Fostering Critical Thinking in Group Work for Effective Learning

- April 28, 2024

- Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinking plays a pivotal role in enhancing the efficacy of group work. In educational and professional settings alike, the ability to analyze information critically fosters robust discussions, leading to more innovative solutions and effective decision-making.

The integration of critical thinking in group work not only enriches collaborative learning experiences but also equips participants with essential skills to tackle complex problems. Understanding critical thinking within this context is imperative for achieving productive teamwork.

Table of Contents

Understanding Critical Thinking in Group Work

Critical thinking in group work refers to the ability of individuals to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information collaboratively. It is an essential skill that enhances decision-making and problem-solving outcomes by incorporating diverse viewpoints and insights from all group members.

This form of critical thinking fosters a shared understanding among participants, allowing for a more comprehensive approach to challenges. By leveraging the strengths of each member, groups can navigate complex issues more effectively. Engaging in critical thinking processes helps in recognizing biases and assumptions, leading to well-rounded conclusions.

Furthermore, this collaborative approach promotes open dialogue and encourages constructive feedback, which are vital for a successful teamwork environment. Ultimately, critical thinking in group work enhances not only the group’s output but also the individual members’ abilities to reason and contextualize their ideas within a broader framework. Such engagement is pivotal in fostering a culture of continuous learning and improvement in various educational and professional settings.

The Role of Critical Thinking in Collaborative Learning

Critical thinking in collaborative learning involves the capacity to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information shared among group members. This process is vital for effective communication and comprehension, enabling individuals to engage in meaningful discussions and construct well-supported arguments.

In collaborative settings, critical thinking fosters an environment where diverse perspectives can be examined. Participants are encouraged to question assumptions, challenge viewpoints, and explore alternative solutions to problems, which stimulates deeper understanding and innovation.

Moreover, the effective application of critical thinking skills in group work enhances decision-making processes. By consistently evaluating the potential outcomes of various options, groups are better equipped to reach consensus and implement solutions that reflect collective intelligence.

Ultimately, incorporating critical thinking in collaborative learning not only improves group dynamics but also contributes to enduring learning outcomes. This approach prepares participants to face complex challenges and equips them with the skills necessary for future endeavors.

Essential Critical Thinking Skills for Group Work

Critical thinking in group work encompasses several essential skills, allowing team members to collaboratively solve problems and make informed decisions. Analysis and evaluation stand out as foundational elements. Team members must dissect information and assess its relevance while recognizing different viewpoints. This fosters a deeper understanding of the issues at hand, promoting more effective discussions.

Problem-solving techniques are integral to successful group dynamics. Teams benefit from structured approaches that guide them through complex challenges. Techniques such as brainstorming and root cause analysis empower group members to generate innovative solutions, ensuring that various perspectives are considered in developing effective strategies.

Decision-making processes are vital in directing group efforts. Members must weigh options carefully, balancing potential outcomes against group goals. By encouraging open communication and consensus-building, groups enhance their decision-making capabilities, resulting in actions backed by collective insights. Through these critical thinking skills, group work becomes a dynamic environment for collaboration and creativity.

Analysis and Evaluation

Analysis and evaluation are fundamental components of critical thinking in group work. Analysis involves the dissection of information, ideas, or arguments into their constituent parts to understand their structure and meaning. This skill allows group members to identify underlying assumptions, recognize biases, and assess the credibility of sources.

Evaluation, on the other hand, deals with assessing the value or relevance of the information and arguments presented. Group members must weigh evidence, consider different perspectives, and determine the strengths and weaknesses of various viewpoints. This combination of analysis and evaluation promotes informed decision-making and fosters a collaborative atmosphere.

In practice, when group members engage in thorough analysis, they can break down complex problems into manageable components. Subsequently, evaluation helps them to prioritize those components based on relevance and potential impact. The synergy of these critical thinking skills ultimately enhances the group’s ability to produce cohesive and effective outcomes.

Implementing structured methodologies for analysis and evaluation can significantly elevate the quality of discussions in group contexts. Tools such as SWOT analysis or the Six Thinking Hats technique can guide group members in systematically evaluating the information at hand.

Problem-Solving Techniques

Problem-solving techniques involve systematic methods employed by groups to address challenges and implement effective solutions. These techniques enhance critical thinking in group work by promoting collaborative engagement and driving comprehensive analysis of the situation at hand.

One widely-used method is the “Five Whys” technique, where group members repeatedly ask “why” to identify the root cause of a problem. This technique encourages deeper investigation and fosters critical thinking by compelling participants to articulate their reasoning and assumptions.

