Using Science to Inform Educational Practices

Descriptive Research

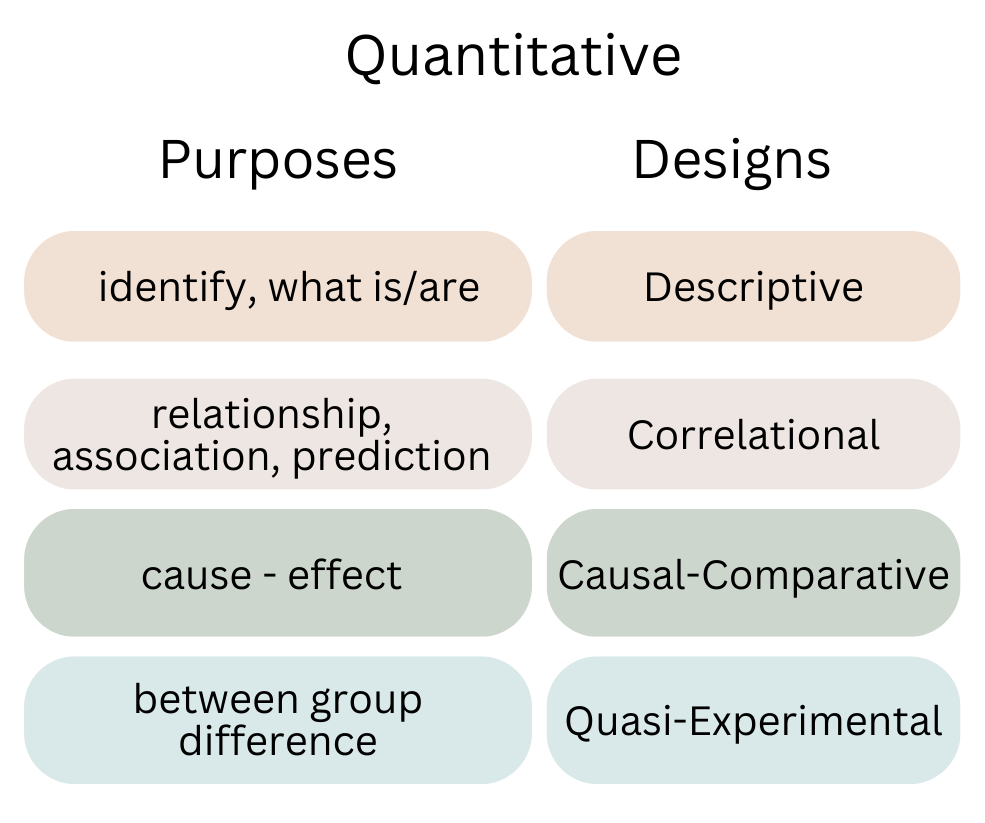

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions to extensive, in-depth interviews—to well-controlled experiments. The main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions.

Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive studies . For this method, the research question or hypothesis can be about a single variable (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?) or can be a broad and exploratory question (e.g., What is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?). The variable of the study is measured and reported without any further relationship analysis. A researcher might choose this method if they only needed to report information, such as a tally, an average, or a list of responses. Descriptive research can answer interesting and important questions, but what it cannot do is answer questions about relationships between variables.

Video 2.4.1. Descriptive Research Design provides explanation and examples for quantitative descriptive research. A closed-captioned version of this video is available here .

Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which researchers formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about causal relationships between variables. We will discuss each of these methods more in-depth later.

Table 2.4.1. Comparison of research design methods

Candela Citations

- Descriptive Research. Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/descriptive-research/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Descriptive Research. Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/adolescent/chapter/descriptive-research/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Educational Psychology Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Educational Research Basics by Del Siegle

Types of Research

How do we know something exists? There are a numbers of ways of knowing…

- -Sensory Experience

- -Agreement with others

- -Expert Opinion

- -Scientific Method (we’re using this one)

The Scientific Process (replicable)

- Identify a problem

- Clarify the problem

- Determine what data would help solve the problem

- Organize the data

- Interpret the results

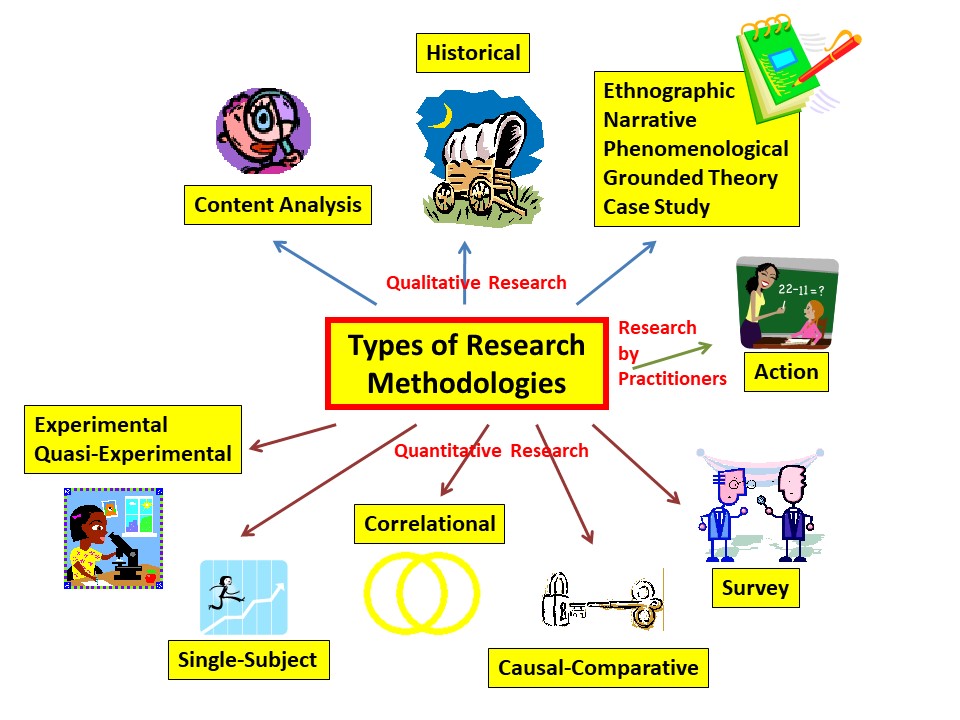

General Types of Educational Research

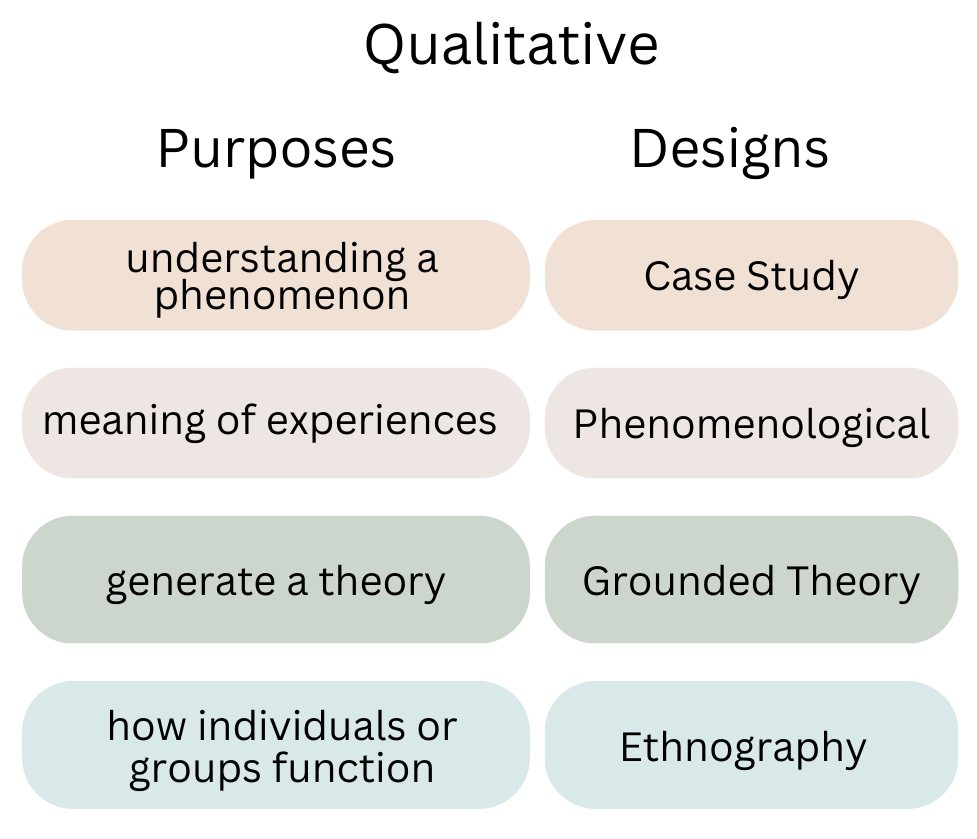

- Descriptive — survey, historical, content analysis, qualitative (ethnographic, narrative, phenomenological, grounded theory, and case study)

