Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: http://tlt.its.psu.edu/suggestions/cases/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the University of Buffalo.

Dunne, D. and Brooks, K. (2004) Teaching with Cases (Halifax, NS: Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education), ISBN 0-7703-8924-4 (Can be ordered at http://www.bookstore.uwo.ca/ at a cost of $15.00)

AI Case Writing is here to stay, why not learn how!

Each week I share Ai Case Writing Research, How to and Prompts.

I'd love for you to join - UnSubscribe Anytime

We don’t spam! Read our privacy policy for more info.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Pin It on Pinterest

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Teaching Resources Library

Case studies.

The teaching business case studies available here are narratives that facilitate class discussion about a particular business or management issue. Teaching cases are meant to spur debate among students rather than promote a particular point of view or steer students in a specific direction. Some of the case studies in this collection highlight the decision-making process in a business or management setting. Other cases are descriptive or demonstrative in nature, showcasing something that has happened or is happening in a particular business or management environment. Whether decision-based or demonstrative, case studies give students the chance to be in the shoes of a protagonist. With the help of context and detailed data, students can analyze what they would and would not do in a particular situation, why, and how.

Case Studies By Category

- Case Studies

Teaching Guide

- Using the Open Case Studies Website

- Using the UBC Wiki

- Open Educational Resources

- Case Implementation

- Get Involved

- Process Documentation

Case studies offer a student-centered approach to learning that asks students to identify, explore, and provide solutions to real-world problems by focusing on case-specific examples (Wiek, Xiong, Brundiers, van der Leeuw, 2014, p 434). This approach simulates real life practice in sustainability education in that it illuminates the ongoing complexity of the problems being addressed. Publishing these case studies openly, means they can be re-used in a variety of contexts by others across campus and beyond. Since the cases never “end”; at any time students from all over UBC campus can engage with their content, highlighting their potential as powerful educational tools that can foster inter-disciplinary research of authentic problems. Students contributing to the case studies are making an authentic contribution to a deepening understanding of the complex challenges facing us in terms of environmental ethics and sustainability.

The case studies are housed on the UBC Wiki, and that content is then fed into the Open Case Studies website. The UBC Wiki as a platform for open, collaborative course work enables students to create, respond to and/or edit case studies, using the built in features (such as talk pages, document history and contributor track backs) to make editing transparent. The wiki also also helps students develop important transferable skills such as selection and curation of multimedia (while attending to copyright and re-use specifications), citation and referencing, summarizing research, etc. These activities help build critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and digital literacy.

This guide is intended to help you get started with your case study project by offering:

- Information on how to use the UBC Wiki

- Research that supports case studies as effective tools for active learning

- Instructional strategies for teaching effectively with case studies

- Sample case study assignments used by UBC instructors

The UBC Wiki is a set of webpages accessible to anyone with a CWL account and has many unique features in addition to collaborative writing including the ability to revive previous drafts, and notifications setting that can support instructors in monitoring individual student contributions, or support students to better manage their collaborative efforts on their own. Using a wiki successfully in a course, however, requires proper facilitation and support from instructors and TAs.

The following links are helpful in getting started:

General Information:

- Navigating the Wiki: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Help:Navigation

- Wiki Help Table of Contents: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Help:Contents

- Frequently Asked Questions: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Help:Contents#Frequently_Asked_Questions

Self-Guided Wiki Tutorials:

- Getting Started With UBC Wiki - short video and links to common formatting needs.

- Beginner: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Documentation:MediaWiki_Basics/Learning_Activities/Beginner

- Intermediate: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Documentation:MediaWiki_Basics/Learning_Activities/Intermediate

- Advanced: http://wiki.ubc.ca/Documentation:MediaWiki_Basics/Learning_Activities/Advanced

The idea that learning is "active" is influenced by social constructivism , which emphasizes collaboration in the active co-construction of meaning among learners. Simply put, learning happens when people collaborate and interact with authentic learning tasks and situations. These ideas are becoming increasingly prevalent in the scholarly literature on teaching and learning (see for instance, Wilson 1996) and have important implications for pedagogy, especially in the university where traditional lectures remain the dominant instructional strategy. When students are asked to respond to authentic problems and questions, they assume responsibility for the trajectory of their learning, rather than it being decided upon by the instructor. This practice, also referred to as “student-centered learning” allows the students to become “active” participants in the construction of their understandings.

