- Prof Mark Reed and Radoje Lausevic (Deputy

- Jan 9, 2016

- 10 min read

Who will benefit from your research and who will block it? How to identify stakeholders

Updated: Feb 21, 2020

Updated 2019 guide now available here .

For the original 2016 guide, continue reading...

________________________________________________

Researchers are increasingly expected by funders to identify and incorporate ‘beneficiaries’ into their work from the outset. Working out who might benefit from your work isn’t always easy though. Even if you do know who will benefit from your research, an equally important but often unasked question is: “who might be disadvantaged or lose out as a result of my research?” Even if you can answer both of these questions, there is another crucial question that every researcher should ask themselves: “who has the power to enable me to do my research and achieve impacts, and who has the power to block my work?”

It is just as important to identify individuals, organisations and groups who my be disadvantaged by the outcomes of your work, or who may block your research, as it is to know who your beneficiaries are, and who can help you. Knowing about potentially problematic stakeholders at the outset can give you the necessary time to adapt your research so that it no longer disadvantages those groups, or work out ways of ameliorating negative impacts before you run into opposition or achieve bitter-sweet impacts for one group at the expense of another.

What is a stakeholder?

A stakeholder is any person, organization or group that is affected by or who can affect a decision, action or issue. Rather than just identifying ‘beneficiaries’, a stakeholder analysis seeks to identify people, organisations or groups who may be either positively or negatively affected by your research. In addition to identifying those affected by your research, stakeholder analysis seeks to also identify those who might affect your ability to complete your research and generate impacts, either positively or negatively. These stakeholders might not directly benefit from or be negatively affected by your work, but they may have the power to enable or block your work from making a difference.

Why analyse your stakeholders?

It may seem self-evident that all the relevant stakeholders should be identified prior to any attempt to engage. However, it is surprising how often this step is omitted in research projects that need to work with stakeholders. In many cases this omission can significantly compromise the success of the research. For example, the project may miss crucial information that could have been provided, had they engaged with the right people.

In cases where very few stakeholders are identified or engaged with, this can lead to a lack of ownership of project goals, which can sometimes turn into opposition from certain stakeholders. In cases where a single important stakeholder has been omitted from the process, that organization or group may challenge the legitimacy of the work, and undermine the credibility of the wider project. Stakeholder analysis helps solve these problems by:

Identifying who has a stake in your work;

Categorising and prioritizing stakeholders you need to invest most time with; and

Identifying (and preparing you for) relationships between stakeholders (whether conflicts or alliances).

A successful stakeholder analysis will help you:

Start talking early to the right people, so that you can identify any major barriers to your work, and identify the people who can help you overcome those barriers. There is evidence that projects that engage with stakeholders early engender a greater sense of ownership amongst stakeholders, who are then more likely to engage throughout the lifetime of the project, and implement the recommendations of the work you have done together.

Know who you need to talk to: don’t just open your address book or talk to the ‘usual suspects’. Find out who might lose out, as well as who will benefit. Find out who is typically marginalized and left out, as well as the people and organisations that everyone knows and trusts. For example, Bec Colvin suggests drawing on methods from the arts to identify stakeholders using tacit knowledge or past experience. Those who are left out are usually the first to question and criticize work that they feel no ownership over.

Know what they’re interested in: you need to have a clear idea of the research issue at stake before you will be able to effectively identify stakeholders. But that doesn’t mean that the research questions and issues you explore together should be set in stone. As you begin to identify stakeholders, you will find out more about the nature of their stake in your research, and you may need to broaden your view of what is included in your work, if everyone is to feel that their interests are included.

Find out who’s got the most influence to help or hinder your work: some people, organisations or groups are more powerful than others. If there are highly influential stakeholders who are opposed to your project, then you need to know who they are, so that you can develop an influencing strategy to win their support. If they support your work, then it is also important to know who these stakeholders are, so you can join forces with them to work more effectively. There will be some influential stakeholders who have relatively little interest in your work. For example, they may have a broad remit that includes many issues that are more important and urgent to them than the specific focus of your research. Influential individuals are often busy and inaccessible, and you may need to spend significant time and energy getting their attention, before you are able to access their help.

Find out who is disempowered and marginalized: stakeholder analysis is often used to prioritise more influential stakeholders for engagement. Although time and resources may be limited, it is important not to use stakeholder analysis as a tool to further marginalize groups that are already disempowered and ignored. Many of these groups may have a significant interest in your research, but very little influence over the issues you are researching, and little capacity to help you achieve the impacts you want.

Identify key relationships so you avoid exacerbating conflicts and can create alliances that empower marginalized groups. It can be incredibly valuable to know in advance about conflicts between individuals, organizations or groups, so that you can avoid inflaming conflict and where possible resolve disputes. Through stakeholder analysis, it can sometimes become possible to create alliances between disempowered groups and those with more power, who share similar interests and goals, thereby empowering previously marginalized groups.

Methods for stakeholder analysis

Doing a proper stakeholder analysis doesn’t have to take a lot of time. We would recommend that you invite a small number of non-academics who know the stakeholder landscape well to help you with this task. But if you are short on time, then even if you just fill out the table below with your research team, you will be able to do far more impactful research than you would have done if you did not take this step.

The following methodology will take you approximately 2 days to complete, including between half a day and a day for an initial workshop, followed by a series of half hour telephone interviews to check your findings with key stakeholders (which is also a great opportunity to get their feedback on the focus of your research and start getting ownership as you adapt your work to stakeholder interests). The following steps are designed to be straight-forward and replicable, but this does not mean that they should be inflexibly applied. Local circumstances may require these steps to be adapted, to ensure that the stakeholder analysis is a tool that brings stakeholders together and facilitates active engagement in research.

1. Identify 2-4 cross-cutting stakeholders: Identify between 2-4 individuals from cross-cutting stakeholder organisations who operate at the scale of your research (if you have multiple study sites, you may need to do this for each site). The key criterion for selection is their breadth of interest in the issues you are researching, so that they are familiar with the widest possible range of organisations that might have a stake in your work. Aim to represent a range of different perspectives on the issue, so that you can facilitate debate about the relative interest and influence of different stakeholders (e.g. someone from a Government department or agency and someone from an NGO, not just people from different Government departments)

2. Invite cross-cutting stakeholders to half-day workshop: only 2-4 stakeholders plus project team should be present, as it is not the aim to represent all stakeholders at this workshop (this isn’t possible as we have yet to systematically identify them). This workshop should take approximately 4 hours (half a day), but if there is time, it is more relaxed to do this over a day:

Clearly establish the focus of the research that you think individuals, organisations or groups might have a stake in: it is important to be as specific as possible about your focus, so you can clearly identify who has a stake and who does not. You might want to consider the geographical or sectoral scope of the project (e.g. are you interested only in stakeholders at a local level, or is this a national issue that may involve national (or international) stakeholders? Which sectors of the economy or population are relevant to the research? A discussion about these sorts of questions at the start of the workshop should clarify any differing perceptions amongst the group, to avoid confusion later (approx. 15 mins);

Choose a well-known stakeholder organization and run through the stakeholder analysis for this organisation as an example. Draw copies of the extendable matrix below on flip chart paper and stick to walls, so that everyone can see what is being done. Explain that interest and influence can be both positive and negative (e.g. a group’s interests might be negatively affected and they may have influence to block as well as facilitate) (approx. 10 mins);