- Associational — correlational, causal-comparative

- Intervention — experimental, quasi-experimental, action research (sort of)

Researchers Sometimes Have a Category Called Group Comparison

- Ex Post Facto (Causal-Comparative): GROUPS ARE ALREADY FORMED

- Experimental: RANDOM ASSIGNMENT OF INDIVIDUALS

- Quasi-Experimental: RANDOM ASSIGNMENT OF GROUPS (oversimplified, but fine for now)

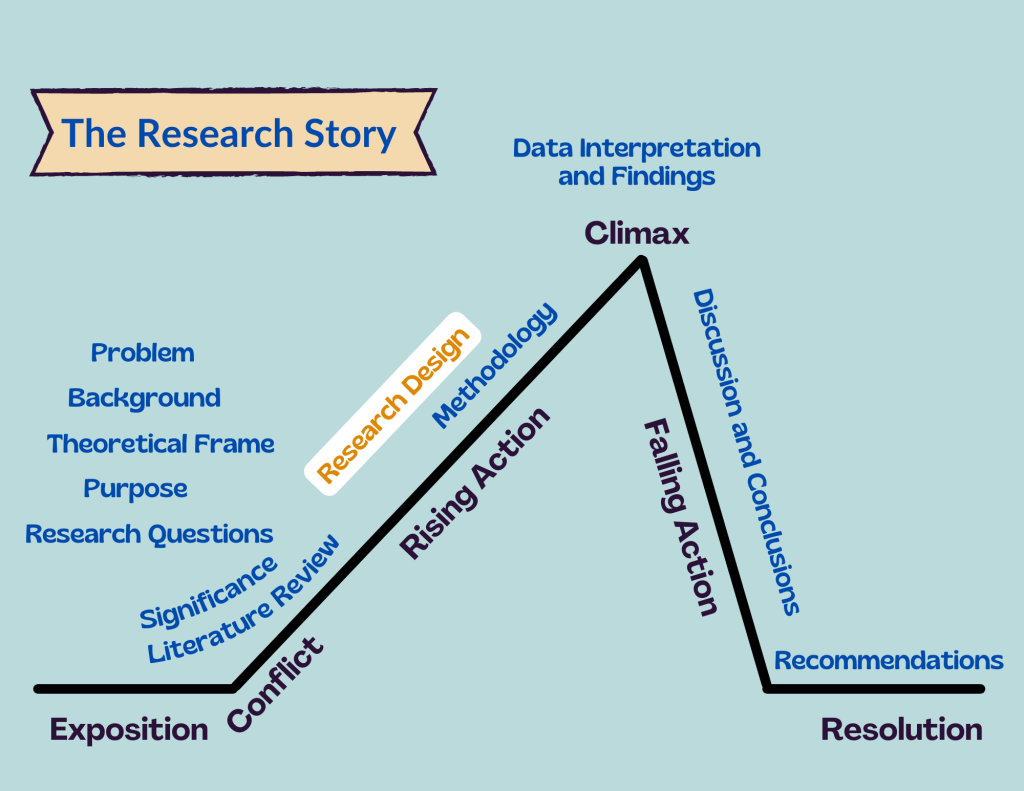

General Format of a Research Publication

- Background of the Problem (ending with a problem statement) — Why is this important to study? What is the problem being investigated?

- Review of Literature — What do we already know about this problem or situation?

- Methodology (participants, instruments, procedures) — How was the study conducted? Who were the participants? What data were collected and how?

- Analysis — What are the results? What did the data indicate?

- Results — What are the implications of these results? How do they agree or disagree with previous research? What do we still need to learn? What are the limitations of this study?

Del Siegle, PhD [email protected]

Last modified 6/18/2019

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when , and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when, and where it happens.

- How has the London housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product Y or product Z?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural, and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analysed for frequencies, averages, and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organisation’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social, and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models, or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event, or organisation). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalisable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/descriptive-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, correlational research | guide, design & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Descriptive Research: Definition, Characteristics, Methods + Examples

Suppose an apparel brand wants to understand the fashion purchasing trends among New York’s buyers, then it must conduct a demographic survey of the specific region, gather population data, and then conduct descriptive research on this demographic segment.

The study will then uncover details on “what is the purchasing pattern of New York buyers,” but will not cover any investigative information about “ why ” the patterns exist. Because for the apparel brand trying to break into this market, understanding the nature of their market is the study’s main goal. Let’s talk about it.

What is descriptive research?

Descriptive research is a research method describing the characteristics of the population or phenomenon studied. This descriptive methodology focuses more on the “what” of the research subject than the “why” of the research subject.

The method primarily focuses on describing the nature of a demographic segment without focusing on “why” a particular phenomenon occurs. In other words, it “describes” the research subject without covering “why” it happens.

Characteristics of descriptive research

The term descriptive research then refers to research questions, the design of the study, and data analysis conducted on that topic. We call it an observational research method because none of the research study variables are influenced in any capacity.

Some distinctive characteristics of descriptive research are:

- Quantitative research: It is a quantitative research method that attempts to collect quantifiable information for statistical analysis of the population sample. It is a popular market research tool that allows us to collect and describe the demographic segment’s nature.

- Uncontrolled variables: In it, none of the variables are influenced in any way. This uses observational methods to conduct the research. Hence, the nature of the variables or their behavior is not in the hands of the researcher.

- Cross-sectional studies: It is generally a cross-sectional study where different sections belonging to the same group are studied.

- The basis for further research: Researchers further research the data collected and analyzed from descriptive research using different research techniques. The data can also help point towards the types of research methods used for the subsequent research.

Applications of descriptive research with examples

A descriptive research method can be used in multiple ways and for various reasons. Before getting into any survey , though, the survey goals and survey design are crucial. Despite following these steps, there is no way to know if one will meet the research outcome. How to use descriptive research? To understand the end objective of research goals, below are some ways organizations currently use descriptive research today:

- Define respondent characteristics: The aim of using close-ended questions is to draw concrete conclusions about the respondents. This could be the need to derive patterns, traits, and behaviors of the respondents. It could also be to understand from a respondent their attitude, or opinion about the phenomenon. For example, understand millennials and the hours per week they spend browsing the internet. All this information helps the organization researching to make informed business decisions.

- Measure data trends: Researchers measure data trends over time with a descriptive research design’s statistical capabilities. Consider if an apparel company researches different demographics like age groups from 24-35 and 36-45 on a new range launch of autumn wear. If one of those groups doesn’t take too well to the new launch, it provides insight into what clothes are like and what is not. The brand drops the clothes and apparel that customers don’t like.

- Conduct comparisons: Organizations also use a descriptive research design to understand how different groups respond to a specific product or service. For example, an apparel brand creates a survey asking general questions that measure the brand’s image. The same study also asks demographic questions like age, income, gender, geographical location, geographic segmentation , etc. This consumer research helps the organization understand what aspects of the brand appeal to the population and what aspects do not. It also helps make product or marketing fixes or even create a new product line to cater to high-growth potential groups.

- Validate existing conditions: Researchers widely use descriptive research to help ascertain the research object’s prevailing conditions and underlying patterns. Due to the non-invasive research method and the use of quantitative observation and some aspects of qualitative observation , researchers observe each variable and conduct an in-depth analysis . Researchers also use it to validate any existing conditions that may be prevalent in a population.

- Conduct research at different times: The analysis can be conducted at different periods to ascertain any similarities or differences. This also allows any number of variables to be evaluated. For verification, studies on prevailing conditions can also be repeated to draw trends.

