New study reveals gender bias in sport research. It’s yet another hurdle to progress in women’s sport

Research Fellow & Psychologist, Mental Health in Elite Sports, The University of Melbourne

Senior Research Fellow, Biostatistician, Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne

Associate Professor & Clinical Psychologist, Mental Health in Elite Sports, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

Courtney Walton receives funding through a McKenzie Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at the University of Melbourne. He advises a number of elite sports codes and organisations nationally.

Caroline Gao receives salary support from the Department of Health, State Government of Victoria for unrelated projects. She is an investigator on projects funded by NHMRC, NIH, HCF and MRFF. She is affiliated with Orygen and Monash University.

Simon Rice receives funding from the NHMRC, MRFF and The University of Melbourne. He advises a number of elite sports codes and organisations internationally.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Throughout history, sports have been guilty of prioritising certain groups at the exclusion of others. There has been a pervasive idea that being an athlete requires the demonstration of traditionally masculine traits. Any individual not doing so was, and often still is, susceptible to being harassed, sidelined, or ostracised.

Indeed, femininity has historically been considered nonathletic. Research finds some athletes describe a perception that being a “woman” and an “athlete” are almost opposing identities .

For these reasons and more, women’s sport has been held back in ways that men’s sport has not. While progress is certainly now being made, our new research , published this week, finds large gender gaps persist in sports research.

We found sport psychology research studies – which inform the strategies athletes use to reach peak performance – have predominantly used male participants.

For example, across the sport psychology research we looked at between 2010 and 2020, 62% of the participants were men and boys. Further, around 22% of the sport psychology studies we examined had samples with only male participants. In contrast, this number was just 7% for women and girls.

Women may experience sport and exercise differently from men. As in other areas of medicine, an evidence base that’s predominately informed by men’s experiences and bodies will lead to insufficient, ineffective outcomes and recommendations for women.

Some progress has been made

Progress in women’s sport is evident, and continues every year. Gender gaps across recreational and professional sport are slowly narrowing.

Girls’ involvement in sport continues to grow, with the number participating in high school sports in the United States increasing by 262% between 1973 and 2018 . In Australia, participation in sport among women and girls between 2015-2019 grew at a faster rate than among men and boys .

Improved opportunity and exposure has also occurred in professional settings, and public interest has increased significantly. For example, the 2020 Women’s Cricket World Cup saw attendance records tumble, with the final played at the MCG in front of 86,174 fans .

Many sports now enter a complex new era of professionalisation, as we’re seeing in AFLW .

Despite positive trends, critical issues remain.

Read more: The Tokyo Olympics are billed as the first gender equal Games, but women still lack opportunities in sport

Gender bias in research

Any growth in women’s sport must be supported by the underlying evidence base that informs it.

As mental health researchers in the field of elite sport, we aim to make real-world impacts through rigorous applied research. Our team has previously explored gendered mental health experiences among elite athletes, finding women report more significant symptoms of mental ill-health and more frequent negative events like discrimination or financial hardship .

Research like this is critical for informing the services and systems which support peak performance. But the research has to represent its target, or else progress will be limited.

It’s now well understood that the field of medical and scientific research is rife with examples of the ways in which unequal participation by gender has caused negative health effects. With men’s experiences and bodies considered the norm , inaccurate understanding of causes, tools, and treatments have been frequent.

Medical and scientific research in sport is not exempt.

Our findings

As sports become increasingly competitive and pressurised, sport psychology is critical to supporting athletes within these high-stress environments.

Following concerns about gender bias in scientific research, we wanted to understand whether the field of sport and exercise psychology was appropriately representative.

We recorded the gender of study participants across research published in key sport and exercise psychology journals in 2010, 2015 and 2020, to estimate gender balance over the last decade. This included studies on topics such as: physical and mental health, personality and motivation, coaching and athlete development, leadership, and mental skills.

Across more than 600 studies and nearly 260,000 participants, there were significant levels of gender imbalance.

This imbalance varied, depending on the area being investigated. While sport psychology research focuses on performance and athletes, exercise psychology is more focused on areas of health and participation. Our findings showed that the likelihood of including male rather than female participants in sport psychology studies was almost four times as high as for exercise psychology.

We also identified that those studies which specifically explored themes relating to performance (such as coaching, mental skills, or decision-making) all featured samples with fewer women and girls, as compared to those focused on topics like health, well-being, or activism.

What our findings mean

Our findings, along with those of others , hint at a number of worrying conclusions.

Women and girls in sport are likely to be instructed in strategies and approaches informed by research that does not sufficiently represent them.

Among many factors, topics like coaching methods, injury management, and performance psychology are critical to sports performance. For some or all of these, women athletes’ experiences may differ from those of men.

Changes to policy have made a significant difference to gender equity in sport. But researchers and funding bodies must follow suit, ensuring we develop the understanding and methods to properly represent all groups we seek to serve. Only then can women’s sport truly flourish.

- Sport science

- Sport psychology

- Gender bias

- Gender bias in academia

- Exercise psychology

- Gender bias in medicine

- Gender bias in sports

Data Manager

Research Support Officer

Director, Social Policy

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Global Observatory for Gender Equality & Sport MSI · Avenue de Rhodanie 54 · 1007 Lausanne · Switzerland

Global Observatory for Gender Equality & Sport

Do you want to join our global network, collaborate with us or contribute data, publications, and expertise?

Call for Expressions of Interest

Latest News

18.12.2023 Strategising for Gender Equality Data in PE, Physical Activity and Sport On Monday, November 27, and Tuesday, November 28, 2023, the Global Observatory on Gender Equality in Sport (GOGES) in partnership with UNESCO hosted a working meeting at UNESCO headquarters in [...] Event

Enquiring, engaging, and capacity building towards a gender-equal, just, and inclusive future for all in sport, and through sport+

The Global Observatory for Gender Equality & Sport is a global convenor and repository of research and expertise on gender equality and sport, physical education, and physical activity – or sport+ for short.

Building on the existing gender and sport movements across the world, we are dedicated to closing knowledge gaps and enabling actors to overcome global and systemic inequalities to advance gender equality for children and women in all their diversity in and through sport.

A not-for-profit organisation, we are championed by UNESCO as an outcome of a process initiated at its 4th International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport (MINEPS IV) in 2003, and confirmed in 2017 at MINEPS VI within the framework of the Kazan Action Plan (KAP) welcomed by 195 countries.

We are currently hosted by an Incubating Association composed of representatives from the Canton of Vaud , the City of Lausanne , and the University of Lausanne (UNIL) and supported by the Swiss government . With headquarters in Lausanne, the home of international sport, we, as the first-ever Global Observatory for Gender Equality & Sport, are in a prime location to convene and connect with international sport organisations, UN entities and policymakers as we endeavour to bridge the gap between those who develop policy and those who are impacted by them.

Enquire Through data collation, fact-finding, and evidence-based research.

Engage Through connection, dialogue, and mediation.

Enable Through education, capacity-building and advisory.

As a platform of knowledge-exchange, we equip individuals, organisations, and governments across the world with the necessary expertise, networks and tools on gender equality and sport+ to address inequalities and drive positive and transformative social change.