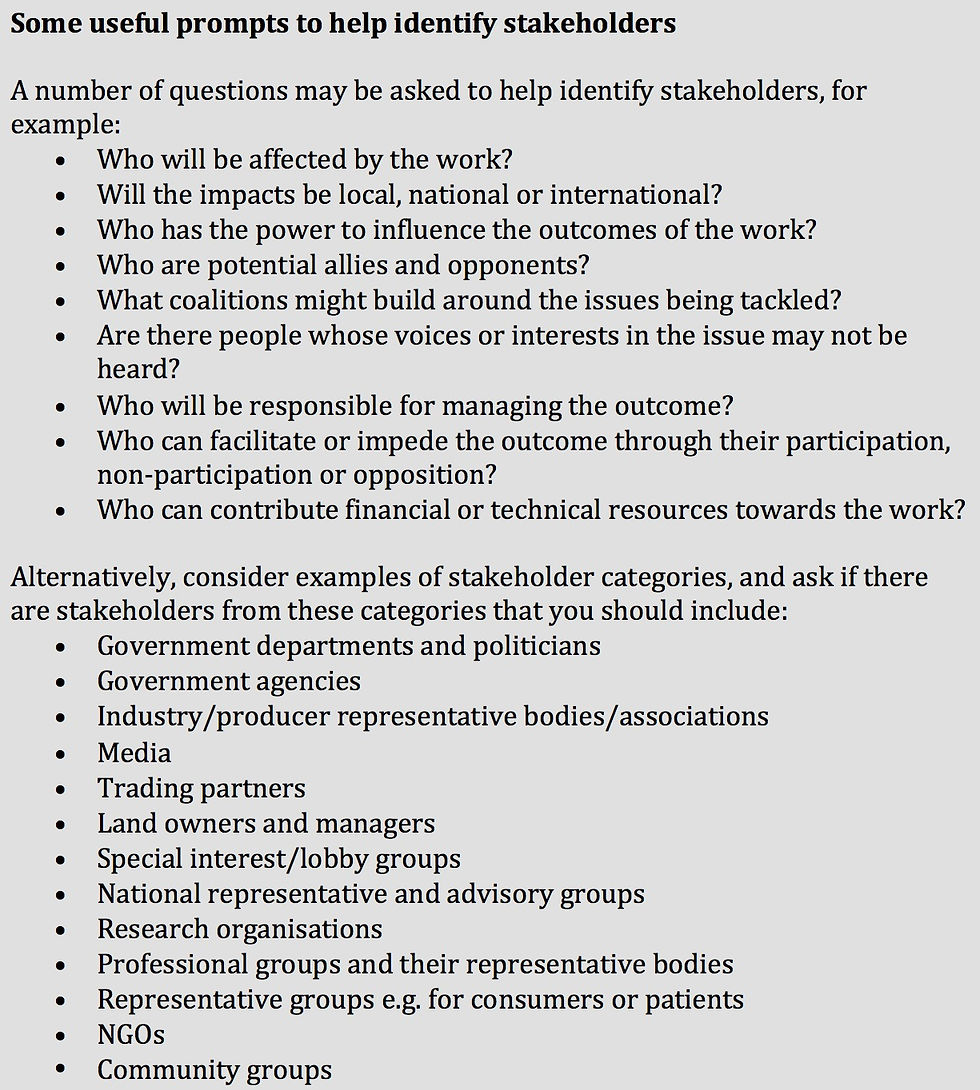

Ask participants to identify organisations, groups or individuals who are particularly interested and/or influential, and list them in the first column of the matrix at the bottom of this page. We've provided you with a blank table and a worked example to illustrate how this might look. Use the questions in the box below as prompts to help you identify as many stakeholders as possible (approx. 15 mins);

As a group work through each of the columns in the matrix, one stakeholder at a time, discussing the nature of their interest and reasons for their influence etc., and capturing the discussion as best as possible in the matrix (getting participants to capture points on post-it notes where necessary to avoid taking too long) (approx. 1-2 hours);

Take a break, and then invite participants to use the remaining time working individually to complete the columns for all the remaining stakeholders, adding rows for less interested and influential stakeholders as they go. Remind people to try and identify groups who might typically be marginalised or disadvantaged, but who still have strong interest in the research (approx. 1 hour);

Ask participants to check the work done by other participants, adding their own comments with post-it notes where they disagree or don’t understand (approx. 15 minutes);

Facilitate a discussion of key points people feel should be discussed as a group about stakeholders where there is particular disagreement or confusion and resolve these where possible (accepting differing views where it is not possible to resolve differences) (approx. 30 minutes);

Identify key individuals to check findings with after the workshop. Identify up to 5 individuals from particularly influential organisations, trying to get as wide a spread of different interests as possible (to do this, it may be necessary to start with a longer list and then identify people who are likely to provide similar views to reduce the length of the list). Finally consider if there are any particularly important stakeholders who have high levels of interest but low influence, who you do not want to marginalize and go through the same process, to arrive at a list of around 7-8 individuals who you can check the findings of the workshop with (approx. 20 mins).

3. Interview key individuals to check that no important stakeholders have been missed. Depending on the sensitivity of the material collected, you may only want to share the list of stakeholder organisations and their interests (not level of interest or anything else). For some of the individuals, it may be possible to check all columns in the matrix, but beware that some organisations may be upset that workshop participants perceive them to have low interest and/or influence. If the list of stakeholders from the workshop is sent in advance, these interviews should take no longer than 30 minutes each, and can be done by telephone.

4. Depending on how much the analysis changes from the workshop, you may want to check the amended version with workshop participants and make final tweaks.

5. Write-up: some columns can easily be converted into graphs, where there is numerical or categorical data involved. Consider carefully whether you want to all qualitative data to be made publically available in a form that is linked to specific named organisations and individuals, especially where this concerns conflicts between organisations. For a publically available version of the report, types of conflict may be summarized and the nature of stakes and types of influence may be summarized for different types of stakeholder, accompanied by graphs of numerical/categorical data e.g. farming organisations are most likely to be interested in certain aspects and have most influence over certain policy areas. The full stakeholder analysis matrix should be retained for use by the project team.

Images from a stakeholder analysis conducted for the UK Government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, February 2016

Do your own stakeholder analysis with this template

We've developed an editable template that will guide you through doing your own stakeholder analysis, based on Prof Reed's "extendable matrix" approach - see Reed et al. (2009) and Reed and Curzon (2015) .

Download our stakeholder analysis matrix ( Word | PDF )

To give you a sense of what this can look like, you can view or download a worked example below, based on a hypothetical stakeholder analysis developed for a project funded by the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida), led by the Regional Environment Centre in cooperation with local partner IUCN ROWA. The Water SUM project , for which this was developed, is using this template to train country teams how to conduct a stakeholder analysis in preparation for local water security action planning in collaboration with stakeholders.

Click on the image above to view the full example

Alternatively, take a look at this stakeholder analysis we did for the UK Government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to identify stakeholders in honeybee health, which informed the development of their National Pollinator Strategy last year. This project was done over a year, and involved Social Network Analysis and the analysis of many in-depth interviews, but you can get what you need for most research projects over a couple of days, using the methods described above. You can see the sort of thing that is possible with an in-depth stakeholder analysis like this in this presentation .