One of the easiest ways to develop higher order cognitive capacities (critical thinking, problem solving, creativity etc.) is through pedagogies that support inquiry based learning, thereby allowing students the opportunity to “develop [as] inquirers and to use curiosity, the urge to explore and understand...to become researchers and lifelong learners” (Justice, Rice, Roy, Hudspith & Jenkins,2009, p. 843). Because case studies are often collaborative, they provide unique inquiry based learning opportunities that will foster active engagement in student learning, while also teaching transferable skills (teamwork, collaboration, technology literacy). That the cases never “end” and that they can be considered by students and faculty from all over the UBC community, highlights their potential as powerful educational tools that can foster inter-disciplinary research of authentic problems.

Using case studies successfully in a course requires purposefully scaffolded support from the instructor and TA's. Instructors must properly introduce assignments, as well as facilitate and monitor the progress of students while they work on assignments. This will help ensure that students understand the purpose and value of the work they are doing and will also allow instructors and TA's to provide appropriate support and guidance.

The following instructional strategies will help you teach effectively using case studies:

1. Getting Started:

- Outline Your "Big Picture" Goals and Expectations : Communicate to students what you are hoping they will learn (Or have them tell you why they think you would ask them to work with case studies!). It is also important to discuss the quality of work you expect and offer specific examples of what that looks like. If you have any, look at exemplars of past student work, or simply evaluate existing case studies to generate a list of defining characteristics. Doing this will provide students with valuable tangible and visual examples of what you expect.

- Define "Case Study" : Don't assume that students understand what case-studies are, especially at the undergraduate level. Take the time to talk about what a case study is and why they are powerful teaching/learning tools. This can be facilitated during a tutorial with small group discussion. See Case Study Resources.

- Pick Case Studies Purposefully : If you are planning on having students evaluate case studies, make sure to read them in advance and have a clear understanding of why you chose it. This will help facilitate discussion and field student questions.

- Set the Context for the Evaluating or Creating the Case Study : Whether you are having students write the case studies themselves, or you are having them examine an existing case, it is important to set the parameters for how you want students to approach the problem. For instance, you may have them evaluate the case from the perspective of an industry professional, a community group or member, or even from their own perspective of university students. Whatever you choose, make sure you communicate this clearly.

- Set the Parameters for Evaluating or Creating the Case Study : Clearly outline all the information you want students to find out, and how you want it reported. You may want students to focus on some areas and disregard others, or you may want them to consider all the facts equally. Whatever you choose, make sure you communicate this clearly.

2. Use, Revise, and/or Create

- Use the case studies as they are : One way to use the case studies in courses is to have students read and discuss them as they are. They can be read on the open case studies website, downloaded from the wiki and embedded into another website, or downloaded in PDF or Microsoft Word format (see this guide for how to embed or download the case studies)

- If you are only making minor edits such as fixing a broken link or a typo, please go ahead. You could add a note about this to the "discussion" page to explain (see the tab at the top of each wiki page).

- You could add a section at the bottom of the case study with a perspective on it from your discipline. Some of the case studies already have sections at the bottom that are titled "What would a ___ do?" You can add a new one of those to give a different disciplinary perspective.

