Time-In-Cell : Isolation and Incarceration

What is solitary confinement, and what has been constitutional law’s relationship to the practices of holding prisoners in isolation? One answer comes from Wilkinson v. Austin , 1 a 2005 U.S. Supreme Court case discussing Ohio’s super-maximum security (“supermax”) prison, which opened in 1998 to hold more than five hundred people.

Writing for the unanimous Court in Wilkinson , Justice Kennedy detailed a painful litany of conditions. 2

[A]lmost every aspect of an inmate’s life is controlled and monitored. Inmates must remain in their cells, which measure 7 by 14 feet, for 23 hours per day. A light remains on in the cell at all times . . . and an inmate who attempts to shield the light to sleep is subject to further discipline . . . .

Incarceration [in supermax] is synonymous with extreme isolation. In contrast to any other Ohio prison . . . [the] cells have solid metal doors with metal strips along their sides and bottoms which prevent conversation or communication with other inmates. All meals are taken alone . . . . Opportunities for visitation are rare . . . . It is fair to say [that] inmates are deprived of almost any environmental or sensory stimuli and of almost all human contact . . . . [P]lacement . . . is for an indefinite period of time, limited only by an inmate’s sentence. 3

The specifics were in service of meeting the exacting test that the Court had crafted about when constitutional law has a role to play in protecting prisoners. In an earlier case, Sandin v. Conner , the Supreme Court held that a prisoner could challenge his placement in segregation only if the change worked an “atypical and significant hardship” which, thereby, infringed a prisoner’s liberty interests and triggered due process obligations under the Fourteenth Amendment. 4

In Wilkinson , the Court concluded that placement in Ohio’s supermax qualified as a significant hardship, since “almost all human contact [was] prohibited, even . . . conversation . . . from cell to cell.” 5 Nonetheless, the Court held that Ohio’s procedures sufficed to buffer against “arbitrary decisionmaking.” 6 The approved procedures included an in-person hearing that the prisoner can attend; the provision of a written “brief summary of the factual basis for the classification;” “a rebuttal opportunity” at two levels of internal review (each authorized to reject the placement); “a short statement of reasons;” and another review thirty days after the initial placement. 7 The Wilkinson Court thus required some process but did not discuss whether subjecting individuals to such conditions was itself constitutionally impermissible.

Ten years after Wilkinson , Justice Kennedy returned to the topic of solitary confinement in a 2015 concurrence in Ayala v. Davis . 8 Justice Kennedy noted that Hector Ayala, who had been sentenced to death in 1989, had spent most of “his more than 25 years in custody in ‘administrative segregation’ or, as it is better known, solitary confinement.” 9 If following “the usual pattern,” Mr. Ayala had been held for decades “in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day . . . [and] allowed little or no opportunity for conversation or interaction with anyone.” 10

Relying on data collected in the late 1990s, Justice Kennedy observed it was likely that about “25,000 inmates in the United States” were living in such conditions, “many regardless of their conduct in prison.” 11 Justice Kennedy called for more “public inquiry or interest” in prisons. And in a vivid protest, he suggested that when imposing a capital sentence, a judge tell such a defendant that “during the many years you will serve in prison before your execution, the penal system has a solitary confinement regime that will bring you to the edge of madness, perhaps to madness itself.” 12

Justice Kennedy raised the prospect that solitary confinement violated substantive constitutional rights. 13 “[T]he judiciary may be required . . . to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.” 14 Within a month, Justice Kennedy’s distress was echoed by Justice Breyer, who joined by Justice Ginsburg, condemned the “dehumanizing effect of solitary confinement;” their dissent in Glossip v. Gross argued the unconstitutionality of the death penalty. 15

When these Justices were writing, the question of the constitutionality of profound isolation was en route to the Court in a certiorari petition on behalf of Alfredo Prieto. 16 Under Virginia’s policy that offenders “sentenced to Death will be assigned directly to Death Row,” 17 Prieto was automatically placed in conditions that a federal district court judges described as “eerily reminiscent” 18 of those in Wilkinson v. Austin . Prieto argued that Wilkinson required an individualized determination of the need for such segregation. 19 Over a dissent, the Fourth Circuit rejected that claim: Imprisonment in conditions that the trial court had found to be “dehumanizing” and “undeniably severe” did not rise to a constitutional violation. 20 Former corrections officials and mental health professionals urged the Court to take up the question and detailed the harms of isolation and the alternatives available. 21 But the petition became moot when, on October 1, 2015, Virginia executed Mr. Prieto. 22

Such potential for developments in the law on isolation cannot be understood in isolation, for the legitimacy and legality of solitary confinement is under siege in several quarters. The source of the growing distress comes in part from the chilling description provided in Wilkinson , written as the post-9/11 detention of hundreds of people at Guantánamo Bay made visible the starkness of totalizing control. Detainees there and prisoners in California’s supermax at Pelican Bay mounted protests, including hunger strikes. 23 By 2010, the ACLU’s National Prison Project had launched its “Stop Solitary” campaign, producing reports of horrific conditions for thousands of prisoners held in Texas and in “the box” in New York State. 24 As suicides and violence brought media attention to the suffering and deaths, 25 the Vera Institute worked with prison officials to create alternatives. 26

The Supreme Court has not yet faced Justice Kennedy’s substantive constitutional question, and lower courts have rejected some claims by individuals held for decades in isolation. 27 Yet a few courts have concluded that placement of seriously mentally ill individuals in isolation is unconstitutional. 28 Further, within the past two years, courts have approved settlements in class actions in Arizona, California, and Pennsylvania, each focusing on subsets of detainees such as the seriously mentally ill, juveniles, or individuals with disabilities, and specifying the predicates to and limits on the use of isolation. 29

Legislators have likewise weighed in. In some states, including Colorado and Massachusetts, have imposed limits on isolation for the mentally ill. 30 On the federal level, Senators Chuck Grassley, Richard Durbin, John Cornyn, Sheldon Whitehouse, Mike Lee, Chuck Schumer, Lindsey Graham, Patrick Leahy, and Corey Booker have joined forces to co-sponsor new legislation, a Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, proposing a sharp curtailment of isolation for the few juveniles in the federal system. 31

The developments in the United States need also to be placed in a transnational context. In the spring of 2015, proposed U.N. provisions (aptly styled the Mandela Rules and drafted with input from U.S. correctional leaders) defined confinement of prisoners for twenty-two hours or more per day for a period exceeding fifteen days to be “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.” 32 The rules call for banning isolation of vulnerable prisoners, limiting isolation’s use to exceptional circumstances, and ensuring visiting opportunities for those in isolation. 33

Yet to look only at pressures from outside prisons is to miss the action within . During the last few years, directors of several state prison systems revamped their policies to constrain the use of isolation. 34 Their national organization, the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA)—whose members are the directors of state and federal prison systems—chartered a special committee on the topic and adopted best practices. 35 In the fall of 2015, ASCA issued a statement that prolonged isolation represents a “grave problem” and called for its reduction or elimination. 36 In January of 2016, the American Correctional Association will hold hearings on its new proposed standards for “restricted housing” that, likewise, reflect prison leaders efforts to set limits on the use of isolation.

To know if this sense of urgency and the many cris de coeur from across the political spectrum will have a transformative effect requires a baseline. The questions are whether the “usual pattern” that Justice Kennedy described (placement in windowless parking-lot size cells for twenty-three hour days) are commonplace; how many people live under such conditions; the criteria for entry and exit; and whether the degrees of isolation vary. Answers come from two reports, Administrative Segregation, Degrees of Isolation, and Incarceration: A National Overview of State and Federal Correctional Policies , published in 2013 , 37 and Time-In-Cell: The ASCA-Liman 2014 National Survey of Administrative Segregation in Prison , released in the fall of 2015, both of which were based on research jointly sponsored by ASCA and Yale Law School’s Liman Project. 38

The goals of the reports were to create a shared understanding of isolation and to enable cross-jurisdictional comparisons on rules and practices. The challenges of doing so came from the array of terms and rules governing what is variously called “administrative confinement,” “administrative segregation,” “close supervision,” “behavior modification,” “departmental segregation,” “enhanced supervision housing” (ESH), “inmate segregation,” “intensive management,” “special management unit” (SMU), “security (or special) housing units” (SHU), “security control,” and “maximum control units.” Such placements are predicated on one of three reasons - discipline, protection, or generic fears that a prisoner will cause harm.

Given this array, we—Liman and ASCA–began by focusing on a subset of the governing rules; in 2012 we asked directors of state and federal corrections systems, to provide their policies on “administrative segregation,” defined as removing a prisoner from general population to spend twenty-two to twenty-three hours a day in a cell for thirty days or more. The resulting 2013 Report, based on responses from forty-seven jurisdictions, taught us that at the formal level of policies, getting into segregation was relatively easy, but few policies focused on getting people out.

The criteria for entry were broad. Many jurisdictions permitted moving a prisoner into segregation if that prisoner posed “a threat” to institutional safety or a danger to “self, staff, or other inmates.” 39 Constraints on decision-making were minimal; the kind of notice provided and what constituted a “hearing” varied substantially. 40 The hopes expressed in 2005 in Wilkinson v. Austin —that minimal due process safeguards would suffice to buffer against arbitrariness—did not appear to be reflected in the policies, which invested prison officials with enormous discretion.

