From Dilemmas to Solutions: Problem-Solving Examples to Learn From

- By Daria Burnett

- May 21, 2023

Introduction to Problem-Solving

Life is full of challenges and dilemmas, both big and small.

But if there’s one skill that can help you navigate these, it’s problem-solving .

So, what exactly is problem-solving? And why is it such a crucial skill in daily life?

Understanding the Concept of Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves identifying, analyzing, and resolving challenges or difficulties.

It’s like a journey that starts with a problem and ends with a solution.

It’s a skill that’s not just used in the field of psychology but in all aspects of life.

Whether you’re trying to decide on the best route to work, dealing with a disagreement with a friend, or figuring out how to fix a leaky faucet, you’re using your problem-solving skills.

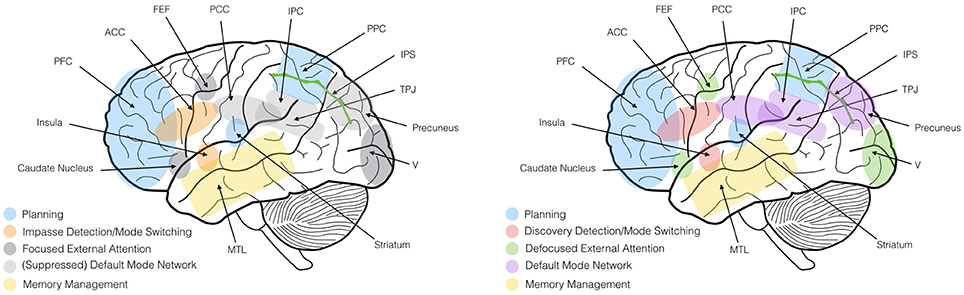

When you’re faced with a problem, your brain goes through a series of steps to find a solution.

This process can be conscious or unconscious and can involve logical thinking, creativity, and prior knowledge.

Effective problem-solving can lead to better decisions and outcomes, making it a valuable tool in your personal and professional life.

Related Posts:

- Your Path to Success: Best Career Options with a Psychology Degree

- Type C Personality Traits: The Power of Positivity

- Embrace the Change: Embodying the Democratic Leadership Style

Importance of Problem-Solving in Daily Life

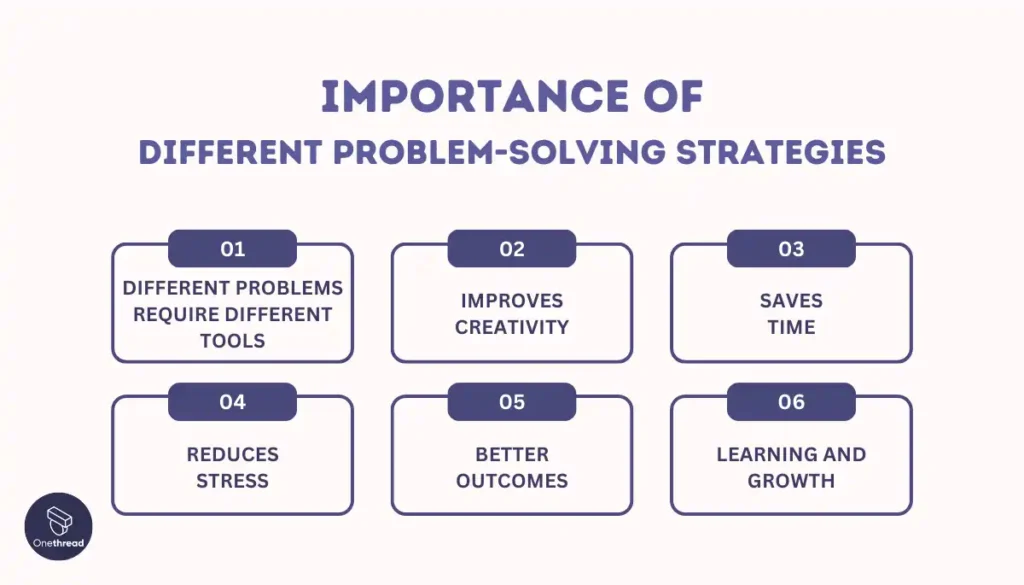

Why is problem-solving so important in daily life? Well, it’s simple.

Problems are a part of life.

They arise in different shapes and sizes, and in different areas of life, including work, relationships, health, and personal growth.

Having strong problem-solving skills can help you navigate these challenges effectively and efficiently.

In your personal life, problem-solving can help you manage stress and conflict, make better decisions, and achieve your goals.

In the workplace, it can help you navigate complex projects, improve processes, and foster innovation.

Problem-solving is also a key skill in many professions and industries, from engineering and science to healthcare and customer service.

Moreover, problem-solving can contribute to your overall mental well-being.

It can give you a sense of control and agency, reduce feelings of stress and anxiety, and foster a positive attitude.

It’s also a key component of resilience, the ability to bounce back from adversity.

In conclusion, problem-solving is a fundamental skill in life.

It’s a tool you can use to tackle challenges, make informed decisions, and drive change.

By understanding the concept of problem-solving and recognizing its importance in daily life, you’re taking the first step toward becoming a more effective problem solver.

As we delve deeper into this topic, you’ll discover practical problem-solving examples, learn about different problem-solving techniques, and gain insights on how to improve your own problem-solving skills.

So, stay tuned and continue your exploration of introduction to psychology with us.

Stages of Problem-Solving

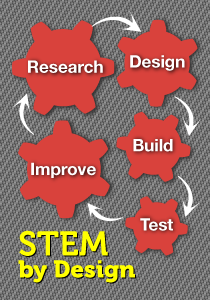

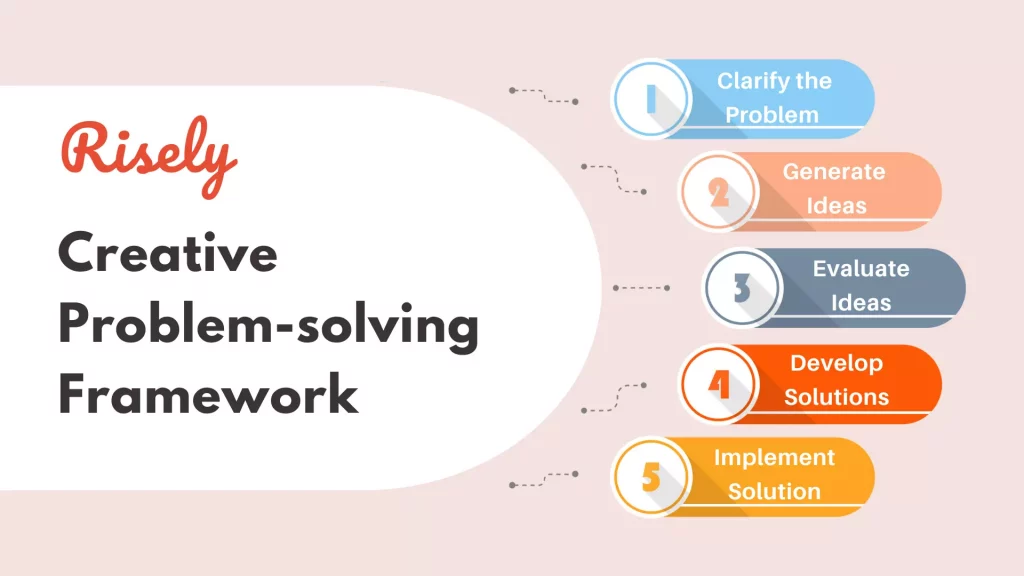

The process of problem-solving can be broken down into three key stages: identifying the problem , developing possible solutions , and implementing the best solution .

