Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

Published on January 20, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

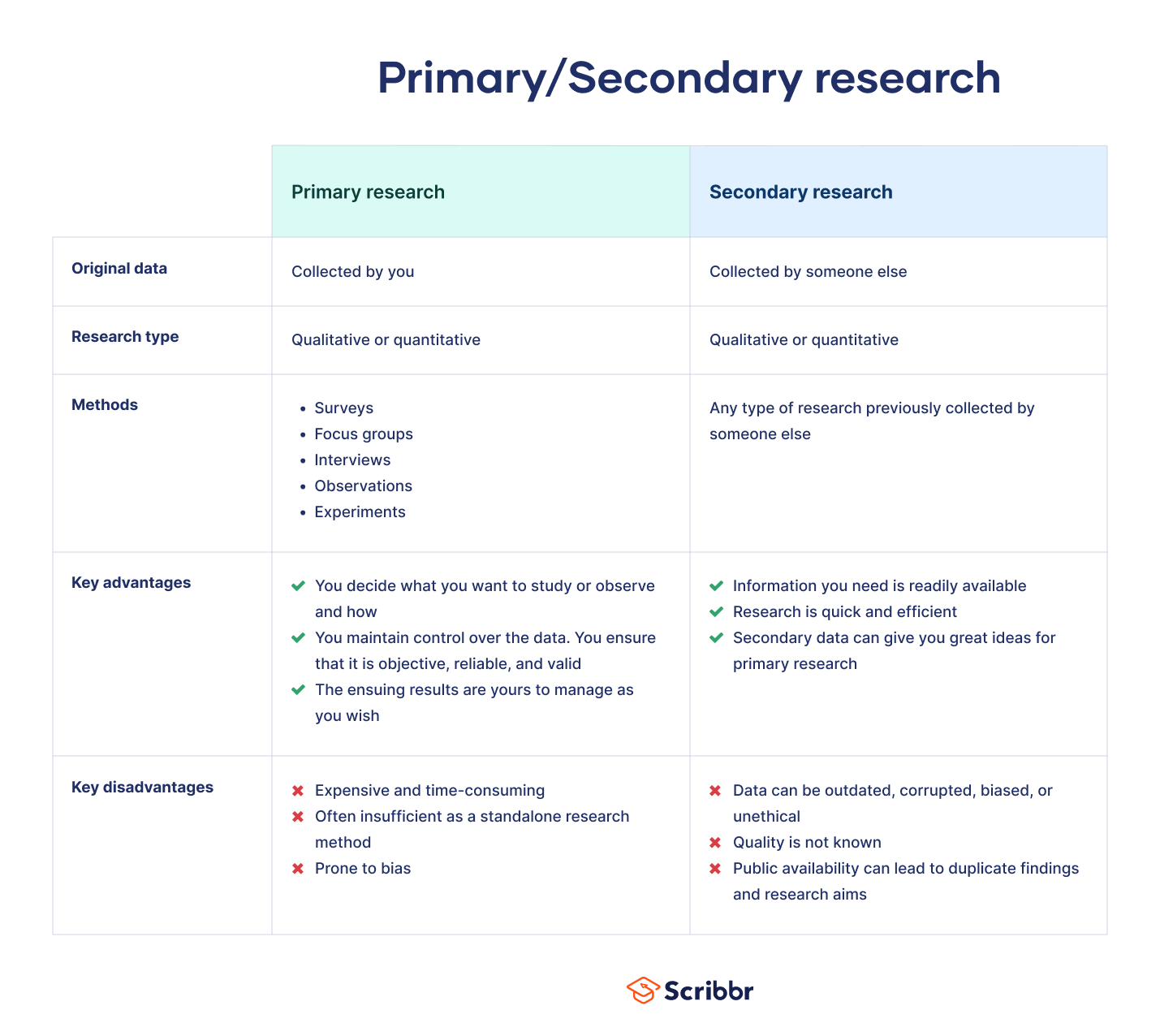

Secondary research is a research method that uses data that was collected by someone else. In other words, whenever you conduct research using data that already exists, you are conducting secondary research. On the other hand, any type of research that you undertake yourself is called primary research .

Secondary research can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. It often uses data gathered from published peer-reviewed papers, meta-analyses, or government or private sector databases and datasets.

Table of contents

When to use secondary research, types of secondary research, examples of secondary research, advantages and disadvantages of secondary research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Secondary research is a very common research method, used in lieu of collecting your own primary data. It is often used in research designs or as a way to start your research process if you plan to conduct primary research later on.

Since it is often inexpensive or free to access, secondary research is a low-stakes way to determine if further primary research is needed, as gaps in secondary research are a strong indication that primary research is necessary. For this reason, while secondary research can theoretically be exploratory or explanatory in nature, it is usually explanatory: aiming to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Secondary research can take many forms, but the most common types are:

Statistical analysis

Literature reviews, case studies, content analysis.

There is ample data available online from a variety of sources, often in the form of datasets. These datasets are often open-source or downloadable at a low cost, and are ideal for conducting statistical analyses such as hypothesis testing or regression analysis .

Credible sources for existing data include:

- The government

- Government agencies

- Non-governmental organizations

- Educational institutions

- Businesses or consultancies

- Libraries or archives

- Newspapers, academic journals, or magazines

A literature review is a survey of preexisting scholarly sources on your topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant themes, debates, and gaps in the research you analyze. You can later apply these to your own work, or use them as a jumping-off point to conduct primary research of your own.

Structured much like a regular academic paper (with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion), a literature review is a great way to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject. It is usually qualitative in nature and can focus on a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. A case study is a great way to utilize existing research to gain concrete, contextual, and in-depth knowledge about your real-world subject.

You can choose to focus on just one complex case, exploring a single subject in great detail, or examine multiple cases if you’d prefer to compare different aspects of your topic. Preexisting interviews , observational studies , or other sources of primary data make for great case studies.

Content analysis is a research method that studies patterns in recorded communication by utilizing existing texts. It can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature, depending on whether you choose to analyze countable or measurable patterns, or more interpretive ones. Content analysis is popular in communication studies, but it is also widely used in historical analysis, anthropology, and psychology to make more semantic qualitative inferences.

Secondary research is a broad research approach that can be pursued any way you’d like. Here are a few examples of different ways you can use secondary research to explore your research topic .

Secondary research is a very common research approach, but has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of secondary research

Advantages include:

- Secondary data is very easy to source and readily available .

- It is also often free or accessible through your educational institution’s library or network, making it much cheaper to conduct than primary research .

- As you are relying on research that already exists, conducting secondary research is much less time consuming than primary research. Since your timeline is so much shorter, your research can be ready to publish sooner.

- Using data from others allows you to show reproducibility and replicability , bolstering prior research and situating your own work within your field.

Disadvantages of secondary research

Disadvantages include:

- Ease of access does not signify credibility . It’s important to be aware that secondary research is not always reliable , and can often be out of date. It’s critical to analyze any data you’re thinking of using prior to getting started, using a method like the CRAAP test .