- If you want to make more substantial changes, it would be best if you copied and pasted the wiki content into a new page so as to preserve the original. The original version may be used in other courses by the instructor/students who created it, so making significant changes could be a problem! And those changes might be reverted by the original instructor and students (wiki pages keep all past versions, and those changes can easily be reverted). If you would like to substantially revise a case study, please contact Christina Hendricks, who can help you get started and then get the new version into the collection: [email protected]

- Create new case studies : We are always looking for new case studies for the collection! If you think you would like to write one, or involve your students in writing one, please contact Christina Hendricks: [email protected]

3. Guiding Case Study Discussions:

- Ask open-ended questions : Open-ended questions cannot be answered using "yes" or "no". Be careful when wording discussion questions, allowing them to be as open as possible.

- Listen Actively : Actively listen to students by paraphrasing what they have said to you and saying it back (e.g. "What I heard is....Is this what you meant?"). This will help you pay close attention to what they say and clarify any possible miscommunication.

- Role Play : Ask students to take on the perspective of different interested parties in considering the case study.

- Compare and Contrast : Ask students to compare and contrast cases in similar areas from the open case study collection. Discuss whether there are similar problems or possible solutions for the cases.

4. Staying on Track:

- Develop a Protocol for Collaboration : Have students outline how they will collaborate at the start of the assignment to ensure that the work is shared evenly and that each student has a purposeful role.

- Set Benchmark Assignments : Make sure students stay on track by requiring smaller assignments or assessments along the way. This can be as simple as coming to tutorial with a portion of the case-study written for peer critique and analysis.

- Give Students Adequate Time : Allow students enough time to read and consider case-studies thoughtfully. The more time you can provide, the less overwhelmed students will feel. This will encourage them to go deeper with their case study and their learning.

- Forestry : In this assignment, students in a graduate course wrote their own case studies. This link provides information on the assignment, a handout given to the students, and a grading rubric: Short-Term Assignment: What is Illegal Logging? - Teacher Guide

- Political Science : Students in a third-year political science class responded to a case study written by the instructor. They worked in groups to create action plans for climate change problems. This link provides information on the assignment as well as a handout given to the students: Class Activity: Action Plans for Climate Change - Teacher Guide

- Education : Teacher candidates in the Faculty of Education respond to case studies written by students. They discuss a case study and respond to questions with the goal of identifying the issues raised, perspectives involved and possible ways forward. The goal is to support decision making related to online presence and social media engagement. Digital Tattoo Case Studies for Student Teachers Facilitators' Guide

Case Studies

Real instructional framework case studies and teacher effectiveness examples and stories from our partners.

School Leadership Case Study: Implementing Effective Teacher Feedback to Exceed Growth Goals

When Zach Marks first transitioned from elementary to middle school principal, he walked into a complex post-COVID environment. Deciding what to tackle first should’ve been a challenge, but Zach looked at the data and identified almost immediately what he wanted to address: instructional improvement.

As a new principal in the building, Zack Marks, knew he needed to ensure teachers felt safe. Because of the changes COVID brought on, there were many new teachers in the school who were beginning new careers. He wanted to provide simple and intentional feedback to new teachers to help them grow. With his veteran teachers, he wanted to identify simple tweaks they could make, and to instill a culture of constant improvement in the school overall.

Accelerate Learning for Students: A Case Study on Previewing

Accelerate or Remediate?

While often debated in the educational world, the data-backed answer for a North Carolina school district is clear.

Accelerate!

Catawba County Schools is the largest school district in Catawba County, North Carolina. Like many districts, they knew some students struggled to meet proficiency levels, particularly in mathematics. Traditional remediation methods were not yielding the desired results, and there was a need for an innovative approach to address performance and boost student confidence.

Literacy Framework Pays off Big for North Carolina Middle School

Learning-Focused was hired as a literacy consultant to Hawfields Middle School after the principal attended a literacy strategies workshop and found himself nodding along with the framework insights presented. He created a literacy wishlist, met with the team, hired Learning-Focused , and achieved extraordinary results.

Charity Barton - First-Time Principal With High Expectations

As a first-time principal, Charity Brown brought high expectations and was ready to do the necessary work when she brought in Learning-Focused . Learn how Miss Barton used the Learning-Focused framework and led her school to become a Title I Distinguished School, improve student behavior, and support teachers—all in the midst of COVID.

