The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

Critical thinking in nursing clinical practice, education and research: From attitudes to virtue

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Consolidated Research Group Quantitative Psychology (2017-SGR-269), University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 2 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Consolidated Research Group on Gender, Identity and Diversity (2017-SGR-1091), University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 3 Department of Fundamental Care and Medical Surgital Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 4 Multidisciplinary Nursing Research Group, Vall d'Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Vall d'Hebron Hospital, Barcelona, Spain.

- PMID: 33029860

- DOI: 10.1111/nup.12332

Critical thinking is a complex, dynamic process formed by attitudes and strategic skills, with the aim of achieving a specific goal or objective. The attitudes, including the critical thinking attitudes, constitute an important part of the idea of good care, of the good professional. It could be said that they become a virtue of the nursing profession. In this context, the ethics of virtue is a theoretical framework that becomes essential for analyse the critical thinking concept in nursing care and nursing science. Because the ethics of virtue consider how cultivating virtues are necessary to understand and justify the decisions and guide the actions. Based on selective analysis of the descriptive and empirical literature that addresses conceptual review of critical thinking, we conducted an analysis of this topic in the settings of clinical practice, training and research from the virtue ethical framework. Following JBI critical appraisal checklist for text and opinion papers, we argue the need for critical thinking as an essential element for true excellence in care and that it should be encouraged among professionals. The importance of developing critical thinking skills in education is well substantiated; however, greater efforts are required to implement educational strategies directed at developing critical thinking in students and professionals undergoing training, along with measures that demonstrate their success. Lastly, we show that critical thinking constitutes a fundamental component in the research process, and can improve research competencies in nursing. We conclude that future research and actions must go further in the search for new evidence and open new horizons, to ensure a positive effect on clinical practice, patient health, student education and the growth of nursing science.

Keywords: critical thinking; critical thinking attitudes; nurse education; nursing care; nursing research.

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Attitude of Health Personnel*

- Education, Nursing / methods

- Nursing Process

- Nursing Research / methods

Grants and funding

- PREI-19-007-B/School of Nursing. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Barcelona

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Author Guidelines

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(4): 73-76

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180804.03

Critical Thinking and Decision Making in Nursing Administration: A Philosophical Analysis

Lilian G. Tumapang

College of Advanced Education, Ifugao State University, Nayon, Lamut, Ifugao, Philippines

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

Nurse administrators are compelled to manage the dynamic health care system and advance excellence at every level of the organization. A challenge that besets nursing management points at developing the capacity of nurse executives to apply critical thinking in making decisions and establishing priorities in the clinical setting. To this direction, the theory titled “Critical thinking and decision making in nursing administration” aims to elucidate the association of critical thinking to the decision-making process in the context of nursing management. As for the philosophical standpoint, the author advocates for the “no-one-philosophical view-fits-all” approach or perspective. The key point of analysis would lie in the employment of the concepts, ideas, beliefs, and notions derived a given phenomenon.

Keywords: Critical thinking, Decision-making, Nursing administration, Philosophical perspective

Cite this paper: Lilian G. Tumapang, Critical Thinking and Decision Making in Nursing Administration: A Philosophical Analysis, International Journal of Nursing Science , Vol. 8 No. 4, 2018, pp. 73-76. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180804.03.

2.3 Tools for Prioritizing

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A “high-acuity” patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a “high-intensity” patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs. [1]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3. [2] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2. [3]

Table 2.3 Example of a Patient Acuity Tool [4]

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments. [5]

As a practicing nurse, you will be oriented to the elements of acuity ratings within your health care organization, but it is also important to understand how you can use these acuity ratings for your own prioritization and task delineation. Let’s consider the Scenario B in the following box to better understand how acuity ratings can be useful for prioritizing nursing care.

You report to work at 6 a.m. for your nursing shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. Prior to receiving the handoff report from your night shift nursing colleagues, you review the unit staffing grid and see that you have been assigned to four patients to start your day. The patients have the following acuity ratings:

Patient A: 45-year-old patient with paraplegia admitted for an infected sacral wound, with an acuity rating of 4.

Patient B: 87-year-old patient with pneumonia with a low grade fever of 99.7 F and receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute via nasal cannula, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient C: 63-year-old patient who is postoperative Day 1 from a right total hip replacement and is receiving pain management via a PCA pump, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient D: 83-year-old patient admitted with a UTI who is finishing an IV antibiotic cycle and will be discharged home today, with an acuity rating of 1.

Based on the acuity rating system, your patient assignment load receives an overall acuity score of 9. Consider how you might use their acuity ratings to help you prioritize your care. Based on what is known about the patients related to their acuity rating, whom might you identify as your care priority? Although this can feel like a challenging question to answer because of the many unknown elements in the situation using acuity numbers alone, Patient A with an acuity rating of 4 would be identified as the care priority requiring assessment early in your shift.

Although acuity can a useful tool for determining care priorities, it is important to recognize the limitations of this tool and consider how other patient needs impact prioritization.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

When thinking back to your first nursing or psychology course, you may recall a historical theory of human motivation based on various levels of human needs called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs reflects foundational human needs with progressive steps moving towards higher levels of achievement. This hierarchy of needs is traditionally represented as a pyramid with the base of the pyramid serving as essential needs that must be addressed before one can progress to another area of need. [6] See Figure 2.1 [7] for an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs places physiological needs as the foundational base of the pyramid. [8] Physiological needs include oxygen, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, and excretion. The second level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects safety needs. Safety needs include elements that keep individuals safe from harm. Examples of safety needs in health care include fall precautions. The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects emotional needs such as love and a sense of belonging. These needs are often reflected in an individual’s relationships with family members and friends. The top two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy include esteem and self-actualization. An example of addressing these needs in a health care setting is helping an individual build self-confidence in performing blood glucose checks that leads to improved self-management of their diabetes.

So how does Maslow’s theory impact prioritization? To better understand the application of Maslow’s theory to prioritization, consider Scenario C in the following box.