Another effective problem-solving technique is brainstorming, which involves generating a wide range of ideas without immediate judgment. This method empowers group members to explore diverse perspectives and encourages creative solutions, thereby reinforcing critical thinking in group settings.

Moreover, the use of mind mapping aids in visualizing problems and potential solutions. By mapping out relationships and ideas, groups can better understand complex issues and collaboratively identify strategic approaches, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of critical thinking in group work.

Decision-Making Processes

Decision-making processes in group work entail several critical stages that ensure effective collaboration and sound judgment. Central to these processes is the identification of a clear objective, enabling the group to align its efforts toward a common goal. This shared purpose fosters unity and directs the focus of discussions and analyses.

Once a goal is established, group members must gather relevant information and explore various perspectives. Open dialogue is vital, as it promotes the sharing of insights and encourages diverse viewpoints. Dialogue helps unravel complexities and stimulates innovative thinking, which enhances critical thinking in group work.

Subsequently, groups must evaluate the options available. Critical evaluation involves assessing potential consequences and benefits, weighing pros and cons for each alternative. This methodical appraisal allows groups to make informed choices, ultimately leading to strategic decision-making that reflects the collective intellect of the group.

Finally, implementing the chosen course of action requires coordination and adaptability. Regularly reviewing outcomes and gathering feedback can refine future decision-making processes. By fostering an environment conducive to continuous improvement, groups can enhance their critical thinking skills and achieve better results in collaborative learning settings.

Strategies to Foster Critical Thinking in Group Settings

Effective strategies are essential for fostering critical thinking in group settings. Structured discussion techniques encourage participants to engage thoughtfully, ensuring every voice is heard and considered. Techniques such as brainstorming followed by critical analysis promote a culture of inquiry and deeper understanding among group members.

Collaborative problem-solving is another strategy that enhances critical thinking. By approaching complex issues collectively, individuals can leverage diverse viewpoints. This cooperative effort not only strengthens group cohesion but also stimulates varied solutions, prompting a more comprehensive exploration of the problem at hand.

Implementing reflection and feedback mechanisms is vital as well. Regular debriefing sessions allow groups to assess their performance, identify strengths and weaknesses, and make adjustments accordingly. This ongoing evaluation cultivates an environment where critical thinking is not only encouraged but becomes an integral aspect of the group’s process.

Incorporating these strategies can significantly enhance the effectiveness of critical thinking in group work, leading to more informed and effective group outcomes.

Structured Discussion Techniques

Structured discussion techniques provide a framework for fostering critical thinking in group work. These methods not only facilitate organized conversations but also encourage participants to engage deeply with the subject matter. Effective communication is paramount in ensuring that all voices are heard and respected.

One effective approach is the “think-pair-share” technique, where individuals contemplate a question or problem independently, then discuss their thoughts paired with a partner before sharing insights with the larger group. This promotes critical engagement and reflects diverse perspectives.

Another technique is the use of a “fishbowl” format, where a small group discusses a topic while others observe. This arrangement allows participants to analyze the discussion dynamics and think critically about the content, fostering a supportive environment for critical thinking.

Incorporating structured discussion techniques like these ensures that critical thinking in group work is nurtured, allowing diverse viewpoints to contribute toward collaborative solutions. This ultimately enhances the overall learning experience in online learning settings.

Collaborative Problem Solving

Collaborative problem solving involves a group of individuals working together to address a specific issue or challenge. In this process, participants leverage diverse perspectives and expertise, enhancing their collective critical thinking in group work.

To facilitate effective collaborative problem solving, groups can utilize various strategies:

- Clearly defining the problem to ensure all team members have a shared understanding.

- Encouraging open communication to share insights and solutions.

- Facilitating brainstorming sessions to generate a range of solutions.

Using structured approaches helps maintain focus and encourages participation. Techniques like the nominal group technique or the Delphi method can help identify the best solutions while fostering a sense of accountability among group members.

Implementing these practices not only improves problem-solving outcomes but also enhances individual critical thinking skills. As team members navigate challenges collectively, they develop deeper analytical abilities that contribute to broader learning and cooperative efforts in any educational setting.

Reflection and Feedback Mechanisms

Reflection and feedback mechanisms are essential components in fostering critical thinking in group work. These processes encourage participants to evaluate their contributions and the effectiveness of group dynamics, thereby enhancing collaborative learning. By promoting open discussions, team members can articulate their thoughts and address any misunderstandings that may arise.

