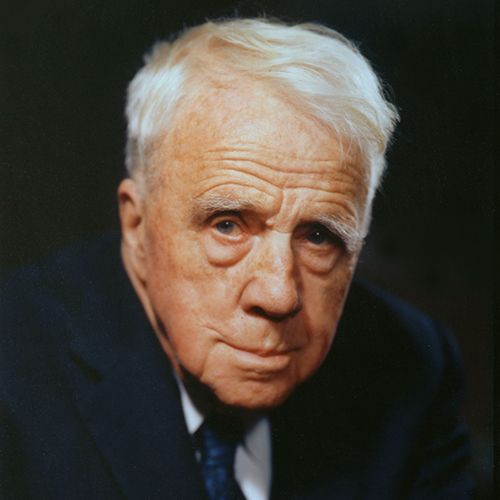

Robert Frost

(1874-1963)

Who Was Robert Frost?

Frost spent his first 40 years as an unknown. He exploded on the scene after returning from England at the beginning of World War I . He died of complications from prostate surgery on January 29, 1963.

Early Years

Frost was born on March 26, 1874, in San Francisco, California. He spent the first 11 years of his life there, until his journalist father, William Prescott Frost Jr., died of tuberculosis.

Following his father's passing, Frost moved with his mother and sister, Jeanie, to the town of Lawrence, Massachusetts. They moved in with his grandparents, and Frost attended Lawrence High School.

After high school, Frost attended Dartmouth College for several months, returning home to work a slew of unfulfilling jobs.

Beginning in 1897, Frost attended Harvard University but had to drop out after two years due to health concerns. He returned to Lawrence to join his wife.

In 1900, Frost moved with his wife and children to a farm in New Hampshire — property that Frost's grandfather had purchased for them—and they attempted to make a life on it for the next 12 years. Though it was a fruitful time for Frost's writing, it was a difficult period in his personal life and followed the deaths of two of his young children.

During that time, Frost and Elinor attempted several endeavors, including poultry farming, all of which were fairly unsuccessful.

Despite such challenges, it was during this time that Frost acclimated himself to rural life. In fact, he grew to depict it quite well, and began setting many of his poems in the countryside.

Frost met his future love and wife, Elinor White, when they were both attending Lawrence High School. She was his co-valedictorian when they graduated in 1892.

In 1894, Frost proposed to White, who was attending St. Lawrence University , but she turned him down because she first wanted to finish school. Frost then decided to leave on a trip to Virginia, and when he returned, he proposed again. By then, White had graduated from college, and she accepted. They married on December 19, 1895.

White died in 1938. Diagnosed with cancer in 1937 and having undergone surgery, she also had had a long history of heart trouble, to which she ultimately succumbed.

Frost and White had six children together. Their first child, Elliot, was born in 1896. Daughter Lesley was born in 1899.

Elliot died of cholera in 1900. After his death, Elinor gave birth to four more children: son Carol (1902), who would commit suicide in 1940; Irma (1903), who later developed mental illness; Marjorie (1905), who died in her late 20s after giving birth; and Elinor (1907), who died just weeks after she was born.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S ROBERT FROST FACT CARD

Early Poetry

In 1894, Frost had his first poem, "My Butterfly: an Elegy," published in The Independent , a weekly literary journal based in New York City .

Two poems, "The Tuft of Flowers" and "The Trial by Existence," were published in 1906. He could not find any publishers who were willing to underwrite his other poems.

In 1912, Frost and Elinor decided to sell the farm in New Hampshire and move the family to England, where they hoped there would be more publishers willing to take a chance on new poets.

Within just a few months, Frost, now 38, found a publisher who would print his first book of poems, A Boy’s Will , followed by North of Boston a year later.

It was at this time that Frost met fellow poets Ezra Pound and Edward Thomas, two men who would affect his life in significant ways. Pound and Thomas were the first to review his work in a favorable light, as well as provide significant encouragement. Frost credited Thomas's long walks over the English landscape as the inspiration for one of his most famous poems, "The Road Not Taken."

Apparently, Thomas's indecision and regret regarding what paths to take inspired Frost's work. The time Frost spent in England was one of the most significant periods in his life, but it was short-lived. Shortly after World War I broke out in August 1914, Frost and Elinor were forced to return to America.

Public Recognition for Frost’s Poetry

When Frost arrived back in America, his reputation had preceded him, and he was well-received by the literary world. His new publisher, Henry Holt, who would remain with him for the rest of his life, had purchased all of the copies of North of Boston . In 1916, he published Frost's Mountain Interval , a collection of other works that he created while in England, including a tribute to Thomas.

Journals such as the Atlantic Monthly , who had turned Frost down when he submitted work earlier, now came calling. Frost famously sent the Atlantic the same poems that they had rejected before his stay in England.

In 1915, Frost and Elinor settled down on a farm that they purchased in Franconia, New Hampshire. There, Frost began a long career as a teacher at several colleges, reciting poetry to eager crowds and writing all the while.

He taught at Dartmouth and the University of Michigan at various times, but his most significant association was with Amherst College , where he taught steadily during the period from 1916 until his wife’s death in 1938. The main library is now named in his honor.

