Trending Articles

- A Direct Link Implicating Loss of SLC26A6 to Gut Microbial Dysbiosis, Compromised Barrier Integrity and Inflammation. Anbazhagan AN, et al. Gastroenterology. 2024. PMID: 38735402

- Conflict of Interest Disclosures. [No authors listed] Global Spine J. 2024. PMID: 38726630 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of early vs. late enrollees of the STRONG-HF trial. Arrigo M, et al. Am Heart J. 2024. PMID: 38740532

- Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Abramson J, et al. Nature. 2024. PMID: 38718835

- Association between pretreatment emotional distress and immune checkpoint inhibitor response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Zeng Y, et al. Nat Med. 2024. PMID: 38740994

Latest Literature

- Clin Microbiol Rev (1)

- J Am Coll Cardiol (16)

- J Biol Chem (1)

- J Neurosci (4)

- J Virol (2)

- Nat Commun (37)

- Nature (37)

- Nucleic Acids Res (1)

- Oncogene (1)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Breaking boundaries. Empowering researchers. Opening Science.

PLOS is a nonprofit, Open Access publisher empowering researchers to accelerate progress in science and medicine by leading a transformation in research communication.

Every country. Every career stage. Every area of science. Hundreds of thousands of researchers choose PLOS to share and discuss their work. Together, we collaborate to make science, and the process of publishing science, fair, equitable, and accessible for the whole community.

FEATURED COMMUNITIES

- Molecular Biology

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Cancer Treatment and Research

RECENT ANNOUNCEMENTS

Written by Lindsay Morton Over 4 years: 74k+ eligible articles. Nearly 85k signed reviews. More than 30k published peer review history…

The latest quarterly update to the Open Science Indicators (OSIs) dataset was released in December, marking the one year anniversary of OSIs…

PLOS JOURNALS

PLOS publishes a suite of influential Open Access journals across all areas of science and medicine. Rigorously reported, peer reviewed and immediately available without restrictions, promoting the widest readership and impact possible. We encourage you to consider the scope of each journal before submission, as journals are editorially independent and specialized in their publication criteria and breadth of content.

PLOS Biology PLOS Climate PLOS Computational Biology PLOS Digital Health PLOS Genetics PLOS Global Public Health PLOS Medicine PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases PLOS ONE PLOS Pathogens PLOS Sustainability and Transformation PLOS Water

Now open for submissions:

PLOS Complex Systems PLOS Mental Health

ADVANCING OPEN SCIENCE

Open opportunities for your community to see, cite, share, and build on your research. PLOS gives you more control over how and when your work becomes available.

Ready, set, share your preprint. Authors of most PLOS journals can now opt-in at submission to have PLOS post their manuscript as a preprint to bioRxiv or medRxiv.

All PLOS journals offer authors the opportunity to increase the transparency of the evaluation process by publishing their peer review history.

We have everything you need to amplify your reviews, increase the visibility of your work through PLOS, and join the movement to advance Open Science.

FEATURED RESOURCES

Ready to submit your manuscript to PLOS? Find everything you need to choose the journal that’s right for you as well as information about publication fees, metrics, and other FAQs here.

We have everything you need to write your first review, increase the visibility of your work through PLOS, and join the movement to advance Open Science.

Transform your research with PLOS. Submit your manuscript

Psychological Science

Prospective submitters of manuscripts are encouraged to read Editor-in-Chief Simine Vazire’s editorial , as well as the editorial by Tom Hardwicke, Senior Editor for Statistics, Transparency, & Rigor, and Simine Vazire.

Psychological Science , the flagship journal of the Association for Psychological Science, is the leading peer-reviewed journal publishing empirical research spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. The journal publishes high quality research articles of general interest and on important topics spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. Replication studies are welcome and evaluated on the same criteria as novel studies. Articles are published in OnlineFirst before they are assigned to an issue. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

Quick Facts

Read the February 2022 editorial by former Editor-in-Chief Patricia Bauer, “Psychological Science Stepping Up a Level.”

Read the January 2020 editorial by former Editor Patricia Bauer on her vision for the future of Psychological Science .

Read the December 2015 editorial on replication by former Editor Steve Lindsay, as well as his April 2017 editorial on sharing data and materials during the review process.

Watch Geoff Cumming’s video workshop on the new statistics.

Current Issue

Online First Articles

List of Issues

Editorial Board

Submission Guidelines

Editorial Policies

Featured research from psychological science, teens who view their homes as more chaotic than their siblings have poorer mental health in adulthood.

Many parents ponder why one of their children seems more emotionally troubled than the others. A new study in the United Kingdom reveals a possible basis for those differences.

Rewatching Videos of People Shifts How We Judge Them, Study Indicates

Rewatching recorded behavior, whether on a Tik-Tok video or police body-camera footage, makes even the most spontaneous actions seem more rehearsed or deliberate, new research shows.

Loneliness Bookends Adulthood, Study Shows

Loneliness in adulthood follows a U-shaped pattern: It’s higher in younger and older adulthood, and lowest during middle adulthood, according to new research that examined nine longitudinal studies from around the world.

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

What is peer review.

Peer review is ‘a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already know.’ You can learn more in this explainer from the Social Science Space.

Peer review brings academic research to publication in the following ways:

- Evaluation – Peer review is an effective form of research evaluation to help select the highest quality articles for publication.

- Integrity – Peer review ensures the integrity of the publishing process and the scholarly record. Reviewers are independent of journal publications and the research being conducted.

- Quality – The filtering process and revision advice improve the quality of the final research article as well as offering the author new insights into their research methods and the results that they have compiled. Peer review gives authors access to the opinions of experts in the field who can provide support and insight.

