Social Impact Theory In Psychology

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Bibb Latané created social impact theory in 1981, and he is also credited as one of the psychologists who brought the bystander effect to light.

Latané’s theory suggests that we are greatly influenced by the actions of others. We can be persuaded, inhibited, threatened, and supported by others.

Latané’s theory proposes that individuals can be the sources or targets of social influence . Social impact theory is a model that conceives of other people’s influence as the result of social forces acting on the individual.

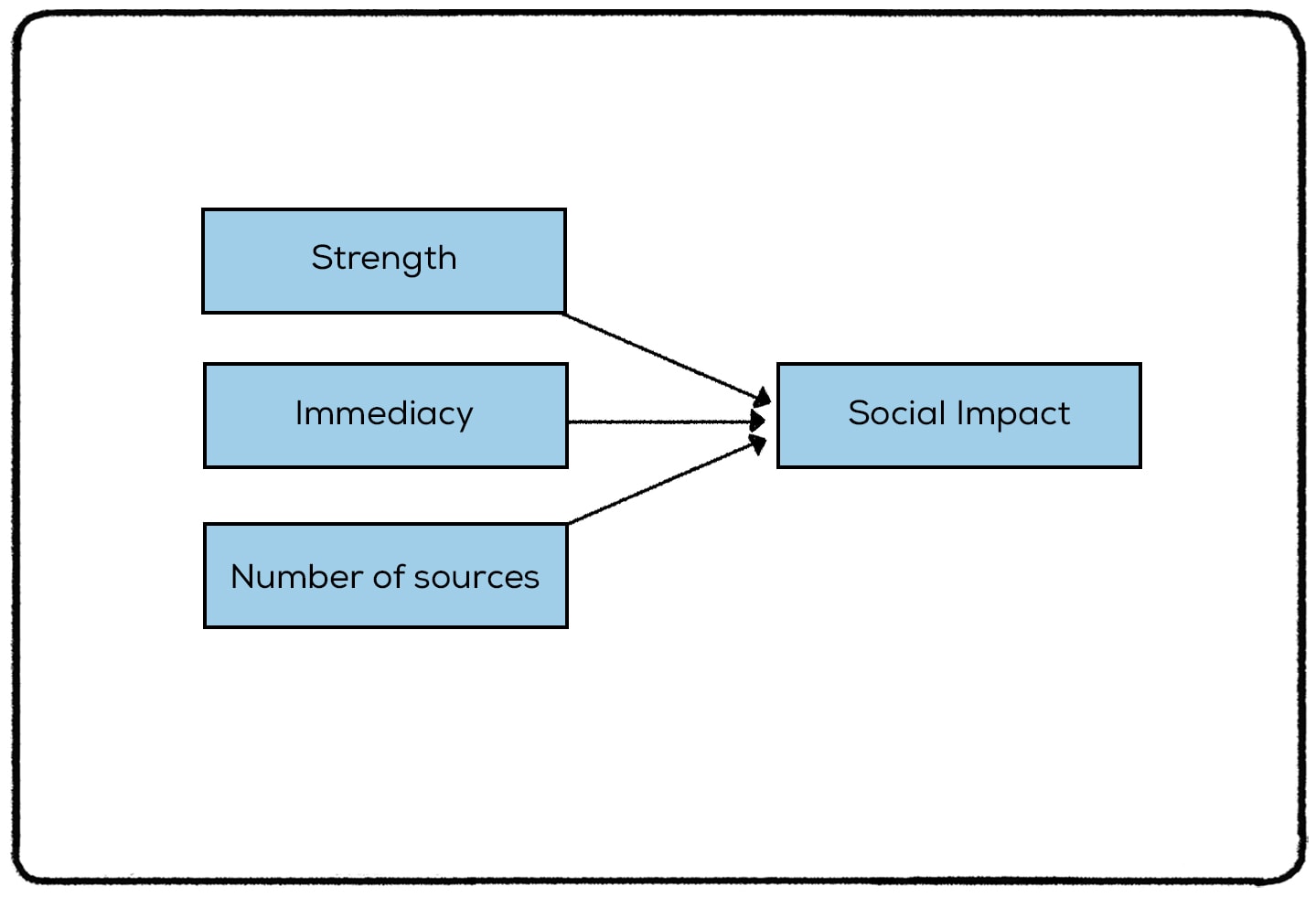

The likelihood that someone will respond to social influence is thought to increase with the source’s strength, the event’s immediacy, and the number of sources exerting the impact.

What is a division of impact?

A division of impact means that the social impact gets spread out between all the people it is directed at. If all the influence is targeted at a single individual, this puts a huge pressure on them to conform or obey.

However, if the influence is directed at two people, the influence is halved.

The more targets there are, the more pressure is shared. This idea is known as diffusion of responsibility. This can explain how the bystander effect can occur in a situation where one person needs help, and a group of people can watch and not feel responsible for helping, compared to if they were the only other person present.

Social Impact Theory’s Three Variables

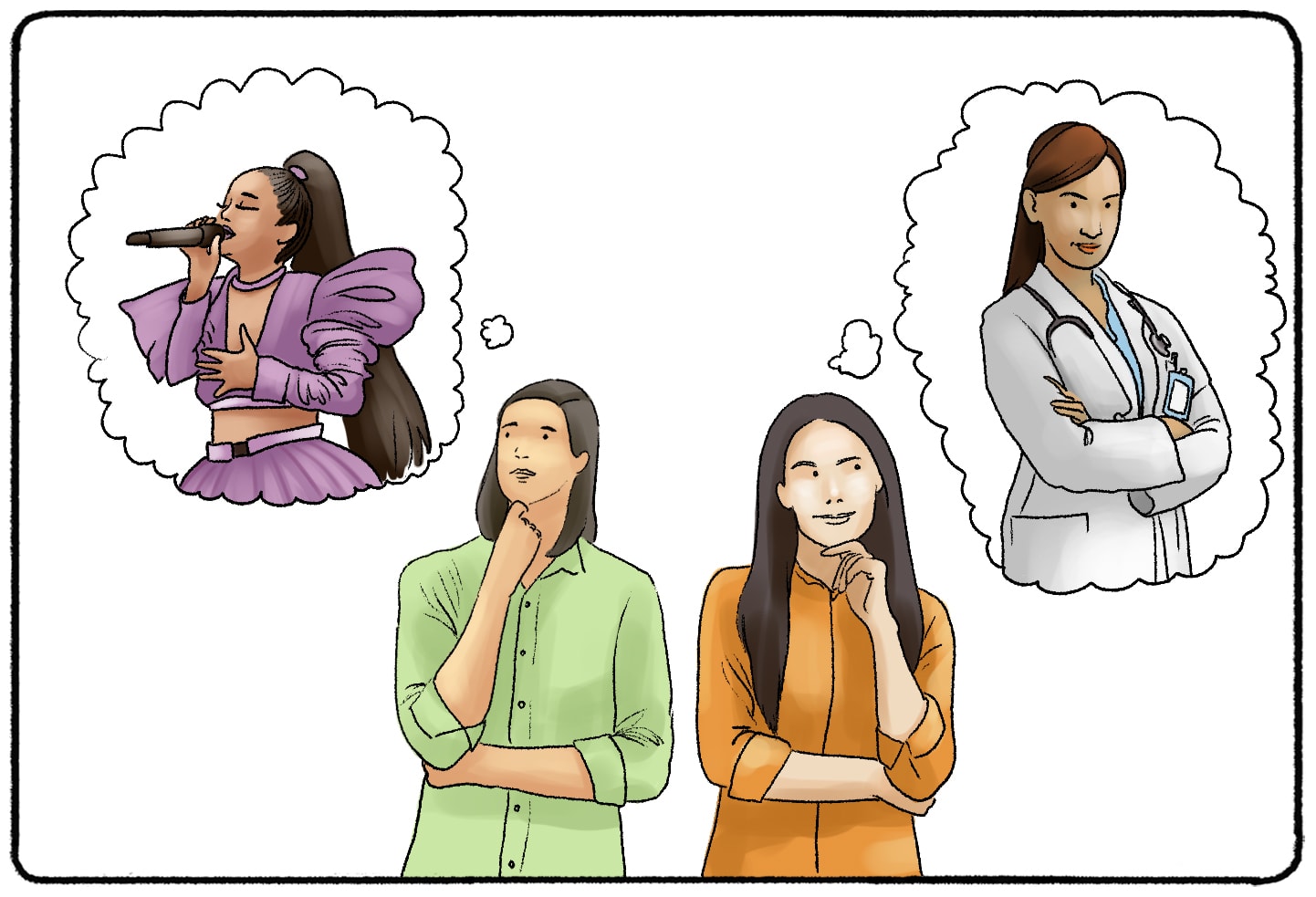

This is how important influencing an individual or group of people is to the person. There are thought to be two categories of strength that determine a source’s impact:

Trans-situational strength – this exists no matter what the situation is, including the source’s age, physical appearance, authority, and perceived intelligence.