In 2014, the Liman Program and ASCA took the next step by asking prison directors more than 130 questions—this time about the people in restricted housing and the conditions in which they lived. Responses came from forty-six jurisdictions (albeit not all jurisdictions answered all the questions). The result— Time-In-Cell —offers a unique interjurisdictional window into segregation. We summarize some of its findings below.

A basic question is the number of prisoners in isolation. In the 2015 Ayala concurrence, Justice Kennedy cited the figure of 25,000 by relying on research about supermax facilities from the late 1990s. But we tallied 66,000 prisoners in thirty-four jurisdictions in restricted housing in 2014, and those prison systems housed about 73% of the 1.5 million people incarcerated in U.S. prisons. Extrapolating, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 people were in such segregation in 2014, or about one in every six or seven prisoners. And neither the reports from the 1990s nor ours included people in local jails, juvenile facilities, or in military and immigration detention.

Time-In-Cell also focused on conditions in administrative segregation. While the numbers of people are much higher than the figure Justice Kennedy mentioned in Ayala , the pictures he painted in 2005 and in 2015 are not out-of-date but mirror prisoners’ current experiences. The cells are small, ranging from 45 to 128 square feet, sometimes for two people. In the majority of jurisdictions, prisoners spend twenty-three hours in their cells on weekdays and forty-eight hours straight on weekends. In many of the systems reporting, blacks and Hispanics were over-represented in isolation, when compared to the prison population in general.

Opportunities for social contact, such as out-of-cell time for exercise, visits, and programs, are limited, ranging from three to seven hours a week in many jurisdictions. Phone calls and social visits could be as infrequent as once per month; a few jurisdictions provided more opportunities. The reminder is that what we could chronicle was the potential for social contact and activities. But in most jurisdictions, prisoners’ access to social contact, programs, exercise, as well as what prisoners were allowed to keep in their cells could be limited as sanctions for misbehavior.

Administrative segregation generally had no fixed endpoint. Further, several systems did not keep track of the numbers of continuous days that a person remained in isolation, and in the twenty-four jurisdictions reporting on this question, a substantial number indicated that prisoners were in segregation for more than three years. As to release and reentry, in thirty jurisdictions tracking the numbers in 2013, a total of 4,400 prisoners went directly from the isolation of administrative segregation to release in the community.

Unsurprisingly, the running of administrative segregation units posed many challenges for prison systems, and the problems – coupled with the surge of concerns – have created incentives for change. Some jurisdictions required staff to have additional training and offered flexible schedules, rotations, or provided extra benefits for the assignment. Further, prison directors also cited prisoner and staff wellbeing, pending lawsuits, and costs as reasons to revise their rules. A few directors added that change was important because it “is the right thing to do.”

As noted, the ASCA-Liman Report relies on answers from those who run prisons. In the fall of 2015, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) released a survey drawn from another source—prisoners. 41 Based on responses during 2011-2012 from 91,177 inmates in 233 state and federal prisons and in 357 jails, BJS found that almost 20 percent of those detainees had been held in restricted housing within the prior year. 42 The individuals more likely to have been placed in restricted housing were younger, lesbian, gay, bisexual, or mentally ill, and without a high school diploma. 43 The BJS study found that expansive use of restrictive housing correlated with institutional disorder, such as gang activity and fighting, rather than with calmer environments. 44

Time-In-Cell provides both a window into the pervasive use of isolation and a baseline from which to assess whether the many efforts to limit isolation will have an impact. The practices of isolation have become entrenched in the past forty years; unraveling them will require intensive work. The twin questions on the ground are whether the number of persons held in such settings is diminishing and whether the conditions in which they live are less isolating. And coupled with Wilkinson , Ayala , and Prieto , Time-In-Cell should prompt inquiry into why this form of confinement has not already been understood to be unconstitutional.

Judith Resnik is the Arthur Liman Professor of Law, Sarah Baumgartel is the Senior Liman Fellow in Residence, and Johanna Kalb is a Visiting Associate Professor of Law and the Director of the Liman Program at Yale Law School. All rights reserved. Thanks are due to the Yale Law Journal Forum under the guidance of Michael Clemente; to current and former Yale Law students Corey Guilmette, Devon Porter, Josh Nuni, and Diana Li; to George and Camille Camp, A.T. Wall, Gary Mohr, Rick Raemisch, and Bernie Warner of ASCA; to Denny Curtis, David Fathi, and Hope Metcalf; and to the many other people in and outside prisons working to change conditions of confinement.

Preferred Citation: Judith Resnik, Sarah Baumgartel & Johanna Kalb, Time-In-Cell : Isolation and Incarceration , 125 Yale L.J. F. 212 (2016), http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/time-in-cell-isolation-and-incarceration.

Volume 133’s Emerging Scholar of the Year: Robyn Powell

Announcing the eighth annual student essay competition, announcing the ylj academic summer grants program, this essay is part of a collection, reactions to time-in-cell.

These essays respond to Time-In-Cell , a report based on research jointly sponsored by the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA) and by the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program at Yale Law School. For more information on the release of the report, please click here .

Only Once I Thought About Suicide

Worse than death, staying alive: reforming solitary confinement in u.s. prisons and jails, the liman report and alternatives to prolonged solitary confinement, time-in-cell : a practitioner’s perspective.

545 U.S. 209 (2005).

Id. at 223-24.

Id. at 214-15.

Sandin v. Conner, 515 U.S. 472, 483-84 (1995).

Wilkinson , 545 U.S. at 227.

Id. at 224-226.

Davis v. Ayala, 135 S. Ct. 2187, 2208 (2015) (Kennedy, J., concurring). That decision rejected a habeas petitioner’s claim that the exclusion of his lawyer from a hearing about racially prejudiced jury selection violated his constitutional rights.

Id. at 2208-09 (citing Entombed: Isolation in the U.S. Federal Prison System , Amnesty Int’l 2 n.3 (July 2014), http://www.amnestyusa.org/sites/default/files/amr510402014en.pdf [http://perma.cc/CYD4-4DPT]). The Amnesty International report relied on the article by Daniel P. Mears, A Critical Look at Supermax Prisons , Corrections Compendium , Sept.-Oct. 2005, which in turn used research from the late 1990s. See also Daniel P. Mears, Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons , Urb. Inst. 4, app. 74 tbl.1 (Mar. 2006), http://www.urban.org/research/publication/evaluating-effectiveness-supermax-prisons [http://perma.cc/AT77-HPZ2] (including a chart borrowed from Roy D. King that identified states in 1997-1998 that had supermax facilities).

Davis , 135 S. Ct. at 2209.

Id . The constitutional predicates include that such confinement violates the Eighth Amendment by imposing serious harms or denying basic needs to which prison officials were deliberately indifferent. See Wilson v. Seiter, 501 U.S. 294 (1991).

During the past few decades, a few lower courts have declined to hold long-term isolation unconstitutional, but the law has been shifting since those rulings. Further, given that Eighth Amendment law is sometimes predicated on the obligation to protect a person’s dignity, see, e.g. , Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 (1958), and given Justice Kennedy’s identification of dignity as central to the substantive meaning of due process and to equal protection, see, e.g. , Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584, 2597 (2015), challenges to isolation can be focused on the deprivations of dignity that solitary confinement imposes. See generally Laura L. Rovner, Dignity and the Eighth Amendment: A New Approach to Challenging Solitary Confinement (Univ. of Denver Sturm Coll. of Law, Working Paper No. 15-55, 2015), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2675228 [http://perma.cc/K73K-VMQ4]. In addition, statutory claims include violations of the Americans with Disability Act. See Brittany Glidden & Laura Rovner, Requiring the State To Justify Supermax Confinement for Mentally Ill Prisoners: A Disability Discrimination Approach , 90 Denver U. L. Rev. 1 (2012).

Davis , 135 S. Ct. at 2210.

Glossip v. Gross, 135 S. Ct. 2726, 2765 (2015) (Breyer, J., dissenting, joined by Ginsburg, J.).

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Prieto v. Clarke, 2015 WL 4100302 (2015) (No. 15-31), cert. dismissed , 2015 WL 4105028 (2015).

Va. Dep’t of Corr. Operating Procedure 830.2(D)(7), 460.A, CAJA-941 (2015).

Prieto v. Clarke, 780 F.3d 245, 248 (4th Cir. 2015) (quoting Prieto v. Clarke, No. 12–1199, 2013 WL 6019215, at *6 (E.D. Va. Nov. 12, 2013), cert. dismissed , 2015 WL 4105028 (2015)).

Prieto , 2015 WL 4100302, at *2.

Id. at 254-55. Judge Wynn, dissenting, rejected the view that “Prieto’s automatic, permanent, and unreviewable placement” was constitutional. Id. at 255-56.

See Brief of Amici Curiae Corrections Experts in Support of Petitioner, Prieto v. Clarke, 2015 WL 4720277, at *7 (2015) (No. 15-31); Brief of Amici Curiae Professors and Practitioners of Psychiatry and Psychology in Support of Petitioner, Prieto v. Clarke, 2015 WL 4720278 (2015) (No. 15-31).