- Secondary research often relies on primary research already conducted. If this original research is biased in any way, those research biases could creep into the secondary results.

Many researchers using the same secondary research to form similar conclusions can also take away from the uniqueness and reliability of your research. Many datasets become “kitchen-sink” models, where too many variables are added in an attempt to draw increasingly niche conclusions from overused data . Data cleansing may be necessary to test the quality of the research.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/secondary-research/

Largan, C., & Morris, T. M. (2019). Qualitative Secondary Research: A Step-By-Step Guide (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Peloquin, D., DiMaio, M., Bierer, B., & Barnes, M. (2020). Disruptive and avoidable: GDPR challenges to secondary research uses of data. European Journal of Human Genetics , 28 (6), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0596-x

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, primary research | definition, types, & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a case study | definition, examples & methods, what is your plagiarism score.

Library Guides

Dissertations 4: methodology: methods.

- Introduction & Philosophy

- Methodology

Primary & Secondary Sources, Primary & Secondary Data

When describing your research methods, you can start by stating what kind of secondary and, if applicable, primary sources you used in your research. Explain why you chose such sources, how well they served your research, and identify possible issues encountered using these sources.

Definitions

There is some confusion on the use of the terms primary and secondary sources, and primary and secondary data. The confusion is also due to disciplinary differences (Lombard 2010). Whilst you are advised to consult the research methods literature in your field, we can generalise as follows:

Secondary sources

Secondary sources normally include the literature (books and articles) with the experts' findings, analysis and discussions on a certain topic (Cottrell, 2014, p123). Secondary sources often interpret primary sources.

Primary sources

Primary sources are "first-hand" information such as raw data, statistics, interviews, surveys, law statutes and law cases. Even literary texts, pictures and films can be primary sources if they are the object of research (rather than, for example, documentaries reporting on something else, in which case they would be secondary sources). The distinction between primary and secondary sources sometimes lies on the use you make of them (Cottrell, 2014, p123).

Primary data

Primary data are data (primary sources) you directly obtained through your empirical work (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Secondary data

Secondary data are data (primary sources) that were originally collected by someone else (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Comparison between primary and secondary data

| Primary data | Secondary data |

| Data collected directly | Data collected from previously done research, existing research is summarised and collated to enhance the overall effectiveness of the research. |

| Examples: Interviews (face-to-face or telephonic), Online surveys, Focus groups and Observations | Examples: data available via the internet, non-government and government agencies, public libraries, educational institutions, commercial/business information |

| Advantages: •Data collected is first hand and accurate. •Data collected can be controlled. No dilution of data. •Research method can be customized to suit personal requirements and needs of the research. | Advantages: •Information is readily available •Less expensive and less time-consuming •Quicker to conduct |

| Disadvantages: •Can be quite extensive to conduct, requiring a lot of time and resources •Sometimes one primary research method is not enough; therefore a mixed method is require, which can be even more time consuming. | Disadvantages: •It is necessary to check the credibility of the data •May not be as up to date •Success of your research depends on the quality of research previously conducted by others. |

Use

Virtually all research will use secondary sources, at least as background information.

Often, especially at the postgraduate level, it will also use primary sources - secondary and/or primary data. The engagement with primary sources is generally appreciated, as less reliant on others' interpretations, and closer to 'facts'.

The use of primary data, as opposed to secondary data, demonstrates the researcher's effort to do empirical work and find evidence to answer her specific research question and fulfill her specific research objectives. Thus, primary data contribute to the originality of the research.

Ultimately, you should state in this section of the methodology:

What sources and data you are using and why (how are they going to help you answer the research question and/or test the hypothesis.

If using primary data, why you employed certain strategies to collect them.

What the advantages and disadvantages of your strategies to collect the data (also refer to the research in you field and research methods literature).

Quantitative, Qualitative & Mixed Methods

The methodology chapter should reference your use of quantitative research, qualitative research and/or mixed methods. The following is a description of each along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research uses numerical data (quantities) deriving, for example, from experiments, closed questions in surveys, questionnaires, structured interviews or published data sets (Cottrell, 2014, p93). It normally processes and analyses this data using quantitative analysis techniques like tables, graphs and statistics to explore, present and examine relationships and trends within the data (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2015, p496).

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| The study can be undertaken on a broader scale, generating large amounts of data that contribute to generalisation of results | Quantitative methods can be difficult, expensive and time consuming (especially if using primary data, rather than secondary data). |

| Suitable when the phenomenon is relatively simple, and can be analysed according to identified variables. | Not everything can be easily measured. |

|

| Less suitable for complex social phenomena. |

|

| Less suitable for why type questions. |

Qualitative research

Qualitative research is generally undertaken to study human behaviour and psyche. It uses methods like in-depth case studies, open-ended survey questions, unstructured interviews, focus groups, or unstructured observations (Cottrell, 2014, p93). The nature of the data is subjective, and also the analysis of the researcher involves a degree of subjective interpretation. Subjectivity can be controlled for in the research design, or has to be acknowledged as a feature of the research. Subject-specific books on (qualitative) research methods offer guidance on such research designs.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Qualitative methods are good for in-depth analysis of individual people, businesses, organisations, events. | The findings can be accurate about the particular case, but not generally applicable. |

| Sample sizes don’t need to be large, so the studies can be cheaper and simpler. | More prone to subjectivity. |

Mixed methods

Mixed-method approaches combine both qualitative and quantitative methods, and therefore combine the strengths of both types of research. Mixed methods have gained popularity in recent years.

When undertaking mixed-methods research you can collect the qualitative and quantitative data either concurrently or sequentially. If sequentially, you can for example, start with a few semi-structured interviews, providing qualitative insights, and then design a questionnaire to obtain quantitative evidence that your qualitative findings can also apply to a wider population (Specht, 2019, p138).

Ultimately, your methodology chapter should state:

Whether you used quantitative research, qualitative research or mixed methods.

Why you chose such methods (and refer to research method sources).

Why you rejected other methods.

How well the method served your research.

The problems or limitations you encountered.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains mixed methods research in the following video:

LinkedIn Learning Video on Academic Research Foundations: Quantitative

The video covers the characteristics of quantitative research, and explains how to approach different parts of the research process, such as creating a solid research question and developing a literature review. He goes over the elements of a study, explains how to collect and analyze data, and shows how to present your data in written and numeric form.

Link to quantitative research video

Some Types of Methods

There are several methods you can use to get primary data. To reiterate, the choice of the methods should depend on your research question/hypothesis.

Whatever methods you will use, you will need to consider:

why did you choose one technique over another? What were the advantages and disadvantages of the technique you chose?

