- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Methodology

Definition:

Research Methodology refers to the systematic and scientific approach used to conduct research, investigate problems, and gather data and information for a specific purpose. It involves the techniques and procedures used to identify, collect , analyze , and interpret data to answer research questions or solve research problems . Moreover, They are philosophical and theoretical frameworks that guide the research process.

Structure of Research Methodology

Research methodology formats can vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project, but the following is a basic example of a structure for a research methodology section:

I. Introduction

- Provide an overview of the research problem and the need for a research methodology section

- Outline the main research questions and objectives

II. Research Design

- Explain the research design chosen and why it is appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Discuss any alternative research designs considered and why they were not chosen

- Describe the research setting and participants (if applicable)

III. Data Collection Methods

- Describe the methods used to collect data (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations)

- Explain how the data collection methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or instruments used for data collection

IV. Data Analysis Methods

- Describe the methods used to analyze the data (e.g., statistical analysis, content analysis )

- Explain how the data analysis methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or software used for data analysis

V. Ethical Considerations

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise from the research and how they were addressed

- Explain how informed consent was obtained (if applicable)

- Detail any measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity

VI. Limitations

- Identify any potential limitations of the research methodology and how they may impact the results and conclusions

VII. Conclusion

- Summarize the key aspects of the research methodology section

- Explain how the research methodology addresses the research question(s) and objectives

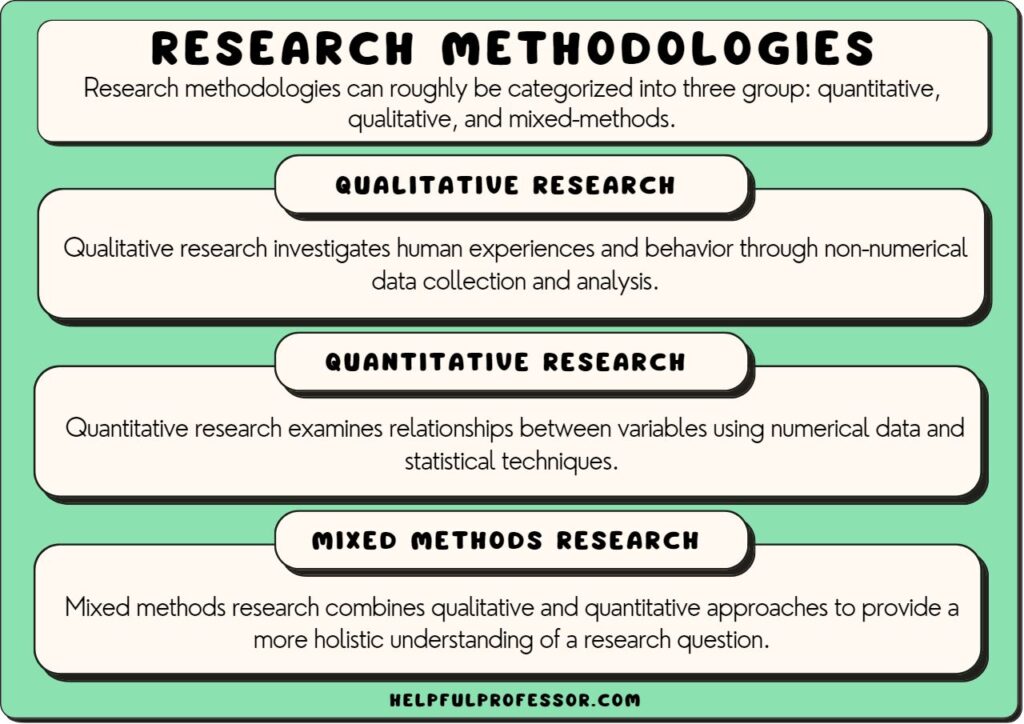

Research Methodology Types

Types of Research Methodology are as follows:

Quantitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. This type of research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Qualitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data such as words, images, and observations. This type of research is often used to explore complex phenomena, to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular topic, and to generate hypotheses.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research. This approach can be particularly useful for studies that aim to explore complex phenomena and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic.

Case Study Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves in-depth examination of a single case or a small number of cases. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and anthropology to gain a detailed understanding of a particular individual or group.

Action Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves a collaborative process between researchers and practitioners to identify and solve real-world problems. Action research is often used in education, healthcare, and social work.

Experimental Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the manipulation of one or more independent variables to observe their effects on a dependent variable. Experimental research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Survey Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection of data from a sample of individuals using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is often used to study attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

Grounded Theory Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the development of theories based on the data collected during the research process. Grounded theory is often used in sociology and anthropology to generate theories about social phenomena.

Research Methodology Example

An Example of Research Methodology could be the following:

Research Methodology for Investigating the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Reducing Symptoms of Depression in Adults

Introduction:

The aim of this research is to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. To achieve this objective, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) will be conducted using a mixed-methods approach.

Research Design:

The study will follow a pre-test and post-test design with two groups: an experimental group receiving CBT and a control group receiving no intervention. The study will also include a qualitative component, in which semi-structured interviews will be conducted with a subset of participants to explore their experiences of receiving CBT.

Participants:

Participants will be recruited from community mental health clinics in the local area. The sample will consist of 100 adults aged 18-65 years old who meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group.

Intervention :

The experimental group will receive 12 weekly sessions of CBT, each lasting 60 minutes. The intervention will be delivered by licensed mental health professionals who have been trained in CBT. The control group will receive no intervention during the study period.