The template above is based on the template used in Fast Track Impact training. Both templates have columns that rate and then characterise the nature of people’s interest and their influence over the research and its impact. You can adapt the columns in this matrix to fit with your own purpose, bearing in mind that the more columns you add, the longer your workshop will take.

Thanks to WaterSUM project (www.watersum.rec.org) implemented by the Regional Environmental Center (www.rec.org) for funding that led to the production of this blog.

Follow us on Twitter

#stakeholderanalysis #stakeholders #beneficiaryanalysis #beneficiaries #pathwaytoimpact #researchimpact #methods

- Research Impact Guides

Related Posts

Tips and tools for making your online meetings and workshops more interactive

How to integrate impact into a UKRI case for support

Presenting with Impact

Taking Research Outcomes to Target Beneficiaries: Research Uptake, Meaning and Benefits

- First Online: 10 December 2021

Cite this chapter

- Clara Chinwoke Ifeanyi-obi 3

Part of the book series: Women in Engineering and Science ((WES))

443 Accesses

Every research is targeted to stimulate change through generating outcomes that proffer solutions to identified problems. Until these outcomes are mainstreamed into policy and practice, the expected research impact is yet to be felt. Researchers are therefore expected to possess the capacity not only to conduct viable research but to also mainstream their research findings into policy. This chapter is aimed at enlightening researchers on the importance of taking their research outcomes to target beneficiaries. It explained the concept of research uptake, highlighted the benefits of conducting research uptake to both the target audience and researchers and further prescribed a guide to researchers on the process of conducting research uptake. Researchers will find in this chapter guide on when to begin planning their research uptake programme, how to choose the right research uptake to implement, setting realistic objectives for their uptake programme, effective stakeholder mapping, developing effective uptake message, identifying effective communication channel and producing materials that clearly communicate uptake message.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Guide to developing and monitoring a research uptake plan. Malaria consortium. Disease control, Better health. https://www.google.com/search?q=Guide+to+developing+and+monitoring+a+research+uptake+plan&rlz=1C1YTUH_enNG942NG942&oq=Guide+to+developing+and+monitoring+a+research+uptake

Research on Food Assistance for Nutritional Impact (REFANI). (2016). What does it mean to implement a research uptake strategy? Experiences from REFANI Consortium

Google Scholar

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Sekeran. (2006). Research methods for business. A skill building approach . Wiley.

Madukwe, M. C., & Akinnagbe, O. M. (2014). Identifying research problems in Agricultural Extension. In M. C. Madukwe (Ed.), A guide to Research in Agricultural Extension . Agricultural Society of Nigeria (AESON).

Department for International Development. (2016). Research uptake: A guide for DFID-funded research programmes. Department for International Development and Association of Commonwealth Universities. Research uptake in a virtual world. A guide

Fisher, J. R. B., Wood, S. A., Bradford, M. A., & Kelsey, T. R. (2020). Improving scientific impact: How to practice science that influences environmental policy and management. Conservation Science and Practice., 2 , e210. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.210

Article Google Scholar

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition . Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4.

Wejnert, B. (2002). Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: A conceptual framework. Annual Review of Sociology, 28 , 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141051.JSTOR3069244.S2CID14699184

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Clara Chinwoke Ifeanyi-obi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Clara Chinwoke Ifeanyi-obi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Biochemistry, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Eucharia Oluchi Nwaichi

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ifeanyi-obi, C.C. (2022). Taking Research Outcomes to Target Beneficiaries: Research Uptake, Meaning and Benefits. In: Nwaichi, E.O. (eds) Science by Women. Women in Engineering and Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83032-8_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83032-8_3

Published : 10 December 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-83031-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-83032-8

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

How to disseminate your research

Published: 01 January 2019

Version: Version 1.0 - January 2019

This guide is for researchers who are applying for funding or have research in progress. It is designed to help you to plan your dissemination and give your research every chance of being utilised.

What does NIHR mean by dissemination?

Effective dissemination is simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay.

Research is of no use unless it gets to the people who need to use it

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department of Health

Principles of good dissemination

Stakeholder engagement: Work out who your primary audience is; engage with them early and keep in touch throughout the project, ideally involving them from the planning of the study to the dissemination of findings. This should create ‘pull’ for your research i.e. a waiting audience for your outputs. You may also have secondary audiences and others who emerge during the study, to consider and engage.

Format: Produce targeted outputs that are in an appropriate format for the user. Consider a range of tailored outputs for decision makers, patients, researchers, clinicians, and the public at national, regional, and/or local levels as appropriate. Use plain English which is accessible to all audiences.

Utilise opportunities: Build partnerships with established networks; use existing conferences and events to exchange knowledge and raise awareness of your work.

Context: Understand the service context of your research, and get influential opinion leaders on board to act as champions. Timing: Dissemination should not be limited to the end of a study. Consider whether any findings can be shared earlier

Remember to contact your funding programme for guidance on reporting outputs .

Your dissemination plan: things to consider

What do you want to achieve, for example, raise awareness and understanding, or change practice? How will you know if you are successful and made an impact? Be realistic and pragmatic.

Identify your audience(s) so that you know who you will need to influence to maximise the uptake of your research e.g. commissioners, patients, clinicians and charities. Think who might benefit from using your findings. Understand how and where your audience looks for/receives information. Gain an insight into what motivates your audience and the barriers they may face.

Remember to feedback study findings to participants, such as patients and clinicians; they may wish to also participate in the dissemination of the research and can provide a powerful voice.

When will dissemination activity occur? Identify and plan critical time points, consider external influences, and utilise existing opportunities, such as upcoming conferences. Build momentum throughout the entire project life-cycle; for example, consider timings for sharing findings.

Think about the expertise you have in your team and whether you need additional help with dissemination. Consider whether your dissemination plan would benefit from liaising with others, for example, NIHR Communications team, your institution’s press office, PPI members. What funds will you need to deliver your planned dissemination activity? Include this in your application (or talk to your funding programme).

Partners / Influencers: think about who you will engage with to amplify your message. Involve stakeholders in research planning from an early stage to ensure that the evidence produced is grounded, relevant, accessible and useful.

Messaging: consider the main message of your research findings. How can you frame this so it will resonate with your target audience? Use the right language and focus on the possible impact of your research on their practice or daily life.

Channels: use the most effective ways to communicate your message to your target audience(s) e.g. social media, websites, conferences, traditional media, journals. Identify and connect with influencers in your audience who can champion your findings.

Coverage and frequency: how many people are you trying to reach? How often do you want to communicate with them to achieve the required impact?

Potential risks and sensitivities: be aware of the relevant current cultural and political climate. Consider how your dissemination might be perceived by different groups.

Think about what the risks are to your dissemination plan e.g. intellectual property issues. Contact your funding programme for advice.

More advice on dissemination

We want to ensure that the research we fund has the maximum benefit for patients, the public and the NHS. Generating meaningful research impact requires engaging with the right people from the very beginning of planning your research idea.

