An official website of the United States Government

- Kreyòl ayisyen

- Search Toggle search Search Include Historical Content - Any - No Include Historical Content - Any - No Search

- Menu Toggle menu

- INFORMATION FOR…

- Individuals

- Business & Self Employed

- Charities and Nonprofits

- International Taxpayers

- Federal State and Local Governments

- Indian Tribal Governments

- Tax Exempt Bonds

- FILING FOR INDIVIDUALS

- How to File

- When to File

- Where to File

- Update Your Information

- Get Your Tax Record

- Apply for an Employer ID Number (EIN)

- Check Your Amended Return Status

- Get an Identity Protection PIN (IP PIN)

- File Your Taxes for Free

- Bank Account (Direct Pay)

- Payment Plan (Installment Agreement)

- Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS)

- Your Online Account

- Tax Withholding Estimator

- Estimated Taxes

- Where's My Refund

- What to Expect

- Direct Deposit

- Reduced Refunds

- Amend Return

Credits & Deductions

- INFORMATION FOR...

- Businesses & Self-Employed

- Earned Income Credit (EITC)

- Child Tax Credit

- Clean Energy and Vehicle Credits

- Standard Deduction

- Retirement Plans

Forms & Instructions

- POPULAR FORMS & INSTRUCTIONS

- Form 1040 Instructions

- Form 4506-T

- POPULAR FOR TAX PROS

- Form 1040-X

- Circular 230

Education credits: questions and answers

More in credits & deductions.

- Family, Dependents and Students

- Individuals Credits and Deductions

- Business Credits and Deductions

Education credits

Find the answers to the most common questions you ask about the Education Credits -- the American opportunity tax credit (AOTC) and the lifetime learning credit (LLC).

Q1. Have there been any changes in the past few years to the tax credits for higher education expenses?

A1. No, but the Protecting Americans Against Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015 made AOTC permanent. The AOTC helps defray the cost of higher education expenses for tuition, certain fees and course materials for four years.

To claim the AOTC or LLC, use Form 8863, Education Credits (American Opportunity and Lifetime Learning Credits) . Additionally, if you claim the AOTC, this law requires you to include the school’s Employer Identification Number on this form.

In addition, the Trade Preferences Extension Act 2015 requires most students to have received a Form 1098-T. To be eligible to claim the AOTC or the LLC, this law requires a taxpayer (or a dependent) to have received Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement, from an eligible educational institution.

Q2. How does AOTC differ from the existing LLC?

A2. Unlike the other education tax credits, the AOTC is allowed for expenses for course-related books, supplies and equipment that are not necessarily paid to the educational institution but are needed for attendance. It also differs because you can claim the credit for four tax years instead of no limit on the number of years you can claim the LLC. See Education Credits: AOTC and LLC for more information.

Q3. How much is the AOTC worth?

A3. It is a tax credit of up to $2,500 of the cost of tuition, certain required fees and course materials needed for attendance and paid during the tax year. Also, 40 percent of the credit for which you qualify that is more than the tax you owe (up to $1,000) can be refunded to you.

Q4. How does AOTC affect my income taxes?

A4. You reduce the amount of tax you owe dollar for dollar by the amount of the AOTC for which you qualify up to the amount of tax you owe. If the amount of the AOTC is more than the tax you owe, then up to 40 percent of the credit (up to $1,000) can be refunded to you.

Q5. What are qualified tuition and related expenses for the education tax credits?

A5. In general, qualified tuition and related expenses for the education tax credits include tuition and required fees for the enrollment or attendance at eligible post-secondary educational institutions (including colleges, universities and trade schools). The expenses paid during the tax year must be for an academic period that begins in the same tax year or an academic period that begins in the first three months of the following tax year.

The following expenses do not qualify for the AOTC or the LLC:

- Room and board

- Transportation

- Medical expenses

- Student fees, unless required as a condition of enrollment or attendance

- Same expenses paid with tax-free educational assistance

- Same expenses used for any other tax deduction, credit or educational benefit

Q6. What additional education expenses qualify for the AOTC, but not the LLC?

A6. For the AOTC but not the LLC, qualified tuition and related expenses include amounts paid for books, supplies and equipment needed for a course of study. You do not have to buy the materials from the eligible educational institution. Add amounts paid for these materials to Form 8863 to your other adjusted qualified education expenses. The total of all qualified tuition and related expenses for calculating the AOTC cannot exceed $4,000 and as explained in Q&A 3, the maximum allowable credit is $2,500. See Qualified Education Expense for more information.

Q7. Does a computer qualify for the AOTC?

A7. It depends. The amount paid for the computer can qualify for the credit if you need the computer for attendance at the educational institution.

Q8. Who is an eligible student for the AOTC?

A8. An eligible student for the AOTC is a student who:

- Was enrolled at least half time in a program leading toward a degree, certificate or other recognized educational credential for at least one academic period during the tax year,

- Has not completed the first four years of post-secondary (education after high school) at the beginning of the tax year,

- Has not claimed (or someone else has not claimed) the AOTC for the student for more than four years, and

- Was not convicted of a federal or state felony drug offense at the end of the tax year.

Q9. If a student was an undergraduate student during the first part of the tax year and became a graduate student that same year, can the student claim or be claimed for the AOTC for the qualified tuition and related expenses paid during the entire tax year?

A9. Yes, AOTC can be claimed for this student for qualified educational expenses paid during the entire tax year, if all other requirements are met and the student:

- Has not completed the first four years of post-secondary (education after high school) education as of the beginning of the tax year, and

- Has not claimed the AOTC for more than four tax years.

Q10. I'm just beginning college this year. Can I claim the AOTC for all four years I pay tuition?

A10. Yes, if you remain an eligible student and no one can claim you as a dependent on their tax return, the AOTC is available for qualifying expenses paid during each tax year.

Q11. How do I calculate AOTC?

A11. You calculate the AOTC based on 100 percent of the first $2,000 of qualifying expenses, plus 25 percent of the next $2,000, paid during the tax year.

Q12. Is there an income limit for AOTC?

A12. Yes. To claim the full credit, your MAGI, modified adjusted gross income (See Q&A 13 for MAGI definition) must be $80,000 or less ($160,000 or less for married taxpayers filing jointly). If your MAGI is over $80,000 but less than $90,000 (over $160,000 but less than $180,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly), the amount of your credit is reduced. If your MAGI is over $90,000 ($180,000 for married taxpayers filing joint), you can't claim the credit.

Q13. What is "modified adjusted gross income" for the purpose of the AOTC?

A13. For most filers, it is the amount of your AGI, adjusted gross income, from your tax return. If you file Form 1040 or 1040-SR, your MAGI is the AGI on line 11 of that form, modified by adding back any:

- Foreign earned income exclusion

- Foreign housing exclusion

- Foreign housing deduction

- Exclusion of income by bona fide residents of American Samoa or Puerto Rico.

Q14. How do I claim an education tax credit?

A14. To claim the AOTC or LLC, use Form 8863, Education Credits (American Opportunity and Lifetime Learning Credits) . Additionally, if you claim the AOTC, the law requires you to include the school’s Employer Identification Number on this form.