Types of peer review

- Single-anonymized – the name of the reviewer is hidden from the author.

- Double-anonymized – names are hidden from both reviewers and the authors.

- Triple-anonymized – names are hidden from authors, reviewers, and the editor.

- Open peer review comes in many forms . At Sage we offer a form of open peer review on some journals via our Transparent Peer Review program , whereby the reviews are published alongside the article. The names of the reviewers may also be published, depending on the reviewers’ preference.

- Post publication peer review can offer useful interaction and a discussion forum for the research community. This form of peer review is not usual or appropriate in all fields.

To learn more about the different types of peer review, see page 14 of ‘ The Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review ’ from Sense about Science.

Please double check the manuscript submission guidelines of the journal you are reviewing in order to ensure that you understand the method of peer review being used.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- Transparent Peer Review

- How to Review Articles

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage editorial policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 12 May 2024

Association between problematic social networking use and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Mingxuan Du 1 ,

- Chengjia Zhao 2 ,

- Haiyan Hu 1 ,

- Ningning Ding 1 ,

- Jiankang He 1 ,

- Wenwen Tian 1 ,

- Wenqian Zhao 1 ,

- Xiujian Lin 1 ,

- Gaoyang Liu 1 ,

- Wendan Chen 1 ,

- ShuangLiu Wang 1 ,

- Pengcheng Wang 3 ,

- Dongwu Xu 1 ,

- Xinhua Shen 4 &

- Guohua Zhang 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 263 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

186 Accesses

Metrics details

A growing number of studies have reported that problematic social networking use (PSNU) is strongly associated with anxiety symptoms. However, due to the presence of multiple anxiety subtypes, existing research findings on the extent of this association vary widely, leading to a lack of consensus. The current meta-analysis aimed to summarize studies exploring the relationship between PSNU levels and anxiety symptoms, including generalized anxiety, social anxiety, attachment anxiety, and fear of missing out. 209 studies with a total of 172 articles were included in the meta-analysis, involving 252,337 participants from 28 countries. The results showed a moderately positive association between PSNU and generalized anxiety (GA), social anxiety (SA), attachment anxiety (AA), and fear of missing out (FoMO) respectively (GA: r = 0.388, 95% CI [0.362, 0.413]; SA: r = 0.437, 95% CI [0.395, 0.478]; AA: r = 0.345, 95% CI [0.286, 0.402]; FoMO: r = 0.496, 95% CI [0.461, 0.529]), and there were different regulatory factors between PSNU and different anxiety subtypes. This study provides the first comprehensive estimate of the association of PSNU with multiple anxiety subtypes, which vary by time of measurement, region, gender, and measurement tool.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Social network refers to online platforms that allow users to create, share, and exchange information, encompassing text, images, audio, and video [ 1 ]. The use of social network, a term encompassing various activities on these platforms, has been measured from angles such as frequency, duration, intensity, and addictive behavior, all indicative of the extent of social networking usage [ 2 ]. As of April 2023, there are 4.8 billion social network users globally, representing 59.9% of the world’s population [ 3 ]. The usage of social network is considered a normal behavior and a part of everyday life [ 4 , 5 ]. Although social network offers convenience in daily life, excessive use can lead to PSNU [ 6 , 7 ], posing potential threats to mental health, particularly anxiety symptoms (Rasmussen et al., 2020). Empirical research has shown that anxiety symptoms, including generalized anxiety (GA), social anxiety (SA), attachment anxiety (AA), and fear of missing out (FoMO), are closely related to PSNU [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. While some empirical studies have explored the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms, their conclusions are not consistent. Some studies have found a significant positive correlation [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], while others have found no significant correlation [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Furthermore, the degree of correlation varies widely in existing research, with reported r-values ranging from 0.12 to 0.80 [ 20 , 21 ]. Therefore, a systematic meta-analysis is necessary to clarify the impact of PSNU on individual anxiety symptoms.

Previous research lacks a unified concept of PSNU, primarily due to differing theoretical interpretations by various authors, and the use of varied standards and diagnostic tools. Currently, this phenomenon is referred to by several terms, including compulsive social networking use, problematic social networking use, excessive social networking use, social networking dependency, and social networking addiction [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. These conceptual differences hinder the development of a cohesive and systematic research framework, as it remains unclear whether these definitions and tools capture the same underlying construct [ 27 ]. To address this lack of uniformity, this paper will use the term “problematic use” to encompass all the aforementioned nomenclatures (i.e., compulsive, excessive, dependent, and addictive use).

Regarding the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms, two main perspectives exist: the first suggests a positive correlation, while the second proposes a U-shaped relationship. The former perspective, advocating a positive correlation, aligns with the social cognitive theory of mass communication. It posits that PSNU can reinforce certain cognitions, emotions, attitudes, and behaviors [ 28 , 29 ], potentially elevating individuals’ anxiety levels [ 30 ]. Additionally, the cognitive-behavioral model of pathological use, a primary framework for explaining factors related to internet-based addictions, indicates that psychiatric symptoms like depression or anxiety may precede internet addiction, implying that individuals experiencing anxiety may turn to social networking platforms as a coping mechanism [ 31 ]. Empirical research also suggests that highly anxious individuals prefer computer-mediated communication due to the control and social liberation it offers and are more likely to have maladaptive emotional regulation, potentially leading to problematic social network service use [ 32 ]. Turning to the alternate perspective, it proposes a U-shaped relationship as per the digital Goldilocks hypothesis. In this view, moderate social networking usage is considered beneficial for psychosocial adaptation, providing individuals with opportunities for social connection and support. Conversely, both excessive use and abstinence can negatively impact psychosocial adaptation [ 33 ]. In summary, both perspectives offer plausible explanations.

