What is solutions journalism and why should you care?

By solutions journalism network jun 14, 2022 in specialized topics.

Solutions journalism investigates and explains, in a critical and clear-eyed way, how people try to solve widely shared problems. While journalists usually define news as “what’s gone wrong,” solutions journalism tries to expand that definition: responses to problems are also newsworthy. By adding rigorous coverage of solutions, journalists can tell the whole story.

Solutions journalism complements and strengthens coverage of problems. Journalists are often frustrated when painstaking investigations of a problem don’t produce change. We expose our city’s failures to save children from lead paint, or to protect high school football players from concussions, or to recover from the closing of a major factory — but, too often, officials simply dismiss these investigations, saying “we’re doing the best we can.”

Now add solutions journalism to the investigation, showing how other cities are solving these problems. That’s profoundly embarrassing to public officials. Excuses won’t cut it. Change happens.

Solutions stories don’t celebrate responses to problems, or advocate for specific ones; they cover them, investigating what was done and what the evidence says worked and didn’t work about it, and why. They report on the limitations of a response.

These stories often start with data showing which places are doing a better job. They’re often structured like puzzles or mysteries that tackle questions like: Where is the high-school dropout rate decreasing? How and why is that happening? What is the school or district or state doing differently that’s leading to a better outcome?

Journalists usually choose to report on successful solutions. But a solutions story can also be about partial success, or failure. If our city is about to launch a new initiative, a solutions story might look at how that program has fared elsewhere: where did it work or not work? What made the difference?

Done well, solutions stories provide valuable insights that help communities with the difficult work of tackling problems like homelessness or climate change, skyrocketing housing prices or low voter turnout. We also know from research that solutions stories can change the tone of public discourse , making it less divisive and more constructive . By revealing what has worked, such stories have led to meaningful change.

The four pillars of solutions journalism

- A solutions story focuses on a response to a social problem — and how that response has worked or why it hasn’t.

- The best solutions reporting distills the lessons that makes the response relevant and accessible to others. In other words, it offers insight .

- Solutions journalism looks for evidence — data or qualitative results that show effectiveness (or lack thereof). Solutions stories are up front with audiences about that evidence — what it tells us and what it doesn’t. A particularly innovative response can be a good story even without much evidence — but the reporter has to be transparent about the lack, and about why the response is newsworthy anyway.

- Solutions stories reveal a response’s shortcomings. No response is perfect, and some work well for one community but may fail in others. A responsible reporter covers what doesn’t work about it, and places the response in context. Reporting on limitations , in other words, is essential.

Examples of standout English-language solutions reporting

Visit the Solutions Journalism Story Tracker collection for more examples of solutions reporting.

This article was originally published by the Solutions Journalism Network and is reproduced here with permission.

Photo by Daniele Franchi on Unsplash .

IJNet provides the latest tips, trends and training opportunities in eight languages . Sign up here for our weekly newsletter:

International Symposium on Online Journalism

A program of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at the University of Texas at Austin

- Search for:

Journalists’ perceptions of solutions journalism and its place in the field

By Kyser Lough and Karen McIntyre

This paper uses in-depth interviews with 14 journalists to better understand the position of solutions journalism—rigorous reporting on how people are responding to social problems—in the field and in journalistic habits. We found that journalists familiar with solutions journalism accept and align it with investigative reporting, but with the extra step toward social response. They think it’s broadly topical, but has the same objectivity concerns journalism is facing. When taking a solutions approach, journalists shift their thought processes but largely maintain the same reporting habits. Finally, they perceive management to be the greatest facilitator or impediment to their ability to adopt solutions journalism.

The nature of journalism is ever-shifting, with trends and themes coming in and out of favor as the institution continues to elaborate on what it means to do reporting. Some themes take hold in the minds of journalists and are adopted into their daily news reporting habits and, subsequently, into the research topics of academics. One such practice is solutions journalism, which is “rigorous reporting on responses to social problems” (Solutions Journalism Network, 2017, n.p.). This type of reporting fits into the contextual function of journalism, which seeks to add information beyond the immediate issue at hand, or to go beyond the “who, what, when, where” that often defines the problem, and focus on “What are people doing about it?” (McIntyre, Dahmen & Abdenour, 2016).

Solution-based reporting is gaining momentum in the industry. A recent survey of U.S. journalists indicated support for contextual journalism functions, including solution-oriented journalism (McIntyre et al., 2016). After learning about solutions journalism, respondents reported favorable attitudes toward it and said they would be most likely to practice this approach compared to other contextual genres (McIntyre et al., 2016). Further, more than 3,000 journalists have received formal training in solutions journalism (Solutions Journalism Network, 2017). And educators are beginning to teach it, seeing interest among millennials striving to make an impact (Loizzo, Watson & Watson, 2017; Solutions Journalism Network, 2017; Thier, 2016).

This type of reporting, by its very nature requiring journalists to consider the impact of their work, has brought to the forefront debate about the role journalists play in a democratic society. Solution-oriented reporting pushes journalists to think about the social responsibility of the press and question whether they consider society’s best interest in their daily thought processes and habits. However, research has yet to examine how journalists feel about this style of reporting. To address this gap, this study, through 14 in-depth interviews, asked journalists familiar with the solutions approach how they perceive this style of reporting and how incorporating this approach has altered their traditional journalistic thoughts and news production habits.

Theoretical Framework

Solutions Journalism

Solutions journalism can be considered to fit into the contextual function of journalism, a more thorough type of journalism that has also been referred to as “interpretative reporting, depth reporting, long-form journalism, explanatory reporting, and analytical reporting” (Fink & Schudson, 2014, p. 5). Drilling down, solutions journalism can also be situated within a similar, but more specific category called constructive journalism, which “involves applying positive psychology techniques to news work in an effort to create more productive, engaging stories while holding true to journalism’s core functions” (McIntyre, 2015, p. 9). McIntyre (2015) describes constructive journalism as a “continuum” and not a dichotomy. This shifts the focus from the “versus” style of reporting (peace vs. conflict, oppressor vs. oppressed) back to an emphasis on comprehensive investigative reporting with an intent to better society.

This study focuses on the solutions journalism component of constructive journalism. However, it is important to acknowledge that there are other forms of journalism that share similar goals, including peace journalism, civic journalism, restorative narrative, and advocacy journalism. Peace journalism promotes peace initiatives versus a perceived media bias toward violence (Yiping, 2011) and focuses heavily on war/peace conflict coverage (Kempf, 2007). Civic journalism promotes democratic participation by giving journalists direct involvement with the population they serve instead of staying a separate entity (Benesch, 1998). Restorative narrative encourages coverage of the recovery and restoration process long after large-impact tragedies (Dahmen, 2016). And advocacy journalism, with its public relations implications, maintains no goal of objectivity and “remains a dirty word for legacy journalists” (Wenzel, Gerson, Moreno, Son, & Morrison Hawkins, 2017, p. 4). Additional similar forms of journalism exist. Although each is distinct, they share a common goal of improving society, which requires the journalist to play a more active role in reporting the story (McIntyre, 2015).

Solutions journalism has a growing appeal in the professional world for its principle of addressing what’s being done to solve a problem rather than reporting solely on the problem itself (Curry, Stroud & McGregor, 2016). The approach has been most clearly defined by the Solutions Journalism Network, an independent nonprofit organization founded in 2013. The Solutions Journalism Network has hosted trainings for journalists in more than 80 newsrooms on how to effectively report solution-focused stories. In reporting on responses to social problems, they call for stories to include specific elements such as evidence of results, insights that can help others, and limitations of the response (Solutions Journalism Network, 2017). These elements, the Network says, are vital to ensuring stories remain comprehensive and critical rather than appear as “fluff” or “good news.”