Implementing structured reflection activities, such as after-action reviews or debriefing sessions, allows groups to critically assess their performance. Feedback mechanisms, including peer evaluations and facilitator guidance, help identify areas for improvement. This iterative process solidifies the understanding of critical thinking in group work.

Regular reflection not only cultivates self-awareness but also nurtures a collective responsibility among group members. When participants actively engage in giving and receiving constructive feedback, the group can adapt and refine its strategies. This adaptability is paramount for developing and honing critical thinking skills in collaborative settings.

Moreover, integrating reflection and feedback into routine practices empowers learners. It transforms individual insights into shared knowledge, fostering a culture where critical thinking thrives. Ultimately, these mechanisms serve as catalysts for continuous improvement and excellence in group work.

Overcoming Barriers to Critical Thinking in Groups

Critical thinking in group work often faces several barriers that can impede effective collaboration. Such barriers may include conformity pressures, lack of communication, dominance of certain group members, and emotional conflicts. Addressing these issues is vital to enhance critical thinking within group settings.

Conformity pressures can discourage individuals from voicing differing opinions, leading to groupthink. To overcome this, fostering an inclusive environment where all members feel safe sharing ideas is essential. Encouraging diversity of thought not only enhances critical thinking but also enriches the overall learning experience.

Additionally, effective communication needs to be prioritized. A lack of open dialogue can hinder the exchange of ideas. Implementing structured discussion techniques can facilitate clearer communication, allowing members to articulate their viewpoints without interruption or judgment.

Emotional conflicts among group members can detract from the analytical focus required for critical thinking. Encouraging reflection and feedback mechanisms can help address these conflicts. By creating a space for constructive criticism and support, groups can navigate emotional barriers and maintain a focus on collaborative problem-solving.

Assessing Critical Thinking in Group Projects

Assessing critical thinking in group projects involves evaluating how effectively group members engage in analytical processes, contribute to discussions, and collaborate towards solutions. This assessment goes beyond mere product evaluation, focusing on the dynamics and thinking processes underpinning group interactions.

Evaluation criteria for group work should include factors such as the quality of arguments presented, the depth of analysis undertaken, and the extent to which members challenge assumptions. Each group member’s ability to articulate ideas and respond to differing viewpoints is equally important in understanding the group’s critical thinking capabilities.

Tools for measuring effectiveness can encompass peer evaluations, self-reflections, and structured rubrics designed to assess critical thinking skills. These tools facilitate a comprehensive understanding of individual contributions and the collective reasoning process within the group.

Continuous improvement practices, such as regular feedback sessions and discussions about group performance, foster an environment conducive to reflection and growth. This approach encourages the enhancement of critical thinking in group projects, ultimately leading to improved collaborative learning outcomes.

Evaluation Criteria for Group Work

Evaluation criteria for group work encompasses various dimensions that measure the effectiveness of critical thinking in collaborative settings. These criteria should encompass both individual contributions and the overall group performance, ensuring that each member’s input is fairly assessed.

Key evaluation factors may include the quality of ideas presented, the ability to engage in constructive dialogue, and the process of arriving at group decisions. Specific metrics such as creativity, coherence, and relevancy of contributions help in understanding how well critical thinking is applied throughout the project.

Another essential criterion lies in the effectiveness of conflict resolution strategies and the adaptability of group members to differing viewpoints. The assessment framework should encourage a reflective approach, prompting groups to evaluate their dynamics and the rationale behind their decisions.

Furthermore, peer assessments can play a vital role in this evaluation process. By allowing group members to provide feedback on each other’s performances, individuals may gain insights into their critical thinking skills, promoting a culture of continuous improvement within the group work context.

Tools for Measuring Effectiveness

Effective assessment tools are essential for evaluating critical thinking in group work. They help gauge not only the individuals’ contributions but also the group’s overall performance. Various methodologies can be employed to measure effectiveness in collaborative settings.

Surveys and questionnaires can provide invaluable insights into participants’ perceptions of group dynamics and critical thinking processes. These tools gather feedback on how well the group functioned, enabling reflection on both successes and areas for improvement.

Rubrics offer a structured framework for evaluating group projects, detailing specific criteria related to critical thinking. They can include aspects such as analysis, argumentation, and collaboration, allowing educators to provide targeted feedback.

Peer evaluations further enrich the assessment process, as they encourage accountability and self-reflection among group members. This method fosters introspection about one’s contributions while promoting a culture of constructive critique, ultimately enhancing critical thinking in group work.