Incorporating findings from previous meta-analyses, we identified seven systematic reviews and two meta-analyses that investigated the association between PSNU and anxiety. The results of these meta-analyses indicated a significant positive correlation between PSNU and anxiety (ranging from 0.33 to 0.38). However, it is evident that these previous meta-analyses had certain limitations. Firstly, they focused only on specific subtypes of anxiety; secondly, they were limited to adolescents and emerging adults in terms of age. In summary, this systematic review aims to ascertain which theoretical perspective more effectively explains the relationship between PSNU and anxiety, addressing the gaps in previous meta-analyses. Additionally, the association between PSNU and anxiety could be moderated by various factors. Drawing from a broad research perspective, any individual study is influenced by researcher-specific designs and associated sample estimates. These may lead to bias compared to the broader population. Considering the selection criteria for moderating variables in empirical studies and meta-analyses [ 34 , 35 ], the heterogeneity of findings on problematic social network usage and anxiety symptoms could be driven by divergence in sample characteristics (e.g., gender, age, region) and research characteristics (measurement instrument of study variables). Since the 2019 coronavirus pandemic, heightened public anxiety may be attributed to the fear of the virus or heightened real life stress. The increased use of electronic devices, particularly smartphones during the pandemic, also instigates the prevalence of problematic social networking. Thus, our analysis focuses on three moderators: sample characteristics (participants’ gender, age, region), measurement tools (for PSNU and anxiety symptoms) and the time of measurement (before COVID-19 vs. during COVID-19).

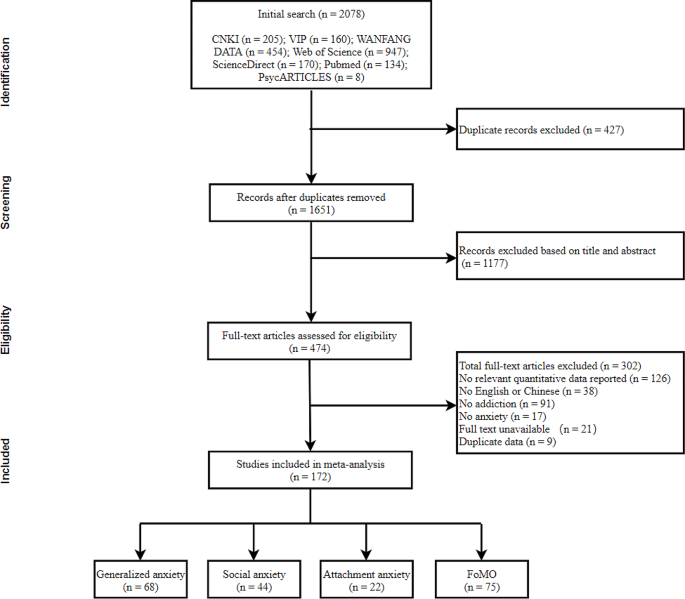

The present study was conducted in accordance with the 2020 statement on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 36 ]. To facilitate transparency and to avoid unnecessary duplication of research, this study was registered on PROSPERO, and the number is CRD42022350902.

Literature search

Studies on the relationship between the PSNU and anxiety symptoms from 2000 to 2023 were retrieved from seven databases. These databases included China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data, Chongqing VIP Information Co. Ltd. (VIP), Web of Science, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and PsycARTICLES. The search strings consisted of (a) anxiety symptoms, (b) social network, and (c) Problematic use. As shown in Table 1 , the keywords for anxiety are as follows: anxiety, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, attachment anxiety, fear of missing out, and FoMO. The keywords for social network are as follows: social network, social media, social networking site, Instagram, and Facebook. The keywords for addiction are as follows: addiction, dependence, problem/problematic use, excessive use. The search deadline was March 19, 2023. A total of 2078 studies were initially retrieved and all were identified ultimately.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Retrieved studies were eligible for the present meta-analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) the study provided Pearson correlation coefficients used to measure the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms; (b) the study reported the sample size and the measurement instruments for the variables; (c) the study was written in English and Chinese; (d) the study provided sufficient statistics to calculate the effect sizes; (e) effect sizes were extracted from independent samples. If multiple independent samples were investigated in the same study, they were coded separately; if the study was a longitudinal study, they were coded by the first measurement. In addition, studies were excluded if they: (a) examined non-problematic social network use; (b) had an abnormal sample population; (c) the results of the same sample were included in another study and (d) were case reports or review articles. Two evaluators with master’s degrees independently assessed the eligibility of the articles. A third evaluator with a PhD examined the results and resolved dissenting views.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two evaluators independently coded the selected articles according to the following characteristics: literature information, time of measurement (before the COVID-19 vs. during the COVID-19), sample source (developed country vs. developing country), sample size, proportion of males, mean age, type of anxiety, and measurement instruments for PSNU and anxiety symptoms. The following principles needed to be adhered to in the coding process: (a) effect sizes were extracted from independent samples. If multiple independent samples were investigated in the same study, they were coded separately; if the study was a longitudinal study, it was coded by the first measurement; (b) if multiple studies used the same data, the one with the most complete information was selected; (c) If studies reported t or F values rather than r , the following formula \( r=\sqrt{\frac{{t}^{2}}{{t}^{2}+df}}\) ; \( r=\sqrt{\frac{F}{F+d{f}_{e}}}\) was used to convert them into r values [ 37 , 38 ]. Additionally, if some studies only reported the correlation matrix between each dimension of PSNU and anxiety symptoms, the following formula \( {r}_{xy}=\frac{\sum {r}_{xi}{r}_{yj}}{\sqrt{n+n(n-1){r}_{xixj}}\sqrt{m+m(m-1){r}_{yiyj}}}\) was used to synthesize the r values [ 39 ], where n or m is the number of dimensions of variable x or variable y, respectively, and \( {r}_{xixj} \) or \( {r}_{yiyj}\) represents the mean of the correlation coefficients between the dimensions of variable x or variable y, respectively.