You are an emergency response nurse working at a local shelter in a community that has suffered a devastating hurricane. Many individuals have relocated to the shelter for safety in the aftermath of the hurricane. Much of the community is still without electricity and clean water, and many homes have been destroyed. You approach a young woman who has a laceration on her scalp that is bleeding through her gauze dressing. The woman is weeping as she describes the loss of her home stating, “I have lost everything! I just don’t know what I am going to do now. It has been a day since I have had water or anything to drink. I don’t know where my sister is, and I can’t reach any of my family to find out if they are okay!”

Despite this relatively brief interaction, this woman has shared with you a variety of needs. She has demonstrated a need for food, water, shelter, homeostasis, and family. As the nurse caring for her, it might be challenging to think about where to begin her care. These thoughts could be racing through your mind:

Should I begin to make phone calls to try and find her family? Maybe then she would be able to calm down.

Should I get her on the list for the homeless shelter so she wouldn’t have to worry about where she will sleep tonight?

She hasn’t eaten in awhile; I should probably find her something to eat.

All of these needs are important and should be addressed at some point, but Maslow’s hierarchy provides guidance on what needs must be addressed first. Use the foundational level of Maslow’s pyramid of physiological needs as the top priority for care. The woman is bleeding heavily from a head wound and has had limited fluid intake. As the nurse caring for this patient, it is important to immediately intervene to stop the bleeding and restore fluid volume. Stabilizing the patient by addressing her physiological needs is required before undertaking additional measures such as contacting her family. Imagine if instead you made phone calls to find the patient’s family and didn’t address the bleeding or dehydration – you might return to a severely hypovolemic patient who has deteriorated and may be near death. In this example, prioritizing emotional needs above physiological needs can lead to significant harm to the patient.

Although this is a relatively straightforward example, the principles behind the application of Maslow’s hierarchy are essential. Addressing physiological needs before progressing toward additional need categories concentrates efforts on the most vital elements to enhance patient well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy provides the nurse with a helpful framework for identifying and prioritizing critical patient care needs.

Airway, breathing, and circulation, otherwise known by the mnemonic “ABCs,” are another foundational element to assist the nurse in prioritization. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, using the ABCs to guide decision-making concentrates on the most critical needs for preserving human life. If a patient does not have a patent airway, is unable to breathe, or has inadequate circulation, very little of what else we do matters. The patient’s ABCs are reflected in Maslow’s foundational level of physiological needs and direct critical nursing actions and timely interventions. Let’s consider Scenario D in the following box regarding prioritization using the ABCs and the physiological base of Maslow’s hierarchy.

You are a nurse on a busy cardiac floor charting your morning assessments on a computer at the nurses’ station. Down the hall from where you are charting, two of your assigned patients are resting comfortably in Room 504 and Room 506. Suddenly, both call lights ring from the rooms, and you answer them via the intercom at the nurses’ station.

Room 504 has an 87-year-old male who has been admitted with heart failure, weakness, and confusion. He has a bed alarm for safety and has been ringing his call bell for assistance appropriately throughout the shift. He requires assistance to get out of bed to use the bathroom. He received his morning medications, which included a diuretic about 30 minutes previously, and now reports significant urge to void and needs assistance to the bathroom.

Room 506 has a 47-year-old woman who was hospitalized with new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. The patient underwent a cardioversion procedure yesterday that resulted in successful conversion of her heart back into normal sinus rhythm. She is reporting via the intercom that her “heart feels like it is doing that fluttering thing again” and she is having chest pain with breathlessness.

Based upon these two patient scenarios, it might be difficult to determine whom you should see first. Both patients are demonstrating needs in the foundational physiological level of Maslow’s hierarchy and require assistance. To prioritize between these patients’ physiological needs, the nurse can apply the principles of the ABCs to determine intervention. The patient in Room 506 reports both breathing and circulation issues, warning indicators that action is needed immediately. Although the patient in Room 504 also has an urgent physiological elimination need, it does not overtake the critical one experienced by the patient in Room 506. The nurse should immediately assess the patient in Room 506 while also calling for assistance from a team member to assist the patient in Room 504.

Prioritizing what should be done and when it can be done can be a challenging task when several patients all have physiological needs. Recently, there has been professional acknowledgement of the cognitive challenge for novice nurses in differentiating physiological needs. To expand on the principles of prioritizing using the ABCs, the CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras. [9]

“Critical” patient needs require immediate action. Examples of critical needs align with the ABCs and Maslow’s physiological needs, such as symptoms of respiratory distress, chest pain, and airway compromise. No matter the complexity of their shift, nurses can be assured that addressing patients’ critical needs is the correct prioritization of their time and energies.

After critical patient care needs have been addressed, nurses can then address “urgent” needs. Urgent needs are characterized as needs that cause patient discomfort or place the patient at a significant safety risk. [10]

The third part of the CURE hierarchy reflects “routine” patient needs. Routine patient needs can also be characterized as “typical daily nursing care” because the majority of a standard nursing shift is spent addressing routine patient needs. Examples of routine daily nursing care include actions such as administering medication and performing physical assessments. [11] Although a nurse’s typical shift in a hospital setting includes these routine patient needs, they do not supersede critical or urgent patient needs.

The final component of the CURE hierarchy is known as “extras.” Extras refer to activities performed in the care setting to facilitate patient comfort but are not essential. [12] Examples of extra activities include providing a massage for comfort or washing a patient’s hair. If a nurse has sufficient time to perform extra activities, they contribute to a patient’s feeling of satisfaction regarding their care, but these activities are not essential to achieve patient outcomes.

Let’s apply the CURE mnemonic to patient care in the following box.