Situation-specific – this looks closer at the situation at hand and the behavior that the target is being asked to perform.

For instance, you may be more likely to listen to a doctor when seeking medical advice but may be less likely to take on their interior design advice.

Someone is more likely to influence another if they are close to each other at the time of the influence attempt. There are three types of immediacy:

Physical immediacy – how physically close the source is to a target.

Temporal immediacy – a target is more likely to be influenced immediately after a source has asked them to do so.

Social immediacy – if the source is close friends or family members with the target, they may be more likely to influence them.

Moreover, if someone is of the same gender, sexual orientation, or religion, they can likely influence each other as they relate to each other.

Simply, this involves the number of people there is in a group. There is a rule called psychosocial law which states that at some point, the number of influencers has less of an effect on the target.

Influence tends to significantly increase up until about 5 or 6 sources are attempting to influence.

Once past 5 or 6 people, the difference in impact increases but at a decreasing rate, meaning it is not as strong.

Numerous studies support the social impact theory. Below are some examples of famous studies:

Sedikides & Jackson (1990)

This was a field experiment that took place at the birdhouse at a zoo. A confederate told groups of visitors not to lean on the railings near the cages that held the birds to see whether the visitors would obey.

It was found that if the confederate was dressed in a zookeeper uniform, obedience was high. If they were dressed casually, obedience was lower.

This demonstrates social impact, especially the strength aspect, because of the perceived authority of the confederate.

As time went on, more visitors started ignoring the instruction not to lean on the railings.

This demonstrates immediacy because as the instruction gets less immediate, it has less of an impact. It was also found that the larger the group of visitors, the more disobedience was observed, which supports the idea of a division of impact.

Darley & Latané (1968)

This experiment involved participants sitting in booths with the purpose of discussing health issues over an intercom.

One of the speakers was a confederate who would pretend to suffer a heart attack during their talk. It was then observed whether the participants would help the confederate.

It was found that if there was one other participant present, they went for help 85% of the time. This dropped to 62% if there were two other participants and dropped further to 31% if there were 4+ participants.

This study supports Latané’s idea of numbers affecting social impact and the diffusion of responsibility.

You are more likely to help someone if you are the only person present, but there is less responsibility when there are more people present.

Milgram (1965)

Milgram completed many variations on his original famous experiment wherein ‘teacher’ participants were instructed to administer electric shocks to a ‘learner’ confederate who did not actually receive any shocks.

One variation experiment had two peer confederates in the room with the teacher, who refused to continue the experiment.

The results showed that obedience dropped from 65% to 10% with the presence of two rebelling confederates. This supports that social impact can be influenced by the number of individuals present.

What is dynamic social impact theory?

Social impact theory predicts how sources can influence a target, but a criticism is that it neglects how the target may influence the source.

Social impact theory is now often called dynamic social impact theory as it considers the target’s ability to influence the source. It views influence as a two-way exchange rather than a one-way street.

How does social impact theory relate to social media?

Social impact theory was obviously developed long before social media platforms existed. Nevertheless, social impact theory can be observed and utilized by people and brands to influence others.

If we have friends, family, and co-workers who post on social media, we are more likely to be influenced by their opinions if they are trusted people who are close to us (strength and social immediacy).

Likewise, the number of people who share the same opinion on social media is likely to influence others.

Brands can utilize social impact theory to sell their products on social media platforms. Brands and companies can get people of high status to help promote their products and get people to buy them.

For instance, if we see a celebrity that we like promoting a product on social media, saying how good it is, we may be more influenced to buy the product because of the strength of their influence.

This influence often works best if the influencer is of high status, the influencing statement is more immediate, and there are multiple influencers sharing the same message (strength, immediacy, and number).

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of personality and social psychology , 10 (3), 215.

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36 (4), 343.

Latané, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review , 88 (5), 438.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority . Human relations , 18 (1), 57-76.

Sedikides, C., & Jackson, J. M. (1990). Social impact theory: A field test of source strength, source immediacy and number of targets. Basic and applied social psychology , 11 (3), 273-281.

