14 Crafting a Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Craft a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and declarative.

- Narrow your topic based on your thesis statement and consider the ways that your main points will support the thesis.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

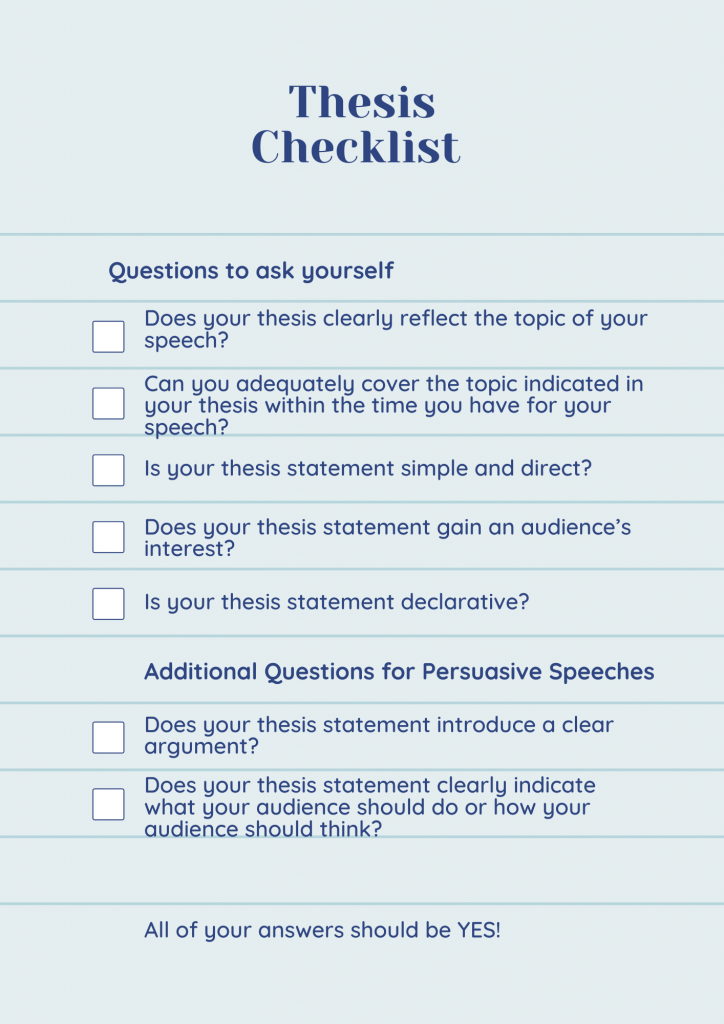

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

Introduction

Attention Getter: Background information: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement.

Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Speech Crafting →

Public Speaking: Developing a Thesis Statement In a Speech

Understanding the purpose of a thesis statement in a speech

Diving headfirst into the world of public speaking, it’s essential to grasp the role of a thesis statement in your speech. Think of it as encapsulating the soul of your speech within one or two sentences.

It’s the declarative sentence that broadcasts your intent and main idea to captivate audiences from start to finish. More than just a preview, an effective thesis statement acts as a roadmap guiding listeners through your thought process.

Giving them that quick glimpse into what they can anticipate helps keep their attention locked in.

As you craft this central hub of information, understand that its purpose is not limited to informing alone—it could be meant also to persuade or entertain based on what you aim for with your general purpose statement.

This clear focus is pivotal—it shapes each aspect of your talk, easing understanding for the audience while setting basic goals for yourself throughout the speech-making journey. So whether you are rallying rapturous applause or instigating intellectual insight, remember—your thesis statement holds power like none other! Its clarity and strength can transition between being valuable sidekicks in introductions towards becoming triumphant heroes by concluding lines.

Identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement

In crafting a compelling speech, identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement acts as your compass. This process is a crucial step in speech preparation that steers you towards specific purpose.

Think of your central idea as the seed from which all other elements in your speech will grow.

To pinpoint it, start by brainstorming broad topics that interest or inspire you. From this list, choose one concept that stands out and begin to narrow it down into more specific points. It’s these refined ideas that form the heart of your thesis statement — essentially acting as signposts leading the audience through your narrative journey.

Crafting an effective thesis statement requires clarity and precision. This means keeping it concise without sacrificing substance—a tricky balancing act even for public speaking veterans! The payoff though? A well-developed thesis statement provides structure to amplifying your central idea and guiding listeners smoothly from point A to B.

It’s worth noting here: just like every speaker has their own unique style, there are multiple ways of structuring a thesis statement too. But no matter how you shape yours, ensuring it resonates with both your overarching message and audience tastes will help cement its effectiveness within your broader presentation context.

Analyzing the audience to tailor the thesis statement

Audience analysis is a crucial first step for every public speaker. This process involves adapting the message to meet the audience’s needs, a thoughtful approach that considers cultural diversity and ensures clear communication.

Adapting your speech to resonate with your target audience’s interests, level of understanding, attitudes and beliefs can significantly affect its impact.

Crafting an appealing thesis statement hinges on this initial stage of audience analysis. As you analyze your crowd, focus on shaping a specific purpose statement that reflects their preferences yet stays true to the objective of your speech—capturing your main idea in one or two impactful sentences.

This balancing act demands strategy; however, it isn’t impossible. Taking into account varying aspects such as culture and perceptions can help you tailor a well-received thesis statement. A strong handle on these elements allows you to select language and tones best suited for them while also reflecting the subject at hand.

Ultimately, putting yourself in their shoes helps increase message clarity which crucially leads to acceptance of both you as the speaker and your key points – all embodied within the concise presentation of your tailor-made thesis statement.

Brainstorming techniques to generate thesis statement ideas

Leveraging brainstorming techniques to generate robust thesis statement ideas is a power move in public speaking. This process taps into the GAP model, focusing on your speech’s Goals, Audience, and Parameters for seamless target alignment.

Dive into fertile fields of thought and let your creativity flow unhindered like expert David Zarefsky proposes.

Start by zeroing in on potential speech topics then nurture them with details till they blossom into fully-fledged arguments. It’s akin to turning stones into gems for the eye of your specific purpose statement.

Don’t shy away from pushing the envelope – sometimes out-of-the-box suggestions give birth to riveting speeches! Broaden your options if parameters are flexible but remember focus is key when aiming at narrow targets.

The beauty lies not just within topic generation but also formulation of captivating informative or persuasive speech thesis statements; both fruits harvested from a successful brainstorming session.

So flex those idea muscles, encourage intellectual growth and watch as vibrant themes spring forth; you’re one step closer to commanding attention!

Remember: Your thesis statement is the heartbeat of your speech – make it strong using brainstorming techniques and fuel its pulse with evidence-backed substance throughout your presentation.

Narrowing down the thesis statement to a specific topic

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your speech requires narrowing down a broad topic to a specific focus that can be effectively covered within the given time frame. This step is crucial as it helps you maintain clarity and coherence throughout your presentation.

Start by brainstorming various ideas related to your speech topic and then analyze them critically to identify the most relevant and interesting points to discuss. Consider the specific purpose of your speech and ask yourself what key message you want to convey to your audience.

By narrowing down your thesis statement, you can ensure that you address the most important aspects of your chosen topic, while keeping it manageable and engaging for both you as the speaker and your audience.