For a period of more than 40 years beginning in 1921, Frost also spent almost every summer and fall at Middlebury College , teaching English on its campus in Ripton, Vermont.

In the late 1950s, Frost, along with Ernest Hemingway and T. S. Eliot , championed the release of his old acquaintance Ezra Pound, who was being held in a federal mental hospital for treason due to his involvement with fascists in Italy during World War II . Pound was released in 1958, after the indictments were dropped.

Famous Poems

Some of Frost’s most well-known poems include:

- “The Road Not Taken”

- “Fire and Ice”

- “Mending Wall”

- “Home Burial”

- “The Death of the Hired Man”

- “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”

- “Acquainted with the Night”

- “Nothing Gold Can Stay”

Pulitzer Prizes and Awards

During his lifetime, Frost received more than 40 honorary degrees.

In 1924, Frost was awarded his first of four Pulitzer Prizes, for his book New Hampshire . He would subsequently win Pulitzers for Collected Poems (1931), A Further Range (1937) and A Witness Tree (1943).

In 1960, Congress awarded Frost the Congressional Gold Medal.

President John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration

At the age of 86, Frost was honored when asked to write and recite a poem for President John F. Kennedy's 1961 inauguration. His sight now failing, he was not able to see the words in the sunlight and substituted the reading of one of his poems, "The Gift Outright," which he had committed to memory.

Soviet Union Tour

In 1962, Frost visited the Soviet Union on a goodwill tour. However, when he accidentally misrepresented a statement made by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev following their meeting, he unwittingly undid much of the good intended by his visit.

On January 29, 1963, Frost died from complications related to prostate surgery. He was survived by two of his daughters, Lesley and Irma. His ashes are interred in a family plot in Bennington, Vermont.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Robert Lee Frost

- Birth Year: 1874

- Birth date: March 26, 1874

- Birth State: California

- Birth City: San Francisco

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Robert Frost was an American poet who depicted realistic New England life through language and situations familiar to the common man. He won four Pulitzer Prizes for his work and spoke at John F. Kennedy's 1961 inauguration.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Harvard University

- Lawrence High School

- Dartmouth College

- Death Year: 1963

- Death date: January 29, 1963

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Boston

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Robert Frost Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/robert-frost

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: December 1, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- The ear does it. The ear is the only true writer and the only true reader.

- I would have written of me on my stone: I had a lover's quarrel with the world.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Civil Rights Activists

Martin Luther King Jr. Didn’t Criticize Malcolm X

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

30 Civil Rights Leaders of the Past and Present

Benjamin Banneker

Marcus Garvey

Madam C.J. Walker

Maya Angelou

Martin Luther King Jr.