Still, solutions journalism, or the broader category of constructive journalism, tends to be mistaken for “positive” or “good” news (Sillesen, 2014). Constructive journalism, one opponent said, is only good “if you want a sleepy, complacent society, not if you want active, engaged citizens” (Tullis, 2014 para. 14). However, proponents of solutions journalism would say the approach is just as hard-hitting and questioning as traditional journalism. David Bornstein, CEO and co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, says criticisms of solutions journalism mostly come from people who misunderstand the practice (personal communication, November 30, 2017). That said, Bornstein did acknowledge some limitations of solution-focused news. He said reporters can misapply it by spotlighting people who don’t deserve it or by focusing on do-gooders instead of on ideas or methods. He also said the approach could be overused and thus lose its relevance (personal communication, November 30, 2017).

Despite its growing popularity in the industry, solutions journalism has only been recently explored in academic research. In a systematic, but unpublished, study of solutions journalism, respondents who read solution-oriented stories reported more perceived knowledge about the topic, higher self-efficacy in regard to a potential remedy, and greater intentions to act in support of the cause than those who read conflict-oriented versions of the stories (Curry & Hammonds, 2014). A true experiment comparing a solution-oriented and conflict-oriented news story found that mentioning an effective solution to a social problem in a news story caused readers to feel less negative and to report more favorable attitudes toward the news article and toward solutions to the problem than when no solution or an ineffective solution was mentioned. However, reading about an effective solution did not impact readers’ behavioral intentions or actual behaviors (McIntyre, 2017). Another experiment comparing solutions journalism to shock media found that solutions stories had some, but not overwhelming, benefits over shocking stories (McIntyre & Sobel, 2017a).

Additional studies have examined the photographs published alongside solutions journalism stories. One study found 64% of photos published with solutions stories portrayed a solution, while many of the remaining photos portrayed a conflict (Lough & McIntyre, in press). A follow-up study examined the effects on readers when the message in the photo was incongruent with the message in the text. Readers felt the most positive when the story and photo were congruent, when both represented a solution. However, surprisingly, readers reported more interest in the story and stronger intentions to share the story on social media when the solutions story was paired with a neutral photo (McIntyre, Lough & Manzanares, in press).

Finally, Thier (2016) published a study about solutions journalism pedagogy, concluding that solutions journalism courses inspire students and faculty, and that teaching this approach “is important as disruption continues and need increases to find effective journalism practices” (p. 329). Additionally, students in a Journalism for Social Change Massive Open Online Course self-reported more interested in solutions journalism stories but found them harder to produce (Loizzo, Watson & Watson, 2017).

In his conceptualization of framing, Robert Entman revealed how the field of communication contributes to how information is transferred. While his definition connects to the overall goals of journalism, specific portions align clearly with the goals of solutions journalism:

To select some aspects of perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text , in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation. (Entman, 1993, p. 52, emphasis added)

Solution-related frames have been used as points of analysis in journalism studies (see Adisi, Mohammed, & Ahmad, 2015; Kensicki, 2004; Kim, Carvalho, Davis, & Mullins, 2011). In the definition above, two phrases are emphasized that play particularly well into the ideals of solutions journalism: treatment recommendations and salience.

First, the treatment recommendation. In solutions journalism, the goal of the reporter is to go beyond the problem and find existing treatments (not to generate the ideas him/herself). This is done by critically exploring what those in the public are doing in response to a problem. As mentioned above, research shows how the audience responds to this type of reporting, but there is little understanding of what journalists think about this particular emphasis on treatments/solutions.

Second, Entman’s emphasis on salience ties into the journalistic function of taking the news and disseminating it to the public. Solutions journalism asks the journalist to make the response more salient than it may ordinarily be. By reporting on the response(s), the reporter thereby increases the “probability that receivers will perceive the information, discern meaning and thus process it, and store it in memory” (Entman, 1993 p. 53). But again, while the transfer of salience to the reader is understood, less is known about how the journalists themselves position this process in their daily journalistic thought processes and news production habits.

Another key solutions-related point in the Entman (1993) framing explanation is that the problem definition is included. Indeed, before one can explore the responses in progress one must first clearly understand and explain the problem. Constructive journalism (and its solution-oriented component), again, is not a dichotomy, but a continuum (McIntyre, 2015), and so it is important to provide the full context versus simply only focusing on problem or solution. Therefore, it is important to know how journalists feel about an emphasis on solutions, the transfer of salience to the reader and the problem-solution continuum in a story itself. However, it is also important to understand how these thought processes of solutions journalism are put into practice, and so we must turn to the intersection of thought and the actual news production habits of journalists.

Journalists’ Production Habits

Shoemaker and Reese’s (2013) hierarchy of influences identifies various levels for analysis affecting news production ranging from the individual to institutional systems. Solutions journalism can exist on many of the levels of the hierarchy, which are explored below. Nestled in the hierarchy, one step broader than the individual, is a level focusing on routines, or news production habits. The routines level asks questions of the shared practices of the individual journalists and includes a variety of aspects such as news values and objectivity.

Objectivity has a controversial history in journalism and continues to be debated (Blaagaard, 2013; Ryan, 2001; Wien, 2005). It cannot be untethered from some of the core concepts underpinning the institution, like truth and reality (Wien, 2005). The idea that journalists strive to report the objective truth legitimizes and distinguishes professional journalists from those who don’t share the same commitment. However, Blaagaard (2013) said that niche forms of journalism such as public journalism and citizen journalism—some of which share qualities with solutions journalism—threaten objective reporting “by situating the journalist amidst the society and the story” rather than believing in “the journalist’s objective ability to represent the world ‘as it is’ without affecting it” (p. 1078). Of course, media sociologists would argue that objectivity in its purest form is not possible because journalists are part of society and therefore unable to rid themselves of their own experiences, perceptions and biases (Berkowitz, 1997). This perspective does not de-legitimize journalists, however. Rather, it accepts objectivity as a goal to strive for so long as journalists acknowledge their own limitations. One journalism professor said he wonders if solutions journalism compromises objectivity because reporters “approach a story with the goal of proving that a specific solution is valid” (Dyer, 2015, n.p.). Media scholar Ethan Zuckerman said solutions journalists should stop trying to be strictly objective and that “purposefully motivating readers to act on the issues raised in stories is perfectly respectable—indeed, necessary” (Dyer, 2015, n.p.).

Høyer (2005) presented the news paradigm as a collection of cultural forms surrounding news production habits and how journalists define what’s newsworthy and subsequently report on it. While not attempting to insert solutions journalism as an additional news value or narrative structure into Høyer’s list, it is logical to conclude the practice itself may find a home for analysis at this level.

Past the routines, journalists also identify with certain roles that can play out on the same level. Examples include: the adversary, who is skeptical of government, big business and others in power; the disseminator, who neutrally passes information to the public; the interpreter, who analyzes and interprets information for the public; and the populist mobilizer, who takes a more activist role (Weaver, Beam, Brownlee, Voakes & Wilhoit, 2014). Through study of U.S. journalists, McIntyre, Dahmen and Abdenour (2016) proposed a new role: the contextualist. This role includes a function of social responsibility, where the journalist goes beyond basic information to include context, while considering the well-being of society. The contextualist highly values portraying the world accurately by reporting stories of growth and progress as much as those about corruption and conflict.

While little has been explored academically into routines-level analysis of solutions journalism, some insight exists. The aforementioned survey of U.S. journalists indicated support for a solution-oriented approach and connected various levels of news value and action to the practice (McIntyre et al., 2016). Further, a qualitative study of Rwandan journalists found how solutions and constructive journalism played a role in the press’ role in reconstruction and recovery after the 1994 government-led genocide (McIntyre & Sobel, 2017b). This provides some knowledge into how the thought processes of journalists played into news production habits but leaves room for further exploration.