If we return to Scenario D regarding patients in Room 504 and 506, we can see the patient in Room 504 is having urgent needs. He is experiencing a physiological need to urgently use the restroom and may also have safety concerns if he does not receive assistance and attempts to get up on his own because of weakness. He is on a bed alarm, which reflects safety considerations related to his potential to get out of bed without assistance. Despite these urgent indicators, the patient in Room 506 is experiencing a critical need and takes priority. Recall that critical needs require immediate nursing action to prevent patient deterioration. The patient in Room 506 with a rapid, fluttering heartbeat and shortness of breath has a critical need because without prompt assessment and intervention, their condition could rapidly decline and become fatal.

In addition to using the identified frameworks and tools to assist with priority setting, nurses must also look at their patients’ data cues to help them identify care priorities. Data cues are pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition. For example, have the patient’s vital signs worsened over the last few hours? Is there a new laboratory result that is concerning? Data cues are used in conjunction with prioritization frameworks to help the nurse holistically understand the patient’s current status and where nursing interventions should be directed. Common categories of data clues include acute versus chronic conditions, actual versus potential problems, unexpected versus expected conditions, information obtained from the review of a patient’s chart, and diagnostic information.

Acute Versus Chronic Conditions

A common data cue that nurses use to prioritize care is considering if a condition or symptom is acute or chronic. Acute conditions have a sudden and severe onset. These conditions occur due to a sudden illness or injury, and the body often has a significant response as it attempts to adapt. Chronic conditions have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time. The difference between an acute versus a chronic condition relates to the body’s adaptation response. Individuals with chronic conditions often experience less symptom exacerbation because their body has had time to adjust to the illness or injury. Let’s consider an example of two patients admitted to the medical-surgical unit complaining of pain in Scenario E in the following box.

As part of your patient assignment on a medical-surgical unit, you are caring for two patients who both ring the call light and report pain at the start of the shift. Patient A was recently admitted with acute appendicitis, and Patient B was admitted for observation due to weakness. Not knowing any additional details about the patients’ conditions or current symptoms, which patient would receive priority in your assessment? Based on using the data cue of acute versus chronic conditions, Patient A with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis would receive top priority for assessment over a patient with chronic pain due to osteoarthritis. Patients experiencing acute pain require immediate nursing assessment and intervention because it can indicate a change in condition. Acute pain also elicits physiological effects related to the stress response, such as elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, and should be addressed quickly.

Actual Versus Potential Problems

Nursing diagnoses and the nursing care plan have significant roles in directing prioritization when interpreting assessment data cues. Actual problems refer to a clinical problem that is actively occurring with the patient. A risk problem indicates the patient may potentially experience a problem but they do not have current signs or symptoms of the problem actively occurring.

Consider an example of prioritizing actual and potential problems in Scenario F in the following box.

A 74-year-old woman with a previous history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. She has generalized weakness, a weak cough, and crackles in the bases of her lungs. She is receiving IV antibiotics, fluids, and oxygen therapy. The patient can sit at the side of the bed and ambulate with the assistance of staff, although she requires significant encouragement to ambulate.

Nursing diagnoses are established for this patient as part of the care planning process. One nursing diagnosis for this patient is Ineffective Airway Clearance . This nursing diagnosis is an actual problem because the patient is currently exhibiting signs of poor airway clearance with an ineffective cough and crackles in the lungs. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include coughing and deep breathing, administering nebulizer treatment, and evaluating the effectiveness of oxygen therapy. The patient also has the nursing diagnosis Risk for Skin Breakdown based on her weakness and lack of motivation to ambulate. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include repositioning every two hours and assisting with ambulation twice daily.

The established nursing diagnoses provide cues for prioritizing care. For example, if the nurse enters the patient’s room and discovers the patient is experiencing increased shortness of breath, nursing interventions to improve the patient’s respiratory status receive top priority before attempting to get the patient to ambulate.

Although there may be times when risk problems may supersede actual problems, looking to the “actual” nursing problems can provide clues to assist with prioritization.

Unexpected Versus Expected Conditions

In a similar manner to using acute versus chronic conditions as a cue for prioritization, it is also important to consider if a client’s signs and symptoms are “expected” or “unexpected” based on their overall condition. Unexpected conditions are findings that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury. Expected conditions are findings that are likely to occur or are anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury. Unexpected findings often require immediate action by the nurse.

Let’s apply this tool to the two patients previously discussed in Scenario E. As you recall, both Patient A (with acute appendicitis) and Patient B (with weakness and diagnosed with osteoarthritis) are reporting pain. Acute pain typically receives priority over chronic pain. But what if both patients are also reporting nausea and have an elevated temperature? Although these symptoms must be addressed in both patients, they are “expected” symptoms with acute appendicitis (and typically addressed in the treatment plan) but are “unexpected” for the patient with osteoarthritis. Critical thinking alerts you to the unexpected nature of these symptoms in Patient B, so they receive priority for assessment and nursing interventions.

Handoff Report/Chart Review

Additional data cues that are helpful in guiding prioritization come from information obtained during a handoff nursing report and review of the patient chart. These data cues can be used to establish a patient’s baseline status and prioritize new clinical concerns based on abnormal assessment findings. Let’s consider Scenario G in the following box based on cues from a handoff report and how it might be used to help prioritize nursing care.

Imagine you are receiving the following handoff report from the night shift nurse for a patient admitted to the medical-surgical unit with pneumonia:

At the beginning of my shift, the patient was on room air with an oxygen saturation of 93%. She had slight crackles in both bases of her posterior lungs. At 0530, the patient rang the call light to go to the bathroom. As I escorted her to the bathroom, she appeared slightly short of breath. Upon returning the patient to bed, I rechecked her vital signs and found her oxygen saturation at 88% on room air and respiratory rate of 20. I listened to her lung sounds and noticed more persistent crackles and coarseness than at bedtime. I placed the patient on 2 L/minute of oxygen via nasal cannula. Within 5 minutes, her oxygen saturation increased to 92%, and she reported increased ease in respiration.

Based on the handoff report, the night shift nurse provided substantial clinical evidence that the patient may be experiencing a change in condition. Although these changes could be attributed to lack of lung expansion that occurred while the patient was sleeping, there is enough information to indicate to the oncoming nurse that follow-up assessment and interventions should be prioritized for this patient because of potentially worsening respiratory status. In this manner, identifying data cues from a handoff report can assist with prioritization.

