ordinary people may be easier to find today.

Third, the market for violence is drying up. This is most strikingly obvious with regard to outside state support for armed groups, which fell off sharply with the breakup of the Soviet Union. During the Cold War, the United States and USSR armed and financed dozens of rebel groups across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. A changed global balance of power after 1991 functionally ended this competition-by-proxy.

Fourth, in the postwar era, wider segments of society have come to value and expect fairness, the protection of human rights, and the avoidance of needless violence. 6 This normative shift may have heightened popular interest in civil resistance as a way to advocate for human rights. 7 The horrors of war have become much more visible than in the past, while realistic alternatives are more clearly within reach. As Selina Gallo-Cruz points out, the post–Cold War rise in nonviolent resistance also coincided with the growing presence of international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) explicitly focused on sharing information about the theory and practice of nonviolent resistance, such as the Albert Einstein Institution, the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, Nonviolence International, and the Center for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies. 8

Fifth, more troublingly, people today may have new motivations to resist. Over the past decade, more and more democratic governments have faltered and reverted into authoritarianism. 9 In recent years, the erosion of democratic rights has provoked mass protest movements both in authoritarian countries such as Egypt, Hungary, and Turkey, and in [End Page 72] democracies such as Brazil, Poland, and the United States. With the advent of the Trump presidency, many people in the United States have begun to embrace the theory and knowledge of civil resistance—and to put these insights into action. And the U.S. retreat from a global democracy agenda—and indeed, the erosion of democratic institutions within the United States itself—has shaken confidence that established institutions are willing or able to manage urgent policy challenges such as racial justice, climate change, public health, and rising inequality. Throughout much of the world, youth populations are increasing, and these demographic pressures are producing growing demands for jobs, education, and opportunity. Record numbers of highly educated youth are unemployed in some places. Even before the covid-19 pandemic wreaked economic havoc around the world, popular expectations of economic justice and opportunity have clashed with disappointing realities in economies that have been weakened in the wake of the 2008 financial crash.

The massive growth of civil-resistance campaigns around the world is therefore both a sign of success and a sign of failure. The success is that so many people have come to believe that they can confront injustice using strategic nonviolent methods, while fewer are turning to armed action. The failure is that so many injustices remain—and so few institutions are equipped to address them—that the demand for civil resistance has increased.

The Record of Nonviolent Resistance

Without understanding the dynamics of civil resistance, it would be hard to make sense of the political world that we live in today. At the outset of 1989, the international system appeared to be organized entirely around powerful nation-states and the elites who governed them. The civil uprisings that toppled the Soviet-backed regimes of Central and Eastern Europe in that year marked the start of three decades of dramatic change. The Black-led anti-apartheid movement in South Africa succeeded in bringing down the country’s regime of legally enshrined racial discrimination, although racism, segregation, and economic inequality persist. A number of autocratic regimes in postcommunist Europe and Central Asia have succumbed to so-called color revolutions. Primarily peaceful resistance movements have deposed three Arab dictators and shaken the grip of several others.

All these shifts flowed—in whole or in part—from sustained grassroots civic action. Indeed, the third and fourth waves of democratization were driven to a large extent by bottom-up movements demanding that their governments expand individual political rights and be held accountable through fair elections, a free press, an impartial criminal-justice system, and so on. 10 [End Page 73]

Scholars of civil resistance generally define “success” as the overthrow of a government or territorial independence achieved because of a campaign within a year of its peak. 11 Among the 565 campaigns that have both begun and ended over the past 120 years, about 51 percent of the nonviolent campaigns have succeeded outright, while only about 26 percent of the violent ones have. Nonviolent resistance thus outperforms violence by a 2-to-1 margin. (Sixteen percent of the nonviolent campaigns and 12 percent of violent ones ended in limited success, while 33 percent of nonviolent campaigns and 61 percent of violent ones ultimately failed.) Moreover, in countries where civil-resistance campaigns took place, chances of democratic consolidation, periods of relative postconflict stability, and various quality-of-life indicators were higher after the conflict than in the countries that experienced civil war. 12

This holds true even when nonviolent campaigns faced down brutal autocrats. Contrary to popular belief, it is not the case that nonviolent campaigns emerge or win out mainly when the regimes they confront are politically weak, incompetent, or unwilling to employ mass violence. Once a mass movement arises and unsettles the status quo, most regimes confront unarmed protesters with brute force, only to see even larger numbers of demonstrators turn out to protest the brutality. 13 Besides, even when regime type, government repression, and military capacity are taken into account, nonviolent campaigns are still far more likely to succeed than violent resistance. 14 This is because they tend to be larger, more cross-cutting, and therefore more politically representative than armed movements. This provides numerous openings through which they can bring about defections, pulling the regime’s pillars of support out from under it at decisive moments. This happens when security forces refuse to follow orders to shoot at demonstrators, as in Serbia in 2000. Or it can happen when business or economic elites start responding to public pressure by voicing support for the movement, as numerous white business owners did in South Africa following waves of Black-led strikes, boycotts, and global sanctions initiated in support of the anti-apartheid movement. In other settings, important political players, such as powerful labor unions or professional associations, begin to stop cooperating with the regime, as happened during the Sudanese revolution of 2019. Basically, the larger the movement, the more likely it is to disrupt the status quo and induce defections that sever the regime from its major pillars of support. And nonviolent movements have the capacity to expand participation in ways that armed groups cannot. 15 The widespread view that only violent action can be strong and effective is deeply mistaken.

Of course, civil-resistance campaigns do not always usher in peace and prosperity. In Syria in 2011, dictator Bashar al-Assad responded to a nonviolent struggle by unleashing military force and even chemical weapons against his civilian population. The resulting conflict has [End Page 74] continued for nearly ten years now and has become the bloodiest civil war of the current century, forcing some three-million people to flee the country. In 2011, the U.S.-backed government of Bahrain crushed a nonviolent movement that tried to challenge the monarchy there. And in Ukraine, a people-power movement managed to push Russian-backed kleptocrat Viktor Yanukovych from power in February 2014—but rather than permitting Ukraine to move deeper into the European orbit, Russia seized the Ukrainian territory of Crimea and has fueled an ongoing and deadly war of secession in Ukraine’s east.

Nonviolent campaigns over the past ten years have succeeded less often than their historical counterparts. From the 1960s until about 2010, success rates for revolutionary nonviolent campaigns remained above 40 percent, climbing as high as 65 percent in the 1990s. But success rates for all revolutions have since declined, as shown in Figure 2. Since 2010, less than 34 percent of nonviolent revolutions and a mere 8 percent of violent ones have succeeded.