Data Collection:

Quantitative data will be collected through the use of standardized measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Data will be collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and at a 3-month follow-up. Qualitative data will be collected through semi-structured interviews with a subset of participants from the experimental group. The interviews will be conducted at the end of the intervention period, and will explore participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Data Analysis:

Quantitative data will be analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-tests, and mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns in participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Ethical Considerations:

This study will comply with ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. Participants will provide informed consent before participating in the study, and their privacy and confidentiality will be protected throughout the study. Any adverse events or reactions will be reported and managed appropriately.

Data Management:

All data collected will be kept confidential and stored securely using password-protected databases. Identifying information will be removed from qualitative data transcripts to ensure participants’ anonymity.

Limitations:

One potential limitation of this study is that it only focuses on one type of psychotherapy, CBT, and may not generalize to other types of therapy or interventions. Another limitation is that the study will only include participants from community mental health clinics, which may not be representative of the general population.

Conclusion:

This research aims to investigate the effectiveness of CBT in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. By using a randomized controlled trial and a mixed-methods approach, the study will provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between CBT and depression. The results of this study will have important implications for the development of effective treatments for depression in clinical settings.

How to Write Research Methodology

Writing a research methodology involves explaining the methods and techniques you used to conduct research, collect data, and analyze results. It’s an essential section of any research paper or thesis, as it helps readers understand the validity and reliability of your findings. Here are the steps to write a research methodology:

- Start by explaining your research question: Begin the methodology section by restating your research question and explaining why it’s important. This helps readers understand the purpose of your research and the rationale behind your methods.

- Describe your research design: Explain the overall approach you used to conduct research. This could be a qualitative or quantitative research design, experimental or non-experimental, case study or survey, etc. Discuss the advantages and limitations of the chosen design.

- Discuss your sample: Describe the participants or subjects you included in your study. Include details such as their demographics, sampling method, sample size, and any exclusion criteria used.

- Describe your data collection methods : Explain how you collected data from your participants. This could include surveys, interviews, observations, questionnaires, or experiments. Include details on how you obtained informed consent, how you administered the tools, and how you minimized the risk of bias.

- Explain your data analysis techniques: Describe the methods you used to analyze the data you collected. This could include statistical analysis, content analysis, thematic analysis, or discourse analysis. Explain how you dealt with missing data, outliers, and any other issues that arose during the analysis.

- Discuss the validity and reliability of your research : Explain how you ensured the validity and reliability of your study. This could include measures such as triangulation, member checking, peer review, or inter-coder reliability.

- Acknowledge any limitations of your research: Discuss any limitations of your study, including any potential threats to validity or generalizability. This helps readers understand the scope of your findings and how they might apply to other contexts.

- Provide a summary: End the methodology section by summarizing the methods and techniques you used to conduct your research. This provides a clear overview of your research methodology and helps readers understand the process you followed to arrive at your findings.

When to Write Research Methodology

Research methodology is typically written after the research proposal has been approved and before the actual research is conducted. It should be written prior to data collection and analysis, as it provides a clear roadmap for the research project.

The research methodology is an important section of any research paper or thesis, as it describes the methods and procedures that will be used to conduct the research. It should include details about the research design, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and any ethical considerations.

The methodology should be written in a clear and concise manner, and it should be based on established research practices and standards. It is important to provide enough detail so that the reader can understand how the research was conducted and evaluate the validity of the results.

Applications of Research Methodology

Here are some of the applications of research methodology:

- To identify the research problem: Research methodology is used to identify the research problem, which is the first step in conducting any research.

- To design the research: Research methodology helps in designing the research by selecting the appropriate research method, research design, and sampling technique.

- To collect data: Research methodology provides a systematic approach to collect data from primary and secondary sources.

- To analyze data: Research methodology helps in analyzing the collected data using various statistical and non-statistical techniques.

- To test hypotheses: Research methodology provides a framework for testing hypotheses and drawing conclusions based on the analysis of data.

- To generalize findings: Research methodology helps in generalizing the findings of the research to the target population.

- To develop theories : Research methodology is used to develop new theories and modify existing theories based on the findings of the research.

- To evaluate programs and policies : Research methodology is used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and policies by collecting data and analyzing it.

- To improve decision-making: Research methodology helps in making informed decisions by providing reliable and valid data.

Purpose of Research Methodology

Research methodology serves several important purposes, including:

- To guide the research process: Research methodology provides a systematic framework for conducting research. It helps researchers to plan their research, define their research questions, and select appropriate methods and techniques for collecting and analyzing data.

- To ensure research quality: Research methodology helps researchers to ensure that their research is rigorous, reliable, and valid. It provides guidelines for minimizing bias and error in data collection and analysis, and for ensuring that research findings are accurate and trustworthy.

- To replicate research: Research methodology provides a clear and detailed account of the research process, making it possible for other researchers to replicate the study and verify its findings.

- To advance knowledge: Research methodology enables researchers to generate new knowledge and to contribute to the body of knowledge in their field. It provides a means for testing hypotheses, exploring new ideas, and discovering new insights.

- To inform decision-making: Research methodology provides evidence-based information that can inform policy and decision-making in a variety of fields, including medicine, public health, education, and business.

Advantages of Research Methodology

Research methodology has several advantages that make it a valuable tool for conducting research in various fields. Here are some of the key advantages of research methodology:

- Systematic and structured approach : Research methodology provides a systematic and structured approach to conducting research, which ensures that the research is conducted in a rigorous and comprehensive manner.

- Objectivity : Research methodology aims to ensure objectivity in the research process, which means that the research findings are based on evidence and not influenced by personal bias or subjective opinions.

- Replicability : Research methodology ensures that research can be replicated by other researchers, which is essential for validating research findings and ensuring their accuracy.