Prieto , 2015 WL 4105028 (dismissing the petition for certiorari); see also Associated Press, Appeals Exhausted, Alfredo Prieto, Serial Killer, Is Executed , N.Y. Times (Oct. 1, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/02/us/appeals-exhausted-alfredo-prieto-serial-killer-is-executed.html [http://perma.cc/4VEB-FNZ6].

See Neil A. Lewis, Guantánamo Prisoners Go on Hunger Strike , N.Y. Times (Sept. 18, 2005), http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/18/politics/guantanamo-prisoners-go-on-hunger-strike.html [http://perma.cc/BY7Q-Z56U]; Ian Lovett, Hunger Strike by Inmates Is Latest Challenge to California’s Prison System , N.Y. Times (July 7, 2011), http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/08/us/08hunger.html [http://perma.cc/6PDJ-J6YJ].

See Burke Butler, Matthew Simpson & Rebecca L. Robertson, A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas , ACLU Texas (2015), http://www.aclutx.org/2015/02/05/a-solitary-failure [http://perma.cc/2LMB-BM99]; Scarlet Kim, Taylor Pendergrass & Helen Zelon, Boxed In: The True Cost of Extreme Isolation in New York’s Prisons , N.Y. Civil Liberties Union (2012), http://www.nyclu.org/files/publications/nyclu_boxedin_FINAL.pdf [http://perma.cc/T2G9-PEXY].

See, e.g. , Kevin Johnson, More Than a Decade After Release, They All Come Back , USA Today (Nov. 4, 2015), http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/11/04/solitary-confinement-prisoners-impact/73830286 [http://perma.cc/G9AS-RM5V]; Michael Schwirtz & Michael Winerip, Kalief Browder, Held at Rikers Island for 3 Years Without Trial, Commits Suicide , N.Y. Times (June 8, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/09/nyregion/kalief-browder-held-at-rikers-island-for-3-years-without-trial-commits-suicide.html [http://perma.cc/475A-KXY6]; Erica Goode, Solitary Confinement: Punished for Life , N.Y. Times (Aug. 3, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/04/health/solitary-confinement-mental-illness.html [http://perma.cc/WFZ4-D5TT].

Alison Shames, Jessa Wilcox & Ram Subramanian, Solitary Confinement: Common Misconceptions and Emerging Safe Alternatives , Vera Inst. Just. (May 2015), http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/solitary-confinement-misconceptions-safe-alternatives-report.pdf [http://perma.cc/U8T7-B9MB].

See, e.g. , Silverstein v. Bureau of Prisons, 559 F. App’x 739 (10th Cir. 2014).

See Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D. Cal. 1995); Jones’El v. Berge, 164 F. Supp. 2d 1096 (W.D. Wis. 2001). See generally Elizabeth Alexander, “This Experiment, So Fatal”: Some Initial Thoughts on Strategic Choices in the Campaign Against Solitary Confinement , 5 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 1 (2015).

Stipulation, Parsons v. Ryan, No. CV 12-00601-PHX-DJH (D. Ariz. Oct. 14, 2014), ECF No. 1185; Settlement Agreement, Ashker v. Gov. of Cal., No. C 09-05796 CW (N.D. Cal. Sept. 1, 2015), ECF No. 424-2; Settlement Agreement, Disability Rights Network of Pa. v. Wetzel, No. 1:13-cv-006535-JEJ (M.D. Pa. Jan. 9, 2015), ECF No. 59.

See Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 17-1-113.8(1) (West 2015); Mass. Gen. Laws Ann ch. 127 § 39A(b) (West 2015).

S. 2123, 114th Cong. § 212 (2015).

U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela Rules), U.N. Econ. & Soc. Comm. on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, 24th Sess., U.N. Doc. E/CN.15/2015/L.6/Rev.1 (May 21, 2015), http://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CCPCJ/CCPCJ_Sessions/CCPCJ_24/resolutions/L6_Rev1/ECN152015_L6Rev1_e_V1503585.pdf [http://perma.cc/VTV5-DFT9].

See Erica Goode, After 20 Hours in Solitary, Colorado’s Prisons Chief Wins Praise , N.Y. Times (Mar. 15, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/us/after-20-hours-in-solitary-colorados-prisons-chief-wins-praise.html [http://perma.cc/X392-SQ6T] (reporting Colorado’s change to “sending inmates to solitary confinement for specific lengths of time instead of indefinite periods”); Timothy Williams, Prison Officials Join Movement To Curb Solitary Confinement , N.Y. Times (Sept. 2, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/03/us/prison-directors-group-calls-for-limiting-solitary-confinement.html [http://perma.cc/3NKH-YVUC] (describing Washington’s success in “reduc[ing] the number of inmates in restrictive housing by developing special placement programs for the mentally ill and by launching a 16-week training program for guards”).

Policy: Resolutions, Legislation & Legal Issues: Administrative Segregation Sub-Committee , Ass’n St. Correctional Admins. ( Jan . 25, 2013) , http://www.asca.net/projects/16/pages/203 [http://perma.cc/QC6N-SY96].

Press Release, Ass’n of State Corr. Admin., New Report on Prisoners in Administrative Segregation Prepared by the Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program at Yale Law School (Sept. 2, 2015), http://www.asca.net/system/assets/attachments/8895/ASCA%20LIMAN%20Press%20Release%208-28-15.pdf?1441222595 [http://perma.cc/V8TF-BRCG].

Hope Metcalf, Jamelia Morgan, Samuel Oliker-Friedland, Judith Resnik, Julie Spiegel, Haran Tae, Alyssa Roxanne Work & Brian Holbrook, Administrative Segregation, Degrees of Isolation, and Incarceration: A National Overview of State and Federal Correctional Policies (Yale Law Sch., Pub. Law Working Paper No. 301, 2013) [hereinafter Liman Administrative Segregation Policies 2013 Report ], http://ssrn.com/abstract=2286861 [http://perma.cc/DBU3-P48H].

Sarah Baumgartel, Corey Guilmette, Johanna Kalb, Diana Li, Josh Nuni, Devon E. Porter & Judith Resnik, Time-In-Cell: The ASCA-Liman 2014 National Survey of Administrative Segregation in Prison (Yale Law Sch., Pub. Law Working Paper No. 552, 2015) [hereinafter ASCA-Liman Time-In-Cell 2014 ], http://ssrn.com/abstract=2655627 [http://perma.cc/QJ9X-RLSN]. The Liman Project is part of the Arthur Liman Program at Yale Law School. See Arthur Liman Public Interest Program , Yale Law Sch ., http://www.law.yale.edu/centers-workshops/arthur-liman-public-interest-program [http://perma.cc/J7SC-H5ZU].

ASCA-Liman Time-In-Cell 2014 , supra note 38 , at 4-5; see also 2013 Liman Administrative Segregation Policies 2013 Report , supra note 37 , at 5-11.

ASCA-Liman Time-In-Cell 2014 , supra note 38 , at 4-5; see also Liman Administrative Segregation Policies 2013 Report , supra note 37 , at 11-13.

Allen J. Beck, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails, 2011-12 , Bureau Just. Stat. (Oct. 2015), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/urhuspj1112.pdf [http://perma.cc/4V2B-YB64].

Id. at 1 & fig.1.

