Essay on Insecurity and Self-Esteem

Insecurity drills a hole into a person’s heart, minimizes their integrity, and accumulates as plaque build up, hindering any kind of future growth. Just as any human being’s growth is stifled by the insecurity within them, the United States as a whole suffers the same from its own tremendous amount of insecurity. This lack of acknowledgement of self-worth causes a ghastly chain reaction; people tend to pursue the wrong ideals, become corrupt, and inevitably lead themselves to their own demise. Insecurity is a route to destruction, and America is speeding down that road to dissolution. The dictionary’s definition of insecurity is: “ uncertainty or anxiety about oneself; lack of confidence”("Insecurity," Oxford English …show more content…

Now, considering this aspect, one realizes how a person can not function with insecurity and low self-esteem; so then, a whole country trying to function and grow with its insecurity and low self-esteem is simply impossible. Insecurity in America exists in many forms as well as in many areas of the American culture. The main places in which insecurity permeates from are stereotyping, the media, and worst of all, condemnation by peers. With all these different types ways in which one can be provoked, it is no wonder much of America suffers from low self-esteem. Since America is a large melting-pot of cultures, unfortunately it comes with much stereotyping. Many people simply look at eachother, and based on prior situations, stereotype the person in front of them. While doing so, they don't realize how detrimental they are being to that person’s future. When one downgrades another, they not only hurt them emotionally, but hinder them from every growing as individuals. For example, in the United States , not too much time back, African Americans were constantly stereotyped as less than human . No one expected anything of them, and constantly put them down, so for that reason alone, many simply gave up, and just fell into the stereotype. If you address someone as a certain person for long enough, they will give you what you expect of them. Because of this reason, many Americans have simply given up and fallen into whatever

Scarlet Letter Integrity

Insecurity is something most people have witnessed at some point in their lives. Insecurity is the act of feeling inferior to everyone else, or frankly unconfident of oneself. A variety of people around me are able to mettle with this issue, but a small percentage aren’t. When it comes to insecurity, I am practically the queen because I just can’t seem to accept myself for who I am or have become since childhood. I have an absolute hatred towards for myself, and whenever the opportunity is present, I find something to criticize my myself for. The act is almost identical to being the most judgmental person in the world, with the exception that you are aiming the insults at yourself instead of others. I always have to insult myself and can never accept the actions I have made. There is always something wrong, something I could have done better or a detail I misplaced when doing something of great importance. I feel myself lacking some sort of greater potential that will lead me to perfection. The ironic part? I know that perfection is an impossible feat but I was raised so strictly on the idea of reaching perfection that avoiding the achievement is not an option. Thus, this is my greatest flaw and I am recognized through society as the person who can not stay positive or accept myself for

Self Esteem Essay

How can a person overcome depression is a common question in society. Though, what many do not consider when responding to this question is how a person's self esteem contributes to depression. Self esteem revolves around a person's feelings about themselves. If self esteem is not focused on in a person's life, it can contribute to negative feelings about oneself, which can be a continuous feeling throughout a person's life. With a low self esteem, people lose confidence in their decision making and therefore start to not believe in themselves. Thus, building a positive self esteem should be focused on in a child's adolescents because it is a time of major development in a person's life. Therefore, with a positive self esteem from a young

The Problem Of Self Esteem

Most people face self esteem problems at different levels. At some point in life people face this problem without realizing it. In the essay The Trouble with Self-Esteem written by Lauren Slater starts of by demonstrating a test. Self esteem test that determines whether you have a high self-esteem or low self-esteem. The question to be answered however is; what is the value and meaning of self-esteem? The trouble with self-esteem is that not everyone approaches it properly, taking a test or doing research based of a certain group of people is not the way to do so.

Low Self Esteem Essay

The concept of self esteem is widespread in life. When it comes to academics and extracurricular actives people associate high self esteem is necessary for success. Society makes promoting self esteem an important goal. With that in mind, it is surprising that only recently scientific literature began providing insight into the nature of development of self esteem.

Unit 11 p6 and m3

It is said that we internalise information we gain from the world and then we build it into our sense of self. In other words, when we human are praised and shown love and respect we gain high self-esteem and we forget about it and it doesn’t bother us. However, when we are cussed and something bad is said about us, we tend to think about it not forgetting it and those who experience this would have a low self-esteem. It is also said that those with low self-esteem others can increase it.

Low Self-Esteem To The 1970's

Some will argue that low self-esteem never was a time but that it’s a figment of imaginations. However, researchers have proven the increasing rate of low self-esteem. And if it is a recent issue, how come it is such a big issue. Or if it is a figment of imagination, then why do people face this problem different and why do they handle it differently?

An Army One Me Analysis

During the 60s and 70s, the revolution of the enhancement of self-esteem came into existence into the United States’ society. Jean Twenge’s article “An Army One: Me”, she discusses how the forced instilling of self-esteem, especially in small children, has caused the current generation to develop narcissistic qualities. One would presume that by the promotion of narcissism, we would inevitably discontinue the promotion of self-esteem. However, self-esteem plays a vital role in humanity’s search for

Construct Development and Scale Creation Essay

Base on the self confidence survey, we can realize that a person’s level of self confidence recognizes that she/he is responsible for the decisions that she/he makes. If a person believes they can achieve something, then they will. But low esteem will pull them down and it will be

Amee Latour's Article Analysis

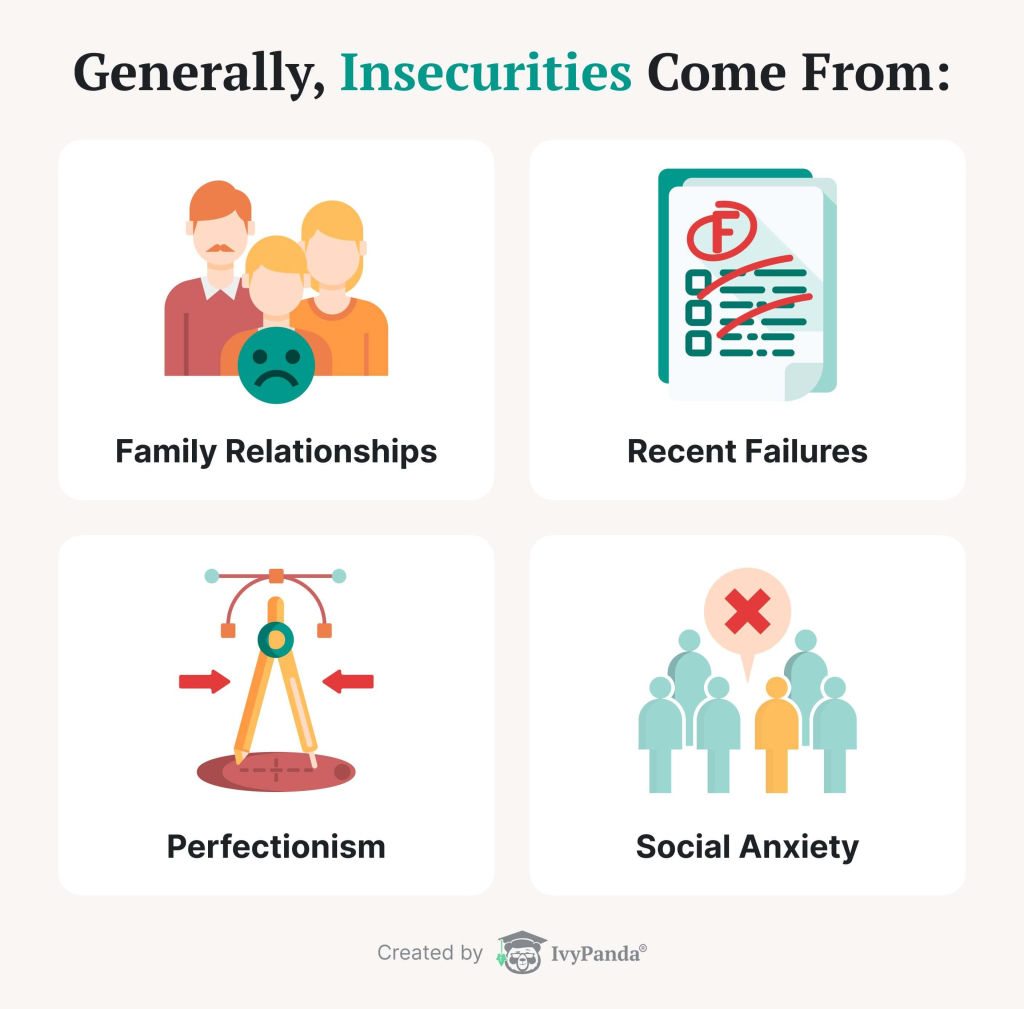

Self-esteem is essentially how you feel about yourself and how you judge your value. It is a state of mind that can be changed. These days many people are having low self-esteem issues. In this article by Amee LaTour, she has talked about what are the causes of low self-esteem. She presents her points in the form of an article. This paper will review Amee LaTour’s arguments and will assess the quality of her writing and concentrate on any zones of shortcomings in this article.