More advice from the NIHR on knowledge mobilisation and dissemination .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Scope and Delimitation & Benefits and Beneficiaries of Research

2020, Division of Palawan

This module was designed and written with you in mind. It is here to help you master the Scope and Delimitation and Benefits and Beneficiaries of Research. The scope of this module permits it to be used in many different learning situations. The language used recognizes the diverse vocabulary level of students. The lessons are arranged to follow the standard sequence of the course. But the order in which you read them can be changed to correspond with the textbook you are now using. The module is divided into Two (2) lessons, namely: Lesson 1- Scope and Delimitation of research Lesson 2- Benefits and Beneficiaries of research After going through this module, you are expected to: a. define scope and delimitation of research; b. appreciate the scope, limitation and delimitation; and, c. write the benefits and beneficiaries of research.

Related Papers

Asfarasin Maricar

mabuta mustafa

lecture notes

md. faruk miah

Michael Evans

Farhan Ahmad

mahrukh fatima

For Students, Scholars, Researchers, Investigators, Trainees and Scientists. “If I have seen a little further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Isaac Newton. This book on research is an attempt to try to answer the basic fundamental questions that come to the minds of young students, researchers, scholars, investigators, trainees or scientists. It is an outcome of collaboration between 43 researchers from 11 different countries (Pakistan, India, United States, Iran, United Kingdom, Nepal, Canada, Greece, Poland, Japan and Australia). Although there is a lot of literature available to answer the queries that come to the mind of a young investigator, the language is often too complex and difficult to understand and thus, aversive. Some of these teaching materials sound more like experts talking to each other. This book would act as a catalyst in providing useful reviews and guidance related to different aspects of research for students who need to be inducted and recogniz...

Emil Ilyasov

Mustafe Hassan Dahir

Kiyoung Kim

What is the research for in the society? We may imagine the professionals engaged in these activities, shall we say, university professors, researchers in the public and private institutions, and even the lay inventors at home or in the neighborhood. The research is related with some of knowledge or ideas, which, however, should be creative and original. It is the main function of those professionals, and can develop in dissemination of the findings produced by research. It frontiers the knowledge of humans which enables a better view of world and generates the public welfare. The scholars are often those professionals who are required or in some cases, squeezed to produce an original contribution to the specific field of academy. As the society develops, we now require a scientific knowledge beyond the plain understanding of the nature and society. The scientific knowledge is qualified of some elements, i.e., evidence-based, universal frame to be applied, sense of understanding, pragmatic in comprehension or application, more persuasion on theory, paradigm, typologies, intersubjectivity, empirical relevance and so. It informs a philosophy of humans, makes them conscientious and knowledgeable, as well as enhances a professional performance for not only their field but also other disciplines. For example, the criminal justice system borrows the idea or information confirmed by other disciplines, psychology and sociology notably. What is the Durham rule in the excuse of culpability? The scope of rule could not enjoy a persuasion if not to be supported by the works of psychologists. The scientific knowledge perhaps could recourse its most salient dynamism in coupling with an economic exploitation. A cultivation of knowledge to serve the economic use and its industrialization reveals it’s competitive edge in the society. The kind of concepts, information age, e-technology, and intellectual property rights are leading the present time of narrative as we see routinely. May new laws, and new concept of e-education or e-government, GMO products as well as the travel of universe in the near future also follow that the updated profile of scientific knowledge on the engineering and natural science contributed to expand our horizon of subsistence.

RELATED PAPERS

ACTA CLINICA …

Elizabeta Topic

IRJET Journal

Gilmar Henz

Benjamin Haywood

Cadernos de Saúde Pública

João Erlon Rosa Peres

Neetu Thakur

Ayşegül Karataş

asitha kodippili

Finding New Ways to Engage and Satisfy Global Customers

Satish Murari

Applied and Environmental Microbiology

jongshin yoo

COLLOQUIUM AGRARIAE

Eduarda Damacena

Boletim de Geografia

FREDERICO YURI HANAI

DNA and Cell Biology

Ayşe Nur İnci Kenar

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association

Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe

German W. Cabassa Barber, Ph.D.

2010 Second International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX)

iman mossavat

Sumaia Inaty Smaira

Synthetic Metals

Martin Baumgarten

Jurnal Aplikasi Bisnis dan Manajemen

Hendro Sasongko

Journal of Management Studies

Bone marrow transplantation

Claudio Giardini

EGS - AGU - EUG Joint Assembly

Oleg Melnik

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

horacio rodriguez rilo

Progress in Organic Coatings

Monica Periolatto

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2012

Benefits and payments for research participants: Experiences and views from a research centre on the Kenyan coast

- Sassy Molyneux 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 ,

- Stephen Mulupi 1 ,

- Lairumbi Mbaabu 4 &

- Vicki Marsh 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Medical Ethics volume 13 , Article number: 13 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

64 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is general consensus internationally that unfair distribution of the benefits of research is exploitative and should be avoided or reduced. However, what constitutes fair benefits, and the exact nature of the benefits and their mode of provision can be strongly contested. Empirical studies have the potential to contribute viewpoints and experiences to debates and guidelines, but few have been conducted. We conducted a study to support the development of guidelines on benefits and payments for studies conducted by the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

Following an initial broad based survey of cash, health services and other items being offered during research by all programme studies (n = 38 studies), interviews were held with research managers (n = 9), and with research staff involved in 8 purposively selected case studies (n = 30 interviewees). Interviews explored how these ‘benefits’ were selected and communicated, experiences with their administration, and recommendations for future guidelines. Data fed into a consultative workshop attended by 48 research staff and health managers, which was facilitated by an external ethicist.

The most commonly provided benefits were medical care (for example free care, and strengthened quality of care), and lunch or snacks. Most cash given to participants was reimbursement of transport costs (for example to meet appointments or facilitate use of services when unexpectedly sick), but these payments were often described by research participants as benefits. Challenges included: tensions within households and communities resulting from lack of clarity and agreement on who is eligible for benefits; suspicion regarding motivation for their provision; and confusion caused by differences between studies in types and levels of benefits.

Conclusions

Research staff differed in their views on how benefits should be approached. Echoing elements of international benefit sharing and ancillary care debates, some research staff saw research as based on goodwill and partnership, and aimed to avoid costs to participants and a commercial relationship; while others sought to maximise participant benefits given the relative wealth of the institution and the multiple community needs. An emerging middle position was to strengthen collateral or indirect medical benefits to communities through collaborations with the Ministry of Health to support sustainability.

Peer Review reports

Debates on the ethics of international health and health research have shifted over the last twenty five years away from a focus on the relevance and value of informed consent, towards considering broader challenges such as the potential for exploitation in international research, the need to make research responsive to local needs of host communities, and the implications of research for international relations and law [ 1 , 2 ]. This shift is related to growing recognition that focusing on the protection of research participants through reviewing research proposals before they begin is inadequate; that there is a need to look beyond the design of studies and to see how research is actually being conducted on the ground [ 2 ]. The importance of social science studies for understanding the dilemmas that are faced and generated, and the ethical implications of how these are resolved, have begun to be highlighted [ 3 ]. Depending on their design, such studies can fall within the spectrum of approaches termed ‘empirical ethics’ [ 4 , 5 ], and may incorporate deliberative elements [ 6 ].

Within this general movement in ethical focus, there is consensus that unfair distribution of the benefits of research is exploitative and that - as a moral wrong - it should be minimised. One approach to doing this is to provide ‘fair benefits’ to participants and their communities [ 7 , 8 ]. There is still debate over what constitutes fair benefits, and over the appropriate balance in benefits between micro level issues of justice and broader social determinants of health at the macro level [ 7 – 13 ]. However, increasing benefits to participants and communities involved in research is widely agreed as one approach to minimize exploitation.