Follow in Linkedin Dr Lombe Mwambwa, PhD Research Director

Follow in Linkedin Kreena Govender Senior Strategy and Policy Adviser

Get involved & contact us

Do you have a question, request, or gender and sport-related issue you wish to discuss? Do you want to join our global network, collaborate with us or contribute data, publications, and expertise? Get in touch!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2016

Gendered performances in sport: an embodied approach

- Ian Wellard 1

Palgrave Communications volume 2 , Article number: 16003 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

7 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

Despite significant advances in recent years, gender inequalities remain apparent within the context of sport participation and engagement. One of the problems, however, when addressing gender issues in sport is the continued assumption by many sport practitioners that the experiences of women and men will always be different because of perceived physiological characteristics. Adopting a focus based solely on perceived gendered differences often overlooks the importance of recognizing individual experience and the prevailing social influences that impact on participation such as age, class, race and ability. An embodied approach, as well as seeking to move beyond mind/body dualisms, incorporates the physiological with the social and psychological. Therefore, it is suggested that, although considerations of gender remain important, they need to be interpreted alongside other interconnecting and influential (at varying times and occasions) social and physical factors. It is argued that taking the body as a starting point opens up more possibilities to manoeuvre through the mine field that is gender and sport participation. The appeal of an embodied approach to the study of gender and sport is in its accommodation of a wider multidisciplinary lens. Particularly, by acknowledging the subjective, corporeal, lived experiences of sport engagement, an embodied approach offers a more flexible starting point to negotiate the theoretical and methodological challenges created by restrictive discourses of difference.

Similar content being viewed by others

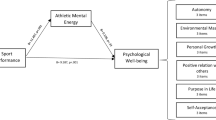

The role of the six factors model of athletic mental energy in mediating athletes’ well-being in competitive sports

The influence of sexual activity on athletic performance: a systematic review and meta-analyses

Subjective experience, self-efficacy, and motivation of professional football referees during the COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction.

Debates relating to the role of gender in sport participation continue to be contested. Although, more recently, there have been significant advances in the ways that women are able to take part in sports, it is still difficult to provide convincing arguments that women do have equal opportunities. One of the problems, however, when addressing gender issues in sport is the continued assumption by many sport practitioners that the experiences of women and men will always be different because of perceived physiological characteristics. Adopting a focus based on perceived differences often overlooks the importance of recognizing individual experience and the prevailing social influences that impact on participation.

In the majority of studies of gender within the context of sport, the focus tends to be on the experiences of women. Historically, the disparity between men and women in terms of the opportunities to participate in sport is unquestioned and has been documented in detail ( Hargreaves, 1994 ). However, the inequitable treatment that women have experienced needs to be understood alongside the influence of other social discourses such as ability, age, class and race. These (and others) can be seen as significant factors contributing to present patterns of participation and inclusion. Further fuelling this complexity are more recent discourses developed within contemporary, populist thinking about gender informed by neo-liberal claims that women are “empowered” and free to choose their own identities ( Phipps, 2014 ). Although these discourses can be seen to be seductive in that they encourage individual assessments of being “in control”, they tend to operate in a performative way ( Butler, 1993 ) where simplistic binary divisions between men and women remain uncontested. Bearing this in mind, the discussion in this article focusses on exploring ways to think beyond “just” gender when thinking about sport participation, at the same time keeping the central argument of inclusion at the heart of the debate.

In 2004, I was involved in a review of research exploring girls’ participation in sport and physical activities for the World Health Organisation (WHO) ( Bailey et al., 2004 ). The report explored current research within the field and highlighted evidence to suggest that, although there was enthusiasm among girls to take part in sports, many were still facing barriers because of a range of complex and competing external social factors. In particular, areas such as family life, friendship patterns and school sport were significant influences on how the girls could participate.

Although the focus in the WHO research was on girls’ participation in sport and physical activity, an important part of the analysis was the recognition of girls as children and young people and, as such, part of a broader discourse of childhood ( Jenks, 2005 ; Christiensen and James, 2008 ; Runswick-Cole and Goodley, 2011 ). Consequently, girls’ experiences of sport and physical activity could not be understood wholly in terms of gender, but as part of wider social thinking that included understandings of children’s physical, psychological and social development as well as discourses of health and well-being shaped through centuries of political, religious and scientific thinking. Nevertheless, current social constructions of what a “normal” or “healthy” girl/boy/child should look like continue to be formulated in contested ways. Therefore, it is suggested within this article that a way to unravel the complexities of gender within the context of sport and physical activity is to recognize the centrality of the body, so that the multiple social factors that influence and impact on how an individual is freely able (or not) to participate can be recognized and acted upon. In doing so, it is suggested that, although considerations of gender remain important, they need to be considered alongside other interconnecting and influential (at varying times and occasions) social factors such as age, class, race, religion and (dis)ability.

In recent years the social sciences has experienced a “somatic turn” where the body has been bought back into the field of sociology ( Frank, 1991 ; Shilling, 1993 ). Subsequent embodied approaches could be considered as a response to calls to incorporate not just a “sociology of the body” that analyses and writes about “the” body but an embodied sociology that emerges through living, breathing, corporeal emotional beings ( Inckle, 2010 ). Within the context of sport, while the discursive structures operating on the body revealed by Foucault (1979) and many subsequent post-structuralist accounts ( Butler, 1993 ; Markula and Pringle, 2006 ) have been extensively debated, there does seem room for more discussion about embodied experience, in particular, the ways in which individuals create corporeal understandings of their own bodies and in turn develop understandings of their own physical identities as well as others. However, rather than being a distinct discipline in its own right, an embodied approach might be more usefully viewed as a “frame of mind” or a specific orientation to the research process. In this way, it draws upon reflexivity in that consciousness of the embodied or, as Woodward (2015) describes, “enfleshed” aspects are considered significant in any attempts to understand human experience. The very fact that to engage in embodied research one needs to accommodate the physiological, the psychological, the sociological, and the temporal and spatial elements means that the researcher can accommodate a range of disciplinary perspectives. Akinleye (2015) suggests that embodiment moves meaning making beyond linear constructs, which ultimately helps us move from distinctions and separations of mind and body or time and space and allows us to fuse what have previously been considered separate realms and also move back and forth between ideas, experiences and thoughts.

Awareness of these broader discourses (of, for example, the able body, gender and sexuality) allows the researcher (and practitioner) to consider the implications that their embodied self has on their proposed activities as well as revealing the invariably limited ways in which the body can be expressed. This is where Pronger’s (2002) discussion about the limits that are placed on individuals through dominating discourses can help us negotiate fears of overstepping the mark. In terms of an embodied approach, there is more potential to look beyond the limits. In doing so, embodied approaches might provide the starting to point to reveal such limits and develop ways to counter uncritical neo-liberal arguments about sport and sport capital that are often offered as positive and unproblematic especially in relation to the benefits of sport. Taking an embodied or enfleshed ( Woodward, 2015 ) way of thinking helps us to accommodate the more nitty-gritty aspects of our everyday existence. Often this everyday existence is about negotiating and managing at an individual level as well as a social level the different experiences that are both positive and not so positive. As such things like pain, shame, pleasure, aggression, social status, poverty and so on have to be factored in to any of these considerations. The central foundation for neo-liberal arguments is generally based on the relationship between the benefits of sport and the economy. This focus often overlooks (or consciously ignores) the embodied experience of the individual in its attempt to explore broader economic and political agendas. An embodied approach allows for consideration of the influence of these (and other) forms of knowledge structure but more in line with the effect they have on the individual experience or, in other words, the broader everyday reality of embodied existence.