While governments have had greater success at beating down challenges to their authority, nonviolent resistance still outperformed violent resistance by a 4-to-1 margin. That is because armed confrontation has grown even less successful, continuing a downward trend that has been underway since the 1970s. These caveats notwithstanding, the last decade has seen a sharp decline in the success rate for civil resistance—reversing [End Page 75] much of the overall upward trend of the previous sixty years.

The past decade therefore presents a troubling paradox: Just as civil resistance has become the most common approach to challenging regimes, it has begun to grow less effective—at least in the short term.

What Has Changed?

The most tempting explanations for the decline in effectiveness of civil-resistance campaigns center on the changed environment within which they now operate.

First, movements may be facing more entrenched regimes—ones that have prevailed against repeated challenges by shoring up support from local allies and key constituencies; imprisoning prominent oppositionists; provoking opponents into using violence; stoking fears of foreign or imperial conspiracies; or obtaining diplomatic cover from powerful international supporters. The regimes in Belarus, Iran, Russia, Syria, Turkey, and Venezuela have proved especially resilient in the face of challenges from below. There is no doubt that activists who work in such settings are confronting grave difficulties. Yet this post hoc explanation for movement failure has its shortcomings. Many regimes—such as Bashir’s government in Sudan—are seen as immutable and resilient up until the moment that a nonviolent resistance movement topples them, after which observers claim that the regimes were weak after all. But over history, many once-stable autocratic regimes—such as Chile under Augusto Pinochet, East Germany under Erich Honecker, Egypt under Hosni Mubarak, and communist Poland—succumbed to nonviolent movements after skillful mobilizations that often marked the culmination of years of effort.

Second, governments may be learning and adapting to nonviolent challenges from below. 16 Several decades ago, authoritarian regimes frequently found themselves surprised by the sudden onset of mass nonviolent uprisings, and governments struggled to find ways to suppress these movements without triggering increased popular sympathy and support for the repressed. Elites may also have underestimated the potential of people power to seriously threaten their rule. Today, given the ample historical record of successful nonviolent campaigns, state actors are likelier to perceive such movements as genuinely threatening. Consequently, autocratic regimes have developed a repertoire of politically savvy approaches to repression. 17 One prominent strategy is to infiltrate movements and divide them from within. In this way, the authorities can provoke a nonviolent movement into using more militant tactics, including violence, before the movement has built a broad enough base to ensure its popular support and staying power.

Third, with the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the United States has accelerated its retreat from its global role as a superpower with a [End Page 76] prodemocracy agenda. Although many have critiqued this agenda as a form of neo-imperialism shrouded in liberalism, the liberal international order established by the U.S. and other leading Western nations also coincided with an expansion of human-rights regimes that produced governmental and nongovernmental watchdogs who named and shamed human-rights abuses. These trends may have opened space for political dissent in many countries around the world. 18 Daniel Ritter has argued that in the post–Cold War world, authoritarian regimes were particularly susceptible to nonviolent challenges from below because they needed to maintain the semblance of respect for human rights in order to appease their democratic allies and patrons. 19 For instance, Egypt’s dependence on foreign assistance meant that when revolution broke out in 2011, the Egyptian military was highly attuned to scrutiny from liberal democracies such as the United States. Without an activist United States—and, more broadly, without powerful champions of human rights who have real leverage or enforcement capacity vis-à-vis autocratic regimes—we would expect greater brutality against nonviolent dissidents.

That argument may have some merit. But it also it overstates the degree to which the United States has been a genuine champion of democracy and human rights around the world. After all, the United States has a long history of helping to install right-wing autocrats in the postwar period—including Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Iran, General Joseph Mobutu in Congo, General Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and others who came to power through U.S.-backed coups. The argument also overestimates the degree to which democratic patrons have real leverage over how their autocratic allies conduct their domestic affairs. Historically, the fate of nonviolent resistance campaigns has depended much more on their ability to build their power by securing mass participation, as well as defections among security forces and economic elites, than on the behavior of fickle foreign governments. 20

Therefore, upon deeper inspection, although it may be that states have begun to better anticipate and suppress nonviolent resistance, the two structural arguments have little support in the historical record. Instead, the most compelling explanations for the declining effectiveness of nonviolent campaigns lie in the changing nature of the campaigns themselves.

How Movements Have Changed

First, in terms of participation, civil-resistance campaigns have become somewhat smaller on average than in the past. There have certainly been impressive mass demonstrations in the years since 2010. In 2017 and 2019, millions of people turned out to protest against Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. And in Chile, the October 2019 uprising against the government of President Sebastián Piñera reportedly drew a million people nationwide. Yet despite the dramatic images of crowds [End Page 77] filling public spaces, recent movements on the whole, at their peaks, have actually been smaller than successful movements of the late 1980s and 1990s. In the 1980s, the average nonviolent campaign involved about 2 percent of the population in the country where it was underway. In the 1990s, the average campaign included a staggering 2.7 percent of the population. But since 2010, the average peak participation has been only 1.3 percent, continuing a decline that began in the 2000s. This is a crucial change. A mass uprising is more likely to succeed when it includes a larger proportion and a more diverse cross-section of a nation’s population.

Second, contemporary movements tend to over-rely on mass demonstrations while neglecting other techniques—such as general strikes and mass civil disobedience—that can more forcefully disrupt a regime’s stability. Because demonstrations and protests are what most people associate with civil resistance, those who seek change are increasingly launching these kinds of actions before they have developed real staying power or a strategy for transformation. Compared to other methods, street protests may be easier to organize or improvise on short notice. In the digital age, such actions can draw participants in large numbers even without any structured organizing coalition to carry out advanced planning and coordinate communication. 21 But mass demonstrations are not always the most effective way of applying pressure to elites, particularly when they are not sustained over time. Other techniques of noncooperation, such as general strikes and stay-at-homes, can be much more disruptive to economic life and thus elicit more immediate concessions. It is often quiet, behind-the-scenes planning and organizing that enable movements to mobilize in force over the long term, and to coordinate and sequence tactics in a way that builds participation, leverage, and power. 22 For the many contemporary movements organized around leaderless resistance, such capacities can be difficult to develop.