The fair benefits framework distinguishes between benefits from both the conduct and results of research, and between:

· direct benefits to those enrolled in the research (for example diagnostic tests, distribution of medications and evaluation services); and

· collateral or indirect benefits not targeted specifically at those involved in the research (for example providing antibiotics for respiratory infections, health service provision, digging of bore holes for clean water, or research capacity building) [ 7 , 8 , 14 ]. Beneficiaries of collateral benefits might be research participants, other identifiable individuals such as family members, or the general community.

In considering fair benefits for research, a widely accepted ethical condition is that the research must pose few risks to individual participants, or the benefits to them should outweigh the risks [ 7 ]. Where potential risks outweigh benefits to participants, the social value of the research should justify the risks [ 15 , 16 ]. It is also increasingly argued that the risk-benefit ratio for the communities within which the research is conducted should be favourable [ 15 ]. However, the exact nature of the benefits that can and should be provided for various studies in different settings, and their mode of provision, remain ill-defined and often strongly debated. The boundary between ‘benefits’ and obligations, for example with regards to ancillary-care in health, is also complex and contested [ 17 – 19 ], as will be returned to in the discussion of this paper.

The notion of undue inducement, and the paradoxical relationship with exploitation, has received particular attention in benefits debates. As Koen et al. [ 20 ] have argued, inducement by itself can be ethically justifiable, even if it contributes to participants doing something that they might otherwise not have done. However inducement becomes ‘undue’ where an excessive offer distorts decision-making, leading to individuals participating against their better judgment. Also of concern with regards to inducement is the potential to disproportionately attract the poor, and the fabrication of information in order to access study benefits. The dilemma, raised by Macklin (1989) and summarized by Ballantyne is: ‘ offer participants too little and they are exploited, offer them too much and their participation may be unduly induced ’ [ 21 ]; p 179. This paradox is particularly stark in international collaborative research, where research institutions and bodies may be relatively wealthy, operating in and among relatively low income settings and populations.

One specific form of benefit in research is payment of cash. Cash payments which reimburse or compensate for time and inconvenience are not considered benefits, and are widely accepted in international guidelines. For these forms of payment, the challenge is the limited amount of operational guidance to set appropriate payment levels. More controversial are cash payments as incentives to participate in research, or as appreciations for contributions to the research [ 20 ]. The specific additional concern about money as a benefit (beyond undue inducement) is the potential to commercialize an altruistic endeavor. Those in favour of financial payments argue that altruistic motives are not incompatible with receiving pay, that research has long been commercialized for other research stakeholders, and that participants are not only motivated by money [ 20 ]. A particular concern expressed informally in low income settings is that populations should not be deprived of potential payments simply because of their poverty as this leads to a double inequity: both poverty and inability to benefit financially.

Debates on benefits and payments in all low income settings are hampered by relatively little information on what is currently happening on the ground, and on the range of stakeholders’ views on current practice. An exception is work by Lairumbi et al. [ 22 – 24 ] which explores perceptions of, and experiences with, benefits among a diverse range of research stakeholders across Kenya. In this paper we present a separate but complementary set of data. We explore views and experiences with regards to benefits and payments from a diverse range of studies conducted by one large and long-term multi-disciplinary research programme in Kenya - the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi - and consider the implications for institutional guidelines aimed at ensuring fair involvement of participants. We focus on the direct and collateral ‘benefits’ (all cash, health services and other items) offered to study participants and to community members over the course of the conduct of studies, as opposed to post study benefits, or aspirational benefits.

KEMRI- Wellcome Trust Programme in Kilifi

The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Programme is a collaboration between the KEMRI Centre for Geographical Medicine Research, Coast (CGMRC), and the Wellcome Trust, UK. KEMRI is a parastatal organisation under the Ministry of Health (MoH), with 10 research centres in Kenya, of which the CGMRC is one of the largest. The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust research programme (KEMRI/WT) was established in 1989. It has grown enormously over the last twenty years, now employing over 800 staff between sites in Nairobi and Kilifi, and conducting a wide range of interdisciplinary research including clinical, basic science, epidemiological and public heath aspects of major childhood and adult diseases of concern in Kenya. A core aim of the programme is strengthening regional capacity to conduct and lead internationally competitive research.

This paper focuses on work conducted in the largest of the two sites, Kilifi. Kilifi district is on the coast of Kenya, with residents primarily from the Mijikenda ethnic group. There are very high levels of poverty, and low levels of literacy across the district. As described in greater detail elsewhere [ 25 ], a key feature of the Kilifi work has been its’ deliberate development within a District Hospital, with much research being carried out in a “real world environment” serving a rural community. The research centre provides support to the hospital to ensure a good standard of care is available to those using the departments where research is conducted, regardless of their involvement in research. This is a form of collateral benefit to the general community as a result of the research programme having a long-term presence in the area, with the additional resources including medical and clinical officers, paediatric drugs and equipment and a paediatric intensive care ward. Within the community, clinical services are supported at specific government health centres and dispensaries.

Every study carried out by the programme is scrutinised in advance by local and independent national and international scientific and ethical review committees. Over the last ten years, informed by social science research activities (see for example [ 25 – 29 ]), both programme wide and study specific community engagement activities have been strengthened. For example a large network of KEMRI community representatives elected by community members has been established, and the amount and type of interactions between research staff and community leaders and ‘ordinary’ community members has been increased. Interactions have increased in communities and within the research programme and hospital.

The research presented in this paper was initiated out of an institutional interest in developing locally appropriate guidance on benefits and payments for the diverse range of studies conducted in Kilifi. From the outset, it was clear that relatively high risk studies – such as phase 1 and 2a trials - needed separate consideration with particularly careful scrutiny on benefits and payments by the Ethics Review Committee. These studies were therefore not discussed and are not included in the considerations outlined in the rest of this paper.

Data collection was in two main phases: an initial audit of current practice and experiences and views from front-line staff involved in distributing benefits; and a workshop involving a wide range of research staff and some MoH managers.

Audit of current practice

The audit involved an initial email survey followed by semi-structured interviews with principal investigators and interface staff involved in eight purposively selected case studies. These data were supplemented by interviews with key informants expected to have relevant cross-study information.

Email survey

56 principal investigators leading active Kilifi based studies were contacted to identify studies that were still in recruitment, data collection, analysis or write-up stages. Semi-structured questionnaires were filled for each of the 38 active (sub) studies identified (n = 24 PIs). The questionnaire for these studies covered: the nature of services, payments and other items (‘benefits’) offered to participants, the intended recipients of benefits, stage of study at which benefits are given, and any community benefits.

In-depth interviews

On the basis of the data gathered above, eight studies were purposefully selected as case studies. Selection was based on maximising diversity among the case studies with regards to: duration of participant involvement; age and health status of study participants; whether studies were facility or community based; whether studies were based only in Coast Province or multi-centre international studies; level of risk in studies; and whether any money was given to participants. A summary of the case studies is presented in Table 1 . Study PIs and/or their Project managers (n = 11) were individually interviewed while the fieldworkers of two studies (n = 19) participated in two FGDs. Interviews explored in more detail what benefits were given to whom and why, how benefits are communicated to participants and wider communities, and their experiences, views and recommendations with regards to benefits and payments.