Body performances in sport

In contemporary sports the “type” of body that one has plays a central role in determining who the appropriate participants should be. It is worthwhile to note at this stage that when I speak about sport, it is within a “Western” formulation, as described by Hargreaves (1986) , one that has a historical trajectory that has constructed a particular understanding of sport as a male arena ( Hargreaves, 1986 ; Messner, 1992 ; Wellard, 2009 ). This formulation of sport and the subsequent relationship to an understanding of contemporary “Western” masculinity need to be considered within the context of what Connell (2007 : 44), in Southern Theory, describes the “northernness” of general theory and, in particular, what she terms a “metropolitan geo-political location”. She critiques the lack of recognition of the northern geo-political location and along with it the failure to recognize many alternate ways of thinking or being, which derive from non-Western cultures. In particular, it is empirical knowledge deriving from the “Metropole” that constitutes the erasure of the experience of a majority of human kind from having an influence in the construction of social thought. As much as I support Connell’s viewpoint, I cannot escape from the fact that the material generated in the research that I have been involved in is located within the Metropole that Connell describes. However, recognition of this position, combined with the knowledge that there are other ways of being, provides an opportunity to analyse the material with a broader viewpoint, much in the same way that feminist research has taught us to constantly take into consideration the gendered dynamics of social interactions and identity formation ( Woodward, 1997 ). Therefore, I have attempted to remain aware of the limits of the Metropole, especially as the version of sport that prevails does have its roots firmly entrenched in Western thinking. Nevertheless, it does not mean that the ideas developed are not relevant, as they seek to explore issues that have yet to be fully understood. Exposing the constant conflicting interpretations of what sport should be (and to whom) provides a way of incorporating broader ideas, particularly so in the case of school sport and physical education, where participation is mandatory for young people, although the benefits or outcomes are not necessarily the same ( Wellard, 2006 ). However, the point I am making in this article is that sport participation is not solely based on the actual physical ability to perform movements related to the specific sporting event. Bodily performance provides a means of demonstrating other normative social requirements that relate to the prevalent codes of gender and sexual identity, both inside and outside the sporting arena. There is, however, within the context of sport a form of what I have termed “expected sporting masculinity” ( Wellard, 2009 ) that is expressed through bodily displays or performances. These bodily displays signal to the opponent or spectator a particular version of masculinity based on aggressiveness, competitiveness, power and assertiveness, derived from sociocultural processes that have constructed what a sporting body should “look like” and “act like”. In this case, body practices present maleness as a performance that is understood in terms of being diametrically opposite to femininity ( Butler, 1990 ; Segal, 1997 ). Within the context of sport, the body takes on a greater significance where embodied “deeds” are prioritized and established on principles such as competition, winning and overcoming opponents. The combination of a socially formulated construction of normative masculinity as superior to femininity and the practice of sport as a male social space creates the (false) need for more obvious outward performances by those who wish to participate. Consequently, displays of the body act as a primary means through which an expected sporting (masculine) identity can be established and maintained.

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of studies into masculinity and masculinities ( Hearn and Morgan, 1990 ; Connell, 1995 ; Whitehead, 2002 ), and Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity has become an established starting point for debate, particularly within the context of sport. Like many other forms of “dominant” theory, the concept has been subjected to many forms of criticism. However, Connell’s willingness to address criticisms of her earlier descriptions of hegemony as a response to developments in critical thinking, along with her original accommodation of a broader embodied approach has allowed her general theoretical arguments about hegemonic masculinity to weather the storm ( Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005 ). Indeed, within the context of gender and sport, Connell’s description of hegemonic masculinity is relevant, precisely because of the recognition of body-reflexive practices that contribute to the internalization by the individual of broader social discourses that ultimately affect participation.

My own interpretation of hegemonic masculinity is informed by Connell’s theory in terms of her recognition of the body but is also influenced by Butler’s (1993) descriptions of the “performative” aspects of the gendered body and Bourdieu’s (1990) concept of “Capital” (in particular, “sporting” and “cultural” capital) generated through performances of the body. Although I am aware of the conflicting tensions that emerge through the theoretical trajectories of these concepts ( Pringle, 2005 ), prioritizing the body allows for consideration of how these knowledge systems and relationships of power impact on the individual body. Subsequent investigations ( Wellard, 2002 , 2006 , 2009 ) convinced me that Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity, within the context of gender and sport, remained relevant particularly by reading these ideas through the body and body performances. Consequently, it is the lack of recognition of the embodied aspects of sport participation (and embodied experience) that is a telling gap within much of the sport literature and especially many subsequent critiques of hegemonic masculinity.

Recent claims made by Anderson (2009) about “inclusive masculinity” as a “new” theoretical insight to replace hegemonic masculinity fall short when they are subjected to the same type of scrutiny that Connell’s theories have been. For example, a failure by many critics to recognize the performative, embodied elements is neatly summarized by de Boise (2014) when he highlights the strengths of Connell’s original ideas.

Here is the crux of Connell’s (1995 : 77) argument; while gender is performative, hegemonic practices, in order to be legitimated, must correspond to institutional privilege and power, which have no basis in nature and are subject to change. Therefore, what is considered gender “identity” is not psychologically “fixed” or acquired, but dependent on arrangements of social power. In contrast, Anderson’s account wrongly seems to suggest that gender emanates from an internalized, psychological predisposition, rather than the performance as constituting gender. ( de Boise, 2014 : 7)

Although Anderson’s claims that there has been an increase in more inclusive forms of masculinity may have some substance within the context of broader, contemporary social discourses, it is less convincing when applied to sport. In my research into gendered bodily performances in sport, I initially employed the term “exclusive masculinity” ( Wellard, 2002 ) to describe a particular form of hegemonic masculinity that I found to be prevalent within sport. Subsequent further analysis ( Wellard, 2009 ) led me to suspect that this was slightly misleading in that performances of certain versions of masculinity do not necessarily “exclude” but rather compel specific performances within the sport setting, particularly during play. “Expected” sporting masculinity can therefore be seen as a form of embodied masculine performance that is considered appropriate or necessary within the specific location of taking part or playing sport and can be read alongside other “accepted” forms of sporting masculinity that occur off the playing field, but within the social space of sport. In this way, awareness of what is “expected” when entering the sports arena is necessary for an individual and consequent reflections by the individual about their ability to display what is expected can be assessed in terms of a range of broader social factors that affect them—such as gender, sexuality, age class and so on.

However, it is important to make it clear that expected sporting masculinity is not only based on the appearance of the body such as the possession of a muscular build or, indeed, the biological sex category of male. Within the context of sport, expected masculinity is expressed through bodily performances that adhere to traditional formulations of hegemonic masculinity, but embrace the values and ideals of sporting performance. Thus, outward displays of competitiveness, aggression, strength and athleticism are prioritized. Bodily capital is clearly understood in terms of how sport “should” be played and what it should look like as part of a social and historical process that Hargreaves (1986) describes. Consequently, the Muscular Christianity that Hargreaves describes as a significant element of contemporary sporting practice draws upon a particular version of an assertive, physical and heteronormative masculine body.

Within the context of sport, it is the performance of the body that is expected, not necessarily the social category such as gender or age. Although these play an important role, it is the bodily performance that provides the central focus. Being successful in sport requires specific knowledge about the body that, in turn, requires specific body performances. These replicate the performative aspects of gender within wider society, as described by Connell (2005) and Butler (1990) , but here the bodily performances are emphasized. For example, in an elite sport such as professional tennis, players in the men’s and women’s events whether physically large or small tend to display exaggerated versions of what could be described as aggressive masculinity through their on-court manner. They will talk about “being” aggressive in their play and their general on-court performances, and these are seen as essential elements for success. These bodily performances are replicated in other sporting contexts where certain behaviours become “expected”.