Very possibly related to movements’ overemphasis on public demonstrations and marches is a third important factor: Recent movements have increasingly relied on digital organizing, via social media in particular. 23 This creates both strengths and liabilities. On the one hand, digital organizing makes today’s movements very good at assembling participants en masse on short notice. 24 It allows people to communicate their grievances broadly, across audiences of thousands or even millions. It gives organizers outlets for mass communication that are not controlled by mainstream institutions or governments. But the resulting movements are less equipped to channel their numbers into effective organizations that can plan, negotiate, establish shared goals, build on past victories, and sustain their ability to disrupt a regime. 25 Some movements that have emerged from digital organizing have found ways to create long-term organizations. But even then, their initial reliance on [End Page 78] the internet has a dark side: Easier communication also means easier surveillance. Those in power can harness digital technologies to monitor, single out, and suppress dissidents. Autocrats have also exploited digital technologies not only to rally their own supporters, but also to spread misinformation, propaganda, and countermessaging.

This leads to the fourth factor that may be contributing to the decreased effectiveness of contemporary civil-resistance movements: Nonviolent movements increasingly embrace or tolerate fringes that become violent. 26 From the 1970s until 2010, the share of nonviolent movements with violent flanks remained between 30 and 35 percent. In 2010–19, it climbed to more than half.

Even when the overwhelming majority of activists remain nonviolent, civil-resistance movements that mix in some armed violence—such as street fighting with police or attacking counterprotesters—tend to be less successful in the end than movements that remain disciplined in rejecting violence. 27 This is because violence tends to increase indiscriminate repression against movement participants and sympathizers while making it harder for the movement to paint participants as innocent victims of this brutality. Entrenched regimes can cast violent skirmishers as threats to public order. In fact, governments often infiltrate movements to provoke them into adopting violence at the margins, thereby giving the regime justification for the use of heavy-handed tactics. What powerholders really fear is resilient, nonviolent, mass rebellion—which exposes as a lie their aura of invincibility while simultaneously removing any excuses for violent crackdowns.

Several clear lessons emerge from comparing contemporary movements to their historical antecedents. First, movements that engage in careful planning, organization, training, and coalition-building prior to mass mobilization are more likely to draw a large and diverse following than movements that take to the streets before hashing out a political program and strategy. Second, movements that grow in size and diversity are more likely to succeed—particularly if they are able to maintain momentum. Third, movements that do not rely solely on digital organizing techniques are more likely to build a sustainable following. And finally, movements that come up with strategies for maintaining unity and discipline under pressure may fare better than movements that leave these matters to chance.

Does Nonviolent Resistance Have a Future?

There is no doubt that the covid-19 pandemic has been a sharp and sudden blow to the dozens of ongoing civil-resistance movements around the world. Indeed, in the pandemic’s early months it became standard to see headlines in major newspapers announcing the end of protest as a result of social-distancing mandates combined with the expansion [End Page 79] of executive powers in an array of countries. 28 But as made clear by the widespread antiracism protests in the United States in response to the killing of Ahmaud Arbery by white vigilantes and the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd at the hands of police, the era of mass demonstrations is not about to end, in the United States or anywhere else.

Still, even as the causes that power movements remain alive, the global shutdown has provided opportunities for important stocktaking, regrouping, and planning for the next phase of protracted struggles for democracy and rights. Indeed, given the reduced success of recent movements, such regrouping and stock-taking may be essential if mass movements are to make meaningful progress. Movements’ future capacity to build people power from below depends on how they invest their time and resources during the global shutdown.

There is reason for hope in this regard. First, many of the measures now in common use by prodemocracy and progressive activists—mutual-aid pods, strikes, stay-at-homes, sick-ins, online teachins, and various expressions of solidarity with and collective support for frontline workers—are positive shifts in the movement landscape. In the United States alone, mutual-aid networks in New York, Boston, the Bay Area, and other cities have crowdsourced emergency relief funds, food, personal protective equipment, and errands; coordinated the distribution of money and vital supplies; and raised community awareness about the unequal effects of the pandemic (and government responses) on Black and brown communities in particular. Those networks strengthened communication networks, grassroots provision of public goods, and communal trust and reciprocity during the pandemic. These efforts were supercharged with the onset of the antiracism uprisings, with many mutual-aid networks immediately mobilizing donations to bail funds and other forms of community relief in the wake of a heavy-handed government response to mass protests.

Although such measures rarely make for eye-catching photos in the way that mass demonstrations do, they represent a new phase of tactical innovation. Through these efforts, movements are updating and renewing the outdated playbook that has led them to rely exclusively on protest at the expense of methods such as noncooperation and the development [End Page 80] of alternative institutions. From the Indian independence movement to Poland’s Solidarity to Black liberation groups in South Africa and the United States, movements have gained civic strength when they have developed alternative institutions to build self-sufficiency and address community problems that governments have neglected or ignored. Gandhi called this the “constructive program” and considered it one of the two pillars of his technique of satyagraha , equal in importance to noncooperation.

Of course, many protests continue—either in outright defiance of social-distancing measures or in spite of them. But this makes such actions all the more striking—and compelling. The fact that people are willing to risk their health to resist injustice raises awareness of the gravity and urgency of their claims. Elsewhere, people are experimenting with socially distant protests—including car caravans, pots-and-pans protests or cacerolazos , and even socially distant protests such as a 1,200-person action against Israeli premier Benjamin Netanyahu that took place in Tel Aviv in April 2020. And across the globe, essential workers—from warehouse employees to grocers to nurses at emergency departments and beyond—have used walk-outs, sick-ins, and strikes to demand safer workplace conditions, often yielding immediate concessions from employers in the forms of masks, gloves, and hazard pay. Work stoppages in the medical, grocery, tech, and meatpacking sectors and other forms of noncooperation put significant power in the hands of these workers, precisely because they are vital to keeping the food supply flowing, transport running, and public-health services in operation. Strikes and work stoppages among these workers are very difficult to combat without risking a major public backlash, creating a key vulnerability for governments.

Second, the pandemic may provide a much-needed pause for many activists and organizers who tend to move from one march to the next with very little time for reflection, strategy, or relationship-building. During lockdowns, movements have been able to step away from planning large-scale events and focus on building resilient coalitions with a greater capacity for bringing about lasting transformation. Many movements around the world have used the time to invest in planning longer-term strategies, building relationships among potential coalition partners, and developing training modules aimed at launching more effective challenges. Events such as Earth Day Live—a multiday online action for climate justice—brought together hundreds of organizations to share skills, strategies, and inspiration for global action on climate change. Movements such as Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, and the Sunrise Movement organized webinars to talk about the ways in which they could continue to promote climate action during lockdown. In the United States, movements fighting for racial justice, voting rights, and climate action convened skills-shares and teach-ins, helping to shine the light on the unequal effects of the pandemic on marginalized [End Page 81] communities, including African Americans. Such activities have helped to galvanize public awareness of urgent inequalities in a way that set the stage for much larger and more sustained collective action.