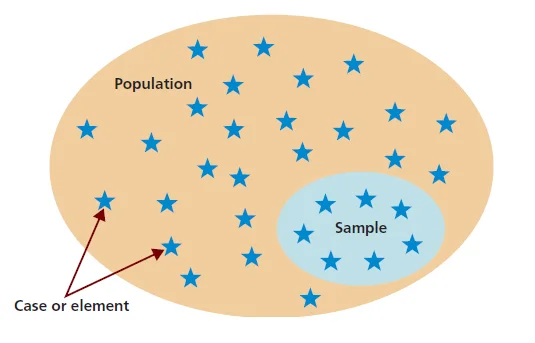

what was the size of your sample? Who made up your sample? How did you select your sample population? Why did you choose that particular sampling strategy?)

ethical considerations (see also tab...)

safety considerations

validity

feasibility

recording

procedure of the research (see box procedural method...).

Check Stella Cottrell's book Dissertations and Project Reports: A Step by Step Guide for some succinct yet comprehensive information on most methods (the following account draws mostly on her work). Check a research methods book in your discipline for more specific guidance.

Experiments

Experiments are useful to investigate cause and effect, when the variables can be tightly controlled. They can test a theory or hypothesis in controlled conditions. Experiments do not prove or disprove an hypothesis, instead they support or not support an hypothesis. When using the empirical and inductive method it is not possible to achieve conclusive results. The results may only be valid until falsified by other experiments and observations.

For more information on Scientific Method, click here .

Observations

Observational methods are useful for in-depth analyses of behaviours in people, animals, organisations, events or phenomena. They can test a theory or products in real life or simulated settings. They generally a qualitative research method.

Questionnaires and surveys

Questionnaires and surveys are useful to gain opinions, attitudes, preferences, understandings on certain matters. They can provide quantitative data that can be collated systematically; qualitative data, if they include opportunities for open-ended responses; or both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Interviews

Interviews are useful to gain rich, qualitative information about individuals' experiences, attitudes or perspectives. With interviews you can follow up immediately on responses for clarification or further details. There are three main types of interviews: structured (following a strict pattern of questions, which expect short answers), semi-structured (following a list of questions, with the opportunity to follow up the answers with improvised questions), and unstructured (following a short list of broad questions, where the respondent can lead more the conversation) (Specht, 2019, p142).

This short video on qualitative interviews discusses best practices and covers qualitative interview design, preparation and data collection methods.

Focus groups

In this case, a group of people (normally, 4-12) is gathered for an interview where the interviewer asks questions to such group of participants. Group interactions and discussions can be highly productive, but the researcher has to beware of the group effect, whereby certain participants and views dominate the interview (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p419). The researcher can try to minimise this by encouraging involvement of all participants and promoting a multiplicity of views.

This video focuses on strategies for conducting research using focus groups.

Check out the guidance on online focus groups by Aliaksandr Herasimenka, which is attached at the bottom of this text box.

Case study

Case studies are often a convenient way to narrow the focus of your research by studying how a theory or literature fares with regard to a specific person, group, organisation, event or other type of entity or phenomenon you identify. Case studies can be researched using other methods, including those described in this section. Case studies give in-depth insights on the particular reality that has been examined, but may not be representative of what happens in general, they may not be generalisable, and may not be relevant to other contexts. These limitations have to be acknowledged by the researcher.

Content analysis

Content analysis consists in the study of words or images within a text. In its broad definition, texts include books, articles, essays, historical documents, speeches, conversations, advertising, interviews, social media posts, films, theatre, paintings or other visuals. Content analysis can be quantitative (e.g. word frequency) or qualitative (e.g. analysing intention and implications of the communication). It can detect propaganda, identify intentions of writers, and can see differences in types of communication (Specht, 2019, p146). Check this page on collecting, cleaning and visualising Twitter data.

Extra links and resources:

Research Methods

A clear and comprehensive overview of research methods by Emerald Publishing. It includes: crowdsourcing as a research tool; mixed methods research; case study; discourse analysis; ground theory; repertory grid; ethnographic method and participant observation; interviews; focus group; action research; analysis of qualitative data; survey design; questionnaires; statistics; experiments; empirical research; literature review; secondary data and archival materials; data collection.

Doing your dissertation during the COVID-19 pandemic

Resources providing guidance on doing dissertation research during the pandemic: Online research methods; Secondary data sources; Webinars, conferences and podcasts;

- Virtual Focus Groups Guidance on managing virtual focus groups

5 Minute Methods Videos

The following are a series of useful videos that introduce research methods in five minutes. These resources have been produced by lecturers and students with the University of Westminster's School of Media and Communication.

Case Study Research

Research Ethics

Quantitative Content Analysis

Sequential Analysis

Qualitative Content Analysis

Thematic Analysis

Social Media Research

Mixed Method Research

Procedural Method

In this part, provide an accurate, detailed account of the methods and procedures that were used in the study or the experiment (if applicable!).

Include specifics about participants, sample, materials, design and methods.

If the research involves human subjects, then include a detailed description of who and how many participated along with how the participants were selected.

Describe all materials used for the study, including equipment, written materials and testing instruments.

Identify the study's design and any variables or controls employed.

Write out the steps in the order that they were completed.

Indicate what participants were asked to do, how measurements were taken and any calculations made to raw data collected.

Specify statistical techniques applied to the data to reach your conclusions.

Provide evidence that you incorporated rigor into your research. This is the quality of being thorough and accurate and considers the logic behind your research design.

Highlight any drawbacks that may have limited your ability to conduct your research thoroughly.

You have to provide details to allow others to replicate the experiment and/or verify the data, to test the validity of the research.

Bibliography

Cottrell, S. (2014). Dissertations and project reports: a step by step guide. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lombard, E. (2010). Primary and secondary sources. The Journal of Academic Librarianship , 36(3), 250-253

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2015). Research Methods for Business Students. New York: Pearson Education.

Specht, D. (2019). The Media And Communications Study Skills Student Guide . London: University of Westminster Press.

- << Previous: Introduction & Philosophy

- Next: Ethics >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2022 12:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/methodology-for-dissertations

CONNECT WITH US

Write Your Dissertation Using Only Secondary Research

Writing a dissertation is already difficult to begin with but it can appear to be a daunting challenge when you only have other people’s research as a guide for proving a brand new hypothesis! You might not be familiar with the research or even confident in how to use it but if secondary research is what you’re working with then you’re in luck. It’s actually one of the easiest methods to write about!

Secondary research is research that has already been carried out and collected by someone else. It means you’re using data that’s already out there rather than conducting your own research – this is called primary research. Thankfully secondary will save you time in the long run! Primary research often means spending time finding people and then relying on them for results, something you could do without, especially if you’re in a rush. Read more about the advantages and disadvantages of primary research .

So, where do you find secondary data?

Secondary research is available in many different places and it’s important to explore all areas so you can be sure you’re looking at research you can trust. If you’re just starting your dissertation you might be feeling a little overwhelmed with where to begin but once you’ve got your subject clarified, it’s time to get researching! Some good places to search include:

- Libraries (your own university or others – books and journals are the most popular resources!)

- Government records

- Online databases

- Credible Surveys (this means they need to be from a reputable source)

- Search engines (google scholar for example).