After defining and positioning solutions journalism within the practice of journalism, exploring it theoretically through framing and at the level of production through the hierarchy of influences, there is still little known about the thought processes of journalists regarding solutions journalism. Thus, the following question is proposed:

RQ1: What do journalists’ perceptions of solutions journalism reveal about its place within journalism itself and within their news production habits?

Prior research on solutions journalism has focused on the audience, with slight attention paid to the journalists themselves. That which has targeted journalists (McIntyre, Dahmen & Abdenour, 2016) has done little to focus specifically on those practicing, or at least aware of, solutions journalism and what they think about it. Thus, the ideal method to gain this is through in-depth interviews that allow the participants to offer description on their thoughts and routines surrounding solutions journalism. In-depth, qualitative interviews allow for a richer understanding of a group through open-ended questions and discussion with participants with the goal of learning from people rather than studying them, ultimately developing contextual research that matters (Spradley, 1979; Tracy, 2013). The target demographic for this study therefore included journalists who were, to some extent, aware of a solution-oriented method of reporting. Contributions from journalists who are not familiar with solutions journalism would only add confusion and perpetuate misconceptions about the practice. To that end, the Solutions Journalism Network served as a useful source for recruiting participants.

In an effort to collect information from those knowledgeable enough to offer insight, subjects were recruited from the Solution Journalism Network’s database of journalists interested in, and/or trained in, solutions journalism. This ensured awareness of the practice without necessarily seeking a particular level of involvement or support. The Solutions Journalism Network has its own list of values and practices, and this paper would contribute nothing if it only contained regurgitations from the organization’s teachings. The authors sought original insight from those who had been incorporating it into their reporting habits. Additionally, it was made clear to each participant that the researchers were unaffiliated with the Solutions Journalism Network, the study was independent and not seeking to promote the practice, and to therefore speak freely.

Under IRB review and approval, participants were recruited via an email sent by staff at the Solutions Journalism Network to members in their network, called The Hub. At the time of recruitment, the database contained 1,568 self-identified journalists from across the world (S. McCann, personal communication, September 19, 2017), and no geographic restrictions were imposed. The email connected the participants to the researchers, who then scheduled voice interviews via phone or Skype.

From the recruitment email, 25 journalists responded with initial interest, and 14 followed through with an interview. All interviews took place in July and August 2017. The participants were an experienced, educated and diverse group. Together they reported an average of 19.5 years working in the news industry as writers, reporters and editors. One individual was a journalism professor. These journalists worked at various organizations, including small, independent local newsrooms as well as large corporations. Half the sample did freelance work. Most worked in the United States (in eight different states), except for two in India and one in Sweden. They were 43% female and 57% male. All of the journalists reported having earned a bachelor’s degree, and 50% said they held advanced degrees. Six individuals studied journalism as their highest degree; the others earned their highest degree in English, history, psychology, African studies, environmental science, law or education policy.

The semi-structured interviews consisted of questions involving their thoughts on solutions journalism, personal experiences with it and how it fits into journalistic routines, with flexibility for follow-up questions. Some questions were direct, asking them exactly how they feel about solutions journalism, to gauge their opinion. The rest of the interview was devoted to questions that dealt with how they conceptualize solutions journalism and how it actually fit into their day-to-day reporting. Did they use it? If so, under what circumstances? What were the barriers and facilitators to solution-oriented reporting? Interviewees were asked to provide examples and discuss their internal process of creating such a story and how that process differed, if at all, from their traditional reporting process.

Each interview ran for approximately 30 minutes, with the longest lasting one hour. Interviews were audio recorded, and the resulting 467 minutes of audio were transcribed. The researchers read the transcript text, searching for themes, and further analyzed the data using Dedoose, a collaborative software program which assists researchers in qualitative text analysis (Lieber & Weisner, 2013). The researchers applied 17 codes, or themes, to the data 286 times. The analysis by the researchers combined with the aid of computer software allowed for the data to be organized into categories and structured effectively while maintaining the nuance in interpreting the interview conversations.

Analysis of the interviews resulted in a better understanding of how journalists position solutions journalism within journalism itself and within their news production habits. Broadly, it was regarded as an intriguing and growing method of reporting that has obstacles but is a worthwhile pursuit. More specifically, several key findings emerged. Journalists revealed that they position solutions journalism close to investigative journalism. They believe it to be broadly applicable to topics but still complicated when it comes to objectivity. Additionally, the data revealed that journalists approach solutions stories with a different mindset than they approach traditional stories, and they feel that the success of the solutions journalism approach relies on support from management.

Solutions Journalism as a Concept

While it was expected for journalists in this sample to have a positive opinion of solutions journalism, our goal was to draw out details as to where they place it within the institution of journalism, the broader ring of the hierarchy of influences. To that end, their responses helped explain where solutions journalism is situated, what topics are well-suited for solution-oriented reporting and how they think solutions journalism affects the audience.

Situating solutions journalism in the field.

Journalists overwhelmingly compared solutions journalism to investigative journalism. In their minds, solutions reporting parallels investigative reporting in its rigorous nature of deep research into the topic and in its goal of uncovering something. Indeed, this thought mirrors the mission of The Catalyst Journalism Project, a recent initiative based at the University of Oregon, which seeks to bring together investigative and solutions reporting (University of Oregon, 2017). However, these journalists did not believe solutions and investigative journalism were completely similar. Some spoke of solutions journalism as an extension of investigative reporting, or investigative journalism with an extra step. As Journalist B, a reporter for an online local news site in Ohio, described it, “normally, journalists do not take that extra step … to present what other solutions are out there … I think [solutions journalism is] that final, extra step where you say, ‘Here’s something that could work here’” (personal communication, July 9, 2017). While the traditional five Ws of reporting include who, what, when, where and why, a sixth W of “what’s next?” was a common theme in the responses, along with additional emphasis on “why?” and “how?” Journalist K, a freelancer in India, called investigative reporting the watchdog to identify the problems and solutions journalism reporting the guide dog to look at possible solutions. This calls to mind Bro’s (2008) news compass and comparisons between passive, representative watchdog reporting and active, deliberative rescue dog reporting that seeks to “ensure solutions to the problems the news media help bring forward” (p. 316).

I’ve always embraced investigative journalism, and uncovering, and watchdog journalism, but a lot of times I’ll see a piece or read a piece and go, “Okay so, what?” … Not, “What are we supposed to do about it?” We know we’re supposed to fix it, but who’s got an answer for it? (Journalist K, personal communication, August 22, 2017)

While advocacy journalism came up a few times, most journalists used it as an example of what solutions journalism isn’t. “It’s a little troubling to me the idea that I would write a story that says ‘this is a great solution to the problem,’” said Journalist A, a journalism professor in New York, emphasizing that solutions journalism “is not a story about me and what I think. It’s still a story about what’s happening on the ground” (personal communication, August 17, 2017). This aligns with the objectivity messaging of the Solutions Journalism Network and its avoidance of advocating toward a particular solution. However, this stance was not clear to all journalists, as some embraced solutions journalism because of the advocacy elements they felt it would bring their reporting. Journalist G , a news editor at a large corporation in Philadelphia , said: “You might as well advocate for something, right? … Looking for a solution is being an activist” (personal communication, August 17, 2017).

Multiple solutions journalism “imposters” defined by the Solutions Journalism Network were mentioned by participants, notably including stories about speculation, hero worship and a public relations-style favor for a friend. Additionally, Journalist M, the managing editor for a collaborative public media venture in New York, cautioned that it is easy to get excited about solutions journalism and “then just for the sake of covering a solutions angle, you cover something that isn’t really much of a solution and you trumpet this thing that is kind of B.S. or a hoax or whatever” (personal communication, July 24, 2017).