Each stage requires a different set of skills and strategies.

By understanding these stages, you can enhance your problem-solving abilities and tackle various challenges more effectively.

Identifying the Problem

The first step in problem-solving is recognizing that a problem exists.

This involves defining the issue clearly and understanding its root cause.

You might need to gather information, ask questions, and analyze the situation from multiple perspectives.

It can be helpful to write down the problem and think about how it impacts you or others involved.

For instance, if you’re struggling with time management, the problem might be that you have too many obligations and not enough time.

Or perhaps your methods of organizing your tasks aren’t effective.

It’s important to be as specific as possible when identifying the problem, as this will guide the rest of the problem-solving process.

Developing Possible Solutions

Once you’ve identified the problem, the next step is to brainstorm possible solutions.

This is where creativity comes into play.

Don’t limit yourself; even ideas that seem unrealistic or out of the box can lead to effective solutions.

Consider different strategies and approaches.

You could try using techniques like mind mapping, listing pros and cons, or consulting with others for fresh perspectives.

Remember, the goal is to generate a variety of options, not to choose a solution at this stage.

Implementing the Best Solution

The final stage of problem-solving is to select the best solution and put it into action.

Review the options you’ve developed, evaluate their potential effectiveness, and make a decision.

Keep in mind that the “best” solution isn’t necessarily the perfect one (as there might not be a perfect solution), but rather the one that seems most likely to achieve your desired outcome given the circumstances.

Once you’ve chosen a solution, plan out the steps needed to implement it and then take action.

Monitor the results and adjust your approach as necessary.

If the problem persists, don’t be discouraged; return to the previous stages, reassess the problem and your potential solutions, and try again.

Remember, problem-solving is a dynamic process that often involves trial and error.

It’s an essential skill in many areas of life, from everyday challenges to workplace dilemmas.

To learn more about the psychology behind problem-solving and decision-making, check out our introduction to psychology article.

Problem-Solving Examples

Understanding the concept of problem-solving is one thing, but seeing it in action is another.

To help you grasp the practical application of problem-solving strategies, let’s explore three different problem-solving examples from daily life, the workplace, and relationships.

Daily Life Problem-Solving Example

Imagine you’re trying to lose weight but struggle with late-night snacking.

The issue isn’t uncommon, but it’s hindering your progress towards your weight loss goal.

- Identifying the Problem : Late-night snacking is causing you to consume extra calories, preventing weight loss.

- Developing Possible Solutions : You could consider eating an earlier dinner, having a healthier snack option, or practicing mindful eating.

- Implementing the Best Solution : After trying out different solutions, you find that preparing a healthy snack in advance minimizes your calorie intake and satisfies your late-night cravings, helping you stay on track with your weight loss goal.

Workplace Problem-Solving Example

Let’s consider a scenario where a team at work is failing to meet project deadlines consistently.

- Identifying the Problem : The team is not completing projects on time, causing delays in the overall project timeline.

- Developing Possible Solutions : The team could consider improving their time management skills, using project management tools, or redistributing tasks among team members.

- Implementing the Best Solution : After trying out different strategies, the team finds that using a project management tool helps them stay organized, delegate tasks effectively, and complete projects within the given timeframe.

For more insights on effective management styles that can help in problem-solving at the workplace, check out our articles on autocratic leadership , democratic leadership style , and laissez faire leadership .

Relationship Problem-Solving Example

In a romantic relationship, conflicts can occasionally arise.

Let’s imagine a common issue where one partner feels the other isn’t spending enough quality time with them.

- Identifying the Problem : One partner feels neglected due to a lack of quality time spent together.

- Developing Possible Solutions : The couple could consider scheduling regular date nights, engaging in shared hobbies, or setting aside a specific time each day for undisturbed conversation.

- Implementing the Best Solution : The couple decides to implement a daily “unplugged” hour where they focus solely on each other without distractions. This results in improved relationship satisfaction.

For more on navigating relationship challenges, check out our articles on anxious avoidant attachment and emotional awareness .

These problem-solving examples illustrate how the process of identifying a problem, developing possible solutions, and implementing the best solution can be applied to various situations.

By understanding and applying these strategies, you can improve your problem-solving skills and navigate challenges more effectively.

Techniques for Effective Problem-Solving

As you navigate the world of problem-solving, you’ll find that there are multiple techniques you can use to arrive at a solution.

Each technique offers a unique approach to identifying issues, generating potential solutions, and choosing the best course of action.

In this section, we’ll explore three common techniques: Brainstorming , Root Cause Analysis , and SWOT Analysis .

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a free-thinking method used to generate a large number of ideas related to a specific problem.

You do this by suspending criticism and allowing your creativity to flow.

The aim is to produce as many ideas as possible, even if they seem far-fetched.

You then evaluate these ideas to identify the most beneficial solutions.

By using brainstorming, you can encourage out-of-the-box thinking and possibly discover innovative solutions to challenging problems.

Root Cause Analysis

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a method used to identify the underlying causes of a problem.

The goal is to address these root causes rather than the symptoms of the problem.

This technique helps to prevent the same issue from recurring in the future.

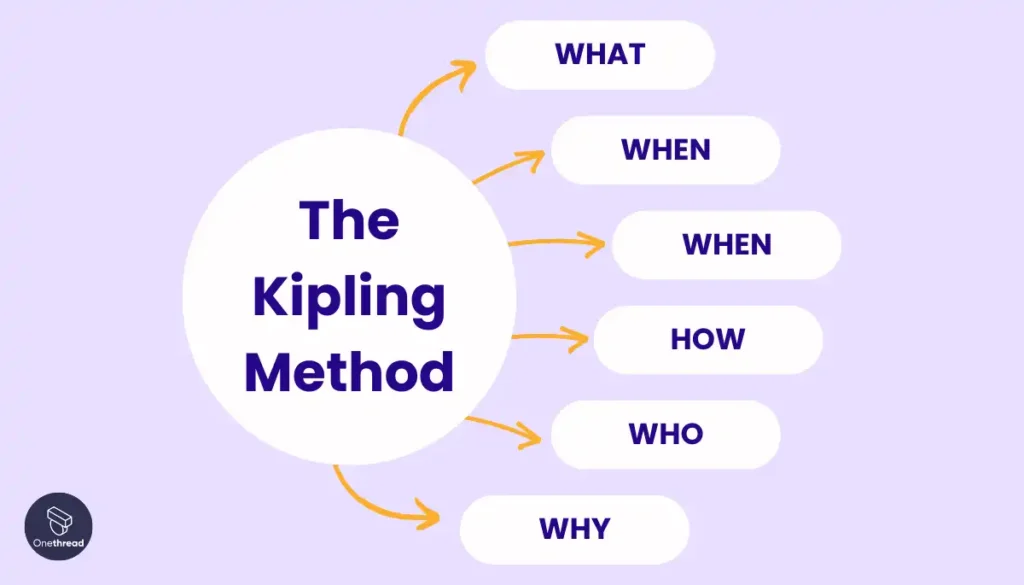

There are several RCA methods, such as the “5 Whys” technique, where you ask “why” multiple times until you uncover the root cause of the problem.