Advantages of descriptive research

Some of the significant advantages of descriptive research are:

- Data collection: A researcher can conduct descriptive research using specific methods like observational method, case study method, and survey method. Between these three, all primary data collection methods are covered, which provides a lot of information. This can be used for future research or even for developing a hypothesis for your research object.

- Varied: Since the data collected is qualitative and quantitative, it gives a holistic understanding of a research topic. The information is varied, diverse, and thorough.

- Natural environment: Descriptive research allows for the research to be conducted in the respondent’s natural environment, which ensures that high-quality and honest data is collected.

- Quick to perform and cheap: As the sample size is generally large in descriptive research, the data collection is quick to conduct and is inexpensive.

Descriptive research methods

There are three distinctive methods to conduct descriptive research. They are:

Observational method

The observational method is the most effective method to conduct this research, and researchers make use of both quantitative and qualitative observations.

A quantitative observation is the objective collection of data primarily focused on numbers and values. It suggests “associated with, of or depicted in terms of a quantity.” Results of quantitative observation are derived using statistical and numerical analysis methods. It implies observation of any entity associated with a numeric value such as age, shape, weight, volume, scale, etc. For example, the researcher can track if current customers will refer the brand using a simple Net Promoter Score question .

Qualitative observation doesn’t involve measurements or numbers but instead just monitoring characteristics. In this case, the researcher observes the respondents from a distance. Since the respondents are in a comfortable environment, the characteristics observed are natural and effective. In a descriptive research design, the researcher can choose to be either a complete observer, an observer as a participant, a participant as an observer, or a full participant. For example, in a supermarket, a researcher can from afar monitor and track the customers’ selection and purchasing trends. This offers a more in-depth insight into the purchasing experience of the customer.

Case study method

Case studies involve in-depth research and study of individuals or groups. Case studies lead to a hypothesis and widen a further scope of studying a phenomenon. However, case studies should not be used to determine cause and effect as they can’t make accurate predictions because there could be a bias on the researcher’s part. The other reason why case studies are not a reliable way of conducting descriptive research is that there could be an atypical respondent in the survey. Describing them leads to weak generalizations and moving away from external validity.

Survey research

In survey research, respondents answer through surveys or questionnaires or polls . They are a popular market research tool to collect feedback from respondents. A study to gather useful data should have the right survey questions. It should be a balanced mix of open-ended questions and close ended-questions . The survey method can be conducted online or offline, making it the go-to option for descriptive research where the sample size is enormous.

Examples of descriptive research

Some examples of descriptive research are:

- A specialty food group launching a new range of barbecue rubs would like to understand what flavors of rubs are favored by different people. To understand the preferred flavor palette, they conduct this type of research study using various methods like observational methods in supermarkets. By also surveying while collecting in-depth demographic information, offers insights about the preference of different markets. This can also help tailor make the rubs and spreads to various preferred meats in that demographic. Conducting this type of research helps the organization tweak their business model and amplify marketing in core markets.

- Another example of where this research can be used is if a school district wishes to evaluate teachers’ attitudes about using technology in the classroom. By conducting surveys and observing their comfortableness using technology through observational methods, the researcher can gauge what they can help understand if a full-fledged implementation can face an issue. This also helps in understanding if the students are impacted in any way with this change.

Some other research problems and research questions that can lead to descriptive research are:

- Market researchers want to observe the habits of consumers.

- A company wants to evaluate the morale of its staff.

- A school district wants to understand if students will access online lessons rather than textbooks.

- To understand if its wellness questionnaire programs enhance the overall health of the employees.

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

Taking Action in CX – Tuesday CX Thoughts

Apr 30, 2024

QuestionPro CX Product Updates – Quarter 1, 2024

Apr 29, 2024

NPS Survey Platform: Types, Tips, 11 Best Platforms & Tools

Apr 26, 2024

User Journey vs User Flow: Differences and Similarities

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Descriptive Research: Methods And Examples

A research project always begins with selecting a topic. The next step is for researchers to identify the specific areas…

A research project always begins with selecting a topic. The next step is for researchers to identify the specific areas of interest. After that, they tackle the key component of any research problem: how to gather enough quality information. If we opt for a descriptive research design we have to ask the correct questions to access the right information.

For instance, researchers may choose to focus on why people invest in cryptocurrency, knowing how dynamic the market is rather than asking why the market is so shaky. These are completely different questions that require different research approaches. Adopting the descriptive method can help capitalize on trends the information reveals. Descriptive research examples show the thorough research involved in such a study.

Get to know more about descriptive research design .

Descriptive Research Meaning

Features of descriptive research design, types of descriptive research, descriptive research methods, applications of descriptive research, descriptive research examples.

A descriptive method of research is one that describes the characteristics of a phenomenon, situation or population. It uses quantitative and qualitative approaches to describe problems with little relevant information. Descriptive research accurately describes a research problem without asking why a particular event happened. By researching market patterns, the descriptive method answers how patterns change, what caused the change and when the change occurred, instead of dwelling on why the change happened.

Descriptive research refers to questions, study design and analysis of data conducted on a particular topic. It is a strictly observational research methodology with no influence on variables. Some distinctive features of descriptive research are:

- It’s a research method that collects quantifiable information for statistical analysis of a sample. It’s a quantitative market research tool that can analyze the nature of a demographic

- In a descriptive method of research , the nature of research study variables is determined with observation, without influence from the researcher

- Descriptive research is cross-sectional and different sections of a group can be studied

- The analyzed data is collected and serves as information for other search techniques. In this way, a descriptive research design becomes the basis of further research

To understand the descriptive research meaning , data collection methods, examples and application, we need a deeper understanding of its features.

Different ways of approaching the descriptive method help break it down further. Let’s look at the different types of descriptive research :

Descriptive Survey

Descriptive normative survey, descriptive status.

This type of research quantitatively describes real-life situations. For example, to understand the relation between wages and performance, research on employee salaries and their respective performances can be conducted.

Descriptive Analysis

This technique analyzes a subject further. Once the relation between wages and performance has been established, an organization can further analyze employee performance by researching the output of those who work from an office with those who work from home.

Descriptive Classification

Descriptive classification is mainly used in the field of biological science. It helps researchers classify species once they have studied the data collected from different search stations.

Descriptive Comparative

Comparing two variables can show if one is better than the other. Doing this through tests or surveys can reveal all the advantages and disadvantages associated with the two. For example, this technique can be used to find out if paper ballots are better than electronic voting devices.

Correlative Survey

The researcher has to effectively interpret the area of the problem and then decide the appropriate technique of descriptive research design .

A researcher can choose one of the following methods to solve research problems and meet research goals:

Observational Method

With this method, a researcher observes the behaviors, mannerisms and characteristics of the participants. It is widely used in psychology and market research and does not require the participants to be involved directly. It’s an effective method and can be both qualitative and quantitative for the sheer volume and variety of data that is generated.

Survey Research

It’s a popular method of data collection in research. It follows the principle of obtaining information quickly and directly from the main source. The idea is to use rigorous qualitative and quantitative research methods and ask crucial questions essential to the business for the short and long term.

Case Study Method

Case studies tend to fall short in situations where researchers are dealing with highly diverse people or conditions. Surveys and observations are carried out effectively but the time of execution significantly differs between the two.

There are multiple applications of descriptive research design but executives must learn that it’s crucial to clearly define the research goals first. Here’s how organizations use descriptive research to meet their objectives:

- As a tool to analyze participants : It’s important to understand the behaviors, traits and patterns of the participants to draw a conclusion about them. Close-ended questions can reveal their opinions and attitudes. Descriptive research can help understand the participant and assist in making strategic business decisions

- Designed to measure data trends : It’s a statistically capable research design that, over time, allows organizations to measure data trends. A survey can reveal unfavorable scenarios and give an organization the time to fix unprofitable moves

- Scope of comparison: Surveys and research can allow an organization to compare two products across different groups. This can provide a detailed comparison of the products and an opportunity for the organization to capitalize on a large demographic

- Conducting research at any time: An analysis can be conducted at any time and any number of variables can be evaluated. It helps to ascertain differences and similarities

Descriptive research is widely used due to its non-invasive nature. Quantitative observations allow in-depth analysis and a chance to validate any existing condition.