- Reliability : Research methodology aims to ensure that the research findings are reliable, which means that they are consistent and can be depended upon.

- Validity : Research methodology ensures that the research findings are valid, which means that they accurately reflect the research question or hypothesis being tested.

- Efficiency : Research methodology provides a structured and efficient way of conducting research, which helps to save time and resources.

- Flexibility : Research methodology allows researchers to choose the most appropriate research methods and techniques based on the research question, data availability, and other relevant factors.

- Scope for innovation: Research methodology provides scope for innovation and creativity in designing research studies and developing new research techniques.

Research Methodology Vs Research Methods

About the author.

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

15 Research Methodology Examples

Research methodologies can roughly be categorized into three group: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods.

- Qualitative Research : This methodology is based on obtaining deep, contextualized, non-numerical data. It can occur, for example, through open-ended questioning of research particiapnts in order to understand human behavior. It’s all about describing and analyzing subjective phenomena such as emotions or experiences.

- Quantitative Research: This methodology is rationally-based and relies heavily on numerical analysis of empirical data . With quantitative research, you aim for objectivity by creating hypotheses and testing them through experiments or surveys, which allow for statistical analyses.

- Mixed-Methods Research: Mixed-methods research combines both previous types into one project. We have more flexibility when designing our research study with mixed methods since we can use multiple approaches depending on our needs at each time. Using mixed methods can help us validate our results and offer greater predictability than just either type of methodology alone could provide.

Below are research methodologies that fit into each category.

Qualitative Research Methodologies

1. case study.

Conducts an in-depth examination of a specific case, individual, or event to understand a phenomenon.

Instead of examining a whole population for numerical trend data, case study researchers seek in-depth explanations of one event.

The benefit of case study research is its ability to elucidate overlooked details of interesting cases of a phenomenon (Busetto, Wick & Gumbinger, 2020). It offers deep insights for empathetic, reflective, and thoughtful understandings of that phenomenon.

However, case study findings aren’t transferrable to new contexts or for population-wide predictions. Instead, they inform practitioner understandings for nuanced, deep approaches to future instances (Liamputtong, 2020).

2. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory involves generating hypotheses and theories through the collection and interpretation of data (Faggiolani, n.d.). Its distinguishing features is that it doesn’t test a hypothesis generated prior to analysis, but rather generates a hypothesis or ‘theory’ that emerges from the data.

It also involves the application of inductive reasoning and is often contrasted with the hypothetico-deductive model of scientific research. This research methodology was developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s (Glaser & Strauss, 2009).

The basic difference between traditional scientific approaches to research and grounded theory is that the latter begins with a question, then collects data, and the theoretical framework is said to emerge later from this data.

By contrast, scientists usually begin with an existing theoretical framework , develop hypotheses, and only then start collecting data to verify or falsify the hypotheses.

3. Ethnography

In ethnographic research , the researcher immerses themselves within the group they are studying, often for long periods of time.

This type of research aims to understand the shared beliefs, practices, and values of a particular community by immersing the researcher within the cultural group.

Although ethnographic research cannot predict or identify trends in an entire population, it can create detailed explanations of cultural practices and comparisons between social and cultural groups.

When a person conducts an ethnographic study of themselves or their own culture, it can be considered autoethnography .

Its strength lies in producing comprehensive accounts of groups of people and their interactions.

Common methods researchers use during an ethnographic study include participant observation , thick description, unstructured interviews, and field notes vignettes. These methods can provide detailed and contextualized descriptions of their subjects.

Example Study

Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street by Karen Ho involves an anthropologist who embeds herself with Wall Street firms to study the culture of Wall Street bankers and how this culture affects the broader economy and world.

4. Phenomenology

Phenomenology to understand and describe individuals’ lived experiences concerning a specific phenomenon.

As a research methodology typically used in the social sciences , phenomenology involves the study of social reality as a product of intersubjectivity (the intersection of people’s cognitive perspectives) (Zahavi & Overgaard, n.d.).

This philosophical approach was first developed by Edmund Husserl.

5. Narrative Research

Narrative research explores personal stories and experiences to understand their meanings and interpretations.

It is also known as narrative inquiry and narrative analysis(Riessman, 1993).

This approach to research uses qualitative material like journals, field notes, letters, interviews, texts, photos, etc., as its data.

It is aimed at understanding the way people create meaning through narratives (Clandinin & Connelly, 2004).

6. Discourse Analysis

A discourse analysis examines the structure, patterns, and functions of language in context to understand how the text produces social constructs.

This methodology is common in critical theory , poststructuralism , and postmodernism. Its aim is to understand how language constructs discourses (roughly interpreted as “ways of thinking and constructing knowledge”).

As a qualitative methodology , its focus is on developing themes through close textual analysis rather than using numerical methods. Common methods for extracting data include semiotics and linguistic analysis.

7. Action Research

Action research involves researchers working collaboratively with stakeholders to address problems, develop interventions, and evaluate effectiveness.

Action research is a methodology and philosophy of research that is common in the social sciences.

The term was first coined in 1944 by Kurt Lewin, a German-American psychologist who also introduced applied research and group communication (Altrichter & Gstettner, 1993).

Lewin originally defined action research as involving two primary processes: taking action and doing research (Lewin, 1946).

Action research involves planning, action, and information-seeking about the result of the action.

Since Lewin’s original formulation, many different theoretical approaches to action research have been developed. These include action science, participatory action research, cooperative inquiry, and living educational theory among others.

Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing (Ellison & Drew, 2019) is a study conducted by a school teacher who used video games to help teach his students English. It involved action research, where he interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience, and iterated on his teaching style based on their feedback (disclaimer: I am the second author of this study).