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

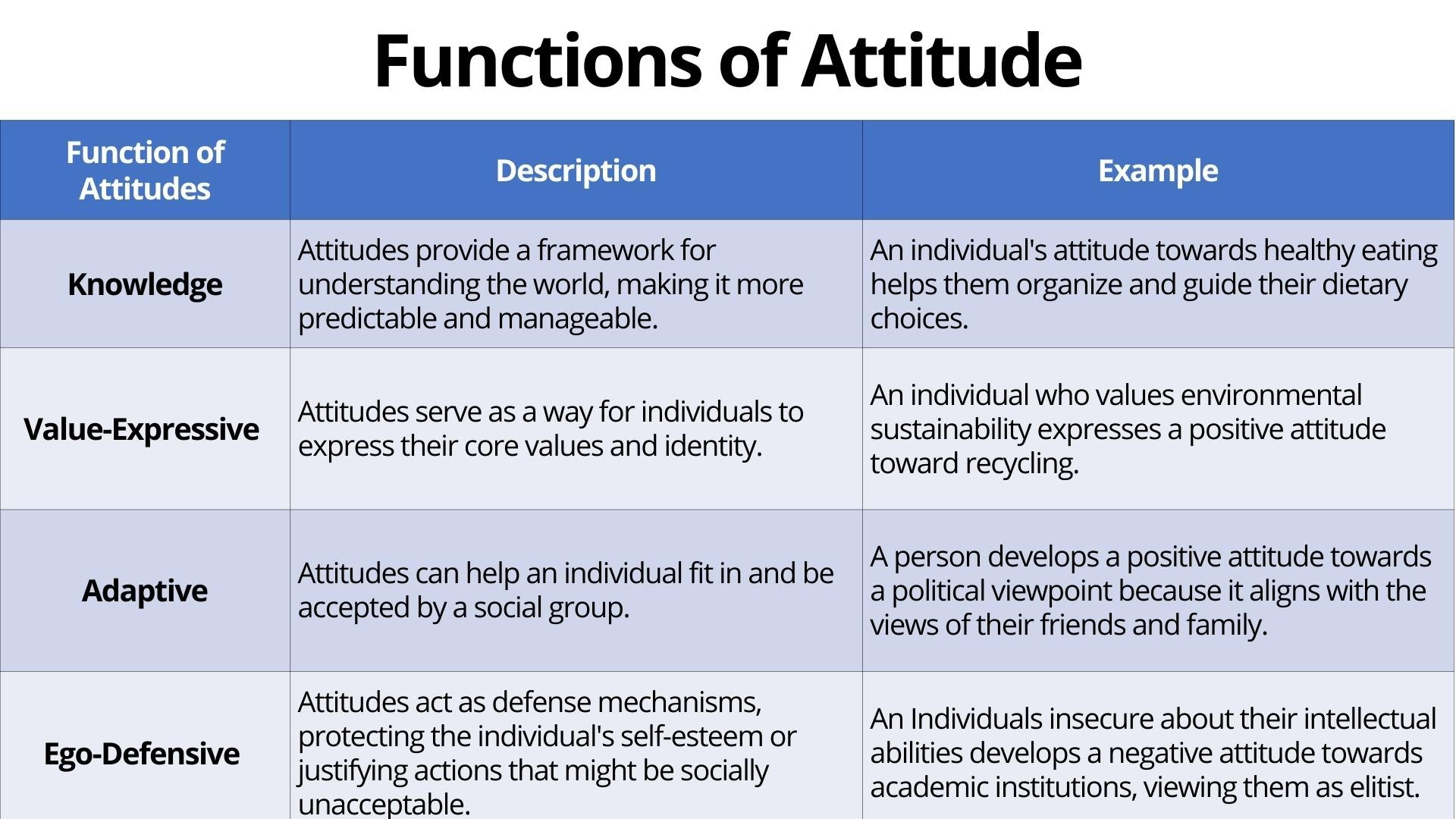

Functions of Attitude Theory

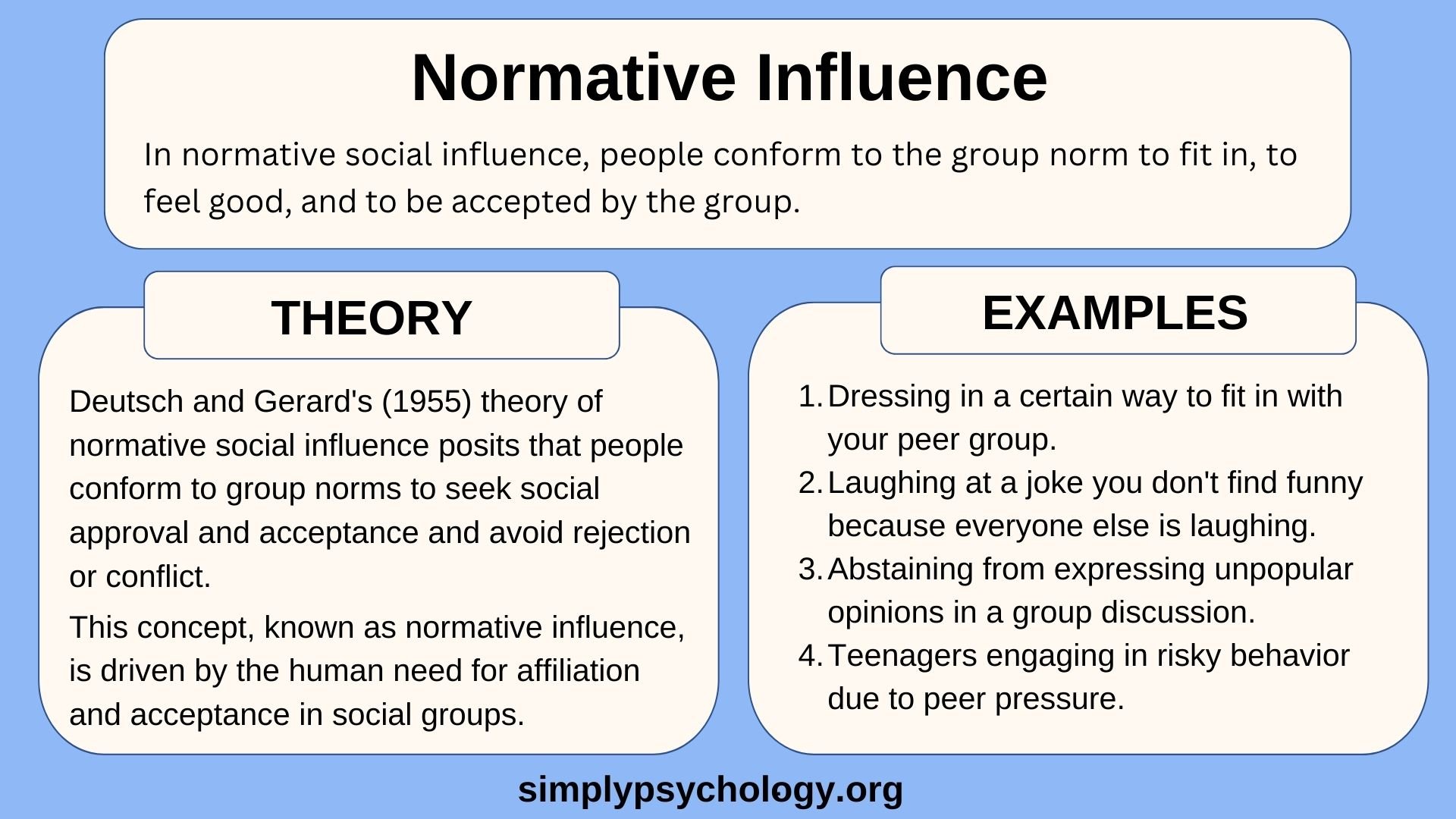

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

Famous Experiments , Social Science

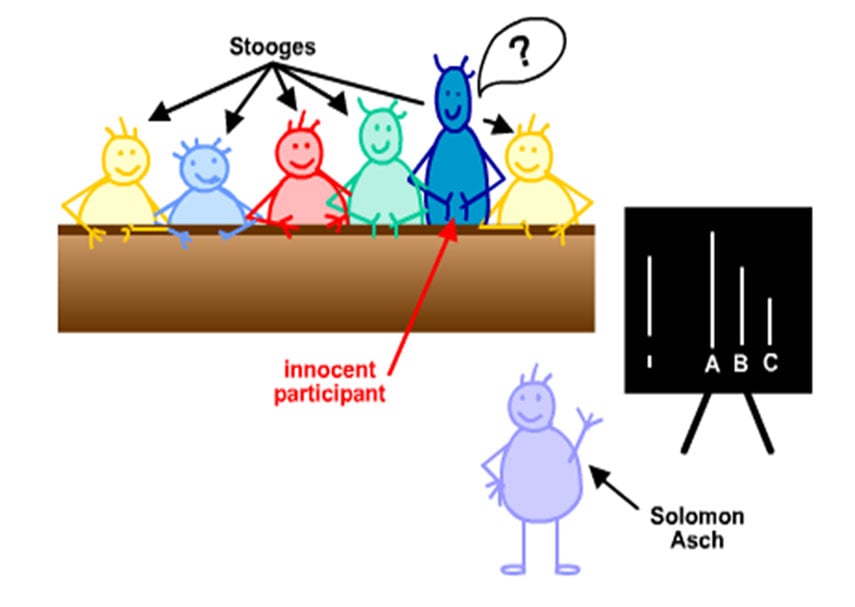

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

Birmingham City University

Skip to : main content | Skip to : main menu | Skip to : section menu

- Birmingham City University Home Page

- BCU Open Access Repository

Social Impact Assessment as a vehicle to better understand and improve stakeholder participation within urban development planning: The Maltese Case

Vella, Steven (2018) Social Impact Assessment as a vehicle to better understand and improve stakeholder participation within urban development planning: The Maltese Case. Doctoral thesis, Birmingham City University.

Environmental decision-making situations are typically complex and chaotic, with confused political messages, conflicting agendas and limited account taken of the wider social contexts in which decisions are made and play out. Many different types of knowledges from diverse social actors, sometimes with different epistemological and ontological backgrounds, must be taken into account. In environmental and urban planning, these challenges are increasingly being addressed through the integration of public participation in Social Impact Assessments (SIA) to inform Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). Research on environmental governance suggests that direct public participation and integration of stakeholder concerns in the environmental decision-making process could reduce the potential for conflict and lead to “better” decisions. However, the mechanisms through which participation benefits decision-making processes are unclear and contested. Previous attempts to understand “what works” in participation have been confounded by the multifaceted interactions that exist between the different components of social-ecological systems and the often-unacknowledged influence of context. The context of participation includes the social norms of society at large, and of different social units or communities of practice, the political context in which participation is performed and integrated into practice in urban planning, and the environmental context in which decisions will play out. Most of the disciplines that have traditionally sought to understand stakeholder engagement in environmental decisions struggle to recognize or analyse the role of these underlying dynamics and context. However, without a better understanding of these deep dynamics and the contexts in which participation takes places, it becomes very difficult to explain why some processes meet their objectives while others fail, or produce unintended consequences. This doctoral thesis makes empirical contributions to our understanding of stakeholder participation in urban development in Malta, and uses this case study research to generate methodological insights into best practices in stakeholder and public engagement and inter-professional collaboration in SIAs. Grounded in the analysis of the empirical data produced from the ethnographic experience of an applied anthropologist working as an SIA practitioner on three proposed urban development projects in Malta, the thesis differentiates between descriptive and explanatory factors to develop a typology and a theory of stakeholder and wider public engagement. The typology describes different types of public and stakeholder engagement based on agency (who initiates and leads engagement) and mode of engagement (from communication to co-production), while the theory explains much of the variation in outcomes from different types of engagement. This typology and theory is tested using empirical evidence from three Maltese SIA case studies, and then is further developed based on insights from case study findings and literature. It emphasises the roles of context and scale (especially temporal) in determining the initial choice of engagement type, and moves from an initial linear theoretical framework to one where the factors determining the outcomes of participation are framed as an interdependent, loosely nested set of factors, influencing one another along the planning life-cycle. This stresses the dynamic nature of the planning and decision-making process over time and across changing macro, meso and micro socio-cultural, political and geo-spatial contexts. Finally, the thesis shows how applied anthropology and its practitioners can effectively combine critical social theory of complex systems with its application and pragmatic engagement with the contemporary problems of the social and physical environment, working and collaborating across disciplinary borders and blurring the lines between theory and practice. Anthropology and its methods can offer an alternative way to look at the world and the range of methodological approaches that anthropologists are trained in, especially qualitative data collection based on participant observation and ethnography provide that extra ‘edge’ to the analysis of the complex systems that urban and environmental conservation projects investigate, while building relationships that help increase positive outcomes of stakeholder involvement within such initiatives and projects.

Actions (login required)

In this section...

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Social Impact Theory

Social impact theory definition.

Social impact theory differs from other models of social influence by incorporating strength and immediacy, instead of relying exclusively on the number of sources. Although criticisms have been raised, the theory was (and continues to be) important for the study of group influence. Reformulating social impact theory to accommodate the influence of targets on sources (i.e., dynamic social impact theory) has further increased its validity and range of explainable phenomena. Furthermore, pushing social impact theory into applied areas in social psychology continues to offer fresh perspectives and predictions about group influence.

Tests of Social Impact Theory

Number of sources.