The internet has everything you’ll need but you’ve got to make sure it’s legitimate and published information. It’s also important to check out your student library because it’s likely you’ll have access to a great range of materials right at your fingertips. There’s a strong chance someone before you has looked for the same topic so it’s a great place to start.

What are the two different types of secondary data?

It’s important to know before you start looking that they are actually two different types of secondary research in terms of data, Qualitative and quantitative. You might be looking for one more specifically than the other, or you could use a mix of both. Whichever it is, it’s important to know the difference between them.

- Qualitative data – This is usually descriptive data and can often be received from interviews, questionnaires or observations. This kind of data is usually used to capture the meaning behind something.

- Quantitative data – This relates to quantities meaning numbers. It consists of information that can be measured in numerical data sets.

The type of data you want to be captured in your dissertation will depend on your overarching question – so keep it in mind throughout your search!

Getting started

When you’re getting ready to write your dissertation it’s a good idea to plan out exactly what you’re looking to answer. We recommend splitting this into chapters with subheadings and ensuring that each point you want to discuss has a reliable source to back it up. This is always a good way to find out if you’ve collected enough secondary data to suit your workload. If there’s a part of your plan that’s looking a bit empty, it might be a good idea to do some more research and fill the gap. It’s never a bad thing to have too much research, just as long as you know what to do with it and you’re willing to disregard the less important parts. Just make sure you prioritise the research that backs up your overall point so each section has clarity.

Then it’s time to write your introduction. In your intro, you will want to emphasise what your dissertation aims to cover within your writing and outline your research objectives. You can then follow up with the context around this question and identify why your research is meaningful to a wider audience.

The body of your dissertation

Before you get started on the main chapters of your dissertation, you need to find out what theories relate to your chosen subject and the research that has already been carried out around it.

Literature Reviews

Your literature review will be a summary of any previous research carried out on the topic and should have an intro and conclusion like any other body of the academic text. When writing about this research you want to make sure you are describing, summarising, evaluating and analysing each piece. You shouldn’t just rephrase what the researcher has found but make your own interpretations. This is one crucial way to score some marks. You also want to identify any themes between each piece of research to emphasise their relevancy. This will show that you understand your topic in the context of others, a great way to prove you’ve really done your reading!

Theoretical Frameworks

The theoretical framework in your dissertation will be explaining what you’ve found. It will form your main chapters after your lit review. The most important part is that you use it wisely. Of course, depending on your topic there might be a lot of different theories and you can’t include them all so make sure to select the ones most relevant to your dissertation. When starting on the framework it’s important to detail the key parts to your hypothesis and explain them. This creates a good foundation for what you’re going to discuss and helps readers understand the topic.

To finish off the theoretical framework you want to start suggesting where your research will fit in with those texts in your literature review. You might want to challenge a theory by critiquing it with another or explain how two theories can be combined to make a new outcome. Either way, you must make a clear link between their theories and your own interpretations – remember, this is not opinion based so don’t make a conclusion unless you can link it back to the facts!

Concluding your dissertation

Your conclusion will highlight the outcome of the research you’ve undertaken. You want to make this clear and concise without repeating information you’ve already mentioned in your main body paragraphs. A great way to avoid repetition is to highlight any overarching themes your conclusions have shown

When writing your conclusion it’s important to include the following elements:

- Summary – A summary of what you’ve found overall from your research and the conclusions you have come to as a result.

- Recommendations – Recommendations on what you think the next steps should be. Is there something you would change about this research to improve it or further develop it?

- Show your contribution – It’s important to show how you’ve contributed to the current knowledge on the topic and not just repeated what other researchers have found.

Hopefully, this helps you with your secondary data research for your dissertation! It’s definitely not as hard as it seems, the hardest part will be gathering all of the information in the first place. It may take a while but once you’ve found your flow – it’ll get easier, promise! You may also want to read about the advantages and disadvantages of secondary research .

You may also like

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

- How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- How to Use AI in Essay Writing: Tips, Tools, and FAQs

- Copy Editing Vs Proofreading: What’s The Difference?

- How Much Does It Cost To Write A Thesis? Get Complete Process & Tips

- How Much Do Proofreading Services Cost in 2024? Per Word and Hourly Rates With Charts

- Academic Editing: What It Is and Why It Matters

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

How to do your dissertation secondary research in 4 steps

(Last updated: 12 May 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

If you are reading this guide, it's very likely you may be doing secondary research for your dissertation, rather than primary. If this is indeed you, then here's the good news: secondary research is the easiest type of research! Congratulations!

In a nutshell, secondary research is far more simple. So simple, in fact, that we have been able to explain how to do it completely in just 4 steps (see below). If nothing else, secondary research avoids the all-so-tiring efforts usually involved with primary research. Like recruiting your participants, choosing and preparing your measures, and spending days (or months) collecting your data.

That said, you do still need to know how to do secondary research. Which is what you're here for. So, go make a decent-sized mug of your favourite hot beverage (consider a glass of water , too) then come back and get comfy.

Here's what we'll cover in this guide:

The basics: What's secondary research all about?

Understanding secondary research, advantages of secondary research, disadvantages of secondary research, methods and purposes of secondary research, types of secondary data, sources of secondary data, secondary research process in 4 steps, step 1: develop your research question(s), step 2: identify a secondary data set, step 3: evaluate a secondary data set, step 4: prepare and analyse secondary data.

To answer this question, let’s first recall what we mean by primary research . As you probably already know, primary research is when the researcher collects the data himself or herself. The researcher uses so-called “real-time” data, which means that the data is collected during the course of a specific research project and is under the researcher’s direct control.

In contrast, secondary research involves data that has been collected by somebody else previously. This type of data is called “past data” and is usually accessible via past researchers, government records, and various online and offline resources.

So to recap, secondary research involves re-analysing, interpreting, or reviewing past data. The role of the researcher is always to specify how this past data informs his or her current research.

In contrast to primary research, secondary research is easier, particularly because the researcher is less involved with the actual process of collecting the data. Furthermore, secondary research requires less time and less money (i.e., you don’t need to provide your participants with compensation for participating or pay for any other costs of the research).

| Comparison basis | PRIMARY RESEARCH | SECONDARY RESEARCH |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Involves collecting factual, first-hand data at the time of the research project | Involves the use of data that was collected by somebody else in the past |

| Type of data | Real-time data | Past data |

| Conducted by | The researcher himself/herself | Somebody else |

| Needs | Addresses specific needs of the researcher | May not directly address the researcher’s needs |

| Involvement | Researcher is very involved | Researcher is less involved |

| Completion time | Long | Short |

| Cost | High | Low |

One of the most obvious advantages is that, compared to primary research, secondary research is inexpensive . Primary research usually requires spending a lot of money. For instance, members of the research team should be paid salaries. There are often travel and transportation costs. You may need to pay for office space and equipment, and compensate your participants for taking part. There may be other overhead costs too.

These costs do not exist when doing secondary research. Although researchers may need to purchase secondary data sets, this is always less costly than if the research were to be conducted from scratch.