See More: Examples of Qualitative Research

Quantitative Research Methodologies

8. experimental design.

As the name suggests, this type of research is based on testing hypotheses in experimental settings by manipulating variables and observing their effects on other variables.

The main benefit lies in its ability to manipulate specific variables to determine their effect on outcomes which is a great method for those looking for causational links in their research.

This is common, for example, in high-school science labs, where students are asked to introduce a variable into a setting in order to examine its effect.

9. Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental design observes and measures associations between variables without manipulating them.

It can take, for example, the form of a ‘fly on the wall’ observation of a phenomenon, allowing researchers to examine authentic settings and changes that occur naturally in the environment.

10. Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional design involves analyzing variables pertaining to a specific time period and at that exact moment.

This approach allows for an extensive examination and comparison of distinct and independent subjects, thereby offering advantages over qualitative methodologies such as case studies or surveys.

While cross-sectional design can be extremely useful in taking a ‘snapshot in time’, as a standalone method, it is not useful for examining changes in subjects after an intervention. The next methodology addresses this issue.

The prime example of this type of study is a census. A population census is mailed out to every house in the country, and each household must complete the census on the same evening. This allows the government to gather a snapshot of the nation’s demographics, beliefs, religion, and so on.

11. Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal research gathers data from the same subjects over an extended period to analyze changes and development.

In contrast to cross-sectional tactics, longitudinal designs examine variables more than once, over a pre-determined time span, allowing for multiple data points to be taken at different times.

A cross-sectional design is also useful for examining cohort effects , by comparing differences or changes in multiple different generations’ beliefs over time.

With multiple data points collected over extended periods ,it’s possible to examine continuous changes within things like population dynamics or consumer behavior. This makes detailed analysis of change possible.

12. Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental design involves manipulating variables for analysis, but uses pre-existing groups of subjects rather than random groups.

Because the groups of research participants already exist, they cannot be randomly assigned to a cohort as with a true experimental design study. This makes inferring a causal relationship more difficult, but is nonetheless often more feasible in real-life settings.

Quasi-experimental designs are generally considered inferior to true experimental designs.

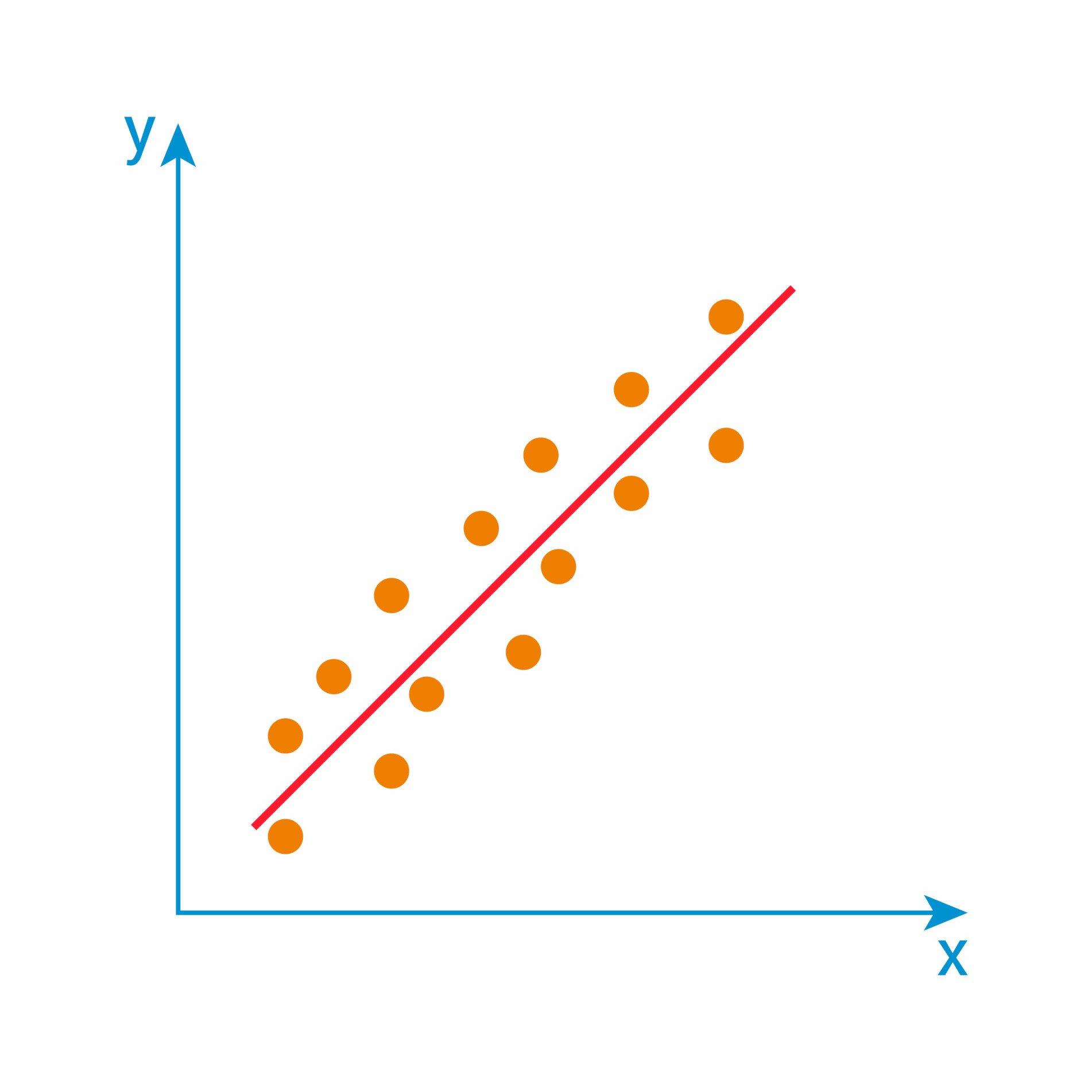

13. Correlational Research

Correlational research examines the relationships between two or more variables, determining the strength and direction of their association.