From the participants’ efforts at positioning solutions journalism within the institution of journalism, it appears they think it aligns with the rigorousness of investigative reporting, with the additional step of seeking out what solutions exist for the problem uncovered, or the sixth W—“What’s next?” However, the differing opinions of objectivity showed that practitioners have not yet reached a consensus on solution journalism’s placement in the larger field.

Solutions journalism’s applicability to specific topics.

The positioning of solutions journalism became clearer when talking to the participants about when the practice is best used. In their responses of what topics or areas of coverage they think are best suited for solutions journalism, they continued to position it within the broader field of journalism.

Overall, participants felt that solutions journalism is fairly topic-agnostic. Several journalists who were interviewed reported on specific beats, such as education or business, and said it was possible in their areas. Notably, as one participant spoke about a previous job as an example of where solutions journalism wouldn’t fit, she realized mid-sentence how it would.

I used to work for a major national newspaper that had a big focus on business and finance and it’s hard for me to think about what the solutions approach would be to reporting about the banking industry—and yet even as I’m saying that I’m realizing people who are in industry are constantly thinking about solutions and problem-solving. (Journalist A, personal communication, August 17, 2017)

Though the participants felt that all topics had a potential to be reported on with a solutions focus, there was thought that some topics are more inclined than others. For example, Journalist C, a freelancer and editor for a U.K.-based narrative design studio that helps people tell stories, said it depends on the complexity of the problem (personal communication, July 19, 2017). Others identified specific topics that they thought were better suited. Journalist F, a multimedia broadcast journalist and freelancer in Virginia, said the solutions approach helps to address social and human rights issues specific to Pakistan (where she formerly worked) but also globally (personal communication, August 24, 2017). Only a few spoke strongly about how some topics are best suited for solutions journalism, and universally those topics were issues of human rights, social justice or the environment. While solutions journalism could be applied to most topics, the participants indicated they thought there are times it isn’t practical. This is especially noted in cases of breaking news and what Journalist B, a reporter for an online local news site in Ohio, described as her daily reporting tasks (personal communication, July 9, 2017). The broad topic applicability responses from participants support Entman’s (1993) definition of framing, which also does not take a specific stance on topics or types either and places focus on how the ideas are presented. While some topics may be better suited for solutions journalism than others, the participants believe it’s a method that can apply to all areas of journalism.

Positioning the purpose of solutions journalism.

The positioning of solutions journalism matters little unless the journalists can also position its connection to the audience as well. Participants frequently brought up audience impact and engagement as a way of justifying, supporting and positioning the purpose of solutions journalism. The participants related solutions journalism to current issues of media trust and audience perceptions, saying that they think it has the potential to rebuild lost credibility and interest from their readers, viewers or listeners.

One thing that really struck me and frustrated me while I was in school was that my teachers told us all the time, and my teachers were all working or formerly working journalists, and they’re all like, “People aren’t reading newspapers. It’s harder to get a job. People don’t trust the media.” … If you’re writing with an eye towards solutions, I think it’s much more engaging. The reader can say, “God, that sucks, and what can I do about it,” and the story answers that question. (Journalist G, personal communication, August 17, 2017)

As the participants discussed media trust and how they think solutions journalism plays a role in the future of journalism, questions of objectivity began to emerge. Journalist G, the Philadelphia-based news editor, went on to blur the line between reporting on a solution and taking a stance. Objectivity itself came up a number of times outside of direct questioning by the interviewers, which is a topic that will be explored more thoroughly below as it relates to practice. However, it is important to note that objectivity came up as a blurry area when participants attempted to position solutions journalism within the institution of journalism. This is not unlike how objectivity itself is frequently challenged as a tenet of journalism (Maras, 2013) and shows that threads of opinion run deep, even into other practices of reporting.

In summary, by asking journalists what they think about solutions journalism as it relates to journalism as a whole, three themes emerged that help show how they position the practice. First, they think it is similar to investigative reporting but with an added step of looking for existing solutions. Second, they find it appealing for a broad range of topics but think certain topics are more suited. Finally, they think it has a role in shaping the future of journalism in rebuilding audience interest and trust, though objectivity still can be a gray area.

News Production Habits of Solutions Journalists

The positioning of solutions journalism within the institution is important, but the researchers also set out to see just how these thoughts influence the production habits of the journalists. To that end, the second half of the interview focused on real-life experience with solutions journalism and how their thoughts connected to journalistic habit. Several themes emerged from these conversations, including further considerations of objectivity, how solutions journalism alters existing routines, and what facilitates and impedes journalists’ ability to report using a solutions-based approach. These themes aligned with three levels of the hierarchy of influences (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013), mainly institutional, individual and organizational, respectively, and showed how each has an influence on the ability to practice solutions journalism.

Solutions journalism’s relationship with objectivity.

While most journalists think there is a clear line between advocacy journalism and solutions journalism, the institutional journalistic tenet of objectivity still creates complication in the understanding and practice of solutions journalism. When connecting solutions journalism to practice, participants mostly positioned it away from advocacy journalism or opinion—something the Solutions Journalism Network does in its literature. As referenced above, however, Journalist G had a hard time separating advocacy, at one point saying “you might as well advocate for something, right?” (personal communication, August 17, 2017).

To reconcile the differences, journalists spoke at institutional levels of examples, positioning their work against the tenets of journalism and how they were trained (even if they didn’t have a journalism degree).

Objectivity is very important. I don’t have formal journalistic training but yeah, I’m aware of that much. I think that without objectivity you don’t have journalism whether it’s solutions or not. (Journalist C, personal communication, July 19, 2017)

In bringing their own experience and practices into the picture, they said they think the best way to combat the risks of slipping into opinionating is also through the institutional tenets of journalism. When pressed for specifics past just “remaining balanced,” participants brought up tasks such as rigorous reporting and making sure any claims are made through evidence of data. Journalist A (the journalism professor), in particular, compared advocacy journalism to a “monologue with itself about what is right and wrong” and solutions journalism as a “conversation with the full complexity of the problem,” backed by deep sources and data (personal communication, August 17, 2017).

Of course, in practice it’s not always so easy. Journalist B, the reporter in Ohio, recounted a story where a problem in the community was identified, a solution in other communities was found and reported on, and then suddenly the publisher decided the media outlet should have a hand in implementing the solution in the community (personal communication, July 19, 2017). The reporting worked so well that the publisher him/herself was sold. However, the journalist noted the ethical dilemma of being involved in the implementation, since she wanted to remain objective. While the journalist became known as the person responsible for bringing the solution to the area, she said she avoided much of the public relations aspects of it, such as stepping out of a group photo when the program launched. Even though the media organization decided to pivot toward taking a more active role, the journalist still felt institutional pressure to keep objectivity a priority.

Same habits, revised thought process.

Looking closer at the actual practice of solutions journalism, participants were asked about their processes and habits of reporting and whether it takes a shift at the individual level to report with a focus on solutions. Here, a key finding emerges—it all came down to the thought process. While some participants talked about tangible routine changes, they all generally did things the same—sought sources, data, and information and synthesized it in a critical and questioning way. The questions were geared toward tangible process change yet it was the thought process itself that guided the individual and distinguished solutions reporting from conventional reporting.

In particular, participants said they think more about the “how” of a topic when covering it from a solutions approach. This came into play when discussing how solutions journalism takes the extra step from investigative reporting; participants said they don’t stop at the issue but instead think about how to find what the solutions are. Journalist L, a coordinator for an Oregon chapter of the Solutions Journalism Network, said by having the right mindset going into a story, one can ask the right questions of the sources to start to see where the solutions may lie (personal communication, July 18, 2017).

Journalist B described a tangible process that differed from her typical reporting routine, but even that turned out to be heavily thought-based. To handle the complexity of thought necessary to plan out a solutions story, the journalist uses a mapping exercise to organize her thoughts.