Social impact theory predicts multiple sources will have more influence on a target than will a single source. Research has generally supported this prediction: Many studies have shown a message presented by multiple people exerts more influence than does the same message presented by a single person. However, the effect of multiple sources only holds true under three conditions. First, the influencing message must contain strong (rather than weak) arguments. Weakly reasoned arguments, whether given by multiple sources or not, result in little attitude change. Second, the target must perceive the multiple sources to be independent of one another. The effect of multiple sources disappears if the target believes the sources “share a single brain.” The colluding party will in such cases be no more effective than will a single source. Third, as the number of sources grows large, adding additional sources will have no additional effect. For example, the effect of 4 independent sources substantially differs from the effect of 1 source, but the effect of 12 independent sources does not substantially differ from the effect of 15 independent sources.

Strength and Immediacy

The inclusion of strength and immediacy as variables is unique to social impact theory; no other social influence theory includes these variables. Defining strength and immediacy in research studies is less straightforward than is defining the number of sources, but the operational definitions have been relatively consistent across studies. Researchers usually vary the source’s strength with differences in either age or occupation (adults with prestigious jobs presumably have more strength than do young adult college students). Researchers usually vary the source’s immediacy either with differences in the physical distance between the source and the target (less distance means more immediacy) or, in cases of media presentation, with differences in the size of the visual image of the source (a larger image focused more on the face relative to the body means more immediacy).

Surprisingly, however, these two components of the model have received considerably less empirical investigation than has the number of sources; therefore, the effects of strength and immediacy on influence are less clear. A statistical technique called meta-analysis, which allows researchers to combine the results of many different studies together, has helped researchers draw at least some conclusions. Across studies, meta-analyses on these two variables indicate statistically significant effects of low magnitude (i.e., the effects, though definitely present, are not very strong). Furthermore, strength and immediacy appear to only exert influence in studies using self-report measures; the effects of strength and immediacy wane when more objective measures of behavior are examined.

Dynamic Social Impact Theory

In its traditional form, social impact theory predicts how sources will influence a target, but neglects how the target may influence the sources. Dynamic social impact theory considers this reciprocal relationship. The theory predicts people’s personal attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions will tend to cluster together at the group level; this group-level clustering depends on the strength, immediacy, and number of social influence sources. Day-to-day interaction with others leads to attitude change in the individual, which then helps contribute to the pattern of beliefs at the group level. In support of the immediacy component of dynamic social impact theory, for example, studies have shown randomly assigned participants were much more likely to share opinions and behaviors with those situated close to them than with those situated away from them, an effect which occurred after only five rounds of discussion.

New Directions for Social Impact Theory

Recently, researchers have pushed social impact theory outside the areas of persuasion and obedience into more applied areas of social psychology. For example, recent studies have examined social impact theory in the context of consumer behavior. In one study, researchers varied the size and proximity of a social presence in retail stores, and examined how this presence influenced shopping behavior. Furthermore, several tenets of social impact theory seem to predict political participation. One study found as the number of people eligible to vote increases, the proportion of people who actually vote asymptotically decreases. This finding accords with social impact theory, which predicts an increasingly marginal impact of sources as their number grows very large.

Social impact theory has enjoyed great theoretical and empirical attention, and it continues to inspire interesting scientific investigation.

References:

- Harkins, S. G., & Latane, B. (1998). Population and political participation: A social impact analysis of voter responsibility. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2, 192-207.

- Latane, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review, 88, 438-453.

Social Impact Theory (Definition + Examples)

In Milgram’s Obedience experiment, participants delivered deadly electric shocks simply because they were told. In the Stanford Prison Experiment, participants got violent with each other, even though they were in a simulation that was meant to last only a few days. Outside of social psychology experiments, we have witnessed people do unimaginable and questionable things.

The Social Impact Theory attempts to bring some clarity to this confusion.

Latané’s Social Impact Theory suggests that individuals can be sources or targets of social influence. It attempts to answer why we perform behaviors in certain situations. The source influences the target depending on various factors. Latané demonstrates these factors using an equation: i = f(S * I * N).

History of Social Impact Theory

In 1981, psychologist Bibb Latané created the idea of Social Impact Theory. If Bibb Latané’s name looks familiar to you, it’s because he is often credited as one of the psychologists who brought the Bystander Effect to light.

In Social Impact Theory, “i” is the impact. It’s a function of three variables: strength (s,) immediacy (i,) and the number of sources (n.) If any of these are significantly high or low, it will have a serious effect on the impact on the target. As you read about social impact theory, you are going to dive deeper into these factors and how they can impact someone’s behavior.

Social Impact Theory's Three Variables

Strength simply refers to the importance of the source. If the source appears to be an authority on a subject (or any subject,) the target is more likely to perform the behaviors that they suggest.

Two categories of strength determine a source’s impact: trans-situational strength and situation-specific strength.

Trans-situational Strength

The first type of strength exists no matter what the situation is. Trans-situational strength includes:

- The source’s age

- Physical appearance or other characteristics

- Held authority

- Perceived intelligence

Of course, society and culture may influence whether the source has trans-situational strength. In some countries, royalty has more strength than any other government figure. In other countries, the government leaders are the most important. Context will shape the source’s strength regardless of the situation.

Situation-specific Strength

This type of strength looks closer at the situation at hand and the behavior that the target is being asked to perform. Let’s say you were reading an article online about COVID in the early days of the pandemic. You see a quote from a medical doctor telling you to stay inside. You’re more likely going to listen to that doctor because they have authority in the situation.

Now let’s say you’re reading an article about fashion. You see a quote from a medical doctor telling you that the color pink is out, and the color orange is in. Not only are you unlikely to listen to the doctor’s advice, but you are also likely to be confused as to why this person is making a comment on something so out of their expertise.

Other factors under the umbrella of situation-specific strength include:

- Peer pressure

- Intoxication

- Political climate

Immediacy also makes a difference. But when psychologists talk about immediacy, they aren’t just talking about time.

Three forms of immediacy may impact a target: physical immediacy, temporal immediacy, and social immediacy.

Physical Immediacy

Immediacy may also be defined as “the quality of bringing one into direct and instant involvement with something.” If a source is physically close to a target, they are more likely to have an impact.

Think about this. If someone sends you an email asking you to answer a survey, you may take them up on it. (This is when strength really comes into play.) But if someone comes up to you at the grocery store and asks you to answer a survey, you are more likely to say yes (or at least respond to the person who is asking.)

Temporal Immediacy

Time also makes an impact on a target. A target is more likely to act immediately after a source asked them to do so. If the target waits five, ten, or twenty minutes, the likelihood that they are going to ask will decrease with time.

Marketers often consider this as they build campaigns or write ads. People are more likely to “buy now” rather than “buy at some point.” If you give potential customers too much time to weigh their options, they are less likely to act.

Social Immediacy

The last form of immediacy is social immediacy. This ties in with the strength of a source. If the source and target are “close,” the source is more likely to make an impact. The target may see themselves in the source because of the source’s race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, etc. The idea that we are more comfortable with people who are “like us” is not new in psychology. But the Social Impact Theory suggests that are also more likely to be influenced by people who are “like us.”

Number is arguably the most important of these three factors. Even if a single source is not physically close or particularly “strong,” they will still be impactful if they are surrounded by many other sources.

One example of this comes from Stanley Milgram . Milgram is known for conducting one of the most controversial experiments in social psychology history. But not all of his experiments involved electric shocks. In 1968, Milgram asked a group of actors to stand on the street and stare up at the sky for 60 seconds at a time. As the actors did this, Milgram recorded how many passersby followed the gaze of the actors.

Milgram found that the number of actors influenced how many people followed their gaze. One person standing on the street and looking at the sky didn’t influence too many passersby. But a group of five or ten are more likely to turn some heads.

Psychosocial Law

How much influence does that fifth or tenth source have on a target? Well, not a lot. The Psychosocial Law of the Social Impact Theory states that each subsequent source has less and less impact on the target. The third person to look at the sky is not going to be as impactful as the first or second. But they will still contribute to the overall impact.

Dynamic Social Impact Theory

Latané and his colleagues continued their research on social impact theory by “zooming out.” They looked at how different groups of people interact and influence each other. These observations, and the patterns within them, became the basis for dynamic social impact theory.

When compared to Latané’s larger body of work, social impact theory is seen as a “static” theory. The theory focuses on predicting how one person may be influenced on one topic or element by a larger group. Dynamic social impact theory looks at how this one person or group, who is influenced, may also influence a group or person as well. For example, celebrities influence the media, and media influences celebrities. The common people influence politicians and politicians influence the common people. This reciprocity is considered in dynamic social impact theory.

What Is Dynamic Social Impact Theory?

Dynamic social impact theory (DSIT) describes how groups create culture. Latané and colleagues picked up on four patterns that they believe have an impact and shape culture among groups. These four patterns are clustering, correlation, consolidation, and continuing diversity. At the heart of culture, the theory suggests, is communication between people

What are these four patterns, exactly? Let’s explore.