Similar to quasi-experimental methods, this type of research focuses on relationship differences between variables.

This approach provides a fast and easy way to make initial hypotheses based on either positive or negative correlation trends that can be observed within dataset.

Methods used for data analysis may include statistic correlations such as Pearson’s or Spearman’s.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodologies

14. sequential explanatory design (quan→qual).

This methodology involves conducting quantitative analysis first, then supplementing it with a qualitative study.

It begins by collecting quantitative data that is then analyzed to determine any significant patterns or trends.

Secondly, qualitative methods are employed. Their intent is to help interpret and expand the quantitative results.

This offers greater depth into understanding both large and smaller aspects of research questions being addressed.

The rationale behind this approach is to ensure that your data collection generates richer context for gaining insight into the particular issue across different levels, integrating in one study, qualitative exploration as well as statistical procedures.

15. Sequential Exploratory Design (QUAL→QUAN)

This methodology goes in the other direction, starting with qualitative analysis and ending with quantitative analysis.

It starts with qualitative research that delves deeps into complex areas and gathers rich information through interviewing or observing participants.

After this stage of exploration comes to an end, quantitative techniques are used to analyze the collected data through inferential statistics.

The idea is that a qualitative study can arm the researchers with a strong hypothesis testing framework, which they can then apply to a larger sample size using qualitative methods.

When I first took research classes, I had a lot of trouble distinguishing between methodologies and methods.

The key is to remember that the methodology sets the direction, while the methods are the specific tools to be used. A good analogy is transport: first you need to choose a mode (public transport, private transport, motorized transit, non-motorized transit), then you can choose a tool (bus, car, bike, on foot).

While research methodologies can be split into three types, each type has many different nuanced methodologies that can be chosen, before you then choose the methods – or tools – to use in the study. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, so choose wisely!

Altrichter, H., & Gstettner, P. (1993). Action Research: A closed chapter in the history of German social science? Educational Action Research , 1 (3), 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010302

Audi, R. (1999). The Cambridge dictionary of philosophy . Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/cambridgediction00audi

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2004). Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research . John Wiley & Sons.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research . Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Faggiolani, C. (n.d.). Perceived Identity: Applying Grounded Theory in Libraries . https://doi.org/10.4403/jlis.it-4592

Gauch, H. G. (2002). Scientific Method in Practice . Cambridge University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Transaction Publishers.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques . New Age International.

Kuada, J. (2012). Research Methodology: A Project Guide for University Students . Samfundslitteratur.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues , 2, 4 , 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The Development of Constructivist Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 5 (1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500103

Mingers, J., & Willcocks, L. (2017). An integrative semiotic methodology for IS research. Information and Organization , 27 (1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2016.12.001

OECD. (2015). Frascati Manual 2015: Guidelines for Collecting and Reporting Data on Research and Experimental Development . Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/frascati-manual-2015_9789264239012-en

Peirce, C. S. (1992). The Essential Peirce, Volume 1: Selected Philosophical Writings (1867–1893) . Indiana University Press.

Reese, W. L. (1980). Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought . Humanities Press.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis . Sage Publications, Inc.

Saussure, F. de, & Riedlinger, A. (1959). Course in General Linguistics . Philosophical Library.

Thomas, C. G. (2021). Research Methodology and Scientific Writing . Springer Nature.

Zahavi, D., & Overgaard, S. (n.d.). Phenomenological Sociology—The Subjectivity of Everyday Life .

Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch)

Tio Gabunia is an academic writer and architect based in Tbilisi. He has studied architecture, design, and urban planning at the Georgian Technical University and the University of Lisbon. He has worked in these fields in Georgia, Portugal, and France. Most of Tio’s writings concern philosophy. Other writings include architecture, sociology, urban planning, and economics.

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 6 Types of Societies (With 21 Examples)

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Public Health Policy Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Cultural Differences Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link Social Interaction Types & Examples (Sociology)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE : Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE : If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE : If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

Published on 25 February 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Your research methodology discusses and explains the data collection and analysis methods you used in your research. A key part of your thesis, dissertation, or research paper, the methodology chapter explains what you did and how you did it, allowing readers to evaluate the reliability and validity of your research.

It should include:

- The type of research you conducted

- How you collected and analysed your data

- Any tools or materials you used in the research

- Why you chose these methods

- Your methodology section should generally be written in the past tense .

- Academic style guides in your field may provide detailed guidelines on what to include for different types of studies.

- Your citation style might provide guidelines for your methodology section (e.g., an APA Style methods section ).

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

How to write a research methodology, why is a methods section important, step 1: explain your methodological approach, step 2: describe your data collection methods, step 3: describe your analysis method, step 4: evaluate and justify the methodological choices you made, tips for writing a strong methodology chapter, frequently asked questions about methodology.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Your methods section is your opportunity to share how you conducted your research and why you chose the methods you chose. It’s also the place to show that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated .

It gives your research legitimacy and situates it within your field, and also gives your readers a place to refer to if they have any questions or critiques in other sections.

You can start by introducing your overall approach to your research. You have two options here.

Option 1: Start with your “what”

What research problem or question did you investigate?

- Aim to describe the characteristics of something?

- Explore an under-researched topic?

- Establish a causal relationship?