Dr. Anna DeWese - A Turnaround Principal

Dr. Anna DeWese is a veteran principal in Florida with a reputation for outstanding support and commitment to students. Learn how Dr. DeWese has effectively implemented the Learning-Focused Instructional Framework in every school she has served in as principal for the last ten years.

Tunkhannock Area School District

Learn how Tunkhannock Area School District utilized their Mapped Curriculum to build their Online Curriculum,

Weems Elementary School

Learn how Weems Elementary School closed the achievement gap 10-15% over the state average by focusing on improving instruction for all students, over half of who are English Language Learners (ELLs).

W.D. Sugg Middle School

Learn how W.D. Sugg Middle School increased student achievement by targeting High Yield Strategies and building instructional capacity to make achievement gains.

- International

- Business & Industry

- MyUNB Intranet

- Activate your IT Services

- Give to UNB

- Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning

- Teaching & Learning Services

- Teaching Tips

- Instructional Methods

- Creating Effective Scenarios, Case Studies and Role Plays

Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays

Printable Version (PDF)

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course. See Research Findings on University Teaching Methods .

Typically you would use case studies, scenarios and role plays for higher-level learning outcomes that require application, synthesis, and evaluation (see Writing Outcomes or Learning Objectives ; scroll down to the table).

The point is to increase student interest and involvement, and have them practice application by making choices and receive feedback on them, and refine their understanding of concepts and practice in your discipline.

These types of activities provide the following research-based benefits: (Shaw, 3-5)

- They provide concrete examples of abstract concepts, facilitate the development through practice of analytical skills, procedural experience, and decision making skills through application of course concepts in real life situations. This can result in deep learning and the appreciation of differing perspectives.

- They can result in changed perspectives, increased empathy for others, greater insights into challenges faced by others, and increased civic engagement.

- They tend to increase student motivation and interest, as evidenced by increased rates of attendance, completion of assigned readings, and time spent on course work outside of class time.

- Studies show greater/longer retention of learned materials.

- The result is often better teacher/student relations and a more relaxed environment in which the natural exchange of ideas can take place. Students come to see the instructor in a more positive light.

- They often result in better understanding of complexity of situations. They provide a good forum for a large volume of orderly written analysis and discussion.

There are benefits for instructors as well, such as keeping things fresh and interesting in courses they teach repeatedly; providing good feedback on what students are getting and not getting; and helping in standing and promotion in institutions that value teaching and learning.

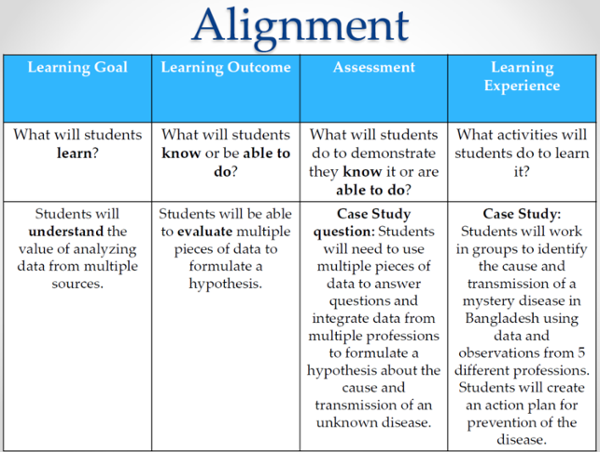

Outcomes and learning activity alignment

The learning activity should have a clear, specific skills and/or knowledge development purpose that is evident to both instructor and students. Students benefit from knowing the purpose of the exercise, learning outcomes it strives to achieve, and evaluation methods. The example shown in the table below is for a case study, but the focus on demonstration of what students will know and can do, and the alignment with appropriate learning activities to achieve those abilities applies to other learning activities.

(Smith, 18)

What’s the difference?