Choosing the appropriate language and tone for the thesis statement

Crafting the appropriate language and tone for your thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a compelling speech. Your choice of language and tone can greatly impact how your audience perceives your message and whether they are engaged or not.

When choosing the language for your thesis statement, it’s important to consider the level of formality required for your speech. Are you speaking in a professional setting or a casual gathering? Adjusting your language accordingly will help you connect with your audience on their level and make them feel comfortable.

Additionally, selecting the right tone is essential to convey the purpose of your speech effectively. Are you aiming to inform, persuade, or entertain? Each objective requires a different tone: informative speeches may call for an objective and neutral tone, persuasive speeches might benefit from more assertive language, while entertaining speeches can be lighthearted and humorous.

Remember that clarity is key when crafting your thesis statement’s language. Using concise and straightforward wording will ensure that your main idea is easily understood by everyone in the audience.

By taking these factors into account – considering formality, adapting to objectives, maintaining clarity – you can create a compelling thesis statement that grabs attention from the start and sets the stage for an impactful speech.

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement is a critical aspect of delivering an effective speech. As public speakers, we understand the importance of backing up our claims with relevant and credible information.

When it comes to incorporating evidence, it’s essential to select facts, examples, and opinions that directly support your thesis statement.

To ensure your evidence is relevant and reliable, consider conducting thorough research on the topic at hand. Look for trustworthy sources such as academic journals, respected publications, or experts in the field.

By choosing solid evidence that aligns with your message, you can enhance your credibility as a speaker.

When presenting your evidence in the speech itself, be sure to keep it concise and clear. Avoid overwhelming your audience with excessive details or data. Instead, focus on selecting key points that strengthen your argument while keeping their attention engaged.

Remember that different types of evidence can be utilized depending on the nature of your speech. You may include statistical data for a persuasive presentation or personal anecdotes for an informative talk.

The choice should reflect what will resonate best with your audience and effectively support your thesis statement.

By incorporating strong evidence into our speeches, we not only bolster our arguments but also build trust with our listeners who recognize us as reliable sources of information. So remember to choose wisely when including supporting material – credibility always matters when making an impact through public speaking.

Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement

Crafting an effective thesis statement is vital for public speakers to deliver a compelling and focused speech. To avoid common mistakes when developing a thesis statement , it is essential to be aware of some pitfalls that can hinder the impact of your message.

One mistake to steer clear of is having an incomplete thesis statement. Ensure that your thesis statement includes all the necessary information without leaving any key elements out. Additionally, avoid wording your thesis statement as a question as this can dilute its potency.

Another mistake to watch out for is making statements of fact without providing evidence or support. While it may seem easy to write about factual information, it’s important to remember that statements need to be proven and backed up with credible sources or examples.

To create a more persuasive argument, avoid using phrases like “I believe” or “I feel.” Instead, take a strong stance in your thesis statement that encourages support from the audience. This will enhance your credibility and make your message more impactful.

By avoiding these common mistakes when crafting your thesis statement, you can develop a clear, engaging, and purposeful one that captivates your audience’s attention and guides the direction of your speech effectively.

Key words: Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement – Crafting a thesis statement – Effective thesis statements – Public speaking skills – Errors in the thesis statement – Enhancing credibility

Revising the thesis statement to enhance clarity and coherence

Revising the thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a clear and coherent speech. The thesis statement serves as the main idea or argument that guides your entire speech, so it’s important to make sure it effectively communicates your message to the audience.

To enhance clarity and coherence in your thesis statement, start by refining and strengthening it through revision . Take into account any feedback you may have received from others or any new information you’ve gathered since initially developing the statement.

Consider if there are any additional points or evidence that could further support your main idea.

As you revise, focus on clarifying the language and tone of your thesis statement. Choose words that resonate with your audience and clearly convey your point of view. Avoid using technical jargon or overly complicated language that might confuse or alienate listeners.

Another important aspect of revising is ensuring that your thesis statement remains focused on a specific topic. Narrow down broad ideas into more manageable topics that can be explored thoroughly within the scope of your speech.

Lastly, consider incorporating evidence to support your thesis statement. This could include statistics, examples, expert opinions, or personal anecdotes – whatever helps strengthen and validate your main argument.

By carefully revising your thesis statement for clarity and coherence, you’ll ensure that it effectively conveys your message while capturing the attention and understanding of your audience at large.

Testing the thesis statement to ensure it meets the speech’s objectives.

Testing the thesis statement is a crucial step to ensure that it effectively meets the objectives of your speech. By testing the thesis statement , you can assess its clarity, relevance, and impact on your audience.

One way to test your thesis statement is to consider its purpose and intent. Does it clearly communicate what you want to achieve with your speech? Is it concise and specific enough to guide your content?.

Another important aspect of testing the thesis statement is analyzing whether it aligns with the needs and interests of your audience. Consider their background knowledge, values, and expectations.

Will they find the topic engaging? Does the thesis statement address their concerns or provide valuable insights?.

In addition to considering purpose and audience fit, incorporating supporting evidence into your speech is vital for testing the effectiveness of your thesis statement. Ensure that there is relevant material available that supports your claim.

To further enhance clarity and coherence in a tested thesis statement, revise it if necessary based on feedback from others or through self-reflection. This will help refine both language choices and overall effectiveness.

By thoroughly testing your thesis statement throughout these steps, you can confidently develop a clear message for an impactful speech that resonates with your audience’s needs while meeting all stated objectives.

1. What is a thesis statement in public speaking?

A thesis statement in public speaking is a concise and clear sentence that summarizes the main point or argument of a speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience, guiding them through the speech and helping them understand its purpose.

2. How do I develop an effective thesis statement for a speech?

To develop an effective thesis statement for a speech, start by identifying your topic and determining what specific message you want to convey to your audience. Then, clearly state this message in one or two sentences that capture the main idea of your speech.

3. Why is it important to have a strong thesis statement in public speaking?

Having a strong thesis statement in public speaking helps you stay focused on your main argument throughout the speech and ensures that your audience understands what you are trying to communicate. It also helps establish credibility and authority as you present well-supported points related to your thesis.

4. Can my thesis statement change during my speech preparation?

Yes, it is possible for your thesis statement to evolve or change during the preparation process as you gather more information or refine your ideas. However, it’s important to ensure that any changes align with the overall purpose of your speech and still effectively guide the content and structure of your presentation.

Speechwriting

8 Purpose and Thesis

Speechwriting Essentials

In this chapter . . .

As discussed in the chapter on Speaking Occasion , speechwriting begins with careful analysis of the speech occasion and its given circumstances, leading to the choice of an appropriate topic. As with essay writing, the early work of speechwriting follows familiar steps: brainstorming, research, pre-writing, thesis, and so on.

This chapter focuses on techniques that are unique to speechwriting. As a spoken form, speeches must be clear about the purpose and main idea or “takeaway.” Planned redundancy means that you will be repeating these elements several times over during the speech.

Furthermore, finding purpose and thesis are essential whether you’re preparing an outline for extemporaneous delivery or a completely written manuscript for presentation. When you know your topic, your general and specific purpose, and your thesis or central idea, you have all the elements you need to write a speech that is focused, clear, and audience friendly.