Q15. Where do I put the amount of my education tax credit on my tax return?

A15. To claim the American opportunity credit complete Form 8863 and submitting it with your Form 1040 or 1040-SR. Enter the nonrefundable part of the credit on Schedule 3 (Form 1040 or 1040-SR), line 3. Enter the re-fundable part of the credit on Form 1040 or 1040-SR, line 29.

To claim the lifetime learning credit complete Form 8863 and submitting it with your Form 1040 or 1040-SR. Enter the credit on Schedule 3 (Form 1040 or 1040-SR), line 3.

Q16. My dependent child attended college half time in 2023 for a semester and will attend full time starting 2024. Can I skip taking AOTC for 2023 because her expenses are low and claim AOTC for 2024 and future years? (updated January 10, 2024)

A16. Yes, you are not required to claim the credit for a particular year. If your child’s college does not consider your child to have completed the first four years of college at the beginning of 2023, you can qualify to take the credit for up to four tax years.

Q17. I completed two years of college right after graduating from high school years ago before there was the Hope or AOTC. I now returned to college to finish my degree on a part time basis; can I claim the AOTC and, if so, for how many years?

A17. You can claim AOTC, for any semester or other academic period if you take at least half the full-time course load for the first four years of college. If you take half the course load for at least one semester or other academic period of each tax year, and your college does not consider you to have completed the first four years of college as of the beginning of the tax year, you can qualify to take the AOTC for up to four tax years.

Q18. What is Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement, and do I need to receive a Form 1098-T to claim the AOTC?

A18. Yes. The Form 1098-T is a form provided to you and the IRS by an eligible educational institution that reports, among other things, amounts paid for qualified tuition and related expenses. The form may be useful in calculating the amount of the allowable education tax credits. In general, a student must receive a Form 1098-T to claim an education credit. But an eligible educational institution is not required to provide the Form 1098-T to you in certain circumstances, for example:

- Nonresident alien students, unless the student requests the institution to file Form 1098-T,

- Students whose tuition and related expenses are entirely waived or paid entirely with scholarships or grants, or

- Students for whom the institution does not maintain a separate financial account and whose qualified tuition and related expenses are covered by a formal billing arrangement with the student’s employer or a government agency, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Department of Defense.

Q19. I did not receive a Form 1098-T because my school is not required to provide a Form 1098-T to me for 2023. Can I still claim an education credit for tax year 2023? (updated January 10, 2023)

A19. Yes. You can still claim the AOTC if you did not receive a Form 1098-T because the school is not required to provide you a Form 1098-T if:

- The student and/or the person able to claim the student as a dependent meets all other eligibility requirements to claim the credit,

- The student can show he or she was enrolled at an eligible educational institution, and

- You can substantiate the payment of qualified tuition and related expenses.

Be sure to keep records that show the student was enrolled and the amount of paid qualified tuition and related expenses. You may need to send copies if the IRS contacts you regarding your claim of the credit.

Q20. In 2022, my school went out of business and closed. I did not get a Form 1098-T for 2023 from the school. Can I still claim an education credit for tax year 2023? (updated January 10, 2023)

A20. Yes. You can still claim an education credit if your school that closed did not provide you a Form 1098-T if:

- The student can show he or she was enrolled at an eligible educational institution, and

Q21. How do I know if my school is an eligible educational institution?

A21. An eligible educational institution is a school offering higher education beyond high school. It is any college, university, vocational school, or other post-secondary educational institution eligible to participate in a Federal student aid program run by the U.S. Department of Education. This includes most accredited public, nonprofit and privately-owned–for-profit post-secondary institutions.

If you aren’t sure if your school is an eligible educational institution:

Check to see if the student received a Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement. Eligible educational institutions are required to issue students Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement (some exceptions apply).

Ask your school if it is an eligible educational institution, or

See if your school is on the U.S. Department of Education’s Database of Accredited Post Secondary Institutions and Programs (DAPIP) or the Federal Student Loan Program list .

Q22. I received a letter from the IRS questioning my AOTC claim. What should I do?

A22. If you receive a letter or are audited by the IRS, it can be because the IRS did not receive a Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement, or the IRS needs additional information to support the amounts of qualified tuition and related expenses you reported on Form 8863.

If you did receive a Form 1098-T, review it to make sure the student’s name and Social Security number are correct. If either is not correct, contact the school and ask the school to correct the information for future 1098-T reporting. If the student should have, but did not receive the Form 1098-T, contact the school for a copy.

Please note as described above, there are exceptions in which eligible educational institutions are not required to provide a Form 1098-T. See Q&A 18 for more information about the Form 1098-T.

If you claimed expenses that were not reported on the Form 1098-T in Box 1 as amounts paid, send the IRS copies of receipts, cancelled checks or other documents as proof of payment. See your letter for further instructions for what documents to send.

If you don't have the letter, see Forms 886-H-AOC and 886-H-AOC-MAX for examples. Form 886-H-AOC is also available in Spanish.

Q23. Can students with an F-1 Visa claim the AOTC?

A23. For most students present in the U.S. on an F-1 Student Visa the answer is no. Generally, the time an alien individual spends studying in the U.S. on an F-1 Student Visa doesn't count in determining whether he or she is a resident alien under the substantial presence test. See Publication 519, U.S. Tax Guide for Aliens for more information.

Q24. I am a Nonresident Alien, can I claim an education tax credit?

A24. Generally, a Nonresident Alien cannot claim an education tax credit unless:

- You are married and choose to file a joint return with a U.S. citizen or resident spouse, or

- You are a Dual-Status Alien and choose to be treated as a U.S. resident for the entire year. See Publication 519, U.S. Tax Guide for Aliens for more information.

Q25.What should I do if the student’s return was incorrectly prepared and filed by a professional tax preparer?

A25. You are legally responsible for what’s on your tax return, even if someone else prepares it. The IRS urges you to choose a tax preparer wisely. For more information, read IRS’s How to Choose a Tax Return Preparer .

Q26. Are there any other education tax benefits?

A26. Yes, see the Tax Benefits for Education: Information Center for more information.

Return to Education Credits Home Page

Education Benefit Resources

Information for Schools, Community and Social Organizations on our Refundable Credits Toolkit

Tax Preparer Due Diligence Information on our Tax Preparer Toolkit

Watch out for these common errors made when claiming education credits

- Students listed as a dependent or spouse on another tax return

- Students who don’t have a Form 1098-T showing they attended an eligible educational institution

- Students claimed for whom qualified education expenses were not paid

- Claiming the credit for a student not attending a college or other higher education

Find more answers to the questions you ask about the education credits

See Education Credits: Questions and Answers

More education benefit resources

- Education Credits: AOTC and LLC

- American Opportunity Tax Credit

- Lifetime Learning Credit

- Compare Education Credits

- Interactive App: "Am I Eligible to Claim an Education Credit?"