Continuous Improvement Practices

Continuous improvement practices in the context of critical thinking in group work involve a systematic approach to enhance collaborative efforts. This framework emphasizes the iterative assessment of group processes and outcomes, fostering an environment where critical thinking skills can flourish.

Mechanisms such as regular feedback sessions and reflective discussions are pivotal in identifying strengths and weaknesses within group dynamics. Utilizing tools like surveys can encourage participants to express their thoughts on the group’s critical thinking effectiveness, facilitating necessary adjustments.

Incorporating continuous improvement models, such as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA), allows groups to implement changes systematically. This structured approach not only promotes accountability but also ensures that critical thinking in group work is continuously refined and optimized.

Encouraging team members to document their learning experiences and insights can further strengthen critical thinking skills. Sharing these reflections not only creates a repository of knowledge but also inspires ongoing dialogue, ultimately enhancing the quality of group work.

Case Studies of Successful Critical Thinking in Group Work

Examining case studies exemplifies how critical thinking can enhance group work. One notable example is a university project where students collaborated to develop a community service plan. Through structured critical discussions, they evaluated various options, leading to innovative solutions tailored to local needs.

Another case involved a corporate team tasked with improving product development. By employing problem-solving techniques, they analyzed customer feedback critically, ultimately redesigning a product that significantly boosted sales. This approach showcased the importance of collective analysis in achieving tangible results.

In an educational setting, a group of teachers implemented collaborative problem-solving strategies to address student engagement issues. By sharing experiences and reflecting on their practices, they identified effective teaching methods, enhancing overall student performance. These cases underscore the pivotal role of critical thinking in group work dynamics.

The Impact of Technology on Critical Thinking in Group Work

Technology significantly influences critical thinking in group work by enhancing communication, providing access to diverse resources, and facilitating collaborative tools. This impact cultivates a more engaged and analytical team dynamic, fostering an environment conducive to effective problem-solving and decision-making.

One major benefit of technology is its capacity to streamline communication among group members. Platforms such as video conferencing, instant messaging, and collaborative document sharing systems enable real-time discussion and brainstorming. This immediacy encourages the exchange of ideas, enhancing critical analysis and evaluation.

Additionally, technology offers a plethora of resources that broaden the scope of information available to group members. Access to databases, online courses, and research tools allows teams to explore topics deeply, which is vital for thorough analysis and informed decision-making.

Lastly, various applications designed for group work promote structured approaches to collaboration. Tools such as project management software can help groups outline tasks, track progress, and reflect on performance, supporting critical thinking and continuous improvement in group projects.

Training Programs for Improving Group Critical Thinking Skills

Training programs aimed at improving group critical thinking skills can significantly enhance collaboration and problem-solving dynamics in various environments. Such programs typically involve structured frameworks that focus on developing analytical capabilities and promoting constructive dialogue among team members.

Key components of these training programs include:

- Workshops that provide participants with scenarios for collaborative problem-solving.

- Activities centered on role-playing to simulate real-world group decision-making situations.

- Exercises designed to enhance communication skills, ensuring all voices are heard during discussions.

By integrating these elements, participants are encouraged to navigate complex issues collectively, fostering a culture of critical thinking in group work. Continuous practice through these training programs reinforces habits of effective analysis, evaluation, and decision-making within groups, preparing individuals for future collaborative challenges. This not only benefits current group projects but also equips members with vital skills for ongoing professional development.

The Future of Critical Thinking in Group Work

The evolving landscape of education emphasizes the importance of critical thinking in group work. As online learning becomes increasingly prevalent, there is a growing recognition of the need for collaborative skills that foster critical thinking. In this context, effective group work relies heavily on the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize diverse perspectives, ultimately enhancing the learning experience.

Technology plays a pivotal role in shaping the future of critical thinking in group work. Virtual collaborative platforms, artificial intelligence, and multimedia tools facilitate richer discussions and the sharing of ideas. These advancements encourage students to engage in meaningful dialogues, enhancing their analytical and reflective capabilities.

Additionally, the continued emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches is likely to enrich group dynamics. By merging insights from various fields, learners can approach problems from multiple angles. This cross-pollination of ideas enhances the collective critical thinking skills essential for effective group work.

As educational institutions adapt their curricula, training programs focused on critical thinking in group settings will become central. These programs will equip students with the skills necessary to navigate complex challenges collaboratively, ensuring they are prepared for future demands in the workforce.