By identifying and addressing the root cause, you tackle the problem at its source, which can lead to more effective and long-lasting solutions.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is a strategic planning technique that helps you identify your Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats related to a problem.

This approach encourages you to examine the problem from different angles, helping you understand the resources you have at your disposal (Strengths), the areas where you could improve (Weaknesses), the external factors that could benefit you (Opportunities), and the external factors that could cause problems (Threats).

With this comprehensive understanding, you can develop a well-informed strategy to solve the problem.

Each of these problem-solving techniques provides a distinct approach to identifying and resolving issues.

By understanding and utilizing these methods, you can enhance your problem-solving skills and increase your effectiveness in dealing with challenges.

For more insights into effective problem-solving and other psychological topics, explore our introduction to psychology .

Improving Your Problem-Solving Skills

Learning to solve problems effectively is a skill that can be honed with time and practice.

The following are some ways to enhance your problem-solving capabilities.

Practice Makes Perfect

The saying “practice makes perfect” holds true when it comes to problem-solving.

The more problems you tackle, the better you’ll become at devising and implementing effective solutions.

Seek out opportunities to practice your problem-solving skills both in everyday life and in more complex situations.

This could involve resolving a dispute at work, figuring out a puzzle, or even strategizing in a board game.

Each problem you encounter is a new opportunity to apply and refine your skills.

Learning from Others’ Experiences

There’s much to be gained from observing how others approach problem-solving.

Whether it’s reading about problem solving examples from renowned psychologists or discussing strategies with colleagues, you can learn valuable techniques and perspectives from the experiences of others.

Consider participating in group activities that require problem-solving, such as escape rooms or team projects.

Observe how team members identify problems, brainstorm solutions, and decide on the best course of action.

Embracing a Growth Mindset

A key component of effective problem-solving is adopting a growth mindset.

This mindset, coined by psychologist Carol Dweck, is the belief that abilities and intelligence can be developed through dedication and hard work.

When you embrace a growth mindset, you view challenges as opportunities to learn and grow rather than as insurmountable obstacles.

Believing in your ability to develop and enhance your problem-solving skills over time can make the process less daunting and more rewarding.

So, when you encounter a problem, instead of thinking, “I can’t do this,” try thinking, “I can’t do this yet, but with effort and practice, I can learn.”

For more on the growth mindset, you might want to check out our article on what is intrinsic motivation which includes how a growth mindset can fuel your motivation to improve.

By practicing regularly, learning from others, and embracing a growth mindset, you can continually improve your problem-solving skills and become more adept at overcoming challenges you encounter.

Culture Development

Workplace problem-solving examples: real scenarios, practical solutions.

- March 11, 2024

In today’s fast-paced and ever-changing work environment, problems are inevitable. From conflicts among employees to high levels of stress, workplace problems can significantly impact productivity and overall well-being. However, by developing the art of problem-solving and implementing practical solutions, organizations can effectively tackle these challenges and foster a positive work culture. In this article, we will delve into various workplace problem scenarios and explore strategies for resolution. By understanding common workplace problems and acquiring essential problem-solving skills, individuals and organizations can navigate these challenges with confidence and success.

Understanding Workplace Problems

Before we can effectively solve workplace problems , it is essential to gain a clear understanding of the issues at hand. Identifying common workplace problems is the first step toward finding practical solutions. By recognizing these challenges, organizations can develop targeted strategies and initiatives to address them.

Identifying Common Workplace Problems

One of the most common workplace problems is conflict. Whether it stems from differences in opinions, miscommunication, or personality clashes, conflict can disrupt collaboration and hinder productivity. It is important to note that conflict is a natural part of any workplace, as individuals with different backgrounds and perspectives come together to work towards a common goal. However, when conflict is not managed effectively, it can escalate and create a toxic work environment.

In addition to conflict, workplace stress and burnout pose significant challenges. High workloads, tight deadlines, and a lack of work-life balance can all contribute to employee stress and dissatisfaction. When employees are overwhelmed and exhausted, their performance and overall well-being are compromised. This not only affects the individuals directly, but it also has a ripple effect on the entire organization.

Another common workplace problem is poor communication. Ineffective communication can lead to misunderstandings, delays, and errors. It can also create a sense of confusion and frustration among employees. Clear and open communication is vital for successful collaboration and the smooth functioning of any organization.

The Impact of Workplace Problems on Productivity

Workplace problems can have a detrimental effect on productivity levels. When conflicts are left unresolved, they can create a tense work environment, leading to decreased employee motivation and engagement. The negative energy generated by unresolved conflicts can spread throughout the organization, affecting team dynamics and overall performance.

Similarly, high levels of stress and burnout can result in decreased productivity, as individuals may struggle to focus and perform optimally. When employees are constantly under pressure and overwhelmed, their ability to think creatively and problem-solve diminishes. This can lead to a decline in the quality of work produced and an increase in errors and inefficiencies.

Poor communication also hampers productivity. When information is not effectively shared or understood, it can lead to misunderstandings, delays, and rework. This not only wastes time and resources but also creates frustration and demotivation among employees.

Furthermore, workplace problems can negatively impact employee morale and job satisfaction. When individuals are constantly dealing with conflicts, stress, and poor communication, their overall job satisfaction and engagement suffer. This can result in higher turnover rates, as employees seek a healthier and more supportive work environment.

In conclusion, workplace problems such as conflict, stress, burnout, and poor communication can significantly hinder productivity and employee well-being. Organizations must address these issues promptly and proactively to create a positive and productive work atmosphere. By fostering open communication, providing support for stress management, and promoting conflict resolution strategies, organizations can create a work environment that encourages collaboration, innovation, and employee satisfaction.

The Art of Problem Solving in the Workplace

Now that we have a clear understanding of workplace problems, let’s explore the essential skills necessary for effective problem-solving in the workplace. By developing these skills and adopting a proactive approach, individuals can tackle problems head-on and find practical solutions.

Problem-solving in the workplace is a complex and multifaceted skill that requires a combination of analytical thinking, creativity, and effective communication. It goes beyond simply identifying problems and extends to finding innovative solutions that address the root causes.