In the case of women players, they are performing “expected” sporting behaviours that are heavily influenced by historical, social formulations of traditional masculinities that are considered appropriate within the context of competitive sports, rather than in the way Halberstam (1998) talks about (broader, social discourses of) female masculinities. In the “on-court” sporting context, men and women adopt similar embodied strategies such as strutting about the court, pumping their clenched fists and acting aggressively towards their opponents. In this way, the body is prioritized over other social categories, and women, in order to “play”, need to accommodate the expected bodily performances. However, these expectations are at the same time regulated by broader social constructions of gender and essentialist understanding of difference through mechanisms such as separate spaces to play (for example, in tennis there is the ATP for men and the WTA for women).

In this way, it could be argued that a disabled person in a wheelchair could still perform expected sporting masculinity within the context of, for example, wheelchair basketball and, in doing so, reinforces the discriminatory gendered practices found within able-bodied sports. Indeed, here the notion of ability is equally important as it highlights the need for it to be read alongside gender to provide a fuller understanding of the way in which established codes of an able body and normative gender reinforce discourses of normalcy ( Peers, 2012 ). However, while the presence of those not necessarily considered as most “able” to perform expected sporting masculinity might suggest that traditional forms of masculinity are threatened or subverted when it is performed by women, gay men, lesbians or the disabled, the broader social discourses of gendered, sexual and disabled identities still operate. For instance, the tennis player Serena Williams may present outward signs of aggression and expected sporting behaviour on court, although, at the same time she presents accepted social signs of traditional femininity by wearing dresses and make-up. However, it is not sufficient to understand Serena’s on-court performances through gender alone; her body performances need to be read alongside a social context that has been informed by cultural and historical discourses that of race and women’s bodies ( McDonald, 2006 ). Consequently, whereas the context of professional, competitive sport may allow women to perform in ways that are expected within the context of sport, the broader social structures still operate to dictate how men’s and women’s bodies are constructed as different. This is particularly the case outside of professional sport, where displays of expected sporting masculinity become even more problematic for women ( Caudwell, 2006 ; Drury, 2011 ) as well as other disadvantaged groups.

“Real” masculinity and femininity

The notion, provided in the example above that Serena Williams can successfully perform in a hitherto male-dominated arena while still maintaining her “femininity”, highlights the contradictions of contemporary sport. Throughout the research that I have conducted with sportsmen ( Wellard, 2009 ), I have continually found that there is an assumption of a “real” or authentic version of masculinity. However, it has also been apparent that a definitive explanation could not be offered by the men, and in many cases there appeared to be a slippage in the use of the term. Indeed, the themes that recurred in their descriptions highlighted interplay between formulations of working-class sensibilities, heterosexuality and evidence of hard work and effort. The use of the body was central in the presentation of this version of masculinity. “Real” masculinity was constantly equated with presentations of the body that were considered “ordinary, ‘everyday’ or ‘run of the mill’ ” ( Wellard, 2009 ). Particularly within the context of sport, the men found it difficult to accept alternative versions of masculinity or “types” of body. For instance, among a group of male trainee PE teachers, the understanding of “normal” masculine behaviour extended to ways in which the body could (or should) move ( Wellard, 2007 ). In this particular case, these men found it difficult to accept the role of dance within their training. For them, the “ordinary” movements found in sport had been formulated through a combination of perceptions of class, expected masculine performances in sport and a narrow depiction of the sporting body. These were in opposition to the movements found in dance and their understanding of it. Dance was equated with non-sporting movements that were simultaneously associated with the feminine, considered non-working class and required a different approach to the body, both physically and emotionally.

However, even though there was a general sense of an authentic version of masculinity among nearly all the men I interviewed, their interpretations did not hold up to theoretical unpacking or scrutiny. The very fact that the men were positioning their identities within a “central” territory that was considered normal suggested that they felt little need to unduly question masculinity in general. The notion of “ordinariness” was not solely confined to heterosexual men. Many of the gay men I interviewed who played sport also considered themselves as “real” men who happened to be gay and their descriptions of “real” masculinity echoed those of the heterosexual men ( Wellard, 2009 ). Often, criticisms of “real” masculinity were considered to be voiced from those “outside” of what was considered to be a legitimate world view. As such, alternative arguments were considered less valid.

Belief that there is a real version of masculinity continues to reinforce gender binaries, and is particularly the case in sport where there is the expectation that only “real” men know or appreciate sport ( Connell, 2008 ). Those without “evidence” of such knowledge are considered “less than” real men. These simplistic formulations not only consolidate the belief that there is an authentic version of masculinity that creates unnecessary distinctions between groups of men but also continues to position women as occupying a separate gender binary.

It is because of the continued presence of a general perception of real masculinity as a basis for identity formation, that hegemonic masculinity ( Connell, 2005 ) as a theoretical concept remains relevant. It still has value in that it can be read as a way of explaining how particular sections of society remain subordinate and in that the claims made for authenticity do not destabilize the broader distributions of power, but rather offer useful justifications or appeals to less material forms of self-worth.

The centrality of the body: thinking about body-reflexive practices and pleasures

As I mentioned above, the findings from our report to the WHO indicated that the majority of girls enjoy taking part in sport and physical activity (or would like to, given the right circumstances). In order to understand when, how and why they found it enjoyable requires a greater understanding of individual experience so that any contributing factors that may have made it less enjoyable or not worth engaging in can be understood. Consequently, focussing initially on the body and embodied experiences provides an opportunity to consider more effectively the complex processes through which engagement and continued participation occur.

Although the discursive structures operating on the body revealed by Foucauldian and many post-structuralist accounts (for example, Butler, 1993 ; Markula and Pringle, 2006 ) have been extensively debated, there does seem room for more discussion about embodied experience ( Harre, 1998 ; Woodward, 2009 ; Wellard, 2013 ). In particular, the ways in which individuals create corporeal understandings of their own bodies and in turn develop understandings of their own physical identities as well as others. At the same time, it is acknowledged that there has been a growing interest in the meaning and experience of movement within the context of physical education, which could be described as a phenomenology of movement ( Smith, 2007 ). However, much of the focus here is to address the perceived lack of understanding about the qualities and characteristics of movement among physical education practitioners ( Brown and Payne, 2009 ).