17 Inspiring Martin Luther King Quotes

Bayard Rustin

Poems & Poets

Robert Frost

Robert Frost was born in San Francisco, but his family moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1884 following his father’s death. The move was actually a return, for Frost’s ancestors were originally New Englanders, and Frost became famous for his poetry’s engagement with New England locales, identities, and themes. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School, in 1892, as class poet (he also shared the honor of co-valedictorian with his wife-to-be Elinor White), and two years later, the New York Independent accepted his poem entitled “My Butterfly,” launching his status as a professional poet with a check for $15.00. Frost's first book was published around the age of 40, but he would go on to win a record four Pulitzer Prizes and become the most famous poet of his time, before his death at the age of 88. To celebrate his first publication, Frost had a book of six poems privately printed; two copies of Twilight were made—one for himself and one for his fiancee. Over the next eight years, however, he succeeded in having only 13 more poems published. During this time, Frost sporadically attended Dartmouth and Harvard and earned a living teaching school and, later, working a farm in Derry, New Hampshire. But in 1912, discouraged by American magazines’ constant rejection of his work, he took his family to England, where he found more professional success. Continuing to write about New England, he had two books published, A Boy’s Will (1913) and North of Boston (1914) , which established his reputation so that his return to the United States in 1915 was as a celebrated literary figure. Holt put out an American edition of North of Boston in 1915 , and periodicals that had once scorned his work now sought it. Frost’s position in American letters was cemented with the publication of North of Boston, and in the years before his death he came to be considered the unofficial poet laureate of the United States. On his 75th birthday, the US Senate passed a resolution in his honor which said, “His poems have helped to guide American thought and humor and wisdom, setting forth to our minds a reliable representation of ourselves and of all men.” In 1955, the State of Vermont named a mountain after him in Ripton, the town of his legal residence; and at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961, Frost was given the unprecedented honor of being asked to read a poem. Frost wrote a poem called “Dedication” for the occasion, but could not read it given the day’s harsh sunlight. He instead recited “The Gift Outright,” which Kennedy had originally asked him to read, with a revised, more forward-looking, last line. Though Frost allied himself with no literary school or movement, the imagists helped at the start to promote his American reputation. Poetry: A Magazine of Verse published his work before others began to clamor for it. It also published a review by Ezra Pound of the British edition of A Boy’s Will, which Pound said “has the tang of the New Hampshire woods, and it has just this utter sincerity. It is not post-Miltonic or post-Swinburnian or post Kiplonian. This man has the good sense to speak naturally and to paint the thing, the thing as he sees it.” Amy Lowell reviewed North of Boston in the New Republic, and she, too, sang Frost’s praises: “He writes in classic metres in a way to set the teeth of all the poets of the older schools on edge; and he writes in classic metres, and uses inversions and cliches whenever he pleases, those devices so abhorred by the newest generation. He goes his own way, regardless of anyone else’s rules, and the result is a book of unusual power and sincerity.” In these first two volumes, Frost introduced not only his affection for New England themes and his unique blend of traditional meters and colloquialism, but also his use of dramatic monologues and dialogues. “ Mending Wall ,” the leading poem in North of Boston, describes the friendly argument between the speaker and his neighbor as they walk along their common wall replacing fallen stones; their differing attitudes toward “boundaries” offer symbolic significance typical of the poems in these early collections. Mountain Interval marked Frost’s turn to another kind of poem, a brief meditation sparked by an object, person or event. Like the monologues and dialogues, these short pieces have a dramatic quality. “Birches,” discussed above, is an example, as is “ The Road Not Taken ,” in which a fork in a woodland path transcends the specific. The distinction of this volume, the Boston Transcript said, “is that Mr. Frost takes the lyricism of A Boy’s Will and plays a deeper music and gives a more intricate variety of experience.” Several new qualities emerged in Frost’s work with the appearance of New Hampshire (1923) , particularly a new self-consciousness and willingness to speak of himself and his art. The volume, for which Frost won his first Pulitzer Prize, “pretends to be nothing but a long poem with notes and grace notes,” as Louis Untermeyer described it. The title poem, approximately fourteen pages long, is a “rambling tribute” to Frost’s favorite state and “is starred and dotted with scientific numerals in the manner of the most profound treatise.” Thus, a footnote at the end of a line of poetry will refer the reader to another poem seemingly inserted to merely reinforce the text of “New Hampshire.” Some of these poems are in the form of epigrams, which appear for the first time in Frost’s work. “ Fire and Ice ,” for example, one of the better known epigrams, speculates on the means by which the world will end. Frost’s most famous and, according to J. McBride Dabbs, most perfect lyric, “ Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening ,” is also included in this collection; conveying “the insistent whisper of death at the heart of life,” the poem portrays a speaker who stops his sleigh in the midst of a snowy woods only to be called from the inviting gloom by the recollection of practical duties. Frost himself said of this poem that it is the kind he’d like to print on one page followed with “forty pages of footnotes.” West-Running Brook (1928) , Frost’s fifth book of poems, is divided into six sections, one of which is taken up entirely by the title poem. This poem refers to a brook which perversely flows west instead of east to the Atlantic like all other brooks. A comparison is set up between the brook and the poem’s speaker who trusts himself to go by “contraries”; further rebellious elements exemplified by the brook give expression to an eccentric individualism, Frost’s stoic theme of resistance and self-realization. Reviewing the collection in the New York Herald Tribune, Babette Deutsch wrote: “The courage that is bred by a dark sense of Fate, the tenderness that broods over mankind in all its blindness and absurdity, the vision that comes to rest as fully on kitchen smoke and lapsing snow as on mountains and stars—these are his, and in his seemingly casual poetry, he quietly makes them ours.” A Further Range (1936) , which earned Frost another Pulitzer Prize and was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, contains two groups of poems subtitled “Taken Doubly” and “Taken Singly.” In the first, and more interesting, of these groups, the poems are somewhat didactic, though there are humorous and satiric pieces as well. Included here is “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” which opens with the story of two itinerant lumbermen who offer to cut the speaker’s wood for pay; the poem then develops into a sermon on the relationship between work and play, vocation and avocation, preaching the necessity to unite them. Of the entire volume, William Rose Benét wrote, “It is better worth reading than nine-tenths of the books that will come your way this year. In a time when all kinds of insanity are assailing the nations it is good to listen to this quiet humor, even about a hen, a hornet, or Square Matthew. ... And if anybody should ask me why I still believe in my land, I have only to put this book in his hand and answer, ‘Well-here is a man of my country.’” Most critics acknowledge that Frost’s poetry in the 1940s and '50s grew more and more abstract, cryptic, and even sententious, so it is generally on the basis of his earlier work that he is judged. His politics and religious faith, hitherto informed by skepticism and local color, became more and more the guiding principles of his work. He had been, as Randall Jarrell points out, “a very odd and very radical radical when young” yet became “sometimes callously and unimaginatively conservative” in his old age. He had become a public figure, and in the years before his death, much of his poetry was written from this stance. Reviewing A Witness Tree (1942) in Books, Wilbert Snow noted a few poems “which have a right to stand with the best things he has written”: “Come In,” “The Silken Tent,” and “Carpe Diem” especially. Yet Snow went on: “Some of the poems here are little more than rhymed fancies; others lack the bullet-like unity of structure to be found in North of Boston. ” On the other hand, Stephen Vincent Benet felt that Frost had “never written any better poems than some of those in this book.” Similarly, critics were let down by In the Clearing (1962) . One wrote, “Although this reviewer considers Robert Frost to be the foremost contemporary U.S. poet, he regretfully must state that most of the poems in this new volume are disappointing. ... [They] often are closer to jingles than to the memorable poetry we associate with his name.” Another maintained that “the bulk of the book consists of poems of ‘philosophic talk.’ Whether you like them or not depends mostly on whether you share the ‘philosophy.’” Indeed, many readers do share Frost’s philosophy, and still others who do not nevertheless continue to find delight and significance in his large body of poetry. In October, 1963, President John F. Kennedy delivered a speech at the dedication of the Robert Frost Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. “In honoring Robert Frost,” the President said, “we therefore can pay honor to the deepest source of our national strength. That strength takes many forms and the most obvious forms are not always the most significant. ... Our national strength matters; but the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much. This was the special significance of Robert Frost.” The poet would probably have been pleased by such recognition, for he had said once, in an interview with Harvey Breit: “One thing I care about, and wish young people could care about, is taking poetry as the first form of understanding. If poetry isn’t understanding all, the whole world, then it isn’t worth anything.” Frost’s poetry is revered to this day. When a previously unknown poem by Frost titled “War Thoughts at Home,” was discovered and dated to 1918, it was subsequently published in the Fall 2006 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review. The first edition Frost’s Notebooks were published in 2009, and thousands of errors were corrected in the paperback edition years later. A critical edition of his Collected Prose was published in 2010 to broad critical acclaim. A multi-volume series of his Collected Letters is now in production, with the first volume appearing in 2014 and the second in 2016. Robert Frost continues to hold a unique and almost isolated position in American letters. “Though his career fully spans the modern period and though it is impossible to speak of him as anything other than a modern poet,” writes James M. Cox, “it is difficult to place him in the main tradition of modern poetry.” In a sense, Frost stands at the crossroads of 19th-century American poetry and modernism, for in his verse may be found the culmination of many 19th-century tendencies and traditions as well as parallels to the works of his 20th-century contemporaries. Taking his symbols from the public domain, Frost developed, as many critics note, an original, modern idiom and a sense of directness and economy that reflect the imagism of Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell. On the other hand, as Leonard Unger and William Van O’Connor point out in Poems for Study, “Frost’s poetry, unlike that of such contemporaries as Eliot, Stevens, and the later Yeats, shows no marked departure from the poetic practices of the nineteenth century.” Although he avoids traditional verse forms and only uses rhyme erratically, Frost is not an innovator and his technique is never experimental. Frost’s theory of poetic composition ties him to both centuries. Like the 19th-century Romantic poets, he maintained that a poem is “never a put-up job. ... It begins as a lump in the throat, a sense of wrong, a homesickness, a loneliness. It is never a thought to begin with. It is at its best when it is a tantalizing vagueness.” Yet, “working out his own version of the ‘impersonal’ view of art,” as Hyatt H. Waggoner observed, Frost also upheld T.S. Eliot ’s idea that the man who suffers and the artist who creates are totally separate. In a 1932 letter to Sydney Cox, Frost explained his conception of poetry: “The objective idea is all I ever cared about. Most of my ideas occur in verse. ... To be too subjective with what an artist has managed to make objective is to come on him presumptuously and render ungraceful what he in pain of his life had faith he had made graceful.” To accomplish such objectivity and grace, Frost took up 19th-century tools and made them new. Lawrance Thompson has explained that, according to Frost, “the self-imposed restrictions of meter in form and of coherence in content” work to a poet’s advantage; they liberate him from the experimentalist’s burden—the perpetual search for new forms and alternative structures. Thus Frost, as he himself put it in “The Constant Symbol,” wrote his verse regular; he never completely abandoned conventional metrical forms for free verse, as so many of his contemporaries were doing. At the same time, his adherence to meter, line length, and rhyme scheme was not an arbitrary choice. He maintained that “the freshness of a poem belongs absolutely to its not having been thought out and then set to verse as the verse in turn might be set to music.” He believed, rather, that the poem’s particular mood dictated or determined the poet’s “first commitment to metre and length of line.” Critics frequently point out that Frost complicated his problem and enriched his style by setting traditional meters against the natural rhythms of speech. Drawing his language primarily from the vernacular, he avoided artificial poetic diction by employing the accent of a soft-spoken New Englander. In The Function of Criticism, Yvor Winters faulted Frost for his “endeavor to make his style approximate as closely as possible the style of conversation.” But what Frost achieved in his poetry was much more complex than a mere imitation of the New England farmer idiom. He wanted to restore to literature the “sentence sounds that underlie the words,” the “vocal gesture” that enhances meaning. That is, he felt the poet’s ear must be sensitive to the voice in order to capture with the written word the significance of sound in the spoken word. “ The Death of the Hired Man ,” for instance, consists almost entirely of dialogue between Mary and Warren, her farmer-husband, but critics have observed that in this poem Frost takes the prosaic patterns of their speech and makes them lyrical. To Ezra Pound “The Death of the Hired Man” represented Frost at his best—when he “dared to write ... in the natural speech of New England; in natural spoken speech, which is very different from the ‘natural’ speech of the newspapers, and of many professors.” Frost’s use of New England dialect is only one aspect of his often discussed regionalism. Within New England, his particular focus was on New Hampshire, which he called “one of the two best states in the Union,” the other being Vermont. In an essay entitled “Robert Frost and New England: A Revaluation,” W.G. O’Donnell noted how from the start, in A Boy’s Will, “Frost had already decided to give his writing a local habitation and a New England name, to root his art in the soil that he had worked with his own hands.” Reviewing North of Boston in the New Republic, Amy Lowell wrote, “Not only is his work New England in subject, it is so in technique. ... Mr. Frost has reproduced both people and scenery with a vividness which is extraordinary.” Many other critics have lauded Frost’s ability to realistically evoke the New England landscape; they point out that one can visualize an orchard in “After Apple-Picking” or imagine spring in a farmyard in “Two Tramps in Mud Time.” In this “ability to portray the local truth in nature,” O’Donnell claims, Frost has no peer. The same ability prompted Pound to declare, “I know more of farm life than I did before I had read his poems. That means I know more of ‘Life.’” Frost’s regionalism, critics remark, is in his realism, not in politics; he creates no picture of regional unity or sense of community. In The Continuity of American Poetry, Roy Harvey Pearce describes Frost’s protagonists as individuals who are constantly forced to confront their individualism as such and to reject the modern world in order to retain their identity. Frost’s use of nature is not only similar but closely tied to this regionalism. He stays as clear of religion and mysticism as he does of politics. What he finds in nature is sensuous pleasure; he is also sensitive to the earth’s fertility and to man’s relationship to the soil. To critic M.L. Rosenthal, Frost’s pastoral quality, his “lyrical and realistic repossession of the rural and ‘natural,’” is the staple of his reputation. Yet, just as Frost is aware of the distances between one man and another, so he is also always aware of the distinction, the ultimate separateness, of nature and man. Marion Montgomery has explained, “His attitude toward nature is one of armed and amicable truce and mutual respect interspersed with crossings of the boundaries” between individual man and natural forces. Below the surface of Frost’s poems are dreadful implications, what Rosenthal calls his “shocked sense of the helpless cruelty of things.” This natural cruelty is at work in “Design” and in “Once by the Pacific.” The ominous tone of these two poems prompted Rosenthal’s further comment: “At his most powerful Frost is as staggered by ‘the horror’ as Eliot and approaches the hysterical edge of sensibility in a comparable way. ... His is still the modern mind in search of its own meaning.” The austere and tragic view of life that emerges in so many of Frost’s poems is modulated by his metaphysical use of detail. As Frost portrays him, man might be alone in an ultimately indifferent universe, but he may nevertheless look to the natural world for metaphors of his own condition. Thus, in his search for meaning in the modern world, Frost focuses on those moments when the seen and the unseen, the tangible and the spiritual intersect. John T. Napier calls this Frost’s ability “to find the ordinary a matrix for the extraordinary.” In this respect, he is often compared with Emily Dickinson and Ralph Waldo Emerson , in whose poetry, too, a simple fact, object, person, or event will be transfigured and take on greater mystery or significance. The poem “ Birches” is an example: it contains the image of slender trees bent to the ground temporarily by a boy’s swinging on them or permanently by an ice-storm. But as the poem unfolds, it becomes clear that the speaker is concerned not only with child’s play and natural phenomena, but also with the point at which physical and spiritual reality merge. Such symbolic import of mundane facts informs many of Frost’s poems, and in “Education by Poetry” he explained: “Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, ‘grace’ metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have. Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another. ... Unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere.”