Healing The Hurt Within Analysis

Self-esteem is a highly valued attribute of human personality. However, it is less mercurial than the ups and downs associated with everyday mood changes. Due to the increasing population finding themselves within various cycles of diminishing self-worth, high self-esteem has become less common today than in the past. These cycles, the most prominent being the cycles of media, perfection, and abuse, continuously revolve around themselves and lower the esteem of those within them. The root of low self-esteem lies within reversible social and psychological cycles of cause and effect, and only with the breaking of these cycles can self-esteem be improved.

Irish American Drinking Habits in Literature and in Popular Culture: A Self-Defeating Cycle

Stereotypes are not hard to come by in popular American culture, and truly in popular cultures the world over. Human beings seem programmed to make quick and superficial judgments about anyone who is or who simply appears to be "different" or "other than" oneself, equating race, ethnicity, skin color, and/or country of origin with a set of specific attitudes, values, and behaviors that are often insultingly oversimplified and incorrect. The United States has had more than its share of struggles with accepting newcomers and dealing with minorities of all stripes, possibly due to the fact that the nation has a rich history of immense immigration that has led to higher levels of multi-ethnic and multicultural interactions and social pressures than have existed in many other nations.

Glamour In Walden

This quote also goes to both males and females in our society. Most females that I know that come to this school get insecure when they feel they are putting on a little weight or having some acne on their face. While on the other hand males that I know get insecure when they feel they are not needed or even some get insecure from not getting enough attention from someone they want attention from.

Insecurity Problem

Though it is weaker, it is still competing with my insecurity to be lens with which I view the world. In nature when two species compete to have the same niche, or position in an environment, one species goes extinct. By feeding my self-confidence, I hope to let it enjoy my perceptions. I know insecurities are like other parasites and they come from others when we are young. Hearing other people say horrible things about me caused me to nurse insecurity. Every time insecurity snarls a suspicion about a person yanking its leash is necessary to discipline the

Self-Thrubt

Self-doubt is the pinnacle of disappointment. Under the category of "disappointment", self-doubt is the main subject to where people mostly project about themselves. Some people,

My Personal Feelings of Self Worth Essay

People’s self-esteem either high or low is shaped by their life experiences. I believe a person’s self-esteem begins to take shape at an early age, with their parents being a major influence. Kind, positive, knowledgeable and caring parents help children create a positive self-image. Parents who do not feel good about themselves or others, sometimes take it out on their childern by belittling them or discouraging them. This leads the child down a path of self-doubt and eventually given the right circumstances a lower self-esteem.

Related Topics

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- United States

- The Great Gatsby

Personal Narrative Essay: Insecurity and Self-Esteem

| 📌Category: | , , , , |

| 📌Words: | 342 |

| 📌Pages: | 2 |

| 📌Published: | 13 April 2021 |

I've caught myself trying to define what 'breaking away' actually meant . This surely wasn't the first time I've pondered about it like my life depended on it , turns out it did . Being a teenager with serious self-esteem issues, the thought of breaking away from my self-depreciating ways ran around my mind quite often . I couldn't get by a single day without doubting myself and my abilities

Yes, breaking away from habits are hard but it must be given serious attention . Back sliding, thoughts about giving up, your body threatening to give away , your mind flooding with doubts and the trust you had slowly fading away - these are the steps which are inevitable when you're desperately trying to break away from a habit . I've had a firsthand experience trying to break away from the constant battles inside my mind .

Being young comes with vulnerability, naive beliefs and a whole lot of insecurities. The battles I fought with myself, the wars waging in my mind , trying to break away from how insecure I was when I made a decision was the type of 'breaking away ' I was stuck in . I was and probably still am the most lost teenager to ever live on this planet. I wake up , put on a smile which made me look friendly , decide which 'me' I would be that day and head out blindly with no sense of direction and purpose. My days were were as mundane as possible and gave off a monotonous vibe , I used to cower away from the challenges and lived in my small safety bubble .

Yes, there were times when when I had the sudden urge to change my life , random outbursts of emotions begging me to break free from my boring life .I didn't want a small change , I wanted , no , I needed a drastic Change in my life void of dreams . I realised how important it was to have a purpose in life and not waste it away . I wanted a more challenging life , the almost extinguished fire inside me stirring, waiting to be unleashed.

Related Samples

- Persuasive Essay Sample on Drug Decriminalization

- Personal Essay Example: My Amazing Winter Break

- The Importance of Napping Research Essay Example

- Essay Sample on Career in Information Systems

- Virtue and Happiness Essay Example

- Reflective Essay Sample about Hero

- Achieving Goals Essay Example

- Why Do We Enjoy Watching Rich People on TV

- Persuasive Essay Example on Teachers Pay Should Be Raised

- The Lessons I've Learned While In Quarantine Essay Example

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

What Is Healthy Self-Esteem?

Self-esteem is what we think of ourselves. When it’s positive, we have confidence and self-respect. We’re content with ourselves and our abilities, in who we are and our competence. Self-esteem is relatively stable and enduring, though it can fluctuate. Healthy self-esteem makes us resilient and hopeful about life.

Self-Esteem Impacts Everything

Self-esteem affects not only what we think, but also how we feel and behave. It and has significant ramifications for our happiness and enjoyment of life. It considerably affects events in our life, including our relationships, our work and goals, and how we care for ourselves and our children.

Although difficult events, such as a breakups , illness, or loss of income, may in the short term moderate our self-esteem, we soon rebound to think positively about ourselves and our future. Even when we fail, it doesn’t diminish our self-esteem. People with healthy self-esteem credit themselves when things go right, and when they don’t, they consider external causes and also honestly evaluate their mistakes and shortcomings. Then they improve upon them.

Healthy vs. Impaired Self-Esteem

I prefer to use the terms healthy and impaired self-esteem, rather than high and low, because narcissists and conceited individuals who appear to have high self-esteem actually don’t. Theirs is inflated, compensates for shame and insecurity, and is often unrelated to reality. Boasting is an example, because it indicates that the person is dependent on others’ opinion of them and reveals impaired rather than healthy self-esteem. Thus, healthy self-esteem requires that we’re able to honestly and a realistically assess our strengths and weaknesses. We’re not too concerned about others’ opinions of us. When we accept our flaws without judgment, our self-acceptance goes beyond self-esteem.

Impaired Self-Esteem

Impaired self-esteem negatively impacts our ability to manage adversity and life’s disappointments. All of our relationships are affected, including our relationship with ourselves. When our self-esteem is impaired, we feel insecure, compare ourselves to others, and doubt and criticize ourselves. We neither recognize our worth, nor honor and express our needs and wants. Instead, we may self-sacrifice, defer to others, or try to control them and/or their feelings toward us to feel better about ourselves. For example, we might people-please , manipulate , or devalue them, provoke jealousy , or restrict their association with others. Consciously or unconsciously, we devalue ourselves, including our positive skills and attributes, making us hyper-sensitive to criticism. We may also be afraid to try new things, because we might fail.

Symptoms of Healthy and Impaired Self-Esteem

The following chart lists symptoms that reflect healthy vs. impaired self-esteem. Remember that self-esteem varies on a continuum. It’s not black or white. You may relate to some, but not all.

| Know you’re okay | Feel not enough; always improving yourself |

| Know you have value and matter | Lack self-worth and value; feel unimportant |

| Feel competent and confident | Doubt self, feel incompetent, and afraid to risk |

| Like yourself | Judge and dislike yourself |

| Exhibit honesty and integrity | Please, hide, and agree with others |

| Trust yourself | Indecisive, ask others’ opinions |

| Accept praise | Deflect or distrust praise |

| Accept attention | Avoid, dislike attention |

| Are self-responsible; honor self | Discount feelings, wants, or needs |

| Have internal locus of control | Need others’ guidance or approval |

| Self-efficacy to pursue goals | Afraid to start and do things |

| Have self-respect | Allow abuse; put others first |

| Have self-compassion | Self-judgment, self-loathing |

| Happy for others good fortune | Envy and compare yourself to others |

| Acceptance of others | Judge others |

| Satisfied in relationships | Unhappy in relationships |

| Assertive | Defer to others, indirect and afraid to express yourself |

| Optimistic | Feel anxious and pessimistic |

| Welcome feedback | Defensive of real or perceived criticism |

The Cause of Impaired Self-Esteem

Growing up in a dysfunctional family can lead to codependency as an adult. It also weakens your self-esteem. Often you don’t have a voice. Your opinions and desires aren’t taken seriously. Parents usually have low self-esteem and are unhappy with each other. They themselves neither have nor model good relationship skills, including cooperation, healthy boundaries, assertiveness, and conflict resolution. They may be abusive, controlling, interfering, manipulative, indifferent, inconsistent, or just preoccupied. Directly or indirectly, they may shame their children’s feelings and personal traits, feelings, and needs. It’s not safe to be, to trust, and to express themselves.