Clustering is the presence of regional differences in attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. People influence other people who are close to them. For example, people in the United States are more likely to drink coffee in the morning to wake themselves up. People in the United Kingdom prefer tea. People in Austin might reach for a breakfast taco in the morning, while people in New York City prefer to order bagels. The connections between food and drink preferences and their regional locations happen due to clustering. This makes sense. If you are not sure what to have for breakfast, you are likely to check out what is being ordered by people around you, rather than people across the globe.

Correlation

When you spend time around a group of people, the group tends to adopt a similar mindset and perspective. As the group forms and opinions are shared, you all start to convince each other to believe the same things. We see this often in political parties. When a group of people belongs to a political party, they are more likely to carry all the beliefs of that party. This may happen because they only listen to commentators from that party, or are not exposed to the opposing side’s argument.

Consolidation and Continuing Diversity

Cultures change. The beliefs that Americans have had on same-sex or interracial marriage, for example, have changed over time. In this way, the people influence the politicians, and politicians influence the people. Consolidation (and continuing diversity) are two patterns that address how groups of people change.

These two processes are typically at odds with each other. Consolidation describes the minority influence giving way to the majority influence. The majority “takes over” the minority influence until it is largely eradicated. This doesn’t always happen completely. In many cases, minority groups within a larger culture remain isolated but alive. That isolation allows them to hold onto their minority influence. This is continuing diversity.

Minority opinion can also “take over” majority opinion.

The Importance of Communication in DSIT

As mentioned before, communication is central to all of these patterns. Without communication, culture would remain stagnant. Communication isn’t just two neighbors having a conversation over their fences. Political signs on front lawns are communication. Storefronts advertising “the best bagels in Brooklyn” are communicating. Recalling moments in regional history is communication. Communication may be intentional or unintentional, but either way, it can shape culture and the attitudes of people within a group.

This perspective made social impact theory and DSIT significant ideas of their time. If communication can have such a big impact on culture and majority opinion, then scholars might have a better idea of how large swaths of people can be influenced to meet certain goals.

How Is Social Impact Theory Reductionist?

"Reductionist" theories attempt to simplify very complicated topics in psychology. Many critics of social impact theory believe that it is reductionist. Strength, immediacy, and number of sources do not cover every factor that goes into decisions or behaviors. There may be other factors at play. Credibility, the target’s ability to perform a behavior, and the actual behavior may also influence whether or not someone performs a behavior. But despite this criticism, Social Impact Theory is still important when thinking about the impact a person can have on another.

Related posts:

- 47+ Blue Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- 41+ White Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- 201+ Strengths Examples For SWOT Analysis (Huge List)

- Social Institutions (Definition + 7 Examples)

- Dream Interpreter & Dictionary (270+ Meanings)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Social Impact Theory of Human Communication Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Works cited.

The social impact theory is the theory that is applied to individual and inter-group relations as well as tendencies that may be viewed in the course of human communication. In general, the theory investigates the influence of society on individuals and the opposite influence an individual may produce on society. it has been long ago proved that the interrelations of two individuals and influence they may produce on each other highly differ from the distribution of power that occurs between a group and an individual. Together with this, it is a fact that the more the size of the group is, the more effective the influence produced by it on a individual is. The opposite influence is also reducing with the extent of increasing the number of the group on which influence is produced. Scientifically speaking, it is “a model that conceives of influence from other people… acting on individuals, much as physical forces can affect an object” (Leslie).

There are two types of the social impact theories – first of all, it is the general theory that claims that all forms of social influence, whatever the specific social process, will be proportional to a multiplicative function of the strength, immediacy, and number of people who are the sources of influence, and inversely proportional to the strength, immediacy, and number of people being influenced (Latane and Drigotas).

In contrast to the general theory, or as its consequence, there appeared a dynamic social impact theory that explores the relations between people within and between groups, juxtaposing the influence that may be produced by an individual on a group and vice versa. According to the opinion of Mabry and Sudweeks, the dynamic social impact theory has a disadvantage of not considering the relationd of space, time and communication modality, which makes it limited to a certain extent (Mabry and Sudweeks, p. 2).

The social impact theory has found much support and became very interesting for research as its functionality has been proved in many spheres. There is even a method of utilizing the theory in order to manipulate people and achieve one’s goal: people who are knowledgeable in manipulating people may do it much quicker and easier if they involve some person into their influence thus creating a group, and then continue producing influence on other people with the help of this group. As a result, the number of people in the group enlarges, becomes more powerful and fulfills the initial aim of the initiator. Together with this, the members of the group may not even realize that the follow not their aims but the initially stipulated aim of the person who was the creator of the group.

The discussed theory has been successfully applied in many social events such as massive gathering, propaganda, group work in an organization, learning the principles of convincing people in something. Group pressure is also a common phenomenon in any place where an individual may come across a need to persuade some people thus entering the relations of mutual influence. It is absolutely commonplace to see the examples of the theory in action. “In meetings in the workplace, few will speak out if their opinion differs from the majority” (Social Impact Theory).

The theory has been developed recently; there were many findings represented in the sphere of psychology, furthering its findings. For example, it is interesting to note some of Latane’s findings, for example, that each individual can influence others; but the more people are present, the less influence any one individual will have. Thus, we are more likely to listen attentively to a speaker if we are in a small group than if we were in a large group (Theory of Social Impact).

- Latane, Bibb, and Drigotas, Stephen. Social Impact Theory. 2009.

- Leslie. Social Impact Theory, 2008.

- Mabry, Edward, and Sudweeks, Evelyn. “Assessing the Impacts of Dynamic Social Impact Theory in Asynchronous Groups” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Dresden International Congress Centre, Dresden, Germany, 2009.

- Social Impact Theory , 2009. Web.

- Theory of Social Impact, 2009.

- Intergroup Conflict and Its Management

- Social Interactions Through the Virtual Video Modality

- Intimate Partner Violence: Treatment Modality

- Wasta in Saudi Arabia and Vision 2030

- Fully Automated Luxury Communism

- Early Interventions Preventing Serial Offending

- Diffusion of Innovation: Key Aspects

- "Icewine, Roquefort Cheese, and the Navajo Nation" by C. Vowel

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 7). Social Impact Theory of Human Communication. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-impact-theory-of-human-communication/

"Social Impact Theory of Human Communication." IvyPanda , 7 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/social-impact-theory-of-human-communication/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Social Impact Theory of Human Communication'. 7 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Social Impact Theory of Human Communication." March 7, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-impact-theory-of-human-communication/.

1. IvyPanda . "Social Impact Theory of Human Communication." March 7, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-impact-theory-of-human-communication/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Social Impact Theory of Human Communication." March 7, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-impact-theory-of-human-communication/.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 76, Issue 2

- COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1512-4471 Emily Long 1 ,

- Susan Patterson 1 ,

- Karen Maxwell 1 ,

- Carolyn Blake 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-4566 Raquel Bosó Pérez 1 ,

- Ruth Lewis 1 ,

- Mark McCann 1 ,

- Julie Riddell 1 ,

- Kathryn Skivington 1 ,

- Rachel Wilson-Lowe 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4409-6601 Kirstin R Mitchell 2

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- 2 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health & Wellbeing , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Emily Long, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G3 7HR, UK; emily.long{at}glasgow.ac.uk

This essay examines key aspects of social relationships that were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It focuses explicitly on relational mechanisms of health and brings together theory and emerging evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to make recommendations for future public health policy and recovery. We first provide an overview of the pandemic in the UK context, outlining the nature of the public health response. We then introduce four distinct domains of social relationships: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy, highlighting the mechanisms through which the pandemic and associated public health response drastically altered social interactions in each domain. Throughout the essay, the lens of health inequalities, and perspective of relationships as interconnecting elements in a broader system, is used to explore the varying impact of these disruptions. The essay concludes by providing recommendations for longer term recovery ensuring that the social relational cost of COVID-19 is adequately considered in efforts to rebuild.

- inequalities

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated or analysed for this essay.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216690

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Infectious disease pandemics, including SARS and COVID-19, demand intrapersonal behaviour change and present highly complex challenges for public health. 1 A pandemic of an airborne infection, spread easily through social contact, assails human relationships by drastically altering the ways through which humans interact. In this essay, we draw on theories of social relationships to examine specific ways in which relational mechanisms key to health and well-being were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Relational mechanisms refer to the processes between people that lead to change in health outcomes.

At the time of writing, the future surrounding COVID-19 was uncertain. Vaccine programmes were being rolled out in countries that could afford them, but new and more contagious variants of the virus were also being discovered. The recovery journey looked long, with continued disruption to social relationships. The social cost of COVID-19 was only just beginning to emerge, but the mental health impact was already considerable, 2 3 and the inequality of the health burden stark. 4 Knowledge of the epidemiology of COVID-19 accrued rapidly, but evidence of the most effective policy responses remained uncertain.