- No Double Benefits Allowed

- Qualified Education Expense

- Eligible Educational Institution

- Tax Benefits for Education: Information Center

Technical Forms and Publications

- Publication 970, Tax Benefits for Education PDF

- Form 8863, Education Credit PDF

- Form 8863 Instructions PDF

- Form 1098-T, Tuition Statement PDF

- Forms 1098-E and T Instructions PDF

Education Credit Marketing Resources

- Publication 4772 American Opportunity Tax Credit Flyer PDF

- Publication 5081 Education Credits On-line Resource PDF

- Publication 5198 Are you or a family member attending college or taking courses to acquire or improve job skills? PDF

- Tax Tip 2022-38 Two tax credits that can help cover the cost of higher education

- Tax Tip 2022-123 College students should study up on these two tax credits

What is a Post-Secondary Degree, and Do I Need One?

Quick Degree Finder

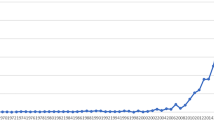

Part of the American dream has always been to send your children to college so they could obtain their degree. Despite a struggling economy, the last decade has seen record numbers of people seeking higher education. In 2019 alone, nearly 20 million Americans enrolled in colleges and universities to receive their degree, and experts are expecting this number to increase over the coming years .

And it’s not just wealthy families that are sending their kids to college. Recent surveys have found more low- and middle-income families are making higher education a priority.

If you have been wondering about getting a post-secondary degree – what it was exactly and if it was something that could help you earn more – be sure to read this entire article , because I’m going to share absolutely everything you need to know about post-secondary degrees.

Let’s get started!

What is a Post-Secondary Degree?

To keep things simple, a post-secondary degree is one that a person can obtain once they’ve received their high school diploma or GED. Post-secondary degrees may come from a community college, vocational school, an undergraduate college or a university.

These degrees show prospective employers that you have taken the time to receive specialized skills and knowledge. Beyond helping you stand out from other candidates come hiring time, post-secondary degrees can help you earn more – and in some cases – quite a bit more!

Types of Post-Secondary Degrees

As I mentioned, a post-secondary degree lets prospective employers know you have obtained specialized skills and information. But there are different types – or levels – of post-secondary degrees, and each one connotes a different level of expertise.

Associates Degree

Associates degrees are typically obtained in two years at either a community college or vocational/technical school. These degrees offer students a higher understanding of different professional settings and prepares them for entry-level work.

An associates degree can also be counted as the first two years of a 4-year bachelor’s degree. Many students, particularly adult students, will obtain their associates degree in order to get their foot in the door of their chosen field. Later, they can use this degree to jumpstart their next leg of education and obtain their bachelor’s degree, which will provide further employment and earnings opportunities.

Recommended Schools

Bachelor’s Degree

When we hear the term “college degree,” most people think of the classic 4-year bachelor’s degree. This is the most popular post-secondary degree people earn.

Bachelor’s programs provide a more holistic educational experience because they not only teach employable skills, but also academic subjects that help sharpen the students’ critical thinking skills.

While it typically takes students four years to earn a bachelor’s degree, it can sometimes take six or even eight years to complete. This is usually due to financial reasons, however. If you’re interested in obtaining a bachelor’s degree, be sure to read this article all the way to the end because I’m going to share how you can earn your bachelor’s degree for less money and even cut your time in half!

Master’s Degree

Once you have obtained your bachelor’s degree you may choose to go on and pursue a master’s degree. These programs allow students to gain even more expertise around a particular field of study. Depending on the program, master’s degrees typically take an additional two to three years to complete. Once obtained, these degrees can help you advance your career into management roles and earn much higher salaries.

Obtaining a doctorate degree is the highest academic achievement a person can attain. Holders of Ph.Ds. are usually in top positions in their field and earn much more. How much? Keep reading, I’m about to let you in on some salary secrets !

The Benefits of a Post-Secondary Education

At this point you hopefully understand what a post-secondary degree is. But you may still be wondering if obtaining one of these degrees is worth the time and cost.

The following are just some of the benefits of earning a post-secondary degree.

Higher income

I have been alluding to the fact that obtaining a higher degree usually leads to greater earning potential. According to a new report from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW), those who have obtained their post-secondary degree can expect to earn quite a bit more than those with only a high school diploma.

Of course, when it comes to earning potential, other factors come into play, such as field of study, occupation and location of your employment. So for instance, someone with a master’s of fine art degree may not earn as much as an engineer with only a bachelor’s degree.

Having said that, surveys taken over the years, including this recent one, have found certain generalized statements, such as those with even an associates degree can expect to earn 20% more than those with a high school diploma or GED.

Those with bachelor’s degrees can expect to earn between 35% and 85% more than those with only a high school diploma, while those with master’s degrees and Ph.Ds. can earn between 85% and 100% more than those with only a high school diploma.

So, if you are someone who is looking to advance your career and start earning more, getting a post-secondary degree makes a lot of sense!

Better Employee Benefits

You may not know this, but jobs that require you to have a bachelor’s degree or higher typically offer better job benefits. For instance, you may find your employer offers healthcare coverage, retirement plans, paid time off and other awesome perks.

More Career Options

It’s simple really: the higher you go with your education, the more career opportunities are available to you. While someone with an associates degree will be able to seek entry-level employment, someone with a master’s degree or Ph. D. will fill the highest positions and earn the highest salary.

Having said that, I want to make it clear that master’s degrees and Ph. Ds. are not necessary to have a rewarding and lucrative career. Many people have the career of their dreams and earn a great salary by earning a bachelor’s degree.

Job Security

If you’ve been in the job market over the last decade, you know that when the economy struggles, employers need to make cuts. Without question, those employees who have the most skills and expertise offer the most value to their employers and therefor have greater job security.

Job Satisfaction

We spend eight hours a day (or more) five days a week (or more) at our jobs. That’s a lot of time dedicated to something you may not like doing. Life just feels better when we love our work. Often, the careers that bring those most meaning and purpose into our lives, such as those in healthcare, science or education, require a post-secondary degree.

This isn’t by any means an exhaustive list of benefits, but these give you an idea of why you may seriously want to consider obtaining your post-secondary degree.

Cons of a Post-Secondary Education

Of course, to decide if a post-secondary education is right for you, you’ll also want to take into consideration a couple of cons, namely:

- It’s Expensive!

Obtaining a college degree is a definite financial commitment. And when you hear about students graduating with a mountain of student loan debt, it can stop you from following your dreams.

There are other common ways to pay for college such as applying for grants and scholarships. Unfortunately, what many students don’t realize is, this endeavor often takes a lot of time with no real payoff. There are only so many grants and scholarships to go around, and so most people will waste hours applying and never see any financial help.

Fear not – there is a simple way to save money toward the cost of college tuition, and I’m about to share that with you in just a moment.

Traditional College Degrees are Hard to Obtain for Adult Students

If you’re a working adult with family responsibilities, it can be next to impossible for you to put your life on hold so that you can move to another state to attend college for four years! Even attempting to take evening classes at your local community college can be a challenge when you have a growing family.