Individual and group interviews covering similar topics were held with nine key staff members including community facilitators, the head of clinical trials, and the research coordinator based at a dispensary in the district where there has been significant research activity.

Consultative workshop

On the 15 th of December 2009, a workshop to discuss current and future policies and practices around payments and benefits to research participants and communities for KEMRI/WT studies was held in Kilifi. 48 people attended the workshop, representing different cadres of staff at the research centre, including senior and mid-career scientists, research officers, community liaison staff, field workers, doctors and nurses. Non-KEMRI participants included the District Medical Officer (DMO) and nursing officers representing Kilifi District Hospital. Professor Mike Michael Parker, a bioethicist and Director of the Ethox Centre at Oxford University, UK, facilitated the planning of the workshop and the final plenary discussion.

Given that an important objective of the workshop was to propose approaches to payments and benefits for different types of research in Kilifi, the workshop included : 1) presentation of a review of relevant literature and the findings of the above audit; 2) six small group discussions bringing together staff with similar experience on appropriate individual and community benefits for a series of hypothetical studies designed on the basis of the audit (Table 2 ); and 3) a final plenary session where issues raised in the small groups were discussed in more detail. For the small group discussions, topics allocated to specific groups to discuss in more detail in relation to each scenario outlined in Table 2 were:

· Compensation for travel: Groups 1 and 2: field staff and community facilitators

· Medical benefits to participants: Groups 3 and 4: research assistants and medical staff

· Collateral benefits to communities: Groups 5 and 6: senior researchers and MoH managers

In each case, the specific areas of interest for discussion about each type of study were: should this benefit be given, and if so what specifically should be given, how and to whom? Groups were also asked to consider whether there should be any flexibility and how would this be managed.

Following the workshop, a draft report was circulated to all participants for their comments and inputs, and issues documented as needing further resolution taken up by a small group consisting of two experienced community facilitators in the research programme (who are local residents, including the community liaison manager), a clinical trials manager (who is also a clinician), and two social scientists (SM and VM).

Data management and analysis

All audit interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim shortly thereafter. Three authors independently identified key themes, and following discussion agreed on themes to group key data. Summaries of data were used to develop the ideas and discussion guides for the workshop. At the workshop, notes were made by specially allocated note takers from both the small group and plenary discussions. These notes were drawn upon by the same three researchers to highlight areas of agreement, and areas of debate and disagreement requiring further discussion or research by the small group formed to take forwards discussions and agreements post workshop.

In this section we bring together the data from the audit and the workshop, to illustrate what is happening on the ground in Kilifi regarding each major form of benefit or payment, including challenges and negative impacts, and views on what should happen. Following an overview of types and levels of benefits across all studies, we look in turn at experiences with: medical benefits, travel costs, other benefits and compensation for time. The cross-cutting issues relevant to developing guidelines, including the importance of community level collateral benefits in low income settings, and the need for flexibility and careful consideration of communication issues in policies and procedures, are highlighted in the discussion.

Types and levels of benefits offered

From reported data in the audit, with the exception of the verbal autopsy study, which involved a 30–45 minute interview only with adults in their homes, all studies offered some form of benefit or payment to participants. Table 3 shows the benefits and payments given by the seven studies, illustrating not only the diverse range, but also the centrality of direct and collateral medical benefits, and the reimbursement of travel expenses. Other types of benefits included provision of food for individuals, and other small gifts such as books and pens. In general, the levels of collateral benefits for individuals increased with studies seeking to involve participants for longer, and where an (experimental) intervention was involved. For example the benefits for individuals in the malaria vaccine study (MV) and the Immunology study (Immuno) were greater than that of the TB study or the RSV study.

Overall the workshop discussions on the scenarios supported the general trend of more benefits for longer-term/higher risk studies. There was a clear overall agreement that participants should not be made worse off by their participation in any research. It was felt that if the short and low risk activities illustrated in scenarios 1 and 2 in Box 1 had no costs – direct or hidden – it was appropriate not to offer any benefit or payment beyond an appeal to aspirational benefits, and showing common courtesy through for example providing refreshments and research findings, where appropriate. An area of debate (discussed in more detail below) was how much time needs compensation, and what kind of compensation is appropriate for that time. The recommended range of collateral benefits for scenarios 3 and 5, both of which require repeated interactions with well children, were relatively high, to compensate for the relatively large amount of time involved in these studies, and to minimize drop-outs and monitor health. Beyond the payment of direct costs and showing common courtesy, the main benefits considered to be appropriate were diagnosing, treating and referring study children, and providing community benefits such as strengthened dispensary services. The debate (also discussed in greater detail below) was on whether siblings and parents can access health care benefits, and how this is balanced by strengthening community benefits. In scenario 4, there were considered to be significant direct benefits built into the trial design, and significant community benefits as part of wider support to the hospital, and some concern that continuing to increase the collateral benefits to participants might compromise voluntariness in informed consent.

Experiences with regards to specific benefits, payment and other items

Medical benefits.

There was a general perception that medical services are often the most appropriate form of benefit given that health care is close to our area of interest and expertise, and that this form of benefit minimizes the move towards a commercialization of the research encounter. All of the seven studies offering benefits provided some form of direct medical benefit to study participants (Table 3 ), with details of the package depending on the study. In addition to free treatment of the disease or problem of interest (for example clinical shock, TB, malaria, RSV, or HIV), study participants usually received free consultation and treatment for other minor or acute illnesses over the course of the study, including out of hours, and in some cases (e.g. PS) without queueing? Other treatment included in most studies were referral of more complex or chronic illnesses identified over the course of the study to other government facilities, including vehicles or transport to the referral facility (PS), costs of doing diagnostic tests e.g. X-rays (HIV) and medical fees (Immuno, MV).

All studies included collateral medical benefits to non-participants through for example strengthening of the general services of a facility for all patients with a similar problem. Specific support offered included improved laboratory facilities for TB tests (TB); provision of emergency care training for all intensive care ward medical staff (PS), provision of weighing scales, haemacue machines, i-STAT, and thermometers (PS); and provision of medical staff and refurbishment of existing health facilities (MV).

The audit and workshop group discussions highlighted several challenges related to medical benefits in studies. One set of concerns was how much of a benefit individuals actually get from a specific study beyond standard of care . The first challenge is that the standard of care in the paediatric wards is already high relative to other district hospitals as a result of programme wide support (see background); support that is described by some senior researchers both as a collateral benefit and as a necessity for researchers to feel comfortable to conduct research in an area with so many unmet health needs, and to minimise inducement. The overlaps between standards of care, collateral benefits and study requirements were illustrated in an interview:

"We took that approach right from the beginning that we would just first set up a platform for TB diagnosis in Kilifi hospital and which is fundamental to doing the study, but also pretty fundamental to the care for children so we set up this platform and we have made it part of standard of care for children with […] so any child who is referred with suspected TB or is admitted with symptoms and signs consistent with suspected TB gets worked up for TB (IDI No. 1, Researcher)."

Despite the relatively high standard of care, sometimes contributed to by individual studies, it was argued that studies often do involve greater observation and investigation in study children, and that this can lead to improved diagnosis and care even within a relatively well equipped ward.