I always take a huge sheet of paper, and I story board it out … It always helps me because if it’s something I know is gonna be deeply investigated, and has a lot of sources, and has a lot of ideas. It helps me, number one to map everything out, to say like, “Okay, here’s the problem, here’s the solution, and then everything in between.” (personal communication, July 19, 2017)

While tangible news production habit changes were mentioned by some, the overwhelming shift at the individual level took place in the mind. Journalists started with a thought process shift toward the “how” of a solution, looking past the issue itself and beginning to understand how to ask questions, seek sources and obtain data. Even when their routines did change tangibly, such as the mapping example above or how some participants said they would need to travel to the other cities where the solutions were taking place, their process always started with a shift in thought.

Support among management.

The final questions asked to the participants dealt with what facilitates and impedes their ability to practice solutions journalism. As the sample included a range of journalists, from freelancers who have to pitch stories to staff reporters who might be assigned stories, answers varied but did settle on one key factor: management. Endorsement by the organization, whether it be an editor, publisher or supervisor, was key to facilitating or impeding the journalists’ ability to report on solutions. This connects heavily to the organizational level of the hierarchy of influences, and supports the model in showing just how influential the organization can be. This was seen in two ways: support and resources.

Support from the organization’s management played a key role in how the journalists said they were able to conduct solutions-based reporting. Several mentioned difficulty pitching their story ideas unless their editor saw solutions journalism as a worthwhile and legitimate pursuit. This can make it harder for the journalist, as they not only have to go through a traditional pitch but also must inform and convince the editor about the value of a solutions approach. Journalist G, a news editor at a large corporation who also does freelance work, said she considers herself lucky to work with open-minded editors that allow her to follow the story as she thinks it should go (personal communication, August 17, 2017). Audience interest in solutions can also serve as a facilitator, as Journalist I, a Colorado-based technical writer, mentioned.

What facilitates doing this? I would say the support of management for sure, the support of the editors, and even maybe the support of the community. Because if the audience, the readers, the community, does express interest in this kind of work, then maybe there’s more reason for the news organization to support that and set aside time for that. (personal communication, August 25, 2017)

On the freelance side, Journalist J said she takes care to investigate the media outlets in India that she pitches to in order to make sure they are organizationally-aligned with the concept of solutions reporting (personal communication, July 21, 2017). This is not something new, as many freelance journalists will craft a pitch to shape the scope of what an outlet is looking for. But it does show similar organizational ties and pressures for making sure a solutions story can be carried out.

However, some participants said they had no trouble getting a solutions story past the editor’s desk as long as the story was done well.

I’ve never had a solutions pitch rejected because it was a solutions story. I haven’t had any negative experiences in that regard personally, but I can believe that it happens. I can picture some old school newspaper editor in my head going, “No, let’s get the bad guys,” kind of thing, but it’s not something that I have any experience [with] negatively. On the contrary, the people that I’ve pitched stories to have generally been pretty positive about the concept. (Journalist C, personal communication, July 19, 2017)

While it’s important to have the support of management, journalists also mentioned other practical resource barriers. Several participants mentioned shrinking newsrooms and shrinking resources as an impediment to solutions journalism. They described it as something still seen as a specialty practice that can only be added once the core reporting work is done, almost as an elective if there is enough time. As funding shrinks, it becomes harder to justify sending a journalist to another city to report on a solution. This, too, goes back to the organization as money may follow the priorities, and if solutions journalism is not a priority then it won’t receive the funding.

Overall, journalists described organizational support as a key component of facilitating solutions-based reporting. It’s not enough for the journalists themselves to think of solutions journalism as a worthwhile pursuit, it takes management having the same thoughts. While having an editor or publisher not on board may not completely block the practice, it certainly creates an obstacle the journalist must overcome.

In summary, by asking journalists what they think about solutions journalism as it relates to their production habits, three themes emerged that help show how thought translates to action. First, at the institutional level, we see that objectivity tenets still create some complication, similar to what Shoemaker and Reese (2013) saw in the outer levels of the hierarchy of influences. Journalists still perform paradigm repair in defending the institution of journalism, even in describing sub-levels of the field. Second, at the individual level, we see how the routines and processes of journalists change primarily at the thought level, in how they plan out coverage and shift their thinking in the questions they ask. The process of framing a solution requires more than just a style of writing, it also takes re-thinking the story and how the reporter will approach it. Finally, at the organizational level we see how critical support from management is in facilitating the practice. In order to raise a solution’s salience, the story must make it to publication, which requires managerial support. The organizational level of the hierarchy of influences describes how often the bottom line impacts how coverage can be carried out, and we see how journalists sometimes find it even harder to pitch stories when they don’t match what the management might see as a necessary pursuit.

This study set out to understand journalists’ thoughts about solutions journalism and how those impressions position it within the institution of journalism and within their news production habits. From our findings, we see that journalists feel excitement about solutions journalism and liken it to investigative reporting but with an extra step. They think most topics are suited for a solutions approach, but those with less complexity are more conducive, as well as topics relating to social issues. Objectivity is still a challenge, as it is in journalism itself, but journalists think it can be addressed through rigorous reporting and strong supporting evidence. In their news production habits, journalists shift their thought processes first, and let that guide their routines while working on a solutions story. Finally, it takes more than just the journalist to facilitate the process: management must be on board and commit the resources necessary.

While the interview pool remained small, saturation in the key findings was found, eliminating the need for additional interviews. Future research should seek to expand this pool, though, in order to attempt to gain deeper insight into some of the findings. Additionally, the fact that the participants were members of the Solutions Journalism Network Hub might mean they were more supportive of the practice than a representative sample of journalists would be. However, as discussed, it was necessary to recruit journalists familiar with solutions journalism, and our recruitment method served that purpose. Interviewing journalists unfamiliar with the practice would not advance its conceptualization and would likely further muddy the concept. Finally, while our study did seek global representation, future work could target specific countries versus a whole-world approach, to be able to compare nations and seek out culture-specific nuances as other comparative journalism studies have done (e.g. Hanitzch et al., 2011; Schmitz Weiss, 2015).

This research extends our knowledge of solutions journalism by turning to the journalists themselves. Our findings support the hierarchy of influences model, in seeing how individual, organizational and institutional factors play into the process of solution-oriented reporting. Further, Entman’s (1993) framing, which has been used as a theoretical foundation for solutions journalism, is supported based on how journalists think about the practice.

Professionally, our findings illustrate the importance of having a cohesive newsroom that is unified in its mission. Without the support of editors and publishers, it will be harder for journalists to carry out a solutions-based approach to reporting. Groups promoting solutions journalism, such as the Solutions Journalism Network, need to target management and the organizational level just as much, if not more, as the reporters themselves. Unfortunately, lack of resources is not a problem unique to solutions journalism, but the Solutions Journalism Network does offer funding for journalists wishing to carry out solutions-based reports, which is a step in the right direction.

Solutions journalism continues to grow as a practice, and while some impediments remain in securing its legitimacy, journalists who have encountered it are enthusiastic and positive about its future.

Adisa, R. M., Mohammed, R., & Ahmad, M. K. (2003). Solution approach to newspaper framing and ethnic groups’ conflict behaviours. New Media and Communication Studies, 40 , 33-42.

Benesch, S. (1998). The rise of solutions journalism. Columbia Journalism Review , 36-39.

Berkowitz, D. A. (Ed.). (1997). Social meanings of news: A text-reader . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Blaagaard, B. B. (2013). Shifting boundaries: Objectivity, citizen journalism and tomorrow’s journalists. Journalism , 14 (8), 1076-1090.

Bro, P. (2008). Normative navigation in the news media. Journalism, 9 (3), 309-329.