Without question, these two cons are why so many adults give up their pursuit of higher education. And that’s too bad because as we’ve seen, earning a post-secondary degree can be life changing!

Well, the good news is, there is any easy fix for these two problems. Earn your post-secondary degree online!

Can I Really Earn My Post-Secondary Degree Online?

Yes, you really can. In fact, according to one recent article in US News, over 6 million students have found earning their college degree online to be the fastest and easiest way to do it!

Here are some of the main benefits of earning your post-secondary degree online:

It’s More Affordable

Traditional college tuition can cost tens of thousands of dollars. It’s getting harder and harder for the average person to be able to afford this.

An online education, on the other hand, costs just a fraction of a typical education. You see, a physical brick and mortar school has a lot of operating expenses, and those expenses get passed onto you, the student.

Online degrees don’t have these same operating expenses and so you can save a ton. In addition, OnlineDegree.com can help you find even better ways to save. We’ve partnered with accredited colleges and universities across the country that not only offer online courses, they also offer upfront tuition discounts.

And as if that isn’t incredible enough, OnlineDegrees.com offers our students FREE classes for credit. You read that right! Take as many FREE classes as you’d like, then apply those later toward your degree. We’ll connect you with those programs that will accept these credits, thereby saving you EVEN MORE money and helping you earn your degree in far less time!

Hey there win/win!

If you’re a working adult raising a young family, you’ll be happy to know that earning your degree online offers a lot of necessary flexibility. Real life can often get in the way of your evening or weekend classes. Your boss may ask you to stay late, or your kid may get sick.

When you earn your degree online, you study when and where is most convenient for YOU. Set your own schedule and never have to worry about missing work or an important family event ever again!

Adult Friendly

Many institutions that offer online degree programs go out of their way to be adult friendly . This means in addition to being more flexible and affordable, these programs also do things like waive the need to submit SAT or ACT scores and also have open admissions. With open admissions, you can sign up for a post-secondary degree 24/7 365. You DON’T have to try and get your application package in by a specific date like most traditional colleges require.

Are You Ready to Get Started with Your Post-Secondary Degree?

I hope this article has answered any questions you may have had about post-secondary degrees. Without question, earning a post-secondary degree can help you build a rewarding career that offers numerous opportunities and a great salary.

And now you know you can earn this degree online far faster and more affordably than you ever thought possible!

OnlineDegree.com is 100% free for you to use . We provide you the tools to meet your education goals so you can learn your way to a more satisfying and prosperous life. By using our Smartplan , you can easily find ways to save time and money in just a few mouse clicks.

Our Smartplan will help you find:

- FREE courses you can take for credit

- Available tuition discounts

- Schools that are “adult friendly” and offer flexible enrollments and course schedules

- Schools that don’t require SAT or ACT scores

- And much more!

It only takes two minutes to sign up and get started on your journey toward earning your post-secondary degree and a brighter future .

What are you waiting for? Get started today .

Related Articles

How to Be Successful in College in 2022 – 7 Simple Tips to Succeed

How Do Scholarships Work? Read This First…Truth is Shocking

7 Best College Majors 2024: What Should I Major In?

How to Choose a College – 10 Things You Must Consider in 2024

Why Go to College? Top 13 Benefits for Adult Students in 2022

Top 5 Best Alternatives to Community College for 2024

About the author, grant aldrich.

The first 4 years of postsecondary education are generally the freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior years of college.

This information is found in Publication 970, Tax Benefits for Education.

Staffing shortages undermine transitional kindergarten rollout

Student journalists on the frontlines of protest coverage

How can California teach more adults to read in English?

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: California and beyond

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

May 14, 2024

Getting California kids to read: What will it take?

April 24, 2024

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

College & Careers

Postsecondary education should be a right for all

Lia Izenberg

May 6, 2021.

The pandemic is exacerbating an already wide chasm in opportunity and access to higher education in the Bay Area — and across the United States.

Before the pandemic, only 22% of students from low-income communities nationally earned a postsecondary degree, compared to 67% of their peers from high-income areas.

In the nine-county Bay Area, for adults age 25 and older, only 29% of Black and 22% of Latino people hold bachelor’s degrees compared with 60% of their white peers.

That was before the pandemic, and now it seems that even fewer California students are taking the steps to enroll in college during the coming year, and possibly beyond. According to a recent EdSource article , college financial aid applications from students under 18 are considerably down compared to prior years, with just 314,855 students under age 18 submitting an application (27,522 fewer than in 2020) as of February 15.

One core issue contributing to this degree divide is the lack of access to high-quality college counseling for students, particularly those in low-income communities. Chronic low spending on counselors has led to extremely high counselor-to-student ratios.

In 2011, high school students received an average of only 38 minutes of college advising in their high school career. Since then, some districts that have invested in more counselors have seen improvement in college-going rates as a result, but these investments require tough trade-offs and are harder to make for lower-income districts that tend to have smaller budgets. California is 21st in the nation in per-pupil spending despite its high cost of living, which means districts have to make their dollars stretch farther.

In affluent communities, accessing support to plan postsecondary education isn’t a question — it’s a given. There, well-resourced high schools typically have robust college counseling programs, parents hire private college coaches or students already know what colleges they want to apply to and how to do so.

At this moment when the nation is paying more attention to deeply rooted inequities, we have an opportunity to reimagine what effective preparation for a postsecondary education can look like. We should focus on investing in postsecondary access and success in school districts that have not historically had the resources or vision to do so for every child . Postsecondary education should be the baseline expectation for all students.

This means systematically ensuring that every child, regardless of apparent interest, has access to a high-quality curriculum, advising, mentoring and data that help them make informed decisions about their futures and to apply, enroll and matriculate to a postsecondary institution.

There are many nonprofit and community-based programs that are working toward this goal; 10,000 Degrees and Destination College Advising Corps , for example, both do their work embedded within school buildings, and organizations like the Northern California College Promise Coalition are working to build momentum toward our shared goal of postsecondary success for all.

At OneGoal , the organization I head in the Bay Area, we offer a three-year program that starts as a G-Elective — one of the requirements for entry to the University of California and California State systems — during junior year, and continues through senior year and the first year of post-secondary education.

One of the students who participated in the course was Jorge Ramirez, now a freshman at Sacramento State. He told us that before knowing what his options were, he did not plan to go to college because he wasn’t motivated to enroll, and, more important, he didn’t see how he would find the funds to do so.

After he enrolled in the course in 2018, he learned about the FAFSA , a form to apply for college financial aid from the federal government, and the entire college application process. While he originally wanted to study engineering in college, he discovered his passion once in school and is now working on getting his bachelor’s degree with the goal of becoming a social worker.

Our experience suggests that by embedding postsecondary planning into the school day, along with equipping educators to act as mentors and supporters to students’ journeys, students like Jorge can have an equitable opportunity to attain their postsecondary aspirations.

But reversing chronic divestment requires systematic in vestment. We must take action now. That will require parents and community members backing and supporting school board members who place a high priority on postsecondary attainment.