Children feel insecure, anxious, and/or angry. As a result, they feel emotionally abandoned and conclude that they are at fault — not good enough to be acceptable to both parents. (They might still believe that they’re loved.) Eventually, they don’t like themselves and feel inferior or inadequate. They grow up codependent with low self-esteem and learn to hide their feelings, walk on eggshells, withdraw, and try to please or become aggressive. This reflects how toxic shame becomes internalized.

Shame runs deeper than self-esteem. It’s a profoundly painful emotion rather than a mental evaluation. Underlying toxic shame can lead to impaired or low self-esteem and other negative thoughts and feelings. It’s not just that we lack confidence, but we might believe that we’re bad, worthless, inferior, or unlovable. It creates feelings of false guilt and fear and hopelessness, at times, and feeling irredeemable. Shame is a major cause of depression and can lead to self-destructive behavior, eating disorders, addiction, and aggression.

Shame causes shame anxiety about anticipating shame in the future, usually in the form of rejection or judgment by other people. Shame anxiety makes it difficult to try new things, have intimate relationships, be spontaneous, or take risks. Sometimes, we don’t realize that it’s not others’ judgments or rejection we fear, but our failure to meet our own unrealistic standards. We judge ourselves harshly for mistakes than others would. This pattern is very self-destructive with perfectionists. Our self-judgment can paralyze us so that we’re indecisive, because our internal critic will judge us no matter what we decide!

Relationships

Our relationship with ourselves provides a template for our relationships with others. It impacts our relationship happiness. Self-esteem determines our communication style, boundaries, and our ability to be intimate. Research indicates that a partner with healthy self-esteem can positively influence his or her partner’s self-esteem, but also shows that low self-esteem portends a negative outcome for the relationship. This can become a self-reinforcing cycle of abandonment lowering self-esteem.

Impaired self-esteem hinders our ability to speak up about our wants and needs and share vulnerable feelings. This compromises honesty and intimacy. As a result of insecurity, shame, and impaired self-esteem as children, we may have developed an attachment style that, to varying degrees, is anxious or avoidant and makes intimacy challenging. We pursue or distance ourselves from our partner and are usually attracted to someone who also has an insecure attachment style.

Generally, we allow others to treat us the manner in which we believe we deserve. When we don’t respect and honor ourselves, we won’t expect to be treated with respect and might accept abuse or withholding behavior. Similarly, we may give more than we receive in our relationships and overdo at work. Our inner critic can be judgmental of others, too. When we’re critical of our partner or highly defensive, it makes it difficult to problem-solve. Insecure self-esteem can also make us suspicious, needy, or demanding of our partner.

Raising Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is generally determined by our teens. Some of us struggle all our lives with impaired self-esteem and even the resulting depression. But we can change and build healthy self-esteem. Raising self-esteem means getting to know and love yourself — building a relationship, as you would with a friend — and becoming your own best friend. This takes attentive listening, quiet time, and commitment. The alternative is to be lost at sea, continually trying to prove or improve yourself or win someone’s love, while never feeling truly lovable or enough — like something is missing.

It’s difficult to get outside our own thoughts and beliefs to see ourselves from another perspective. Therapy can help us change how we think, act, and what we believe. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to raise self-esteem. It’s more powerful when combined with meditation that increases self-awareness. Some things you can do:

- Recognize the Signs. Be able to spot clues that your self-esteem needs uplifting. Many people think they have good self-esteem. They may be talented, beautiful, or successful, but still lack self-esteem.

- Root Out False Beliefs. Learn how to identify and deprogram false beliefs and behaviors you want to change and those you want to implement.

- Identify Cognitive Distortions. Impaired self-esteem can cause us to skew and distort reality. Learn to identify and challenge your cognitive distortions .

- Journal. Journaling has been shown to elevate mood and decrease depression. Keeping a journal can also help you to monitor your interactions with others and your negative self-talk.

- Heal Toxic Shame. If you believe you suffer from codependency and shame, learn more about it and do the exercises in Conquering Shame and Codependency .

Last medically reviewed on May 10, 2019

Read this next

If you find yourself saying 'I hate people', knowing why you feel this way may help you address how you feel. It can also help you build tolerance for…

Main character syndrome is a term that originated on social media platforms. It describes someone who believes they're a protagonist at the expense of…

Compartmentalization is a psychological process that can help you separate certain thoughts from others. Here are 4 ways to compartmentalize.

Body-focused repetitive behaviors are repetitive behaviors, like hair-pulling, nail-biting or skin-picking. If you’re living with BFRBs, support is…

Temper tantrums are outbursts of intense anger or frustration that children aged 1 to 4 often have. Identifying the signs can help you deal with these…

Biting your nails can indicate unaddressed psychological or emotional issues. If you have a habit of biting your nails, you're not alone. Help is…

Excessive yawning can occur for many reasons, such as fatigue, sleep issues, stress, or serious medical conditions. But treatment is available to help…

Dermatophagia is a condition often linked with OCD, where people chew and bite their skin. More research is needed, but help is available to help you…

The inability to ejaculate or taking a long time to ejaculate is a sexual dysfunction that can cause distress. But treatment is available to help…

Building empathy and helping others are a few ways you can be a better person. But becoming a “better” person doesn’t mean you’re a “bad” person.

Essay on Self Esteem

Students are often asked to write an essay on Self Esteem in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Understanding self-esteem.

Self-esteem is the opinion we have about ourselves. It’s about how much we value and respect ourselves. High self-esteem means you think highly of yourself, while low self-esteem means you don’t.

Importance of Self-Esteem

Building self-esteem.

Building self-esteem requires positive self-talk, self-acceptance, and self-love. It’s about focusing on your strengths, forgiving your mistakes, and celebrating your achievements.

250 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Introduction.

Self-esteem, a fundamental concept in psychology, refers to an individual’s overall subjective emotional evaluation of their own worth. It encompasses beliefs about oneself and emotional states, such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. It is a critical aspect of personal identity, shaping our perception of the world and our place within it.

The Dual Facet of Self-Esteem

Impact of self-esteem.

High self-esteem can lead to positive outcomes. It encourages risk-taking, resilience, and optimism, fostering success in various life domains. Conversely, low self-esteem can result in fear of failure, social anxiety, and susceptibility to mental health issues like depression. Thus, it’s crucial to nurture self-esteem for psychological well-being.