The second challenge is that while researchers describe free treatment as a benefit, there are national policies for exemption of charges for all children aged less than five years. Nevertheless, it was recognised that across the country there is relatively little adherence to exemption policies [ 30 , 31 ], and therefore that free care remains a significant benefit. When combined with transport, or reimbursed fares (discussed next), the medical benefits were therefore felt to be quite significant especially for the scenarios 3, 4 and 5. PIs working on similar studies reported that non-participants regularly asked to join studies, illustrating that benefits are valued.

Another set of concerns related to medical benefits concerned who is eligible and where they can seek treatment from . Regarding the former, the challenge was what to do if parents brought other sick family members for free treatment, or even their neighbour’s children. Interface staff who were approached by individuals not formally eligible for this benefit sometimes found it difficult to refuse a needy case, but were also concerned that providing care would start a precedent for other families and studies. The dilemma could be particularly difficult for members of the index child’s family, with families reportedly commenting that research can introduce unfairness within households, and for example accusations that researchers are interested in the child but not the person who gave birth to him/her:

"In case a parent has been involved in an accident and it is a parent to a study child, the vehicle cannot be offered....they [community members] tell us, “mtoto hakujizaa mwenyewe, alizaliwa na mimi” [this child didn’t give birth to him/herself, I gave birth to him] (FGD no 1; fieldworkers)"

Some study clinicians reported that attending quickly to study children while referring their sick sibling to a long hospital queue felt wrong, and that they would sometimes treat the sibling out of compassion (KI) even where study policy did not support this action. Others would diagnose the non-participants’ problem and then refer them to the hospital pharmacy to buy drugs; thereby at least saving the parent queuing time. But this was difficult where the parent had no money to buy prescribed drugs. Staff described such dilemmas, and having to stick to standard operating procedures (SOPs) set by people who were not present, as incredibly stressful:

"Even we FWs sometimes hurt inside…you may see me growing thin and yet it is stress from the job (laughter)…you are having this enormous burden all on you…(FGD no 1; fieldworkers)"

These challenges were exacerbated by some studies being more inclusive and flexible with regards to assistance of other family members than others. While this would be expected with such different studies, there appeared to be both a lack of standardisation across very similar studies, and problems in communicating clearly about these differences. Related challenges were confusion and sometimes irritation regarding the timing of medical benefits; in some cases participants can receive free treatment at any point over the course of the study (MV), in others it is only when they come back for a specific follow up visit (e.g. PS; TB). The latter can feel short changed, and may be taunted by others:

"…they [non-participants] would tell the participants that, “look, it is only when KEMRI needs to draw blood from your child, that they send you vehicles, but when your child is sick, you trek to hospital just like the rest of us”… (FGD no 1; fieldworkers)"

This phenomenon of local interpretation of perceived differences in benefits between studies leading to confusion and tensions was general to all types of benefits, as discussed more below. One outcome was potential refusal to participate in studies with less tangible benefits:

"[we get told] “No, you are not coming to this house to ask any questions… you take everything [benefits] to the other homes and here you only come to ask questions….No, go to that house… that is your house…(FGD no 2; community facilitators)"

"some would say that, “we are not in the project but we are also seen by the KEMRI doctors (it doesn’t matter that you are seen first)…and we also get lifts-just like you…but only you struggle in the project”… (FGD no 1; fieldworkers)"

At the workshop it was felt that for longer term studies, medical benefits provided should be greater than for short term studies, and that these medical benefits should be extended to participant siblings and other family members wherever possible, not least to help strengthen the relationship with participant families and help ensure retention. There was agreement that overall, support to siblings should at least ensure that the benefits to individuals are not lost through for example a sibling having to queue for care, and that with referrals to other facilities, all costs for the first visit including treatment should be covered. With regards to inter-current illnesses experienced by participants between planned visits in longitudinal studies, for example following discharge from the district hospital, there was a general agreement that these should not be paid for, because there are already significant benefits built into studies, and a requirement for this support would be impossible for many studies.

Travel costs

All of the seven studies aimed to ensure that patients did not incur any travel costs (Table 3 ). Travel costs were therefore either avoided (for example by organising research centre transport to collect people from their homes to facilities; MV study) or refunded. In general, costs were not met for travel that would have happened in the absence of the study. For example fares were not refunded for participants in the TB or RSV studies for their first visit to the hospital, because this travel occurred as part of care seeking before they were recruited in the study.

There were differences across the studies with regards to how fares were refunded, at what level and what specific costs they were supposed to cover or compensate. For example some studies (e.g. Immuno) would give out money in advance, providing funding at each visit to cover the travel costs of a subsequent attendance. Others (e.g. MV) only refunded return fares on arrival for the research visit. Some studies reimbursed set amounts based on known costs of public transport from the participant’s area of residence, while others refunded actual amounts claimed on the day, in some cases only on production of a receipt. Some studies added a small ‘top up’ to allow for purchase of refreshments for the trip, and some paid a small fixed amount of money to those who walked to the facility because they lived close by or could not access public transport. One study (HIV) incorporated into standard ‘travel costs’ some compensation for time spent on the research activity.

Another difference across studies was exactly who had fares covered, and for what services. For example, costs could include those for the child only, or other siblings that the parent might need to travel with, and for one or two parents; and sometimes studies allowed for transport costs in unexpected health emergencies. Emergency assistance was generally offered only in consultation with health facility nurses, and only by the longer term studies out of normal working hours, primarily as a ‘ humanitarian response ’ (MV) or as a way of ‘ being part of the community ’ (Immuno).

"‘We have been encouraged by the MoH not to set up a parallel system… [they] were very categorical that if somebody is unwell they should follow the normal procedure- go to the nurse in the health facility who will call the ambulance…also because of medico-legal reasons…the ambulance comes with a nurse…there is some sort of first aid at hand…(IDI no 8; researcher)"

The audit revealed significant challenges with (re)payment of travel costs, including concerns associated with different approaches across studies, and between the institution and others operating in the area:

"‘Even with fares; a study will give exact fare, another one will give extra - like one and a half the amount that people are charged, so sometimes it brings problems and you know sometimes they are in one study when they complete then maybe another child is in another study, so they are like, “why is it that I was given double fare and now you are giving me only one way” (laughter)…’ (IDI no 6; clinical officer)"

As for medical benefits, this quote hints at the mistrust that can be introduced by these different approaches, or at least by them being inadequately communicated. Another challenge was introduced by perceived lack of fairness or even sense in not extending transport support beyond the index child in a study, as noted above.

Specific concerns raised with giving fares long in advance of appointments were that:

· where money was spent on other pressing needs, parents would sometimes avoid appointments or otherwise fail to turn up, leading to relatively expensive follow up visits to homes, and possibly embarrassment for families, or

· parents may feel unable to change their minds about coming to follow-up visits, having already accepted the money at an earlier stage.

· Other travel payment concerns were that transport receipts were often difficult for parents to obtain, and that amounts claimed were sometimes higher than those incurred. On the other hand collecting participants from home with research vehicles included the possibility of introducing long waits where arrival time at homes were difficult to predict, and difficulties with handling others needing lifts at the same time. Finally, there were some reports of fieldworkers using their own funds to assist participants and finding it difficult to ask for reimbursement from the study team.