Now imagine the night shift nurse had not reported this information during the handoff report. Is there another method for identifying potential changes in patient condition? Many nurses develop a habit of reviewing their patients’ charts at the start of every shift to identify trends and “baselines” in patient condition. For example, a chart review reveals a patient’s heart rate on admission was 105 beats per minute. If the patient continues to have a heart rate in the low 100s, the nurse is not likely to be concerned if today’s vital signs reveal a heart rate in the low 100s. Conversely, if a patient’s heart rate on admission was in the 60s and has remained in the 60s throughout their hospitalization, but it is now in the 100s, this finding is an important cue requiring prioritized assessment and intervention.

Diagnostic Information

Diagnostic results are also important when prioritizing care. In fact, the National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission include prompt reporting of important test results. New abnormal laboratory results are typically flagged in a patient’s chart or are reported directly by phone to the nurse by the laboratory as they become available. Newly reported abnormal results, such as elevated blood levels or changes on a chest X-ray, may indicate a patient’s change in condition and require additional interventions. For example, consider Scenario H in which you are the nurse providing care for five medical-surgical patients.

You completed morning assessments on your assigned five patients. Patient A previously underwent a total right knee replacement and will be discharged home today. You are about to enter Patient A’s room to begin discharge teaching when you receive a phone call from the laboratory department, reporting a critical hemoglobin of 6.9 gm/dL on Patient B. Rather than enter Patient A’s room to perform discharge teaching, you immediately reprioritize your care. You call the primary provider to report Patient B’s critical hemoglobin level and determine if additional intervention, such as a blood transfusion, is required.

- Oregon Health Authority. (2021, April 29). Hospital nurse staffing interpretive guidance on staffing for acuity & intensity . Public Health Division, Center for Health Protection. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/HEALTHCAREPROVIDERSFACILITIES/HEALTHCAREHEALTHCAREREGULATIONQUALITYIMPROVEMENT/Documents/NSInterpretiveGuidanceAcuity.pdf ↵

- Ingram, A., & Powell, J. (2018). Patient acuity tool on a medical surgical unit. American Nurse . https://www.myamericannurse.com/patient-acuity-medical-surgical-unit/ ↵

- Kidd, M., Grove, K., Kaiser, M., Swoboda, B., & Taylor, A. (2014). A new patient-acuity tool promotes equitable nurse-patient assignments. American Nurse Today, 9 (3), 1-4. https://www.myamericannurse.com/a-new-patient-acuity-tool-promotes-equitable-nurse-patient-assignments / ↵

- Welton, J. M. (2017). Measuring patient acuity. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 47 (10), 471. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000516 ↵

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review , 50 (4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 ↵

- " Maslow's_hierarchy_of_needs.svg " by J. Finkelstein is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Stoyanov, S. (2017). An analysis of Abraham Maslow's A Theory of Human Motivation (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781912282517 ↵

- Kohtz, C., Gowda, C., & Guede, P. (2017). Cognitive stacking: Strategies for the busy RN. Nursing2021, 47 (1), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000510758.31326.92 ↵

Intentional causation of harmful or offensive contact with another's person without that person's consent.

An act of restraining another person causing that person to be confined in a bounded area. Restraints can be physical, verbal, or chemical.

The right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information kept private.

An act of making negative, malicious, and false remarks about another person to damage their reputation.

An act of deceiving an individual for personal gain.

The failure to exercise the ordinary care a reasonable person would use in similar circumstances.

A specific term used for negligence committed by a professional with a license.

The person bringing the lawsuit.

The parties named in a lawsuit.

Legal obligations nurses have to their patients to adhere to current standards of practice.

State law providing protections against negligence claims to individuals who render aid to people experiencing medical emergencies outside of clinical environments.

Leadership and Management of Nursing Care Copyright © 2022 by Kim Belcik and Open Resources for Nursing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

We use cookies on our website to support technical features that enhance your user experience, and to help us improve our website. By continuing to use this website, you accept our privacy policy .

- Student Login

- No-Cost Professional Certificates

- Call Us: 888-549-6755

- 888-559-6763

- Search site Search our site Search Now Close

- Request Info

Skip to Content (Press Enter)

Why Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing Matter (And What You Can Do to Develop Them)

By Hannah Meinke on 07/05/2021

The nursing profession tends to attract those who have natural nurturing abilities, a desire to help others, and a knack for science or anatomy. But there is another important skill that successful nurses share, and it's often overlooked: the ability to think critically.

Identifying a problem, determining the best solution and choosing the most effective method to solve the program are all parts of the critical thinking process. After executing the plan, critical thinkers reflect on the situation to figure out if it was effective and if it could have been done better. As you can see, critical thinking is a transferable skill that can be leveraged in several facets of your life.

But why is it so important for nurses to use? We spoke with several experts to learn why critical thinking skills in nursing are so crucial to the field, the patients and the success of a nurse. Keep reading to learn why and to see how you can improve this skill.

Why are critical thinking skills in nursing important?

You learn all sorts of practical skills in nursing school, like flawlessly dressing a wound, taking vitals like a pro or starting an IV without flinching. But without the ability to think clearly and make rational decisions, those skills alone won’t get you very far—you need to think critically as well.

“Nurses are faced with decision-making situations in patient care, and each decision they make impacts patient outcomes. Nursing critical thinking skills drive the decision-making process and impact the quality of care provided,” says Georgia Vest, DNP, RN and senior dean of nursing at the Rasmussen University School of Nursing.

For example, nurses often have to make triage decisions in the emergency room. With an overflow of patients and limited staff, they must evaluate which patients should be treated first. While they rely on their training to measure vital signs and level of consciousness, they must use critical thinking to analyze the consequences of delaying treatment in each case.

No matter which department they work in, nurses use critical thinking in their everyday routines. When you’re faced with decisions that could ultimately mean life or death, the ability to analyze a situation and come to a solution separates the good nurses from the great ones.