Prison Fellowship

Understanding the Criminal Justice System

Click on Image to Enlarge

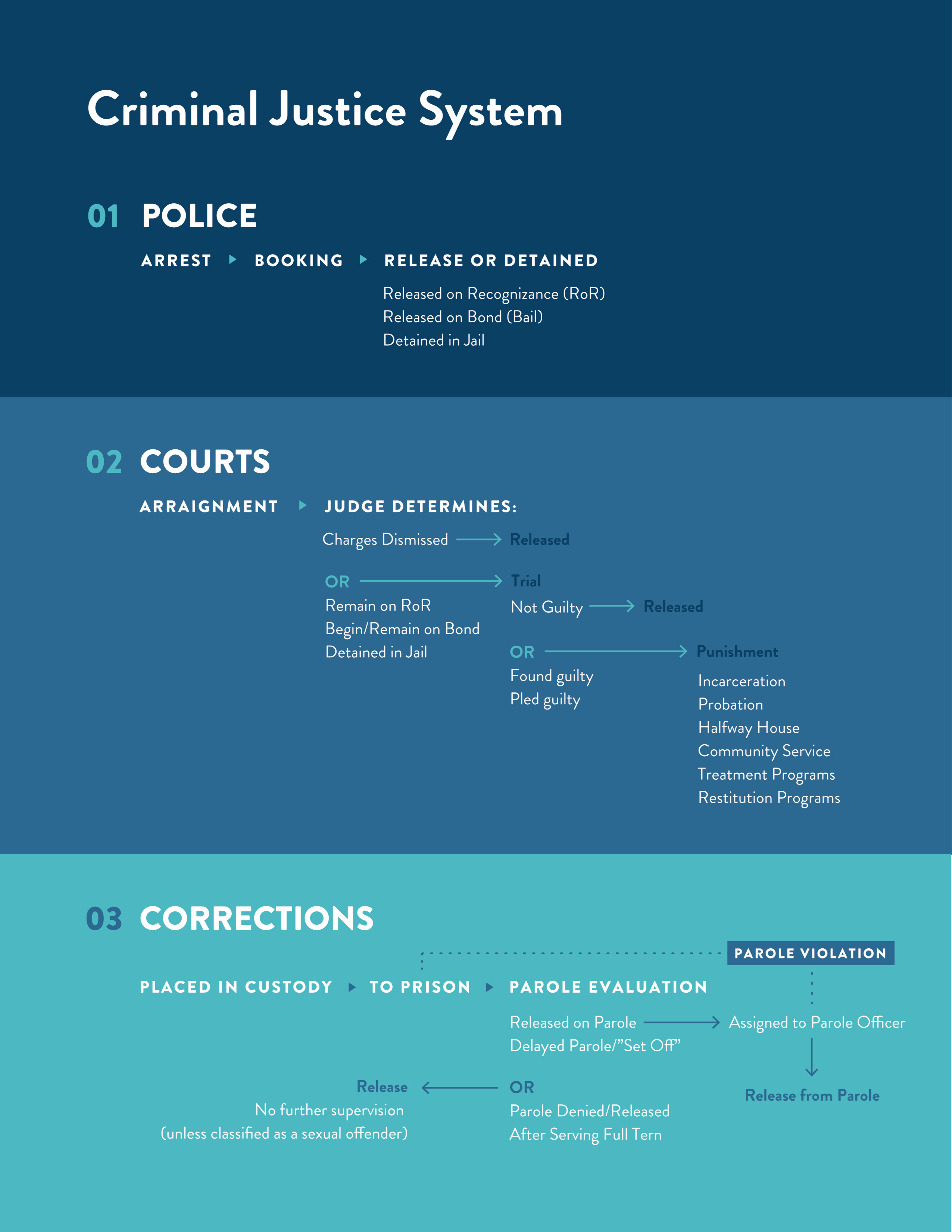

What happens when a person is arrested? Although all states have slightly different laws, this flow chart and outline provides a general overview of what typically occurs as a person is processed through the criminal justice system. The three main phases of this journey are: police, courts, and corrections.

When arrested, a person is taken into custody by the police or other law enforcement.

He/she is then taken to jail to undergo the booking process, which includes getting fingerprinted and photographed. No determination of guilt is made at this point since the case is pending. Evidence is forwarded to the district attorney (DA or prosecutor) who will decide whether there is sufficient evidence to present the case to a judge or jury.

After booking, a judge or court commissioner determines if the person is released or detained. There are 3 options:

- The person may be “Released on Recognizance” (ROR)

- The person may be released on bond (also called bail), which is money paid to the court to ensure the person returns for a future court date

- The person may be detained in jail

After the case is assigned to a judge, the first court proceeding is an arraignment. At the arraignment, a judge or court commissioner reads the formal charges, and explains the defendant’s right to an attorney. The defendant then enters an initial plea.

The judge determines one of four outcomes:

- Charges can be dismissed if there is insufficient evidence; then the person is released

- Person can remain on ROR and the case will continue on to court

- Begin bond process or stay on bond

- Person is detained in jail

When a person has pled not guilty, a date is set for a trial. More evidence/information is gathered by the district attorney as well as the defense attorney. Witnesses may be interviewed and asked to testify in trial.

The defense attorney and the district attorney may negotiate plea bargaining, which allows the defendant to forego his/her right to trial by jury by entering a guilty plea to a lesser charge (which often means a shorter incarceration period).

A trial is held to determine the defendant’s guilt. Often this is a trial by jury, but some defendants prefer to waive their right to a trial by jury and opt for a bench trial (before the judge only).

If the defendant is found not guilty, he/she is released. However, a defendant who has entered a guilty plea or been found guilty is sentenced to some form of punishment.

For first offenders—and depending on the nature of the crime—a judge may give probation instead of incarceration. Probation includes strict supervision for a specified length of time and the accused must regularly report to an assigned probation officer.

CORRECTIONS

In addition to probation, other alternatives to incarceration include halfway houses, community service programs, treatment programs, and restitution programs.

When a person is sentenced to prison he/she is placed in custody of the Department of Corrections (DOC).

The person is sent to a prison unit that is a classification center. Here, the person is assigned to a minimum, medium, or maximum-security correctional facility. Then he/she is transported to the prison unit of assignment.

When the person has fulfilled a certain percentage of the prison sentence, he/she may appear before a parole board that evaluates the prisoner’s readiness for release.

Sometimes a prisoner is given a “set off” to wait a few years for parole. Some are denied parole altogether and must serve the maximum sentence in prison.

When the prisoner is released on parole, he/she is assigned to a parole officer responsible for providing supervision and guidance to the parolee now living in the community. If the parolee violates the terms of the parole agreement, he/she is subject to return to prison to complete the original sentence.

A prisoner who has served his/her entire sentence is usually released without any further supervision (unless classified as a sexual offender). However, any fines assessed as part of the sentence must also be paid.

DOWNLOAD THIS RESOURCE

Download this resource. Once downloaded, you can print, save, or share the pages with others.

BECOME AN ADVOCATE!

You can become an advocate for criminal justice that restores. If you share Prison Fellowship®’s vision for a justice system that restores all those impacted by crime and incarceration, we invite you to join our growing network of advocates. Together we can inspire the Church, change the culture, and advance criminal justice reform.

JOIN OUR ONLINE COMMUNITY

Recommended links.

- Ways to Donate

- Inspirational Stories

- Angel Tree Program

- Prison Fellowship Academy

- Justice Reform

- For Families & Friends of Prisoners

- For Churches & Angel Tree Volunteers

- Warden Exchange

JOIN RESTORATION PARTNERS AND WITNESS GOD RESTORE LIVES

Restoration Partners give monthly to bring life-changing prison ministry programs to incarcerated men and women across the country.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- The Attorney General

- Organizational Chart

- Budget & Performance

- Privacy Program

- Press Releases

- Photo Galleries

- Guidance Documents

- Publications

- Information for Victims in Large Cases

- Justice Manual

- Business and Contracts

- Why Justice ?

- DOJ Vacancies

- Legal Careers at DOJ

- Our Offices

MENU Special Litigation

- Disability Rights

- Corrections

- Children’s Rights in the Juvenile Justice System

- Conduct of Law Enforcement Agencies

- Access to Reproductive Health Clinics / Places of Religious Worship

- Religious Exercise of Institutionalized Persons

- Cases and Matters

Rights Of Persons Confined To Jails And Prisons

The Special Litigation Section works to protect the rights of people who are in prisons and jails run by state or local governments. If we find that a state or local government systematically deprives people in these facilities of their rights, we can act.

We use information from community members affected by civil rights violations to bring and pursue cases. The voice of the community is very important to us. We receive hundreds of reports of potential violations each week. We collect this information and it informs our case selection. We may sometimes use it as evidence in an existing case. However, we cannot bring a case based on every report we receive.

Description of the Laws We Use in Our Corrections Work

The Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) , 42 U.S.C. § 1997a, allows the Attorney General to review conditions and practices within these institutions. Under CRIPA, we are not authorized to address issues with federal facilities or federal officials. We do not assist with individual problems, and we therefore cannot help you recover money damages or any other personal relief. We also cannot assist in criminal cases, including wrongful convictions, appeals or sentencing.

After a CRIPA investigation, we can act if we identify a systemic pattern or practice that causes harm. Evidence of harm to one individual only - even if that harm is serious - is not enough. If we find systemic problems, we may send the state or local government a letter that describes the problems and what says what steps they must take to fix them. We will try to reach an agreement with the state or local government on how to fix the problems. If we cannot agree, then the Attorney General may file a lawsuit in federal court.

In addition to actions under CRIPA, the Section may use the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 , 42 U.S.C. § 14141 (re-codified at 34 U.S.C. § 12601), to protect the rights of persons in the juvenile justice system.

Results of Our Corrections Work

Tens of thousands of institutionalized persons who were confined in dire, often life-threatening, conditions now receive adequate care and services because of this work. We currently have open CRIPA matters in more than half the states.

Our work includes many different kinds of activity. We speak with community stakeholders. We review and investigate complaints. We file lawsuits in federal court when necessary, and enforce orders we obtain from the courts. We participate in cases brought by private parties. We work closely with nationally renowned experts to provide training and technical assistance.

We work closely with other parts of the Justice Department and other federal agencies that regulate, fund, and provide technical assistance to state and local governments. We work with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention , the National Institute of Justice , the Bureau of Prisons , the United States Department of Education , the Department of Housing, and the United States Department of Health and Human Services . In addition, our staff serves on the Department's Health Care Fraud Working Group, the Prison Rape Elimination Working Group, and other task forces.

Community Phone Numbers and Email Boxes

The Special Litigation Section has established toll free phone numbers and email boxes to receive information from the community about the following corrections cases and matters.

Fulton County Jail : 844-473-4092, or by email at [email protected]

Alabama Prisons: 877-419-2366, or by email at [email protected]

Alameda County, CA. (Santa Rita Jail) : 844- 491-4946, or by email at [email protected]

Boyd County, KY. Jail : 877-218-5228

Cumberland, N.J. County Jail : 833-223-1547, or by email at [email protected]

Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women, NJ: 833-341-4675, or by email at [email protected]

Georgia Department of Corrections : 844-401-3736, or by email at [email protected]

Hinds County, MS. Jail : 833-591-0296, or by email at [email protected]

Lowell Correctional Inst. and Annex, FL : 833-341-4676, or by email at [email protected]

Mississippi Department of Corrections : 833-591-0288, or by email at [email protected]

San Luis Obispo, CA, County Jail : 844-710-4900, or by email at: [email protected]

For further information, follow the links below:

- Reports to Congress -- annual reports to Congress describing the Section's CRIPA work

Prisoners’ Rights

Learn more here about your right to be protected against discrimination and abuse in prison and what to do if your rights are violated. The law is always evolving. If you have access to a prison law library, it is a good idea to research new developments.