Nevertheless, the concept of a “phenomenology of movement” is undoubtedly a significant influence in the way that experiences of fun and enjoyment can be understood in relation to sport participation. However, it is equally important to incorporate other theoretical positions that acknowledge the role of the body in shaping external social practices. As such, I have found the concept of body-reflexive practices ( Connell (2005) to be useful within this context as it enables the application of a social constructionist approach that incorporates the physical body within these social processes. Obviously, there are discourses that seek to explain social understandings of areas such as bodily health and sickness, but all too often they do not take into account the individual, corporeal experience of the body. Often there is a fear that this will involve a movement towards biological essentialism, but this need not be the case. I have described elsewhere ( Wellard, 2013 ) how my own enjoyment of sporting and physical activities has often been compromised by the requirements to manage and negotiate my body (particularly in relation to performances of hegemonic masculinity) in socially expected ways. I am not alone in this, as the potential bodily pleasures experienced through sporting activity have to be managed within social understandings of a range of discourses such as gender, sexuality, age and ability, which may ultimately prevent or diminish my ability or willingness to take part. It is here that Connell’s arguments have resonance as they form the basis of an understanding of the importance of the social and physical body and bodily practices. Connell attempts to incorporate the role of the biological (in this case, in the social construction of gender) and also applies a sociological reading of the social world where social actors are exposed to the restrictions created by social structures. She explains that,

With bodies both objects and agents of practice, and the practice itself forming the structures within which bodies are appropriated and defined, we face a pattern beyond the formulae of current social theory. This pattern might be termed body-reflexive practice. ( Connell, 2005 : 61)

Body-reflexive practices are, she argues, formed through a circuit of bodily experiences that link to bodily interaction and bodily experience via socially constructed bodily understandings that lead to new bodily interactions. As a result, Connell argues that social theory needs to account for the corporeality of the body. It is “through body-reflexive practices, bodies are addressed by social process and drawn into history, without ceasing to be bodies …. they do not turn into symbols, signs or positions in discourse” ( Connell, 2005 : 64).

Connell’s concept of body-reflexive practices helps us understand how social and cultural factors interact with individual experiences of the body. This in turn creates a need to recognize not only the social forms and practices that underpin the individual’s ability to take part in sport, or any other physical activity, but also the unique experiences or physical thrill of body-based expression.

Consequently, in order to adapt the concept so that it could be applied to a more specific embodied sporting and physical activity context, I developed the term body-reflexive pleasures ( Wellard, 2013 ). Within this context it is equally important to recognize the range of factors that contribute to the experience of pleasure (or not). Thus, if we apply the concept to an individual’s experience of a sport, we can see that consideration needs to be made of the social, physiological and psychological processes that occur at any level and with varied influence. Fun, enjoyment and pleasure are, therefore, central elements within a circuit of interconnected factors that determine the individual experience.

Recognizing the whole (embodied) package of sport

The example of fun and pleasure, above, is made specifically to highlight that there are multiple ways in which sport and physical activity can be experienced. The point here is not the case that men and women will experience sport and physical activity in an entirely different way, but rather that social constructions of gender contribute to the “way” that sport and physical activities are experienced. For children, young people and adults (particularly in the context of recreational sport), participation in sport is often expressed in terms of the potential for fun rather than as an emotional reaction that occurs during the activity. The notion that activity is considered in terms of “it could be” or “it was” fun suggests that a broader “process” is in operation and not a one-off moment of subjective gratification. A simplistic explanation that fun is trivial undermines the diverse ways that individuals anticipate, then experience and reflect on the fun elements within a sporting activity. Anticipation of fun may relate to many things such as potential achievement, learning something new, a social activity, an embodied experience or a thrill. In whatever way, they add to a personal memory bank, as an experience in itself and as an additional contribution to identity assessment. Understood in this way, even a hedonistic experience can be seen as significant, if considered in relation to its contribution to the memory bank of pleasurable moments and its impact on how the individual makes assessments about future participation.

However, the point about recognizing the broader dimensions of fun and enjoyment is that it is also necessary to acknowledge the wider dimensions of sport and physical activity experience, or the whole package of sport. Acknowledgment that participation in a sporting activity is influenced by a range of competing and conflicting factors allows for consideration that participation often relies on awareness of the “full contents” of the package and then navigation of the social, cultural, psychological and physiological expectations demanded for access to and continued participation. All of these contribute in varying ways that an individual is allowed entry (to a particular sporting activity) and, once in, is able to enjoy the experience.

Take, for instance, the example of tennis that I have been incorporating within this article. To get to the stage of experiencing the pleasurable aspects of actually playing the game, there is a process of learning, understanding and interpreting what tennis signifies within one’s immediate social, political and geographical situation. This process involves an understanding of the relationship of one’s embodied self to a socially constructed form of physical, adult play (sport). Consideration of one’s physical body, gender, age and race has to be applied to general perceptions of who is considered “able” to play. This is not to say that participation is excluded from the start in certain cases, but awareness of the “entry stakes” ultimately orientates the individual to make assumptions about whether they will be welcomed or not.

From a personal perspective, my introduction to tennis was through my parents, and during these early experiences I was able to “learn” more than not just the technical skills of how to play but also the social rules and etiquette expected within the game. Consequently, later attempts to join tennis clubs (in order to play a sport that I enjoyed) were uneventful in that I was able to demonstrate my knowledge of the whole package and “fit in”. Being male was obviously a significant part, but equally so were my physical and technical abilities, combined with my “knowledge” of how tennis should be played. My point is that “becoming” a fully fledged member of a sports club requires conformity of some sort, which means adapting to further “rules” and codes of play, much like a “hidden curriculum” ( Fernandez-Balboa, 1993 ) of sport that operates in addition to taken for granted prerequisites such as an ability to play the game. Seen in this light, it not only is the young person that is restricted by having to operate within adult discourses of what school- (or club-)based sport should look like, but also is an adult regulated in the way that they only have certain outlets in which to be able to experience sport pleasurably because of the way that many forms of club sport are internally “policed”, for instance, age, ability, gender, sexuality, class and race (see Ismond, 2003 ; Caudwell, 2006 ; Wellard, 2006 ; Tulle, 2008 ; Evans and Bairner, 2013 ).

Awareness of the hidden curriculum of many sports may also be a reason for the popularity among many adults for more individual pursuits such as running, cycling and swimming. Correspondingly, the social practices peculiar to specific sports may be an attraction for participation, in that much of the appeal of many club-based sports is the additional pre and postmatch social activities. Rituals, hazing, initiation rites, drinking games can all add to, if not play a central part in, a sense of belonging to a group ( Jonson, 2011) and, possibly, what an individual enjoys most in taking part. In many cases, it is the social activities that contribute more to continued participation than does actually playing the sport. Consequently, if we recognize that there are many other (covert and open) factors operating in any sporting activity, the suggestion is that in order to understand participation for an individual we need to be aware of the competing, influencing factors, which may or may not be solely related to gender.

Nevertheless, in most cases, within sporting contexts gender does play a significant part in how an individual ultimately experiences the activity. For example, recent research on the gendered perceptions of girls and boys who played Korfball, Footnote 1 ( Gubby, 2015 ) found that, although there were many gendered dynamics to be observed in a sport where boys and girls played together on the same teams, there were also other significant embodied factors that contributed to how the game was played and could be experienced. For instance, one integral aspect of Korfball was for all team members to be vocal during the games.