How are critical thinking skills acquired in nursing school?

Nursing school offers a multitude of material to master and upholds high expectations for your performance. But in order to learn in a way that will actually equip you to become an excellent nurse, you have to go beyond just memorizing terms. You need to apply an analytical mindset to understanding course material.

One way for students to begin implementing critical thinking is by applying the nursing process to their line of thought, according to Vest. The process includes five steps: assessment, diagnosis, outcomes/planning, implementation and evaluation.

“One of the fundamental principles for developing critical thinking is the nursing process,” Vest says. “It needs to be a lived experience in the learning environment.”

Nursing students often find that there are multiple correct solutions to a problem. The key to nursing is to select the “the most correct” solution—one that will be the most efficient and best fit for that particular situation. Using the nursing process, students can narrow down their options to select the best one.

When answering questions in class or on exams, challenge yourself to go beyond simply selecting an answer. Start to think about why that answer is correct and what the possible consequences might be. Simply memorizing the material won’t translate well into a real-life nursing setting.

How can you develop your critical thinking skills as a nurse?

As you know, learning doesn’t stop with graduation from nursing school. Good nurses continue to soak up knowledge and continually improve throughout their careers. Likewise, they can continue to build their critical thinking skills in the workplace with each shift.

“To improve your critical thinking, pick the brains of the experienced nurses around you to help you get the mindset,” suggests Eileen Sollars, RN ADN, AAS. Understanding how a seasoned nurse came to a conclusion will provide you with insights you may not have considered and help you develop your own approach.

The chain of command can also help nurses develop critical thinking skills in the workplace.

“Another aid in the development of critical thinking I cannot stress enough is the utilization of the chain of command,” Vest says. “In the chain of command, the nurse always reports up to the nurse manager and down to the patient care aide. Peers and fellow healthcare professionals are not in the chain of command. Clear understanding and proper utilization of the chain of command is essential in the workplace.”

How are critical thinking skills applied in nursing?

“Nurses use critical thinking in every single shift,” Sollars says. “Critical thinking in nursing is a paramount skill necessary in the care of your patients. Nowadays there is more emphasis on machines and technical aspects of nursing, but critical thinking plays an important role. You need it to understand and anticipate changes in your patient's condition.”

As a nurse, you will inevitably encounter a situation in which there are multiple solutions or treatments, and you'll be tasked with determining the solution that will provide the best possible outcome for your patient. You must be able to quickly and confidently assess situations and make the best care decision in each unique scenario. It is in situations like these that your critical thinking skills will direct your decision-making.

Do critical thinking skills matter more for nursing leadership and management positions?

While critical thinking skills are essential at every level of nursing, leadership and management positions require a new level of this ability.

When it comes to managing other nurses, working with hospital administration, and dealing with budgets, schedules or policies, critical thinking can make the difference between a smooth-running or struggling department. At the leadership level, nurses need to see the big picture and understand how each part works together.

A nurse manager , for example, might have to deal with being short-staffed. This could require coaching nurses on how to prioritize their workload, organize their tasks and rely on strategies to keep from burning out. A lead nurse with strong critical thinking skills knows how to fully understand the problem and all its implications.

- How will patient care be affected by having fewer staff?

- What kind of strain will be on the nurses?

Their solutions will take into account all their resources and possible roadblocks.

- What work can be delegated to nursing aids?

- Are there any nurses willing to come in on their day off?

- Are nurses from other departments available to provide coverage?

They’ll weigh the pros and cons of each solution and choose those with the greatest potential.

- Will calling in an off-duty nurse contribute to burnout?

- Was this situation a one-off occurrence or something that could require an additional hire in the long term?

Finally, they will look back on the issue and evaluate what worked and what didn’t. With critical thinking skills like this, a lead nurse can affect their entire staff, patient population and department for the better.

Beyond thinking

You’re now well aware of the importance of critical thinking skills in nursing. Even if you already use critical thinking skills every day, you can still work toward strengthening that skill. The more you practice it, the better you will become and the more naturally it will come to you.

If you’re interested in critical thinking because you’d like to move up in your current nursing job, consider how a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) could help you develop the necessary leadership skills.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published in July 2012. It has since been updated to include information relevant to 2021.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn

Request More Information

Talk with an admissions advisor today. Fill out the form to receive information about:

- Program Details and Applying for Classes

- Financial Aid and FAFSA (for those who qualify)

- Customized Support Services

- Detailed Program Plan

There are some errors in the form. Please correct the errors and submit again.

Please enter your first name.

Please enter your last name.

There is an error in email. Make sure your answer has:

- An "@" symbol

- A suffix such as ".com", ".edu", etc.

There is an error in phone number. Make sure your answer has:

- 10 digits with no dashes or spaces

- No country code (e.g. "1" for USA)

There is an error in ZIP code. Make sure your answer has only 5 digits.

Please choose a School of study.

Please choose a program.

Please choose a degree.

The program you have selected is not available in your ZIP code. Please select another program or contact an Admissions Advisor (877.530.9600) for help.

The program you have selected requires a nursing license. Please select another program or contact an Admissions Advisor (877.530.9600) for help.

Rasmussen University is not enrolling students in your state at this time.