I experienced assault or excessive force in prison

Your rights.

- Prison officials have a legal duty under the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution to refrain from using excessive force and to protect prisoners from assault by other prisoners.

- Officers may not use force maliciously or sadistically with intent to cause harm, but they may use force in good faith efforts to keep order.

- Prison officials may be violating the Eighth Amendment if they knew about a risk of assault by other prisoners but failed to respond, or if prison conditions or practices create an unreasonable risk of assault (for example, not having enough officers on the unit, not having cell doors that lock properly, etc.).

What to do if you believe that your rights have been violated

- If you have been assaulted by an officer or fellow prisoner, you should file a grievance, and appeal it through all available levels of appeal. Note that there are usually strict time limits for filing a grievance, so you should do so as soon as possible.

- If you believe you are in immediate danger of assault, you should tell a staff member you trust (mental health worker, teacher, etc.).

Additional resources

- Prison Legal News: https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/

- Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual: https://jlm.law.columbia.edu/files/2017/05/36.-Ch.-24.pdf

I’m facing religious discrimination in prison

- Federal law provides special protections for prisoners’ religious exercise. If a prison policy, rule, or practice significantly impedes your ability to practice your sincerely held religious beliefs, prison officials must show that applying the rule to you furthers an extremely important (in legal terms, “compelling”) governmental interest (e.g., prisoners’ safety or health) and that there is no other reasonable way to go about protecting that interest. If prison officials cannot show this, they must provide a religious accommodation to enable you to practice your faith.

- Depending on your particular circumstances, prison officials may be required to provide you with a religious diet (e.g., halal or kosher meals), worship services, and access to clergy. They also may be required to allow you to have religious texts, wear certain religious clothing, headwear, and jewelry, and maintain religious grooming practices (e.g., wearing a beard or long hair).

- Prison officials cannot impose religious beliefs or practices on you. They cannot punish you for declining to take part in religious activities or events that include religious elements. Prison officials cannot give special preference to members of one faith, or treat prisoners of some religions less favorably than those of others.

What to do if your rights are violated

- You can file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Special Litigation Division .

- You can contact the ACLU in your state for more information.

- ACLU – Religious Freedom in Prison

- Department of Justice – Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA)

- Prison Legal News: www.prisonlegalnews.org

- Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual: http://jlm.law.columbia.edu/files/2017/05/39.-Ch.-27.pdf

I'm experiencing discrimination or abuse in prison because I’m transgender

- If you notify prison officials that you are transgender, and/or have been threatened, officials are legally required to act to protect you. When you enter prison, inform staff you are transgender or believe you are at risk — both verbally and in writing.

- The federal Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) requires prisons and jails to make individualized housing placements for all transgender and intersex prisoners, including when assigning them to male or female facilities. A transgender or intersex prisoner’s own views with respect to their own safety must be given serious consideration when making these determinations.

- Many correctional facilities house transgender prisoners in solitary confinement to protect them from violence. PREA says you cannot be segregated against your will for more than 30 days and if you are in protective custody you must have access to programs, privileges, education and work opportunities to the extent possible.

- Prison and jail staff must evaluate you for gender dysphoria within a reasonable time if you request it. Medical treatment for prisoners diagnosed with gender dysphoria should be delivered according to accepted medical standards.

- Blanket bans on specific types of treatments, such as a ban on hormone therapy or gender confirmation surgery, are unconstitutional.

- Staff should generally allow you gender-appropriate clothing and grooming supplies, and allow you to present yourself consistent with your gender identity, or they may be in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

- Strip searches must be conducted professionally and respectfully. A strip search conducted in full view of other prisoners and staff may violate your privacy rights. If there is no emergency, male staff should not strip-search women (including transgender women) and vice versa. Some jails have policies allowing transgender prisoners to choose the gender of the staff to search them.

- Staff cannot conduct strip and pat-down searches solely to assess your genitals. Staff must be trained to conduct searches of transgender and intersex prisoners in a professional and respectful manner, and in the least intrusive manner possible, consistent with security needs.

- If you request a private shower, PREA requires that officials grant you access.

What to do if you believe your rights might be violated

- Report your concerns or any specific threats to your safety to staff in writing, and also send a copy to the inspector general, the PREA coordinator for the agency with custody over you, and someone outside whom you trust.

- If you are assaulted, file a grievance as soon as possible, though cases of sexual assault may have more flexible time limits on reporting or may have special reporting processes.

- Prisoners who want to file a federal lawsuit about events in jail or prison must first complete the internal appeals process. This means that you need to know the rules of any appeals (or “grievance”) process in your facility, including time limits on filing an appeal after something happens. In most prisons or jails, you will have to file a written complaint on a form that is provided.

- If staff refuse to evaluate you for gender dysphoria or fail to provide you with care, file a grievance and appeal through all levels.

- If you were receiving hormones from a doctor prior to incarceration, have your medical records sent to the medical or health director at your facility.

- If you are placed in protective segregation and do not want to be there, file a grievance and all appeals about your placement. You should also appeal anything that seems unfair about your placement, such as not being able to participate in a hearing, not being told why you were moved to segregation, not being able to participate in programming or obtain a job, or not being told when you can get out.

- If your placement is based on so-called safety concerns and you would feel safer in a women’s facility (as a transgender woman), request such a transfer and file appeals if you do not get one.

- If you are asked to strip down in front of other prisoners and you do not feel comfortable, politely ask to be moved to a separate area.

- If you cannot use a private shower, ask to shower at a different time from other prisoners or in a private area (as the PREA standards require).

- If you do not want to be searched by a staff member of a particular sex, politely ask for a different staff member to search you. In some prisons or jails, you may also be able to get a general order that says you should only be searched by women (if you are a transgender woman).

- Ask for your facility’s official policies related to your circumstances. Sometimes you can find these policies in the prison library.

Black and Pink 614 Columbia Rd. Dorchester, MA 02125 (617) 519-4387 www.blackandpink.org

Just Detention International 3325 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 340 Los Angeles, CA 90010 (213) 384-1400 1900 L St. NW, Suite 601 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 506-3333 www.justdetention.org

National Center for Lesbian Rights 870 Market St., Suite 370 San Francisco, CA 94102 1-800-528-6257 www.nclrights.org

National Center for Transgender Equality 1325 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 903-0112 www.transequality.org

I'm pregnant and in prison

- You have the right to an abortion if you want one, and to refuse an abortion if you do not want one.

- You have the right to prenatal and other medical care for your pregnancy and postpartum care.

- You cannot be forced to pay before you can get the medical care you need.

- You may have the right not to be shackled: many states have laws or policies that prohibit or limit the use of shackles on prisoners who are pregnant, are in labor, or have recently given birth. Some courts have also said that shackling is unconstitutional. The ACLU’s anti-shackling briefing paper provides more detailed information.

- You have the right to refuse sterilization or other unwanted birth control after your pregnancy.

What to do if you think your rights have been violated

- If you are not getting the medical care you need, ask other medical or other staff to help you.

- Document everything that happens. Put your request for an abortion or other medical care in writing and keep a copy. Also, keep a list of the people who you’ve spoken to or contacted and write down what they say and the dates and times you spoke to them.

- In addition to your request for medical care, you should also file a grievance (an official complaint) if your medical needs are not met. If your grievance is denied or rejected, file an appeal and pay attention to all the rules and deadlines of the grievance system, which are usually written in the inmate handbook.

- If the prison isn’t providing you the medical care you need, contact your own lawyer, a prisoner legal services organization (if one exists in your state), NARAL, Planned Parenthood, your local ACLU affiliate, or the National Prison Project of the ACLU.

I’m in prison and have a disability

Examples of discrimination against people in prison with disabilities.

- Exclusion from facilities, programs, and services that are accessible to other prisoners.

- Not providing sign language interpreters for a deaf prisoner at disciplinary hearings, classification decisions, medical appointments,, and educational and vocational programs.

- Failure to provide medical devices such as wheelchairs and canes to disabled prisoners.

- Placement in segregation or solitary confinement due to perceived vulnerability or the unavailability of accessible cells in general population.

- Prisoners with disabilities are protected under sections of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. In the prison and jail context, the Rehabilitation Act applies to facilities run by federal agencies (such as the Bureau of Prisons) and to any state or local agency that receives federal funding. The ADA regulates facilities run by state and local agencies, regardless of whether they receive federal funding.

- You are entitled to an equal opportunity to participate in programs and services for which you are qualified.

- You are entitled to be housed at your correct security level, and in a cell with the accessible elements necessary for safe, appropriate housing.

- You are entitled to reasonable modifications to policies and procedures.

- You are entitled to equally effective communication including any necessary auxiliary aids and services such as sign language interpreters, captioning, videophones, readers, Braille, and audio recordings.

- Prison officials are not required to provide accommodations that impose undue financial and administrative burdens or require a fundamental alteration in the nature of the program.