And what type of data did you need to achieve this aim?

- Quantitative data , qualitative data , or a mix of both?

- Primary data collected yourself, or secondary data collected by someone else?

- Experimental data gathered by controlling and manipulating variables, or descriptive data gathered via observations?

Option 2: Start with your “why”

Depending on your discipline, you can also start with a discussion of the rationale and assumptions underpinning your methodology. In other words, why did you choose these methods for your study?

- Why is this the best way to answer your research question?

- Is this a standard methodology in your field, or does it require justification?

- Were there any ethical considerations involved in your choices?

- What are the criteria for validity and reliability in this type of research ?

Once you have introduced your reader to your methodological approach, you should share full details about your data collection methods .

Quantitative methods

In order to be considered generalisable, you should describe quantitative research methods in enough detail for another researcher to replicate your study.

Here, explain how you operationalised your concepts and measured your variables. Discuss your sampling method or inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as any tools, procedures, and materials you used to gather your data.

Surveys Describe where, when, and how the survey was conducted.

- How did you design the questionnaire?

- What form did your questions take (e.g., multiple choice, Likert scale )?

- Were your surveys conducted in-person or virtually?

- What sampling method did you use to select participants?

- What was your sample size and response rate?

Experiments Share full details of the tools, techniques, and procedures you used to conduct your experiment.

- How did you design the experiment ?

- How did you recruit participants?

- How did you manipulate and measure the variables ?

- What tools did you use?

Existing data Explain how you gathered and selected the material (such as datasets or archival data) that you used in your analysis.

- Where did you source the material?

- How was the data originally produced?

- What criteria did you use to select material (e.g., date range)?

The survey consisted of 5 multiple-choice questions and 10 questions measured on a 7-point Likert scale.

The goal was to collect survey responses from 350 customers visiting the fitness apparel company’s brick-and-mortar location in Boston on 4–8 July 2022, between 11:00 and 15:00.

Here, a customer was defined as a person who had purchased a product from the company on the day they took the survey. Participants were given 5 minutes to fill in the survey anonymously. In total, 408 customers responded, but not all surveys were fully completed. Due to this, 371 survey results were included in the analysis.

Qualitative methods

In qualitative research , methods are often more flexible and subjective. For this reason, it’s crucial to robustly explain the methodology choices you made.

Be sure to discuss the criteria you used to select your data, the context in which your research was conducted, and the role you played in collecting your data (e.g., were you an active participant, or a passive observer?)

Interviews or focus groups Describe where, when, and how the interviews were conducted.

- How did you find and select participants?

- How many participants took part?

- What form did the interviews take ( structured , semi-structured , or unstructured )?

- How long were the interviews?

- How were they recorded?

Participant observation Describe where, when, and how you conducted the observation or ethnography .

- What group or community did you observe? How long did you spend there?

- How did you gain access to this group? What role did you play in the community?

- How long did you spend conducting the research? Where was it located?

- How did you record your data (e.g., audiovisual recordings, note-taking)?

Existing data Explain how you selected case study materials for your analysis.

- What type of materials did you analyse?

- How did you select them?

In order to gain better insight into possibilities for future improvement of the fitness shop’s product range, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 8 returning customers.

Here, a returning customer was defined as someone who usually bought products at least twice a week from the store.

Surveys were used to select participants. Interviews were conducted in a small office next to the cash register and lasted approximately 20 minutes each. Answers were recorded by note-taking, and seven interviews were also filmed with consent. One interviewee preferred not to be filmed.

Mixed methods

Mixed methods research combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. If a standalone quantitative or qualitative study is insufficient to answer your research question, mixed methods may be a good fit for you.

Mixed methods are less common than standalone analyses, largely because they require a great deal of effort to pull off successfully. If you choose to pursue mixed methods, it’s especially important to robustly justify your methods here.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Next, you should indicate how you processed and analysed your data. Avoid going into too much detail: you should not start introducing or discussing any of your results at this stage.

In quantitative research , your analysis will be based on numbers. In your methods section, you can include:

- How you prepared the data before analysing it (e.g., checking for missing data , removing outliers , transforming variables)

- Which software you used (e.g., SPSS, Stata or R)

- Which statistical tests you used (e.g., two-tailed t test , simple linear regression )

In qualitative research, your analysis will be based on language, images, and observations (often involving some form of textual analysis ).

Specific methods might include:

- Content analysis : Categorising and discussing the meaning of words, phrases and sentences

- Thematic analysis : Coding and closely examining the data to identify broad themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying communication and meaning in relation to their social context

Mixed methods combine the above two research methods, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches into one coherent analytical process.

Above all, your methodology section should clearly make the case for why you chose the methods you did. This is especially true if you did not take the most standard approach to your topic. In this case, discuss why other methods were not suitable for your objectives, and show how this approach contributes new knowledge or understanding.

In any case, it should be overwhelmingly clear to your reader that you set yourself up for success in terms of your methodology’s design. Show how your methods should lead to results that are valid and reliable, while leaving the analysis of the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results for your discussion section .

- Quantitative: Lab-based experiments cannot always accurately simulate real-life situations and behaviours, but they are effective for testing causal relationships between variables .

- Qualitative: Unstructured interviews usually produce results that cannot be generalised beyond the sample group , but they provide a more in-depth understanding of participants’ perceptions, motivations, and emotions.

- Mixed methods: Despite issues systematically comparing differing types of data, a solely quantitative study would not sufficiently incorporate the lived experience of each participant, while a solely qualitative study would be insufficiently generalisable.

Remember that your aim is not just to describe your methods, but to show how and why you applied them. Again, it’s critical to demonstrate that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated.