Recognizing the General Purpose

Speeches have traditionally been grouped into one of three categories according to their primary purpose: 1) to inform, 2) to persuade, or 3) to inspire, honor, or entertain. These broad goals are commonly known as the general purpose of a speech . Earlier, you learned about the actor’s tool of intention or objectives. The general purpose is like a super-objective; it defines the broadest goal of a speech. These three purposes are not necessarily exclusive to the others. A speech designed to be persuasive can also be informative and entertaining. However, a speech should have one primary goal. That is its general purpose.

Why is it helpful to talk about speeches in such broad terms? Being perfectly clear about what you want your speech to do or make happen for your audience will keep you focused. You can make a clearer distinction between whether you want your audience to leave your speech knowing more (to inform), or ready to take action (to persuade), or feeling something (to inspire)

It’s okay to use synonyms for these broad categories. Here are some of them:

- To inform could be to explain, to demonstrate, to describe, to teach.

- To persuade could be to convince, to argue, to motivate, to prove.

- To inspire might be to honor, or entertain, to celebrate, to mourn.

In summary, the first question you must ask yourself when starting to prepare a speech is, “Is the primary purpose of my speech to inform, to persuade, or to inspire?”

Articulating Specific Purpose

A specific purpose statement builds upon your general purpose and makes it specific (as the name suggests). For example, if you have been invited to give a speech about how to do something, your general purpose is “to inform.” Choosing a topic appropriate to that general purpose, you decide to speak about how to protect a personal from cyberattacks. Now you are on your way to identifying a specific purpose.

A good specific purpose statement has three elements: goal, target audience, and content.

If you think about the above as a kind of recipe, then the first two “ingredients” — your goal and your audience — should be simple. Words describing the target audience should be as specific as possible. Instead of “my peers,” you could say, for example, “students in their senior year at my university.”

The third ingredient in this recipe is content, or what we call the topic of your speech. This is where things get a bit difficult. You want your content to be specific and something that you can express succinctly in a sentence. Here are some common problems that speakers make in defining the content, and the fix:

Now you know the “recipe” for a specific purpose statement. It’s made up of T o, plus an active W ord, a specific A udience, and clearly stated C ontent. Remember this formula: T + W + A + C.

A: for a group of new students

C: the term “plagiarism”

Here are some further examples a good specific purpose statement:

- To explain to a group of first-year students how to join a school organization.

- To persuade the members of the Greek society to take a spring break trip in Daytona Beach.

- To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program.

- To convince first-year students that they need at least seven hours of sleep per night to do well in their studies.

- To inspire my Church community about the accomplishments of our pastor.

The General and Specific Purpose Statements are writing tools in the sense that they help you, as a speechwriter, clarify your ideas.

Creating a Thesis Statement

Once you are clear about your general purpose and specific purpose, you can turn your attention to crafting a thesis statement. A thesis is the central idea in an essay or a speech. In speechwriting, the thesis or central idea explains the message of the content. It’s the speech’s “takeaway.” A good thesis statement will also reveal and clarify the ideas or assertions you’ll be addressing in your speech (your main points). Consider this example:

General Purpose: To persuade. Specific Purpose: To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program. Thesis: A semester-long study abroad experience produces lifelong benefits by teaching you about another culture, developing your language skills, and enhancing your future career prospects.

The difference between a specific purpose statement and a thesis statement is clear in this example. The thesis provides the takeaway (the lifelong benefits of study abroad). It also points to the assertions that will be addressed in the speech. Like the specific purpose statement, the thesis statement is a writing tool. You’ll incorporate it into your speech, usually as part of the introduction and conclusion.

All good expository, rhetorical, and even narrative writing contains a thesis. Many students and even experienced writers struggle with formulating a thesis. We struggle when we attempt to “come up with something” before doing the necessary research and reflection. A thesis only becomes clear through the thinking and writing process. As you develop your speech content, keep asking yourself: What is important here? If the audience can remember only one thing about this topic, what do I want them to remember?

Example #2: General Purpose: To inform Specific Purpose: To demonstrate to my audience the correct method for cleaning a computer keyboard. Central Idea: Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Example # 3 General Purpose: To Inform Specific Purpose: To describe how makeup is done for the TV show The Walking Dead . Central Idea: The wildly popular zombie show The Walking Dead achieves incredibly scary and believable makeup effects, and in the next few minutes I will tell you who does it, what they use, and how they do it.

Notice in the examples above that neither the specific purpose nor the central idea ever exceeds one sentence. If your central idea consists of more than one sentence, then you are probably including too much information.

Problems to Avoid

The first problem many students have in writing their specific purpose statement has already been mentioned: specific purpose statements sometimes try to cover far too much and are too broad. For example:

“To explain to my classmates the history of ballet.”

Aside from the fact that this subject may be difficult for everyone in your audience to relate to, it’s enough for a three-hour lecture, maybe even a whole course. You’ll probably find that your first attempt at a specific purpose statement will need refining. These examples are much more specific and much more manageable given the limited amount of time you’ll have.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet came to be performed and studied in the U.S.

- To explain to my classmates the difference between Russian and French ballet.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet originated as an art form in the Renaissance.

- To explain to my classmates the origin of the ballet dancers’ clothing.

The second problem happens when the “communication verb” in the specific purpose does not match the content; for example, persuasive content is paired with “to inform” or “to explain.” Can you find the errors in the following purpose statements?

- To inform my audience why capital punishment is unconstitutional. (This is persuasive. It can’t be informative since it’s taking a side)

- To persuade my audience about the three types of individual retirement accounts. (Even though the purpose statement says “persuade,” it isn’t persuading the audience of anything. It is informative.)

- To inform my classmates that Universal Studios is a better theme park than Six Flags over Georgia. (This is clearly an opinion; hence it is a persuasive speech and not merely informative)

The third problem exists when the content part of the specific purpose statement has two parts. One specific purpose is enough. These examples cover two different topics.

- To explain to my audience how to swing a golf club and choose the best golf shoes.

- To persuade my classmates to be involved in the Special Olympics and vote to fund better classes for the intellectually disabled.

To fix this problem of combined or hybrid purposes, you’ll need to select one of the topics in these examples and speak on that one alone.

The fourth problem with both specific purpose and central idea statements is related to formatting. There are some general guidelines that need to be followed in terms of how you write out these elements of your speech:

- Don’t write either statement as a question.

- Always use complete sentences for central idea statements and infinitive phrases (beginning with “to”) for the specific purpose statement.

- Use concrete language (“I admire Beyoncé for being a talented performer and businesswoman”) and avoid subjective or slang terms (“My speech is about why I think Beyoncé is the bomb”) or jargon and acronyms (“PLA is better than CBE for adult learners.”)

There are also problems to avoid in writing the central idea statement. As mentioned above, remember that:

- The specific purpose and central idea statements are not the same thing, although they are related.

- The central idea statement should be clear and not complicated or wordy; it should “stand out” to the audience. As you practice delivery, you should emphasize it with your voice.

- The central idea statement should not be the first thing you say but should follow the steps of a good introduction as outlined in the next chapters.

You should be aware that all aspects of your speech are constantly going to change as you move toward the moment of giving your speech. The exact wording of your central idea may change, and you can experiment with different versions for effectiveness. However, your specific purpose statement should not change unless there is a good reason to do so. There are many aspects to consider in the seemingly simple task of writing a specific purpose statement and its companion, the central idea statement. Writing good ones at the beginning will save you some trouble later in the speech preparation process.

