- Privacy Policy

Home » Future Research – Thesis Guide

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Table of Contents

Future Research

Definition:

Future research refers to investigations and studies that are yet to be conducted, and are aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or area of interest. Future research is typically based on the current state of knowledge and seeks to address unanswered questions, gaps in knowledge, and new areas of inquiry.

How to Write Future Research in Thesis

Here are some steps to help you write effectively about future research in your thesis :

- Identify a research gap: Before you start writing about future research, identify the areas that need further investigation. Look for research gaps and inconsistencies in the literature , and note them down.

- Specify research questions : Once you have identified a research gap, create a list of research questions that you would like to explore in future research. These research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to your thesis.

- Discuss limitations: Be sure to discuss any limitations of your research that may require further exploration. This will help to highlight the need for future research and provide a basis for further investigation.

- Suggest methodologies: Provide suggestions for methodologies that could be used to explore the research questions you have identified. Discuss the pros and cons of each methodology and how they would be suitable for your research.

- Explain significance: Explain the significance of the research you have proposed, and how it will contribute to the field. This will help to justify the need for future research and provide a basis for further investigation.

- Provide a timeline : Provide a timeline for the proposed research , indicating when each stage of the research would be conducted. This will help to give a sense of the practicalities involved in conducting the research.

- Conclusion : Summarize the key points you have made about future research and emphasize the importance of exploring the research questions you have identified.

Examples of Future Research in Thesis

SomeExamples of Future Research in Thesis are as follows:

Future Research:

Although this study provides valuable insights into the effects of social media on self-esteem, there are several avenues for future research that could build upon our findings. Firstly, our sample consisted solely of college students, so it would be beneficial to extend this research to other age groups and demographics. Additionally, our study focused only on the impact of social media use on self-esteem, but there are likely other factors that influence how social media affects individuals, such as personality traits and social support. Future research could examine these factors in greater depth. Lastly, while our study looked at the short-term effects of social media use on self-esteem, it would be interesting to explore the long-term effects over time. This could involve conducting longitudinal studies that follow individuals over a period of several years to assess changes in self-esteem and social media use.

While this study provides important insights into the relationship between sleep patterns and academic performance among college students, there are several avenues for future research that could further advance our understanding of this topic.

- This study relied on self-reported sleep patterns, which may be subject to reporting biases. Future research could benefit from using objective measures of sleep, such as actigraphy or polysomnography, to more accurately assess sleep duration and quality.

- This study focused on academic performance as the outcome variable, but there may be other important outcomes to consider, such as mental health or well-being. Future research could explore the relationship between sleep patterns and these other outcomes.

- This study only included college students, and it is unclear if these findings generalize to other populations, such as high school students or working adults. Future research could investigate whether the relationship between sleep patterns and academic performance varies across different populations.

- Fourth, this study did not explore the potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between sleep patterns and academic performance. Future research could investigate the role of factors such as cognitive functioning, motivation, and stress in this relationship.

Overall, there is a need for continued research on the relationship between sleep patterns and academic performance, as this has important implications for the health and well-being of students.

Further research could investigate the long-term effects of mindfulness-based interventions on mental health outcomes among individuals with chronic pain. A longitudinal study could be conducted to examine the sustainability of mindfulness practices in reducing pain-related distress and improving psychological well-being over time. The study could also explore the potential mediating and moderating factors that influence the relationship between mindfulness and mental health outcomes, such as emotional regulation, pain catastrophizing, and social support.

Purpose of Future Research in Thesis

Here are some general purposes of future research that you might consider including in your thesis:

- To address limitations: Your research may have limitations or unanswered questions that could be addressed by future studies. Identify these limitations and suggest potential areas for further research.

- To extend the research : You may have found interesting results in your research, but future studies could help to extend or replicate your findings. Identify these areas where future research could help to build on your work.

- To explore related topics : Your research may have uncovered related topics that were outside the scope of your study. Suggest areas where future research could explore these related topics in more depth.

- To compare different approaches : Your research may have used a particular methodology or approach, but there may be other approaches that could be compared to your approach. Identify these other approaches and suggest areas where future research could compare and contrast them.

- To test hypotheses : Your research may have generated hypotheses that could be tested in future studies. Identify these hypotheses and suggest areas where future research could test them.

- To address practical implications : Your research may have practical implications that could be explored in future studies. Identify these practical implications and suggest areas where future research could investigate how to apply them in practice.

Applications of Future Research

Some examples of applications of future research that you could include in your thesis are:

- Development of new technologies or methods: If your research involves the development of new technologies or methods, you could discuss potential applications of these innovations in future research or practical settings. For example, if you have developed a new drug delivery system, you could speculate about how it might be used in the treatment of other diseases or conditions.

- Extension of your research: If your research only scratches the surface of a particular topic, you could suggest potential avenues for future research that could build upon your findings. For example, if you have studied the effects of a particular drug on a specific population, you could suggest future research that explores the drug’s effects on different populations or in combination with other treatments.

- Investigation of related topics: If your research is part of a larger field or area of inquiry, you could suggest potential research topics that are related to your work. For example, if you have studied the effects of climate change on a particular species, you could suggest future research that explores the impacts of climate change on other species or ecosystems.

- Testing of hypotheses: If your research has generated hypotheses or theories, you could suggest potential experiments or studies that could test these hypotheses in future research. For example, if you have proposed a new theory about the mechanisms of a particular disease, you could suggest experiments that could test this theory in other populations or in different disease contexts.

Advantage of Future Research

Including future research in a thesis has several advantages:

- Demonstrates critical thinking: Including future research shows that the author has thought deeply about the topic and recognizes its limitations. It also demonstrates that the author is interested in advancing the field and is not satisfied with only providing a narrow analysis of the issue at hand.

- Provides a roadmap for future research : Including future research can help guide researchers in the field by suggesting areas that require further investigation. This can help to prevent researchers from repeating the same work and can lead to more efficient use of resources.

- Shows engagement with the field : By including future research, the author demonstrates their engagement with the field and their understanding of ongoing debates and discussions. This can be especially important for students who are just entering the field and want to show their commitment to ongoing research.

- I ncreases the impact of the thesis : Including future research can help to increase the impact of the thesis by highlighting its potential implications for future research and practical applications. This can help to generate interest in the work and attract attention from researchers and practitioners in the field.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Introducing the Future of Work: Key Trends, Concepts, Technologies and Avenues for Future Research

- Open Access

- First Online: 30 July 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Theo Lynn 7 ,

- Pierangelo Rosati 9 ,

- Edel Conway 8 &

- Lisa van der Werff 8

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Digital Business & Enabling Technologies ((PSDBET))

3429 Accesses

The Future of Work is a projection of how work, working, workers and the workplace will evolve in the years ahead from the perspective of different actors in society, influenced by technological, socio-economic, political and demographic changes. In addition to defining the Future of Work, this chapter discusses some of the main trends, themes and concepts in the Future of Work literature before discussing the different topics covered in the remainder of the book. The chapter concludes with a call for greater inter- and multidisciplinary research, evidence to validate assumptions and hypotheses underlying extant Future of Work research and policy, greater use of futures methodologies and a future of research agenda that is even in its coverage of workspaces, population and employment cohorts, regions, sectors, and organisation types.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Changing World of Work in Developing and Emerging Economies

Back to the Future of Work: Old Questions for New Technologies

The Present and Future of Work: Some Concluding Remarks and Reflections on Upcoming Trends

- Future of Work

- Digital technologies

- Digital transformation

- Artificial Intelligence

1.1 Introduction

The Future of Work is not a new idea; however, following the Covid-19 pandemic, it has become not only a major discourse in all aspects of life but a central pillar of government policy worldwide. The pandemic has mainstreamed a plethora of terms (see Table 1.2 ) for how we work in a post-Covid world—hybrid working, remote working and co-working are just some of artefacts that have travelled from the Future of Work to the now of work.