Although many team sports rely on a degree of communication in order to perform strategies and tactics, this is often no more than players shouting to signal that they are available to receive a ball, or to communicate the way forward for tactical play. Being vocal, however, has become an integral part of the game and is embedded deeply into the way it is played. “Calling” to inform teammates what their opponent might do next so that said teammate can mark and defend to the best of their abilities, is a necessary part of the game. ( Gubby, 2015 : 92)

In this particular case, the relevance of the vocal aspect read within the context of a sport that was developed to provide a gender neutral space highlights the importance of recognizing other factors that influence the experience of the game. In her research, Gubby (2015) observed how it was two girls who were identified by the other players as being the most vocal. However, where Korfball could be seen to offer some glimpses of gender equity, the sport was originally developed within the context of “difference” between boys and girls. The game itself provided a space for girls and boys to play together rather than, necessarily, being treated as equal. As Gubby suggests,

Whereas the positive aspects of playing together were considered favourably, it was equally difficult for the young people to leave behind their restricted formulations of how to “do gender” that had been developed in everyday social reality. At the same time, the rules of korfball could be considered equally restrictive in that they had been (historically) shaped from an initial premise of gender difference. ( Gubby, 2015 )

Conclusions

In summary, although it has not been the intention in this article to undermine the importance of gender within any debate about sport and physical activity, it is clear that positioning gender as an automatic starting point is not necessarily always the way to reveal the complexities of participation and how an activity is experienced . Recognition of the “whole package” of a particular sport allows assessment of the various influencing factors that shape the way that an individual is able to reflect upon an experience as enjoyable and, subsequently, whether participation or continued participation is either possible or worthwhile. Although the contexts in which children, young people and adults are able to access sport are different, particularly in terms of the prescriptive nature of school-based sport in comparison with the relatively greater opportunities available to adults, the ways in which assessments are made about participation invariably position fun and enjoyment as a major factor in continued or potential participation. Indeed, taking the body as a starting point might open up more inclusive ways of manoeuvring through the mine field that is gender and sport participation. The appeal of an embodied approach to the study of gender and sport is in its accommodation of a wider multidisciplinary lens. Particularly, by acknowledging the corporeal and “enfleshed” ( Woodward, 2015 ), an embodied approach offers a more flexible starting point to negotiate the challenges created by restrictive discourses of difference. Providing a more flexible starting point allows greater possibilities to accommodate the theoretical and methodological issues created by these discourses of difference that, ultimately, continue to limit the possibilities for many girls and boys to experience sport in a positive way.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Additional information

How to cite this article : Wellard I (2016) Gendered performances in sport: an embodied approach. Palgrave Communications . 2:16003 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2016.3.

Korfball was developed in 1902 in the Netherlands by a Dutch Primary School teacher as an alternative to single-sex team sports ( International Korfball Federation, 2006 ). It is played by teams of four (two men and two women) and comprises elements of basketball and netball.

Akinleye A (2015) Her life in movement: Reflections on embodiment as a methodology. In: Wellard I (ed). Researching Embodied Sport: Exploring Movement Cultures . Routledge: London.

Google Scholar

Anderson E (2009) Inclusive Masculinity: The Changing Nature of Masculinities . Routledge: Oxford.

Bailey R, Wellard I and Dismore H (eds) (2004) Girls’ participation in physical activities and sport: Benefits, patterns, influences and ways forward. In: Technical Report for the World Health Organisation . WHO: Geneva, Switzerland.

Bourdieu P (1990) The Logic of Practice . Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Brown T D and Payne G P (2009) Conceptualizing the phenomenology of movement in physical education: Implications for pedagogical inquiry and development. Quest ; 61 (4): 418–441.

Article Google Scholar

Butler J (1990) Gender Trouble . Routledge: New York.

Butler J (1993) Bodies that Matter . Routledge: NewYork.

Caudwell J (2006) Sport, Sexualities and Queer Theory: Challenges and Controversies . Routledge: London.

Christensen P and James A (2008) Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices . RoutledgeFalmer: London, pp 156–172.

Book Google Scholar

Connell R W (1995) Masculinities , 1st edn, Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Connell R W (2005) Masculinities , 2nd edn, Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Connell R W (2007) Southern Theory . Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Connell R W (2008) Masculinity construction and sports in boys’ education: A framework for thinking about the issue. Sport, Education and Society ; 13 (2): 131–145.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Connell R W and Messerschmidt J W (2005) Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society ; 19 (6): 829–859.

de Boise S (2014) I’m not homophobic, “i’ve got gay friends”: Evaluating the validity of inclusive masculinity. Men and Masculinities ; 1–22, published online 16 October 2014.

Drury S (2011) “It seems really inclusive in some ways, but … inclusive just for people who identify as lesbian”: Discourses of gender and sexuality in a lesbian-identified football club. Soccer and Society ; 12 (3): 421–442.

Evans J and Bairner A (2013) Physical education and social class. In: Stidder G and Hayes S (eds). Equity and Inclusion in Physical Education and Sport , 2nd edn, Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon.

Fernandez-Balboa J-M (1993) Socio-cultural characteristics of the hidden curriculum in physical education. Quest ; 45 (2): 230–254.

Foucault M (1979) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Clinic . Penguin Books: London.

Frank A (1991) For a sociology of the body: An analytical review In: Featherstone M, Hepworth M and Turner B (eds). The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory . Sage: London.

Gubby L (2015) Embodied practices in Korfball. In: Wellard I (ed). Researching Embodied Sport: Exploring Movement Cultures . Routledge: London.

Halberstam J (1998) Female Masculinities . Duke University Press: Durham, NC.

Hargreaves J A (1994) Sporting Females . Routledge: London.

Hargreaves J (1986) Sport, Power and Culture . Polity: London.

Harre R (1998) Man and woman. In: Welton D (ed). Body and Flesh: A Philosophical Reader . Blackwel: Malden, MA, pp 10–25.

Hearn J and Morgan D (1990) Men, Masculinities and Social Theory . Unwin Hyman: London.

Inckle K (2010) Telling tales? Using ethnographic fiction to speak embodied “truth”. Qualitative Research ; 10 (1): 27–47.

International Korfball Federation. (2006) Korfball in the Mixed Zone . KNKV: Zeist, The Netherlands.

Ismond P (2003) Black and Asian Athletes in British Sport and Society: A Sporting Chance? Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK.

Jenks C (2005) Childhood . Routledge: New York.

Johnson J (2011) Across the threshold: A comparative analysis of communitas and rites of passage in sport hazing and initiations. Canadian Journal of Sociology ; 36 (3): 199–226.

Markula P and Pringle R (2006) Foucault, Sport and Exercise . Routledge: London.

McDonald M G (2006) Beyond the pale: The whiteness of queer and sport studies scholarship. In: Caudwell J C (ed). Sport, Sexualities and Queer Theory . Routledge: London, pp 33–46.

Messner M A (1992) Power at Play: Sports and the Problem of Masculinity . Beacon Press: Boston, MA.

Peers D (2012) Patients, athletes, freaks: Paralympism and the reproduction of disability. Journal of Sport and Social Issues ; 36 (3): 295–316.

Article ADS Google Scholar

Phipps A (2014) The Politics of the Body: Gender in a Neoliberal and Neoconservative Age . Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Pringle R (2005) Masculinities, sport and power: A critical comparison of Gramscian and Foucauldian inspired theoretical tools. Journal of Sports and SocialIssues ; 29 (3): 256–278.

Pronger B (2002) Body Fascism: Salvation in the Technology of Fitness . University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada.

Runswick-Cole K A and Goodley D A (2011) Problematising policy: Conceptions of “child”, “disabled” and “parents” in social policy in England. International Journal of Inclusive Education ; 15 (1): 71–85.

Segal L (1997) Slow Motion; Changing Masculinities, Changing Men . Virago: London.

Shilling C (1993) The Body and Social Theory . Sage: London.

Smith J (2007) The first rush of movement: A phenomenological preface to movement education. Phenomenology and Practice ; 1 (1): 47–75.

Tulle E (2008) Ageing, the Body and Social Change: Running in Later Life . Palgrave Macmillan: London.

Wellard I (2002) Men, sport, body performance and the maintenance of “exclusive masculinity”. Leisure Studies ; 21 (3–4): 235–247.