- Prison officials are also allowed to discriminate if the disabled prisoner’s participation would pose significant safety risks or a direct threat to the health or safety of others that cannot be mitigated through reasonable modifications.

What to do if you believe your rights have been violated

- File a formal grievance through your facility’s grievance process and appeal all levels available. If your facility has an ADA Coordinator you may also contact that person and ask him/her to help you with an accommodation for your disability.

- You or your attorney can file a lawsuit explaining how your rights have been violated under the ADA, the Rehabilitation Act, or both. You must complete any available grievance procedure and all appeals before filing a lawsuit in federal court.

- To bring a lawsuit under these laws, disabled prisoners must show: (1) that they are disabled within the meaning of the statutes, (2) that they are “qualified” to participate in the program, and (3) that they are excluded from, are not allowed to benefit from, or have been subjected to discrimination in the program because of their disability. Under the Rehabilitation Act, prisoners must also show that the prison officials or the governmental agency named as defendants receive federal funding.

- Depending on the situation, disabled prisoners may file claims for relief under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel or unusual punishment, in addition to or instead of the ADA or Rehabilitation Act.

- The laws of some states may provide different or greater legal rights than the federal laws. Disabled prisoners should investigate this possibility before bringing suit.

- Every state and U.S. territory has a federally mandated Protection and Advocacy (P&A) organization that works to provide assistance and legal services to individuals with disabilities. Some of these organizations also work with incarcerated individuals. For a complete listing of all these organizations by state click here: https://www.ndrn.org/ndrn-member-agencies.html

I want to receive publications in the mail in prison

- Prisoners generally have the right to receive books, magazines, and newspapers by mail, subject to the restrictions described below.

- Prison authorities can generally decide to censor a publication for reasonable goals related to prison safety or security, but cannot reject publications because they disagree with their political viewpoint or for other arbitrary reasons.

- Prisons cannot discriminate against religious publications by arbitrarily subjecting them to rules that do not apply to non-religious publications.

- Prisons and jails may ban material that describes how to build weapons, instructs how to escape, or instructs how to break the law. They can ban magazines that contain nudity and pornography.

- Often prisoners have the right only to receive softcover books and bound periodicals sent directly from a publisher, bookstore, or other commercial source, but sometimes courts have allowed prisoners to receive clippings and copies of articles from friends, family, or other noncommercial sources.

- Prison officials cannot prevent your friends and relatives from buying you books and magazine subscriptions.

- Both you and the sender have the right to be notified if your incoming publication is being censored or rejected. Prison officials must give enough of a reason for their censorship decision to allow you to challenge that decision.

- When you learn that a publication has been rejected, you should always try to check your institution’s publication policy. If you believe the policy has been violated, you should file a grievance, and appeal it through all available levels of appeal. Note that there are usually strict time limits for filing a grievance, so you should do so as soon as possible.

- Prison Legal News

- Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual

I want to send and receive mail in prison

- The First Amendment of the Constitution entitles prisoners to send and receive mail, but the prison or jail may inspect and sometimes censor it to protect security, using appropriate procedures.

- Prison officials’ ability to inspect and censor mail depends on whether the mail is privileged or not. Officials may open non-privileged mail, which includes letters from relatives, friends, and businesses, outside your presence. They can read this mail for security or other reasons without probable cause or a warrant.

- Incoming or outgoing non-privileged mail may be censored for legitimate security reasons. However, mail may not be censored simply because it is critical of prison officials or because prison officials disagree with its content.

- Prisons may not ban mail simply because it contains material downloaded from the Internet. You may not be punished for posting material on the Internet with the help of others outside of prison.

- Clearly marked privileged mail, which includes communications to and from attorneys and legal organizations like the ACLU, gets more protection. Officials may open incoming privileged mail to check it for contraband, but must do so in your presence. They are not allowed to open outgoing privileged mail. Privileged mail ordinarily cannot be read unless prison officials obtain a warrant allowing them to do so.

- If your incoming mail is censored, both you and the sender are entitled to notice. The notice must explain the reasons for the censorship in enough detail to allow you to challenge it.

- If you believe your rights with respect to mail have been violated, you should file a grievance, and appeal it through all available levels of appeal. Note that there are usually strict time limits for filing a grievance, so you should do so as soon as possible. You should file a new grievance for each incident; you have a better chance of succeeding in a lawsuit if you can establish that the prison’s violations of your rights are the result of an ongoing policy or practice, rather than isolated incidents.

Other Know Your Rights Issues

- State Profiles

Advocacy Toolkit

- Fact Sheets

Stay Informed

Get the latest updates:

Can you make a tax-deductible gift to support our work?

The state prison experience: Too much drudgery, not enough opportunity

An underutilized government dataset goes deep into daily life in state prisons — including work assignments, programming, and discipline — revealing lost opportunities for rehabilitation, education, and hope..

by Leah Wang , September 2, 2022

Using data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates , this briefing reveals how prisons fail to implement programs that we know “work” at setting incarcerated people up for success in the future (such as giving people opportunities to earn money , obtain an education , or gain relevant job skills). 1 These failures have far-reaching effects: When people in prison have little to no income, they may accumulate child support debt , suffer without essential commissary items, or be unable to access communication with loved ones, which can impact people on both sides of the bars. Less overall opportunity in prison can mean lowered prospects for employment and finding stable footing upon release.

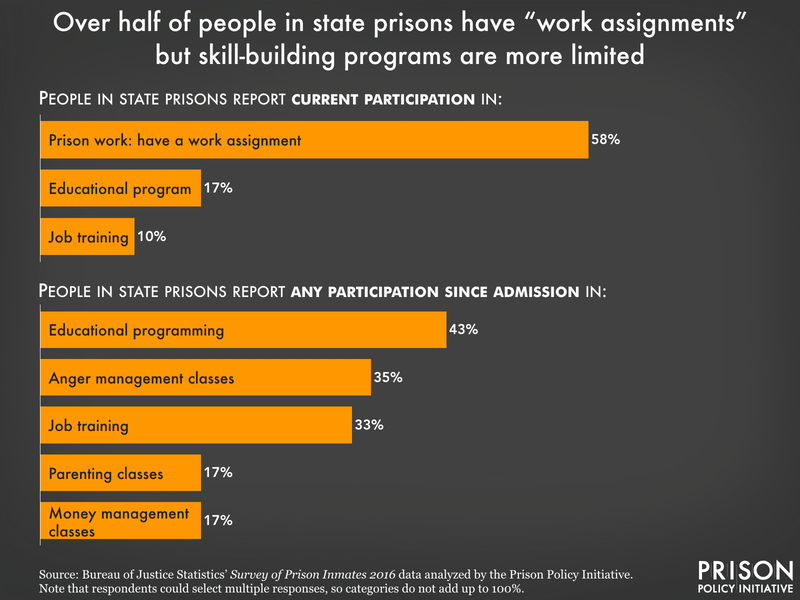

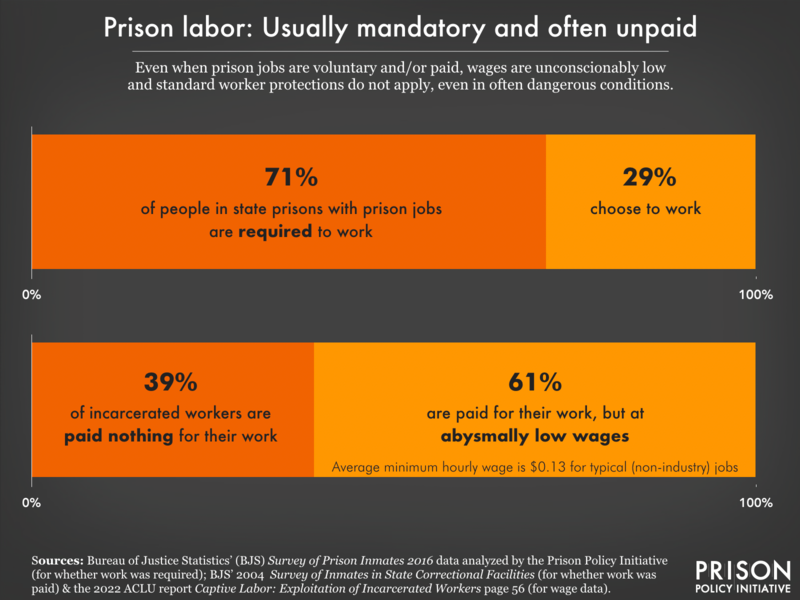

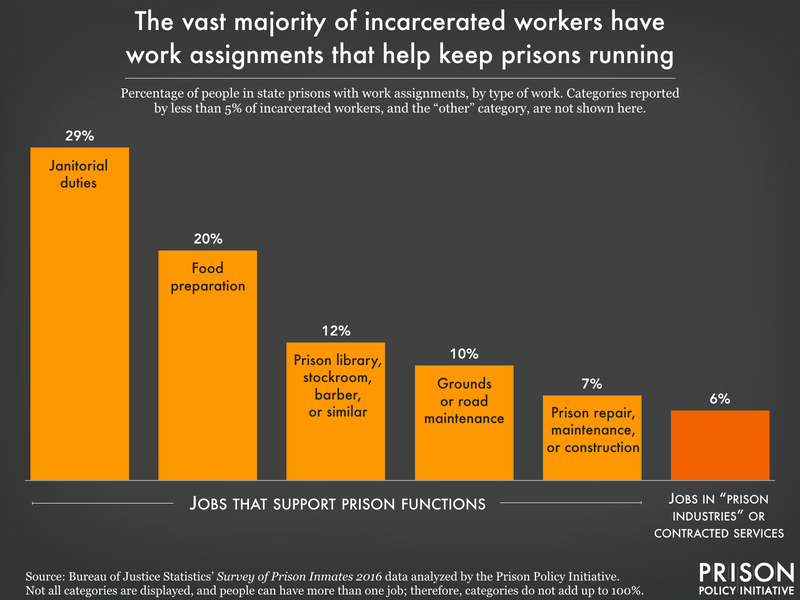

Prison work is often compulsory, does little to build useful skills, and pays almost nothing

Prison jobs, often called “work assignments,” are the most common “programming” offered in state prisons. 2 Prisons rely on the labor of incarcerated people for food service, laundry, and other tasks that offset operational expenses. (While less common, some prisons also contract with public and private entities, assigning some people to “prison industries” jobs where they do anything from make eyeglasses to fight wildfires.) In general, work assignments are not thoughtfully designed to provide job skills and development: They are intended to keep the prison running and keep “idleness” at bay.