There are several different descriptive research examples that highlight the types, applications and uses of this research method. Let’s look at a few:

- Before launching a new line of gym wear, an organization chose more than one descriptive method to gather vital information. Their objective was to find the kind of gym clothes people like wearing and the ones they would like to see in the market. The organization chose to conduct a survey by recording responses in gyms, sports shops and yoga centers. As a second method, they chose to observe members of different gyms and fitness institutions. They collected volumes of vital data such as color and design preferences and the amount of money they’re willing to spend on it .

- To get a good idea of people’s tastes and expectations, an organization conducted a survey by offering a new flavor of the sauce and recorded people’s responses by gathering data from store owners. This let them understand how people reacted, whether they found the product reasonably priced, whether it served its purpose and their overall general preferences. Based on this, the brand tweaked its core marketing strategies and made the product widely acceptable .

Descriptive research can be used by an organization to understand the spending patterns of customers as well as by a psychologist who has to deal with mentally ill patients. In both these professions, the individuals will require thorough analyses of their subjects and large amounts of crucial data to develop a plan of action.

Every method of descriptive research can provide information that is diverse, thorough and varied. This supports future research and hypotheses. But although they can be quick, cheap and easy to conduct in the participants’ natural environment, descriptive research design can be limited by the kind of information it provides, especially with case studies. Trying to generalize a larger population based on the data gathered from a smaller sample size can be futile. Similarly, a researcher can unknowingly influence the outcome of a research project due to their personal opinions and biases. In any case, a manager has to be prepared to collect important information in substantial quantities and have a balanced approach to prevent influencing the result.

Harappa’s Thinking Critically program harnesses the power of information to strengthen decision-making skills. It’s a growth-driven course for young professionals and managers who want to be focused on their strategies, outperform targets and step up to assume the role of leader in their organizations. It’s for any professional who wants to lay a foundation for a successful career and business owners who’re looking to take their organizations to new heights.

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as Main Objectives of Research , Examples of Experimental Research , Methods Of Ethnographic Research , and How To Use Blended Learning to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

The Art of Sophisticated Quantitative Description in Higher Education Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 23 February 2022

- Cite this reference work entry

- Daniel Klasik 3 &

- William Zahran 3

Part of the book series: Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research ((HATR,volume 37))

1417 Accesses

3 Citations

While the emphasis on causal research in education has become increasingly important in recent years, thoughtful, descriptive analysis remains necessary for providing the conceptual grounding for experimental and quasi-experimental research and understanding our world. Sophisticated quantitative description is an approach to research that does not attempt to determine a causal impact. Instead, its purpose is to critically analyze and present data using purposeful methods to build a theory-driven story about a phenomenon that future research can investigate further. Sophisticated description can offer new ways to look at problems of research and practice, provide context and explanation for causal findings, or open new avenues of research. This chapter defines sophisticated quantitative description and provides an overview of its uses in higher education research. It outlines the numerous goals of sophisticated descriptive research and offers potential methods and approaches for conducting sophisticated description. Exemplars and discussion of published sophisticated descriptive research from the higher education literature are included throughout. The chapter concludes with an application of sophisticated description for analyzing college application behavior in the United States using social network analysis.

Nicholas Hillman was the Associate Editor for this chapter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alvero, A. J., Giebel, S., Gebre-Medhin, B., Antonio, A.L., Stevens, M.L., & Domingue, B.W. (2021). Essay content is strongly related to household income and SAT scores: Evidence from 60,000 undergraduate applications . Science Advances, 7(42), eabi903.

Google Scholar

Arellano, L. (2020). Capitalizing baccalaureate degree attainment: Identifying student and institution level characteristics that ensure success for Latinxs. The Journal of Higher Education, 91 (4), 588–619.

Article Google Scholar

Attewell, P., Lavin, D., Domina, T., & Levey, T. (2006). New evidence on college remediation. The Journal of Higher Education, 77 (5), 886–924.

Avery, C., & Kane, T. (2004). Student perceptions of college opportunities: The Boston COACH program. In C. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 355–391). University of Chicago Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Avery, C., & Turner, S. (2012). Student Loans: Do College Students Borrow Too Much Or Not Enough?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26 (1), 165–92.

Baker, R. (2018). Understanding college students’ major choices using social network analysis. Research in Higher Education, 59 (2), 198–225.

Baker, R., Klasik, D., & Reardon, S. F. (2018). Race and stratification in college enrollment over time. AERA Open, 4 (1), 1–28.

Barringer, S. N., Leahey, E., & Salazar, K. (2020). What catalyzes research universities to commit to interdisciplinary research? Research in Higher Education, 61 (6), 679–705.

Belasco, A. S. (2013). Creating college opportunity: School counselors and their influence on postsecondary enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 54 (7), 781–804.

Bettinger, E. P., & Baker, R. B. (2014). The effects of student coaching: An evaluation of a randomized experiment in student advising. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36 (1), 3–19.

Biancani, S., & McFarland, D. A. (2013). Social networks research in higher education. In M. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, volume 28 (pp. 151–215). Springer.

Bielby, R. M., House, E., Flaster, A., & DesJardins, S. L. (2013). Instrumental variables: Conceptual issues and an application considering high school course taking. In M. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, volume 28 (pp. 263–321). Springer.

Black, D., & Smith, J. (2004). How robust is the evidence on the effects of college quality? Evidence from matching. Journal of Econometrics, 121 , 99.

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources, 8 (4), 436.

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing College at America’s public universities . Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bowman, N. A., Miller, A., Woosley, S., Maxwell, N. P., & Kolze, M. J. (2019). Understanding the link between noncognitive attributes and college retention. Research in Higher Education, 60 (2), 135–152.

Connelly, R., Playford, C. J., Gayle, V., & Dibben, C. (2016). The role of administrative data in the big data revolution in social science research. Social Science Research, 59 , 1–12.

Dale, S., & Krueger, A. B. (2014). Estimating the return to college selectivity over the career using administrative earnings data. Journal of Human Resources, 49 (2), 323-358.

Deming, D. J., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2012). The for-profit postsecondary school sector: Nimble critters or agile predators? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26 (1), 139–164.

Dillon, E. W., & Smith, J. A. (2020). The consequences of academic match between students and colleges. Journal of Human Resources, 55 (3), 767-808.

Douglas, D., & Salzman, H. (2020). Math counts: Major and gender differences in college mathematics coursework. The Journal of Higher Education, 91 (1), 84–112.

Dynarski, S., Libassi, C. J., Michelmore, K., & Owen, S. (2021). Closing the gap: The effect of reducing complexity and uncertainty in college pricing on the choices of low-income students. American Economic Review, 111 (6), 1721–1756.

Flores, S. M., Park, T. J., & Baker, D. J. (2017). The racial college completion gap: Evidence from Texas. The Journal of Higher Education, 88 (6), 894–921.

Furquim, F., Corral, D., & Hillman, N. (2020). A primer for interpreting and designing difference-in-differences studies in higher education research. In L. W. Perna (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, Volume 35 (pp. 1–58). Springer.

Greene, J. A., Oswald, C. A., & Pomerantz, J. (2015). Predictors of retention and achievement in a massive open online course. American Educational Research Journal, 52 (5), 925–955.

Gurantz, O., Howell, J., Hurwitz, M., Larson, C., Pender, M., & White, B. (2020). A national-level informational experiment to promote enrollment in selective colleges. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 42 (2), 453–479.

Hemelt, S. W., Stange, K. M., Furquim, F., Simon, A., & Sawyer, J. E. (2020). Why is math cheaper than English? Understanding cost differences in higher education. Journal of Labor Economics, 39 (2), 397-435.

Hillman, N. W. (2016). Geography of college opportunity: The case of education deserts. American Educational Research Journal, 53 (4), 987–1021.

Ho, A. D., & Reardon, S. F. (2012). Estimating achievement gaps from test scores reported in ordinal “proficiency” categories. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 37 (4), 489–517.

Hoekstra, M. (2009). The effect of attending the flagship state university on earnings: A discontinuity-based approach. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91 (4), 717.

Holzman, B., Klasik, D., & Baker, R. (2020). Gaps in the college application gauntlet. Research in Higher Education, 61 , 795–822.