By selecting "Submit," I authorize Rasmussen University to contact me by email, phone or text message at the number provided. There is no obligation to enroll. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

About the author

Hannah Meinke

Posted in General Nursing

- nursing education

Related Content

Brianna Flavin | 05.07.2024

Brianna Flavin | 03.19.2024

Robbie Gould | 11.14.2023

Noelle Hartt | 11.09.2023

This piece of ad content was created by Rasmussen University to support its educational programs. Rasmussen University may not prepare students for all positions featured within this content. Please visit www.rasmussen.edu/degrees for a list of programs offered. External links provided on rasmussen.edu are for reference only. Rasmussen University does not guarantee, approve, control, or specifically endorse the information or products available on websites linked to, and is not endorsed by website owners, authors and/or organizations referenced. Rasmussen University is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission, an institutional accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Anderson C. Exploring the role of advanced nurse practitioners in leadership. Nurs Stand. 2018; 33:(2)29-33 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11044

Bass B. The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications.New York (NY): Simon and Schuster; 2010

Cummings G. The call for leadership to influence patient outcomes. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2011; 24:(2)22-5 https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2011.22459

Collaborative leadership: new perspectives in leadership development. 2011. https://tinyurl.com/2usp5yve (accessed 24 February 2021)

Dover N, Lee GA, Raleigh M A rapid review of educational preparedness of advanced clinical practitioners. J Adv Nurs. 2019; 75:(12)3210-3218 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14105

Edwards A. Being an expert professional practitioner. The relational turn in expertise.London: Springer Verlag; 2010

Evans C, Pearce R, Greaves S, Blake H. Advanced clinical practitioners in primary care in the UK: a qualitative study of workforce transformation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17:(12) https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124500

Hamric A, Hanson C, Tracy M, O'Grady E. Advanced practice nursing. An integrative approach.Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Saunders; 2014

Health Education England. Advanced practice. 2021. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/advanced-clinical-practice (accessed 24 February 2021)

Heinen M, van Oostveen C, Peters J, Vermeulen H, Huis A. An integrative review of leadership competencies and attributes in advanced nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2019; 75:(11)2378-2392 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14092

Kotter JP. Leading change.Boston (MA): Harvard Business Review Press; 1996

Kramer M, Maguire P, Schmalenberg CE. Excellence through evidence: the what, when, and where of clinical autonomy. J Nurs Adm. 2006; 36:(10)479-491 https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200610000-00009

Lamb A, Martin-Misener R, Bryant-Lukosius D, Latimer M. Describing the leadership capabilities of advanced practice nurses using a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Open. 2018; 5:(3)400-413 https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.150

Better leadership for tomorrow: NHS leadership review. 2015. https://tinyurl.com/ev7thw68 (accessed 24 February 2021)

Royal College of Nursing. Royal College of Nursing standards for advanced level nursing practice. 2018. https://www.rcn.org.uk/library/subject-guides/advanced-nursing-practice (accessed 24 February 2021)

Scott ES, Miles J. Advancing leadership capacity in nursing. Nurs Adm Q. 2013; 37:(1)77-82 https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182751998

Sheer B, Wong FK. The development of advanced nursing practice globally. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008; 40:(3)204-11 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00242.x

Skår R. The meaning of autonomy in nursing practice. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19:(15-16)2226-2234 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02804.x

Stanley JM, Gannon J, Gabuat J The clinical nurse leader: a catalyst for improving quality and patient safety. J Nurs Manag. 2008; 16:(5)614-622 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00899.x

Swanwick T, Varnam R. Leadership development and primary care. BMJ. 2019; 3:59-61 https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2019-000145

Leadership and management for nurses working at an advanced level

Senior Lecturer, Leadership and Management: Public Health, Birmingham City University

View articles

Leadership and management form a key part of advanced clinical practice (ACP) and work in synergy with the other pillars of advanced practice. Advanced clinical practitioners focus on improving patient outcomes, and with application of evidence-based practice, using extended and expanded skills, they can provide cost-effective care. They are equipped with skills and knowledge, allowing for the expansion of their scope of practice by performing at an advanced level to assist in meeting the needs of people across all healthcare settings and can shape healthcare reform. Advanced practice can be described as a level of practice, rather than a type of practice. There are four leadership domains of advanced nursing practice: clinical leadership, professional leadership, health system leadership and health policy leadership, each requiring a specific skill set, but with some overlaps. All nurses should demonstrate their leadership competencies—collectively as a profession and individually in all settings where they practice.

Leadership and management form an essential part of advanced clinical practice, as outlined by Health Education England (HEE) in 2017:

‘Advanced clinical practice is delivered by experienced, registered health and care practitioners. It is a level of practice characterised by a high degree of autonomy and complex decision making. This is underpinned by a master's level award or equivalent that encompasses the four pillars of clinical practice, leadership and management, education and research, with demonstration of core capabilities and area specific clinical competence …’

There is an appreciation that leadership and management skills work in synergy with the other pillars of advanced practice. Stanley et al (2008) advised that advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) can shape healthcare reform, are trained to focus on improved patient outcomes, and with application of evidence-based practice, using extended and expanded skills, they can provide cost-effective care. ACPs are equipped with skills and knowledge, allowing for the expansion of their scope of practice by performing at an advanced level to assist in meeting the needs of people across all healthcare settings.

When considering a nursing context, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) defined advanced practice as:

‘A level of practice, rather than a type of practice. Advanced nurse practitioners are educated at master's level in clinical practice and have been assessed as competent in practice using their expert clinical knowledge and skills. They have the freedom and authority to act, making autonomous decisions in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of patients.’

Rose (2015) advocated that ACPs also need to respond to, inform and influence policy, and political and practice changes, while being aware of the complex needs of patients and new healthcare demands. Hamric et al (2014) delineated four leadership domains of advanced nursing practice:

- Clinical leadership

- Professional leadership

- Health system leadership

- Health policy leadership.

Each requires a specific skill set, but with some overlaps. These four leadership domains will guide the discussion that follows, with a focus on advanced nurse leadership.