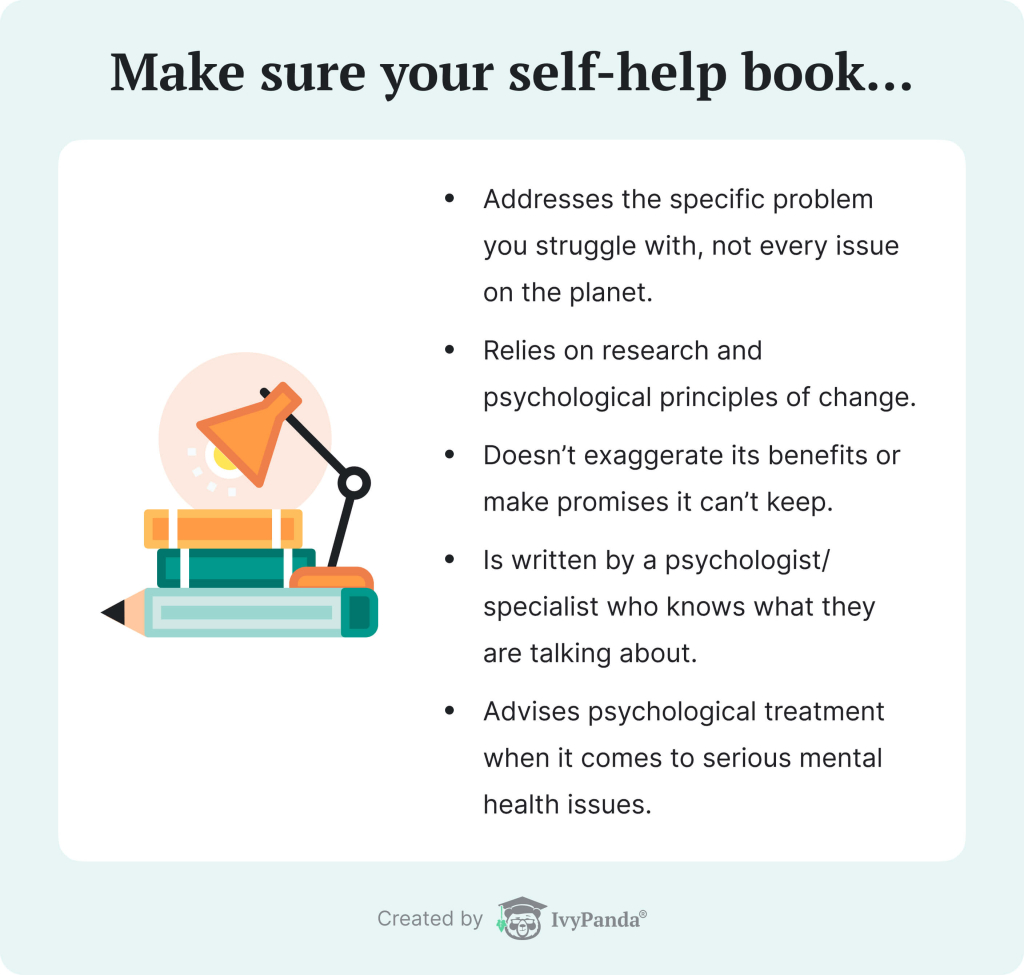

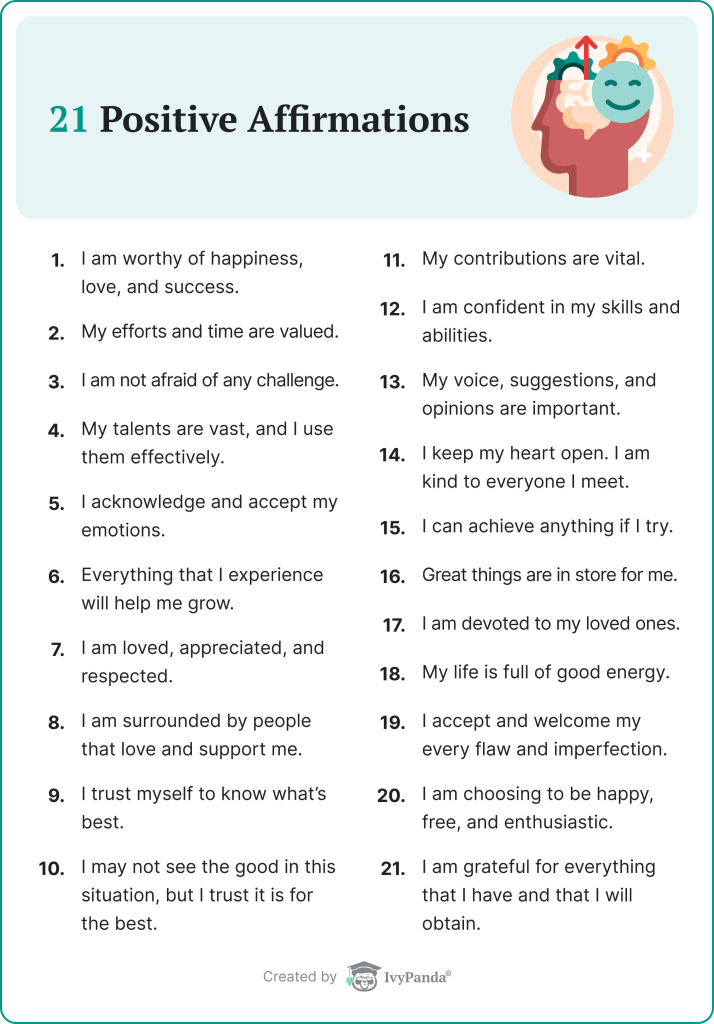

Building self-esteem involves recognizing one’s strengths and weaknesses and accepting them. It requires self-compassion and challenging negative self-perceptions. Positive affirmations, setting and achieving goals, and maintaining healthy relationships can all contribute to enhancing self-esteem.

In conclusion, self-esteem is a complex, multifaceted construct that significantly influences our lives. It is not static and can be improved with conscious effort. Understanding and nurturing our self-esteem is vital for achieving personal growth and leading a fulfilling life.

500 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Self-esteem, a fundamental aspect of psychological health, is the overall subjective emotional evaluation of one’s self-worth. It is a judgment of oneself as well as an attitude toward the self. The importance of self-esteem lies in the fact that it concerns our perceptions and beliefs about ourselves, which can shape our experiences and actions.

The Two Types of Self-esteem

Self-esteem can be classified into two types: high and low. High self-esteem indicates a highly favorable impression of oneself, whereas low self-esteem reflects a negative view. People with high self-esteem generally feel good about themselves and value their worth, while those with low self-esteem usually harbor negative feelings about themselves, often leading to feelings of inadequacy, incompetence, and unlovability.

Factors Influencing Self-esteem

Impact of self-esteem on life.

Self-esteem significantly impacts individuals’ mental health, relationships, and overall well-being. High self-esteem can lead to positive outcomes, such as better stress management, resilience, and life satisfaction. On the other hand, low self-esteem is associated with mental health issues like depression and anxiety. It can also lead to poor academic and job performance, problematic relationships, and increased vulnerability to drug and alcohol abuse.

Improving Self-esteem

Improving self-esteem requires a multifaceted approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapies can help individuals challenge their negative beliefs about themselves and develop healthier thought patterns. Regular physical activity, healthy eating, and adequate sleep can also boost self-esteem by improving physical health. Furthermore, positive social interactions and relationships can enhance self-esteem by providing emotional support and validation. Lastly, self-compassion and self-care practices can foster a more positive self-image and promote higher self-esteem.

In conclusion, self-esteem is a critical component of our psychological well-being, influencing our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It is shaped by various factors and can significantly impact our lives. However, it’s not a fixed attribute, and with the right strategies and support, individuals can improve their self-esteem, leading to better mental health, relationships, and overall quality of life. Therefore, understanding and fostering self-esteem is essential for personal growth and development.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, identity development and the sources of negative self-esteem, outcomes of poor self-esteem, mechanisms linking self-esteem and health behavior, examples of school health promotion programs that foster self-esteem, self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Michal (Michelle) Mann, Clemens M. H. Hosman, Herman P. Schaalma, Nanne K. de Vries, Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion, Health Education Research , Volume 19, Issue 4, August 2004, Pages 357–372, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg041

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Self-evaluation is crucial to mental and social well-being. It influences aspirations, personal goals and interaction with others. This paper stresses the importance of self-esteem as a protective factor and a non-specific risk factor in physical and mental health. Evidence is presented illustrating that self-esteem can lead to better health and social behavior, and that poor self-esteem is associated with a broad range of mental disorders and social problems, both internalizing problems (e.g. depression, suicidal tendencies, eating disorders and anxiety) and externalizing problems (e.g. violence and substance abuse). We discuss the dynamics of self-esteem in these relations. It is argued that an understanding of the development of self-esteem, its outcomes, and its active protection and promotion are critical to the improvement of both mental and physical health. The consequences for theory development, program development and health education research are addressed. Focusing on self-esteem is considered a core element of mental health promotion and a fruitful basis for a broad-spectrum approach.

The most basic task for one's mental, emotional and social health, which begins in infancy and continues until one dies, is the construction of his/her positive self-esteem. [( Macdonald, 1994 ), p. 19]

Self-concept is defined as the sum of an individual's beliefs and knowledge about his/her personal attributes and qualities. It is classed as a cognitive schema that organizes abstract and concrete views about the self, and controls the processing of self-relevant information ( Markus, 1977 ; Kihlstrom and Cantor, 1983 ). Other concepts, such as self-image and self-perception, are equivalents to self-concept. Self-esteem is the evaluative and affective dimension of the self-concept, and is considered as equivalent to self-regard, self-estimation and self-worth ( Harter, 1999 ). It refers to a person's global appraisal of his/her positive or negative value, based on the scores a person gives him/herself in different roles and domains of life ( Rogers, 1981 ; Markus and Nurius, 1986 ). Positive self-esteem is not only seen as a basic feature of mental health, but also as a protective factor that contributes to better health and positive social behavior through its role as a buffer against the impact of negative influences. It is seen to actively promote healthy functioning as reflected in life aspects such as achievements, success, satisfaction, and the ability to cope with diseases like cancer and heart disease. Conversely, an unstable self-concept and poor self-esteem can play a critical role in the development of an array of mental disorders and social problems, such as depression, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, anxiety, violence, substance abuse and high-risk behaviors. These conditions not only result in a high degree of personal suffering, but also impose a considerable burden on society. As will be shown, prospective studies have highlighted low self-esteem as a risk factor and positive self-esteem as a protective factor. To summarize, self-esteem is considered as an influential factor both in physical and mental health, and therefore should be an important focus in health promotion; in particular, mental health promotion.