Critical thinking in group work is imperative for fostering an effective collaborative learning environment. By cultivating essential skills such as analysis, problem-solving, and decision-making, teams can not only enhance their output but also develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

As online learning continues to evolve, the integration of technology further supports the advancement of critical thinking in group settings. Embracing effective strategies and overcoming barriers will ensure that learners are equipped to thrive in their academic and professional endeavors.

Center for Teaching

Group work: using cooperative learning groups effectively.

Many instructors from disciplines across the university use group work to enhance their students’ learning. Whether the goal is to increase student understanding of content, to build particular transferable skills, or some combination of the two, instructors often turn to small group work to capitalize on the benefits of peer-to-peer instruction. This type of group work is formally termed cooperative learning, and is defined as the instructional use of small groups to promote students working together to maximize their own and each other’s learning (Johnson, et al., 2008).

Cooperative learning is characterized by positive interdependence, where students perceive that better performance by individuals produces better performance by the entire group (Johnson, et al., 2014). It can be formal or informal, but often involves specific instructor intervention to maximize student interaction and learning. It is infinitely adaptable, working in small and large classes and across disciplines, and can be one of the most effective teaching approaches available to college instructors.

What can it look like?

What’s the theoretical underpinning, is there evidence that it works.

- What are approaches that can help make it effective?

Informal cooperative learning groups In informal cooperative learning, small, temporary, ad-hoc groups of two to four students work together for brief periods in a class, typically up to one class period, to answer questions or respond to prompts posed by the instructor.

Additional examples of ways to structure informal group work

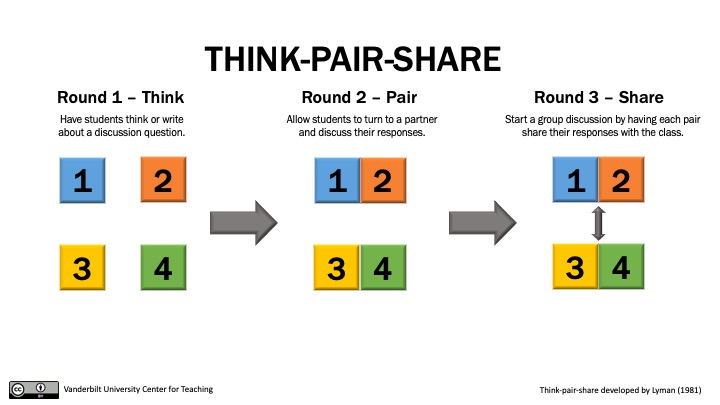

Think-pair-share

The instructor asks a discussion question. Students are instructed to think or write about an answer to the question before turning to a peer to discuss their responses. Groups then share their responses with the class.

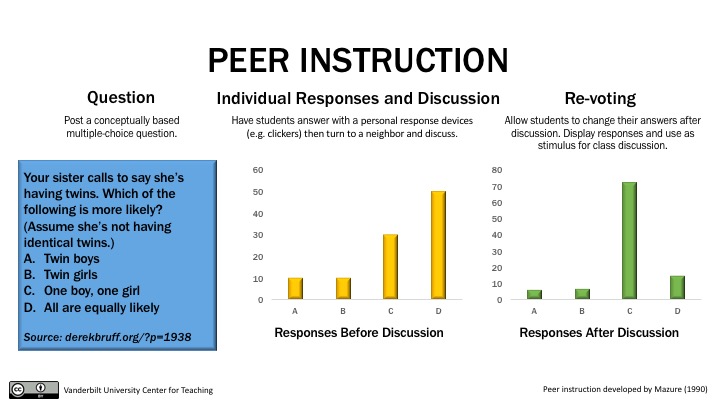

Peer Instruction

This modification of the think-pair-share involves personal responses devices (e.g. clickers). The question posted is typically a conceptually based multiple-choice question. Students think about their answer and vote on a response before turning to a neighbor to discuss. Students can change their answers after discussion, and “sharing” is accomplished by the instructor revealing the graph of student response and using this as a stimulus for large class discussion. This approach is particularly well-adapted for large classes.