Literature quality was determined according to the meta-analysis quality evaluation scale developed [ 40 ]. The quality of the post-screening studies was assessed by five dimensions: sampling method, efficiency of sample collection, level of publication, and reliability of PSNU and anxiety symptom measurement instruments. The total score of the scale ranged from 0 to 10; higher scores indicated better quality of the literature.

Data analysis

All data were performed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis 3.3 (CMA 3.3). Pearson’s product-moment coefficient r was selected as the effect size index in this meta-analysis. Firstly, \( {\text{F}\text{i}\text{s}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}}^{{\prime }}\text{s} Z=\frac{1}{2}\times \text{ln}\left(\frac{1+r}{1-r}\right)\) was used to convert the correlation coefficient to Fisher Z . Then the formula \( SE=\sqrt{\frac{1}{n-3}}\) was used to calculate the standard error ( SE ). Finally, the summary of r was obtained from the formula \( r=\frac{{e}^{2z}-1}{{e}^{2z}+1}\) for a comprehensive measure of the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms [ 37 , 41 ].

Although the effect sizes estimated by the included studies may be similar, considering the actual differences between studies (e.g., region and gender), the random effects model was a better choice for data analysis for the current meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of the included study effect sizes was measured for significance by Cochran’s Q test and estimated quantitatively by the I 2 statistic [ 42 ]. If the results indicate there is a significant heterogeneity (the Q test: p -value < 0.05, I 2 > 75) and the results of different studies are significantly different from the overall effect size. Conversely, it indicates there are no differences between the studies and the overall effect size. And significant heterogeneity tends to indicate the possible presence of potential moderating variables. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis were used to examine the moderating effect of categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Funnel plots, fail-safe number (Nfs) and Egger linear regression were utilized to evaluate the publication bias [ 43 , 44 , 45 ]. The likelihood of publication bias was considered low if the intercept obtained from Egger linear regression was not significant. A larger Nfs indicated a lower risk of publication bias, and if Nfs < 5k + 10 (k representing the original number of studies), publication bias should be a concern [ 46 ]. When Egger’s linear regression was significant, the Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill was performed to correct the effect size. If there was no significant change in the effect size, it was assumed that there was no serious publication bias [ 47 ].

A significance level of P < 0.05 was deemed applicable in this study.

Sample characteristics

The PRISMA search process is depicted in Fig. 1 . The database search yielded 2078 records. After removing duplicate records and screening the title and abstract, the full text was subject to further evaluation. Ultimately, 172 records fit the inclusion criteria, including 209 independent effect sizes. The present meta-analysis included 68 studies on generalized anxiety, 44 on social anxiety, 22 on attachment anxiety, and 75 on fear of missing out. The characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 2 . The majority of the sample group were adults. Quality scores for selected studies ranged from 0 to 10, with only 34 effect sizes below the theoretical mean, indicating high quality for the included studies. The literature included utilized BSMAS as the primary tool to measure PSNU, DASS-21-A to measure GA, IAS to measure SA, ECR to measure AA, and FoMOS to measure FoMO.

Flow chart of the search and selection strategy

Overall analysis, homogeneity tests and publication bias

As shown in Table 3 , there was significant heterogeneity between PSNU and all four anxiety symptoms (GA: Q = 1623.090, I 2 = 95.872%; SA: Q = 1396.828, I 2 = 96.922%; AA: Q = 264.899, I 2 = 92.072%; FoMO: Q = 1847.110, I 2 = 95.994%), so a random effects model was chosen. The results of the random effects model indicate a moderate positive correlation between PSNU and anxiety symptoms (GA: r = 0.350, 95% CI [0.323, 0.378]; SA: r = 0.390, 95% CI [0.347, 0.431]; AA: r = 0.345, 95% CI [0.286, 0.402]; FoMO: r = 0.496, 95% CI [0.461, 0.529]).

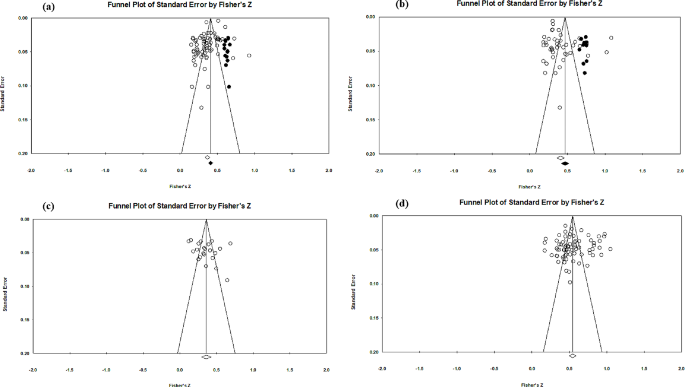

Figure 2 shows the funnel plot of the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms. No significant symmetry was seen in the funnel plot of the relationship between PSNU and GA and between PSNU and SA. And the Egger’s regression results also indicated that there might be publication bias ( t = 3.775, p < 0.001; t = 2.309, p < 0.05). Therefore, it was necessary to use fail-safe number (Nfs) and the trim and fill method for further examination and correction. The Nfs for PSNU and GA as well as PSNU and SA are 4591 and 7568, respectively. Both Nfs were much larger than the standard 5 k + 10. After performing the trim and fill method, 14 effect sizes were added to the right side of the funnel plat (Fig. 2 .a), the correlation coefficient between PSNU and GA changed to ( r = 0.388, 95% CI [0.362, 0.413]); 10 effect sizes were added to the right side of the funnel plat (Fig. 2 .b), the correlation coefficient between PSNU and SA changed to ( r = 0.437, 95% CI [0.395, 0.478]). The correlation coefficients did not change significantly, indicating that there was no significant publication bias associated with the relationship between PSNU and these two anxiety symptoms (GA and SA).