As an undergraduate or graduate student, your dissertation project won't need to be an expensive endeavour. Thus, it is useful to know that you can further reduce costs, by using freely available secondary data sets.

But this is far from the only consideration.

Most students value another important advantage of secondary research, which is that secondary research saves you time . Primary research usually requires months spent recruiting participants, providing them with questionnaires, interviews, or other measures, cleaning the data set, and analysing the results. With secondary research, you can skip most of these daunting tasks; instead, you merely need to select, prepare, and analyse an existing data set.

Moreover, you probably won’t need a lot of time to obtain your secondary data set, because secondary data is usually easily accessible . In the past, students needed to go to libraries and spend hours trying to find a suitable data set. New technologies make this process much less time-consuming. In most cases, you can find your secondary data through online search engines or by contacting previous researchers via email.

A third important advantage of secondary research is that you can base your project on a large scope of data . If you wanted to obtain a large data set yourself, you would need to dedicate an immense amount of effort. What's more, if you were doing primary research, you would never be able to use longitudinal data in your graduate or undergraduate project, since it would take you years to complete. This is because longitudinal data involves assessing and re-assessing a group of participants over long periods of time.

When using secondary data, however, you have an opportunity to work with immensely large data sets that somebody else has already collected. Thus, you can also deal with longitudinal data, which may allow you to explore trends and changes of phenomena over time.

With secondary research, you are relying not only on a large scope of data, but also on professionally collected data . This is yet another advantage of secondary research. For instance, data that you will use for your secondary research project has been collected by researchers who are likely to have had years of experience in recruiting representative participant samples, designing studies, and using specific measurement tools.

If you had collected this data yourself, your own data set would probably have more flaws, simply because of your lower level of expertise when compared to these professional researchers.

The first such disadvantage is that your secondary data may be, to a greater or lesser extent, inappropriate for your own research purposes. This is simply because you have not collected the data yourself.

When you collect your data personally, you do so with a specific research question in mind. This makes it easy to obtain the relevant information. However, secondary data was always collected for the purposes of fulfilling other researchers’ goals and objectives.

Thus, although secondary data may provide you with a large scope of professionally collected data, this data is unlikely to be fully appropriate to your own research question. There are several reasons for this. For instance, you may be interested in the data of a particular population, in a specific geographic region, and collected during a specific time frame. However, your secondary data may have focused on a slightly different population, may have been collected in a different geographical region, or may have been collected a long time ago.

Apart from being potentially inappropriate for your own research purposes, secondary data could have a different format than you require. For instance, you might have preferred participants’ age to be in the form of a continuous variable (i.e., you want your participants to have indicated their specific age). But the secondary data set may contain a categorical age variable; for example, participants might have indicated an age group they belong to (e.g., 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, etc.). Or another example: A secondary data set may contain too few ethnic categories (e.g., “White” and “Other”), while you would ideally want a wider range of racial categories (e.g., “White”, “Black or African American”, “American Indian”, and “Asian”). Differences such as these mean that secondary data may not be perfectly appropriate for your research.

The above two disadvantages may lead to yet another one: the existing data set may not answer your own research question(s) in an ideal way. As noted above, secondary data was collected with a different research question in mind, and this may limit its application to your own research purpose.

Unfortunately, the list of disadvantages does not end here. An additional weakness of secondary data is that you have a lack of control over the quality of data. All researchers need to establish that their data is reliable and valid. But if the original researchers did not establish the reliability and validity of their data, this may limit its reliability and validity for your research as well. To establish reliability and validity, you are usually advised to critically evaluate how the data was gathered, analysed, and presented.

But here lies the final disadvantage of doing secondary research: original researchers may fail to provide sufficient information on how their research was conducted. You might be faced with a lack of information on recruitment procedures, sample representativeness, data collection methods, employed measurement tools and statistical analyses, and the like. This may require you to take extra steps to obtain such information, if that is possible at all.

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|

| Inexpensive: Conducting secondary research is much cheaper than doing primary research | Inappropriateness: Secondary data may not be fully appropriate for your research purposes |

| Saves time: Secondary research takes much less time than primary research | Wrong format: Secondary data may have a different format than you require |

| Accessibility: Secondary data is usually easily accessible from online sources. | May not answer your research question: Secondary data was collected with a different research question in mind |

| Large scope of data: You can rely on immensely large data sets that somebody else has collected | Lack of control over the quality of data: Secondary data may lack reliability and validity, which is beyond your control |

| Professionally collected data: Secondary data has been collected by researchers with years of experience | Lack of sufficient information: Original authors may not have provided sufficient information on various research aspects |

At this point, we should ask: “What are the methods of secondary research?” and “When do we use each of these methods?” Here, we can differentiate between three methods of secondary research: using a secondary data set in isolation , combining two secondary data sets, and combining secondary and primary data sets. Let’s outline each of these separately, and also explain when to use each of these methods.

Initially, you can use a secondary data set in isolation – that is, without combining it with other data sets. You dig and find a data set that is useful for your research purposes and then base your entire research on that set of data. You do this when you want to re-assess a data set with a different research question in mind.

Let’s illustrate this with a simple example. Suppose that, in your research, you want to investigate whether pregnant women of different nationalities experience different levels of anxiety during different pregnancy stages. Based on the literature, you have formed an idea that nationality may matter in this relationship between pregnancy and anxiety.

If you wanted to test this relationship by collecting the data yourself, you would need to recruit many pregnant women of different nationalities and assess their anxiety levels throughout their pregnancy. It would take you at least a year to complete this research project.

Instead of undertaking this long endeavour, you thus decide to find a secondary data set – one that investigated (for instance) a range of difficulties experienced by pregnant women in a nationwide sample. The original research question that guided this research could have been: “to what extent do pregnant women experience a range of mental health difficulties, including stress, anxiety, mood disorders, and paranoid thoughts?” The original researchers might have outlined women’s nationality, but weren’t particularly interested in investigating the link between women’s nationality and anxiety at different pregnancy stages. You are, therefore, re-assessing their data set with your own research question in mind.

Your research may, however, require you to combine two secondary data sets . You will use this kind of methodology when you want to investigate the relationship between certain variables in two data sets or when you want to compare findings from two past studies.

To take an example: One of your secondary data sets may focus on a target population’s tendency to smoke cigarettes, while the other data set focuses on the same population’s tendency to drink alcohol. In your own research, you may thus be looking at whether there is a correlation between smoking and drinking among this population.

Here is a second example: Your two secondary data sets may focus on the same outcome variable, such as the degree to which people go to Greece for a summer vacation. However, one data set could have been collected in Britain and the other in Germany. By comparing these two data sets, you can investigate which nation tends to visit Greece more.

Finally, your research project may involve combining primary and secondary data . You may decide to do this when you want to obtain existing information that would inform your primary research.

Let’s use another simple example and say that your research project focuses on American versus British people’s attitudes towards racial discrimination. Let’s say that you were able to find a recent study that investigated Americans’ attitudes of these kind, which were assessed with a certain set of measures. However, your search finds no recent studies on Britons’ attitudes. Let’s also say that you live in London and that it would be difficult for you to assess Americans’ attitudes on the topic, but clearly much more straightforward to conduct primary research on British attitudes.