- North America

- U.S., New England

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

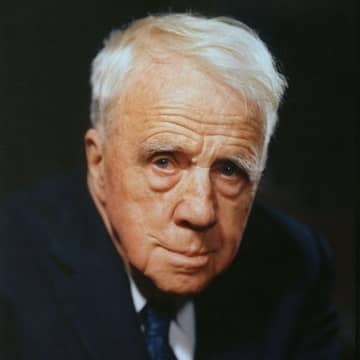

Robert Frost

Robert Frost was born on March 26, 1874, in San Francisco, where his father, William Prescott Frost, Jr., and his mother, Isabelle Moodie, had moved from Pennsylvania shortly after marrying. After the death of his father from tuberculosis when Frost was eleven years old, he moved with his mother and sister, Jeanie, who was two years younger, to Lawrence, Massachusetts. He became interested in reading and writing poetry during his high school years in Lawrence, enrolled at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire in 1892 and, later, at Harvard University, though he never earned a formal degree.

Frost drifted through a string of occupations after leaving school, working as a teacher, cobbler, and editor of the Lawrence Sentinel . His first published poem, “My Butterfly,” appeared on November 8, 1894 in the New York newspaper The Independent .

In 1895, Frost married Elinor Miriam White, with whom he’d shared valedictorian honors in high school, and who was a major inspiration for his poetry until her death in 1938. The couple moved to England in 1912, after they tried and failed at farming in New Hampshire. It was abroad where Frost met and was influenced by such contemporary British poets as Edward Thomas , Rupert Brooke , and Robert Graves . While in England, Frost also established a friendship with the poet Ezra Pound , who helped to promote and publish his work.