The Future of Work is both a short-term and long-term concern, and while central to industrial strategy, it is by no means limited to this domain. This is particularly evidenced in the European Union where the Future of Work plays a central role in the updated European Industrial Strategy and the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, and is a field of action for the European Research Area and its policy agenda (European Commission, 2022 ). At the time of writing, the European Commission has invested c. €1.9 billion in areas related to the Future of Work, including research and innovation, economic competitiveness and social protection measures (European Commission, 2022 ). It should not be a surprise therefore that the Future of Work is of significant interest to scholars. Despite this interest, it would seem to be something everybody understands but nobody can explain.

This chapter seeks to provide greater clarity on what the Future of Work is or might be. The remainder of the chapter begins with a discussion on the definition of the Future of Work and proposes a working definition for the purposes of this book. This is followed by a brief overview of key trends, themes and concepts on the Future of Work before providing an overview of the topics discussed in the remaining chapters of this book. We conclude with a discussion on some potential future avenues for research and highlight the need for inter- and multidisciplinary research, evidence to validate the many assumptions and hypotheses underlying extant Future of Work research and policy, greater use of futures methodologies and a future of research agenda that is even in its coverage of population and employment cohorts, regions, sectors, workspaces and organisation types.

1.2 What Is the Future of Work?

The term “Future of Work” in itself poses at least three significant challenges for researchers, practitioners and policymakers alike. Firstly, the study of the future requires boundaries. Predicting the future in the social sphere is particularly difficult as there are no strong laws (as in the sciences), and identifying and aggregating relevant information is complicated by its dispersal across different people and organisations (Chen et al., 2003 ). In particular, one needs to be careful not to fall foul of the so-called futures fallacies (Dorr, 2017 ). Thus, any future projection should not:

assume a simple and steady extension of past trends (linear projection fallacy);

consider only one single aspect of change while holding “all else equal” ( ceteris paribus fallacy); and

envision possible futures as static objects rather than as a dynamic process, an ongoing procession of changes (the arrival fallacy) (Dorr, 2017 ).

The second challenge relates to what we mean when we say “work.” A quick review of the literature will reveal that when we talk about the Future of Work it may be related to a particular activity (what), the process of working (how), the worker (who) and the workplace (where), or any combination of these. Thirdly, the Future of Work can be viewed from a variety of perspectives from macro to micro, from a society, industry, firm or an individual level (Stoepfgeshoff, 2018 ).

When dealing with the future, it is always a movable feast. The Future of Work is not new but rather is the latest iteration of an established phenomenon where the current wave of interest is largely driven by the impact of Covid-19 on accelerating technology adoption and new flexible work arrangements. To paraphrase Webster ( 2006 ), there is both change and persistence.

Given its prominence in the public discourse, it is unsurprising that increasingly scholars are arriving at the conclusion that there is no clear understanding about what the Future of Work is (Stoepfgeshoff, 2018 ; Santana & Cobo, 2020 ). The scholarly literature is remarkably scarce on precise definitions of the Future of Work. Instead, the literature on the Future of Work is defined by characteristics or narratives. This is even a feature of reviews of Future of Work research. For example, Balliester and Elsheikhi ( 2018 ) define the Future of Work along five dimensions in which changes brought about by megatrends such as technology, climate change, globalisation and demography impact the world of work, namely (1) the future of jobs; (2) the quality of jobs; (3) wage and income inequality; (4) social protection systems; and (5) social dialogue and industrial relations. Mitchell et al. ( 2022 ) do not define the Future of Work but categorise the most influential research into four key research streams: (1) workplace relations, (2) workplace change, (3) diversity and (4) personal skills. Similarly, in their review, Kolade and Owoseni ( 2022 ) do not define the Future of Work but rather identify three underlying theoretical perspectives from the literature, namely (1) socio-technical systems theory, (2) skill-biased technological change and (3) political economy of automation and digital transformation.

This is not to say that there are no definitions but perhaps one must look elsewhere, for example, to practice. Gartner ( 2022 ) defines the Future of Work as “[…] the changes in how work will get done over the next decade, influenced by technological, generational and social shifts.” The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) defines the Future of Work as “a projection of how work, workers and the workplace will evolve in the years ahead” (SHRM, 2022 ). In the same vein, Deloitte defines the Future of Work as “encompass(ing) changes in work, the workforce, and the workplace” (Schwartz et al., 2019 ). While Gartner ( 2022 ) puts a specific, albeit moving, time horizon of ten years, both Gartner ( 2022 ) and SHRM ( 2022 ) include a consideration of a time still to come unlike Schwartz et al. ( 2019 ). However, while Gartner’s definition focuses exclusively on how work (the what) will be done in the future, the SHRM and Deloitte definitions are wider including how workers (the who) and the workplace (the where) will evolve. Moreover, Gartner recognises that the Future of Work is impacted by the outside world and accommodates these shifts. None of these definitions recognise that the Future of Work may be inflected by the actor perspective. As such, for the purposes of this book, we propose the following definition of the Future of Work which accommodates these existing definitions as well as important dimensions recognised in scholarly literature, namely technological, socio-economic, political and demographic changes (Balliester & Elsheikhi, 2018 ; Anner et al., 2019 ; Santana & Cobo, 2020 ; Mitchell et al., 2022 ):

The Future of Work is a projection of how work, working, workers and the workplace will evolve in the years ahead from the perspective of different actors in society, influenced by technological, socio-economic, political, and demographic changes.

1.3 Key Trends, Themes and Concepts in the Future of Work

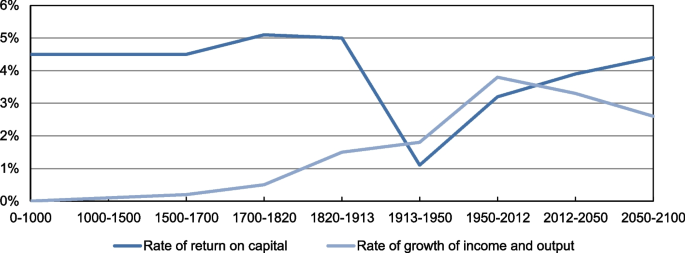

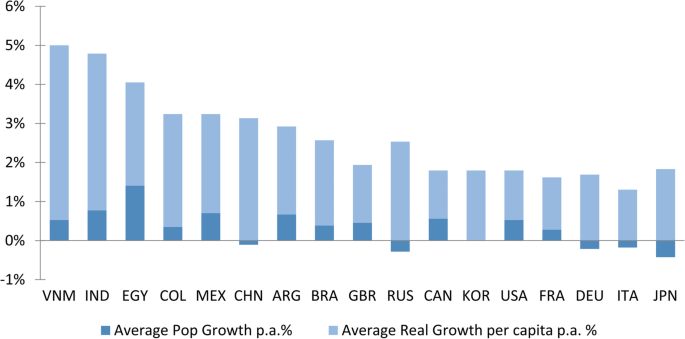

Based on our discussion on the definitions of the Future of Work, it is clear that extant thinking is heavily inflected by a number of predominant trends, themes, concepts and technologies which can be viewed at different levels of granularity. At a high level, technology, climate change, globalisation and demographic changes are common megatrends cited in the literature (Balliester & Elsheikhi, 2018 ). At a more granular level, the focus breaks out into a wide range of trends—the impact of restructuring on efficiency including supply chain optimisation and outsourcing, ageing populations, increased migration and mobility, greater emphasis on work-life balance and wellness, amongst others. More recently, of course, the role and impact of Covid-19, and indeed, future pandemics, has become more prominent and is likely to remain part of the discourse for some time.