Health promotion refers to the process of enabling people to increase control over and improve their own health ( WHO, 1986 ). Subjective control as well as subjective health, each aspects of the self, are considered as significant elements of the health concept. Recognizing the existence of different views on the concept of mental health promotion, Sartorius (Sartorius, 1998), the former WHO Director of Mental Health, preferred to define it as a means by which individuals, groups or large populations can enhance their competence, self-esteem and sense of well-being. This view is supported by Tudor (Tudor, 1996) in his monograph on mental health promotion, where he presents self-concept and self-esteem as two of the core elements of mental health, and therefore as an important focus of mental health promotion.

This article aims to clarify how self-esteem is related to physical and mental health, both empirically and theoretically, and to offer arguments for enhancing self-esteem and self-concept as a major aspect of health promotion, mental health promotion and a ‘Broad-Spectrum Approach’ (BSA) in prevention.

The first section presents a review of the empirical evidence on the consequences of high and low self-esteem in the domains of mental health, health and social outcomes. The section also addresses the bi-directional nature of the relationship between self-esteem and mental health. The second section discusses the role of self-esteem in health promotion from a theoretical perspective. How are differentiations within the self-concept related to self-esteem and mental health? How does self-esteem relate to the currently prevailing theories in the field of health promotion and prevention? What are the mechanisms that link self-esteem to health and social outcomes? Several theories used in health promotion or prevention offer insight into such mechanisms. We discuss the role of positive self-esteem as a protective factor in the context of stressors, the developmental role of negative self-esteem in mental and social problems, and the role of self-esteem in models of health behavior. Finally, implications for designing a health-promotion strategy that could generate broad-spectrum outcomes through addressing common risk factors such as self-esteem are discussed. In this context, schools are considered an ideal setting for such broad-spectrum interventions. Some examples are offered of school programs that have successfully contributed to the enhancement of self-esteem, and the prevention of mental and social problems.

Self-esteem and mental well-being

Empirical studies over the last 15 years indicate that self-esteem is an important psychological factor contributing to health and quality of life ( Evans, 1997 ). Recently, several studies have shown that subjective well-being significantly correlates with high self-esteem, and that self-esteem shares significant variance in both mental well-being and happiness ( Zimmerman, 2000 ). Self-esteem has been found to be the most dominant and powerful predictor of happiness ( Furnham and Cheng, 2000 ). Indeed, while low self-esteem leads to maladjustment, positive self-esteem, internal standards and aspirations actively seem to contribute to ‘well-being’ ( Garmezy, 1984 ; Glick and Zigler, 1992 ). According to Tudor (Tudor, 1996), self-concept, identity and self-esteem are among the key elements of mental health.

Self-esteem, academic achievements and job satisfaction

The relationship between self-esteem and academic achievement is reported in a large number of studies ( Marsh and Yeung, 1997 ; Filozof et al. , 1998 ; Hay et al. , 1998 ). In the critical childhood years, positive feelings of self-esteem have been shown to increase children's confidence and success at school ( Coopersmith, 1967 ), with positive self-esteem being a predicting factor for academic success, e.g. reading ability ( Markus and Nurius, 1986 ). Results of a longitudinal study among elementary school children indicate that children with high self-esteem have higher cognitive aptitudes ( Adams, 1996 ). Furthermore, research has revealed that core self-evaluations measured in childhood and in early adulthood are linked to job satisfaction in middle age ( Judge et al. , 2000 ).

Self-esteem and coping with stress in combination with coping with physical disease

The protective nature of self-esteem is particularly evident in studies examining stress and/or physical disease in which self-esteem is shown to safeguard the individual from fear and uncertainty. This is reflected in observations of chronically ill individuals. It has been found that a greater feeling of mastery, efficacy and high self-esteem, in combination with having a partner and many close relationships, all have direct protective effects on the development of depressive symptoms in the chronically ill ( Penninx et al. , 1998 ). Self-esteem has also been shown to enhance an individual's ability to cope with disease and post-operative survival. Research on pre-transplant psychological variables and survival after bone marrow transplantation ( Broers et al. , 1998 ) indicates that high self-esteem prior to surgery is related to longer survival. Chang and Mackenzie ( Chang and Mackenzie, 1998 ) found that the level of self-esteem was a consistent factor in the prediction of the functional outcome of a patient after a stroke.

To conclude, positive self-esteem is associated with mental well-being, adjustment, happiness, success and satisfaction. It is also associated with recovery after severe diseases.

The evolving nature of self-esteem was conceptualized by Erikson ( Erikson, 1968 ) in his theory on the stages of psychosocial development in children, adolescents and adults. According to Erikson, individuals are occupied with their self-esteem and self-concept as long as the process of crystallization of identity continues. If this process is not negotiated successfully, the individual remains confused, not knowing who (s)he really is. Identity problems, such as unclear identity, diffused identity and foreclosure (an identity status based on whether or not adolescents made firm commitments in life. Persons classified as ‘foreclosed’ have made future commitments without ever experiencing the ‘crises’ of deciding what really suits them best), together with low self-esteem, can be the cause and the core of many mental and social problems ( Marcia et al. , 1993 ).

The development of self-esteem during childhood and adolescence depends on a wide variety of intra-individual and social factors. Approval and support, especially from parents and peers, and self-perceived competence in domains of importance are the main determinants of self-esteem [for a review, see ( Harter, 1999 )]. Attachment and unconditional parental support are critical during the phases of self-development. This is a reciprocal process, as individuals with positive self-esteem can better internalize the positive view of significant others. For instance, in their prospective study among young adolescents, Garber and Flynn ( Garber and Flynn, 2001 ) found that negative self-worth develops as an outcome of low maternal acceptance, a maternal history of depression and exposure to negative interpersonal contexts, such as negative parenting practices, early history of child maltreatment, negative feedback from significant others on one's competence, and family discord and disruption.

Other sources of negative self-esteem are discrepancies between competing aspects of the self, such as between the ideal and the real self, especially in domains of importance. The larger the discrepancy between the value a child assigns to a certain competence area and the perceived self-competence in that area, the lower the feeling of self-esteem ( Harter, 1999 ). Furthermore, discrepancies can exist between the self as seen by oneself and the self as seen by significant others. As implied by Harter ( Harter, 1999 ), this could refer to contrasts that might exist between self-perceived competencies and the lack of approval or support by parents or peers.

Finally, negative and positive feelings of self-worth could be the result of a cognitive, inferential process, in which children observe and evaluate their own behaviors and competencies in specific domains (self-efficacy). The poorer they evaluate their competencies, especially in comparison to those of their peers or to the standards of significant others, the more negative their self-esteem. Such self-monitoring processes can be negatively or positively biased by a learned tendency to negative or positive thinking ( Seligman et al. , 1995 ).

The outcomes of negative self-esteem can be manifold. Poor self-esteem can result in a cascade of diminishing self-appreciation, creating self-defeating attitudes, psychiatric vulnerability, social problems or risk behaviors. The empirical literature highlights the negative outcomes of low self-esteem. However, in several studies there is a lack of clarity regarding causal relations between self-esteem and problems or disorders ( Flay and Ordway, 2001 ). This is an important observation, as there is reason to believe that self-esteem should be examined not only as a cause, but also as a consequence of problem behavior. For example, on the one hand, children could have a negative view about themselves and that might lead to depressive feelings. On the other hand, depression or lack of efficient functioning could lead to feeling bad, which might decrease self-esteem. Although the directionality can work both ways, this article concentrates on the evidence for self-esteem as a potential risk factor for mental and social outcomes. Three clusters of outcomes can be differentiated. The first are mental disorders with internalizing characteristics, such as depression, eating disorders and anxiety. The second are poor social outcomes with externalizing characteristics including aggressive behavior, violence and educational exclusion. The third is risky health behavior such as drug abuse and not using condoms.

Self-esteem and internalizing mental disorders

Self-esteem plays a significant role in the development of a variety of mental disorders. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV), negative or unstable self-perceptions are a key component in the diagnostic criteria of major depressive disorders, manic and hypomanic episodes, dysthymic disorders, dissociative disorders, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and in personality disorders, such as borderline, narcissistic and avoidant behavior. Negative self-esteem is also found to be a risk factor, leading to maladjustment and even escapism. Lacking trust in themselves, individuals become unable to handle daily problems which, in turn, reduces the ability to achieve maximum potential. This could lead to an alarming deterioration in physical and mental well-being. A decline in mental health could result in internalizing problem behavior such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders. The outcomes of low self-esteem for these disorders are elaborated below.