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

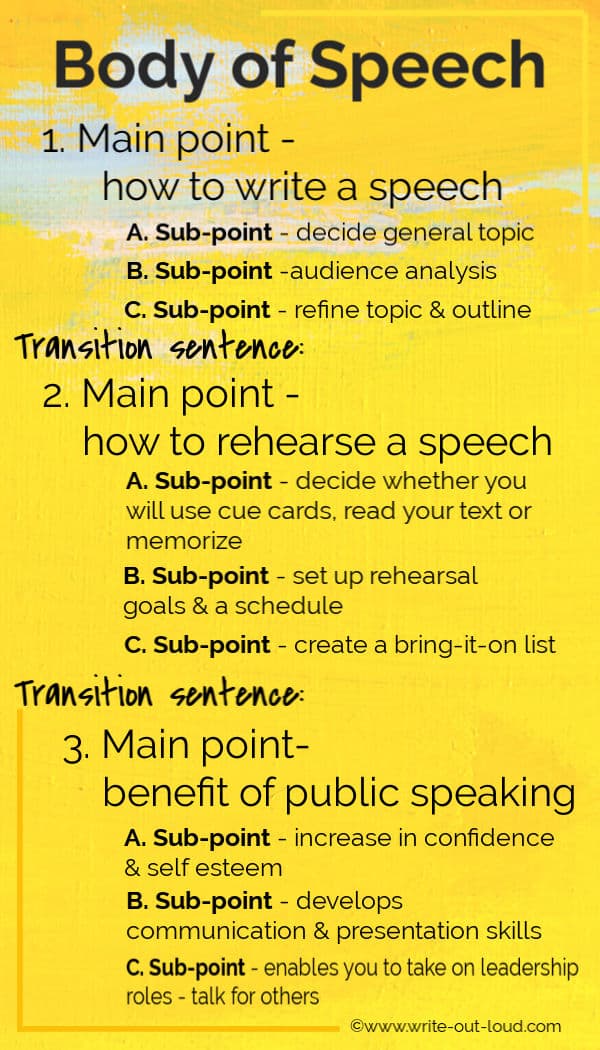

Chapter Eleven – Outlining the Speech

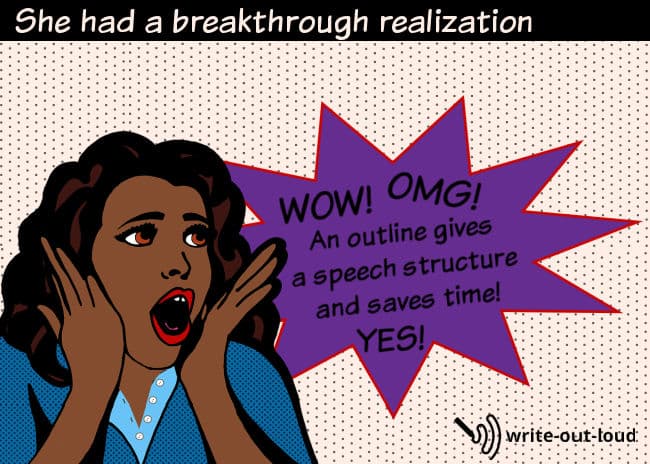

Why outline.

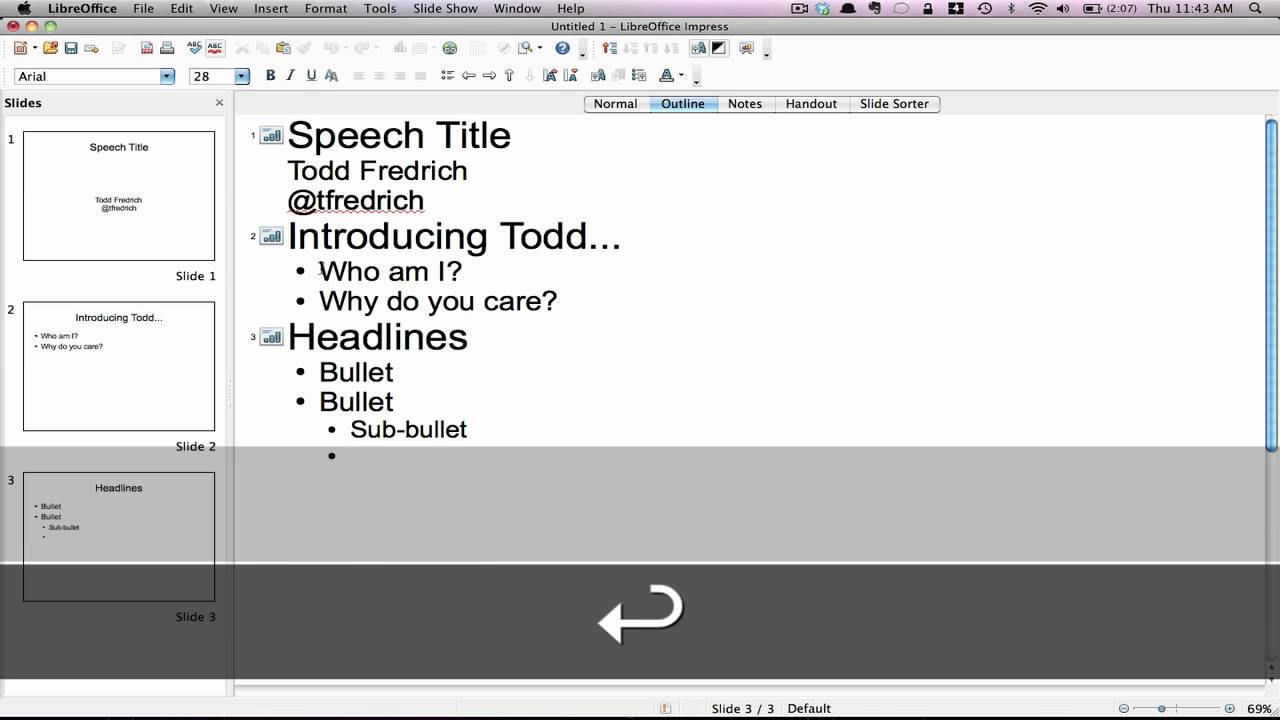

Screenshot from youtube video.

Most speakers and audience members would agree that an organized speech is both easier to present as well as more effective. Public speaking teachers especially believe in the power of organizing your speech, which is why they encourage (and often require) that you create an outline for your speech. Outlines , or textual arrangements of all the various elements of a speech, are a very common way of organizing a speech before it is delivered. Most extemporaneous speakers keep a brief outline with them during the speech as a way to ensure that they do not leave out any important elements and to keep them on track. Writing an outline is also important to the speechwriting process since doing so forces speakers to think about the main points and sub-points, the examples they wish to include, and the ways in which these elements correspond to one another. In short, the outline functions both as an organization tool and as a reference for delivering a speech.

A full-sentence outline lays a strong foundation for your message. It will call on you to have one clear and specific purpose for your message. As we have seen in other chapters of this book, writing your specific purpose in clear language serves you well:

It helps you frame a clear, concrete thesis statement. It helps you exclude irrelevant information. It helps you focus only on information that directly bears on your thesis. It reduces the amount of research you must do. It helps both you and your audience remember the central message of your speech. It suggests what kind of supporting evidence is needed, so less effort is expended in trying to figure out what to do next.