1. Focus on your objectives and research questions

The methodology section should clearly show why your methods suit your objectives and convince the reader that you chose the best possible approach to answering your problem statement and research questions .

2. Cite relevant sources

Your methodology can be strengthened by referencing existing research in your field. This can help you to:

- Show that you followed established practice for your type of research

- Discuss how you decided on your approach by evaluating existing research

- Present a novel methodological approach to address a gap in the literature

3. Write for your audience

Consider how much information you need to give, and avoid getting too lengthy. If you are using methods that are standard for your discipline, you probably don’t need to give a lot of background or justification.

Regardless, your methodology should be a clear, well-structured text that makes an argument for your approach, not just a list of technical details and procedures.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research. Developing your methodology involves studying the research methods used in your field and the theories or principles that underpin them, in order to choose the approach that best matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. interviews, experiments , surveys , statistical tests ).

In a dissertation or scientific paper, the methodology chapter or methods section comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/methodology/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide.

Sampling Methods In Reseach: Types, Techniques, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

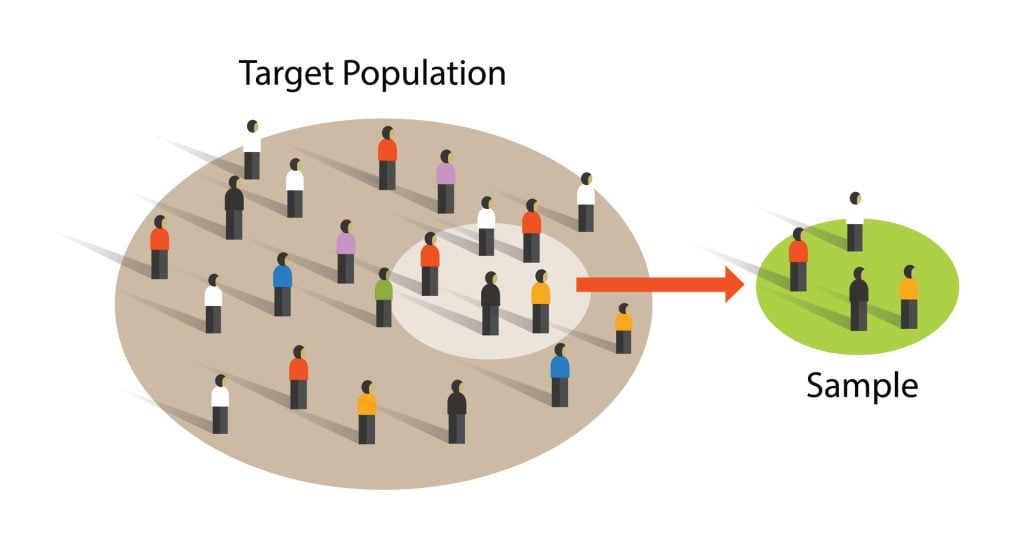

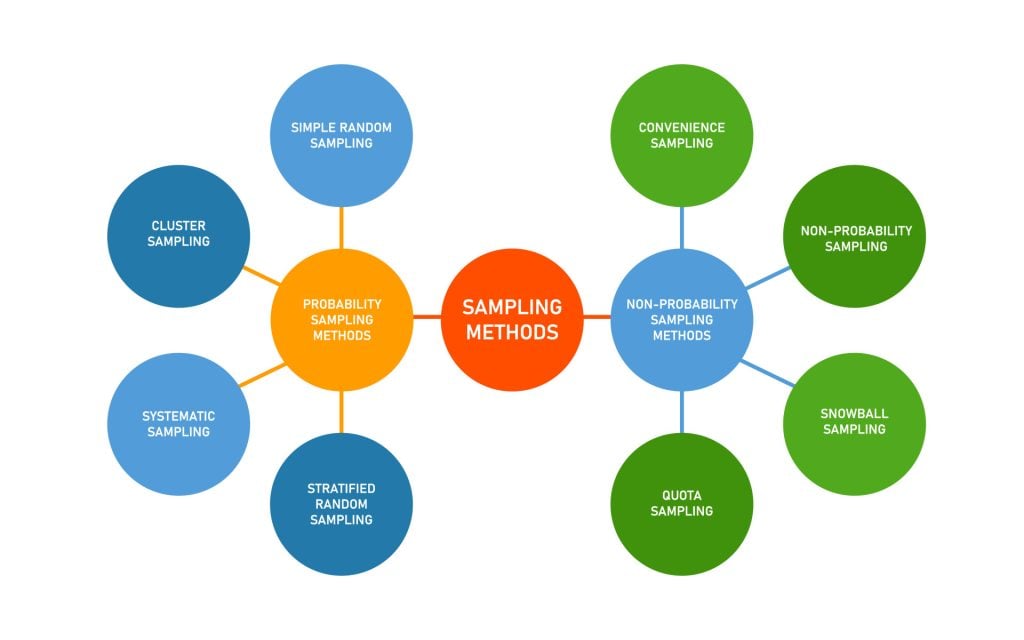

Sampling methods in psychology refer to strategies used to select a subset of individuals (a sample) from a larger population, to study and draw inferences about the entire population. Common methods include random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, and convenience sampling. Proper sampling ensures representative, generalizable, and valid research results.

- Sampling : the process of selecting a representative group from the population under study.

- Target population : the total group of individuals from which the sample might be drawn.

- Sample: a subset of individuals selected from a larger population for study or investigation. Those included in the sample are termed “participants.”

- Generalizability : the ability to apply research findings from a sample to the broader target population, contingent on the sample being representative of that population.