By the time Frost returned to the United States in 1915, he had published two full-length collections, A Boy’s Will (Henry Holt and Company, 1913) and North of Boston (Henry Holt and Company, 1914), thereby establishing his reputation. By the 1920s, he was the most celebrated poets in America, and with each new book—including New Hampshire (Henry Holt and Company, 1923), A Further Range (Henry Holt and Company, 1936), Steeple Bush (Henry Holt and Company, 1947), and In the Clearing (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1962)—his fame and honors, including four Pulitzer Prizes, increased. Frost served as a consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress from 1958–59. In 1962, he was presented the Congressional Gold Medal.

Though Frost’s work is principally associated with the life and landscape of New England—and, though he was a poet of traditional verse forms and metrics who remained steadfastly aloof from the poetic movements and fashions of his time—Frost is anything but merely a regional poet. The author of searching, and often dark, meditations on universal themes, he is a quintessentially modern poet in his adherence to language as it is actually spoken, in the psychological complexity of his portraits, and in the degree to which his work is infused with layers of ambiguity and irony.

In a 1970 review of The Poetry of Robert Frost , the poet Daniel Hoffman describes Frost’s early work as “the Puritan ethic turned astonishingly lyrical and enabled to say out loud the sources of its own delight in the world,” and comments on Frost’s career as the “American Bard”: “He became a national celebrity, our nearly official poet laureate, and a great performer in the tradition of that earlier master of the literary vernacular, Mark Twain.”

President John F. Kennedy, at whose inauguration Frost delivered a poem, said of the poet, “He has bequeathed his nation a body of imperishable verse from which Americans will forever gain joy and understanding.” And famously, “He saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself. When power leads man towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

Robert Frost lived and taught for many years in Massachusetts and Vermont, and died in Boston on January 29, 1963.

Related Poets

E. E. Cummings

Edward Estlin Cummings is known for his radical experimentation with form, punctuation, spelling, and syntax; he abandoned traditional techniques and structures to create a new, highly idiosyncratic means of poetic expression.

Wallace Stevens

Wallace Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on October 2, 1879. He attended Harvard University as an undergraduate from 1897 to 1900.

Born in London in 1882, Mina Loy has been labelled as a Futurist, Dadaist, Surrealist, feminist, conceptualist, modernist, and post-modernist. Known for both her poetry and visual art, she died in Colorado in 1966.

José Garcia Villa

José Garcia Villa was born in Manila in 1908. He published several poetry collections in the Philippines and in the United States, including Have Come, Am Here (Viking Press, 1942), which was a finalist for the 1943 Pulitzer Prize. He died in New York City in 1997.

William Carlos Williams

Poet, novelist, essayist, and playwright William Carlos Williams is often said to have been one of the principal poets of the Imagist movement.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was a New Zealander poet, essayist, short story writer, and journalist from the Modernist movement.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Biography of Robert Frost

America's Farmer/Philosopher Poet

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- B.A., English and American Literature, University of California at Santa Barbara

- B.A., English, Columbia College

Robert Frost — even the sound of his name is folksy, rural: simple, New England, white farmhouse, red barn, stone walls. And that’s our vision of him, thin white hair blowing at JFK’s inauguration, reciting his poem “The Gift Outright.” (The weather was too blustery and frigid for him to read “Dedication,” which he had written specifically for the event, so he simply performed the only poem he had memorized. It was oddly fitting.) As usual, there’s some truth in the myth — and a lot of back story that makes Frost much more interesting — more poet, less icon Americana.

Early Years

Robert Lee Frost was born March 26, 1874 in San Francisco to Isabelle Moodie and William Prescott Frost, Jr. The Civil War had ended nine years previously, Walt Whitman was 55. Frost had deep US roots: his father was a descendant of a Devonshire Frost who sailed to New Hampshire in 1634. William Frost had been a teacher and then a journalist, was known as a drinker, a gambler and a harsh disciplinarian. He also dabbled in politics, for as long as his health allowed. He died of tuberculosis in 1885, when his son was 11.

Youth and College Years

After the death of his father, Robert, his mother and sister moved from California to eastern Massachusetts near his paternal grandparents. His mother joined the Swedenborgian church and had him baptized in it, but Frost left it as an adult. He grew up as a city boy and attended Dartmouth College in 1892, for just less than a semester. He went back home to teach and work at various jobs including factory work and newspaper delivery.

First Publication and Marriage

In 1894 Frost sold his first poem, “My Butterfly,” to The New York Independent for $15. It begins: “Thine emulous fond flowers are dead, too, / And the daft sun-assaulter, he / That frighted thee so oft, is fled or dead.” On the strength of this accomplishment, he asked Elinor Miriam White, his high school co-valedictorian, to marry him: she refused. She wanted to finish school before they married. Frost was sure that there was another man and made an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia. He came back later that year and asked Elinor again; this time she accepted. They married in December 1895.