Finally, a solid full-sentence outline helps your audience understand your message because they will be able to follow your reasoning. Remember that live audiences for oral communications lack the ability to “rewind” your message to figure out what you said, so it is critically important to help the audience follow your reasoning as it reaches their ears.

Your authors have noted among their past and present students a reluctance to write full-sentence outlines. It’s a task too often perceived as busywork, unnecessary, time consuming, and restricted. On one hand, we understand that reluctance. But on the other hand, we find that students who carefully write a full-sentence outline show a stronger tendency to give powerful presentations of excellent messages.

Outlines Test the Scope of Content

When you begin with a clear, concrete thesis statement, it acts as kind of compass for your outline. Each of the main points should directly explicate. The test of the scope will be a comparison of each main point to the thesis statement. If you find a poor match, you will know you’ve wandered outside the scope of the thesis.

Let’s say the general purpose of your speech is to inform, and your broad topic area is wind-generated energy. Now you must narrow this to a specific purpose. You have many choices, but let’s say your specific purpose is to inform a group of property owners about the economics of wind farms where electrical energy is generated.

Your first main point could be that modern windmills require a very small land base, making the cost of real estate low. This is directly related to economics. All you need is information to support your claim that only a small land base is needed.

In your second main point, you might be tempted to claim that windmills don’t pollute in the ways other sources do. However, you will quickly note that this claim is unrelated to the thesis. You must resist the temptation to add it. Perhaps in another speech, your thesis will address environmental impact, but in this speech, you must stay within the economic scope. Perhaps you will say that once windmills are in place, they require virtually no maintenance. This claim is related to the thesis. Now all you need is supporting information to support this second claim.

Your third point, the point some audience members will want to hear, is the cost for generating electrical energy with windmills compared with other sources. This is clearly within the scope of energy economics. You should have no difficulty finding authoritative sources of information to support that claim.

When you write in outline form, it is much easier to test the scope of your content because you can visually locate specific information very easily and then check it against your thesis statement.

Outlines Test the Logical Relation of Parts

You have many choices for your topic, and therefore, there are many ways your content can be logically organized. In the example above, we simply listed three main points that were important economic considerations about wind farms. Often the main points of a speech can be arranged into a logical pattern; let’s review some of these patterns:

A chronological pattern arranges main ideas in the order events occur. In some instances, reverse order might make sense. For instance, if your topic is archaeology, you might use the reverse order, describing the newest artifacts first.

A cause-and-effect pattern calls on you to describe a specific situation and explain what the effect is. However, most effects have more than one cause. Even dental cavities have multiple causes: genetics, poor nutrition, teeth too tightly spaced, sugar, ineffective brushing, and so on. If you choose a cause-and-effect pattern, make sure you have enough reliable support to do the topic justice.

A biographical pattern is usually chronological. In describing the events of an individual’s life, you will want to choose the three most significant events. Otherwise, the speech will end up as a very lengthy and often pointless timeline or bullet point list. For example, Mark Twain had several clear phases in his life. They include his life as a Mississippi riverboat captain, his success as a world-renowned writer and speaker, and his family life. A simple timeline would present great difficulty in highlighting the relationships between important events. An outline, however, would help you emphasize the key events that contributed to Mark Twain’s extraordinary life.

Although a comparison-contrast pattern appears to dictate just two main points, McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond explain how a comparison-and-contrast can be structured as a speech with three main points. They say that “you can easily create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. For example, if you are giving a speech about two different medications, you could start by discussing what the medications’ basic purposes are. Then you could talk about the similarities, and then the differences, between the two medications” [1] .

Whatever logical pattern you use, if you examine your thesis statement and then look at the three main points in your outline, you should easily be able to see the logical way in which they relate.

Outlines Test the Relevance of Supporting Ideas

When you create an outline, you can clearly see that you need supporting evidence for each of your main points. For instance, using the example above, your first main point claims that less land is needed for windmills than for other utilities. Your supporting evidence should be about the amount of acreage required for a windmill and the amount of acreage required for other energy generation sites, such as nuclear power plants or hydroelectric generators. Your sources should come from experts in economics, economic development, or engineering. The evidence might even be expert opinion but not the opinions of ordinary people. The expert opinion will provide stronger support for your point.

Similarly, your second point claims that once a wind turbine is in place, there is virtually no maintenance cost. Your supporting evidence should show how much annual maintenance for a windmill costs, and what the costs are for other energy plants. If you used a comparison with nuclear plants to support your first main point, you should do so again for the sake of consistency. It becomes very clear, then, that the third main point about the amount of electricity and its profitability needs authoritative references to compare it to the profit from energy generated at a nuclear power plant. In this third main point, you should make use of just a few well-selected statistics from authoritative sources to show the effectiveness of wind farms compared to the other energy sources you’ve cited.

Where do you find the kind of information you would need to support these main points? A reference librarian can quickly guide you to authoritative statistics and help you make use of them.

An important step you will notice is that the full-sentence outline includes its authoritative sources within the text. This is a major departure from the way you’ve learned to write a research paper. In a research paper, you can add that information to the end of a sentence, leaving the reader to turn to the last page for a fuller citation. In a speech, however, your listeners can’t do that. From the beginning of the supporting point, you need to fully cite your source so your audience can assess its importance.

Because this is such a profound change from the academic habits that you’re probably used to, you will have to make a concerted effort to overcome the habits of the past and provide the information your listeners need when they need it.

Outlines Test the Balance and Proportion of the Speech

Part of the value of writing a full-sentence outline is the visual space you use for each of your main points. Is each main point of approximately the same importance? Does each main point have the same number of supporting points? If you find that one of your main points has eight supporting points while the others only have three each, you have two choices: either choose the best three from the eight supporting points or strengthen the authoritative support for your other two main points.

Remember that you should use the best supporting evidence you can find even if it means investing more time in your search for knowledge.

As you write the preparation outline, you may find it necessary to rearrange your points or to add or subtract supporting material. You may also realize that some of your main points are sufficiently supported while others are lacking. The final draft of your preparation outline should include full sentences, making up a complete script of your entire speech. In most cases, however, the preparation outline is reserved for planning purposes only and is translated into a speaking outline before you deliver the speech.

Outlines Serve as Notes during the Speech

Although we recommend writing a full-sentence outline during the speech preparation phase, you should also create a shortened outline that you can use as notes, a speaking outline, which allows for strong delivery. If you were to use the full-sentence outline when delivering your speech, you would do a great deal of reading, which would limit your ability to give eye contact and use gestures, hurting your connection with your audience.

Although some cases call for reading a speech verbatim from the full-sentence outline (manuscript delivery), in most cases speakers will simply refer to their speaking outline for quick reminders and to ensure that they do not omit any important information. For this reason, we recommend writing a short phrase speaking outline on 5×7 notecards to use when you deliver your speech.

In the next section, we will explore more fully how to create preparation and speaking outlines.