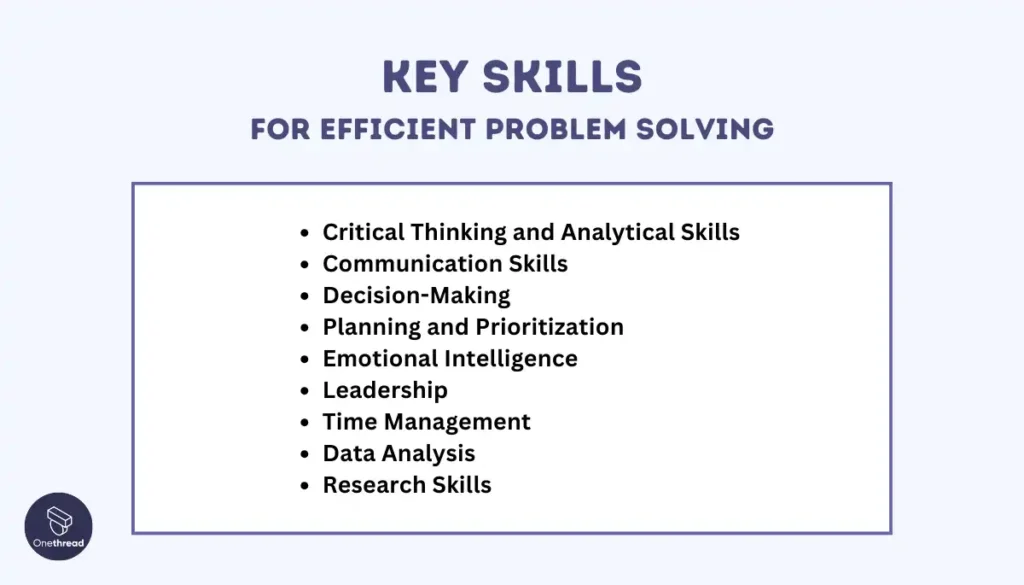

Essential Problem-Solving Skills for the Workplace

To effectively solve workplace problems, individuals should possess a range of skills. These include strong analytical and critical thinking abilities, excellent communication and interpersonal skills, the ability to collaborate and work well in a team, and the capacity to adapt to change. By honing these skills, individuals can approach workplace problems with confidence and creativity.

Analytical and critical thinking skills are essential for problem-solving in the workplace. They involve the ability to gather and analyze relevant information, identify patterns and trends, and make logical connections. These skills enable individuals to break down complex problems into manageable components and develop effective strategies to solve them.

Effective communication and interpersonal skills are also crucial for problem-solving in the workplace. These skills enable individuals to clearly articulate their thoughts and ideas, actively listen to others, and collaborate effectively with colleagues. By fostering open and honest communication channels, individuals can better understand the root causes of problems and work towards finding practical solutions.

Collaboration and teamwork are essential for problem-solving in the workplace. By working together, individuals can leverage their diverse skills, knowledge, and perspectives to generate innovative solutions. Collaboration fosters a supportive and inclusive environment where everyone’s ideas are valued, leading to more effective problem-solving outcomes.

The ability to adapt to change is another important skill for problem-solving in the workplace. In today’s fast-paced and dynamic work environment, problems often arise due to changes in technology, processes, or market conditions. Individuals who can embrace change and adapt quickly are better equipped to find solutions that address the evolving needs of the organization.

The Role of Communication in Problem Solving

Communication is a key component of effective problem-solving in the workplace. By fostering open and honest communication channels, individuals can better understand the root causes of problems and work towards finding practical solutions. Active listening, clear and concise articulation of thoughts and ideas, and the ability to empathize are all valuable communication skills that facilitate problem-solving.

Active listening involves fully engaging with the speaker, paying attention to both verbal and non-verbal cues, and seeking clarification when necessary. By actively listening, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of the problem at hand and the perspectives of others involved. This understanding is crucial for developing comprehensive and effective solutions.

Clear and concise articulation of thoughts and ideas is essential for effective problem-solving communication. By expressing oneself clearly, individuals can ensure that their ideas are understood by others. This clarity helps to avoid misunderstandings and promotes effective collaboration.

Empathy is a valuable communication skill that plays a significant role in problem-solving. By putting oneself in the shoes of others and understanding their emotions and perspectives, individuals can build trust and rapport. This empathetic connection fosters a supportive and collaborative environment where everyone feels valued and motivated to contribute to finding solutions.

In conclusion, problem-solving in the workplace requires a combination of essential skills such as analytical thinking, effective communication, collaboration, and adaptability. By honing these skills and fostering open communication channels, individuals can approach workplace problems with confidence and creativity, leading to practical and innovative solutions.

Real Scenarios of Workplace Problems

Now, let’s explore some real scenarios of workplace problems and delve into strategies for resolution. By examining these practical examples, individuals can develop a deeper understanding of how to approach and solve workplace problems.

Conflict Resolution in the Workplace

Imagine a scenario where two team members have conflicting ideas on how to approach a project. The disagreement becomes heated, leading to a tense work environment. To resolve this conflict, it is crucial to encourage open dialogue between the team members. Facilitating a calm and respectful conversation can help uncover underlying concerns and find common ground. Collaboration and compromise are key in reaching a resolution that satisfies all parties involved.

In this particular scenario, let’s dive deeper into the dynamics between the team members. One team member, let’s call her Sarah, strongly believes that a more conservative and traditional approach is necessary for the project’s success. On the other hand, her colleague, John, advocates for a more innovative and out-of-the-box strategy. The clash between their perspectives arises from their different backgrounds and experiences.

As the conflict escalates, it is essential for a neutral party, such as a team leader or a mediator, to step in and facilitate the conversation. This person should create a safe space for both Sarah and John to express their ideas and concerns without fear of judgment or retribution. By actively listening to each other, they can gain a better understanding of the underlying motivations behind their respective approaches.

During the conversation, it may become apparent that Sarah’s conservative approach stems from a fear of taking risks and a desire for stability. On the other hand, John’s innovative mindset is driven by a passion for pushing boundaries and finding creative solutions. Recognizing these underlying motivations can help foster empathy and create a foundation for collaboration.

As the dialogue progresses, Sarah and John can begin to identify areas of overlap and potential compromise. They may realize that while Sarah’s conservative approach provides stability, John’s innovative ideas can inject fresh perspectives into the project. By combining their strengths and finding a middle ground, they can develop a hybrid strategy that incorporates both stability and innovation.

Ultimately, conflict resolution in the workplace requires effective communication, active listening, empathy, and a willingness to find common ground. By addressing conflicts head-on and fostering a collaborative environment, teams can overcome challenges and achieve their goals.

Dealing with Workplace Stress and Burnout

Workplace stress and burnout can be debilitating for individuals and organizations alike. In this scenario, an employee is consistently overwhelmed by their workload and experiencing signs of burnout. To address this issue, organizations should promote a healthy work-life balance and provide resources to manage stress effectively. Encouraging employees to take breaks, providing access to mental health support, and fostering a supportive work culture are all practical solutions to alleviate workplace stress.

In this particular scenario, let’s imagine that the employee facing stress and burnout is named Alex. Alex has been working long hours, often sacrificing personal time and rest to meet tight deadlines and demanding expectations. As a result, Alex is experiencing physical and mental exhaustion, reduced productivity, and a sense of detachment from work.

Recognizing the signs of burnout, Alex’s organization takes proactive measures to address the issue. They understand that employee well-being is crucial for maintaining a healthy and productive workforce. To promote a healthy work-life balance, the organization encourages employees to take regular breaks and prioritize self-care. They emphasize the importance of disconnecting from work during non-working hours and encourage employees to engage in activities that promote relaxation and rejuvenation.

Additionally, the organization provides access to mental health support services, such as counseling or therapy sessions. They recognize that stress and burnout can have a significant impact on an individual’s mental well-being and offer resources to help employees manage their stress effectively. By destigmatizing mental health and providing confidential support, the organization creates an environment where employees feel comfortable seeking help when needed.

Furthermore, the organization fosters a supportive work culture by promoting open communication and empathy. They encourage managers and colleagues to check in with each other regularly, offering support and understanding. Team members are encouraged to collaborate and share the workload, ensuring that no one person is overwhelmed with excessive responsibilities.