Curry, A. L., & Hammonds, K. H. (2014). The power of solutions journalism . Retrieved from http://engagingnewsproject.org/enp_prod/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ENP_SJN-report.pdf

Curry, A. L., Stroud, N. J. & McGregor, S. (2016). Solutions journalism and news engagement . Retrieved from https://engagingnewsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ENP-Solutions-Journalism-News-Engagement.pdf

Dahmen, N. S. (2016). Images of resilience: The case for visual restorative narrative. Visual Communication Quarterly , 23 (2), 93-107.

Dyer, J. (2015, June 11). Is solutions journalism the solution? Nieman Reports . Retrieved from http://niemanreports.org/articles/is-solutions-journalism-the-solution/

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication , 43 (4), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fink, K., & Schudson, M. (2014). The rise of contextual journalism, 1950s-2000s. Journalism, 15 (1), 3-20.

Hanitzsch, T., Hanusch, F., Mellado, C., Anikina, M., Berganza, R., Cangoz, I., & Virginia Moreira, S. (2011). Mapping journalism cultures across nations: A comparative study of 18 countries. Journalism Studies, 12 (3), 273-293.

Høyer, S. (2005). The idea of the book: Introduction. In H. Pöttker, S. Høyer (Eds.), Diffusion of the news paradigm 1850-2000 (pp. 9-16). Göteborg, SE: Nordicom.

Kempf, W. (2007). Peace journalism: A tightrope walk between advocacy journalism and constructive conflict coverage. Conflict & Communication Online , 6 (2), 1-9.

Kensicki, L. J. (2004). No cure for what ails us: The media-constructed disconnect between societal problems and possible solutions. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81 (1), 53-73.

Kim, S. H., Carvalho, J. P., Davis, A. G., & Mullins, A. M. (2011). The view of the border: News framing of the definition, causes, and solutions to illegal immigration. Mass Communication and Society, 14 (3), 292-314.

Lieber, E., & Weisner, T. S. (2013). Dedoose (Version 4.5) [Software]. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants. Retrieved from http://www.dedoose.com

Loizzo, J., Watson, S. L., & Watson, W. R. (2017). Examining instructor and learner experiences and attitude change in a journalism for social change massive open online course: A mixed-methods case study. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator , doi: 1077695817729586

Lough, K. & McIntyre, K. (in press). Visualizing the solution: An analysis of the images that accompany solutions-oriented news stories . Journalism .

Maras, S. (2013). Objectivity in journalism . Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

McIntyre, K. (2015). Constructive journalism: The effects of positive emotions and solution information in news stories. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Pro-quest Dissertations and Theses. (Publication No. 3703867).

McIntyre, K. (2017, December 14). Solutions journalism: The effects of including solution information in news stories about social problems. Journalism Practice , 1-19. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2017.1409647

McIntyre, K., Dahmen, N. S., & Abdenour, J. (2016, December 30). The contextualist function: US newspaper journalists value social responsibility. Journalism , doi: 1464884916683553.

McIntyre, K., Lough, K. & Manzanares, K. (in press). Solutions in the shadows: The effects of incongruent visual messaging in solutions journalism news stories . Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly

McIntyre, K., & Sobel, M. (2017a). Motivating news audiences: Shock them or provide them with solutions? Communication & Society, 30 (1), 39-56.

McIntyre, K., & Sobel, M. (2017b, May). Reconstructing Rwanda: How Rwandan reporters use constructive journalism to promote peace. Journalism Studies , 1-22, doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1326834

Ryan, M. (2001). Journalistic ethics, objectivity, existential journalism, standpoint epistemology, and public journalism. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 16 (1), 3-22.

Schmitz Weiss, A. (2015). The digital and social media journalist: A comparative analysis of journalists in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. International Communication Gazette. 77(1): 74-101.

Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (2013). Mediating the message in the 21st century: A media sociology perspective . New York, NY: Routledge.

Sillesen, L. B. (2014, September 29). Good news is good business, but not a cure-all for journalism. Columbia Journalism Review . Retrieved from http://archives.cjr.org/behind_the_news/good_news_is_good_business_but.php

Solutions Journalism Network. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.solutionsjournalism.org/impact

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview . Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Thier, K. (2016). Opportunities and challenges for initial implementation of solutions journalism coursework. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 71 (3), 329-343.

Tracy, S. J. (2012). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact . Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?id=KAzBiMCS6uwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Qualitative+research+methods:+Collecting+evidence,+crafting+analysis,+communicating+impact&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj7rrLGsOXZAhVK9WMKHXRNAYsQ6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=Qualitative%20research%20methods%3A%20Collecting%20evidence%2C%20crafting%20analysis%2C%20communicating%20impact&f=false

Tullis, A. (2014, November 18). Constructive journalism: Emerging mega-trend or a recipe for complacency? World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers . Retrieved from https://blog.wan-ifra.org/2014/11/18/constructive-journalism-emerging-mega-trend-or-a-recipe-for-complacency

University of Oregon. (2017). The Catalyst Journalism Project combines investigative and solutions journalism . Retrieved from http://journalism.uoregon.edu/news/catalyst-journalism-project-combines-investigative-solutions-journalism/

Weaver, D. H., Beam, R. A., Brownlee, B. J., Voakes, P. S., & Wilhoit, G. C. (2014). The American journalist in the 21st century: US news people at the dawn of a new millennium . New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Wenzel, A., Gerson, D., Moreno, E., Son, M., & Morrison Hawkins, B. (2017). Engaging stigmatized communities through solutions journalism: Residents of South Los Angeles respond. Journalism , doi: 146488491770312.

Wien, C. (2005). Defining objectivity within journalism. Nordicom Review , 26 (2), 3-15.

Yiping, C. (2011). Revisiting peace journalism with a gender lens. Media Development , 16 , 16-22.

Kyser Lough is a PhD student in the School of Journalism at The University of Texas at Austin and researches visual communication and solutions journalism. He studies how news images are made, selected and interpreted, as well as the photographers themselves in how they define their field and operate within it. For solutions journalism, he investigates audience effects and the factors surrounding the creation and implementation of content by journalists. Broadly, he seeks to improve our knowledge and research interests of both visual communication and solutions journalism while providing guidance and implications to the professional world.

Karen McIntyre is an assistant professor of multimedia journalism in the Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her international and interdisciplinary research focuses on the psychological processes and effects of news media. More specifically, she studies constructive journalism, an emerging contextual form of journalism that involves applying positive psychology and other behavioral science techniques to the news process in an effort to create more productive, engaging, and solution-focused news stories.

Solutions Journalism

Download Full Report

← Journalism

Researchers

Faculty Research Associate

Keith H. Hammonds

Solutions Journalism Network

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

Solutions journalism is reporting about responses to entrenched social problems. It examines instances where people, institutions, and communities are working toward solutions. Solutions-based stories focus not just on what may be working, but how and why it appears to be working, or, alternatively, why it may be stumbling. In engagements with more than 30 newsrooms and hundreds of reporters, producers, and editors across the U.S., the Solutions Journalism Network has identified growing interest in the practice of solutions journalism. But what happens when we put this form of reporting to the test: How do citizens respond?

This report outlines the results of a quasi-experiment conducted by the Solutions Journalism Network and the Center for Media Engagement. 1 The findings demonstrate that solutions-based reporting may be an effective journalistic tool that serves the needs of both audiences and news organizations and that it has the potential to increase reader engagement.

The Problem

Many journalists report compellingly on the world’s problems, but they regularly fail to highlight and explain responses that demonstrate the potential to ameliorate problems, even when those initiatives show strong evidence of effectiveness.