In this case, you can simply reuse the data from the American study and adopt exactly the same measures with your British participants. Your secondary data is being combined with your primary data. Alternatively, you may combine these types of data when the role of your secondary data is to outline descriptive information that supports your research. For instance, if your project is focusing on attitudes towards McDonald’s food, you may want to support your primary research with secondary data that outlines how many people eat McDonald’s in your country of choice.

TABLE 3 summarises particular methods and purposes of secondary research:

| METHOD | PURPOSE |

|---|---|

| Using secondary data set in isolation | Re-assessing a data set with a different research question in mind |

| Combining two secondary data sets | Investigating the relationship between variables in two data sets or comparing findings from two past studies |

| Combining secondary and primary data sets | Obtaining existing information that informs your primary research |

We have already provided above several examples of using quantitative secondary data. This type of data is used when the original study has investigated a population’s tendency to smoke or drink alcohol, the degree to which people from different nationalities go to Greece for their summer vacation, or the degree to which pregnant women experience anxiety.

In all these examples, outcome variables were assessed by questionnaires, and thus the obtained data was numerical.

Quantitative secondary research is much more common than qualitative secondary research. However, this is not to say that you cannot use qualitative secondary data in your research project. This type of secondary data is used when you want the previously-collected information to inform your current research. More specifically, it is used when you want to test the information obtained through qualitative research by implementing a quantitative methodology.

For instance, a past qualitative study might have focused on the reasons why people choose to live on boats. This study might have interviewed some 30 participants and noted the four most important reasons people live on boats: (1) they can lead a transient lifestyle, (2) they have an increased sense of freedom, (3) they feel that they are “world citizens”, and (4) they can more easily visit their family members who live in different locations. In your own research, you can therefore reuse this qualitative data to form a questionnaire, which you then give to a larger population of people who live on boats. This will help you to generalise the previously-obtained qualitative results to a broader population.

Importantly, you can also re-assess a qualitative data set in your research, rather than using it as a basis for your quantitative research. Let’s say that your research focuses on the kind of language that people who live on boats use when describing their transient lifestyles. The original research did not focus on this research question per se – however, you can reuse the information from interviews to “extract” the types of descriptions of a transient lifestyle that were given by participants.

TABLE 4 highlights the two main types of secondary data and their associated purposes:

| TYPES | PURPOSES |

|---|---|

| Quantitative | Both can be used when you want to (a) inform your current research with past data, and (b) re-assess a past data set |

| Qualitative | Both can be used when you want to (a) inform your current research with past data, and (b) re-assess a past data set |

Internal sources of data are those that are internal to the organisation in question. For instance, if you are doing a research project for an organisation (or research institution) where you are an intern, and you want to reuse some of their past data, you would be using internal data sources.

The benefit of using these sources is that they are easily accessible and there is no associated financial cost of obtaining them.

External sources of data, on the other hand, are those that are external to an organisation or a research institution. This type of data has been collected by “somebody else”, in the literal sense of the term. The benefit of external sources of data is that they provide comprehensive data – however, you may sometimes need more effort (or money) to obtain it.

Let’s now focus on different types of internal and external secondary data sources.

There are several types of internal sources. For instance, if your research focuses on an organisation’s profitability, you might use their sales data . Each organisation keeps a track of its sales records, and thus your data may provide information on sales by geographical area, types of customer, product prices, types of product packaging, time of the year, and the like.

Alternatively, you may use an organisation’s financial data . The purpose of using this data could be to conduct a cost-benefit analysis and understand the economic opportunities or outcomes of hiring more people, buying more vehicles, investing in new products, and so on.

Another type of internal data is transport data . Here, you may focus on outlining the safest and most effective transportation routes or vehicles used by an organisation.

Alternatively, you may rely on marketing data , where your goal would be to assess the benefits and outcomes of different marketing operations and strategies.

Some other ideas would be to use customer data to ascertain the ideal type of customer, or to use safety data to explore the degree to which employees comply with an organisation’s safety regulations.

The list of the types of internal sources of secondary data can be extensive; the most important thing to remember is that this data comes from a particular organisation itself, in which you do your research in an internal manner.

The list of external secondary data sources can be just as extensive. One example is the data obtained through government sources . These can include social surveys, health data, agricultural statistics, energy expenditure statistics, population censuses, import/export data, production statistics, and the like. Government agencies tend to conduct a lot of research, therefore covering almost any kind of topic you can think of.

Another external source of secondary data are national and international institutions , including banks, trade unions, universities, health organisations, etc. As with government, such institutions dedicate a lot of effort to conducting up-to-date research, so you simply need to find an organisation that has collected the data on your own topic of interest.

Alternatively, you may obtain your secondary data from trade, business, and professional associations . These usually have data sets on business-related topics and are likely to be willing to provide you with secondary data if they understand the importance of your research. If your research is built on past academic studies, you may also rely on scientific journals as an external data source.

Once you have specified what kind of secondary data you need, you can contact the authors of the original study.

As a final example of a secondary data source, you can rely on data from commercial research organisations. These usually focus their research on media statistics and consumer information, which may be relevant if, for example, your research is within media studies or you are investigating consumer behaviour.

| INTERNAL SOURCES | EXTERNAL SOURCES |

|---|---|

| Definition: Internal to the organisation or research institution where you conduct your research | Definition: External to the organisation or research institution where you conduct your research |

| Examples: • Sales data • Financial data • Transport data • Marketing data • Customer data • Safety data | Examples: |

At this point, you should have a clearer understanding of secondary research in general terms.

Now it may be useful to focus on the actual process of doing secondary research. This next section is organised to introduce you to each step of this process, so that you can rely on this guide while planning your study. At the end of this blog post, in Table 6 , you will find a summary of all the steps of doing secondary research.

For an undergraduate thesis, you are often provided with a specific research question by your supervisor. But for most other types of research, and especially if you are doing your graduate thesis, you need to arrive at a research question yourself.

The first step here is to specify the general research area in which your research will fall. For example, you may be interested in the topic of anxiety during pregnancy, or tourism in Greece, or transient lifestyles. Since we have used these examples previously, it may be useful to rely on them again to illustrate our discussion.

Once you have identified your general topic, your next step consists of reading through existing papers to see whether there is a gap in the literature that your research can fill. At this point, you may discover that previous research has not investigated national differences in the experiences of anxiety during pregnancy, or national differences in a tendency to go to Greece for a summer vacation, or that there is no literature generalising the findings on people’s choice to live on boats.

Having found your topic of interest and identified a gap in the literature, you need to specify your research question. In our three examples, research questions would be specified in the following manner: (1) “Do women of different nationalities experience different levels of anxiety during different stages of pregnancy?”, (2) “Are there any differences in an interest in Greek tourism between Germans and Britons?”, and (3) “Why do people choose to live on boats?”.