It will also require looking closely at their school or district’s strategies for promoting postsecondary success, and advocating for plans that provide all children with support to pursue higher education.

As we’ve seen so clearly over the last year, the people’s voice matters. I hope that people all around the country will rise up to demand that postsecondary preparation be integrated into all schools as a matter of equity, and look forward to the day when a postsecondary degree or credential is a right for all.

Lia Izenberg is the executive director of OneGoal Bay Area .

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

Share Article

Comments (2)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Daphne 3 years ago 3 years ago

As a high school teacher I have told my students that if I were graduating high school now, I would not go to 4 year college. It is not a guarantee to a good job anymore. Trade school and job experience are better investments, as is military service.

Robert Jaurequi 3 years ago 3 years ago

Excellent article!!!

EdSource Special Reports

Texas-style career ed: Ties to industry and wages

State funding for Texas State Technical College depends on graduates’ pay. Majors include robotics, welding, cybersecurity and cooking.

California eyes master plan to transform career ed

The goal is to support life-long learning at schools and workplaces.

Fewer than half of California students are reading by third grade, experts say. Worse still, far fewer Black and Latino students meet that standard. What needs to change?

For the four men whose stories are told in this documentary, just the chance to earn the degree made it possible for them to see themselves living a different life outside of prison.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

Everything You Need to Know About Getting a Post-Secondary Education

- By Emily Summers

- December 10, 2019

Are you about to graduate high school or have already graduated but are considering further studies for better employment opportunities? If so, then you might have heard the term “post-secondary education” every now and then.

As the name goes, post-secondary education takes place after you finish high school. And while most people see it as a stepping stone towards better employment opportunities in the future, this isn’t always necessarily the case. Also, contrary to popular belief, post-secondary education isn’t limited to college, so if money is a hindering factor for taking post-secondary education, you might want to consider the other options aside from college.

In this article, we define post-secondary education, what it means, and the various options available for you after your graduate high school (or high school equivalent). And then we tackle whether or not taking a post-secondary education really is important in the career path you want to take.

What Is Post-Secondary Education?

Secondary vs. post-secondary education, vocational schools, non-degree students, community colleges, colleges & universities, do i need post-secondary education for work.

Post-secondary education is also known as “higher education,” “third-level education,” or “tertiary education,” which all roughly mean the same thing. Its subtypes that don’t result in degrees like certificate programs and community college are also called “continuing education.” These refer to the educational programs you can take after graduating high school, get your GED, or anything similar to these in your country.

Unlike primary and secondary school that are mandatory for children under the age of 18, post-secondary education is completely optional. It is the final stage of formal learning and leads towards an academic degree. Post-secondary education is defined in the International Standard Classification of Education as levels 6 through 8. Post-secondary education also includes both undergraduate and postgraduate studies.

In the United States, plenty of high school students opt to take post-secondary education , with over 21 million students attending after high school. This is because many people see this as a ticket to economic security as having a higher education degree can be the key to opening more job opportunities in the market. While college is a type of post-secondary education, it is not the only form of tertiary education, though. And just because someone has completed their post-secondary education does not necessarily mean there will be job offers lined up for their choosing. Nor does it mean that they automatically earn more than a person who chose not to attend post-secondary education.

Secondary education is more commonly known as high school, but it can also refer to people who have taken their GED (General Education Development) tests or any equivalent around the world. Unlike post-secondary education, students are required to attend secondary school (or at least they are, until they turn 18 and can opt to drop out).

There are a number of people who choose to drop out ( around 527,000 people from October 2017 to October 2018). While it is possible for them to find work (around 47.2 percent of them), they cannot attend post-secondary education unless they finish high school or earn a secondary education diploma.

And while there are jobs available for those who didn’t get to finish secondary school or finished high school but opted not to attend post-secondary education, this closes some doors for them. For example, if you want to become a medical doctor , you cannot enter medical school until you earn a Bachelor’s degree by attending four years of college under an appropriate pre-med program. So, even if you got high grades in high school biology, no medical school is going to accept a student without a bachelor’s degree.

Post-Secondary Institutions

Contrary to popular belief, the term “post-secondary education” and its other similar terms aren’t limited to just earning a bachelor’s degree in high school. Colleges and universities are the most popular choice, but they may not be the most financially possible choice for everyone, especially if you consider that plenty of college graduates in the US are struggling to pay off student loan payments years after they’ve graduated college.

If you’re open to the idea of further education after high school but want to consider other options, here are your possible choices.

Also known as trade or tech schools, vocational schools teach it students on the technical side of certain crafts or skills of a specific job. Unlike colleges where its students receive academic training for careers in certain professional disciplines, vocational school students do job-specific training where certain physical skills are needed more than academic learning.

These are available in almost every country, though they may go by different names. In some countries, there may be both vocational schools run privately or public vocational school that are either fully or partially subsidized by the government for people who want to learn skills for better employment opportunities.

Some vocational courses include:

- Health care for nursing (for people who want to work as caregivers)

- Computer network management

- Word processing application (secretarial positions)

- Food and beverage management

- Fashion designing

- Electrician

- Commercial pilot

- Catering and hotel management

- Daycare management

- Hairstyling, cosmetics, and beautification

- Paralegal studies

- Massage therapy

- Pharmacy technician

- Travel agent

Take note that there are a lot more vocational courses than the ones provided, but not all vocational schools provide all types of courses. Some vocational schools may also specialize in certain industries, so it’s best to do your research on vocational schools in your area .

Completion of any of these courses provide you with a certificate that shows you have completed and trained for the skill of your choice. This gives you a competitive advantage in the job market compared to other high school graduates who do not have the same training for the skillset you have.

It is also possible to have multiple certificates for different courses if you think this will give you a further advantage, such as getting certified for Electrician, Plumber, and Carpentry courses if you intend to work in the construction industry. This also applies to college graduates who think they can get a leg up with both a college degree and a vocational school certificate on their resume.

There are two definitions of non-degree students . The first is a student who attends a college or university and attends undergraduate, master, or doctorate classes but not for the sake of earning a degree. These are people who may be interested in learning for specific classes and want to pursue academic interests but do not see the need to earn the full degree. These can be simply because they want to learn a certain field or who want to add to their resume that they took classes for a specific subject.

Another type of non-degree student are online or classroom programs on specific topics that can be used for resume-building skills or personal enrichment. You won’t earn a diploma, but you earn a certificate of completion. It’s similar to what you earn from tech school, but more academic than in terms of skill.

Community colleges are also known as “junior colleges” or “two-year colleges.” As its name goes, instead of earning a Bachelor’s degree after four years, community college students earn associate degrees after just two years . Some community colleges also offer non-degree certificates and vocational courses, though not all colleges do. Aside from academic classes, community colleges offer other programs for the community.

The reason why community colleges take half the time to earn a diploma is because it only offers the general education requirements taken by all college students. In regular colleges and universities, you spend four years studying: the first two years are dedicated to general education requirements, while the next two are for your specialized classes depending on your major.