Depressed moods, depression and suicidal tendencies

The clinical literature suggests that low self-esteem is related to depressed moods ( Patterson and Capaldi, 1992 ), depressive disorders ( Rice et al. , 1998 ; Dori and Overholser, 1999 ), hopelessness, suicidal tendencies and attempted suicide ( Overholser et al. , 1995 ). Correlational studies have consistently shown a significant negative relationship between self-esteem and depression ( Beck et al. , 1990 ; Patton, 1991 ). Campbell et al. ( Campbell et al. , 1991 ) found individual appraisal of events to be clearly related to their self-esteem. Low self-esteem subjects rated their daily events as less positive and negative life events as being more personally important than high self-esteem subjects. Individuals with high self-esteem made more stable and global internal attributions for positive events than for negative events, leading to the reinforcement of their positive self-image. Subjects low in self-esteem, however, were more likely to associate negative events to stable and global internal attributions, and positive events to external factors and luck ( Campbell et al. , 1991 ). There is a growing body of evidence that individuals with low self-esteem more often report a depressed state, and that there is a link between dimensions of attributional style, self-esteem and depression ( Abramson et al. , 1989 ; Hammen and Goodman-Brown, 1990 ).

Some indications of the causal role of self-esteem result from prospective studies. In longitudinal studies, low self-esteem during childhood ( Reinherz et al. , 1993 ), adolescence ( Teri, 1982 ) and early adulthood ( Wilhelm et al. , 1999 ) was identified as a crucial predictor of depression later in life. Shin ( Shin, 1993 ) found that when cumulative stress, social support and self-esteem were introduced subsequently in regression analysis, of the latter two, only self-esteem accounted for significant additional variance in depression. In addition, Brown et al. ( Brown et al. , 1990 ) showed that positive self-esteem, although closely associated with inadequate social support, plays a role as a buffer factor. There appears to be a pathway from not living up to personal standards, to low self-esteem and to being depressed ( Harter, 1986 , 1990 ; Higgins, 1987 , 1989 ; Baumeister, 1990 ). Alternatively, another study indicated that when examining the role of life events and difficulties, it was found that total level of stress interacted with low self-esteem in predicting depression, whereas self-esteem alone made no direct contribution ( Miller et al. , 1989 ). To conclude, results of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that low self-esteem is predictive of depression.

The potentially detrimental impact of low self-esteem in depressive disorders stresses the significance of Seligman's recent work on ‘positive psychology’. His research indicates that teaching children to challenge their pessimistic thoughts whilst increasing positive subjective thinking (and bolstering self-esteem) can reduce the risk of pathologies such as depression ( Seligman, 1995 ; Seligman et al. , 1995 ; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ).

Other internalizing disorders

Although low self-esteem is most frequently associated with depression, a relationship has also been found with other internalizing disorders, such as anxiety and eating disorders. Research results indicate that self-esteem is inversely correlated with anxiety and other signs of psychological and physical distress ( Beck et al. , 2001 ). For example, Ginsburg et al. ( Ginsburg et al. , 1998 ) observed a low level of self-esteem in highly socially anxious children. Self-esteem was shown to serve the fundamental psychological function of buffering anxiety, with the pursuit of self-esteem as a defensive avoidance tool against basic human fears. This mechanism of defense has become evident in research with primary ( Ginsburg et al. , 1998 ) and secondary school children ( Fickova, 1999 ). In addition, empirical studies have shown that bolstering self-esteem in adults reduces anxiety ( Solomon et al. , 2000 ).

The critical role of self-esteem during school years is clearly reflected in studies on eating disorders. At this stage in life, weight, body shape and dieting behavior become intertwined with identity. Researchers have reported low self-esteem as a risk factor in the development of eating disorders in female school children and adolescents ( Fisher et al. , 1994 ; Smolak et al. , 1996 ; Shisslak et al. , 1998 ), as did prospective studies ( Vohs et al. , 2001 ). Low self-esteem also seems predictive of the poor outcome of treatment in such disorders, as has been found in a recent 4-year prospective follow-up study among adolescent in-patients with bulimic characteristics ( van der Ham et al. , 1998 ). The significant influence of self-esteem on body image has led to programs in which the promotion of self-esteem is used as a main preventive tool in eating disorders ( St Jeor, 1993 ; Vickers, 1993 ; Scarano et al. , 1994 ).

To sum up, there is a systematic relation between self-esteem and internalizing problem behavior. Moreover, there is enough prospective evidence to suggest that poor self-esteem might contribute to deterioration of internalizing problem behavior while improvement of self-esteem could prevent such deterioration.

Self-esteem, externalizing problems and other poor social outcomes

For more than two decades, scientists have studied the relationship between self-esteem and externalizing problem behaviors, such as aggression, violence, youth delinquency and dropping out of school. The outcomes of self-esteem for these disorders are described below.

Violence and aggressive behavior

While the causes of such behaviors are multiple and complex, many researchers have identified self-esteem as a critical factor in crime prevention, rehabilitation and behavioral change ( Kressly, 1994 ; Gilbert, 1995 ). In a recent longitudinal questionnaire study among high-school adolescents, low self-esteem was one of the key risk factors for problem behavior ( Jessor et al. , 1998 ).

Recent studies confirm that high self-esteem is significantly associated with less violence ( Fleming et al. , 1999 ; Horowitz, 1999 ), while a lack of self-esteem significantly increases the risk of violence and gang membership ( Schoen, 1999 ). Results of a nationwide study of bullying behavior in Ireland show that children who were involved in bullying as either bullies, victims or both had significantly lower self-esteem than other children ( Schoen, 1999 ). Adolescents with low self-esteem were found to be more vulnerable to delinquent behavior. Interestingly, delinquency was positively associated with inflated self-esteem among these adolescents after performing delinquent behavior ( Schoen, 1999 ). According to Kaplan's self-derogation theory of delinquency (Kaplan, 1975), involvement in delinquent behavior with delinquent peers can increase children's self-esteem and sense of belonging. It was also found that individuals with extremely high levels of self-esteem and narcissism show high tendencies to express anger and aggression ( Baumeister et al. , 2000 ). To conclude, positive self-esteem is associated with less aggressive behavior. Although most studies in the field of aggressive behavior, violence and delinquency are correlational, there is some prospective evidence that low self-esteem is a risk factor in the development of problem behavior. Interestingly, low self-esteem as well as high and inflated self-esteem are both associated with the development of aggressive symptoms.

School dropout

Dropping out from the educational system could also reflect rebellion or antisocial behavior resulting from identity diffusion (an identity status based on whether or not adolescents made firm commitments in life. Adolescents classified as ‘diffuse’ have not yet thought about identity issues or, having thought about them, have failed to make any firm future oriented commitments). For instance, Muha ( Muha, 1991 ) has shown that while self-image and self-esteem contribute to competent functioning in childhood and adolescence, low self-esteem can lead to problems in social functioning and school dropout. The social consequences of such problem behaviors may be considerable for both the individual and the wider community. Several prevention programs have reduced the dropout rate of students at risk ( Alice, 1993 ; Andrews, 1999 ). All these programs emphasize self-esteem as a crucial element in dropout prevention.

Self-esteem and risk behavior

The impact of self-esteem is also evident in risk behavior and physical health. In a longitudinal study, Rouse ( Rouse, 1998 ) observed that resilient adolescents had higher self-esteem than their non-resilient peers and that they were less likely to initiate a variety of risk behaviors. Positive self-esteem is considered as a protective factor against substance abuse. Adolescents with more positive self-concepts are less likely to use alcohol or drugs ( Carvajal et al. , 1998 ), while those suffering with low self-esteem are at a higher risk for drug and alcohol abuse, and tobacco use ( Crump et al. , 1997 ; Jones and Heaven, 1998 ). Carvajal et al. ( Carvajal et al. , 1998 ) showed that optimism, hope and positive self-esteem are determinants of avoiding substance abuse by adolescents, mediated by attitudes, perceived norms and perceived behavioral control. Although many studies support the finding that improving self-esteem is an important component of substance abuse prevention ( Devlin, 1995 ; Rodney et al. , 1996 ), some studies found no support for the association between self-esteem and heavy alcohol use ( Poikolainen et al. , 2001 ).

Empirical evidence suggests that positive self-esteem can also lead to behavior which is protective against contracting AIDS, while low self-esteem contributes to vulnerability to HIV/AIDS ( Rolf and Johnson, 1992 ; Somali et al. , 2001 ). The risk level increases in cases where subjects have low self-esteem and where their behavior reflects efforts to be accepted by others or to gain attention, either positively or negatively ( Reston, 1991 ). Lower self-esteem was also related to sexual risk-taking and needle sharing among homeless ethnic-minority women recovering from drug addiction ( Nyamathi, 1991 ). Abel ( Abel, 1998 ) observed that single females whose partners did not use condoms had lower self-esteem than single females whose partners did use condoms. In a study of gay and/or bisexual men, low self-esteem proved to be one of the factors that made it difficult to reduce sexual risk behavior ( Paul et al. , 1993 ).