Wellard I (2006) Able bodies and sport participation: Social constructions of physical ability for gendered and sexually identified bodies. Sport, Education and Society ; 11 (2): 105–119.

Wellard I (2007) Rethinking Gender and Youth Sport . Routledge: London.

Wellard I (2009) Sport, Masculinities and the Body . Routledge: New York.

Wellard I (2013) Sport, Fun and Enjoyment: An Embodied Approach . Routledge: London.

Whitehead S (2002) Men and Masculinities: Key Themes and New Directions . Polity: Cambridge, UK.

Woodward K (1997) Identity and Difference . Sage: London.

Woodward K (2009) Embodied Sporting Practices: Regulating and Regulatory Bodies . Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK.

Woodward K (2015) Bodies in the zone. In: Wellard I (ed). Researching Embodied Sport: Exploring Movement Cultures . Routledge: London.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Human and Life Sciences, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, Kent, UK

Ian Wellard

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wellard, I. Gendered performances in sport: an embodied approach. Palgrave Commun 2 , 16003 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.3

Download citation

Received : 01 November 2015

Accepted : 11 January 2016

Published : 01 March 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, re-thinking women's sport research: looking in the mirror and reflecting forward.

- 1 Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2 Pompea College of Business, University of New Haven, West Haven, CT, United States

- 3 Lang School of Business and Economics, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 4 School of Kinesiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 5 College of Education, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, United States

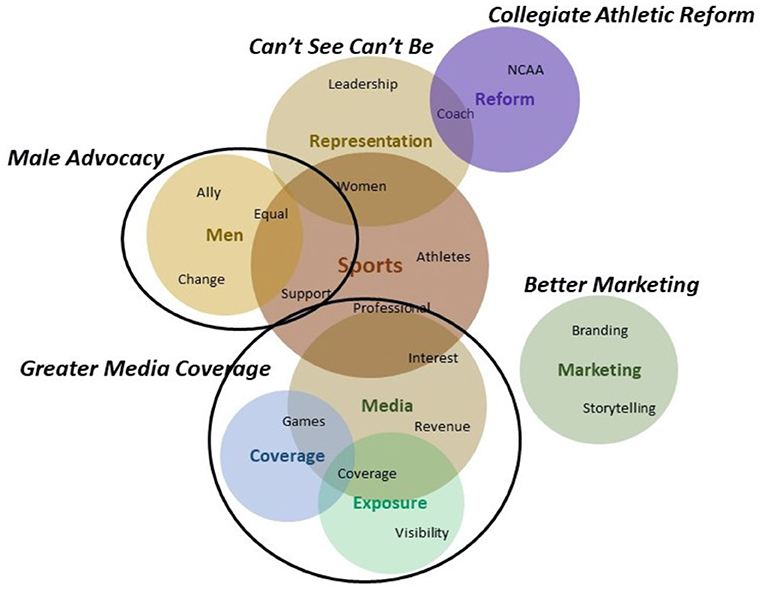

Despite decades of research and advocacy—women's professional sports continue to be considered second class to men's sports. The goal of this paper is to rethink how we state, present, and solve problems in women's sport. To affect true change, the wisdom of a broad stakeholder group was embraced such that varied perspectives could be considered. A three-question survey was developed to examine what key constituents believe is working in women's sports, what they believe the salient challenges are for women's sport, and how they would prioritize the next steps forward in the post-pandemic sport landscape. Results indicated siloed differences of opinion based upon the age and role of the stakeholder in the women's sport ecosystem. We discuss the implications and offer recommendations as to how we as scholars might recalibrate our approach to women's sport scholarship to maximize the impact of our research and affect change.

Introduction

While women's sport research has undoubtedly progressed, only a few token statistics have broken through into mainstream conversation and informed industry decision-making over the past decade. Arguably the most popular academic reference in women's sport refers to research that has tracked media coverage inequities. The oft-cited 4% statistic refers to the percentage of coverage afforded to women's sport in sports media. It is regularly used to provide context in industry conversations and simultaneously exists as the most viewed, downloaded, and cited statistic in the Communication and Sport academic journal ( Cooky et al., 2015 ). Why have so few other scholarly contributions been able to achieve this kind of reach? While we recognize that research alone will not create change ( Fink, 2015 ), as we reflect, reset our collective agendas and begin to build back and step forward in the post-pandemic sport landscape, rethinking our research contributions to more closely align with key stakeholders could help us to better serve both women athletes and the growth of women's professional sports.

Scholars have commonly shared and challenged the same linear storylines about women's sport for decades—comparing women's sports to men's sports, relating pre-Title IX to current day, highlighting the gendered participation gap and resource disparities, noting the decline and stagnation of women in sport leadership positions, documenting the dismal and marginalized media coverage, and detailing a perceived lack of fan interest (e.g., Hardin, 2005 ; Schultz, 2014 ; Burton, 2015 ; Bruce, 2016 ; LaVoi, 2016 ). Despite our best intentions to educate and inform around gender equity, in practice, we've witnessed little perceptible change. Amidst a time of rapid disruption and innovation, perhaps it is time to also reframe the ways in which we collectively study, think, and talk about women's sport.

Wedell-Wedellsborg (2020) suggested the process of reframing can be a helpful strategy to solve difficult, complex problems. His framework encourages problem solvers to look outside of traditional frames, re-think their goals, examine bright spots, and then look in the mirror to let go of past assumptions and narratives, which ensures outside perspectives are taken into account. The goal of this framework is to maintain momentum and move forward. As we consider our academic expertise, it's critical to remember that we tend to frame problems that match our preferred solutions ( Wedell-Wedellsborg, 2020 ). However, are there stakeholders whose influence and insights we might be missing? Are we overlooking systemic factors that might influence different stakeholder groups in ways we haven't conceived? What are we not paying attention to? How is functional fixedness—a type of cognitive bias that involves a tendency to see objects as only working in a particular way—affecting our research?

Grant (2021) noted recently the art of reconsidering has never been more critical. Accelerated change is evidenced in a number of fields by the global COVID-19 pandemic, causing us all to doubt previous practices and re-imagine new possibilities. While momentum for gender equity in sport was building prior to COVID-19 ( Leberman et al., 2020 ; Bowes et al., 2021 ), the forced pause necessitated by the pandemic inarguably served as a pivot point for women's sports, showcasing its great potential for growth. We now find women's sports in a moment of transition. The sports industry is actively re-thinking how women's sports are produced, measured, and distributed ( Sport Innovation Lab, 2021 ). As thought leaders in academia, we too must grapple with the idea that facts and the context may have changed over the past decade and recognize the potential value of reframing our own minds ( Grant, 2021 ).

Our mission with this research is to cultivate curiosity, challenge assumptions, question the status quo, and promote an innovative research culture that can help to move the entire field of women's sport forward by driving strategy and building theory. We want to pause and rethink how we state, present, and solve problems in women's sport so that we are better positioned to affect sustained and real change. In line with Wedell-Wedellsborg's problem-solving framework, the first step in this re-framing journey is to embrace the wisdom of crowds. The purpose of this research, therefore, was to actively engage a wide variety of stakeholders in the women's sport ecosystem (i.e., all those with an interest in women's sports) to better understand the state of the women's sport landscape from a variety of perspectives and determine whether or not differences exist between stakeholder groups.