Finally, the pandemic is giving publics a view of the stark contrast between populists and autocrats on the one hand and liberal or social democrats on the other when it comes to how they respond to crises. The four top countries in terms of the number of reported coronavirus infections as of this writing in June 2020—the United States, Russia, Brazil, and the United Kingdom—are helmed by populist or authoritarian leaders whose handling of the pandemic has been disastrous. Instead of acting preemptively to prepare their publics for a protracted period of quarantine, making testing widely available, and prioritizing flattening the curve through timely and accurate information, leaders in these countries have denied or minimized the pandemic, invoked conspiracy theories to deflect blame, and stoked domestic political divisions—for instance, by calling on supporters to defy mayors and governors who advocated strict public-health mandates, or by blaming national crises on protesters fighting for racial justice.

These missteps with their deadly consequences may have sinister long-term implications, but they could also sharpen public awareness of the urgency of political change, reminding voters that mismanaged crises affect everyone living in the country. Many movements have already adjusted their frames to focus on the need for genuine democratic renewal in the face of government incompetence in responding to the pandemic, threats to civil rights, racism and ethnocentrism, and economic insecurity. In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro is facing his first real political crisis as his public-approval ratings plummet due to his flouting of global public-health recommendations. In Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega’s leadership failures have similarly provided prodemocracy activists with renewed motivation to push for change.

In February in Hong Kong, hospital workers went on strike to protest the government’s unwillingness to close the border with mainland China in order to stop the spread of the virus—echoing the earlier resistance to China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s independence. That strike forced the government to close all save three of its border checkpoints, demonstrating the power of noncooperation by essential workers. And at the end of May, thousands of Hong Kong protesters filled the streets in defiance of stay-at-home guidance to resist Beijing’s plans to push through a new national-security law that threatens to further tighten the mainland’s grip on Hong Kong. Movements fighting for climate justice have also adjusted their frames to reflect the growing concern that future pandemics could emerge as a result of climate inaction now. And the ongoing U.S. protests against racism and police violence are tied to the fact that African Americans have perished from coronavirus at much higher rates than whites—among other persistent social, political, and economic inequalities. Because the pandemic has already affected the [End Page 82] lives of billions of people worldwide, these messages are likely to resonate with a broader base now than they did before the crisis.

Thus, in spite of the recent setbacks for nonviolent campaigns around the world, 2020 need not represent the end of successful nonviolent resistance. Instead, the pandemic has served as a much-needed reset for movements around the world—and many of them have used the time wisely. [End Page 83]

The author thanks Sooyeon Kang and Christopher Wiley Shay for their contributions to the data collection, and participants in academic seminars at Columbia University, Wellesley College, and Harvard University for their useful feedback. I am also grateful to Zoe Marks for comments on a draft of this article, and to E.J. Graff for editorial assistance. Remaining errors are my own.

1. Erica Chenoweth et al., “This May Be the Largest Wave of Nonviolent Mass Movements in World History. What Comes Next?” Washington Post , Monkey Cage blog, 16 November 2019.

2. This count combines data from the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes Data Project (v. 1.3) with the Major Episodes of Contention Data Set. During the same time period, there have been thousands of campaigns pursuing other goals, such as women’s rights, labor rights, queer and LGBTI rights, environmental justice, economic justice, corporate accountability, peace, and various policy changes. The statistics presented in this essay focus primarily on maximalist campaigns. This is not because I am more interested in these campaigns, but because they constitute a more limited subset of mass movements for which figures are widely available. Data are available from the author on request.

3. About 40 percent of the nonviolent campaigns also involved a violent flank, which I address in later in this essay.

4. Erica Chenoweth, “Why is Nonviolent Resistance on the Rise?” Diplomatic Courier (28 June 2016).

5. Erica Chenoweth, “Why is Nonviolent Resistance on the Rise?”

6. Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York: Viking, 2011).

7. For more detail and some additional hypotheses, see Maciej Bartkowski, ed. Recovering Nonviolent History: Civil Resistance in Liberation Struggles (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2013).

8. Selina Gallo-Cruz, “Nonviolence Beyond the State: International NGOs and Local Nonviolent Mobilization,” International Sociology 34 (November 2019): 655–74.

9. See Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2020 report, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2020/leaderless-struggle-democracy .

10. Jonathan C. Pinckney, From Dissent to Democracy: The Promise and Perils of Civil Resistance Transitions (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Markus Bayer, Felix S. Bethke, and Daniel Lambach, “The Democratic Dividend of Nonviolent Resistance,” Journal of Peace Research 53 (November 2016): 758–71; Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011); Mauricio Rivera Celestino and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Fresh Carnations or All Thorn, No Rose? Nonviolent Campaigns and Transitions in Autocracies,” Journal of Peace Research 50 (May 2013): 385–400.

11. This definition of success is contested, although for practical purposes it is the most reliable to use in comparing across cases. Some research also focuses on longer-term successes, such as the expansion of democracy, rights, and stability.

12. Judith Stoddard, “How Do Major, Violent and Nonviolent Opposition Campaigns, Impact Predicted Life Expectancy at Birth?” Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 2, no. 2 (2013).

13. Brian Martin, Justice Ignited: The Dynamics of Backfire (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007); Lester R. Kurtz and Lee A. Smithey, eds. The Paradox of Repression and Nonviolent Movements (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2018).

14. Chenoweth and Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works , Chapter 3.

15. Chenoweth and Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works .

16. Erica Chenoweth, “Trends in Nonviolent Resistance and State Response: Is Violence Toward Civilian-Based Movements on the Rise?” Global Responsibility to Protect 9 (January 2017): 86–100.

17. Erica Chenoweth, “The Trump Administration’s Adoption of the Anti-Revolutionary Toolkit,” PS: Political Science and Politics 51 (January 2018): 19–20; Chenoweth, “Trends in Nonviolent Resistance and State Response.”

18. Kathryn Sikkink, Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21 st Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

19. Daniel P. Ritter, The Iron Cage of Liberalism: International Politics and Unarmed Revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

20. Chenoweth and Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works .

21. Zeynep Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

22. Chenoweth et al., “This May Be the Largest Wave.”

23. Linda Herrera, Revolution in the Age of Social Media: The Egyptian Popular Insurrection and the Internet (London: Verso, 2014).

24. Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas .

25. Asef Bayat, Revolution Without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017); George Lawson, Anatomies of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

26. See also Erica Chenoweth, “The Rise of Nonviolent Resistance,” PRIO Policy Brief 19 (2016); Chenoweth, “Why Is Nonviolent Resistance on the Rise?”

27. Omar Wasow, “Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion, and Voting,” American Political Science Review (forthcoming); Erica Chenoweth and Kurt Schock, “Do Contemporaneous Armed Challenges Affect the Outcomes of Mass Nonviolent Campaigns?” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 20 (December 2015): 427–51.

28. Evan Gerstmann,”How the COVID-19 Crisis is Threatening Freedom and Democracy Across the Globe,” Forbes , 12 April 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/evangerstmann/2020/04/12/how-the-covid-19-crisis-is-threatening-freedom-and-democracy-across-the-globe/#6dec63234f16 .

Copyright © 2020 National Endowment for Democracy and Johns Hopkins University Press

Further Reading

Volume 1, Issue 1

Tiananmen and Beyond: After the Massacre

The following text is based upon remarks presented by Wuer Kaixi in Washington, D.C. on 2 August 1989 at a meeting cosponsored by the Congressional Human Rights Foundation and the…

Volume 31, Issue 4

Crackdown: Hong Kong Faces Tiananmen 2.0

- Victoria Tin-bor Hui

Liberty flourished in Hong Kong, but the Chinese Communist Party has crushed it. Beijing wants “capitalism without freedom” in the city, but can there be one without the other?

Volume 25, Issue 3

The Maidan and Beyond: Who Were the Protesters?

Survey data reveal the makeup of the crowds in the Maidan and the factors that motivated them to take part in the protests.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

What’s ahead for U.S. foreign policy in ‘Trump 2.0’?

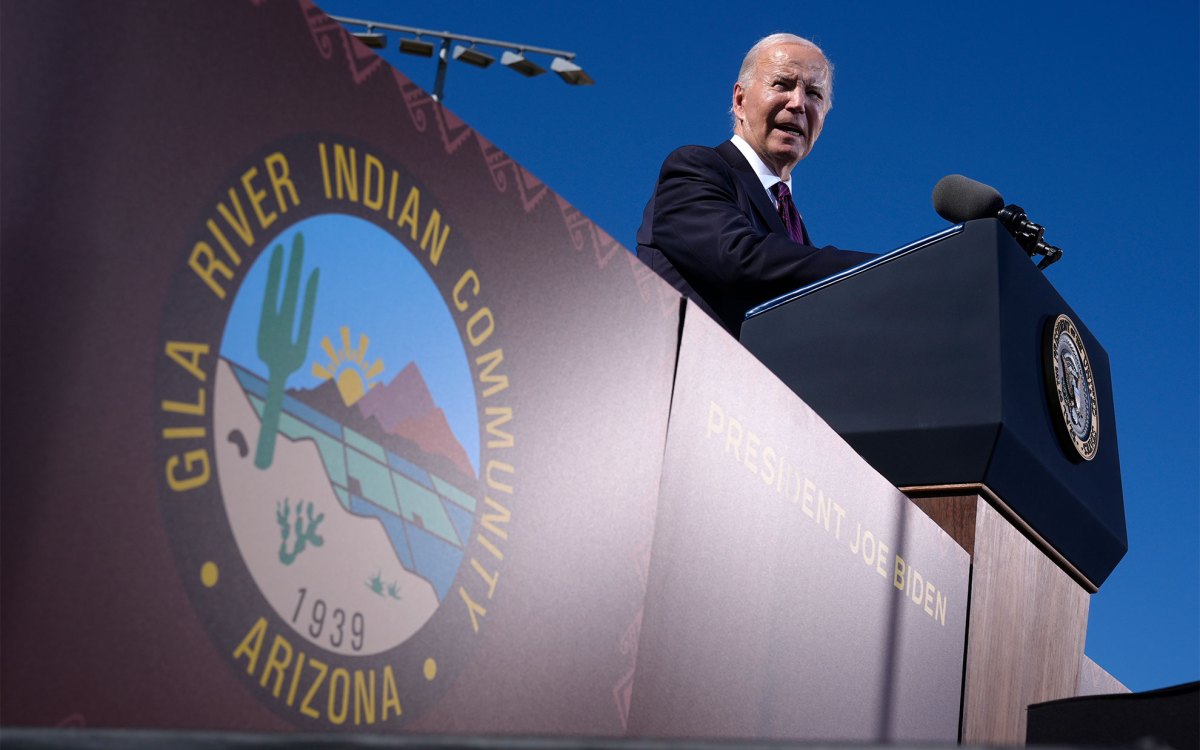

Many in Native communities applaud U.S. apology over boarding schools

Buttigieg urges focus on local, state projects that can win wide support

In her book, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,” Harvard Professor Erica Chenoweth explains why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people.

Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy

Nonviolent resistance proves potent weapon

Michelle Nicholasen

Weatherhead Center Communications

Erica Chenoweth discovers it is more successful in effecting change than violent campaigns

Recent research suggests that nonviolent civil resistance is far more successful in creating broad-based change than violent campaigns are, a somewhat surprising finding with a story behind it.

When Erica Chenoweth started her predoctoral fellowship at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in 2006, she believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. She had studied terrorism, civil war, and major revolutions — Russian, French, Algerian, and American — and suspected that only violent force had achieved major social and political change. But then a workshop led her to consider proving that violent resistance was more successful than the nonviolent kind. Since the question had never been addressed systematically, she and colleague Maria J. Stephan began a research project.

For the next two years, Chenoweth and Stephan collected data on all violent and nonviolent campaigns from 1900 to 2006 that resulted in the overthrow of a government or in territorial liberation. They created a data set of 323 mass actions. Chenoweth analyzed nearly 160 variables related to success criteria, participant categories, state capacity, and more. The results turned her earlier paradigm on its head — in the aggregate, nonviolent civil resistance was far more effective in producing change.

The Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA) sat down with Chenoweth, a new faculty associate who returned to the Harvard Kennedy School this year as professor of public policy, and asked her to explain her findings and share her goals for future research. Chenoweth is also the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: In your co-authored book, “ Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict ,” you explain clearly why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people — in part it’s because there’s a much lower barrier to participation compared with picking up a weapon. Based on the cases you have studied, what are the key elements necessary for a successful nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: I think it really boils down to four different things. The first is a large and diverse participation that’s sustained.