Funnel plot of the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms. Note: Black dots indicated additional studies after using trim and fill method; ( a ) = Funnel plot of the PSNU and GA; ( b ) = Funnel plot of the PSNU and SA; ( c ) = Funnel plot of the PSNU and AA; ( d ) = Funnel plot of the PSNU and FoMO

Sensitivity analyses

Initially, the findings obtained through the one-study-removed approach indicated that the heterogeneities in the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms were not attributed to any individual study. Nevertheless, it is important to note that sensitivity analysis should be performed based on literature quality [ 223 ] since low-quality literature could potentially impact result stability. In the relationship between PSNU and GA, the 10 effect sizes below the theoretical mean scores were excluded from analysis, and the sensitivity analysis results were recalculated ( r = 0.402, 95% CI [0.375, 0.428]); In the relationship between PSNU and SA, the 8 effect sizes below the theoretical mean scores were excluded from analysis, and the sensitivity analysis results were recalculated ( r = 0.431, 95% CI [0.387, 0.472]); In the relationship between PSNU and AA, the 5 effect sizes below the theoretical mean scores were excluded from analysis, and the sensitivity analysis results were recalculated ( r = 0.367, 95% CI [0.298, 0.433]); In the relationship between PSNU and FoMO, the 11 effect sizes below the theoretical mean scores were excluded from analysis, and the sensitivity analysis results were recalculated ( r = 0.508, 95% CI [0.470, 0.544]). The revised estimates indicate that meta-analysis results were stable.

Moderator analysis

The impact of moderator variables on the relation between psnu and ga.

The results of subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Table 4 , the time of measurement significantly moderated the correlation between PSNU and GA ( Q between = 19.268, df = 2, p < 0.001). The relation between the two variables was significantly higher during the COVID-19 ( r = 0.392, 95% CI [0.357, 0.425]) than before the COVID-19 ( r = 0.270, 95% CI [0.227, 0.313]) or measurement time uncertain ( r = 0.352, 95% CI [0.285, 0.415]).

The moderating effect of the PSNU measurement was significant ( Q between = 6.852, df = 1, p = 0.009). The relation was significantly higher when PSNU was measured with the BSMAS ( r = 0.373, 95% CI [0.341, 0.404]) compared to others ( r = 0.301, 95% CI [0.256, 0.344]).

The moderating effect of the GA measurement was significant ( Q between = 60.061, df = 5, p < 0.001). Specifically, when GA measured by the GAD ( r = 0.398, 95% CI [0.356, 0.438]) and the DASS-21-A ( r = 0.433, 95% CI [0.389, 0.475]), a moderate positive correlation was observed. However, the correlation was less significant when measured using the STAI ( r = 0.232, 95% CI [0.187, 0.276]).

For the relation between PSNU and GA, the moderating effect of region, gender and age were not significant.

The impact of moderator variables on the relation between PSNU and SA

The effects of the moderating variables in the relation between PSNU and SA were shown in Table 5 . The results revealed a gender-moderated variances between the two variables (b = 0.601, 95% CI [ 0.041, 1.161], Q model (1, k = 41) = 4.705, p = 0.036).

For the relation between PSNU and SA, the moderating effects of time of measurement, region, measurement of PSNU and SA, and age were not significant.

The impact of moderator variables on the relation between PSNU and AA

The effects of the moderating variables in the relation between PSNU and AA were shown in Table 6 , region significantly moderated the correlation between PSNU and AA ( Q between = 6.410, df = 2, p = 0.041). The correlation between the two variables was significantly higher in developing country ( r = 0.378, 95% CI [0.304, 0.448]) than in developed country ( r = 0.242, 95% CI [0.162, 0.319]).

The moderating effect of the PSNU measurement was significant ( Q between = 6.852, df = 1, p = 0.009). Specifically, when AA was measured by the GPIUS-2 ( r = 0.484, 95% CI [0.200, 0.692]) and the PMSMUAQ ( r = 0.443, 95% CI [0.381, 0.501]), a moderate positive correlation was observed. However, the correlation was less significant when measured using the BSMAS ( r = 0.248, 95% CI [0.161, 0.331]) and others ( r = 0.313, 95% CI [0.250, 0.372]).

The moderating effect of the AA measurement was significant ( Q between = 17.283, df = 2, p < 0.001). The correlation was significantly higher when measured using the ECR ( r = 0.386, 95% CI [0.338, 0.432]) compared to the RQ ( r = 0.200, 95% CI [0.123, 0.275]).

For the relation between PSNU and AA, the moderating effects of time of measurement, region, gender, and age were not significant.

The impact of moderator variables on the relation between PSNU and FoMO

The effects of the moderating variables in the relation between PSNU and FoMO were shown in Table 7 , the moderating effect of the PSNU measurement was significant ( Q between = 8.170, df = 2, p = 0.017). Among the sub-dimensions, the others was excluded because there was only one sample. Specifically, when measured using the FoMOS-MSME ( r = 0.630, 95% CI [0.513, 0.725]), a moderate positive correlation was observed. However, the correlation was less significant when measured using the FoMOS ( r = 0.472, 95% CI [0.432, 0.509]) and the T-S FoMOS ( r = 0.557, 95% CI [0.463, 0.639]).

For the relationship between PSNU and FoMO, the moderating effects of time of measurement, region, measurement of PSNU, gender and age were not significant.