It is at this point, after reviewing the literature and specifying your research questions, that you may decide to rely on secondary data. You will do this if you discover that there is past data that would be perfectly reusable in your own research, therefore helping you to answer your research question more thoroughly (and easily).

But how do you discover if there is past data that could be useful for your research? You do this through reviewing the literature on your topic of interest. During this process, you will identify other researchers, organisations, agencies, or research centres that have explored your research topic.

Somewhere there, you may discover a useful secondary data set. You then need to contact the original authors and ask for a permission to use their data. (Note, however, that this happens only if you are relying on external sources of secondary data. If you are doing your research internally (i.e., within a particular organisation), you don’t need to search through the literature for a secondary data set – you can just reuse some past data that was collected within the organisation itself.)

In any case, you need to ensure that a secondary data set is a good fit for your own research question. Once you have established that it is, you need to specify the reasons why you have decided to rely on secondary data.

For instance, your choice to rely on secondary data in the above examples might be as follows: (1) A recent study has focused on a range of mental difficulties experienced by women in a multinational sample and this data can be reused; (2) There is existing data on Germans’ and Britons’ interest in Greek tourism and these data sets can be compared; and (3) There is existing qualitative research on the reasons for choosing to live on boats, and this data can be relied upon to conduct a further quantitative investigation.

Because such disadvantages of secondary data can limit the effectiveness of your research, it is crucial that you evaluate a secondary data set. To ease this process, we outline here a reflective approach that will allow you to evaluate secondary data in a stepwise fashion.

Step 3(a): What was the aim of the original study?

During this step, you also need to pay close attention to any differences in research purposes and research questions between the original study and your own investigation. As we have discussed previously, you will often discover that the original study had a different research question in mind, and it is important for you to specify this difference.

Let’s put this step of identifying the aim of the original study in practice, by referring to our three research examples. The aim of the first research example was to investigate mental difficulties (e.g., stress, anxiety, mood disorders, and paranoid thoughts) in a multinational sample of pregnant women.

How does this aim differ from your research aim? Well, you are seeking to reuse this data set to investigate national differences in anxiety experienced by women during different pregnancy stages. When it comes to the second research example, you are basing your research on two secondary data sets – one that aimed to investigate Germans’ interest in Greek tourism and the other that aimed to investigate Britons’ interest in Greek tourism.

While these two studies focused on particular national populations, the aim of your research is to compare Germans’ and Britons’ tendency to visit Greece for summer vacation. Finally, in our third example, the original research was a qualitative investigation into the reasons for living on boats. Your research question is different, because, although you are seeking to do the same investigation, you wish to do so by using a quantitative methodology.

Importantly, in all three examples, you conclude that secondary data may in fact answer your research question. If you conclude otherwise, it may be wise to find a different secondary data set or to opt for primary research.

Step 3(b): Who has collected the data?

Let’s say that, in our example of research on pregnancy, data was collected by the UK government; that in our example of research on Greek tourism, the data was collected by a travel agency; and that in our example of research on the reasons for choosing to live on boats, the data was collected by researchers from a UK university.

Let’s also say that you have checked the background of these organisations and researchers, and that you have concluded that they all have a sufficiently professional background, except for the travel agency. Given that this agency’s research did not lead to a publication (for instance), and given that not much can be found about the authors of the research, you conclude that the professionalism of this data source remains unclear.

Step 3(c): Which measures were employed?

Original authors should have documented all their sample characteristics, measures, procedures, and protocols. This information can be obtained either in their final research report or through contacting the authors directly.

It is important for you to know what type of data was collected, which measures were used, and whether such measures were reliable and valid (if they were quantitative measures). You also need to make a clear outline of the type of data collected – and especially the data relevant for your research.

Let’s say that, in our first example, researchers have (among other assessed variables) used a demographic measure to note women’s nationalities and have used the State Anxiety Inventory to assess women’s anxiety levels during different pregnancy stages, both of which you conclude are valid and reliable tools. In our second example, the authors might have crafted their own measure to assess interest in Greek tourism, but there may be no established validity and reliability for this measure. And in our third example, the authors have employed semi-structured interviews, which cover the most important reasons for wanting to live on boats.

Step 3(d): When was the data collected?

Ideally, you want your secondary data to have been collected within the last five years. For the sake of our examples, let’s say that all three original studies were conducted within this time-range.

Step 3(e): What methodology was used to collect the data?

We have already noted that you need to evaluate the reliability and validity of employed measures. In addition to this, you need to evaluate how the sample was obtained, whether the sample was large enough, if the sample was representative of the population, if there were any missing responses on employed measures, whether confounders were controlled for, and whether the employed statistical analyses were appropriate. Any drawbacks in the original methodology may limit your own research as well.

For the sake of our examples, let’s say that the study on mental difficulties in pregnant women recruited a representative sample of pregnant women (i.e., they had different nationalities, different economic backgrounds, different education levels, etc.) in maternity wards of seven hospitals; that the sample was large enough (N = 945); that the number of missing values was low; that many confounders were controlled for (e.g., education level, age, presence of partnership, etc.); and that statistical analyses were appropriate (e.g., regression analyses were used).

Let’s further say that our second research example had slightly less sufficient methodology. Although the number of participants in the two samples was high enough (N1 = 453; N2 = 488), the number of missing values was low, and statistical analyses were appropriate (descriptive statistics), the authors failed to report how they recruited their participants and whether they controlled for any confounders.

Let’s say that these authors also failed to provide you with more information via email. Finally, let’s assume that our third research example also had sufficient methodology, with a sufficiently large sample size for a qualitative investigation (N = 30), high sample representativeness (participants with different backgrounds, coming from different boat communities), and sufficient analyses (thematic analysis).

Note that, since this was a qualitative investigation, there is no need to evaluate the number of missing values and the use of confounders.

Step 3(f): Making a final evaluation

We would conclude that the secondary data from our first research example has a high quality. Data was recently collected by professionals, the employed measures were both reliable and valid, and the methodology was more than sufficient. We can be confident that our new research question can be sufficiently answered with the existing data. Thus, the data set for our first example is ideal.

The two secondary data sets from our second research example seem, however, less than ideal. Although we can answer our research questions on the basis of these recent data sets, the data was collected by an unprofessional source, the reliability and validity of the employed measure is uncertain, and the employed methodology has a few notable drawbacks.

Finally, the data from our third example seems sufficient both for answering our research question and in terms of the specific evaluations (data was collected recently by a professional source, semi-structured interviews were well made, and the employed methodology was sufficient).

The final question to ask is: “what can be done if our evaluation reveals the lack of appropriateness of secondary data?”. The answer, unfortunately, is “nothing”. In this instance, you can only note the drawbacks of the original data set, present its limitations, and conclude that your own research may not be sufficiently well grounded.