In a recent article, Paul Deane ( 2021 ) said: “when thinking about the future, we often overemphasise the role of technology and underestimate where technology fits in a social context.” This has undoubtedly been true in the case of the Future of Work. The predominant theme of literature, from the academy, industry and policymakers, has focussed on the implications of greater digitalisation, automation and analytics on the Future of Work. Unsurprisingly, much of this discourse focuses on advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and associated labour-market and societal effects, although more often than not the distinction between narrow task-focussed AI and more wide-ranging artificial general intelligence (AGI) is ignored.

Academia is neither ignorant of these trends nor deaf to concerns. In their recent review of the 32 most influential publications in the field, Mitchell et al. ( 2022 ) categorise the research into four themes. These are further subdivided into 11 sub-themes—workplace relations (well-being, job insecurity, grievance process, mentoring); workplace changes (evolution of the workplace, telecommuting); diversity (workplace diversity, gender diversity, age discrimination) and personal skills (people skills and storytelling). Echoing Dorr ( 2017 ), it is important to remember that Future of Work research merely provides “snapshots of an inherently dynamic process.” Santana and Cobo ( 2020 ) discuss the thematic evolution of Future of Work research over four periods from 1959 to 2019 based on a systematic mapping of 2286 documents, which is largely consistent with Mitchell et al. ( 2022 ). These are summarised in Table 1.1 . While it is clear that specific perspectives, fears, insights and recommendations are of their age, there are also persistent themes (e.g., telework) and themes that go in and out of vogue (e.g., employment).

In addition to thematically analysing the evolution of Future of Work research, Santana and Cobo ( 2020 ) further categorise themes into four dimensions—technological, social, economic and political/institutional. Technologies such as automation, digitalisation, platformisation and AI are both creating new forms of work (e.g., gig working) and enabling flexible work arrangements (e.g., hybrid, remote and shared working) (Santana & Cobo, 2020 ). Furthermore, AI is introducing new forms of management through algorithmic management, which in turn require new types of skills to train, monitor and optimise such tools. Key terms and concepts in the Future of Work are presented in Table 1.2 .

The transformative effect of technologies, and specifically digital technologies, on how society operates and how social actors interact with each other is well-documented and much-discussed (Martin, 2008 ; Reis et al., 2018 ; Lynn et al., 2022 ). The technological impact on work has a knock-on effect on individuals and citizens. There are real and serious concerns about how new forms of work and working arrangements affect the social dimension of the Future of Work (Santana & Cobo, 2020 ) and social cohesion more generally (Anner et al., 2019 ). While benefitting some parts of society, innovations such as remote working and gig working may exacerbate other social problems and anxieties such as work-life conflict and burnout, as well as other outcomes including career development and progression and job satisfaction (Santana & Cobo, 2020 ). Weil ( 2014 ) has argued that innovations such as the gig economy can result in “fissured workplaces” where the bulk of employees are no longer central to the operation of the company due to outsourcing, franchising, and supply chain optimisation. Furthermore, the adoption of algorithmic management and other analytical techniques for employee surveillance while improving efficiency, performance and productivity may have adverse effects on employee voice and individual autonomy (Anner et al., 2019 ; Figueroa, 2018 ). Weil ( 2014 ), Anner et al. ( 2019 ), ILO ( 2017 ) and others argue that such advancements may, if not checked, result in a decline in wages and working conditions, while increasing levels of precarity and vulnerability experienced by workers. In contrast, Willcocks ( 2020 ), while suggesting that there will be considerable workforce and skill disruption due to technological advancements, suggests that claims on net job loss are exaggerated. Indeed, he argues that not only do extant studies fail to factor in dramatic increases in the amount of work to be done, they also fail to consider ageing populations, productivity gaps and skills shortages. Increasingly, this view is finding increasing support from several leading academics (Bessen et al., 2020 ; Malone et al., 2020 ).

The social and economic dimensions of work are inexplicably linked. When discussing the economic dimension of the Future of Work, the impact is different whether taking the perspective of the economy, sector, the firm or the individual worker. While technological advancements and increased efficiency, performance and productivity have a significant positive impact for economies and firms, the extant Future of Work literature highlights some major risks related to employment, wage inequality and job polarisation (Anner et al., 2019 ). As discussed, the impact of automation, robotics and AI on job numbers and wages is a significant topic of debate. Undoubtedly, some jobs will be replaced and some tasks automated, but equally new jobs and tasks will be created and to some extent AI will augment human capabilities (Bessen, 2018 ; Malone et al., 2020 ). Some commentators highlight some of the serious risks that a more globalised, gig- and remote working future might present to ensuring decent working conditions, minimum standards for workers and social cohesion (Anner et al., 2019 ). For example, Balliester and Elsheikhi ( 2018 ) note that the combination of labour-market changes and technological trends represent at least eight risks to existing working conditions. These include flexibility in hours and location, short-term and casual contracts, longer working hours, low pay and payment uncertainty, reduced occupational safety and health policies, dissolution of workers’ organisation and bargaining power, erosion and absence of legal protection, and informality (Balliester & Elsheikhi, 2018 ).

“The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed,” a quote ascribed to the American science-fiction writer, William Gibson, foreshadows a key aspect of the discourse on the Future of Work and particularly the unevenness of the potential impact of technology on work (see, for example, Bessen, 2018 and Malone et al., 2020 ). Managing the adoption, and associated disruption, of these transformative technologies requires policymakers, political institutions and organisations to develop new organisational forms, policies and regulations to support and incentivise socially responsible adoption and use (Santana & Cobo, 2020 ; Willcocks, 2020 ), but also to retrain and transition workers to new occupations (Bessen, 2018 ; Malone et al., 2020 ; Mindell & Reynolds, 2022 ). This requires a significant multi-stakeholder effort and investment not only to train and upskill the workforce of the future and avoid potential skills inequities but to reduce adverse effects from disruption to longstanding societal norms and expectations. It may require not only a re-imagination of work but education, social protection, regulations and the role of institutions in the design and safeguarding the Future of Work. Given the delicate balance between social and economic policy, and the wide range of stakeholders affected by the Future of Work, governments need to consult and liaise with all stakeholders. This should not be limited to employers and labour organisations but should include the public, community organisations, education providers, data protection authorities and civil liberties advocates as early and transparently as possible so that suitable governance mechanisms are put in place to provide not only input but oversight on Future of Work initiatives.

1.4 Perspectives on the Future of Work

The nine remaining chapters in this book provide perspectives and insights that advance our understanding and help make sense of the Future of Work. They demonstrate that while there has been substantial intellectual effort in the conceptualisation of the Future of Work, we are still at an early stage in theorisation, exploratory and explanatory research, and more importantly actionable outcomes for practice. They are presented as follows.