Hossler, D., Braxton, J. M., & Coopersmith, G. (1989). Understanding student college choices. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 5, pp. 231–288). Agathon Press.

Hossler, D., & Gallagher, K. S. (1987). Studying student college choice: A three-phase model and the implications for policymakers. College and University, 62 (3), 207–221.

Hoxby, C. (2009). The changing selectivity of American colleges. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23 (4), 95–118.

Hoxby, C., & Turner, S. (2013). Expanding college opportunities for high-achieving, low-income students (Stanford Institute for economic policy research discussion paper no. 12-014). Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Hoxby, C. M., & Avery, C. (2013). The missing “one-offs”: The hidden supply of high-achieving, low-income students. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2013(1), 1-65.

Hurwitz, M., Smith, J., Niu, S., & Howell, J. (2015). The Maine question: How is 4-year college enrollment affected by mandatory college entrance exams? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31 (1), 138–159.

Imenda, S. (2014). Is there a conceptual difference between theoretical and conceptual frameworks? Journal of Social Sciences, 38 (2), 185–195.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79 (6), 995–1006.

Klasik, D. (2012). The college application gauntlet: A systematic analysis of the steps to four-year college enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 53 (5), 506–549.

Klasik, D. (2013). The ACT of enrollment: The college enrollment effects of state-required college entrance exam testing. Educational Researcher, 42 (3), 151–160.

Klasik, D., Blagg, K., & Pekor, Z. (2018). Out of the education desert: How limited local college options are associated with inequity in postsecondary opportunities. Social Sciences, 7 (9), 165.

Klasik, D., & Hutt, E. L. (2019). Bobbing for bad apples: Accreditation, quantitative performance measures, and the identification of low-performing colleges. The Journal of Higher Education, 90 (3), 427–461.

Kurban, E. R., & Cabrera, A. F. (2020). Building readiness and intention towards STEM fields of study: Using HSLS:09 and SEM to examine this complex process among high school students. The Journal of Higher Education, 91 (4), 620–650.

Leighton, M., & Speer, J. D. (2020). Labor market returns to college major specificity. European Economic Review, 128 , 103489.

Loeb, S., Dynarski, S., McFarland, D., Morris, P., Reardon, S., & Reber, S. (2017). Descriptive analysis in education: A guide for researchers . National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Long, B. T. (2004). How have college decisions changed over time? An application of the conditional logistic choice model. Journal of Econometrics, 121 (1–2), 271–296.

Long, M. C. (2008). College quality and early adult outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 27 , 588.

McCall, B. P., & Bielby, R. M. (2012). Regression discontinuity design: Recent developments and a guide to practice for researchers in higher education. In J. C. Smart & M. B. Paulsen (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 27, pp. 249–290).

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity . State University of New York Press.

McDonough, P. M. (2005). Counseling matters: Knowledge, assistance, and organizational commitment in college preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach . State University of New York Press.

Miller, G. N. (2020). I’ll know one when I see it: Using social network analysis to define comprehensive institutions through organizational identity. Research in Higher Education, 61 (1), 51–87.

Niu, S. X., & Tienda, M. (2007). Choosing colleges: Identifying and modeling choice sets. Social Science Research, 37 (2), 416–433.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14 (3), 693.

Padgett, J. F., & Ansell, C. K. (1993). Robust action and the rise of the Medici, 1400–1434. American Journal of Sociology, 98 (6), 1259–1319.

Perna, L. W. (2006). Studying college choice: A proposed conceptual model. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 21, pp. 99–157). Springer.

Roderick, M., Coca, V., & Nagaoka, J. (2011). Potholes on the road to college: High school effects in shaping urban students’ participation in college application, four-year college enrollment, and college match. Sociology of Education, 84 (3), 178–211.

Roderick, M., Nagaoka, J., Coca, V., & Moeller, E. (2008). From high school to the future: Potholes on the road to college . Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago.

Rosenboom, V., & Blagg, K. (2018). Disconnected from higher education: How geography and internet speed limit access to higher education . The Urban Institute.

Salazar, K. G., Jaquette, O., & Han, C. (2021). Coming soon to a neighborhood near you? Off-campus recruiting by public research universities. American Educational Research Journal , Online First.

Scott-Clayton, J., & Rodriguez, O. (2015). Development, discouragement, or diversion? New evidence on the effects of college remediation policy. Education Finance and Policy, 10 (1), 4–45.

Skinner, B. T. (2019). Choosing college in the 2000s: An updated analysis using the conditional logistic choice model. Research in Higher Education, 60 (2), 153–183.

Smith, D. A., & White, D. R. (1992). Structure and dynamics of the global economy: Network analysis of international trade 1965–1980. Social Forces, 70 (4), 857–893.

Smith, J. (2018). The sequential college application process. Education Finance and Policy, 13 (4), 545–575.

Smith, J., Pender, M., & Howell, J. (2013). The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. Economics of Education Review, 32 , 247–261.

Turley, R. N. L. (2009). College proximity: Mapping access to opportunity. Sociology of Education, 82 (2), 126–146.

Wang, X. (2016). Course-taking patterns of community college students beginning in STEM: Using data mining techniques to reveal viable STEM transfer pathways. Research in Higher Education, 57 (5), 544–569.

Weiler, W. C. (1994). Transition from consideration of a college to the decision to apply. Research in Higher Education, 35 (6), 1994.

Wells, R. S., Kolek, E. A., Williams, E. A., & Saunders, D. B. (2015). “How we know what we know”: A systematic comparison of research methods employed in higher education journals, 1996–2000 v. 2006–2010. The Journal of Higher Education, 86 (2), 171–198.

Xie, Y., Fang, M., & Shauman, K. (2015). STEM education. Annual Review of Sociology, 41 (1), 331–357.

Xu, D., Jaggars, S. S., Fletcher, J., & Fink, J. E. (2018). Are community college transfer students “a good bet” for 4-year admissions? Comparing academic and labor-market outcomes between transfer and native 4-year college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 89 (4), 478–502.

Zemsky, R., & Oedel, P. (1983). The structure of college choice . College Entrance Examination Board.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The social network analysis of students’ college application choices described in this chapter was supported by a National Academy of Education/Spencer Foundation postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Daniel Klasik & William Zahran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Klasik .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Laura W. Perna

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Klasik, D., Zahran, W. (2022). The Art of Sophisticated Quantitative Description in Higher Education Research. In: Perna, L.W. (eds) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, vol 37. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76660-3_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76660-3_12

Published : 23 February 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-76659-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-76660-3

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Scientific Research in Education (2002)

Chapter: 5 designs for the conduct of scientific research in education, 5 designs for the conduct of scientific research in education.

The salient features of education delineated in Chapter 4 and the guiding principles of scientific research laid out in Chapter 3 set boundaries for the design and conduct of scientific education research. Thus, the design of a study (e.g., randomized experiment, ethnography, multiwave survey) does not itself make it scientific. However, if the design directly addresses a question that can be addressed empirically, is linked to prior research and relevant theory, is competently implemented in context, logically links the findings to interpretation ruling out counterinterpretations, and is made accessible to scientific scrutiny, it could then be considered scientific. That is: Is there a clear set of questions underlying the design? Are the methods appropriate to answer the questions and rule out competing answers? Does the study take previous research into account? Is there a conceptual basis? Are data collected in light of local conditions and analyzed systematically? Is the study clearly described and made available for criticism? The more closely aligned it is with these principles, the higher the quality of the scientific study. And the particular features of education require that the research process be explicitly designed to anticipate the implications of these features and to model and plan accordingly.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Our scientific principles include research design—the subject of this chapter—as but one aspect of a larger process of rigorous inquiry. How-

ever, research design (and corresponding scientific methods) is a crucial aspect of science. It is also the subject of much debate in many fields, including education. In this chapter, we describe some of the most frequently used and trusted designs for scientifically addressing broad classes of research questions in education.

In doing so, we develop three related themes. First, as we posit earlier, a variety of legitimate scientific approaches exist in education research. Therefore, the description of methods discussed in this chapter is illustrative of a range of trusted approaches; it should not be taken as an authoritative list of tools to the exclusion of any others. 1 As we stress in earlier chapters, the history of science has shown that research designs evolve, as do the questions they address, the theories they inform, and the overall state of knowledge.