Farming, Expatriating

The newlyweds taught school together until 1897, when Frost entered Harvard for two years. He did well, but left school to return home when his wife was expecting a second child. He never returned to college, never earned a degree. His grandfather bought a farm for the family in Derry, New Hampshire (you can still visit this farm). Frost spent nine years there, farming and writing — the poultry farming was not successful but the writing drove him on, and back to teaching for a couple more years. In 1912, the Frost gave up the farm, sailed to Glasgow, and later settled in Beaconsfield, outside London.

Success in England

Frost’s efforts to establish himself in England were immediately successful. In 1913 he published his first book, A Boy’s Will , followed a year later by North of Boston . It was in England that he met such poets as Rupert Brooke, T.E. Hulme and Robert Graves, and established his lifelong friendship with Ezra Pound, who helped to promote and publish his work. Pound was the first American to write a (favorable) review of Frost’s work. In England Frost also met Edward Thomas, a member of the group known as the Dymock poets; it was walks with Thomas that led to Frost’s beloved but “tricky” poem, “The Road Not Taken.”

The Most Celebrated Poet in North America

Frost returned to the U.S. in 1915 and, by the 1920s, he was the most celebrated poet in North America, winning four Pulitzer Prizes (still a record). He lived on a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, and from there carried on a long career writing, teaching and lecturing. From 1916 to 1938, he taught at Amherst College, and from 1921 to 1963 he spent his summers teaching at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference at Middlebury College, which he helped found. Middlebury still owns and maintains his farm as a National Historic site: it is now a museum and poetry conference center.

Upon his death in Boston on January 29, 1963, Robert Frost was buried in the Old Bennington Cemetery, in Bennington, Vermont. He said, “I don’t go to church, but I look in the window.” It does say something about one’s beliefs to be buried behind a church, although the gravestone faces in the opposite direction. Frost was a man famous for contradictions, known as a cranky and egocentric personality – he once lit a wastebasket on fire on stage when the poet before him went on too long. His gravestone of Barre granite with hand-carved laurel leaves is inscribed, “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world

Frost in the Poetry Sphere

Even though he was first discovered in England and extolled by the archmodernist Ezra Pound, Robert Frost’s reputation as a poet has been that of the most conservative, traditional, formal verse-maker. This may be changing: Paul Muldoon claims Frost as “the greatest American poet of the 20th century,” and the New York Times has tried to resuscitate him as a proto-experimentalist: “ Frost on the Edge ,” by David Orr, February 4, 2007 in the Sunday Book Review.

No matter. Frost is secure as our farmer/philosopher poet.

- Frost was actually born in San Francisco.

- He lived in California till he was 11 and then moved East — he grew up in cities in Massachusetts.

- Far from a hardscrabble farming apprenticeship, Frost attended Dartmouth and then Harvard. His grandfather bought him a farm when he was in his early 20s.

- When his attempt at chicken farming failed, he served a stint teaching at a private school and then he and his family moved to England.

- It was while he was in Europe that he was discovered by the US expat and Impresario of Modernism, Ezra Pound, who published him in Poetry .

“Home is the place where, when you have to go there, They have to take you in....” --“The Death of the Hired Man”

“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall....” --“ Mending Wall ”

“Some say the world will end in fire, Some say in ice.... --“ Fire and Ice”

A Girl’s Garden

Robert Frost (from Mountain Interval , 1920)

A neighbor of mine in the village Likes to tell how one spring When she was a girl on the farm, she did A childlike thing.

One day she asked her father To give her a garden plot To plant and tend and reap herself, And he said, “Why not?”

In casting about for a corner He thought of an idle bit Of walled-off ground where a shop had stood, And he said, “Just it.”

And he said, “That ought to make you An ideal one-girl farm, And give you a chance to put some strength On your slim-jim arm.”

It was not enough of a garden, Her father said, to plough; So she had to work it all by hand, But she don’t mind now.

She wheeled the dung in the wheelbarrow Along a stretch of road; But she always ran away and left Her not-nice load.

And hid from anyone passing. And then she begged the seed. She says she thinks she planted one Of all things but weed.

A hill each of potatoes, Radishes, lettuce, peas, Tomatoes, beets, beans, pumpkins, corn, And even fruit trees

And yes, she has long mistrusted That a cider apple tree In bearing there to-day is hers, Or at least may be.

Her crop was a miscellany When all was said and done, A little bit of everything, A great deal of none.

Now when she sees in the village How village things go, Just when it seems to come in right, She says, “I know!

It’s as when I was a farmer——” Oh, never by way of advice! And she never sins by telling the tale To the same person twice.

- A Guide to Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken"

- 10 Classic Poems for Halloween

- 10 Classic Poems on Gardens and Gardening

- Robert Frost's 'Acquainted With the Night'

- Understanding 'The Pasture' by Robert Frost

- Presidential Inauguration Poems

- Poets Laureate of the U.S.A.

- William Wordsworth

- Reading Notes on Robert Frost’s Poem “Nothing Gold Can Stay”

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- 18 Classic Poems of the Christmas Season

- A Collection of Classic Love Poetry for Your Sweetheart

- 7 Classic Poems for Fathers

- 41 Classic and New Poems to Keep You Warm in Winter

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- 14 Classic Poems Everyone Should Know

A poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom.