Chapters 2 and 3 are dedicated to the impact of the increasing adoption of digital technologies in the workplace on employees’ well-being and professions, respectively. More specifically, Chap. 2 focuses on new ways of working (NWW) which are defined as work practices that are enabled by complex information systems and virtualised organisational formations. The authors adopt self-determination theory (SDT) as a lens to explore the impact of NWW on three employees’ universal needs, namely autonomy, competence and relatedness and the actual and potential implications for employees’ well-being. The findings of this review suggest that relatedness is set to play a critical role in supporting the needs for autonomy and competence in increasingly digital workplaces.

Chapter 3 responds to an ongoing and growing debate on how professional roles are impacted and somewhat threatened by technology. This chapter looks at two professions that have been listed by the World Economic Forum ( 2018 ) among the most “at risk,” namely accounting and law, and how they may be impacted by the shift from process and knowledge-oriented activities as a result of the adoption of AI and data analytics. The authors point out that professionals do not always face “standard” situations that can be solved using predetermined rules. On the contrary, most cases require individual professionals to make decisions based on their own judgement; this cannot and should not be replaced by an algorithm. The authors argue that while advancements in digital technologies can supplement and support human judgement, professionals must continue to apply autonomy and reflexive considerations to form independent judgments.

Chapter 4 turns the attention to the so-called gig-economy and related flexible and contingent forms of working that are enabled by digital platforms. More specifically, this chapter delves into how “gig-work” organisations have developed digitally enabled control systems that leverage AI and Machine Learning (ML) to manage their workforce. While the use of algorithmic management provides clear benefits for digital platforms in terms of higher efficiency and lower risks and labour costs, it also creates challenges for management practices, legislators and policymakers, as well as for workers. These challenges are discussed in more detail in the chapter, but they essentially point to the fact that the perceived independence from managerial control that is typical of gig work does not necessarily result in increased autonomy for workers and that closer attention needs to be paid to a number of aspects of gig work, such as the lack of various forms of support, that may detrimental for both gig workers and organisations.

Trust is arguably the cornerstone of any work relationship and the foundation of any social interaction. The increasing use of digital technologies, particularly those systems that leverage advancements in AI and ML, is likely to change the trust dynamics between employees and the organisation. This is the topic of Chap. 5 , which is built on the argument that common practices of advocating the benefits and strengths of new technology are unlikely to be effective in building/protecting employees’ trust as they fall short when it comes to supporting perceptions of organisational character or capability. The authors identify and discuss various challenges posed by the use of smart technology in the workplace (e.g., automation of leadership) and highlight a number of pathways to maximise the benefits of smart technology without undermining organisational trust.

Chapter 6 is dedicated to the role of leadership in the Future of Work. Leadership heavily relies on a leader’s social presence which consists of three dimensions, namely co-presence, behavioural engagement and psychological involvement. While there is an extensive body of research exploring the factors that affect any of these three dimensions, little is known about how leadership dynamics change in a virtual and distributed workplace. The authors present a review of academic literature on leadership and the Future of Work and highlight and discuss four underexplored areas which represent avenues for future research, namely leadership in the context of virtual teams, leader-follower relationships in a digital workplace, the development of human and social capital in the digital world, and leadership in the platform-mediated economy. The authors point out the need for organisations’ leaders to pay closer attention to both the range of digital technologies available and how these can be used to achieve organisational goals.

One of the main consequences of increasing globalisation is the growing diversity of the workforce in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, culture, nationality and language. In addition to this, the use of digital technologies has facilitated the implementation of virtual and distributed teams implying that many organisations no longer have a dominant, traditional or homogenous pool of workers, nor do they have universal structures or approaches to work and working time. This poses both opportunities and challenges for organisations and these are presented and discussed in Chap. 7 . The authors argue that the combination of a more diverse workforce, organisational leaders who are more aware of detrimental discriminatory attitudes and behaviour, and digital technologies that can transform the nature of work provides organisations with a unique opportunity to rethink their definition of success and what roles individual workers can play within the organisation to help organisations succeed.

The adoption of digital technologies not only changes how and where people work but also the skills required to play an active role in the digital economy and how these skills are acquired and developed. Chapters 8 and 9 discuss the learning aspects of the Future of Work. Chapter 8 delves into key skills required for the Future of Work and explores how these skills can be developed and co-created through formal yet flexible higher education and the potential impact this may have on the higher education system. The authors first outline the growing demand and pressure coming from the evolution of work and how this is affecting the higher education system and then highlight the need for universities to move away from a technical focus on skill development to a more holistic view of human-centred development. To conclude, the authors argue that higher education institutions should focus on providing students with innate capabilities and strategic awareness which will help them to identify and ask the right questions, to think critically, to explore silences and inequities, and to seek their own wisdom. In so doing, universities will prepare students for the various “futures of work” that they may be facing rather than a predetermined Future of Work that is based on current fixed disciplinary knowledge and predetermined career trajectories.

Chapter 9 discusses the role of digital technologies in the context of human resource development, specifically their role in learning and development (L&D). In this chapter, the authors highlight how, despite the growing attention received over the last few years and particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, digital learning is still defined in a rather general all-encompassing way in the L&D literature. They provide an overview of L&D technology-based applications that would fall under this definition (e.g., AI, augmented and virtual reality, analytics, learning management systems, etc.) and describe their current use in this field. The authors then discuss how the drive for shorter, faster and less costly training and learning methods may undermine learning quality if digital learning methods are not designed with learning pedagogy in mind and call out the need for further research on synchronous and informal digital learning capabilities and effectiveness before conclusions can be reached concerning the effectiveness of digital learning in the context of human resource development.

Finally, Chap. 10 is dedicated to ethical considerations for the Future of Work. It considers how the adoption of digital technologies generates a new set of ethical questions regarding their contribution to workers’ personal flourishing and to the good of society. In this chapter the authors argue that there is a need for an agent-centred approach to ethics, based on goods, norms and virtues, to analyse the ethical implications of digital technologies on the Future of Work.

1.5 Conclusions and Future Avenues for Research

This chapter introduces some of the challenges with Future of Work research, not least the lack of common definition in the scholarly literature. To address this gap, we define the Future of Work as “a projection of how work, working, workers, and the workplace will evolve in the years ahead from the perspective of different actors in society, influenced by technological, socio-economic, political and demographic changes.” While we summarise the key trends, themes and concepts in the literature, this is largely from a social science perspective. Given that technology, and specifically digitalisation, automation, robotics and AI, is the predominant theme in the Future of Work discourses, we call for more inter- and multidisciplinary collaboration so that a more nuanced discourse on the impact of specific technologies or types of technologies on both jobs and tasks emerges. In particular, with the exception of a relatively small number of authors (see, for example, Malone et al., 2020 and Selenko et al., 2022 ), the differences between narrow AI and artificial general intelligence are under-appreciated and consequently under-researched.

The increased acceptance of new forms of working including remote working, hybrid working and other forms of teleworking during the Covid-19 pandemic has led to a renewed interest in where work is performed and how this may impact the design of workspaces. During the pandemic, work was increasingly performed in spaces beyond the commuting distance to the employer’s work site, typically in their homes. However, there were notable increases in workers not only working remotely in holiday accommodation but also co-working spaces. In some instances, these co-working spaces were other workers’ homes although not necessarily workers of the same employer (Rossitto et al., 2017 ). This so-called hoffice network phenomenon, in itself, may provide significant opportunities for future research. Contemporaneously, there has been a surge in interest in how extended reality (XR) technologies in all its various forms can be applied to work. Technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), telepresence and mirror worlds have the potential to transform how we conceptualise workers and workspaces but also how we train, reskill and transition workers (see, for example, Anderson & Rainie, 2022 ). We encourage researchers to consider how these new technologies and workspaces impact how workers conceptualise where and how they perform work and the implications for workspace design, social interactions, management and organisational forms, amongst others.