Community college can be a step towards employment, but it can also be a step towards entering university. With the classes you’ve taken in community college, you can proceed to a university and major for two more years to work towards a bachelor’s degree. But if you think you don’t need one and intend to enter the workforce after attending community college, you’ll be given an associate’s degree after completion.

The most popular choice for post-secondary education, colleges and universities not only provide bachelor’s degree for high school students, but also post-graduate degrees for college students. Some examples of post-graduate degrees that fall under this bracket include graduate school, law school, medical school, dental school, and business school.

Some people attend post-secondary education institutions like graduate school and business schools for a master’s degree that will give them a leg-up in the job market for higher-ranking positions. However, for other institutions like law school and medical school, you need to enter and finish your education if you want to achieve a certain job role. For example, paralegals may need certification or even a bachelor’s degree, depending on how competitive a paralegal position in a law firm is, but if you want to become a lawyer, you need to finish to law school and pass the bar exam in your jurisdiction.

It’s relatively the most expensive form of post-secondary education, but there are several options on how to get in. There are several scholarship and grant programs that can provide you with partial to full scholarships (some even provide stipends or allowances for expenses like food, books, and other necessities) without having to go into debt. However, a lot of scholarship programs are extremely competitive and are usually awarded to students who show a lot of academic or athletic promise or require the most financial aid.

Getting post-secondary education is not necessary to land a job in the future, nor is there any assurance that getting further education will get you a job right after completing your education. If you feel like none of the options mentioned above can help you towards the career you want or see yourself doing in the future, then you don’t have to take any of them. Unlike elementary and secondary school in your younger years, post-secondary education isn’t mandatory – whether you attend school after high school or after the age of 18 is still your choice.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, almost 70% of high school graduates in 2018 between the ages of 16 to 24 enrolled to colleges or universities. And out of the 20 to 29-year-olds who received a college diploma, around 72% were employed. However, 74% of high school graduates were in the labor force (meaning they were working or actively looking for work), while 42% of high school drop outs were working.

This means that regardless of your educational attainment, there will be a position in the job market that will suit your educational attainment. However, depending on what that is, the job market could be competitive.

Also, take note of the salary difference. One of the possible reasons why over half of high school graduates opt to attend post-secondary education is because the average annual salary of a college graduate is over half the average annual salary of a high school graduate – and the gap between the two educational attainments is only growing wider.

However, some people don’t work for the paycheck alone and work because it’s something they want to do or they’re content with their job and the salary they earn. There is nothing wrong with this, especially if this means they choose a career path or job that allows them to do what they want.

Whether or not you should pursue post-secondary education is ultimately up to you. If you want a career that doesn’t necessarily fall under the available institutions or you feel like continuing education will do little to help your career, then it’s OK to skip this altogether and pursue a career or track that you want. But if you want to pursue continuing education but feel like you can’t afford to take four years of college, then you know that you have other options available that may help you.

About the Author

Emily summers.

What Is Fundraising and How Does It Work

Why Choosing Electrician Training Could Be Your Best Move

Tips for balancing technology and your child’s growth

Male and Female Cannabis Flowers Identifying the Differences

Debunking the Myth of Roberto Nevilis: Who Really Invented Homework?

Is the D Important in Pharmacy? Why Pharm.D or RPh Degrees Shouldn’t Matter

How to Email a Professor: Guide on How to Start and End an Email Conversation

Grammar Corner: What’s The Difference Between Analysis vs Analyses?

The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2023 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

Teaching Students About Morphological Awareness: Enhancing Literacy Skills

Teaching students about dave chappelle: a guide for educators, teaching students about the ionian sea: an enriching experience, teaching students about the santa clarita school shooting: a guide for educators, teaching students about the toyota previa: an innovative approach to automotive education, teaching students about super hero girls: empowering the next generation, teaching students about the iron curtain: a comprehensive guide, teaching students about tribes: enhancing cultural awareness and understanding, teaching students about age of bruce springsteen, teaching students about hotel pennsylvania: a journey through time and hospitality, post-secondary education: everything you need to know.

This is used to describe any type of education occurring after high school/secondary school. While post-secondary education isn’t mandatory, it offers added advantages because it helps students get additional education and develop various skills, which may increase their chances of securing higher-level employment. Students should also consider the salary difference. A significant percentage of high school graduates choose to receive post-secondary education because the mean annual salary of a college graduate is far better than that of a high school graduate.

Students planning to receive post-secondary education can choose from different types of post-secondary education institutions.

Colleges and universities: These are the two most sought-after choices for post-secondary education. Some students attend post-secondary education institutions, such as business schools and graduate schools, to earn a master’s degree that gives them a leg-up in the competitive job market. While colleges and universities are usually the most expensive forms of post-secondary education, several grants and scholarship programs are available that can help ease students’ financial burden.

Community colleges: By attending community colleges, students can earn an associate degree after two years. Some community colleges also offer vocational courses and non-degree certificates. Apart from academic classes, these colleges offer various programs for the community. It’s important to understand that community colleges take just two years to award an associate degree because they only offer general education courses that all college students must take. In four-year colleges and universities, students spend the first two years meeting the general education requirements and the next two years taking specialized classes depending on their majors.

Vocational schools: These schools teach students the technical sides of certain skills or crafts of a particular job. Unlike colleges that provide students with academic training to pursue careers in specific professional disciplines, vocational schools provide job-specific training where certain skills are prioritized over academic learning. While there’re many different types of vocational courses available, not all vocational schools provide all kinds of vocational courses. By completing any of these courses, a student receives a certificate that demonstrates they are trained for the skill of their choice. Students may also earn multiple certificates for multiple courses if they think it’ll give them a further advantage.

Apart from these, some students may choose to receive non-degree post-secondary education. Non-degree students are individuals who may be interested in learning a certain field and want to pursue academic interests but don’t want to earn a degree. By completing such a program, students can earn a certificate of completion instead of an associate’s degree.

21 Ways to Teach Kids to Take ...

Strategies to implement for children with learning ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point Admissions: Everything You Want to and Need to Know

The University of Alabama in Huntsville Admissions: Everything You Want to and Need to Know

Why diversity on college campuses matters to the real world.

Why HBCUs need alumni more than graduates (and financial literacy, too)

Nichols College Admissions: Everything You Want to and Need to Know

Western Carolina University Admissions: Everything You Want to and Need to Know

The Postsecondary Education Conundrum

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, cecilia elena rouse cecilia elena rouse @ceciliaerouse.

June 5, 2013

Postsecondary education in the United States faces a conundrum: Can we preserve access, help students learn more and finish their degrees sooner and more often, and keep college affordable for families, all at the same time? And can the higher education reforms currently most in vogue—expanding the use of technology and making colleges more accountable—help us do these things?

Since the 1960s, colleges and universities have worked hard to increase access to higher education. Fifty years ago, with the industrial economy booming—as Sandy Baum, Charles Kurose, and Michael McPherson write in the latest issue of the Future of Children —only 45 percent of young people went to college when they graduated from high school. Today, they note, at least 70 percent enroll in some form of postsecondary education. Women, who once accounted for little more than a third of the college population, now outnumber men on campus, and minorities and the poor have also seen many barriers to a college education fall. Certainly, we still have work to do—for example, advantaged children are still much more likely than children living in poverty to go to college, and to attend elite institutions when they do. Yet the gains in access have been remarkable.