Outline Structure

Because an outline is used to arrange all of the elements of your speech, it makes sense that the outline itself has an organizational hierarchy and a common format. Although there are a variety of outline styles, generally they follow the same pattern. Main ideas are preceded by Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.). Sub-points are preceded by capital letters (A, B, C, etc.), then Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.), and finally lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.). Each level of subordination is also differentiated from its predecessor by indenting a few spaces. Indenting makes it easy to find your main points, sub-points, and the supporting points and examples below them. Since there are three sections to your speech— introduction, body, and conclusion— your outline needs to include all of them. Each of these sections is titled and the main points start with Roman numeral I.

OUTLINE FORMATTING GUIDE

Title: Organizing Your Public Speech

Topic: Organizing public speeches

Specific Purpose Statement: To inform my audience about the various ways in which they can organize their public speeches.

Thesis Statement: A variety of organizational styles can used to organize public speeches.

Introduction Paragraph that gets the attention of the audience, establishes goodwill with the audience, states the purpose of the speech, and previews the speech and its structure.

(Transition)

I. Main point

A. Sub-point B. Sub-point C. Sub-point

1. Supporting point 2. Supporting point

Conclusion Paragraph that prepares the audience for the end of the speech, presents any final appeals, and summarizes and wraps up the speech.

Bibliography

In addition to these formatting suggestions, there are some additional elements that should be included at the beginning of your outline: the title, topic, specific purpose statement, and thesis statement. These elements are helpful to you, the speechwriter, since they remind you what, specifically, you are trying to accomplish in your speech. They are also helpful to anyone reading and assessing your outline since knowing what you want to accomplish will determine how they perceive the elements included in your outline. Additionally, you should write out the transitional statements that you will use to alert audiences that you are moving from one point to another. These are included in parentheses between main points. At the end of the outlines, you should include bibliographic information for any outside resources you mention during the speech. These should be cited using whatever citations style your professor requires. The textbox entitled “Outline Formatting Guide” above provides an example of the appropriate outline format.

Preparation Outline Examples

This book contains the preparation outline for an informative speech the author gave about making guacamole (see third section). In this example, the title, specific purpose, and thesis precedes the speech. Depending on your instructor’s requirements, you may need to include these details plus additional information (like visual aids). It is also a good idea to keep these details at the top of your document as you write the speech since they will help keep you on track to developing an organized speech that is in line with your specific purpose and helps prove your thesis. At the end of this text, in Part 3, you will find full-length examples of Preparation (Full Sentence) Outlines, written by students just like you!

Using the Speaking Outline

“TAG speaks of others first” by Texas Military Forces. CC-BY-ND .

A speaking outline is the outline you will prepare for use when delivering the speech. The speaking outline is much more succinct than the preparation outline and includes brief phrases or words that remind the speakers of the points they need to make, plus supporting material and signposts. [2] The words or phrases used on the speaking outline should briefly encapsulate all of the information needed to prompt the speaker to accurately deliver the speech. Although some cases call for reading a speech verbatim from the full-sentence outline, in most cases speakers will simply refer to their speaking outline for quick reminders and to ensure that they do not omit any important information. Because it uses just words or short phrases, and not full sentences, the speaking outline can easily be transferred to index cards that can be referenced during a speech.

Speaking instructors often have requirements for how you should format the speaking outline. When formatting your speaking outline, here are a few tips:

First, write large enough so that you do not have to bring the cards close to your eyes to read them. Second, make sure you have the cards in the correct order and bound together in some way so that they do not get out of order. Third, just in case your cards do get out of order (this happens too often!), be sure that you number each in the top right corner so you can quickly and easily get things organized. Fourth, try not to fiddle with the cards when you are speaking. It is best to lay them down if you have a podium or table in front of you. If not, practice reading from them in front of a mirror. You should be able to look down quickly, read the text, and then return to your gaze to the audience.

Any intelligent fool can make things bigger and more complex… It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction. – Albert Einstein

- McCroskey, J. C., Wrench, J. S., & Richmond, V. P., (2003). Principles of public speaking . Indianapolis, IN: The College Network.

- Beebe, S. A. & Beebe, S. J. (2003). The public speaking handbook (5th edition). Boston: Pearson. ↵

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Cc licensed content, shared previously.

- Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Chapter 8 Outlining Your Speech. Authored by : Joshua Trey Barnett. Provided by : University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- TAG speaks of others first. Authored by : Texas Military Forces. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/texasmilitaryforces/5560449970/ . License : CC BY-ND: Attribution-NoDerivatives

Principles of Public Speaking Copyright © 2022 by Katie Gruber is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Rice Speechwriting

Mastering speech outlines: tips & examples, crafting a speech outline: tips & examples.

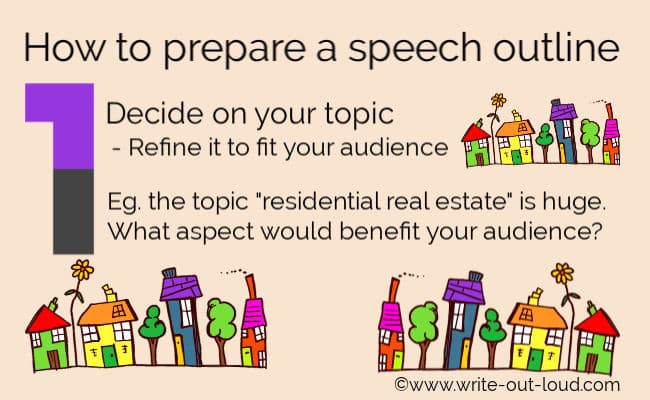

Crafting a speech can be daunting, but it doesn’t have to be. A well-crafted speech outline can make all the difference in helping you deliver your message effectively. In this blog, we’ll go over why a speech outline is so important and how to prepare for creating one. We’ll also provide a step-by-step guide on how to craft a compelling speech outline. From choosing a topic that resonates with your audience to constructing a strong thesis statement and developing engaging hooks, we’ve got you covered. Additionally, we’ll share tips on perfecting your speech outline and enhancing your delivery with visual aids. Whether you’re preparing for a business presentation or giving a keynote address , this blog will provide you with all the tools you need to deliver an impactful speech that leaves a lasting impression on your audience.

Understanding the Importance of a Speech Outline

Crafting a speech outline is crucial for effective public speaking. It ensures a clear, logical flow of ideas and helps in organizing the content of your public speech. By providing a roadmap for the entire speech, a preparation outline ensures that the main points are communicated clearly, helping you to stay focused and on track during your public speaking engagement. The part of your speech outline also serves as a visual aid, further enhancing the structuring of your thoughts and ideas, making it an essential part of your public speaking preparation.

Benefits of a Well-Crafted Speech Outline

Crafting a well-structured speech outline is essential for delivering a compelling public speech. It ensures a clear organizational pattern, aiding in capturing and maintaining the audience’s attention throughout the speech. By logically ordering the content, a well-crafted speech outline facilitates smooth transitions between key points, supporting subpoints, and transitional statements, thus enhancing the overall coherence of the speech. Moreover, it serves as a valuable organization tool, assisting in preparing a structured and impactful public speaking presentation. Therefore, dedicating time to the preparation outline is an integral part of any successful public speech, providing a roadmap for the seamless delivery of the content.