As a result, people are far more aware of what is wrong with society than what is being done to try to improve it. For many issues that receive ongoing news coverage, what’s most absent is not awareness about the problems but awareness about credible efforts to solve those problems. This omission causes many people to feel overwhelmed and to believe that their efforts to engage as citizens may be futile. Research indicates that when journalists regularly raise awareness about problems without showing people what can be done about them, news audiences are more likely to tune out and deny the message or even disengage from public life. 2

Key Findings

The study showed that readers of solutions-based news articles were significantly more likely than non-solutions readers to:

- Have a heightened perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy,

- Feel a stronger connection with news organizations,

- Indicate a desire for potential engagement on an issue.

Implications for Newsrooms

These study results suggest that solutions journalism has the potential to address several major concerns confronting today’s newsrooms. These concerns include: (a) readers’ perceptions, real or imagined, that news is overwhelmingly negative, (b) readers’ feeling that the thoroughness of news reporting is on a downward trend; and (c) the decline in news readership. Each of these concerns, along with solutions journalism’s potential to address them, is explored below.

News Negativity. A prevailing mentality among those who attend to the news is the belief that the majority of news is negative. 3 Although some research has noted a few positive aspects of negative news, overall, it is believed that, on balance, it does more harm than good. 4 Negative news is a contributor to news fatigue, or a diminished desire to turn to the news. 5 The pervasive belief is not only that most news is negative, but that it is, in fact, a reporter’s job to cover negative news. In addition, negative news has been shown to inhibit subsequent information recall. 6 In other words, readers of negative news stories are less likely to remember what they have read after encountering negative information.

Today, many news organizations try to balance the negativity of news by including periodic feel-good reporting, such as profiles of “heroes” or people “making a difference.” This approach reveals an implicit bias held by many journalists: a belief that reporting on efforts to solve social problems is of secondary importance to society – a belief that may not be shared by news audiences. 7 Given the challenge of balancing the tone of coverage, solutions journalism may offer a more serious-minded approach, providing readers with an entry point to engage more deeply with difficult issues.

News Thoroughness. In 2013, the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism reported that many people had turned away from a news outlet because of a perceived decline in news quality. 8 Specifically, the study asked people if they thought the quantity of news was in decline or the quality of news was in decline. More than 60% of respondents said that news quality was in decline. It is possible that solutions journalism, by giving people a broader view of the news – namely, reporting on problems and responses to those problems – could help to reverse this downward trend.

Readership Decline . Dovetailing with the perception of declining news thoroughness is the finding that those who believe news quality is in decline are also turning away from the news. The same Pew study referenced above asked people the following question: “Have you stopped turning to a particular news outlet because you felt they were no longer providing you with the news and information you were accustomed to?” 9 Sixty-five percent of respondents answered “yes.” What this tells us is that if a news outlet is not meeting the needs of the news consumers, these consumers may look elsewhere for their information. Given these study results, we believe that further research is warranted to explore questions about whether solutions journalism has the potential to arrest readership decline – particularly decline associated with news quality – and to drive other changes in audience news consumption, engagement or brand loyalty.

In the study, a sample of 755 U.S. adults was presented with one of six news articles. The articles reported on three different issues: the effects of traumatic experiences on children in American schools, homelessness in urban America, and a lack of clothing among poor people in India. For each issue, highly similar articles were compared: one that focused exclusively on the problem (non-solution version), and one that included identical reporting on the problem, but added reporting about a potential response to mitigate that problem (solution version). The addition of solutions content was the only difference between the two articles.

The results of this test indicate that solutions-based journalism holds promise in at least three areas: heightening audiences’ perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy, strengthening the connection between audiences and news organizations, and catalyzing potential engagement on an issue.

Heightening audiences’ perceived knowledge and sense of efficacy

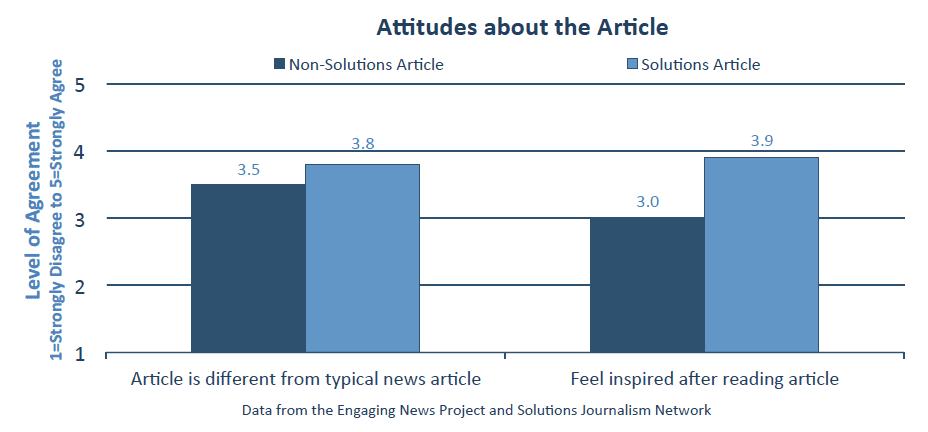

- Say the article seemed different from typical news articles

- Perceive that they gained more knowledge about the issue in the article

- Indicate that they felt better informed about the issue

- Respond that the article had increased their interest in the issue

- Believe they could contribute to a solution to the issue

- Believe that there are effective ways to address the issue

- Say that the article influenced their opinion about the issue

- Indicate that they felt inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article

Strengthening the connection between audiences and news organizations

Solutions readers were more likely than non-solutions readers to indicate that they would:

- Read more articles by the person who authored the article they read

- Read more articles from the newspaper in which their article appeared

- Read more articles about the issue

- Talk to friends or family about the issue

- Share the article they read on social media

Catalyzing potential engagement on an issue

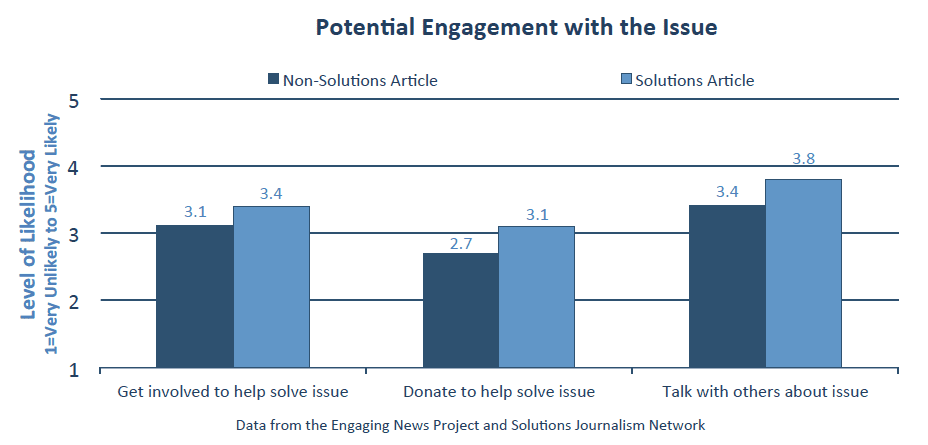

Solutions readers were more likely than non-solutions readers to indicate their desire to:

- Get involved in working toward a solution to the issue

- Donate money to an organization working on the issue

All three shifts, we believe, reflect favorably on audience relationships with news and news organizations. People who think they know more about an issue, share a story with a friend, and/or feel more empowered to act are likely to attach greater value to the news and to feel a stronger attachment to the respective news source. 10

Changes in Perceived Knowledge and Sense of Efficacy

Readers of solutions-based stories expressed more agreement than readers of non-solutions stories that the article they read was different than the typical newspaper article. 11 Readers of the solution versions also were more “inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article” than their non-solutions counterparts. 12

It should be noted that all of the results reported in this study, and displayed in the accompanying charts, indicate statistically significant differences in responses between solutions and non-solutions article readers. In other words, the chances are extremely slim that the differences in responses are merely based on chance.