At the workshop it was agreed that transport costs incurred specifically for research must always be paid/reimbursed, and should include a little extra to cover for time spent and other needs on the journey (e.g. drink/snacks). There was a suggestion that to maximise fairness and clarity, to minimise potential to negatively impact on informed consent and to simplify administration systems, studies should:

· Set repayments based on where participants live, regardless of whether they actually use that public transport on that day, and therefore even without receipts. The amounts can be calculated depending on the zone participants live in surrounding research facilities, a with everybody from that zone given the highest expected cost from that zone. Amounts per zone should include a small additional amount to actual expected transport cost, to cover for refreshments or unexpected costs for the journey.

· Allow participants to choose whether they wish to be paid in advance for a future visit, or during that future visit

· Ensure travel is reimbursed for one parent and the index child if he or she is five years or above.

Other non-medical benefits

The most common other items offered by studies were food and snacks (five studies) offered when participants were visiting facilities away from home, or – less commonly – when significant amounts of time were taken within households. These were either to compensate for missed meals, as a token of appreciation, or to calm children (sweets and biscuits). Food was provided ready to eat (MV, Immuno, RSV, MV), as money for families to buy their own food (PS), as tickets to exchange for food at selected outlets (HIV), or as dry food for participants to cook themselves as convenient (reported in cross-cutting interviews). Other benefits included notebooks and pens (Immuno) for school-going children. In HIV studies participants were also given T-shirts, lubricants and legal services of a lawyer where charged with minor non-criminal offences such as loitering. Some people also considered the hiring of field workers from the local community as a significant community benefit.

Specific challenges with regards to these benefits (beyond those of other benefits of the amounts and who received these) were reports that some participants felt that very small benefits, juices and biscuits for instance, belittled their contribution, and led to them being taunted by others in the community. A particular concern with regards to t-shirts distributed by one study (HIV) was that some participants reportedly did not want to wear them as they were concerned that they would be stigmatised as having HIV/AIDS.

Financial compensation for time

At present, compensation for time is through the inflated fares described (or fares being given where they are not strictly needed), or through medical and other benefits. There were concerns raised through the audit that compensating for time through inflated transport costs, particularly where no transport costs were actually incurred, raised confusion and suspicion. For the HIV studies, there were reports that this approach risks people falsifying information in order to obtain cash, or concerns about confidentiality.

"some would even lie… they would ask, “how come you are there, what did you say?…Okay, these are the kind of people they want?…Okay, I will just go and say this is what I am…I would say I am MSM… I am a sex worker- that is what they want”. (IDI no 7; research manager)."

"Actually for us, maybe one of the things is the variation of reimbursement…you will say that the uninfected cohort, you will give 350… then you have another one being given 500… then you have someone on the trial getting 600… volunteers challenge us…they really want to know why is it that so and so gets 500…and I can’t tell the person what it is about.. I can’t break confidentiality about their status (IDI no 7; research manager)."

While the latter concern may be particularly applicable to research in stigmatised diseases or populations, lack of clarity about what the payments are for, particularly where somebody has walked to a facility, was reported for several studies, and in the workshop. This lack of clarity, in some cases linked to a broader misinformation about what the research is about and how it differs from standard health checks or treatment, can contribute to disputes within households (for example, concerns from husbands about where the mothers of participant children have received money from and why), and fuel rumours around the aims and objectives of the activities (for example, concerns about whether KEMRI is ‘buying blood’).

"…and what that does to the home dynamics… the decision-making…when you give the woman the fare, and ideally a married woman here is only supposed to be supported by the husband…she is only supposed to get money from the husband; so here is KEMRI coming to give her money…exactly what are you doing to the power relations between the woman and the husband…on top of that you are giving her more than she needs for fare…(IDI no 9; community facilitator)"

"[We are told that] “You know very well that there are no matatus [public transport vehicles] in this area yet you say that this is fare…no… just tell us what this money is, but don’t you say that it is fare”…(IDI no 11; nurse)"

It was agreed at the workshop that time costs – including what somebody might be doing in that time, such as preparing a meal or earning an income - should be properly considered in research planning because these costs are often under-estimated. It was recognised for example that families may often stay at the dispensary waiting for a one hour assessment for far longer than an hour, and that field staff may turn up late to a household for an appointment, causing delays. It was agreed that appreciation and common courtesy should be maximised by minimizing inconvenience to participants, and – especially where the participant leaves home - considering the need to provide snacks or lunches. However the question of if and how to provide a reasonable allowance in cash for ‘lengthy’ research activities (either in homes or away from them) was highly complex, given the different types of income generation people have, diverse incomes and the different approaches research staff took to the issues. Given that there was no simple calculation that we could draw on at the workshop, and that there were concerns and debates about moving towards a more commercial relationship with participants/communities, the area was recommended for further careful research and discussion. Subsequently, the small group formed to take forwards workshop findings have suggested that where significant individual time is taken (for example the exceptional cases of an overnight stay in a facility that would not otherwise be necessary), past research in our area supports payment in accordance with national guidelines on minimum daily unskilled wages. At the time of writing this was 300/= or GBP 2.30 per day in an urban setting.

There is general consensus that fair benefits are essential in international health research, but the exact nature of benefits that should be provided to participants and communities, and their mode of provision, are not clearly defined, and often strongly contested. There has been little detailed research on experiences and challenges with benefits on the ground, particularly from low-income settings, to feed into on-going debates. We explored benefits and payments offered for a diverse range of studies within a large long-term multi-disciplinary research programme in Kenya, using both a descriptive and consultative approach. Although not all relevant parties were involved (most notably absent were study participants or their parents, community representatives, health workers and ethics committee members), we were able to include a broad range of programme staff, including the voices of those who are often excluded from policy discussions: the interface staff who explain and administer benefits and payments to research communities; many of whom are from those communities themselves.

We did not cover some types of collateral benefits from studies to communities, such as employment of local personnel, capacity strengthening of researchers from the region, nor post trial benefits. Also not discussed in detail were the collateral benefits such as clinical staff and services funded by the programme to the paediatric wards at the district hospital, and to government health centres and dispensaries in which research is conducted. Nevertheless, we believe that we have gathered sufficient information to begin to draft institutional guidelines on what ‘ought’ to be done in our setting for studies (both procedural and substantive elements), and to highlight some areas that need further research and discussion.

Challenges with current practice

Our interviews and interactions helped us learn about some of the realities of administering a wide range of benefits and payments on the ground (medical, transport, food and other). A picture emerges of current practice being appreciated by staff and communities, but also being associated with significant issues and challenges which have received little attention in the literature, relative to concerns about undue inducement. Costs to participants that may not be considered for example are lack of common courtesy in research encounters, and amounts of time spent waiting or travelling for research appointments. These costs can mean that participants, rather than being induced into research, are potentially under compensated for their role in research. Concerns of researchers to minimize this possibility and even to introduce a benefit rather than simply a compensation to participants, can contribute to the payment of inflated or unnecessary fares described in our study. The complexity involved in apparently simple reimbursements has recently been noted for another Kenyan setting [ 32 ]:

" Underneath the seeming obviousness of the concept of ‘reimbursement’ many other considerations were at play and informally negotiated. These included questions of justice and ethics, and personal commitment to provide some help for poor study subjects, but also budgetary constraints, competition with other groups for participants, and concerns with recruitment rates and participant retention [32 ; page 50 ] ’. "