Over the past decade, critics have increasingly questioned the quality of college education in the U.S. In particular, they have pointed to low completion rates—only about half of the people who enroll at a postsecondary institution complete a degree or certificate within six years. Yes, there are many reasons that students attend such institutions, but even among those who report that they aspire to earn at least a bachelor’s degree, only about 36 percent do so.

Most recently, the loudest debates in higher education have been about cost. When people talk about the cost of postsecondary education, they usually mean tuition. The most alarming recent increases have been in the “sticker price,” or the published cost of attending an institution. Sticker prices for full-time in-state students at public four-year colleges and universities increased 27.2 percent between 2007 and 2012, according to the College Board. But only about one-third of full-time students pay the sticker price; the other two-thirds of full-time students pay the “net price,” which is the sticker price minus grants and other forms of aid. On average, the net price is 70 percent less than the sticker price. Even so, the net price of college has also increased steeply, by 18 percent over the same five years.

Many people take the sharp rise in tuition costs as evidence that institutions of higher education are inefficient and growing more so—in other words, that colleges and universities are spending more and more money to deliver the same education. They argue that if we aggressively adopt technology and strengthen accountability, we can make colleges and universities more efficient, whether that means providing the same education for less money, or a better education for the same cost.

But, in truth, tuition—whether we’re talking about sticker price or net price—doesn’t really tell us how much a college education costs. As McPherson, who is president of the Spencer Foundation, pointed out recently at a conference at Princeton, an institution’s total expenditure per student is a much better measure of the cost of a college education. Based on 2012 data from the College Board, expenditures per student, especially at public institutions, have been relatively flat over the past decade, increasing by about 6.4 percent at four-year public institutions and actually decreasing at two-year public institutions. Tuition itself accounts for only a part of the total expenditure per student. At public institutions in particular, the rest is made up largely by state subsidies. What has changed in recent years is that state subsidies have fallen precipitously, meaning that parents and students are shouldering more of the cost through rising tuition payments. From 2000 to 2010, the portion of total expenditures covered by tuition at public institutions went from just over one-third to just over one-half, with subsidies falling accordingly. If we look at the cost of college this way, it’s unlikely that growing inefficiency is the main problem facing institutions of higher education; in fact, they are educating more students than ever and doing so at roughly the same cost per student. Nonetheless, few people expect state subsidies to rebound to their former levels. If college is to remain affordable, state institutions must seek ways to lower their cost per student so that they can keep tuition in check.

What are the prospects, then, that technology and accountability can help us rein in the rate of growth in tuition? Unfortunately, the answer isn’t clear.

Policymakers like to focus on advances in technology as a solution for the tuition crisis because a major component underlying the cost of a postsecondary education is the cost of paying the faculty. As long as the wages that faculty members could earn in other parts of the economy continue to increase, there will be upward pressure on the cost of educating students. But if we could use advanced technology to let each faculty member teach more students, we could lower the cost of a college education. However, no one wants such an increase in productivity to reduce the quality of the education that students receive. Therefore, if technology is to help us solve higher education’s quandary, it must provide education at a lower cost without lowering its quality.

We have scant evidence of whether e-learning is comparable in quality to traditional classroom instruction. However, the best research so far suggests that in large lecture classes, at least, especially those that cover introductory material in some subjects, students learn just as well online as they do in “chalk and talk” classes. We know even less about the long-term cost of teaching in this way. On the one hand, once we pay the start-up and transition costs associated with adopting new technology and training faculty how to use it, the cost per student is likely to fall because faculty will be able to teach more students in larger classes. On the other hand, the best evidence about technology comes from its use in large lecture classes; we know much less about its effectiveness in smaller, typically more advanced courses, which are more expensive to teach by definition. We also have virtually no evidence about technology’s effectiveness in some disciplines, particularly the humanities. If technology can’t deliver the same education that students get in the classroom, what may look like a decrease in cost may actually be a decrease in quality. Thus before we know whether widespread adoption of technological tools is truly a promising approach to reducing the cost of a college education, we need more and better evidence about how these tools affect student learning, in which settings and for whom they work best, and how much they cost to implement and maintain.

Accountability

Policymakers are also talking about accountability as a way out of the postsecondary conundrum. Most public institutions receive state subsidies based on the number of students they enroll. Enrollment-based funding gives these colleges and universities a huge incentive to increase access, but far less incentive to boost completion rates and other measures of student success. On the heels of the movement to increase accountability in K-12 education, a lot of people, including President Obama, have been calling to make colleges and universities more accountable, most notably by tying some portion of state or federal funding to student completion or other measures of success—for example, how many graduates find jobs. Many states have already tried this, but the results have been disappointing (though it must be said, as Davis Jenkins and Olga Rodriguez write in the Future of Children , that much of the research on performance funding thus far has been qualitative rather than quantitative). One reason that performance funding hasn’t worked well may be that the percentage of aid that states have tied to performance has been quite low, meaning that institutions have had little to lose if they fail to meet performance targets. As a result, some reformers are calling for an even stronger connection between funding and accountability. Fair enough, and probably worth a try, but the bottom line is that we have yet to find solid evidence that tying appropriations to student success will produce the results we desire. And caution is in order: Unless such an approach is implemented and monitored carefully, it will create a perverse incentive for institutions to restrict admission to the students who are most likely to do well, thus potentially reversing the gains in access that we’ve worked so hard to achieve.

Despite the caveats I’ve presented here, I believe that both technology and accountability have their place in any effort to solve the postsecondary conundrum.

In the case of new technological tools to expand teaching productivity, we need to carefully study their effect on student learning, institutional stability, educational quality, and cost. It’s going to take some tinkering to build new models of technology-supported teaching that work as well as or better than a traditional classroom education, and we should not hesitate either to try promising approaches or to abandon those that fail to make the grade.

When it comes to imposing stronger accountability, we need comprehensive data systems and other ways to gather information that will give us a clearer, more scientifically sound picture of institutional performance than do the rough measures we use now, such as completion rates. Furthermore, measures of quality should never be the only criteria through which we reward or punish postsecondary institutions, not only because expanding access must remain a priority, but also because it is extremely unlikely that we will ever be able to capture all of postsecondary education’s beneficial outcomes through large-scale data.

In the end, however, technology and accountability alone will not solve the postsecondary conundrum. As tuition costs rise, parents and prospective students are starting to question the value of the postsecondary institutions they’re considering, seeking better information about quality and completion rates, and making decisions based on hard financial realities. This kind of pressure from prospective students and their families is likely to be the most effective incentive of all.