The second thing is that [the movement] needs to elicit loyalty shifts among security forces in particular, but also other elites. Security forces are important because they ultimately are the agents of repression, and their actions largely decide how violent the confrontation with — and reaction to — the nonviolent campaign is going to be in the end. But there are other security elites, economic and business elites, state media. There are lots of different pillars that support the status quo, and if they can be disrupted or coerced into noncooperation, then that’s a decisive factor.

The third thing is that the campaigns need to be able to have more than just protests; there needs to be a lot of variation in the methods they use.

The fourth thing is that when campaigns are repressed — which is basically inevitable for those calling for major changes — they don’t either descend into chaos or opt for using violence themselves. If campaigns allow their repression to throw the movement into total disarray or they use it as a pretext to militarize their campaign, then they’re essentially co-signing what the regime wants — for the resisters to play on its own playing field. And they’re probably going to get totally crushed.

In 2006, Erica Chenoweth believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. Then she was challenged to prove it.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

WCFIA: Is there any way to resist or protest without making yourself more vulnerable?

CHENOWETH: People have done things like bang pots and pans or go on electricity strikes or something otherwise disruptive that imposes costs on the regime even while people aren’t outside. Staying inside for an extended period equates to a general strike. Even limited strikes are very effective. There were limited and general strikes in Tunisia and Egypt during their uprisings and they were critical.

WCFIA: A general strike seems like a personally costly way to protest, especially if you just stop working or stop buying things. Why are they effective?

CHENOWETH: This is why preparation is so essential. Where campaigns have used strikes or economic noncooperation successfully, they’ve often spent months preparing by stockpiling food, coming up with strike funds, or finding ways to engage in community mutual aid while the strike is underway. One good example of that comes from South Africa. The anti-apartheid movement organized a total boycott of white businesses, which meant that black community members were still going to work and getting a paycheck from white businesses but were not buying their products. Several months of that and the white business elites were in total crisis. They demanded that the apartheid government do something to alleviate the economic strain. With the rise of the reformist Frederik Willem de Klerk within the ruling party, South African leader P.W. Botha resigned. De Klerk was installed as president in 1989, leading to negotiations with the African National Congress [ANC] and then to free elections, where the ANC won overwhelmingly. The reason I bring the case up is because organizers in the black townships had to prepare for the long term by making sure that there were plenty of food and necessities internally to get people by, and that there were provisions for things like Christmas gifts and holidays.

WCFIA: How important is the overall number of participants in a nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: One of the things that isn’t in our book, but that I analyzed later and presented in a TEDx Boulder talk in 2013 , is that a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign: just 3.5 percent. That sounds like a really small number, but in absolute terms it’s really an impressive number of people. In the U.S., it would be around 11.5 million people today. Could you imagine if 11.5 million people — that’s about three times the size of the 2017 Women’s March — were doing something like mass noncooperation in a sustained way for nine to 18 months? Things would be totally different in this country.

“Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed.” Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: Is there anything about our current time that dictates the need for a change in tactics?

CHENOWETH: Mobilizing without a long-term strategy or plan seems to be happening a lot right now, and that’s not what’s worked in the past. However, there’s nothing about the age we’re in that undermines the basic principles of success. I don’t think that the factors that influence success or failure are fundamentally different. Part of the reason I say that is because they’re basically the same things we observed when Gandhi was organizing in India as we do today. There are just some characteristics of our age that complicate things a bit.

WCFIA: You make the surprising claim that even when they fail, civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms than violent campaigns do. How does that work?

CHENOWETH: The finding is that civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms and changes that bring about democratization compared with violent campaigns. Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. This is because even though they “failed” in the short term, the nonviolent campaigns tended to empower moderates or reformers within the ruling elites who gradually began to initiate changes and liberalize the polity.

One of the best examples of this is the Kefaya movement in the early 2000s in Egypt. Although it failed in the short term, the experiences of different activists during that movement surely informed the ability to effectively organize during the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. Another example is the 2007 Saffron Revolution in Myanmar, which was brutally suppressed at the time but which ultimately led to voluntary democratic reforms by the government by 2012. Of course, this doesn’t mean that nonviolent campaigns always lead to democracies — or even that democracy is a cure-all for political strife. As we know, in Myanmar, relative democratization in the country’s institutions has been accompanied by extreme violence against the Rohingya community there. But it’s important to note that such cases are the exceptions rather than the norm. And democratization processes tend to be much bumpier when they occur after large-scale armed conflict instead of civil resistance campaigns, as was the case in Myanmar.

WCFIA: What are your current projects?

CHENOWETH: I’m still collecting data on nonviolent campaigns around the world. And I’m also collecting data on the nonviolent actions that are happening every day in the United States through a project called the Crowd Counting Consortium , with Jeremy Pressman of the University of Connecticut. It began in 2017, when Jeremy and I were collecting data during the Women’s March. Someone tweeted a link to our spreadsheet, and then we got tons of emails overnight from people writing in to say, “Oh, your number in Portland is too low; our protest hasn’t made the newspapers yet, but we had this many people.” There were the most incredible appeals. There was a nursing home in Encinitas, Calif., where 50 octogenarians organized an indoor women’s march with their granddaughters. Their local news had shot a video of them and they asked to be counted, and we put them in the sheet. People are very active and it’s not part of the broader public discourse about where we are as a country. I think it’s important to tell that story.

This originally appeared on the Weatherhead Center website . Part two of the series is now online.

The artwork, “Love and Revolution,” revolutionary graffiti at Saleh Selim Street on the island of Zamalek, Cairo, was photographed by Hossam el-Hamalawy on Oct. 23, 2011.

Share this article

You might like.

Peter Baker and Susan Glasser predict push to end Ukraine war on Russia’s terms, instability for NATO, possible global realignment

Deloria, Gone say action over decadeslong initiative to forcibly assimilate children overdue, necessary

Transportation secretary discusses aviation, roadway challenges during his time in office, administration’s frustrations, issues awaiting new president

Did Trump election signal start of new political era?

Analysts weigh issues, strategies, media decisions at work in contest, suggest class may become dominant factor

Is cheese bad for you?

Nutritionist explains why you’re probably eating way too much

U.S. fertility rates are tumbling, but some families still go big. Why?

It’s partly matter of faith. Economist examines choice to have large families in new book.