Given the size and scope of the book, each chapter provides only a selected snapshot of a given topic. Notwithstanding this, each chapter identifies a potentially rich vein of research to validate or invalidate the hypotheses and arguments made to support a given academic or policy position. This does not mean one should be bound to the arguments of today and the timeline of the future. While there is an increasingly mature set of tools in social sciences for conceptualising the future, these are often not employed in scholarly research on the Future of Work or rather social science research, to echo Bainbridge ( 2003 ), is constrained by methodological rigour or value commitments. Thus, we call for not only greater use of futures methodologies but also research across more specific and longer-term time horizons. For policymakers, in particular, this will enable greater consideration of actionable interventions that can be taken within a more realistic timeframe.

Future of work literature, like much scholarly research, is often led by the more developed countries often focussing on the larger and more advanced commercial entities worldwide. This is particularly the case when discussing technological innovation and disruption. Small and medium-sized enterprises represent approximately 90% of businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide and even higher in rural areas (World Bank, 2021 ). The Future of Work will impact different regions, sectors and organisation types in different ways and at different time scales. Similarly, the changes brought about by the Future of Work will impact different demographics and population cohorts, directly and indirectly, at different times. Successful adoption of new forms of work, workplaces or working arrangements is likely to depend on the worker’s mindset at a given time. Accordingly, we call on researchers to ensure that Future of Work research is equally distributed across population demographics and cohorts, regions, sectors and organisation types.

Earlier in this chapter, we described the Future of Work as a movable feast characterised by persistence and change. For each generation, there is a new generation of Future of Work research, and for each Future of Work scholar, to borrow from Chambers ( 2010 ), a “cornucopia of potentials.”

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16 (2), 40–68.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, J., & Rainie, L. (2022). The Metaverse in 2040 . Pew Research Center.

Google Scholar

Anner, M., Pons-Vignon, N., & Rani, U. (2019). For a future of work with dignity: A critique of the World Bank Development Report, the changing nature of work. Global Labour Journal, 10 (1), 2–19.

Bainbridge, W. S. (2003). The future in the social sciences. Futures, 35 (6), 633–650.

Balliester, T., & Elsheikhi, A. (2018). The future of work: A literature review. ILO Research Department Working Paper, 29 , 1–54.

Bessen, J. (2018). Artificial intelligence and jobs: The role of demand. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda (pp. 291–307). University of Chicago Press.

Bessen, J., Goos, M., Salomons, A., & van den Berge, W. (2020). Automation: A guide for policymakers . Economic Studies at Brookings Institution.

Caza, B. B., Reid, E. M., Ashford, S. J., & Granger, S. (2022). Working on my own: Measuring the challenges of gig work. Human Relations, 75 (11), 2122–2159.

Chambers, R. (2010). Paradigms, poverty and adaptive pluralism. IDS Working Papers, 2010 (344), 1–57.

Chen, K. Y., Fine, L. R., & Huberman, B. A. (2003). Predicting the future. Information Systems Frontiers, 5 (1), 47–61.

Croatti, A., & Ricci, A. (2020). From virtual worlds to mirror worlds: A model and platform for building agent-based extended realities. In Multi-agent systems and agreement technologies (pp. 459–474). Springer.

Deane, P. (2021). Just why is it so hard to predict the future? RTE Brainstorm. https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2019/0715/1062197-just-why-is-it-so-hard-to-predict-the-future/

Department of Defense. (1998). DoD modeling and simulation glossary . United States Department of Defense.

Dionisio, J., Burns, W., III, & Gilbert, R. (2013). 3D virtual worlds and the metaverse: Current status and future possibilities. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 45 (3), 1–38.

Dorr, A. (2017). Common errors in reasoning about the future: Three informal fallacies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 116 , 322–330.

El Naqa, I., & Murphy, M. J. (2015). What is machine learning? In Machine learning in radiation oncology (pp. 3–11). Springer.

European Commission. (2022). The Future of Work. https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/industry/future-work_en

Figueroa, V. (2018). Data and its impacts on workers and citizens. Medium.com , 29 August.

Gartner. (2022). Future of Work . Gartner Human Resource Glossary. https://www.gartner.com/en/human-resources/glossary/future-of-work

Goertzel, B., & Pennachin, C. (2007). Artificial general intelligence (Vol. 2). Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Hoendervanger, J. G., De Been, I., Van Yperen, N. W., Mobach, M. P., & Albers, C. J. (2016). Flexibility in use: Switching behaviour and satisfaction in activity-based work environments. Journal of Corporate Real Estate .

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2017). Inception report for the global commission on the Future of Work.

Kojo, I., & Nenonen, S. (2016). Typologies for co-working spaces in Finland–What and how? Facilities .

Kojo, I., & Nenonen, S. (2017). Evolution of co-working places: drivers and possibilities. Intelligent buildings international, 9 (3), 164–175.

Kolade, O., & Owoseni, A. (2022). Employment 5.0: The work of the future and the Future of Work. Technology in Society, 102086 .

Lee, M. K., Kusbit, D., Metsky, E., & Dabbish, L. (2015, April). Working with machines: The impact of algorithmic and data-driven management on human workers. In Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1603–1612). Association for Computing Machinery.

Lynn, T., Rosati, P., Conway, E., Curran, D., Fox, G., & O’Gorman, C. (2022). Digital towns: Accelerating and measuring the digital transformation of rural societies and economies (p. 213). Springer Nature.

Malone, T. W., Rus, D., & Laubacher, R. (2020). Artificial intelligence and the future of work. A report prepared by MIT Task Force on the work of the future. Research Brief, 17 , 1–39.

Martin, A. (2008). Digital literacy and the “digital society”. Digital Literacies: Concepts, Policies and Practices, 30 (2008), 151–176.

Mateescu, A., & Nguyen, A. (2019). Algorithmic management in the workplace. Data & Society , 1–15.

Milgram, P., & Kishino, F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, 77 (12), 1321–1329.

Mindell, D. A., & Reynolds, E. (2022). The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines . MIT Press.

Mitchell, R., Shen, Y., & Snell, L. (2022). The future of work: A systematic literature review. Accounting and Finance, 62 (2), 2667–2686.

Mohamed, M. (2012). Ergonomics of bridge employment. Work, 41 (Suppl. 1), 307–312.

Oxford English Dictionary. (2022). Algorithm . Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/algorithm

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & Van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet. Policy Review, 8 (4), 1–13.

Reis, J., Amorim, M., Melão, N., & Matos, P. (2018, March). Digital transformation: A literature review and guidelines for future research. In World conference on information systems and technologies (pp. 411–421). Springer.

Rossitto, C., Lampinen, A., & Franzén, C. G. (2017). Hoffice: Social innovation through sustainable nomadic communities. International Reports on Socio-Informatics (IRSI), 14 (3), 49–55.

Santana, M., & Cobo, M. J. (2020). What is the future of work? A science mapping analysis. European Management Journal, 38 (6), 846–862.

Schloerb, D. W. (1995). A quantitative measure of telepresence. Presence Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 4 (1), 64–80.

Schwartz, J., Hatfield, S., Jones, R., & Anderson, S. (2019). What is the future of work? Redefining work, workforces, and workplaces . Deloitte.