By implementing these strategies, Alex’s organization aims to alleviate workplace stress and prevent burnout. They understand that a healthy and balanced workforce is more likely to be engaged, productive, and satisfied. Through a combination of promoting work-life balance, providing mental health support, and fostering a supportive work culture, organizations can effectively address workplace stress and create an environment conducive to employee well-being.

Practical Solutions to Workplace Problems

Now that we have explored real scenarios, let’s discuss practical solutions that organizations can implement to address workplace problems. By adopting proactive strategies and establishing effective policies, organizations can create a positive work environment conducive to problem-solving and productivity.

Implementing Effective Policies for Problem Resolution

Organizations should have clear and well-defined policies in place to address workplace problems. These policies should outline procedures for conflict resolution, channels for reporting problems, and accountability measures. By ensuring that employees are aware of these policies and have easy access to them, organizations can facilitate problem-solving and prevent issues from escalating.

Promoting a Positive Workplace Culture

A positive workplace culture is vital for problem-solving. By fostering an environment of respect, collaboration, and open communication, organizations can create a space where individuals feel empowered to address and solve problems. Encouraging teamwork, recognizing and appreciating employees’ contributions, and promoting a healthy work-life balance are all ways to cultivate a positive workplace culture.

The Role of Leadership in Problem Solving

Leadership plays a crucial role in facilitating effective problem-solving within organizations. Different leadership styles can impact how problems are approached and resolved.

Leadership Styles and Their Impact on Problem-Solving

Leaders who adopt an autocratic leadership style may make decisions independently, potentially leaving their team members feeling excluded and undervalued. On the other hand, leaders who adopt a democratic leadership style involve their team members in the problem-solving process, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment. By encouraging employee participation, organizations can leverage the diverse perspectives and expertise of their workforce to find innovative solutions to workplace problems.

Encouraging Employee Participation in Problem Solving

To harness the collective problem-solving abilities of an organization, it is crucial to encourage employee participation. Leaders can create opportunities for employees to contribute their ideas and perspectives through brainstorming sessions, team meetings, and collaborative projects. By valuing employee input and involving them in decision-making processes, organizations can foster a culture of inclusivity and drive innovative problem-solving efforts.

In today’s dynamic work environment, workplace problems are unavoidable. However, by understanding common workplace problems, developing essential problem-solving skills, and implementing practical solutions, individuals and organizations can navigate these challenges effectively. By fostering a positive work culture, implementing effective policies, and encouraging employee participation, organizations can create an environment conducive to problem-solving and productivity. With proactive problem-solving strategies in place, organizations can thrive and overcome obstacles, ensuring long-term success and growth.

Related Stories

- April 17, 2024

Understanding the Organizational Culture Profile: A Deeper Look into Core Values

Culture statement examples: inspiring your business growth.

- April 16, 2024

Fostering a Healthy Organizational Culture: Key Strategies and Benefits

What can we help you find.

50 Problem-Solving and Critical Thinking Examples

Critical thinking and problem solving are essential skills for success in the 21st century. Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information, evaluate evidence, and draw logical conclusions. Problem solving is the ability to apply critical thinking to find effective solutions to various challenges. Both skills require creativity, curiosity, and persistence. Developing critical thinking and problem solving skills can help students improve their academic performance, enhance their career prospects, and become more informed and engaged citizens.

Sanju Pradeepa

In today’s complex and fast-paced world, the ability to think critically and solve problems effectively has become a vital skill for success in all areas of life. Whether it’s navigating professional challenges, making sound decisions, or finding innovative solutions, critical thinking and problem-solving are key to overcoming obstacles and achieving desired outcomes. In this blog post, we will explore problem-solving and critical thinking examples.

Table of Contents

Developing the skills needed for critical thinking and problem solving.

It is not enough to simply recognize an issue; we must use the right tools and techniques to address it. To do this, we must learn how to define and identify the problem or task at hand, gather relevant information from reliable sources, analyze and compare data to draw conclusions, make logical connections between different ideas, generate a solution or action plan, and make a recommendation.

The first step in developing these skills is understanding what the problem or task is that needs to be addressed. This requires careful consideration of all available information in order to form an accurate picture of what needs to be done. Once the issue has been identified, gathering reliable sources of data can help further your understanding of it. Sources could include interviews with customers or stakeholders, surveys, industry reports, and analysis of customer feedback.

After collecting relevant information from reliable sources, it’s important to analyze and compare the data in order to draw meaningful conclusions about the situation at hand. This helps us better understand our options for addressing an issue by providing context for decision-making. Once you have analyzed the data you collected, making logical connections between different ideas can help you form a more complete picture of the situation and inform your potential solutions.

Once you have analyzed your options for addressing an issue based on all available data points, it’s time to generate a solution or action plan that takes into account considerations such as cost-effectiveness and feasibility. It’s also important to consider the risk factors associated with any proposed solutions in order to ensure that they are responsible before moving forward with implementation. Finally, once all the analysis has been completed, it is time to make a recommendation based on your findings, which should take into account any objectives set out by stakeholders at the beginning of this process as well as any other pertinent factors discovered throughout the analysis stage.

By following these steps carefully when faced with complex issues, one can effectively use critical thinking and problem-solving skills in order to achieve desired outcomes more efficiently than would otherwise be possible without them, while also taking responsibility for decisions made along the way.

What Does Critical Thinking Involve: 5 Essential Skill

Problem-solving and critical thinking examples.

Problem-solving and critical thinking are key skills that are highly valued in any professional setting. These skills enable individuals to analyze complex situations, make informed decisions, and find innovative solutions. Here, we present 25 examples of problem-solving and critical thinking. problem-solving scenarios to help you cultivate and enhance these skills.

Ethical dilemma: A company faces a situation where a client asks for a product that does not meet quality standards. The team must decide how to address the client’s request without compromising the company’s credibility or values.

Brainstorming session: A team needs to come up with new ideas for a marketing campaign targeting a specific demographic. Through an organized brainstorming session, they explore various approaches and analyze their potential impact.

Troubleshooting technical issues : An IT professional receives a ticket indicating a network outage. They analyze the issue, assess potential causes (hardware, software, or connectivity), and solve the problem efficiently.

Negotiation : During contract negotiations, representatives from two companies must find common ground to strike a mutually beneficial agreement, considering the needs and limitations of both parties.

Project management: A project manager identifies potential risks and develops contingency plans to address unforeseen obstacles, ensuring the project stays on track.

Decision-making under pressure: In a high-stakes situation, a medical professional must make a critical decision regarding a patient’s treatment, weighing all available information and considering potential risks.

Conflict resolution: A team encounters conflicts due to differing opinions or approaches. The team leader facilitates a discussion to reach a consensus while considering everyone’s perspectives.

Data analysis: A data scientist is presented with a large dataset and is tasked with extracting valuable insights. They apply analytical techniques to identify trends, correlations, and patterns that can inform decision-making.

Customer service: A customer service representative encounters a challenging customer complaint and must employ active listening and problem-solving skills to address the issue and provide a satisfactory resolution.

Market research : A business seeks to expand into a new market. They conduct thorough market research, analyzing consumer behavior, competitor strategies, and economic factors to make informed market-entry decisions.

Creative problem-solvin g: An engineer faces a design challenge and must think outside the box to come up with a unique and innovative solution that meets project requirements.

Change management: During a company-wide transition, managers must effectively communicate the change, address employees’ concerns, and facilitate a smooth transition process.