Background: leadership and autonomy

Revisiting the HEE (2021) use of the word ‘leadership’ and the RCN's (2018) use of the term ‘autonomy’ as part of the definition of advanced nurse practitioners will set the scene and enable these two terms to be briefly examined. Naively, or perhaps traditionally and historically, we tend to put administrator and manager roles into a metaphorical box that considers them as formal leaders, while nurses in clinical roles are either not considered as leaders or they are identified as in formal or clinical leaders. As Scott and Miles (2013) stated, leadership is an expected attribute of all registered nurses, and, yet, leadership in the profession is often considered to be role dependent. All nurses—from student to consultant—are leaders, yet defined clinical leadership competencies are often not reflected in undergraduate nurse education. Research examining the impact of leadership demonstrated by nurses on patients, fellow nurses and other professionals and the broader health and care system is deficient ( Cummings, 2011 ). Nurses need to accept that leadership is a core activity of their role at all levels—once this is acknowledged the transition to advanced roles will be easier. Frequently, nurses approach the topic of leadership when studying for advanced practice as if it is something that they have never done and know little about. Yet they already have an enhanced leadership skill set developed throughout their careers, although they often fail to appreciate this. A solid foundation and affirmation that all nurses are leaders should form the basis of advanced practice.

Despite a blurring of boundaries between management and leadership, the two activities are different ( Bass, 2010 ). Working out who leads and who manages is difficult, with the added anomaly that not all managers are leaders, and some people who lead work in management positions. Kotter's seminal interpretation articulated that leadership processes involve setting a direction, aligning people, motivating and inspiring, and that management relates to organisational aspects such as planning, staffing, budgeting, controlling and solving problems ( Kotter, 1996 ). So leaders cope with new challenges and transform organisations, while managers maintain functional operations using resources effectively.

These explanations direct us to consider what is meant by the allied term of autonomy from the individual and organisational perspective. The Cambridge Dictionary (2020) defines autonomy for an individual as ‘independent and having the power to make your own decisions’ and for a group of people as ‘an autonomous organization, country, or region [that] is independent and has the freedom to govern itself’ (https://tinyurl.com/2h5canfa). In nursing, the concept of autonomy has a range of definitions. Skår defined professional autonomy as:

‘Having the authority to make decisions and the freedom to act in accordance with one's professional knowledge base.’

Skår, 2010:2226

In a clinical practice setting, Kramer et al (2006) outlined three dimensions of autonomy: clinical or practice autonomy, organisational autonomy, and work autonomy. However, they also advised caution with the use of the term autonomy because it has different meanings across the literature. Nevertheless, it has a place within advanced nursing roles, especially in connection with leadership.

Leadership and management for advanced practice

Recent research has examined leadership in advanced nursing practice. Hamric et al (2014) delineated four leadership domains. These link with the findings of Heinen et al (2019) in their review of leadership competencies and attributes in advanced nursing practice. The purpose of their research was to establish which leadership competencies are expected of master's level-educated nurses, such as advanced practice nurses and clinical nurse leaders, as described in the international literature. Note that in North America ‘advanced practice nurse’ is used as an umbrella term to include nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists ( Sheer and Wong, 2008 ).

Boxes 1 to 4 are based on the competencies identified by Heinen et al (2019) for the four leadership domains ( Hamric et al, 2014 ), and Box 5 gives some generic competencies that span each of these.

Box 1.Clinical leadership

- Provides leadership for evidence-based practice for a range of conditions and specialties

- Promotes health, facilitates self-care management, optimises patient engagement and progression to higher levels of care and readmissions

- Acts as a resource person, preceptor, mentor/coach, and role model demonstrating critical and reflective thinking

- Acts as a clinical expert, a leadership role in establishing and monitoring standards of practice to improve client care, including intra- and interdisciplinary peer supervision and review

- Analyses organisational systems for barriers and promotes enhancements that affect client healthcare status

- Identifies current relevant scientific health information, the translation of research in practice, the evaluation of practice, improvement of the reliability of healthcare practice and outcomes, and participation in collaborative research

- Acts as a liaison with other health agencies and professionals, and participates in assessing and evaluating healthcare services to optimise outcomes for patients/clients/communities

- Collaborates with health professionals, including physicians, advanced practice nurses, nurse managers and others, to plan, implement and evaluate improvement opportunities

- Aligns practice with overall organisational/contextual goals

- Guides, initiates and leads the development and implementation of standards, practice guidelines, quality assurance, education and research initiatives

Source: adapted from Heinen et al, 2019

Box 2.Professional leadership

- Assumes responsibility for own professional development by education, professional committees and work groups, and contributes to a work environment where continual improvements in practice are pursued

- Participates in professional organisations and activities that influence advanced practice nursing

- Participates in relevant networks: regional, national and international

- Develops leadership in and integrates the role of the nurse practitioner within the healthcare system

- Employs consultative and leadership skills with intraprofessional and interprofessional teams to create change in health care and within complex healthcare delivery systems

- Participates in peer-review activities, eg publications, research and practice

Box 3.Health system leadership

- Contributes to the development, implementation and monitoring of organisational performance standards

- Lead an interprofessional healthcare team with a focus on the delivery of patient-centred care and the evaluation of quality and cost-effectiveness across the healthcare continuum

- Enhances group dynamics, and manages group conflicts within the organisation

- Plans and implements training and provides technical assistance and nursing consultation to health department staff, health providers, policymakers and personnel in other community and governmental agencies and organisations

- Delegates and supervises tasks assigned to allied professional staff

- Creates a culture of ethical standards within organisations and communities

- Identifies internal and external issues that may impact delivery of essential medical and public health services

- Possesses a working knowledge of the healthcare system and its component parts (sites of care, delivery models, payment models and the roles of healthcare professionals, patients, caregivers and unlicensed professionals)

Box 4.Health policy

- Guides, initiates and provides leadership in policy-related activities to influence practice, health services and public policy

- Articulates the value of nursing to key stakeholders and policymakers

Source: Heinen et al, 2019

Box 5.Generic competencies spanning the four domains

- Possesses advanced communication skills/processes to lead quality improvement and patient safety initiatives in healthcare systems

- Uses principles of business, finance, economics, and health policy to develop and implement effective plans for practice-level and/or system-wide practice initiatives that will improve the quality of care delivery

- Advocates for and participates in creating an organisational environment that supports safe client care, collaborative practice and professional growth

- Creates positive healthy (work) environments and maintains a climate in which team members feel heard and safe