Higher Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Carly D. Robinson, Katharine Meyer, Susanna Loeb

June 4, 2024

Monica Bhatt, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig

June 3, 2024

Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Max Lieblich, Sophie Partington, Rebecca Winthrop

May 31, 2024

- Sign in to Community

- Discuss your taxes

- News & Announcements

- Help Videos

- Event Calendar

- Life Event Hubs

- Champions Program

- Community Basics

Find answers to your questions

Work on your taxes

- Community home

- Discussions

AOC. Did you complete the first four academic years of your post-secondary education before ....?

Do you have a turbotax online account.

We'll help you get started or pick up where you left off.

- Mark as New

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Report Inappropriate Content

- ItsDeductible Online

Do you have an Intuit account?

You'll need to sign in or create an account to connect with an expert.

View solution in original post

Still have questions?

Get more help

Ask questions and learn more about your taxes and finances.

Related Content

Can a Pell Grant be carried forward for future year educational expenses

Running Start and American Opportunity Credit

How do I force TurboTax to use the Lifetime Learning Credit instead of the American Opportunity Credit for my student?

Lifetime learning Credit eligibility

help needed on scholarship income and QTP

Did the information on this page answer your question?

Thank you for helping us improve the TurboTax Community!

Sign in to turbotax.

and start working on your taxes

File your taxes, your way

Get expert help or do it yourself.

Access additional help, including our tax experts

Post your question.

to receive guidance from our tax experts and community.

Connect with an expert

Real experts - to help or even do your taxes for you.

You are leaving TurboTax.

You have clicked a link to a site outside of the TurboTax Community. By clicking "Continue", you will leave the Community and be taken to that site instead.

Advertisement

First 4 Years in Canada: Post-secondary Education Pathways of Highly Educated Immigrants

- Published: 14 December 2010

- Volume 12 , pages 61–83, ( 2011 )

Cite this article

- Maria Adamuti-Trache 1

1232 Accesses

23 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper addresses issues relevant to the socioeconomic integration of highly educated immigrants in Canada by undertaking a secondary analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada. It illustrates the promptness of immigrants’ participation in further post-secondary education (PSE) in Canada within the first 4 years of arrival and proposes a typology of PSE pathways to examine individual, situational, dispositional and immigrant-specific factors that determine adult immigrants’ choices. The Canadian immigrant experience involves the interplay between structural constraints and agency to shape individualized pathways along which newcomers use existing human capital to create new forms of human capital (Canadian credentials) as a strategy to improve their employment opportunities.

Cet article utilise les données provenant de l’Enquête longitudinale auprès des immigrants du Canada (ELIC) ayant comme but d’examiner les contraintes de l’intégration socio-économique des immigrants très instruits. L’étude montre que presque la moitié de tous les immigrants adultes s’inscrivent dans un établissement d’enseignement postsecondaire canadien au cours des quatre premières années suivant leur arrivée. L’analyse des voies d’accès à l’éducation postsecondaire (EPS) révèle les conditions personnelles et situationnelles influençant la participation et le choix des immigrants adultes. L’expérience des nouveaux immigrants au Canada exemplifie l’interaction entre l’action d’agents et les contraintes structurelles dont le résultat est des trajectoires individualisées; au long de leur trajectoire professionnelle, les immigrants utilisent leur capital humain pour créer de nouvelles formes de capital humain et symbolique (les qualifications canadiennes) comme stratégie pour améliorer leur chance de trouver un emploi.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Back to school in a new country the educational participation of adult immigrants in a life-course perspective.

Educational Trajectories and Transition to Employment of the Second Generation

International students, immigration and earnings growth: the effect of a pre-immigration host-country university education.

As described by Bourdieu ( 1990 ), habitus comprises a complex set of structures, habits and dispositions that orient and, in some cases compel, individuals to make choices, including PSE destinations.

The sample reduction occurred at each level of selection. About 54% of the LSIC population had university education, about 73% were 25 to 49 years of age and about 91% had no previous contact with Canada before immigration.

First, LSIC has a complex sample design that requires the researcher to account for the stratification and clustering of the sample by employing bootstrap weighting procedures. Statistics Canada provides a bootstrap weights file, and the current analysis employs 500 bootstrap replicate weights. Second, results are presented according to Statistics Canada requirements (counts are rounded to the nearest tens; means and proportions are rounded to the nearest tenth).

The main economic group exhibits the characteristics of skilled worker principal applicants because provincial nominees are only 2.8% of the entire sample.

Adamuti-Trache, M. (2010). Is the glass half empty or half full? Obstacles and opportunities that highly educated immigrants encounter in the segmented Canadian labour market. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia . Available at: https://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/19775

Adamuti-Trache, M., & Sweet, R. (2005). Exploring the relationship between educational credentials and the earnings of immigrants. Canadian Studies in Population, 32 (2), 177–201.

Google Scholar

Adamuti-Trache, M. & Sweet, R. (2010). Adult immigrants’ participation in Canadian education and training. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education , 22 (2), 1–26.

Anisef, P., Sweet, R., & Adamuti-Trache, M. (2009). Impact of Canadian PSE on recent immigrants’ labour market outcomes. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/research/impact_postsecondary.asp

Association of Canadian Community Colleges (2006). The economic contribution of Canada’s community colleges and technical institutes: An analysis of investment effectiveness and economic growth. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://www.accc.ca/ftp/pubs/studies/CCBenefits/main_report.pdf

Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (2007). Trends in higher education: Volume 1—enrolment. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://www.aucc.ca/_pdf/english/publications/trends_2007_vol1_e.pdf

Aydemir, A., & Skuterud, M. (2004). Explaining the deterioration entry earnings of Canada’s immigrant cohorts: 1966–2000. Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE . Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice . Cambridge: Polity.

Canadian Council on Learning. (2007). Post-secondary education in Canada: Strategies for success . Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://www.ccl-cca.ca/NR/rdonlyres/25B8C399-1EA3-428A-81A1-C8D8206E83C6/0/PSEFullReportEN.pdf

Cross, K. P. (1981). Adults as learners. Increasing participation and facilitating learning (1992nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspective on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57 (10), 4–15.

Evans, K. (2007). Concepts of bounded agency in education, work, and the personal lives of young adults. International Journal of Psychology, 42 (2), 85–93.

Article Google Scholar

Ferrer, A., & Riddell, C. (2008). Education, credentials, and immigrant earnings. Canadian Journal of Economics, 41 (1), 186–216.

Ferrer, A., Green, D. A., & Riddell, W. C. (2004). The effect of literacy on immigrant earnings. Catalogue no. 89-552-MIE . Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Frenette, M., & Morissette, R. (2003). Will they ever converge? Earnings of immigrant and Canadian-born workers over the last two decades. Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE . Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Galarneau, D., & Morissette, R. (2004). Immigrants: Settling for less? Perspectives on Labour and Income, 5 (6), 5–16.

Galarneau, D., & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrant’s education and required job skills. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 9 (12), 5–18.

Girard, E., & Bauder, H. (2007). Assimilation and exclusion of foreign trained engineers in Canada: Inside a Canadian professional regulatory organization. Antipode, 39 (1), 35–53.

Green, A. G., & Green, D. A. (1999). The economic goals of Canada’s immigration policy. Canadian Public Policy, 25 , 425–451.