Crisis management: When a company faces a public relations crisis, effective critical thinking is necessary to analyze the situation, develop a response strategy, and minimize potential damage to the company’s reputation.

Cost optimization : A financial analyst identifies areas where expenses can be reduced while maintaining operational efficiency, presenting recommendations for cost savings.

Time management : An employee has multiple deadlines to meet. They assess the priority of each task, develop a plan, and allocate time accordingly to achieve optimal productivity.

Quality control: A production manager detects an increase in product defects and investigates the root causes, implementing corrective actions to enhance product quality.

Strategic planning: An executive team engages in strategic planning to define long-term goals, assess market trends, and identify growth opportunities.

Cross-functional collaboration: Multiple teams with different areas of expertise must collaborate to develop a comprehensive solution, combining their knowledge and skills.

Training and development : A manager identifies skill gaps in their team and designs training programs to enhance critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making abilities.

Risk assessment : A risk management professional evaluates potential risks associated with a new business venture, weighing their potential impact and developing strategies to mitigate them.

Continuous improvement: An operations manager analyzes existing processes, identifies inefficiencies, and introduces improvements to enhance productivity and customer satisfaction.

Customer needs analysis: A product development team conducts extensive research to understand customer needs and preferences, ensuring that the resulting product meets those requirements.

Crisis decision-making: A team dealing with a crisis must think quickly, assess the situation, and make timely decisions with limited information.

Marketing campaign analysis : A marketing team evaluates the success of a recent campaign, analyzing key performance indicators to understand its impact on sales and customer engagement.

Constructive feedback: A supervisor provides feedback to an employee, highlighting areas for improvement and offering constructive suggestions for growth.

Conflict resolution in a team project: Team members engaged in a project have conflicting ideas on the approach. They must engage in open dialogue, actively listen to each other’s perspectives, and reach a compromise that aligns with the project’s goals.

Crisis response in a natural disaster: Emergency responders must think critically and swiftly in responding to a natural disaster, coordinating rescue efforts, allocating resources effectively, and prioritizing the needs of affected individuals.

Product innovation : A product development team conducts market research, studies consumer trends, and uses critical thinking to create innovative products that address unmet customer needs.

Supply chain optimization: A logistics manager analyzes the supply chain to identify areas for efficiency improvement, such as reducing transportation costs, improving inventory management, or streamlining order fulfillment processes.

Business strategy formulation: A business executive assesses market dynamics, the competitive landscape, and internal capabilities to develop a robust business strategy that ensures sustainable growth and competitiveness.

Crisis communication: In the face of a public relations crisis, an organization’s spokesperson must think critically to develop and deliver a transparent, authentic, and effective communication strategy to rebuild trust and manage reputation.

Social problem-solving: A group of volunteers addresses a specific social issue, such as poverty or homelessness, by critically examining its root causes, collaborating with stakeholders, and implementing sustainable solutions for the affected population.

Problem-Solving Mindset: How to Achieve It (15 Ways)

Risk assessment in investment decision-making: An investment analyst evaluates various investment opportunities, conducting risk assessments based on market trends, financial indicators, and potential regulatory changes to make informed investment recommendations.

Environmental sustainability: An environmental scientist analyzes the impact of industrial processes on the environment, develops strategies to mitigate risks, and promotes sustainable practices within organizations and communities.

Adaptation to technological advancements : In a rapidly evolving technological landscape, professionals need critical thinking skills to adapt to new tools, software, and systems, ensuring they can effectively leverage these advancements to enhance productivity and efficiency.

Productivity improvement: An operations manager leverages critical thinking to identify productivity bottlenecks within a workflow and implement process improvements to optimize resource utilization, minimize waste, and increase overall efficiency.

Cost-benefit analysis: An organization considering a major investment or expansion opportunity conducts a thorough cost-benefit analysis, weighing potential costs against expected benefits to make an informed decision.

Human resources management : HR professionals utilize critical thinking to assess job applicants, identify skill gaps within the organization, and design training and development programs to enhance the workforce’s capabilities.

Root cause analysis: In response to a recurring problem or inefficiency, professionals apply critical thinking to identify the root cause of the issue, develop remedial actions, and prevent future occurrences.

Leadership development: Aspiring leaders undergo critical thinking exercises to enhance their decision-making abilities, develop strategic thinking skills, and foster a culture of innovation within their teams.

Brand positioning : Marketers conduct comprehensive market research and consumer behavior analysis to strategically position a brand, differentiating it from competitors and appealing to target audiences effectively.

Resource allocation: Non-profit organizations distribute limited resources efficiently, critically evaluating project proposals, considering social impact, and allocating resources to initiatives that align with their mission.

Innovating in a mature market: A company operating in a mature market seeks to innovate to maintain a competitive edge. They cultivate critical thinking skills to identify gaps, anticipate changing customer needs, and develop new strategies, products, or services accordingly.

Analyzing financial statements : Financial analysts critically assess financial statements, analyze key performance indicators, and derive insights to support financial decision-making, such as investment evaluations or budget planning.

Crisis intervention : Mental health professionals employ critical thinking and problem-solving to assess crises faced by individuals or communities, develop intervention plans, and provide support during challenging times.

Data privacy and cybersecurity : IT professionals critically evaluate existing cybersecurity measures, identify vulnerabilities, and develop strategies to protect sensitive data from threats, ensuring compliance with privacy regulations.

Process improvement : Professionals in manufacturing or service industries critically evaluate existing processes, identify inefficiencies, and implement improvements to optimize efficiency, quality, and customer satisfaction.

Multi-channel marketing strategy : Marketers employ critical thinking to design and execute effective marketing campaigns across various channels such as social media, web, print, and television, ensuring a cohesive brand experience for customers.

Peer review: Researchers critically analyze and review the work of their peers, providing constructive feedback and ensuring the accuracy, validity, and reliability of scientific studies.

Project coordination : A project manager must coordinate multiple teams and resources to ensure seamless collaboration, identify potential bottlenecks, and find solutions to keep the project on schedule.

These examples highlight the various contexts in which problem-solving and critical-thinking skills are necessary for success. By understanding and practicing these skills, individuals can enhance their ability to navigate challenges and make sound decisions in both personal and professional endeavors.

Conclusion:

Critical thinking and problem-solving are indispensable skills that empower individuals to overcome challenges, make sound decisions, and find innovative solutions. By honing these skills, one can navigate through the complexities of modern life and achieve success in both personal and professional endeavors. Embrace the power of critical thinking and problem-solving, and unlock the door to endless possibilities and growth.

- Problem solving From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Critical thinking From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- The Importance of Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills for Students (5 Minutes)

Let’s boost your self-growth with Believe in Mind.

Interested in self-reflection tips, learning hacks, and knowing ways to calm down your mind? We offer you the best content which you have been looking for.