Literature Review

The following review addresses the key elements within Wedell-Wedellsborg's problem-solving framework. We begin by prefacing how we as academic researchers might begin to look outside of our traditional frames and rethink our research goals. We then look to the “bright spots” in women's sport research, summarizing the types of research that are working well. This is followed by a critical “look in the mirror” where we consider potential blind spots in our research and examine academic bias in our field. We conclude with a preliminary reflection on the variety of stakeholders in the women's sport space and the diversity of problems each may be trying to solve as we look forward.

Looking Outside the Frame

What are we missing? Solving complex problems requires us all to get curious about what we do not know, let go of past ways, dated assumptions, and familiar narratives. We all need to admit that “we don't know what we don't know,” and trust that other women's sport stakeholders could bring value to the reframing process with new perspectives and insights. Nutt (2002) noted that one of the most powerful things one can do when solving problems is generate multiple opinions to inform the ideation process ( Nutt, 2002 ). Wedell-Wedellsborg (2020) built on this and promoted inviting outsiders to come up with alternative framings, suggesting that the strategy of zooming out to ask others what's missing can be a powerful way of bringing about a more people-oriented lens to a problem. This approach helps us to look beyond our traditional framing tendencies and/or see old problems in new ways. It also has the potential to be particularly effective as it relates to the industry-academic chasm in women's professional sport which has traditionally fractured around industry desire to monetize research findings on an efficient timeline and academic interests that value quality, rigor, and theoretical development for long-term sustainability. Wedell-Wedellsborg (2020) highlights Kaplan's Law of the Instrument, noting that while it's not necessarily a bad thing to have a default solution, if you've repeatedly failed to solve a problem with your preferred solution, there's a good chance you need to reframe the problem. Specific to the challenges of women's sport, we recognize that real change will require multiple perspectives—from industry and academia, across a range of stakeholders, ages, backgrounds and identities—coming together to challenge one another and move women's sport forward into the future.

Examine Bright Spots

What type of research piques industry interest or impacts practical change? As we move to “look outside” of our academic frame, Wedell-Wedellsborg encourages us to look for “bright spots” to help gain new perspectives (p. 84). Grant (2021) similarly suggests the creation of “a specific kind of accountability—one that leads people to think again about best practices” (p. 216). So, what in women's sport research is working well? As noted, the media representation work of Cooky et al. (2015) and the most recent iteration of the longitudinal study, Cooky et al. (2021) , have become leading industry references. What sets this work apart? The research offers “sticky stats” that can be easily distilled for industry amplification while also serving to effectively quantify the vast inequities in women's sport media. Sticky stats are typically publicly available (as opposed to being behind a paywall) and they can be easily visualized and shared, which means they can simplify the translation of academic work and increase reach and traction. What's more, sticky stats are often startling.

The sticky stat strategy is being used more frequently in both industry reports and media reporting around women's sports. For example, the commercial investment audits conducted by the Women's Sport and Fitness Foundation popularly revealed that women's sport sponsorship accounted for just 0.4% of total sports sponsorships between 2011 and 2013 ( WSFF, 2014 ). Ernst and Young's sticky stat that 94% of women in C-suite offices played sport has also been widely shared ( EY, 2015 ). Deloitte made headlines with their forecast that women's sports were on track to become a billion-dollar industry ( Lee et al., 2020 ). The longitudinal report cards that track the progress of women sport coaches and leaders (i.e., the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women's annual Women in College Coaching Report Card or The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport Diversity Reports) are also widely cited data points and have become well-regarded industry sources.

In the media, sticky stats have started to make for great headlines. Journalists seem to be drawn to flashy viewership numbers, social media engagement records and social activism. For example, several outlets reported on the fact that the WNBA's viewership was up 74% after just five games in the 2021 season ( Carp, 2021 ). It was also widely reported that NWSL teams received a league-high 12 million Twitter impressions during the 2021 Challenge Cup tournament ( Brennan, 2021 ), and Naomi Osaka's tweet focused on engaging conversation around mental health ahead of the French Open was not only lauded around the world, it was also noted for generating more than 41 million impressions across Twitter and Instagram ( Irelan, 2021 ).

The concept of data journalism or data-driven journalism has also become a popular means to elevate journalistic storytelling ( Boyle, 2017 ). In the case of women's sport, data are a wonderful tool to educate audiences. Letting the data tell the story is an effective way to push back against the deeply-engrained opinions and stereotypes that have plagued the women's sport space. This practice is being successfully employed in women's sports by journalists on untraditional platforms like Lindsay Gibbs' PowerPlays newsletter, The Black Sportswoman Newsletter , or the social media news source, Shot:Clocks Media . We could also look to the example of new media platforms like The Gist or Just Women's Sports , both of which recently received millions of dollars in seed funding for their roles in filling the void in the women's sport media marketplace. If one of our goals as advocates for women's sport is to broaden the reach of our work, infusing these journalistic styles into the reporting of our research through accessible media (e.g., opinion editorials, podcasts, infographics), or even collaborating with these noted outlets to help support their research needs could be effective ways for academics to re-think our knowledge translation plans and educate a broader population through public scholarship ( Yapa, 2006 ; Colbeck and Weaver, 2008 ).

Information does not simply manifest itself into public discourse. Colbeck and Weaver (2008) encouraged faculty to see, explore, and exploit the connections between public scholarship and other faculty responsibilities including research, teaching, and service, noting it is “an important way to leverage public scholarship engagement” (p. 28). Yapa (2006) advocated for intentionality in academic research, arguing “new knowledge is created in its application to the field” (p. 73). To this end, we examine what Wedell-Wedellsborg (2020) refers to as a “positive outlier.” In lieu of the traditional mode of publishing an academic paper and then promoting work in media outlets, Isard and Melton (2021) recently teased the results of their research on the media coverage of Black players in the WNBA in a Sports Business Journal OpEd. They discussed a topline finding—that Black WNBA players receive significantly less media coverage—and were immediately afforded a series of high-profile press opportunities after the piece was published. The research was praised by ESPN employees and Paige Bueckers, a top collegiate basketball player, referenced the research in her nationally televised acceptance speech upon winning an ESPY for college athlete of the year, further amplifying the research. In this example, the reconsideration of traditional academic processes allowed the research findings to be reframed for multiple audiences, vastly extending both its reach and impact.

It's easy to fall victim to negativity bias when working to solve problems ( Wedell-Wedellsborg, 2020 ). In studying the bright spots of women's sport research, we enjoy an opportunity to pay more attention to situations in which things went particularly well. Perhaps unconventional by academic standards, Isard and Melton's decision to re-think the traditional order of knowledge transfer in academia allowed the researchers to capitalize on a moment in women's sport and embrace an opportunity to educate the industry. Had they waited to publicly unveil their work until the typically slow academic publication process was complete, would the same opportunities have existed? Could this strategy be successfully replicated with future research? Perhaps paying attention to the behaviors and circumstances that surround bright spots, could lead us to rethink the ways in which we communicate our research.

Look in the Mirror

What does academia bring to the table? What is our role in creating the problem? Wedell-Wedellsborg (2020) notes that when considering problems, we often overlook our own role in the situation. Collectively, both scholars who specifically research women's sport and those involved more generally in the sport management academy, offer a nuanced understanding of the sport landscape and provide a vast methodological toolkit that allows us to advance understanding and create new knowledge. If we are to look in the mirror, however, it's incumbent upon us to recognize the bias toward men's sports that exists in both the current body of sport-related academic literature and sport management curricula.