Data note: The last time the data were collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) on how many workers are paid was in 2004. But in 2022, six states (Ala., Ark., Fla., Ga., S.C., and Texas) still paid nothing for most or all jobs done by incarcerated people, and together, these states made up 30% of state prison populations nationwide in 2019, suggesting that the percentage of workers who are unpaid has likely not changed much since the 2004 survey.

Employment as we know it outside of the carceral system is typically a consensual relationship between employer and employee, and protected by employment laws; prison work assignments, on the other hand, are often compulsory, and incarcerated workers have few rights and protections compared to non-incarcerated workers. 3 Prison labor is sealed off from standard workplace protections and minimum wage laws by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which contains an “ exception clause ” allowing slavery or involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime.

If an incarcerated person refuses to work, they often face disciplinary action . Those who do work receive paltry wages — far less than $1 per hour, typically – and even those mere pennies are often deducted to pay for fees, restitution, and child support, or must be saved for basic necessities like medical visits , hygiene items , and phone calls .

According to the national Survey :

- 58% of people in state prisons have a work assignment . Most of these jobs help keep the prison functioning, such as janitorial duties (29% of workers); food preparation (20%); working in a prison library, stockroom, barber shop, or similar (12%); groundskeeping (10%); and jobs doing maintenance, repair, or construction (7.4%). Only about 6% work in “prison industries” jobs, producing goods or services for other state agencies or companies. 4

- Considering the broader context of incarcerated people’s lives before prison, 61% of those who had provided at least half of their household’s income before their arrest reported having a prison work assignment in prison. These individuals are now almost certainly earning significantly less than they did in the outside world. And the remaining 39% of former income-providers who now have no work assignment may be experiencing a dramatic shift from providing for their loved ones to having no income to contribute to their families at all.

- Most (71%) people with a work assignment are required to have one , suggesting that many people are forced to work. While many people in prison want to be productive while behind bars, they lack any control in pursuing relevant, stimulating, and/or safe work assignments. 5

- People in prison who were not forced, but chose to work, said the following reasons were “very important” in their decision: learning new skills (70%), earning money (54%), relieving boredom (51%), or earning good time for earlier release (45%). (Only the 29% of people who chose to work were asked about their motivations.)

- White people in state prisons were slightly more likely than people of other racial and ethnic groups to have a work assignment (63%, compared to 54%-58% for other groups). Previous studies point to racial bias (and gender bias ) in how jobs are assigned to incarcerated people.

The Survey did not ask about wages earned (or even whether respondents earned anything at all), but a recent analysis found that the highest-paid incarcerated people earned over one dollar per hour in “industries” jobs, while the typical state prison job — doing things like laundry, food preparation, or other tasks supporting prison operations — paid only 13 to 52 cents per hour. 6 These unthinkably low wages have remained stagnant since our 2017 deep dive into prison earnings (and even then, we found that some prisons were paying workers less than they had in 2001). Considering the additional blow dealt by inflation, people in prison have virtually no chance of building up financial savings, no matter how hard they work.

State prisons lack educational opportunities, job training, and programming that would help develop skills

Prison work assignments are not the only area where prison policies are inconsistent with what we know would help incarcerated people. In the words of one group of researchers, prison programs that build skills, confidence, and mental health “reduce recidivism by increasing the opportunity cost of committing crimes.” But the staggering length of waiting lists for education and programming at many facilities nationwide tells us not only that incarcerated people want programming, but that there is not nearly enough.

Overall, about two-thirds (68%) of people in state prison have participated in some type of programming, including education (43%); job training (33%); and classes in anger management (35%), parenting (17%), or money management (17%).

According to the Survey :

- Because most work assignments involve menial tasks that are unlikely to help people find skilled work upon release, it seems likely that job training programs would be popular among incarcerated skill-seekers. But the Survey data show that only one-third (33%) of people in state prisons report ever having participated in job training . This lack of widespread job training opportunities may help explain why 29% of incarcerated workers voluntarily chose to take on their work assignments.

- Most of those (58%) who were ever enrolled in job training successfully completed their program, but 1 in 5 (20%) people were prematurely cut off from their program before finishing . 7

- White and Hispanic people were the least likely racial or ethnic groups to participate in job training (29% each, compared to 33%-37% for other groups). This disparity could be explained by the fact that white and Hispanic people had the highest rates of pre-prison employment , which could indicate less need for training.

Offering education in prisons has a known return on investment , leading to well-documented reductions in recidivism and providing the credentials that lead to better jobs. People tend to enter prison with lower-than-average education levels , and were often under-supported and over-disciplined while in school. 8 Yet instead of being able to make up for lost time by enrolling in educational programs, the Survey data reveal that only 43% of people in state prisons have participated in educational programming (even though 62% had not completed high school upon admission) . Participation rates in education are similar among men and women and across age groups, though incarcerated women are more likely to have a high school education than incarcerated men.

Our analysis of the Survey results also found that:

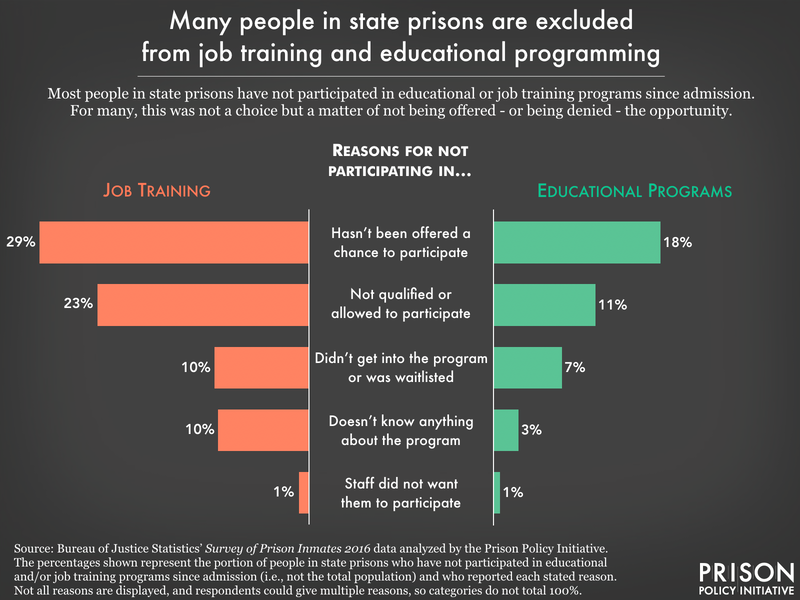

- Among the 57% of people in state prisons who had never participated in educational programming, the reasons they cite for not participating are illuminating: 18% — over 125,000 people — had never been offered the chance . Another 11% said that they weren’t qualified or allowed to attend, and 7.3% said they could not get into an education program or were waitlisted — again pointing to the widespread problem of waitlists for programming in prisons. Some of these same failures to inform people of educational opportunities and get them enrolled applied to job training programs, too.

- White people in state prisons were the least likely to participate in an education program compared to all other racial and ethnic groups. 9 This finding may be related to the relatively higher educational attainment of white people who enter state prison compared to other groups, particularly Black and Hispanic people, and the requirement in some prison systems that people without a high school education must enroll in basic education courses.

- Half (53%) of people without a high school credential reported former or current enrollment in education programs, compared to less than 30% of people with at least a high school diploma – further evidence that high school and college opportunities aren’t equally available in prisons. 10 While high school equivalency (e.g., GED) programs can start to bridge the education gap between incarcerated people and the general public, the lack of higher education opportunities remains a problem, as a high school education alone greatly limits employment prospects . 11

Even minor rule violations in prison can have serious consequences

Prisons have strict rules that govern nearly every aspect of life, and incarcerated people face frequent, excessive, and often arbitrary punishment for alleged violations of those rules. Importantly, discipline systems in prison do not have nearly the same level of due process or transparency that courts do: Correctional officers can hand out “tickets” for suspected rule violations at their discretion, setting off a series of administrative hearings and investigations led by prison staff. People behind bars do not have the right to an attorney (related to the violation), to cross-examine witnesses, or to be judged by a jury of their peers, even when they are accused of an action that would be a crime in the free world. And whether the incarcerated person pleads guilty or not, a hearing committee or higher authority can issue sanctions to almost any degree.