To summarize, the literature reveals a number of studies showing beneficial outcomes of positive self-esteem, and conversely, negative outcomes of poor self-esteem, especially in adolescents. Prospective studies and intervention studies have shown that self-esteem can be a causal factor in depression, anxiety, eating disorders, delinquency, school dropout, risk behavior, social functioning, academic success and satisfaction. However, the cross-sectional character of many other studies does not exclude that low self-esteem can also be considered as an important consequence of such disorders and behavioral problems.

To assess the implications of these findings for mental health promotion and preventive interventions, more insight is needed into the antecedents of poor self-esteem, and the mechanisms that link self-esteem to mental, physical and social outcomes.

What are the mechanisms that link self-esteem to health and social outcomes? Several theories used in health promotion or prevention offer insight into such mechanisms. In this section we discuss the role of positive self-esteem as a protective factor in the context of stressors, the developmental role of negative self-esteem in mental and social problems, and the role of self-esteem in models of health behavior.

Positive thinking about oneself as a protective factor in the context of stressors

People have a need to think positively about themselves, to defend and to improve their positive self-esteem, and even to overestimate themselves. Self-esteem represents a motivational force that influences perceptions and coping behavior. In the context of negative messages and stressors, positive self-esteem can have various protective functions.

Research on optimism confirms that a somewhat exaggerated sense of self-worth facilitates mastery, leading to better mental health ( Seligman, 1995 ). Evidence suggests that positive self-evaluations, exaggerated perception of control or mastery and unrealistic optimism are all characteristic of normal human thought, and that certain delusions may contribute to mental health and well-being ( Taylor and Brown, 1988 ). The mentally healthy person appears to have the capacity to distort reality in a direction that protects and enhances self-esteem. Conversely, individuals who are moderately depressed or low in self-esteem consistently display an absence of such enhancing delusions. Self-esteem could thus be said to serve as a defense mechanism that promotes well-being by protecting internal balance. Jahoda ( Jahoda, 1958 ) also included the ‘adequate perception of reality’ as a basic element of mental health. The degree of such a defense, however, has its limitations. The beneficial effect witnessed in reasonably well-balanced individuals becomes invalid in cases of extreme self-esteem and significant distortions of the self-concept. Seligman ( Seligman, 1995 ) claimed that optimism should not be based on unrealistic or heavily biased perceptions.

Viewing yourself positively can also be regarded as a very important psychological resource for coping. We include in this category those general and specific beliefs that serve as a basis for hope and that sustain coping efforts in the face of the most adverse condition… Hope can exist only when such beliefs make a positive outcome seem possible, if not probable. [( Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ), p. 159]

Incidence = organic causes and stressors/competence, coping skills, self-esteem and social support

Identity, self-esteem, and the development of externalizing and internalizing problems

Erikson's ( Erikson, 1965 , 1968 ) theory on the stages of psychosocial development in children, adolescents, and adults and Herbert's flow chart ( Herbert, 1987 ) focus on the vicissitudes of identity and the development of unhealthy mental and social problems. According to these theories, when a person is enduringly confused about his/her own identity, he/she may possess an inherent lack of self-reassurance which results in either a low level of self-esteem or in unstable self-esteem and feelings of insecurity. However, low self-esteem—likewise inflated self-esteem—can also lead to identity problems. Under circumstances of insecurity and low self-esteem, the individual evolves in one of two ways: he/she takes the active escape route or the passive avoidance route ( Herbert, 1987 ). The escape route is associated with externalizing behaviors: aggressive behavior, violence and school dropout, the seeking of reassurance in others through high-risk behavior, premature relationships, cults or gangs. Reassurance and security may also be sought through drugs, alcohol or food. The passive avoidance route is associated with internalizing factors: feelings of despair and depression. Extreme avoidance may even result in suicidal behavior.

Whether identity and self-esteem problems express themselves following the externalizing active escape route or the internalizing passive avoidance route is dependent on personality characteristics and circumstances, life events and social antecedents (e.g. gender and parental support) ( Hebert, 1987 ). Recent studies consistently show gender differences regarding externalizing and internalizing behaviors among others in a context of low self-esteem ( Block and Gjerde, 1986 ; Rolf et al. , 1990 ; Harter, 1999 ; Benjet and Hernandez-Guzman, 2001 ). Girls are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than boys; boys are more likely to have externalizing symptoms. Moreover, according to Harter ( Harter, 1999 ), in recent studies girls appear to be better than boys in positive self-evaluation in the domain of behavioral conduct. Self-perceived behavioral conduct is assessed as the individual view on how well behaved he/she is and how he/she views his/her behavior in accordance with social expectations ( Harter, 1999 ). Negative self-perceived behavioral conduct is also found to be an important factor in mediating externalizing problems ( Reda-Norton, 1995 ; Hoffman, 1999 ).

The internalization of parental approval or disapproval is critical during childhood and adolescence. Studies have identified parents' and peers' supportive reactions (e.g. involvement, positive reinforcement, and acceptance) as crucial determinants of children's self-esteem and adjustment ( Shadmon, 1998 ). In contrast to secure, harmonious parent–child relationships, poor family relationships are associated with internalizing problems and depression ( Kashubeck and Christensen, 1993 ; Oliver and Paull, 1995 ).

Self-esteem in health behavior models

Self-esteem also plays a role in current cognitive models of health behavior. Health education research based on the Theory of Planned Behavior ( Ajzen, 1991 ) has confirmed the role of self-efficacy as a behavioral determinant ( Godin and Kok, 1996 ). Self-efficacy refers to the subjective evaluation of control over a specific behavior. While self-concepts and their evaluations could be related to specific behavioral domains, self-esteem is usually defined as a more generic attitude towards the self. One can have high self-efficacy for a specific task or behavior, while one has a negative evaluation of self-worth and vice versa. Nevertheless, both concepts are frequently intertwined since people often try to develop self-efficacy in activities that give them self-worth ( Strecher et al. , 1986 ). Self-efficacy and self-esteem are therefore not identical, but nevertheless related. The development of self-efficacy in behavioral domains of importance can contribute to positive self-esteem. On the other hand, the levels of self-esteem and self-confidence can influence self-efficacy, as is assumed in stress and coping theories.

The Attitude–Social influence–self-Efficacy (ASE) model ( De Vries and Mudde, 1998 ; De Vries et al. , 1988a ) and the Theory of Triadic Influence (TTI) ( Flay and Petraitis, 1994 ) are recent theories that provide a broad perspective on health behavior. These theories include distal factors that influence proximal behavioral determinants ( De Vries et al. , 1998b ) and specify more distal streams of influence for each of the three core determinants in the Planned Behavior Model ( Azjen, 1991 ) (attitudes, self-efficacy and social normative beliefs). Each of these behavioral determinants is assumed to be moderated by several distal factors, including self-esteem and mental disorders.

The TTI regards self-esteem in the same sense as the ASE, as a distal factor. According to this theory, self-efficacy is influenced by personality characteristics, especially the ‘sense of self’, which includes self-integration, self-image and self-esteem ( Flay and Petraitis, 1994 ).

The Precede–Proceed model of Green and Kreuter (Green and Kreuter, 1991) for the planning of health education and health promotion also recognizes the role of self-esteem. The model directs health educators to specify characteristics of health problems, and to take multiple determinants of health and health-related behavior into account. It integrates an epidemiological, behavioral and environmental approach. The staged Precede–Proceed framework supports health educators in identifying and influencing the multiple factors that shape health status, and evaluating the changes produced by interventions. Self-esteem plays a role in the first and fourth phase of the Precede–Proceed model, as an outcome variable and as a determinant. The initial phase of social diagnosis, analyses the quality of life of the target population. Green and Kreuter [(Green and Kreuter, 1991), p. 27] present self-esteem as one of the outcomes of health behavior and health status, and as a quality of life indicator. The fourth phase of the model, which concerns the educational and organizational diagnosis, describes three clusters of behavioral determinants: predisposing, enabling and reinforcing factors. Predisposing factors provide the rationale or motivation for behavior, such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values, and perceived needs and abilities [(Green and Kreuter, 1991), p. 154]. Self-knowledge, general self-appraisal and self-efficacy are considered as predisposing factors.

To summarize, self-esteem can function both as a determinant and as an outcome of healthy behavior within health behavior models. Poor self-esteem can trigger poor coping behavior or risk behavior that subsequently increases the likelihood of certain diseases among which are mental disorders. On the other hand, the presence of poor coping behavior and ill-health can generate or reinforce a negative self-image.

Self-esteem in a BSA to mental health promotion and prevention in schools

Given the evidence supporting the role of self-esteem as a core element in physical and mental health, it is recommended that its potential in future health promotion and prevention programs be reconsidered.

The design of future policies for mental health promotion and the prevention of mental disorders is currently an area of active debate ( Hosman, 2000 ). A key question in the discussion is which is more effective: a preventive approach focusing on specific disorders or a more generic preventive approach?