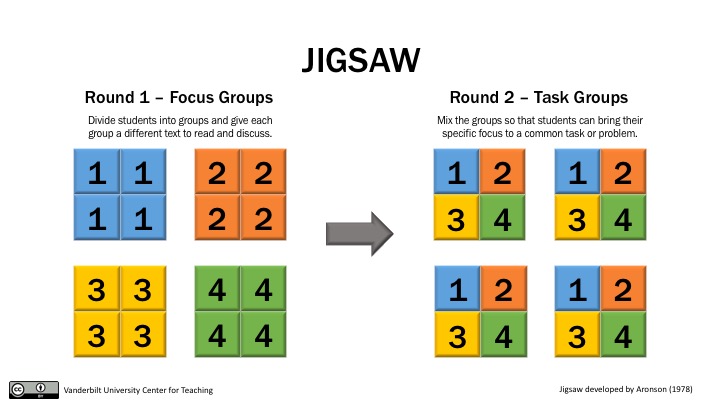

In this approach, groups of students work in a team of four to become experts on one segment of new material, while other “expert teams” in the class work on other segments of new material. The class then rearranges, forming new groups that have one member from each expert team. The members of the new team then take turns teaching each other the material on which they are experts.

Formal cooperative learning groups

In formal cooperative learning students work together for one or more class periods to complete a joint task or assignment (Johnson et al., 2014). There are several features that can help these groups work well:

- The instructor defines the learning objectives for the activity and assigns students to groups.

- The groups are typically heterogeneous, with particular attention to the skills that are needed for success in the task.

- Within the groups, students may be assigned specific roles, with the instructor communicating the criteria for success and the types of social skills that will be needed.

- Importantly, the instructor continues to play an active role during the groups’ work, monitoring the work and evaluating group and individual performance.

- Instructors also encourage groups to reflect on their interactions to identify potential improvements for future group work.

This video shows an example of formal cooperative learning groups in David Matthes’ class at the University of Minnesota:

There are many more specific types of group work that fall under the general descriptions given here, including team-based learning , problem-based learning , and process-oriented guided inquiry learning .

The use of cooperative learning groups in instruction is based on the principle of constructivism, with particular attention to the contribution that social interaction can make. In essence, constructivism rests on the idea that individuals learn through building their own knowledge, connecting new ideas and experiences to existing knowledge and experiences to form new or enhanced understanding (Bransford, et al., 1999). The consideration of the role that groups can play in this process is based in social interdependence theory, which grew out of Kurt Koffka’s and Kurt Lewin’s identification of groups as dynamic entities that could exhibit varied interdependence among members, with group members motivated to achieve common goals. Morton Deutsch conceptualized varied types of interdependence, with positive correlation among group members’ goal achievements promoting cooperation.

Lev Vygotsky extended this work by examining the relationship between cognitive processes and social activities, developing the sociocultural theory of development. The sociocultural theory of development suggests that learning takes place when students solve problems beyond their current developmental level with the support of their instructor or their peers. Thus both the idea of a zone of proximal development, supported by positive group interdependence, is the basis of cooperative learning (Davidson and Major, 2014; Johnson, et al., 2014).

Cooperative learning follows this idea as groups work together to learn or solve a problem, with each individual responsible for understanding all aspects. The small groups are essential to this process because students are able to both be heard and to hear their peers, while in a traditional classroom setting students may spend more time listening to what the instructor says.

Cooperative learning uses both goal interdependence and resource interdependence to ensure interaction and communication among group members. Changing the role of the instructor from lecturing to facilitating the groups helps foster this social environment for students to learn through interaction.

David Johnson, Roger Johnson, and Karl Smith performed a meta-analysis of 168 studies comparing cooperative learning to competitive learning and individualistic learning in college students (Johnson et al., 2006). They found that cooperative learning produced greater academic achievement than both competitive learning and individualistic learning across the studies, exhibiting a mean weighted effect size of 0.54 when comparing cooperation and competition and 0.51 when comparing cooperation and individualistic learning. In essence, these results indicate that cooperative learning increases student academic performance by approximately one-half of a standard deviation when compared to non-cooperative learning models, an effect that is considered moderate. Importantly, the academic achievement measures were defined in each study, and ranged from lower-level cognitive tasks (e.g., knowledge acquisition and retention) to higher level cognitive activity (e.g., creative problem solving), and from verbal tasks to mathematical tasks to procedural tasks. The meta-analysis also showed substantial effects on other metrics, including self-esteem and positive attitudes about learning. George Kuh and colleagues also conclude that cooperative group learning promotes student engagement and academic performance (Kuh et al., 2007).

Springer, Stanne, and Donovan (1999) confirmed these results in their meta-analysis of 39 studies in university STEM classrooms. They found that students who participated in various types of small-group learning, ranging from extended formal interactions to brief informal interactions, had greater academic achievement, exhibited more favorable attitudes towards learning, and had increased persistence through STEM courses than students who did not participate in STEM small-group learning.