Scenarios are typically short and used to illustrate or apply one main concept. The point is to reinforce concepts and skills as they are taught by providing opportunity to apply them. Scenarios can also be more elaborate, with decision points and further scenario elaboration (multiple storylines), depending on responses. CETL has experience developing scenarios with multiple decision points and branching storylines with UNB faculty using PowerPoint and online educational software.

Case studies

Case studies are typically used to apply several problem-solving concepts and skills to a detailed situation with lots of supporting documentation and data. A case study is usually more complex and detailed than a scenario. It often involves a real-life, well documented situation and the students’ solutions are compared to what was done in the actual case. It generally includes dialogue, creates identification or empathy with the main characters, depending on the discipline. They are best if the situations are recent, relevant to students, have a problem or dilemma to solve, and involve principles that apply broadly.

Role plays can be short like scenarios or longer and more complex, like case studies, but without a lot of the documentation. The idea is to enable students to experience what it may be like to see a problem or issue from many different perspectives as they assume a role they may not typically take, and see others do the same.

Foundational considerations

Typically, scenarios, case studies and role plays should focus on real problems, appropriate to the discipline and course level.

They can be “well-structured” or “ill-structured”:

- Well-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can be simple or complex or anything in-between, but they have an optimal solution and only relevant information is given, and it is usually labelled or otherwise easily identified.

- Ill-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can also be simple or complex, although they tend to be complex. They have relevant and irrelevant information in them, and part of the student’s job is to decide what is relevant, how it is relevant, and to devise an evidence-based solution to the problem that is appropriate to the context and that can be defended by argumentation that draws upon the student’s knowledge of concepts in the discipline.

Well-structured problems would be used to demonstrate understanding and application. Higher learning levels of analysis, synthesis and evaluation are better demonstrated by ill-structured problems.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be authentic or realistic :

- Authentic scenarios are actual events that occurred, usually with personal details altered to maintain anonymity. Since the events actually happened, we know that solutions are grounded in reality, not a fictionalized or idealized or simplified situation. This makes them “low transference” in that, since we are dealing with the real world (although in a low-stakes, training situation, often with much more time to resolve the situation than in real life, and just the one thing to work on at a time), not much after-training adjustment to the real world is necessary.

- By contrast, realistic scenarios are often hypothetical situations that may combine aspects of several real-world events, but are artificial in that they are fictionalized and often contain ideal or simplified elements that exist differently in the real world, and some complications are missing. This often means they are easier to solve than real-life issues, and thus are “high transference” in that some after-training adjustment is necessary to deal with the vagaries and complexities of the real world.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be high or low fidelity :

High vs. low fidelity: Fidelity has to do with how much a scenario, case study or role play is like its corresponding real world situation. Simplified, well-structured scenarios or problems are most appropriate for beginners. These are low-fidelity, lacking a lot of the detail that must be struggled with in actual practice. As students gain experience and deeper knowledge, the level of complexity and correspondence to real-world situations can be increased until they can solve high fidelity, ill-structured problems and scenarios.

Further details for each

Scenarios can be used in a very wide range of learning and assessment activities. Use in class exercises, seminars, as a content presentation method, exam (e.g., tell students the exam will have four case studies and they have to choose two—this encourages deep studying). Scenarios help instructors reflect on what they are trying to achieve, and modify teaching practice.

For detailed working examples of all types, see pages 7 – 25 of the Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS) pdf .

The contents of case studies should: (Norton, 6)

- Connect with students’ prior knowledge and help build on it.

- Be presented in a real world context that could plausibly be something they would do in the discipline as a practitioner (e.g., be “authentic”).

- Provide some structure and direction but not too much, since self-directed learning is the goal. They should contain sufficient detail to make the issues clear, but with enough things left not detailed that students have to make assumptions before proceeding (or explore assumptions to determine which are the best to make). “Be ambiguous enough to force them to provide additional factors that influence their approach” (Norton, 6).