Through systematic review and meta-analysis, this study established a positive correlation between PSNU and anxiety symptoms (i.e., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, attachment anxiety, and fear of missing out), confirming a linear relationship and partially supporting the Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication [ 28 ] and the Cognitive Behavioral Model of Pathological Use [ 31 ]. Specifically, a significant positive correlation between PSNU and GA was observed, implying that GA sufferers might resort to social network for validation or as an escape from reality, potentially alleviating their anxiety. Similarly, the meta-analysis demonstrated a strong positive correlation between PSNU and SA, suggesting a preference for computer-mediated communication among those with high social anxiety due to perceived control and liberation offered by social network. This preference is often accompanied by maladaptive emotional regulation, predisposing them to problematic use. In AA, a robust positive correlation was found with PSNU, indicating a higher propensity for such use among individuals with attachment anxiety. Notably, the study identified the strongest correlation in the context of FoMO. FoMO’s significant association with PSNU is multifaceted, stemming from the real-time nature of social networks that engenders a continuous concern about missing crucial updates or events. This drives frequent engagement with social network, thereby establishing a direct link to problematic usage patterns. Additionally, social network’s feedback loops amplify this effect, intensifying FoMO. The culture of social comparison on these platforms further exacerbates FoMO, as users frequently compare their lives with others’ selectively curated portrayals, enhancing both their social networking usage frequency and the pursuit for social validation. Furthermore, the integral role of social network in modern life broadens FoMO’s scope, encompassing anxieties about staying informed and connected.

The notable correlation between FoMO and PSNU can be comprehensively understood through various perspectives. FoMO is inherently linked to the real-time nature of social networks, which cultivates an ongoing concern about missing significant updates or events in one’s social circle [ 221 ]. This anxiety prompts frequent engagement with social network, leading to patterns of problematic use. Moreover, the feedback loops in social network algorithms, designed to enhance user engagement, further intensify this fear [ 224 ]. Additionally, social comparison, a common phenomenon on these platforms, exacerbates FoMO as users continuously compare their lives with the idealized representations of others, amplifying feelings of missing out on key social experiences [ 225 ]. This behavior not only increases social networking usage but also is closely linked to the quest for social validation and identity construction on these platforms. The extensive role of social network in modern life further amplifies FoMO, as these platforms are crucial for information exchange and maintaining social ties. FoMO thus encompasses more than social concerns, extending to anxieties about staying informed with trends and dynamics within social networks [ 226 ]. The multifaceted nature of FoMO in relation to social network underscores its pronounced correlation with problematic social networking usage. In essence, the combination of social network’s intrinsic characteristics, psychological drivers of user behavior, the culture of social comparison, and the pervasiveness of social network in everyday life collectively make FoMO the most pronouncedly correlated anxiety type with PSNU.

Additionally, we conducted subgroup analyses on the timing of measurement (before COVID-19 vs. during COVID-19), measurement tools (for PSNU and anxiety symptoms), sample characteristics (participants’ region), and performed a meta-regression analysis on gender and age in the context of PSNU and anxiety symptoms. It was found that the timing of measurement, tools used for assessing PSNU and anxiety, region, and gender had a moderating effect, whereas age did not show a significant moderating impact.

Firstly, the relationship between PSNU and anxiety symptoms was significantly higher during the COVID-19 period than before, especially between PSNU and GA. However, the moderating effect of measurement timing was not significant in the relationship between PSNU and other types of anxiety. This could be attributed to the increased uncertainty and stress during the pandemic, leading to heightened levels of general anxiety [ 227 ]. The overuse of social network for information seeking and anxiety alleviation might have paradoxically exacerbated anxiety symptoms, particularly among individuals with broad future-related worries [ 228 ]. While the COVID-19 pandemic altered the relationship between PSNU and GA, its impact on other types of anxiety (such as SA and AA) may not have been significant, likely due to these anxiety types being more influenced by other factors like social skills and attachment styles, which were minimally impacted by the epidemic.

Secondly, the observed variance in the relationship between PSNU and AA across different economic contexts, notably between developing and developed countries, underscores the multifaceted influence of socio-economic, cultural, and technological factors on this dynamic. The amplified connection in developing countries may be attributed to greater socio-economic challenges, distinct cultural norms regarding social support and interaction, rising social network penetration, especially among younger demographics, and technological disparities influencing accessibility and user experience [ 229 , 230 ]. Moreover, the role of social network as a coping mechanism for emotional distress, potentially fostering insecure attachment patterns, is more pronounced in these settings [ 231 ]. These findings highlight the necessity of considering contextual variations in assessing the psychological impacts of social network, advocating for a nuanced understanding of how socio-economic and cultural backgrounds mediate the relationship between PSNU and mental health outcomes [ 232 ]. Additionally, the relationship between PSNU and other types of anxiety (such as GA and SA) presents uniform characteristics across different economic contexts.