Second, we extend the argument we make in Chapter 3 that designs and methods must be carefully selected and implemented to best address the question at hand. Some methods are better than others for particular purposes, and scientific inferences are constrained by the type of design employed. Methods that may be appropriate for estimating the effect of an educational intervention, for example, would rarely be appropriate for use in estimating dropout rates. While researchers—in education or any other field—may overstate the conclusions from an inquiry, the strength of scientific inference must be judged in terms of the design used to address the question under investigation. A comprehensive explication of a hierarchy of appropriate designs and analytic approaches under various conditions would require a depth of treatment found in research methods textbooks. This is not our objective. Rather, our goal is to illustrate that among available techniques, certain designs are better suited to address particular kinds of questions under particular conditions than others.

Third, in order to generate a rich source of scientific knowledge in education that is refined and revised over time, different types of inquiries and methods are required. At any time, the types of questions and methods depend in large part on an accurate assessment of the overall state of knowl-

edge and professional judgment about how a particular line of inquiry could advance understanding. In areas with little prior knowledge, for example, research will generally need to involve careful description to formulate initial ideas. In such situations, descriptive studies might be undertaken to help bring education problems or trends into sharper relief or to generate plausible theories about the underlying structure of behavior or learning. If the effects of education programs that have been implemented on a large scale are to be understood, however, investigations must be designed to test a set of causal hypotheses. Thus, while we treat the topic of design in this chapter as applying to individual studies, research design has a broader quality as it relates to lines of inquiry that develop over time.

While a full development of these notions goes considerably beyond our charge, we offer this brief overview to place the discussion of methods that follows into perspective. Also, in the concluding section of this chapter, we make a few targeted suggestions for the kinds of work we believe are most needed in education research to make further progress toward robust knowledge.

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In discussing design, we have to be true to our admonition that the research question drives the design, not vice versa. To simplify matters, the committee recognized that a great number of education research questions fall into three (interrelated) types: description—What is happening? cause—Is there a systematic effect? and process or mechanism—Why or how is it happening?

The first question—What is happening?—invites description of various kinds, so as to properly characterize a population of students, understand the scope and severity of a problem, develop a theory or conjecture, or identify changes over time among different educational indicators—for example, achievement, spending, or teacher qualifications. Description also can include associations among variables, such as the characteristics of schools (e.g., size, location, economic base) that are related to (say) the provision of music and art instruction. The second question is focused on establishing causal effects: Does x cause y ? The search for cause, for example,

can include seeking to understand the effect of teaching strategies on student learning or state policy changes on district resource decisions. The third question confronts the need to understand the mechanism or process by which x causes y . Studies that seek to model how various parts of a complex system—like U.S. education—fit together help explain the conditions that facilitate or impede change in teaching, learning, and schooling. Within each type of question, we separate the discussion into subsections that show the use of different methods given more fine-grained goals and conditions of an inquiry.

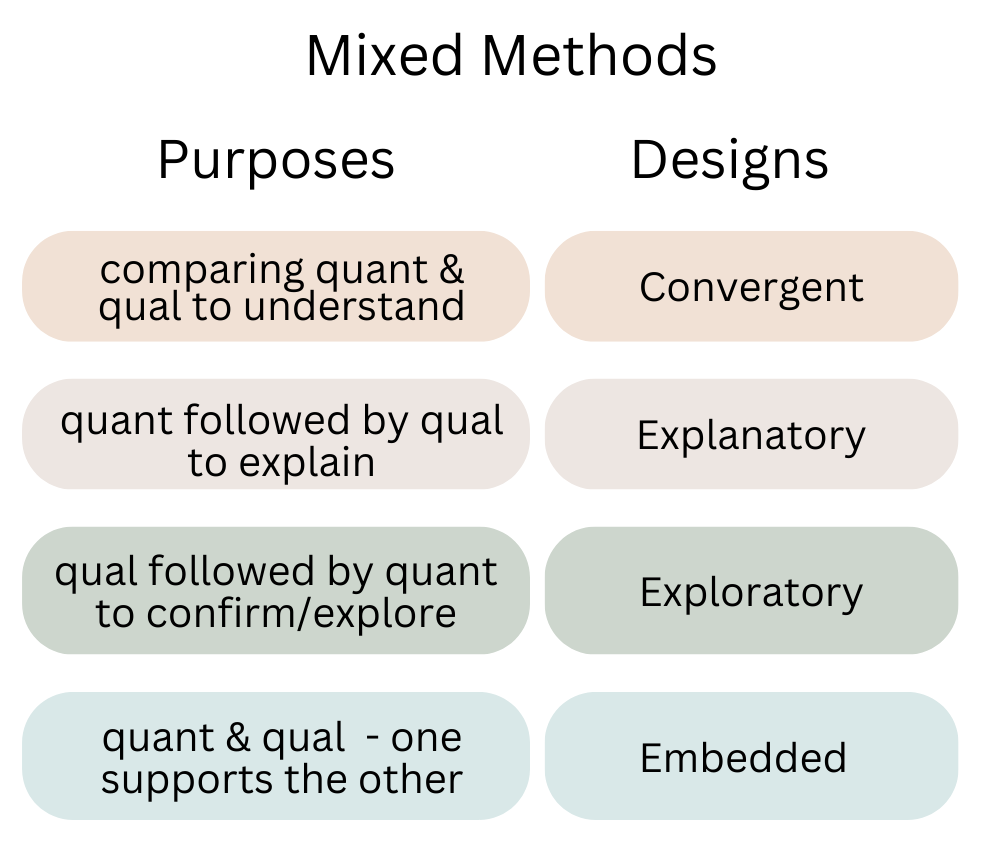

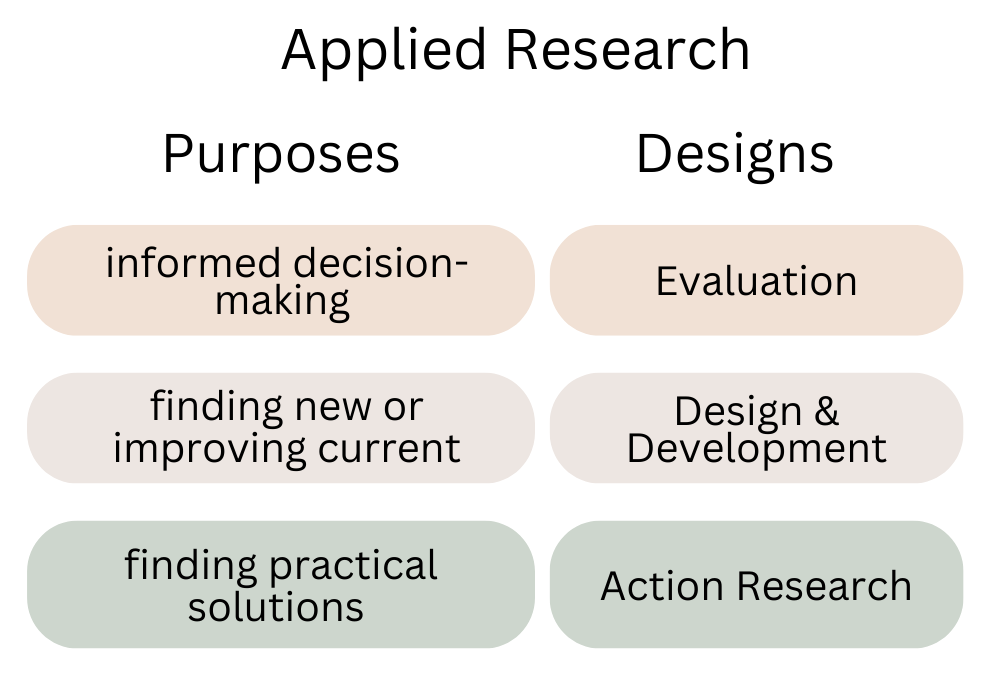

Although for ease of discussion we treat these types of questions separately, in practice they are closely related. As our examples show, within particular studies, several kinds of queries can be addressed. Furthermore, various genres of scientific education research often address more than one of these types of questions. Evaluation research—the rigorous and systematic evaluation of an education program or policy—exemplifies the use of multiple questions and corresponding designs. As applied in education, this type of scientific research is distinguished from other scientific research by its purpose: to contribute to program improvement (Weiss, 1998a). Evaluation often entails an assessment of whether the program caused improvements in the outcome or outcomes of interest (Is there a systematic effect?). It also can involve detailed descriptions of the way the program is implemented in practice and in what contexts ( What is happening? ) and the ways that program services influence outcomes (How is it happening?).