Follow Me on

You May Like Also

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

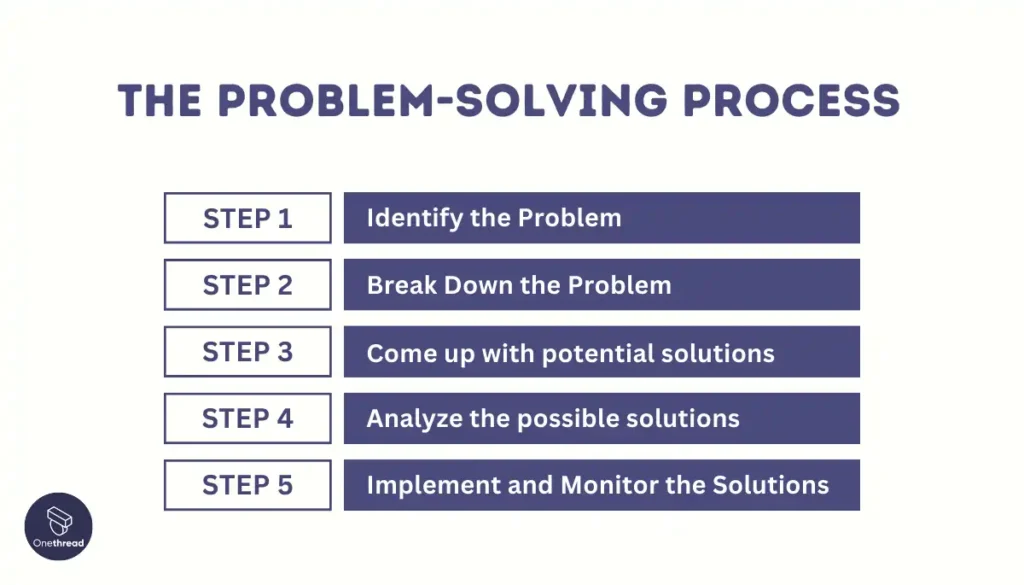

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

35 problem-solving techniques and methods for solving complex problems

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

All teams and organizations encounter challenges as they grow. There are problems that might occur for teams when it comes to miscommunication or resolving business-critical issues . You may face challenges around growth , design , user engagement, and even team culture and happiness. In short, problem-solving techniques should be part of every team’s skillset.

Problem-solving methods are primarily designed to help a group or team through a process of first identifying problems and challenges , ideating possible solutions , and then evaluating the most suitable .

Finding effective solutions to complex problems isn’t easy, but by using the right process and techniques, you can help your team be more efficient in the process.

So how do you develop strategies that are engaging, and empower your team to solve problems effectively?

In this blog post, we share a series of problem-solving tools you can use in your next workshop or team meeting. You’ll also find some tips for facilitating the process and how to enable others to solve complex problems.

Let’s get started!

How do you identify problems?

How do you identify the right solution.

- Tips for more effective problem-solving

Complete problem-solving methods

- Problem-solving techniques to identify and analyze problems

- Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

Problem-solving warm-up activities

Closing activities for a problem-solving process.

Before you can move towards finding the right solution for a given problem, you first need to identify and define the problem you wish to solve.

Here, you want to clearly articulate what the problem is and allow your group to do the same. Remember that everyone in a group is likely to have differing perspectives and alignment is necessary in order to help the group move forward.

Identifying a problem accurately also requires that all members of a group are able to contribute their views in an open and safe manner. It can be scary for people to stand up and contribute, especially if the problems or challenges are emotive or personal in nature. Be sure to try and create a psychologically safe space for these kinds of discussions.

Remember that problem analysis and further discussion are also important. Not taking the time to fully analyze and discuss a challenge can result in the development of solutions that are not fit for purpose or do not address the underlying issue.

Successfully identifying and then analyzing a problem means facilitating a group through activities designed to help them clearly and honestly articulate their thoughts and produce usable insight.

With this data, you might then produce a problem statement that clearly describes the problem you wish to be addressed and also state the goal of any process you undertake to tackle this issue.

Finding solutions is the end goal of any process. Complex organizational challenges can only be solved with an appropriate solution but discovering them requires using the right problem-solving tool.

After you’ve explored a problem and discussed ideas, you need to help a team discuss and choose the right solution. Consensus tools and methods such as those below help a group explore possible solutions before then voting for the best. They’re a great way to tap into the collective intelligence of the group for great results!

Remember that the process is often iterative. Great problem solvers often roadtest a viable solution in a measured way to see what works too. While you might not get the right solution on your first try, the methods below help teams land on the most likely to succeed solution while also holding space for improvement.

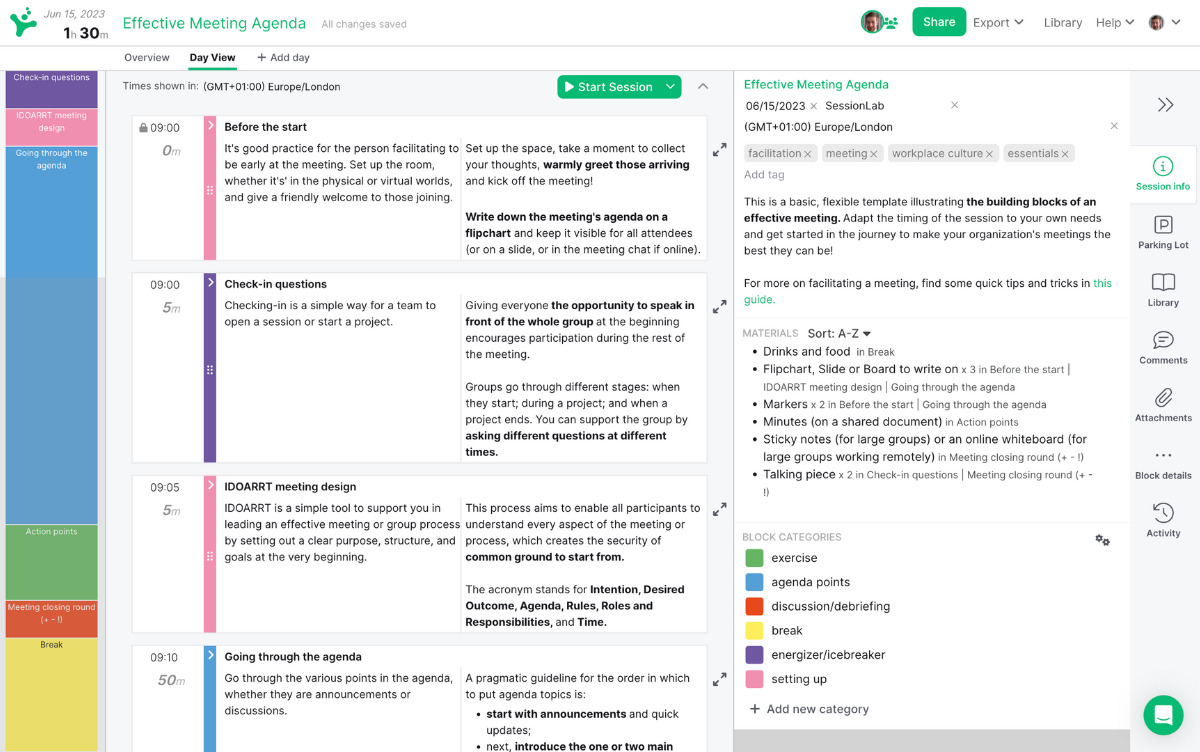

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . A well-structured workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

In SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Tips for more effective problem solving

Problem-solving activities are only one part of the puzzle. While a great method can help unlock your team’s ability to solve problems, without a thoughtful approach and strong facilitation the solutions may not be fit for purpose.

Let’s take a look at some problem-solving tips you can apply to any process to help it be a success!