The initial response to COVID-19 in the UK was reactive and aimed at reducing mortality, with little time to consider the social implications, including for interpersonal and community relationships. The terminology of ‘social distancing’ quickly became entrenched both in public and policy discourse. This equation of physical distance with social distance was regrettable, since only physical proximity causes viral transmission, whereas many forms of social proximity (eg, conversations while walking outdoors) are minimal risk, and are crucial to maintaining relationships supportive of health and well-being.

The aim of this essay is to explore four key relational mechanisms that were impacted by the pandemic and associated restrictions: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy. We use relational theories and emerging research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic response to make three key recommendations: one regarding public health responses; and two regarding social recovery. Our understanding of these mechanisms stems from a ‘systems’ perspective which casts social relationships as interdependent elements within a connected whole. 5

Social networks

Social networks characterise the individuals and social connections that compose a system (such as a workplace, community or society). Social relationships range from spouses and partners, to coworkers, friends and acquaintances. They vary across many dimensions, including, for example, frequency of contact and emotional closeness. Social networks can be understood both in terms of the individuals and relationships that compose the network, as well as the overall network structure (eg, how many of your friends know each other).

Social networks show a tendency towards homophily, or a phenomenon of associating with individuals who are similar to self. 6 This is particularly true for ‘core’ network ties (eg, close friends), while more distant, sometimes called ‘weak’ ties tend to show more diversity. During the height of COVID-19 restrictions, face-to-face interactions were often reduced to core network members, such as partners, family members or, potentially, live-in roommates; some ‘weak’ ties were lost, and interactions became more limited to those closest. Given that peripheral, weaker social ties provide a diversity of resources, opinions and support, 7 COVID-19 likely resulted in networks that were smaller and more homogenous.

Such changes were not inevitable nor necessarily enduring, since social networks are also adaptive and responsive to change, in that a disruption to usual ways of interacting can be replaced by new ways of engaging (eg, Zoom). Yet, important inequalities exist, wherein networks and individual relationships within networks are not equally able to adapt to such changes. For example, individuals with a large number of newly established relationships (eg, university students) may have struggled to transfer these relationships online, resulting in lost contacts and a heightened risk of social isolation. This is consistent with research suggesting that young adults were the most likely to report a worsening of relationships during COVID-19, whereas older adults were the least likely to report a change. 8

Lastly, social connections give rise to emergent properties of social systems, 9 where a community-level phenomenon develops that cannot be attributed to any one member or portion of the network. For example, local area-based networks emerged due to geographic restrictions (eg, stay-at-home orders), resulting in increases in neighbourly support and local volunteering. 10 In fact, research suggests that relationships with neighbours displayed the largest net gain in ratings of relationship quality compared with a range of relationship types (eg, partner, colleague, friend). 8 Much of this was built from spontaneous individual interactions within local communities, which together contributed to the ‘community spirit’ that many experienced. 11 COVID-19 restrictions thus impacted the personal social networks and the structure of the larger networks within the society.

Social support

Social support, referring to the psychological and material resources provided through social interaction, is a critical mechanism through which social relationships benefit health. In fact, social support has been shown to be one of the most important resilience factors in the aftermath of stressful events. 12 In the context of COVID-19, the usual ways in which individuals interact and obtain social support have been severely disrupted.

One such disruption has been to opportunities for spontaneous social interactions. For example, conversations with colleagues in a break room offer an opportunity for socialising beyond one’s core social network, and these peripheral conversations can provide a form of social support. 13 14 A chance conversation may lead to advice helpful to coping with situations or seeking formal help. Thus, the absence of these spontaneous interactions may mean the reduction of indirect support-seeking opportunities. While direct support-seeking behaviour is more effective at eliciting support, it also requires significantly more effort and may be perceived as forceful and burdensome. 15 The shift to homeworking and closure of community venues reduced the number of opportunities for these spontaneous interactions to occur, and has, second, focused them locally. Consequently, individuals whose core networks are located elsewhere, or who live in communities where spontaneous interaction is less likely, have less opportunity to benefit from spontaneous in-person supportive interactions.

However, alongside this disruption, new opportunities to interact and obtain social support have arisen. The surge in community social support during the initial lockdown mirrored that often seen in response to adverse events (eg, natural disasters 16 ). COVID-19 restrictions that confined individuals to their local area also compelled them to focus their in-person efforts locally. Commentators on the initial lockdown in the UK remarked on extraordinary acts of generosity between individuals who belonged to the same community but were unknown to each other. However, research on adverse events also tells us that such community support is not necessarily maintained in the longer term. 16

Meanwhile, online forms of social support are not bound by geography, thus enabling interactions and social support to be received from a wider network of people. Formal online social support spaces (eg, support groups) existed well before COVID-19, but have vastly increased since. While online interactions can increase perceived social support, it is unclear whether remote communication technologies provide an effective substitute from in-person interaction during periods of social distancing. 17 18 It makes intuitive sense that the usefulness of online social support will vary by the type of support offered, degree of social interaction and ‘online communication skills’ of those taking part. Youth workers, for instance, have struggled to keep vulnerable youth engaged in online youth clubs, 19 despite others finding a positive association between amount of digital technology used by individuals during lockdown and perceived social support. 20 Other research has found that more frequent face-to-face contact and phone/video contact both related to lower levels of depression during the time period of March to August 2020, but the negative effect of a lack of contact was greater for those with higher levels of usual sociability. 21 Relatedly, important inequalities in social support exist, such that individuals who occupy more socially disadvantaged positions in society (eg, low socioeconomic status, older people) tend to have less access to social support, 22 potentially exacerbated by COVID-19.

Social and interactional norms

Interactional norms are key relational mechanisms which build trust, belonging and identity within and across groups in a system. Individuals in groups and societies apply meaning by ‘approving, arranging and redefining’ symbols of interaction. 23 A handshake, for instance, is a powerful symbol of trust and equality. Depending on context, not shaking hands may symbolise a failure to extend friendship, or a failure to reach agreement. The norms governing these symbols represent shared values and identity; and mutual understanding of these symbols enables individuals to achieve orderly interactions, establish supportive relationship accountability and connect socially. 24 25

Physical distancing measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 radically altered these norms of interaction, particularly those used to convey trust, affinity, empathy and respect (eg, hugging, physical comforting). 26 As epidemic waves rose and fell, the work to negotiate these norms required intense cognitive effort; previously taken-for-granted interactions were re-examined, factoring in current restriction levels, own and (assumed) others’ vulnerability and tolerance of risk. This created awkwardness, and uncertainty, for example, around how to bring closure to an in-person interaction or convey warmth. The instability in scripted ways of interacting created particular strain for individuals who already struggled to encode and decode interactions with others (eg, those who are deaf or have autism spectrum disorder); difficulties often intensified by mask wearing. 27

Large social gatherings—for example, weddings, school assemblies, sporting events—also present key opportunities for affirming and assimilating interactional norms, building cohesion and shared identity and facilitating cooperation across social groups. 28 Online ‘equivalents’ do not easily support ‘social-bonding’ activities such as singing and dancing, and rarely enable chance/spontaneous one-on-one conversations with peripheral/weaker network ties (see the Social networks section) which can help strengthen bonds across a larger network. The loss of large gatherings to celebrate rites of passage (eg, bar mitzvah, weddings) has additional relational costs since these events are performed by and for communities to reinforce belonging, and to assist in transitioning to new phases of life. 29 The loss of interaction with diverse others via community and large group gatherings also reduces intergroup contact, which may then tend towards more prejudiced outgroup attitudes. While online interaction can go some way to mimicking these interaction norms, there are key differences. A sense of anonymity, and lack of in-person emotional cues, tends to support norms of polarisation and aggression in expressing differences of opinion online. And while online platforms have potential to provide intergroup contact, the tendency of much social media to form homogeneous ‘echo chambers’ can serve to further reduce intergroup contact. 30 31

Intimacy relates to the feeling of emotional connection and closeness with other human beings. Emotional connection, through romantic, friendship or familial relationships, fulfils a basic human need 32 and strongly benefits health, including reduced stress levels, improved mental health, lowered blood pressure and reduced risk of heart disease. 32 33 Intimacy can be fostered through familiarity, feeling understood and feeling accepted by close others. 34

Intimacy via companionship and closeness is fundamental to mental well-being. Positively, the COVID-19 pandemic has offered opportunities for individuals to (re)connect and (re)strengthen close relationships within their household via quality time together, following closure of many usual external social activities. Research suggests that the first full UK lockdown period led to a net gain in the quality of steady relationships at a population level, 35 but amplified existing inequalities in relationship quality. 35 36 For some in single-person households, the absence of a companion became more conspicuous, leading to feelings of loneliness and lower mental well-being. 37 38 Additional pandemic-related relational strain 39 40 resulted, for some, in the initiation or intensification of domestic abuse. 41 42

Physical touch is another key aspect of intimacy, a fundamental human need crucial in maintaining and developing intimacy within close relationships. 34 Restrictions on social interactions severely restricted the number and range of people with whom physical affection was possible. The reduction in opportunity to give and receive affectionate physical touch was not experienced equally. Many of those living alone found themselves completely without physical contact for extended periods. The deprivation of physical touch is evidenced to take a heavy emotional toll. 43 Even in future, once physical expressions of affection can resume, new levels of anxiety over germs may introduce hesitancy into previously fluent blending of physical and verbal intimate social connections. 44

The pandemic also led to shifts in practices and norms around sexual relationship building and maintenance, as individuals adapted and sought alternative ways of enacting sexual intimacy. This too is important, given that intimate sexual activity has known benefits for health. 45 46 Given that social restrictions hinged on reducing household mixing, possibilities for partnered sexual activity were primarily guided by living arrangements. While those in cohabiting relationships could potentially continue as before, those who were single or in non-cohabiting relationships generally had restricted opportunities to maintain their sexual relationships. Pornography consumption and digital partners were reported to increase since lockdown. 47 However, online interactions are qualitatively different from in-person interactions and do not provide the same opportunities for physical intimacy.