Throughout the discussion, we provide several examples of scientific education research, connecting them to scientific principles ( Chapter 3 ) and the features of education ( Chapter 4 ). We have chosen these studies because they align closely with several of the scientific principles. These examples include studies that generate hypotheses or conjectures as well as those that test them. Both tasks are essential to science, but as a general rule they cannot be accomplished simultaneously.

Moreover, just as we argue that the design of a study does not itself make it scientific, an investigation that seeks to address one of these questions is not necessarily scientific either. For example, many descriptive studies—however useful they may be—bear little resemblance to careful scientific study. They might record observations without any clear conceptual viewpoint, without reproducible protocols for recording data, and so

forth. Again, studies may be considered scientific by assessing the rigor with which they meet scientific principles and are designed to account for the context of the study.

Finally, we have tended to speak of research in terms of a simple dichotomy— scientific or not scientific—but the reality is more complicated. Individual research projects may adhere to each of the principles in varying degrees, and the extent to which they meet these goals goes a long way toward defining the scientific quality of a study. For example, while all scientific studies must pose clear questions that can be investigated empirically and be grounded in existing knowledge, more rigorous studies will begin with more precise statements of the underlying theory driving the inquiry and will generally have a well-specified hypothesis before the data collection and testing phase is begun. Studies that do not start with clear conceptual frameworks and hypotheses may still be scientific, although they are obviously at a more rudimentary level and will generally require follow-on study to contribute significantly to scientific knowledge.

Similarly, lines of research encompassing collections of studies may be more or less productive and useful in advancing knowledge. An area of research that, for example, does not advance beyond the descriptive phase toward more precise scientific investigation of causal effects and mechanisms for a long period of time is clearly not contributing as much to knowledge as one that builds on prior work and moves toward more complete understanding of the causal structure. This is not to say that descriptive work cannot generate important breakthroughs. However, the rate of progress should—as we discuss at the end of this chapter—enter into consideration of the support for advanced lines of inquiry. The three classes of questions we discuss in the remainder of this chapter are ordered in a way that reflects the sequence that research studies tend to follow as well as their interconnected nature.

WHAT IS HAPPENING?

Answers to “What is happening?” questions can be found by following Yogi Berra’s counsel in a systematic way: if you want to know what’s going on, you have to go out and look at what is going on. Such inquiries are descriptive. They are intended to provide a range of information from

documenting trends and issues in a range of geopolitical jurisdictions, populations, and institutions to rich descriptions of the complexities of educational practice in a particular locality, to relationships among such elements as socioeconomic status, teacher qualifications, and achievement.

Estimates of Population Characteristics

Descriptive scientific research in education can make generalizable statements about the national scope of a problem, student achievement levels across the states, or the demographics of children, teachers, or schools. Methods that enable the collection of data from a randomly selected sample of the population provide the best way of addressing such questions. Questionnaires and telephone interviews are common survey instruments developed to gather information from a representative sample of some population of interest. Policy makers at the national, state, and sometimes district levels depend on this method to paint a picture of the educational landscape. Aggregate estimates of the academic achievement level of children at the national level (e.g., National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], National Assessment of Educational Progress [NAEP]), the supply, demand, and turnover of teachers (e.g., NCES Schools and Staffing Survey), the nation’s dropout rates (e.g., NCES Common Core of Data), how U.S. children fare on tests of mathematics and science achievement relative to children in other nations (e.g., Third International Mathematics and Science Study) and the distribution of doctorate degrees across the nation (e.g., National Science Foundation’s Science and Engineering Indicators) are all based on surveys from populations of school children, teachers, and schools.

To yield credible results, such data collection usually depends on a random sample (alternatively called a probability sample) of the target population. If every observation (e.g., person, school) has a known chance of being selected into the study, researchers can make estimates of the larger population of interest based on statistical technology and theory. The validity of inferences about population characteristics based on sample data depends heavily on response rates, that is, the percentage of those randomly selected for whom data are collected. The measures used must have known reliability—that is, the extent to which they reproduce results. Finally, the value of a data collection instrument hinges not only on the

sampling method, participation rate, and reliability, but also on their validity: that the questionnaire or survey items measure what they are supposed to measure.

The NAEP survey tracks national trends in student achievement across several subject domains and collects a range of data on school, student, and teacher characteristics (see Box 5-1 ). This rich source of information enables several kinds of descriptive work. For example, researchers can estimate the average score of eighth graders on the mathematics assessment (i.e., measures of central tendency) and compare that performance to prior years. Part of the study we feature (see below) about college women’s career choices featured a similar estimation of population characteristics. In that study, the researchers developed a survey to collect data from a representative sample of women at the two universities to aid them in assessing the generalizability of their findings from the in-depth studies of the 23 women.

Simple Relationships

The NAEP survey also illustrates how researchers can describe patterns of relationships between variables. For example, NCES reports that in 2000, eighth graders whose teachers majored in mathematics or mathematics education scored higher, on average, than did students whose teachers did not major in these fields (U.S. Department of Education, 2000). This finding is the result of descriptive work that explores the correlation between variables: in this case, the relationship between student mathematics performance and their teachers’ undergraduate major.

Such associations cannot be used to infer cause. However, there is a common tendency to make unsubstantiated jumps from establishing a relationship to concluding cause. As committee member Paul Holland quipped during the committee’s deliberations, “Casual comparisons inevitably invite careless causal conclusions.” To illustrate the problem with drawing causal inferences from simple correlations, we use an example from work that compares Catholic schools to public schools. We feature this study later in the chapter as one that competently examines causal mechanisms. Before addressing questions of mechanism, foundational work involved simple correlational results that compared the performance of Catholic high school students on standardized mathematics tests with their

counterparts in public schools. These simple correlations revealed that average mathematics achievement was considerably higher for Catholic school students than for public school students (Bryk, Lee, and Holland, 1993). However, the researchers were careful not to conclude from this analysis that attending a Catholic school causes better student outcomes, because there are a host of potential explanations (other than attending a Catholic school) for this relationship between school type and achievement. For example, since Catholic schools can screen children for aptitude, they may have a more able student population than public schools at the outset. (This is an example of the classic selectivity bias that commonly threatens the validity of causal claims in nonrandomized studies; we return to this issue in the next section.) In short, there are other hypotheses that could explain the observed differences in achievement between students in different sectors that must be considered systematically in assessing the potential causal relationship between Catholic schooling and student outcomes.

Descriptions of Localized Educational Settings

In some cases, scientists are interested in the fine details (rather than the distribution or central tendency) of what is happening in a particular organization, group of people, or setting. This type of work is especially important when good information about the group or setting is non-existent or scant. In this type of research, then, it is important to obtain first-hand, in-depth information from the particular focal group or site. For such purposes, selecting a random sample from the population of interest may not be the proper method of choice; rather, samples may be purposively selected to illuminate phenomena in depth. 2 For example, to better understand a high-achieving school in an urban setting with children of predominantly low socioeconomic status, a researcher might conduct a detailed case study or an ethnographic study (a case study with a focus on culture) of such a school (Yin and White, 1986; Miles and Huberman,

1994). This type of scientific description can provide rich depictions of the policies, procedures, and contexts in which the school operates and generate plausible hypotheses about what might account for its success. Researchers often spend long periods of time in the setting or group in order to understand what decisions are made, what beliefs and attitudes are formed, what relationships are developed, and what forms of success are celebrated. These descriptions, when used in conjunction with causal methods, are often critical to understand such educational outcomes as student achievement because they illuminate key contextual factors.

Box 5-2 provides an example of a study that described in detail (and also modeled several possible mechanisms; see later discussion) a small group of women, half who began their college careers in science and half in what were considered more traditional majors for women. This descriptive part of the inquiry involved an ethnographic study of the lives of 23 first-year women enrolled in two large universities.