Thirdly, the significant moderating effects of measurement tools in the context of PSNU and its correlation with various forms of anxiety, including GA, and AA, are crucial in interpreting the research findings. Specifically, the study reveals that the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) demonstrates a stronger correlation between PSNU and GA, compared to other tools. Similarly, for AA, the Griffiths’ Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS2) and the Problematic Media Social Media Use Assessment Questionnaire (PMSMUAQ) show a more pronounced correlation with AA than the BSMAS or other instruments, but for SA and FoMO, the PSNU instrument doesn’t significantly moderate the correlation. The PSNU measurement tool typically contains an emotional change dimension. SA and FoMO, due to their specific conditional stimuli triggers and correlation with social networks [ 233 , 234 ], are likely to yield more consistent scores in this dimension, while GA and AA may be less reliable due to their lesser sensitivity to specific conditional stimuli. Consequently, the adjustment effects of PSNU measurements vary across anxiety symptoms. Regarding the measurement tools for anxiety, different scales exhibit varying degrees of sensitivity in detecting the relationship with PSNU. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD) and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21 (DASS-21) are more effective in illustrating a strong relationship between GA and PSNU than the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). In the case of AA, the Experiences in Close Relationships-21 (ECR-21) provides a more substantial correlation than the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ). Furthermore, for FoMO, the Fear of Missing Out Scale - Multi-Social Media Environment (FoMOS-MSME) is more indicative of a strong relationship with PSNU compared to the standard FoMOS or the T-S FoMOS. These findings underscore the importance of the selection of appropriate measurement tools in research. Different tools, due to their unique design, focus, and sensitivity, can reveal varying degrees of correlation between PSNU and anxiety disorders. This highlights the need for careful consideration of tool characteristics and their potential impact on research outcomes. It also cautions against drawing direct comparisons between studies without acknowledging the possible variances introduced by the use of different measurement instruments.

Fourthly, the significant moderating role of gender in the relationship between PSNU and SA, particularly pronounced in samples with a higher proportion of females. Women tend to engage more actively and emotionally with social network, potentially leading to an increased dependency on these platforms when confronting social anxiety [ 235 ]. This intensified use might amplify the association between PSNU and SA. Societal and cultural pressures, especially those related to appearance and social status, are known to disproportionately affect women, possibly exacerbating their experience of social anxiety and prompting a greater reliance on social network for validation and support [ 236 ]. Furthermore, women’s propensity to seek emotional support and express themselves on social network platforms [ 237 ] could strengthen this link, particularly in the context of managing social anxiety. Consequently, the observed gender differences in the relationship between PSNU and SA underscore the importance of considering gender-specific dynamics and cultural influences in psychological research related to social network use. In addition, gender consistency was observed in the association between PSNU and other types of anxiety, indicating no significant gender disparities.

Fifthly, the absence of a significant moderating effect of age on the relationship between PSNU and various forms of anxiety suggests a pervasive influence of social network across different age groups. This finding indicates that the impact of PSNU on anxiety is relatively consistent, irrespective of age, highlighting the universal nature of social network’s psychological implications [ 238 ]. Furthermore, this uniformity suggests that other factors, such as individual psychological traits or socio-cultural influences, might play a more crucial role in the development of anxiety related to social networking usage than age [ 239 ]. The non-significant role of age also points towards a potential generational overlap in social networking usage patterns and their psychological effects, challenging the notion that younger individuals are uniquely susceptible to the adverse effects of social network on mental health [ 240 ]. Therefore, this insight necessitates a broader perspective in understanding the dynamics of social network and mental health, one that transcends age-based assumptions.

Limitations

There are some limitations in this research. First, most of the studies were cross-sectional surveys, resulting in difficulties in inferring causality of variables, longitudinal study data will be needed to evaluate causal interactions in the future. Second, considerable heterogeneity was found in the estimated results, although heterogeneity can be partially explained by differences in study design (e.g., Time of measurement, region, gender, and measurement tools), but this can introduce some uncertainty in the aggregation and generalization of the estimated results. Third, most studies were based on Asian samples, which limits the generality of the results. Fourth, to minimize potential sources of heterogeneity, some less frequently used measurement tools were not included in the classification of measurement tools, which may have some impact on the results of heterogeneity interpretation. Finally, since most of the included studies used self-reported scales, it is possible to get results that deviate from the actual situation to some extent.

This meta-analysis aims to quantifies the correlations between PSNU and four specific types of anxiety symptoms (i.e., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, attachment anxiety, and fear of missing out). The results revealed a significant moderate positive association between PSNU and each of these anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, Subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis indicated that gender, region, time of measurement, and instrument of measurement significantly influenced the relationship between PSNU and specific anxiety symptoms. Specifically, the measurement time and GA measurement tools significantly influenced the relationship between PSNU and GA. Gender significantly influenced the relationship between PSNU and SA. Region, PSNU measurement tools, and AA measurement tools all significantly influenced the relationship between PSNU and AA. The FoMO measurement tool significantly influenced the relationship between PSNU and FoMO. Regarding these findings, prevention interventions for PSNU and anxiety symptoms are important.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Problematic social networking use

- Generalized anxiety

- Social anxiety

- Attachment anxiety

Fear of miss out

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

Facebook Addiction Scale

Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire

Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2

Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire

Social Network Addiction Tendency Scale

Brief Symptom Inventory

The anxiety subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

The anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Interaction Anxiousness Scale

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale

Social Anxiety Scale for Social Media Users

Social Anxiety for Adolescents

Social Anxiety Subscale of the Self-Consciousness Scale

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale

Experiences in Close Relationship Scale

Relationship questionnaire

Fear of Missing Out Scale

FoMO Measurement Scale in the Mobile Social Media Environment

Trait-State Fear of missing Out Scale

Rozgonjuk D, Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag C. Fear of missing out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat Use disorders mediate that association? Addict Behav. 2020;110:106487.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mieczkowski H, Lee AY, Hancock JT. Priming effects of social media use scales on well-being outcomes: the influence of intensity and addiction scales on self-reported depression. Social Media + Soc. 2020;6(4):2056305120961784.

Article Google Scholar

Global digital population as of April. 2023 [ https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ ].

Marengo D, Settanni M, Fabris MA, Longobardi C. Alone, together: fear of missing out mediates the link between peer exclusion in WhatsApp classmate groups and psychological adjustment in early-adolescent teens. J Social Personal Relationships. 2021;38(4):1371–9.

Marengo D, Fabris MA, Longobardi C, Settanni M. Smartphone and social media use contributed to individual tendencies towards social media addiction in Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav. 2022;126:107204.