- Should have sufficient cues to encourage students to search for explanations but not so many that a lot of time is spent separating relevant and irrelevant cues. Also, too many storyline changes create unnecessary complexity that makes it unnecessarily difficult to deal with.

- Be interesting and engaging and relevant but focus on the mundane, not the bizarre or exceptional (we want to develop skills that will typically be of use in the discipline, not for exceptional circumstances only). Students will relate to case studies more if the depicted situation connects to personal experiences they’ve had.

- Help students fill in knowledge gaps.

Role plays generally have three types of participants: players, observers, and facilitator(s). They also have three phases, as indicated below:

Briefing phase: This stage provides the warm-up, explanations, and asks participants for input on role play scenario. The role play should be somewhat flexible and customizable to the audience. Good role descriptions are sufficiently detailed to let the average person assume the role but not so detailed that there are so many things to remember that it becomes cumbersome. After role assignments, let participants chat a bit about the scenarios and their roles and ask questions. In assigning roles, consider avoiding having visible minorities playing “bad guy” roles. Ensure everyone is comfortable in their role; encourage students to play it up and even overact their role in order to make the point.

Play phase: The facilitator makes seating arrangements (for players and observers), sets up props, arranges any tech support necessary, and does a short introduction. Players play roles, and the facilitator keeps things running smoothly by interjecting directions, descriptions, comments, and encouraging the participation of all roles until players keep things moving without intervention, then withdraws. The facilitator provides a conclusion if one does not arise naturally from the interaction.

Debriefing phase: Role players talk about their experience to the class, facilitated by the instructor or appointee who draws out the main points. All players should describe how they felt and receive feedback from students and the instructor. If the role play involved heated interaction, the debriefing must reconcile any harsh feelings that may otherwise persist due to the exercise.

Five Cs of role playing (AOM, 3)

Control: Role plays often take on a life of their own that moves them in directions other than those intended. Rehearse in your mind a few possible ways this could happen and prepare possible intervention strategies. Perhaps for the first role play you can play a minor role to give you and “in” to exert some control if needed. Once the class has done a few role plays, getting off track becomes less likely. Be sensitive to the possibility that students from different cultures may respond in unforeseen ways to role plays. Perhaps ask students from diverse backgrounds privately in advance for advice on such matters. Perhaps some of these students can assist you as co-moderators or observers.

Controversy: Explain to students that they need to prepare for situations that may provoke them or upset them, and they need to keep their cool and think. Reiterate the learning goals and explain that using this method is worth using because it draws in students more deeply and helps them to feel, not just think, which makes the learning more memorable and more likely to be accessible later. Set up a “safety code word” that students may use at any time to stop the role play and take a break.

Command of details: Students who are more deeply involved may have many more detailed and persistent questions which will require that you have a lot of additional detail about the situation and characters. They may also question the value of role plays as a teaching method, so be prepared with pithy explanations.

Can you help? Students may be concerned about how their acting will affect their grade, and want assistance in determining how to play their assigned character and need time to get into their role. Tell them they will not be marked on their acting. Say there is no single correct way to play a character. Prepare for slow starts, gaps in the action, and awkward moments. If someone really doesn’t want to take a role, let them participate by other means—as a recorder, moderator, technical support, observer, props…

Considered reflection: Reflection and discussion are the main ways of learning from role plays. Players should reflect on what they felt, perceived, and learned from the session. Review the key events of the role play and consider what people would do differently and why. Include reflections of observers. Facilitate the discussion, but don’t impose your opinions, and play a neutral, background role. Be prepared to start with some of your own feedback if discussion is slow to start.

An engineering role play adaptation

Boundary objects (e.g., storyboards) have been used in engineering and computer science design projects to facilitate collaboration between specialists from different disciplines (Diaz, 6-80). In one instance, role play was used in a collaborative design workshop as a way of making computer scientist or engineering students play project roles they are not accustomed to thinking about, such as project manager, designer, user design specialist, etc. (Diaz 6-81).