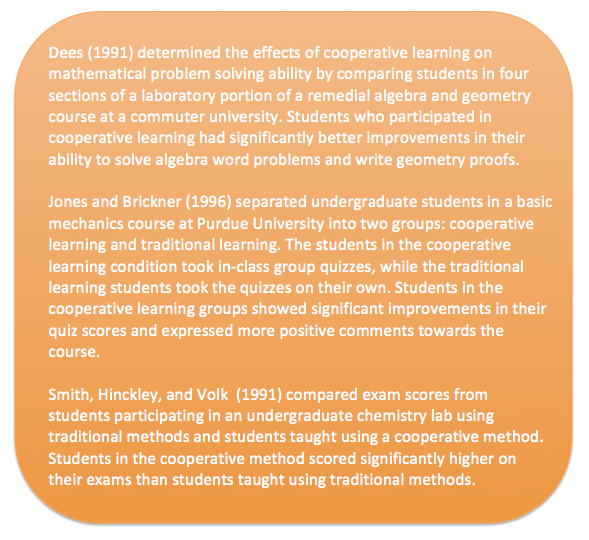

The box below summarizes three individual studies examining the effects of cooperative learning groups.

What are approaches that can help make group work effective?

Preparation

Articulate your goals for the group work, including both the academic objectives you want the students to achieve and the social skills you want them to develop.

Determine the group conformation that will help meet your goals.

- In informal group learning, groups often form ad hoc from near neighbors in a class.

- In formal group learning, it is helpful for the instructor to form groups that are heterogeneous with regard to particular skills or abilities relevant to group tasks. For example, groups may be heterogeneous with regard to academic skill in the discipline or with regard to other skills related to the group task (e.g., design capabilities, programming skills, writing skills, organizational skills) (Johnson et al, 2006).

- Groups from 2-6 are generally recommended, with groups that consist of three members exhibiting the best performance in some problem-solving tasks (Johnson et al., 2006; Heller and Hollabaugh, 1992).

- To avoid common problems in group work, such as dominance by a single student or conflict avoidance, it can be useful to assign roles to group members (e.g., manager, skeptic, educator, conciliator) and to rotate them on a regular basis (Heller and Hollabaugh, 1992). Assigning these roles is not necessary in well-functioning groups, but can be useful for students who are unfamiliar with or unskilled at group work.

Choose an assessment method that will promote positive group interdependence as well as individual accountability.

- In team-based learning, two approaches promote positive interdependence and individual accountability. First, students take an individual readiness assessment test, and then immediately take the same test again as a group. Their grade is a composite of the two scores. Second, students complete a group project together, and receive a group score on the project. They also, however, distribute points among their group partners, allowing student assessment of members’ contributions to contribute to the final score.

- Heller and Hollabaugh (1992) describe an approach in which they incorporated group problem-solving into a class. Students regularly solved problems in small groups, turning in a single solution. In addition, tests were structured such that 25% of the points derived from a group problem, where only those individuals who attended the group problem-solving sessions could participate in the group test problem. This approach can help prevent the “free rider” problem that can plague group work.

- The University of New South Wales describes a variety of ways to assess group work , ranging from shared group grades, to grades that are averages of individual grades, to strictly individual grades, to a combination of these. They also suggest ways to assess not only the product of the group work but also the process. Again, having a portion of a grade that derives from individual contribution helps combat the free rider problem.

Helping groups get started

Explain the group’s task, including your goals for their academic achievement and social interaction.

Explain how the task involves both positive interdependence and individual accountability, and how you will be assessing each.

Assign group roles or give groups prompts to help them articulate effective ways for interaction. The University of New South Wales provides a valuable set of tools to help groups establish good practices when first meeting. The site also provides some exercises for building group dynamics; these may be particularly valuable for groups that will be working on larger projects.

Monitoring group work

Regularly observe group interactions and progress , either by circulating during group work, collecting in-process documents, or both. When you observe problems, intervene to help students move forward on the task and work together effectively. The University of New South Wales provides handouts that instructors can use to promote effective group interactions, such as a handout to help students listen reflectively or give constructive feedback , or to help groups identify particular problems that they may be encountering.