Structuring Thoughts and Ideas

Crafting a speech outline contributes to the seamless delivery of key points in public speaking. It aids in the preparation of the body of your speech, ensuring a coherent flow of ideas and serves as a preparation outline for each part of your speech. By effectively structuring the speech topic, the public speech outline ensures the logical organization of the main points and supports the overall organization and preparation of the speech’s content. The outline facilitates a well-structured and engaging presentation to the audience, enhancing the overall impact of your public speech.

Preparing to Craft a Speech Outline

Researching the topic thoroughly is paramount for preparing a comprehensive speech outline, enabling a well-structured and informative public speech. Determining the length of the speech is essential in deciding the depth and breadth of the preparation outline, ensuring that all key points are effectively covered. Recognizing the different types of speech outlines is integral to cater to the specific requirements and expectations of the audience. Considering the instructor’s guidelines is crucial in crafting a preparation outline that aligns with the given parameters. The process of preparing a speech outline involves strategically deciding on the overall organizational pattern of the speech, ensuring a logical flow and coherence throughout the presentation.

Researching Your Topic

Thoroughly researching the topic is crucial for crafting a well-structured speech outline. It enables the identification of key points and ensures the inclusion of accurate and credible information. Familiarity with the topic is essential for preparing a comprehensive outline, part of your speech preparation. Conducting extensive research is an integral part of gathering relevant information to form the foundation of a well-crafted public speech. By understanding the significance of in-depth research, you can ensure that your public speaking content is well-prepared and effectively delivered.

Deciding on the Length of Your Speech

When crafting a speech outline, one must consider the length of the speech as a crucial factor. The chosen length not only determines the overall organization of the outline but also influences its depth and structure. It plays a significant role in decision-making regarding the content to be included. Additionally, considering the attention span of the audience members is essential in determining the ideal length of the speech. The preparation outline needs to align with the selected length to ensure that the content is tailored appropriately for the intended duration.

Recognizing Different Types of Speech Outlines

Understanding the various options in organizing a public speech is crucial for delivering an impactful presentation. Identifying the most suitable outline for your topic is key, as it influences the entire preparation process and organization of the content. Becoming familiar with different types of public speaking outlines, such as a preparation outline or a speaking outline, enables you to structure your thoughts effectively. Selecting the right type of outline, such as preparation outline or speaking outline, ensures that each part of your speech, from the introduction to the conclusion, is well-organized and cohesive. This thoughtful consideration of different types of outlines ultimately enhances the overall delivery and reception of your public speech.

Step-by-Step Guide to Crafting a Speech Outline

Crafting a speech outline begins with selecting a captivating topic, followed by formulating a strong thesis statement. Integrating the speech topic’s keywords is essential, and the initial outline draft should encompass the main talking points. Moreover, organizing supporting points and subpoints is crucial in the preparation outline. Each of these steps contributes to the coherent structuring of thoughts and ideas for the public speech. Embracing this process as part of your speech preparation ensures that each segment becomes a seamless part of your speech. Through this careful planning, you can align your speech with your audience, whether it’s a presentation, a social media post, or a public speaking event.

Choosing a Compelling Topic

Selecting an engaging subject ensures sustained audience interest and involvement during the public speech. The preparation outline process commences with the choice of a captivating speech topic that resonates with the audience. A compelling topic facilitates the overall structure of the public speaking outline, ensuring coherence and relevance. The topic’s significance to the audience directly influences the preparation of the public speech outline, guiding the inclusion of impactful content. Crafting a well-organized public speech outline initiates with the deliberate selection of a topic that appeals to the audience

Constructing a Strong Thesis Statement

Constructing a strong thesis statement is essential for providing clear direction to the preparation outline of a speech. It forms the foundation of logical organization, encompassing the main point and guiding the arrangement of the speech outline. A well-constructed thesis statement ensures that the speech outline effectively captures the main ideas and supporting points, making it an integral part of any public speaking engagement. This process involves careful consideration of the audience’s interests and the overall relevance of the topic to ensure a comprehensive and engaging public speech. Incorporating the NLP terms “public speaking” and “preparation outline” enhances the development of a captivating thesis statement, making it a crucial part of constructing an effective speech outline.

Developing Engaging Hooks

Crafting a captivating speech outline begins with capturing the audience’s attention using engaging hooks. Anecdotes or props can be effectively utilized to create a compelling speech introduction that instantly grabs the audience’s interest. Moreover, incorporating key words and phrases strategically within the introduction can further pique the audience’s curiosity. It’s crucial that the first thing the audience hears is attention-grabbing, setting the tone for the entire speech. These engaging hooks are essential in ensuring the audience’s undivided attention right from the start, creating a strong foundation for the rest of the speech.

Building the Body of Your Speech

To keep the audience engaged, ensure the body of your speech is well-organized in a logical order. Smoothly transition between supporting points using transitional statements. Structuring main points effectively can be done by including subpoints and bullet points. Remember, the speaker’s body language is vital for maintaining the audience’s attention. Convey the topic effectively by including main points, supporting points, and subpoints in the body of your speech. Public speaking requires a well-structured body to effectively deliver the part of your speech that contains key information and ideas. At the end of the speech, it is important to summarize and wrap up the main points to leave a lasting impression on the audience. Successful public speeches on platforms like Facebook stem from thorough preparation outlines and a well-organized body.

Perfecting Your Speech Outline

Crafting a preparation outline is a crucial part of your speech writing process. The first outline you will write is called the preparation outline, also known as a working, practice, or rough outline. The preparation outline is used to work through the various components of your speech in an inventive format. When constructing a speaking outline, it’s important to adhere to the instructor’s requirements and include a thesis statement as the main point. Start with a rough outline to establish the overall organizational pattern before refining it. Your speech writing template should consist of full sentences that guide seamless delivery during public speaking. This preparation outline will serve as a roadmap for every part of your speech, making it easier to deliver a compelling and well-structured public speech.

Reviewing and Refining Your Outline

After completing the speechwriting process, it is crucial to meticulously review and refine the outline to ensure coherence and effectiveness. The entire outline should be crafted in a way that best conveys the speech topic to the audience. This involves refining the rough outline to capture and maintain the audience’s attention throughout. During the review, special attention should be given to the thesis statement, supporting points, and subpoints to effectively refine the speech outline. It is vital to ensure that the chosen type of outline optimally organizes the key points of the speech for seamless delivery and maximum impact. Embracing this reviewing and refining stage ensures that the speech outline is primed for successful public speaking engagements.

Practicing Your Speech

Practicing your speech is essential for perfecting the delivery, including eye contact and body language, during public speaking engagements. It reinforces the main point of the preparation outline and helps emphasize key points effectively to the audience. The conclusion should also be practiced to ensure a strong and impactful end to your public speech. By practicing the speech delivery, you can maintain the audience’s attention and ensure that your message is effectively conveyed. This step is crucial in ensuring that your public speech is engaging and leaves a lasting impression on the audience.

Tips to Enhance Your Speech Delivery

Incorporating visual aids and props during public speaking can effectively enhance the delivery of your public speech, making it more engaging for the audience. Anecdotes are an impactful way to illustrate key points, capturing the audience’s attention and enhancing the overall delivery of your speech. Establishing consistent eye contact with the audience members is crucial as it helps in creating a strong connection during the delivery of your public speech. The second aspect of your speech outline should primarily focus on the best ways to deliver your speech to the audience members, ensuring that it resonates effectively. By integrating anecdotes, props, and visual aids, you can significantly enhance the delivery of your public speech, making it more compelling and impactful.