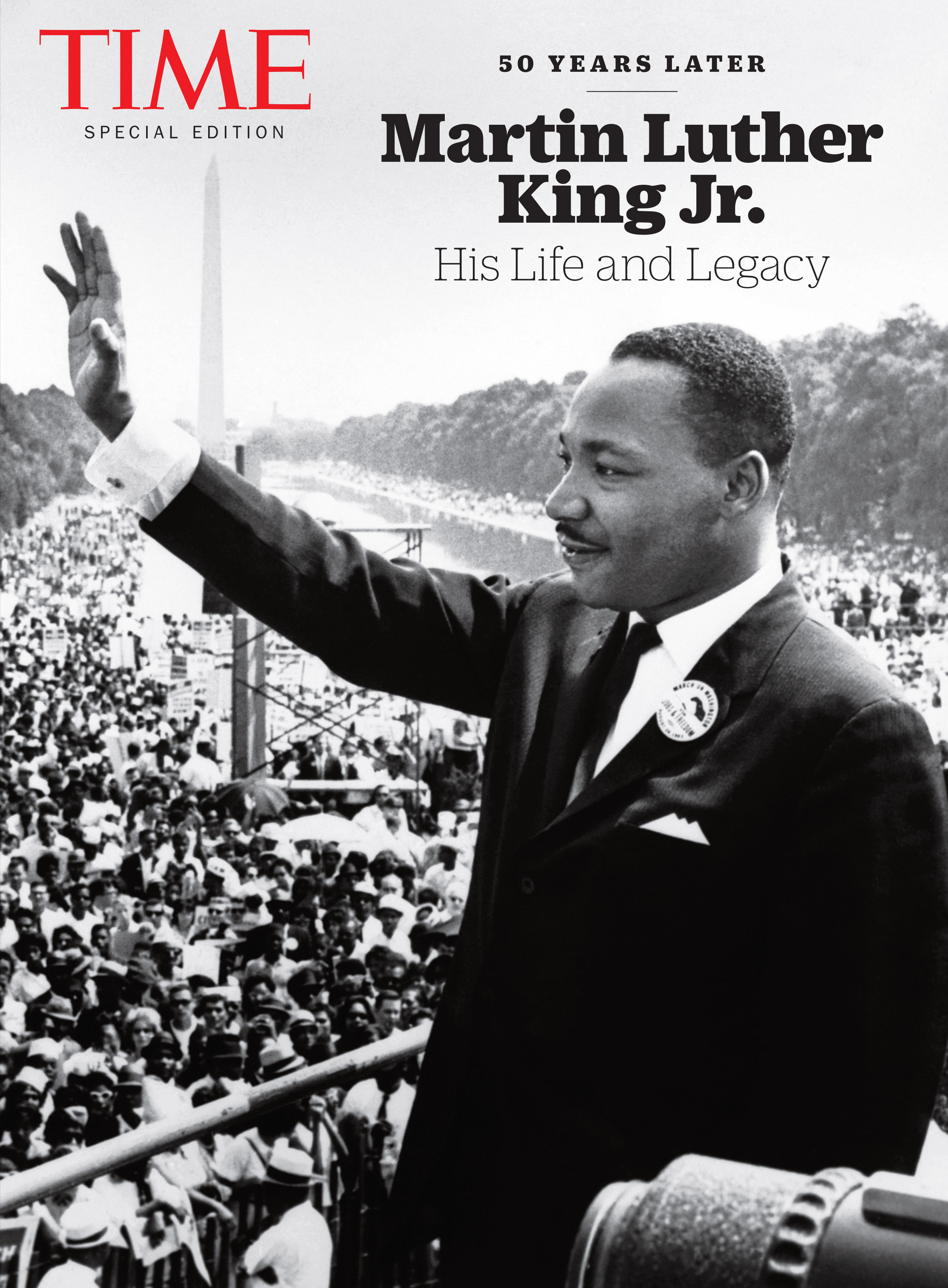

Why Martin Luther King Jr.’s Lessons About Peaceful Protests Are Still Relevant

The following feature is excerpted from TIME Martin Luther King, Jr.: His Life and Legacy , available at retailers and at the Time Shop

Revolutions tend to be measured in blood. From Lexington and the Bastille to the streets of Algiers, the toll on a repressed people seeking freedom is steep. But what does it take for a people to absorb degrading insults, physical attack and political repression in hopes that their oppressors will see the error in their ways? For Martin Luther King Jr. , it was a dream.

Over the course of a decade, King became synonymous with nonviolent direct action as he worked to overturn systemic segregation and racism across the southern United States. The civil rights movement formed the guidebook for a new era of protest. Whether it be responding to wars or protesting an unpopular administration at home, or the “color revolutions” across Europe and elsewhere overseas, the legacy of moral victory begetting actual change has been borne out time and again. The movement’s enduring influence is a far cry from its humble beginnings.

In March 1956, 90 defendants stood in wait in an aging Greek-revival courthouse in Montgomery, Ala. They faced the same charge: an obscure, decades-old anti-union law making it a misdemeanor to plot to interfere with a company’s business “without a just cause or legal excuse.” Their offense? Boycotting the city’s buses.

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

Young, old and from all walks of life—24 were clergymen—what united them was their dark skin and their act of quiet rebellion. First to face the judge was Martin Luther King Jr., 27, the youthful pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. Almost four months earlier, a black seamstress named Rosa Parks had sparked a boycott of the city’s privately owned bus services after she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white patron. Within days, the Montgomery Improvement Association was formed to organize private carpools to compete with the buses. King, who had moved to the city only two years earlier, was quickly elected its leader.

For 381 days, thousands of black residents trudged through chilling rain and oppressive heat, ignoring buses as they passed by. They endured death threats, violence and legal prosecution. King’s home was bombed. But instead of responding in kind, the members of the movement took to the pews, praying and rallying in churches in protest of the discrimination they suffered. In the courthouse, 31 testified to the harassment they endured on the city’s segregated buses, not so much a legal strategy as a moral one. Unsurprisingly in a city whose white–supremacist “White Citizens’ Council” membership skyrocketed after the boycott, King was found guilty and jailed for two weeks. As he said later, “It was the crime of joining my people in a non-violent protest against injustice.”

The boycott ended on Dec. 20, 1956, after the Supreme Court ruled that the racial segregation of buses was unconstitutional. But the enduring victory of Montgomery belonged not to the lawyers but to King and his fellow pastors—and the tens of thousands who followed them. Their protest shone a spotlight on the absurd lengths (enforcing an arcane and rarely invoked law) to which an entrenched power would go to protect a system designed to rob citizens of their worth solely because of their skin color.