Recommendations and conclusions

In the sections above we have outlined the ways in which COVID-19 has impacted social relationships, showing how relational mechanisms key to health have been undermined. While some of the damage might well self-repair after the pandemic, there are opportunities inherent in deliberative efforts to build back in ways that facilitate greater resilience in social and community relationships. We conclude by making three recommendations: one regarding public health responses to the pandemic; and two regarding social recovery.

Recommendation 1: explicitly count the relational cost of public health policies to control the pandemic

Effective handling of a pandemic recognises that social, economic and health concerns are intricately interwoven. It is clear that future research and policy attention must focus on the social consequences. As described above, policies which restrict physical mixing across households carry heavy and unequal relational costs. These include for individuals (eg, loss of intimate touch), dyads (eg, loss of warmth, comfort), networks (eg, restricted access to support) and communities (eg, loss of cohesion and identity). Such costs—and their unequal impact—should not be ignored in short-term efforts to control an epidemic. Some public health responses—restrictions on international holiday travel and highly efficient test and trace systems—have relatively small relational costs and should be prioritised. At a national level, an earlier move to proportionate restrictions, and investment in effective test and trace systems, may help prevent escalation of spread to the point where a national lockdown or tight restrictions became an inevitability. Where policies with relational costs are unavoidable, close attention should be paid to the unequal relational impact for those whose personal circumstances differ from normative assumptions of two adult families. This includes consideration of whether expectations are fair (eg, for those who live alone), whether restrictions on social events are equitable across age group, religious/ethnic groupings and social class, and also to ensure that the language promoted by such policies (eg, households; families) is not exclusionary. 48 49 Forethought to unequal impacts on social relationships should thus be integral to the work of epidemic preparedness teams.

Recommendation 2: intelligently balance online and offline ways of relating

A key ingredient for well-being is ‘getting together’ in a physical sense. This is fundamental to a human need for intimate touch, physical comfort, reinforcing interactional norms and providing practical support. Emerging evidence suggests that online ways of relating cannot simply replace physical interactions. But online interaction has many benefits and for some it offers connections that did not exist previously. In particular, online platforms provide new forms of support for those unable to access offline services because of mobility issues (eg, older people) or because they are geographically isolated from their support community (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) youth). Ultimately, multiple forms of online and offline social interactions are required to meet the needs of varying groups of people (eg, LGBTQ, older people). Future research and practice should aim to establish ways of using offline and online support in complementary and even synergistic ways, rather than veering between them as social restrictions expand and contract. Intelligent balancing of online and offline ways of relating also pertains to future policies on home and flexible working. A decision to switch to wholesale or obligatory homeworking should consider the risk to relational ‘group properties’ of the workplace community and their impact on employees’ well-being, focusing in particular on unequal impacts (eg, new vs established employees). Intelligent blending of online and in-person working is required to achieve flexibility while also nurturing supportive networks at work. Intelligent balance also implies strategies to build digital literacy and minimise digital exclusion, as well as coproducing solutions with intended beneficiaries.

Recommendation 3: build stronger and sustainable localised communities

In balancing offline and online ways of interacting, there is opportunity to capitalise on the potential for more localised, coherent communities due to scaled-down travel, homeworking and local focus that will ideally continue after restrictions end. There are potential economic benefits after the pandemic, such as increased trade as home workers use local resources (eg, coffee shops), but also relational benefits from stronger relationships around the orbit of the home and neighbourhood. Experience from previous crises shows that community volunteer efforts generated early on will wane over time in the absence of deliberate work to maintain them. Adequately funded partnerships between local government, third sector and community groups are required to sustain community assets that began as a direct response to the pandemic. Such partnerships could work to secure green spaces and indoor (non-commercial) meeting spaces that promote community interaction. Green spaces in particular provide a triple benefit in encouraging physical activity and mental health, as well as facilitating social bonding. 50 In building local communities, small community networks—that allow for diversity and break down ingroup/outgroup views—may be more helpful than the concept of ‘support bubbles’, which are exclusionary and less sustainable in the longer term. Rigorously designed intervention and evaluation—taking a systems approach—will be crucial in ensuring scale-up and sustainability.

The dramatic change to social interaction necessitated by efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 created stark challenges but also opportunities. Our essay highlights opportunities for learning, both to ensure the equity and humanity of physical restrictions, and to sustain the salutogenic effects of social relationships going forward. The starting point for capitalising on this learning is recognition of the disruption to relational mechanisms as a key part of the socioeconomic and health impact of the pandemic. In recovery planning, a general rule is that what is good for decreasing health inequalities (such as expanding social protection and public services and pursuing green inclusive growth strategies) 4 will also benefit relationships and safeguard relational mechanisms for future generations. Putting this into action will require political will.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- Ford T , et al

- Riordan R ,

- Ford J , et al

- Glonti K , et al

- McPherson JM ,

- Smith-Lovin L

- Granovetter MS

- Fancourt D et al

- Stadtfeld C

- Office for Civil Society

- Cook J et al

- Rodriguez-Llanes JM ,

- Guha-Sapir D

- Patulny R et al

- Granovetter M

- Winkeler M ,

- Filipp S-H ,

- Kaniasty K ,

- de Terte I ,

- Guilaran J , et al

- Wright KB ,

- Martin J et al

- Gabbiadini A ,

- Baldissarri C ,

- Durante F , et al

- Sommerlad A ,

- Marston L ,

- Huntley J , et al

- Turner RJ ,

- Bicchieri C

- Brennan G et al

- Watson-Jones RE ,

- Amichai-Hamburger Y ,

- McKenna KYA

- Page-Gould E ,

- Aron A , et al

- Pietromonaco PR ,

- Timmerman GM

- Bradbury-Jones C ,

- Mikocka-Walus A ,

- Klas A , et al

- Marshall L ,

- Steptoe A ,

- Stanley SM ,

- Campbell AM

- ↵ (ONS), O.f.N.S., Domestic abuse during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, England and Wales . Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseduringthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicenglandandwales/november2020

- Rosenberg M ,

- Hensel D , et al

- Banerjee D ,

- Bruner DW , et al

- Bavel JJV ,

- Baicker K ,

- Boggio PS , et al

- van Barneveld K ,

- Quinlan M ,

- Kriesler P , et al

- Mitchell R ,

- de Vries S , et al

Twitter @karenmaxSPHSU, @Mark_McCann, @Rwilsonlowe, @KMitchinGlasgow

Contributors EL and KM led on the manuscript conceptualisation, review and editing. SP, KM, CB, RBP, RL, MM, JR, KS and RW-L contributed to drafting and revising the article. All authors assisted in revising the final draft.

Funding The research reported in this publication was supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/1, MC_UU_00022/3) and the Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU11, SPHSU14). EL is also supported by MRC Skills Development Fellowship Award (MR/S015078/1). KS and MM are also supported by a Medical Research Council Strategic Award (MC_PC_13027).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2024

The impact of self-determination theory: the moderating functions of social media (SM) use in education and affective learning engagement

- Uthman Alturki 1 &

- Ahmed Aldraiweesh 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 693 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

121 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

This study attempts to explore the relationship between the two mediator variables effective learning engagement and educational social media (SM) usage and the study’s outcome measures, which include student satisfaction and learning performance. The distribution of a self-determination theory questionnaire with external factors to 293 university students served as the primary data collection method. King Saud University used a poll to personally collect data. Partial least squares structural equation modeling was then used to examine the data and assess the model in Smart-PLS. Students’ academic success and contentment at colleges and universities seem to be positively correlated, and their active involvement in learning activities and educational use of SM. It was shown that important factors influencing affective learning participation and the instructional use of SM for teaching and learning include perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, information sharing, and collaborative learning environments. It was discovered that these connections were important. The self-determination theory provided confirmation that this model is appropriate for fostering students’ feelings of competence, autonomy, and relatedness in order to increase their affective learning involvement. This, in turn, improves students’ satisfaction and achievement in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Looking back to move forward: comparison of instructors’ and undergraduates’ retrospection on the effectiveness of online learning using the nine-outcome influencing factors

Impact of psychological safety and inclusive leadership on online learning satisfaction: the role of organizational support.