How Can Visual Aids Improve Your Speech?

Incorporating visual aids in your speech can greatly enhance its impact. Visual aids reinforce key points, clarify complex information, and capture the audience’s attention. They create a visual impact and contribute to a memorable delivery. Utilizing visual aids effectively can take your speech to the next level.

In conclusion, crafting a well-structured speech outline is crucial for delivering a successful and impactful speech. It helps you organize your thoughts, develop a strong thesis statement, and engage your audience with compelling hooks. By structuring your speech into an introduction, body, and conclusion, you can effectively convey your message and maintain a flow of ideas. Additionally, reviewing and refining your outline, as well as practicing your speech, will contribute to your confidence and delivery on the day of the speech. Don’t forget to utilize visual aids to enhance your presentation and make it more memorable for your audience. With these tips and examples, you’ll be well-equipped to create an effective speech outline and deliver a memorable speech.

Master the Art of How to Start a Speech

Wedding toast from groom’s father: spreading happiness.

Popular Posts

How to write a retirement speech that wows: essential guide.

June 4, 2022

The Best Op Ed Format and Op Ed Examples: Hook, Teach, Ask (Part 2)

June 2, 2022

Inspiring Awards Ceremony Speech Examples

November 21, 2023

Mastering the Art of How to Give a Toast

Short award acceptance speech examples: inspiring examples, best giving an award speech examples.

November 22, 2023

Sentence Sense Newsletter

- Personal Development

- Sales Training

- Business Training

- Time Management

- Leadership Training

- Book Writing

- Public Speaking

- Live Speaker Training With Brian

- See Brian Speak

- Coaching Programs

- Become a Coach

- Personal Success

- Sales Success

- Business Success

- Leadership Success

How To Write A Speech Outline

Do you have a speech coming up soon, but don’t know where to start when it comes to writing it?

Don’t worry.

The best way to start writing your speech is to first write an outline.

While to some, an outline may seem like an unnecessary extra step — after giving hundreds of speeches in my own career, I can assure you that first creating a speech outline is truly the best way to design a strong presentation that your audience will remember.

Should I Write A Speech Outline?

You might be wondering if you should really bother with a preparation outline. Is a speaking outline worth your time, or can you get through by just keeping your supporting points in mind?

Again, I highly recommend that all speakers create an outline as part of their speechwriting process. This step is an extremely important way to organize your main ideas and all the various elements of your speech in a way that will command your audience’s attention.

Good public speaking teachers will agree that an outline—even if it’s a rough outline—is the easiest way to propel you forward to a final draft of an organized speech that audience members will love.

Here are a few of the biggest benefits of creating an outline before diving straight into your speech.

Gain More Focus

By writing an outline, you’ll be able to center the focus of your speech where it belongs—on your thesis statement and main idea.

Remember, every illustration, example, or piece of information you share in your speech should be relevant to the key message you’re trying to deliver. And by creating an outline, you can ensure that everything relates back to your main point.

Keep Things Organized

Your speech should have an overall organizational pattern so that listeners will be able to follow your thoughts. You want your ideas to be laid out in a logical order that’s easy to track, and for all of the speech elements to correspond.

An outline serves as a structure or foundation for your speech, allowing you to see all of your main points laid out so you can easily rearrange them into an order that makes sense for easy listening.

Create Smoother Transitions

A speaking outline helps you create smoother transitions between the different parts of your speech.

When you know what’s happening before and after a certain section, it will be easy to accurately deliver transitional statements that make sense in context. Instead of seeming like several disjointed ideas, the parts of your speech will naturally flow into each other.

Save Yourself Time

An outline is an organization tool that will save you time and effort when you get ready to write the final draft of your speech. When you’re working off of an outline to write your draft, you can overcome “blank page syndrome.”

It will be much easier to finish the entire speech because the main points and sub-points are already clearly laid out for you.

Your only job is to finish filling everything in.

Preparing to Write A Speech Outline

Now that you know how helpful even the most basic of speech outlines can be in helping you write the best speech, here’s how to write the best outline for your next public speaking project.

How Long Should A Speech Outline Be?

The length of your speech outline will depend on the length of your speech. Are you giving a quick two-minute talk or a longer thirty-minute presentation? The length of your outline will reflect the length of your final speech.

Another factor that will determine the length of your outline is how much information you actually want to include in the outline. For some speakers, bullet points of your main points might be enough. In other cases, you may feel more comfortable with a full-sentence outline that offers a more comprehensive view of your speech topic.

The length of your outline will also depend on the type of outline you’re using at any given moment.

Types of Outlines

Did you know there are several outline types? Each type of outline is intended for a different stage of the speechwriting process. Here, we’re going to walk through:

- Working outlines

- Full-sentence outlines

- Speaking outlines

Working Outline

Think of your working outline as the bare bones of your speech—the scaffolding you’re using as you just start to build your presentation. To create a working outline, you will need:

- A speech topic

- An idea for the “hook” in your introduction

- A thesis statement

- 3-5 main points (each one should make a primary claim that you support with references)

- A conclusion

Each of your main points will also have sub-points, but we’ll get to those in a later step.

The benefit of a working outline is that it’s easy to move things around. If you think your main points don’t make sense in a certain order—or that one point needs to be scrapped entirely—it’s no problem to make the needed changes. You won’t be deleting any of your prior hard work because you haven’t really done any work yet.

Once you are confident in this “skeleton outline,” you can move on to the next, where you’ll start filling in more detailed information.

Full-sentence outline

As the name implies, your full-sentence outline contains full sentences. No bullet points or scribbled, “talk about x, y, z here.” Instead, research everything you want to include and write out the information in full sentences.

Why is this important? A full-sentence outline helps ensure that you are:

- Including all of the information your audience needs to know

- Organizing the material well

- Staying within any time constraints you’ve been given

Don’t skip this important step as you plan your speech.

Speaking outline

The final type of outline you’ll need is a speaking outline. When it comes to the level of detail, this outline is somewhere in between your working outline and a full-sentence outline.

You’ll include the main parts of your speech—the introduction, main points, and conclusion. But you’ll add a little extra detail about each one, too. This might be a quote that you don’t want to misremember or just a few words to jog your memory of an anecdote to share.

When you actually give your speech, this is the outline you will use. It might seem like it makes more sense to use your detailed full-sentence outline up on stage. However, if you use this outline, it’s all too easy to fall into the trap of reading your speech—which is not what you want to do. You’ll likely sound much more natural if you use your speaking outline.

How to Write A Speech Outline

We’ve covered the types of outlines you’ll work through as you write your speech. Now, let’s talk more about how you’ll come up with the information to add to each outline type.

Pick A Topic

Before you can begin writing an outline, you have to know what you’re going to be speaking about. In some situations, you may have a topic given to you—especially if you are in a public speaking class and must follow the instructor’s requirements. But in many cases, speakers must come up with their own topic for a speech.

Consider your audience and what kind of educational, humorous, or otherwise valuable information they need to hear. Your topic and message should of course be highly relevant to them. If you don’t know your audience well enough to choose a topic, that’s a problem.

Your audience is your first priority. If possible, however, it’s also helpful to choose a topic that appeals to you. What’s something you’re interested in and/or knowledgeable about?