References:

Academy of Management. (Undated). Developing a Role playing Case Study as a Teaching Tool.

Diaz, L., Reunanen, M., & Salimi, A. (2009, August). Role Playing and Collaborative Scenario Design Development. Paper presented at the International Conference of Engineering Design, Stanford University, California.

Norton, L. (2004). Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS): A practical introduction to problem-based learning using vignettes for psychology lecturers . Liverpool Hope University College.

Shaw, C. M. (2010). Designing and Using Simulations and Role-Play Exercises in The International Studies Encyclopedia, eISBN: 9781444336597

Smith, A. R. & Evanstone, A. (Undated). Writing Effective Case Studies in the Sciences: Backward Design and Global Learning Outcomes. Institute for Biological Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Campus Maps

- Campus Security

- Careers at UNB

- Services at UNB

- Conference Services

- Online & Continuing Ed

Contact UNB

- © University of New Brunswick

- Accessibility

- Web feedback

- Case Teaching Resources

Teaching With Cases

Included here are resources to learn more about case method and teaching with cases.

What Is A Teaching Case?

This video explores the definition of a teaching case and introduces the rationale for using case method.

Narrated by Carolyn Wood, former director of the HKS Case Program

Learning by the Case Method

Questions for class discussion, common case teaching challenges and possible solutions, teaching with cases tip sheet, teaching ethics by the case method.

The case method is an effective way to increase student engagement and challenge students to integrate and apply skills to real-world problems. In these videos, Using the Case Method to Teach Public Policy , you'll find invaluable insights into the art of case teaching from one of HKS’s most respected professors, Jose A. Gomez-Ibanez.

Chapter 1: Preparing for Class (2:29)

Chapter 2: How to begin the class and structure the discussion blocks (1:37)

Chapter 3: How to launch the discussion (1:36)

Chapter 4: Tools to manage the class discussion (2:23)

Chapter 5: Encouraging participation and acknowledging students' comments (1:52)

Chapter 6: Transitioning from one block to the next / Importance of body (2:05)

Chapter 7: Using the board plan to feed the discussion (3:33)

Chapter 8: Exploring the richness of the case (1:42)

Chapter 9: The wrap-up. Why teach cases? (2:49)

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Instructional Materials

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

NCCSTS Case Collection

- Science and STEM Education Jobs

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Case Study Listserv

Permissions & Guidelines

Submit a Case Study

Resources & Publications

Enrich your students’ educational experience with case-based teaching

The NCCSTS Case Collection, created and curated by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, on behalf of the University at Buffalo, contains over a thousand peer-reviewed case studies on a variety of topics in all areas of science.

Cases (only) are freely accessible; subscription is required for access to teaching notes and answer keys.

Subscribe Today

Browse Case Studies

Latest Case Studies

Development of the NCCSTS Case Collection was originally funded by major grants to the University at Buffalo from the National Science Foundation , The Pew Charitable Trusts , and the U.S. Department of Education .

- Utility Menu

ff79ef2fa7dffef14d5b27c4d8e7b38c

- Submit A Case

Complete List of Case Studies

|

A teacher grapples with when corporal punishment crosses the line into child abuse and whether or not reporting her suspicions is the right decision in either case. |

A student in a conservative school district appears to be experimenting with their gender identity. Can the needs of the child be balanced against prevailing community norms? Should they? |

A group of teachers and administrators grapple with how to discipline a student who posted a nasty meme on a classmates social media feed. Should sharing a violent meme be treated differently than other violent speech? |

|

After a student approaches her with a sexual health question, a health educator must decide whether or not to answer the student's question against the wishes of her parents. |

Towards the end of her Masters in Teaching, a preservice teacher grapples with whether or not to accept a job offer to teach at an urban charter school and discusses what it means to teach for social justice with a group of her colleagues. |