Müller SM, Wegmann E, Stolze D, Brand M. Maximizing social outcomes? Social zapping and fear of missing out mediate the effects of maximization and procrastination on problematic social networks use. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;107:106296.

Sun Y, Zhang Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict Behav. 2021;114:106699.

Boustead R, Flack M. Moderated-mediation analysis of problematic social networking use: the role of anxious attachment orientation, fear of missing out and satisfaction with life. Addict Behav 2021, 119.

Hussain Z, Griffiths MD. The associations between problematic social networking Site Use and Sleep Quality, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Depression, anxiety and stress. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021;19(3):686–700.

Gori A, Topino E, Griffiths MD. The associations between attachment, self-esteem, fear of missing out, daily time expenditure, and problematic social media use: a path analysis model. Addict Behav. 2023;141:107633.

Marino C, Manari T, Vieno A, Imperato C, Spada MM, Franceschini C, Musetti A. Problematic social networking sites use and online social anxiety: the role of attachment, emotion dysregulation and motives. Addict Behav. 2023;138:107572.

Tobin SJ, Graham S. Feedback sensitivity as a mediator of the relationship between attachment anxiety and problematic Facebook Use. Cyberpsychology Behav Social Netw. 2020;23(8):562–6.

Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff H-W, Margraf J. The anxious addictive narcissist: the relationship between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, anxiety symptoms and Facebook Addiction. PLoS ONE 2020, 15(11).

Kim S-S, Bae S-M. Social Anxiety and Social Networking Service Addiction Proneness in University students: the Mediating effects of Experiential Avoidance and interpersonal problems. Psychiatry Invest. 2022;19(8):702–702.

Zhao J, Ye B, Yu L, Xia F. Effects of Stressors of COVID-19 on Chinese College Students’ Problematic Social Media Use: A Mediated Moderation Model. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13.

Astolfi Cury GS, Takannune DM, Prates Herrerias GS, Rivera-Sequeiros A, de Barros JR, Baima JP, Saad-Hossne R, Sassaki LY. Clinical and Psychological Factors Associated with Addiction and Compensatory Use of Facebook among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:1447–57.

Balta S, Emirtekin E, Kircaburun K, Griffiths MD. Neuroticism, trait fear of missing out, and Phubbing: the mediating role of state fear of missing out and problematic Instagram Use. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2020;18(3):628–39.

Boursier V, Gioia F, Griffiths MD. Do selfie-expectancies and social appearance anxiety predict adolescents’ problematic social media use? Comput Hum Behav. 2020;110:106395.

Worsley JD, McIntyre JC, Bentall RP, Corcoran R. Childhood maltreatment and problematic social media use: the role of attachment and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:88–93.

de Bérail P, Guillon M, Bungener C. The relations between YouTube addiction, social anxiety and parasocial relationships with YouTubers: a moderated-mediation model based on a cognitive-behavioral framework. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;99:190–204.

Naidu S, Chand A, Pandaram A, Patel A. Problematic internet and social network site use in young adults: the role of emotional intelligence and fear of negative evaluation. Pers Indiv Differ. 2023;200:111915.

Apaolaza V, Hartmann P, D’Souza C, Gilsanz A. Mindfulness, compulsive Mobile Social Media Use, and derived stress: the mediating roles of self-esteem and social anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behav Social Netw. 2019;22(6):388–96.

Demircioglu ZI, Goncu-Kose A. Antecedents of problematic social media use and cyberbullying among adolescents: attachment, the dark triad and rejection sensitivity. Curr Psychol (New Brunsw NJ) 2022:1–19.

Gao Q, Li Y, Zhu Z, Fu E, Bu X, Peng S, Xiang Y. What links to psychological needs satisfaction and excessive WeChat use? The mediating role of anxiety, depression and WeChat use intensity. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):105–105.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Malak MZ, Shuhaiber AH, Al-amer RM, Abuadas MH, Aburoomi RJ. Correlation between psychological factors, academic performance and social media addiction: model-based testing. Behav Inform Technol. 2022;41(8):1583–95.

Song C. The effect of the need to belong on mobile phone social media dependence of middle school students: Chain mediating roles of fear of missing out and maladaptive cognition. Sichuan Normal University; 2022.

Tokunaga RS, Rains SA. A review and meta-analysis examining conceptual and operational definitions of problematic internet use. Hum Commun Res. 2016;42(2):165–99.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media effects. edn.: Routledge; 2009. pp. 110–40.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J, Walther JB. Media effects: theory and research. Ann Rev Psychol. 2016;67:315–38.

Slater MD. Reinforcing spirals: the mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Communication Theory. 2007;17(3):281–303.

Ahmed E, Vaghefi I. Social media addiction: A systematic review through cognitive-behavior model of pathological use. 2021.

She R, han Mo PK, Li J, Liu X, Jiang H, Chen Y, Ma L, fai Lau JT. The double-edged sword effect of social networking use intensity on problematic social networking use among college students: the role of social skills and social anxiety. Comput Hum Behav. 2023;140:107555.

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(2):204–15.

Ran G, Li J, Zhang Q, Niu X. The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: a three-level meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2022;130:107198.

Fioravanti G, Casale S, Benucci SB, Prostamo A, Falone A, Ricca V, Rotella F. Fear of missing out and social networking sites use and abuse: a meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;122:106839.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Card NA. Applied meta-analysis for social science research. Guilford; 2015.

Peterson RA, Brown SP. On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(1):175.

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL. Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage; 2004.

Zhang Y, Li S, Yu G. The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: a meta-analysis with Chinese students. Adv Psychol Sci. 2019;27(6):1005–18.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley; 2021.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.