Clearly define the problem

Jumping straight to solutions can be tempting, though without first clearly articulating a problem, the solution might not be the right one. Many of the problem-solving activities below include sections where the problem is explored and clearly defined before moving on.

This is a vital part of the problem-solving process and taking the time to fully define an issue can save time and effort later. A clear definition helps identify irrelevant information and it also ensures that your team sets off on the right track.

Don’t jump to conclusions

It’s easy for groups to exhibit cognitive bias or have preconceived ideas about both problems and potential solutions. Be sure to back up any problem statements or potential solutions with facts, research, and adequate forethought.

The best techniques ask participants to be methodical and challenge preconceived notions. Make sure you give the group enough time and space to collect relevant information and consider the problem in a new way. By approaching the process with a clear, rational mindset, you’ll often find that better solutions are more forthcoming.

Try different approaches

Problems come in all shapes and sizes and so too should the methods you use to solve them. If you find that one approach isn’t yielding results and your team isn’t finding different solutions, try mixing it up. You’ll be surprised at how using a new creative activity can unblock your team and generate great solutions.

Don’t take it personally

Depending on the nature of your team or organizational problems, it’s easy for conversations to get heated. While it’s good for participants to be engaged in the discussions, ensure that emotions don’t run too high and that blame isn’t thrown around while finding solutions.

You’re all in it together, and even if your team or area is seeing problems, that isn’t necessarily a disparagement of you personally. Using facilitation skills to manage group dynamics is one effective method of helping conversations be more constructive.

Get the right people in the room

Your problem-solving method is often only as effective as the group using it. Getting the right people on the job and managing the number of people present is important too!

If the group is too small, you may not get enough different perspectives to effectively solve a problem. If the group is too large, you can go round and round during the ideation stages.

Creating the right group makeup is also important in ensuring you have the necessary expertise and skillset to both identify and follow up on potential solutions. Carefully consider who to include at each stage to help ensure your problem-solving method is followed and positioned for success.

Document everything

The best solutions can take refinement, iteration, and reflection to come out. Get into a habit of documenting your process in order to keep all the learnings from the session and to allow ideas to mature and develop. Many of the methods below involve the creation of documents or shared resources. Be sure to keep and share these so everyone can benefit from the work done!

Bring a facilitator

Facilitation is all about making group processes easier. With a subject as potentially emotive and important as problem-solving, having an impartial third party in the form of a facilitator can make all the difference in finding great solutions and keeping the process moving. Consider bringing a facilitator to your problem-solving session to get better results and generate meaningful solutions!

Develop your problem-solving skills

It takes time and practice to be an effective problem solver. While some roles or participants might more naturally gravitate towards problem-solving, it can take development and planning to help everyone create better solutions.

You might develop a training program, run a problem-solving workshop or simply ask your team to practice using the techniques below. Check out our post on problem-solving skills to see how you and your group can develop the right mental process and be more resilient to issues too!

Design a great agenda

Workshops are a great format for solving problems. With the right approach, you can focus a group and help them find the solutions to their own problems. But designing a process can be time-consuming and finding the right activities can be difficult.

Check out our workshop planning guide to level-up your agenda design and start running more effective workshops. Need inspiration? Check out templates designed by expert facilitators to help you kickstart your process!

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lightning Decision Jam

- Problem Definition Process

- Discovery & Action Dialogue

Design Sprint 2.0

- Open Space Technology

1. Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

2. Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

3. Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

4. The 5 Whys

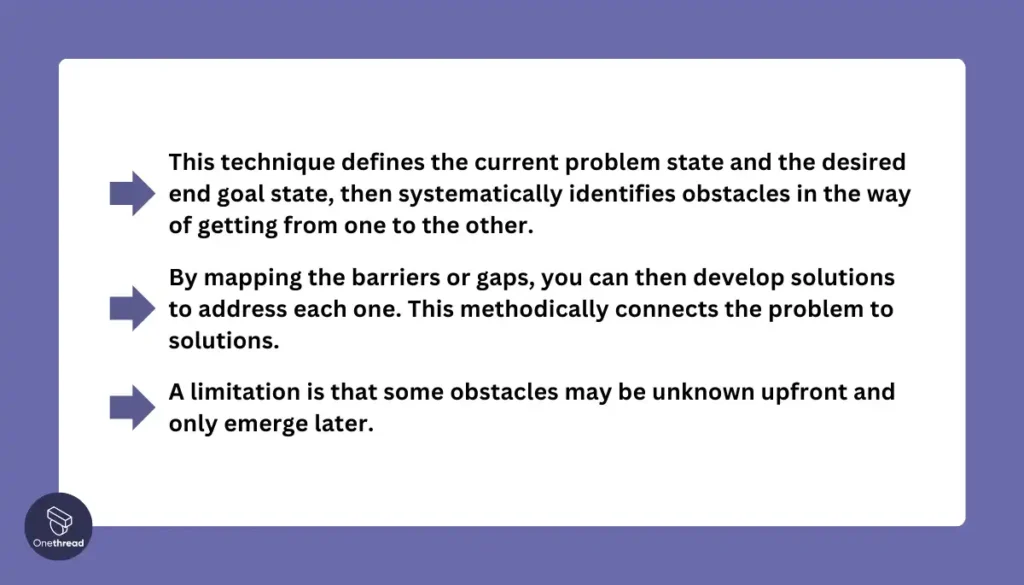

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

5. World Cafe

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

6. Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

7. Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

8. Open space technology

Open space technology- developed by Harrison Owen – creates a space where large groups are invited to take ownership of their problem solving and lead individual sessions. Open space technology is a great format when you have a great deal of expertise and insight in the room and want to allow for different takes and approaches on a particular theme or problem you need to be solved.

Start by bringing your participants together to align around a central theme and focus their efforts. Explain the ground rules to help guide the problem-solving process and then invite members to identify any issue connecting to the central theme that they are interested in and are prepared to take responsibility for.

Once participants have decided on their approach to the core theme, they write their issue on a piece of paper, announce it to the group, pick a session time and place, and post the paper on the wall. As the wall fills up with sessions, the group is then invited to join the sessions that interest them the most and which they can contribute to, then you’re ready to begin!

Everyone joins the problem-solving group they’ve signed up to, record the discussion and if appropriate, findings can then be shared with the rest of the group afterward.

Open Space Technology #action plan #idea generation #problem solving #issue analysis #large group #online #remote-friendly Open Space is a methodology for large groups to create their agenda discerning important topics for discussion, suitable for conferences, community gatherings and whole system facilitation

Techniques to identify and analyze problems

Using a problem-solving method to help a team identify and analyze a problem can be a quick and effective addition to any workshop or meeting.

While further actions are always necessary, you can generate momentum and alignment easily, and these activities are a great place to get started.

We’ve put together this list of techniques to help you and your team with problem identification, analysis, and discussion that sets the foundation for developing effective solutions.

Let’s take a look!

- The Creativity Dice

- Fishbone Analysis

- Problem Tree

- SWOT Analysis

- Agreement-Certainty Matrix

- The Journalistic Six

- LEGO Challenge

- What, So What, Now What?

- Journalists

Individual and group perspectives are incredibly important, but what happens if people are set in their minds and need a change of perspective in order to approach a problem more effectively?

Flip It is a method we love because it is both simple to understand and run, and allows groups to understand how their perspectives and biases are formed.