While planning for their Power of Persuasion project, the Northern High 10th Grade social studies team debates what topics are appropriately controversial for school and what topics endanger safe and inclusive classroom spaces. |

|

The School Culture Committee at a K-8 school in Jersey City struggles with the impact of divisive political rhetoric on their classroom and school community. |

This case explores the dilemmas that emerge when students in Portland, Oregon walk out of school to protest the election of Donald Trump. |

Teachers wrestle with how to teach the controversial issues and topics raised during the 2016 election. |

|

Teachers debate whether or not to promote an eighth grader who has made great strides academically in the face of numerous personal struggles, but who is also failing multiple courses and reading well below grade-level. |

How should a teacher balance the needs of a disruptive student against the needs of the other 26 students in the class? |

In designing a new school assignment plan, is it ethical to pander to middle class families’ preferences so as to draw them, and their social and economic capital, into the public system? |

|

Should teachers allow a religious student to pursue a citizenship project that argues against gay marriage? |

How should a school maintain professional integrity with respect to their grading policy against, while balancing commitments to student learning, student success in college admissions, and school success in the private school marketplace? |

For months, college students who run an after-school program have struggled to manage the challenging behaviors of a child with disabilities. As volunteers with no special education credentials and little training, can and should they continue to work with this student? |

|

This case probes the ethical challenges that admissions officers at elite schools face in the age of social media. Should all of a young person's online history be open for scrutiny? How should admissions officers acknowledge that students are in the process of development? |

A school principal is asked to respond to growing numbers of parents opting their children out of state tests. How should she balance these parents’ concerns with other parent viewpoints supporting assessment, her own professional obligations, as well as with district and state accountability pressures? |

|

Search for a Case

- Assessment (6)

- Civics (14)

- College (3)

- Curriculum (13)

- Democracy (3)

- District Leaders (7)

- Elementary School (5)

- High School (11)

- International (9)

- Middle School (5)

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

| Type of Case | Description | Promoted Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Directed case | Presents a scenario that is followed by discussion using a set of “directed” / close-ended questions that can be answered from course material. | Understanding of fundamental concepts, principles, and facts |

| Dilemma or decision case | Presents an individual, institution, or community faced with a problem that must be solved. Students may be presented with actual historical outcomes after they work through the case. | Problem solving and decision-making skills |

| Interrupted case | Presents a problem for students to solve in a progressive disclosure format. Students are given the case in parts that they work on and make decisions about before moving on to the next part. | Problem solving skills |

| Analysis or issue case | Focuses on answering questions and analyzing the situation presented. This can include “retrospective” cases that tell a story and its outcomes and have students analyze what happened and why alternative solutions were not taken. | Analysis skills |

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

| Strategy | Role of the Instructor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debate or Trial | Develop critical thinking skills and encourage students to challenge their existing assumptions. | Structure (with guidelines) and facilitate a debate between two diametrically opposed views. Keep time and ask students to reflect on their experience. | Prepare to argue either side. Work in teams to develop and present arguments, and debrief the debate. | Work in teams and prepare an argument for conflicting sides of an issue. |

| Role play or Public Hearing | Understand diverse points of view, promote creative thinking, and develop empathy. | Structure the role-play and facilitate the debrief. At the close of the activity, ask students to reflect on what they learned. | Play a role found in a case, understand the points of view of stakeholders involved. | Describe the points of view of every stakeholder involved. |

| Jigsaw | Promote peer-to-peer learning, and get students to own their learning. | Form student groups, assign each group a piece of the case to study. Form new groups with an “expert” for each previous group. Facilitate a debrief. | Be responsible for learning and then teaching case material to peers. Develop expertise for part of the problem. | Facilitate case method materials for their peers. |

| “Clicker case” / (ARS) | Gauge your students’ learning; get all students to respond to questions, and launch or enhance a case discussion. | Instructor presents a case in stages, punctuated with questions in Poll Everywhere that students respond to using a mobile device. | Respond to questions using a mobile device. Reflect on why they responded the way they did and discuss with peers seated next to them. | Articulate their understanding of a case components. |

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