In his 1975 illuminating deep-dive, Prisons: Houses of Darkness , law professor Leonard Orland points out the trap set by unjust systems of prison discipline, which still holds true today:

“Punishment imposed by a prison discipline committee constitutes a most unfair kind of ‘triple jeopardy.’ Typically, the same committee that ordered punitive segregation also has the power to take away statutorily or meritoriously earned ‘good time,’ … Moreover, records of such misconduct are seen by the parole boards and may well be a factor in parole denial. Thus, a finding of prison misconduct may result in three separate losses of freedom for the inmate.”

Our analysis of the Survey data shows that people in state prisons can be harshly punished even for minor, non-violent infractions. This is disproportionately true for women, and in some cases for people of color. Specifically:

- More than half (53%) of people in state prisons had been written up for or found guilty of at least one rule violation in the past year. 12 This is the same percentage of people written up for rule violations in 1986 – although state prisons in 2016 held nearly 800,000 more people than they did 30 years prior, so far more individuals are impacted by prison discipline today. Of respondents who were written up at least once in the 12 months prior to the Survey , about 9% reported receiving a “major” violation, a category that includes assault, rioting, attempted escape, and food strikes.

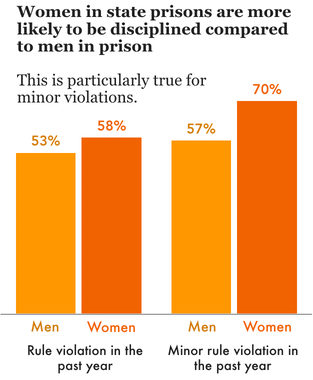

- Women in prison are more likely to report being written up for a rule violation in the past year than men (58% versus 53%). Of those who were written up at least once, women were more likely to have received a “minor” rule violation than men (70% versus 57%). These data align with research showing that women are more likely to be written up and disciplined for breaking prison rules, and receive disproportionate punishment for minor, subjective infractions like “disrespect.”

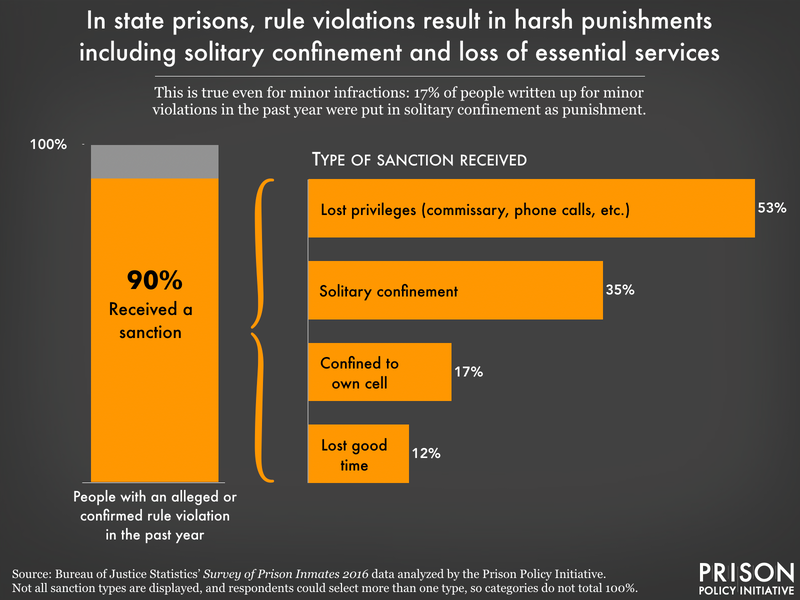

- Nearly all people (90%) with a major or minor rule violation in the previous year received some form of disciplinary action . Of those who were disciplined, about half (53%) lost certain “privileges,” like access to the commissary, visitation, or phone calls, even though these things should arguably be considered “essentials,” not “privileges,” in prison. And 1 in 8 (12%) lost sentence-reducing “ good time ” (days credited off one’s sentence for good behavior) that they’d already earned. And, of course, these violations become part of each individual’s disciplinary record, which impacts weighty decisions including parole release. All of these punishments underscore the high stakes of prison discipline.

- One-third (35%) of those who received a disciplinary action for their most recent rule violation were ordered to solitary confinement , an extreme measure that is hardly ever appropriate (and often comes with the losses of other “privileges” mentioned above). This high dependence on solitary confinement is particularly concerning, as the international human rights community considers solitary confinement, as practiced in U.S. prisons, to be torture . 13

- Men (26%) were more likely than women (17%) to receive solitary confinement as a sanction for a rule violation. This finding tracks with national data on the use of “restricted housing,” which includes solitary confinement. Some state prison systems have recently moved to cut down on using solitary for specific populations (for example, Massachusetts eliminated the “restrictive housing unit” at its only women’s prison in 2020). However, women were more likely than men (18% vs. 12%) to be confined to their own cell as punishment, a practice that advocates consider similarly egregious .

- Racial disparities in sanction types were not readily apparent through the Survey data. For example, between 22% and 28% of each racial or ethnic group was sent to solitary confinement as a sanction, and between 1% and 4% of any given group were transferred to another facility as punishment. Nevertheless, research points to alarming racial disparities in how rule violations in state prisons are recorded and disciplined. 14

- The survey data suggest that prisons lean heavily on solitary confinement for infractions that involve no physical harm, such as “verbal assault.” 15 Even respondents who were written up for things falling into the category “other minor violations” ended up in solitary 17% of the time. Even if everyone who was ordered to solitary confinement for their most recent past-year violation served just one day there (and many certainly had much longer stints than that), this amounts to 135,000 days, or 370 years in solitary confinement.

Prison rules and disciplinary procedures are an under-discussed issue that shapes daily prison life. As the Survey findings make clear, just as with work assignments and programming, there is a disconnect when it comes to rule violations between what prisons do in practice and what would actually help people return to their communities with a fair chance at a good life. Solitary confinement, in particular, is incredibly damaging to mental health, even increasing the risk of premature death after release from prison. But any sanctions that disrupt what little support exists for incarcerated people are bound to fail them in the long run.

Conclusion and recommendations

In the name of “justice,” states misguidedly send large numbers of people with low levels of education and income to prison, and then offer them little in the way of economic, professional, or personal growth opportunities to increase the odds of a better future. The Survey data show that incarcerated people are starved for opportunities to earn a real living and find purpose in state prisons. It’s in everyone’s best interest to offer meaningful opportunities to incarcerated people — for one, it costs far less to educate someone compared to locking them up. Putting obvious fiscal considerations aside, disrupting the cycles of struggle, unlawful or violent behaviors, and incarceration will require more compassionate — and less carceral — interventions.

Policymakers must drill down to these aspects of everyday prison life to improve outcomes. Without better opportunity and preparation, the hope to which so many incarcerated people cling throughout their sentences will wane, their cycles of incarceration will continue, and the crisis of mass incarceration will continue to be one of our nation’s greatest failures. Therefore, we recommend that states:

Bring prison employment into modern, real-world context:

- Legally recognize incarcerated workers as employees, affording them workplace protections, the right to unionize, and minimum wages

- In applicable states, end the requirement to work in prison 16

- Ensure that work assignment and job training opportunities align with skills and technologies that are relevant to today’s job market

- Establish policies and accountability measures to ensure work assignments are not allocated in a discriminatory manner

Shift priorities away from monotonous work and punishment, toward opportunity:

- Ensure that all incarcerated people are aware of programming and educational opportunities available to them

- Shift prison budgets away from costly and counterproductive practices like solitary confinement and toward improvements in job training, high-quality higher education , special education , and English as a second language education, and other programs

- Provide people who participate in educational or other prison programs with pay equal to what they would receive for a work assignment 17

- Allow people to complete a program before transferring to a facility that does not offer the same program (at a minimum, require that every effort is made to allow continued participation)

- Ensure that people being released from prison can continue their education or training, instead of having to drop everything and find work immediately to satisfy parole requirements 18

Pull back the curtain on rule violations and prison discipline:

- Acknowledge gender and racial biases in how prison rules are enforced and sanctioned by correctional staff, and work to end excessive and disparate disciplinary practices

- Prohibit the forfeiture of earned good time as a sanction, as “good time” is a strong motivator for good behavior, 19 and an important tool for safely reducing prison populations

- End the use of solitary confinement and other forms of harmful, long-term segregation

You can read more about the demographic, early life, and health-related results from the 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates in two of our latest reports, Beyond the Count: A deep dive into state prison populations , and Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons , and our briefings, What the Survey of Prison Inmates tells us about trans people in state prison and Both sides of the bars: How mass incarceration punishes families. ↩

According to the Survey of Prison Inmates, 58% of people have a work assignment, compared to the next-highest result, 43% of people who have “ever” participated in educational programming. ↩

Though not explicitly excluded, the courts have interpreted the Fair Labor Standards Act – which provides federal minimum wage, overtime protection, and other standards – to exclude incarcerated workers. ↩