- Robert Frost

Robert Frost and his Poems

Robert Frost was born on March 26th, 1874. One of the most celebrated poets in America, Robert Frost was an author of searching and often dark meditations on universal themes and a quintessentially modern poet in his adherence to language as it is actually spoken, in the psychological complexity of his portraits, and in the degree to which his work is infused with layers of ambiguity and irony. Robert Frost's work was highly associated with rural life in New England. The poet often uses the New England setting to explore complicated philosophical and social themes. As a well-known and often-quoted poet, Robert Frost was highly honored during his presence on earth, receiving 4 Pulitzer Prizes.

Robert Frost's father was a former teacher who later turned newspaperman. His father was also known to be a gambler, a hard drinker, and a harsh disciplinarian. For as long as he allowed, he had a passion for politics. Robert Frost resided in California until the age of eleven. Frost moved with his mother and sister to eastern Massachusetts, after the death of his father.

Frost's mother later joined the Swedenborgian church and had the poet baptized in it. As an adult, Frost left the faith of his mother. As a city boy, Frost grew up understanding so many things in life and had his first poem published in Lawrence, Massachusetts. In 1892, he attended Dartmouth College for just less than a semester. While at Dartmouth College, Frost joined the fraternity called Theta Delta Chi. Frost went back to his hometown to work and teach at various jobs including newspaper delivery and factory assignment. Robert Frost sold his first poem titled My Butterfly in 1894 to The Independent at the rate of 15 dollars.

Frost was proud of the success the poem brought to him and went on to ask Elinor Miriam White's hands in marriage. Both Elinor and Frost had graduated co-valedictorians from their high-school and remained in contact with one another. However, Elinor Miriam White refused the notion to marry Frost, mentioning that her education was important first. Robert Frost felt another man was occupying his position in White's heart and went on an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia. He came back in 1895 and asked Elinor White again to marry him. The same year, both of them became happily married.

The couple taught school together until the year 1897. Robert Frost later entered Harvard University for 2 years. His records were good, but he decided to go back home because Elinor is expecting her second child. Frost's grandfather bought a farmer in Derry, New Hampshire for the young couple. Frost remained there for a space of 9 years and wrote so many of the poems that will make up his first works. While attempting to pick up the poultry farming business, the whole thing went unsuccessful. Frost was forced to settle for another at Pinkerton Academy, a secondary school.

Roberts Frost went to Glasgow with his family in 1912 and later lived in Beaconsfield. In the next year, Frost published his first book titled A Boy's Will. In England, Robert Frost made important contacts including T. E. Hulme, Edward Thomas, and Ezra Pound. The mentioned names were the first Americans to write a favorable review of Robert Frost's work. Some of the first pieces of his poet work were written while living in England. In 1915, Robert Lee returned to America and purchased a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire. That same year, Frost launched a career of writing, lecturing and teaching.

Frost became an English professor at Amherst College from 1916-1938. While a professor at Amherst College, he advised his writing students to always bring the notion of the human voices to their craft. From 1921 and the next forty-two years of his life, he had three great expectations. During summers, Frost spent time teaching at the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College in Ripton, Vermont. Nevertheless, Middlebury College still owns and managed Frost's farm. Middlebury College as managed his farm as a National Historic Site located near the Bread Loaf campus. He also represented the United States of America on several official missions. On January 20th, 1961 inauguration of President John F. Kennedy, Frost recited a poem titled The Gift Outright .

Over the course of his career, he became popular for poems involving the interplay of voices such as Death of the Hired Man or dramas. To be factual and upfront here, Frost's work was highly well-known among so many people and it remained so. Among Frost's popular shorter poems are Mending Wall , Directive , Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening , The Road Not Taken , Nothing Gold Can Stay , Fire and Ice , Birches , After Apple Picking . Robert Frost won the Pulitzer Prize at 4 different times. This is an achievement unequaled by any other American poet.

Robert Frost finally died in Boston on January 29th, 1963. He was happily buried in the Old Bennington Cemetery, Vermont. Harvard's 1965 alumni archive dictates that Frost had an honorary degree in the university. He also received honorary degrees from Oxford, Bates College, and Cambridge universities. History records that Robert Frost was the first person to receive 2 honorary degrees from Dartmouth College. During his lifetime, the main library of Amherst College and as well as the Robert Frost Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia were named after him.

Since the nineteenth century, American poetry has developed in two main streams; the first began with the free, pulsating, incantatory verse of Walt Whitman , while the second started with the experiment and innovation of Emily Dickinson . Frost owes a little to both traditions, though he has, on the whole, tended to work from and continue an earlier tradition and thus create a tradition of his own. Records have shown that Frost was a farmer, a poet, a rare combination. As a farmer, Frost only spent ten years in the occupation. Frost's works have been perfectly divided into 9 collections or books. There are several great poems found in the list such as Mountain Interval, North of Boston, and New Hampshire. Frost usually displays the life occurring in New England and showcased it via his poems. With the comprehensive explanation of this article, you are sure to discover Robert Frost's life and his achievement in poems. Frost is worth calling a legend after reading through the great work of his hand.

IMAGES