Based on the evidence supporting the role of self-esteem as a non-specific risk factor and protective factor in the development of mental disorders and social problems, we advocate a generic preventive approach built around the ‘self’. In general, changing common risk and protective factors (e.g. self-esteem, coping skills, social support) and adopting a generic preventive approach can reduce the risk of the development of a range of mental disorders and promote individual well-being even before the onset of a specific problem has presented itself. Given its multi-outcome perspective, we have termed this strategy the ‘BSA’ in prevention and promotion.

Self-esteem is considered one of the important elements of the BSA. By fostering self-esteem, and hence treating a common risk factor, it is possible to contribute to the prevention of an array of physical diseases, mental disorders and social problems challenging society today. This may also, at a later date, imply the prevention of a shift to other problem behaviors or symptoms which might occur when only problem-specific risk factors are addressed. For example, an eating disorder could be replaced by another type of symptom, such as alcohol abuse, smoking, social anxiety or depression, when only the eating behavior itself is addressed and not more basic causes, such as poor self-esteem, high stress levels and lack of social support. Although there is, as yet, no published research on such a shift phenomenon, the high level of co-morbidity between such problems might reflect the likelihood of its existence. Numerous studies support the idea of co-morbidity and showed that many mental disorders have overlapping associated risk factors such as self-esteem. There is a significant degree of co-morbidity between and within internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors such as depression, anxiety, substance disorders and delinquency ( Harrington et al. , 1996 ; Angold et al. , 1999 ; Swendsen and Merikangas, 2000 ). By considering the individual as a whole, within the BSA, the risk of such an eventuality could be reduced.

The BSA could have practical implications. Schools are an ideal setting for implementing BSA programs, thereby aiming at preventing an array of problems, since they cover the entire population. They have the means and responsibility for the promotion of healthy behavior for such a common risk and protective factor, since school children are in their formative stage. A mental health promotion curriculum oriented towards emotional and social learning could include a focus on enhancing self-esteem. Weare ( Weare, 2000 ) stressed that schools need to aim at helping children develop a healthy sense of self-esteem as part of the development of their ‘intra-personal intelligence’. According to Gardner (Gardner, 1993) ‘intra-personal intelligence’ is the ability to form an accurate model of oneself and the ability to use it to operate effectively in life. Self-esteem, then, is an important component of this ability. Serious thought should be given to the practical implementation of these ideas.

It is important to clearly define the nature of a BSA program designed to foster self-esteem within the school setting. In our opinion, such a program should include important determinants of self-esteem, i.e. competence and social support.

Harter ( Harter, 1999 ) stated that competence and social support, together provide a powerful explanation of the level of self-esteem. According to Harter's research on self-perceived competence, every child experiences some discrepancy between what he/she would like to be, the ‘ideal self’, and his/her actual perception of him/herself, ‘the real self’. When this discrepancy is large and it deals with a personally relevant domain, this will result in lower self-esteem. Moreover, the overall sense of support of significant others (especially parents, peers and teachers) is also influential for the development of self-esteem. Children who feel that others accept them, and are unconditionally loved and respected, will report a higher sense of self-esteem ( Bee, 2000 ). Thus, children with a high discrepancy and a low sense of social support reported the lowest sense of self-esteem. These results suggest that efforts to improve self-esteem in children require both supportive social surroundings and the formation and acceptance of realistic personal goals in the personally relevant domains ( Harter, 1999 ).

In addition to determinants such as competence and social support, we need to translate the theoretical knowledge on coping with inner self-processes (e.g. inconsistencies between the real and ideal self) into practice, in order to perform a systematic intervention regarding the self. Harter's work offers an important foundation for this. Based on her own and others' research on the development of the self, she suggests the following principles to prevent the development of negative self-esteem and to enhance self-worth ( Harter, 1999 ):

Reduction of the discrepancy between the real self and the ideal self.

Encouragement of relatively realistic self-perceptions.

Encouraging the belief that positive self-evaluations can be achieved.

Appreciation for the individual's views about their self-esteem and individual perceptions on causes and consequences of self-worth.

Increasing awareness of the origins of negative self-perceptions.

Providing a more integrated personal construct while improving understanding of self-contradictions.

Encouraging the individual and his/her significant others to promote the social support they give and receive.

Fostering internalization of positive opinions of others.

Haney and Durlak ( Haney and Durlak, 1998 ) wrote a meta-analytical review of 116 intervention studies for children and adolescents. Most studies indicated significant improvement in children's and adolescents' self-esteem and self-concept, and as a result of this change, significant changes in behavioral, personality, and academic functioning. Haney and Durlak reported on the possible impact improved self-esteem had on the onset of social problems. However, their study did not offer an insight into the potential effect of enhanced self-esteem on mental disorders.

Several mental health-promoting school programs that have addressed self-esteem and the determinants of self-esteem in practice, were effective in the prevention of eating disorders ( O'Dea and Abraham, 2000 ), problem behavior ( Flay and Ordway, 2001 ), and the reduction of substance abuse, antisocial behavior and anxiety ( Short, 1998 ). We shall focus on the first two programs because these are universal programs, which focused on ‘mainstream’ school children. The prevention of eating disorders program ‘Everybody's Different’ ( O'Dea and Abraham, 2000 ) is aimed at female adolescents aged 11–14 years old. It was developed in response to the poor efficacy of conventional body-image education in improving body image and eating behavior. ‘Everybody's Different’ has adopted an alternative methodology built on an interactive, school-based, self-esteem approach and is designed to prevent the development of eating disorders by improving self-esteem. The program has significantly changed aspects of self-esteem, body satisfaction, social acceptance and physical appearance. Female students targeted by the intervention rated their physical appearance, as perceived by others, significantly higher than control-group students, and allowed their body weight to increase appropriately by refraining from weight-loss behavior seen in the control group. These findings were still evident after 12 months. This is one of the first controlled educational interventions that had successfully improved body image and produced long-term changes in the attitudes and self-image of young adolescents.

The ‘Positive Action Program’ ( Flay and Ordway, 2001 ) serves as a unique example of some BSA principles in practice. The program addresses the challenge of increasing self-esteem, reducing problem behavior and improving school performance. The types of problem behavior in question were delinquent behavior, ‘misdemeanors’ and objection to school rules ( Flay and Ordway, 2001 ). This program concentrates on self-concept and self-esteem, but also includes other risk and protective factors, such as positive actions, self-control, social skills and social support that could be considered as determinants of self-esteem. Other important determinants of self-esteem, such as coping with internal self-processes, are not addressed. At present, the literature does not provide many examples of BSA studies that produce general preventive effects among adolescents who do not (yet) display behavioral problems ( Greenberg et al. , 2000 ).

To conclude, research results show beneficial outcomes of positive self-esteem, which is seen to be associated with mental well-being, happiness, adjustment, success, academic achievements and satisfaction. It is also associated with better recovery after severe diseases. However, the evolving nature of self-esteem could also result in negative outcomes. For example, low self-esteem can be a causal factor in depression, anxiety, eating disorders, poor social functioning, school dropout and risk behavior. Interestingly, the cross-sectional characteristic of many studies does not exclude the possibility that low self-esteem can also be considered as an important consequence of such disorders and behavioral problems.

Self-esteem is an important risk and protective factor linked to a diversity of health and social outcomes. Therefore, self-esteem enhancement can serve as a key component in a BSA approach in prevention and health promotion. The design and implementation of mental health programs with self-esteem as one of the core variables is an important and promising development in health promotion.

The authors are grateful to Dr Alastair McElroy for his constructive comments on this paper. The authors wish to thank Rianne Kasander (MA) and Chantal Van Ree (MA) for their assistance in the literature search. Financing for this study was generously provided by the Dutch Health Research and Development Council (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland, ZON/MW).

Abel, E. ( 1998 ) Sexual risk behaviors among ship and shore based Navy women. Military Medicine , 163 , 250 –256.

Abramson, L.Y., Metalsky, G.I. and Alloy, L.B. ( 1989 ) Hopelessness depression: a theory based subtype of depression. Psychological Review , 96 , 358 –372.

Adams, M.J. ( 1996 ) Youth in crisis: an examination of adverse risk factors effecting children's cognitive and behavioral–emotional development, children ages 10–16. Dissertation Abstracts International A: Humanities and Social Sciences , 56 (8-A), 3313 .

Ajzen, I. ( 1991 ) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational and Human Decision Processes , 50 , 179 –211.

Albee, G.W. ( 1985 ) The argument for primary prevention. Journal of primary prevention , 5 , 213 –219.

Alice, E. ( 1993 ) Mediating at risk factors among seventh and eighth grade students with specific learning disabilities using a holistically based model. Dissertation , Nove University.

Andrews, E.J. ( 1999 ) The effects of a self-improvement program on the self-esteem of single college mothers. Dissertation Abstracts International A: Humanities and Social Sciences , 60 (2-A), 0345 .