Schwellnus, C., Geva, A., & Pak Mathilde, V. R. (2019). Gig economy platforms: Boon or bane? Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Economics Department Working Papers, 1550.

Selenko, E., Bankins, S., Shoss, M., Warburton, J., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2022). Artificial intelligence and the Future of Work: A functional-identity perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31 (3), 272–279.

Sherman, W. R., & Craig, A. B. (2018). Understanding virtual reality: Interface, application, and design . Morgan Kaufmann.

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). (2022). What is meant by “the future of work”? https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/hr-qa/pages/what-is-meant-by-the-future-of-work.aspx

Stephenson, N. (1992). Snow crash . Bantam Books.

Stoepfgeshoff, S. (2018). The Future of Work: Work for the future. ISM Journal of International Business, 2 (2).

UNCTAD. (2021). Technology and innovation report 2021 . United Nations Publications. https://unctad.org/page/technology-and-innovation-report-2021

Webster, F. (2006). Theories of the information society . Routledge.

Weil, D. (2014). The fissured workplace. In The fissured workplace . Harvard University Press.

Willcocks, L. (2020). Robo-Apocalypse cancelled? Reframing the automation and future of work debate. Journal of Information Technology, 35 (4), 286–302.

World Bank. (2021). Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) finance. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

World Economic Forum. (2018). The future of jobs report . World Economic Forum.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Irish Institute of Digital Business, DCU Business School, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

DCU Business School, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Edel Conway & Lisa van der Werff

J.E. Cairnes School of Business and Economics, University of Galway, Galway, Ireland

Pierangelo Rosati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Theo Lynn .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Irish Institute of Digital Business DCU Business School, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

J.E. Cairnes School of Business and EconomicsUniversity of Galway, Galway, Ireland

DCU Business SchoolDublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Edel Conway

Lisa van der Werff

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Lynn, T., Rosati, P., Conway, E., van der Werff, L. (2023). Introducing the Future of Work: Key Trends, Concepts, Technologies and Avenues for Future Research. In: Lynn, T., Rosati, P., Conway, E., van der Werff, L. (eds) The Future of Work. Palgrave Studies in Digital Business & Enabling Technologies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31494-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31494-0_1

Published : 30 July 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31493-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31494-0

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2022

Future of work in 2050: thinking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

- Carlos Eduardo Barbosa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8067-7123 1 , 2 ,

- Yuri Oliveira de Lima 1 ,

- Luis Felipe Coimbra Costa 1 ,

- Herbert Salazar dos Santos 1 ,

- Alan Lyra 1 ,

- Matheus Argôlo 1 ,

- Jonathan Augusto da Silva 1 &

- Jano Moreira de Souza 1

European Journal of Futures Research volume 10 , Article number: 25 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9321 Accesses

8 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Work has been continuously changing throughout history. The most severe changes to work occurred because of the industrial revolutions, and we are living in one of these moments. To allow us to address these changes as early as possible, mitigating important problems before they occur, we need to explore the future of work. As such, our purpose in this paper is to discuss the main global trends and provide a likely scenario for work in 2050 that takes into consideration the recent changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was performed by thirteen researchers with different backgrounds divided into five topics that were analyzed individually using four future studies methods: Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, Futures Wheel, and Scenarios. As the study was done before COVID-19, seven researchers of the original group later updated the most likely scenario with new Bibliometrics and Brainstorming. Our findings include that computerization advances will further reduce the demand for low-skill and low-wage jobs; non-standard employment tends to be better regulated; new technologies will allow a transition to a personalized education process; workers will receive knowledge-intensive training, making them more adaptable to new types of jobs; self-employment and entrepreneurship will grow in the global labor market; and universal basic income would not reach its full potential, but income transfer programs will be implemented for the most vulnerable population. Finally, we highlight that this study explores the future of work in 2050 while considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Work has been continuously changing throughout history. Industrial revolutions represent “profound changes in the means of production,” and they change work in a short period. We had three industrial revolutions: the first was the implementation of factory-based production using steam-powered machines, the second was characterized by changes in production provided by electricity, and the third was triggered by information and computation technologies [ 1 , 2 ].

New technologies and their combined use, such as artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, biotechnology, and nanotechnology, are seen as the starting point of the 4th industrial revolution [ 3 ]. These technologies are intrinsically associated with socioeconomic changes which, combined, will bring new possibilities for the future of work. Hence, the goal of this study is to use a long-term analysis perspective that considers technological development and socioeconomic changes to explore what work will look like in 2050. The future of work is a challenging topic due to its importance ranging from the global economy to social well-being. Therefore, we hope to help decision-makers from companies, governments, and elsewhere to recognize the changes ahead to better guide our society.

The methodology of this study is based on Foresight. We use four methods from future research—namely Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, Futures Wheel, and Scenarios—to present the main global trends that are most relevant for the future of work. These trends were then further analyzed and consolidated in a likely scenario for work in 2050. According to Grupp and Linstone [ 4 ], several countries utilize foresight for policymaking such as EUA, Germany, France, the UK, Spain, Austria, the Republic of Korea [ 5 ], Hungary, South Africa, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan [ 6 ], Canada [ 7 ], India [ 8 ], and Brazil [ 9 ]. Therefore, this study contributes to the understanding of the current situation of work, and its current future trends—the needed knowledge to perform policymaking changes.

In recognition of the tremendous impact of the pandemic on work [ 10 ] and its future, our study was updated with the most recent academic research about the COVID-19 pandemic by new Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, and an update of the Scenarios previously created. However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies [ 11 , 12 ] attempted to understand the dynamics behind the future of work and developed sets of scenarios.

Methodology

This section details the methodology used in this work. First, we present the study dynamics, detailing who participate in the study, how the study was placed in time (number and types of sessions), the foresight methods used, specific goals for each method, and how each method contributed to achieving our main goal, which is to provide scenarios for the future of work in the 2050 horizon. Second, we introduce each method used and explain how they were used in the context of this work.

Foresight studies follow no specific methodology, each study tailor the methodology according to its goals. However, the literature indicates that Foresight becomes more reliable when different and complementary methods are combined [ 13 ], once they provide multiple perspectives for the analysis, reducing the probability of a biased result. Therefore, we used a Foresight framework that generalizes Foresights as workflows [ 14 ] to structure this study.

In this study, we decided to present our results as scenarios, which is a method to develop consistent evolutions of the future based on a set of assumptions [ 15 ] and present the results efficiently to third parties, such as decision-makers. We use the following methods to build the scenarios: Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, and Futures Wheel, respectively. These methods are mostly qualitative; thus, the participants were oriented to base their conclusions on the data gathered in the Bibliometrics method.

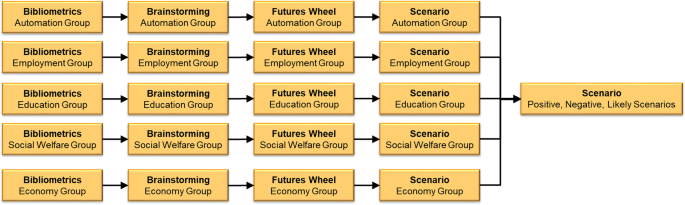

The study dynamic

The study was performed by thirteen researchers (including the moderators) with different backgrounds, for example, in computer engineering, production engineering, public management, architecture and urbanism, and design. These researchers were divided into five groups, taking into consideration their expertise and interests, corresponding to different topics regarding the future of work: computerization/automation (2 researchers), employment (2 researchers), education (3 researchers), social welfare (2 researchers), and economy (2 researchers). The topics were defined by a literature review [ 16 ] that was previously done by researchers of the future of work. The other moderator is an expert in future studies. These two moderators participated in all groups, guiding the participants to follow the methodology and providing suggestions as necessary. It is also worth noting that the moderators presented and discussed the results of each step of the methodology in meetings with all the participants of the study. Furthermore, the guidance provided by the moderators and the participation of, at least, two participants for each topic helped to reduce biases and ensured that even though each topic had a relatively small number of researchers. Methods such as Brainstorming and Futures Wheel were performed as group activities, integrating the entire interdisciplinary group of thirteen people in the collaboration efforts to ensure the quality of the results.