Your first sub-step here (if you are doing quantitative research) is to outline all variables of interest that you will use in your study. In our first example, you could have at least five variables of interest: (1) women’s nationality, (2) anxiety levels at the beginning of pregnancy, (3) anxiety levels at three months of pregnancy, (4) anxiety levels at six months of pregnancy, and (5) anxiety levels at nine months of pregnancy. In our second example, you will have two variables of interest: (1) participants’ nationality, and (2) the degree of interest in going to Greece for a summer vacation. Once your variables of interest are identified, you need to transfer this data into a new SPSS or Excel file. Remember simply to copy this data into the new file – it is vital that you do not alter it!

Once this is done, you should address missing data (identify and label them) and recode variables if necessary (e.g., giving a value of 1 to German participants and a value of 2 to British participants). You may also need to reverse-score some items, so that higher scores on all items indicate a higher degree of what is being assessed.

Most of the time, you will also need to create new variables – that is, to compute final scores. For instance, in our example of research on anxiety during pregnancy, your data will consist of scores on each item of the State Anxiety Inventory, completed at various times during pregnancy. You will need to calculate final anxiety scores for each time the measure was completed.

Your final step consists of analysing the data. You will always need to decide on the most suitable analysis technique for your secondary data set. In our first research example, you would rely on MANOVA (to see if women of different nationalities experience different stress levels at the beginning, at three months, at six months, and at nine months of pregnancy); and in our second example, you would use an independent samples t-test (to see if interest in Greek tourism differs between Germans and Britons).

The process of preparing and analysing a secondary data set is slightly different if your secondary data is qualitative. In our example on the reasons for living on boats, you would first need to outline all reasons for living on boats, as recognised by the original qualitative research. Then you would need to craft a questionnaire that assesses these reasons in a broader population.

Finally, you would need to analyse the data by employing statistical analyses.

Note that this example combines qualitative and quantitative data. But what if you are reusing qualitative data, as in our previous example of re-coding the interviews from our study to discover the language used when describing transient lifestyles? Here, you would simply need to recode the interviews and conduct a thematic analysis.

| STEPS FOR DOING SECONDARY RESEARCH | EXAMPLE 1: USING SECONDARY DATA IN ISOLATION | EXAMPLE 2: COMBINING TWO SECONDARY DATA SETS | Outline all variables of interest; Transfer data to a new file; Address missing data; Recode variables; Calculate final scores; Analyse the data |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop your research question | Do women of different nationalities experience different levels of anxiety during different stages of pregnancy? | Are there differences in an interest in Greek tourism between Germans and Britons? | Why do people choose to live on boats? |

| 2. Identify a secondary data set | A recent study has focused on a range of mental difficulties experienced by women in a multinational sample and this data can be reused | There is existing data on Germans’ and Britons’ interest in Greek tourism and these data sets can be compared | There is existing qualitative research on the reasons for choosing to live on boats, and this data can be relied upon to conduct a further quantitative investigation |

| 3. Evaluate a secondary data set | |||

| (a) What was the aim of the original study? | To investigate mental difficulties (e.g., stress, anxiety, mood disorders, and paranoid thoughts) in a multinational sample of pregnant women | Study 1: To investigate Germans’ interest in Greek tourism; Study 2: To investigate Britons’ interest in Greek tourism | To conduct a qualitative investigation on reasons for choosing to live on boats |

| (b) Who has collected the data? | UK government (professional source) | Travel agency (uncertain professionalism) | UK university (professional source) |

| (c) Which measures were employed? | Demographic characteristics (nationality) and State Anxiety Inventory (reliable and valid) | Self-crafted measure to assess interest in Greek tourism (reliability and validity not established) | Semi-structured interviews (well-constructed) |

| (d) When was the data collected? | 2015 (not outdated) | 2013 (not outdated) | 2014 (not outdated) |

| (e) What methodology was used to collect the data? | Sample was representative (women from different backgrounds); large sample size (N = 975); low number of missing values; confounders controlled for (e.g., age, education, partnership status); analyses appropriate (regression) | Sample representativeness not reported; sufficient sample sizes (N1 = 453, N2 = 488); low number of missing values; confounders not controlled for; analyses appropriate (descriptive statistics) | Sample was representative (participants of different backgrounds, from different boat communities); sufficient sample size (N = 30); analyses appropriate (thematic analysis) |

| (f) Making a final evaluation | Sufficiently developed data set | Insufficiently developed data set | Sufficiently developed data set |

| 4. Prepare and analyse secondary data | Outline all variables of interest; Transfer data to a new file; Address missing data; Recode variables; Calculate final scores; Analyse the data | Outline all variables of interest; Transfer data to a new file; Address missing data; Recode variables; Calculate final scores; Analyse the data | Outline all reasons for living on boats; Craft a questionnaire that assesses these reasons in a broader population; Analyse the data |

In summary…

^ Jump to top

A complete guide to dissertation primary research

How to write a dissertation proposal

Navigating tutorials with your dissertation supervisor

Planning a dissertation: the dos and don’ts

Dissertation research: how to find dissertation resources

- dissertation help

- dissertation primary research

- dissertation research

- dissertation tips

- study skills

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

- What is Secondary Data? + [Examples, Sources, & Analysis]

- Data Collection

Aside from consulting the primary origin or source, data can also be collected through a third party, a process common with secondary data. It takes advantage of the data collected from previous research and uses it to carry out new research.

Secondary data is one of the two main types of data, where the second type is the primary data. These 2 data types are very useful in research and statistics, but for the sake of this article, we will be restricting our scope to secondary data.

We will study secondary data, its examples, sources, and methods of analysis.

What is Secondary Data?

Secondary data is the data that has already been collected through primary sources and made readily available for researchers to use for their own research. It is a type of data that has already been collected in the past.

A researcher may have collected the data for a particular project, then made it available to be used by another researcher. The data may also have been collected for general use with no specific research purpose like in the case of the national census.

Data classified as secondary for particular research may be said to be primary for another research. This is the case when data is being reused, making it primary data for the first research and secondary data for the second research it is being used for.

Sources of Secondary Data

Sources of secondary data include books, personal sources, journals, newspapers, websitess, government records etc. Secondary data are known to be readily available compared to that of primary data. It requires very little research and needs for manpower to use these sources.

With the advent of electronic media and the internet, secondary data sources have become more easily accessible. Some of these sources are highlighted below.

Books are one of the most traditional ways of collecting data. Today, there are books available for all topics you can think of. When carrying out research, all you have to do is look for a book on the topic being researched, then select from the available repository of books in that area. Books, when carefully chosen are an authentic source of authentic data and can be useful in preparing a literature review.

- Published Sources

There are a variety of published sources available for different research topics. The authenticity of the data generated from these sources depends majorly on the writer and publishing company.

Published sources may be printed or electronic as the case may be. They may be paid or free depending on the writer and publishing company’s decision.

- Unpublished Personal Sources

This may not be readily available and easily accessible compared to the published sources. They only become accessible if the researcher shares with another researcher who is not allowed to share it with a third party.

For example, the product management team of an organization may need data on customer feedback to assess what customers think about their product and improvement suggestions. They will need to collect the data from the customer service department, which primarily collected the data to improve customer service.