- Uses mentoring and coaching to prepare future generations of nurse leaders

- Provides evaluation and resolution of ethical and legal issues within healthcare systems relating to the use of information, information technology, communication networks, and patient care technology

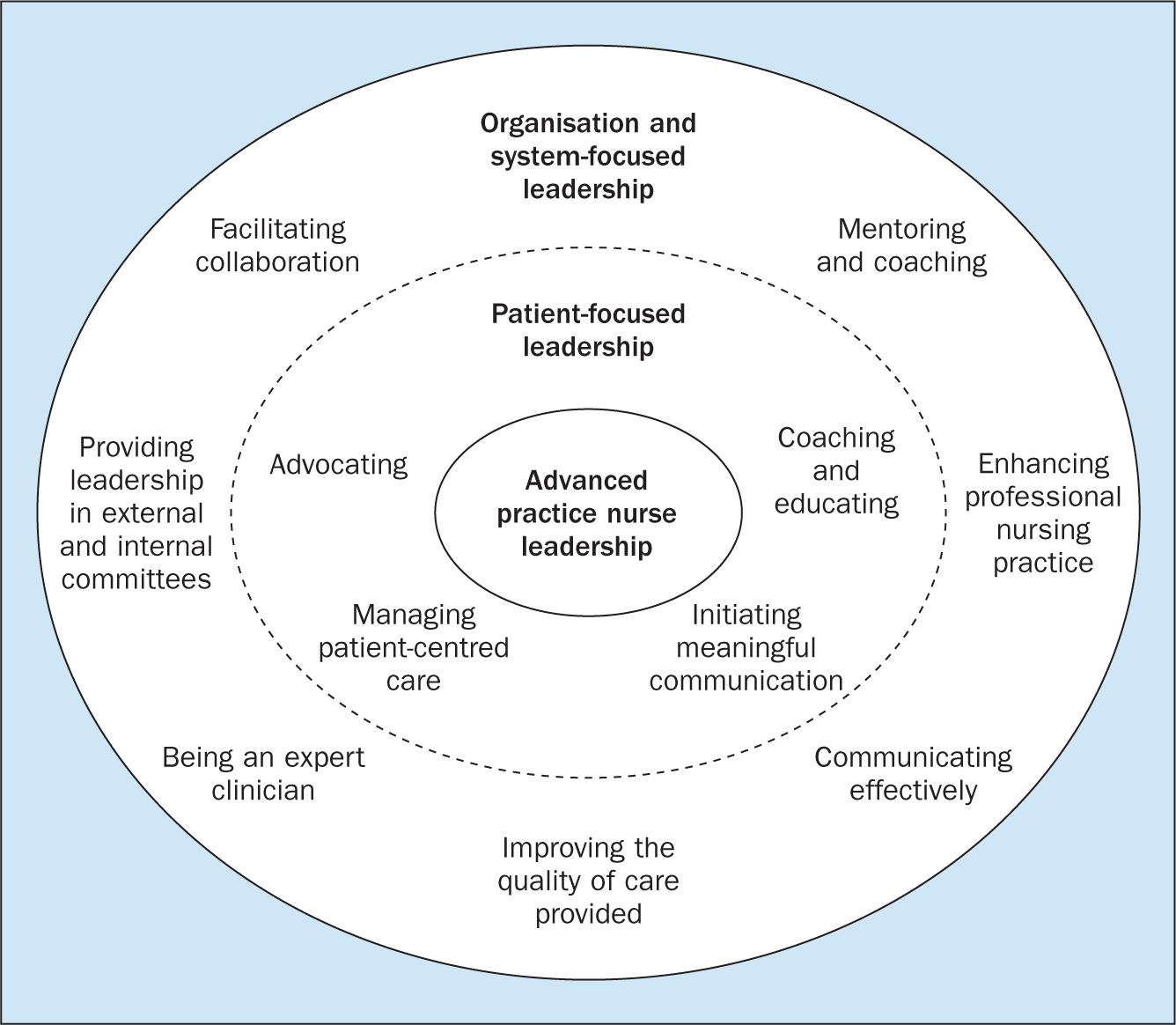

The findings presented in Boxes 1 to 5 provide a research-based scoping of the international literature to identify aspects of leadership competencies connected with advanced nursing practice ( Heinen et al, 2019 ). Revisiting the theoretical differences between leadership and management ( Kotter, 1996 ), it can be appreciated that many of these competencies are blurred, with both existing as part of advanced roles. The clinical, professional and health system domains dominate the number of competencies recorded, giving an idea of the weight given by nurses to different areas of leadership. Competencies relating to the health policy domain were minimal. This is supported by a study describing the leadership capabilities of a sample of 14 advanced practice nurses in Canada using a qualitative descriptive study ( Lamb et al, 2018 ). Two overarching themes describing leadership were identified: ‘patient-focused leadership’ and ‘organisation and system-focused leadership’. Patient-focused leadership comprised capabilities intended to have an impact on patients and families. Organisation and system-focused leadership included capabilities intended to impact nurses, other healthcare providers, the organisation or larger healthcare system. Figure 1 summarises the leadership themes and capability domains identified in Lamb et al's study (2018) .

These findings also support the theory that advanced nurses do not recognise their wide reach as a major leadership part of their roles. In addition, it should be stated that all advanced nursing roles have their own idiosyncrasies based upon the individual practitioner, the environment and organisational needs; there is no ‘one size fits all’.

Multiprofessional working, leadership and the ACP role

With a move in the UK to multiprofessional working, especially in England, and changes towards core advanced practice skills crossing professional boundaries ( HEE, 2021 ) ACPs need proactive skills in cementing their leadership roles within teams. Anderson (2018) advised that successful multiprofessional working needs the individual professional to know the ‘standpoint’ of other professionals to enable their own understanding of complex problems. Edwards (2010) cautioned that professionals may work together and share personal values, but rarely do they work inter-professionally. The ACP role is complex, requiring autonomy and leadership of self within various aspects of the roles required of the individual in distinctive settings, in addition to performing and leading in teams often with professionals from other specialties.