“The strong man is the man who will not hit back, who can stand up for his rights and yet not hit back,” King told thousands of Montgomery Improvement Association supporters at the city’s Holt Street Baptist Church on Nov. 14, 1956. The black citizens of Montgomery would demonstrate their humanity while victims of a broken society. Nonviolence was the “testing point” of the burgeoning civil rights movement, King explained. “If we as Negroes succumb to the temptation of using violence in our struggle, unborn generations will be the recipients of a long and bitter night of—a long and desolate night of bitterness. And our only legacy to the future will be an endless reign of meaningless chaos.”

King had made the plight of the nation’s oppressed black citizens too plain to ignore, and it was a sharp blow to the “Christian conscience” of the white South. “They’ve become tortured souls,” Baptist minister William Finlator of Raleigh, N.C., told TIME then of his colleagues. “King has been working on the guilt conscience of the South. If he can bring us to contrition, that is our hope.”

Read more: John Lewis: Why Getting Into Trouble Is Necessary to Make Change

King became the symbol of nonviolent protest that had come to the fore in Montgomery. Inundated with speaking requests and interviews, and beset by threats of violence, King become a national celebrity both for what he accomplished and how. “Our use of passive resistance in Montgomery,” King told TIME, “is not based on resistance to get rights for ourselves, but to achieve friendship with the men who are denying us our rights, and change them through friendship and a bond of Christian understanding before God.”

On Jan. 10, 1957, weeks after black residents returned to unsegregated buses in the Alabama capital, King convened a gathering at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, the church where his father preached and that he would later lead. He invited influential civil rights activists, like strategist Bayard Rustin and organizer Ella Baker, and prominent black ministers from across the South to discuss how to expand the nonviolent resistance movement. After weeks of discussions, they formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a confederation of civil rights groups across the South, with King at the helm, that would go on to spread his philosophy.

Central to the SCLC’s mission was the notion that the Montgomery model could be replicated across the segregated South, to strike a blow against the entire Jim Crow system, which entrenched racial division in law and practice. But it wasn’t an easy sell. As the SCLC worked to recruit black churches and ministers, the organization faced real concerns of retaliation—both physical and economic—against those who signed on. Some doubted the method of nonviolent protest, believing the courts would eventually provide for integration. Others, especially younger groups, called for more-aggressive efforts.

But by 1960, nonviolent protests were sweeping across the South. In just one week in April, hundreds of black students were arrested as young people sat in and picketed segregated stores and diners from Nashville, Tenn., to Greensboro, N.C. Yet progress was painfully slow. In Savannah, Ga., the white mayor, Lee Mingledorff, demanded that the city council outlaw unlicensed picketing. “I don’t especially care if it’s constitutional or not,” he said. There were even more arrests, but the protests tired before achieving change.

The following year’s efforts were hardly more effective. A summer of Freedom Rides —in which black and white activists would jointly challenge segregation on buses—resulted in thousands of arrests and dozens of incidents of violence against demonstrators. But Jim Crow held. Groups consisting of younger and more impatient activists, like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality, shifted strategy, borrowing the lessons of Montgomery. In late 1961, the SNCC and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People targeted the heavily segregated city of Albany, Ga., with boycotts and sit-ins. The SCLC and King joined the effort, and in July 1962 King was jailed.

Days later, King was quietly bailed out and ejected from prison by Albany police chief Laurie Pritchett, who had studied the nonviolence protest method and released King to undermine it. In other cities, violence by police against peaceful demonstrators brought outcry and sympathy. But Pritchett met nonviolence with nonviolence. Within weeks, the protest fizzled out. For King, Albany was largely a failure, and his takeaway was for the movement to better pick its spots.

That place was Birmingham, Ala., “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States,” King would say. Racially motivated bombings against blacks had earned the city the nickname “Bombingham,” and many of its majority-black residents were denied all but the most menial jobs—if they could find work at all. Unlike in Albany, where the goal had been to desegregate the city, in Birmingham King focused on the downtown shopping district. And unlike in Albany, he had a foil of the first degree: Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor. Connor told TIME in 1963 that the city “ain’t gonna segregate no niggers and whites together in this town.”

The tactics changed too. While there were sit-ins and kneel-ins and demonstrations, the SCLC also encouraged an economic boycott of the city. Birmingham’s economic heart, its shopping district, was crippled when black residents refused to shop in segregated stores. Boycott organizers patrolled the streets to shame black residents into toeing the line. The protests were designed to force a crisis point, and Connor only aided the effort. When business took down “Whites Only” signs, the avowed racist threatened to pull their licenses. On Good Friday, King was jailed for his 13th time for more than a week. Using the margins of scrap paper smuggled into his cell, King drafted his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” among the clearest representations of his philosophy.

“Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue,” King wrote. “It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”

Children provided the movement with some of its most powerful images, and the SCLC and King encouraged students to skip school to join sit-ins and marches. On May 2, the Children’s Crusade saw the arrest of hundreds of students in Birmingham, some under the age of 10, who sang and prayed as they awaited arrest. The New York Times compared the scene to a “school picnic” as they were transported to the city’s jail by every available city vehicle. Within hours, the prison was at capacity, filled with hundreds of school-age children.

Unbowed, Connor changed tactics, and the next day he deployed fire hoses and police dogs against a peaceful protest march in the downtown business district. The images, some of the most grotesque and iconic of the era, dominated nightly news broadcasts and national newspapers and magazines nationwide. In Washington, lawmakers took up the issue of civil rights legislation with renewed vigor. President John F. Kennedy said the day’s events were “so much more eloquently reported by the news camera than by any number of explanatory words,” calling the scene “shameful.”

In a paralyzed Birmingham, more than 2,000 people had been arrested, with officials turning the state fairgrounds into a makeshift holding area. The fire department bucked Connor’s orders to redeploy its hoses against demonstrators. The city’s chamber of commerce pleaded for talks, even as political leaders were steadfast in their commitment to Jim Crow. By May 8, the white business leaders had acceded to most of King’s demands, promising to desegregate diner counters, rest-rooms and water fountains within 90 days.

It was far from total victory, but King had something more important: the attention of an outraged and rapt nation. The legacy of the water cannons and dogs, of callused feet and imprisoned children, would be incarnated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act and the Twenty-Fourth Amendment, which banned poll taxes. Montgomery and Birmingham also formed the script for peaceably countering injustice in a nation founded on protest. From antiwar protests during Vietnam to Occupy Wall Street and beyond, King’s commitment to nonviolent protest lives on.

Imprisoned in Birmingham Jail, King wrote in praise of those nonviolently demonstrating outside “for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]

IMAGES