The study was conducted during 8 sessions, once per week. Each session had an approximate duration of 2 hours. Since the duration and format of the sessions were defined before the execution of the study, there were few absences from the participants, and most of them were communicated previously. In absences, the moderators explained the work to be done by e-mail and were available to answer any question. Since most of the work was done in the week between the sessions, each group could perform meetings to produce their contributions. However, the Brainstorming for all groups was performed in a single 5-h session with mandatory attendance.

This study was performed with the aid of software, named Tiamat [ 17 ]. Tiamat software is a modular collaborative Foresight Support System, designed to support on-site and remote (through the Internet) studies using the concept of Foresight method workflow [ 17 ]. The software was used in several studies [ 12 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ] before and allowed the moderators to orchestrate the study, all participants to communicate asynchronously, and serve as a repository that offers traceability to the intermediary results. The Tiamat framework offers a process that can be followed independently from the software; therefore, although we used the computer system to support the study, no special software is required to perform our methodology.

In the first session, the moderators presented the methodology and the Tiamat software and also divided the researchers into the aforementioned five groups. Between the first and the second session, the participants were responsible to search the literature and gather relevant material to be analyzed. The use of bibliometrics is useful to level the knowledge among the interdisciplinary participants, gather and store the state of the art of the topics of the study and select primary citations for further writing future scenarios. Details of the results are presented in the next section.

In the second session, each group presented its findings and the participants had the opportunity to recommend papers to other groups. Each participant would then have two weeks to fully read the papers considered important for their topics.

The third session was focused on discussing their findings until the moment. Each participant would share how the documents that were read up until that session contributed to understanding the future of the topic assigned to their group. Also, the participants were encouraged to share any trends found in the reading that was related to the topic studied by another group, thus stimulating the collaboration between groups.

In the fourth session, the moderators performed five Brainstorming sessions (one for each group) in which the researchers presented the main events they found. For example, the employment group found the event “more flexibility in the employment contract.” In the Brainstorming, we discussed the impacts of each event and proposed new events from the discussion. The Brainstorming ended with voting on which events should be included in the next steps. The moderators lead the brainstorming sessions according to Osborn’s brainstorming guidelines for the generation of ideas [ 22 ]. The participants from the other topics were allowed to participate since many papers that they read also discuss other participants’ topics and their different perspectives may contribute to the topic in discussion. The output of the brainstorming is a list of possible future events regarding the topic of the group. These possible future events were used as input for the next method, Futures Wheel. Between the fourth and fifth sessions, the groups were invited to develop a Futures Wheel [ 23 ], a method that stimulates participants to discover events that are consequences of other events. The Futures Weel also establishes cause-consequence relationships among events which are highlighted in a graph format. We started the Futures Wheel of each group with the events discovered in the brainstorming as initial events , allowing the participants to include, remove, or modify events while they indicate cause-consequence relationships between events, i.e., discovering primary and secondary consequences of events.

In the fifth session, each group presented and discussed their Futures Wheel. At the end of the fifth session, the moderators asked the groups to use the list of expanded events, developed during the Brainstorming and Futures Wheel to identify and develop the main trends for each topic using the scenarios technique and the literature already gathered to support their research—new literature could be added further. We call trend a set of possible future events that told a cohesive matter, heavily supported by the literature—not only the literature gathered in the bibliometrics step. Each group developed trends related to the topic of their study.

In the sixth and seventh sessions, the participants presented the trends for each topic. After the seventh session, the moderators dismissed the topic division, joining all participants to develop 3 scenarios: one which considers the best outcome for each event, one that considers the worst outcome for each event, and one that considers the most likely outcome for each event. The participants were asked to check the consistency of each scenario produced.

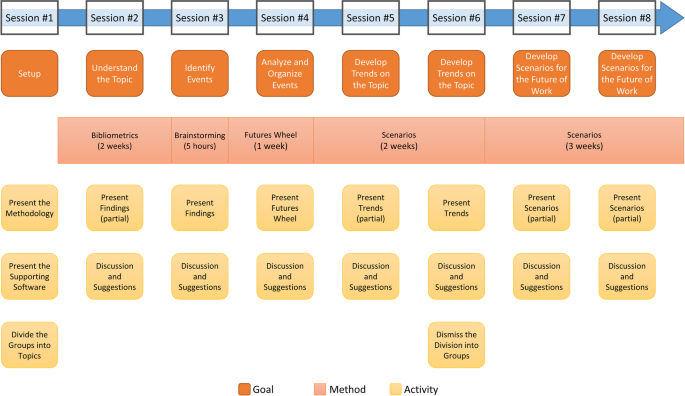

Therefore, the eighth session was focused to check the produced scenarios. The moderators provided one extra week for the participants to fix all spelling and formatting errors and analyze the proposed suggestions from the eighth session. The final version of the scenarios was delivered using the Tiamat software. This study encounters dynamic is presented in Fig. 1 .

Study dynamic diagram

With the COVID-19 pandemic, we knew that our study had to be updated to consider its impact. The update was done in 2 months, from June to August 2020, by gathering seven of the researchers involved in the first part of the study and assigning at least one of them to each of the five topics of the research. The methodologies applied to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the future of work and update the trend scenarios were Bibliometrics and Brainstorming. The Bibliometrics was based on 42 papers about the impact of COVID-19 on the different topics that were being studied with several reports serving as a support to grasp the scenario that was unfolding during the pandemic. Then, the group reviewed the likely scenario to consider how the combination of these individual impacts would change the future of work in 2050. We performed the update without face-to-face sessions, as expected during the COVID restrictions.

The resulting trend scenarios presented in Section 3, and the likely scenario presented in Section 4 already consider the COVID-19 pandemic impact on the future of work.

The methodology in practice

In this section, we formalize the study dynamics: first, we provide a global view of the study, in the form of a workflow; second, we explain how each method work and provide results for methods from one topic as an example of the methodology. The topic of Employment will be used to illustrate the methodology in this section. Since trends and scenarios are the main findings presented in detail in this work, we present in this section only example results from Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, and Futures Wheel.

We highlight that the participants were trained and guided during the study to produce high-quality data and guarantee its uniformity and consistency. In Fig. 2 , we present our methodology in the form of a workflow following the Foresight framework proposed by Barbosa [ 14 ].

Study workflow

The five topics were analyzed individually using four methods: Bibliometrics, Brainstorming, Futures Wheel, and Scenarios.

Bibliometrics

Bibliometric analysis is the analysis of large numbers of scientific documents. Bibliometric analysis is usually taken from patent and scientific publication databases [ 24 ] and should be combined with other measures or expert opinions to be balanced [ 25 ]. The bibliometric analysis summarizes document characteristics for statistical analysis and infers linkage among documents, where it may be used to find indirect links among concepts [ 26 ]. For inferring the linkage among documents, there are a few approaches: co-citation analysis, co-word analysis, and mapping. Co-citation increases the linkage between documents as they cite the same references. Co-word increases the linkage between documents as they use the same relevant words. Mapping presents the bibliometric data and findings, facilitating its interpretation by humans.