Assessing and reflecting

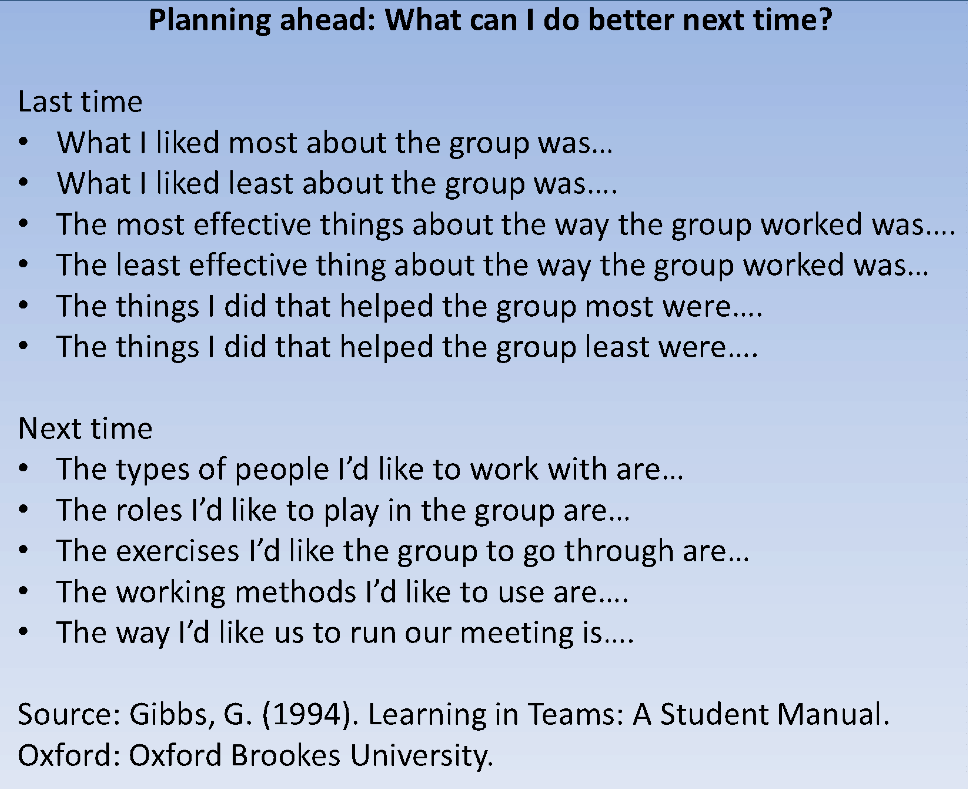

In addition to providing feedback on group and individual performance (link to preparation section above), it is also useful to provide a structure for groups to reflect on what worked well in their group and what could be improved. Graham Gibbs (1994) suggests using the checklists shown below.

The University of New South Wales provides other reflective activities that may help students identify effective group practices and avoid ineffective practices in future cooperative learning experiences.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., and Cocking, R.R. (Eds.) (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school . Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Bruffee, K. A. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cabrera, A. F., Crissman, J. L., Bernal, E. M., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. T., & Pascarella, E. T. (2002). Collaborative learning: Its impact on college students’ development and diversity. Journal of College Student Development, 43 (1), 20-34.

Davidson, N., & Major, C. H. (2014). Boundary crossing: Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and problem-based learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3&4), 7-55.

Dees, R. L. (1991). The role of cooperative leaning in increasing problem-solving ability in a college remedial course. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 22 (5), 409-21.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative Learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7 (1).

Heller, P., and Hollabaugh, M. (1992) Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups. American Journal of Physics 60, 637-644.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Smith, K.A. (2006). Active learning: Cooperation in the university classroom (3 rd edition). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Holubec, E.J. (2008). Cooperation in the classroom (8 th edition). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Smith, K.A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journl on Excellence in College Teaching 25, 85-118.

Jones, D. J., & Brickner, D. (1996). Implementation of cooperative learning in a large-enrollment basic mechanics course. American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference Proceedings.

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J., Bridges, B., and Hayek, J.C. (2007). Piecing together the student success puzzle: Research, propositions, and recommendations (ASHE Higher Education Report, No. 32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Love, A. G., Dietrich, A., Fitzgerald, J., & Gordon, D. (2014). Integrating collaborative learning inside and outside the classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3&4), 177-196.

Smith, M. E., Hinckley, C. C., & Volk, G. L. (1991). Cooperative learning in the undergraduate laboratory. Journal of Chemical Education 68 (5), 413-415.

Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 96 (1), 21-51.

Uribe, D., Klein, J. D., & Sullivan, H. (2003). The effect of computer-mediated collaborative learning on solving ill-defined problems. Educational Technology Research and Development, 51 (1), 5-19.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

IMAGES

VIDEO