Exploring the influence of teachers’ motivating styles on college students’ agentic engagement in online learning: The mediating and suppressing effects of self-regulated learning ability

Introduction.

Numerous academics are examining students’ desire to participate in social media (SM) tools and the impact of their use on the educational environment due to the growing popularity of SM and the extensive use of these tools by students in their daily lives. Teachers are keen to grasp the educational importance of SM, even though researchers are still in the investigative stage, trying to gather definitive information about whether or not using SM platforms is suitable (Al-Adwan et al., 2021 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022a ). Nonetheless, earlier studies in the literature (Sabah, 2022 ) mainly examined the causes of SM tool acceptance or use and the ways in which important elements influence this kind of educational usage (Sayaf et al., 2022 ; Ullah et al., 2021 ). Educational SM use is the deliberate integration of SM platforms and tools into the classroom to enhance the overall pedagogical experience. This approach considers the contemporary digital landscape and leverages the SM platform’s communicative and collaborative potential to foster students’ active learning, engagement, and knowledge (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022b ; Yin & Yuan, 2021 ). Websites like blogs, wikis, discussion forums, and microblogging sites can be used to promote student participation, peer learning, and cooperative projects (Sayaf et al., 2022 ). Nevertheless, despite the potential benefits of SM use in education, a number of considerations need to be made carefully, including fostering a supportive learning environment and privacy issues (Sayaf et al., 2022 ). Most SM research in Saudi Arabia has concentrated on the motivations behind and actions connected to SM use.

According to Yin and Yuan ( 2021 ) and Sabah ( 2022 ), students’ attitudes toward using SM in a blended learning environment, like Facebook and WhatsApp, as well as their acceptance of using SM for educational purposes, have all been investigated through experimental research in a few studies. Additionally, Facebook and Twitter have been used to support student-centered learning. Previous studies have examined the role that cultural norms play in preserving social relationships on Facebook as well as the risks that excessive Facebook use poses to students’ mental health (Remedios et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, investigations into the potential educational benefits of SM platforms are still underway; numerous studies have evaluated the extent to which SM usage enhances learning (Hameed et al., 2022 ; Nti et al., 2022 ). However, because these studies ignored the particular correlations between the use of SM and learning outcomes, they were unable to deepen our understanding of these explanatory relationships. As a result, the prior literature found inconsistent findings about these platforms’ ability to improve students’ learning outcomes. A few of these studies (Alhussain et al., 2020 ), for example, found that using SM enhanced students’ academic achievement. However, other research has shown that SM use has a negative impact on academic performance (Al-Maatouk et al., 2020 ) and that students’ use of SM reduces their study time and effort. It’s noteworthy that other research has revealed SM platforms might not be advantageous for students.

According to them, these platforms have little to no impact on academic achievement (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022c ) and are improper for improving learning performance (Foroughi et al., 2022 ). The majority of this study (Alamri et al., 2020b ) has not taken into consideration the important function that mediator variables play in examining the relationship between the use of SM and satisfaction as well as learning outcomes. Few studies have explicitly examined the moderator factor (such as cyberstalking) that affects the association between academic performance and SM use (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022d ), and how, while using SM for learning, cyberbullying plays a moderating effect in the relationship between academic accomplishment and cooperative learning in higher education (Alyoussef et al., 2019 ). Understanding how and when SM use might increase or decrease results requires a sophisticated viewpoint because there are more complex links between SM use and its outcomes than merely a positive or negative influence. Actually, learning’s ability to make knowledge widely available, accessible, and flexible is what really distinguishes it from other conventional kinds of education (Han & Shin, 2016 ).

Because of these benefits, SM has drawn a sizable initial user base, particularly in the setting of higher education. In fact, because they typically possess their own mobile devices, college learners are more likely to accept and employ SM learning than students in a classroom (Al-Qaysi et al., 2021 ). Nevertheless, attracting the initial user base is just half the battle for the success of SM sites. How to retain students using SM is a crucial question that many educators and providers of SM technology are posing (Chawinga, 2017 ). While a lot of scholarly research has been done on the acceptance and use of mobile learning, most of these studies have identified the factors that led to its development from a technological standpoint (Pham & Dau, 2022 ). Perceived utility, effort expectations, and performance expectations are some of the factors that affect the early uptake of SM use in higher education (Chugh et al., 2021 ).

It has been demonstrated that increased well-being and intrinsic motivation are significantly impacted by the fulfillment of the three general psychological aims of SDT—autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000 ). Garn defines relatedness as the need to feel socially connected in a classroom environment, competence as the process of growing one’s own abilities and skills, and autonomy as the basic need to regulate one’s behavior and organize oneself according to one’s self-awareness (Garn et al., 2019 ). SDT is applied in a variety of settings, including the commercial world, the workplace, and educational institutions. According to Sun et al. ( 2019 ), it is regarded as one of the “most supported by evidence incentive theories” in use today. SDT has several uses in the field of research in education as well. The goal of SDT, a macro-level theory concerning human incentive, is to make clear the relationships that exist between motivation, growth, and well-being.

It emphasizes how important fundamental psychological requirements like relatedness, competence, and autonomy have been. The application of SDT in virtual learning environments has been the subject of numerous research investigations. According to Hsu et al.‘s 2019 study, for instance, satisfying basic mental needs enhanced self-regulated learning, which in turn was associated with higher reported knowledge transfer and greater course-end accomplishment. The significance of students’ continuous self-regulation for effective learning in an online setting was the subject of another study conducted in 2021. It achieved this by explaining the connections between students’ motivation, fundamental psychological requirements, and ongoing desire to participate in online self-regulated learning using SDT (Luo et al., 2021 ). Thus, by applying the SDT principles to create online learning that supports students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness, educators can improve students’ motivation and learning outcomes through the use of SM (Chiu, 2023 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022d ).

SDT can conduct additional studies on SM platforms by examining how intrinsic motivation as well as conduct during learning are influenced by the three fundamental psychological requirements of independence, skill, and connection (Sun et al., 2019 ). Researchers utilizing SDT also looked at how learner motivation, success, and well-being were affected by mobile learning tools (Jeno et al., 2019 ). As learners themselves, teachers make use of a range of educational resources. SDT (Jansen in de Wal et al., 2020 ) states that when a person’s basic psychological needs are met, learning actions and goals also become more obvious.

Early studies on SM and education have shown how important trust and the kind of organization are in fostering knowledge sharing (Singh et al., 2019 ; Ahmad & Huvila, 2019 ). Mutambik et al. ( 2022 ) state that people regard collaborative learning highly. SM’s function in promoting education and information sharing still has advantages and disadvantages because there is a lack of research demonstrating how SM affects information sharing in the field of education. Though self-determination theory (SDT) with affective learning involvement and educational usage of SM factors (Platts, 1972 ; Sørebø et al., 2009 ) can be used to study the basic processes by which student motivation to learn develops and how they affect SM tools, very little research has been done on these topics, especially in the post-adoption phase (Nti et al., 2022 ).

SM in higher education

Lately, lifelong learning in terms of skills has taken precedence over knowledge in higher education (Abdullah Moafa et al., 2018 ).

Cooperation abilities are highly valued by employers, which is how they are in this compilation (Raza et al., 2020 ). Considering the broad meaning of “SM,” it is not surprising that most research has focused on websites such as Facebook, Twitter, and MySpace as educational successes. As stated by Alisaiel et al. (2022c), the broadest definition of active collaborative learning is when two or more people collaborate to study or attempt to learn new. According to Stockdale and Coyne ( 2020 ), SM websites aim to facilitate various tasks for their users, such as sending and receiving emails, adding friends, creating personal profiles, joining groups, creating apps, and finding other users.

Compared to Web 1.0, which was less active and more static, Web 2.0 allows for greater user engagement, collaboration, and personalization (Tajvidi & Karami, 2021 ). It combines active collaborative learning with the use of Facebook, blogs, and YouTube, amongst other platforms, as noted in Al-Rahmi et al. ( 2021a ).

Furthermore, it has historically been challenging for faculty personnel in higher education to communicate with students effectively (Alenazy et al., 2019 ). They have access to SM technologies, which makes it possible to communicate with students quickly and create more engaging lessons. SM is used by students to raise their academic standing. Teachers and students can both use social networks to improve and expedite the teaching and learning process.