Scientific description of this type can generate systematic observations about the focal group or site, and patterns in results may be generalizable to other similar groups or sites or for the future. As with any other method, a scientifically rigorous case study has to be designed to address the research question it addresses. That is, the investigator has to choose sites, occasions, respondents, and times with a clear research purpose in mind and be sensitive to his or her own expectations and biases (Maxwell, 1996; Silverman, 1993). Data should typically be collected from varied sources, by varied methods, and corroborated by other investigators. Furthermore, the account of the case needs to draw on original evidence and provide enough detail so that the reader can make judgments about the validity of the conclusions (Yin, 2000).

Results may also be used as the basis for new theoretical developments, new experiments, or improved measures on surveys that indicate the extent of generalizability. In the work done by Holland and Eisenhart (1990), for example (see Box 5-2 ), a number of theoretical models were developed and tested to explain how women decide to pursue or abandon nontraditional careers in the fields they had studied in college. Their finding that commitment to college life—not fear of competing with men or other hypotheses that had previously been set forth—best explained these decisions was new knowledge. It has been shown in subsequent studies to

generalize somewhat to similar schools, though additional models seem to exist at some schools (Seymour and Hewitt, 1997).

Although such purposively selected samples may not be scientifically generalizable to other locations or people, these vivid descriptions often appeal to practitioners. Scientifically rigorous case studies have strengths and weaknesses for such use. They can, for example, help local decision makers by providing them with ideas and strategies that have promise in their educational setting. They cannot (unless combined with other methods) provide estimates of the likelihood that an educational approach might work under other conditions or that they have identified the right underlying causes. As we argue throughout this volume, research designs can often be strengthened considerably by using multiple methods— integrating the use of both quantitative estimates of population characteristics and qualitative studies of localized context.

Other descriptive designs may involve interviews with respondents or document reviews in a fairly large number of cases, such as 30 school districts or 60 colleges. Cases are often selected to represent a variety of conditions (e.g., urban/rural; east/west; affluent/poor). Such descriptive studies can be longitudinal, returning to the same cases over several years to see how conditions change.

These examples of descriptive work meet the principles of science, and have clearly contributed important insights to the base of scientific knowledge. If research is to be used to answer questions about “what works,” however, it must advance to other levels of scientific investigation such as those considered next.

IS THERE A SYSTEMATIC EFFECT?

Research designs that attempt to identify systematic effects have at their root an intent to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Causal work is built on both theory and descriptive studies. In other words, the search for causal effects cannot be conducted in a vacuum: ideally, a strong theoretical base as well as extensive descriptive information are in place to provide the intellectual foundation for understanding causal relationships.

The simple question of “does x cause y ?” typically involves several different kinds of studies undertaken sequentially (Holland, 1993). In basic

terms, several conditions must be met to establish cause. Usually, a relationship or correlation between the variables is first identified. 3 Researchers also confirm that x preceded y in time (temporal sequence) and, crucially, that all presently conceivable rival explanations for the observed relationship have been “ruled out.” As alternative explanations are eliminated, confidence increases that it was indeed x that caused y . “Ruling out” competing explanations is a central metaphor in medical research, diagnosis, and other fields, including education, and it is the key element of causal queries (Campbell and Stanley 1963; Cook and Campbell 1979, 1986).

The use of multiple qualitative methods, especially in conjunction with a comparative study of the kind we describe in this section, can be particularly helpful in ruling out alternative explanations for the results observed (Yin, 2000; Weiss, in press). Such investigative tools can enable stronger causal inferences by enhancing the analysis of whether competing explanations can account for patterns in the data (e.g., unreliable measures or contamination of the comparison group). Similarly, qualitative methods can examine possible explanations for observed effects that arise outside of the purview of the study. For example, while an intervention was in progress, another program or policy may have offered participants opportunities similar to, and reinforcing of, those that the intervention provided. Thus, the “effects” that the study observed may have been due to the other program (“history” as the counterinterpretation; see Chapter 3 ). When all plausible rival explanations are identified and various forms of data can be used as evidence to rule them out, the causal claim that the intervention caused the observed effects is strengthened. In education, research that explores students’ and teachers’ in-depth experiences, observes their actions, and documents the constraints that affect their day-to-day activities provides a key source of generating plausible causal hypotheses.

We have organized the remainder of this section into two parts. The first treats randomized field trials, an ideal method when entities being examined can be randomly assigned to groups. Experiments are especially well-suited to situations in which the causal hypothesis is relatively simple. The second describes situations in which randomized field trials are not

feasible or desirable, and showcases a study that employed causal modeling techniques to address a complex causal question. We have distinguished randomized studies from others primarily to signal the difference in the strength with which causal claims can typically be made from them. The key difference between randomized field trials and other methods with respect to making causal claims is the extent to which the assumptions that underlie them are testable. By this simple criterion, nonrandomized studies are weaker in their ability to establish causation than randomized field trials, in large part because the role of other factors in influencing the outcome of interest is more difficult to gauge in nonrandomized studies. Other conditions that affect the choice of method are discussed in the course of the section.

Causal Relationships When Randomization Is Feasible

A fundamental scientific concept in making causal claims—that is, inferring that x caused y —is comparison. Comparing outcomes (e.g., student achievement) between two groups that are similar except for the causal variable (e.g., the educational intervention) helps to isolate the effect of that causal agent on the outcome of interest. 4 As we discuss in Chapter 4 , it is sometimes difficult to retain the sharpness of a comparison in education due to proximity (e.g., a design that features students in one classroom assigned to different interventions is subject to “spillover” effects) or human volition (e.g., teacher, parent, or student decisions to switch to another condition threaten the integrity of the randomly formed groups). Yet, from a scientific perspective, randomized trials (we also use the term “experiment” to refer to causal studies that feature random assignment) are the ideal for establishing whether one or more factors caused change in an outcome because of their strong ability to enable fair comparisons (Campbell and Stanley, 1963; Boruch, 1997; Cook and Payne, in press). Random allocation of students, classrooms, schools—whatever the unit of comparison may be—to different treatment groups assures that these comparison groups are, roughly speaking, equivalent at the time an intervention is introduced (that is, they do not differ systematically on account of hidden

influences) and chance differences between the groups can be taken into account statistically. As a result, the independent effect of the intervention on the outcome of interest can be isolated. In addition, these studies enable legitimate statistical statements of confidence in the results.

The Tennessee STAR experiment (see Chapter 3 ) on class-size reduction is a good example of the use of randomization to assess cause in an education study; in particular, this tool was used to gauge the effectiveness of an intervention. Some policy makers and scientists were unwilling to accept earlier, largely nonexperimental studies on class-size reduction as a basis for major policy decisions in the state. Those studies could not guarantee a fair comparison of children in small versus large classes because the comparisons relied on statistical adjustment rather than on actual construction of statistically equivalent groups. In Tennessee, statistical equivalence was achieved by randomly assigning eligible children and teachers to classrooms of different size. If the trial was properly carried out, 5 this randomization would lead to an unbiased estimate of the relative effect of class-size reduction and a statistical statement of confidence in the results.

Randomized trials are used frequently in the medical sciences and certain areas of the behavioral and social sciences, including prevention studies of mental health disorders (e.g., Beardslee, Wright, Salt, and Drezner, 1997), behavioral approaches to smoking cessation (e.g., Pieterse, Seydel, DeVries, Mudde, and Kok, 2001), and drug abuse prevention (e.g., Cook, Lawrence, Morse, and Roehl, 1984). It would not be ethical to assign individuals randomly to smoke and drink, and thus much of the evidence regarding the harmful effects of nicotine and alcohol comes from descriptive and correlational studies. However, randomized trials that show reductions in health detriments and improved social and behavioral functioning strengthen the causal links that have been established between drug use and adverse health and behavioral outcomes (Moses, 1995; Mosteller, Gilbert, and McPeek, 1980). In medical research, the relative effectiveness of the Salk vaccine (see Lambert and Markel, 2000) and streptomycin (Medical Research Council, 1948) was demonstrated through such trials. We have also learned about which drugs and surgical treatments are useless by depending on randomized controlled experiments (e.g., Schulte et al.,

2001; Gorman et al., 2001; Paradise et al., 1999). Randomized controlled trials are also used in industrial, market, and agricultural research.