In this study context, we used bibliometrics to perform a simple literature review, using both scientific databases and documents available on the Internet, such as governmental reports. Therefore, the researchers gathered data in the literature to build a knowledge base, used to identify trends and support scenarios. Moderators did not enforce the use of systematic reviews of the literature; therefore, we infer the use of random search on several bases and Google to include gray literature. Snowballing was also allowed. We expected to reach beyond the academic literature, including data from technical reports from governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations, think tanks, and companies to capture early signals of change and enrich the study by providing plural views about the future of work. Due to the time restriction between the sessions, we back down from performing a mapping of the literature. The summary of the Bibliometrics results is presented in Table 1 .

As an example of an output of the Bibliometrics method, Table 2 presents the results from the employment group .

Brainstorming

Brainstorming [ 22 ] is a group technique focused on idea generation that frees its participants from criticism [ 27 ]. Osborn’s brainstorming guidelines for the generation of ideas: no immediate concern for quality or evaluation, in a set time frame, encourage building on the ideas of others, and recorded by a non-idea-contributing facilitator/scribe [ 28 ]. Although brainstorming is a very old concept, it is still widely used. Putman and Paulus [ 29 ] proposed a set of rules based on the original Osborn’s rules but extended for interactive groups. Putman and Paulus [ 29 ] proposed rules to avoid criticism, stimulate freewheeling in other participants’ ideas, stimulate quantity over quality of ideas, stimulate the combination and improvement of ideas, avoid losing focus on the task, avoid moments of silence, and stimulate review previously ideas and categories.

In this study context, we used Brainstorming to raise possible future events of each group research topic—computerization/automation, employment, education, social welfare, and economy—on work, based on the literature analyzed in the previous step (Bibliometrics). Moderators place these events are the starting point for the further analysis performed by each research group, following the Putman and Paulus rules. Participants were stimulated to use the literature to develop the events, which were not limited to the Bibliometrics results—i.e, the participants could perform snowballing for example to gather more information. However, the main source of possible future events comes from their understanding of the complex scenario and their further reasoning into ideas. Such ideas—even if they exist—are not easily findable in the literature. Finally, we voted on the list of proposed ideas, developing basic trends to be further analyzed. We present the selected brainstorming events from the Employment group in Table 3 .

Futures wheel

The Futures Wheel [ 23 ] is a method to identify the consequences of trends and events. For the sake of simplicity, we will refer to trends or events only as events. Starting initial events, the participants define a set of primary consequences. The participants should ask themselves three questions to discover the consequences: “If this event occurs, then what happens next?”, “What necessarily goes with this event?”, and “What are the impacts or consequences?”. The Futures Wheel analysis continues recursively, i.e., each primary consequence is analyzed to generate a set of secondary consequences. Although the Futures Wheel may go on indefinitely, rarely does it go further than the tertiary consequences, mostly because the complexity of the analysis grows exponentially. Contradictory consequences may also occur and the participants must consider them.

The participants of the Futures Wheel map the event to its consequences, producing concentric graphs, which highlight the potential complexity of interactions, showing that the consequences do not happen all at once, but in an evolutionary, interactive sequence [ 23 ].

In this study context, we used Futures Wheel to further discussed the events listed in the Brainstorms. Therefore, the Futures Wheel mapped the events to their consequences, producing concentric graphs of primary, secondary, and tertiary consequences. New events were included as a result of this analysis. The Futures Wheel from the Employment group is shown in Fig. 3 .

Futures wheel from the employment group

Scenarios are possible evolutions of the future consistent with some set of assumptions [ 15 ]. Scenarios have been termed the “archetypal product of futures studies” [ 30 ]. They can be achieved through creative thinking about future possibilities (explorative scenarios) as well as through active working towards the production of a desirable future or set of futures (normative scenarios) [ 31 ].

Scenarios represent the combination of a set of extrapolated current trends or projections, and these must be internally consistent, i.e., not contradict each other. For example, when analyzing possible futures related to ATM usage, a scenario where an increase in cashless money transfer and an increase in the usage of ATMs by the general population should be pruned, as these events are mutually exclusive, therefore making the scenario inconsistent [ 32 ]. Indeed, Shoemaker [ 33 ] suggests that three tests of internal consistency are especially useful. Firstly, remove scenarios with trends whose time frames do not match. Secondly, remove scenarios in which predicted outcomes are inconsistent with each other. Lastly, remove scenarios in which major players are placed in unlikely positions.

In this study context, we used scenarios to analyze the events and developed the trend scenarios that are presented in detail in Section 3, using each group Futures Wheel and literature gathered. Therefore, the trend scenarios discuss trends for each topic of this study, and they are heavily based on the literature.

Finally, we also use scenarios to develop three scenarios for work in 2050: an optimistic/positive scenario, a pessimist/negative scenario, and a likely scenario. To develop such scenarios, we dismissed the division of groups into topics, since the scenarios must consider all topics. The Scenarios for work in 2050 were built on all the knowledge gathered in all previous steps. Therefore, the scenarios are based on the joint analysis of the trend scenarios to understand how they interact. We also classify the trends as more or less likely to happen and if a trend can be considered good or bad for society. Due to space limitations, we present the likely scenario in Section 4, which considers the combination of the trends for the future of work that the participants considered as most probable .

Trend scenarios for future work

This section will present the future trends for the areas analyzed in this study: computerization/automation, employment, education, social welfare, and economics.

Computerization/automation

The last century started a transition in industrial automation as machines are increasingly better to make decisions, not only performing manual activities but allowing more activities to be automated. The most cited paper concerning the topic estimated that 47% of the US workforce was under a high probability of computerization (automation by computer technologies, mainly AI and Robotics) in the next decades [ 34 ]. Later studies that applied the same methodology showed that the number of workers in occupations that are likely to suffer computerization varies from country to country. In developing economies such as Brazil, the percentage reaches 60% [ 35 ] while in advanced economies such as the UK, the number drops to 35% [ 36 ].

Areas such as the retail market, archiving, data collection and processing, and line assembly operations will be highly impacted. Still, even for workers at higher risk, adopting automation is not simple: it requires analysis of some key points, such as technical feasibility; development and implementation costs; labor market dynamics, considering its demand, costs, and social characteristics; economic benefits, such as governmental policies; and social acceptance [ 37 ].

As automation increases, it will require policies to protect unprepared and vulnerable workers, allowing them to migrate to the new model of production [ 38 ]. Underdeveloped nations face higher risks since they are rarely part of the discussion about this topic and are outside of the focus of studies. Erroneous interventions also leave underdeveloped nations incapable to compete against developed nations, producing economic, social, and political inequalities along with technological advancement [ 38 ]. It is important to note, however, that unemployment levels have remained stable in the long run, despite disruptions caused by industrial revolutions, as workers migrated to new jobs sometimes enabled by new technologies or the number of jobs was increased because of a higher consumption [ 39 , 40 ].

The increasing adoption of automation technologies results in ever-lower costs of hardware, sensors, network, processing, and storage; a more refined and accurate set of data allowing tests and studies even without human supervision; and a great expansion and absorption of knowledge unprecedented [ 41 ].