For instance, if the advert for volunteers is published in the New York Times, this limits how much the study’s findings can be generalized to the whole population, because NYT readers may not represent the entire population in certain respects (e.g., politically, socio-economically).

The Purpose of Sampling

We are interested in learning about large groups of people with something in common in psychological research. We call the group interested in studying our “target population.”

In some types of research, the target population might be as broad as all humans. Still, in other types of research, the target population might be a smaller group, such as teenagers, preschool children, or people who misuse drugs.

Studying every person in a target population is more or less impossible. Hence, psychologists select a sample or sub-group of the population that is likely to be representative of the target population we are interested in.

This is important because we want to generalize from the sample to the target population. The more representative the sample, the more confident the researcher can be that the results can be generalized to the target population.

One of the problems that can occur when selecting a sample from a target population is sampling bias. Sampling bias refers to situations where the sample does not reflect the characteristics of the target population.

Many psychology studies have a biased sample because they have used an opportunity sample that comprises university students as their participants (e.g., Asch ).

OK, so you’ve thought up this brilliant psychological study and designed it perfectly. But who will you try it out on, and how will you select your participants?

There are various sampling methods. The one chosen will depend on a number of factors (such as time, money, etc.).

Random Sampling

Random sampling is a type of probability sampling where everyone in the entire target population has an equal chance of being selected.

This is similar to the national lottery. If the “population” is everyone who bought a lottery ticket, then everyone has an equal chance of winning the lottery (assuming they all have one ticket each).

Random samples require naming or numbering the target population and then using some raffle method to choose those to make up the sample. Random samples are the best method of selecting your sample from the population of interest.

- The advantages are that your sample should represent the target population and eliminate sampling bias.

- The disadvantage is that it is very difficult to achieve (i.e., time, effort, and money).

Stratified Sampling

During stratified sampling , the researcher identifies the different types of people that make up the target population and works out the proportions needed for the sample to be representative.

A list is made of each variable (e.g., IQ, gender, etc.) that might have an effect on the research. For example, if we are interested in the money spent on books by undergraduates, then the main subject studied may be an important variable.

For example, students studying English Literature may spend more money on books than engineering students, so if we use a large percentage of English students or engineering students, our results will not be accurate.

We have to determine the relative percentage of each group at a university, e.g., Engineering 10%, Social Sciences 15%, English 20%, Sciences 25%, Languages 10%, Law 5%, and Medicine 15%. The sample must then contain all these groups in the same proportion as the target population (university students).

- The disadvantage of stratified sampling is that gathering such a sample would be extremely time-consuming and difficult to do. This method is rarely used in Psychology.

- However, the advantage is that the sample should be highly representative of the target population, and therefore we can generalize from the results obtained.

Opportunity Sampling

Opportunity sampling is a method in which participants are chosen based on their ease of availability and proximity to the researcher, rather than using random or systematic criteria. It’s a type of convenience sampling .

An opportunity sample is obtained by asking members of the population of interest if they would participate in your research. An example would be selecting a sample of students from those coming out of the library.

- This is a quick and easy way of choosing participants (advantage)

- It may not provide a representative sample and could be biased (disadvantage).

Systematic Sampling

Systematic sampling is a method where every nth individual is selected from a list or sequence to form a sample, ensuring even and regular intervals between chosen subjects.

Participants are systematically selected (i.e., orderly/logical) from the target population, like every nth participant on a list of names.

To take a systematic sample, you list all the population members and then decide upon a sample you would like. By dividing the number of people in the population by the number of people you want in your sample, you get a number we will call n.

If you take every nth name, you will get a systematic sample of the correct size. If, for example, you wanted to sample 150 children from a school of 1,500, you would take every 10th name.

- The advantage of this method is that it should provide a representative sample.

Sample size

The sample size is a critical factor in determining the reliability and validity of a study’s findings. While increasing the sample size can enhance the generalizability of results, it’s also essential to balance practical considerations, such as resource constraints and diminishing returns from ever-larger samples.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability refers to the consistency and reproducibility of research findings across different occasions, researchers, or instruments. A small sample size may lead to inconsistent results due to increased susceptibility to random error or the influence of outliers. In contrast, a larger sample minimizes these errors, promoting more reliable results.

Validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of research findings. For a study to be valid, it should accurately measure what it intends to do. A small, unrepresentative sample can compromise external validity, meaning the results don’t generalize well to the larger population. A larger sample captures more variability, ensuring that specific subgroups or anomalies don’t overly influence results.

Practical Considerations

Resource Constraints : Larger samples demand more time, money, and resources. Data collection becomes more extensive, data analysis more complex, and logistics more challenging.

Diminishing Returns : While increasing the sample size generally leads to improved accuracy and precision, there’s a point where adding more participants yields only marginal benefits. For instance, going from 50 to 500 participants might significantly boost a study’s robustness, but jumping from 10,000 to 10,500 might not offer a comparable advantage, especially considering the added costs.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Convergent Validity: Definition and Examples

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is Research Methodology? Definition, Types, and Examples

Research methodology 1,2 is a structured and scientific approach used to collect, analyze, and interpret quantitative or qualitative data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. A research methodology is like a plan for carrying out research and helps keep researchers on track by limiting the scope of the research. Several aspects must be considered before selecting an appropriate research methodology, such as research limitations and ethical concerns that may affect your research.

The research methodology section in a scientific paper describes the different methodological choices made, such as the data collection and analysis methods, and why these choices were selected. The reasons should explain why the methods chosen are the most appropriate to answer the research question. A good research methodology also helps ensure the reliability and validity of the research findings. There are three types of research methodology—quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method, which can be chosen based on the research objectives.

What is research methodology ?