Changes in Readers’ Connections to News Organizations

Respondents were asked how likely they were to: share the article on social media, read more articles by the unnamed author of the article they read, read more articles in the unnamed newspaper in which the article appeared, and read more articles about the particular issue. 16 In all instances, survey takers who read solutions articles were significantly more likely to indicate their desire to enact these behaviors than those who read non-solutions articles.

Changes in Citizens’ Engagement in Society

Respondents were asked about their likelihood of getting involved in working toward a solution to the issue, donating to an organization working on the issue, and talking to family and friends about the issue. 17 Again, in all cases, those who read solutions articles indicated higher likelihoods than those who read non-solutions articles.

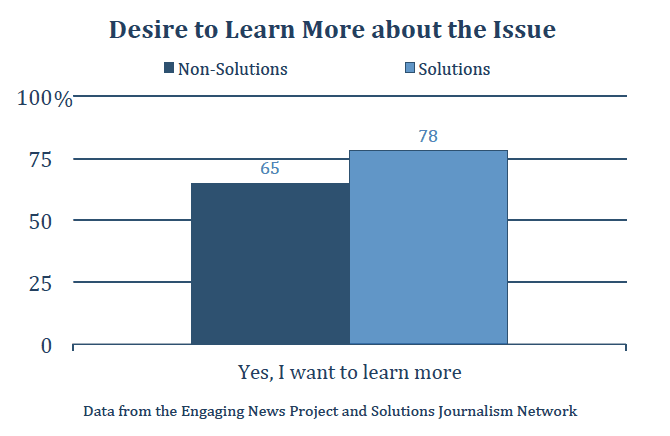

Readers also were asked the following yes/no question at the end of the survey: “Would you like to learn more about how to get involved in finding solutions to this issue?” As was the case in all other instances in this study, readers of solutions-based articles gave significantly more “yes” responses than those reading non-solutions articles. 18

Background on Solutions Journalism

Solutions journalism is critical reporting that investigates and explains credible responses to social problems. It delves into the how-to’s of problem-solving, often structuring stories as puzzles or mysteries that investigate questions like: What models are having success reducing the high school dropout rate and how do they actually work?

When done well, the stories can provide valuable insights about how communities may better tackle important problems. As such, solutions journalism can be both highly informative and engaging. News organizations such as The Seattle Times, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and the Deseret News, among others, have deployed solutions reporting in an attempt to create a foundation for productive, forward-looking (and less polarizing) community dialogues about vital social issues.

In trying to meet these goals, a solutions journalism story attempts to answer in the affirmative the following ten questions (which serve as a framework, not a set of rules): 19

- Does the story explain the causes of a social problem?

- Does the story present an associated response to that problem?

- Does the story refer to problem-solving and how-to details?

- Is the problem-solving process central to the story’s narrative?

- Does the story present evidence of results linked to the response?

- Does the story explain the limitations of the response?

- Does the story contain an insight or teachable lesson?

- Does the story avoid reading like a puff piece?

- Does the story draw on sources that have ground-level expertise, not just a 30,000-foot understanding?

- Does the story give greater attention to the response than to a leader, innovator, or do-gooder?

A good example of solutions journalism will address many, though not necessarily all, of the above questions. Solutions journalism is a form of explanatory journalism that may serve as a form of watchdog reporting, highlighting effective responses to problems in order to spur reform in areas where people or organizations are failing to respond adequately, particularly when better options are available.

Methodology

A survey-based quasi-experimental design was employed to test the effects of solutions journalism. Survey respondents were recruited via the data-collection company, Survey Sampling International, which administered the online survey to a nationwide sample of 1,500 Americans.

Respondents were invited to read “a recent article that appeared in a U.S. newspaper,” and told that after reading the article they would be asked several questions. Respondents were encouraged to read the article thoroughly, as they were told that they would not be able to return to the text of the article after they finished reading. The articles were from the Fixes section of the New York Times. Upon reading the instructions, respondents saw one of six articles. The articles consisted of three topic pairs, where each pair dealt with a different topic. The topics were: (a) the effects of traumatic experiences on children in American schools; (b) homelessness in urban America; and (c) a lack of clothing among poor people in India. Each pair of articles contained a solutions version and a non-solutions version. Other than the presence/absence of solutions content, the articles were identical. The text of each article is located in an appendix at the end of this report.

After reading the article, all respondents were asked to respond to an identical series of survey items. Most of the survey items consisted of 5-point Likert-type scales, where respondents were given a statement and asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statement (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). One closed-ended question was asked (“Would you like to learn more about how to get involved in finding solutions to this issue?), as well as one open-ended item (Did this article influence the way you think about this issue? If so, how?) 20

Respondents then were asked whether or not they believed that the author of the story reported on a solution to each problem. This question was used as a manipulation check, to determine whether or not respondents carefully attended to the experimental stimuli. Of the 1,500 respondents who completed the survey, nearly half failed the manipulation check. Those who failed the manipulation check spent significantly less time with the study (Mann-Whitney U=188627.50, p<.001). Data for those who failed the manipulation check were discarded from the statistical analysis. Furthermore, some survey items were counter-valenced in order to detect any respondents who might select responses in a single column for all items (for example, someone who chooses “strongly agree” for every item). All those who gave identically-valenced responses for the nine Likert-type items were removed from the data (n = 55). Lastly, four respondents selected “under 18” in the age question, and as this survey’s target sample was adults, data for these respondents were discarded. The final sample used for data analysis consisted of 755 respondents.

Of those 755 respondents:

- 64% are female

- The median age range is 45-54 years old

- The median education level completed by the respondents is “some college”

- The median yearly income range is $50,000-$75,000

- 34% self-identify as conservative, 31% self-identify as liberal, and 32% indicate that they are neither/middle of the road

- 79% identify themselves as white, 11% identify as black, 6% identify as Asian, and 5% identify as Hispanic

- 9% identify as self-employed, 45% as employed by someone else, 9% as unemployed, 12% as homemakers, 18% as retired, and 7% as students

See full appendix in the full report.

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Curry, Alexander and Hammonds, Keith H. (2014, June). Solutions journalism. Center for Media Engagement . https://mediaengagement.org/research/solutions-journalism/

- This study qualifies as a quasi-experiment, as opposed to a full experiment because we include only data from those who did not fail the manipulation check. Those reading a solutions article were more likely to answer the manipulation check correctly than those reading a non-solutions article. This means that the resulting sample is neither randomly assigned nor randomly selected from the population. To mitigate this concern, we analyzed and controlled for, demographic factors that vary among the conditions. When data analysis is conducted using those who passed and those who failed the manipulation check, (n = 1,443), evidence of significant, albeit more modest, findings remain. In this case, those exposed to a solutions journalism article are significantly more likely than their non-solutions counterparts to feel that they had gained new knowledge about the topic from reading the article, indicate that they felt inspired and/or optimistic after reading the article, and believe that there are effective ways to address the issue. [ ↩ ]

- Associated Press and the Context-Based Research Group, A new model for news; Benesh, S. (1998). The rise of solutions journalism. Columbia Journalism Review ; Feinberg, M., & Robb, W. (2010). Apocalypse soon? Dire messages reduce belief in global warming by contradicting just-world beliefs. Ps y c ho l og i c a l S c i e n c e , 22 (1), 34-38; Glassner, B., (2004). Narrative techniques of fear-mongering. So c i a l R es ea r c h : An International Quarterly, 71 (4), 819-826; Merritt, D. (1998). Pu b li c j ou r na li s m and public life: Why telling the truth is not enough . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Patterson, T. (2002). Why is the news so negative these days? George Mason University History News Network, http://hnn.us/article/1134, Pauly, J. J. (2009). Is journalism interested in resolution, or only in conflict? M a r qu e tt e L a w R e v i e w , 93 (1), 7-23. [ ↩ ]